95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 12 January 2024

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1320693

The relationships between ministers and their junior ministers have hardly been addressed in the literature, yet they are crucial to understanding government departmental dynamics. Using a principal agent framework, this article analyses 144 minister-junior minister relationships in three Portuguese governments (2005–2015), uncovering serious divergences (agency losses). The results were obtained through a qualitative approach, using many sources, including 111 interviews with former Portuguese prime ministers, ministers and junior ministers, content analysis, and one Minister's direct observation. It concludes that sharing the decisional power (shared leadership) improves accountability (promoting preference alignment and reducing asymmetric information), preventing and dealing effectively with divergences.

In mid-April 2016, several Portuguese media reported, with great prominence, the resignation of the Junior Minister (JM) for Sport and Youth Affairs. João Wengorovius Meneses left, after less than 5 months in the position, declaring his 'profound disagreement with the Minister of Education, with regard to the policy for sport and youth affairs and the way of holding public office≫. Although the reasons are usually less explicit, conflicts between the Minister and the JM are frequently reported in the press. Situations like this are not unique to Portugal, with concrete cases of conflict between these political actors in several countries (Chabal, 2003, p. 41; Knapp and Wright, 2006, p. 138; Riddell et al., 2011, p. 18; Theakston et al., 2014, p. 18). They represent a problem with an impact on government functioning but also on democracy itself.

The divergences between the Minister and the JM represent a government problem since they jeopardize the policy-implementation performance, contributing decisively to political instability. On the one hand, they limit the government's capacity to act collaboratively and effectively in the policy area. On the other hand, they are at the origin of deselections, leading to successive changes in political orientation during the mandate. They also represent a democratic problem as they distort the link between citizens' will and implemented policies. Indeed, representative democracy can be seen as a sequence of specific delegations between voters and policy implementation (Strøm, 2000). As popular sovereignty is not practiced directly, it implies a delegation to legitimate representatives, who, in turn, can also delegate. At the same time, whoever delegates has the legitimacy to control the delegates' actions, which means that, for example, Public Administration is accountable to the government or the JM to the Minister. Thus, a democratic regime implies accountability, which guarantees consistency between popular will and decisions.

In this context, any failed delegation interrupts the link to the source of democratic legitimacy (Palmer, 1995, p. 169)—the voters—so it is important to analyze the various stages of delegation. Although relevant—and, as we mentioned earlier, possibly problematic—one of the least studied stages is precisely the one concerning Minister and the JM. In Portugal, its study is particularly relevant since JMs play a fundamental role in the daily life of the department and a remarkable role in policy formulation (Lobo, 2005, p. 193; Silveira, 2021, p. 98–102). However, the national literature has mainly focused on ministers (Costa Pinto and Tavares de Almeida, 2018), ignoring the relationship with their main collaborators.

The main objective of this article is to assess the divergences between the Minister and the JM, as well as the role of ministerial leadership in its prevention and management. As there is a latent conflict in the relationship of these actors, only a few face serious divergences that call delegation into question. What justifies this difference is mainly the adoption of traditional leadership instead of shared leadership. The former hinders the JM's accountability, while the latter promotes interaction and teamwork, reinforcing the mechanisms for preventing and resolving disagreements. Therefore, this argument highlights the importance of the type of leadership, which is usually not explored when looking at the democratic delegation chain.

The following section presents the two strands of literature relevant to this research problem. Then, the fundamental methodological choices are presented. A framework for JMs in Portugal is provided in the following section, namely regarding the institutional context, recruitment practices, and autonomy. The following section presents an empirical assessment of the conflict between ministers and JMs in Portugal, distinguishing and quantifying common and severe divergences. After that, it is discussed how shared leadership improves JMs accountability, both ex ante and ex post. Finally, conclusions are stated.

In 1985, Jean Blondel pointed out that studies on ministerial elites were still in their infancy (Blondel, 1985, p. 8). The scenario is significantly different a few decades later, with a remarkable profusion of studies on ministers (Blondel and Thiébault, 1991; Tavares de Almeida et al., 2006; Dowding and Dumont, 2009; Costa Pinto and Tavares de Almeida, 2018). Although the scenario is quite different concerning JMs, studies on these government actors are starting to emerge, particularly considering their role in coalition governments (Thies, 2001; Giannetti and Laver, 2005; Lipsmeyer and Pierce, 2011; Carroll and Cox, 2012; Falcó-Gimeno, 2014; Greene and Jensen, 2016) but also their recruitment profile (Marangoni, 2012; Real-Dato et al., 2013; Silveira, 2016; Vartolomei, 2023) and their length in office (González-Bustamante and Olivares, 2015; Carmo Duarte and Silveira, 2021).

Although some studies admit that JMs perform essential functions (Askim et al., 2018), they tend to look at the position instrumentally, obscuring their role in government and departments (Giannetti and Laver, 2005, p. 98). In this way, they do not allow to obtain a realistic image of the political dynamics involving this position, namely those concerning the relationship with the Minister. The exploration of this relationship has emerged in research devoted to government, ministers or JMs (Theakston, 1987; Searing, 1994; Chabal, 2003; Rhodes, 2011; Theakston et al., 2014). Consequently, only a few pages have been devoted to the specific outlines of the interaction between ministers and JMs.

The only attempt to specifically and systematically explore the relationship between the Minister and the JM was carried out by Real-Dato and Rodríguez-Teruel (2016). These authors concluded that JMs' role has an eminently specialized and policy-oriented nature in Spain, as the recruitment profile of these individuals reveals a high degree of expertise, with political competences and party ties having complementary importance (Real-Dato and Rodríguez-Teruel, 2016, p. 18). More relevant, however, is their contribution to the conceptualization of delegation between a minister and a JM, by using the principal-agent theory (Real-Dato and Rodríguez-Teruel, 2016, p. 3–4).

The theoretical model that regards democracy as a chain of delegation and accountability between voters and Public Administration (Strøm, 2000) does not contemplate Junior Ministers. Nonetheless, in this framework, the JM could be seen as a link in this chain, that is, as someone who acts (agent) on behalf of another (principal), reporting to that individual. Formally, JM should act as agents of their ministers, but the singularity of that relationship could be challenged by the existence of multiple principals, as the prime-minister, the party, the public administration, or interest groups (Real-Dato and Rodríguez-Teruel, 2016). However, in this case, we believe that the critical aspect is to understand the relationship between the agent (JM) and their lawfully principal (minister), allowing us to recognize how that relationship is affected by other actors who act as de facto principals.

Thus, following the analytical model used by Strøm et al. (2003), we look at how accountability ex-ante and ex-post is used to avoid agency losses between ministers and JM delegation relationship. Agency losses occur “when agents take action that is different from what the principal would have done, had she been in the agents' place (Strøm, 2003, p. 61). As in any delegation stage, they could occur due to preference divergences and asymmetric information (Müller et al., 2003, p. 23). In the first situation, the agent (JM) has different objectives vis-à-vis the principal (Minister), and in the second the principal (Minister) has no sufficient information on the preferences, competences and/or behavior of the agent (JM).

To avoid agency losses any principal relies on accountability, which entails the capacity to exert control, demanding information and sanction the agent (Schedler, 1999, p. 17; Strøm, 2003, p. 62). An agent is accountable toward a principal when acts on his behalf and the principal have the right to guide and demand information as well as punish (or compensate) him. Any principal can use a variety of accountability mechanisms to prevent and mitigate agency losses (Lupia, 2003). More concretely, in his relationship with the JM, a minister can use mechanisms such as contract design (i.e., to define in advance the terms of the relationship, aligning the preferences and sharing information a priori) and supervision (i.e., to control the agent's behavior in office, aiming to obtain information and act a posteriori if necessary).

Nevertheless, those mechanisms were never previously studied concerning the minister-JM delegation. As expressly mentioned by Real-Dato and Rodríguez-Teruel (2016, p. 4, 10), their article does not address Minister-JM agency losses, since a broader perspective would necessarily imply the use of another methodology: “Clearly, a complete understanding of the delegation relationship JMs are involved in should require this approach be complemented by the use of direct methods of discovery such as surveys, qualitative interviewing and/or participant observation.” Thus, despite making a vital contribution to theoretically framing the relationship between the Minister and the JM, it leaves fundamental theoretical and empirical questions open. This study follows that challenge, aiming to address the role of JMs in the democratic chain, which implies studying their relationship with the Minister, namely regarding leadership.

Robert Tucker (1995, p. 15) parsimoniously defined leadership as following: 'a leader is one who gives direction to a collective's activities'. Therefore, political leadership refers to the influence of someone in defining the options of the political community, guiding the remaining members (Edinger, 1975, p. 257; Kellerman, 1984, p. 71).

Ministerial leadership is a specific type of political leadership, insofar as it concerns the governing institution and, within its scope, the leadership of each department and respective sub-areas. As in any leadership process, what is at stake is the ability to define the group's direction, which in this case corresponds to the definition of policies in this area of government action (Andeweg, 2014, p. 537). In this sense, ministerial leadership responsibilities imply assuming a pre-eminent role in the political options of the department and, more specifically, of its sub-areas.

The distinction between traditional leadership and shared leadership has emerged as one of the most important distinctions between types of leadership. Traditional (or vertical) leadership refers to the idea that 'one person is firmly “in charge” while the rest are simply followers' (Pearce, 2004, p. 47). It implies, therefore, a relationship of superiority. In this type of leadership, the decisional role is performed by a single individual through a process that tends to be formal and hierarchical (top-down). The leader is solely responsible for guiding the group to pursue collective objectives. Also sometimes referred to as heroic leadership (Yukl, 2009), it relies on the individual leader's abilities (experience, competence, vision, charisma, etc.) to dictate the path to be followed by the group.

In opposition to this classical perspective, shared leadership has been theorized, defined as 'a dynamic and interactive influence process among individuals in work groups, in which the objective is to lead one another to the achievement of group goals' (Pearce and Conger, 2003, p. 286). Wu et al. (2020) synthesized the four essential characteristics that the literature has pointed to shared leadership:

• Multiple: there is more than one actor in charge of leadership responsibilities. Instead of a single leader with superior influence capacity, there is a sharing of the relevant role concerning group guidance (Cox et al., 2003, p.53);

• Informal: actors emerge from the team and take on leadership responsibilities, even if they are formally of lower status. Even if someone is officially designated as the leader, group members perceive themselves as peers (Pearce and Sims, 2002, p. 176; Pearce and Conger, 2003, p. 2);

• Interactive: it presupposes a collaborative interaction process in executing leadership responsibilities. The group's functioning implies teamwork, which entails frequent contact and a fluid exchange of information.

• Dynamic: a relationship of constant mutual influence takes place, where members constructively challenge each other to pursue common goals. There is a permanent lateral influence (among peers), due to the horizontal nature of relationships within the group (Pearce and Sims, 2002, p. 176).

Shared leadership is thus contrary to the typical image of leadership composed of just one individual. Instead, it is a type of leadership where individuals jointly decide who, when and how to hold the wheel, sharing this responsibility throughout the journey. Of course, in shared leadership there is also hierarchical influence, that is, there are always occasions when an individual has prominence over others. However, unlike vertical leadership, it is characterized by an essentially horizontal process (Pearce and Conger, 2003, p. 2).

Considering these features and although usually removed from the ministerial or even political context, the potential of shared leadership was also detected in the public sector (Ansell and Gash, 2008; Ospina, 2017).

This article aims to create bridges between these two separate strands of literature—Minister-JM relationship and shared leadership—to understand if and how shared leadership could help prevent and manage severe disagreements. Considering that these political actors must work together within the department, the previously mentioned features of shared leadership (i.e., multiple, informal, interactive, and dynamic) could be advantageous to create a close, open and horizontal relationship. Such a relationship could benefit both the accountability ex-ante and ex-post, helping avoid and cope with serious divergences (i.e., abnormal antagonistic positions on important issues, considered as such by the actors).

In fact, the literature has emphasized the positive impact of shared leadership on group behavior, namely improving the capacity to face problems and crises (Pearce et al., 2004) and promoting consensus decision-making, which reduces group conflicts (Ensley et al., 2006; Bergman, 2012; Ospina, 2017). Therefore, we expect Minister-JM relationships characterized by shared leadership would be less prone to severe divergences.

The research strategy to evaluate the above expectation is based on the analysis of the relationship between ministers and their JMs, appointed in three Portuguese governments (2005–2015). There are a total of 188 cases in this period. Their systematic analysis allows assessing the extent to which divergences call into question the delegation between ministers and JMs in Portugal. The methodological approach is essentially qualitative, since inferences were generated through a comprehensive interpretation of non-numerical sources and presented in a discursive manner. However, quantification is used to complement and reinforce the conclusions whenever possible.

Most of the sources referred to by Rhodes (1995, p. 32) as useful to study the executive are used. We resort to direct observation, official records of Diário da República (Portugal's official journal), legislative acts, government documents, press, biographies and autobiographies, agendas of ministers and JMs, and data on ministerial recruitment, other secondary sources and, finally, interviews.

Interviews are a key element in this work, as they allowed us to acquire an in-depth perspective on the relationship between the Minister and the JM. Considering the large number of interviews that it was possible to carry out and analyze, we were able to establish consistent patterns and interpret the exceptions. As Heclo and Wildavsky (1974, p. xiii) insightfully emphasized '[t]he cure for ignorance about how something gets done is to talk with those who do it; the cure for the confusion which then replaces the ignorance is to think about what you are told'.

Interviews were carried out with former PMs, ministers and JMs of the XVII, XVIII and XIX Governments, covering three different governments (Supplementary material 1). In the period analyzed (March 2005–October 2015), 181 individuals hold government functions, and we contacted all of them. In the end, we were able to carry out 78 semi-structured interviews (43% of the ministers and JMs appointed). However, since several individuals were appointed more than once between 2005 and 2015, these 78 individuals represent 98 government experiences. This type of interview allowed to ask the same questions to all actors in the same position but, at the same time, to have the opportunity to deepen certain specificities of each case (cf. Supplementary material 2). In this way, comparability and quantification capacity was gained without losing depth.

When it was possible to conduct an interview with the JM or with the Minister, we considered that the relationship was covered. Fortunately, we could interview the Minister and the JM in many cases, allowing an important data triangulation. With 188 cases in the period analyzed, it was possible to cover 144 (77% of the Minister-JM relationships), covering all the ministerial portfolios (cf. Supplementary material 3). The interviews were conducted between October 2016 and July 2017, with an average duration of 60 min. All individuals were guaranteed confidentiality, and they were not attributed authorship of any citation. The interviews were recorded and transcribed, with very few exceptions from former members of the government who did not allow the recording.

In addition to the interviews with ministers and JMs appointed between 2005 and 2015, we conducted 32 exploratory interviews between January and June 2016. The purpose of conducting these interviews was mainly to test the questions, allowing us to rectify inconsistencies and fill gaps. In addition, it made it possible to gain a good knowledge of government and ministerial functioning from an early stage. The choice criterion was essentially the diversity of ministerial and junior ministerial portfolios, the diversity of government type and, in particular, the accumulation of different government experiences. Indeed, as many of these 32 individuals held various positions, it was possible to analyze more than 100 government experiences in an exploratory manner. This fact allowed us to obtain the perspective of individuals who occupied multiple positions and related to various ministers or JMs, in different government contexts.

The interviews were subject to content analysis, using MAXQDA software. Thus, after conducting the exploratory interviews, categories relating to the various subjects under analysis were created. There were 288 categories, which, applied to 111 interviews, totaled 6,034 coded excerpts. The codes were generated using a mixed deductive-inductive approach. They were derived theoretically, considering the research objectives and the delegation and accountability theory. But they were also generated inductively after a first reading of all the interviews, allowing to refine those generated deductively.

Aiming to maximize consistency, a codebook was built, which guided the encoding. In addition, each interview was coded by the author twice at different times, and the discrepancies were later individually addressed, examined, and arbitrated, allowing result validation and standardization. Even if it was impossible to use two coders (in order to maximize inter-coder consistency), intra-coder reliability was high (0,93) and an expert on ministerial elites was used to discuss and validate the codebook and arbitrate the discrepancies. Whenever possible, the data was triangulated through other interviews, news in the press or other sources (such as biographies and autobiographies). The content analysis made it possible to systematize the information and process it more easily. It also allowed to compare different situations, consider alternative factors (such as the department, economic context, individual profile or government), generate more robust patterns and better understand the exceptions. Finally, it allowed us to quantify specific categories, complementing the assumptions generated by the qualitative analysis.

Direct observation of a minister of the XXI Government (2015–2019) was also carried out. Permission was requested to accompany this government member for a week permanently. Thus, with minor exceptions—such as ministerial audiences, meetings with the PM and meetings of the Council of Ministers—we constantly followed the Minister for 5 days. The primary objective was to observe the Minister's interaction with JMs, which took place on several occasions, such as meetings, informal contacts, travel and parliamentary hearings. However, it also allowed for a better understanding of the roles played by government members and the functioning of a ministerial department. In fact, in addition to having been able to follow the Minister, even when he was working alone in the office, it was also possible to circulate around the department, talking to people and observing their daily work.

This access was important as it allowed the questioning of several ministerial actors about the observation. Thus, although the observation duration was less than ideal, it allowed us to understand to what extent those situations were regular, occasional or exceptional. To detect any possible influence of the observation on the results, on the last day, several staff members and the Minister were asked if something that week had been atypical and if they thought someone had acted differently as a result of the observation. It was guaranteed that this did not happen, reinforcing our confidence in the information collected. Notes were made in a journal, where events and the author's perception of what he saw and heard were recorded. Throughout the article, some excerpts are transcribed.

Junior ministers are, according to a seminal definition, “those men and women who constitute the top echelon of the government, directly under or alongside the leaders. Either they are in full charge of a sector of government, or, if they are ≪at large≫ or ≪without portfolio≫, their role is to assist these leaders in the task they determine” Blondel (1985, p. 8). However, under this definition, there are relevant institutional variations. On one hand, even if they are rare, there are political systems without junior ministers (e.g., Denmark). On the other hand, there are junior ministers acting in different institutional settings (particularly concerning the nature of the job and portfolio responsibility).

Regarding the nature of the job, there are political systems where junior ministers are generalists, since they assist their minister in a broad set of ministerial tasks. However, junior ministers are restricted to administrative or political tasks in other countries. Regarding portfolio responsibility, it is useful to distinguish between the national executives who concede to junior ministers a ministerial subarea (and, therefore, they are responsible for a portfolio within the ministry) and those who don't.

Crossing these two important dimensions, we can distinguish four institutional settings. In the first one, junior ministers have a generalist role and hold an intraministerial portfolio. It is the case of Portugal, but also Spain (secretario de Estado), the United Kingdom (minister of state), France (secrétaire d'État) or Chile (subsecretarios). In the second setting, junior ministers are also responsible by a ministerial subarea, but have particular roles (usually linked to parliamentary duties). They can be found, for example, in the United Kingdom (parliamentary under-secretary), Malta (Segretarju Parlamentari) or Australia (assistant minister). In the third institutional setting, they are generalists but did not hold an intraministerial portfolio—as in Italy (sottosegretario), United States (deputy secretary), Austria (Staatssekretär), or Brazil (secretários executivos). Finally, in the fourth setting, junior ministers have particular roles and are not responsible for a specific ministerial subarea. It is the case of countries as Germany (parlamentarischer staatssekretär), Japan (daijin seimukan), Latvia (parlamentārā sekretāre), New Zeland (parliamentary under-secretary) or Canada (parliamentary secretary).

Like the PM or the ministers, JMs are formally members of the Portuguese government (art. 183 of the Constitution). However, they are not part of the Council of Ministers—although they may participate in it, depending on the subject or the absence of the Minister. In the latter case, the JM replaces the Minister and, in those situations, has the right to vote and can also sign legislative acts. Nonetheless, unlike the PM and the ministers, JMs do not have the competences stipulated in the Constitution. Consequently, each government should decide, in its organic law, the nature of their competences. Since the VI Constitutional Government (1980), it has been the practice not to grant original powers to JMs.

Despite the omission of the Constitution, it is assumed that the primary function of JMs is the direct collaboration with the ministers and their replacement (art. 177 no. 1 and 185 no. 2 of the Constitution). It is up to the Minister to stipulate the competences he/she intends to delegate, through a ministerial order. In this way, they are accountable to the Minister, and they cease functions when he/she is dismissed (art. 186.° 3 and 191.° 3 of the Constitution).

This regime aims at the generalist nature of the position, not limited to the performance of a specific task within the department. Instead, JMs assume the same functions as the Minister, in a particular ministerial sub-area. Naturally, they do it in their dependence and following their guidelines.

In addition, as already mentioned, JMs perform their duties in specific sub-areas within the ministerial area. Just as a government department is assigned to each Minister, a ministerial department is assigned to each JM. Although the Minister is formally responsible for the entire department, this sectorial responsibility of JMs makes them, in practice, the governing incumbent of that policy area.

The selection of JMs tends to be restricted to three main actors—the Minister, the PM and, in coalition governments, the party leaders. In Portugal, this choice is mainly up to the ministers (in 72% of the cases analyzed, the Minister was responsible for the choice). It is also infrequent for the PM to veto the Minister's choices, mainly because he/she can justify his/her options to the PM. The Minister's accountability vis-à-vis the PM primarily explains this attitude (Cavaco Silva, 2002, p. 108). For the PM to be able to demand results from ministers, it is advantageous to let them form their own team.

Although the PM tends not to veto the Minister's options, he/she sometimes makes suggestions. In other words, in the first conversation in which he/she invites a minister, the PM can give him/her a name that he/she thinks is particularly suitable for one of the ministerial sub-areas. However, this is not an institutionalized or generalized practice in Portugal, so the PM uses it very sparingly.

In coalition governments, the attribution of ministerial and junior ministerial portfolios to the parties is made in advance, whereby the leaders of the coalition parties are limited to informing the PM of their party's choices concerning ministers and JMs. The PM retains the prerogative of discussing the proposed names, but the margin for vetoes or suggestions is much smaller and used in exceptional cases. Consequently, in these situations, the possibility of the Minister's interference in the decision is much smaller.

Regardless of who chooses, the JM's primary scope of autonomous action is that which concerns the responsibilities expressly included in the legal ministerial delegation. In other words, JMs are truly sovereign, acting freely, in the relationship with the public administrative bodies they oversee and in the specific responsibilities provided for in the legal delegation. In addition to this first sphere of autonomy, which can be called procedural, a second one is more politically relevant, designated as substantive, relating to policy formulation. JMs play a vital role in their sub-area of action in this context. Regardless of being the Minister who usually sets the most generic guidelines, they can autonomously develop these guidelines, intervening decisively throughout the process.

Notwithstanding, there are exceptional cases in which JMs have minimum autonomy over policies, essentially limited to their procedural autonomy. In these cases, the Minister does not allow JMs to play an independent role in policy formulation or they voluntarily forego that role, involving the Minister in all the actions concerning these matters. In addition, even when JMs have significant autonomy over policies, the limit of this autonomy is defined, in the first place, by the importance of the policy and its (predictable) media impact. However, it is up to the JM to decide when to involve the Minister in these cases. Consequently, the JM's criterion does not always correspond to the Minister's.

The Minister and the JM are different individuals, so they necessarily have different perspectives and information on many issues. In other words, it is natural that there are divergences in relationships as intense as those in government functions. In this sense, a 'divergence' refers to any discord between the actors and does not necessarily mean a severe and irreparable conflict. Consequently, the question is not whether or not there are divergences between the Minister and the JM, as they are natural and unavoidable, but what level of seriousness each relationship entails. Data reveal that in 71% (n = 77) of the cases the Minister and the JM only experienced minor divergences. In these situations, divergences had a relative relevance, fitting into the normal disagreements of any work relationship. In fact, both ministers and JMs take small differences concerning points of view naturally, considering them valuable. This acceptance of the difference is important for the JM, who sees its opinion valued, but also for the Minister, who has the opportunity to test the strength of his/her positions. As a former minister of education describes:

[JMs] are people who think by their own heads. I, by the way, couldn't work with a person who didn't think by his/her head and who didn't confront me with disagreements and debate, because then we're not going anywhere. If people say yes to everything, it's not worth it to be several of us! So, it would be enough to have executors and not rulers in that case. And JMs are rulers.

However, in 29% of the cases (n = 32), serious divergences took place in addition to these normal discrepancies. In these situations, the relationship is marked by antagonistic positions on issues considered important by the actors. We are no longer faced with cases where there are small natural frictions, but with circumstances where opinions are extreme on relevant matters and affect the quality of the relationship. This situation is serious since, by having a position radically opposed to that of the Minister, the JM jeopardizes the delegation and, consequently, the democratic chain (Palmer, 1995, p. 169). Considering the importance that JMs have in the daily life of the department and their autonomy, this is a problematic issue in government dynamics. In fact, in many of these serious divergences, the Minister assumes that he/she would have acted otherwise, which typically represents an agency loss (Strøm, 2003, p. 61). An example is that of a former minister for foreign affairs: 'I had some conflicts with a JM who acted differently from what I think the decision should have been or, at the very least, he should have consulted me…'.

The existence of very significant agency losses is equally evident when the JM assumes that he/she consciously acted against the Minister's will. They are, therefore, paradigmatic situations of moral hazard, since the JM's action is deliberately contrary to what the Minister would have undertaken if he/she had been aware of it. In other words, the JM acts with little concern for the Minister's preferences, making, instead, his/her own preferences prevail, taking advantage of and subverting the authority granted by the delegation. In these cases, the JM understands that, in the sub-areas entrusted to him/her, he/she must be able to decide independently of the Minister's will. In the words of a former JM:

Now, saying: '- Maybe he would prefer me to do the opposite, but I think that's better', hey man, this is life, this is life! I have to decide concerning a specific case and, therefore, if she/he trusted me to decide, she/he has to trust my judgment… Of course, then she/he can say that she/he wouldn't do that or that she/he would have thought differently, and so on.

Naturally, JMs act in this way strategically, that is, taking into account the importance they attach to the issues and the anticipation they make of the Minister's reaction. One of the concerns of JMs who assume that they acted consciously against the Minister's will is that this did not happen in matters that implied his/her public accountability. As a former JM states, issues with potential media impact are an autonomy 'red line'. However, in matters that do not imply such public exposure and in which they anticipate the Minister's disagreement, but consider them relevant and within the scope of their competences, JMs can proceed by creating faits accomplis. This behavior, which a former JM calls' stretching the rope a bit', implies that the JM deliberately acts against what he/she believes to be the Minister's preference, creating a new status quo, to which he/she must adapt. In the next section, we argue that those behaviors are held accountable when the Minister and JM share the ministerial sub-area leadership.

Considering the relationships between ministers and their JM's in the period 2005–2015, traditional leadership was adopted in 57% of the cases (n = 66), and shared leadership in 43% (n = 50). In the latter, the Minister and the JM worked as a team, had permanent contact, frequently discussed and decided together the junior ministerial portfolio issues. On the contrary, when the leadership was vertical, they worked separately, with scarce interaction, and decided strictly according to their expected and legal role.

As previously mentioned, one of the advantages of shared leadership is the reduction of conflicts within the group (Ensley et al., 2006; Bergman, 2012). As there is an effective sharing of management responsibilities, the members feel co-responsible for good team functioning. There is a mutual concern to settle differences with permanent communication and an attempt to reach consensus. But to what extent does shared leadership inhibit divergences between the Minister and the JM?

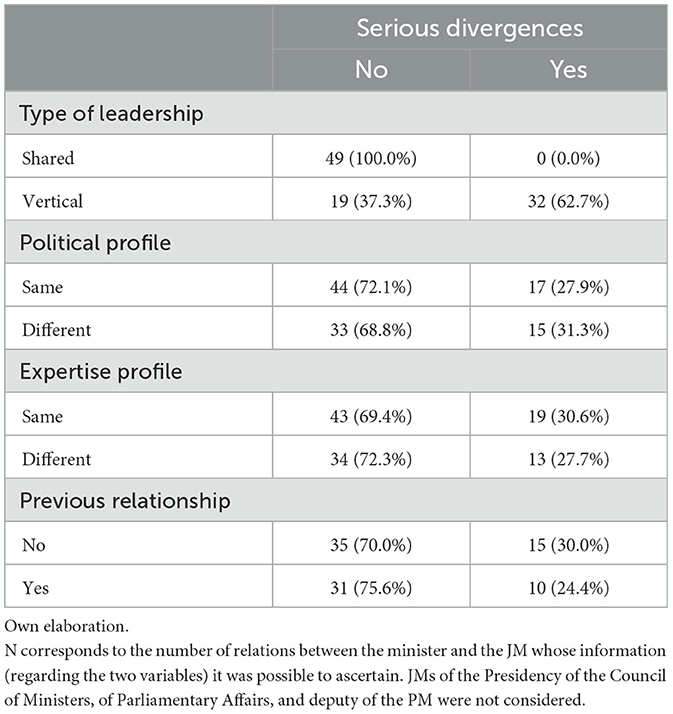

As presented in Table 1, no serious conflicts were found in shared leadership Minister-JM relationships. Considering that in each relationship there are tensions, the potential to serious divergences is present. However, whenever a relationship was simultaneously multiple, informal, interactive and dynamic there were typical divergences but no severe ones. On the contrary, serious disagreements are not inevitable when traditional leadership exists but are far more likely. The potential for conflict is present in every relationship, but assuming a shared leadership benefits the prevention and management of those conflicts, avoiding serious divergences.

Table 1. Occurrence of serious divergences according to the type of leadership and other potential factors.

These results remain when we consider other potential factors, such as the portfolio, the type of government or the individuals' profile. Regarding the latter, distinct political experiences (for example, a minister with political background and an outsider JM) do not generate much more severe divergences. Likewise, different expertise is not a relevant factor, since serious divergences are even slightly higher when both are experts or generalists. Additionally, there were less severe divergences when the Minister and the JM previously knew each other, but the difference is not significant. Finally, belonging to another party in a coalition government does not appear to be a pertinent factor since, if we consider the 16 serious divergences in the coalition XIX Government, in 11 the Minister and the JM were members of the same party. Even if the small number of observations should call for a cautious conclusion on this last factor, the results do not suggest its relevance.

We also considered other potentially relevant factors—as the ministry, the context, the parties, or the personalities. It was inevitable, as many interviewees single out their experience as exceptional—because their ministry was different, the government was in office in unusual times, or someone had some atypical personality. Thanks to the high number of interviews, we reached the opposite conclusion: there is a great equivalence between the concrete cases. As we had the chance to interview ministers and junior ministers that had very different offices and governed in very different circumstances, it was possible to disregard those conditions. Much more important that the specific circumstance, the selection and profiles of the actors, or their initial relationship, it is which kind of leadership is present in each ministerial subarea.

Contrary to other factors, shared leadership facilitates JM's ex-ante and ex-post accountability. On the one hand, it enables the alignment of information and preferences, that is, the promotion of contracting, good supervision and the effective resolution of existing typical disagreements. On the other, it allows for dealing with the potential problems of other factors, such as the actors' profiles. In fact, considering the interpretation of the actors on the divergences in the ministry, it became clear how essential is leadership, even in relationships with very different perspectives a priori (e.g.: different parties or expertise). Shared leadership prove to have the capacity to promote that alignment through effective accountability.

The interactive and dynamic nature of shared leadership makes it natural that, from the beginning, the Minister and the JM settle on some of the essential issues of the relationship. In this way, it promotes the existence and effectiveness of contracting, namely concerning the legal ministerial delegation, the definition of relationship rules and programmatic objectives. This is particularly useful when they do not know each other or have very different profiles, allowing to detect and overcome any preference divergence or asymmetric information early.

When the Minister and the JM share leadership, the legal ministerial delegation tends to be broad—as the Minister foresees a close relationship between the two—and negotiated—as there is a horizontal relationship. Thus, on the one hand, the Minister does not see the legal delegation as a strategic division of tasks, aiming to weight the formal competences of each one. On the other hand, by considering JMs essentially as peers, he/she considers, when delegating, the interests, competences, and specific objectives of each one to maximize individual satisfaction and collective performance.

Likewise, shared leadership benefits the relationship contracting. Actors feel more comfortable informally and directly addressing all the practical issues they deem relevant, namely those relating to autonomy and supervision. Regardless of whether individuals know each other or not, shared leadership allows for the creation, from the outset, of an environment of closeness, openness and permanent dialogue. This favors conversations about the relationship and prevents disagreements about each person's role in later stages of policy formulation. Furthermore, the Minister tends to listen to the JM, formulating the rules together, without prejudice to his/her ascendant in creating work routines. Shared leadership encourages the joint construction of the relationship, which benefits satisfaction with the established rules.

As for programmatic contracting, it is promoted by sharing leadership insofar as it promotes the a priori definition of a common political agenda. Regardless of whether individuals have their own goals, the consensus on these goals is encouraged in a joint plan. In the words of a former JM of Culture:

I felt that, since our first conversation, our dialogue was spontaneous. I did not feel that “Our objectives are these and I hope you, as a JM, followed them.” No. It was more like hear me and, in dialogue, reach certain conclusions and priorities on Culture policy.

This room for incorporating the perspectives of the Minister and the JM is created by the horizontality of the relationship, in which an informal dynamic and mutual influence replace the formal ascendant. In these cases, proximity facilitates, from the beginning, the existence of several and in-depth conversations about general guidelines, priorities, calendar and political strategy.

In addition to positively influencing contracting, shared leadership also benefits supervision. Having more than one individual with leadership responsibilities implies a permanent contact. Unlike traditional leadership, in which only one assumes leadership roles—even though they occasionally discuss issues of general orientation—shared leadership implies a broad and permanent debate. This interactivity allows both to be aware of all the relevant processes, as its definition entails a joint intervention. This situation is described by a former JM as follows:

We had to work together every day. Every day. There was hardly a day that I and the Minister, or the other JM and the Minister, or possibly the three of us, didn't have to be working on problems together, or agenda problems, previously scheduled, or problems that nevertheless arose. So, there was, in this aspect, very close proximity.

In this way, shared leadership presupposes and encourages intense supervision, as neither the Minister nor the JM is detached from the other's work, avoiding information asymmetry. On the contrary, they work as a team, among peers, with continuous sharing of information, ideas and solutions. In these cases, direct contact is very strong. This type of leadership implies regular meetings, but also a more permanent and informal type of contact. In fact, periodic (and even regular) meetings occur in traditional leadership, but these are essentially the only moments of discussion between the Minister and the JM. If anything comes up during the week, it is saved for the periodic meeting unless it is very urgent. Much of the communication between the Minister and the JM is, in these cases, ensured by their staff, making continued debate much more difficult. On the contrary, in shared leadership, meetings—often collective—are just another moment for discussion, as the contact is very intense daily. As a former minister remarked, passing through the office, meals or phone calls are an essential part of this constant interaction:

Every week we would meet, usually a work meeting followed by lunch, for four, where we would bring up the various subjects and talk. And I, obviously, as it was my obligation, was always, always available—I had to be!—to talk to them at any time about any topic. And so, many times, they would knock on my door, call me and, if not right there, because I was talking to someone or dealing with something, within half an hour, I would be talking to them about it.

It is important to bear in mind that this level of supervision is only tolerable without jeopardizing the JM's autonomy and satisfaction due to the informal and dynamic nature of shared leadership. By being treated as a peer, the JM does not feel that the Minister meddles in his/her affairs, but rather that he/she allows for an environment where he/she hears and is heard, the decision being reached by consensus. In other words, the aim is to find a common solution to a common problem, reaching it according to rational (political, economic or otherwise) arguments and not of authority.

Consensus is essential to understand how the sharing of leadership between the Minister and the JM avoids serious disagreements. Small differences are natural, so the great asset of shared leadership is the ability to integrate this latent conflict into a decision-making system that tends toward consensus. Even when Minister and JM are very different, they accommodate those differences. The decision results from an open discussion, where each can convince the other of their point of view. The result is a solution in which both participate and can be comfortable with (and defend externally). Indeed, as stated in the Direct Observation Journal (Day 3, p. 29–33):

4:00 pm: Meeting with JM [name] and JM [name]. Each brings a deputy from their office, as it is a policy-making meeting that concerns the two sub-areas. […] Discussion is never confrontational, in the sense of choosing sides and arguing from that. It's something more fluid, with convergences, doubts, suggestions, specifications and, at times, a consensus among the various participants. The Minister intervenes little, except when he/she outlines or defends a solution. He/she does not make syntheses of the solutions the others, but he/she is also far from imposing his/her own. These are built gradually as a result of the debate.

As already mentioned, a relationship characterized by shared leadership does not exclude occasional situations of verticality. At certain specific moments or at an impasse in the discussion, the Minister can take the final decision to him/herself, but this is not the rule. In shared leadership, what is common is that there is a compromise that allows for accommodating different perspectives when there is a disagreement. Therefore, it allows for constant communication (avoiding asymmetric information) and an effective alignment of choices (avoiding preference divergences).

As JMs are the Minister's closest political collaborators, a good relationship between them is fundamental for the executive and the department in particular. Nevertheless, they may have other options and diverge on fundamental issues, generating agency losses. This article aimed to understand to what extent these divergences occur between ministers and JMs in Portugal and how these actors prevent and deal with them. Through an essentially qualitative analysis, based on a multiplicity of sources, it concludes that the type of leadership has a fundamental impact on the existence of serious divergences. When the Minister and the JM adopt a traditional hierarchical leadership of the ministerial sub-area, serious disagreements are more frequent, while they do not occur when leadership is shared (i.e., multiple, informal, interactive, and dynamic).

This difference is due to the ability of shared leadership to activate accountability mechanisms ex ante and ex post. On the one hand, it encourages the construction of common goals, regardless of their profiles or previous relationship. The sharing of leadership presupposes that both are responsible for the sub-area, which implies tracing together the direction it will take from an early stage. In this way, the definition of a political project in which the preferences of both are taken into account, debated and improved is promoted. Although due to the profile, trust or any other factor, there are different initial perspectives, shared leadership encourages their contracting in an open, informal, and horizontal way. By doing so, it favors preference and information alignment a priori.

On the other hand, permanent interaction makes it possible to identify any slight divergence that arises and resolve it so that the various perspectives can be accommodated. This fluidity of information, combined with the constant search for compromise, makes the starting point of the discussion relatively indifferent. Even if there are initial disagreements, the point of arrival will tend to be a joint decision, in which both sides were considered. When both have the opportunity to forge the decision, the divergence is diluted in the discussion. Consequently, it allows for avoiding any asymmetric information risk.

In this way, this article contributes to revealing the importance of political leadership in the governmental department's functioning. It thus covers an empty space in the literature, as not only the relationship, in general, and the divergences, in particular, between the Minister and the JM were scarcely addressed, as shared leadership had not yet been used as a political variable. It values the role of institutions in framing and rationalizing political actors' behavior but adds a new perspective to it, which values individual and relational dynamics.

These results relate primarily to Portugal but may be useful in future comparative analyses or in countries where JMs play a role similar to the Portuguese one. They can also constitute a first step in exploring shared leadership in different contexts (e.g.: prime-minister and vice-prime-minister or party leader and vice-party leader) and advance to examine its causes in the political arena. If anything, this article intended to pave the way to reveal how leadership could be significant in a critical political institution such as the executive.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

PS: Writing – original draft.

The author thanks FCT for the PhD Grant (SFRH/BD/92483/2013) and to Praxis - Centro de Filosofia, Política e Cultura for the publication support (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/05451/2020).

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2023.1320693/full#supplementary-material

Andeweg, R. B. (2014). “Cabinet ministers: leaders, team players, followers?” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Leadership, eds. R.A.W. Rhodes, and P. 't Hart (Oxford, Oxford University Press), 535–547.

Ansell, C., and Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Admin. Theory Pract. 18, 543–571. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mum032

Askim, J., Karlsen, R., and Kolltveit, K. (2018). The spy who loved me? Cross-partisans in the core executive. Public Admin. 96, 1–16. doi: 10.1111/padm.12392

Bergman, J. Z., et al. (2012). The shared leadership process in decision-making Teams. J. Soc. Psychol. 152, 17–42. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2010.538763

Blondel, J., and Thiébault, J.-L. (1991). The Profession of Government Minister in Western Europe. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press.

Carmo Duarte, M., and Silveira, P. (2021). Viver (brevemente) para a Política: Independência Partidária e Durabilidade da Elite Governativa Portuguesa. Análise Social. 240, 442-469. doi: 10.31447/AS00032573.2021240.02

Carroll, R., and Cox, G. W. (2012). Shadowing ministers monitoring partners in coalition governments. Comp. Pol. Stud. 45, 220–236. doi: 10.1177/00104140114213

Chabal, P. M. (2003). Do ministers matter? The individual style of ministers in programmed policy change. Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 69, 29–49. doi: 10.1177/0020852303691003

Costa Pinto, A., and Tavares de Almeida, P. (2018). “The primacy of experts? Non-partisan ministers in Portuguese democracy,” in Technocratic Ministers and Political Leadership in European Democracies, eds. A. Costa Pinto, M. Cotta, and P. Tavares de Almeida (Oxford, Palgrave Macmillan), 111–138.

Cox, J., Pearce, C. L., and Perry, M. (2003). “Toward a model of shared leadership and distributed influence in the innovation process,” in Shared Leadership: Reframing the Hows and Whys of Leadership, eds. C. L. Pearce, and J. A. Conger (Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications), 48–76.

Dowding, K, and Dumont, P. (2009). The Selection of Ministers in Europe: Hiring and Firing. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Edinger, L. J. (1975). The comparative analysis of political leadership. Comp. Pol. 7, 253–269. doi: 10.2307/421551

Ensley, M. D, Hmieleski, K. M., and Pearce, C. L. (2006). The importance of vertical and shared leadership within new venture top management teams: Implications for the performance of startups. Leadership Q. 17, 217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.02.002

Falcó-Gimeno, A. (2014). The use of control mechanisms in coalition governments The role of preference tangentiality and repeated interactions. Party Pol. 20, 341–356. doi: 10.1177/1354068811436052

Giannetti, D, and Laver, M. (2005). Policy positions and jobs in the government. Eur. J. Pol. Res. 44, 91–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2005.00220.x

González-Bustamante, B, and Olivares, A. (2015). Rotación de subsecretarios en Chile: una exploración de la segunda línea gubernamental (1990-2014). Revista de Gestion Publica. 4, 151–190. doi: 10.22370/rgp.2015.4.2.2230

Greene, Z, and Jensen, C. B. (2016). Manifestos, salience and junior ministerial appointments. Party Pol. 22, 382–392. doi: 10.1177/1354068814549336

Heclo, H, and Wildavsky, A. B. (1974). The Private Government of Public Money: Community and Policy Inside British Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kellerman, B. (1984). “Leadership as a political act,” in Leadership: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, Ed. B. Kellerman (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall), 63–89.

Lipsmeyer, C. S, and Pierce, H. N. (2011). The eyes that bind: junior Ministers as oversight mechanisms in coalition governments. J. Polit. 73, 1152–1164. doi: 10.1017/S0022381611000879

Lupia, A. (2003). “Delegation and its Perils,” in Delegation and Accountability in Parliamentary Democracies, eds K. Str?m, W. C. M?ller, and T. Bergman (Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press), pp. 33–54.

Marangoni, F. (2012). Technocrats in government: the composition and legislative initiatives of the Monti government eight months into its term of office. Bull. Italian Pol. 4, 135–149.

Müller, W. C., Bergman, T., and Strøm, K. (2003). “Parliamentary Democracy: Promise and Problems,” in Delegation and Accountability in Parliamentary Democracies, Eds. K. Strøm, W. C. Müller, and T. Bergman (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 3–33.

Ospina, S. (2017). Collective leadership and context in public administration: bridging public leadership research and leadership studies. Public Adm. Rev. 77, 275–287. doi: 10.1111/puar.12706

Palmer, M. S. R. (1995). Toward an economics of comparative political organisation: examining ministerial responsibility. J. Law Econ. Org. 11, 164–188.

Pearce, C. L. (2004). The future of leadership: combining vertical and shared leadership to transform knowledge work. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 18, 47–57. doi: 10.5465/ame.2004.12690298

Pearce, C. L., and Conger, J. A. (2003). “All those years ago: the historical underpinnings of shared leadership,” in Shared Leadership: Reframing the Hows and Whys of Leadership, Eds. C. L. Pearce, and J. A. Conger (Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications), 1–18.

Pearce, C. L., and Sims, H. P. (2002). Vertical versus shared leadership as predictors of the effectiveness of change management teams: an examination of aversive, directive, transactional, transformational, and empowering leader behaviors. Group Dynamics Theory Res. Pract. 6, 172–197. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.6.2.172

Pearce, C. L., Yoo, Y., and Alavi, M. (2004). “Leadership, social work, and virtual teams: the relative influence of vertical versus shared leadership in the nonprofit sector,” in Improving Leadership in Nonprofit Organisations, Eds. R. Riggio, and S. Orr (San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass), 180–203.

Real-Dato, J., and Rodríguez-Teruel, J. (2016). Politicians, experts or both? Democratic delegation and junior ministers in Spain. Acta Politica. 5, 492–516. doi: 10.1057/ap.2016.6

Real-Dato, J., Rodríguez-Teruel, J., and Jerez-Mir, M. (2013). The Politicisation of the Executive Elite in the Spanish Government: Comparing Cabinet Ministers and State Secretaries, Paper Presented at XI Congreso Español de Ciencia Política y de la Administración. Sevilla: Universidad Pablo Olavide.

Rhodes, R. A. W. (1995). “From prime ministerial power to core executive,” in Prime Minister, Cabinet and Core Executive, Eds. R. A. W. Rhodes and P. Dunleavy (New York, NY: St. Martin's Press), 11–37.

Rhodes, R. A. W. (2011). Everyday Life in British Government. Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Riddell, P., Gruhn, Z., and Carolan, L. (2011). The Challenge of Being a Minister. London: Institute for Government.

Schedler, A. (1999). “Conceptualizing Accountability” in The Self-restraining State: Power and Accountability in New Democracies, Eds. A. Schedler, L. Diamond, and M. F. Plattner (Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers), 13–28.

Searing, D. (1994). Westminster's World: Understanding Political Roles. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Silveira, P. (2016). To be or not to be a politician: profile and governmental career of Portuguese junior ministers. Revista Española de Ciencia Política. 40, 13–38.

Silveira, P. (2021). Os Secretários de Estado: Conflito e Liderança no Ministério. Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais.

Strøm, K. (2000). Delegation and accountability in parliamentary democracies. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 37, 261–290. doi: 10.1023/A:1007064803327

Strøm, K. (2003). “Parliamentary democracy and delegation,” in Delegation and Accountability in Parliamentary Democracies, Eds. K. Strøm, W. C. Müller, and T. Bergman (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Strøm, K., Müller, W. C., and Bergman, T. (2003). Delegation and Accountability in Parliamentary Democracies. Oxford, New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Tavares de Almeida, P., Costa Pinto, A., and Bermeo, N. (2006). Quem Governa a Europa do Sul?: o Recrutamento Ministerial, 1850-2000. Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais.

Theakston, K., Gill, M., and Atkins, J. (2014). The ministerial foothills: labour government junior ministers, 1997-2010. Parliamentary Affairs. 67, 688–707. doi: 10.1093/pa/gss054

Thies, M. F. (2001). Keeping tabs on partners: the logic of delegation in coalition governments. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 45, 580–598. doi: 10.2307/2669240

Vartolomei, E. L. (2023). Profiles and careers of state secretaries in the 132nd government of Romania. Perspect. Pol. 16, 169–178. doi: 10.25019/perspol/23.16.0.16

Wu, Q., Cormican, K., and Chen, G. (2020). A meta-analysis of shared leadership: antecedents, consequences, and moderators. J. Leadership Organ. Stud. 27, 49-64. doi: 10.1177/1548051818820862

Keywords: ministerial department, junior ministers, ministerial delegation, executive leadership, shared leadership

Citation: Silveira P (2024) The benefits of shared leadership on minister-junior minister delegation and accountability. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1320693. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1320693

Received: 12 October 2023; Accepted: 21 December 2023;

Published: 12 January 2024.

Edited by:

Eric E. Otenyo, Northern Arizona University, United StatesReviewed by:

David Shock, Kennesaw State University, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Silveira. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pedro Silveira, cGVkcm8uc2lsdmVpcmFAdWJpLnB0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.