- 1Humanities and Social Sciences (Cornwall), University of Exeter, Penryn, Cornwall

- 2Social and Political Sciences, Philosophy, and Anthropology, University of Exeter, Exeter, Devon

- 3School of Social Sciences, Birkbeck, University of London, London, United Kingdom

Social identities, such as identification with the nation, are regarded as core variables in explanations of political attitudes and behaviors. In these accounts, increases in the importance of an identity such as “Englishness” are often seen to be accompanied by decreases in the importance of other, more inclusive, identities such as “British” or “European.” At the same time, increases in exclusive national identities like “Englishness” present challenges to democratic states because they are associated with preferences such as support for Brexit and intolerance of outgroups. Yet we know comparatively little about the relative importance to individuals of different social identities, the extent of changes in the strength of those social identities with contextual shifts, the interrelationships between different social identities, and the influences on different social identities. In this paper, we address each of these questions using a five-wave online panel study administered over two years of the COVID-19 pandemic in England from 2020 to 2022, in which we asked about the importance of eight identities—Europeanness, Britishness, Englishness, the local area, gender, age, race/ethnicity, and social class. We show that national identity is consistently less important to individuals than the social identities of gender and age, though more important than race/ethnicity and social class. We also show that there were general increases in identification with almost all these groups during COVID. We consider why and discuss the implications for our understanding of increases in the strength of national identity as a challenge to democratic states.

Introduction

The importance of social identities to political attitudes and behaviors is uncontested (Huddy, 2013). They predict in-group preferences and can also foster hostility and discrimination toward outgroups, for example. This begs the question of when and why social identities become salient. Sherif's Robber's Cave experiment provided an initial answer by demonstrating the speed and intensity with which identities can form around competition for resources (Sherif, 1954), while Tajfel and Turner's (1979) self-categorization theory showed the ease with which groups are formed and in-group members favored, even when they are not known and when there is no expectation of future interactions. Tajfel and Turner also provided an explanation for why group identifications develop: they bolster members' distinctiveness—group identification is positive—and self-esteem.1

Social identities and associated ideas such as linked fate now inform a range of theories of attitudes and behaviors, from altruism (Monroe, 1996), to prejudice (Reynolds et al., 2016), polarization (Hetherington and Weiler, 2018; Mason, 2018), and support for nationalist politicians and politics such as Brexit (Chan et al., 2020). More recently, the prevalence and threat of infectious diseases from outside the group, such as COVID-19, have been associated with preferences for authoritarian governance (Zmigrod et al., 2021), favoring restrictions on the civil liberties of minorities (Hinckley, forthcoming), and strengthened national identity (Sibley et al., 2020). Given that “emerging infectious diseases have been increasing in frequency over the past five decades” (Daszak et al., 2021, p. 204)—with avian flu, swine flu, Ebola, and COVID-19 examples from just the last 15 years—and considering other leading challenges to democracy affected by social identities, such as the threat from authoritarianism, understanding salience and change in social identities is more important now than ever.

How are the social identities that are influences on political attitudes and preferences affected by threats like COVID-19? Do individuals seek safety in objects of identity such as the nation, rallying around the flag and tightening the boundaries of membership of national in-groups? Or are social identities more closely linked to specific aspects of the context such as its impact on subgroups of social class or race/ethnicity? Despite the longevity of social identity theory, there are three aspects of identities about which we know comparatively little with respect to these questions: the relative importance of different social identities to individuals, e.g., national identity vs. class identity, the extent to which identities change together over time, and comparative influences of variables such as age, social class and race/ethnicity on different identities.

This paper uses online panel survey data, gathered in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in England, to address these questions. Drawing on the themes of this issue, we ask how place-based identities, such as national identity, changed during the pandemic. But we also put these changes into context by comparing them to changes in other social identities such as those based on class and race/ethnicity. In so doing, we show that while identities such as Britishness and Englishness strengthened over the course of the pandemic, so too did other identities including class, race/ethnicity, and gender. This provides new evidence about the dynamics of different social identities, suggesting the possibility of a general “groupiness,” as opposed to alternatives, such as negative relationships in which when a social identity such as Britishness comes into the foreground others such as Englishness recede into the background. We discuss the implications for our understanding of national and other social identities in the context of the social, political and economic challenges in democratic states presented by contemporary threats such as COVID-19. We suggest that it implies a more nuanced meaning to increases in the strength of national identity if they are accompanied by increases in other cross-cutting identities such as class and race/ethnicity. However, most research designs heretofore have not allowed examination of these questions.

Previous research

The salience of national and other place-based identities

While individuals may have objective attributes that make them members of groups, e.g., female, young, ethnic minority, such attributes alone are not enough for identification with these groups. For gender, age or ethnicity to be an important social identity the individual needs to be conscious of the group and to identify other members of the group as sharing interests based on membership. Thus, according to Tajfel (1981, p. 255), a social identity involves an individual's “knowledge of his membership in a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to the membership.”

This means that while processes such as childhood socialization are important to the development of identities, so too is context in shifting the significance of social or group-based identities over individual identity, as well as in shifts in the importance of different social identities for the same individual (Turner, 1987). For example, movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter may prime greater consciousness of gender and ethnic identity, the Brexit debate in the United Kingdom (UK) is likely to have strengthened national identities such as Britishness and Englishness for Leave supporters and European identity for Remain supporters, and increases in immigration may increase the strength and salience of national identity.

Indeed, national identity is often paramount in efforts to understand responses to contextual changes of increased threat. For example, Kam and Ramos (2008) show that national identity among Americans was particularly salient in the context of the aftermath of 9/11—then fading over time relative to partisan identity as partisan disagreement returned. National identity also tends to be associated with increased prejudice toward immigrants and other minorities, who are perceived as threats (Blank and Schmidt, 2003; De Figueiredo and Elkins, 2003; Weiss, 2003; Pehrson et al., 2009; Green et al., 2011). In the British context, Henderson and Wyn-Jones show both how English identity has changed over time—English identity has grown in importance in the context of Scottish and Welsh devolution and the perceived threats to national identity posed by the European Union—and how British identity, which is more inclusive than identity as English and indicative of more support for the European Union, has declined somewhat relative to English identity.

Although national identity tends to dominate, other place-based identities, such as with the local area or region, have also been considered. Previous research in several different countries tells us that trust in local government is not simply a reflection of trust in national government, for example (e.g., Rahn and Rudolph, 2002; McKay, 2019). Indeed, trust in local government tends to be higher than trust in national government (Denters, 2002) due to distinct local identities as well as a closer relationship between local government and its constituents.2

Rarely, however, do these studies examine the salience of place-based identities relative to other social identities, as opposed to relative to each other, e.g., national vs. local identity. In other words, the tendency of previous research is to analyze the salience of national and other place-based identities in a vacuum, without putting them into context next to other social identities. We know little about the strength of place-based identities such as national identity compared to other social identities such as race and class, and thus about the full meaning of changes in the importance of national identity to individuals. This leads us to our first research question:

RQ1: Are place-based identities such as national identity more important to individuals than other social identities such as those based on race/ethnicity or social class?

Changes in place-based and other social identities

There are two distinct aspects to questions of changes in social identities: first, the stability of specific social identities such as national identity, and second, how changes in social identities such as with the nation are related to changes in other social identities, such as with the local area, or with social identities beyond those based on place, such as race/ethnicity and class. With respect to the first question, the original theories of social identity and social categorization emphasized fluidity in the importance of different social identities, as the salience of groups to which individuals belong fluctuates with changing contexts. In this vein, authors such as Hogg et al. (1995, p. 261) describe social identity as, “highly dynamic: it is responsive, in both type and content, to intergroup dimensions of immediate social comparative contexts.” On the other hand, Huddy claims “considerable stability evinced by diverse political identities” that is at odds with notions of social identities as highly changeable (Huddy, 2001, p. 131).

With respect to the second question of the relationships between changes in different social identities, previous research tells us that individuals possess multiple social identities and that these may come to the foreground or fade to the background depending on situational primes. Some of that research suggests trade-offs, or a negative relationship between different social identities. Huddy's discussion of change in the salience of social identities refers to authors who “record an increase in the intensity of ethnic identity and a decline in occupational and class identities closer to elections, especially competitive elections” (Huddy, 2013, p. 758, our italics), for example. Similarly, the identities of Britishness and Englishness are often presented as alternatives—as Britishness goes down Englishness goes up (though see Henderson and Wyn Jones, 2022, p. 56).

These findings may be partly a function of how social identities are measured. If, as in Eifert et al.'s (2010) analysis using the Afrobarometer, described by Huddy, respondents are asked “the group you feel you belong to first and foremost,” the naming of one group inevitably displaces another. Similarly, if the salience of group identities is based on rankings of importance, increases in the rankings of some groups will be accompanied by decreases in the rankings of others. In neither example can we tell whether the absolute strength of different identities has increased or decreased, however.

But the idea that as the strength of one identity comes to the foreground others inevitably fade to the background appears not be merely a function of measurement. For example, Inglehart (1977) predicted a negative relationship in strength of identity between identifying strongly with a local area or region and identifying as European because he saw local identity as impinging on the possibility of European identity (see Medrano and Gutiérrez, 2001, p. 756–757 for a discussion of this claim by Inglehart and others). Similarly, Brewer and Brown argue that, “As contexts change, the importance of superordinate category membership may diminish while subgroup identities remain available as a primary basis for group loyalties and attachment” (Brewer and Brown, 1998, p. 582), implying a likely negative relationship between the salience of superordinate and subgroup identities.

An alternative perspective on the relationships between different social identities is the notion of dual (Moreno, 2006) or nested identities (Medrano and Gutiérrez, 2001). Residency in a local area or region, for example, may be “nested” in residency in England, which is part of Great Britain, which is in turn nested in Europe. Not only could an individual strongly identify with all four places, but the implication for change is that an increase in identity as, for example, British could be accompanied by an increase in the strength of a nested identity such as English if both became more salient and neither impinges on the other. Thus, as one identity comes to the foreground it may not be the case that others fade to the background.

While suggesting the possibility of positive relationships, the idea of nested identities pertains to place-based social identities. Tensions remain surrounding expectations for changes in broader social identities that are neither nested nor incompatible, but multiple and potentially overlapping with each other, e.g., national and class identity or local and race/ethnic identity. There is a need to examine this question with measures that allow us to assess both absolute and relative changes in the salience of different social identities if we are to understand social identities and the opportunities and challenges they present in democratic states.

RQ2: What are the relationships between increases and decreases in the salience of different social identities?

Influences on different social identities

Previous research is clear that individual-level attributes such as race, age, and education, in contexts of situational changes from terrorist attacks to pandemics and increased immigration, affect identities and changes in identities. They influence group membership, how it is defined, and how group interests are perceived. There is also evidence that direct experience, with crime (Bateson, 2012), unemployment (Rosenstone, 1982) and climate change (Akerlof et al., 2013), for example, influences political identities and behavior. But are direct experiences such as competing with immigrants for jobs or living in an area with rapid changes in population (Goodwin and Milazzo, 2017; Chan et al., 2021), the principal contributors to the salience of particular social identities or are individual attributes such as age or gender more influential, implying that indirect experiences that combine with group membership and interests may be more critical? For example, is gender particularly influential on changes in the strength of gender identity?

Previous research has not provided clear answers to these questions because interest is often on the impact of context on a single identity—or type of identity in the case of place-based nested identities—and its consequences, more than on the individual-level influences. Without both gauging the relative influence of individual-level attributes and direct experiences on the salience of identity, and doing so for multiple social identities, we lack understanding of the implications of contexts such as newly emergent threats for democratic states.

RQ3: What are the relative contributions of individual-level attributes such as race/ethnicity, age, gender and education as opposed to direct experiences, e.g., economic hardship, to the importance of identities?

Social identities in the context of COVID-19

Previous research has also examined social identities during COVID-19; indeed, social identities are argued to have played a large role in attitudinal and behavioral responses. Our interest is in COVID's impact on social identities themselves, however. Previous research suggests that the context of the threat of COVID-19 would be identity-affirming. Threats from outside a group such as COVID-19 typically increase the strength and salience of group identity, partly because prosocial behavior reduces threat perceptions (Ho et al., 2020).3 But which group identities does it strengthen? Different arguments and evidence are somewhat in tension.

On the one hand, some authors suggest a strengthening of more inclusive, shared, superordinate identities, e.g., to the nation, in the face of the threat. For example, Vignoles et al. argue that, “shared identities may function as a social cure, helping people cope with the uncertainty and strains of a pandemic” and that political leaders in particular, “establish[ing] the collective social subject … and the desired collective responses” (819). Haslam (2021, p. 36) also argues that, “leaders need to represent us, and in a crisis ‘us' becomes more inclusive.” With specific reference to the UK, Butler noted early in the pandemic that:

There has … been a remarkable flowering of more formal forms of solidarity. In the U.K. alone, some one million people volunteered to help the NHS and over four thousand mutual aid groups have been formed, involving over three million people. There have been so many offers of solidarity that there has sometimes not been enough for people to do (Butler, 2020).

Indeed, using survey panel data, Sibley et al. (2020) show a strengthening of national identity over time in New Zealand. However, Chan et al. (2021) do not find a similar increase in China or the United States, where national identity decreased somewhat. They suggest that national identity may decrease when a country's response to COVID is perceived to be ineffective. Going beyond national identity, Stevenson et al. find a strengthening of identity with the local community in the 6 months from November 2019 in the UK, perhaps because of a focus on the local level due to regional variations in lockdowns, and thus an increased local stake in the effectiveness of responses (Stevenson et al., 2021; see also Lalot et al., 2020). Indeed, Donnelly (2021) contends that COVID provided contexts of group-based “linked fate” that included regional linked fate.

On the other hand, there are arguments that COVID-19 primed subgroup rather than superordinate identities as a result of uncertainty, isolation, divisive rhetoric and media coverage of effects that were identifiably different for some groups than others in Britain and elsewhere (Hanson et al., 2022; Ittefaq et al., 2022).4 In line with these arguments, Jetten (2021) discusses various group inequalities of COVID, including by social class and race—poorer and minority individuals were more likely to be key workers and to live in densely populated housing in which it was harder to stop the spread of the disease—Huo (2021) refers to the “activation of longstanding foreigner stereotypes” (see also, Tong et al., 2022; Desmarais et al., 2023) and Kahn and Money (2022) to race-based social identity threat. In terms of media coverage, Lalot et al. (2020, p. 9) point to blame attributed to young people, minorities, and a focus on the North-South divide in England and also to increased public perceptions of divisions between young and old, wealthy and poor, and the UK and Europe between May and October 2020.

There may also be a time dimension to these different perspectives on social identities during the COVID-19 pandemic. National and other place-based identities appear to have been salient at the beginning of the pandemic, which is typical of crises in which group identities strengthen, but evidence of discrimination and division as the pandemic unfolded could have primed subgroup identities. Indeed, Abrams et al. describe the waning of perceptions of a national linked fate in these terms: “as the pandemic progressed, and comparisons between subordinate groups or cross-cutting categories have become increasingly salient (e.g., growing awareness of national, regional, ethnic, and age differences in infection rates) … people have started questioning the superordinate identity, leadership, rules, and restrictions” (Abrams et al., 2021, p. 202). This suggests that an increase in importance of national identity early in the pandemic was followed by an increase in the salience of other identities such as age, race/ethnicity and region rather than additional strengthening of national identity.

What of direct experiences of COVID-19? What kinds of experiences of COVID-19 may be salient to social identities? Direct experiences of COVID-19, including economic hardship such as loss of income (Collins et al., 2021), suffering mental health challenges, getting the disease or losing a family member or friend to the disease, could be suggestive of perceptions of failures to address the pandemic adequately that Chan et al. argue contributed to decreases in national identity (Chan et al., 2021). But such direct experiences of COVID-19 could also prime other group identities associated with these outcomes, such as social class as a result of financial challenges5, gender because of additional domestic responsibilities borne by women6, or race/ethnic identity among minorities as a result of losing a family member or friend to the disease7, serving as a reminder of the disease's disproportionate impact on ethnic minorities.

While previous studies have examined the relationships between experiences with COVID such as personal exposure to the virus, reduced working hours or being furloughed (Dryhurst et al., 2020; Devine et al., 2021; Rump and Zwiener-Collins, 2021), to our knowledge the impact of other effects of the virus, such as home schooling or feelings of loneliness and isolation, have either been ignored in research on the politics of COVID or gauged indirectly, e.g., by whether or not an individual has children at home (Rump and Zwiener-Collins, 2021). Moreover, the relationships between direct experiences of COVID-19 and social identities have not been explored: for example, Collins et al. (2021) compare the impact of direct experiences of COVID relative to social identities on emotional responses to COVID rather than their influence on identities themselves.

In sum, the COVID-19 pandemic presents an ideal context in which to test our three research questions about changes and relationships between different social identities. As a result of its uneven impact, as well as the rhetoric of leaders, other elites and the media, COVID-19 simultaneously primed a number of identities, including nation, community, age, race/ethnicity and social class (Keys et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022). As well as general questions about social identities, it allows us to address some of the tensions in previous research on whether, how and why multiple social identities varied over time during the pandemic.

Data

To answer the three research questions, we analyze data from a five-wave online panel survey of individuals residing in England.8 The first four waves of the survey were roughly 3 months apart, starting in July 2020—the UK recorded its first official death from COVID-19 on March 5, 2020. Wave 1 surveyed a sample of 5,000 respondents in July 2020, when England was just emerging from its first national lockdown (total deaths officially due to COVID at the beginning of fieldwork: 40,952). Wave 2 of the panel re-interviewed 3,662 respondents in October/November 2020, a period of varying regional restrictions, with deaths having slowed since July but cases increasing (total deaths due to COVID at beginning of fieldwork: 45,729). Wave 3 took place at the end of the second peak of COVID infections and deaths in March 2021, and re-interviewed 2,500 respondents toward the conclusion of a second national lockdown that began in January 2021 (total deaths due to COVID at beginning of fieldwork: 123,468). Wave 4 was fielded in May 2021 and re-interviewed 1,803 panel respondents (total deaths due to COVID at beginning of fieldwork: 153,782), by which point daily deaths had slowed to near zero, the most severe lockdown restrictions had been removed (the last would be removed in July 2021, although some were reinstated at the end of 2021 with the spread of the Omicron variant), and the vaccination programme was in full swing. Finally, Wave 5 of the survey was administered a year later, in June 2022, at which point there were no restrictions and there had been no resurgence of cases comparable to April 2020 or January 2021. Eight hundred six respondents were interviewed for a fifth time (total deaths due to COVID at beginning of fieldwork: 199,936).

Supplementary Table A1 shows the profile of respondents in each wave of the survey on key demographics. It indicates that attrition meant the sample became increasingly skewed toward older respondents, but Supplementary Table A1 also shows that beyond age the sample remained representative of the population on key demographics such as gender, region and party identification. We also examined whether attrition was associated with strength of identity and include some discussion below Supplementary Table A1: the analysis does not suggest that attrition between waves was systematically skewed toward respondents with weaker (or stronger) social identities.

The key dependent variables in the estimates that follow pertain to social identities. According to Huddy (2013, p. 746), four measures of social identity have dominated the field: “the subjective importance of an identity, a subjective sense of belonging, feeling one's status is interdependent with that of other group members, and positive feelings for members of the in-group.” While there is some disagreement about whether all of these are indicators of social identity (Postmes et al., 2013), there is consensus that the subjective importance or centrality of a social identity is fundamental. In addition, Postmes et al. argue that it can be captured with a single survey question, while Sinnott demonstrates that questions asking for a “rating [of a group] in terms of identification,” such as “How important is it to you that you are European?” have the greatest construct validity relative to alternatives such as ranking or proximity to the group (Sinnott, 2006). Our surveys asked the question, “How important is the following to your sense of who you are?”9 on a 4-point scale from “Not important at all” to “Very important” (respondents could also choose “don't know”).

Our surveys referred to eight identities (in random order): Britishness, Englishness, Europeanness, the area where you live, your racial or ethnic background, your gender, your age/generation, and your class. This question gets most directly at the importance of the group. Alternative question formats like the Moreno measure of national identity force respondents to choose between options such as “identify as English (or European) more than British” and “identify as English (or European) and British equally,” which does not allow us to examine the dynamics of separate identities. For example, for a respondent saying “identify as English and British equally” in consecutive surveys, both identities could have stayed the same, both could have increased, or both could have decreased: the same answer encompasses all three possibilities. By contrast, the question we used gets at the gradations of the salience of an identity that are critical to being able to gauge absolute as well as relative social identity change (see also Medrano and Gutiérrez, 2001; Huddy and Del Ponte, 2019 use a 10-point scale), not just whether or not an individual identifies with a group.

We asked about the eight identities in each of the five survey waves. The answers allow us to examine RQ1 and RQ2. We assume that respondents attach the same meaning to these identities, which they may not, but it is not obvious that any such heterogeneity of meaning will bias our results in a particular direction.10 With regard to RQ3, in line with previous research we examine the influence of the demographics of age, gender, race, class and education (Bechhofer and McCrone, 2014; Bond, 2017; Huddy and Del Ponte, 2019; Henderson and Wyn Jones, 2022). We also control for party identification (partisanship) (Van Bavel et al., 2022) and for political knowledge (political sophistication) as a distinct measure from education: if the importance of identities such as with the nation are in part contingent on perceptions of government performance (Chan et al., 2021), knowledge of what government is doing could be an influence. We measure political knowledge with a combination of questions about Brexit and COVID-19 asked in the first four waves of the panel (see Supplementary Appendix for details). All variables, including age,11 are recoded from 0 to 1 to ease comparison of the strength of relationships.

To gauge the relative influence of direct experiences on social identities, we examine the effects of four different types of experience of COVID-19: financial difficulties such as more difficulty paying the rent or mortgage (maximum = 9); additional domestic responsibilities such as childcare and housekeeping (maximum = 3); mental health issues, including feeling isolated (maximum = 2); and experiences of the virus itself such as a friend or member of the family having the virus or dying from it (maximum = 3). These variables were also recoded from 0 to 1 and were asked in the first four waves of the panel.

Analysis

RQ1: Are place-based identities such as national identity more important to individuals than other social identities such as those based on race/ethnicity or social class?

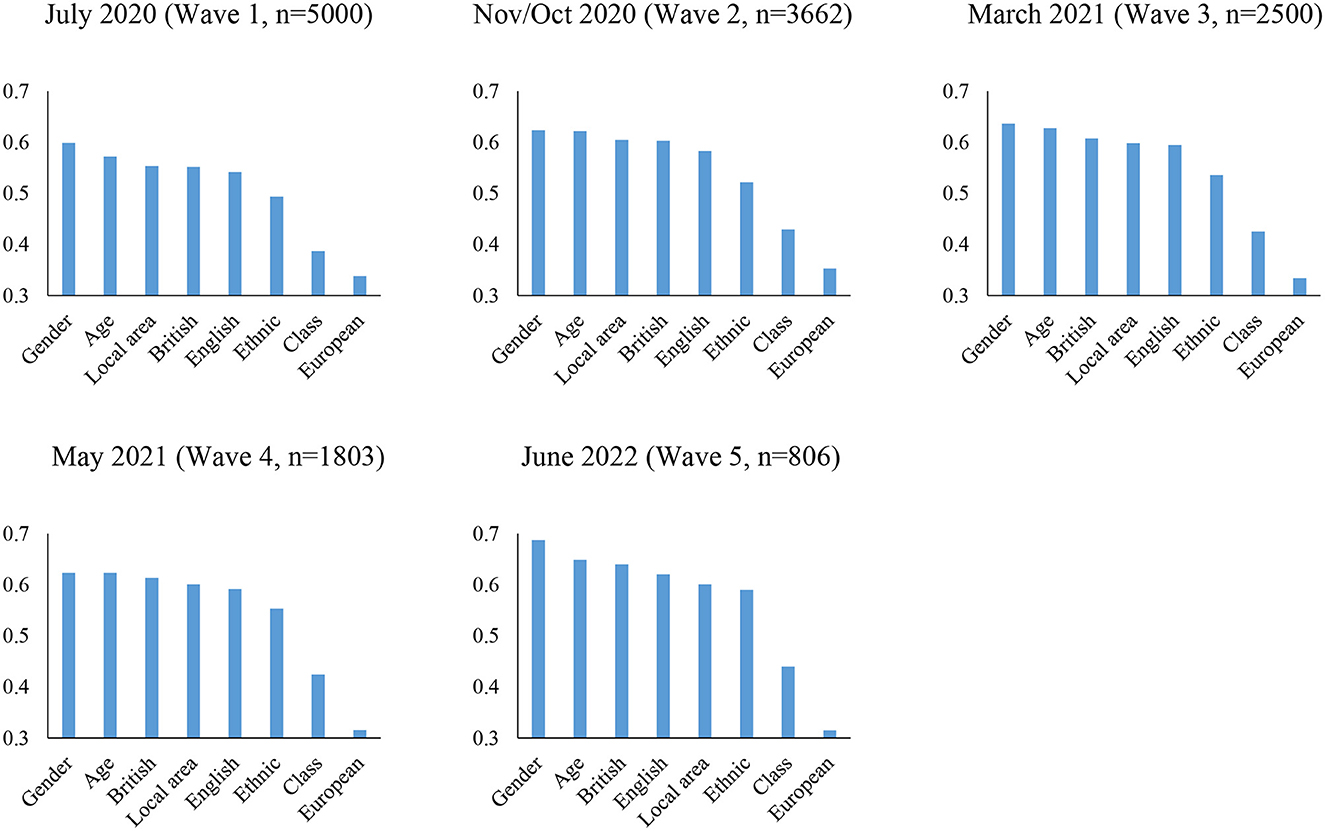

We begin by comparing the self-reported importance of the eight identities across the five survey waves, spanning almost 2 years, without any control variables. We order the answers from most to least average importance in each wave in Figure 1.12 The scale of importance runs from 0, or not at all important, through not very important (0.33) and important (0.67), to 1, or very important. Thus, importance above 0.5 indicates that the identity is closer to important on average than to not very important, while averages closer to 0.67 indicate more widespread perceptions that an identity is important or very important to respondents.

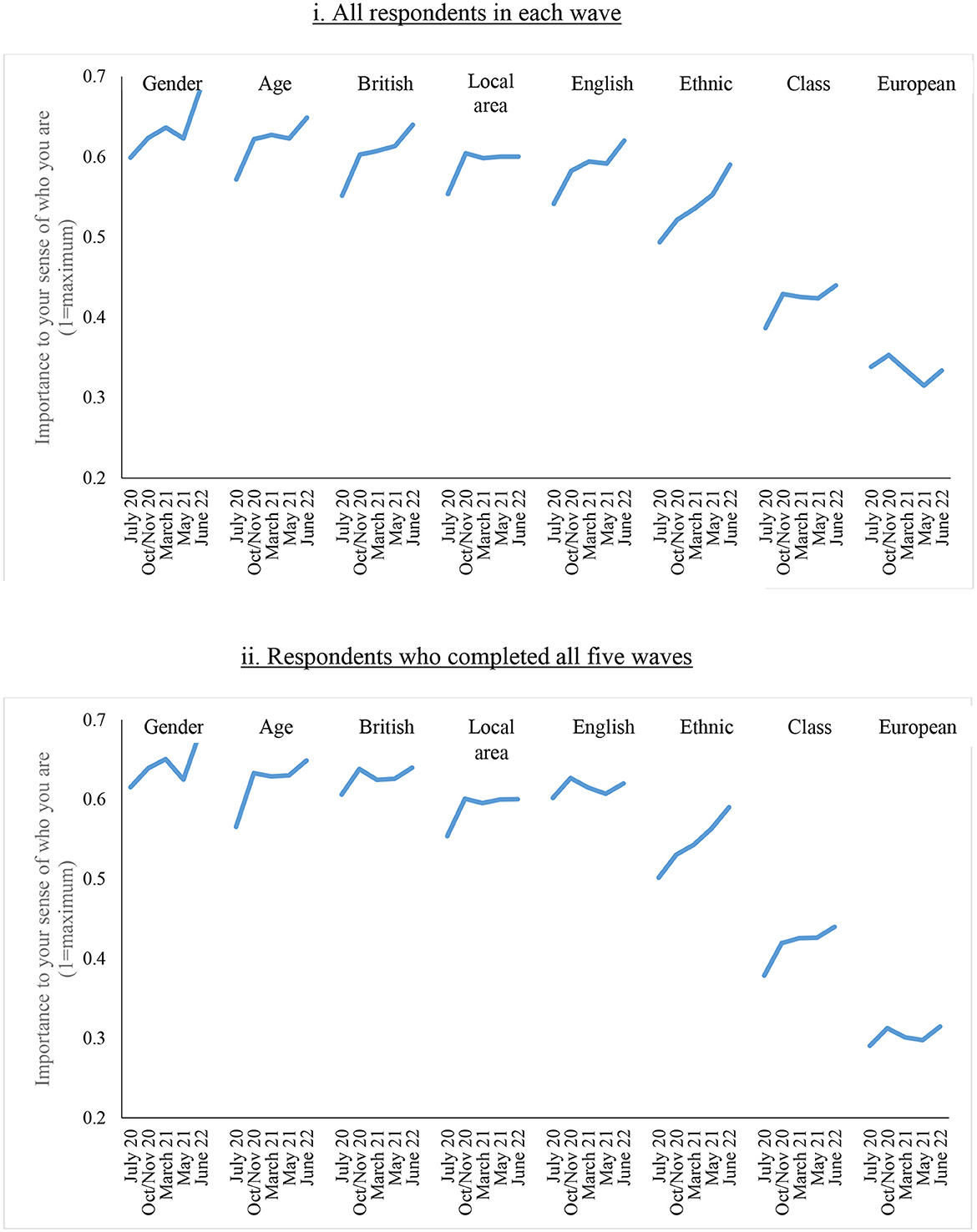

Figure 1. Importance of social identities over time (0 = not at all important, 1 = very important). Wave 1 n = 5,000, Wave 2 n = 3,662, Wave 3 n = 2,500, Wave 4 n = 1,803, Wave 5 n = 806. Source: ORB online panel survey.

Figure 1 shows a hierarchy of identities in which European identity clearly comes last, and ethnic and particularly class identity are somewhat more important but rated below the other five. The place-based identities of Britishness, Englishness, and the local area therefore rate highly, but their importance to respondents is superseded in every wave by gender and age. These differences should not be exaggerated, although they are not negligible either—about one-third of a standard deviation—and the mean importance of gender identity is statistically significantly larger than place-based identities in every wave (at p < 0.05). The pattern is the same for age identity in all but the final wave when the differences with place-based identities are no longer all statistically significant (gender and age differ from each other in average importance only in the first and last waves).

Thus, when we ask about a number of different identities, while national and other place-based identities are important they do not outweigh other identities such as gender and age. This is not an artifact of panel bias from attrition: in Supplementary Figure A1 we show the same patterns if we focus only on the roughly 800 respondents who took all five waves of the survey.

It is also striking how stable the ordering of the importance of identities is in Figure 1. Gender and age are always first and second, and ethnicity, class and Europeanness are always sixth, seventh, and last in importance. The only change in order is among British, English and local area identity, as the increase in the importance of local area identity between the July (Wave 1) and October/November 2020 (Wave 2) surveys, perhaps as a consequence of the regional lockdowns that were a feature of the UK's early response to COVID, ended while the strength of British and English identities continued to increase in subsequent waves. This leads us to the second research question.

RQ2: What are the relationships between increases and decreases in the salience of different social identities?

Figure 1 indicates that, with the exception of Europeanness, all identities increased in importance over the 2 years of the panel, some quite substantially. Figure 2i makes this clearer by showing the mean scores for the eight different identities over the five waves of the survey. With the exception of European identity, there were significant increases (at p < 0.05) in the importance of all identities between the first and second waves of the survey. These increases in importance then either continued over subsequent waves—gender, age, Britishness, Englishness—or stabilized at this higher level—local area and class.

Figure 2. Change in importance of identities, July 2020–June 2022. Wave 1 n = 5,000, Wave 2 n = 3,662, Wave 3 n = 2,500, Wave 4 n = 1,803, Wave 5 n = 806. (i) All respondents in each wave. (ii) Respondents who completed all five waves. n = 806. Source: ORB online panel survey.

As a further robustness check for the effects of panel attrition, Figure 2ii presents the mean scores in identities among the subset of the sample who completed all five waves of the survey. The patterns look very similar for these respondents, indicating genuine increases in the importance of most identities rather than an increasingly skewed sample over time. It is apparent from Figure 2ii, however, that respondents who stayed in the panel tended to have stronger British and English identities to begin with than respondents who dropped out, and weaker European identities. Nevertheless, focusing only on these respondents also shows that there were significant increases (at p < 0.05) in the importance of all identities between the first and second waves of the survey (including European identity). The main difference for respondents who stayed in the panel is that those increases in importance stabilized for Britishness and Englishness after the second wave (remaining statistically significantly higher at Wave 5 than at Wave 1).

The patterns of increases in identities in Figure 2 do not appear to support negative relationships between identities, in which an increase in one identity such as Britishness is accompanied by a decrease in other identities such as Englishness, local area identity, or race/ethnicity.

Nor do they support the idea of change over time in which British or English identity surged at the beginning of the pandemic and subgroup identities came to the fore later. But it is still possible that we see something different at the individual-level, such as a positive change in British identity accompanied by a negative change in local area identity. This is not the case, however.

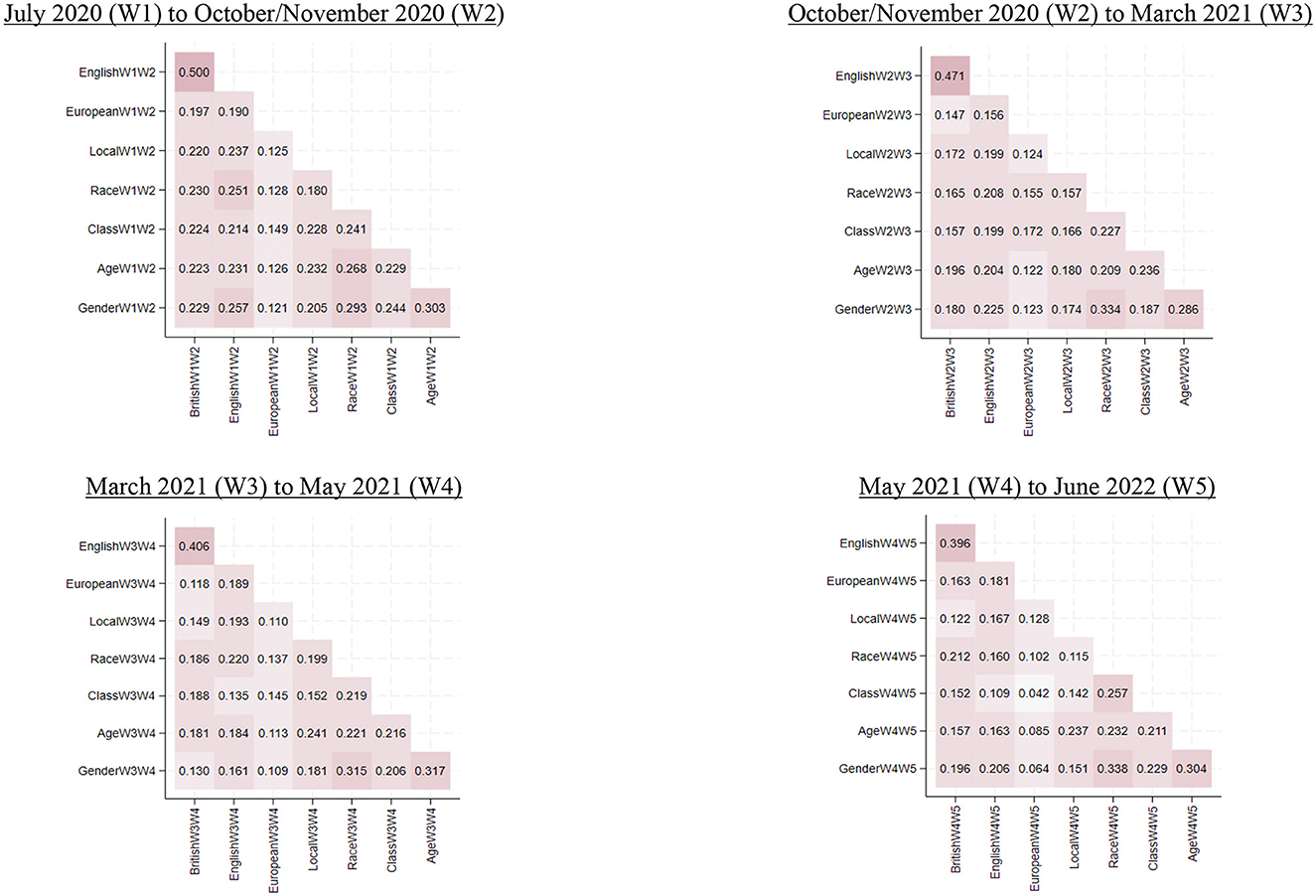

Figure 3 presents the correlations in changes in the importance of identities between waves—with deeper color showing stronger correlations. It shows that while the strength of the relationships varies from moderate, e.g., changes in the importance of British and English identity, to weak, e.g., changes in the importance of Europeanness and most of the other seven identities, none of the 112 correlations between changes in identities from wave to wave of the surveys is negative (we show these correlations for respondents who took all five waves in Supplementary Figure A1, all of which are also positive). Positive changes in the importance of one identity are always accompanied by positive changes in other identities in our surveys (and negative changes with negative changes).

Thus, even though it ranked as the least important identity among the eight, an increase in the importance of any of the other seven identities was also associated with an increase in the importance of European identity to respondents. There seems to be a general tendency for group identities to move together—even if, as Figures 1, 2 demonstrate, some move more than others.13

It is possible that the context of COVID-19 was unique in the way it primed multiple identities, with leaders such as UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson invoking national identity, while other leaders such as Nicola Sturgeon in Scotland may have reminded English respondents of their Englishness, and at the same time news of the impact of COVID referred to differences by age, race and class. But even if the COVID context was unique in these respects—and we are skeptical that it was—our analysis raises the possibility of broad increases in seemingly disparate identities, not just place-based, nested, identities—or what Karen Stenner describes in a different context as “groupiness” (Stenner, 2005, p. 18).14 We shed more light on this question as we explore the causes of variation in the importance of identities over time in our third research question.

RQ3: What are the relative contributions of individual-level attributes such as race, age, gender and education, as opposed to direct experiences, e.g., economic hardship, to the importance of identities?

To answer RQ3, we use four of the five waves of panel data—further direct experiences with COVID-19 were not gauged in the June 2022 survey—to examine variation in the importance of individual-level social identities. We look at explanations for the importance of the eight identities as a function of variation in individual-level characteristics such as social class and gender, and respondent's experiences of COVID-19, such as financial hardship and additional domestic responsibilities. In these models the data are stacked, such that a respondent interviewed in four waves is treated as four observations, clustered by waves.15

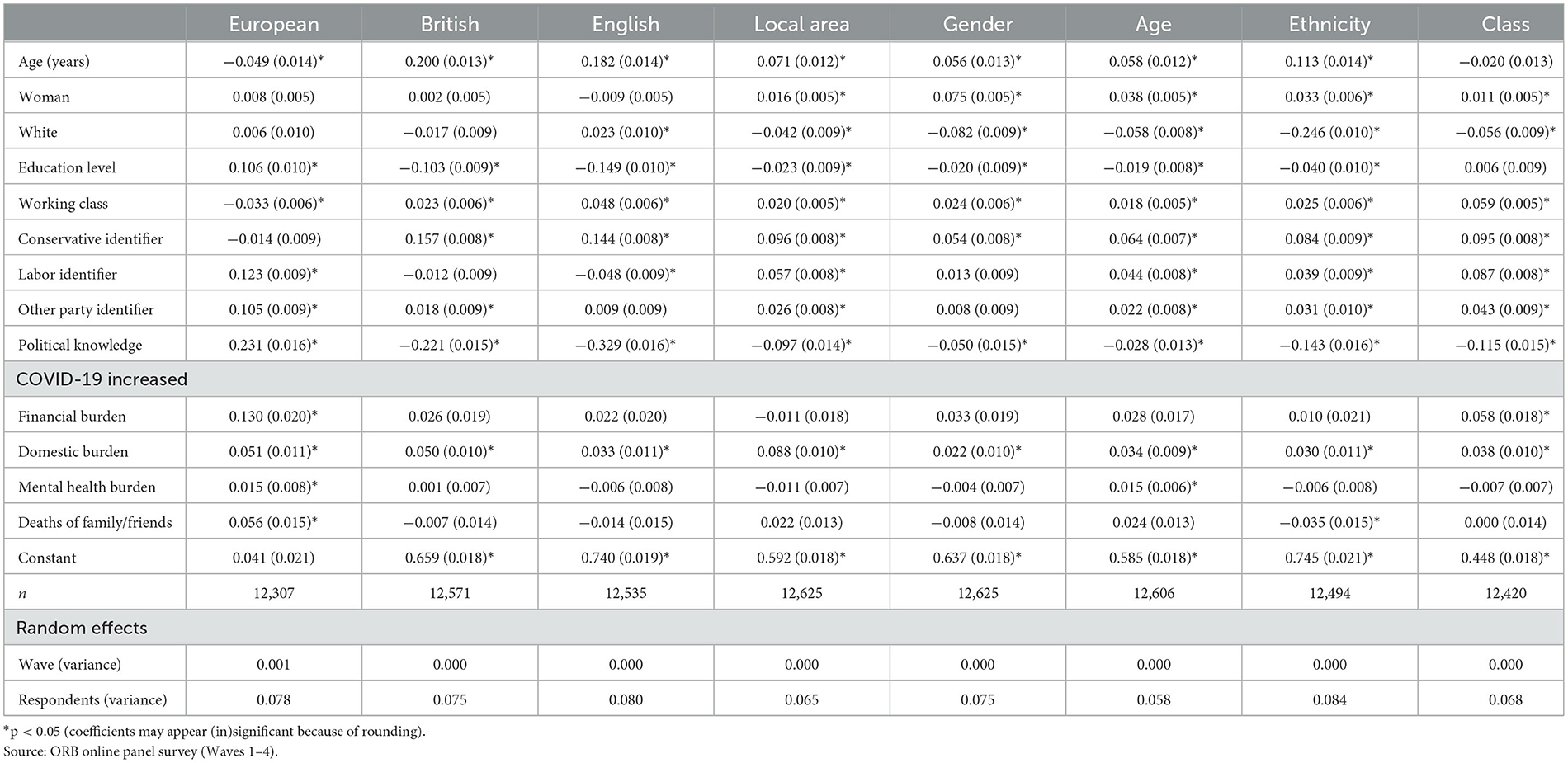

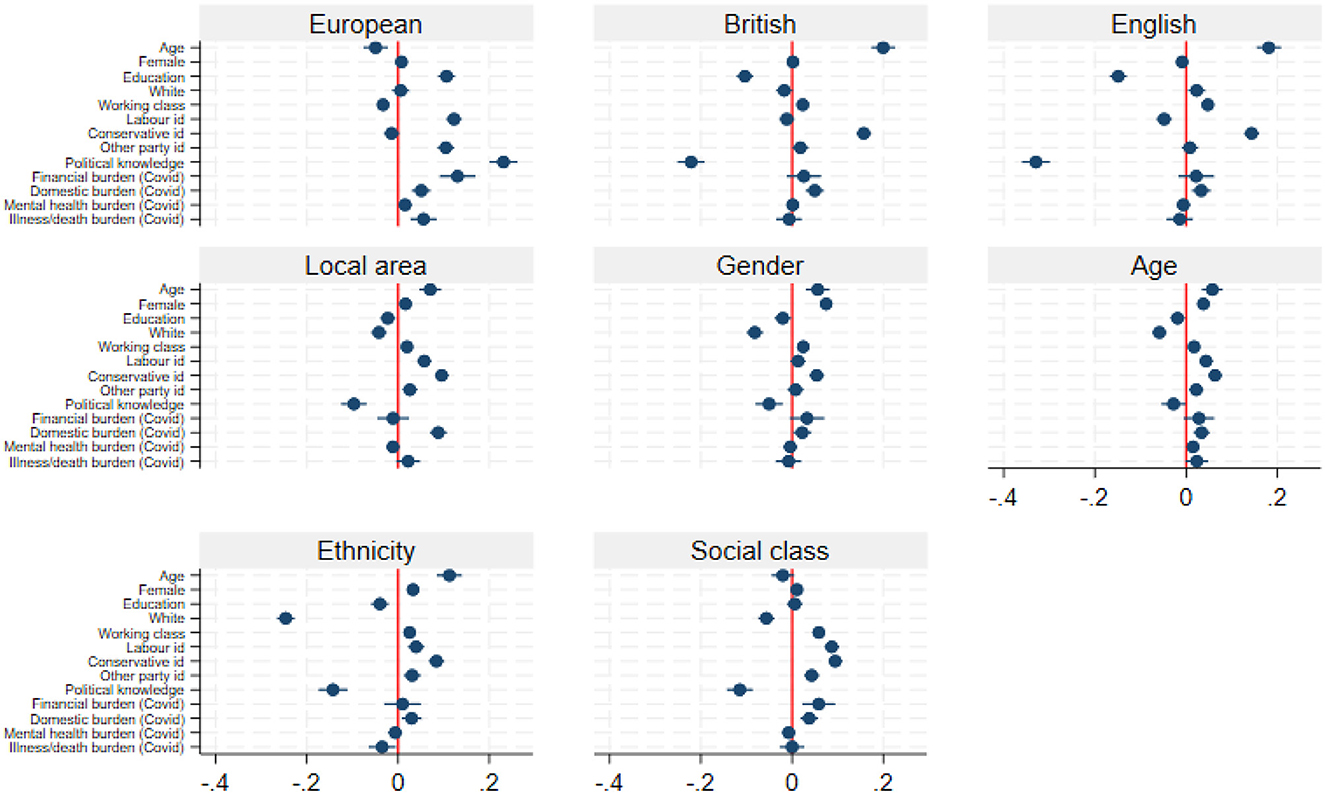

Because most of the observed individual-level variables are either invariant or limited in variance, we began by estimating models with interactions between each of these variables and the survey wave to capture any changes in their effects over time. These indicated an overall impact of the survey wave, i.e., the increases in the importance of identities we see in Figures 1, 2, but not that the slope of relationships between the explanatory variables and the importance of identities changed over time. The estimates we present in Table 1 are therefore random effects multilevel models grouped by individuals within wave.

Table 1 presents the estimates for variation in place-based identities in the first four columns of results and those for gender, age, ethnicity and social class in the next four columns. We examine their relationships with the individual-level characteristics of age, sex (a dummy variable for women), education, social class (a dummy variable for respondents who reported belonging to the working class), party identification (dummy variables for identifiers with the Labor, Conservative, or third parties, with identification with no party or don't know the excluded category) and political knowledge, and the four types of COVID experience. Figure 4 presents the estimates in coefficient plots.

Table 1 and Figure 4 show that we generally see more robust associations of identity with individual-level characteristics such as age, class and party identification than with direct experiences of COVID-19. Indeed, age, race, education, class, party identification and political knowledge are consistently associated with positive variation in the importance of identities. Older respondents are more likely to say that most of these identities are important to them, with the exception of Europeanness where they are more likely to say it is less important, and social class, for which age makes no difference. Perceiving oneself as working class and identifying with any party is also largely associated with greater importance of most identities, the exceptions again being national and European identities where we see a positive association of Labor identification and Europeanness and a negative association of Labor identification with Englishness, and the opposite for Conservative identification. Education and greater political knowledge, on the other hand, are consistently associated with lower importance attached to these group identities, with the exception of Europeanness for which they are associated with higher importance. The positive association of education and political knowledge with Europeanness, and their negative association with Britishness and Englishness, is consistent with the idea of an emerging division between well-educated cosmopolitans and less well educated particularists (Beramendi et al., 2015; Bornschier et al., 2021).

It is striking that Conservative party identification is associated with greater importance of most identities than Labor or third party identification. This may reflect a tendency for in-group norms to be particularly important for right-wing individuals, as shown in research on authoritarianism (Altemeyer, 1996; Jost et al., 2017). It also seems to reflect variation in the meanings attached to different identities. When we analyze gender identity separately among women and men, we find no differences for women in the influence of Labor and Conservative identification but large differences among men. For men, Labor identification has no association with the importance of gender identity, but Conservative identification is associated with enhanced importance, i.e., Conservative-identifying males are far more likely to say that being a man is important to their sense of who they are. We see similar kinds of patterns for class and ethnicity. Labor identification is more predictive of the importance of class identity among the working class and ethnic minority respondents, but Conservative identification is far more predictive than Labor identification of the importance of class identity among middle, upper class and white respondents. In other words, the influence of Conservative identity on non-place based identities in Table 1 appears due to the relative importance to Conservative partisans of male and majority group identities compared to other party identifiers.

Table 1 and Figure 4 also indicate that there was little additional influence of experiences of COVID-19 on the salience of identities. Direct experiences of increased financial strain, mental health problems and illness or deaths of family and friends show little evidence of causing individuals to rally round, or reject, group identities of nationalism, or identities with subgroups more or less affected by COVID such as those associated with ethnicity or social class. Figure 4 shows that most of the 95 percent confidence intervals of these estimates overlap zero and that even where they are statistically significant the size of the relationship is modest compared to individual-level characteristics such as age, partisanship, and education.

The exception is an increased domestic burden, which is the only variable in the entire analysis associated with an increase in the importance of all eight identities. It is worth repeating what an “increased domestic burden” from COVID-19 represents in the surveys: more responsibility for housework, childcare and home-schooling. It is not obvious why such increases would be associated with heightened importance of all eight identities. Variables with positive relationships with European identity, for example, generally have negative relationships with British and English identity, but an increased domestic burden as a result of COVID-19 is associated with greater importance of European, British, English, and local area identities. This suggests that direct experiences can also have general effects on “groupiness,” albeit they are relatively small.

Indeed, the stronger message of the analysis in Table 1 and Figure 4 is that experiences of societal challenges such as COVID-19 are less consequential for social identities than are individual-level characteristics such as age, partisanship, and education. Experiences of COVID-19 and how they were perceived were themselves, of course, likely to be affected by individual-level characteristics such as age (Risse et al., 1999). Regardless, our analysis indicates only small direct effects of such experiences once we control for individual-level characteristics. Where there is a consistent relationship for direct experiences—of an increased domestic burden—it is indicative of a broad, generally unidirectional, impact on multiple group identities rather than an alternative dynamic such as some identities coming to the foreground and others receding to the background.

Conclusion

This paper has examined social identities in the context of the challenges and contextual changes presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. We have answered three research questions using an original research design in which we asked respondents about the importance of multiple identities “to your sense of who you are” in five survey waves spread over 2 years. These identities were both place-based, e.g., European, British, and based on group characteristics such as gender and social class.

Our first question was about the relative importance of national and place-based identities vs. subgroup identities. Place-based identities such as national identity are often the focus of research on the relationships between identities and political attitudes and behavior, including during COVID-19 (Blank and Schmidt, 2003; Pehrson et al., 2009; Green et al., 2011; Chan et al., 2021; Henderson and Wyn Jones, 2022; Van Bavel et al., 2022). In addition, most research on social identity gauges one or two identities, precluding assessment of their relative importance in comparison to other group identities. We showed that British, English and local area identities were all considered important by respondents in the surveys but never as important as gender and age.

We then asked about change over time. There is some tension in previous research between notions of negative relationships between the importance of different identities, i.e., as the importance of some increase, the importance of others decrease, and notions of “nested” identities—particularly place-based—that may increase or decrease in importance together. We showed what we have described as “groupiness,” borrowing from Stenner (2005), in which contextual increases in the importance of one group identity are accompanied by increases in the importance of several others—Europeanness being the exception in the survey. In Tajfel's terms, the value and emotional significance attached to group membership appears more general than previously thought. This is not just confined to place-based identities but also to the other identities of age, gender, race/ethnicity, and social class that we gauged.

Our third question asked about the influences on social identities and the extent to which they are rooted in contextual factors—in this case direct experiences of COVID-19—rather than individual characteristics such as age and education. We found stronger and more consistent relationships between individual characteristics and the importance of identities, including of age, education, partisanship and political knowledge, than of direct experiences of COVID-19.

What are the implications of this analysis for the questions of identity in relation to the social, political and economic challenges in democratic states that are the subject of this special issue—including emerging infectious diseases, such as COVID-19, that are likely to become more common? First, it confirms arguments that social identities are changeable rather than stable under conditions of threat and uncertainty like COVID. The importance of the identities we examined increased by about a quarter to a third of a standard deviation, with the exception of Europeanness. This often represented change, e.g., age, race/ethnicity, from about the mid-point of the scale to more firmly saying the identity was “important.” These increases in importance appear to be less because group memberships change—most of the definitions of the groups we examine are fairly fixed—than because the meanings of those group memberships, which underpin the importance of social identities, change. Second, these changes among several social identities indicate that particular concerns about increases in national identity, such as increased Englishness, because they are seen to imply narrower or more exclusionary attitudes, need to be placed in a broader context. While we may discern meaning from such increases, national identity has been associated with pro-social behaviors during COVID-19. In addition, what does it mean if strengthened national identity is accompanied by increases in identity with several other groups? It could reflect a tightening of the bounds of in-group membership, signifying increased hostility toward out-group members that would be reflected in greater intolerance or prejudice. On the other hand, it could reflect a process that is more positive and less exclusive, in which increases in identities that cross-cut national identity, e.g., age, class or race/ethnicity, dilute the impact of increases in potentially exclusionary place-based identities such as Englishness. To shed further light on this aspect of social identities would require an examination of their impact on attitudes and preferences that is beyond this paper.16

While we assume that it was the pandemic that led to the increases in the importance of social identities we observed—it is hard to imagine an alternative cause—the dynamics we have shown need to be examined in different contexts to further our understanding of how such exogenous shocks affect different social identities and with what consequences. This leads us to reflect on some of the weaknesses of this paper. Although we have outlined the strengths of the research design in terms of the multiple group identities we gauged over a 2-year time span, the surveys took place in the single context of the COVID-19 pandemic. First, as mentioned above, it is possible that the pandemic was unique in priming a number of different identities such as national, regional, social class and age-based identities. In other contexts likely to produce changes in the strength of national identity, such as after a terrorist attack, the impact of the contextual change may not vary systematically by social class or age cohort. On the other hand, economic crises do tend to have different subgroup impacts, perhaps producing similar patterns of changing identities to those we found here. Second, we have examined a context in which there were increases in the strength of group identities. This implies that there could be circumstances in which there will be a general decrease in the strength of group identities, or circumstances in which the nested place-based identities we gauged become incompatible and negatively related (Medrano and Gutiérrez, 2001). We need to identify those circumstances and their consequences for attitudes and preferences. Third, our measure of social identity gets at importance but not at other aspects of social identity such as definitions of the group, perceptions of its homogeneity, and the sense of belonging. We do not know whether those other dimensions change also, or whether the changes in identities we show are confined to salience. Finally, the panel survey research design we used has the advantage of tracking the importance of identities over time but the disadvantage of respondent attrition. Different research designs, such as rolling cross-sections, although having their own weaknesses, are needed to see whether they replicate the dynamics we have found.

Even acknowledging the limitations of panel data, however, our analysis runs counter to arguments that national or place-based identities are most important to individuals. It also suggests that threats such as COVID-19 may enhance a general attachment to groups rather than leading to increased attachment to particular in-groups or to in-groups that are more exclusive. This indicates a need to reconsider how and why social identities change and with what consequences if we are to understand the social, political and economic challenges faced by contemporary democratic states.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Exeter Faculty of Human and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DS: Writing – original draft. SB: Writing – review & editing. LH: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The first three waves of the panel survey were funded from ESRC grant (ES/V006320), Identity, Inequality, and the Media in Brexit-COVID-19-Britain (PI: Katharine Tyler). The fourth and fifth waves of the panel survey were internally funded by the University of Exeter.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2023.1268573/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Other motivations have since been added to the theory, including inclusiveness and the need for certainty (Hogg, 2007; Leonardelli et al., 2010).

2. ^The opposite tends to be true for authoritarian regimes because centralization of power gives local government little power or authority and it is often associated with corruption (Tang and Huhe, 2016).

3. ^In other words, features of the pandemic such as isolation and social distancing, although physically increasing the distance from other group members, are psychologically affirming because everybody else (or large majorities) are engaging in the same behaviors in order to reduce the threat.

4. ^Reuters reported a higher than normal 75% of the British public using television and online media as sources of information in the first months of the pandemic https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/uk-covid-19-news-indicators-page-beta.

5. ^e.g., Beynon and Vassilev (2021).

6. ^e.g., Savage (2021).

7. ^e.g., White and Nafilyan (2020).

8. ^Approximately 85% of the United Kingdom's population lives in England.

9. ^This is similar question wording to the UK's Understanding Society and America's General Social Survey identity questions such as, “How important is being British/American to you?” but the wording is less awkward when asking about other identities such as local area or age. Doosje et al. (1998) include a similar statement referring to “an important part of how I see myself at this moment” on a 9-point scale of importance.

10. ^There are, of course, some differences in these groups in terms of membership that is fixed, such as age group, and membership of groups involving more choice, e.g., living in a particular area or region. However, authors such as Nagel (1995) show that even reported membership of seemingly fixed social groups changes with context and salience.

11. ^For age, 0 = 18 and 1 = 88.

12. ^We exclude “don't know” answers, which are never more than 6%. It makes no difference to any of our substantive conclusions if we include them as midpoints on the scales.

13. ^As an additional robustness check, we conducted four latent class analyses of changes in identities between waves, in order to examine further the possibility of different kinds of shifts among different groups of respondents. These analyses indicated three groups of more than 5% of respondents, with varying extents of change in all identities between waves: from negative changes in all identities (about 10%of respondents), to positive or zero changes between waves of a similar pattern to Figure 2 (about 80% of respondents), to larger positive changes in all identities (about 10% of respondents). In sum, there was not a group evincing increases in the importance of some identities and decreases in the importance of others. We also examined the possibility that the increases in the importance of identities we observe over time are an artifact of being asked about these identities several times rather than representing real change. We compared panel respondents at Waves 1 and 4 with a sample of fresh respondents recruited at Wave 4 (for different purposes to the topic of this paper). In Supplementary Table A5 we present and discuss this analysis, which indicates the increases in the importance of identities we observe were not just a consequence of being surveyed several times.

14. ^Before Stenner, Brubaker and Cooper had referred to “groupness” (Brubaker and Cooper, 2000).

15. ^We show between-subjects, lagged dependent variable estimates in Supplementary Tables A2–A4. The results are similar in terms of the size and statistical significance of relationships.

16. ^There has been a great deal of research on the relationships between social identities and political attitudes and behaviors during the COVID pandemic (e.g., Cárdenas et al., 2021; Chan et al., 2021; Chu et al., 2021; Stevenson et al., 2021; Bowe et al., 2022; Van Bavel et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022), but these too tend to be of a single identity, and if they gauge change at all it is generally over a shorter timespan than this paper.

References

Abrams, D., Lalot, F., and Hogg, M. A. (2021). Intergroup and intragroup dimensions of COVID-19: a social identity perspective on social fragmentation and unity. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 24, 201–209. doi: 10.1177/1368430220983440

Akerlof, K., Maibach, E. W., Fitzgerald, D. E., Cedeno, A. Y., and Neuman, A. (2013). Do people “personally experience” global warming, and if so how, and does it matter? Glob. Environ. Change 23, 81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.07.006

Bateson, R. (2012). Crime victimization and political participation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 106, 570–587. doi: 10.1017/S0003055412000299

Bechhofer, F., and McCrone, D. (2014). Changing claims in context: national identity revisited. Ethn. Racial Stud. 37, 1350–1370. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2012.676204

Beramendi, P., Häusermann, S., Kitschelt, H., and Kriesi, H., (eds). (2015). The Politics of Advanced Capitalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316163245

Beynon, B., and Vassilev, G. (2021). Personal and Economic Well-Being in Great Britain: January 2021. Office for National Statistics. Available online at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/bulletins/personalandeconomicwellbeingintheuk/january2021#savings-borrowing-and-affordability (accessed October 19, 2023).

Blank, T., and Schmidt, P. (2003). National identity in a United Germany: nationalism or patriotism? An empirical test with representative data. Polit. Psychol. 24, 289–312. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00329

Bond, R. (2017). Sub-state national identities among minority groups in Britain: a comparative analysis of 2011 census data: sub-state national identities among minority groups in Britain. Nations Natl. 23, 524–546. doi: 10.1111/nana.12253

Bornschier, S., Häusermann, S., Zollinger, D., and Colombo, C. (2021). How “Us” and “them” relates to voting behavior—social structure, social identities, and electoral choice. Comp. Polit. Stud. 54, 2087–2122. doi: 10.1177/0010414021997504

Bowe, M., Wakefield, J. R. H., Kellezi, B., Stevenson, C., McNamara, N., Jones, B. A., et al. (2022). The mental health benefits of community helping during crisis: coordinated helping, community identification and sense of unity during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Commun. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 32, 521–535. doi: 10.1002/casp.2520

Brewer, M., and Brown, R. (1998). “Intergroup relations,” in Handbook of Social Psychology, eds D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, and G. Lindzey (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill), 554–594.

Brubaker, R., and Cooper, F. (2000). Beyond “identity”. Theory Soc. 29, 1–47. doi: 10.1023/A:1007068714468

Butler, P. (2020). NHS Coronvirus Crisis Volunteers Frustrated at Lack of Tasks. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/03/nhs-coronavirus-crisis-volunteers-frustrated-at-lack-of-tasks?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other (accessed October 19, 2023).

Cárdenas, D., Orazani, N., Stevens, M., Cruwys, T., Platow, M., Zekulin, M., et al. (2021). United we stand, divided we fall: sociopolitical predictors of physical distancing and hand hygiene during the COVID-19 pandemic. Politic. Psychol. 42, 845–861. doi: 10.1111/pops.12772

Chan, H.-W., Wang, X., Zuo, S.-J., Chiu, C. P.-Y., Liu, L., Yiu, D. W., et al. (2021). War against COVID-19: how is national identification linked with the adoption of disease-preventive behaviors in China and the United States?' Polit. Psychol. 42, 767–793. doi: 10.1111/pops.12752

Chan, T. W., Henderson, M., Sironi, M., and Kawalerowicz, J. (2020). Understanding the social and cultural bases of brexit. Br. J. Sociol. 71, 830–851. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12790

Chen, C. Y.-C., Byrne, E., and Vélez, T. (2022). Impact of the 2020 pandemic of COVID-19 on families with school-aged children in the United States: roles of income level and race. J. Fam. Issues 43, 719–740. doi: 10.1177/0192513X21994153

Chu, J., Pink, S. L., and Willer, R. (2021). Religious identity cues increase vaccination intentions and trust in medical experts among American Christians. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118:e2106481118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2106481118

Collins, R. N., Mandel, D. R., and Schywiola, S. S. (2021). Political identity over personal impact: early U.S. reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 12, 607639. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.607639

Daszak, P., Keusch, G. T., Phelan, A. L., Johnson, C. K., and Osterholm, M. T. (2021). Infectious disease threats: a rebound to resilience. Health Aff. 40, 204–211. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01544

De Figueiredo, R. J. P., and Elkins, Z. (2003). Are patriots bigots? An inquiry into the vices of in-group pride. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 47, 171–188. doi: 10.1111/1540-5907.00012

Denters, B. (2002). Size and political trust: evidence from Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway and the United Kingdom. Environ. Plann. C Gov. Policy 20, 793–812. doi: 10.1068/c0225

Desmarais, C., Roy, M., Nguyen, M. T., Venkatesh, V., and Rousseau, C. (2023). The unsanitary other and racism during the pandemic: analysis of purity discourses on social media in India, France and United States of America during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anthropol. Med. 30, 31–47. doi: 10.1080/13648470.2023.2180259

Devine, D., Gaskell, J., Jennings, W., and Stoker, G. (2021). Trust and the coronavirus pandemic: what are the consequences of and for trust? An early review of the literature. Polit. Stud. Rev. 19, 274–285. doi: 10.1177/1478929920948684

Donnelly, M. (2021). Material interests, identity and linked fate in three countries. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 1119–1137. doi: 10.1017/S0007123419000589

Doosje, B., Branscombe, N., Spears, R., and Manstead, A. (1998). Guilty by association: when one's group has a negative history. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 75, 872–886. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.872

Dryhurst, S., Schneider, C. R., Kerr, J., Freeman, A. L. J., Recchia, G., van der Bless, A. M., et al. (2020). Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 23, 994–1006. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193

Eifert, B., Miguel, E., and Posner, D. (2010). Political competition and ethnic identification in Africa. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 54, 494–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00443.x

Goodwin, M., and Milazzo, C. (2017). Taking back control? Investigating the role of immigration in the 2016 vote for brexit. Br. J. Politics Int. Relat. 19, 450–464. doi: 10.1177/1369148117710799

Green, E. G. T., Sarrasin, O., Fasel, N., and Staerklé, C. (2011). Nationalism and patriotism as predictors of immigration attitudes in Switzerland: a municipality-level analysis: nationalism, patriotism and immigration. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 17, 369–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1662-6370.2011.02030.x

Hanson, K., O'Dwyer, E., Chaudhuri, S., Silva Souza, L. G., and Vandrevala, T. (2022). Mitigating the identity and health threat of COVID-19: perspectives of middle-class South Asians living in the UK. J. Health Psychol. 7, 2147–2160. doi: 10.1177/13591053211027626

Haslam, S. A. (2021). “Leadership,” in Together Apart: The Psychology of COVID-19, eds J. Jetten, S. D. Reicher, S. A. Haslam, and T. Cruwys (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications), 34–40.

Henderson, A., and Wyn Jones, R. (2022). Englishness: The Political Force Transforming Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198870784.001.0001

Hetherington, M., and Weiler, J. (2018). Prius or Pickup? How the Answers to Four Simple Questions Explain America's Great Divide. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Hinckley R. (forthcoming). Local existential threat, authoritarianism, and support for right-wing populism. Soc. Sci. J.

Ho, C. S., Yi Chee, C., and Cm Ho, R. (2020). Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) beyond paranoia and panic. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 49, 155–160. doi: 10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.202043

Hogg, M. (2007). “Uncertainty-identity theory,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, ed. M. P. Zanna (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 69–126. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(06)39002-8

Hogg, M. A., Terry, D. J., and White, K. M. (1995). A tale of two theories: a critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 58, 255. doi: 10.2307/2787127

Huddy, L. (2001). From social to political identity: a critical examination of social identity theory. Polit. Psychol. 22, 127–156. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00230

Huddy, L. (2013). “From group identity to political cohesion and commitment,” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, eds L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, and J. S. Levy (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 737–773. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199760107.013.0023

Huddy, L., and Del Ponte, A. (2019). “National identity, pride, and chauvinism—their origins and consequences for globalization attitudes,” in Liberal Nationalism and Its Critics, eds G. Gustavsson, and D. Miller (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 38–56. Available online at: https://academic.oup.com/book/40547/chapter/347911349 (accessed September 18, 2023).

Huo, Y. (2021). “Prejudice and discrimination,” in Together Apart: The Psychology of COVID-19, eds J. Jetten, S. D. Reicher, S. A. Haslam, and T. Cruwys (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications), 134–140.

Inglehart, R. (1977). Long term trends in mass support for european unification. Gov. Oppos. 12, 150–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.1977.tb00529.x

Ittefaq, M., Abwao, M., Baines, A., Belmas, G., Kamboh, S. A., and Figueroa, J. (2022). A pandemic of hate: social representations of COVID-19 in the media. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 22, 225–52. doi: 10.1111/asap.12300

Jetten, J. (2021). “Inequality,” in Together Apart: The Psychology of Covid-19, eds eds J. Jetten, S. D. Reicher, S. A. Haslam, and T. Cruwys (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications), 121–26.

Jost, J., Stern, C., Rule, N., and Sterling, J. (2017). The politics of fear: is there an ideological asymmetery in existential motivation? Soc. Cogn. 35, 324–353. doi: 10.1521/soco.2017.35.4.324

Kahn, K. B., and Money, E. E. L. (2022). (Un)masking threat: racial minorities experience race-based social identity threat wearing face masks during COVID-19. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 25, 871–891. doi: 10.1177/1368430221998781

Kam, C., and Ramos, J. (2008). Joining and leaving the rally: understanding the surge and decline in presidential approval following 9/11. Public Opin. Q. 72, 619–650. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfn055

Keys, C., Nanayakkara, G., Onyejekwe, C., Sah, R. K., and Wright, T. (2021). Health inequalities and ethnic vulnerabilities during COVID-19 in the UK: a reflection on the PHE reports. Fem. Leg. Stud. 29, 107–118. doi: 10.1007/s10691-020-09446-y

Lalot, F., Davies, B., and Abrams, D. (2020). Trust and Cohesion in Britain during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic across Place, Scale and Time. Canterbury: University of Kent. Report for British Academy.

Leonardelli, G., Pickett, C., and Brewer, M. (2010). “Optimal distinctiveness theory: a framework for social identity, social cognition, and intergroup relations,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, eds M. P. Zanna and J. M. Olson (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 63–114. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(10)43002-6

Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226524689.001.0001

McKay, L. (2019). “Left behind” people, or places? The role of local economies in perceived community representation. Elect. Stud. 60:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.010

Medrano, J. D., and Gutiérrez, P. (2001). Nested identities: national and European identity in Spain. Ethn. Racial Stud. 24, 753–778. doi: 10.1080/01419870120063963

Moreno, L. (2006). Scotland, Catalonia, Europeanization and the “Moreno Question”. Scott. Aff. 54, 1–21. doi: 10.3366/scot.2006.0002

Nagel, J. (1995). American indian ethnic renewal: politics and the resurgence of identity. Am. Sociol. Rev. 60, 947. doi: 10.2307/2096434

Pehrson, S., Vignoles, V. L., and Brown, R. (2009). National identification and anti-immigrant prejudice: individual and contextual effects of national definitions. Soc. Psychol. Q. 72, 24–38. doi: 10.1177/019027250907200104

Postmes, T., Haslam, S. A., and Jans, L. (2013). A single-item measure of social identification: reliability, validity, and utility. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 52, 597–617. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12006

Rahn, W., and Rudolph, T. (2002). “Trust in local governments,” in Understanding Public Opinion, eds B. Norrander and C. Wilcox (Washington, DC: CQ Press), 281–300.

Reynolds, K. J., Subasic, E., Batalha, L., and Jones, B. M. (2016). “From prejudice to social change: a social identity perspective,” in The Cambridge Handbook of the Psychology of Prejudice, eds C. G. Sibley, and F. K. Barlow (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 47–64. Available online at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/CBO9781316161579A013/type/book_part (accessed July 3, 2023).

Risse, T., Engelmann-Martin, D., Knope, H.-J., and Roscher, K. (1999). To euro or not to euro?: the EMU and identity politics in the european union. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 5, 147–187. doi: 10.1177/1354066199005002001

Rosenstone, S. J. (1982). Economic adversity and voter turnout. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 26, 25. doi: 10.2307/2110837

Rump, M., and Zwiener-Collins, N. (2021). What determines political trust during the COVID-19 crisis? The role of sociotropic and egotropic crisis impact. J. Elect. Public Opin. Parties 31(S1): 259–271. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2021.1924733

Savage, M. (2021). Housework Falls to Mothers Again after Covid Lockdown Respite. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/dec/19/housework-falls-to-mothers-again-after-covid-lockdown-respite (accessed October 19, 2023).

Sherif, M. (1954). Experimental Study of Positive and Negative Intergroup Attitudes between Experimentally Produced Groups: Robbers Cave Study. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma.

Sibley, C. G., Greaves, L. M., Satherley, N., Wilson, M. S., Overall, N. C., Lee, C. H. J., et al. (2020). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdown on trust, attitudes toward government, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 75, 618–630. doi: 10.1037/amp0000662

Sinnott, R. (2006). An evaluation of the measurement of national, subnational and supranational identity in crossnational surveys. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 18, 211–223. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edh116

Stenner, K. (2005). The Authoritarian Dynamic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511614712

Stevenson, C., Wakefield, J. R. H., Felsner, I., Drury, J., and Costa, S. (2021). Collectively coping with coronavirus: local community identification predicts giving support and lockdown adherence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 60, 1403–1418. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12457

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. (1979). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict,” in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds W. G. Austin, and S. Worchel (Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole), 33–47.

Tang, M., and Huhe, N. (2016). The variant effect of decentralization on trust in national and local governments in Asia. Polit. Stud. 64, 216–234. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12177

Tong, S. T., Stoycheff, E., and Mitra, R. (2022). Racism and resilience of pandemic proportions: online harassment of Asian Americans during COVID-19. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 50, 595–612. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2022.2141068

Turner, J. C. (1987). Rediscovering the Social Group: Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford : B. Blackwell.

Van Bavel, J. J., Cichocka, A., Capraro, V., Sjåstad, H., Nezlek, J. B., Pavlović, T., et al. (2022). National identity predicts public health support during a global pandemic. Nat. Commun. 13, 517. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27668-9

Wang, X., Yang, Z., Xin, Z., Wu, Y., and Qi, S. (2022). Community identity profiles and COVID-19 related community participation. J. Commun. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 32, 398–410. doi: 10.1002/casp.2568

Weiss, H. (2003). A cross-national comparison of nationalism in Austria, the Czech and Slovac Republics, Hungary, and Poland. Polit. Psychol. 24, 377–401. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00332

White, C., and Nafilyan, V. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by Ethnic Group, England and Wales: 2 March 2020 to 10 April 2020. Office for National Statistics. Available online at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/coronavirusrelateddeathsbyethnicgroupenglandandwales/2march2020to10april2020 (accessed October 19, 2023).

Keywords: social identities, COVID-19, national identity, panel data analysis, democratic challenges

Citation: Stevens D, Banducci S and Horvath L (2023) Identities in flux? National and other changing identities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1268573. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1268573

Received: 28 July 2023; Accepted: 22 November 2023;

Published: 12 December 2023.

Edited by:

David McKeever, University of the West of Scotland, United KingdomCopyright © 2023 Stevens, Banducci and Horvath. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniel Stevens, ZC5wLnN0ZXZlbnNAZXhldGVyLmFjLnVr

Daniel Stevens

Daniel Stevens Susan Banducci

Susan Banducci Laszlo Horvath

Laszlo Horvath