94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 04 January 2024

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1291890

This article is part of the Research TopicLobbying in Comparative ContextsView all 5 articles

Research from parliamentary countries suggests that lobbyists tend to focus their attention on public office holders within the executive government more than those within the legislative branch. To date, however, research studying executive-lobbying relations tends to treat “the executive” and “lobbyists” as two homogenous groups. Yet importantly, not all executive personnel and lobbyists are the same. The executive is made-up of popularly elected politicians, partisan advisors and non-partisan bureaucrats, who vary in their skills, motivations, responsibilities and power within government. Differences also exist in the level of expertise and political representativeness between in-house and consultant lobbyists. Using longitudinal data between 2015 and 2022 from Canada's Lobbyist Registry, this article digs deeper into the executive-lobbying nexus by examining the number of contacts consultant and in-house lobbyists have with different executive personnel—ministers, partisan advisors, senior public servants and non-senior public servants. Although the data shows no meaningful variation tied to differences across partisan-political and administrative personnel within the executive, there is substantive variation in lobbying intensity between upper and lower ranked executive personnel; in-house lobbyists lobby senior political and senior administrative personnel twice as much as consultant lobbyists. These findings are consistent with theory on the expertise and representative function some lobbyists possess, more so than theory emphasizing differences between partisan-political and administrative personnel within the executive.

A longstanding belief among political scientists is that because the executive branch of government has a great deal of control over the legislative agenda within parliamentary countries, lobbyists tend to focus their attention on the executive to the neglect of the legislative branch (Pross, 1986; Montpetit, 2002; Vining et al., 2005; Boucher and Cooper, 2021a). While recent empirical studies from the venue choice lobbying literature show that lobbyists in parliamentary countries target executive public office holders more than legislative personnel (Pedersen et al., 2014; Boucher, 2015, 2018; Boucher and Cooper, 2021b), this literature, both in its theoretical and empirical approach, tends to treat “the executive” and “lobbyists” as two homogenous groups. Yet importantly, there are significant differences in the type of personnel who make-up the executive government, as well as differences in the nature of lobbyists.

Drawing upon research in public administration (Dahlström and Lapuente, 2017), public policy (Craft, 2015), and political science (Bøggild, 2015; LaPira and Thomas, 2017) including lobbying venue choice literature (Scheiner et al., 2013; Vesa et al., 2018), we argue that there are good theoretical reasons to postulate that executive focused lobbying within parliamentary countries is not a unidimensional dyad, but instead is multifaceted, with varying executive-lobbyist relationships stemming from different types of public office holders and lobbyists. If researchers were to dig deeper into executive-lobbying in parliamentary countries by exploring differences in executive personnel and lobbyists, what might they see?

This article contributes to our understanding of lobbying within parliamentary countries by doing just this; moving beyond conceptualizing executive-lobbying relationships as a unidimensional dyad comprised of two homogenous entities, to instead, theorize about, and empirically investigate, varying executive-lobbying relationships stemming from differences among executive public office holders as well as among lobbyists. Specifically, within the executive branch of government, we distinguish between: (1) elected ministers; (2) partisan advisors; (3) senior public servants; and (4), non-senior public servants. All of whom vary in their skills, motivations, responsibilities (accountability) and power within the executive. Second, drawing upon recent research on lobbying (LaPira and Thomas, 2017; Boucher and Cooper, 2019), we distinguish between consultant and in-house lobbyists, who vary in their expertise, government connections and political representativeness.

Using longitudinal data between 2015 and 2022 from the Canadian Lobbyist Registry, this article empirically analyzes the number of contacts in-house and consultant lobbyists have with ministers, partisan advisors, top-ranking public servants (Deputy Ministers, Associate Deputy Ministers and Assistant Deputy Ministers) and non-senior public servants. The results show substantive differences in the nature of executive-lobbyist relationships. Specifically, lobbying targeting top-rank executive personnel (ministers and senior public servants) is predominantly undertaken by in-house consultants, whereas lobbying contacting lower-rank partisan advisors and non-senior public servants is largely undertaken by consultant lobbyists.

At a general level, the results support our central argument: the executive-lobbying relationship in parliamentary countries is not unidimensional; meaningful variation exists in the intensity with which different categories of executive public office holders meet different types of lobbyists. At a more specific level, however, variation in the executive-lobbying relationship does not appear to stem from differences between partisan-political (minister and partisan advisors) and administrative personnel (senior and non-senior public servants). Rather, the variation we observe in our data is more consistent with differences stemming from a logic of access (top ranking ministers and senior public servants vs. lower ranking political-partisan and administrative staff). The greater access in-house lobbyists have with the senior most political and administrative personnel within the executive that we observe among our data is consistent with the theoretical stance that in-house lobbyists possess greater expertise and representative legitimacy (of the organization/interests they are lobbying on behalf of), than that possessed by consultant lobbyists.

This study contributes to lobbying research in parliamentary countries by empirically showing important variation in the executive-lobbying relationship, and offering a theoretical explanation for such variation tied to the level of expertise and representativeness some lobbyists possess, while suggesting that differences between executive personnel along the classic politics-administration dichotomy are likely not as important (Beyers and Braun, 2014; Cooper and Boucher, 2019). This article also contributes to the lobbying literature on venue choice (McKay and Yackee, 2007; Naoi and Krauss, 2009; Jordan and Meirowitz, 2012; Rommetvedt et al., 2013; Scheiner et al., 2013; Pedersen et al., 2014; Vesa et al., 2018) by focusing on different options available to lobbyists within the same institutional venue (the executive) as well as paying attention to whether lobbyists' venue choice varies according to the professional type of lobbyist.

The remainder of this article is organized into four sections. The first section reviews what we know about lobbying in parliamentary countries, before drawing upon research in public administration, public policy and political science to outline why we think distinguishing between categories of executive personnel as well as different types of lobbyists might improve our understanding of executive-lobbying relationships. The second section describes the data and methods used to explore possible variation in executive-lobbying relationships. The third section presents the empirical results and discusses their implications for our understanding of lobbying within Canada and parliamentary countries more generally. The conclusion reviews the central findings of this study, considers its limitations, as well as how future studies could advance our understanding of executive-lobbying relationships in parliamentary countries.

To date, a good body of empirical research supports the classic claim that interest group lobbyists seek points of access to power within the legislative process (Almond, 1958; Baumgartner et al., 2009). Over the last 10 years a number of studies from presidential and parliamentary countries have sought to identify and better understand lobbyists' venue choice within the labyrinthian and dynamic legislative process when seeking political influence (McKay and Yackee, 2007; Naoi and Krauss, 2009; Jordan and Meirowitz, 2012; Rommetvedt et al., 2013; Scheiner et al., 2013; Pedersen et al., 2014; Vesa et al., 2018).

Consistent with rational choice neo-institutionalism (Kato, 1996), this research provides strong support that the nature of a country's formal political institutions influences lobbyists' venue choice. In presidential systems, like the United States where the legislative branch has a great deal of influence, lobbyists have stronger incentives to the legislature (Baumgartner et al., 2009; Dockendorff and Lodato, 2023; Jieun and Stuckatz, 2023), meanwhile in parliamentary systems, where the executive has a great deal of control over policy (O'Malley, 2007; Thomas and Lewis, 2019), lobbyists tend to primarily target the executive (Boucher, 2015). And more precisely, studying lobbying contacts in Canada, where the locus of executive power is highly concentrated in the hands of the prime minister rather than Cabinet (Savoie, 1999; Cooper, 2017), Boucher (2018) finds that a great deal of lobbying focuses on central agencies, and in particular, the Office of the Prime Minister.

Yet for scholars of parliamentary countries, knowing that lobbyists tend to target public office holders working in the executive is perhaps only telling us so much. The executive is not a homogenous body, nor are all lobbyists the same. As we explain below, understanding differences in the skills, motivations, responsibilities and power among different types of executive government personnel, as well as differences among lobbyists who vary in their expertise, government connections and political representativeness, leads us to think that there might be varying executive-lobbyist relationships even within predominantly majoritarian parliamentary systems of government found in Westminster countries such as Canada.

A key distinction among members of the executive government is between elected politicians, appointed partisan advisors and nonpartisan career public servants. On the one hand, from a classic understanding of the Westminster administrative tradition (Savoie, 2003; Cooper, 2021), distinguishing between these actors should not make much of a difference when it comes to understanding the executive-lobbying relationship. Executive-lobbying relationships might in fact be understood as a unidimensional dyad between executive personnel and lobbyists.

First, traditional literature of policy advisory systems in Westminster countries sees partisan advisors as holding the same interests as politicians (Craft, 2013; Craft and Halligan, 2017). In Westminster countries, partisan advisors are nominated by their respective minister, and like ministers, their position within the executive is generally only as certain as that of the elected politician for whom they work. As with ministers, partisan advisors have incentives to please the electorate enough that the elected government is returned to power (Craft, 2015). The nature of partisan advisors' work is also more partisan than that of impartial public servants (Eichbaum and Shaw, 2008; Craft, 2013, 2015). Accordingly, from this perspective, for a lobbyist to speak to a partisan advisor would be very similar to speaking to the partisan advisor's respective minister. In sum, we might expect lobbyists to display similar behavior toward partisan advisors as they do toward ministers.

A classic reading of public administration literature within the Westminster tradition also suggests that distinguishing between public servants and politicians might not make much of a difference for lobbyists (Savoie, 2003). It is often said that the public service in Westminster parliamentary countries has “no constitutional personality or responsibility separate from the duly elected Government of the day” (Armstrong, 1985, p. 2). In contrast to the presidential political system (Rosenbloom, 2001), the public service in Westminster countries does not have an independent identity nor any independent political legitimacy from the elected government. Alternatively referred to by some scholars as an “agency-type public service bargain” (Hood and Lodge, 2006), according to this traditional perspective, the public service in Westminster countries is a politically neutral instrument that impartially implements the elected executive's governing agenda. It is possible that for lobbyists, speaking to a public servant, rather than the minister, is equivalent of speaking to an impartial agent rather than speaking to the principal them self (Hood and Lodge, 2006). Accordingly, as with the traditional understanding of partisan advisors, there might not be much difference in the lobbying behavior focusing on public servants and ministers.

Yet on the other hand, more recent theoretical work in public administration (Dahlström and Lapuente, 2017), public policy (Craft, 2015) and political science (Bøggild, 2015; LaPira and Thomas, 2017), including lobbying venue choice literature (Scheiner et al., 2013; Vesa et al., 2018), provides us good theoretical reasons to expect that differing categories of personnel within the executive as well as different types of lobbyists might matter, and influence the nature of the relationship they have with one another.

Differences in the skills, motivations, responsibilities and power among executive personnel lead to two overarching theoretical expectations: One pertaining to the politics-administration dichotomy and the other pertaining to a logic of access.

A primary difference among executive public office holders concerns the professional incentives of politicians, partisan advisors and public servants. Of utmost importance, politicians within the executive are elected by the people, whereas partisan advisors and public servants are not. Partisan advisors are appointed by their minister, meanwhile among public servants, the very top positions are appointed by the first minister (Cooper, 2020), with the appointment of public servants below the top rank overseen by the public service itself.

Importantly, while some researchers claim that Westminster governments have increasingly politicized top ranking bureaucratic appointments by supplanting merit criteria with political responsiveness to the government's policy agenda (Aucoin, 2012), comparative studies suggest that on the whole, the high ranks of the public service in Westminster countries still reflects the principle of merit recruitment (Bourgault and Van Dorpe, 2013; Cooper, 2021). Although one important characteristic among senior public servants is their closer proximity to the political realm of governing with respect to working alongside ministers (Bourgault and Dunn, 2014) than lower ranking public servants. Empirical research from Westminster countries, however, suggests that while political considerations are an inescapable aspect of senior public servants, they are still mindful of upholding impartiality and not becoming overly political-partisan actors (Grube and Howard, 2016).

In sum, the career incentives for public servants in Westminster countries is not as electorally oriented as politicians and partisan advisors who will be more influenced by the electorate's opinion; rather with their appointment and promotion decisions being isolated from electoral politics public servants' incentives are directed to professional norms and standards (Bøggild, 2015; Dahlström and Lapuente, 2017).

In addition to politicians and partisan advisors having stronger electorally influenced career incentives than public servants, another difference among executive personnel is the permanency of their position. Because their position within the executive is contingent on being returned to power at the next election, the temporal vision of politicians and their partisan advisors tends to be more oriented toward the short-term than public servants, who can expect to spend their entire career within the public service (Bøggild, 2015; Dahlström and Lapuente, 2017).

Elected by citizens, politicians have a higher degree of political legitimacy than partisan advisors and public servants. A decision by an elected politician within the executive has a high degree of political legitimacy, not only because they are an elected representative of the people, but, because of the principle of ministerial responsibility within parliamentary systems of government, ministers are politically accountable before the legislative branch of government. In contrast, within the Westminster administrative system, partisan advisors and career public servants have no such political legitimacy to make decisions, nor are they politically accountable before parliament for the actions of their department (Savoie, 2003).

Finally, politicians have less policy expertise than career public servants, who (Ebinger et al., 2019), especially within Westminster administrative countries, are generally appointed and promoted according to merit (Cooper, 2021). Also of note, is that while partisan advisors are more political than career public servants, another school of thought maintains that partisan advisors can have a high degree of policy relevant expertise, and are directly involved in the development of policies (Craft, 2015; Craft and Halligan, 2017).

Given these differences in incentives, expertise and political legitimacy, it might be the case that lobbyists tend to have different relationships with career public servants and politicians. For instance, given politicians' political legitimacy and power within the executive, lobbyists might seek out these individuals rather than career public servants. On the other hand, however, given the greater expertise and permanency of public servants, lobbyists may wish to speak to these actors to discuss the technical details of policies and programs as well as to foster long-term relationships with more stable members of the executive. Meanwhile, because partisan advisors have similar electoral incentives as politicians, but can also have a higher level of policy relevant expertise, they may present themselves as an attractive hybrid to lobbyists straddling some aspects of politicians (electorally minded, indirect political legitimacy) and career public servants (issue expertise).

Such a possibility is consistent with some parliamentary studies examining differences between elected and unelected public office holders. Studying lobbying in Denmark, Beyers and Braun (2014) find that lobbyists who are able to brokerage different interests have more access with elected officials, while such a political skill does not affect an actor's ability to access administrative personnel. Also studying Denmark, Braun (2013) finds that lobbyists' contact with public servants were largely due to entrenched routine behavior. Studying Japan, Scheiner et al. (2013) find that uncertainty about which party will form government in the future is positively related to contacting public servants. Meanwhile, studying Canada, Cooper and Boucher (2019) observe that an increase in uncertainty among policymakers about the technical details of issues leads to an increase in the number of contacts lobbyists had with administrative personnel.

While differences among executive personnel might play a factor in shaping executive-lobbying relationships, so too may differences among lobbyists. Like executive public office holders, not all lobbyists are the same. Furthermore, like executive government personnel, lobbyists also vary in their incentives and professional skills. Again, we think such differences might be important when it comes to understanding executive-lobbyist relationships.

One such difference is between in-house and consultant lobbyists (LaPira and Thomas, 2017; Boucher and Cooper, 2019; Helgesson, 2023). In-house lobbyists are employees of the organization for whom they lobby the government. Because in-house lobbyists tend to work for the same organization for a long period, they possess a high degree of expertise in the policy sector(s) relevant to their organization. Accordingly, in-house lobbyists are favorably situated to develop long-term relationships with executive government personnel, not only because they are permanent employees of their organization, but also, because in-house lobbyists only lobby on behalf of one organization (with restricted interests), they are likely to contact a limited number of government agencies, in contrast to consultant lobbyists who will lobby a wide and diverse range of government agencies, contingent on who hires them for their services. As such, in-house lobbyists might be prone to develop relationships with career public servants who possess, and whose work requires expertise, and whose career, being isolated from electoral influence, is also favorable to developing long-lasting relationships.

Another difference between in-house and consultant lobbyists that might be an important factor for executive personnel is their political representativeness. Political representativeness is a valuable currency when it comes to lobbying the government. The more an actor can claim that they represent the interests of a segment of the population, the more their voice will be of interest to policymakers (Saurugger, 2008). Importantly, in-house lobbyists may possess a higher level of political representativeness than consultant lobbyists. There are two reasons for this. First, as permanent employees of the organization for whom they lobby the government, in-house lobbyists have a stronger tie to their organization than the tie consultant lobbyists have to the organization(s) they lobby on behalf of. Stemming from being a permanent employee for their organization, in-house lobbyists likely also have stronger connections to other organizations and lobbyists within their respective interest sector. As such, in-house lobbyists might not only possess more political representativeness with respect to their organization, but might also possess greater representativeness with respect to the larger policy network their organization finds itself within. Second, research has noted that possessing representativeness before government officials is not only about being able to represent the interests of a larger group of actors, but there is also a social dynamic to representativeness (Kerneis, 2019; Kröger, 2019). As permanent employees, in-house lobbyists have the advantage of fostering long-standing relationships with government officials, and therein, increase their representativeness in the eyes of executive personnel.

A consultant lobbyist, however, is not an official employee of the organization for whom they lobby the government on behalf of. Consultant lobbyists are professional lobbyists who offer their services to any organization. Rather than having in-depth expertise with respect to a specific organization, and the policy sectors related to this organization, consultant lobbyists have been described as “well-connected chameleons” (LaPira and Thomas, 2017), who have pre-existing relationships with government personnel. Consultant lobbyists are also more likely to be “revolving-door” lobbyists (LaPira and Thomas, 2017; Boucher and Cooper, 2019). Being former public office holders (often public servants or partisan advisors, but sometimes also politicians), revolving-door lobbyists use their knowledge of the political/bureaucratic system, and their connections with government personnel, to lobby the government on behalf of any paying customer (Yates and Cardin-Trudeau, 2021).

In sum, based on the recent theoretical work cited above, our central argument advocates for scholars to move beyond approaching executive-lobbying relationships as a unidimensional dyad comprised of two homogenous groups, and to instead consider variation in executive-lobbying relationships stemming from differences in the nature of executive public office holders and lobbyists. The next section outlines the data and research methods we use to explore this possibility.

To explore the possible existence of multifaceted relationships rippling under a seemingly calm unidimensional executive-lobbyist dyad, we use data of communication reports from Canada's federal registry of lobbyists to examine executive lobbying patterns within the Canadian government. We also use computational tools built as part of the Lobbying and Democratic Governance in Canada research project (Boucher and Cooper, 2021b) to code and standardized the dataset. The federal lobbyist registration rules require all lobbyists who have oral arranged meetings with “designated public office holders” to disclose information on their activities in a monthly communication report. Importantly, this allows us to investigate the relationship various types of executive government personnel have with lobbyists. The following categories of federal government personnel fall within the definition of designated public office holder, “ministers, ministerial staff, deputy ministers and chief executives of departments and agencies, officials in departments and agencies at the rank of associate deputy minister and assistant deputy minister, as well as those occupying positions of comparable rank” (Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada., 2022).1

One limitation with this data is that not all lobbying communications are covered by these disclosure rules. The rules do, however, cover a wide range of precise subjects. Specifically, these subjects are:

The development of any legislative proposal, the introduction of any Bill or resolution, or the passage, defeat or amendment of any Bill or resolution, the making or amendment of any regulation, the development or amendment of any policy or program, the awarding of any grant, contribution or other financial benefit, the awarding of any contract. In the case of consultant lobbyists, who are employees of professional firms, they also must file communication reports when they are looking to arrange a meeting between a public office holder and any other person.2

All communication reports within the Federal lobbyist registry are available in open data format on the website of Canada's Commissioner of Lobbying. These reports contain a range of information on lobbying activities, including the name and client organization of lobbyists, the name, position and home institution of the government staff contacted, as well as the precise date of their conversation. Our analysis is based on communication reports filed over a period of just over seven years, stretching from the election of Justin Trudeau's Liberal government in October 2015 to December 2022, when the data was downloaded and standardized.

Since our study examines lobbying activities aimed at members of the executive branch, we excluded lobbying communications with members of legislative bodies. Our analysis focuses on lobbying in line departments and central agencies of the Canadian government.3 We excluded public agencies and crown corporations given that these agencies do not have a minister among their rank, and therefore we would not be able to systematically compare lobbying directed at political and administrative personnel.

We used automated data transformation processes to identify and standardize the term-position of each executive branch member contacted by lobbyists. The Python fuzzywuzzy library for fuzzy string comparison and matching allowed us to standardize near terms, abbreviations and spelling mistakes describing the position held by the executive personnel of the state targeted by lobbyists (such as ministers, deputy ministers, assistant deputy ministers, advisors, presidents, chiefs of staff, directors). Some positions within the data were excluded due to the particular nature of their employment, which falls either within fundamentally apolitical administrative tasks, such as assistants, managers, and administrative agents or officers, or within the international political realm, such as ambassadors and Canadian Army personnel.

The output of this process was a database containing 85, 316 communication reports. These reports account for 123, 765 lobbying contacts with executive branch members since meetings with lobbyists can include more than one designated public office holders. Following our theoretical framework, we distinguished between four main categories of executive personnel. Table 1 describes the nature of each category and the executive staff assigned to each.

Which members of the executive branch are in contact with lobbyists? Table 2 establishes a clearer picture of the executive staff involved in lobbying meetings. This gives us a first look at the extent to which lobbyists talk to ministers, their political-partisan staff, to bureaucrats and senior civil servants. As shown in Table 2, partisan advisors are the most contacted category of executive personnel, followed by public servants, senior public servants, and ministers. In fact, the number of lobbying communications with partisan advisors is more than four times higher than with ministers.

Figure 1 does a yearly comparison of the number of communications lobbyists make with each category of executive personnel. The results in this figure show that the pattern found in Table 2 is a consistent trend. Lobbyists primarily contact partisan advisors and public servants in all years covered in this study. Similarly, ministers are the least contacted in each year, and senior public servants are third. While Figure 1 reveals peaks and troughs in the number of lobbying communications, these variations did not affect the ranking of executive personnel targeted; partisan advisors are always the most lobbied, and ministers are always the least lobbied of the four categories.

Are there meaningful differences in lobbying contacts between administrative and executive personnel in Canada's parliamentary system? We also seek to understand lobbying patterns within the administrative and political corridors of the executive branch staff by examining the nature of meetings and exchanges with lobbyists. We use our data on executive lobbying to probe two specific questions.

First, we want to know if there are different patterns of meetings depending on the category of executive personnel that lobbyists communicate with. To do so, we built an indicator to examine the extent to which partisan (minister and partisan advisors) and nonpartisan (senior and non-senior public servants) meet with lobbyists alone or meet with lobbyists with at least one more representative of the opposing partisan/non-partisan divide. Mixed communications are defined as a meeting involving executive personnel on the partisan side and nonpartisan side simultaneously, whereas non-mixed meetings only involve one side. According to this operationalization all lobbying communication involving only one public office holder are included in the non-mixed meetings category.

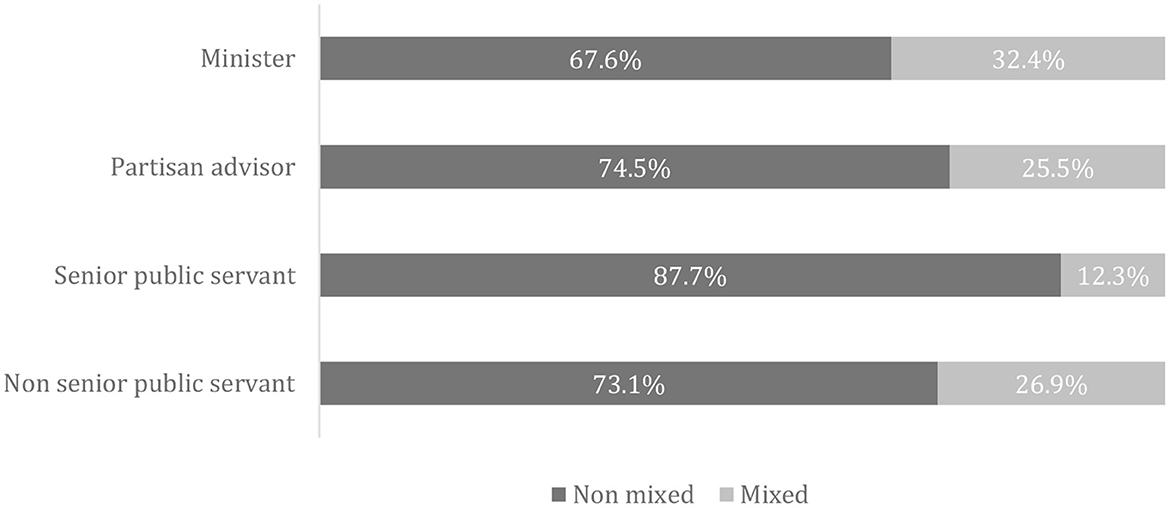

Unsurprisingly, one dominant trend seen in Figure 2 is that non-mixed communications occur more frequently than mixed communications, which can be due to the inclusion of one-on-one communications with lobbyists. Another noteworthy result, however, is the reduced proportion of mixed lobbying communications involving senior public servants. While ministers (32%), partisan advisors (26%) and non-senior public servants (27%) all have at least one fourth of their communications in the mixed category, only slightly more than one-tenth (12%) of communications involving senior public servants are mixed.

Figure 2. Percentage of mixed and non-mixed communications with lobbyists by category of executive personnel.

In other words, senior public servants tend to be alone or with their colleagues from the nonpartisan side of Canada's public administration when meeting with lobbyists. This does not apply to non-senior public servants (27% of meetings are mixed). A much more significant part of lobbying communications with non-senior public servants also involves partisan advisors or ministers. The results also show that ministers are engaging in more mixed lobbying communications than any other category of executive personnel.

One possibility why senior public servants have so many non-mixed meetings with lobbyists is that senior public servants might be interested in technical issues and in-depth details related to policies and decisions at a more advanced (implementation) stage (Bourgault and Dunn, 2014; Jieun and Stuckatz, 2023), and less inclined to take part in discussions related to the political and partisan aspects of political decisions and exchanges with interest group lobbyists. Likewise, the low incidence of non-mixed lobbyist meetings among ministers might reflect the fact that ministers are generally not issue-experts and might need administrative and hands-on technical details to make sense of issues discussed with lobbyists. This is consistent with the preference of ministers to bring along public servants and senior public servants when they meet lobbyists, and with our findings that ministers take part in more mixed lobbying communications than other categories of executive personnel.

Another related factor is that lobbyists and their client organizations may be more interested in meeting personnel that are able to provide them with a specific type of information or commitment regarding the interpretation and implementation of regulatory or legislative dispositions. In Canada's parliamentary institutions, lobbyists have more opportunities to meet ministers outside of their executive roles since they are elected members of the Parliament of Canada and have to fulfill their obligations as seating members of the House of Commons (Savoie, 2019). Hence, lobbyists may be contacting senior public servants because they are more distanced from the legislative process and closer to the implementation phase of policies. Interest group lobbying may be an ongoing back-and-forth dialogue with elite bureaucrats in order to build a mutual understanding of the operationalization and potential consequences of bills under scrutiny in parliamentary committees or during other parliamentary procedures. While these are all hypotheses based on the nature of executive personnel and the legislative process in Canada, they are not mutually exclusive and can coexist as many contributing factors explaining the prevalence of non-mixed meetings with senior public servants.

Do consultant and in-house lobbyists communicate with the same type of executive personnel? Examining the other end of the relationship can also lead to important insights into the dynamic of executive lobbying in Canada. Figure 3 presents the proportion of lobbying communications performed by in-house and consultant lobbyists by type of executive personnel. We distinguish between two categories of in-house lobbying: corporate lobbying and non-profit lobbying. This allows us to add a complementary distinction between the in-house lobbying activities of corporations and non-profit organizations.

Figure 3 shows that consultant lobbying is more prevalent among non-senior public servants (30%) and partisan advisors (38%). Senior public servants (17%) and ministers (19%) do not have as many contacts with consultant lobbyists.

The disparities observed between categories of executive personnel are not as wide in the case of in-house lobbying. Senior public servants (33%) and ministers (30%) obtain the highest proportion of (corporate) in-house lobbying communications. Non-profit lobbyists are responsible for at least half of all lobbying communications with senior public servants (50%) and ministers (51%). In-house lobbying by nonprofit organizations also accounts for the highest proportion of lobbying communications with non-senior public servants (45%) and partisan advisors (39%). Similarly, non-senior public servants and partisan advisors have a lower proportion of in-house (corporate) lobbying than senior civil servants and ministers.

Non-profit lobbying accounts for a higher proportion of executive lobbying, especially lobbying with ministers and senior public servants. A more detailed look at granular information on non-profit lobbying confirm that important trade and industrial associations—The Mining Association of Canada (MAC) and the Canadian Chamber of Commerce, for example—are among the most active lobbies when it comes to meetings with ministers, as well as other national organizations representing environmental interests and public institutions such as universities and municipalities.

At a more global level, it seems that access to executive personnel, and even more precisely, access to top executive decision-makers (i.e. ministers and senior public servants), favor associational lobbying, which is generally characterized by the representation of collective, sectoral and national interests. Conversely, corporate lobbying occurring at the individual/firm level appears to be less common than associational lobbying. Having said this, corporate organizations, just as non-profit organizations, are also working with consultant firms to complement their own in-house lobbying.

A great deal of research has sought to understand the influence and role of lobbyists in contemporary governance. While a number of studies from presidential systems have theorized about, and empirically investigated, different patterns lobbyists have concerning administrative and executive lobbying (McKay, 2011; Boehmke et al., 2013), research from parliamentary countries suggests that lobbying is much simpler: The great deal of power the executive has over the legislative agenda means that lobbyists tend to focus on lobbying executive personnel (Pross, 1986; Montpetit, 2002; Vining et al., 2005; Scheiner et al., 2013; Vesa et al., 2018; Boucher and Cooper, 2021a).

Drawing upon recent work in public administration, public policy, and political science, this article argued that important differences in the skills, motivations, responsibilities and power among different categories of public office holders within the executive as well as differences in the expertise and representativeness among lobbyists, might mean that executive-lobbying relationships within parliamentary countries is not unidimensional. Exploring executive-lobbying relationships with data from Canada's Federal registry of lobbyists, this study found important variation in who is meeting whom. Specifically, our results showed that in-house lobbyists were much more likely to contact senior political (ministers) and administrative personnel (senior public servants) within the executive than are consultant lobbyists, who contact many more partisan advisors and non-senior public servants.

More specifically, this variation in the executive-lobbying relationship does not appear to stem from differences between partisan-political and administrative personnel, but rather is more consistent with a logic of access tied to differences in the political representativeness and expertise that in-house lobbyists possess over consultant lobbyists. Expertise and political representativeness might be more attractive to senior public servants and politicians when using their scarce time to meet lobbyists, than partisan advisors and non-senior public servants.

While this study takes a first important step in theorizing about and empirically investigating variation in executive-lobbying relationships in Westminster parliamentary countries, this study also has some limitations which, if addressed by future studies, will further advance our understanding of lobbying in parliamentary countries. First, while we have theoretical reasons to explain the motivations of varying executive personnel and lobbyists, such motivations were not empirically measured. We acknowledge that there could be alternative reasons that explain our results. For instance, while the great deal of interaction in-house lobbyists have with senior public servants is consistent with these lobbyists providing expertise and possessing political representativeness, our results do not exclude the possibility that this pattern might stem from the fact that that the nature of in-house lobbyists work requires long-term relationships with executive personnel more than consultant lobbyists, and that accordingly, in-house lobbyists seek out more senior administrative personnel. In short, future studies using survey methods to probe the motivations of executive personnel and lobbyists would further advance the findings in this study.

A second limitation is that this paper used data from Canada, a Westminster system with a great deal of centralized executive power and a strong impartial public service. Future studies examining executive-lobbying relationships in other parliamentary countries would allow us to better understand the extent to which the relationships observed in this study are common to other parliamentary countries or are contingent to Canada. For instance, it could be the case that in parliamentary countries where power is more dispersed among members of Cabinet, ministers, as well as their respective senior public servants, are a more lobbied category of executive personnel than that observed among our data. It might also be the case that in parliamentary countries where there is a greater politicization among senior public servants, we see this category of executive personnel have more mixed meetings with lobbyists alongside political executive personnel than what we observed within the present study.

Finally, two additional aspects we did not explore, but that offer a means to further our understanding of variation in executive-lobbying relationships is the type of interest groups lobbyists represent, and the ideology of the governing party. While we explored differences between corporate and non-profit in-house lobbyists, we did not further explore differences in the type of interest groups, such as finance, unions, and religious associations. While some studies have found meaningful variation across interest groups in the intensity of lobbying government in Canada (Boucher, 2015; Graham et al., forthcoming), this has not universally been the case across parliamentary countries (Pedersen et al., 2014). It stands as an open question whether the executive-lobbying patterns found in this study are further modified or not, by considering the type of interest groups, as well as the political ideology of the government.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.lobbyingdemocracy.com/data.html.

CC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^The Office of the Commissioner on Lobbying of Canada defines comparable rank category as governmental employees who: “hold positions which, by any title, have comparable decision-making or advisory responsibilities to Associate Deputy Ministers and Assistant Deputy Ministers; are remunerated at least as much as the minimum salary of an Assistant Deputy Minister; and, report to a DPOH, as do Associate Deputy Ministers and Assistant Deputy Ministers.” See: https://lobbycanada.gc.ca/en/rules/the-lobbying-act/advice-and-interpretation-lobbying-act/interpretation-of-comparable-rank-for-designated-public-offices/. Other categories have been added over time, including the following: Chief of the Defence Staff, Vice Chief of the Defence Staff, Chief of Maritime Staff, Chief of Land Staff (Canadian Forces), Chief of Air Staff (Canadian Forces), Chief of Military Personnel (Canadian Forces), Judge Advocate General (Canadian Forces), Any positions of Senior Advisor to the Privy Council Office to which the office holder is appointed by the Governor in Council Deputy Minister (Intergovernmental Affairs) (Privy Council Office), Comptroller General of Canada, any position to which the office holder is appointed pursuant to paragraph 127.1 (a) or (b) of the Public Service Employment Act, Members of Parliament, Members of the Senate, any staff working in the offices of the Leader of the Opposition in the House of Commons or in the Senate, and appointed pursuant to subsection 128(1) of the Public Service Employment Act.

2. ^For more information, see: Lobbying Act. (R.S.C., 1985, c. 44 (4th Supp.). Art. 5(1) (a), Art. 5(1) (b), Art. 7(1) (a) & 7(1) (b). URL: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/L-12.4/section-7.html?wbdisable=true.

3. ^The following departments and central agencies are included in our study: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), Canadian Heritage (PCH), Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC), Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), Finance Canada (FIN), Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), Global Affairs Canada (GAC), Health Canada (HC), Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED), Justice Canada (JC), National Defence (DND), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Prime Minister's Office (PMO), Privy Council Office (PCO), Public Safety Canada (PS), Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC), Transport Canada (TC), Treasury Board Of Canada Secretariat (TBS), Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC), Women and Gender Equality (WAGE).

Almond, G. A. (1958). Research note: a comparative study of interest groups and the political process. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 52, 270–282. doi: 10.2307/1953045

Armstrong, R. (1985). The Duties and Responsibilities of Civil servants in Relation to Ministers: Note by the Head of the Civil Service. London: CabinetOffice.

Aucoin, P. (2012). New political governance in westminster systems: impartial public administration and management performance at risk. Governance 25, 177–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2012.01569.x

Baumgartner, F. R. J. M, Berry, M., Hojnacki, D. C., Kimball, B. L., and Leech (2009). Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Beyers, J., and Braun, C. (2014). Ties that count: Explaining interest group access to policymakers. J. Public Policy 34, 93–121. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X13000263

Boehmke, F. J., Gailmard, S., and Patty, J. W. (2013). Business as usual: Interest group access and representation across policy-making venues. J. Public Policy 33, 3–33 doi: 10.1017/S0143814X12000207

Bøggild, T. (2015). How politicians' reelection efforts can reduce public trust, electoral support, and policy approval. Polit. Psychol. 37, 901–919 doi: 10.1111/pops.12303

Boucher, M. (2015). Note de recherche. L'effet Westminster: Les cibles et les stratégies de lobbying dans le système parlementaire canadien. Can. J. Pol. Sci. 48, 839–861. doi: 10.1017/S0008423916000019

Boucher, M. (2018). Who you know in the PMO: lobbying the prime minister's office in Canada. Can. Public Admin. 61, 317–340. doi: 10.1111/capa.12294

Boucher, M., and Cooper, C. A. (2019). Consultant lobbyists and public officials: selling policy expertise or personal connections in Canada? Pol. Stud. Rev. 17, 340–359. doi: 10.1177/1478929919847132

Boucher, M., and Cooper, C. A. (2021a). Lobbying and governance in Canada. Can. Public Admin. 64, 682–688. doi: 10.1111/capa.12442

Boucher, M., and Cooper, C. A. (2021b). Lobbying and democratic governance in Canada. Int. Groups Adv. 11, 157–169 doi: 10.1057/s41309-021-00133-0

Bourgault, J., and Dunn, C. (2014). (eds.). Deputy Ministers in Canada: Comparative and Jurisdictional Perspectives. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Bourgault, J., and Van Dorpe, K. (2013). Managerial reforms, public service bargains and top civil servant identity. Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 79, 49–70. doi: 10.1177/0020852312467739

Braun, C. (2013). The driving forces of stability: exploring the nature of long-term bureaucracy–interest group interactions. Adm. Soc. 45, 809–836. doi: 10.1177/0095399712438377

Cooper, C. A. (2017). The rise of court government? Testing the centralisation of power thesis with longitudinal data from Canada. Parliam. Aff. 70, 589–610. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsx003

Cooper, C. A. (2020). At the Pleasure of the Crown: The Politics of Bureaucratic Appointments. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Cooper, C. A. (2021). Politicization of the bureaucracy across and within administrative traditions. Int. J. Public Admin. 44, 564–577. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2020.1739074

Cooper, C. A., and Boucher, M. (2019). Lobbying and uncertainty: lobbying's varying response to different political events. Governance 32, 441–455. doi: 10.1111/gove.12385

Craft, J. (2013). Appointed political staffs and the diversification of policy advisory sources: theory and evidence from Canada. Pol. Soc. 32, 211–223. doi: 10.1016/j.polsoc.2013.07.003

Craft, J. (2015). Conceptualizing the policy work of partisan advisers. Policy Sci. 48, 135–158. doi: 10.1007/s11077-015-9212-2

Craft, J., and Halligan, J. (2017). Assessing 30 years of Westminster policy advisory system experience. Policy Sci. 50, 47–62. doi: 10.1007/s11077-016-9256-y

Dahlström, C., and Lapuente, V. (2017). Organizing Leviathan: Politicians, Bureaucrats, and the Making of Good Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dockendorff, A., and Lodato, S. (2023). When do interest groups lobby legislators in strong presidential systems? Legis. Stud. Q. doi: 10.1111/lsq.12419

Ebinger, F., Veit, S., and Fromm, N. (2019). The partisan–professional dichotomy revisited: politicization and decision-making of senior civil servants. Public Adm. 97, 861–876. doi: 10.1111/padm.12613

Eichbaum, C., and Shaw, R. (2008). Revisiting politicization: political advisers and public servants in Westminster systems. Governance 21, 337–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2008.00403.x

Graham, N., Evans, P., and Chen, D. (forthcoming). Canada's lobbying industry: business and public interest advocacy from Harper to Trudeau. Can. J. Pol. Sci.

Grube, D. C., and Howard, C. (2016). Promiscuously partisan? Public service impartiality and responsiveness in Westminster Systems. Governance 29, 517–533. doi: 10.1111/gove.12224

Helgesson, E. (2023). Paid to lobby but up for debate: role conceptions and client selection of public affairs consultants. J. Commun. Manag. 27, 617–632. doi: 10.1108/JCOM-12-2022-0147

Hood, C., and Lodge, M. (2006). The Politics of Public Service Bargains: Reward, Competency, Loyalty—And Blame. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Jieun, J., and Stuckatz, J. (2023). Mobilization and strategies: comparing trade lobbying in the US and Canada. Comp. Pol. Stud. doi: 10.1177/001041402311930

Jordan, S. V., and Meirowitz, A. (2012). Lobbying and discretion. Econ. Theory. 49, 683–702. doi: 10.1007/s00199-011-0634-6

Kato, J. (1996). Institutions and rationality in politics – three varieties of neo-institutionalists. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 26, 553–582 doi: 10.1017/S0007123400007602

Kerneis, P. (2019). “Lobbyists' appeal and access to decision makers: case study european services forum,” in Lobbying in the European Union, (Berlin: Springer), 105–114.

Kröger, S. (2019). How limited representativeness weakens throughput legitimacy in the EU: the example of interest groups. Public Adm. 97, 770–783. doi: 10.1111/padm.12410

LaPira, T. M., and Thomas, H. F. I. I. I. (2017). Revolving Door Lobbying: Public Service, Private Influence, and the Unequal Representation of Interests. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press.

McKay, A., and Yackee, S. W. (2007). Interest group competition on federal agency rules. Am. Pol. Res. 35, 336–357. doi: 10.1177/1532673X06296571

McKay, A. M. (2011). The decision to lobby bureaucrats. Public Choice 147, 23–138. doi: 10.1007/s11127-010-9607-8

Montpetit, É. (2002). Pour en finir avec le lobbying: Comment les institutions canadiennes influencent l'action des groupes d'intérêts. Politique et Sociétés 21, 91–112. doi: 10.7202/000498ar

Naoi, M., and Krauss, E. (2009). Who lobbies whom? Special interest politics under alternative electoral systems. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 53, 874–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00406.x

Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada. (2022). Communicating With Designated Public Office Holders. Available online at: https://lobbycanada.gc.ca/en/rules/the-lobbying-act/advice-and-interpretation-lobbying-act/communicating-with-designated-public-office-holders/#:~:text=The%20Act%20created%20a%20statutory,as%20well%20as%20those%20occupying (accessed September 10, 2023).

O'Malley, E. (2007). The power of prime ministers: results of an expert survey. Int. Pol. Sci. Rev. 28, 7–27. doi: 10.1177/0192512107070398

Pedersen, H. H., Binderkrantz, A. S., and Christiansen, P. M. (2014). Lobbying across arenas: interest group involvement in the legislative process in Denmark. Legis. Stud. Q. 39, 199–225. doi: 10.1111/lsq.12042

Rommetvedt, H., Thesen, G., Christiansen, P. M., and Norgaard, A. S. (2013). Coping with corporatism in decline and the revival of parliament: interest group lobbyism in Denmark and Norway, 1980-2005. Comp. Polit. Stud. 46, 457–485. doi: 10.1177/0010414012453712

Rosenbloom, D. H. (2001). Whose bureaucracy is this, anyway? Congress' 1946 answer. PS Pol. Sci. Pol. 34, 773–777. doi: 10.1017/S1049096501000658

Saurugger, S. (2008). Interest groups and democracy in the European Union. West Eur. Polit. 31, 1274–1291. doi: 10.1080/01402380802374288

Savoie, D. J. (1999). Governing from the Centre: The Concentration of Power in Canadian Politics. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto.

Savoie, D. J. (2003). Breaking the Bargain: Public Servants, Ministers, and Parliament. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto.

Savoie, D. J. (2019). Democracy in Canada: The Disintegration of Our Institutions. Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen's University Press.

Scheiner, E., Pekkanen, R., Muramatsu, M., and Krauss, E. (2013). When do interest groups contact bureaucrats rather than politicians? Evidence on fire alarms and smoke detectors from Japan. Jap. J. Pol. Sci. 14, 283–304. doi: 10.1017/S146810991300011X

Thomas, P. E. J., and Lewis, J. P. (2019). Executive creep in Canadian provincial legislatures. Can. J. Pol. Sci. 52, 363–383. doi: 10.1017/S0008423918000781

Vesa, J., Kantola, A., and Binderkrantz, A. S. (2018). A stronghold of routine corporatism? The involvement of interest groups in policy making in Finland. Scan. Polit. Stud. 41, 239–262. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.12128

Vining, A. R., Shapiro, D. M., and B. Borges (2005). Building the firm's political (lobbying) strategy. J. Public Affairs 5, 150–175. doi: 10.1002/pa.17

Keywords: lobbying, Westminster, executive branch, partisan advisors, public servants

Citation: Cooper CA and Boucher M (2024) Lobbying the executives: differences in lobbying patterns between elected politicians, partisan advisors and public servants. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1291890. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1291890

Received: 10 September 2023; Accepted: 05 December 2023;

Published: 04 January 2024.

Edited by:

Anthony Nownes, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, United StatesReviewed by:

Nayara Albrecht, Newcastle University, United KingdomCopyright © 2024 Cooper and Boucher. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christopher A. Cooper, Y2hyaXN0b3BoZXIuY29vcGVyQHVvdHRhd2EuY2E=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.