94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 24 October 2023

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1223274

This article is part of the Research TopicAgents of Political Socialization in the 21st CenturyView all 7 articles

Introduction: Why do cohorts differ in their attitudes toward sexual orientation and what is the role of societal values during formative years? We investigate whether discontinuities in the prevailing values of equality and tradition in a person's formative years impinge on their attitudes toward sexual orientation as adults.

Methods: We test this by integrating historical political data from the Manifesto Project Dataset with contemporary micro-data on attitudes toward sexual orientation from 10 rounds of the European Social Survey (2002-2020) across 13 cohorts in 13 European countries.

Results and discussion: Using hierarchical age-period-cohort analysis with synthetic age cohorts, we find if the value of equality is politically diffuse, it can have a socializing effect. We find that the individuals who came of age during a period when political values of equality were more dominant are more tolerant of gays and lesbians. On the other hand, we do not find any evidence that individuals who experience youth during a time of more traditional political values have more negative opinions about different sexual orientations. Overall, these findings suggest that cohorts adopt distinct patterns of attitudes toward gays and lesbians as a result of a collective process of socialization during their impressionable years.

In the last 30 years, attitudes toward different sexual orientations1 have rapidly become more tolerant around the world. Some attribute this to a bi-product of economic growth and the expansion of post-materialist values (Andersen and Fetner, 2008) and declining religiosity (Sherkat et al., 2011), increasing education levels in society (Loftus, 2001) and the media visibility of gays and lesbians (Schiappa et al., 2006).

There is clear evidence that younger people are more tolerant of gays and lesbians than older people (Halman and van Ingen, 2015; Dotti Sani and Quaranta, 2020), a pattern that is common regarding shifting social issues. For this reason, including age as a demographic variable in cross-sectional research without distinguishing the meaning of age from other temporal phenomena obscures important social dynamics in attitudes. Attitudinal differences between the old and the young are not necessarily due to aging, in other words, the process of becoming older. Rather, the age of a person holds different substantive meanings (Riley, 1973, 1987; Kertzer, 1983). In addition to their placement along the lifecycle, a person's age also indicates their birth year, which carries its social significance. Birth cohorts, individuals born around the same time, can experience different socializations through a unique sequence of events and circumstances which have long-lasting impacts on their socio-political attitudes (Inglehart, 1977).

There is an existing debate about whether this growing liberalization of attitudes toward gay and lesbian people is due to a period effect or a cohort effect. A period effect refers to an underlying general trend toward more tolerant attitudes for all of society which are often driven by events or institutional change. In the case of a period effect, a trend is observable if there is a consistent worsening or improvement of attitudes vis-à-vis a given issue. This can occur for two reasons: either because people change their opinions or because the composition of the population changes, such as through the mechanism of cohort replacement. Thus far, there is evidence of both period and cohort effects (Treas, 2002; Ruel and Campbell, 2006; Andersen and Fetner, 2008; Sherkat et al., 2011; Sheoran et al., 2012; Pampel, 2016). Baunach (2011) decomposes this trend and finds that while two-thirds of the changes in the United States are due to intracohort aging (individuals changing their views), one-third are due to a cohort effect.

Scholars have been more recently interested in explaining what appears to be a non-linear trend of attitudes across cohorts. Recent research shows a fluctuating or inconsistent trend of cohort effects, implying that this is not simply due solely to a period or aging effect. Younger cohorts tend to be less politically tolerant than baby boomers and what seems to be a general increase in approval of same-sex relationships may simply be an artifact of baby-boomers making up a larger portion of the general population (Schwadel and Garneau, 2014). In a recent study, Ekstam (2021) finds discontinuities in the pattern of adjacent cohorts and suggests that this is due to the effects of different political socialization of cohorts, who come of age in different formative contexts. At present, much of the existing attention in the socialization of attitudes toward same-sex relationships has been toward micro-socializing factors such as religion or education or macro-socializing factors such as legislation for same-sex relationships (for a discussion see Dotti Sani and Quaranta, 2020).

This article addresses the question of why cohorts differ in their attitudes toward gays and lesbians by investigating the role of contextual values during formative years. It is well established that ideas and values that are part of the zeitgeist of a cohort's youth have a formative impact on their worldviews throughout their adulthood (Ryder, 1965). According to the “impressionable years” argument, socio-political orientations are acquired during young adulthood. During youth, people experience a window of “plasticity” while they transition from adolescence to young adulthood as they engage for the first time with the social and political world around them (Marsh, 1971; Niemi and Sobieszek, 1977; Hanks, 1981; Sapiro, 2004; Neundorf et al., 2013). According to this view, a person's orientations are then crystallized and remain remarkably persistent as the person grows older. As a result, attitudes and values become more deeply entrenched and become more stable over the lifetime (Sears, 1981; Jennings and Gregory, 1984; Stoker and Jennings, 1995; Visser and Krosnick, 1998; Lewis-Beck, 2009). Following this reasoning, symbolic predispositions toward different sexual orientations formed in young adulthood are then solidified throughout the individual's life course. So, after the critical period of young adulthood, we would then not expect a person's biological age to be a factor in underlying their attitude and preferences.

While much emphasis has been placed on “landmark events” (in other words, exogenous shocks) and how they leave a mark on political socialization (see Sears and Valentino, 1997), there is now growing attention to more subtle shifts in the political values can have lasting effects (Grasso, 2014). For instance, in their study of attitudes toward immigration, Jeannet and Dražanová (2023), analyze the role of the political climate during formative years as a socializing agent in a person's political life. They define political climate as “the normative principles, beliefs, ideals, and values that prevail in the political zeitgeist” during a person's impressionable years [Jeannet and Dražanová, 2023, p. 6].

Similar to attitudes toward immigration, attitudes toward different sexual orientations are strongly related to human values. Values represent a person's fundamental priorities and as such underlie and motivate attitudes (Davidov et al., 2008). Schwartz (1994) offers a framework of certain basic values which are universal and generally explain the inevitable human tension between an openness to pursuing change and an inclination toward conservation. Kuntz et al. (2015) examine the relationship between attitudes toward gays and lesbians and Schwartz (1994)'s human values, finding a positive association between Schwartz's values of universalism and acceptance, while values of tradition lead to the opposite outcome. According to Schwartz (1994) tradition is “respect, commitment, and acceptance of the customs and ideas that traditional culture or religion provide” whereas universalism is “understanding, appreciation, tolerance and protection for the welfare of all people and nature” (Schwartz, 1994, p. 35). While Schwartz names his value concept “universalism”, it is clear from its definition that it is tapping into the importance of equality in society.

What is the mechanism between these values and attitudes toward gays and lesbians? The value of tradition underlies disapproval of different sexual orientations which are often perceived as a threat to “traditional family values” and accepting them would imply a perceived abandonment of tradition that such individuals hold dear. Therefore, individuals who hold tradition as a strong value can be more motivated to oppose the disruption of the status quo as sexual mores shift (Kuntz et al., 2015). On the other hand, universalism values, such as egalitarianism, foster the approval of different sexual orientations by prioritizing “tolerance and acceptance of those who differ from oneself, understanding rather than rejecting those with unconventional lifestyles”. Universalism values emphasize equal opportunities for all (Kuntz et al., 2015, p. 122).

While the work of Kuntz et al. (2015) examined the relationship between a person's contemporary values and their attitudes, our argument does not dispute this. Instead, this article offers a different investigation and contribution. We consider the role of the formative value context, during a person's coming-of-age period, and test whether this has an impact on the attitudes toward different sexual orientations when they are adults.

Based on existing research and the theoretical tenets of the Impressionable Years argument, we formulate the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Individuals belonging to an age- cohort that experienced a formative climate where the value of equality was heightened are significantly more likely to express tolerance for gays and lesbians than individuals belonging to other cohorts.

Hypothesis 2: Individuals belonging to an age- cohort that experienced a formative climate where the value of tradition was heightened are significantly less likely to express tolerance for gays and lesbians than individuals belonging to other cohorts.

Some scholars dispute the notion of “impressionable years”, instead positing a lifelong openness model to public opinion (Franklin and Jackson, 1983; Franklin, 1984). According to this view, opinions remain open even after youth and political socialization can occur even later in life, for instance, due to personal experiences. We choose not to derive competing hypotheses based on this theoretical perspective because in in our view, it is not applicable to the formation of attitudes toward sexual orientation. This is because such attitudes are symbolic political issues, as they are more ideological or affective in nature rather than economic (Sears, 1983). Symbolic political issues are highly stable over a lifetime and less affected by life experiences (Alwin and Krosnick, 1991; Jeannet, 2018; Peterson et al., 2020).

We apply the expectations of political socialization theory to test the above-formulated hypotheses during the years 2002–2020 in 13 European countries. Firstly, the findings offer an empirical contribution to the burgeoning scholarship on attitudes toward people of different sexual orientations and other stigmatized groups. Yet the findings are also useful for understanding the socializing agents in the formation of political tolerance. Political tolerance is a broader concept that refers to the willingness to “extend civil liberties to political outgroups” (Karpov, 2002, p. 267). This study chooses to focus on Europe for several reasons. The first is that most of the existing work has focused on social change in attitudes toward gays and lesbians in the United States (notable exceptions are Dotti Sani and Quaranta, 2022), particularly when it pertains to the study of cohort effects. Secondly, Europe offers a natural setting for a double-comparative design that cross-classifies cohorts and countries over time. This allows us to observe cohorts aging in different contexts, with different period effects.

The analysis relies on the European Social Survey (ESS), rounds 1 (2002) to 10 (2020). We use 13 countries that have participated in at least five rounds of the survey: Austria, Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, Denmark, Finland, France, Great Britain, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden.2 Following standard practice in cohort analysis, we group individuals into cohorts based on five-year birth intervals. We, therefore, have 14 cohorts and 206,906 respondents in total.

The dependent variable measures the extent to which respondents agree with the statement that “gay men and lesbians should be free to live their own life as they wish”. The response categories are ordinal and range from 1 (agree strongly) to 5 (disagree strongly). We recorded the variable so that higher numbers mean more positive attitudes.3 This survey item has been frequently used as an indicator of attitudes toward gays and lesbians in extant research (van den Akker et al., 2013; Abou-Chadi and Finnigan, 2019; Dotti Sani and Quaranta, 2020, 2022).

For our two independent variables, we rely on data from The Manifesto Project, a widely used data set that includes a coded content analysis of party manifestos since 1945. Using this data, we measure the two values of equality and tradition as the share of quasi-sentences calculated as a fraction of the overall number of allocated codes per manifesto (Volkens et al., 2018). We conceive of the principle of equality as a positive view of social justice and the need people to be treated fairly. “This includes references to topics such as special protection for underprivileged social groups, removal of class barriers, need for fair distribution of resources and the end of racial or sexual discrimination” (Volkens et al., 2018, p. 17). On the other hand, the principle of tradition is coded as positive or favorable mentions of traditional and/or religious moral values. “This includes references to topics such as prohibition, censorship and suppression of immorality and unseemly behavior, maintenance and stability of the traditional family as a value, and support for the role of religious institutions in state and society” (Volkens et al., 2018, p. 19).

Borrowing a similar approach by Jeannet and Dražanová (2023), we compute annual measures by country from the manifesto data. We do this by weighting the share of votes that the party has received in the country's last elections.4 As we are interested in the individual's formative political environment, rather than the environment at the time of the survey, we assign individuals the values of tradition and equality when cohorts were between the ages of 18 and 23 by averaging the five years of each cohort.

We also include a series of controls using the European Social Survey based on individual-level characteristics which have been shown to be associated with attitudes toward sexual orientation in prior research. Individuals who are older, less educated and male tend to hold more negative attitudes (Schwadel and Garneau, 2014; Halman and van Ingen, 2015). We control for religiosity since individuals who are more religious tend to oppose same-sex relationships (Adamczyk and Pitt, 2009), living in an urban/rural area (Jakobsson et al., 2013), socio-economic position (Anderson and Fetner) by perceived income difficulties (Andersen and Fetner, 2008) and left-right self-positioning (Baunach, 2012).

Empirical evidence also shows that attitudes toward sexual orientation depend on context (Adamczyk and Pitt, 2009) and can vary cross-nationally (Dotti Sani and Quaranta, 2020). We, therefore, control for policy regulations such as gay marriage or the possibility for registered partnership based on Waaldijk (2020) data tracking the years when either registered partnership or same-sex marriage were introduced at the cohort and period level within each country, the percentage of university-educated people at the cohort and period level within each country and the level of unemployment at the cohort and period level within the country (Inglehart, 2008).

Our empirical strategy employs hierarchical age-period-cohort regression analysis (HAPC) using repeated cross-sectional surveys (Zheng et al., 2011). HAPC analysis separates the three temporal phenomena of age, period (year of survey) and birth cohort (year of birth) effects using micro survey data (Yang and Land, 2013). It allows us to construct synthetic cohorts based on age groups where individuals are cross-classified by both country-period and country-cohort. By constructing cohorts, the age, period and cohort is no longer perfectly collinear. This is because one cannot derive the exact age of the respondent from the age and year, but only a range of possible ages. Similar approaches have been used in the study of cohort effects in public opinion (Smets and Neundorf, 2014; Gorodzeisky and Semyonov, 2018).

Following Jeannet and Dražanová (2023), we apply hierarchical three-level age-period-cohort models. In these models individuals are nested both within two second-level variables (country-cohort and country-period) as well as nested within countries since possible clustering at the country level might still occur.

The models also include random effects for cohorts and periods. We assume that while age is related to biological processes of aging, cohort and period effects are the result of external influences and are to be considered as macro-level variables (Yang, 2008).

where, within each country-cohort j, country-period k and country c, respondents' attitudes to sexual orientation (Y) are a function of their individual characteristics (vector X). β0j kc is the mean of attitudes of individuals in country-cohort j, country-period k, and country c, β1 is the level-1 fixed effects and eijkc is the random individual variation.

where Z is a vector of country-cohort characteristics and T is a vector of country-period characteristics, μ0jc is the residual random effect of country-cohort j, ν0kc is the residual random effect of country-period k. The level-3 model is:

where ω0c is the residual random effect of country c. In all three models (1), (2) and (3) μ0j, ν0k and ωoc are assumed normally distributed with mean 0 and variance τμ, τν and τω respectively.

We have grand-mean centered all continuous individual, country-cohort and country-period level variables.

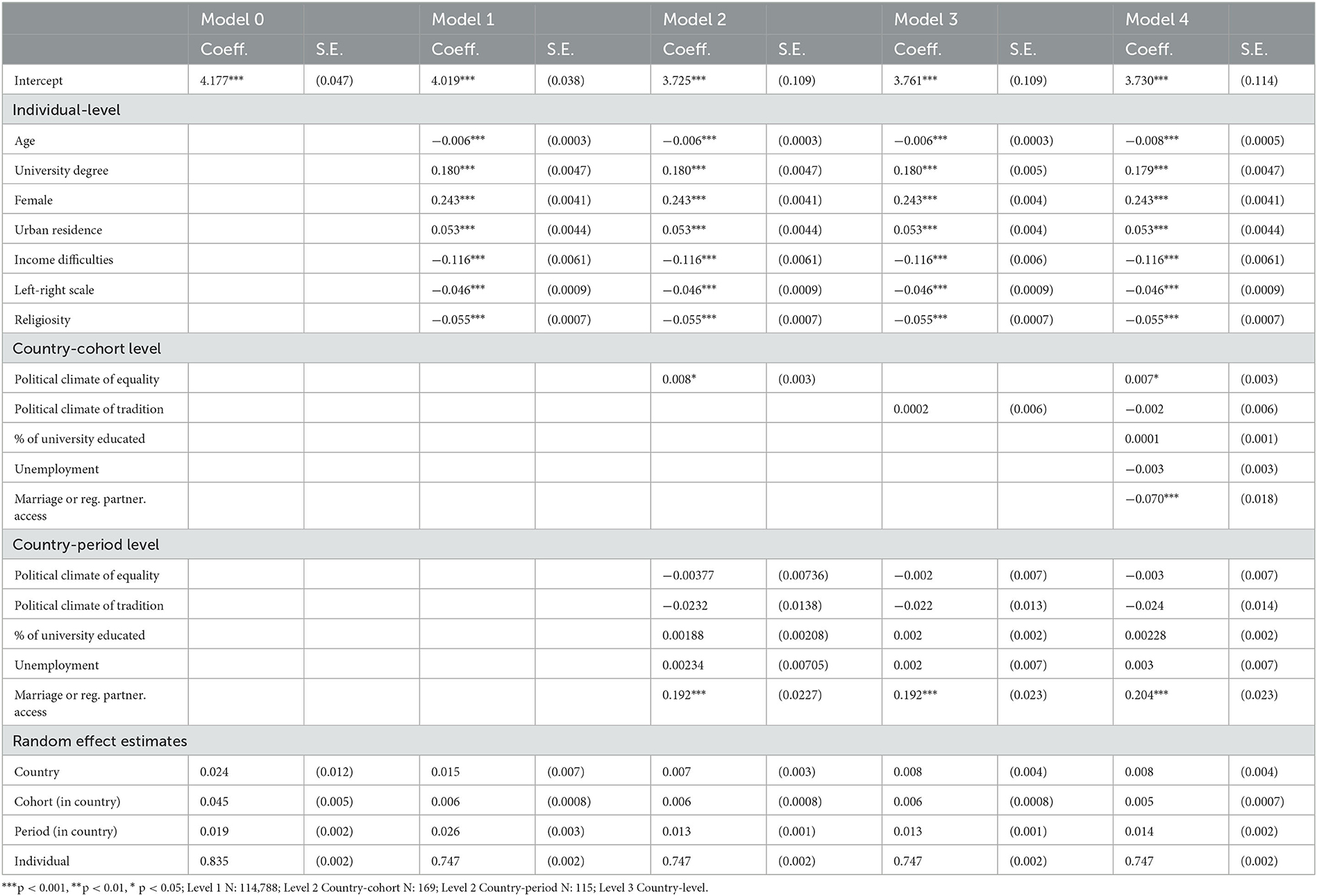

Table 1 shows as Model 0 a so-called null model, in order to partition the variance of our dependent variable of interest across the three levels. This model provides information on the variance components of attitudes toward sexual orientation at each level of analysis (Level 1—individual, Level 2—country-cohort, Level—country-period and Level 3—country). The null model includes only an intercept, country-cohort random effects, country-period random effects, country random effects and an individual-level residual error term. The overall mean attitude toward sexual orientation across all countries, all country-cohorts, all country-period and all respondents is estimated to be 4.17 on a scale of 1–5. Therefore, generally, attitudes toward gays and lesbians across an average individual are quite positive.

Table 1. Results of a hierarchical multilevel cross-classified model explaining cohort-differences in attitudes to different sexual orientation across 13 countries.

The null model simply decomposes the total variance in attitudes to sexual orientation into separate country-cohort, country-period, country and individual variance components.

Having fitted the model, we can predict Best Linear Unbiased Predictions (BLUPs). We predict BLUPS for the country-cohort and country-period random effects from the unconditional model by country together with their associated standard errors. Figure 1 shows the country-cohort random effects for each country separately. As can be seen from the figure, there is variation between cohorts in their attitudes to gays and lesbians. In most countries, the general trend is that younger cohorts tend to have more positive attitudes toward different sexual orientations, but it is not necessarily always true. Figure 2, on the other hand, shows the country-period random effects. The figure shows that aggregate attitudes within a country tend to vary a lot based on the year of the survey. In most countries, nevertheless, the trend is positive, meaning that as time passes respondents tend to be more positive toward gays and lesbians.

Model 1 in Table 1 adds individual-level control variables as well as random coefficients for country-cohorts, country-period and country. Consistent with most previous studies, in general, respondents who are younger, female, and live in an urban settlement are more positive toward gays and lesbians. Respondents who face income difficulties, consider themselves to be toward the right-wing political orientation and are more religious are significantly more likely to be negative toward gays and lesbians. Adding individual-level variables to Model 0 has led to lowering the percentage of unexplained variance not only at the individual level but also at the cohort level (Table 1). This is due to certain individual-level variables likely explaining some of the differences in attitudes toward gays and lesbians across cohorts.

We have hypothesized that individuals who experienced a political climate dominated by the value of equality during their formative years are significantly more likely to express support for different sexual orientations (Hypothesis 1), while individuals who came of age during a climate dominated by traditionalist values are significantly less likely to express support for same-sex orientations (Hypothesis 2). Models 2 and 3 in Table 1 test these propositions while also controlling for country-period (political climate of equality, political climate of tradition, percentage of university-educated individuals within a country, period level unemployment and access to either registered partnership of marriage for same-sex couples) and individual level factors from Model 1.

Models 2 and 3 in Table 1 introduce our main variables of interest—cohort-level value of equality and cohort-level value of tradition. Model 2 shows that cohorts coming of age in times when the political climate in their country emphasized the value of equality are significantly more likely to hold positive attitudes toward gays and lesbians. Model 3 in Table 1 includes a measure of the principle of tradition in the political climate at the country-cohort level, while also controlling for individual as well as period-level factors. The non-significant effect of the principle of tradition does not confirm our hypothesis H2. It appears that cohorts growing up in times when the political climate in their country emphasized the value of tradition are not significantly likely to hold negative attitudes toward different sexual orientations.

Finally, Model 4 includes all independent variables at the individual level and the country-period level. Our results for the principle of equality measured at the country-cohort level remain significant even after controlling for all other factors at different levels. The results support our argument that coming of age during a political climate of equality is consequential for the future political attitudes of these cohorts. Those respondents who were socialized into a political climate that emphasized equality are significantly more likely to hold positive attitudes toward gays and lesbians compared to those who came of age in different political climates. Moreover, as the median age in the sample is 46 years old, this effect appears to be long-lasting. Interestingly, neither the political climate of tradition significantly negatively nor the political climate of equality significantly positively influence attitudes toward gays and lesbians at the country-period level in any of the models.5

To what extent do people's current attitudes toward different sexual orientations reflect the values of the times they grew up in? Our results confirm previous studies showing that there is a cohort effect in attitudes toward same-sex relationships. We came to these conclusions by employing a double comparative design of cohorts in 13 countries (169 country-cohorts) that analyzes both contemporary micro-attitudinal data and historical macro-contextual data. Using hierarchical modeling in an age-period-cohort framework, we examined why attitudes toward gays and lesbians differ across age groups.

We have argued that one reason for this can be found in the macro-level socialization process which occurs during a person's youth. Overall, these findings suggest that cohorts adopt distinct patterns of attitudes toward different sexual orientations as a result of a collective process of political socialization during their impressionable years. We find that the individuals who came of age during a period when political values of equality were more dominant are more tolerant of other sexual orientations later in life. On the other hand, we do not find any evidence that individuals who experience youth during a time of more traditional political values have more negative opinions about gays and lesbians.

Our findings imply that if the value of equality is politically diffuse, it can have a socializing effect. As others such as Grasso et al. (2019) have argued, values that are dominant in the formative years can have a trickle-down socializing effect. Unlike primary socializing agents like the family or school, the formative political climate is an impersonal socializing agent that delivers mass messages about societal norms and principles. As such, the formative political climate can impress norms and values on younger people who come of age around the same time, regardless of socio-economic background.

The study has several limitations to consider. The first of these is the limited time span of our attitudinal microdata. The first round of the European Social Survey was in 2002 and the last release was in 2020. This allows us to observe how cohorts age for 18 years. However, our study is not able to investigate how political values in a formative climate maturate over three or four decades. Taking this into consideration we remain circumspect about our conclusions and abstain from generalizing about generations or inter-generational change and refer only to cohort change. Another limitation is not having sufficient historical control variables for unobservable macro-cultural aspects of society during an individual's formative years.

We hope that the latter limitation can be overcome in future research. For instance, it would be worthwhile to examine how media stereotypes during a person's youth could also have a socializing effect. This line of research could be further motivated by the fact that voters often rely on stereotypes to generate their opinions by using them as heuristics. Influential individuals, such as openly gay politicians or celebrities during youth might also exert an influence. Other extensions of this study could explore whether the diffusion of equality in society during youth also has an impact on adult attitudes toward other potentially stigmatized groups such as ethnic minorities, transgender individuals, or disabled persons.

Our study does cannot assure that shifts in preferences for LGBT+ inclusion are genuine (Turnbull-Dugarte and Lopez Ortega, 2023). There are still widespread conspiracy beliefs relating to LGBTQ+ people (Salvati et al., 2023) as well as recent anti-LGBT policies and rhetoric across Europe. The importance of formative political context that we have demonstrated in our study thus implies that current events and political rhetoric are consequential for attitudes toward gays and lesbians in the future.

Cohort studies are important for understanding the temporal aspects of attitudes regarding different sexual orientations. If trends continue, we can expect increasing tolerance for sex-sex relationships in Europe. However, our study implies that if political values of equality today become less popular, this can harm political tolerance tomorrow. This could have serious consequences for stigmatized groups and these reasons we urge social scientists to continue to study the socialization process in young cohorts.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/IQFCFE.

A-MJ wrote the introduction and discussion. LD conducted the empirical analysis and wrote the results section. A-MJ and LD contributed to data collection and research design. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2023.1223274/full#supplementary-material

1. ^We avoid the use of the terms homosexuality and homosexuals to be consistent with the current inclusive language about people belonging to sexual minorities following the most recent APA guidelines: https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/bias-free-language/sexual-orientation.

2. ^Our selection of countries is restricted to European countries which were participatory democracies during the formative years of the oldest cohort in the sample (1949–1953).

3. ^We treat the variable as continuous in our analysis.

4. ^In the case of mixed electoral systems with a proportional and majoritarian component, we follow Jeannet and Dražanová (2023). We use the vote share in the proportional component. In the case of an electoral coalition where programs for all members of the coalition and the coalition were coded, we set the vote share to zero for the coalition program so that the sum of the share is not higher than 100 percent.

5. ^In the existing literature, the empirical link between same sex legislation and tolerance for sex-same relationships is more tenuous than one might expect. For instance, Redman (2018) finds that the passing of same sex legislation intensifies support amongst individuals who were already tolerant but does not “re-educate” individuals or make acceptance more widespread.

Abou-Chadi, T., and Finnigan, R. (2019). Rights for same-sex couples and public attitudes toward gays and lesbians in Europe. Comp. Polit. Stud. 52, 868–895. doi: 10.1177/0010414018797947

Adamczyk, A., and Pitt, C. (2009). Shaping attitudes about homosexuality: the role of religion and cultural context. Soc. Sci. Res. 38, 338–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.01.002

Alwin, D. F., and Krosnick, J. A. (1991). Aging, cohorts, and the stability of sociopolitical orientations over the life span. Am. J. Sociol. 97, 169–195. doi: 10.1086/229744

Andersen, R., and Fetner, T. (2008). Economic inequality and intolerance: attitudes toward homosexuality in 35 democracies. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 52, 942–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00352.x

Baunach, D. M. (2011). Decomposing trends in attitudes toward gay marriage, 1988–2006*. Soc. Sci. Q. 92, 346–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2011.00772.x

Baunach, D. M. (2012). Changing same-sex marriage attitudes in America from 1988 through 2010. Public Opin. Q. 76, 364–378. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfs022

Davidov, E., Meuleman, B., Billiet, J., and Schmidt, S. (2008). Values and support for immigration: a cross-country comparison. Eur. Soc. Rev. 24, 583–599. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcn020

Dotti Sani, G. M., and Quaranta, M. (2020). Let them be, not adopt: general attitudes towards gays and lesbians and specific attitudes towards adoption by same-sex couples in 22 European Countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 150, 351–373. doi: 10.1007/s11205-020-02291-1

Dotti Sani, G. M., and Quaranta, M. (2022). Mapping changes in attitudes towards gays and lesbians in Europe: an application of diffusion theory. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 38, 124–137. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcab032

Ekstam, D. (2021). The liberalization of American attitudes to homosexuality and the impact of age, period, and cohort effects. Soc. Forc. 100, 905–929. doi: 10.1093/sf/soaa131

Franklin, C. H. (1984). Issue preferences, socialization, and the evolution of party identification. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 28, 459–478. doi: 10.2307/2110900

Franklin, C. H., and Jackson, J. E. (1983). The dynamics of party identification. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 77, 957–973. doi: 10.2307/1957569

Gorodzeisky, A., and Semyonov, M. (2018). Competitive threat and temporal change in anti-immigrant sentiment: insights from a hierarchical age-period-cohort model. Soc. Sci. Res. 73, 31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.03.013

Grasso, M. T. (2014). Age, period and cohort analysis in a comparative context: political generations and political participation repertoires in Western Europe. Elect. Stud. 33, 63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2013.06.003

Grasso, M. T., Farral, S., Gray, E., Hay, C., and Jennings, W. (2019). Thatcher's children, blair's babies, political socialization and trickle-down value change: an age, period and cohort analysis. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 49, 17–36. doi: 10.1017/S0007123416000375

Halman, L., and van Ingen, E. (2015). Secularization and changing moral views: european trends in church attendance and views on homosexuality, divorce, abortion, and euthanasia. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 31, 616–627. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcv064

Hanks, M. (1981). Youth, voluntary associations and political socialization. Soc. Forces 60, 211–223. doi: 10.2307/2577941

Inglehart, R. (1977). The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics. Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, R. (2008). Changing values among western publics from 1970 to 2006. West Eur. Polit. 31, 130–146. doi: 10.1080/01402380701834747

Jakobsson, N., Kotsadam, A., and Jakobsson, S. S. (2013). Attitudes toward same-sex marriage: the case of Scandinavia. J. Homosex. 60, 1349–1360. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2013.806191

Jeannet, A.-M. (2018). Revisiting the labor market competition hypothesis in a comparative perspective: does retirement affect opinion about immigration? Res. Pol. 5, 205316801878450. doi: 10.1177/2053168018784503

Jeannet, A.-M., and Dražanová, L. (2023). Blame it on my youth: the origins of attitudes towards immigration. Acta Politca. doi: 10.1057/s41269-023-00314-6

Jennings, M. K., and Gregory, B. M. (1984). Partisan orientations over the long haul: results from the three-wave political socialization panel study. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 78, 1000–1018. doi: 10.2307/1955804

Karpov, V. (2002). Religiosity and tolerance in the United States and Poland. J. Sci. Study Religion 41, 267–288. doi: 10.1111/1468-5906.00116

Kertzer, D. I. (1983). Generation as a sociological problem. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 9, 125–149. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.09.080183.001013

Kuntz, A., Davidov, E., Schwartz, S. H., and Schmidt, P. (2015). Human values, legal regulation, and approval of homosexuality in europe: a cross-country comparison. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 45, 120–134. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2068

Lewis-Beck, M. S. (2009). The American Voter Revisited. University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.92266

Loftus, J. (2001). America's liberalization in attitudes toward homosexuality, 1973 to 1998. Am. Sociol. Rev. 66, 762–782. doi: 10.1177/000312240106600507

Marsh, D. (1971). Political socialization: the implicit assumptions questioned. Brit. J. Polit. Sci. 1, 453–465. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400009248

Neundorf, A., Smets, K., and Garcia Albacete, G. M. (2013). Homemade citizens: the development of political interest during adolescence and young adulthood. Acta Polit. 48, 92–116. doi: 10.1057/ap.2012.23

Niemi, R. G., and Sobieszek, B. I. (1977). Political socialization. Annu. Rev. Soc. 3, 209–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.03.080177.001233

Pampel, F. C. (2016). Cohort changes in the social distribution of tolerant sexual attitudes. Social Forces 95, 753–777. doi: 10.1093/sf/sow069

Peterson, J. C., Smith, K. B., and Hibbing, J. R. (2020). Do people really become more conservative as they age? J. Polit. 82, 600–611. doi: 10.1086/706889

Redman, S. M. (2018). Effects of same-sex legislation on attitudes toward homosexuality. Polit. Res. Q. 71, 628–641. doi: 10.1177/1065912917753077

Riley, M. W. (1973). Aging and cohort succession: interpretations and misinterpretations. Public Opin. Q. 37, 35–49. doi: 10.1086/268058

Riley, M. W. (1987). On the significance of age in sociology. Am. Sociol. Rev. 52, 1–14. doi: 10.2307/2095388

Ruel, E., and Campbell, R. T. (2006). Homophobia and HIV/AIDS: attitude change in the face of an epidemic. Soc. Forces 84, 2167–2178. doi: 10.1353/sof.2006.0110

Ryder, N. B. (1965). The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. Am. Sociol. Rev. 30, 843–861. doi: 10.2307/2090964

Salvati, M., Pellegrini, V., De Cristofaro, V., and Giacomantonio, M. (2023). What is hiding behind the rainbow plot? The gender ideology and LGBTQ+ lobby conspiracies (GILC) scale. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 00, 1–24. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12678

Sapiro, V. (2004). NOT YOUR PARENTS' POLITICAL SOCIALIZATION: introduction for a new generation. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 7, 1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.7.012003.104840

Schiappa, E., Gregg, P. B., and Hewes, D. E. (2006). Can one TV show make a difference? A will and grace and the parasocial contact hypothesis. J. Homosex. 51, 15–37. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n04_02

Schwadel, P., and Garneau, C. R. H. (2014). An Age-Period-Cohort Analysis of Political Tolerance in the United States. Sociol. Q. 55, 421–452. doi: 10.1111/tsq.12058

Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? J. Soc. Issues 50, 19–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb01196.x

Sears, D. O. (1981). “Life-stage effects on attitude change, especially amoung the elderly,” in Aging: Social Change, eds S. B. Kiesler, J. N. Morgan, and V. K. Oppenheimer (New York, NY: Academic Press), 631.

Sears, D. O. (1983). The persistence of early political predispositions: The roles of attitude object and life stage. Rev. Person. Soc. Psychol. 4, 79–116.

Sears, D. O., and Valentino, N. A. (1997). Politics matters: political events as catalysts for preadult socialization. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 91, 45–65.

Sheoran, A. S., Pina-Mimbela, R., Keleher, A., Girouard, D., and Tzipori, S. (2012). Growing support for gay and lesbian equality since (1990). J. Homosexual. 59, 1307–1326. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2012.720540

Sherkat, D. E., Powell-Williams, M., Maddox, G., and de Vries, K. M. (2011). Religion, politics, and support for same-sex marriage in the United States, 1988–2008. Soc. Sci. Res. 40, 167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.08.009

Smets, K., and Neundorf, A. (2014). The hierarchies of age-period-cohort research: Political context and the development of generational turnout patterns. Elect. Stud. 33, 41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2013.06.009

Stoker, L., and Jennings, M. K. (1995). Life-cycle transitions and political participation: the case of marriage. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 89, 421–433. doi: 10.2307/2082435

Treas, J. (2002). How cohorts, education, and ideology shaped a new sexual revolution on American attitudes toward nonmarital sex, 1972–1998. Soc. Perspect. 45, 267–283. doi: 10.1525/sop.2002.45.3.267

Turnbull-Dugarte, S., and Lopez Ortega, A. (2023). Instrumentally inclusive: the political psychology of homonationalism. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1–19. doi: 10.1017/S0003055423000849

van den Akker, H., Van der ploeg, R., and Scheepers, P. (2013). Disapproval of homosexuality: comparative research on individual and national determinants of disapproval of homosexuality in 20 European countries. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 25, 64–86. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edr058

Visser, P. S., and Krosnick, J. A. (1998). Development of attitude strength over the life cycle: surge and decline. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 75, 1389–1410. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.6.1389

Volkens, A., Werner, K., Pola, L., Theres, M., Nicolas, M., Sven, R., et al. (2018). The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). doi: 10.25522/manifesto.mpds.2018b

Waaldijk, K. (2020). “What first, what later? Patterns in the legal recognition of same-sex partners in European Countries” In: Same-Sex Families and Legal Recognition in Europe. European Studies of Population 24. Ed. M. Digoix (Berlin: Springer).

Yang, Y. (2008). Social inequalities in happiness in the United States, 1972 to 2004: an age-period-cohort analysis. Am. Sociol. Rev. 73, 204–226.

Yang, Y., and Land, K. C. (2013). Age-Period-Cohort Analysis: New Models, Methods, and Empirical Applications. CRC Press.

Keywords: attitudes toward sexual orientation, political socialization, values, age cohort analysis, Europe

Citation: Jeannet A-M and Dražanová L (2023) Cohort differences in attitudes toward sexual orientation: the formative political climate as a socializing agent. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1223274. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1223274

Received: 15 May 2023; Accepted: 27 September 2023;

Published: 24 October 2023.

Edited by:

Julian Borba, Federal University of Santa Catarina, BrazilReviewed by:

Naiara Alcantara, Federal University of Pará, BrazilCopyright © 2023 Jeannet and Dražanová. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anne-Marie Jeannet, YW5uZS1tYXJpZS5qZWFubmV0QHVuaW1pLml0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.