- 1Department of Practical Theology, Unit for Sociology for Religion and Church, Leipzig University, Leipzig, Germany

- 2Faculty of Theology, Leipzig University, Leipzig, Lower Saxony, Germany

- 3Institute of Political Science, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany

Legitimacy is a central resource for all political systems. This include democracies as autocracies. For democracies, you need the acceptance of the normative concept of democracy by the citizens. Simply put, this norm requires an empirical legitimacy. The empirical legitimacy focus on different understandings of democracy. Mostly the aspect of individual freedom is dominant. Empirical analyses show this idea do not only work for Europe. The article first shows what empirical legitimacy means conceptually and then analyzes this existence of legitimacy in a comparative perspective. It is the erosion of legitimacy that can lead a political regime to collapse. Current survey data from political culture research show not only differences in the legitimacy of democratic and autocratic regimes, but also an increase in the importance of different understandings of democracy. Some of these are no longer democratic.

1 Legitimacy as a necessary basis for democracy

As early as 1975, a crisis of legitimacy of democracy was stated for the first time (Watanuki et al., 1975). Today, too, this concern is resurfacing. Thus, democratic systems have been subject to drastic change in recent decades. Increasing successes of right-wing populist parties, demonstrations and disputes regarding positioning on Russia show a disjointedness that politicians perceive as threats. It is not without reason that social cohesion is invoked in response to these observations—even if one does not know exactly what this actually is in concrete terms. Often, examples cited as evidence of a legitimacy crisis in democracy point less to a withdrawal of legitimacy for democracy as a system of rule than to an unstable dissatisfaction with the current political system and a disenchantment with politicians and parties (Crouch, 2005). It is possible that the alleged crises of legitimacy are, after all, rather temporary crises of the performance and efficiency of the current political systems and the personnel governing them. At this point, political culture research, which not only attempts to empirically fathom the effects of political crises on the attitudes of the population, but also focuses on the relevance of the population's attitudes with regard to the stability of political systems (Almond and Verba, 1963; Easton, 1975; Lipset, 1981; Fuchs, 1989), is helpful. The core element is the legitimacy of democracy. Legitimacy the longer-term stability of a system of rule based on recognition by its citizens. Legitimacy is a resource that keeps political systems alive in the longer term and opens up a space for action in which political decisions can be made beyond individual discourses. Even if democracies are particularly dependent on the recognition of their citizens due to their (normative) claim, every form of rule can gain legitimacy—and wants to do so, for example, in order to avoid expensive repressive measures. At the same time, citizens also want to see their wishes and values realized (Inglehart, 1971, 1990).

In this paper, the question is why empirical legitimacy is at the core of democracy research and how the empirical legitimacy of political systems (and democracies in particular) has developed in recent decades. Legitimacy as a more fundamental form of recognition of rule must be distinguished from trust based on experience. This question is answered by a broad theoretical debate which we are try to prove in parts using comparative data from survey research (also Wiesner and Harfst, 2020). Due to capacity constraints, and because debates on the legitimacy crisis (Pharr and Putnam, 2000) focus primarily on the Western world, the analyses are limited to Europe. Our hypothesis is: In European democracies, we find little evidence of a legitimacy crisis of democracy as an ideal and form of rule, but we do find signs of a crisis of the political implementation of the same. Crucial for the latter are discrepancies between citizens' aspirations and current implementations of democracy.

Thus, the focus of the paper is on the capture of empirical legitimacy. It is understood in a strict sense as social recognition of the system of rule and its political components (objects). However, by referring to democracy, a normative evaluation framework, albeit still broad, is applied. This is a theoretical approach or a discussion of theory on the basis of empirical facts. The empirical results presented serve to examine the extent to which the thesis correlates with reality and how anchored the empirical legitimacy is. The latter is seen as a cautious confirmation, but its main purpose is illustrative. Accordingly, complex empirical analyses are not carried out here.

2 Theory: political culture, legitimacy, and democracy

2.1 Legitimacy—what is it?

Before one compares something, it must be clear what one is examining. If one follows Max Weber, legitimacy always has to do with the order of rule. According to Weber (2005, p. 38), domination is “the chance for an order of certain content to find obedience among admissible persons”. The conducive persons are usually members of a definable political community. This defines the group of those affected in the same way that it is the citizens and their attitudes toward the system of rule that are at the forefront of the attribution of legitimacy. For the docility of those subjected to rule, according to Weber, there is a need for the belief in legitimacy on the part of those subjected to rule. “Every (rule) seeks rather to awaken and cultivate the belief in its legitimacy” (Weber, 2005, p. 157). Simply put, the subjects of rule should recognize the rule, the political order, and the political system, otherwise their existence could be endangered. Legitimate then is the order that is recognized on the part of the citizens. Legitimacy must be distinguished from legitimation. Legitimation strategies are used by individuals and rulers to gain legitimacy. Legitimation is the result of a purposeful process by ruling actors to secure themselves—i.e., a strategy (also Beetham, 2013, p. 11; Zürn, 2011, p. 606). Legitimacy, on the other hand, describes the state of affairs in the political community.

Why is legitimacy important for a political order in the first place? For one thing, it ensures a certain longevity in the exercise of power. One is less dependent on cyclical political fluctuations of opinion in the population. Second, legitimacy reduces investment in other measures to maintain rule, such as repression. In particular, the (advance) trust in the rulers resulting from legitimacy that they will work for the good of the community (and thus for the good of themselves) reduces the use of resources (on the executive side of the political rulers). Legitimacy thus stabilizes the system of rule. To achieve this, various legitimacy strategies can be used. However, their success is not guaranteed, but always depends on the recognition of the strategy used by the citizens. Weber cites charisma, rationality and tradition (custom) as the basis of a legitimacy validity (Weber, 2005, p. 159). Schmidt (2013, p. 555–556) follows this in his definition of legitimacy in the Dictionary of Politics and distinguishes between: (1) the legitimacy of a system of rule in the sense of the commitment of state and individual action to law and constitution (legality), (2) the legitimacy of a system of rule in the sense of its worthiness of recognition based on generally binding principles (normative legitimacy), and (3) the recognition of a system of rule as lawful and binding on the part of those subject to the rule (empirical legitimacy). If the stability of a political regime is taken as the central epistemological interest, empirical legitimacy dominates in all three sources. Thus, the acceptance of the resources charisma, tradition and legality as the basis of legitimacy depends on the prior recognition of these sources of legitimacy by citizens. A legal order is worthy of recognition only if the principles on which it is based have already been recognized as legitimate by a decisive part of the population. Whichever way one turns it, legitimacy is always to be understood as something socially recognized, not only for the purposes of investigation, but also from a fundamental understanding of legitimacy. The principled recognizability of the form of rule helps in this recognition, but does not fully secure it, nor does it replace empirical recognition. Recognizability does provide legitimacy, but only in a normative way (Braun and Schmitt, 2009, p. 53; Nohlen, 2002).

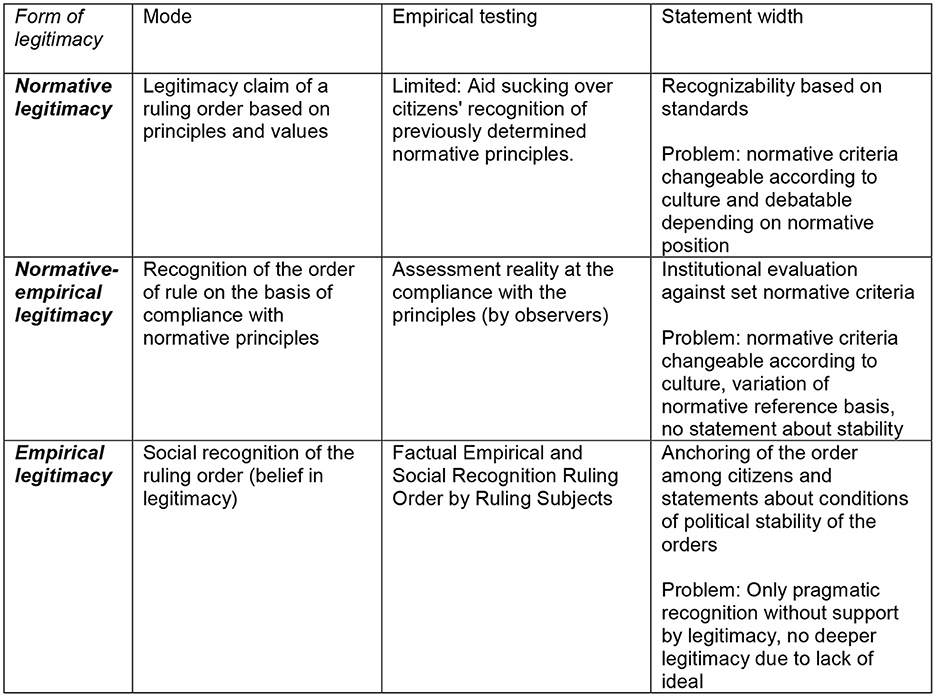

Accordingly, in research terms, it is important to distinguish empirical legitimacy from normative legitimacy (Rosanvallon, 2010; Thornhill and Asheden, 2010; Patberg, 2012, p. 158–160). Normative legitimacy views a political order as legitimate if it meets a normative legitimacy claim. On the one hand, the normative legitimacy claim must be grounded at the value level; on the other hand, it must find its implementation in reality. The assessment of whether value expectations correspond to reality is, of course, again subjective, since normative specifications also depend to a large extent on the individuals who establish them (also Beetham, 2013, p. 14; Ferrin and Kriesi, 2016, p. 10).1 One can call this part of the normative approach normative-empirical legitimacy for better distinction. For example, it can be determined whether institutionally secured participation rights are granted—or not. This also empirical determination is carried out by scientists oriented to normative criteria. Transferred, this can be seen as oriented to the principle of rule for the people. The problem is that normative recognition and even its empirical implementation do not protect against the withdrawal of legitimacy on the part of the citizens—and thus the collapse of the system (Figure 1).2 Moreover, agreement on the validity of a normative basis of legitimacy is not detached from negotiation among actors.

In order to complicate and simplify the matter at the same time, normative settings must be taken into account for the realization of the approach used so far as an empirical concept of legitimacy in the tradition of Weber. The normative setting of a system of rule, for example as democracy, is an important component for its social recognition. Another is how those subject to rule envision a form of rule and political institutions so that they recognize it. Ideals and desires shape social recognition and empirical legitimacy. In the second case, one is again at the level of determining legitimacy through social recognition. For example, recognition of democratic regulatory procedures is legitimate only if one acknowledges the underlying assumption of the normative superiority of bureaucratic, procedural democracy. If these are subsequently respected, then the regime can be considered legitimate. In the most demanding case, there are three aspects that must be complied with for a system of rule to be legitimate: (1) The normative recognizability of a particular form of rule. (2) The implementation of the normatively recognized form of rule in reality, for example through the creation of appropriate institutions. (3) The empirical recognition of the existing order of rule by its subjects. Normative specifications are suitable for empirical purposes only if they are made explicit early on: E.g., by explicating whether one is studying the legitimacy of democratic regimes or other systems of rule. Thus, political regimes can be legitimate according to their normative standards without conforming to the normative standards of others. Similarly, political regimes can be legitimate according to normative standards without being so in the eyes of citizens.

However, the continued existence of the system of rule is decided solely by its empirical legitimacy. If you like, you are now moving on the level of “rule by the people”. This makes it clear why current empirical legitimacy research focuses on the factual social recognition of ruling orders and systems—only this gives one information about the stability of the ruling order with a certain concreteness. Not only the ruling order as a whole, but also its fixed components can receive legitimacy—and need it. The recognition of a federal constitutional court presupposes its legitimacy just as much as a parliamentary system. And both political objects can be legitimate or illegitimate independently of each other. Determining empirical legitimacy also requires reference points. If we examine the legitimacy of democracies, then their legitimacy is measured by the image of democratic institutions. It is therefore relevant to know what kind of (normative) image of democracy one has. This has implications for the legitimacy and stability of the political regime. From a practical point of view, this understanding often remains relatively irrelevant for political culture research, with its goal of making statements about the stability of political rule: For regardless of what citizens imagine a particular political object or system of rule to be, it requires social recognition for its preservation. This may be based on false premises, and citizens may support a normatively illegitimate political regime: If it achieves legitimacy and support at the empirical level, this remains secondary for stability reasons. This line of reasoning is deep into political culture research, which is devoted to determining the framework for political stability by taking citizens and their attitudes into account.

2.2 Legitimacy in political culture research

Empirical legitimacy is the central element in political culture research. Lipset (1981) even assigns it the central role for the stability of a political system, whatever its orientation. “Legitimacy involves the capacity of the system to engender and maintain the belief that the existing political institutions are the most appropriate ones for the society” (Lipset, 1981, p. 64). Legitimacy thus represents an important safeguard against the collapse of a political system in times of crisis (summarized by Pickel and Pickel, 2006, p. 86–88). Lipset thereby relates it to the effectiveness, or rather the perception of the effectiveness of the political system by its citizens. This results in a kind of process model that establishes the link between legitimacy and stability (Fuchs, 2004). The relationship established between economic effectiveness and legitimacy would later also play an important role in Ronald Inglehart's explanation of differences between countries or cultures. He saw economic development as centrally linked to cultural development and saw modernization as a link (Inglehart, 1988, p. 1206). Somewhat more parsimoniously, another central propagandist of political culture research, Easton (1975, 1979) uses the term legitimacy. He distinguishes it from trust and applies it more precisely to political objects. For Easton, too, legitimacy is a manifestation of political culture that attracts permanence. In addition to the distinction thus introduced between trust and legitimacy, the political objects of reference are also differentiated. This allows for a broader evaluation of empirical legitimacy such as a more differentiated judgment regarding the consequences of population attitudes for the stability of a system of rule. All objects can, according to Easton incidentally, be positively or negatively supported. However, a predominantly positive political support is necessary to maintain the persistence of a political system. In Easton's system-theoretical input-output model, the political regime receives this support mostly when the citizens' demands on the system (demands) are met. Diamond (1999) follows these considerations, but with a clear focus on democracies. This focus is not provided for in Easton's original model. This example, however, illustrates the direction in which current research on legitimacy and political culture has moved—toward an evaluation of the legitimacy and political support of democracies. This is undoubtedly related as much to the growth of democracies since 1945 as to interest by the social sciences in the concept of democracy on the normative side. At the same time, as already mentioned, it is not per se only democracies that can draw on legitimacy, as sometimes seems to creep into discussions of legitimacy. Other forms of rule and regime also benefit from legitimacy (Pickel and Stark, 2010; Norris, 2011) and use legitimacy strategies to a large extent in order to obtain just such legitimacy. The reason for this has also already been mentioned: Legitimacy reduces the cost of repressive measures as much as other necessary investments to stay in power and rule. This figure of justification goes back to Weber (2005, p. 157).

The above models are linked to considerations that make the concept of political support more precise in its referential power while making visible a normative orientation toward democracy. They take up the shift of interest in legitimacy research toward democracy (Buchanan, 2002). In this context, Fuchs (2002) placed the recognition of the ideal of democracy in the place of the political community—and thus the aspect of a general legitimacy of democracy. In effect, this is a recognition of the normative validity of an idea. He distinguished from this the recognition of the political (democratic) system and its performance assessment. Just as there are interactions between the different levels, one can distinguish the objects of citizens' attitudes toward democracy. Pickel (2020) recently differentiated this model with reference to political attitudes and political objects. Her goal was to take back some of the focus on democracy as a form of reference without giving up the analytical gains from the previous developments at the level of agreement with values and with real forms of rule. To do so, it separated system support from the legitimacy of the political system of rule and integrated the level of political community into its model. Specifically, the newly separated aspect of system support is interesting, which strongly places the implementation of normative foundations in a real political regime at the center of the analysis and distinguishes it from the conviction of the appropriateness of a particular political system for one's society. It is related to the assessment of the political performance of the regime. These aspects, in turn, distinguish it from the trust that a political regime or its representatives can gain.

In the 1980s, the strong institutional ties of political cultural research in the tradition of Almond and Verba were criticized (see Flanagan, 1987; Eckstein, 1988). On the one hand, the survey method of classical political culture research on population attitudes was regarded as narrow and an extension of the surveys to symbols and cultural practices was addressed. These considerations are still valid today, but have not yet been adequately implemented, especially for comparative political science analyses (Wiarda, 2014). The role of legitimacy in these considerations is also unclear. Another criticism relates to the strong focus of classical political cultural research on political institutions and attitudes toward political institutions, as found, for example, in Easton (1975). This criticism sees cultural convictions—again understood as citizens' attitudes—and cultural change as decisive for the design of institutions (Inglehart, 1990). The cultural changes are caused by socialization and breaks in socialization as well as socio-economic changes in the context of modernization (Linz, 1988; Inglehart and Welzel, 2005). This change can also influence the relationship to political institutions, as shown, for example, by demands for an ecological lifestyle. Here, the legitimacy of the institutional system is derived almost more strongly from demands to adapt to the wishes and values of citizens than in the classic approaches of political culture research (Welzel, 2013). This is expressed in potential shifts in the understanding of democracy. At the same time, the legitimacy of democracy, or the congruence between (political) institutions and citizens' values and beliefs, remains central to the legitimacy of democracy and democratic political institutions.

2.3 Legitimacy, legitimacy crisis—and their investigation?

The preceding unfolding has shown that legitimacy can only be empirically investigated in two concrete ways: First, in the implementation of a previously defined normative model in institutional reality, and second, with regard to social recognition or legitimacy belief among the population. In the first case, one compares the existing order with the normative ideal and assesses this from the perspective of the researcher (Patberg, 2012, p. 159). If one directs one's gaze to the institutional level or the stability or instability of the political regime, it becomes clear why the bulk of empirical legitimacy research in recent decades has placed its focus primarily on the empirical analysis of survey data and statements about legitimacy belief (Torcal and Montero, 2006; Diamond, 2008; Ferrin and Kriesi, 2016; Weßels, 2016). Today, when we speak of empirical legitimacy, we are primarily referring to this form of legitimacy determination. What is interesting here is that the differentiation in political culture research brings two objects of legitimacy into view—that of democracy as a normative ideal and that of the current political regime (i.e., the current manifestation of democracy). In general, the orientation of the debate on legitimacy crises and post-democracy has again increasingly directed the gaze of empirical legitimacy research in the direction of democracies and thus connected it to democracy research. Early thoughts in this direction of a legitimacy crisis (Watanuki et al., 1975; Pharr and Putnam, 2000; Kriesi, 2013) already describe the uncertainty regarding the acceptance and anchoring of democratic political systems in their population. Preconceptions from more elite-theoretical approaches still play a role. Subsequently, research interest focused increasingly on the so-called Western world and the OECD countries. They also had the advantage, which should not be underestimated, of having reasonably reliable survey data, unlike most other areas of the world. These are now absolutely necessary for research on empirical legitimacy in the sense of legitimacy beliefs. However, they also have a not insignificant shortcoming: It is not certain to what extent survey data for less democratic regimes are reliable in their informative value—and not a consequence of social desirability. Thus, the debate presumably remains undecided as to the extent to which the positive attitude toward democracy as the best form of government in China and a high level of satisfaction with democracy are the consequence of real sentiments, a different understanding of democracy or simply social desirability.3

In combination, this has led to a situation in which legitimacy research to date has focused on democracies and the Western world, even though in recent decades some findings have been presented on autocracies (Rose and Shin, 2001; Lane and Errson, 2003; Gerschewski, 2010; Pickel, 2010; Gerschewski et al., 2013; Kailitz and Köllner, 2013) or democracies beyond the West (Schubert, 2012; Schubert and Weiß, 2016). The insight from these analyses is that non-democracies can and do achieve legitimacy. Another, however, that for a long time democracies were much more successful in gaining legitimacy. One reason is the traction of the normative model of democracy for citizens (Inglehart and Welzel, 2005; Welzel, 2013), but also its role model effect promising (economic and social) progress. This “success story of democracy” is expressed in the fact that quite a few legitimation strategies emphasize the reference to their own democratic orientation, however little these regimes often implement democratic principles in reality. As a consequence, legitimacy research has experienced a noticeable boost in recent decades. On the other hand, increasing protests and a spread of success of populist arguments in the Western world show that the aspect of a legitimacy crisis of democracy has to be treated more carefully than before. Is it really the case that democracy is being deprived of support and legitimacy, or is it a matter of fluctuations in performance that then have only limited relevance for the stability of democratic systems? Various reasons can be blamed for these developments: Fluctuations in performance due to declining economic or political effectiveness (Gasiorowski, 2000; Teorell, 2010; in part Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012), an erosion of the model of a liberal democracy-or a growing distance between desire and reality due to an increasing rise in demands on democracy (Norris, 1999; Pharr and Putnam, 2000; Welzel, 2013).4 Especially following the last point, it becomes clear that an empirical examination of legitimacy requires models that include the citizens' understanding of democracy in their thinking, as they have to take into account the difference between desire and reality or the difference between objective reality and subjective perception. The question is: Is it true that it is precisely the citizen-centered democracies that are increasingly suffering from a withdrawal of legitimacy by them? A follow-up question is: How does this happen?

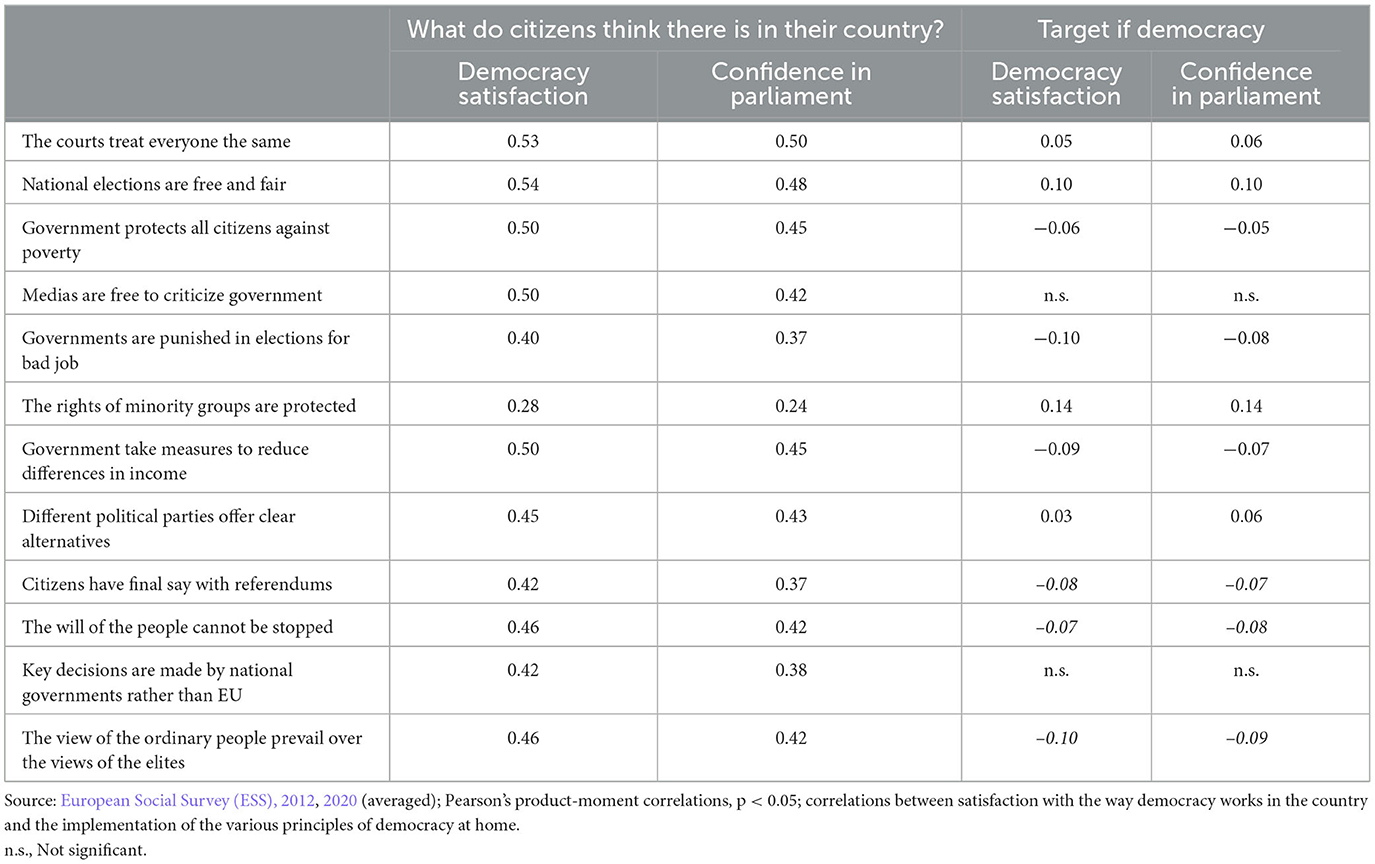

3 Methodology and use of empirical data to illustrate the theoretical arguments

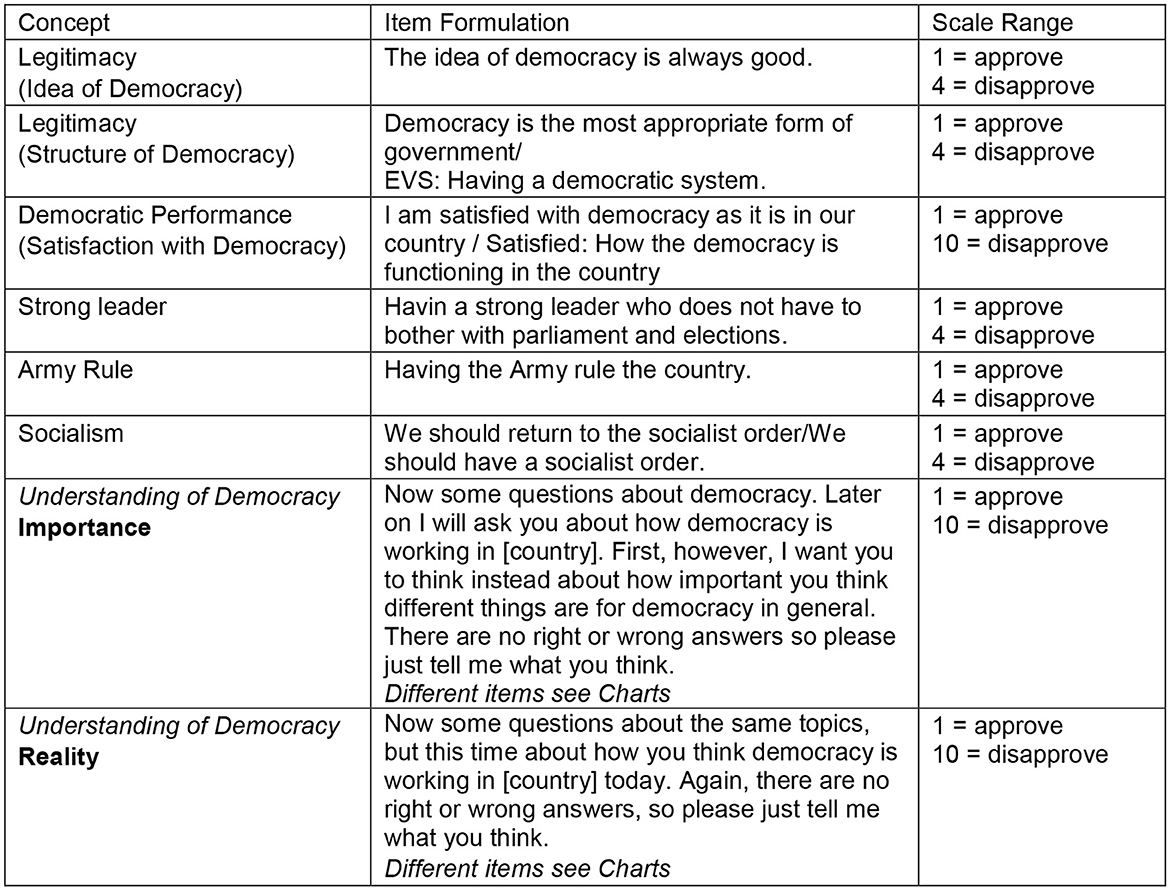

If one argues with empirical legitimacy, one cannot avoid at least taking a look at the empirical situation—even if the essay has a more theoretical focus. In the following, this will be done using data from the European Values Study (EVS) with additions from the World Values Surveys (WVS). Both data sets use comparable, if not the same, indicators in the concepts that are important for the article (Figure 2). As the understanding of democracy is not or not extensively surveyed in the European Values Study and the World Values Surveys, we have to draw on data from the European Social Surveys to illustrate this. Both data sets do not include the same countries (see Figure 2). The European Social Survey (ESS), 2012 (ESS Round 6) and 2020 (ESS Round 10) alone surveyed the potential content of an understanding of democracy. However, the European Social Survey 6 and the European Social Survey 10 also show considerable country differences. Since it can be assumed that changes in the understanding of democracy tend to be long-term and because a general assessment of the understanding of democracy is particularly important for the article, we present the results for both data sets and cumulate them for correlation analyses. This is necessary because Eastern European countries are very poorly represented in the European Social Survey 2020 and a reliable statement about Eastern Europe can only be made by including the data from 2012. We are aware of the imbalance of the cumulation as well as the lack of direct comparability with the frequency data presented. However, the results nevertheless show a pattern that appears plausible for most European countries.

Figure 2. Availability of data. Source: World Values Surveys (WVS) (2000, 2008), European Value Study (EVS) (2000, 2017), European Social Survey (ESS) (2012, 2020). All data sets include at least 1,000 randomly drawn respondents per country and all studies used are representative surveys.

Since the aim is not to make an exact comparison and, moreover, the aim is to make general statements when using cumulative data, this seems acceptable to us, taking into account the resulting inaccuracies. The aim is to illustrate central understandings of democracy. Although it is possible that the level of agreement is lower or higher in countries not included, it is more likely that the structure of understanding found is comparable. Reducing the countries to a strictly comparable basis would, in our view, result in too great a loss of information. We therefore assume that the frequencies are well reflected by the European Value Study and the World Value Surveys and that the analyses of the European Social Survey's understanding of democracy give an impression of the understanding of democracy that is then only roughly applied to the countries examined. The Political Culture in Central and Eastern Europe (PCE) survey from 2000 (Pollack et al., 2012; also Pickel and Müller, 2009) was used to supplement at least some of the data that asked specifically about the idea of democracy or socialist rule. The brief comparison shows the similarity of the results on the structure of democracy in the World Values Surveys and the European Values Study compared with a specific survey on the idea of democracy in the PCE study. No cases were specifically selected because this would have massively reduced the database. The data from the European Social Survey is cumulated accordingly. Missing values are excluded from the analyses. In none of the variables used did the missing values exceed 10% of the total. All data sets include at least 1,000 randomly drawn respondents per country and all studies used are representative surveys. In this case, it is therefore a structural statement to support the theoretical explanations.

For a systematic comparative analysis, we would have used stricter conditions. Data from World Bank were used for a comprehensive aggregate analysis. In Figure 3 we show the used items for the concepts. In the presentation, we have focused on the dependent variables, or the most important levels of the legitimacy of democracy and its reference factors.

4 Indicators of empirical legitimacy in international comparison

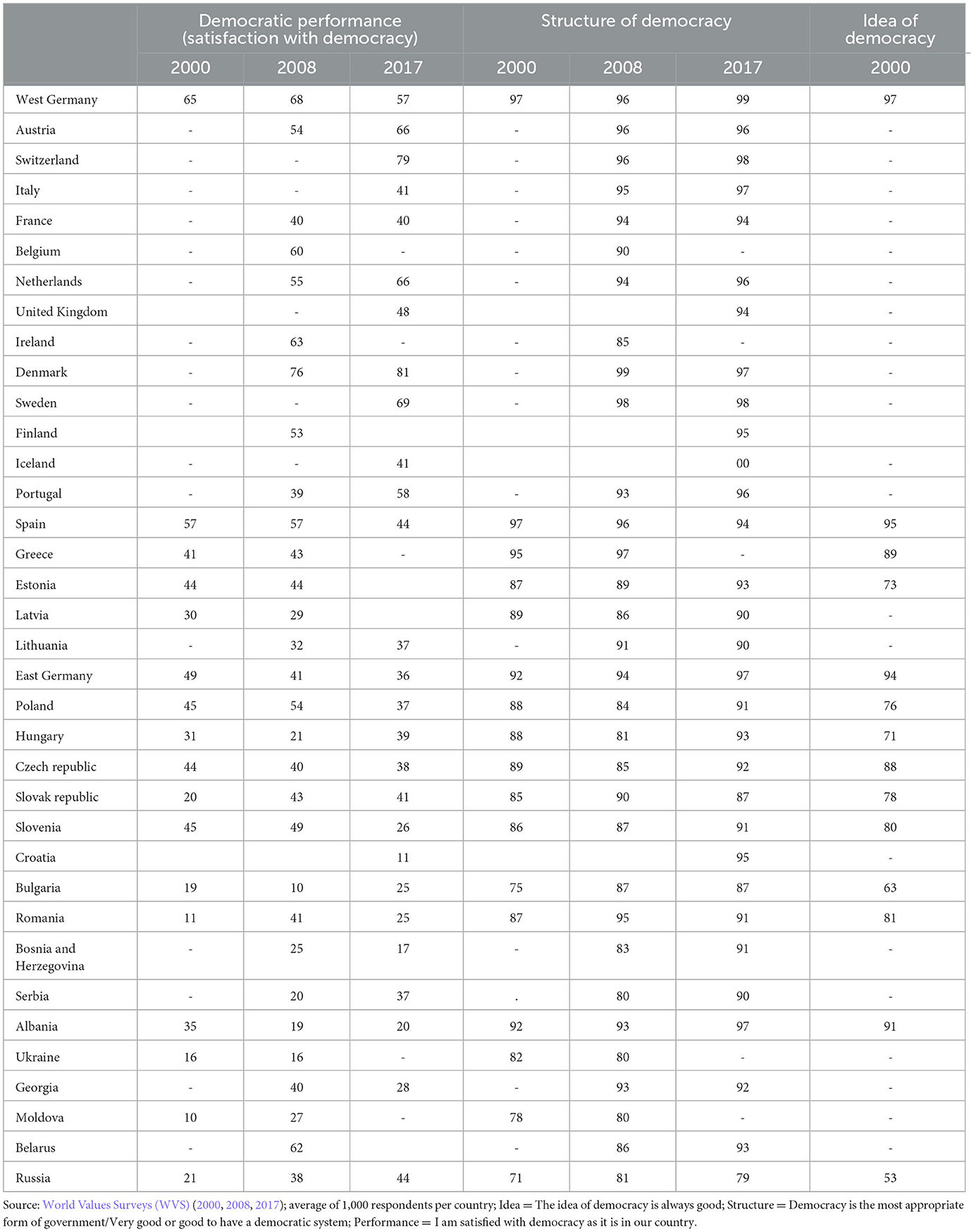

In empirical legitimacy research, the social recognition of systems of rule is of primary interest. Given the differentiation of both legitimacy and objects of political support presented above, however, even such a simple-sounding descriptive view requires some differentiation. Even if one focuses the empirical investigation on democracies, it is imperative to distinguish between the legitimacy of the form of rule (and the ideal) democracy in general and the legitimacy of its current political-institutional manifestation (Westle, 1989). Both presuppose that one can empirically grasp the legitimacy of democracy at all. In political culture research, this is usually done by means of questions that take up the general, and thus according to Easton (1979) diffuse, support for democracy. Commonly, it is explored to what extent citizens consider it good to live in a democracy, or whether they assess it as the appropriate form of rule. However, questions specifically about the idea of democracy are (not only) scarce in comparative survey research. At least one such question was asked in 2000 in a group of (mostly Eastern) European countries (Pollack et al., 2003). The degree of approval for the idea of democracy is high in almost all of the countries studied, and higher in the three Western European countries than in the Eastern European countries. Approval is lowest in Russia. The data also reveal something else: The response to questions about democracy as the most appropriate form of government, or the classification in the World Values Survey or European Values Survey that it is good to live in a democracy (structure of democracy), hardly differs from the response to the idea of democracy (internal correlation of the individual data among 13 European countries r = 0.69). At this point, we are apparently only dealing with variations of one and the same object assessment by different questions—the legitimacy of democracy as a form of rule.5

If we look at the response behavior across a larger number of countries (Table 1), the dominance of people's affection for democracy as a form of government is unmistakable in a European comparison. This approval is extremely high and indicates a high basic acceptance of democracy among its citizens. One could also say that the legitimacy of the normative (or functional-institutional) concept of democracy is high worldwide. Democracy is preferred by citizens over other forms of rule. But some findings force reflection. For example, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the stability of political orders in non-democracies (e.g., Russia or Belarus) based on the broad support for democracy as a form of government (Klingemann and Fuchs, 1995; Pickel, 2013). At the performance level, not only are clear differences apparent between the legitimacy of democracy as an ideal and form of rule and the assessment of current democratic systems, but higher fluctuations also prevail. This is perhaps to be expected in view of the dependence on the current economic and political situation.

Even here, however, the Western European welfare states fare better on average. The results confirm the traction of “catch-term” democracy. Not only do almost all of the world's states, however little democratic they may be from a Western perspective, want to claim the label democracy for themselves as a legitimation strategy, but in a rough sense this also coincides with the citizens' goals. In view of the high level of global legitimacy, however, it is natural to assume differences in citizens' understanding of democracy—or at least different ideas about what is currently most important in the existing democracy (Pickel et al., 2006). Especially if one takes into account the existing diversity in the forms of rule that exist. However, a diffuse notion of democracy, with positive connotations and desires, seems to unite citizens in different cultures. One can assume that the identification with popular rule, but also with individual freedom, is significant (Welzel, 2003, 2013).

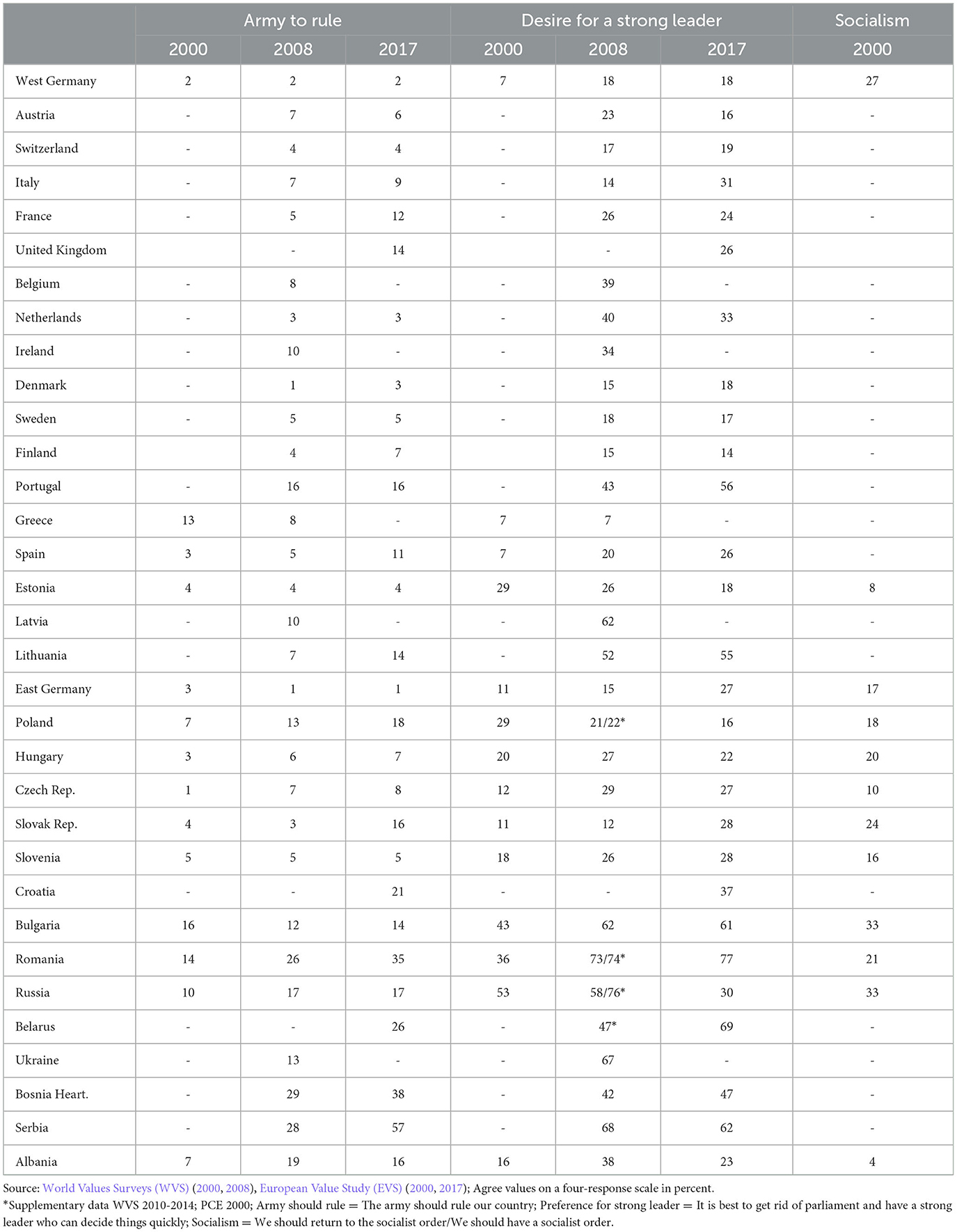

Statements regarding the rejection of so-called antidemocratic system alternatives point in the direction of a broad understanding of what is compatible with democracy. In some hybrid regimes or autocracies, for example, there seems to be no problem in combining elements of political life that are incompatible with democracy in the Western understanding with their image of democracy. Although there are also occasional tendencies in Western democracies to show a certain understanding for a strong leader who no longer has to pay attention to parliament, the approval ratings are significantly lower than in other regions of the world (Table 2). Now, a strong leader can still be reconciled with democracy in some respects, but the reference to “without having to pay attention to parliament”, which is usually included in the answer, gives pause for thought. If clear majorities of the population in Russia, Romania and Bulgaria want a “strong leader” in 2008, this may indicate a lack of effectiveness on the part of the regime, but it may also express the desire for a strong central power. In that case, the establishment of a “guided democracy” and the targeted use of this language only correspond to the wishes of a majority of the population-and corresponding institutionalizations would be legitimate in the sense of social recognition. The assessment of a military regime is based on different experiences.

While in Europe (incidentally, despite or because of a relatively high level of trust in the armed forces) this form of rule is largely illegitimate, with the exception of Turkey, this does not apply to all areas of the world. In both Indonesia and Jordan, this form of rule meets with empirical legitimacy. Hybrid regimes or autocracies are thus not generally excluded from acquiring legitimacy (Hadenius and Teorell, 2007; Teorell, 2010; Pickel, 2013). But does this say anything about the stability of regimes and their legitimacy? If we go back to the classification in Figure 1, it would seem that democracy really does have a high level of legitimacy in itself. However, this refers to a normative understanding of democracy that is still extremely broad and can be filled with content, allowing for many nuances and possibilities in reality. Moreover, it cannot be directly inferred that there is support for what one finds to be democracy in one's own country. Looking at the system alternatives, many citizens could indeed lack a strong leader, especially for democracies, and this could lead to a withdrawal of political support and empirical legitimacy. Here, the increase in support in East Germany and that in Portugal is particularly noteworthy. Even more dramatic is the enormous increase in the desire for an arm's-length government in Serbia and, to some extent, in Romania. Here the question turns to the stability of existing democracies. The willingness to open up to anti-democratic system alternatives provides information. A remarkable range was found worldwide. In Europe, too, there are quite a few political communities in which significant segments of the population see a strong leader as not incompatible with democracy and could envision one in their country. Democracy is thus legitimate, but certain alternatives may be as well.

Another possibility is that people consider democracy legitimate at the level of normative ideals, but do not support their democratic regime. Indicators of democratic satisfaction or trust in political institutions provide information about this political support or recognition. Now, by their very name (trust), these are conceptually located only to a limited extent at the level of legitimacy. On the other hand, they are highly significant for the preservation of the ruling system, since the effectiveness of the ruling system at the political, economic and social levels, which is so important for citizens, is ultimately judged in light of the fundamental legitimacy of the type of rule. Thus, the answers to the (unfortunately differently formulated and surveyed) questions about satisfaction with democracy in the country go beyond mere assessments of performance. It is precisely this mixed area between legitimacy and effectiveness that thus draws significance for the preservation of a political regime.6 This highlights the difficulty, ultimately unresolved in political culture research, of surveying and linking political stability and legitimacy. A look at these indicators (Table 1) shows the expected lower values in the performance assessment of democracies as well as differences between different countries. The approval ratings are consistently highest in Western Europe, although there are downward deviations there as well. Unfavorable experiences of effectiveness—or ineffectiveness—are probably responsible for the deviations. In Eastern Europe, for example, there is a massive drop in performance ratings.7 These assessments are supported by figures (not shown here) on trust in parliament. Thus, trust and legitimacy, which in Easton's conception analytically form a separate corridor of support, are mixed at this point. The again considerable satisfaction values with the current democracy in Western Europe show that besides evaluations of the current, legitimacy also has an effect on satisfaction. Possibly, these are positive experience effects (via acquired trust).

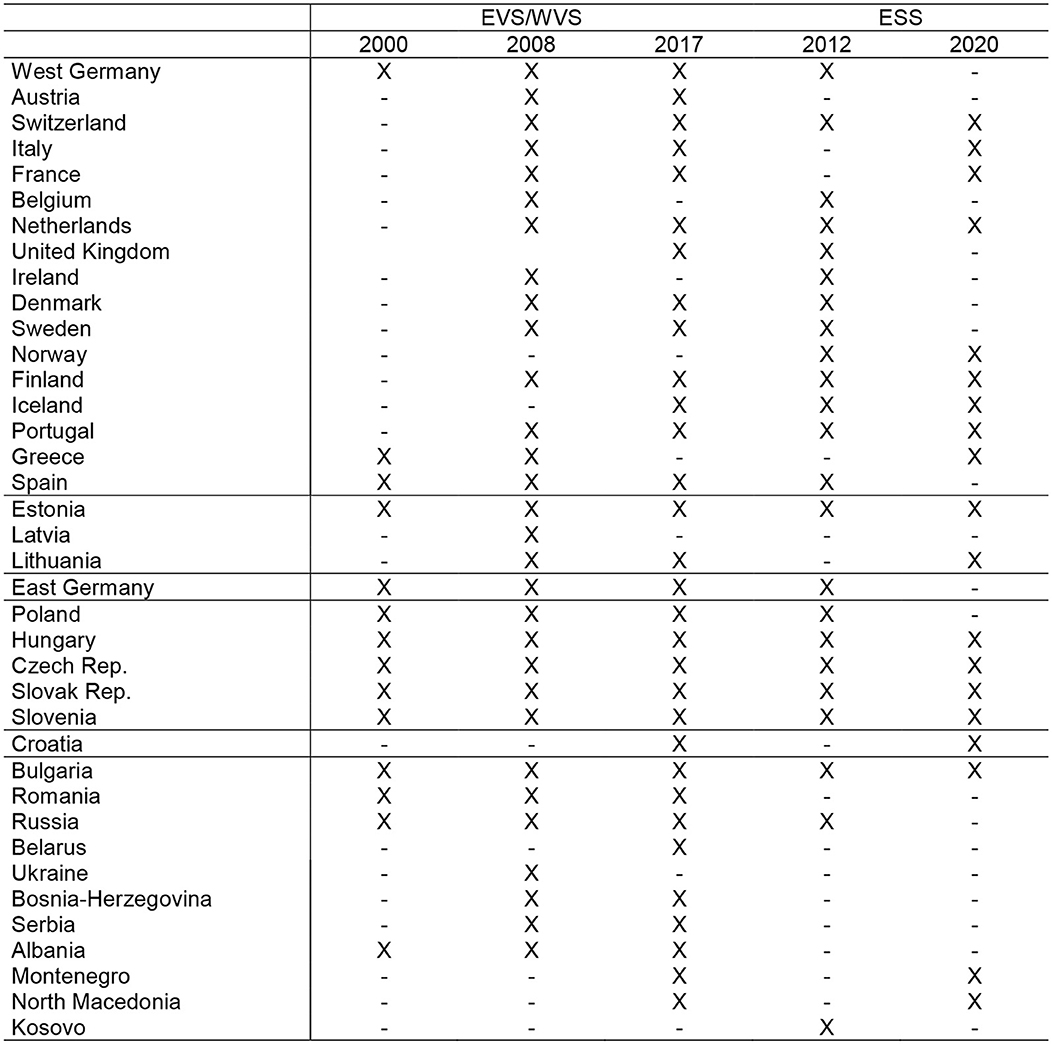

Without question, many factors play a role in these results. They would have to be treated more broadly, which is not empirically possible in an essay limited in scope. Nevertheless, a look at the factors of differentiation across countries makes sense. Of central importance in the explanation, and here one can echo Lipset (1959, p. 68), is the economic effectiveness of the political regime. Correspondences between one's economic situation and satisfaction with the current system are consistently close. In addition to the clear relationship at the aggregate level, a correlation of r = 0.20 is also found at the individual level between the assessment of one's household situation and satisfaction with democracy. This correlation exists equally in democracies, autocracies and hybrid regimes. Perceived economic effectiveness is a mainstay of system preservation for existing regimes, although increases in prosperity can occasionally have a destabilizing effect in the short term in the context of modernization (Teorell, 2010, p. 56–60; Pickel, 2013, p. 192–194; Gasiorowski, 2000). In addition to pure economic effectiveness, empirical analyses include other aspects. These include the deeper anchoring of democracy in the population due to their longer positive experience with it—or habituation. Conversely, as shown by existing socialist legacies in Eastern Europe, historical experience has an impact on legitimacy, and this then also affects the fundamental legitimacy of democracy. Institutional frameworks, including the introduction of elections or rule of law institutions, promote the legitimacy of democracy and the current democratic system (Rothstein, 2009; Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012). To a particular extent, the sense of rule of law and freedom (Welzel, 2013) contributes to differences in measurable legitimacy beliefs across countries. Specifically, the factors of emancipation and guarantee of human rights, as illustrations of individual freedom, function as independent factors. Also of importance is political effectiveness, for which the ability to regulate corruption is recognized as a possible indicator. The influencing factors are briefly summarized in a table (Figure 4).9

Figure 4. Factors influencing the evaluation of democracy in Europe (schematic representation). Source: Compilation based on multiple empirical regression analyses calculated by the authors of the article with data from the World Values Survey (3 waves; 2000, 2008, 2017) and the European Values Study (2 waves; 2000, 2017) by including different macro-variables from World Bank or UN sources; concentration and transfer in the signs by the authors; + + + = high correlation, ++ = medium correlation, + = still significant correlation; correlations in negative direction = –;/= no correlation; () = Limited or inconsistent effect across various indicators. For the multiple calculations behind the results, see Pickel (2015, 2020).8

If we compare the two forms of democracy evaluation—support for the current democratic system and the legitimacy of democracy—two things become clear: First, there is a relatively large overlap in the influence structures. That is, if a background factor has an effect on the assessment of the current democratic system, then it is also often relevant for the general recognition of democracy as the most appropriate form of government. As Lipset (1959) pointed out, there is a link between the performance and legitimacy of democracy. Differences in the conditional structures point to the respective independence of the two dimensions. In particular, the influences of economic welfare, social inequality or institutional conditions vary in their impact on the legitimacy of democracy and the legitimacy that a specific democratic regime can command. Values and socio-economic modernization are a bridge for the developments, but also the reason for country differences (Inglehart and Welzel, 2005). The strong effects at the effectiveness level, however, raise doubts that the assessment of the current democratic regime is always a matter of pure legitimacy. If the influencing factors are placed in relation to one another, the importance of four factors becomes apparent. Economic modernization, in conjunction with the current guarantee of the rule of law, controls political support for the current democratic systems in Eastern Europe. Socialist legacies or a low degree of autonomy in society work against this.

Attitudes toward the current democratic system are strongly influenced by the performance of governments in the economic and political sectors. In these areas, citizens see the democratic system as having a duty (to fight corruption, to stand up for the common good, to create economic welfare). They use the fulfillment of these obligations as a yardstick for evaluating their political support. The general acceptance of democracy as a form of government is limited only when ideological factors (socialist legacies, rejection of the market economy) or structural-institutional deficiencies (restriction of the rule of law, presidential type of system) stand in its way (Lauth et al., 2000; Lauth, 2004; Kratochwil, 2006; Müller and Pickel, 2007; Pickel and Pickel, 2023). To all appearances, citizens do not expect half-measures from an established democracy. That is, if a democratic system is installed, it should guarantee freedoms and rights as well as appropriate structures. If this does not succeed, the population's willingness to grant the democratic form of government comprehensive legitimacy declines.10 This raises the question of how citizens understand democracy.

5 The understanding of democracy, desires, consequences—potential explanations

To what extent is it sufficient to focus the stability of democracies so strongly on their effectiveness, given that Lipset (1981) identified excessive dependence on citizens' assessments of effectiveness as problematic for the stability of democracy? Scharpf (1999) has far fewer problems in this regard. In a certain tradition of Easton (1979), he summarily identifies this area as output legitimacy. In other words, the rulers act in the interests of the citizens without their having to agree. The outcome is legitimized by the effectiveness of the implementation of the (normatively) shared political goals. This is to be distinguished from “input legitimacy”, which is aimed at the opportunities that a democracy grants its citizens for political co-determination. On the basis of democratic theory, input legitimacy can be given a certain (normative) priority. Nevertheless, it is completely open (from our point of view) which form is more important from the citizens' point of view for their social recognition of the current political system. After all, every citizen can have different demands on a democracy. Depending on such demands and the responsiveness of the rulers to them, the evaluation of the current situation then turns out differently.

There is always a certain gap between the desire for democratic rule and the prevailing situation in a system (Pickel, 2013, p. 188–189; Shin and Kim, 2018). However, it is precisely this gap that can now be decisive for the withdrawal of legitimacy for the existing democratic regime. For such a gap, however, it is then also decisive what one understands by democracy. Especially in recent years, some research has been established in the field of understanding democracy (Ferrin and Kriesi, 2016; Pickel S., 2016). For reasons of space, it is not possible to go into the results of this branch of research in detail here, moreover, since it is now a very differentiated research in terms of methodology and content. The countries surveyed in the European Social Survey 2012 and 2020 differ massively. Accordingly, statements for both years should not be viewed or compared as a development over time. This would only be possible at country level, which is also a separate article and not the aim of this report. Here, we primarily want to illustrate the different understandings of democracy in Europe.

A brief look at the results documented in detail elsewhere will help here: In addition to recognizing the existence of divergent understandings of democracy, what is most striking there is the finding of the strong dominance of the connection between democracy and individual freedom in the eyes of citizens (Table 3). Questions that force citizens to make a choice between different principles of democracy consistently reveal, for almost all countries surveyed, that individual freedom is of greatest importance for the recognition of democracy. The principles of freedom, justice, participation, rule of law and control are unanimously cited across countries as core features of democracy (Kriesi et al., 2016, p. 86–87). Under the decision-making conditions, freedom is consistently preferred to all other democratic principles.11 Consistent with Welzel's (2013) considerations, the aspect of individual freedom has high importance for understanding and valuing democracy (Dalton et al., 2007; Welzel and Alvarez, 2014). This corresponds with the desire for the protection of human rights as well as with the preference for free elections observed in many countries. With Ferrin and Kriesi (2016), the understanding of democracy can be divided into liberal, socially just, direct democratic and electoral. In 2020, items that can be described as populist were added to the ESS-Questionaire.12 This means that we have a broader understanding of democracy, but one that was partly surveyed in 2012 and partly only in 2020. For our illustrative purposes—we are not aiming for a time comparison—this is actually helpful as it gives us a broader overview. In reality, there are many mixtures of the dimensions of the understanding of democracy.

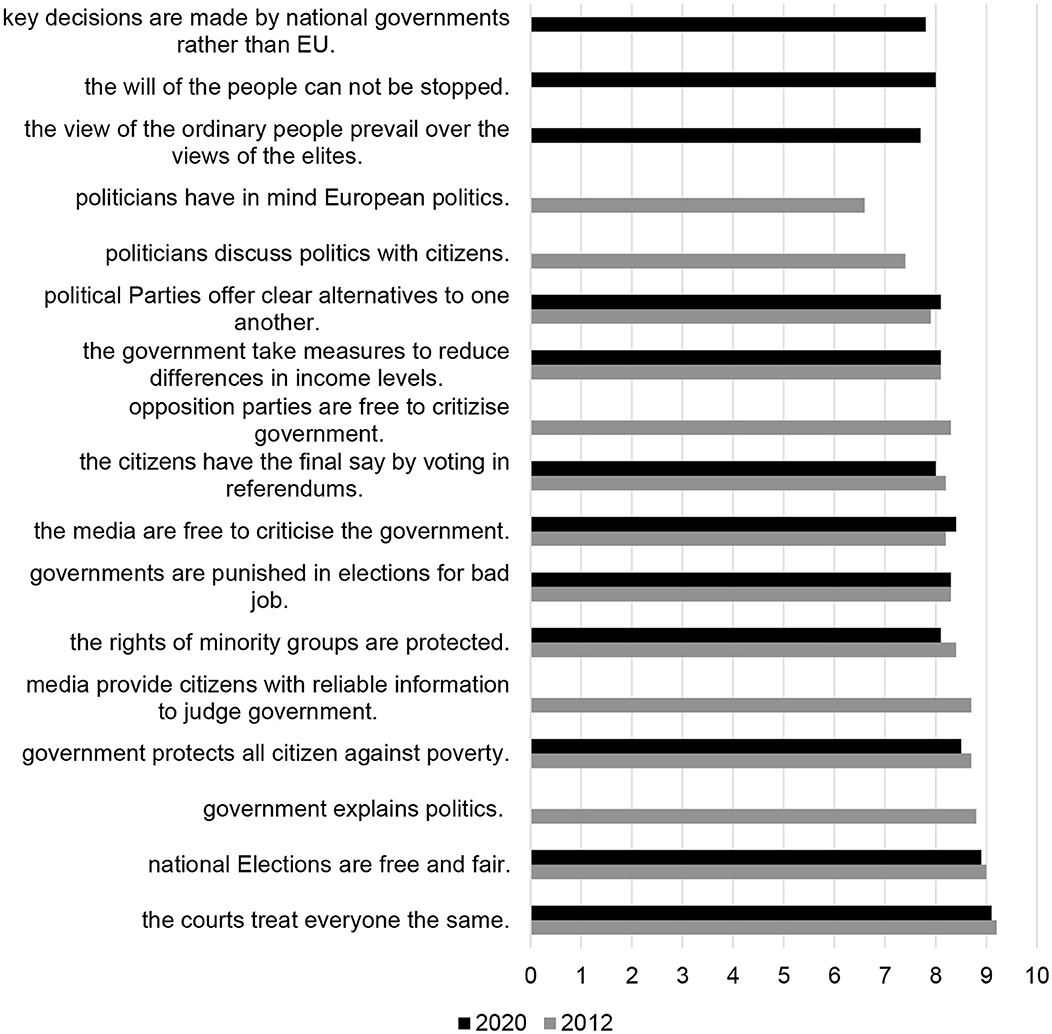

Overall, the (Western) understanding of democracy as a liberal democracy generally dominates. “There is a minimal common understanding of democracy that has diffused across Europe” (Hernandez, 2016, p. 63; Kriesi et al., 2016), “that the basic principles of liberal democracy are universally endorsed across Europe” Kriesi et al., 2016, p. 87). Also seen as important is an understanding of democracy that is more focused on social balance (Figure 5). On the first level of thought, i.e., normative legitimacy, citizens' wishes possess a high degree of consistency. Almost somewhat alarming is the almost equally high level of agreement with items that are now often framed as populist, such as “the will of the people cannot be stopped” (Mounk, 2018). Democracies are then measured against this target, or one could also say the legitimacy claim assigned by the citizen.

Figure 5. Target of democracy in the eyes of citizens in Europe in 2012 and 2020. Source: European Social Survey (ESS), 2012 and 2020; mean values of a scale with response options from 1 to 10; due to slight shifts in the survey countries, the mean values are not directly comparable as the underlying countries differ considerably between the two dates; Question: “Now some questions about democracy. Later on I will ask you about how democracy is working in [country]. First, however, I want you to think instead about how important you think different things are for democracy in general. There are no right or wrong answers so please just tell me what you think…”.

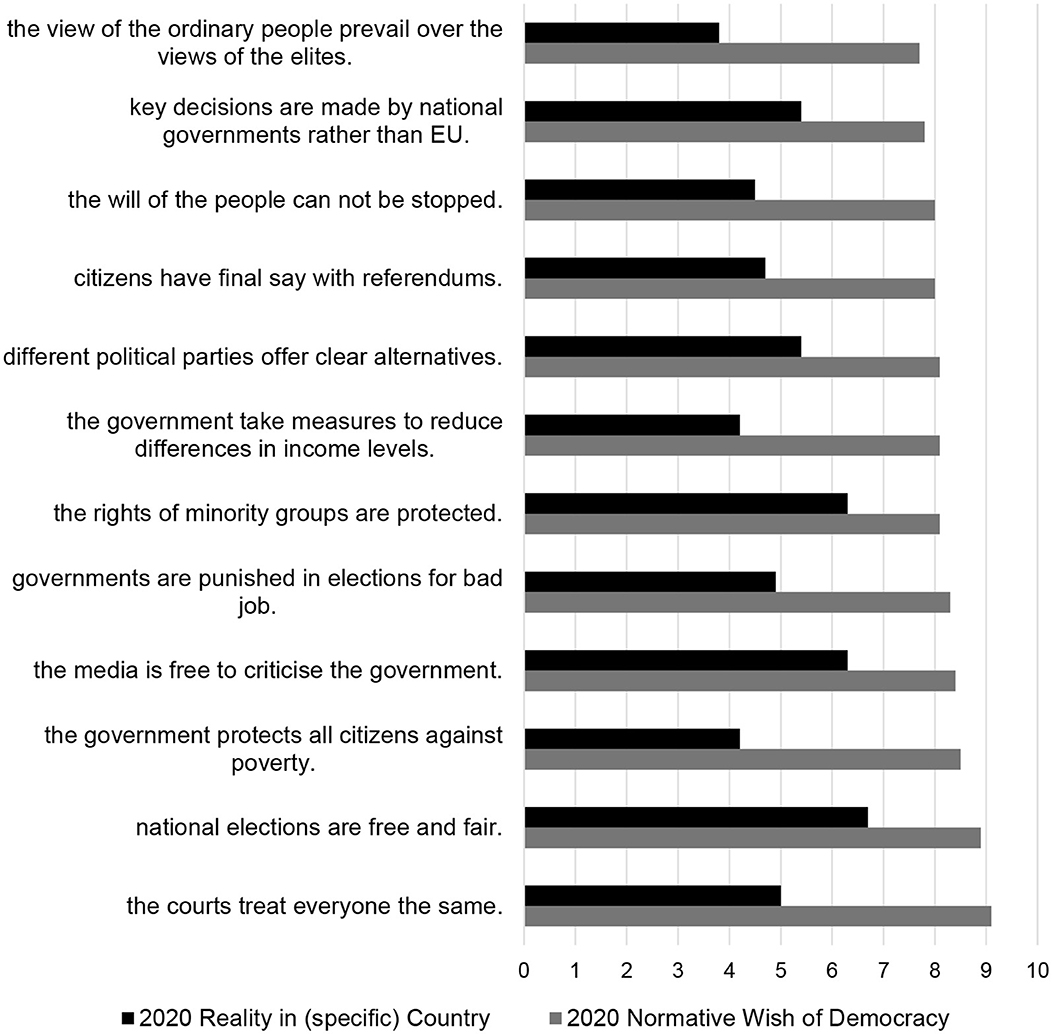

The actual state of affairs in one's own country, however, is judged less favorably, and the judgments show considerable fluctuations. If we recall the previous statements on the performance of democracy, this fits together well. Implementation in one's own country then prevents the transfer of the existing legitimacy of democracy as a form of rule to the current political system. Ultimately, the political system is said to have massive deficiencies in the implementation of democratic principles, regardless of the concrete institutional form they take. These deficiencies are differentiated. The greatest deficits are seen in the social sector and in the dimension of social justice. In their opinion, only a few governments succeed in sufficiently protecting their citizens from poverty or reducing income inequality. If aspects of a legitimacy crisis are to be identified for Europe, they lie in the social dimension. “But the main problem of democracies in Europe concerns the social dimension of democracy” (Weßels, 2016, p. 256). The protection of minorities, free and fair elections and freedom of the media are the most likely to be guaranteed. These are all classic rights in a liberal democracy. Probably the greatest difference is between the strongly desired social rights and their implementation, but also the populist statements, especially when they are directed against representative democracy and political elites (Figure 6). For an overall assessment, it is important to keep two things in mind: First, these are assessments of reality from the perspective of citizens. In other words, they are perceptions that do not necessarily have a one-to-one relationship with objective reality. This is where mediation and transparency of political actions are important. Secondly, it can be assumed that not all of the aspects mentioned are equally important. Freedom is presumably more important than the introduction of referendum decisions and expanded citizen participation. Even a large difference between the desired and actual democratic principles does not necessarily have consequences for the assessment of the political system or even for political action.

Figure 6. Democratic status of country in the eyes of the citizen 2020 in Europe. Source: European Social Survey (ESS), 2020; Mean values of a scale with answers from 1 to 10; What has been implemented of the dimensions addressed; Question: “Now some questions about the same topics, but this time about how you think democracy is working in [country] today? Using this card, please tell me to what extent you think each of the following statements applies in [country]. 0 means you think the statement does not apply at all and 10 means you think it applies completely”.

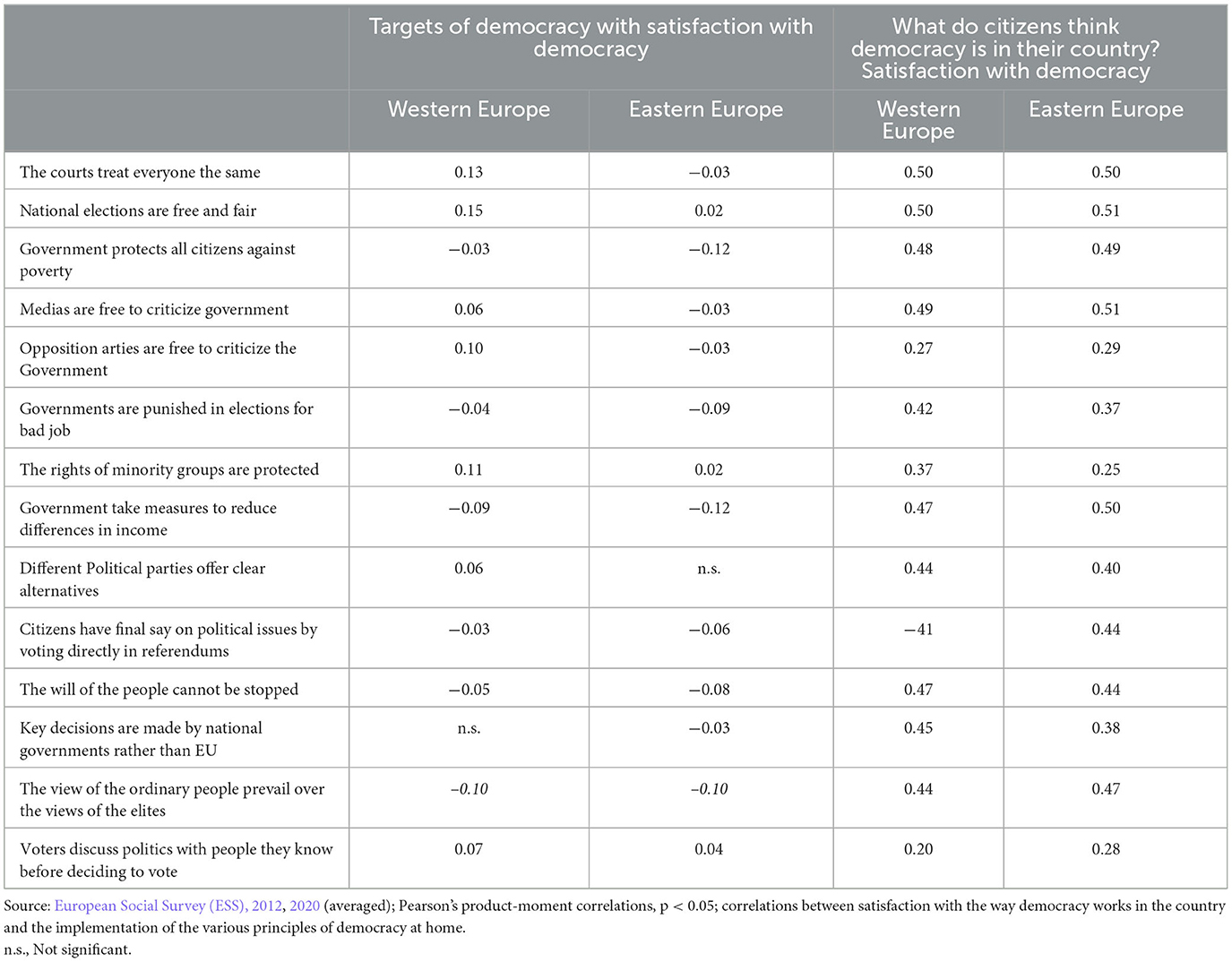

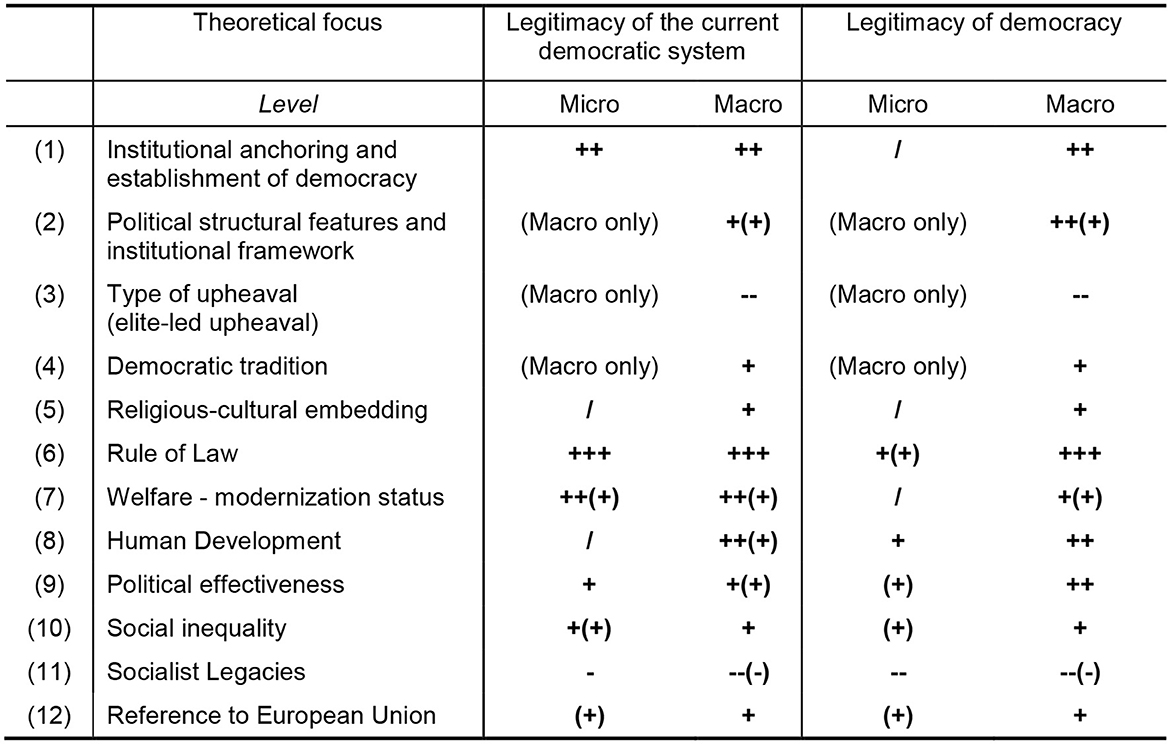

But what does this mean in terms of the current assessment of democracy? It can be assumed that the legitimacy of democracy is based more on normative expectations, while satisfaction with it is based more on the implementation of the desired rights in the country. Looking globally at the relationships between assessments of implementation in one's own country and satisfaction with democracy, it is clear that none of the elements of democracy are irrelevant to their assessment.13 Throughout, we find significant effects of the assessment of the implementation of elements considered important for democracy on democracy performance.14 The implementation of minority rights has the least effect on satisfaction with democracy and parliamentary trust. This indicates either a particular self-evident reason for not being satisfied, or a lower relevance of this democratic value for satisfaction with a democratic system due to a homogeneous national understanding. Remarkable is the simultaneous highest connection with the desire for such rights and the satisfaction with democracy (Table 4). Also positive is the association with liberal understandings of democracy and satisfaction with democracy. The implementation of equality before the law proves to be the strongest predictor of satisfaction with democracy. This now also means that not only economic satisfaction, but also satisfaction in the implementation of important democratic goals characterizes satisfaction with democracy.

Satisfaction with the current democracy has only a limited connection with the basic ideas of what a democracy should be like. This is theoretically plausible, as there is a difference between the ideas and the implementation. Unfortunately, the ESS data used for this purpose did not include any indicators for the legitimacy of democracy, which prevents such a measurement. What is interesting, however, is the reversal of the co-definer—albeit at a weak level—between the desired goal of democracy and clearly democratic values, or values that can be considered populist, such as Government are punished in elections for bad job, Citizens have the final say in referendums and the view of the ordinary people prevail over the views of the elites (Pappas, 2019).

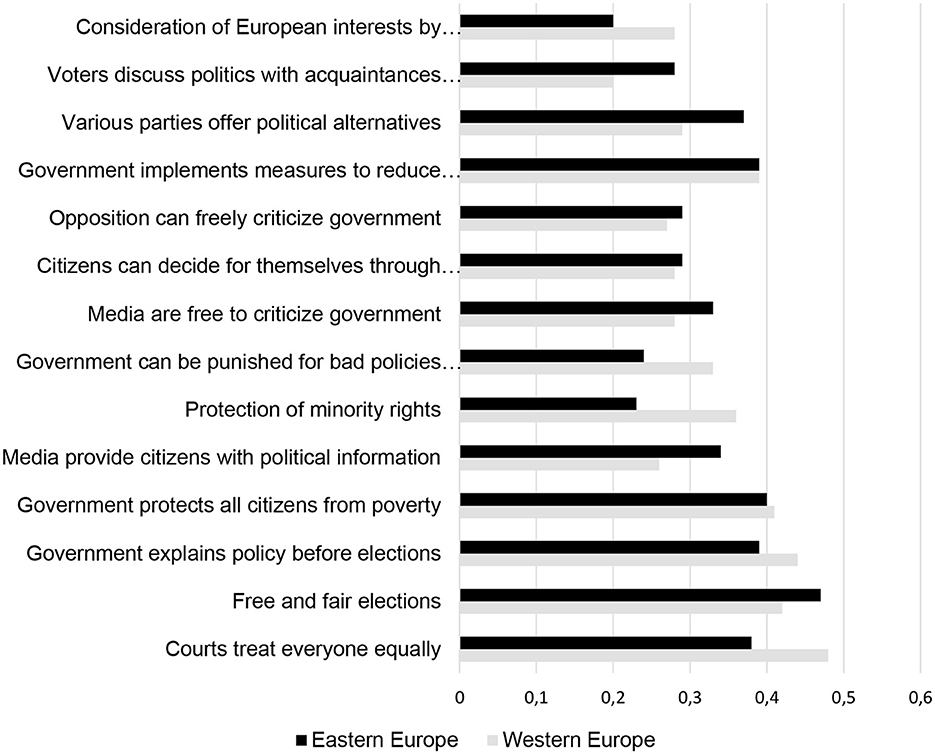

There are also differences in the West-East comparison. In Western Europe, equality before the judiciary is the dominant predictor, followed by politicians' willingness to be transparent and involve citizens, and free and fair elections (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Satisfaction with democracy and the effect of implementing the citizens' understanding of democracy in comparison. Source: European Social Survey (ESS), 2012, 2020 (averaged); Pearson's product-moment correlations, p < 0.05; correlations between satisfaction with the way democracy works in the country and The implementation of the various principles of democracy at home.

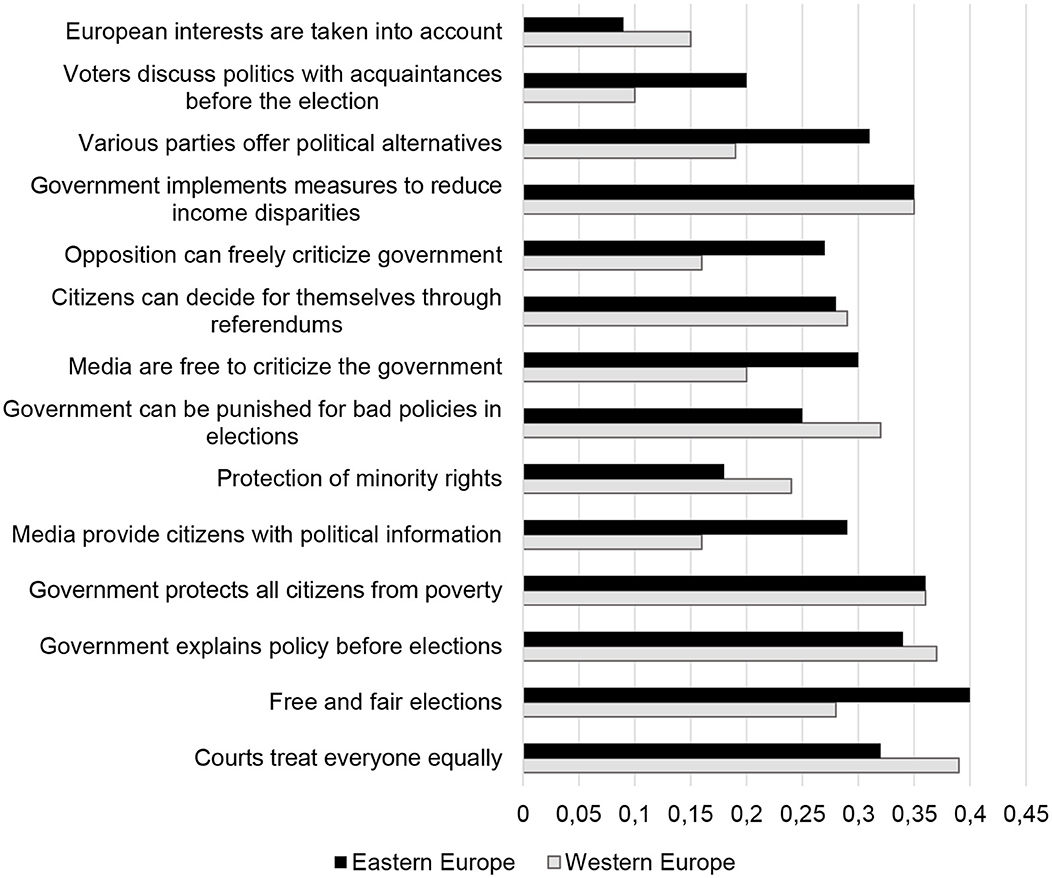

Combating social inequality and poverty follows almost equally. The other aspects lag somewhat behind these aspects. In Eastern Europe, the implementation of free and fair elections stands out with the strongest correlation from the group of democratic principles. This is followed by the social component of combating poverty and social inequality. Minority rights and the ability to punish a government for poor performance have a lower relative impact than these indicators, especially in Eastern Europe. This also somewhat explains the overall scores presented above. Overall, it can be shown beyond doubt for all countries that the implementation of the various aspects of democracy has an influence on satisfaction with it. This is remarkable because there are no significant correlations between the statement that living in a democracy is important to one and the corresponding indicators. The issue here is clearly the performance of the political systems under consideration. System support is more likely if the framework principles are implemented. This is hardly surprising, given the high importance assigned to these aspects. The question remains as to what extent differences between aspiration and reality lead to dissatisfaction with democracy and cause citizens to view it as only democratic to a limited extent. The correlations with this evaluation indicator in the ESS produce virtually congruent correlation values. The results are similar, as shown by the pattern in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Satisfaction with democracy and effects of differences. Source: European Social Survey 2012 and 2020 averaged); Pearson's product-moment correlations (inverted), p < 0.05; correlations between satisfaction with the way democracy works in the country and target-actual differences of the different principles of democracy.

Some of the differences between Western and Eastern Europe are now more evident in the correlations than in Figure 7. However, the differences remain within limits. The small differences from Figure 8 are not surprising, since Figure 4 had shown that actually all of the principles of democracy mentioned meet with a high level of approval in both Western and Eastern Europe. Consequently, the differences between reality and desire are based almost solely on the level of implementation. Judging the current state by this standard leads to differences in satisfaction with the current regime. Only the implementation of the principles in people's everyday lives leads to the transfer of the legitimacy of democracy to the legitimacy of the existing democratic regime. The regime can hope for system support only if it succeeds in tapping into the existing legitimacy of democracy as a form of rule.

6 Conclusion: legitimacy needs a proper understanding of democracy

Legitimacy is an important resource for any system of rule. Accordingly, all political regimes, whether autocracies or democracies, make efforts to gain trust among their citizens and generate belief in the legitimacy of their regime. To achieve this belief in legitimacy, they use different legitimation strategies. The distribution of economic support is just as promising a strategy as the dissemination of an ideology, the invocation of collective (national) identity or the striking reduction of social inequality. To achieve legitimacy among the population, two criteria must be met: First, the chosen strategy needs a normative reference. One can successfully invoke legitimacy by adhering to legal standards only if this is secured at the value level of the citizens—in other words, if it has normative legitimacy. But that is not enough. Normative anchoring is not sufficient if the concrete implementation is not recognized by the citizens in fact. Especially when a discrepancy arises between the normative claim and reality, the political system of rule is highly endangered in its existence in the long run and in the future. In order to achieve a correspondence between the normative and implementation levels, it is promising to establish an ideology that is recognized among the citizens and that can be implemented. Effectiveness in implementing the principles is thus an important component of legitimacy. Although this effectiveness can be evaluated from an observer's perspective, this comparison does not allow statements about future system maintenance. This requires empirical legitimacy, which refers to recognition on the part of citizens. The decisive factor is the factual recognition of the system of rule and its components by citizens in the sense of a belief in the legitimacy of the system. This belief can be based on different sources. It includes the result of a comparison of a normative legitimacy specifically recognized for the citizen with its implementation in reality, as well as considerations of the effectiveness of the system for the individual himself (and the community). Thus, neither is empirical legitimacy free of normative preconditions against which it is measured, nor are normative ideals sufficient in themselves to keep systems alive. In addition, there are different normative ideas on which the citizen bases his assessment of reality.

Liberal democracy has presented itself as a successful model in recent decades. The component of individual freedom in particular has considerable traction among citizens—and this in all parts of the world (Welzel, 2013). Certainly not detrimental is the equally widespread identification of democracy with economic prosperity. This link has a strong incentive for countries outside the Western world to turn to some form of democracy. The general recognition that democracy is the best form of rule for Africa and other areas of the world confirms this just as impressively as the already mentioned positive development of democratization since 1945 (see Huntington, 1991). At the same time, this success story does not mean that citizens always, completely and permanently agree with the prevailing implementation of this democracy. Nor does it mean that everywhere exactly the same composition of principles is understood by democracy and judged to be important. There are different weightings of what citizens believe a democracy must achieve. It is less a matter of differing understandings of what counts as democracy than of weighing the value of various elements against each other. For one person, individual freedom and economic success are more important than party competition or media freedom; for another, it is the other way around. Such a graded relationship to elements of democracy has hardly been surveyed empirically so far, but it corresponds to the reality of the world's understanding of democracy and the support that goes with it. This also explains the emergence of forms of “managed democracy” or limited problems of the populations in some countries to accept certain restrictions of basic democratic rights, which are normatively considered necessary, quite calmly.

Debates about the legitimacy crisis of Western democracies or the growing success of (right-wing) populist parties and politicians can be interpreted in this direction. As recognized as democracy is on the general level and as legitimacy can be, there is clearly a loss of legitimacy and trust in politicians and parties. If one speaks of a crisis of legitimacy, then in Europe's liberal democracies it is primarily representative democracy that is affected. People often no longer trust the “political establishment” to resolve political decisions in the service of the common good or to live up to existing normative expectations of democracy. Whether resulting radical changes in political preference and radicalizing protest behavior will bring about the desired change, however, remains doubtful. The desire expressed is not for less democracy, but ostensibly for more of certain components of democracy. This orientation is why even right-wing populists and other enemies of democracy use the term democracy and vehemently refer to the participation of the people. Accordingly, it is precisely the discrepancies between what is demanded of a democracy and what is seen that cause dissatisfaction among citizens.

Desires bring with them demands. Pharr and Putnam (2000) emphasized more than a decade ago that in Western democracies the demands for democracy, participation and responsiveness to citizens' interests have increased. However, they argue that parties and politicians are not fulfilling these demands to the same extent. The situation is problematic for democracies because their citizens think in changing terms: Existing democratic gains are taken for granted and no longer threatened by loss. They now want to add to these gains. In other words, with more democracy come greater demands on democratic systems. If these demands are not met to the extent that is sufficient from the subjective point of view, then there will be a withdrawal of political support from the rulers and a loss of legitimacy for the political authorities. If there are no political alternatives that are better able to meet the demands, this can lead to a loss of legitimacy for the political system. The legitimacy of democracy as the most appropriate form of government is little affected by this, but it is only of limited value in protecting democratic regimes, for example, when populists claim to want to improve democracy. In order to be closed to this, citizens must already have the impression that populists are endangering other gains from democracy. Other forms of government are also subject to similar problems, since they are measured against the normative claims they represent. A socialist system is expected to reduce social inequality in addition to promised economic improvements, and a theocratic system aligns its laws and actions with God. This may not lead directly to a collapse of the political regime, but it lays the groundwork for it once other necessary factors occur (powerful opposition, difficult transition of rule, economic crisis, foreign intervention, etc.).

Empirically, we find no factual evidence of a legitimacy crisis of democracy as a form of rule in European democracies. Now, the analyses presented were largely limited to Europe, and claims may vary outside Europe (Pickel S., 2016). However, the ruling form of democracy has high legitimacy outside Europe as well. Thus, the system support of democracies in and outside Europe is not per se assured, as it often depends strongly on their effectiveness, which means not only the economic, political or social output, but also the translation of norms into real political systems from the citizens' perspective. For empirical legitimacy, the objective implementation of a democratic legal system on paper is necessary; citizens must feel that it has been implemented accordingly. This is not the case for all citizens, not even in Europe. Thus, signs of a crisis in the political implementation of democratic regimes can be found here and there. This is more pronounced in Eastern Europe than in Western Europe, which can be explained by the dependence of system support on socioeconomic and political crises. If corresponding erosions of system support can be interpreted as a crisis of legitimacy, they almost never affect the principles of liberal democracy, but primarily—but there often clearly—the dimension of social democracy (also Weßels, 2016). The effectiveness of the implementation of democracy is thus decided against the backdrop of its legitimacy: a system collapse of a political regime occurs through a lack of system support. This mechanism applies to democracies and non-democracies.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://ess-search.nsd.no/.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Ferrin and Kriesi (2016, p. 10–13) rank the congruence of desires and evaluations as the core of legitimacy. In some places, this falls short of Weber's considerations on legitimacy belief and possibly underestimates the influence of alternative conditioning factors of political stability.

2. ^Conversely, legitimacy at the level of social recognition does not ensure normative legitimacy.

3. ^In autocratic or semi-autocratic political regimes, citizens' trust in interviewers is not likely to be as high due to concerns that their own person may be endangered or due to a lack of freedom of expression. Consequently, the results should be interpreted with caution.

4. ^The question arises whether the successes of democracy do not spark rising aspirations among its citizens. For example, increases in prosperity are no longer sufficient if they are not fairly distributed or if no improvement in living standards can be achieved. These are relations that shift and thus undermine system support (and possibly the legitimacy of concrete democratic systems) in the eyes of citizens.

5. ^Variations in answers then result predominantly from variations in the formulations of the questions. Thus, softer formulations (it is good to live in a democracy, democracy is the most appropriate form of government) lead to a somewhat more positive response behavior than somewhat stricter formulations (the idea of democracy is always good).

6. ^Westle (1989) classifies these indicators as diffuse-specific in Easton's (1975) model.

7. ^The correlation between the indicator satisfaction with democracy in one's own country and the assessment of how democratic the country is in the European Social Survey is r = 0.73 at the global level across the individual data of all countries.

8. ^As the presentation of all the analyses would go far beyond the scope of this article, a symbolic, cumulative presentation of all the results has been used here. It seems to us that this is the best and most comprehensible way to illustrate the main interest, i.e. the presentation of the macro-level trends. Incidentally, a presentation of the various analyses would take up 26 pages. The results of the various analyses overlap considerably, but the corresponding indicators are not available for all years.

9. ^Due to the compilation of data from different datasets and limited sizes for the macro level, a multi-level analysis was not performed.

10. ^However, the high approval ratings for democracy as an appropriate form of government show that the “enemies of democracy” are predominantly minorities.

11. ^Comparable results can be extracted for many African countries via the Afrobarometer data series (Bratton et al., 2005; Cho, 2015; Pickel G., 2016, p. 9–12; Pickel S., 2016, p. 321). These results become even more concise in the direction of a Western understanding of democracy in 2008 with response vignettes and in 2011 and 2014 with predetermined response specifications (http://afrobarometer.org/online-data-analysis/analyse-online).

12. ^This is also one reason why we present both data sets despite the different cases studied. The result is a broader overview of citizens' understanding of democracy.

13. ^Unfortunately, only democracy performance is mapped in the ESS data.

14. ^Democracy performance is measured by the answers to the question “Overall, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in your country?”

References

Acemoglu, D., and Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. New York, NY: Crown Publishers.

Almond, G., and Verba, S. (1963). The Civic Culture. Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bratton, M., Mattes, R., and Gyimah-Boadi, E. (2005). Public Opinion, Democracy, and Market Reform in Africa. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Braun, D., and Schmitt, H. (2009). “Politische Legitimität (Political legitimacy),” in Politische Soziologie. Ein Studienbuch (Political Sociology. A Study Book), eds. V. Kaina and A. Römmele, (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag), 53–81.

Cho, Y. (2015). How well are global citizenries informed about democracy? Ascertaining the breadth and distribution of their democratic enlightenment and its sources. Polit. Stud. 63, 240–258.

Dalton, R., Shin, D. C., and Jou, W. (2007). Understanding democracy: data from unlikely places. J. Democ. 18, 142–156. doi: 10.1353/jod.2007.a223229

Diamond, L. (1999). Developing Democracy. Toward Consolidation. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Diamond, L. (2008). The democratic rollback. The resurgence of the predatory state. Foreign Affairs 2, 36–48.

Easton, D. (1975). A re-assessment of the concept of political support. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 5, 435–457. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400008309

Eckstein, H. (1988). A culturalist theory of political change. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 82, 789–804. doi: 10.2307/1962491

Ferrin, M., and Kriesi, H. (2016). How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flanagan, S. (1987). Value change in industrial societies. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 81, 1303–1319. doi: 10.2307/1962590

Fuchs, D. (1989). Die Unterstützung des politischen Systems der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (The support of the political system of the Federal Republic of Germany). Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Fuchs, D. (2002). “Das Konzept der politischen Kultur: Die Fortsetzung einer Kontroverse in konstruktiver Absicht (The concept of political culture: the continuation of a controversy with constructive intent.),” in Bürger und Demokratie in Ost und West: Studien zur politischen Kultur und zum politischen Prozess (Citizens and Democracy in East and West: Studies on Political Culture and the Political Process), eds D. Fuchs, E. Roller, and B. Weßels (Opladen: Leske + Budrich), 27–49.

Fuchs, D. (2004). “Models of democracy: participatory, liberal, and electronic democracy,” in Democratic Theory and the Development of Democracy, eds A. Kaiser and T. Zittel (Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag), 19–53.

Gasiorowski, M. J. (2000). Democracy and macroeconomic performance in underdeveloped countries. An empirical analysis. Comp. Polit. Stud. 33, 319–349. doi: 10.1177/0010414000033003002

Gerschewski, J. (2010). “The three pillars of stability. Towards an explanation of the durability of autocratic regimes in East Asia,” in Paper Presented at the 106th Annual Conference of the American Political Science Association. Washington.

Gerschewski, J., Merkel, W., Schmotz, A., Stefes, C., and Tanneberg, D. (2013). “Wie überleben Demokratien? (Why do dictatorships survive?),” in Autokratien im Vergleich (Autocracies in Comparison), eds. K. Steffen, and P. Köllner (Baden-Baden: Nomos), 106–131.

Hadenius, A., and Teorell, J. (2007). Pathways from authoritarianism. J. Democ. 18, 143–156. doi: 10.1353/jod.2007.0009

Hernandez, E. (2016). “Europeans' view on democracy: the core elements of democracy,” in How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy, eds. F. Monica, and H. Kriesi (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 43–63.

Huntington, S. P. (1991). The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. New York, NY: Norman.

Inglehart, R. (1971). The silent revolution in Europe: intergenerational change in post-industrial societies. Am. Politic. Sci. Rev. 65, 991–1017.

Inglehart, R. (1988). The renaissance of political culture. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 82, 1203–1230. doi: 10.2307/1961756

Inglehart, R. (1990). Cultural Shift in Advanced Industrial Society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, R., and Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy. The Human Development Sequence. Cambridge: University Press.

Kailitz, S., and Köllner, P., (eds.) (2013). Autokratien im Vergleich (Autocracies in Comparison). Special issue 47 of Politische Vierteljahresschrift. Baden-Baden: NOMOS.

Klingemann, H.-D., and Fuchs, D. (1995). Citizens and the State. Beliefs in Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kriesi, H. (2013). Democratic legitimacy: is there a legitimacy crisis in contemporary politics? Polit. Vierteljahres. 54, 609–638. doi: 10.5771/0032-3470-2013-4-609

Kriesi, H., Saris, W., and Moncagatta, P. (2016). “The structure of Europeans' view of democracy: Citizens' models of democracy,” in How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy, eds. F. Monica, and H. Kriesi (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 64–89.

Lauth, H.-J. (2004). Demokratie und Demokratiemessung. Einne kozeptionelle Grundlegung für den interkulturellen vergleich (Democracy and democracy measurement: a conceptual grounding for cross-cultural comparison). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Lauth, H.-J., Pickel, G., and Welzel, C,. (eds.) (2000). Demokratiemessung. Konzepte und Befunde im internationalen Vergleich (Measuring democracy. Concepts and Findings in international comparison). Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some social requisites of democracy: economic development and political legacy. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 53, 69–105. doi: 10.2307/1951731

Mounk, Y. (2018). The People vs. Democracy. Why our Freedom is in Danger and How to Save it. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Müller, T., and Pickel, S. (2007). Wie lässt sich Demokratie am besten messen? Zur Konzeptqualität von Demokratie-Indizes (How can democracy best be measured? On the conceptual quality of democracy indices). Polit. Vierteljahres. 48, 511–539. doi: 10.1007/s11615-007-0089-3

Nohlen, D. (2002). “Legitimacy,” in Encyclopedia of Political Science. Vol. 1, eds. N. Dieter, and R.-O. Schultze (Munich: Beck), 467–477.

Norris, P. (1999). Critical Citizens. Global Support for Democratic Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norris, P. (2011). Democratic Deficit. Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pappas, T. (2019). Populism and Liberal Democracy. A Comparative and Theoretical Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.