94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY article

Front. Polit. Sci., 30 April 2024

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1140683

This article is part of the Research Topic‘Being Political’ 20 years later: why is it good to think with Engin Isin?View all 3 articles

This research investigates the relationship between the city and the state in framing the national belonging of space as arenas of inclusion and difference within the nation. It is argued that bringing Isin and Lefebvre into dialogue allows for a genealogical analysis of space as a social product imbued in and constituted by narratives of national inclusion (or exclusion). This research develops the concept of alterity-space as a distinct spatial category in which the constitution of citizenship is inscribed on socially produced space. This alterity-space refers to categories of difference as an internal other of space at odds with the space of the nation. Alterity-space as a concept invites reflection on how state engagement, competing symbolisms, narratives, and interactions produce spatiality and create mechanisms of othering that obscure other articulations of national belonging in space. This approach is illustrated through a genealogical examination of Lasnamäe, an urban district at the heart of Estonia’s capital. In the constitution of national, ecological, digital, and European identities, Lasnamäe is positioned as an alterity-space to Tallinn and Estonia. This positioning reflects how space itself becomes imbued as an immediate other at odds with Estonia’s past and future of national belonging.

Citizenship today has become a polysemic term reflecting relations between state and citizen in wider movements for (and against) globalization, securitization, and digitalization. Overall, there is a marked desire to broaden the meanings, significance, and practices of citizenship (Nyers, 2007). Notably, emphasis has been placed on re-centering the citizen (Kymlicka and Norman, 1994) in thicker contextual descriptions, allowing specific forms of citizenship to emerge (Clarke et al., 2014). In this context, the last two decades of citizenship studies have explored the performative aspects of how subjects (legal and others) act to claim forms of citizenship, where a newer vocabulary for conceptualizing citizenship is required (Isin, 2009). A similar concern on newer conceptualizations of citizenship has been expressed by scholars of human geography who have called for newer geographies of citizenship that bring space, scale, and performative citizenship together (Desforges et al., 2005). Indeed, the novelty of being political (Isin, 2002) rests in applying spatial theories to the genealogical investigation of citizenship.

However, in these examinations and its growing disentanglement from the state, the enduring and constitutive role of the state1 in forms of citizenship has received limited attention (Koster et al., 2018). State engagements in space are increasingly studied in nation-building and branding discourses, with relatively limited attention paid to the implications of such narratives on constitutions of citizenship2 (Bottery, 2003). This research seeks to fill this gap by exploring contested constitutions of national space as hierarchies of space in a nation. In thinking with and beyond Isin in dialogue with Lefebvrian productions of space, the aim is to understand how socially constructed hierarchies of space contribute to the constitution of a nation’s spatial narrative (Williams and Smith, 1983).

Gross (2002) suggests that national space is the space on which narratives of identity and belonging are rendered visible. The spatial turn has deepened such analysis by recognizing space as more than a stationary background upon which social contexts unfold. Furthermore, Isin (2007) has demonstrated the significance of the city in relation to citizenship and the national scale through a critique of abstract and real spaces in scalar thought. He contends that while states and nations are transient impermanent entities, cities represent actual enduring spaces. He further argues that the physical and political space of the city contributes to the framing of the national landscape. This insight into the relationship between the city and the national scale frames the backdrop of research on the nation’s spatial narrative.

Although most articulations of national space occur in differentiation from external others, Isin invites reflection on constitutive and relational dynamics with the internal other.3 For Isin, citizenship and its alterity always constitute each other (Isin, 2002). This relationship is articulated through differentiation and hierarchies constituting citizens and others (Drummond and Peake, 2005). In thinking with Isin (2002), the relationship between spaces is studied with a focus on the internal constitution of the spatial narrative of the nation. To do so, the study develops the concept of “alterity-space” to refer to a distinct spatial category in which the constitution and contestation of citizenship and alterities emerge and are etched onto urban space. Alterity-space can be understood as the difference in which hierarchies of space-among space of citizenship and immediate other spaces in the nation - become constituted.4 By exploring alterity-space, the genealogies that structure space itself can be investigated in framings of national space. This approach is exemplified through a genealogical investigation of Lasnamäe, Tallinn. It is argued that in developing a national, ecological, digital, and European identity, Lasnamäe is cast as an alterity-space signifying a soviet-era artificial industrial imposition at odds with national narratives of belonging to Estonia’s past and future.

The novelty of this approach is two-fold: first, the investigation of citizenship and alterity in space are extended to the constitution of spatial narratives, configurations of national space, and articulations of national belonging to space itself. Second, genealogies and geographies of citizenship are brought together to explore how space itself is constituted in hierarchies of difference among spaces that fit the national narrative and spaces that are at odds with the nation.

This study is divided into two main sections dedicated to the same objective. The first section introduces alterity-space as a distinct spatial concept by bringing Isin and Lefebvre into dialogue. This section extends Isin’s insights on the city as a medium of generative difference to a wider conversation on Lefebvrian productions of space. Through this dialogue, the genealogical capacity of the concept is underscored. The second section exemplifies one such alterity-space through an investigation of Lasnamäe Tallinn in hierarchies among national space and internal other spaces in the nation.

This section introduces the concept of alterity-space. Through this exploration, national space is seen as an outcome constituted by hierarchies of socially constituted space within the nation. This is done by extending Isin’s insights on citizenship, the city, and the state to Lefebvrian insights on the production of space. Drawing from Lefebvrian theories, this expansion offers a roadmap for the genealogical unpacking of socially constituted space, which facilitates an exploration of the national narratives that structure identities, hierarchies, and belonging of space in the nation.

The spatial turn highlights the two-fold relation of space to the social. This is aptly articulated in Soja’s (1980) socio-spatial dialectic, where space is a constitutive element in social relations (space as the medium) and is also simultaneously constituted by social relations (spatiality). In the former, space serves as a complex but vital medium for difference among identities. Space is just an element of difference in addition to demographic, social, cultural, and political differences. This resonates with Isin’s theorization of the city as well. For Isin, the city serves as a constitutive element of difference where positions, orientation, acts, demands, and claims are played out (Isin and Nielsen, 2008). Isin sees the city as this medium for generating difference:

“…by the dialogical encounter of groups formed and generated immanently in the process of taking up positions, orienting themselves for and against each other…” (Isin, 2002, p. 49).

Through these encounters and positions, the city can be critically interrogated to analyze various forms of citizenship and others.5 However, thinking beyond the city as a medium of generative difference toward spatiality underscores a different relationship between the spatial and the social.

Spatiality emphasizes how difference becomes ingrained in the very fabric of space itself. Here, scholars emphasize the structured effects of space as a produced social reality. Space itself is a socially constructed outcome. For instance, Harvey (1976) examines space’s relation to economic capital in the city. He contends that the city obscures the social relations of capital and produces itself as a commodity in space. Similarly, Amin (2007) argues that ethnic differences structure cities as spaces for certain ethnicities. Isin also acknowledges citizenship as spatial-temporal ways crystalized within the city. However, he provides little insight into how spatiality itself could be investigated. Rather, he is critical of such investigations. Reflecting on Lefebvrian insights on space as a produced reality, Isin contends:

“…This tradition remains locked in social scientific styles of thought which are a-historical, presentist and explanatory as opposed to genealogical and investigative” (Isin, 2002, p. 43).

Although Isin rejects the possibility of a dialogue with Lefebvre, the concept of alterity-space serves as a ground where the two scholars converge. For Isin and Lefebvre, the city serves as a material and symbolic marker of the state and the nation. For Lefebvre, the city holds a significant ontological place where state power and its challenges are constituted and articulated (Lefebvre, 2003; Stanek, 2011). Similarly, for Isin, citizens, alterity, and the city relate to the state and nation:

“… the territoriality of the state and its sovereignty are itself through the city and that no state can come into being without articulating itself through the city via various symbolic and material practices” (Isin, 2005, p. 385).

This convergence of thought on the intimate connection between the city, the state, and the nation serves as the backdrop where alterity-space can be constructed as a distinct spatial category for genealogical investigations of national (and internal other) space.

Lefebvre (2003) suggests that the state develops spatiality by constructing hierarchical and disjointed spaces. The state actively and passively configures space, molding it to reflect certain social, cultural, and political realities. Brenner and Elden (2009) draw on Lefebvre to analyze how state strategies turn complex political dynamics into abstract technocratic engagements. Investigations of urban policy reveal how the state codifies space among formal, legal, safe, regulated, and informal urban arenas (Roy, 2012). Additionally, Kaneva (2011) argues that nation-building and branding discourses also serve as state interventions shaping spatiality. Aronczyk (2007) further argues that these narratives create national spaces through territorial demarcations and symbolic and cultural discourses, which construct and project national identities onto space. Through these actions, orientations, and discourses, the state contributes to the production and reification of the national territory (Kowalski et al., 2009).

The debates that relate cities, states, and nations together are fairly pronounced in post-socialist city spaces. Diener and Hagen (2013) examine the changes in post-socialist urban centers to reveal the increasingly complex economic, cultural, and political forces that shape the development of the city. They contend that state strategies and discursive framings relate to the developmental trajectory of the city and simultaneously underscore the nationalist and post-communist aspirations of the state. Similarly, Schatz (2004) explores how capital cities relate to both nation- and state-building projects. He contends that the city serves as an attractive site to reframe national identities.6 Furthermore, Janev (2011) explores the narratives around the built environment of the Macedonian capital of Skopje to argue that the state structuring of the city reflects its ethnocratic spatial orientations. These approaches serve to present a two-fold insight into the dynamics that connect cities and states in post-socialist societies. First, they show how state interventions and discourses structure the spatiality of the city. Second, they underscore the intimate connections between the narratives of the city and attempts at nation-building, which ground specific discourses, ethnocratic orientations, and articulations into the national space of the country. Thus, a genealogical investigation of spatiality measurably goes beyond the space reviewed to draw in wider scales of national identity in and across space.

It is in this context that Lefebvrian insights on the production of space (Lefebvre, 2009) offer a structured approach to investigating spatiality (Schmid, 2008; Wiedmann and Salama, 2019). Lefebvre proposes that spatiality is triad among representations of space, representational space, and spatial practice (Lefebvre, 2009). There is little ambiguity in how representations of space, representational space, and spatial practice have been mapped as conceived, perceived, and lived space (Pierce and Martin, 2015; Stojanovic, 2017). However, these ambiguities do not result from theoretical confusion on Lefebvrian productions of space. Rather, these differences point to the complex means by which no one element between conception, perception, and daily experience exists in isolation (Leary-Owhin, 2015). Zhang (2006) contends that these elements are overlapping frames describing the same spatial reality. Spatiality is, therefore, not a political constitution; rather, it is a specific “output” out of contestations, struggles, and differentiation within representations of space, representational space, and spatial practices (Elden, 2007).

For Lefebvre, representations of space relate to tangible aspects such as urban plans, policies, and state technocratic engagements in space. However, representations of space should go beyond the narrow purview of policy assessment. Instead, representations of space extend to narratives, orientations, and discourses that frame state engagement (Lefebvre, 2009). A genealogical investigation can be carried out by critically interrogating how these representations of space come to be constituted and how they differentiate themselves from other articulations of space. While Lefebvre encourages us to think of how these representations shape the space of the nation, thinking with Lefebvre and Isin invites an analysis of how these representations contribute to constructing spaces as internal others—as alterity-space. Section two demonstrates how these discursive representations of space create hierarchies of space itself.7

Furthermore, Lefebvrian representational space captures the symbolic and contested meanings of space, drawing in diverse actors and groups. Representational space is a discursive arena engendering active and passively coded symbols that structure the socially produced reality of space. Thinking with Lefebvre and Isin invites an analysis of how these representational spaces are articulations of specific contestations, differences, and hierarchies among and between groups (Isin, 2002). In this context, the representational space of a city (or nation) is constructed from contestations among competing discourses, narratives, and symbolisms. Section two demonstrates how these contestations frame hierarchies of space within a nation, coding spaces of the nation and creating mechanisms of exclusion for other spaces.

Furthermore, spatial practices reflect everyday human activities, emphasizing how people’s experiences shape and relate to space.8 For Lefebvre, this third element of the spatial triad contributes to the production of space by synthesizing representations of space, representational space, and daily experience (Simonsen, 2005; Watkins, 2005; Lefebvre, 2009). As section two demonstrates, spatial practices further contribute to contestations and hierarchies of belonging, framing inclusion and exclusion of spaces into national narratives.

Alterity-space draws from the spatial insights of Isin and Lefebvre by exploring the relationship among citizens, alterity, the city, the state, and the nation. Collectively, these insights inform how genealogical investigations of spatiality can be undertaken. At stake is the recognition that:

1. Alterity-space draws on Isin’s insights into citizenship and its constitutive other through its distinction from the immediate, internal other (alterity).

2. Alterity-space centralizes the spaces of the city as articulations of state and national space.

3. Lefebvrian insights present a roadmap to unpack the spatiality of Alterity-space through investigations of representations of space, representational space, and spatial practice. Namely through:

a. An investigation of state technocratic engagements that shape spatiality.

b. An investigation of the narratives that render national identity visible in space through nation-building and branding strategies. Alterity-space as a concept, therefore, invites reflection on how state engagement, narratives, and interactions produce spatiality and simultaneously create mechanisms of “othering” that obscure other articulations of space.

c. A contextualization (and mapping) of competing, contested, and hierarchical narratives within the city (and space) that frames alterity-space in difference to spaces of the city and national space. These narratives draw from discourses, symbolism, and practices that populate city space and relate to the overall space of the nation.

To exemplify this concept, a case study of the contestations and hierarchies that frame Lasnamäe as an alterity-space in contrast to the national space of Estonia is presented.

This section illustrates alterity-space through an investigation of Lasnamäe’s spatiality. First, Lasnamäe is contextualized as an urban space in Tallinn. This is followed by a discussion on how spatiality has been methodologically mapped through expert interviews and narrative analysis. Furthermore, this section outlines four themes that define national space in Estonia: an Estonian cultural space, historical and future connections to Europe, a technologically advanced digital landscape, and a lush green forest scape. Collectively, these themes position Lasnamäe as an uneasy outsider marked by either a Russophone or fragmented cultural sphere, historical connections to soviet aggression, and a stagnant and ecologically ugly space within the capital and the nation (see Figures 1, 2).

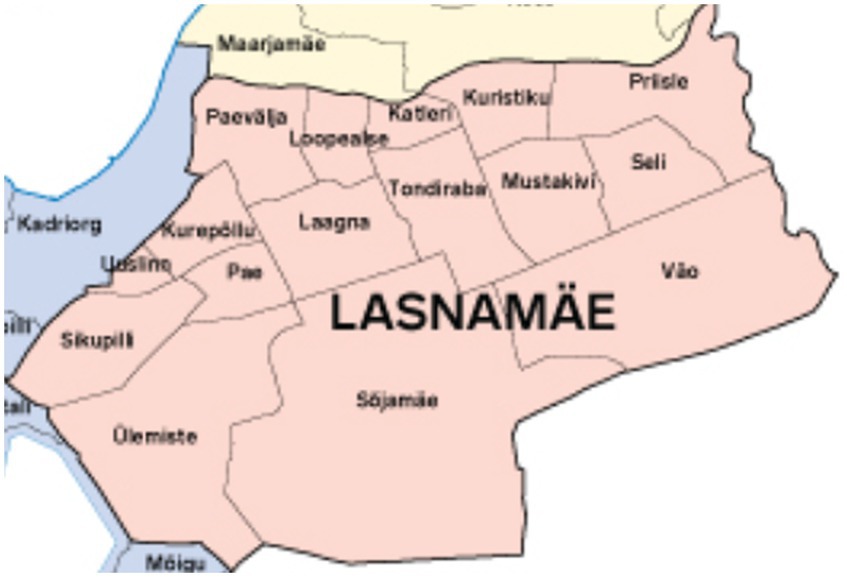

Figure 1. District map of Tallinn (n.d.) (source: Tallinn planeeringute register, https://tpr.tallinn.ee/).

Figure 2. Sub-districts of Lasnamäe (n.d.) (source: https://www.tallinn.ee/et/lasnamae).

Lasnamäe, Mustamäe, and Õismäe are three districts in Tallinn set up during the soviet occupation of Estonia. Kährik and Tammaru (2010) contend that these districts are typical of soviet planning featuring standardized high-rise apartment complexes. Although all three districts were constructed in the 1970s, Lasnamäe is often set apart from Tallin’s urbanism and Estonian national identity. Furthermore, Ruoppila and Kährik (2003) argue that Mustamäe and Õismäe have escaped the externalizing attitude found toward Lasnamäe.9 This sets the stage for an exploration of Lasnamäe as an alterity-space.

Lasnamäe was set up in the 1970s as an industrial worker town comprising 11 districts in typical soviet architecture of high-rise panel blocks of flats (Metspalu and Hess, 2018). Today, it is the most populous administrative district in the capital.10 Lasnamäe has also undergone significant developments since independence and now consists of 16 sub-districts. One such district - Ülemiste, has become a hub for modern digital industries, signaling a shift in the economic and social landscape of the area.

Since its inception, Lasnamäe has been inhabited by a predominately Russophone population, a demographic trend that continues into the present (Kährik et al., 2019). In 2021, approximately 70% of the population was from the Russophone minority (Kuulpak, 2021). The demographic characteristics frame the district as predominantly Russophone, contributing to differences between Estonian and Russophone communities in space.11

Lasnamäe is often framed in relation to the ethno-political field of Estonian citizenship. Vihalemm (2007) contends that Estonian society can be charted through two main ethno-linguistic groups: Russophone minorities and Estonians are the dominant majority. She contends that in the context of EU relations, it is becoming increasingly difficult to map a collective term for these minorities, which consists of differentiated identities in relation to Estonia, the EU, and Russia. Petersoo (2007) explores these complex relations to demonstrate how Russophone communities are paradoxically positioned as both exterior and internal others in Estonia. Furthermore, Feldman (2005) explores the construction of Estonia as a nation-state in the post-socialist, Baltic, Finno-Ugric, and Nordic contexts (Berg, 2002; Smith et al., 2002; Salminen, 2009). He contends that Estonian national space is shaped by the omission of its Russophone characteristics. The Russophone population stands as an alterity to Estonians, where Estonian citizenship is articulated through proximities of being away from Russophone communities (Park, 1994; Jašina-Schäfer and Cheskin, 2020).

Lasnamäe’s historical origins and demographic characteristics shape its spatiality apart from Estonian national belonging. These narratives draw on wider socio-cultural, historical, and ecological orientations. Collectively, four overlapping narratives produce the national space for Estonia and the constitution of immediate other spaces of the city along four narratives. Namely:

1. Estonian cultural practices as rightful belonging and cultural others in alterity-space.

2. Temporal continuity for a European past and future at odds with (post)soviet belonging of alterity-space.

3. Modern, digital, and tech-savvy national spatiality in contrast to stagnant alterity-space.

4. Forests as beautiful national space and the limestone blight of alterity-space.

The methodological choices of this research inform how differences of space come to be constituted and placed in hierarchies of belonging as national and alterity-space. To explore how alterity-space is constituted, a narrative analysis of the elements that collectively produce space was undertaken.12 Furthermore, unstructured expert interviews with public figures working across these domains were conducted.

Note that there are ongoing debates about the distinctions between discourse and narrative analysis, with terms often used interchangeably (Andrews et al., 2013). Generally, discourse analysis examines language and syntax (Gee, 2014), while narrative analysis focuses on societal meaning (Lees, 2004). Bal (2004) explores these distinctions through the well-known story of Oedipus. He argues that narrative contextualizes sequences through which meaning is generated while discourse explicates the crucial event of Oedipus killing Laius. Meanings—its hierarchies and orders—lead to the development of events (such as the killing of Laius) that are only underscored in and through the narrative. Hence, narratives serve as the border arena in which meanings are generated, framed, and posited in hierarchies (Bal, 2004). Simply, narrative analysis serves to explore how meaning-making occurs. Nordberg (2006) further argues that narrative analysis in citizenship frames the sense of full citizenship and its exclusions. This research extends Norberg’s analysis to narratives of space’s relation to citizenship. Here, Lefebvrian orientations to spatiality serve as a “methodological typology” to identify narratives across representations of space, representational space, and spatial practices, which collectively frame spatiality. These narratives of Estonian National space, in contrast to alterity-space, are mapped through an analysis of state engagement, competing symbolisms, and interactions. The national space across primary and secondary data is mapped through author-generated codes. This process is done to explore the hierarchies in narration that serve to construct Estonian space as European, medieval, and green in contrast to spaces that “do not fit the bill.” That is, during the data collection phases, the sequence in which narratives of space were invoked was mapped. For instance, in the interviews, it was observed that narratives on Estonian tech-savvy nature followed the explanation of Lasnamäe as a space stuck in time. These contrasts that set the narratives of Lasnamäe apart from the national narrative were data-driven and then merged into the four themes analyzed below. These narratives were contrasted with other narratives that populate Lasnamäe to examine how hierarchies of space are framed and often contested. However, to facilitate a smoother reading, the national Estonian narrative is presented alongside the narratives on Lasnamäe across representations of space, representational space, and spatial practice below.

The state orientation and discourses that frame representations of space were explored through the developmental plans of Tallinn since the early 2000s.13 The following state development plans were reviewed: Tallinn Development Plan 2009–2027, Tallinn Development Plan 2014–2020 (Tallinn City Council, 2008, 2013; Tallinn Master Plan, n.d.). Across these plans, narratives emphasized Tallinn’s entrepreneurial and green future, while Lasnamäe was characterized as a space left behind, requiring revitalization.

Since Estonia is one of the first post-soviet countries to launch a brand strategy for itself (Jansen, 2008), an evaluation of the narratives that punctuate national branding in Tallinn was also investigated. Following Polese et al. (2020), Estonian branding narratives were explored through state websites and strategies promoting tourism, namely Brand Estonia (n.d.) Website, Estonia.ee, and Visit Estonia (n.d.) website were analyzed. Most of these branding narratives resonated with the narratives found in the development plans as green, entrepreneurial spaces. Furthermore, these discourses imbued Tallinn and Estonian national space with European legacy. These narratives on the representation of space were triangulated in relation to the themes from the interviews with state actors.14 To account for the plurality of actors that discursively structure representations of space in Lasnamäe, special instances of public speech were analyzed.

A similar approach was utilized to map the prevailing narratives of representational space that are pervasive in Estonian space and Lasnamäe. These cultural, symbolic, and discursive orientations were mapped through purposive and exhaustive sampling stemming from a 4 year period of cultural embedding in Tallinn by the researcher. Films, songs, and digital media with explicit reference to Lasnamäe15 were analyzed. Themes framing Estonian national identity and space in relation to Lasnamäe were explored through the Halt Lasnamäe song of the Estonian singing revolution (Kõrver, n.d.). Furthermore, discourses on soviet spatial configurations were analyzed through the popular book Sugisball (Autumn Ball) by Unt (1979), which is set in the urban backdrop of Mustamäe, and the film of the same name (Autum Ball, 2007) set in Lasnamäe (Õunpuu, 2007). Furthermore, through the analysis of the contemporary film Tenet (Nolan, 2020), the representational space of Lasnamäe was analyzed. Across these popular representations, the narrative around soviet-built environments is one framed as depressing, gray, and bleak. These orientations were contrasted with other grassroot and city-based projects, namely the urban.ee project (2013) and the Estonian Academy of Art project (2018). These projects sought to present a positive assessment of Lasnamäe as a space for community interactions and as embedded in the spatial context of Tallinn.

A Lefebvrian orientation to spatial practice requires exploration of the social elements that populate space (see Simonsen, 2005; Lefebvre, 2009). To explore this social arena for the users of space (Butler, 2012), an analysis of civil society engagement and district tourism activities was conducted. This was complemented by examining the main themes that frame public social media in Lasnamäe, namely the social media pages of Meie kaunis Lasnamäe’s (n.d.) Facebook group (our beautiful Lasnamäe) and Lasnaidee (n.d.). Note that the spatial practice of private residents was not mapped by interviews in Lasnamäe.16 There are two reasons for this methodological choice. First, to examine articulations of citizenship and national belonging, only publicly available and pervasive narratives were mapped. Second, the counter-narratives that dominate Lasnamäe serve as clear examples of how national and alterity-space are intimately connected, contested, and imagined. Future research should explore how various discourses and competing modes of thought frame contestations within each triad (competing voices within representations of space, representational space, and spatial practices). Yet, such an undertaking would obscure how contestation, hierarchy, and difference contribute to the constitution of national and alterity-space.

The interviews served to determine the prevalence of these narratives in shaping Lasnamäe’s spatiality.17 These respondents were chosen because of their prominent role in relation to elements of the spatial triad discussed above. Note that a relatively small number of interviewees were chosen for their prominence. Even though the space investigated is much larger, the aim was to triangulate themes that emerged from narrative analysis on various aspects of the Lefebvrian triad discussed above. Furthermore, note that the overall number of public actors actively engaged in the space is small—since the region investigated is just one urban district among many in Tallinn, Estonia. The interviews were utilized to gauge how these discourses permeate space and to assess how public figures, state actors, and others contribute to discursive framings of space. These interviews produced exhaustive themes that have been analyzed below.

The rationale for interviewing these experts is described below:

1. A long-term (over 15 years) policy expert specializing in Tallinn urban policy to triangulate researcher-generated themes on the representations of space in Tallinn.

2. An ex-governor (and ex-long-term resident) in Lasnamäe will triangulate researcher-generated themes on representations of space and representational space in Lasnamäe.

3. Two prominent real estate agents who are active in the region gain an in-depth understanding of beyond-state actors in representations of space.

4. An ex-member of Lasnamäe city council and currently a local activist who has been active in the district for over 10 years to triangulate researcher-generated themes on representational space and spatial practices in Lasnamäe.

5. A civil society member of Lasnaidee (n.d.) to explore and triangulate representational space, discursive practices, and spatial practices that shape Lasnamäe’s spatiality.

Estonian spatial narratives often emphasize a culture deeply rooted in European heritage, the ecological richness of dense forestry, and modern infrastructure. This portrayal contrasts with Lasnamäe, which is shaped by its soviet and Russophone characteristics and appears disconnected from Tallinn’s past, future, and Estonia’s natural landscapes. These four themes collectively frame Tallinn’s spatiality and Estonian national space as different from the space of Lasnamäe.

The ethno-linguistic characteristics of Lasnamäe signify the space as one predominately catering to the Estonian alterity.18 These alterities in space contribute to framings of space itself imbued with Russian culture. Through two intertwined narratives of cultural affiliation, Lasnamäe is subtly positioned as an internal other distinct from other regions in Tallinn. First, spatiality in Lasnamäe is portrayed as a Russophone cultural arena clashing with Estonian cultural space. Second, it is constituted as a space of fragmentation distinct from a unified Estonian culture.

Lasnamäe’s spatiality is discursively characterized as a predominately Russophone cultural arena. In all development plans reviewed, the state problematizes its high Russophone population compared to other city districts. Roberto and Korver-Glenn (2021) further investigate Lasnamäe’s racially segregated spatial patterns, emphasizing its physical and social Russophone features. Furthermore, Seljamaa (2016) notes that in Lasnamäe, Russian typically serves as the primary language, unlike other Tallinn areas where Estonian dominates. Similarly, the representational space of Lasnamäe is framed in distinctions between Estonian and Russophone populations where historically Russophone minorities are cast as alterity. This is reflected in the Halt Lasnamäe song:

“…Look, everything is totally foreign -is this our home then? In the wind of the streets there is an aimlessly wandering migrant…!”

These otherings extend to contemporary framings of Lasnamäe’s spatiality. Across three interviews,19 Lasnamäe was predominately characterized as a Russophone cultural arena somewhat distinct from other spaces in Tallinn where Estonian linguistic and cultural practices are etched on space.

In addition, Krivy (2022) argues that Lasnamäe plays home to many different identities beyond Russophone culture. Through these articulations of difference, Lasnamäe’s spatiality also appears as a discursively distinct arena in Tallinn. For instance, Derlõš (2021) explores municipal housing projects in Lasnamäe, problematizing the relationship between space and community. These concerns resonate in the interview with the ex-council member.

“In my experience few people join the Facebook group of Lasnamäe, but if you look at the group of Nomme, many people are there.” (Interview source: ex-council member and current public activist).

In and through these narratives, Lasnamäe’s spatiality inadvertently contrasts Estonian cultural values and belonging to space. These narratives not only reinforce the national space of Estonia as predominately Estonian but contribute to the framing of Lasnamäe as an alterity-space that is either too Russophone or too fragmented to be part of the national narrative.

Furthermore, complex articulations of European belonging frame Lasnamäe as an alterity-space in Estonia.

Estonia’s succession into the EU has been seen as a return to Europe, marking a break from a past dominated by Russian aggression (Lagerspetz, 1999; Feldman, 2001). Michelson and Paadam (2016) further examine how the space of Tallinn is cast as an authentic European and medieval town. Even though Tallinn’s cityscapes continue to reflect a broad spectrum of architectural and historical juxtapositions, Tallinn’s identity is constructed through its medieval and current modes of belonging to the West and European tourism (Näripea, 2009). In this context, spaces marked by a different historical trajectory stand as apparent outsiders in constructing national identity (Hwang, 2017). Soviet and post-soviet legacies are constructed as a rupture against the continuity of a larger European past (Sommer, 2019). For instance, in the visit to the Estonian branding website,20 the historical continuity of Estonia is traced back to the early Vikings and extended to medieval Europe, jumping to a modern independent Estonia. At the same time, there is no mention of the period of soviet occupation and its structuring of spatiality. When the spatiality of Lasnamäe is discussed in national branding, the historical context of its built environment is also obscured. Consider how the space of Lasnamäe is described on the state tourism website:

“The construction of Lasnamäe started in the 1970s and it is still ongoing. Even though its reputation is not the best, it is a peaceful district …. On the other side of Lasnamäe is Jüriöö Park (St George’s Night Park), which is like a textbook of earlier Estonian history.… The mood is much brighter at the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds, located right next to Lasnamäe and the grand Kadriorg Park. It was under this arch that the Estonians sang themselves free for good.” (Source: https://www.visittallinn.ee/eng/visitor/ideas-tips/tips-and-guides/the-hills-of-tallinn).

Medieval aspects of Estonian history are invoked, and the significance of space is highlighted in relation to modern Estonian independence. In these ebbs and flows, (post)soviet spatiality is either omitted or framed as an external imposition in contrast to an older enduring legacy of Tallinn and Estonia. However, these omissions do not exist in all narratives of Estonian national space. A somewhat different narrative of historical (dis)continuity can also be found. For instance, Tallinn Masterplan 2035 contextualizes Lasnamäe, Mustamäe, and Õismäe as micro districts envisioned during the soviet occupation. Yet, these classifications do not create historical continuity from the medieval European era to the soviet era and beyond. Rather, these narratives serve as a backdrop to showcase the external imposition of soviet planning. This sentiment of foreign imposition is aptly reflected in the song Halt Lasnamäe:

“Let’s go up to the mountains, Musta-, Õis- or Lasnamäe, look down into the soul of the people through a foreign power…” (source: Halt Lasnamae song)

While the song has not been brought up in public discourse lately, it is not just a relic of history. In 2019, the minister of culture referenced the song during the Estonian Independence Singing Festival. Emphasizing the importance of conserving singing grounds from urban development, he suggested the possibility of singing “halt Lasnamäe” once more (Nael, 2019). This call underscores a contrast between spaces symbolic of independent Estonia and urban structures seemingly at odds with Estonian history. Furthermore, in comparing Lasnamäe to other districts in Tallinn, the ex-city council member describes the difference between historical continuity and discontinuity.

“Kalamaja has kept many of its fisherman town features, but this sort of history does not exist in Lasnamäe which was only made when the soviets came.” (Interview source: ex-city council member).

Kalamaja21 appears embedded in a longer history of Hanseatic heritage, whereas Lasnamäe stands as a foreign imposition of soviet aggression. The ex-city council member further adds:

“When you look at Nõmme you can clearly see the beautiful architecture and the effects of this German lord, but when you look at Lasnamäe there is nothing.” (Interview source: ex-city council member)

Through these narratives, the spatiality of Lasnamäe appears at odds with medieval European history, which frames other districts in Tallinn. These discourses on medieval heritage are also utilized in national branding.

“… The story of Nõmme is inseparable from its founder, the charismatic landowner Nikolai von Glehn, and his fantasy world…” (source: https://www.visittallinn.ee/eng/visitor/see-do/neighbourhoods/n%C3%B5mme).

These narratives of historical (dis)continuity are contested through representational space and spatial practices in Lasnamäe. The ex-governor reflects on this by arguing the need to embed Lasnamäe in a continuous history before the soviet occupation. He discusses ongoing walking tours of Sikupilli,22 where old wooden architecture resonates with medieval legacy in contrast to brutal soviet prefabricated housing. Furthermore, activists seek to break these hierarchies of historical continuity that frame national space through medieval heritage, casting other spaces as “external” and foreign to national space. Through a 3 years research project led by the Estonian Academy of Arts (2018), the space of Lasnamäe was explored in relation to Tallinn. The project aimed to embed modernist urban blocs within historical continuity and future relevance in the city to challenge discourses that cast such spaces as external. This orientation is shared by the civil society leader, who also argues that diverse NGO initiatives embed Lasnamäe as a historically internal space while highlighting how the region can be a “learning space for urban experimentalism” and the future of Tallinn. Collectively, these (counter)narratives seek to internalize the spatiality of Lasnamäe. The civil society activist points to gardening initiatives that have become a core activity of the NGO since the early 2000s.

“…the success of this [gardening initiatives] has brought people together and these are now being picked up in Kopli and Nõmme…” (interview source: member Lasnaidee).

These narratives and contestations position Lasnamäe as an integral spatiality shaping Tallinn’s urban past and future. In and through these contestations, the spatiality of Lasnamäe is constituted by the difference in the spatiality of the city and the nation. In this context, the contestations that constitute Lasnamäe’s spatiality through “rupture” from a European past and future serve as mechanisms of framing spatialities within the city in hierarchies of belonging between national space and alterity-space.

Just as the spatiality of Estonian national space is framed in distinction from Russophone, soviet, and post-soviet heritage, today, it increasingly embraces a tech-savvy, entrepreneurial, and neoliberal mindset. This obscures and silences alternative spatialities that connect the city and the nation.

Estonia prides itself on being a Fortier in e-governance, digital citizenship, and tech-savvy industry with an enterprising spirit. These narratives permeate Estonian national branding as well (Kimmo et al., 2018; Kerikmäe et al., 2019). The website brand.Estonia.ee showcases these narratives in Estonian national space:

“In Estonia, clean and untouched nature co-exists with the world’s most digitally advanced society. It is a place for independent minds where bright ideas meet a can-do spirit.” (Source: our story, brand.estonia.ee).

“…digital society, …, clean environments” (source: our core messages, brand.estonia.ee)

Such narratives shape hierarchies of space between modern and run-down areas that obscure alternative narratives of belonging to national space. In contrast to the tech-savvy spaces of Estonia, Lasnamäe is often cast as run-down, stagnant, and in need of revitalization. This is evident in the policy engagement in the region. In the early 1990s, a queer silence can be seen in the spatial planning of the district, although other regions received attention (Hess and Tammaru, 2019). This silence is punctuated by policy proposals aimed at urban renewal across Tallinn from the 2000s onwards, focusing on entrepreneurial investment. For instance, in the Tallinn Development Plan 2014–2020, Lasnamäe infrastructural developments are invoked in relation to the promotion of creative entrepreneurial space and public order. Here, the focus is maintained on revitalizing spaces. These narratives reflect state values where the space of Tallinn is envisioned through modern entrepreneurial activity, and the spaces at odds with this narrative require revitalization and intervention. Krivý (2021) argues that the state employs such perspectives to promote a unique neoliberal version of the nation, obscuring other forms of spatial belonging to the nation.

Furthermore, the interview with the ex-governor illustrates how state articulations frame hierarchies among spaces (Lefebvre, 2003). Reflecting on newspaper reporting, he states:

“If you look at the reports of traffic accidents and petty crimes [between 2000-2010] you would very rarely see where in Tallinn this happened, although, if it happened in Lasnamäe, you can be sure it would be mentioned.” (Source: interview with ex-governor of Lasnamäe).

He further suggests:

“This is what is still contributing to people thinking that Lasnamäe is dangerous, even though if you look at the actual police reports you would see that the highest crime regions are in the old town.” (Source: interview with ex-governor of Lasnamäe).

These representations contribute to framing the space of Lasnamäe as different than Tallinn. Such narratives, coupled with modern films,23 depict Lasnamäe as a bleak, run-down, stagnant space. This sentiment is shared by the ex-city council member and the civil society activist, arguing that such films create negative orientations toward Lasnamäe.

“…I think the film still has some effect on how people think but they don’t see all the details because they don’t come here.” (Interview source: member Lasnaidee).

Similarly, the ex-city council member highlights the diversity within Lasnamäe to demonstrate how not all regions fit the narratives of being run-down and stagnant.

“…if you look at these sorts of films you would not notice that Ülemiste is part of Lasnamäe also.” (Interview source: ex-city council member of Lasnamäe).

He points to Ülemiste, an entrepreneurial business hub equipped with offices of digital companies, to demonstrate how the narratives on Lasnamäe as stagnant, run-down, and outdated do not reflect the reality of space. Collectively, these narratives on Lasnamäe frame the spatiality of the region as an immediate other to the entrepreneurial, digital, and tech-savvy national space of Estonia.

Even more telling are the narratives that frame Estonian national space as ecologically green spaces with thick, lush, untouched forests. Heinapuu (2018) examines the sacred sites of Estonia to conclude how the traditions of sacred ecological landscapes have historically been passed down and invented traditions, consolidating a national ecological identity. The emphasis on ecological connectedness and its contrast consequently creates distinctions between national space and alterity-space. Across all six interviews, a stark differentiation between the natural environments of wider Estonia emerges in relation to Lasnamäe as an ecological blight marked by high limestone hills and low green areas.

“… The city is just like an abscess on a limestone surface—the eye cannot see the end of it. Let’s all shout down to the valley now with all our strength: Stop Lasnamäe” (source: Song; Halt Lasnamäe).

Lasnamäe stands distinctly apart from the carpeted, lush, green Estonian forest scape. Similarly, newer greener public spaces initiatives, highlighting the ecological beauty of Lasnamäe’s limestone hills, appear as contestations seeking to dislocate hierarchies of space where forest scapes are favored in national imagery and other ecological landscapes are omitted from national space.

In short, it is evident that in constructing a national, European, digital, and forested national space of Tallinn and Estonia, the spatiality of Lasnamäe itself becomes an alterity-space. The alterity-space of Lasnamäe is cast as a cultural other, signifying a soviet and a historical imposition at odds with Tallinn’s past and future in Europe. In these narratives, the geographical features of space itself—rocks, hills, and forests—also become entrenched with narratives where space either “fits” the nation or stands apart from the national imagery.

An investigation of Lasnamäe as alterity-space is not an automatically determined reality whereby it exists in contrast to the cityscape of Tallinn or Estonian identity. It must be imagined, maintained, and discursively reframed through historical continuities, discontinuities, and the future of branding tourism, identity, and national space in Estonia.

This research has explored the intimate connections between spatiality, citizenship, and national space through the conceptual lens of alterity-space. This research invites reflection on how thinking with and beyond the performative turn in citizenship widens the scope of citizenship studies to examine constitutions of national space itself. Through such an investigation, previously distinct works of literature on nation-building, national branding, state narratives, contestations of space, and impacts on citizenship can be brought into a comprehensive investigation of national space and its exclusions.

While thinking with Isin has invited exploration of citizenship, alterity, the city, and the state, thinking beyond Isin in dialogue with Lefebvre has presented the possibility of investigating national spatiality itself. This facilitates an investigation of how national space, usually viewed as a coherent whole, is in fact configured in complex hierarchies and differences. Alterity-space has been posed as an explicit spatial tool in the genealogical investigation of the city where differences and hierarchies of spatiality shape articulations of belonging and exclusions of space itself in the nation. Alterity-space, therefore, offers a robust framework for understanding the intricate ways in which spaces within a city can scale to national identity and the broader space of the nation.

This concept of alterity-space is exemplified through a case study of Lasnamäe in the Estonian capital. The investigation of Lasnamäe has provided a concrete instance of how a locality can embody the complexities of this relationship where national narratives and their exclusions are framed and contested. The spatiality of Lasnamäe as an alterity-space demonstrates how Estonian national space is envisioned through ecological, digital, and European narratives, which obscure and exclude spaces and spatiality at odds with these orientations.

The findings underscore the potential of alterity-space as a powerful tool for examining the genealogies that underpin national space and its intimate connections to articulations of citizenship, identity, alterity, belonging, and hierarchies of space in national articulations of space.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by Tallinn University Ethics Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under grant agreement No. 857366.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^Also, institutions and actors within the nation.

2. ^Although post-socialist scholars are exploring state roles in (re)configuring citizenship in national space, see Isaacs and Polese (2016).

3. ^For a detailed discussion on constitutions of citizenship in relational thought, see Vetik (2023).

4. ^The investigation is not meant to deny the complex configurations in which human dynamics and contestations frame citizenship. Rather, it is to widen the arena by seeing space as a constitution/contestation of citizenship.

5. ^See Isin (2004, 2009, 2019) on the neurotic subject, the activist citizen, and other identities.

6. ^His analysis is based on debates around the shift of the Kazak capital city from Almaty to Astana.

7. ^Framing national space in contrast to internal spaces apart from national history, legacy, and the future.

8. ^Both by shaping space and being shaped by space.

9. ^This reflects how spatiality is an actively constructed social product which frames districts in the city through differences and hierarchies.

10. ^Home to approximately 26% of Tallinn’s total population (Tallinn Statistics Yearbook, 2021).

11. ^This also points to the intimate connection between alterity in space, where space is a medium of difference, and space as alterity, where space is an outcome of difference.

12. ^Data on Lasnamäe were drawn in relation to representations of space, representational space, and spatial practice. For a similar methodological approach, see Shaharyar (2023)

13. ^Policy engagement and its narratives from 1990 to 2000 inferred from a tertiary source (Metspalu and Hess, 2018).

14. ^The policy specialist, ex-governor, and ex-member of the city council described below.

15. ^Or based in Lasnamäe.

16. ^Allows emphasis on the common, competing narratives which frame arenas of inclusion and exclusion, rather than an emphasis on how space is experienced by its residents.

17. ^These interviews were conducted via purposeful sampling and snowballing techniques where their visibility as a public figure in relation to Lasnamäe was the rationale for their inclusion.

18. ^Various Russophone identities.

19. ^Interviews with the policy expert, the ex-governor, and the real estate agents.

20. ^Especially the main page and the writings under history of Estonia.

21. ^Categorized as a medieval fishing port and contemporary “artistic” space (Ruoppila, 2005).

22. ^A sub-district in Lasnamäe that was inhabited before soviet occupation.

23. ^The film Autumn Ball (Sugisball 2007) and Tenet movie (2020).

Andrews, M., Squire, C., and Tamboukou, M. (Eds.) (2013). Doing narrative research. London, United Kingdom: SAGE.

Aronczyk, M. (2007). “New and improved nations: branding national identity” in Practicing culture (New York: Routledge), 105–128.

Bal, M. (Ed.) (2004). Narrative theory: major issues in narrative theory. Routledge, UK: Taylor & Francis.

Berg, E. (2002). Local resistance, national identity and global swings in post-soviet Estonia. Eur. Asia Stud. 54, 109–122. doi: 10.1080/09668130120098269

Bottery, M. (2003). The end of citizenship? The nation state, threats to its legitimacy, and citizenship education in the twenty-first century. Camb. J. Educ. 33, 101–122. doi: 10.1080/0305764032000064668

Brand Estonia. (n.d.) Brand estonia. Available at: https://brand.estonia.ee/?lang=en

Brenner, N., and Elden, S. (2009). Henri Lefebvre on state, space, territory. Int. Political Sociol. 3, 353–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-5687.2009.00081.x

Butler, C. (2012). Henri Lefebvre: spatial politics, everyday life and the right to the city. London: Imprint Routledge-Cavendish.

Clarke, J., Coll, K., Dagnino, E., and Neveu, C. (2014). “Re-centering citizenship” in Disputing citizenship. 1st ed (UK: Bristol University Press), 9–56.

Derlõš, M. (2021). “Implementing tenant participation: a case study of Raadiku municipal housing area” in Master’s thesis (Tallinn, Estonia: Estonian Academy of Arts)

Desforges, L., Jones, R., and Woods, M. (2005). New geographies of citizenship. Citizsh. Stud. 9, 439–451. doi: 10.1080/13621020500301213

Diener, A., and Hagen, J. (2013). From socialist to post-socialist cities: narrating the nation through urban space. Natl. Pap. 41, 487–514. doi: 10.1080/00905992.2013.768217

District Map of Tallinn (n.d.). Tallinn planeeringute register. Available at: https://tpr.tallinn.ee/

Drummond, L., and Peake, L. (2005). Introduction to Engin Isin’s being political: genealogies of citizenship. Polit. Geogr. 24, 341–343. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2004.07.001

Elden, S. (2007). There is a politics of space because space is political. Radic. Philos. Rev. 10, 101–116. doi: 10.5840/radphilrev20071022

Estonian Academy of Arts (2018). The City Unfinished Project. Tallinn, Estonia: Estonian Academy of Arts. Available at: https://www.artun.ee/en/curricula/architecture-and-urban-design/unfinished-city/

Feldman, M. (2001). European integration and the discourse of national identity in Estonia. Natl. Identities 3, 5–21. doi: 10.1080/14608940020028466

Feldman, G. (2005). Culture, state, and security in Europe: the case of citizenship and integration policy in Estonia. Am. Ethnol. 32, 676–694. doi: 10.1525/ae.2005.32.4.676

Gross, T. (2002). Anthropology of collective memory: Estonian national awakening revisited. Trames 6, 342–354. doi: 10.3176/tr.2002.4.04

Harvey, D. (1976). Labor, capital, and class struggle around the built environment in advanced capitalist societies. Polit. Soc. 6, 265–295. doi: 10.1177/003232927600600301

Heinapuu, O. (2018). “Reframing sacred natural sites as national monuments in Estonia: shifts in nature-culture interactions” in Framing the environmental humanities (The Netherlands: Brill Publishing House).

Hess, D. B., and Tammaru, T. (2019). Housing estates in the Baltic countries: the legacy of central planning in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Nature Switzerland AG: Springer Nature.

Hwang, S. (2017). “Conflict: conflicting images in Tallinn” in Master thesis (Aalto University) Available at: https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/29495

Isaacs, R., and Polese, A. (2016). Nation-building and identity in the post-soviet space: New tools and approaches. UK: Routledge.

Isin, E. F. (2002). Being political: genealogies of citizenship. Minneapolis, USA: University of Minnesota Press.

Isin, E. F. (2004). The neurotic citizen. Citizsh. Stud. 8, 217–235. doi: 10.1080/1362102042000256970

Isin, E. F. (2005). Engaging, being, political. Polit. Geogr. 24, 373–387. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2004.07.002

Isin, E. F. (2007). City. State: critique of scalar thought. Citizsh. Stud. 11, 211–228. doi: 10.1080/13621020701262644

Isin, E. F. (2009). Citizenship in flux: the figure of the activist citizen. Subjectivity 29, 367–388. doi: 10.1057/sub.2009.25

Isin, E. (2019). Doing rights with things: The art of becoming citizens. Performing citizenship: Bodies, agencies, limitations. Palgrave Macmillan Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 45–56.

Isin, E. F., and Nielsen, G. M. (Eds.) (2008). Acts of citizenship. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Janev, G. (2011). Narrating the nation, narrating the city. Cult. Anal. 10, 3–21. Available at: https://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/~culturalanalysis/volume10/pdf/Janev.pdf

Jansen, S. C. (2008). Designer nations: neo-liberal nation branding–brand Estonia. Soc. Identities 14, 121–142. doi: 10.1080/13504630701848721

Jašina-Schäfer, A., and Cheskin, A. (2020). Horizontal citizenship in Estonia: Russian speakers in the borderland city of Narva. Citizsh. Stud. 24, 93–110. doi: 10.1080/13621025.2019.1691150

Kährik, A., Kangur, K., and Leetmaa, K. (2019). “Socio-economic and ethnic trajectories of Housing Estates in Tallinn, Estonia” in Housing estates in the Baltic countries. The urban book series (Cham: Springer)

Kährik, A., and Tammaru, T. (2010). Soviet prefabricated panel housing estates: areas of continued social mix or decline? The case of Tallinn. Hous. Stud. 25, 201–219. doi: 10.1080/02673030903561818

Kaneva, N. (2011). Nation branding: toward an agenda for critical research. Int. J. Commun. 5, 117–141. Available at: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/704

Kerikmäe, T., Troitiño, D. R., and Shumilo, O. (2019). An idol or an ideal? A case study of Estonian e-governance: public perceptions, myths, and misbeliefs. Acta Balt. Hist. Philos. Sci. 7, 71–80. doi: 10.11590/abhps.2019.1.05

Kimmo, M., Pappel, I., and Draheim, D. (2018). E-residency as a nation branding case. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance. 419–428.

Kõrver, M.. (n.d.). The world of Estonian film. Estonian Institute. Available at: https://www.digar.ee/arhiiv/en/download/112850

Koster, M., Jaffe, R., and Koning, A.de (2018). Citizenship agendas in and beyond the nation-state. UK: Routledge

Kowalski, A., Passell, A., Jessop, B., and Moore, G. (2009). “Space and the state (1978)” in State, space, world: selected essays. eds. N. Brenner, S. Elden, and S. Elden (Minneapolis, USA: University of Minnesota Press), 223–253.

Krivý, M. (2021). “Post-apocalyptic wasteland” or “digital ecosystem”? Postsocialist ecological imaginaries in Tallinn, Estonia. Geoforum 126, 233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.07.007

Krivy, M. (2022). Reclaiming socialist space, caricaturing socialism? Urban interventions and the cleansing of political content in state-socialist public housing after 2008. Antipode 54, 503–525. doi: 10.1111/anti.12782

Kuulpak, P. (2021). Statistical yearbook of Tallinn 2021. Tallinn city government [report]. Tallinn Strategic Management Office.

Kymlicka, W., and Norman, W. (1994). Return of the citizen: A survey of recent work on citizenship theory. Ethics 104, 352–381. doi: 10.1086/293605

Lagerspetz, M. (1999). Postsocialism as a return: notes on a discursive strategy. East Eur. Polit. Soc. 13, 377–390. doi: 10.1177/0888325499013002019

Lasnaidee. (n.d.). Facebook group. Available at: https://z-upload.facebook.com/lasnaidee/groups/?ref=page_internal. (Accessed November 14, 2023)

Leary-Owhin, M. (2015). A fresh look at Lefebvre’s spatial triad and differential space: A central place in planning theory? 2nd Planning Theory Conference University of the West of England 1–8.

Lees, L. (2004). Urban geography: discourse analysis and urban research. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 28, 101–107. doi: 10.1191/0309132504ph473pr

Lefebvre, H. (2003). “State and space” in State/space: a reader. eds. N. Brenner, B. Brenner, M. J. Jessop, and G. Macleod (Edinburgh UK: Wiley-Blackwell)

Lefebvre, H. (2009). State, space, world: selected essays. Minneapolis, USA: University of Minnesota Press.

Meie kaunis Lasnamäe. (n.d.). Facebook group. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/groups/lasnamaepuhtaks/. (Accessed November 14, 2023).

Metspalu, P., and Hess, D. B. (2018). Revisiting the role of architects in planning large-scale housing in the USSR: the birth of socialist residential districts in Tallinn, Estonia, 1957–1979. Plan. Perspect. 33, 335–361. doi: 10.1080/02665433.2017.1348974

Michelson, A., and Paadam, K. (2016). Destination branding and reconstructing symbolic capital of urban heritage: a spatially informed observational analysis in medieval towns. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 5, 141–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.12.002

Nael, M. (2019). Lukas: kui tarvis, laulame uuesti “Peatage Lasnamäe” [Ministers Song Festival speech on agenda, content own idea, say organizers]. ERR NEWS (Estonian Public Broadcasting) Available at: https://kultuur.err.ee/959399/lukas-kui-tarvis-laulame-uuesti-peatage-lasnamae (Accessed March 16, 2024).

Näripea, E. (2009). Tourist gaze as a strategic device of architectural representation: Tallinn old town and soviet tourism marketing in the 1960s and 1970s. In International Conference on Film and Architecture Cinem Architecture. Porto, Portugal.

Nordberg, C. (2006). Claiming citizenship: marginalised voices on identity and belonging. Citizsh. Stud. 10, 523–539. doi: 10.1080/13621020600954952

Nyers, P. (2007). Introduction: why citizenship studies. Citizsh. Stud. 11, 1–4. doi: 10.1080/13621020601099716

Park, A. (1994). Ethnicity and independence: the case of Estonia in comparative perspective. Eur. Asia Stud. 46, 69–87. doi: 10.1080/09668139408412150

Petersoo, P. (2007). Reconsidering otherness: constructing Estonian identity. Nations Natl. 13, 117–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8129.2007.00276.x

Pierce, J., and Martin, D. G. (2015). Placing Lefebvre. Antipode 47, 1279–1299. doi: 10.1111/anti.12155

Polese, A., Ambrosio, T., and Kerikmäe, T. (2020). Estonian identity construction between nation branding and building. Mezinárodní Vztahy 55, 24–46. doi: 10.32422/mv.1690

Roberto, E., and Korver-Glenn, E. (2021). The spatial structure and local experience of residential segregation. Spat. Demogr. 9, 277–307. doi: 10.1007/s40980-021-00086-7

Roy, A. (2012). “Urban informality: the production of space and practice of planning” in The Oxford handbook of urban planning. eds. R. Crane and R. Weber (USA: Oxford University Press).

Ruoppila, S. (2005). Housing policy and residential differentiation in post-socialist Tallinn. Eur. J. Housing Policy 5, 279–300. doi: 10.1080/14616710500342176

Ruoppila, S., and Kährik, A. (2003). Socio-economic residential differentiation in post-socialist Tallinn. J. Housing Built Environ. 18, 49–73. doi: 10.1023/A:1022435000258

Salminen, T. (2009). Finland and Estonia in each other’s images of prehistory: building national myths. Eesti Arheoloogia Ajakiri 13, 3–20. doi: 10.3176/arch.2009.1.01

Schatz, E. (2004). What capital cities say about state and nation building. Natl. Ethnic Polit. 9, 111–140. doi: 10.1080/13537110390444140

Schmid, C. (2008). “Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space: towards a three-dimensional dialectic” in Space, difference, everyday life (New York, USA: Routledge), 41–59.

Seljamaa, E. H. (2016). Silencing and amplifying ethnicity in Estonia. Ethnol. Eur. 46, 27–43. doi: 10.16995/ee.1186

Shaharyar, N. (2023). Towards a newer analytical frame for theorizing ethnic enclaves in urban residential spaces: a critical dialectic approach in relational-spatiality. Environ. Space Place 15, 116–138. doi: 10.1353/spc.2023.a903429

Simonsen, K. (2005). Bodies, sensations, space, and time: the contribution from Henri Lefebvre. Geogr. Ann. B 87, 1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.0435-3684.2005.00174.x

Smith, D. J., Lane, T., Pabriks, A., and Purs, A. (2002). The Baltic states: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. London, UK: Routledge.

Soja, E. (1980). The socio-spatial dialectic. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 70, 207–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1980.tb01308.x

Sommer, Ł. (2019). “Echoes of invented pasts: ethnic self-images in Estonian culture” in Ethnic resonances in performance, literature, and identity. eds. Y. Kalogeras and C. Waegner (New York, USA: Routledge)

Stanek, L. (2011). “Urban society and its architecture” in Henri Lefebvre on space: architecture, urban research, and the production of theory (Minneapolis, USA: University of Minnesota Press).

Stojanovic, D. (2017). Space, territory and sovereignty: critical analysis of concepts. Nagoya Univ. J. Law Polit. 275, 111–185.

Sub-districts of Lasnamäe. (n.d.). Available at: https://www.tallinn.ee/et/lasnamae

Tallinn 2035 (n.d.). City of Tallinn. Tallinna arengustrateegia. Available at: https://www.tallinn.ee/est/g21829s135339

Tallinn City Council. (2008). Development plan of Tallinn 2009–2027. Available at: https://www.tallinn.ee/eng/g26753s124763

Tallinn City Council. (2013). Development plan of Tallinn 2014–2020. Available at: https://www.tallinn.ee/eng/g26753s124764

Tallinn Statistics Yearbook. (2021). Available at: https://www.tallinn.ee/en/media/313036

Vetik, R. (2023). Field relationalism versus process relationalism in citizenship studies. Citizsh. Stud. 27, 365–384. doi: 10.1080/13621025.2023.2171253

Vihalemm, T. (2007). Crystallizing and emancipating identities in post-communist Estonia. Natl. Pap. 35, 477–502. doi: 10.1080/00905990701368738

Visit Estonia (n.d.). Official travel guide to Estonia. Available at: https://www.visitestonia.com/en

Watkins, C. (2005). Representations of space, spatial practices, and spaces of representation: an application of Lefebvre’s spatial triad. Cult. Organ. 11, 209–220. doi: 10.1080/14759550500203318

Wiedmann, F., and Salama, A. M. (2019). “Mapping Lefebvre’s theory on the production of space to an integrated approach for sustainable urbanism” in The Routledge handbook of Henri Lefebvre, the city and urban society (UK: Routledge), 346–354.

Williams, C., and Smith, A. D. (1983). The national construction of social space. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 7, 502–518. doi: 10.1177/030913258300700402

Zhang, Z. (2006). What is lived space? Ephemera 6, 219–223. Available at: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=6414f0864a3a122160b8d79c80113d97d054a5b9

Keywords: alterity-space, Lefebvre and Isin, Estonia, urban space and citizenship, urban space and the nation

Citation: Shaharyar N (2024) Alterity-space: national spatiality in Lasnamäe, Estonia. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1140683. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1140683

Received: 09 January 2023; Accepted: 07 March 2024;

Published: 30 April 2024.

Edited by:

Ian A. Morrison, American University in Cairo, EgyptReviewed by:

Mitch Rose, Aberystwyth University, United KingdomCopyright © 2024 Shaharyar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nawal Shaharyar, bmF3YWxzaDkzQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.