94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 03 August 2023

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1213240

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Politics of Sustainable Development in Cultural PoliciesView all 7 articles

This study explores how urban cultural environments, and particularly their cultural provision and forms of participation, can foster cultural sustainability in urban communities, namely neighbourhoods. Conceptually, the article situates cultural sustainability within the concept of community resilience to facilitate an understanding of the everyday lives of residents and concerns residents' expectations of the cultural environment and opportunities for cultural participation in two case neighbourhoods in Jyväskylä Finland. Drawing on the mixed-methods approach of the study our findings show that different cultural activities and communities can be central to promoting sustainable urban development. Community resilience as a sense of belonging like neighbourhood-related identity and also as a sense of ownership of place seems strong in various ways, and relation to the cultural participation can be identified. However, from urban cultural policy perspective, the low-threshold participation and opportunities for grassroots cultural activity seem an underexploited resource in the cities, especially when the concept of sustainability is under consideration. Moreover, the negotiation and communication between community actors and public officials deserves a lot of attention while the implementation of urban cultural policy is on focus. From urban cultural policy perspective, it is important to find new ways to measure the direct and indirect impacts of policies. According to findings of the study holistic analysis of residents, actors and institutions viewpoints helps us to understand the practises and processes related to community resilience. All this deserves multidisciplinary research and joint reflection. This approach assists to make sense of how urban cultural policy and cultural participation can support community resilience at community level.

Nordic welfare societies are facing several global phenomena that threaten climate, safety, and social cohesion. Additionally, disparities between regions and different population groups as well as ongoing structural reforms challenge the resilience, i.e., the flexibility to change, of different actors, at different levels and sectors of society. Concomitantly, in recent decades discourses on sustainability have emphasised the essential role of local communities as frameworks for sustainability (Meadows et al., 1972; see also Putnam, 1995, 2000). Active communities formed by active citizens are argued to have a fundamental role in fostering change (Jeannotte, 2003; Jeannotte and Duxbury, 2015) and improving resilience (Callaghan and Colton, 2008; Sennett, 2018). Activity of communities helps to find solutions to societal challenges acknowledging shared perspectives, values, and principles. Community resilience has been found to provide a solid basis for genuine and sustainable partnership between the various sectors of society in general and in the cities in particular (Lekakis and Liddle, 2022; Van der Vaart, 2022).

Culture has historically been a constitutive force of urban development (UNESCO, 2016, p. 205). As the “'glue' of similarity that grounds our sociability” (Kong, 2009, p. 3), culture is an activity that provides opportunities for self-fulfilling and meaningful communal activities. The social dimension of cultural activities can be defined as a democratic function that enables social inclusion and fosters the development of community bonds (Kangas and Sokka, 2015) and strengthens inclusion in society (Jeannotte, 2003). Cultural activities and communities might be posited as central to promoting sustainable urban development (Jeannotte and Duxbury, 2015; Kyrönviita and Wallin, 2022). In this sense, and in response to the ongoing global phenomena, strengthening community resilience deserves more attention in urban cultural policy.

Goal 11 of UN Agenda 2030 is to make “cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable” (UN, 2015). This goal puts cities under growing pressure to withstand the realities of exceptional political instability, climate change, and the need to address the challenge the building of more inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable places to live (Quinn et al., 2022, p. 271). In Finland, too, cities and municipalities play an important role in building a sustainable future both locally and nationally (Ala-Mantila et al., 2022). At the same time, the pursuit of sustainable development in the municipalities should also work for the competitiveness, development, and attractiveness of the municipality in the coming years and decades (Kuntaliitto, 2021; Kestävä kaupunki, 2023; see also Agenda2030). Participation of active citizens as well as co-operation between various political institutions and actors from different sectors (i.e., widespread collaboration and participation) are defined as essential methods to reach the defined goals (Kuntaliitto, 2021). In the city of Jyväskylä, for instance, terms such as participation and inclusion occur as key words in strategic development (Luonila and Ruokolainen, 2023). Additionally, culture seems to play an important role in the city development (City of Jyväskylä, 2021a; Ruokolainen et al., 2019).

Thus, social sustainability, participation and inclusion are recognised to be essential for developing sustainable cities (see also Darlow, 1996; e.g., Alessandria, 2016; Ala-Mantila et al., 2022). However, as Jancovich and Stevenson (2023) argue, too often, when implementing strategies of social sustainability, the most meaningful questions about who frames the action, or who can take part in the processes of participation in general, are ignored. Additionally, cultural policy and urban governance are alleged to be too abstract and placeless without a fuller engagement and representation in situated contexts (Miles and Ebrey, 2017; Warren and Jones, 2018; see also Luonila and Ruokolainen, 2023).

We recognise the potential of arts and culture for stimulating the sustainable development of cities and the long-term development of suburbs (UNESCO, 2016; see also European Parliament, 2020). Our purpose here is to contribute to the literature on cultural sustainability by exploring how urban cultural environments, and particularly their cultural provision and forms of participation, can foster cultural sustainability in urban communities, namely neighbourhoods. The aim of the article is to advance discourses on how these culture-related viewpoints can be interpreted as ways to elaborate the current understanding of cultural sustainability in an urban context. Conceptually, the article situates cultural sustainability within the concept of community resilience to facilitate an understanding of the everyday lives of residents (Ebrey, 2016) and concerns residents' expectations of the cultural environment and opportunities for cultural participation in neighbourhoods. In other words, we adopt the broad definition of culture (e.g., Mercer, 2002) and see culture as grounded in the everyday lived experiences within communities and on the ideas of what is useful or enjoyable cultural life in the terms of these communities (Ebrey, 2016, p. 165). In this sense, the article extends the current literature on cultural sustainability and urban cultural policy by providing a context and community-specific lenses through which the relevance and potential of cultural participation as a fostering force of cultural sustainability can be analysed.

We select two suburbs, namely Huhtasuo and Keltinmäki from the city of Jyväskylä, Finland as the context for our analysis and pose the following research question: How do urban cultural policy and cultural participation build community resilience at community level?

The study is organised as follows. First, we describe the theoretical framework of the study, focusing on concepts of cultural sustainability and community resilience. Second, the methodological choices of the study are presented. The findings of the study are then discussed in two parts. First, we analyse the ways (urban) cultural policy supports cultural participation in urban neighbourhoods, and if so, how. Second, we focus on the strategic aims of the City of Jyväskylä and residents' cultural participation in the neighbourhoods and discuss at which levels the prerequisites and participation foster community resilience. Finally, the results are discussed and conclusions drawn in the final section.

Arts and culture have been highlighted as a vital and versatile resource for urban change and regeneration in cities and urban policy since the mid-1980s (e.g., Landry et al., 1996; Markusen and Gadwa, 2010) also influencing the urbanisation of cultural policy (Grodach, 2009, 2017). In the recent literature and policies on culture and cities, arts and culture are characterised as a context for citizens to participate in and contribute to the development of their communities (Matarasso, 1998; UNESCO, 2012, 2016). Additionally, studies have established the cross-administrative nature of culture in the development of cities (Hirvi-Ijäs et al., 2020; Mangset, 2020). Discourses of cultural policy in urban context have found to be intertwined with other policies such as social and economic policies, while the focus of policies has been found to vary in different areas of cities (see also Grodach and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2007; Bell and Orozco, 2021; Luonila and Ruokolainen, 2023).

In recent years the focus of urban cultural policy has transformed from building a creative city to achieving sustainable cities (Duxbury and Jeannotte, 2010; Duxbury et al., 2016); a trend that significantly influences urban cultural policy. Questions concerning the relation of culture and sustainability have received increasing attention among scholars, decision-makers and practitioners. Simultaneously, abstract and vague definitions as well as diverse use of both terms have caused a plethora of challenges in the development of theoretical conceptualizations (Soini and Birkeland, 2014; Soini and Dessein, 2016).

Soini and Dessein (2016, p. 166–167), aiming to clarify these vague terms and concepts, identified three roles of culture in the scientific discourses of cultural sustainability. These roles posit culture in sustainability, culture for sustainability and culture as sustainability. According to these authors, the first representation considers culture as if it had an independent role in sustainability. In this representation culture is considered capital and an achievement in development. In the second representation, culture for sustainability, culture is seen as a way of life. Culture is assigned a mediating role to achieve economic, social and ecological sustainability. Culture for sustainability suggests that both material and immaterial culture are seen as an essential resource for local and regional economic development. The third representation considers culture as semiosis and a necessary foundation for meeting the overall aims of sustainability considering development as a cultural process (Ibid). Duxbury et al. (2012) supplement the representations of culture as capital and a way of life with two further dimensions. According to these authors the meaning of culture should be recognised as an essential binding element providing the values emphasising sustainable (or unsustainable) activities. Additionally, they draw attention to understanding culture as a creative expression that provides insights on contemporary society, environmental/sustainability issues and concerns about our future (Duxbury et al., 2012), which is our focus in this study.

Undeniably, as Soini and Dessein (2016, p. 1) emphasise, it is crucial and required to explicitly integrate culture into the sustainability discourse, as achieving sustainability goals depend fundamentally on human accounts, actions and behaviour which are, in turn, culturally embedded (see also Mason and Turner, 2020). Culture is, as Mercer (2002, p. xviii) defines it, the “ways we behave, earn money, share experiences, live together, communicate and understand difference”. However, the “cultural dimension”, as Mercer argues (ibid), is often paramount but unrecognised beside the others, such as economic, social or environmental policies. Duxbury et al. (2017) share this viewpoint and propose four roles that cultural policy can play in achieving sustainable development. According to the authors, the role of cultural policy is to protect and sustain cultural practises and rights, “green” the processes and impacts of cultural organisations and industries, promote awareness and catalyse actions for sustainability and climate change and enhance “ecological citizenship”. However, as the authors put it, the challenge for cultural policy is how to assist, construct and guide the (cultural) actions in our society along these co-existing and overlapping strategic paths towards sustainable development (Duxbury et al., 2017, p. 214).

Indeed, the direction of the urban cultural policy discourse needs re-orientation from its somewhat economic-centric emphasis (see e.g., Grodach, 2017) in a more comprehensive, but also community and individual based direction to foster ecological citizenship in cities—as Duxbury and others call for (see e.g., 2017). To contextualise the roles of culture and cultural policy identified in sustainable discourse, cities in general and suburbs in particular can be identified as places that frame the role and meaning of culture in society in specific terms (Miles and Gibson, 2016). Additionally, this contextualisation assists us in analysing the interfaces between different illustrated representations and dimensions at community level in a real-life context. It also turns the focus onto how culture exists as a central binding element that provides the values underlying sustainable (or unsustainable) actions in communities (Duxbury et al., 2012, 2017 see also Preston and Gelman, 2020).

According to Ebrey (2016, p. 165), everyday life has been neglected in recent cultural policy discourses in four ways. Firstly, cultural policy is driven top-down by networks of experts rather than being grounded in the lived experiences of the everyday (see also de Graaf et al., 2015, p. 45–46). Secondly, culture has been instrumentalized for economic purposes to increase the attractiveness of cities. Thirdly, the “micro” and “macro” worlds of culture are rarely connected in a meaningful way. Fourthly, too much emphasis is put on individual choices of cultural consumption instead of focusing on communal forms and practises of culture.

In this article we capture Ebrey's critique and stress the meaning of the social dimensions of cultural activities for urban communities. The role of cultural activities in fostering inclusivity is becoming all the more relevant given the sustainability goals of cities (Quinn et al., 2022, p. 271). Concomitantly, culture and cultural participation are ways to generate platforms for resilient community that enhance opportunities to develop sustainability at community level in the case suburbs of the city of Jyväskylä.

Resilience can be considered in different contexts or levels. We can talk about the resilience of society, social-ecological systems, communities, or individuals, based on definitions of resilience from different disciplines (Brand and Jax, 2007; Lekakis and Liddle, 2022). Community resilience theories have focused on the transformation communities face after crisis or change, for example natural or economic shock (Shaw, 2012; Skerratt, 2013; Freshwater, 2015; Kumpulainen et al., 2022). However, there are tensions associated with the concept of community resilience, such as continuity and change, resistance and adaptation (Mulligan et al., 2016). Additionally, there has been lot of debate on local communities and their existence in postmodern societies because of people's weaker and overlapping commitments and globalisation (Mulligan, 2015). Simultaneously, in community theories the emphasis has shifted from community as social structure to focus on cultural and symbolic significance (Delanty, 2010; Mulligan, 2015).

According to Magis (2010), a resilient community means people having control over how to respond to the changes coming outside the community (Kumpulainen et al., 2022). Additionally, as Norris et al. (2008, p. 128) note, “people in communities are resilient together, not merely in similar ways”. The formation of community resilience does not take place from above, but through every day practises and interaction between people and communities (Kumpulainen et al., 2022). Thus, an active approach is the core values in the context of sustainable development. The need to adapt to change and actively participate in changes is highlighted, rather than to try to prevent changes coming from the outside. It also means not only the community's strength to adapt to external changes and threats, but also active and strategic agency in changing circumstances. In a simplified way, the resilient community is a strong and active community that is committed to a common goal, such as keeping its own neighbourhood safety and vibrant, but also sustainable. As Preston and Gelman (2020, p. 6) note, “we help targets that we feel connected to, that are a part of us, that we consider “ours,” and for which we feel responsible.”

To define community resilience, it is necessary to understand the nature of local communities (Mulligan et al., 2016). It is important to remember that nowadays local communities are just one community among others and do not bind community members as tightly as they use to. Postmodern communities are characterised by their members having some common interest that unites people. In local communities, this object is often the place itself, a village, or a neighbourhood. The cities talk about DIY urbanism, the fourth sector or urban activism (Mäenpää and Faehnle, 2021), community-led development and village activities in rural areas (Miles and Ebrey, 2017; Kumpulainen, 2018). The context of civil society and locality is about small communities, i.e., associations of neighbourhoods, residents and districts, or organised or non-organised actors operating locally. Alongside the various associations and local authorities there are third and fourth sector actors focusing on environmental protection, physical activity and sport or creative activities and the production of events, for instance. Thus, since the concepts of both community and resilience vary depending on the context (Mulligan et al., 2016), it is important how we define resilience and community in a certain study or policy discourse. Also, when studying community resilience in a city level, there are different stakeholders, roles and networks inside the city that influence the city transformation (Lekakis and Liddle, 2022).

Exploring communities' anatomy and mechanisms assists us in capturing the elements of community resilience. Being part of a local community also means belonging to the place and communication with other individuals connected to the place. In this study our definition of community is based on the cultural construction of a community even if we study local/place-based communities. We propose local communities here as cultural entities built on groups of people who share a common geographical locality (i.e., neighbourhood) and form a common social group and place-specific urban identity in everyday life (see also Delanty, 2003; Manzo and Perkins, 2006; Markusen and Gadwa, 2010). While communities are based on shared interests such as common places, ethnics, political interests or arts and culture, for instance, communication also means interaction and activity that assist bonding individuals to other members of the community. In this sense especially, culture societies can be seen as bridging ties between different groups and communities (Delanty, 2003).

In discussions on sustainable development, artistic and cultural activities have often been considered a kind of platform for action (cf. Dessein et al., 2015; culture for) or tool to increase awareness of the environment creating resonance for groups that traditional campaigning may not reach (Darlow, 1996). In urban cultural policy arts is on many occasions related to urban development aiming to develop nurture democracy and participation (Kortbek, 2019). Additionally, urban studies scholars have noted that residents are increasingly taking ownership of their environment through different forms of activism such as DIY projects (e.g., Stevenson, 2021; Kyrönviita and Wallin, 2022). Various forms of bottom-up urban projects emerging in suburbs can also be supported by public cultural policy. In terms of sustainability, however, culture needs to be understood more broadly as common values, attitudes and activities of the communities, which aim at a meaningful outcome for the community, i.e. as co-production, which calls on the community to work together on a shared interest (Stevenson, 2020).

Arts and culture provide opportunities for interaction and create meaning of life in places where they are produced and consumed (Landry et al., 1996). From the residents' perspectives in neighbourhoods, culture is a way to participate in meaningful communal activities (Luonila and Ruokolainen, 2023). Communal art forms such as theatre, cultural events and festivals are examples of how making, experiencing and consuming arts build bridges and bring together people from different backgrounds (see also Grodach, 2009; Lee, 2013). Participation also plays a key role in the sense of belonging to a community (Ma, 2021, p. 77, also Kim and Kaplan, 2004). At the practical level, participation in cultural activities builds social ties increasing communication between people there where action takes place (Crossick and Kaszynska, 2016; Daykin et al., 2020; Stevenson, 2021). Additionally, as Jeannotte (2003, p. 48) suggests, cultural participation assists in uniting individuals to social spaces occupied by others and encourages individuals to approve institutional rules and shared norms of behaviour.

According to the recent literature the most important feature of communities is sense of belonging (see e.g., Delanty, 2003; Mulligan, 2015). Here we understand belonging both in a symbolic sense of belonging and communication between people (Delanty, 2003, p. 4). Culture is a base for the sharing and meanings that form communities (Hannerz, 1992; Jeannotte, 2003) with cultural traditions, beliefs, values and fundamental convictions that constitute individual and collective identity within the limits of universal human rights (Kangas and Sokka, 2015, p. 141; see also Putnam, 1995). Culture is also a way to build communities by providing public cultural offerings, opportunities for grassroot activism and cultural participation (i.e. bridging). These activities are bridges to bond different actors creating a provision of sense of belonging among people (Putnam, 2000). Cultural sustainability comprises actions and issues that influence how communities manifest their identity, preserve and cultivate existing traditions and also develop belief systems and commonly accepted values (Kangas and Sokka, 2015). In this sense, culture is in a key position in developing resilient communities.

Figure 1 conceptualises the theoretical perspective of the study from the community resilience and cultural sustainability perspectives. The Figure concretizes the relations between the bridging role of urban cultural policy and bonding premise of cultural participation with the aim to enhance belonging in urban context.

Finland is a relatively egalitarian welfare society. It is one of the so-called Nordic welfare states (Sokka and Johannisson, 2022) with small-scale variation in income (OECD, 2020) and educational opportunities are equal (Heikkilä, 2021). In terms of population, Finland is small with over 5.5 million citizens (Statistics Finland, 2022), but occupies a large area, its territory covers 338 440 km2 (National Lands Survey of Finland, 2022). In Finland inequalities and social segregation within communities are relatively low (Stjernberg, 2019, p. 547; see also Bernelius and Vaattovaara, 2016). However, in the 2000s, urban residential segregation increased significantly, and since then, many governmental and local development programmes have been initiated to prevent and reduce residential segregation in the largest cities (Bernelius and Vaattovaara, 2016). The situation is still different from that in Sweden, for instance, where the residential segregation of suburbs, especially concerning ethnic groups, has led to polarisation and large-scale unrest in bigger cities (e.g., Dahlstedt and Ekholm, 2018).

From the cultural policy perspective, cultural policy structure in Finland composes a rather stable, organised, and institutionalised system for the implementation of public policy (Jakonen and Sokka, 2022). At national level the structure of Finnish cultural policy consists of multiple government institutions, quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisations and interest organisations. The Ministry of Education and Culture (MEC) is responsible for the statutory art and cultural policy (see e.g., Kangas, 2001; Luonila et al., 2022, p. 48; Jakonen and Sokka, 2022). The state allocates subsidies to municipalities to produce cultural services with the aim of achieving a decentralisation of cultural policy implementation at the municipal level (Kangas, 2001, p. 65–66).

With regard to allocated public support, the emphasis of funding is fairly well established. As in most other Western countries, in Finland, too, the majority of public funding to culture is channelled allocated to a rather small number of cultural actors operating in the so-called highbrow arts (Saukkonen, 2014). With respect to the democratisation of culture, the organisations funded are commonly theatres, orchestras, operas, museums and so forth in different areas and cities of the country (see e.g., Kangas, 2001; Saukkonen, 2014). Thus, the cultural policies are targeted at traditional kinds of arts and culture in Finland. In this respect, as Heikkilä (2021) mentions, the opportunity for cultural consumption (i.e., participation) is offered to be privileged or culturally active groups, even though the cultural consumption also happens outside the institutions (Purhonen et al., 2014). It is also argued that the funding frame challenges the idea of equal opportunity to participate and consume culture (Heikkilä, 2021), one of the purposes at which “welfare state's cultural policy should aim” (Kangas, 2001, p. 62).

As Virolainen (2014) notes, cultural participation has been a key aspect of cultural policy since the introduction of modern cultural policies in the 1960s and 1970s in general and in Finland in particular (see also e.g., Jancovich and Bianchini, 2013; Heikkilä and Lindblom, 2022). Moreover, as Kangas (2001, p. 62) mentions, since the 1970s Finnish cultural policy has focused on the idea that cultural policy should contribute to a process of equalisation among various social groups and avoid the wide discrepancy of opportunities for the consumption of culture. Even though the promotion of equality is a central aim in Finland's cultural policy (Kangas and Sokka, 2015, p. 143), interestingly, in recent studies Heikkilä and Lindblom (2022) note that more than two-thirds of all Finns never attend the operas or jazz concerts that are commonly publicly funded arts genres (cf. Van Hek and Kraaykamp, 2013), whereas almost everyone goes to the cinema at least sometimes, a leisure activity that is commonly driven by a commercial operator. Moreover, it must be noted that in Finland community citizenship has a long and strong tradition in society. Various associations and communities are a key resource and a functional platform for democracy and wellbeing as well as activating citizens in Finnish society, including culture (e.g., Ruuskanen et al., 2020).

Thus, leisure and cultural offerings, cultural consumption as well as overall participation in culture is a multilevel construction that relates to the institutional highbrow art structures, low-threshold participation in the events or festivals or grassroot do-it-yourself activities, for instance (Purhonen et al., 2014; Heikkilä and Lindblom, 2022). In this sense, according to current trends, “cultural participation remains a highly stratified and polarised field, also in an egalitarian society” such as Finland (Heikkilä, 2021, p. 202). As a reflection to these definitions, we take cultural activity here to cover various local communal activities related to leisure.

The city of Jyväskylä is located in the middle of Finland. In our research period, Jyväskylä was the seventh biggest city in Finland in 2020 with 143,420 citizens (Statistics Finland, 2022). One of the key characteristics of the city is higher education and students: there are a research-based university and two universities of applied sciences with ~23,000 students. The strategic vision of the city is to be a “growing and internationally recognised city of education and expertise” aiming to make Jyväskylä “the best place to live, work and study” (City of Jyväskylä, 2021a).

The main public funded arts institutions, such as the city theatre and orchestra as well as Museum of Central Finland, the Art Museum, the Arts and Crafts Museum and the Alvar Aalto Museum are located in the city centre or in its immediate vicinity. In the Jyväskylä there are also a comprehensive network of libraries. The 13 public libraries are located at different locations as our case neighbourhoods.

Regarding the suburbs, they are well established and form a significant part of the urban structure of everyday life in all Finnish cities. Suburbs are residential areas from a certain era, namely the 1960s or 1970s, following a uniform plan and located outside the city centre in peripheral surroundings on urban fringes based on the model of a forest city and the grid layout of so-called compact estates, the building stock consisting mainly of element concrete apartment houses (Kemppainen, 2017; Stjernberg, 2019). At the time of the construction, the suburbs with their modern apartment blocks exemplified progressive urban planning and the houses provided the very latest modern conveniences to tens of thousands of new urban citizens and their families. Later, however, the image of urban Finnish suburbs changed. Due to the recession of the 1990s, high unemployment and poverty emerged. The 1990s also witnessed growth in immigrant populations and the construction of social housing. In the 2000s, many suburbs became disadvantaged in socio-economic terms and underwent significant demographic changes that led to residential segregation by income or ethnicity (Hyötyläinen, 2019; Stjernberg, 2019).

Our study focuses on the suburbs of Huhtasuo and the Keltinmäki-Myllyjärvi located in different parts of the city of Jyväskylä, about 3–8 km from the city centre. In 2020, they were home to over 16 000 inhabitants (City of Jyväskylä, 2022). Both suburbs have good infrastructure and public services. At their centres they have shopping areas (like the Huhtasuo Shopping Centre) with grocery stores, public services provided by the City of Jyväskylä such as public health clinics and public libraries and some private and third-sector services. In addition, there are Evangelical Lutheran Church premises, and primary and comprehensive schools. The public transport connexions are good, providing easy access from there to the city centre. Both suburbs are ethnically and socially diverse, have high unemployment figures, low levels of education and high levels of families headed by a single mother living in certain residential areas. There are also some major differences: the population of Huhtasuo is currently on the increase, and this has driven considerable investment in developing the area with new housing constructions, including detached houses, and with several public urban development planning projects. In Keltinmäki-Myllyjärvi, the population is diminishing (City of Jyväskylä, 2022), and no major investments have emerged.

This study draws on the data gathered during the research project “Forms and meanings of culture in the 2020′s suburbs: two case studies from Jyväskylä” (University of Jyväskylä 2021–2022). The project scrutinised cultural activities in two suburbs of the city of Jyväskylä (in Central Finland). During the project we used a mixed-methods approach and gathered research materials by doing ethnographic field work (interviews with social experts and participant observation), conducting a survey in the two case neighbourhoods, organised participatory workshops for special interest groups and read cultural policy documents with the aim to analyse the prerequisites of cultural policy (Figure 2).

The aim of the data collection was to consider two aspects: the cultural and experienced perspective (inhabitants) and the functional aspects (key person interviews). While the survey sought the same overview of leisure activities in the regions, the purpose of the workshops, interviews with key persons and ethnographic observation was to provide background information on community actors and everyday life in the residential areas and supplement the information collected through quantitative methods (integrating of different methods in mixed methods research see Moran-Ellis et al., 2006; Hammersley, 2008). We received a total of 189 responses via the survey, of which some respondents were current residents, some had been living in the neighbourhoods earlier and some were visitors in the areas.

In this study we report the responses of residents currently living in the neighbourhoods (n = 164). Vast majority of this group were women (70%). 40% of the residents responding were currently working, 24% were pensioners and 18% were unemployed. The respondents were able to choose several different labour market positions.

The ethnographic data we use here consists of 14 thematic interviews with the 22 informants (see Table 1). In addition, we gathered data from participatory workshops and conducted observation and kept research diaries in the case neighbourhoods. We studied the organising of and participation in the activities, asking what kinds of activities were important and meaningful for the residents of the suburbs.

Additionally, we have analysed the cultural policy documents of the City of Jyväskylä to find out how policy measures address the cultural activities of the suburbs. The aim of the analysis was to study the role of activities organised by the inhabitants and communities of the suburbs and to determine the role of the activities by organised by public cultural institutions such as the City of Jyväskylä. In so doing, we approached the cultural environment both from the perspective of publicly funded offerings, activities produced by civil society and grassroot activities created by the inhabitants, whereas the context (i.e., place) of the study was the two case neighbourhoods in the city of Jyväskylä, Finland. Simultaneously, we analysed the public funding decisions concerning cultural and citizen activity grants made by the city's councils and also established an overall view on the city's cultural funding as a whole. Regarding to this particular study, we analysed how the prerequisites reflect to our understanding of community resilience.

Thus, we opted for a mixed-methods approach as this is often effective when exploring wide and complex social issues and global challenges that can be seen as so-called wicked problems which cross disciplinary boundaries (see Seppänen-Järvelä et al., 2019). Sustainable urban development and social sustainability is one such problem (Ala-Mantila et al., 2022). Resulting from our research, we found connexions between cultural participation and the concept of resilience as well as sustainability (the focus of current study) as an emerging finding (Figure 2).

Next, we will discuss the findings of the study in two parts. First, basing on the strategic goals and values as well as funding and channelled resources we analyse the ways (urban) cultural policy supports cultural participation in urban neighbourhoods. Second, we focus on the strategic aims of the City of Jyväskylä and residents' cultural participation in the neighbourhoods and discuss from the cultural and experienced perspective (inhabitants) and the functional aspects (key person interviews) at which levels the prerequisites and participation foster community resilience (see also Figures 1, 2).

Here we focus on how urban cultural policy appears as an enabler of community resilience and brings together disparate members of the community i.e., building bridges between different actors (Putnam, 2000). First, we discuss the strategic will of the city then analyse the resources enabling activities in the case neighbourhoods.

The strategic vision of the City of Jyväskylä (2021a) is to be a “growing and internationally recognised city of education and expertise” aiming to make Jyväskylä “the best place to live, work and study”. The city has defined four strategic goals, namely (1) happy, healthy and participatory citizens, (2) fresh, growth-oriented business policy, (3) wise use of resources and (4) to be the capital of sport and physical activity in Finland following the four strategic values of responsibility, trust, creativity and openness to achieve these targets.

In the measures to achieve the goals of having “happy, healthy and participatory citizens”, the strategy underlines opportunities for children and young people to enjoy healthy growth and learn successfully, opportunities to influence decision-making, the promotion of equality, the availability and accessibility of services, a strong sense of community with the aim of reducing loneliness by multifaceted leisure activities, arts and culture (City of Jyväskylä, 2021a; see also Luonila and Ruokolainen, 2023).

Other strategic documents support the vision and targets of the city strategy. The focus of these documents is on the wellbeing and inclusion of residents with supporting participation and on creating ways to influence local decision-making and on the other hand, to make the policies and culture of the city more transparent and inclusive. Regarding children and adolescents, the focus of the Cultural Plan of the city, for instance, is on active self-motivated cultural activities by making culture a part of everyday life by “hands-on” means (City of Jyväskylä, 2021b).

In their critical reading of the strategic texts of the city of Jyväskylä, Luonila and Ruokolainen (2023) note that at strategy level the city of Jyväskylä targets cultural policy measures in the suburbs in relation to citizens' activities in different ways. According to the authors, the documents discuss community, participation, inclusion and voluntary activities and link these activities to the operations in community centres (‘kylätoimistot') and mention them as optional places to produce events and as contexts to implement various development projects in the suburbs (City of Jyväskylä, 2021c; Luonila and Ruokolainen, 2023). From the community resilience point of view in the texts the Wellbeing for Huhtasuo project is cited as an example aiming to create new opportunities and inclusive procedures for residents in suburbs to enhance self-motivated activities to support citizens' wellbeing and to foster collaboration between different suburban actors. Concomitantly, from the prerequisite perspective, the strategy texts mention the libraries as places to promote equality (e.g., City of Jyväskylä, 2021d). Beside the activities produced by community centres, the strategic aim of the city is to use libraries as a platform to motivate volunteers to come up with ideas and co-operate in staging events and a variety of other activities, for instance.

In the Cultural Plan, the City of Jyväskylä makes an actual attempt to connect cultural activities to the strategic goals of participation and inclusion. The Cultural Plan outlines an idea to enable grassroots activities in the suburbs aiming to expand the cultural activities beyond the existing cultural institutions and beyond the city centre. The strategic purpose is to reinforce cultural activities in the neighbourhoods and near bring together residents of neighbourhoods by producing pop-up activities and digital applications (City of Jyväskylä, 2021b). The objective of cultural activities by streaming concerts, lectures and other events. Local libraries, for example those in Huhtasuo and Keltinmäki, are seen as places to provide such cultural content for residents' activities (see also Luonila and Ruokolainen, 2023).

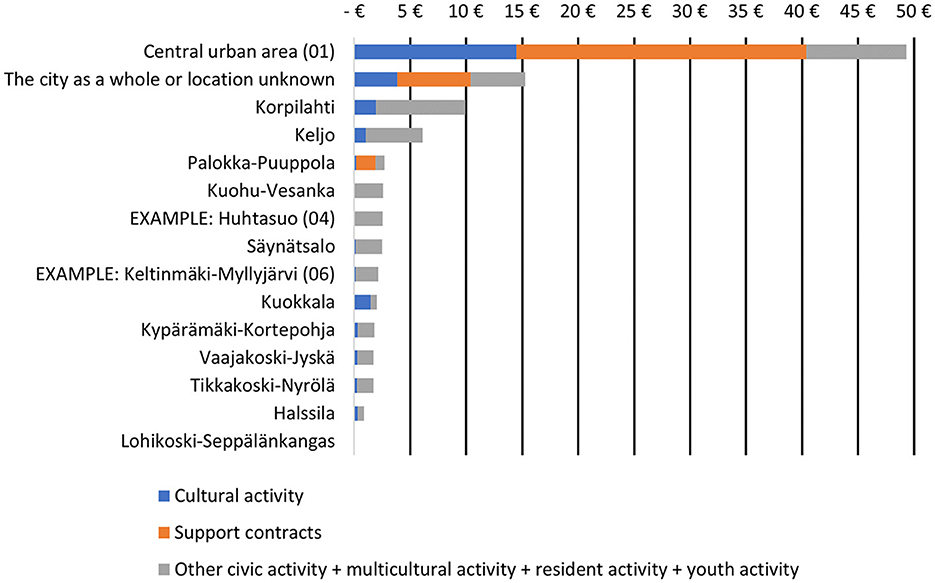

According to the funding documents, the public expenditure on culture was 32.4 million euros in 2020 (or a total of 123.3 million euros from 2017 to 2020). The expenditure on culture is heavily concentrated to the city centre or the statistical wide area 01. In this location Jyväskylä City Theatre received 5.8 million euros of funding in 2020 (or 22.4 million euros in total during the period 2017–2020) and the symphony orchestra of the city (Jyväskylä Sinfonia) approximately 3.2 million euros (or a total of 12.2 million euros during the period 2017–2020). They also receive public funding from the cultural administration of central government.

However, the City of Jyväskylä—through its culture and sports as well as its education committee – also makes grants to smaller art and culture actors. For example, in 2020 this funding was approximately 91,000 euros, or in total 0.55 million euros from 2017 to 2020. The city and the committees also agree on support contracts with some middle-sized cultural organisations, which received 0.3 million euros in 2020, or a total of 0.94 million euros from 2017 to 2020. Most of the cultural activities obtaining grants from the Culture and Sports Committee are located in wide area 01, i.e., the city centre. The funding for cultural activity was 0.44 million euros or 14.5 euros per capita in wide area 01 for the period 2017–2020. In addition to this, almost all the so-called support contracts for medium-sized cultural organisations were also allocated there. This funding amounted to 0.79 million euros or 25.9 euros per capita in the years 2017–2020. At the same time, Huhtasuo, in wide area 04, received only 0.05 euros per capita and Keltinmäki-Myllyjärvi, wide area 06, received 0.15 euros.

The city committees also allocate funding to various other activities, namely “other residents' activity”, “multicultural activity”, “residents' or civic activity” and “youth activity”. This funding helps to analyse the role of grassroots cultural and civic activity more broadly. Grants for civic activity are allocated more evenly across the whole city. Wide area 01 received 0.27 million euros or 8.91 euros per capita. Huhtasuo in wide area 04 received 2.49 euros per capita while Keltinmäki-Myllyjärvi in wide area 06 received 2 euros per capita. There were also forms of activity located in the city as a whole receiving 0.2 million euros or 4.86 euros of funding per capita.

To sum up, the different parts of the city are relatively well balanced with regard to grants for various civic activities. However, the actual funding for culture is heavily concentrated in the city centre (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Total allocation of per capita grants to arts and culture and civic activity in the wide areas of Jyväskylä in the period 2017–2020 (31 December 2020) (see also Luonila and Ruokolainen, 2023).

Beside this funding there have been several development projects in the suburbs aiming to cultivate community spirit as well. In Huhtasuo, these project activities (Ihmisten ilmoille project 2018–2020) have aimed to strengthen the active participation of local residents and thereby increase community activities as one interviewee described the nature of the project:

“It developed volunteer activities for this area, and it was based on the fact that we don't have a ready-made concept for where to recruit people, but we think about what people's strengths are and what they want to share with others, and what kind of interest there is in doing leisure activities and something for everyone so that no one is turned away.” (Interview 1)

Cultural participation builds bridges, bonds different actors and creates a sense of belonging among citizens (Putnam, 2000; Putnam and Goss, 2002), which means that cultural participation also plays a key role in building community resilience. Here we analyse how the residents of the neighbourhoods participate in local cultural and community activities.

The significant element for building community spirit and bonding are various indoor and outdoor places enabling people to gather, meet and act together. Community centres and parish facilities are mentioned both in the survey and in the interviews as significant meeting places. In particular, their role in building inclusion and community for lonely people is seen as important.

“Community and participation are also about coming here to spend time together with other people from the area. Here you meet a lot of people who may sit next to each other on the bus and never, you know, say—to each other, but they come here and eat lunch at the same time and talk about it.” (Interview 4)

The publicly funded cultural environment in the case suburbs is based on public libraries as well as an active third sector (see also Table 1). The main places for community activities of the suburbs of Huhtasuo and Keltinmäki-Myllyjärvi are the residents' associations' facilities (local people refer to them literally as “community centres”—in Finnish Kylätoimisto/Kylätalo) which have long histories, and a more recent City of Jyväskylä community activity centre (in Finnish yhteistoimintapiste) that hosts various public services and has spaces which can be booked for third sector social activities. These are so-called low threshold meeting places which offer social connexions and interaction and promote community ties and social inclusivity for suburban residents. The activities organised in these places are free of charge, so a poor economic situation does not prevent people from joining in these activities, and most of them are organised via voluntary work.

The local (CSO/NGO) experts operating in these spaces whom we interviewed (see Table 1) stated that public community facilities offer everyday social interaction and organised activities which bring together actors from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Most communal community activities, such as playing bingo and singing karaoke, take place in day-time, and the residents can also use the space for individual activities such as reading newspapers and magazines, see art exhibits, do handicrafts and drink coffee and tea. These shared places offer activities specially targeted at elderly, lonely and unemployed residents. The local community centres also are also involved in third-sector and public community development projects, which empower and inspire residents through specific project activities and public lectures.

The social experts we interviewed stressed the importance of a space open to all where the residents can both spend time and be together, and that can support different kinds of social activities and spontaneous gatherings. In 2020, the City of Jyväskylä closed a day centre for the elderly in the area of Huhtasuo (Huhtasuon päiväkeskus), and later opened a multi-purpose service centre (Huhtasuon yhteistoimintapiste) that can be booked by NGOs and various groups on an hourly basis. The place hosts local public services such as employment guidance, family centre and youth work outreach, which are open only during certain office hours.

“It comes to mind that people get support for their own activities and activities, so people are active and enthusiastic and creative. There's a lot of resources and a lot of desire to do that…sometimes they need support and some kind of frame. We've seen middle-aged people in our operations and they've gone over it. It reminds me of the people I've met, so when they got that place, and we were there and said, “Don't come along, then they came like they did, and they were really active, excited, and it was really meaningful. It needs something, because there is exclusion and challenges in its own life and ability to function, so it does not necessarily leave without that support.” (Interview 4)

“It would be great if the hobby were also seen that it is not just for me, but that it can be arranged as a shared pleasure. It has so much reciprocity or an intense thing to do during that week or you can prepare something…Even if you're at the music club and you take it to some park party. I think it's more than just the wellbeing that's given to me.” (Interview 3)

According to the interviewees, cultural activities have the clear effect of increasing wellbeing and active participation. At the same time, the need for support was emphasised, so that people are encouraged to participate and organise activities that interest them.

“Something like that comes to mind, that if people get support for their own activities and agency, then people are active and enthusiastic and creative. People there have a lot of resources and a desire to do something. Somehow, they need support and some kind of frame for it.” (Interview 4)

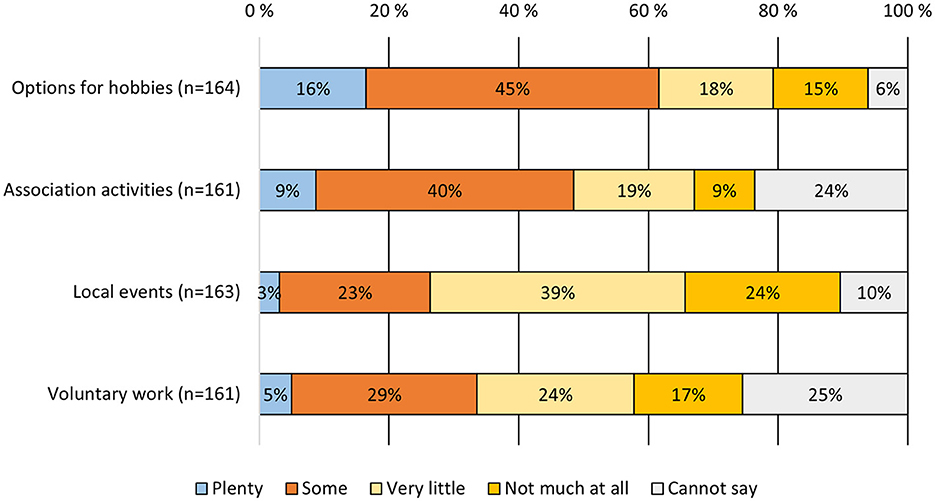

The workshop data support this finding but provides another interesting angle. Even though there are different kind of groups with different needs, various bottom-up activities for different kind of groups are organised. Additionally in the conducted survey residents were asked about their views on how many different kinds of activities are available in the neighbourhoods (Figure 4). The majority of the residents (61%) felt that there were either plenty or some options for hobbies in their neighbourhood. In both areas, 49% of the residents responded that there were plenty or some association activities available. On the other hand, both neighbourhoods seemed to lack local events relative to other options; around a quarter of the residents found there to be plenty or some local events. Thirty-four per cent responded that there was either plenty or a certain number of voluntary work available in the area. Residents seemed to be least aware of the options in the neighbourhood for association activities and voluntary work—the share of residents responding “cannot say” was approximately a quarter to questions about association activities and voluntary work.

Figure 4. The availability of hobbies, association activities, events and voluntary work in the areas according to the survey results.

When asked about their hobbies and activities in the neighbourhoods and where those activities took place, residents mentioned many different places located both indoors and outdoors (Figure 5). The places are maintained by several different actors operating in the area. Interestingly, nature was mentioned as important place as well: both as a value but also as a concrete space for cultural activity and natural places like forests, campfire places and jogging tracks were mentioned remarkably often. Thus, according to the residents, nature can also be a cultural state and “heighten awareness of the surrounding environment and develop a ‘sense of place' and oneness with nature” (Darlow, 1996, p. 295). Additionally, as Preston and Gelman (2020) have found, the positive memories and experiences, in a natural area, as culture participation in our case, foster psychological ownership of the place and foster the willingness to protect the place.

The second basic element of community resilience, bonding, means interaction and communication with other residents in the neighbourhood. Communication strengthens community resilience especially because it increases interaction and understanding between different groups (Delanty, 2003). As informants in the interviews and survey described:

“When there are different people here, differences are tolerated here and there is a bit of a village-like community here and a mood of doing things together. It's really nice.” (Interview 4)

“Since Huhtasuo is a culturally rich region, it would be nice if there was a space where people from different cultures could open up a little about their own culture to those who are interested in the matter and to people who have questions, because we have noticed that there are still people who think differently, especially in this area.” (Survey, Huhtasuo)

Cultural and leisure activities are seen as a community and also communicative resource that brings people together (e.g., Kangas and Sokka, 2015), especially those who may not otherwise interact with each other, such as immigrants and other residents (cf. Lilius, 2016). One interviewee concretised this as a common activity:

“It would be great if hobbying could also be seen, that it is not just for me, but that through hobbying, it can be organised as a shared joy. There's that kind of reciprocity, or there's an intensive thing to be done during that week, or you can prepare something, like a performance at a music club, and you take it somewhere to a park party. I think that doing something is more than just the wellbeing you get for yourself.” (Interview 3)

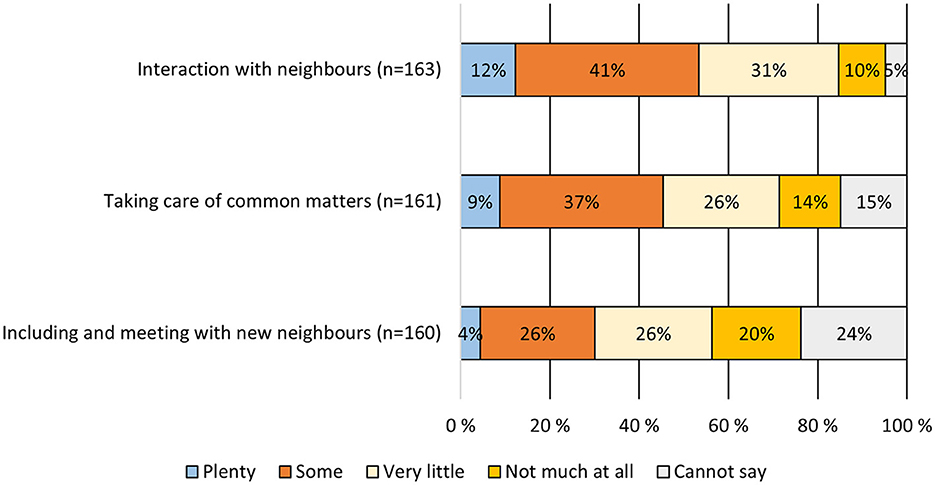

In the survey conducted over half of the residents (53%) responded that there was plenty or sufficient interaction with neighbours in the areas. On the other hand, less than a third of residents felt that new neighbours were included and met with in the area (30%), whereas almost half felt that there was very little or not much inclusion of and meeting with new neighbours (46%). Forty-six per cent thought that plenty or adequate care was taken of common issues in the area (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. The amount of interaction with neighbours, taking care of common matters and including and meeting with new neighbours according to the survey results.

Social media enables local social interaction and also information on current affairs on digital platforms. Keltinmäki did not have its own Facebook group at the time of the research, but Huhtasuo had an active social media channel “puskaradio = grapevine” on Facebook. In the survey we asked the residents how much communication via social media there was regarding the areas. Thirty-nine per cent reported that there was plenty or some communication via social media, whereas 41% reported that there was very little or no communication via such channels. Social media as a channel for interaction also received criticism from the informants—both residents and social expert interviews—especially because the FB channel was not moderated:

“I can't say, I don't participate in anything. There is no information about the events, Facebook's “Puskaradio Huhtasuo” is a trolling channel founded by middle schoolers with a battery, where nothing is taken seriously.” (Survey, Huhtasuo)

“After all, there are a lot of people here who generally use WhatsApp groups and trash radio. Here is Huhtasuo's own Facebook, there the conversation can be very wild. It is not always about raising community spirit but can be in the other direction as well.” (Interview 1)

While social media and digitization unite some residents, it also marginalises others. For example, a large part of the elderly and immigrant residents are excluded from these discussions. Residents' associations and project workers have recognised this challenge; information on digital channels does not reach everyone.

Thus, community resilience is built from the basic elements of community, namely bonding and belonging. Community spirit, for instance, is a significant factor that increases residents' attachment to their place of residence (Kim and Kaplan, 2004). In addition, memories related to places are also significant in terms of attachment to the community (Rishbeth and Powell, 2013; Lewicka, 2014). In this study, we examine belonging from the point of view of belonging to a place and to other people living in the neighbourhood, local identity. Becoming attached to a place of residence depends on how much you enjoy being there.

To map the concrete manifestations of community in the case neighbourhoods' questions concerning community spirit and identity were asked in the interviews with social experts and in the survey. According to the survey, 47% of the residents reported that there was some or sufficient community spirit, but 38% thought the opposite, that there was very little or none. The answers reflect the subjectivity of the community experience, i.e., there was wide variation in the responses Some on the inhabitants' experience was that there was ample community spirit, but some thought there was not much, with most responses somewhere in between. In the section of the survey inviting comments in residents' own words, the informants were asked to mention those forms of community activity that did not appear in the ready-made classification. There, the activities of the parish and village halls came up, which were not mentioned separately in the survey.

In the interviews with key informants, community spirit was also discussed. All the interviewees felt that there was community spirit in the suburbs, which can be seen, for example, in neighbourly help (cf. Junnilainen, 2019), as one informant mentioned:

“Here you can see the sense of community, and the “help a friend” mentality. There are also a lot of people here who have lived here since the 1970s, so you know them from a long time, for both good and bad.” (Interview 1)

Regarding identity, according to the survey, the strength of residents' local identity varies. More than half of the residents felt that they had either quite strong or very strong identities related to their suburbs. Only six percent in Huhtasuo and five percent in Keltinmäki answered that they did not feel local at all. The responses of the interviews were similar:

“You asked about Huhtasuo, so I think there is a Huhtasuo identity. Many young people who have grown up there, they want to live there. There might be the fact that when you go to visit a childhood home, yes, my mother lives there and my brother lives in the apartment building next to it. Those communities are born there, but on the other hand, problems are inherited. Yes, there is the transfer of problems from the same generations.” (Interview 11)

Junnilainen (2019, p. 93–94) has also observed the transgenerational nature of identity when studying Finnish neighbourhoods. The local identity affects the experience of community. Long-term residents often feel a stronger attachment to the place and participate more actively in common activities (Toruńczyk-Ruiz with neighbours in the areas Toruńczyk-Ruiz and Martinović, 2020). Young people are also attached to the suburbs as one interviewee put it:

“I feel that they [young people] are very attached to this area. Over the years, you also see those young people who go out into the world, and quite a few come back.” (Interview 5)

Thus, living environments influence the shaping of people's lives. Especially for young people, suburbs act as one of the tools and social capital for young people's identity construction (Van Aerschot and Salminen, 2018), as one interviewee put it:

“Perhaps I could say that I don't feel at all that young people are ashamed of it (Huhtasuo). Young people are used to that mood. Sometimes they maybe make fun of what is goings-on in Huhtasuo, but they are somehow... there is something similar about it–its own Ghetto. Yes, it's a street-credible place.” (Interviewee 11)

Questions regarding happiness in and identifying with the neighbourhoods were also included in the survey. When asked how happy the residents felt in their respective areas, 68% reported feeling either very or quite happy. Similarly, 65% of the residents identified with their neighbourhood either very strongly or quite strongly (Figure 7). Six per cent of the residents did not feel happy at all in the area or felt very little happiness, and 16% did not identify with their neighbourhood or identified with the area only a little.

While the residents were asked about the extent to which they identified with their neighbourhoods, it was observed that those who took part in organising cultural activities and developing their neighbourhood also identified with the area. Of those who had participated in organising and developing activities, 71% identified with the neighbourhood either strongly or very strongly, whereas 60% of those who did not take part in those activities reported experiencing a strong or very strong neighbourhood identity. Twenty-four per cent of the non-participants identified with the neighbourhood only a little or not at all, while among the participating residents this share was only 7%. Thus, participating in culture-related activities is connected to a stronger sense of belonging and bonding to the place and to the community (see Figure 8).

The aim of the study was to extend the literature on cultural sustainability and urban cultural policy by providing a context and community-specific lenses through which the relevance and potential of cultural participation as a fostering force of cultural sustainability can be analysed. The purpose has been to contribute to the literature on cultural sustainability and explore how urban cultural environments, and particularly their cultural provision and forms of participation, can foster cultural sustainability in urban communities, namely neighbourhoods. Conceptually, we situated our study on cultural sustainability within the concept of community resilience to facilitate an understanding of residents' everyday lives (Ebrey, 2016). We selected two suburbs, namely Huhtasuo and Keltinmäki in Jyväskylä, Finland as the context for our analysis and asked: How urban cultural policy and cultural participation build community resilience at community level? We analysed the ways how (urban) cultural policy supports cultural participation in urban neighbourhoods and, if so, how. We focused on the strategic aims of the City of Jyväskylä and residents' cultural participation in the neighbourhoods and discussed at which levels the prerequisites and participation foster community resilience.

According to our findings culture is given an important role in capturing the social and economic strategic aims in the city of Jyväskylä. From a strategic perspective, the city aims to develop a city for “happy, healthy and participatory citizens” (City of Jyväskylä, 2021a). Viewing this from our theoretical framework, the city's solution is to use cultural offerings and cultural participation as a bridge to enhance its residents' wellbeing by providing opportunities for participation and hobbies for all, but also by creating ways to influence local decision-making (City of Jyväskylä, 2021c). In the strategies, self-motivated cultural activities are also apparent, while one of the key premises is to support self-motivated cultural activities by enabling grassroots activities in the suburbs to expand the cultural activities beyond the existing cultural institutions, and beyond the city centre and make culture a part of everyday life by “hands-on” means (see also Luonila and Ruokolainen, 2023). From the bridging perspective in both case neighbourhoods the local library was deemed important while other publicly funded cultural pursuits mostly take place elsewhere in the city. In the case neighbourhoods there were many associations run by civil society that generate opportunities for (cultural) participation and sports as a hobby were emphasised. However, the resources allocated to these actors are minor and the facilities unstable.

Regarding the case neighbourhoods as communities, in spite of various socio-economic challenges residents reportedly spend a lot of time in their own areas and seem happy there. Community resilience as a sense of belonging like neighbourhood-related identity and also as a sense of ownership of place seems strong in various ways (see Figure 7). Our results show that local meeting places like natural venues and buildings as well as offered services are important for citizens and these elements of everyday life need to be preserved and their stability ensured. Neighbourhood associations and other NGOs produced activities in the case neighbourhoods with community-based low-threshold activities, such as cultural and leisure activities and various events that create opportunities for communication. In this sense, the role of village halls, residents' associations and other actors from the third and fourth sectors as key supporters of community and community resilience is emphasised.

However, as Junnilainen (2019) has found, the mutual social ties of people living in the urban neighbourhoods are often tenuous and temporary. They are, for example, related to a certain life situation, but are still significant in that they provide peer support and everyday security (cf. Van Aerschot et al., 2016). Our results show that in our case neighbourhoods there are different manifestations of community and community spirit in the neighbourhoods studied, although experiencing community is highly subjective. The role of development projects and residents' associations in building community spirit and connecting individuals and groups is significant. The main task in projects and in community centres activities strengthening the community is to prevent exclusion, loneliness and social problems. In project activities and residents' associations, the exclusion-preventing and empowering effect of communal activities is especially emphasised. Still, our results support Junnilainen's observations. For example, encounters in village halls or common events are not necessarily profound human relationships, but nevertheless significant everyday encounters affording relief from loneliness. Thus, it can be said that key factors and prerequisites for community resilience can be found in the suburban neighbourhoods, such as belonging and bonding. Yet when compared to community development in different areas such as rural regions, for instance, the picture is rather different. In rural village associations the future orientation through village planning and developing local services is a relevant part of community action, for instance (Matthies et al., 2011).

In our case neighbourhoods, there are multiple inputs to social cohesion or sustainable societies and many times government policies represent only one set of these inputs (Jeannotte, 2003, p. 47). Our findings are in line with Duxbury et al. (2017), that culture should be recognised as an essential binding element providing the values emphasising sustainable (or unsustainable) activities. Basing on our results we are able to elaborate this and state that cultural activities are a way to enhance community resilience in neighbourhoods as well: bridging urban cultural policy can enhance public cultural offerings, opportunities for grassroots activism and cultural participation, whereas (cultural) participation fosters communication (i.e. bonding) in the everyday life context (see also Jeannotte and Duxbury, 2015). These factors support social cohesion in communities among residents and other actors in local communities generating a sense of community and belonging, and especially of ownership of place. These are key elements of resilient community where shared community-related interests bring residents together.

Concerning urban policy making, we propose that resilient community should be understood as a goal that assists decision-makers in the cities and communities to enhance (cultural) sustainability (Throsby, 1995; cf. Soini and Dessein, 2016). Practically, when the societal aim is to generate socially and culturally sustainable neighbourhoods, participation in everyday (cultural) activities might be seen as a valuable way to gather information about community values, practises and priorities using a wide variety of community engagement techniques. In the same vein, cultural participation as an activity generates wellbeing and meaning in life, and as a vehicle to foster active agency in urban neighbourhoods creates a sense of ownership (i.e., belonging). Belonging and the sense of ownership of place are relevant to communities' future orientation as well and according to our considerations, related also to the sustainability of urban communities and cultural policies of the cities. In this sense, the negotiation and communication between community actors and public officials of the cities deserves a lot of attention while the implementation of urban cultural policy is on focus.

From urban cultural policy perspective, the low-threshold participation and opportunities for grassroots cultural activity seem an underexploited resource in the cities, especially when the concept of sustainability is under consideration. Regarding to our case, the multifaceted role of culture is recognised at the strategic level in the city of Jyväskylä and the city wishes to cultivate this, yet, according to our findings it is not visible in practise in our case context. Many questions arise. At policy level we need to determine how to create the ‘community spirit' and support grassroot activities. It would also be important to reflect on how to conduct cultural policy from the prerequisites perspective. Additional key questions concern participation and inclusion: how to involve new residents in activities, i.e., how to involve passive residents and motivate those who are already active? From the cultural sustainability and community resilience point of view, further research should analyse the steering of the transformation of sustainability in the values, lifestyles and attitudes of individuals in different community contexts. It would also be important to find new ways of exploring these questions and to develop the indicators and units of analysis to measure the direct and indirect impacts of policies. However, we argue that holistic analysis of residents, actors and institutions viewpoints helps us to understand the practises and processes related to community resilience. All this deserves multidisciplinary research and joint reflection. From the basis of our experience, we recommend applying a multimethod approach and data triangulation that helped us to make sense of how urban cultural policy and cultural participation can support community resilience at community level.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Jyväskylä. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The research project of the article have funded by the Lähiö fund (Ministry of Environment) and “A “room” of their own - training cultural workers for facilitating rural youth culture (R YOUCULT)” project. KA220-ADU-2021-015; 2021-DK01-KA220-ADU-000033681.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ala-Mantila, S., Hirvilammi, T., Jokela, S., Laine, M., and Weckroth, M. (2022). Kaupunkien rooli kestävyysmurroksessa: planetaarisen kaupungistumisen ja kaupunkien aineenvaihdunnan näkökulmat (The role of cities in sustainability transformation: Perspectives of planetary urbanisation and urban metabolism). Terra. 134, 225–239. doi: 10.30677/terra.116456

Alessandria, F. (2016). Inclusive city, strategies, experiences and guidelines. Procedia - Social Behavioral Sci. 223, 6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.274

Bell, D., and Orozco, L. (2021). Neighbourhood arts spaces in place: cultural infrastructure and participation on the outskirts of the creative city. Int. J. Cultural Policy. 27, 87–10. doi: 10.1080/10286632.2019.1709059

Bernelius, V., and Vaattovaara, M. (2016). Choice and segregation in the ‘most egalitarian' schools: cumulative decline in urban schools and suburbs of Helsinki, Finland. Urban Stud. 53, 3155–3171. doi: 10.1177/0042098015621441

Brand, F. S., and Jax, K. (2007). Focusing the meaning(s) of resilience: resilience as a descriptive concept and a boundary object. Ecol. Soc. 12, 23. doi: 10.5751/ES-02029-120123

Callaghan, E. G., and Colton, J. (2008). Building sustainable and resilient communities: A balancing of community capital. Environ. Dev. 10, 931–942. doi: 10.1007/s10668-007-9093-4

City of Jyväskylä (2021a). Jyväskylä City Strategy 2017-2021. Available online at: https://www.jyvaskyla.fi/en/jyvaskyla-information/jyvaskyla-city-strategy (accessed 4 August, 2021).

City of Jyväskylä (2021b). Kulttuurisuunnitelma [Cultural Plan]. Available online at: https://beta.jyvaskyla.fi/sites/default/files/atoms/files/jyvaskylan_kulttuurisuunnitelma_29112017.pdf (accessed 10 September, 2021).

City of Jyväskylä (2021c). Jyväskylän kaupungin osallisuusohjelma [Inclusion program of the city of Jyväskylä]. Available online at: https://www.jyvaskyla.fi/sites/default/files/atoms/files/78306_jyvaskylan_osallisuusohjelma_hyvaksytty_20150928.pdf (accessed 10 September, 2021).

City of Jyväskylä (2021d). Jyväskylän kaupungin yhdenvertaisuussuunnitelma [Equality Plan of the city of Jyväskylä]. Available online at: https://www.jyvaskyla.fi/sites/default/files/atoms/files/89085_jyvaskyla_ yhdenvertaisuussuunnitelma_2017.pdf (accessed 10 September 2021).

City of Jyväskylä (2022). Ajankohtaista tietoa Jyväskylästä [Statistics of Jyväskylä]. https://www.jyvaskyla.fi/jyvaskyla/tilastot/aluekohtaista-tietoa-jyvaskylasta (accessed 4 April 2022).

Crossick, G., and Kaszynska, P. (2016). “Understanding the Value of Arts and Culture,” in The AHRC Cultural Value Project. Arts and Humanities Research Council. Available online at: https://ahrc.ukri.org/research/fundedthemesandpro%20grammes/culturalvalueproject/ (accessed 11 April 2022).

Dahlstedt, M., and Ekholm, D. (2018). “Social exclusion and multiethnic suburbs in Sweden,” in The Routledge Companion to the Suburbs, Hanlon, B., and Vicino, T. J. (London: Routledge), 1–10. doi: 10.4324/9781315266442-14

Darlow, A. (1996). Cultural policy and urban sustainability: making a missing link? Planning Pract. Res. 11, 291–302. doi: 10.1080/02697459616861

Daykin, N., Mansfield, L., Meads, C., Gray, K., Golding, A., Tomlinson, A., et al. (2020). The role of social capital in participatory arts for wellbeing: findings from a qualitative systematic review. Arts Health. 13, 134–157. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2020.1802605

de Graaf, L, van Hulst, M., and Michels, A. (2015). Enhancing Participation in Disadvantaged Urban Neighbourhoods. Local Govern. Stud. 41, 44–62. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2014.908771

Dessein, J., Soini, K., Fairclough, G., and Horlings, L. (2015). “Culture in, for and as Sustainable Development,” in Conclusions from the COST Action IS1007 Investigating Cultural Sustainability. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, Finland.

Duxbury, N., Cullen, C., and Pascual, J. (2012). “Cities, culture and sustainable development,” in Cultural Policy and Governance in a New Metropolitan Age, Anheier, H. K., Isar, Y. R., and Hoelscher, M. London: Sage, 73–86. doi: 10.4135/9781446254523.n6

Duxbury, N., Hosagrahar, J., and Pascual, J. (2016). Why must culture be at the heart of sustainable urban development? United Cities and Local Governments. Available online at: https://www.agenda21culture.net/sites/default/files/culture_sd_cities_web_spread.pdf (accessed June 30, 2023).

Duxbury, N., and Jeannotte, M. S. (2010). “Culture, sustainability, and communities: exploring the myth,” in Oficina do CES n.° 353. Coimbra: Centro de Estudos Sociais.

Duxbury, N., Kangas, A., and De Beukelaer, C. (2017) Cultural policies for sustainable development: four strategic paths. Int. J. Cultural Policy 23, 214–230. doi: 10.1080/10286632.2017.1280789

Ebrey, J. (2016). The mundane and insignificant, the ordinary and the extraordinary: understanding everyday participation and theories of everyday life. Cultural Trends. 25, 158–168. doi: 10.1080/09548963.2016.1204044

European Parliament (2020). Social Sustainability. Concepts and Benchmarks. Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies Directorate-General for Internal Policies. Available online at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/648782/IPOL_STU(2020)648782_EN.pdf (accessed 27 April, 2023).

Freshwater, D. (2015). Vulnerability and resilience: two dimensions of rurality. Sociologia Ruralis. 55, 497–515. doi: 10.1111/soru.12090

Grodach, C. (2009). Art spaces, public space, and the link to community development. Community Dev. J. 45, 474–493. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsp018

Grodach, C. (2017). Urban cultural policy and creative city making. Cities. 68, 82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2017.05.015

Grodach, C., and A., Loukaitou-Sideris (2007). Cultural development strategies and urban revitalization: a survey of U.S. Cities. Int. J. Cultural Policy. 13, 349–370. doi: 10.1080/10286630701683235

Hammersley, M. (2008). “Troubles with triangulation,” in Advances in Mixed-Methods Research, Bergman, M. (ed). London: Sage, 22–36. doi: 10.4135/9780857024329.d4

Hannerz, U. (1992). Cultural Complexity: Studies in the Social Organization of Meaning. New York: Columbia Unversity Press.

Heikkilä, R. (2021). The slippery slope of cultural non-participation: Orientations of participation among the potentially passive. Eur. J. Cultural Stud. 24, 202–219. doi: 10.1177/1367549420902802

Heikkilä, R., and Lindblom, T. (2022). Overlaps and accumulations: the anatomy of cultural non-participation in Finland, 2007 to 2018. J. Consumer Culture. 23, 122–145. doi: 10.1177/14695405211062052