94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 19 December 2023

Sec. Peace and Democracy

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1286577

Studies in maritime diplomacy have treated the development of oil and gas explorations in the South China Sea as taken-for-granted events. On the contrary, this study argues that assessing the maritime diplomatic properties inherent in energy reserve explorations can reveal unique insights, motivations, and significance of maritime diplomatic events. It assesses Malaysia's oil and gas explorations in the Luconia Shoals, informed by the analytical framework of Le Mière's maritime diplomatic properties. Utilizing secondary data from the Asian Maritime Transparency Initiative between 2020 and 2023 related to Malaysia's oil and gas project developments in the Luconia Shoals, this article concludes that the maritime diplomatic events consist of the following characteristics: (1) pre-emptive and sustainment, underlining Malaysia's long-term plan of fulfilling the growing domestic energy demand, (2) explicitness of the messages transmitted to Chinese officials in order to repel any possibilities of adversaries misconstruing Malaysia's actions at sea, and (3) moderate kinetic effect due to the lethal weaponry at the disposal of the hard power assets deployed to handle occurring crisis. Evaluation of Malaysia's maritime diplomatic properties also reveals two worrying conclusions: (1) the existence of reactive events, which can cause disruptions at sea due to the lack of planning related to the actions taken by the Royal Malaysian Navy, and (2) asymmetrical power relations between China and Malaysia, predicted to cause China to continue its power projections at sea and aggravate Malaysian policymakers.

South East Asian states do not have a decisive South China Sea policy. Some claimant and non-claimant states have attempted to show their inflexibility to the evolving crisis by deploying their maritime constabulary forces and navies to showcase effective occupancy over the contested waters (Darwis and Putra, 2022; Putra, 2023a). Others have taken a somewhat flexible stance by downplaying emerging crises and reassuring China that all tensions can be resolved peacefully (Jacques, 2018; Espena and Uy, 2020; Srivastava, 2022).

Nevertheless, China has continued to compel its smaller adversaries in Southeast Asia. In recent years, China's Ten-Dash Line in the South China Sea, continues to be filled with the conduct of crowding the seas through sea-based power projections (Putra, 2022). In an attempt to display China's effective occupancy, it has deployed maritime constabulary forces, Chinese Coast Guards (CCG), and other civilian fleets to normalize its claims (Giang, 2018; Lansing, 2018; RFA, 2023). Besides that, it has also taken the strategy of conducting assertive maneuvers to provoke adversaries at sea (Fang, 2018). This is problematic, considering China's Ten-Dash Line claim is considered illegal under international law, due to its claims being founded by historical fishing routes in the past (Yahuda, 2013; Qi, 2019). The recent arbitration between the Philippines and China also indicates the unlawful nature of China's claims in those seas (Pemmaraju, 2016).

One of the flashpoints of the contestation between China and a smaller adversary is in Malaysia's Luconia Shoals. Malaysia considers those waters part of its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and has been persistent that the seas fall under the sovereign jurisdiction of Malaysia. Consequently, Malaysia has continued undergoing oil and gas explorations in the Luconia Shoals as a reflection of its ownership over the seas. In 2012, Malaysia discovered the Kasawari gas field, followed by oil and gas reserves in the SK 320, SK 306, and SK 410B blocks in late 2022 (AMTI, 2021, 2023a). Throughout this process, China has attempted to aggravate Malaysian policymakers by conducting assertive maneuvers near Malaysia's mainland in the Luconia Shoals. Malaysia has responded passively to these evolving events, ensuring that the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN) and the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA) do not react coercively to those provocations.

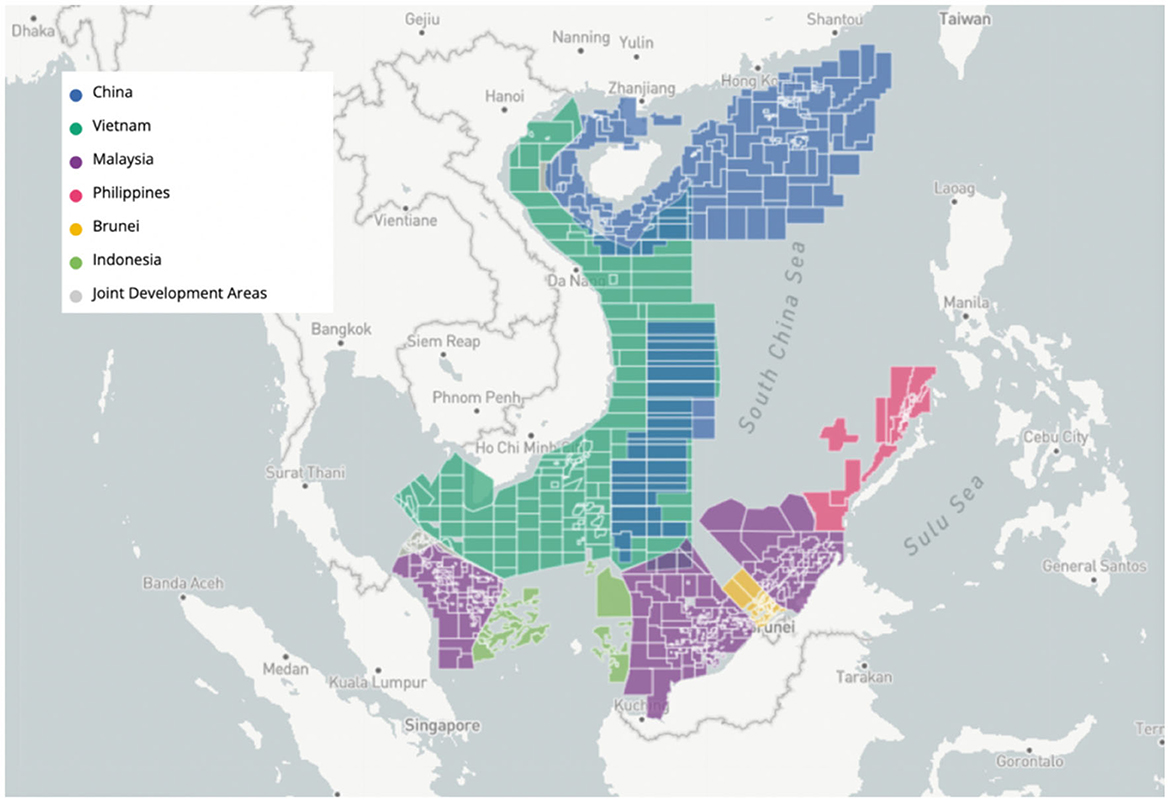

Existing studies have not explored instances of oil and gas explorations as a maritime diplomatic event in the South China Seas, especially among secondary claimant states. Secondary states indicate second-ranked states based on structuralist-inspired rankings in international relations (material capabilities and prospect of agency in regional affairs) (Zha, 2022). For Southeast Asian states, consultation to the Lowy Institute's power rankings reveal that those categorized as claimant states include the Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, and Malaysia (LI, 2023). Thus, this lack of interpretation to the oil and gas explorations in the South China Sea is problematic, as secondary claimant and non-claimant states of the South China Sea dispute have resorted to exploring and developing oil and gas reserves at sea (AMTI, 2023a). Indonesia, for example, is taking measures to develop its Tuna gas field located in the Natuna Waters (Emont, 2023). Vietnam's projects in the Vanguard Bank and Malaysia's oil and gas explorations in the Luconia Shoals also show that a separate study must be made to understand better what these actions can reveal to the overall South China Sea strategy adopted by Southeast Asian states. A map of the South China Sea energy exploration and development can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Energy exploration and development in the South China Sea. Source: Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI, 2023d).

This study treats the development of Malaysia's oil and gas explorations in the Luconia Shoals as unique maritime events, consisting of diplomatic events that could reveal motives, trajectories, and the importance of the South China Sea for secondary states. They include how Malaysia has shown its persistence to continue explorations despite China's growing assertiveness at sea, utilization of hard power assets to safeguard oil and gas projects, and how Malaysia responds to CCGs operating close to Malaysia's mainland. As shown by Chang and past studies in international relations, the utilization of hard power as a form of sea power indicates a state's choice of utilizing military hardware via the sea (Davidson, 2008; Chang, 2022). This can have a vast number of reasons, but primarily as a means to aggravate and compel adversaries to following a certain resolve.

This study argues that assessing the maritime diplomatic properties of those events can provide insights into how Malaysian policymakers aim to manage the South China Sea tensions. Nevertheless, the first insight attained is the puzzling policies taken by Malaysia in the South China Sea, as Malaysia displays consistency in developing policies in contrast to the likings of Chinese officials. The empirical puzzle raised in this article is as follows: Why has Malaysia decided to intensify its oil and gas explorations in the contested waters of the South China Sea? And how does this connect to Malaysia's overall maritime diplomatic strategy vis-à-vis tensions at sea? The South China Sea is full of complexities due to the divergent interests held among claimant and non-claimant states of the contested waters. This article argues that by understanding the maritime diplomatic properties of Malaysia in relation to its recent moves to intensify its oil and gas explorations, we can better grasp how Malaysia perceives the importance of the seas to its nation and what it plans to achieve through the utilization of its military assets at sea. Despite Malaysia's consistency in adopting a downplaying posture over its tensions with China in the South China Sea, continued oil and gas explorations represent Malaysia's unique intent from a maritime diplomatic perspective.

Discourses on maritime diplomacy are slowly gaining traction as great power politics at sea resurfaces in contemporary politics. This literature review will outline the importance of international relations at sea and where this article is situated in the discourse of maritime diplomacy. In doing so, it will first assess the literature on maritime diplomacy, continued by an evaluation of studies on Malaysia's contemporary policies at sea.

The management of international relations at sea is better known as maritime diplomacy. As introduced in the previous section, this article utilizes the analytical framework of Le' Mière's maritime diplomatic properties that he introduced in his 2014 book, “Maritime Diplomacy in the 21st Century: Drivers and Challenges.” Nevertheless, Le Mière's work is a continuation of past scholars' assessment of the importance of the sea in contemporary international politics. Earlier studies can be traced as far back as the 19th century, with Mahan (1898) works emphasizing how the sea can advance one's national interests. Following the development of naval warfare during the World Wars, Cable (1989, 1994) “Gunboat Diplomacy” attracted scholars to identify how diplomacy can also take the form of naval ships conducting certain maneuvers to achieve a pre-determined diplomatic goal. Consequently, most of the following studies include an evaluation of the strategic utility of military hard power assets (navies) and how it is utilized by state actors (Alderwick and Giegerich, 2010; Percy, 2016; Till, 2018).

It was Le Mière's conception of maritime diplomacy that studies started to perceive international sea relations as not confined to military assets. He argued that maritime diplomacy can be undertaken by government and non-government agencies, as well as by civilian and military agencies (Le Mière, 2011). Therefore, he argued that understanding maritime diplomacy can also include an assessment of stakeholders besides navies. Furthermore, Le Mière also argued that instances of maritime diplomacy can be assessed by evaluating its maritime diplomatic properties. This helps reveal the motives and significance of events and better understand maritime diplomatic instances (Le Mière, 2014).

Regarding Malaysia's maritime diplomacy, the discourses have not been conclusive as to what drives and motivates Malaysia's policies at sea. Most discussions have connected Malaysia's South China Sea policy to its overall alignment strategies. Studies made by Kuik (2008), for example, have long argued the presence of approaches signaling defiance and deference vis-à-vis China in the South China Sea (Lai and Kuik, 2020). Qistina also argues that Malaysia's maritime policies could not be confined to events at sea, as she argues that structural factors have determined Malaysia's contemporary maritime policies (Noor and Qistina, 2017). A deeper inquiry into Malaysia's maritime policies has suggested that Malaysia, as a consequence of trade dependency and power asymmetry, opted to take a flexible stance that accommodates the needs of Chinese policymakers (Storey, 2020; Syailendra, 2022). As mentioned earlier, whether Malaysia is adopting a decisive, strict, or accommodative stance vis-à-vis China in the South China Sea is still unclear. Several of the literature has also shown that Malaysia is currently taking an assertive turn to respond to China's aggressive maneuvers at sea due to the dominant deployment of navies to respond to crises (Noor, 2016; Ahmad and Sani, 2017; Wey, 2017).

Existing studies on Malaysia's maritime diplomacy vis-à-vis China are still in the gray. As a claimant state to the South China Sea, Malaysia's concern is in the James and Luconia Shoals. Despite this, as Malaysia continues to downplay instances of crisis, less is known about how Malaysian policymakers perceive the importance of the disputed waters. Furthermore, with the exploration and development of oil and gas in the Luconia Shoals in the past decade, existing studies have treated these developments as taken-for-granted events without paying considerable attention to what insights can be retrieved by investigating these events. On the contrary, this article will provide novel discussions on what the maritime diplomacy literature can elucidate concerning Malaysia's perseverance in developing its oil and gas projects in the South China Sea. The following sections will explain how the maritime diplomatic properties are visualized in the article, the contemporary Malaysian posture in the South China Sea, and an assessment of its maritime diplomatic properties.

This study assesses Malaysia's maritime diplomatic strategies in the South China Sea. Specifically, it inquires why Malaysia has decided to intensify its oil and gas explorations within its EEZ and what this means for its overall South China Sea strategy. In doing so, this qualitative research employs secondary data attained from the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) between 2020 and 2023. It focuses on several critical instances of Malaysia's oil and gas explorations and confrontations faced by Chinese and Malaysian officials at sea. This study provides an alternative interpretation to understanding Malaysia's South China policies, informed by Le Mière's maritime diplomatic framework of maritime diplomatic properties and categories to assess maritime diplomatic events, predict policymakers' intentions, and estimate future possibilities (Le Mière, 2014). The five categories and properties of maritime diplomacy are divided into the following.

Determining the kinetic effect of maritime diplomatic events focuses on the extent of active forces used in a given case. Instances considered kinetic are the utilization of active forces to achieve particular pre-defined aims. Meanwhile, it would be non-kinetic in cases where the military is not deployed for coercive purposes. The use of hard power assets can thus be assessed based on what action it takes in the face of certain events. In determining the level of a case's kinetic effect, it considers to what extent the weaponry is used to threaten or attack adversaries, with cases considered non-kinetic if they fall under peacebuilding operations. This category helps decipher maritime diplomacy instances by seeing what hard power assets are utilized and what states do with them. It further helps to predict the likelihood of escalation in a given case.

Understanding the message requires an assessment of the medium and message that transpires in a case. The level of a message's explicitness is determined firstly by the message itself, whether an actor gives clear communications in regard to the motives of an action. Thus, this category can range from explicit to non-explicit, with the latter concluded in cases where actors decide not to provide explanations of their intent. Le Mière also explains that besides the message, the medium can also act as the message itself, transcending the importance it has compared to the message communicated. He further contends that “the diplomatic statements that surround a particular deployment can be just misleading noise, but the presence of an aircraft carrier or the test firing of a ballistic missile defense system is indicative of the changes in international relations” (Le Mière, 2014, p. 54). In assessing the explicitness of messages, an explicit message leaves less room for misinterpretations, while unspoken messages allow for possible misunderstandings.

The category of pre-emption inquires into the level of sustainment of an action undergone by a state. It can be divided into two possibilities: pre-emptive or reactive maritime diplomacy. Pre-emptive is a carefully calculated and sustained policy planned well-ahead to achieve specific goals. Meanwhile, reactive is usually the case when states are responding to a sudden crisis at sea, leading to more escalatory possibilities due to the unplanned actions taken. The level of sustainment allows a better deciphering of a state's level of commitment toward a certain diplomatic goal.

Assessing the balance of power involves an evaluation of power differences between the two stakeholders involved in a given maritime diplomatic case. It helps to understand the motivations and possible actions that may follow. In asymmetrical cases, where one actor holds significantly greater power than the other, it is unlikely that cases would escalate due to the inability of a weaker state to respond to threats transcending a given maritime diplomatic event. Meanwhile, suppose a case falls under the symmetry category. In that case, the maritime diplomatic event is expected to be prolonged due to the similarities of power held between the two states.

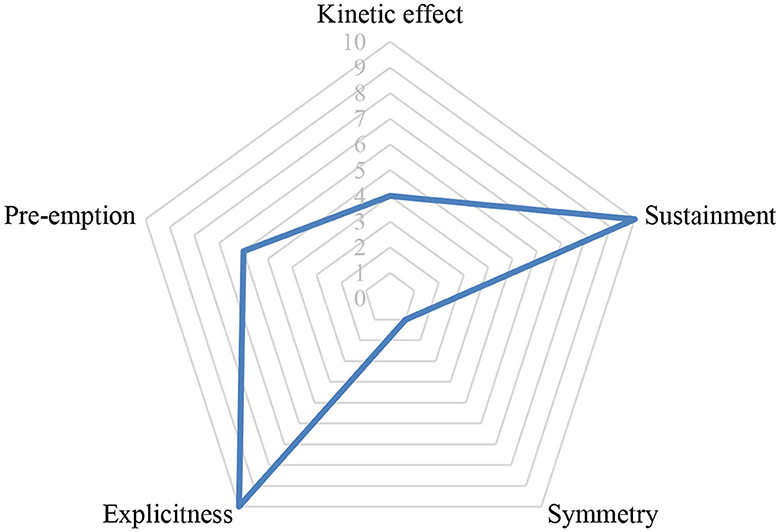

In categorizing the maritime diplomatic strategies for Malaysia's oil and gas explorations, this article employs a radar chart to display the extent of the events as kinetic, symmetrical, explicit, pre-emptive, and sustained. This article concludes the case as kinetic if military forces are utilized for compelling purposes; symmetry if no significant power imbalances exist between the two actors; Malaysia clearly expresses explicitness of the message of intent with consistent actions taken at sea; pre-emptive if actions taken are displays of pre-determined policies; and sustained if Malaysia has consistently taken a route of action in a prolonged period of time.

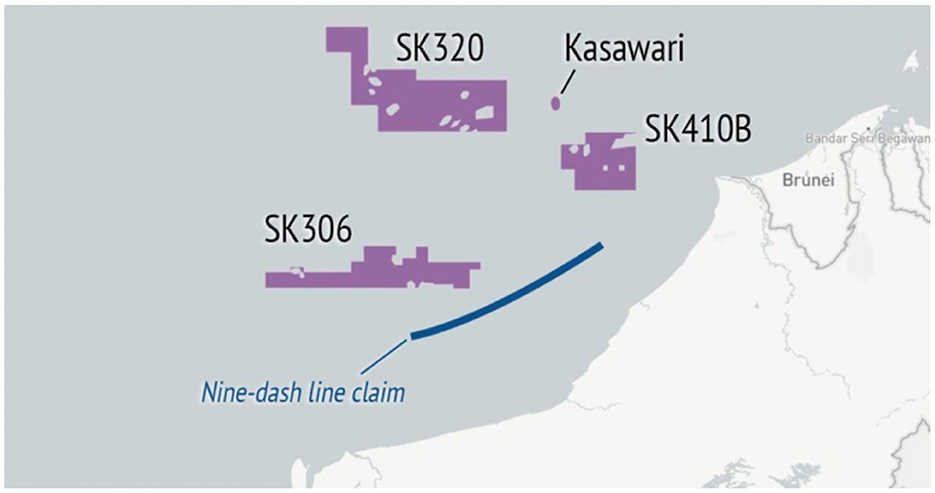

The cases taken include areas of Malaysian oil and gas discoveries and developments since 2020. This consists of the continued exploratory drillings off Sarawak found in 2022 (SK 320, SK 306, and SK 410B) and the Kasawari gas field currently in the production phase (see Figure 2). It is also important to note that the CCG has actively been in operation in areas of close proximity to those mentioned oil and gas exploration sites, which further solidifies the empirical puzzle raised in this article.

Figure 2. Location of Malaysia's oil and gas projects offshore Sarawak between 2020 and 2023. Source: Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI, 2023a).

Tensions continue to flare between Malaysia and China over Malaysia's continental shelf. Both states hold the importance of the James Shoal and Luconia Shoal for their respective sovereignty. Consequently, we have witnessed a series of power projections taking place in the contested waters of the South China Sea. A case of crowding the seas continues to occur as China and Malaysia accelerate their attempt to solidify claims through the placement of the CCG, RMN, and the MMEA, which have sometimes confronted one another (AF, 2023; Chew, 2023).

China's tensions with Southeast Asian states through the use of its maritime constabulary forces is not a new occurrence. For decades, China has attempted to use its civilian fleets to compel the smaller adversaries it faces in the South China Sea (AMTI, 2023b; Masih, 2023; Putra, 2023b). China's coastguards, for example, continue to undermine Southeast Asian sovereignty by intentionally conducting aggressive maneuvers around its claimed Ten-Dash Line (Chang, 2018; Oshige, 2023; Yusof and David, 2023). This has prompted a significant dilemma among Southeast Asian policymakers. Acting decisive vis-à-vis those acts of assertiveness may lead to unforeseeable impacts on their bilateral ties with the Asian giant. Still, a deliberate ignorance of China's maneuvers at sea may also lead China to finalize its claims over its sovereign jurisdiction. With the dilemma faced growing more profound among these secondary states, Malaysia is not excluded from this.

Unlike other claimant states in the South China Sea, Malaysia is considered to be more flexible over its claims. Nevertheless, this is not to say that China is softer with Malaysia in the South China Sea. As reported in past studies such as from Yusof and David (2023), the number of Chinese intrusions into Malaysian waters accumulated 89 times between 2016 and 2019. Chinese military and civilian vessels continue to populate China's claimed Nine Dash Line, including the Southernmost part of the South China Sea, the Luconia Shoals.

As presented in the introduction of this article, why Malaysia adopts a downplaying posture vis-à-vis China's claims against Malaysia's EEZ is puzzling. Sea territories between the two states clearly overlap and cause minor but consistent tensions at sea. However, Malaysia is not adopting the route taken by its ASEAN counterparts, such as the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Since the Arbitration, the Philippines has consistently adopted a decisive South China Sea policy to ensure no further intrusions within its EEZ boundaries (Mangosing, 2019; Basawantara, 2020). Since the 2014 Hai Yang Shu You 981 standoff, Vietnam has also been strict with rhetoric discussing its sea-based sovereignty (Blazevic, 2012; Reuters, 2023b). Similarly, Indonesia, despite being a non-claimant state, has consistently shown its decisiveness through the development of its maritime constabulary forces to match China's contemporary strategies at sea (Pattiradjawane and Soebagjo, 2015; Meyer et al., 2019).

Despite so, similarities of policies among Southeast Asian states can only be identified through their actions in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Claimant states of ASEAN have consistently voiced the importance of non-coercive resolve to the disputes. This is marked by the continues efforts to finalize the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea. Nevertheless, although this indicates a similarity to the national interests of maintaining law and order at sea, this does not indicate an intention to form official alliances vis-à-vis China's claims in the South China Sea.

Tensions have risen for Southeast Asian states vis-à-vis the South China Sea conflict. This is in part due to the involvement of non-claimant states, including the US. In past years, the US's pivot to Asia has led to the re-activeness of the US in the region, mostly through the re-building of relations with Southeast Asian states, and the revival of official strategic partnerships. Consequently, the US presence in Southeast Asia has only led to the escalation of tensions, as China continues to feel aggravated with the US open and free Indo-Pacific operations through the deployment of the US warships in open seas surrounding the South China Sea. These developments prove costly for Southeast Asian states, which have led them to take discreet and diverse maritime diplomatic strategies in response to the great power contestations in the region.

Malaysia for example, does not share a similar maritime diplomatic strategy with its Southeast Asian neighbors. As stated through Malaysia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, it has recalled the importance of Malaysia's sovereignty based on its 1979 map and continued to downplay instances of crisis at sea (MOFAM, 2023). It has continued to re-emphasize Malaysia's openness to negotiations and strengthen the point that no tensions cannot be resolved peacefully (Kreuzer, 2016; RFA, 2021; Bing, 2022). This particular posture is especially evident during Najib Razak's premiership in 2009–2018. Academics such as Storey (2020) concluded that during this time, Malaysia saw great convergence between Malaysia's future projects and China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Furthermore, in a recent note verbale, Malaysia stressed that no disputes exist between Malaysia and China (Syailendra, 2022). But the puzzling development has been Malaysia's recent intensification of oil and gas development in the South China Sea, which aggravates Chinese policymakers.

One of Malaysia's primary oil and gas development centers is the Kasawari gas development project in SK 316 block (SK indicating an area measured by Malaysia in the Kasawari gas development project). Located in the Luconia Shoals, the Kasawari is known to be one of Malaysia's most important gas and oil development sites developed by Petronas, the state-owned gas and oil company. The Kasawari consists of natural gas, crude oil, and condensate, with its production predicted to occur in 2023 (AMTI, 2021). Surprisingly, it has also been Malaysia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs that voiced the importance of those recoverable reserves to secure Malaysia's future energy needs (Chew, 2022).

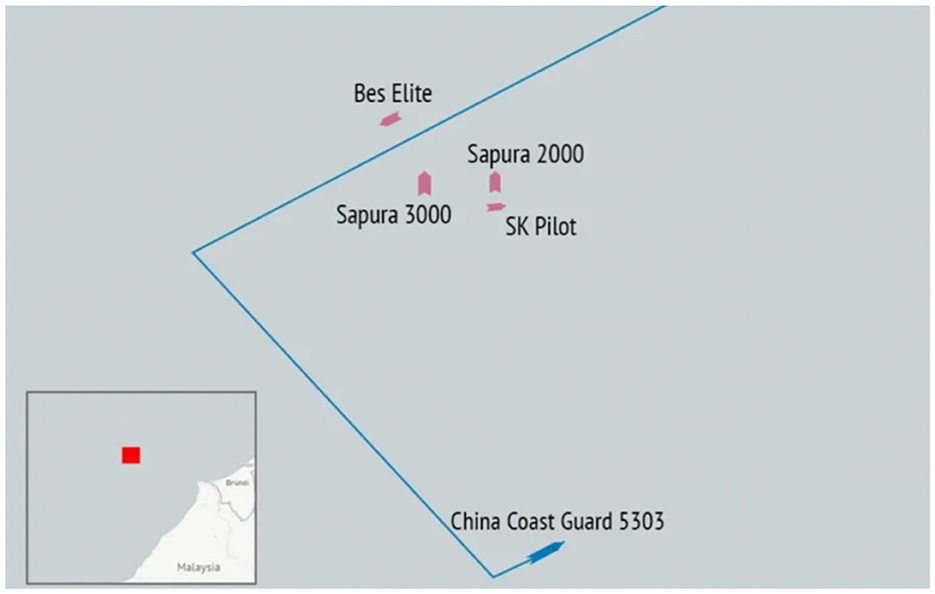

Unsurprisingly, since it was discovered in 2012, the surrounding waters of the Kasawari gas development project have been one of the primary target areas for CCGs, with Malaysian fleets commonly being provoked due to the close proximity of its operations (AMTI, 2023c). Chinese fleets started to crowd the seas at the Luconia Shoals. This was done through China's CCGs, anchoring its vessels in the shoals that are close to Malaysia's land (Srivastava, 2022). China's concern over Malaysia's oil and gas developments intensified in the following years. As reported by AMTI in 2021, CCG 5303 has engaged in assertive maneuvers at sea by sailing in close proximity to disrupt oil and gas development-related vessels in the Luconia Shoals (see Figure 3). There is a strong unease among Beijing policymakers over Malaysia's development of its oil and gas explorations. In Anwar's trip to Beijing, Chinese officials made it clear of such concerns (AF, 2023).

Figure 3. CCG 5303 in close proximity to the Kasawari oil and gas project vessels. Source: Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI, 2021).

Following the developments of the Kasawari oil and gas project, more oil and gas reserves in the Luconia Shoals have been discovered. In late 2022, gas and hydrocarbon reserves were found in the SK 320, SK 306, and SK 410B blocks (AMTI, 2023a). It seems Malaysia perceives the Luconia Shoals with great importance, as Malaysia's years of exploratory drilling have started to show its reward. What is puzzling about these cases of explorations is that China has made it clear rhetorically and through the deployment of its vessels that the shoals fall under the jurisdiction of China. And despite Malaysia's long-held stance of downplaying the South China Sea conflict, it has politely rejected those claims and continued its explorations.

It is further argued in this section that Malaysia's responses to China's assertiveness at sea have been relatively flexible and indecisive. The only case that could be used against this assumption is Malaysia's deployment of its RMN in responding to intrusions at sea. However, the Luconia Shoals are located in such close proximity to Malaysia's mainland. It is the natural response of Malaysian officials to deploy its navies if intrusions take place in such particular proximities. As seen by Malaysia's response to CCG 5303 in 2021 and CCG 5901, which in both cases were responded to by the Malaysian Navy. An instance of coerciveness could be concluded if these vessels were used to threaten Chinese officials or intentionally rammed to compel adversaries (as evident in the case of Indonesia and Vietnam). In contrast, Malaysia's navies were not utilized for such purposes.

As reported by Dolbow (2018) and Parameswaran (2019), Malaysia's MMEA does not have the same capacity as other Southeast Asian maritime constabulary forces. A well-developed maritime constabulary force has the capacity to perform patrol and pursuit functions, which is a natural mandate given by Southeast Asian states. In contrast, Malaysia deployed navies due to the lack of attention it has granted to developing its civilian forces at sea.

To conclude, Malaysia's South China Sea stance seems to be a mixture of defiance and deference toward China. On one side, Malaysia has shown that it is accommodative and open to negotiation with China. It does not display a coercive posture like its other ASEAN colleagues and has acted more for defensive purposes. This strategy is vital for Malaysia in order to deter aggravating China over the disputed waters, but at the same time maintain a decisive posture toward its claims. Nevertheless, Malaysia's recent development of its oil and gas projects shows a vital element of Malaysia's decisiveness in the South China Sea. Despite constant warnings and on-site intrusions, Malaysia is currently risking its good relations with China by going against the wishes of Chinese policymakers. As Anwar expressed in his visit to Beijing in April 2023, he stressed Malaysia is only continuing its oil and gas projects within its defined sovereign borders (AF, 2023). This is risky and goes against Malaysia's traditional South China Sea policy of downplaying the crisis. The big question remains: Why do states develop oil and gas projects in contested waters? This can be deciphered by assessing maritime diplomatic events and categorizing their maritime diplomatic properties.

Southeast Asian states' exploration and development of oil and gas in the South China Sea remains understudied. This is problematic, as the number of CCG patrols within the Ten-Dash Line continues to increase in areas in which Southeast Asian states have decided to undergo exploration and development of oil and gas projects. Indonesia's plan to develop the Tuna gas field in the Natuna Waters, Vietnam's projects in the Vanguard Bank, and the promising oil and gas reserves in Malaysia's Luconia Shoals have all attracted considerable assertiveness of CCG vessels.

Despite this growing trend of oil and gas developments in the South China Sea, no scholarly work has currently attempted to assess what this development means, the intentions of states, and the future trajectories. Therefore, such instances have been treated as taken-for-granted events, despite the promising possibility of such events to showcase the true intent of states and what it can reveal about policymakers' perceptions toward the South China Sea. As seen in Table 1, such developments in the South China Sea have attracted increased CCG patrols attempting to safeguard its claimed Ten-Dash Line. In 2022 alone, these CCG patrols occurred almost daily (AMTI, 2023b). This action-reaction dynamic is worthy of investigation, as oil and gas developments have attracted significant discontent among Chinese policymakers.

In an attempt to fill in the gap in the literature, this article proceeds with an assessment of the maritime diplomatic properties of Malaysia's oil and gas developments in the South China Sea. A better understanding of Malaysia's contemporary South China Sea policy can be obtained by assessing specific events taking place due to Malaysia's drilling projects in the Luconia Shoals. Specifically, it does not focus on a single event. Besides assessing the rhetoric accompanying Malaysia's intensified attempts to extract oil and gas in the Kasawari field and explore new energy sources, it will also include how Malaysia responds to instances of CCG intrusions through its civilian and military fleets at sea. This consists of the RMN, MMEA, and all fleets related to the oil and gas explorations. The assessment includes translating such events into five separate categories: kinetic effect, explicitness, pre-emption, symmetry, and sustainment. Figure 4 concludes the maritime properties found in the case taken for this article.

Figure 4. Maritime diplomatic properties of Malaysia's oil and gas development-related policies. Source: Compiled by the author.

The kinetic effect of Malaysia's oil and gas developments in the Luconia Shoals is moderate. This is due to the RMN's involvement in responding to the CCG intrusions into Malaysian waters rather than deploying civilian fleets such as the MMEA. Le Mière (2014) argues in his seminal work that a particular event is concluded consisting of kinetic effect if active forces are utilized in international relations at sea. Nevertheless, an assessment of how states utilize those hard power assets in achieving their goals is needed. With the tactical flexibility of state-owned fleets in Malaysia, different actions conducted by the navies would result in a divergent kinetic level. What would constitute an extreme case of kinetic effect would include assertive maneuvers, targeted violence, and warning shots. If any weaponry is used during an instance of a maritime diplomatic event, it must also consider the level of destructiveness.

In the case of Malaysia, the utilization of navies is not strategically decided. As Dolbow (2018) and Parameswaran (2019) suggest, despite the growing trend of Southeast Asian states developing their maritime constabulary forces (including coast guards), the MMEA is not among those. As much as Malaysia wanted to make effective use of its MMEA to make pursuits at sea, it did not have the strategic capacity to keep up with the assertive maneuvers of the CCG. Therefore, although the Malaysian Navy is primarily tasked with safeguarding Malaysia's sovereignty at sea, it often takes on secondary roles to compensate for the lack of capacities inherent in Malaysia's constabulary forces. Furthermore, the CCG intrusions listed in Table 1 took place in the Luconia Shoals, which is close to Malaysia's mainland, therefore making it feasible for the RMN to take an active role in suppressing China's assertiveness at sea. If Malaysian officials intentionally deployed their navies in all instances, followed by coercive weaponry to compel Chinese fleets, it would no longer be considered moderate but an extensive kinetic effect. The coincidental nature of the RMN involvement between 2020 and 2023 shows that Malaysia is not intended to militarize the tensions it faces with China.

Malaysia's oil and gas developments in the Luconia Sholas fulfill the maritime diplomatic property of sustenance. Unlike the temporality of abbreviated occurrences, a sustained maritime diplomatic strategy exists through a longer time horizon. Understanding the level of sustainment helps to determine the degree of importance of a particular event. As the maritime diplomacy literature argues, if a policy is sustained, chances are, there exists a strong commitment and determination within a state's policymakers to achieve the pre-determined goal (Le Mière, 2014).

As seen in Figure 4, out of all of the visualized properties, maritime diplomatic events related to Malaysia's oil and gas developments indicate a consistent act of sustainment. The early developments started in 2012 when abundant oil and gas reserves were found in the Kasawari field. With the rhetoric evolving within Malaysia to develop those resources, Chinese officials began to display their discontent by projecting power around the fields. Nevertheless, Malaysia continued to progress in its development, following the CCG anchoring of vessels in Luconia Shoals in June 2015 (Srivastava, 2022). Furthermore, a vital element of sustainment is identified with how Malaysia's Foreign Ministry downplays any instances of crisis faced by China at sea (NBR, 2023). In order to progress Malaysia's constructions at the Luconia Shoals, the ministry is determined to maintain its long-held stance not to aggravate China and continue being open to negotiation (MOFAM, 2023). This convergence of interests held between the different ministries and bodies within Malaysia reflects a determined policy to continue explorations in the Luconia Shoals despite facing China's growing assertiveness at sea since 2014 (Bing, 2022). As a form of Malaysia's commitment to developing oil and gas developments in the South China Sea, Malaysia is willing to categorize intrusions made by Chinese officials as not a concern that is worthy of being responded to through coercive means (Reuters, 2023a).

Due to Malaysia's resolve and commitment to developing the newly found oil and gas reserves in the Luconia Shoals, it is clear that Malaysia is acting in a pre-emptive manner. Le Mière (2014) asserts that the common maritime diplomatic event at sea is usually pre-emptive. This means that these actions are carefully calculated and planned. It is contrary to reactive events, in which actions taken usually are impromptu and can lead to escalatory conditions due to the situation being unpredictable. Pre-emptive maritime events are less dangerous, as adversaries can somewhat predict the outcome of a given instance due to an action being maintained for an extended period of time. It also means that uncertainties are less likely due to the familiar nature of a given situation for the adversary.

In the case of Malaysia, it is challenging to categorize whether it falls under the category of pre-emptive or reactive. As many small maritime diplomatic events are considered, it became clear that Malaysia, for this category, is situated at a moderate to high pre-emptive level. Its maritime diplomatic strategies are still strongly connected to pre-emptive elements, especially with the trajectory of its oil and gas development in Luconia Shoals in the past decade. The patterns are consistent, starting from the discovery of the Kasawari oil and gas field, its initial investment, and its commercial production that begins in 2023. All operations at sea are reflections of the steady development of its facilities.

However, the numerous events involving the RMN and the CCG are primarily reactive. In the cases of CCG 5403 (July 2021) and CCG 5901 (January 2023), assertive maneuvers conducted by the CCG were responded to by the RMN (AMTI, 2023c). This encounter could easily be responded to in an escalatory fashion, as the crisis does not provide enough time to calculate the costs and risks of taking certain actions. Nevertheless, as Malaysia has displayed in the past several years, by deploying the navies in circumstances where the crises are in close proximity to Malaysia's mainland, this study suggests that Malaysia's maritime diplomatic properties are moderate to high and pre-emptive.

The fourth maritime property questions the extent of the maritime diplomatic event explicit in its messages, implicit or muteness. For this category, it is concluded that the explicitness of the messages and medium explaining maritime diplomatic events are clear. Furthermore, due to the explicitness of the message given by Malaysian authorities, it is hardly likely to translate events at sea differently than oil and gas development-related. Since the discovery of the Kasawari oil and gas field in 2012 and the new discoveries made in other parts of the Luconia Shoals in early 2023, it is clear that any operations made at sea within Malaysia's EEZ are to undergo drilling or development operations. This is also supported by a consistent and rational number of vessels linked to the conduct of drilling operations, allowing possible misinterpretations of actions at sea to a minimum.

Messages sent by Malaysia will not be misconstrued by Beijing, considering the consistency of messages transmitted among policymakers in Malaysia. Malaysia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs has been aligned with the actions of the Malaysian government to express Malaysia's intent to undergo oil and gas development within the Luconia Shoals. Therefore, the vast number of non-military vessels is explained not as a form of power projection at sea (as in the case of China in the past two decades) but as part of the civilian operation to drill energy reserves at sea. For example, the crisis involving the CCG 5901 vessel and Malaysia's Sapura 2000 and 3000 dredgers could not be misinterpreted as their presence is consistent with the pre-determined timeline issued by Malaysian officials (AMTI, 2023c). Anwar's recent visit to Beijing also made it clear that Malaysia is advancing its long-planned oil and gas development project in the Kasawari field, reassuring Chinese officials that all operations conducted are within Malaysia's sovereign jurisdiction (Chew, 2023).

The last category assessed is the power symmetry among adversaries. This category scored the lowest out of Malaysia's maritime properties related to oil and gas development. Malaysia's encounter with China is asymmetrical, as a considerably stronger power (China) is aggressively displaying its discontent toward the actions taken by a lesser power (Malaysia). This would be concluded in maritime diplomacy as an instance of coercive maritime diplomacy, as an actor is compelled by a significant other (Le Mière, 2014). Therefore, contrary to being symmetrical, the power relations of Malaysia vis-à-vis China in the South China Sea are asymmetrical.

The consequences are significant. As the literature predicts, asymmetrical power relations lead to a prolonging of one actor compelling the other. Consequently, the stability of the relations can easily be shaken due to the capacity of China to aggravate Malaysia without considerable retaliation. China's persistence with its CCG intrusions and other assertive maneuvers at sea will continue until power relations between Malaysia and China can reach a moderate level of symmetry. Only then will China hesitate to assert its dominance due to the fear of being retaliated by Malaysia. Despite the involvement of navies in certain crises, Malaysia still shows relative weakness vis-à-vis China. Its hesitancy to militarize the conflict also indicates China has the upper hand in controlling the pace of tensions at sea.

In conclusion, Malaysia's oil and gas development represents Malaysia's maritime diplomatic policy of sustainment, pre-emption, and explicitness. Maritime diplomatic events that occurred as a consequence of Malaysia's plan to secure energy reserves in the Luconia Shoals are non-militaristic in nature and have become favorable conduct due to the prospects of lucrative oil and gas drillings at sea, without having to risk abandoning Malaysia's long-held stance in the South China Sea. Malaysia faces CCG intrusions almost daily and has come to normalize those actions in order not to aggravate Chinese policymakers. In contrast, it has learned to continue its projects in the Kasawari gas field and normalize the Chinese presence.

The only concerns that could be extracted from analyzing Malaysia's maritime diplomatic properties are the reactive nature of incidents and the asymmetrical power relations of Malaysia vis-à-vis China in the South China Sea. As seen in Table 1, the number of CCG intrusions increased in 2022, and this is due to Malaysia's intensified attempt to develop the oil and gas fields in the Luconia Shoals. As the RMN is mainly involved in safeguarding Malaysian vessels located close to Malaysia's mainland, maritime diplomatic literature warns of the possibility of escalating tensions due to the lethal weaponry at the disposal of navies. Furthermore, the power asymmetry between Malaysia and China is also predicted to generate continued assertiveness of China's maneuvers at sea, as Malaysia attempts not to aggravate the Asian giant with its South China Sea policy.

In making sense of these maritime diplomatic properties, a quick glance into the Malaysia-China bilateral relations provides interesting insights. Malaysia's South China Sea policy has been puzzling in the past two decades. China continues to intrude into Malaysian waters and claim many parts of its EEZ. Contrary to its ASEAN counterparts, Malaysia's responses have been moderate. It is worth noting that the importance of China for Malaysia has grown considerably in the past years. As reported, the two-way trade between them accumulates to USD 203.6 billion, which makes China Malaysia's most important trading partner (Reuters, 2023a). Past and existing Malaysian policymakers also perceive a convergence in interests in the infrastructure and investment sectors, as the BRI is perceived in Kuala Lumpur as able to provide the needs of Malaysia's ambitious infrastructural plans in the near future (Noor and Qistina, 2017; RFA, 2021).

The South China Sea disputes continue to become a contentious issue for the secondary states of Southeast Asia. When tensions flare at sea, claimant states such as the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia must respond decisively without aggravating their leading trading partner. As seen in the current status quo, China has treated the waters within its Ten-Dash Line as its own. It continues to project power at sea through its maritime constabulary forces and coast guards in order to crowd the seas and showcase effective occupancy.

Among the areas where China maintains its presence at sea is the Luconia Shoals. China considers these shoals as the Southernmost part of its Ten-Dash Line. In recent years, China has intensified its power projection in the Luconia Shoals in response to Malaysia's recent discoveries and continued development of oil and gas explorations. Since 2012, the Kasawari gas field has shown the presence of immense oil and gas reserves, which could help Malaysia alleviate the growing domestic energy demands in the country. In late 2022, gas and hydrocarbon reserves were also found in the SK 320, SK 306, and SK 410B blocks of the Luconia Shoals, which Malaysia has persistently displayed interest in developing in the near future. As a response, China has increased intrusions into Malaysian waters, with its CCGs maneuvering in close proximity to Malaysia's mainland to disrupt Malaysian vessels and oil and gas explorations. Malaysia's development of the Kasawari gas fields also raised concerns among Chinese policymakers, expressed multiple times in bilateral meetings. Malaysia's decision to be persistent with oil and gas development in the Luconia Shoals is puzzling, as they have consistently adopted a policy of downplaying tensions in the South China Sea and ensuring that their actions do not aggravate China.

This study inquires into what the existing literature in maritime diplomacy takes as taken-for-granted maritime diplomatic events related to oil and gas developments in the South China Sea. Specifically, it argues that assessing the maritime diplomatic properties can reveal unique trends of Malaysian policymakers' motives, trajectories, and significance of the maritime diplomatic events taken. Informed by Le Mière's analytical framework of maritime diplomatic properties, this article concludes the following properties evident: sustainment, pre-emptive, explicitness, moderate kinetic effect, and asymmetrical power relations.

It falls under the category of sustainment and pre-emptive because Malaysian policymakers take no impromptu actions in developing their oil and gas explorations. Since discovering the Kasawari gas field in 2012, Malaysian policymakers have been transparent about their intentions to keep exploring the Luconia Shoals and start the production processes of the gas fields that have been discovered. Actions at sea are also consistent with the rhetoric imposed, as the RMN only responds to instances in which the CCG purposefully intrudes Malaysian waters located in close proximity to its mainland. Malaysia's non-military vessels have also solely been deployed for developing the gas fields, not assertive maneuvers to advance Malaysia's claims in the South China Sea.

With the involvement of the RMN, there are interpretations stating that Malaysia is taking a coercive turn in the South China Sea disputes. This article finds that the utilization of the RMN is reactive; however, it is deployed coincidentally because of the navies' mandate to maintain Malaysia's sovereign waters. Malaysia's utilization of navies also does not indicate a strong element of kinetic effect, as the lethal weaponry under the disposal of the RMN was not used to showcase a coercive message to China.

However, a maritime diplomatic property that should be of concern is the asymmetrical power relations between Malaysia and China. As depicted in this article, the power relations are significant, allowing the conclusion that the future trajectory of the relations will remain stagnant as present in the status quo. China is predicted to continue its power projections at the Luconia Shoals and further its assertive maneuvers vis-à-vis Malaysia's exploration and development of oil and gas in the South China Sea. This maritime diplomatic property also reveals that Malaysia will maintain a downplaying posture vis-à-vis China's presence at sea. In the past, Malaysian policymakers have been flexible with their South China Sea stance. Despite opposition by Chinese officials in regard to Malaysia's policies to explore the Luconia Shoals, Malaysia is maintaining the position of flexibility and reassurance that negotiations continue to be open.

BP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AF (2023). China Concerned About Malaysian Project in SC Sea: Anwar. Asia Financial. Available online at: https://www.asiafinancial.com/china-concerned-about-malaysian-project-in-sc-sea-anwar (accessed August 28, 2023).

Ahmad, M. Z., and Sani, M. A. M. (2017). China's assertive posture in reinforcing its territorial and sovereignty claims in the South China Sea: an insight into Malaysia's stance. Jpn. J. Polit. Sci. 18, 67–105. doi: 10.1017/S1468109916000323

Alderwick, J., and Giegerich, B. (2010). Navigating troubled waters: NATO's maritime strategy. Survival 52, 13–20. doi: 10.1080/00396338.2010.506814

AMTI (2021). Contest at Kasawari: Another Malaysian Gas Project Faces Pressure. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/contest-at-kasawari-another-malaysian-gas-project-faces-pressure/ (accessed May 5, 2023).

AMTI (2023a). (Almost) Everyone is Drilling Inside the Nine-Dash Line. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/almost-everyone-is-drilling-inside-the-nine-dash-line/ (accessed August 28, 2023).

AMTI (2023b). Flooding the Zone: China Coast Guard Patrols in 2022. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/flooding-the-zone-china-coast-guard-patrols-in-2022/ (accessed April 25, 2023).

AMTI (2023c). Perilous Prospects: Tensions Flare at Malaysian, Vietnamese Oil and Gas Fields. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/perilous-prospects-tensions-flare-at-malaysian-vietnamese-oil-and-gas-fields/ (accessed May 5, 2023).

AMTI (2023d). South China Sea Energy Exploration and Development. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/south-china-sea-energy-exploration-and-development/ (accessed August 31, 2023).

Basawantara, A. A. G. (2020). Countering China's Paragunboat Diplomacy in the South China Sea: The Responses of the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia. President University. Available online at: http://repository.president.ac.id/xmlui/handle/123456789/4770 (accessed February 17, 2023).

Bing, N. C. (2022). Malaysia-China Defence Ties: Managing Feud in the South China Sea. RSIS. Available online at: https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/rsis/malaysia-china-defence-ties-managing-feud-in-the-south-china-sea/#.ZFUnC-zMK2p (accessed May 5, 2023).

Blazevic, J. J. (2012). Navigating the Security Dilemma: China, Vietnam, and the South China Sea. J. Curr. Southeast Asian Aff. 31, 79–108. doi: 10.1177/186810341203100404

Cable, J. (1994). Gunboat Diplomacy. London: Palgrave Macmillan Publishers. Available online at: https://link.springer.com/book/9780312353469 (accessed December 19, 2021).

Chang, Y. C. (2018). The “21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative” and naval diplomacy in China. Ocean Coast. Manag. 153, 148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.12.015

Chang, Y. C. (2022). Toward better maritime cooperation—a proposal from the Chinese perspective. Ocean Dev. Int. Law 53, 85–104. doi: 10.1080/00908320.2022.2068704

Chew, A. (2022). Malaysia Must Shift From ‘Jungle Warfare' to Keep Eye on Chinese Boats in South China Sea, Militants, as Maritime Threats Rise. South China Morning Post. Available online at: https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3164457/malaysia-must-shift-jungle-warfare-keep-eye-chinese-boats (accessed May 5, 2023).

Chew, A. (2023). Malaysia's Energy Needs Face Chinese Pushback in South China Sea. Al Jazeera. Available online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2023/4/25/malaysian-energy-needs-clash-with-china-claims-in-south-china-sea (accessed May 5, 2023).

Darwis and Putra, B. A. (2022). Construing Indonesia's maritime diplomatic strategies against Vietnam's illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing in the North Natuna Sea. Asian Aff. 49, 172–192. doi: 10.1080/00927678.2022.2089524

Davidson, B. (2008). Modern Naval Diplomacy - a practitioner's view. J. Milit. Strat. Stud. 11, 1–47. Available online at: https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/journals/jomass/v11i1/f_0028140_22906.pdf

Dolbow, J. (2018). Malaysia Coast Guard Is One to Watch. U.S. Naval Institute. Available online at: https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2018/april/malaysia-coast-guard-one-watch (accessed May 5, 2023).

Emont, J. (2023). Indonesia Risks Confrontation With China Over Gas Project in South China Sea. The Wall Street Journal. Available online at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/indonesia-risks-confrontation-with-china-over-gas-project-in-south-china-sea-11673446347 (accessed August 31, 2023).

Espena, J., and Uy, A. (2020). Brunei, ASEAN and the South China Sea. Lowy Institute. Available online at: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/brunei-asean-south-china-sea (accessed February 22, 2023).

Fang, Y. (2018). Coast Guard Competition Could Cause Conflict in the South China Sea. East Asia Forum. Available online at: https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2018/10/27/coast-guard-competition-could-cause-conflict-in-the-south-china-sea/ (accessed April 25, 2023).

Giang, N. K. (2018). Vietnam's Response to China's Militarised Fishing Fleet. East Asia Forum, East Asia Forum. Available online at: https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2018/08/04/vietnams-response-to-chinas-militarised-fishing-fleet/ (accessed February 16, 2023).

Jacques, J. (2018). China Has Bought Brunei's Silence in South China Sea Dispute. The Trumpet. Available online at: https://www.thetrumpet.com/16927-china-has-bought-bruneis-silence-in-south-china-sea-dispute (accessed March 20, 2018).

Kreuzer, P. (2016). A Comparison of Malaysian and Philippine responses to China in the South China Sea. Chin. J. Int. Polit. 9, 239–276. doi: 10.1093/cjip/pow008

Kuik, C.-C. (2008). The essence of hedging: Malaysia and Singapore's response to a rising China. Contemp. Southeast Asia 30, 159–185. doi: 10.1355/CS30-2A

Lai, Y. M., and Kuik, C. C. (2020). Structural sources of Malaysia's South China Sea policy: power uncertainties and small-state hedging. Austr. J. Int. Aff. 75, 277–304. doi: 10.1080/10357718.2020.1856329

Lansing, S. (2018). A White Hull Approach to Taming the Dragon: Using the Coast Guard to Counter China. War on the Rocks. Available online at: https://warontherocks.com/2018/02/white-hull-approach-taming-dragon-using-coast-guard-counter-china/ (accessed April 25, 2023).

Le Mière, C. (2011). The return of gunboat diplomacy. Survival 53, 53–68. doi: 10.1080/00396338.2011.621634

LI (2023). Map - Lowy Institute Asia Power Index. Lowy Institute. Available online at: https://power.lowyinstitute.org/ (accessed October 24, 2023).

Mahan, A. T. (1898). The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company.

Mangosing, F. (2019). Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei Navies Stage Drills Near South China Sea. Global News, Inquirer.Net. Available online at: https://globalnation.inquirer.net/179664/philippines-vietnam-brunei-navies-stage-drills-near-south-china-sea (accessed September 8, 2020).

Masih, N. (2023). China Uses Laser on Philippine Coast Guard; U.S. Responds. The Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/02/13/china-laser-philippines-coast-guard/ (accessed April 27, 2023).

Meyer, P. K., Nurmandi, A., and Agustiyara, A. (2019). Indonesia's swift securitization of the Natuna Islands how Jakarta countered China's claims in the South China Sea. Asian J. Polit. Sci. 27, 70–87. doi: 10.1080/02185377.2019.1590724

MOFAM (2023). Malaysia's position on the South China Seas. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Malaysia. Available online at: https://www.kln.gov.my/web/guest/-/malaysia-s-position-on-the-south-china-sea (accessed May 5, 2023).

NBR (2023). Country Profile from the Maritime Awareness Project Malaysia. The National Bureau of Asian Research. Available online at: https://www.nbr.org/publication/malaysia/ (accessed May 5, 2023).

Noor, E. (2016). “The South China Sea dispute: options for Malaysia,” in The South China Sea Dispute, eds I. Storey, and C.-Y. Lin (Singapore: ISEAS Publishing).

Noor, E., and Qistina, T. N. (2017). Great power rivalries, domestic politics and Malaysian foreign policy. Asian Sec. 13, 200–219. doi: 10.1080/14799855.2017.1354568

Oshige, M. (2023). China Coast Guard's Intrusions Around Japan's Senkakus Show They Stay Longer. NetworkAsia News Network. Available online at: https://asianews.network/china-coast-guards-intrusions-around-japans-senkakus-show-they-stay-longer/ (accessed April 27, 2023).

Parameswaran, P. (2019). Managing the Rise of Southeast Asia's Coast Guards. Washington DC. Available online at: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/managing-the-rise-southeast-asias-coast-guards (accessed February 16, 2023).

Pattiradjawane, R. L., and Soebagjo, N. (2015). Global maritime axis: Indonesia, China, and a new approach to Southeast Asian Regional Resilience. Int. J. China Stud. 6, 175–185. Available online at: https://ics.um.edu.my/img/files/rene-natalia.pdf

Pemmaraju, S. R. (2016). The South China Sea arbitration (The Philippines v. China): assessment of the award on jurisdiction and admissibility. Chin. J. Int. Law 15, 265–307. doi: 10.1093/chinesejil/jmw019

Percy, S. (2016). Maritime crime and naval response. Survival 58, 155–189. doi: 10.1080/00396338.2016.1186986

Putra, B. A. (2022). Gauging contemporary maritime tensions in the North Natuna Seas: deciphering China's maritime diplomatic strategies. Int. J. Interdiscip. Civic Polit. Stud. 17, 85–99. doi: 10.18848/2327-0071/CGP/v17i02/85-99

Putra, B. A. (2023a). Rise of constabulary maritime agencies in Southeast Asia: Vietnam's paragunboat diplomacy in the North Natuna Seas. Soc. Sci. 12, 241. doi: 10.3390/socsci12040241

Putra, B. A. (2023b). The rise of paragunboat diplomacy as a maritime diplomatic instrument: Indonesia's constabulary forces and tensions in the North Natuna Seas. Asian J. Polit. Sci. 31, 106–124. doi: 10.1080/02185377.2023.2226879

Qi, H. (2019). Joint development in the South China sea: China's incentives and policy choices. J. Contemp. East Asia Stud. 8, 220–239. doi: 10.1080/24761028.2019.1685427

Reuters (2023a). Malaysia Says It Will Protect Its Rights in South China Sea. Reuters. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/malaysia-says-it-will-protect-its-rights-south-china-sea-2023-04-08/ (accessed May 5, 2023).

Reuters (2023b). Vietnam Rebukes China, Philippines Over South China Sea Conduct. Reuters. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/vietnam-rebukes-china-philippines-over-south-china-sea-conduct-2023-05-18/ (accessed June 12, 2023).

RFA (2021). Analysts: Malaysia's Navy Drill Sends Strong Message to South China Sea Claimants. Radio Free Asia. Available online at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/malaysia-drill-08202021155721.html (accessed May 6, 2023).

RFA (2023). China Coast Guard ‘Harassed' Philippine Counterpart, Security Expert Says. Radio Free Asia. Available online at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/china-philippine-coast-guard-02072023025449.html (accessed April 25, 2023).

Srivastava, P. (2022). The South China Sea: Malaysian Dilemma. The Geopolitics. Available online at: https://thegeopolitics.com/the-south-china-sea-malaysian-dilemma/ (accessed May 5, 2023).

Storey, I. (2020). Malaysia and the South China Sea Dispute: Policy Continuity amid Domestic Political Change. Singapore: ISEAS Perspectives.

Syailendra, E. (2022). The Sense and Sensibility of Malaysia's Approach to its Maritime Boundary Disputes. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/the-sense-and-sensibility-of-malaysias-approach-to-its-maritime-boundary-disputes/ (accessed May 5, 2023).

Wey, A. L. K. (2017). A small state's foreign affairs strategy: making sense of Malaysia's strategic response to the South China Sea debacle. Comp. Strat. 36, 392–399. doi: 10.1080/01495933.2017.1379830

Yahuda, M. (2013). China's new assertiveness in the South China Sea. J. Contemp. China 22, 446–459. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2012.748964

Yusof, I. M., and David, N. (2023). Malaysian, Japanese Coast Guards Hold South China Sea Security Drill. Radio Free Asia. Available online at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/southchinasea/malaysiajapandrills-01132023133204.html (accessed May 5, 2023).

Keywords: maritime diplomacy, South China Sea, energy reserve explorations, Malaysia, China

Citation: Putra BA (2023) Deciphering the maritime diplomatic properties of Malaysia's oil and gas explorations in the South China Sea. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1286577. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1286577

Received: 31 August 2023; Accepted: 28 November 2023;

Published: 19 December 2023.

Edited by:

Thania Isabelle Paffenholz, Inclusive Peace, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Muhamad S. Olimat, Anwar Gargash Diplomatic Academy, United Arab EmiratesCopyright © 2023 Putra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bama Andika Putra, YmFtYS5wdXRyYUBicmlzdG9sLmFjLnVr

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.