- 1Institute on Comparative Regional Integration Studies (UNU-CRIS), United Nations University, Bruges, Belgium

- 2Neoma Business School, Rouen, France

- 3Centre for International Studies and Development, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland

Even though the UN interacts with regions and regionalism, a systematic analysis of the development of the regional dimension within their bodies is still needed. Traditional categories identifying simply electoral or operational roles for regions fall short in accounting for their multi-layered and increasing impact. Aiming at formulating a new typology and research agenda in this area, the authors approached the issue inductively. First, they provided a historical mapping of the regional manifestations in the framework of the UN and UN-regional organization interactions. Second, they analyzed relevant debates for the UN on peace, security, and sustainability through the lens of the regional dimension. What emerges is that, though vaguely defined and seriously fragmented, regions are largely used as electoral bodies, socio-economic areas, and statistical categories by the UN, that follow historical, cultural, and political rather than purely geographical criteria in their shaping. Besides, in the last 20 years, regions have become crucial for peacekeeping and conflict resolution in specific areas, as well as they are paramount to the implementation of global sustainability goals. All in all, the inductive approach has outlined three dimensions of UN regionalism: regions' political and operational roles; institutionalized vs. non-institutionalized groupings; and their formal vs. informal status. Finally, the authors suggest that strengthening partnerships between the UN and regional entities should be a milestone for a new era of networked and multi-layered multilateralism, while the harmonization of statistical regions is desirable at the operational level.

1. Introduction

What is the place of regions in the United Nations system? The end of World War II called for a new stage for multilateralism as the League of Nations clearly failed to manage international threats. Initially, a “new” form of multilateralism was built, with de facto leading roles for the United States (US) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Yet, at the same time, a new partnership between the United Nations (UN) and regional organizations came into existence.

This partnership, established in Chapter VIII of the UN Charter, had to coexist with the UN's Universalist approach; the latter, favored by the US and reflected in the original proposals, advocated a strong universal organization and left little room for regional action (Hilderbrand, 1990, p. 163–170). The regionalist approach, promoted especially by Latin American and Arab States, tried to achieve priority for regional organizations with respect to the settlement of disputes while denying the UN Security Council (UNSC) exclusive authority for the maintenance of international peace and security. Regionalist concern was further strengthened because of the time required for concerted action and of the possibility that the UNSC itself might prove ineffective at dealing with the threats to peace and security. The UN Charter presents some ambiguities resulting from a compromise between these two competing approaches (Sutterlin, 1995, p. 93). The ambiguity is patent when it comes to the lack of definition of regional organization in the UN Charter; it allows, however, a broad interpretation of Chapter VIII and retains flexibility.

The collaboration between the UN and regional organizations was reinvigorated after the end of the bipolar system of the Cold War and the Secretary-General's call for further UN-regional organizational cooperation in An Agenda for Peace (UNGA, 1992). The new global peace and security architecture relied on burden-sharing and on the principle of subsidiarity, with a horizontal approach between the UN and regional groups. Despite this new policy to deal with global peace and security, the primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security is conferred on the UNSC, keeping a hierarchical system in which regional organizations are the subsidiary parties (De Coning, 2017, p. 145–160). Although the UN reform in 2018 aimed at reinvigorating the regional dimension in the UN development and peace and security pillars, it was only a point of departure for a comprehensive reform that would fully reflect the real situation of the current world order in all UN bodies. Ever since its genesis, a regional approach has been actively deployed as an integral part of the UN framework. Moreover, since the signing of the UN Charter, regional organizations multiplied and became more relevant worldwide, while at the same time interacting with de facto patterns of regionalisation of the globe in different spheres (economic, political, cultural). This contextual development has, in turn, contributed to further strengthening the regional dimension of the UN construct in various policy areas to varied degrees.

Despite its significance, the development of regional dimension in the UN system has not been extensively studied. Actually, a few strands in the literature focus on certain specific aspects of regional dimension in the UN and its work, like UNSC reform, peacekeeping operations, UN operational coherence (De Lombaerde et al., 2012), as well as UN's cooperation with regional organizations, especially that with the European Union and African Union. Still, a more systematic analysis is needed, not only of UN-regional organizational interactions, but also of the relevant ontology(-ies) that are being used within the UN and in its external relations.

Our approach is inductive. We will start from a thorough description of how the regional dimension manifests itself in all its variations in the UN context. Subsequently, we will theorize the regional ontology in the UN context and the UN-regional organization nexus. Our ambition is to contribute to formulating a new typology and research agenda in this area.

The paper is organized as follows. Section two provides a historically framed mapping of the manifestations of the regional dimension in the framework of the UN and UN-regional organization interactions. Section three analyses the regional dimensions of important debates in the UN context, related to peace and security, on the one hand, and sustainable development, on the other. Following the inductive logic, section four extracts more general findings - related to the explicit or implicit conceptualization of regions in the UN context - from the rich empirical material collected in the preceding sections. It includes a critical discussion of the UN's consistency in conceptualizing “regions” in the different layers of entities within and around itself, depending on the contextual geopolitical situations.

Clarifying the concept of “regions” in the UN context is a pre-condition for engaging in further theory-based work on the regional dimension of the UN and UN-regional organizational interactions. Moreover, policymakers would be better informed about the role regions could play in the international order and the potential of effective inter-organizational cooperation in addressing a range of transnational problems in the years to come.

2. Mapping regions in the UN context

2.1. The role of regions in the UN charter

Regional organizations are currently engaged in a wide range of activities, as it is illustrated by their changing mandates and programmatic activities that are “consistent with the Purposes and Principles of the United Nations” (UN, 1945a, Chapter VIII, Article 52,1): namely, the maintenance of international peace and security, and the promotion of human rights. However, the UN Charter does not clearly define the meaning of “regional arrangements or agencies” except to imply that they exist primarily for the maintenance of international peace and security through their “regional actions.” Moreover, the status of a regional organization under Chapter VIII of the UN Charter has never been clear.

Some of the state parties that participated in the Dumbarton Oaks Conference held in 1944 attempted to define regional organizations under the UN Charter and laid down criteria for determining such. For example, Egypt proposed that regional arrangements should be defined as “organizations of a permanent nature grouping in a given geographical area several countries which, because of their proximity, community of interests or cultural, linguistic, historical or spiritual affinities, make themselves jointly responsible for the peaceful settlement […] for the development of their economic and cultural relations” (UN, 1945b, p. 850). However, most participating states rejected this definition, feeling that determining criteria at that stage might obstruct the future development of regional organization (ibid, p. 708). Because of the absence of any solid definition of regional organizations, in Article 52(1) the Charter drafters in Article 52(1) opted to refer to them as “regional arrangements or agencies', leaving the contents of that phrase to be ascertained in practice (Simma, 1995, p. 691).

This lack of definition has led to considerable controversy not only in theory but also in practice, and it has often been considered as one of the factors undermining the operation of Chapter VIII. Despite that, certain organizations such as the Organization of American States (OAS), African Union (AU, then Organization of African Unity), the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Arab League, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), have formally declared themselves to be regional organizations within the meaning of Chapter VIII of the UN Charter (Umezawa, 2012, p. 6–7).

This ambiguity as to the definition of regional organizations in a UN context echoes the ambiguity surrounding terms such as regions, regionalism, and regional organizations more generally. Several scholars have proposed definitions and criteria for “regions” or “regionalism” that respond to a variety of purposes and disciplinary perspectives. For long, many classical theories have focused on a top-down concept of regions, seen as policy-driven or inter-state mechanisms, whilst more recent studies conceive regions as organic and social constructs that are shaped by the combination of endogenous and exogenous characteristics subject to transformation over time (De Lombaerde et al., 2010, p. 731–753; Söderbaum, 2013, p. 9–18). Moreover, regionalism can be perceived either as a concept that transcends nationalism or as sub-globalism contrasted with universalism (Behr and Jokela, 2011, p. 3–6).

Regarding Chapter VIII, the relationship between the UN and regional groups has seen great adjustments throughout the history of the UN. During the Cold War Chapter VIII was rarely used due to the East-West ideological confrontation. The collapse of the bipolar system in the early 90s was followed by the eruption of regional and intranational conflicts (Van Langenhove, 2014, p. 18–21). The UN was thus obliged to strengthen its capacity in the maintenance of peace, in response to the sharp increase in demand for its actions. Fostering a burden-sharing with regional groups, as provided for in Chapter VIII, was regarded as a way forward in this context by the then UN Secretary-General Boutrous-Ghali and highlighted in his report The Agenda for peace, submitted to the General Assembly in December 1992. The SG urged in this report that regional organizations or arrangements should promote their cooperation with the UN Security Council (UNSC) in line with Chapter VIII (UNGA, 1992, paras 62–63). These key ideas were further developed in the Declaration on the Enhancement of Cooperation between the United Nations and regional Arrangements or Agencies in the Maintenance of International Peace and Security of 1995. Here, the UNGA declared a new approach between these two entities with functional cooperation, in compliance with the UN Charter's principles (UNGA, 1995).

The provision of the regional role in the settlement of international disputes is also mentioned in Chapter VI, whose Article 33.1. states that parties involved in an international dispute shall, first of all, pursue a solution resorting to regional agencies or arrangements. However, in practice, the articles of the UN Charter lead to a nonuniform involvement of regional organizations in cases of peace and security. As Bowett has rightly pointed out, a proper interpretation of Articles 51–54 demands recognition and appreciation of the fact that the UN Charter differentiates regional organizations and determines their relationships to the UN based on the specific function they are performing at a given time (Bowett, 2009, p. 215–223).

Article 51 in Chapter VII assures member states' rights of collective self-defense, which can be exercised without a prior authorization of the UNSC, while Article 54 in Chapter VIII obligates regional organizations to report whatever measures they take or contemplate under regional arrangements to the UNSC (White, 2000, p. 27). As such, military alliances that are concerned with mutual assistance against external aggression, such as NATO, are not covered by Chapter VIII (Kourula, 1978, p. 95), and regard themselves to be purely as collective defense organizations under Article 51 (Simma, 1995, p. 690).

Anyway, the end of the Cold War induced collective defense organizations to re-invent themselves in the changing international environment and rethink their peacekeeping role.1 As rightly pointed out by Sarooshi, the delegation of the task by the Security Council and NATO's self-redefinition of its own role has made it possible for NATO to play a Chapter VIII-type role in peace and security (Sarooshi, 2000, p. 251). Therefore, it could be argued that UN-NATO relations in the early 1990s developed along the lines of two models: the so-called subcontracting model based on Chapter VIII of the UN Charter; and the collective defense organization model reflecting NATO's original mandate (Leurdijk, 2003, p. 57–58).

2.2. Regional groupings for electoral purposes

The drafters of the UN Charter were not the first to give an electoral role to regions. The Covenant of the League of Nations established a Council with a few permanent members (the Principal Allied and Associated Powers), while four others would be selected by the Assembly from time to time at its discretion. In 1920, the Assembly of the League of Nations agreed that the main criterion in the allocation of non-permanent seats of the Council should be based on equitable geographical distribution (Daws, 1999, p. 12–13). With the increase of the members of the League, it was understood that three seats of the Council would become semi-permanent and be occupied by Poland, Spain, and Brazil. The six remaining seats would be available for rotation, giving each of the small states representation (Green, 1960, p. 255).

The original Dumbarton Oaks proposals did not include any guidance regarding the criteria for elections (Daws, 1999, p. 15). The evolution of regional electoral groups was driven by the sponsoring powers (US, UK, and USSR in particular). They played a significant role in bringing about the 1946 UNGA “Gentlemen's Agreements” for the distribution of seats on UN elected bodies. It was alleged that, by this agreement, there must be two seats assigned for Latin American, one for East European, one for West European, one for Middle Eastern, and one for Commonwealth members in the UN Security Council (Green, 1960, p. 258). While the “Gentlemen's Agreements” helped create precedents for electoral groups, the sponsoring powers also contributed to the legal foundations by specifying “equitable geographical distribution” as a criterion for elections to the UNSC under Article 23(1) of the Charter, as well as the member states” contributions toward the maintenance of international peace and security (Ziring et al., 2000, p. 49–50).

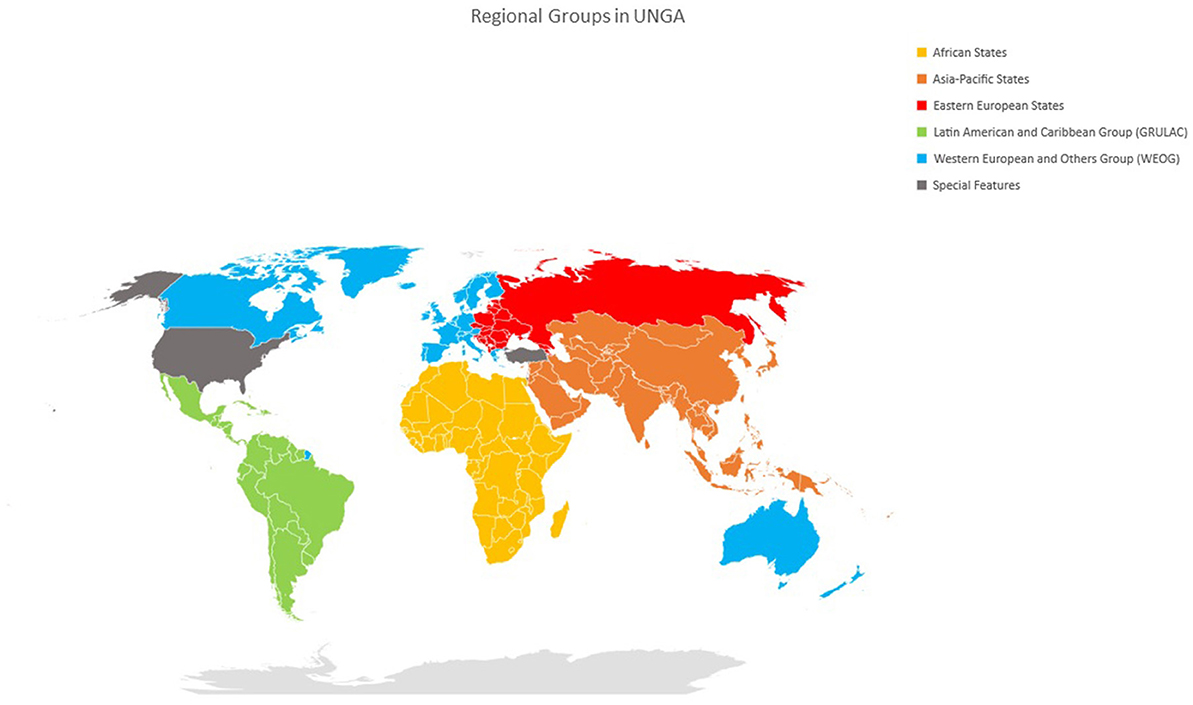

The five overarching electoral groups of the UN are unofficial entities, established informally in 1963 by the UN Member States to organize the distribution of the non-permanent seats of the UNSC according to the “equitable geographical distribution” prescribed by the UN Charter (UN, 1963a,b). Based on this principle, the UN's original 51 members were divided into regional groups. Current 193 members are clustered in five groups: Africa (54 members), Asia-Pacific (53), Latin America and the Caribbean (33), Western Europe and Others (WEOG, 29), and Eastern Europe (23) (see Appendix 1). These regional groupings have played a decisive role in UN elections by making preliminary decisions on the composition of nearly all important UN organs, particularly the UNSC (Jennings, 1999, p. 3).

Each non-permanent member of the UNSC is elected within its own regional group (Ziring et al., 2000, p. 50): five are selected by the Asia and Africa groups, one by Eastern Europe, two by Latin America and Caribbean (GRULAC), and two by Western European and Others (WEOG) (UN, 1963b). These non-permanent members fill the majority of seats on the UNSC, thereby substantially affecting the agenda and resolutions.

Actually, this peculiar seats distribution shows a significant discrepancy in terms of the numbers of Member States included in each group, which range from 23 to 54. The disparity is even more cogent when it comes to the population weights, and the UN Charter's principle of equitable geographic distribution intends for even the smallest member states to have the opportunity to serve in key roles and offices through a system of regional rotation (Laatikainen, 2017, p. 118).

Obviously, the relevance of the electoral groups is affected by changes in world order beyond the UN. For instance, the end of the Cold War profoundly transformed the order within the UN. There have been consequential expressions of interest by certain countries of the Eastern Europe Group in changing membership to WEOG (Götz, 2008, p. 359–360). While initial overtures were deflected for a period, changes inside Europe itself - namely the expansion of NATO and the EU to embrace countries in the Eastern Europe electoral group within the UN - suggest a shift in the real-world order that impacts upon the UN electoral group system and enhances the case for modification.

2.3. Speaking rights at the general assembly

Jurisdictional conflicts between the UN and regional organizations result from how the latter perceive their relationships with the UN. Cooperation between the UN and regional organizations has repeatedly metamorphosed ranging from informal de facto collaboration to highly formalized relationships. The most obvious formal relationship is observer status for regional organizations with UN organs. The UNGA has granted observer status to several regional organizations, including the OAS in 1948, the AU in 1965, The Caribbean Community (CARICOM) in 1991, the EU [then the European Economic Community (EEC)] in 1974, and the OSCE (then CSCE: Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe) in 1993 (UNGA, 2021).

Various regional organizations and other entities can be invited to become observers at the UNGA (UNGA, 2009). They have the right to speak at UNGA meetings, vote on procedural matters, serve as signatories on working papers, and sign resolutions, but not to sponsor resolutions or vote on resolutions of substantive matters. Various other rights (e.g., to speak in debates, to submit proposals and amendments, to reply, to raise points of order, and to circulate documents, amongst others) are given selectively to some observers only.

Most recently, the resolution for the EU's reinforced observer status at the Assembly was adopted on May 3, 2011 with the resolution on Participation of the European Union in the work of the United Nations (UNGA, 2011). As a result of the resolution, the EU has been given the right to speak at the Assembly; circulate its documents directly and without intermediary; present proposals and amendments orally; give a reply regarding its positions. However, the EU representatives have not been allowed a seat among the representatives of other UN member states, nor the right to vote, or to co-sponsor resolutions or decisions. While some states voiced their concern over its potential damage to the nature of the UN as an inter-governmental organization, the resolution A/RES/65/276 adopted in 2011, stated that similar arrangements may be considered for any other regional organization “following a request on behalf of a regional organization that has observer status in the UNGA and whose member states have agreed on arrangements that allow that organization's representatives to speak on behalf of the organization and its member states.” Such wording of the resolution was negotiated with the EU and the group of African/Caribbean states, which had initially blocked the resolution.

Future requests for greater participation by other regional organizations will have to be decided through the vote at the UNGA on a case-by-case basis. Still, the resolution https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/65/276A/RES/65/276 sets a precedent that would make it easier for other regional organizations to upgrade their status and roles at the UNGA. Indeed, the resolution arguably lowered the threshold for other regional organizations to participate within the UN bodies. In its Interpretative Declaration, CARICOM stated that the conferral of identical rights to those given to the EU is neither dependent on duplication of EU's modalities of integration, nor is it premised on the achievement of any perceived “level” of integration (Wouters et al., 2011, p. 168).

2.4. UN agencies in regions

The location of UN offices can take the form of a global UN headquarters or of a regional UN office. The global bodies are sited in a particular city for specific political reasons (e.g., resistance to global and regional hegemonies) and a strong push from one country to host a UN body, usually for purposes of political prestige and income generation. The outcome of the choice, thus, has little to do with regionalism as such. On the other hand, the site of a regional economic commission reflects a conscious decision about regionalism, denoting a capital in the respective region. One of the outstanding features is the dominance of the Western Countries: 14 out of the 21 hosting cities are located in North America or Europe. The rest of the world has 7 host cities: four in Asia, two in Africa, and one in Latin America (ITU, 2021a,b). Another outstanding feature is the dominance of the northern hemisphere over the south where only two host cities (Nairobi and Santiago) are located, one in Latin America and one in Africa. No headquarters or specialized agency, or related organization is located in the southern hemisphere, except the UN Office at Nairobi, which hosts the headquarters of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) (UN, 2021).

Historical and logistical reasons are paramount for this placement. We need to consider the initial skepticism of the Soviet Union against the UN, the political problem of two Chinas after the Chinese civil war ended in 1949, and the fact that most UN entities were established in the 1940s and 1950s before the decolonisation movement was completed. Moreover, the northern hemisphere at the time could better provide adequate buildings, modern technology, and further logistic capacity for these entities.

2.5. The regional economic and social commissions

The regional commissions of the UN were founded as functional bodies by the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and are each in turn established to address socio-economic issues in the region (UN, 1945a, art. 68). This regional approach derived from the recognition of the need to promote economic activity and social stability in the “areas” devastated by World War II. Between 1947 (ECOSOC, 1947) and 1948, three of what became five regional commissions were established: the Economic Commission for Europe (ECE) (Berthelot and Rayment, 2004, p. 56), the Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East (renamed, decades later, as Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) to adequately reflect the social aspect) (De Silva, 2004, p. 140–141), and a commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLA) (Rosenthal, 2004, p. 172) (renamed to ECLAC due to the incorporation of the countries of the Caribbean as a sub-regional entity) (ECOSOC, 1948, 1984). ECOSOC remarked on the valuable work delivered by the three regional commissions, which culminated in the continuity of their existence.

The tone had been set for other regions, and following a recommendation by the UNGA (1957), ECOSOC established the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) in ECOSOC (1958). Behind the vaguely stated objectives of strengthening economic cooperation, considerable fragmentation existed. Whereas, ECE sought to serve the perpetual existence of their “community” by building a bridge of functional cooperation between East and West, the commissions of ECLAC, ESCAP, and ECA, which were characterized by forms of internal fragmentation, assisted in the creation of a sense of community and cooperation (Gregg, 1966).

Countries in Western Asia had been omitted from ESCAP. In October 1947, the UNGA had invited ECOSOC “to study the factors bearing upon the establishment of an economic commission for the Middle East” (UNGA, 1947), and in December 1948, it had recommended that they should expedite consideration of the matter (UNGA, 1948). In the meantime, the formation of ECA in 1958 took away North African countries, which otherwise were seen as part of “the Middle East”. Bound to the UN's overall commitment to development efforts, a substitute commission named the United Nations Economic and Social Office in Beirut (UNESOB) was created in 1963 to cover independent countries unable to join the regional commissions then in existence (Destremau, 2004, p. 310). Delayed by political considerations concerning enduring Arab States-Israeli conflicts, the Economic Commission for Western Asia (ECWA) was eventually established in 1973 (ECOSOC, 1973). It followed ESCAP in the recognition of the social component of development within its mandate and therefore was renamed to the Economic and Social Commission in Western Asia (ESCWA) (ECOSOC, 1985).

Various obstacles have hampered the work of some of the commissions, such as disputes among member states (such as Arab vs. non-Arab states in ESCWA), a duplication of regional efforts, a lack of resources, expertise, and a centralized administrative hub, added expense, and needless fragmentation. Among them, geographical ambiguity has been one of the most prominent problems regardless of the underlying patterns of regionalism. Highly heterogeneous and expansive regions such as West-Asia and Asia-Pacific are difficult to define. As for Europe, the disintegration of the Soviet bloc and the former Yugoslavia has brought about a significant level of diversity amongst its membership.2 As such, the commissions, except for ECA, are political hybrids due to the inclusion of exogenous countries.3

Apart from undertaking development analysis, the regional commissions have also been expected to play roles in promoting regional cooperation in line with the purpose of the UN. In the past, the UN's regional approach through the commissions spurred the creation of regional institutions in different domains and continents. For instance, ECE provided early impetus to European integration under the leadership of the Swedish development economist Myrdal (Stinsky, 2018). During the 1950s, ECLA played an important role in criticizing the liberal economic model's applicability to dependent states, and, conversely, it promoted common market projects (Mingst et al., 2017, p. 139–140). Some of the regional development banks were brought into existence by the respective commissions (Szasz and Willisch, 1983, p. 296–301). Closer cooperation among clusters of adjacent countries and sub-regions with similar interests provides a fertile ground for more direct and concerted governance. Keeping this in mind, ECA, ESCAP, and ECLAC have established their own sub-regional offices to provide for sub-regional dialogue. Notwithstanding the ambiguity of their role, the regional commissions have built longstanding relationships with regional and subregional organizations and multilateral development banks.

In 1994, the Joint Inspection Unit (JIU) reviewed past and current efforts to restructure the regional dimension of the UN's economic and social activities (UN, 1994). In the framework of previous attempts at decentralization to the regional level, it particularly discussed the UNGA Resolution 32/197 and its implementation on the restructuring of the economic and social sectors of the UN system, which set the stage for the regional commissions to play a central role. The report stressed that the role of regional commissions has remained rather ancillary in practice, despite ensuing various efforts to provide a focal point for cooperation within their respective regions. Another JIU report (JIU/REP/92/6) shared this point of view, that only limited decentralization has taken place from the UN Headquarters level to the regional commissions (UN, 1992), and that it was even far outdone by the inadvertent proliferation of various UN programmes and bodies at the regional level. Recognizing their potential, numerous initiatives and measures have been introduced since the early 1990s to unlock the wealth of expertise of the regional commissions and to strengthen regional cooperation (ibidem).

Regarding interregional cooperation, the foundation of the Regional Commissions New York Office (RCNYO) in 1981, provided an early mechanism for communication among the commissions, as it was designed as a small joint office to liaise with the headquarters units (UN, 2015). Alongside initiatives to assert coherence at the regional level, the Secretary-General's 1998 report urged for better coordination between activities of the regional commissions and other regional activities within the UN system, and to reinforce synergies while avoiding duplication (ECOSOC, 1998a). Subsequently, ECOSOC resolution 1998/46 recognized their leadership role to “hold regular inter-agency meetings in each region with a view to improving coordination among the programmes of work of the organization of the United Nations system in that region” whereupon the Regional Coordination Mechanism (RCM) was duly created (ECOSOC, 1998b).

The 2005 World Summit advocated for a stronger relationship between the UN and regional organizations, whereupon the High-Level Panel (HLP) presented their recommendations as to the reconfiguration of the UN regional setting for the UN to perform as one (UNGA, 2005a). Significantly, the Panel called for a UN regional setting and that they “would act as a catalyst for these [analytical, normative and activities of transboundary nature] functions” and recommended to clarify the roles of the regional commissions (UNGA, 2006).

Although the critical role of the regional commissions has been strongly reaffirmed and recognized, notably due to their support for regional cooperation and institution building, their actual relevance and existence have sometimes been contested. Browne and Weiss question their actual existence by presenting results from conducted surveys of all major occupational groups, which indeed denote the commissions at the bottom of the ranking of UN's main development organizations (Browne and Weiss, 2013, p. 3). Similarly, the JIU issued a report on the coordination among the regional commissions in 2015, which emphasized the need and room for improvement where the current mechanisms are not fully adequate (UN, 2015).

2.6. Regions as statistical categories

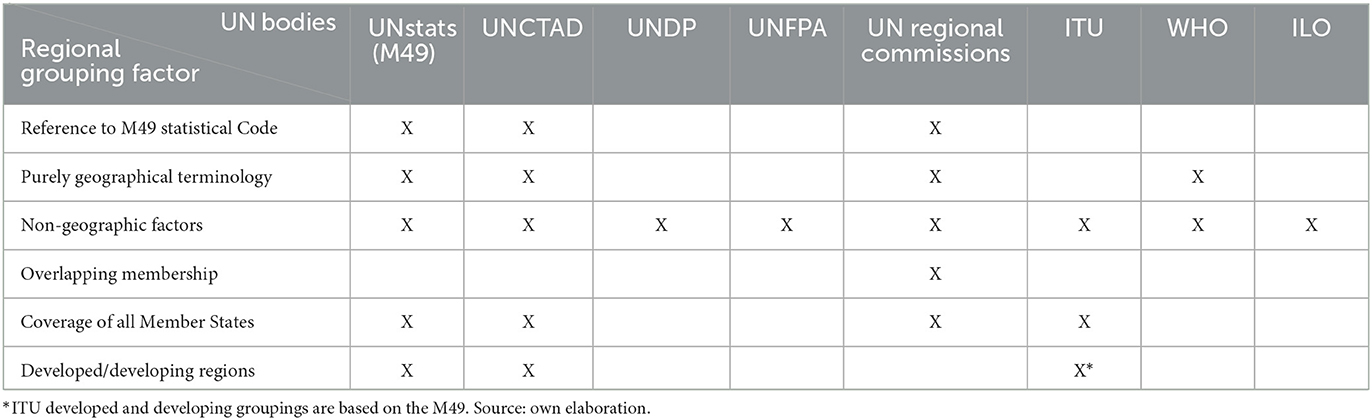

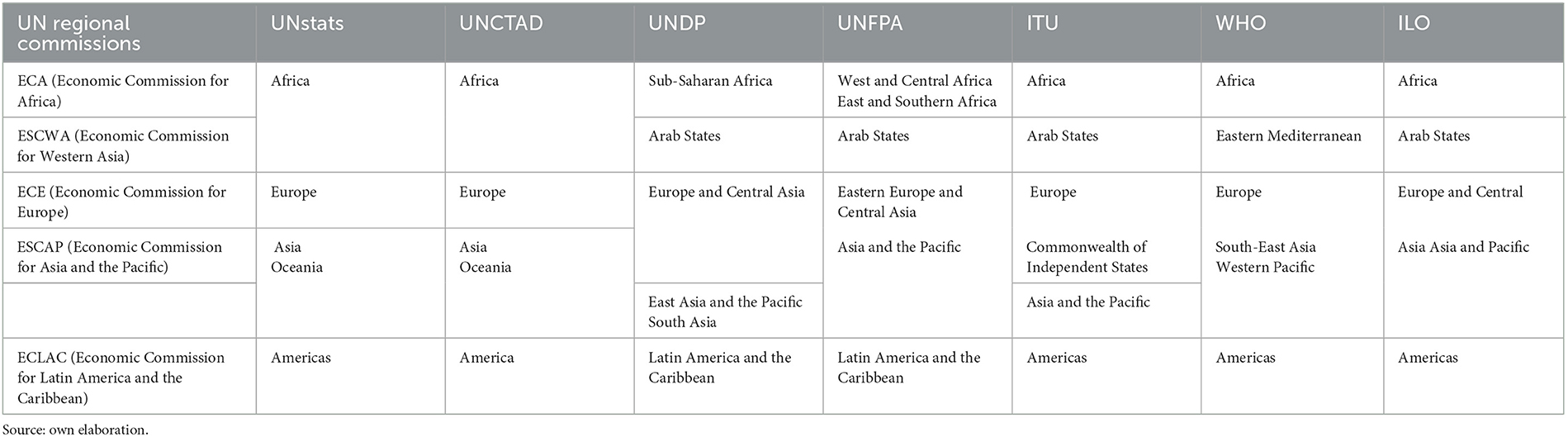

Regions also appear as statistical categories when the UN acts as producer of official statistics. This is the case for UN agencies including UN Statistics Division (UNstats), UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), UN Development Programme (UNDP), UN Population Fund (UNFPA), UN Regional Economic Commissions, International Telecommunication Union (ITU), WHO, International Labor Organization (ILO), etc.

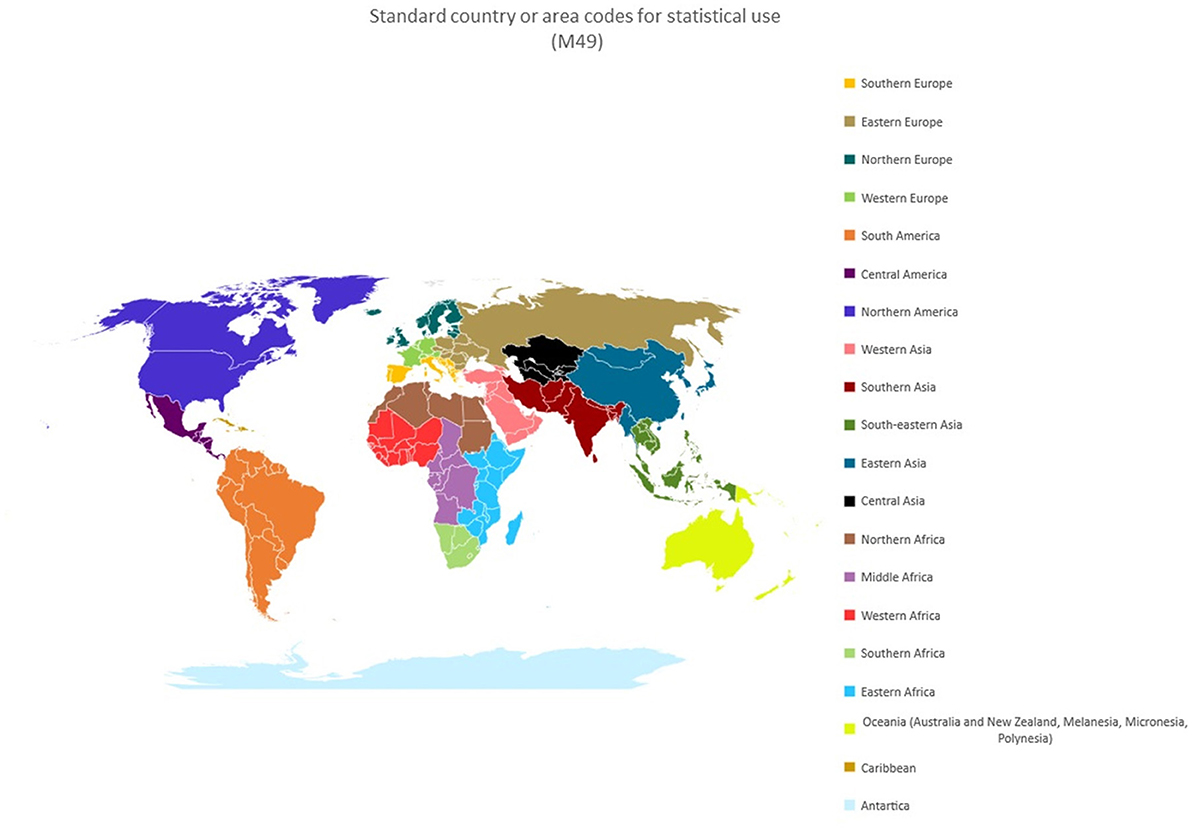

UNstats is a useful and obvious first port of call as it should, in theory, set the standards for regionally grouping UN member states for statistical purposes. In 1969, UNstats first published the “Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use” (Series M, No.49/Rev 4), commonly referred to as the M49 Standard, although it does not seem to set a standard for the entire UN system. UNstats explains that its regions are “arranged to the extent possible according to continents … within these groupings more detailed component geographical regions are shown” (UNSD, 2006), suggesting regions are defined on a purely geographic basis. Indeed, the desire to avoid politics is explicitly mentioned: “the assignment of countries or areas to specific groupings is for statistical convenience and does not imply any assumption regarding political or other affiliation of countries or territories by the United Nations” (UNSD, 2021a). Nevertheless, many cases within the M49 add nuance to these affirmations. Appendix 2 shows a M49 world map.

UNstats groups the world into Africa, Americas, Asia, Europe, and Oceania (UNSD, 2021b). These groupings contain subdivisions that at first appear to be consistent with this geographic logic, yet other elements seem to play a role. Within the Americas (019), the point is made that Northern America (021) as a sub-region is distinct from “the continent of North America” which comprises the sub-regions of Northern America (021) as well as the Caribbean (029) and Central America (013) which themselves appear under a Latin America and the Caribbean (419) heading. This indicates that geography alone is not the only criterion defining regions in statistics. While no explanation appears on the UNstats website, it may reflect that Northern America is an economic grouping, and refers to Canada and the US, although Bermuda, Greenland, and Saint Pierre and Miquelon also appear in Northern America (021). Moreover, following economic logic, one is to wonder whether Mexico should not be included in the context of the North American Free Trade Agreement (now, USMCA). Finally, the term “Latin America” seems to imply that an element of linguistics or culture has been considered in defining this grouping.

Oceania (009) contains a subregion of Australia and New Zealand (053), separate from Melanesia (054), Micronesia (057) and Polynesia (061) which again may reflect an opinion on the similarity of these two countries in terms of culture and history, as distinct from other island nations. After the declaration of independence in 2011, Sudan and South Sudan, which before appeared as Sudan in Northern Africa (015), appear in Northern and Eastern Africa (202) respectively, which again may have religious or political underpinnings. As UNstats is devised for analytical and statistical purposes by a large audience, all regions are mutually exclusive. The Russian Federation spans two continents, Europe and Asia, and is therefore included only in Eastern Europe.

It is fair to say that UNCTAD adopts the closest match to the M49 standard of UNstats. Apart from the different values of the five main regions [Africa (5100), America (5200), Asia (5300), Europe (5400), and Oceania (5500)], it follows the M49 standard according to which the world is divided in main regions. Cyprus provides an example of underlying nongeographical motivations. Although it is an Asian country geographically, Cyprus is to be considered a European country due to its political inclinations and complex history, which provides another example of underlying nongeographical motivations (UNCTAD, 2021).

The regional dimension is inherent in the five regional economic commissions. UNECE operates with and for a highly diverse group of member countries located in Europe, North America, the Caucasus, Central Asia and Western Asia. UNECE also lists several overlapping subregions in its areas of work; the Baltic Sea, Black Sea, Caspian Sea, Caucasus, Central Asia, Eastern Europe, Mediterranean Sea, and South-Eastern Europe (UNECE, 2021). UNESCAP states in its statistics methodology that its five subregions are “geographical” (UNESCAP, 2021): East and North-East Asia, the Pacific, South-East Asia, South and South-West Asia, North and Central Asia, and these are indeed used in its reports, providing a regional perspective on development issues in the respective regions (UNESCAP, 2013). ECLAC and UNECA both use regional classifications which generally reflect those of UNstats, with some slight differences. Although its Methods and Classifications section provides a direct reference to the use of regional classifications of the M49 (ECLAC, 2021a), ECLAC makes a clear distinction between Central America and the Caribbean when defining its sub-regional headquarters. UNECA uses regional classifications that reflect even more those of UNstats. It is organized into five sub-regions: North Africa, West Africa, Central Africa, East Africa, and South Africa (ECLAC, 2021b). Yet, UNstats also refers to Sub-Saharan Africa. Among all regional commissions, UNESCWA covers the smallest group of countries. Wedged between two different continents, Africa and Asia, the Arab region stands out for its homogeneity in terms of language and civilization which evidently discards geographical conditions. Contrary to regions in statistical classification as seen above, overlapping membership of countries is common given the varying focus of the regional commissions in their respective regions. To that end, a degree of political pragmatism can be identified behind double memberships in commissions. More specifically, the dismantling of nations, large and small, and the de-colonization has shaped the membership of each commission over time (Berthelot, 2004, p. 11). Non-regional countries have been granted membership either because of their economic activity (e.g., the US in ECE and ESCAP), or they were governing territories in the concerning region (e.g., France, the Netherlands, and the UK in ECLA and ESCAP) (Szasz and Willisch, 1983, p. 296–301).

The regions used in UNDP are markedly different from the UNstats regions not only in their naming, which does not follow continental lines, but also in their composition (UNDP, 2021). Perhaps most striking is the inclusion of an “Arab States” region, which is another overt classification of a region based on something other than geography: in this case, ethnicity, culture, and language. Notably, Israel is omitted from this region. This also seems to fit more or less with political conceptions of “the Middle-East and North Africa.” UNDP's regional classification comprises developing groupings, in accord with its mandate concentrated on development, while certain countries remain unclassified and are among what is commonly referred to as “The West” or the “developed world” (the US, Canada, Western Europe, Israel, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and South Korea). This may simply reflect that these countries represent a group of highly developed states against which the UNDP measures other regions.

UNFPA sticks predominantly to a geographical criterion when grouping countries. Similarly to UNDP, UNFPA does not cover countries or regions having a developed status in its operations and classifications (UNFPA, 2021). However, UNFPA refers to “Middle East and North Africa” in its reports instead of “Arab States” (e.g., UNFPA, 2014). Alternative naming for common groups of countries is ordinarily used throughout the UN system. For instance, the ITU's regional groupings can be defined as quite geographical, except that the Commonwealth of Independent States is treated as a distinct group (ITU, 2021b). Another example is how UNDP uses “Europe and the CIS” in its evaluation reports and statistics for the region “Europe and Central Asia” as defined on their website.

The regional groupings WHO uses for its Health statistics and information systems employ pure geographical terms (e.g., Mediterranean) but with curious divisions (WHO, 2021). The “Eastern Mediterranean Region” incorporates what other bodies classify “Arab countries,” while East Asia is into “South-East Asia Region,” which includes the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea), while the Republic of Korea (South Korea), is part of the Western Pacific Region (which also includes Australia and Papua New Guinea, but not Indonesia).

Finally, the ILO uses one of the most geographically based classifications of regions, although it includes an “Arab states” region, albeit by far with the narrowest set of countries included in such a classification (ILO, 2021).

The adoption of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), and subsequently the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), prompted a considerable impetus for many agencies to enforce the classification of meaningful regional groupings for the presentation and usage of data, as they explicitly focus on global and regional progress. The classification adopted by the United Nations Statistics and Population Division, based on a combination of geographical and development level criteria, would serve as a basis for many agencies to achieve as much conformity as possible (UNSD, 2006). Since then, there has been significant progress toward geographic location for regional groupings due to deficiencies and inconsistencies. Previously, data were presented for countries in developed regions and developing regions, which were further subdivided according to the M49, including some modifications. Taking into account considerations made by UNstats (ibid.), countries and areas are grouped into eight SDG regions broadly based on the geographic regions defined under the M49, which are further broken down into 22 geographic subregions. Table 1 summarizes the criteria for regionally grouping UN member states for statistical purposes.

3. Ongoing debates: regional dimensions

3.1. Promoting UN-regional organizations cooperation in peace and security

The strategic choice of developing the global-regional cooperation mechanism for the maintenance of peace and security has been reflected in the reform process the UN has been going through. Moreover, the UN Secretariat initiated dialogues with regional organizations through various channels, including high-level meetings (Van Langenhove, 2009). The ensuing reports have reiterated the standard themes of support for increased cooperation with regional organizations and the need for greater coordination and resources.

The UN's approach with the measures provided for in Chapter VI suffered changes after the end of the Cold War, specifically in the structure of peacekeeping and in the role of mediation in the peaceful settlement of disputes. First-generation peacekeeping served as a military tool to solve and manage conflicts, but so-called second-generation peacekeeping has a primary role to manage and contain, not resolve conflicts (Mateja, 2019, p. 31–32). In the peaceful settlement of disputes, regional groups play a key role, especially after 1992 with the new cooperation approach in An Agenda for peace.

In An Agenda for Peace, the UN Secretary-General Boutros-Ghali suggested that the cooperation between regional organizations and the UN “must adapt to the realities of each case with flexibility and creativity” (UNGA, 1992, para. VII). On the specific issue of task-sharing in peace operations by the UN and regional organizations, in 1995 the JIU issued a Report on Sharing Responsibilities in Peace-keeping: The United Nations and Regional Organizations (UN, 1995). The report is based on the understanding, provided in Chapter VIII and VI of the UN Charter, that regional organizations should be the first port of call for the prevention and peaceful settlement of local disputes (ibid, para. III). The report also argued that regional organizations “should be given all possible assistance to do so” (ibid, para. VI) through the enhanced coordination and cooperation among various entities of the UN.

The September 11 attacks in New York overturned the international order, above all in peace and security. In 2004, the High-level Panel (HLP) tried to reformulate the notions of responsibility and obligation of the international system in the post-9/11 world, both in terms of the nation-state and the international community, and most concretely the UN itself. The HLP report concluded that the UNSC had not made the most of the potential advantages of working with regional organizations, considering that there still exists potential for a stronger partnership between them and the UN. The ability of the UNSC to become more proactive in preventing and responding to threats “will be strengthened by making fuller and more productive use of Chapter VIII provisions of the Charter” (UNGA, 2004, para. 270). It was argued that regional actions should be organized within the framework of the Charter and the purpose of the UN, and that integrated UN-regional organizations cooperation should be ensured (ibid, para. 272).

The 2030 Agenda for sustainable development set out that “[t]here can be no sustainable development without peace and no peace without sustainable development” (UNGA, 2015). This means that development and peace and security pillars are strongly interconnected. For this reason, the UN reform of 2018 introduced several changes not only in the development pillar but also in the peace and security one facilitating the coordination with regional organizations. In this sense, the reform is aiming at organizing and integrating existing capacity resources more rationally, and to create new departments. The most significant structural reform has been the institution of the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA), which would combine the strategic, political, and operational responsibilities of the Department of Political Affairs (DPA) and the peacebuilding responsibilities of the Peacebuilding Support Office (PSBO) (Telò, 2020, p. 234–236).

The core work in conflict prevention, preventive diplomacy, and mediation of DPPA is regularly carried out in partnership with regional organizations, to ensure information-sharing and cooperation on regional or country-specific issues of mutual concern. This collaboration happens also when regional or sub-regional organizations take the leading role in a diplomacy action, and the UN acts as a facilitator or advisor to settle a dispute (UN, 2018). The DPPA dedicates institutional capacity to analyzing threats to peace and security in partnership with the Department of Peace Operation (DPO) and keeps relevant tools and capacities for prevention and mediation. In managing its commitment in preventive diplomacy, the DPPA relies on regional offices (UNGA, 2017).

The already mentioned PSBO, as part of DPPA, support another department established in the 2005 In Larger Freedom report (UNGA, 2005b), the Peacebuilding Commission, through strategic advice and policy guidance. This support consists of bolstering a functional linkage between DPPA, DPO, and a single regional-political structure to allow the Peacebuilding Commission to share regional analysis, strategies, and field presence.

The single regional-political structure consists of the merger of regional divisions of DPPA and the DPO into a single structure to be shared by both departments. This structure aims to improve regional analysis, facilitate early warning and the activation of preventive measures, and enhance cooperation with regional and sub-regional organizations. The success of this single regional-political structure relies on strong partnerships and coordination mechanisms.

While the peacebuilding structure is part of the Peace and Security pillar, it also bridges the UN's peace and security architecture and the UN development system as well as humanitarian actors. This also includes a great collaboration with international financial institutions, especially with World Bank, as well as civil society and other private stakeholders (UNGA, 2017, paras. 25–26).

An important example of cooperation between the UN and regional organizations is the partnership with the African Union. The form and the purpose of the partnership was illustrated in the Joint UN-AU Framework for Enhanced Partnership in Peace and Security (UN, 2017). This document builds on an increasing cooperation among both organizations since 2006, which involves conflict prevention and mediation, with a strong emphasis on the peacebuilding process. The UN support involved several thematic areas, in which the DPPA is leading the cooperation in the peace and security domain (UN, 2018).

A previous important reform on the peace and security pillar, namely the UN High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations (HIPPO), produced important recommendations to enhance the UN's action in peace operations (Erthal Abdenur, 2019, p. 54–56), and a new approach with a double role for the UN. On the one hand, UN target the future world, as a partner responding politically and operationally alongside regional groups. On the other hand, UN act as an enabler and facilitator to allow other international organizations and regional groups to play their increasingly prominent roles in peace operations (HIPPO, 2015, paras. 54–56). According to the last reform, which keeps this approach, this double role means to create triangular cooperation between the UN, regional organizations and other international organizations, and other key stakeholders at the national or local level (UNGA, 2017, para. 49).

3.2. Regional dimension of the UN security council reform

The end of the Cold War and regional instability that followed, inevitably led to a radical expansion in peacekeeping duties for the UN. Between 1988 and 2000, the UNSC adopted more than twice as many resolutions and the peacekeeping budget increased more than tenfold. Although the revitalisation of the UNSC in the post-Cold War era has activated the UN in addressing new security threats, the decision-making process was still hampered at times due to the use of vetoes by the SC's five permanent members (P-5). Besides, the UNSC has temporary members that hold their seats on a rotating basis by regional groupings, reflecting the principle of equitable geographical distribution. The number of non-permanent members was expanded from six to ten in 1965 as a response to the wave of decolonisation transforming the status of some of the regional groups. The veto power exclusively given to P-5 contradicts with the UN's universal values, including equal rights of member states and people. The debate on equitable representation in the SC has been going on for the past three decades, with various reform proposals made by different groups (UN, 2005a,b). None of them have been voted upon so far, because of a range of political disagreements among the member states (Hosli and Dörfler, 2019, p. 44). Indeed, two-thirds majority of the UNGA membership would be required for the amendment of the Charter, in addition to the inclusion of all the P-5 members regarding the SC reform (ibid, p. 39–41).

3.3. Regional dimension of the post-2015 development agenda

On another note, the post-2015 development agenda is intended to address problems left unsolved by the MDGs by introducing a more inclusive conception of human development than its predecessor. The 2030 SDGs agenda, adopted in September 2015, includes new goals that are profoundly interrelated and multi-disciplinary while calling for an approach that breaks down silos. Furthermore, the new framework is meant to become a truly universal agenda that should be owned by both North and South alike and translated according to local needs and specificities, to overcome regional and national disparities.

Deriving from the MDG framework and process, which exposed the discrepancy between maintaining global goals and adapting them to national realities, greater attention was paid to regional priorities and solutions, as different regions need to address different challenges to achieve sustainability, according to their level of development (UNDP, 2013). The joint report of the UN Regional Commissions on A Regional Perspective on the Post-2015 United Nations Development Agenda points out that there are indeed distinct regional development priorities (UN, 2013). Given the fact that the goals are global in nature, an intermediate level of governance ensures ample space for national policy design as well as adaptation to the local setting. This way, a new regional development paradigm would unleash a desired shift toward more ownership and diversity of development approaches (Cavaleri, 2014, p. 9).

The regional commissions, along with other regional institutions, were actively engaged in consultations to formulate regional positions on the SDGs (UNECA, 2012, p. 10–11). Prior to the adoption of the SDGs, they jointly published a report emphasizing their willingness to offer platforms for sharing knowledge and best practices to promote a balanced integration of the three dimensions of sustainable development (UNECA et al., 2015). Moreover, in a separate report, they rightly pointed out that the regional approach is useful in addressing regional or transboundary challenges critical for achieving sustainability (RCNYO, 2014). The role of regions is identified in the process of implementing and translating the SDGs into regional priorities, as well as assessing and reporting the progress made toward the achievement of the SDGs (HLP, 2013). The regional commissions have been encouraged to enhance their cooperation with development banks as well as regional states, hence promoting global-regional dialogues (ibid.). The High-level Panel refers to the experience of regional groupings coming together to discuss their common interest, reinforcing global-regional cooperation in addressing the SDGs. Moreover, High-Level Political Forum (HLPF) regional platforms in Asia, Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and Europe are intensifying multi-stakeholder collaboration in addressing both region-specific and transboundary issues (ibid, 24).

The complexity of the SDGs gave direction to a thorough review of the UN development system. The 2016 quadrennial comprehensive policy review (QCPR)4 and the successive GA Resolution 72/279 2 years later paved the way toward a more integrated and cohesive UN development system to better support SDGs implementation. From the very outset, SG Antonio Guterres has underscored the importance of realigning the UN's regional assets in his ambitious package of reform proposals (UN, 2020). At the regional level, the focus turns to a two-phased reform of the UN's regional architecture: optimisation of functions and collaboration between different entities at the regional level, followed by the discussion on policy options aimed at longer-term restructuring on a region-by-region basis (ibid, 3). The review of the UN development system has brought about the SG's five recommendations, together with options for strengthening the UN's eight multi-country offices, that will eventually help the UN to advance toward a global organization “fit for purpose” (UNGA, 2019).

The reform efforts of the UN's regional dimension and the implementation of SDGs are complementary to each other and mutually beneficial (Bachmann and Surasky, 2020). Still, the lack of political will to implement reform of UN-regional cooperation architecture remains unsolved. Drawing on research-based information assembled from all UN regions, the CEPEI report on A Sustainable Regional UN concluded that the conscious efforts should be made to reform the regional architecture to allow renewed engagement with other stakeholders and regional organizations (CEPEI, 2019). Likewise, the SG reiterated at a meeting on Regionalism and the 2030 Agenda the significance of the regional commissions for SDG implementation at regional levels, while commending the strengthened partnerships with other regional organizations including the AU, League of Arab States, ASEAN, and the EU (Ki-Moon, 2016). As the decade of action has begun, the UN regional level is proactively approaching consultations on optimizing the regional architecture (UN, 2019). To that end, in his 2020 report on the UN development system, the SG stated that the regional dimension has finally embraced the reform measured by a significant increase in its engagement and that a “single coordination system with buy-in across all entities of (the UN development system) in the regions” will be elaborated (UNGA, 2020). Revising the regional architecture at the UN is an ongoing process; reform efforts will unfold alongside continuous interactive dialogues with Member States.

4. Discussion: toward a typology of regions in the UN context

4.1. Toward a typology of UN regions beyond electoral vs. operational

Looking for tangible and distinct regional dimensions within the UN system, this paper has mapped various regional structures and classifications in the UN context. This section argues against this mapping exercise by adopting Graham's suggestion that there are two basic types of regionalism in the UN, namely “electoral” and “operational” (Graham, 2008, p. 22–24). The former is meant for UN bodies electoral purposes, while the latter is witnessed in the functional bodies within the UN system (i.e., the Secretariat, the regional economic commissions, major UN programmes and funds, major specialized agencies and other related UN organizations) and can be broken down into socio-economic and security operations.

While Graham acknowledges the degree of political concord within the electoral group, his classification leaves out the political role of institutionalized or non-institutionalized regional groups inside the UN system, neither it considers regional systems that work beyond the UN system.

Also, Laatikainen's typology for group dynamics within the UN proves cogent in this context. Next to regional electoral groups, the scholar takes into account regional organizations, political groups, and single-issue political groups. Laatikainen also points to the political aspects of UN multilateral diplomacy that is embodied in inter-group dynamics within the UN, including at the regional level (Laatikainen, 2017).

As was demonstrated throughout this paper, regions within and around the UN system differ in terms of criteria, activities, and capacities. Furthermore, the status and perception of states gathered in groupings are constantly changing, reflecting the transformation of the international panorama. Therefore, the academic debate needs going beyond Graham's (too) broad typology and conceiving a new typology of regionalism embedded in the UN system that accounts for the development of a sophisticated multidimensional policy framework over time. In addition, regions have significantly evolved throughout the past decades, in terms of their status, configuration, capacities, and forms of function, which in turn has affected the relationship with the UN. Figure 1 shows the suggested alternative conceptualization of “regions” beyond electoral vs. operational.

Figure 1. Political vs. operational conceptualization of regions in the UN system. Source: own elaboration.

Consequently, a three-dimensional typology is envisaged. A first dimension refers to the roles regions assume within the UN system. We consider two basic roles: political, referring to the roles regional organizations and regional groupings play in UN diplomacy and decision-making processes; and operational, referring to the roles they have in the implementation of previously decided UN policies or actions (i.e., “on the ground”). While we attempt to assign regional groups to these two categories, it should not be presumed these roles are mutually exclusive. Regional organizations exercise either political and operational competences, and some of them engage with the UN through various forms ranging from partnerships and collaboration to formal embedded relationships, albeit shaped under Chapter VIII of the UN Charter. Regional interlocutors of the UN play both political and operational roles. For instance, engagement with the DPPA is political by definition. However, at the operational level DPPA also engages in “desk-to-desk” dialogues with regional organizations to better understand how the different institutions work, improve channels of cooperation, and develop recommendations in the field of peace and security (UN, 2018).

A second dimension refers to the degree of institutionalization of the regional groups. While some regions, such as the AU or EU, are institutionalized regional organizations, other regions within the UN system are ad hoc regions that do not have a materialization (institutionalization) outside of the UN system. Statistical regions include both types (institutionalized regions as well as geographical/cultural regions), whereas non-institutionalized regions include, for example, electoral groups in the UNGA since they are forms of regional coordination informally active within the UN system. The evolution of their practices raises questions about their role and level of formalization within the UN.

This allows to distinguish a third dimension referring to whether the region has a formalized status (e.g., UN treaty-based) or, on the contrary, operates informally within the UN system. The fact that various regional organizations attained speaking rights at the UNGA could be interpreted as the beginning of a formalization within the UN system, attributing them the legitimacy to speak on behalf of certain UN member states. By contrast, other regional groupings such as the G-77 and the Non-Aligned Movement have the capacity to play political roles in the UNGA, going beyond the framework of Chapter VIII, without being given a formal status within the UN. The non-institutionalized counterparts of the latter include the so-called Groups of Friends that are coalitions of UN member states, who band together to actualise particular goals and outcomes related to specific issues or situations (Deutch, 2020).

Furthermore, there are the regional institutions (e.g., regional commissions, UN programmes and funds, and specialized agencies) that are established under Chapters X and XI of the Charter. They follow rather a top-down methodology that runs counter to the objectives of institutionalized regional originations that emerged bottom-up.

4.2. Problematising regions in the UN: inconsistencies as entry-points

One strategy to critically assess how regions are conceptualized in the UN context is by focusing on de jure or de facto inconsistencies. This is the case in the UN major bodies and reflects historical paths and political situations. First, the composition of the regional electoral groups seems to be based on a combination of different criteria: as shown in Appendix 1, the African Group and GRULAC are clustered based on geography, while the two-European groups are split for historical and political reasons (De Lombaerde et al., 2012, p. 5–8). As far as the WEOG is concerned, legitimacy and effectiveness may lead a state to participate in a different group of countries for a specific purpose: this is the case of the “others” who are involved in the WEOG for electoral purposes and belong to this group not for geographical reasons but for common affinities and community of interest.

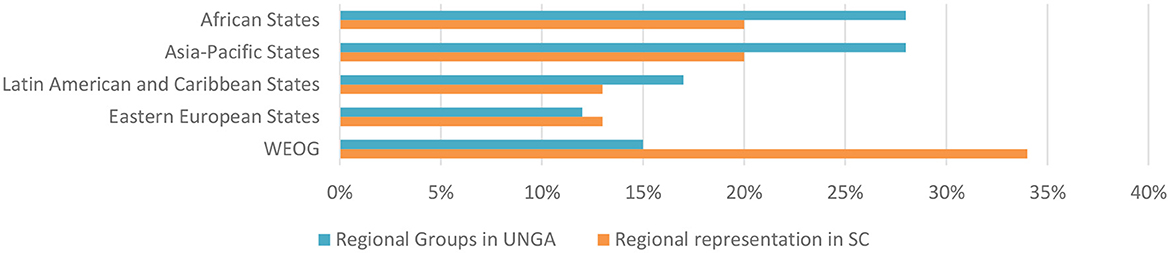

The importance of history and politics is also clear when looking at the composition of the UNSC. The comparison of the regional groups' composition in the UNGA and the distribution of the UNSC seats among regional groups demonstrates that WEOG is the only regional group that is over-represented in the UNSC, where 15% of the UNGA member states are dominating 34% of seats (Figure 2). The mismatch between regional groups and the UNSC's composition signifies a discriminatory status for Asia-Pacific and African groups especially. Although the two groups represent 28% of the UNGA, they are underrepresented in the UNSC, occupying only 20% of the seats. GRULAC shows higher consistency in this representation, while Eastern European States are the best-represented group in the UNSC. The current inequitable regional representation in the UNSC is because the UN was established before the wave of decolonisation in the 60s, which resulted in a significant increase of its member states. A good case can therefore be made for a UNSC reform, to achieve an appropriate regional representation thereby enhancing the legitimacy and coherence of the UN system.

Figure 2. Mismatch between regional groups in UNGA and regional representation in UNSC. Source: own elaboration.

Regions are frequently used as a unit of measurement and point of departure for the UN statistics, yet inconsistencies across the UN bodies regarding their classification are prevailing. While a pure geographic approach is favored by some UN organs, others opt for more nuanced approaches that are relevant for the nature of their work with various additional socio-cultural or economic elements. Moreover, regions are not always regarded as mutually exclusive entities, and substantial overlap exists (Table 2). North-African countries are conceived sometimes as African countries and sometimes as Arab countries: in the first case, a geographical criterion is followed, while in the second an ethnical/cultural criterion is used. Finally, the formation of regional and subregional groupings is subject to change, due to political and cultural considerations in the changing international order.

Regional economic commissions are commonly perceived as the regional outposts of the UN. Whereas, the rationale for establishing the regional commissions was the enhancement of the post-war reconstruction, they have been aiming to foster economic development through regional cooperation, within the UN policy frameworks (Szasz and Willisch, 1983). The regional context in which the commissions operate has shaped their area of focus and mandates, as well as their relative strength (Malinowski, 1962; UN, 2015, p. 6). As a result, they have different mandates and play different roles in different regions. ECE, for example, ceased publishing its economic surveys in 2005 and has focused on work on international legal instruments since then (Browne and Weiss, 2013, p. 2). The broadening of the scope of regional organizations and their proliferation during the “new regionalism” wave has put the relevance of the regional commissions under scrutiny. Against the backdrop of increasing regional dynamism in the global order, in its 1995 report Our Global Neighborhood, the Commission on Global Governance urged the UN to reconsider the regional commissions” role as an integral part of global governance, to prepare itself for the time “when regionalism becomes ascendant worldwide and assist the (global)c process” (CGC, 1995, p. 291). The SG's initiative to restructure the UN's peace and security pillar with the aim of coordinating it with the sustainable development pillar offers a great opportunity, since it enhances the regional commissions” strategic approach within the systemwide UN coherence.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

This paper proposed a new typology for better understanding UN-regional organization interactions and, more generally, the regional dimension of the UN. It considers the variety of regional expressions in the UN and the historical and political contexts that shaped them. Reflecting the worldwide rise of the regional phenomenon during consecutive regionalism waves, its expressions within the UN system considerably overcome the Chapter VIII's ambiguous definition of regional organizations and their role in peace and security. Adopting an inductive approach, the paper starts from a detailed mapping exercise of the regional dimension within the UN in section one. This operation included formal or informal regional entities within the UNGA either as electoral groups or regional organizations granted with permanent observer status, and in the UNSC, as economic regional commissions and as statistical regional groupings. Eventually, the regional dimension has developed at different paces to which the unclear roles and the diverse regional criteria in the UN system have clearly contributed.

Section two reviewed the recent reforms trying to strengthen regional participation inside the UN system as part of the many attempts to restructure the entire system. One of the most significant structural reforms has been the institution of the DPPA that allows regional organizations to work as interlocutors and to increase the interaction between institutionalized regional entities and UN bodies. Alongside this structural reform, upgrades in the partnership between UN and regional organizations have taken place in the development agenda. The complexity of the SGDs paved the way for a consistent and ambitious review of the UN development system that optimized the collaboration between different existing entities at the regional level and the UN development system.

Following the stocktaking exercise in the first two sections, a new typology was presented that goes beyond the earlier suggested distinction between electoral and operational regions. It allows us to position all major regional entities/expressions inside the UN system in a three-dimensional space. This new typology is useful to analyse the concrete regional action inside the UN realm as well as to assess the major inconsistencies inside this system. The three dimensions are the following:

- The roles played by regions inside the UN (political vs. operational);

- The status of regions/regional roles within the UN (formal vs. informal);

- The degree of institutionalization of regions outside of the UN (institutionalized vs. non-institutionalized).

It was shown how the ten different “regions” (or regional expressions) that were identified in the mapping could be positioned in this three-dimensional typological space, contributing to the definition of a more accurate ontology for the study of regions in the UN context and to the framing of the UN reform debates.

At the political level, our analysis also allows us to conclude that regional groupings linked to the UNGA and the UNSC display an international system which is not necessarily aligned with the reality of the new global world order. A new consensus is needed on a more representative, transparent, and accountable UNSC. This implies that a balance is struck between a more proportional representation across continents in tune with the global realities, on the one hand, and demography, on the other. Some flexibility might be created within the UN treaty through the conferral of additional powers on regional groups in the UNGA, or creating regional seats in the UNSC. Furthermore, the role of regional organizations in UN decision-making processes could go beyond the authorization of the UNSC, which would call for more bilateral partnerships with regional organizations on equal footing. But even without treaty change, partnerships could be institutionalized through multilateral platforms or bilateral agreements, so that more legitimate cooperation between the UN and regional organizations is further consolidated. Overall, strengthening partnerships between the UN and regional entities for which the latter diversify in their competencies and mandates of the member states should be an integral part of this new era of networked and multi-layered multilateralism.

At the operational level, the harmonization of statistical regions is desirable, considering the existing inconsistent and complex criteria in this regard. At the same time, the increasing use of e-platforms allows for more flexibility on the user end to aggregate data by regions. In view of an incrementally diversified and expanded UN system, streamlining its operations and institutions remains on top of the agenda.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This study was funded by the UNU-CRIS.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer KL declared a past affiliation with the author PDL to the handling editor.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^See its new “Strategic Concept” in “NATO Ministerial Communiques: Alliance Strategic Concept” (Agreed by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Rome on 7–8 November 1991).

2. ^Various accessions: in 1991 (Israel, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), in 1992 (Moldova, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia) and in 1993 (Macedonia, Monaco, Andorra, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, San Marino, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan).

3. ^ESCAP: four exogenous members (Britain, France, the Netherlands and the US); ECLAC: eight exogenous members (Britain, France, the Netherlands, the US, Canada, Italy, Portugal and Spain); ESCWA: African countries (Egypt and Sudan); ECE: most hybrid body of all (Israel, five Central Asian countries, Moldova and three Caucasian countries).

4. ^QCPR is the mechanism through which the UN General Assembly assesses ever four years the effectiveness, efficiency, coherence, and impact of UN operational activities for development and establishes system-wide policies and country-level modalities for development cooperation.

References

Bachmann, G., and Surasky, J. (2020). “Building momentum: the Decade of Action and Delivery and the UNDS regional reform,” in CEPEI, Why Member States Should Support the UN Regional Reform (Bogota: CEPEI), 21–27.

Behr, T., and Jokela, J. (2011). Regionalism and Global Governance: The Emerging Agenda. Notre Europe. Available online at: https://institutdelors.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/regionalism_globalgovernance_t.behr-j.jokela_ne_july2011_01.pdf (accessed September 17, 2023).

Berthelot, Y. (2004). “Unity and diversity of development: the regional commissions' experience,” in Unity and Diversity in Development Ideas: Perspectives from the UN Regional Commissions, ed. Y. Berthelot (Bloomington: Indiana University Press), 1–50.

Berthelot, Y., and Rayment, P. R. W. (2004). “The ECE: A bridge between East and West,” in Unity and Diversity in Development Ideas: Perspectives from the UN Regional Commissions, ed. Y. Berthelot (Bloomington: Indiana University Press),51–131.

Browne, S., and Weiss, T. G. (2013). “How Relevant Are the UN's Regional Commissions?”, in Briefing no. 1 of Future United Nations Development System. Available online at: https://www.futureun.org/media/archive1/briefings/FUNDS_Brief1.pdf (accessed September 17, 2023).

Cavaleri, E. (2014). “The Post-2015 UN Development Framework: Perspectives for Regional Involvement”. UNU-CRIS Working Papers. W-2014/12. Available online at: https://cris.unu.edu/sites/cris.unu.edu/files/W-2014-12.pdf (accessed September 17, 2023).

CEPEI (2019). A Sustainable Regional UN. Available online at: https://cepei.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/SustainableRegionalUN.pdf (accessed September 17, 2023).

CGC (1995). Our Global Neighborhood: The Report of the Commission on Global Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Daws, S. (1999). “The origins and development of UN electoral groups,” in What is Equitable Geographic Representation in the Twenty-first Century: Report of a seminar held by the International Peace Academy and the United Nations University, 26 March 1999, New York, USA (Tokyo: UNU), 11–29.

De Coning, C. (2017). Peace enforcement in Africa: doctrinal distinctions between the African union and United Nations. Contem. Secur. Policy. 3, 145–160. doi: 10.1080/13523260.2017.1283108

De Lombaerde, P., Baert, F., and Felício, T. (2012). The United Nations and the regions: third world report on regional integration. Sci. Bus. Media 3, 9. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-2751-9

De Lombaerde, P., Söderbaum, F., Van Langenhove, L., and Baert, F. (2010). The problem of comparison in comparative regionalism. Rev. Int. Stu.. 36, 731–753. doi: 10.1017/S0260210510000707

De Silva, L. (2004). “From ECAFE to ESCAP: pioneering a regional perspective,” in Unity and Diversity in Development Ideas, ed. Y. Berthelot (Bloomington: Indiana University Press), 132–167.

Destremau, B. (2004). “ESCWA: striving for regional integration,” in Unity and Diversity in Development Ideas: Perspectives from the UN Regional Commissions, ed Y. Berthelot (Bloomington: Indiana University Press), 307–357.

Deutch, J. D. (2020). “What are Friends for?: ‘Groups of Friends' and the UN System,” in Universal Rights Group. Available online at: https://www.universal-rights.org/blog/what-are-friends-for-groups-of-friends-and-the-un-system/ (accessed September 17, 2023).

ECLAC (2021a). “Methods and Classifications,” in CEPALSTAT. Available online at: http://estadisticas.cepal.org/cepalstat/WEB_CEPALSTAT/MetodosClasificaciones.asp?idioma=i (accessed April 19, 2023).

ECLAC (2021b). “Subregional Offices,” in UNECA. Available online at: https://www.uneca.org/subregional-offices (accessed April 19, 2023).

ECOSOC (1947). Economic Commission for Europe. Resolution E/RES/1947/36 (IV) of March 28, 1947. Geneva: ECOSOC.

ECOSOC (1948). Economic Commission for Latin America. Resolution E/RES/1948/106 (VI) of March 5, 1948. Geneva: ECOSOC.

ECOSOC (1958). Economic Commission for Africa. Resolution E/RES/1958/671A (XXV) of April 29, 1958. Geneva: ECOSOC.

ECOSOC (1973). Economic Commission for Western Asia. Resolution E/RES/1973/1818 (LV) of August 9, 1973. Geneva: ECOSOC.

ECOSOC (1984). Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Resolution E/RES/1984/67 of July 27, 1984. Geneva: ECOSOC.

ECOSOC (1985). Amendment of the Terms of Reference of the Economic Commission for Western Asia: Change of Name of the Commission. Resolution E/RES/1985/69 of July 26, 1985. Geneva: ECOSOC.

ECOSOC (1998a). Report of the Secretary-General on Regional Cooperation in the Economic, Social, and Related Fields. Resolution E/1998/65/Add.2. Geneva: ECOSOC.