- Department of Social Sciences, Humboldt University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Methodological nationalism can be understood in the broadest sense possible as any kind of correspondence between society and the unit of the nation-state. This equation can be traced and understood at two levels: firstly, within the socio-historical context of the rise of nationalism and the development of human and social sciences; and secondly, within the cognitive context of the emergence of nationalism and these sciences, or the modern episteme, in other words. By focusing on the latter, the present article aims to indicate that the problem of methodological nationalism can be effectively grasped by exploring the intricate interplay among modernity, the discourse of nationalism, and the emergence of social science, particularly concerning the modern episteme. It becomes apparent that the regime of foundationalist differentiation ingrained within the modern episteme has established the foundation for this correspondence or congruence—a regime that, while constructing determined, regulated, unified and completed categories, such as society and the social/nation-state and the national, simultaneously sets the ground for the exclusion of other non-social/non-national phenomena and events. In this paper, the objective is to demonstrate how, by disclosing the implementation of this regime as well as highlighting the contingent nature and, consequently, the conditions of the possibility of social phenomena in the path of their grounding, alongside prioritizing the indeterminate social configurations and arguing for a post-foundationalist approach and the politics of transnationalism, it becomes possible to overcome the problem of methodological nationalism. This, in turn, sets a basis for taking into account excluded and indeterminate phenomena and actors within a global context.

1. Introduction

The contemporary world is witnessing a confluence of phenomena which, on one hand, constitute the origins of profound transformations and, on the other hand, serve as manifestations of global-scale societal shifts. Remarkably, alongside their extensive sphere of influence, these phenomena present an analytical challenge to conventional approaches within the realm of social studies. Their uniqueness and novelty are primarily ascertained in their relation to conventional categories within social sciences, and they shine by their transcendence of established units such as the national, local, and international. These phenomena defy easy classification within a single or dual categories; they traverse and interconnect diverse categories and entities in a manner that disrupts the prevailing rationale of social analysis and conceptualization. The emergence or resurgence of these phenomena underscores the need to scrutinize some of the fundamental epistemic axioms and assumptions underpinning much of the social sciences.

The imperative to conceptualize phenomena and forces that exceed the bounds of established analytical categories is conspicuously evident in contemporary academic contributions (Featherstone, 1991; Seidman, 1994, 2008; Albrow, 1996, 2004; Giddens, 1999; Robinson, 2001; Held and McGrew, 2003; Latour, 2005; Dicken, 2007; Held, 2010; Beck, 2016b,c; Bauer, 2022; Jong, 2022b). This imperative encompasses not only empirical subjects of study, but also the perspectives and methodologies employed by scholars themselves. The initial stride in grappling with this quandary involves addressing its underlying origins. One of the principal wellsprings of this challenge stems from the fact that modern social science, along with its central analytical categories encompassing society, state, nation, solidarity, rationality, class, territory, power, and more, has evolved over centuries of nation-building. Stated differently, the foundational categories of social sciences were integrally woven into the fabric of crafting the idea of the nation-state or the ideal of state/nation congruency in Western Europe (Giddens, 1973; Toulmin, 1990; Calhoun, 1999; Wimmer and Glick Schiller, 2003; Beck and Sznaider, 2006; Chernilo, 2006; Mandelbaum, 2020).

These categories and their logic of analysis carried the concerns of the age that were supposed to reorganize human communities in different forms of nation-state or national entities. While this mode of inquiry still furnishes insights for appraising and, in some cases, critiquing diverse social phenomena from a nationalistic vantage point, it selectively accentuates certain facets of political, social, and economic phenomena while neglecting or distorting others. By disregarding or excluding aspects of the (internal and external) non-national—such as the religious, irrational, traditional, ethnic, oriental, contingent, singular, transnational, and minor—modern social theory, influenced by the national episteme, has been rendered incapable of conceiving singular non-national or transnational phenomena, non-national rationalities and concepts, mobility and transnational interdependence, immigrants and strangers, as well as transnational and global entities and influences. Through an exploration of how methodological nationalism has shaped modes of categorization and conceptualization of the social world, we can fathom the epistemic consequences of nationalism and the course of nation- or state-building within the realm of the social sciences.

Methodological nationalism can be defined as “the naturalization of the nation-state by the social sciences” (Wimmer and Glick Schiller, 2002, p. 301; Wimmer and Glick Schiller, 2003, p. 576). It equates societies exclusively with nation-state societies, and by assuming a kind of regime of state/nation congruency (Mandelbaum, 2020), it casts states and their governments as the primary focus of social-scientific analysis (Robinson, 1998). Methodological nationalism posits that the nation, state, and society are the natural social and political forms of the modern world (Beck, 2006, p. 24; Beck and Sznaider, 2006, p. 383). It is presumed that humans are naturally organized into a certain number of nations, each of which constructs itself internally as a nation-state and sets exterior boundaries to separate itself from other nation-states (Beck, 2006, p. 24; Beck and Sznaider, 2006, p. 383). Even in the context of comparative studies, society and its constituents, alongside their historical development, are conflated with the nation-state, its components, and its historical trajectory. The competition of interests among societies is thus interpreted exclusively through the lens of conflicts between national interests. This perspective embodies a nation-state-centric viewpoint on matters of society, politics, law, justice, and history, thereby shaping the contours of sociological thought. Yet, it is precisely this methodological nationalism that obstructs the capacity of social sciences to delve into the fundamental dynamics of modernization and globalization, both in historical retrospect and in contemporary times (Beck, 2007, p. 287).

Methodological nationalism, or the naturalization, fetishization, and reification of the nation-state, or the congruence of state, society, and nation, has cognitive, practical, discursive, and institutional implications and manifestations; epistemological as well as sociological forms that have caused different scholars and policymakers to put nation-states as the starting point of their analysis. Although the relationship between the modern state and national units have been subjected to history and different social contexts, the formation of society or macro-national units in the modern era, whether in the process of nation-building or in the process of state-building, has always been accompanied by the employment of significant amounts of violence to establish and maintain state/nation/society boundaries, form and preserve national identities, and reorganize and demarcate people under different form of national entities. Ethnic cleansing, population movements and mobilizations, genocide, programs of assimilation or integration, and different regimes of homogenization are cases that have been associated with the project of nation-state-building. Besides that, the project itself set the stage for the greatest mobilization of social and economic resources and capital for the purpose of domestic or external conflicts. “Within the context of the nation-state,” as Adamson (2016, p. 22) puts it, “violence, collective identity, and territory come together in a particular configuration in which a political unit can be conceived of as a territorially defined corporate agent.” Above all, this historical convergence has manifested itself in the dominant mode of conceptualization and theorizing in the modern social sciences, a conceptualization that presupposes a specific relationship between territory (space), identity, and the construction and maintenance of collective (here national) configurations.

The dominant categories of modern social sciences are themselves the outcome as well as the agents of the process of nation-state building that hide the aforementioned correspondence or congruency and carry a special ontology of the social, that is, an ontology that relies on nation-states as the primary units and actors (Adamson, 2016). The methodological nationalism embedded within these categories can be influential in everything from the way of defining social phenomena to the way of collecting and producing quantitative and qualitative data. Migration, for example, is conceptualized and investigated as occurring phenomenon either between nation-states or within national entities. The factors that cause or have an impact on population mobilities are also interpreted primarily on this basis. Quantitative studies of migration are similarly spatialized based on the national context, treating states or national entities as autonomous variables existing in a precisely demarcated national society separated from larger global forces. Even migration policies or global databases on international migration are produced based on the specifications of national (and sometimes ethnic) units. However, international mass migrations in the contemporary world have not only been the result of cosmopolitan trends such as environmental crises or transnational conflicts, but they have also been the cause of some of the greatest global transformations that cannot be properly understood by drawing on traditional social science categories such as nation, class, identity, and so on. In reality, a very complex and intertwined network of relationships and variables at different levels leads to the construction of a configuration that we can call migration. In other words, migration is a transnational configuration, and although it is rooted in existing entities and structures, goes beyond them and, at another level, constructs a new reality with broader implications (Jong, 2022a).

It also can be shown how using the nation-state as a key unit for developing statistics, data, graphs, and other measurements in empirical studies in the social sciences may entails in turn serious problems and has deep moral, legal, and scientific implications. This is well-exemplified in the way the impact of each state on runaway climate change is currently measured. For instance, China, the United States, India or any other country are considered as single units without consideration the fact that each unit, each nation-state is subdivided into wildly different areas. More specifically, GHGs emissions reach their peak within specific regions, while they can be nearly insignificant in other regions of the same nation-state. Even more complicated, as less easily measurable, are class, gender, religion, profession and other variables and sub-variables which are not taken into account when measuring GHG emissions allocated to specific nation-states. A focus on the various manifestations and implications of methodological nationalism, as well as attempts to suspend this bias, allows for the possibility of bringing alternative categories, modes of analysis, spaces, actors, unites, and so on into the mainstream of social inquires. Scholars in different fields of the social sciences are required to revisit how they deal with fundamental questions about how social phenomena are constructed and imagined, and try to be aware of the consequences of this revisiting for their theorizing.

By taking into account the ontological, epistemological, and normative aspects of methodological nationalism, many scholars have striven to propose solutions to overcome the predicament. From changing units of analysis in social sciences and referring to pre-modern units such as ethnie (Smith, 1986), civilization (Arjomand and Tiryakian, 2004; Arjomand, 2014), and empire (Negri and Hardt, 2000), from applying transnational (Faist, 2012; Amelina and Barglowski, 2018), multi-sited (Marcus, 1995) and cross-border (Amelina et al., 2013) methodologies to defining new entities such as world society (Meyer et al., 1997; Meyer, 2018), global field (Go, 2008) and world system (Wallerstein, 2004), from changing the unit of reference from nation-state to cosmopolitan terrain (Beck and Sznaider, 2006; Beck, 2007, 2016b) or prioritizing the relativist conception of space and time (Pries, 2007) to historicizing the idea of society, nation-state (Marjanen, 2009; Conrad, 2016), and the relation of the nation-state to modernity (Chernilo, 2006, 2011), to examining and criticizing the moral manifestations and consequences of methodological nationalism (Dumitru, 2014), to deconstructing the nation/state congruency through a psychoanalytical genealogy of nationalism (Mandelbaum, 2020), to proposing alternatives such as methodological cosmopolitanism and methodological transnationalism (Hellman, 2014; Blok and Selchow, 2020), all have aimed to overcome this bias, and by providing alternatives, set the ground to make sense of the phenomena, forces, actors, ideas and traditions that have been discarded or reconstructed by methodological nationalism. Considering a kind of relationship between modernity, the nation-state, and the emergence of modern social sciences is something that is common among many critiques of this bias. Many of the proposed solutions are also expressed based on different variations of this ratio.

But from a Foucauldian approach (Foucault, 1966), it can be seen that a true understanding of the simultaneity and parallelism of these three phenomena, namely modernity, the dominance of nation-states, and the emergence of modern social sciences, is essentially accessible by digging deeper and touching the cognitive context of the modern episteme. On the other hand, much of the criticism and solutions that methodological nationalism has elicited are still rooted in modern epistemic assumptions and are, in some ways, plagued by its cognitive predicaments. Based on the main pillars of the modern episteme, the human and social sciences consider their objects as positive, given, and ultimate units that are fundamentally meaningful in distinction with other objects, especially against singular and indeterminate events. When it comes to this episteme, objects such as society and the nation-state are considered separate, universal, given, and regulated entities, units that entertain universal laws and relations, and their developments are interpreted based on a kind of teleological approach.

At the other level, in this mode of interpretation, both human centrality and “founding totality” (Laclau, 1990, p. 90) are considered the ground for understanding societies around the world. In order to conquer and control nature as well as himself, modern man must, first of all, know the order that governs the world, his individual as well as collective life, and accordingly, construct analytical categories that could explain this regularity. By drawing on the idea and prominent features of the modern episteme, the current article aims to illustrate that taking into account the basic requirements of the modern episteme, and its related human and social sciences, is the inescapable starting point for any critique wishing to lay claim to an understanding of the problem of methodological nationalism.

Drawing on the idea of Foucault's epistemes (Foucault, 1966), this article attempts to go further and reveal that an effective understanding of the problem of methodological nationalism, as well as the relationship between modernity, the nation-state, and the emergence of social sciences, can be achieved primarily by positioning them within the modern episteme. In this way, nationalism is pondered as the dominant discourse in the modern episteme, a discourse that emerged simultaneously and on a similar cognitive basis to the human science and so, in addition to their cognitive similarities, it was able to impose many of its requirements on this science. Through a regime of foundationalist differentiation that is rooted in the modern episteme, this discourse, as well as modern human science as a scientific discourse, has excluded many non-national events (ethnic, irrational, conditional, transnational), while, at the same time, proposing regulated and positive units such as nation, society, state, sovereignty, territory, etc. as the central objects of social sciences. Furthermore, in relation to this episteme, the ideal of state/nation/people congruency and the genealogy of its various manifestations, which dominated most ideologies as well as theories of nationalism, will be discernable. Dealing with this predicament requires, on the one hand, the deconstruction of this discourse as well as the congruency in general and, on the other hand, the suspension of the positivistic idea of society in particular.

By reviewing various accounts of the problem of methodological nationalism, accordingly, the current article attempts to address this bias in close relation to the modern episteme, modern human sciences, and the discourse of nationalism (Foucault, 2003). Drawing on the major notions and distinctions that are outlined by Foucault in Orders of Discourse (Foucault, 1971), the internal and external techniques of control and homogeneity that are exercised by nationalist discourses will be described. By elucidating and subsequently critiquing the modus operandi and functional dynamics of the modern episteme's regime of differentiation, the philosophy of post-foundationalism is presented as an alternative framework. This presentation serves as a means to transcend the imperatives of the modern episteme, indicating the implications of this philosophy in suspending methodological nationalism within the realm of social sciences. By prioritizing the contingency of the social and political categories and entities, as constructed categories in the incomplete process of grounding the social, in this philosophy, the conditions of possibility of these categories take precedence through social analyses, and thus, rather than considering these categories as given, determine, bounded, and a priori entities, they are considered as heterogenous, a posteriori, and indeterminate configurations. Finally, it is demonstrated that, in addition to providing a ground for overcoming the problem of methodological nationalism, this deconstruction will open up new avenues for comprehending non-national events and forces, including transnational phenomena and the primacy of a politics of transnationalism in the era of cosmopolitanization of the world.

2. Methodological nationalism

In recent decades, the social sciences have faced heightened criticism. Both Eurocentrism and methodological nationalism have come under extensive scrutiny from critics (Chakrabarty, 2000; Mignolo, 2002; McLennan, 2003; Connell, 2007; Chernilo, 2008; Alatas, 2016; Beck, 2016a; Go, 2016; Gutierrez Rodriguez et al., 2016; Jong, 2022b). The driving force behind these critiques is 2-fold: on one hand, the social context that the social sciences have traditionally focused on has undergone profound transformations, and on the other, distinctive forms of knowledge have challenged the dominance and authority of these sciences. Many concepts and categories within the social sciences have lost their efficacy in understanding various emerging global phenomena, as well as the resurgence of indigenous and singular phenomena. A retrospective examination of the history of social sciences reveals their emergence within a specific period of modernity, responding to unique challenges primarily in Western and imperial Europe (Connell, 2007). Through the process of their consolidation, often ignoring their historical implications, these sciences tried to present themselves as objective, universal, and trans-historical sciences. Consequently, Eurocentrism and then methodological nationalism became deeply ingrained and unquestioned elements within numerous empirical and theoretical analyses in the field of social sciences. The escalating density of global trends, accompanied by cross-border flows, shifts in the roles of many dominant and national institutions and entities, and the emergence of new social formations, have propelled the issue of methodological nationalism to the forefront of social critiques (Held, 1999; Albrow, 2004). Scholars from varying perspectives and disciplines have endeavored to acknowledge the existence of methodological nationalism, while examining and criticizing the core and consequences of this issue, and offering solutions and alternatives to tackle it.

Methodological nationalism can be understood in the broadest sense possible as any kind of equality or correspondence between society and the unit of the nation-state (Smith, 1979). According to Chernilo (2006, 2008, 2011), who has done one of the most brilliant studies on the problem of methodological nationalism, this equality can be traced on two levels: from the historical perspective, the nation-state has established itself as the dominant, natural, and essential form of society in modernity; and from the theoretical point of view, social science has deployed taken-for-granted national templates and categories to construct its most abstract idea of society. Along with the spread of nationalism as well as the consolidation of the nation-state system on a global scale, society became largely synonymous with the self-closed entity of the nation-state, the social was equated with the national, and the social context was considered the national/inter-national context. Gradually, this equation became a priori and was taken for granted. In this milieu, the broader realm of social sciences, especially sociology, is founded upon the notion of “society” as a self-contained territorial construct coextensive with the nation-state (Inglis and Robertson, 2009; Pyyhtinen, 2010, p. 23-24). The social is presupposed as an even explanatory, independent variable that is external to the objects of study, and thus, in relation to the social, the indeterminate and the contingent become either meaningless (here based on the national) or their being and meaning become justified in relation to it. To varying degrees, a kind of methodological nationalism is conceivable among both classical and later social theorists (Martins, 1974; Calhoun, 1999; Wimmer and Glick Schiller, 2002, 2003; Beck and Sznaider, 2006; Chernilo, 2008; Beck, 2016c). Methodological nationalism allowed these theorists to “treat societies as if they were coherent and bounded entities, distinct from one another, and contained within the territories of nation-states” (Nash, 2010, p. 63). According to Beck (1999, 2016c), a territorial conception of modern society—a conception of society that is centered on the nation-state and equates it with a territorial national entity—has penetrated throughout sociology and the social sciences in general. The nature, quiddity, and place of the social will also be defined in the context of society as a bounded and nationalized entity. In this way, society is imagined as a kind of “container” within which our practices and social relations are assumed to fit (Beck, 1999; Chernilo, 2006; Pyyhtinen, 2010). The relationship between the social science, modernity, and the nation-state shifted to the point that the regime of the nation-state corresponded with modernity and any social explanation required a reference to the nation-state's elements, entities and regime of truth. Although this correspondence was structured for a specific period in Western Europe and North America, its extension to other times, places and spaces became one of the main sources of the bias of methodological nationalism.

In a different confrontation, Mandelbaum (2020) attempts to interrogate this predicament through the ideal of nation/state congruency. He argues that a kind of congruency between the state/nation has been assumed or imagined in modern thought, a congruency whose genealogy can be traced in the early ideas of modernity, especially from political philosophy of the 18th century onwards. This embedded congruency, which has resulted in the correspondence of society with the nation-state in modernity, has manifested itself in various forms of nationalism, international politics, multicultural policies, development theories, modernization theories, international security theories, and so on, and has been the source of some misunderstandings and practical policies in the modern world in the recent centuries. In general, any revisiting of social thought in order to bring it in line with current globalized ground has called for considering the special relationship between modernity, the nation-state, and the social science.

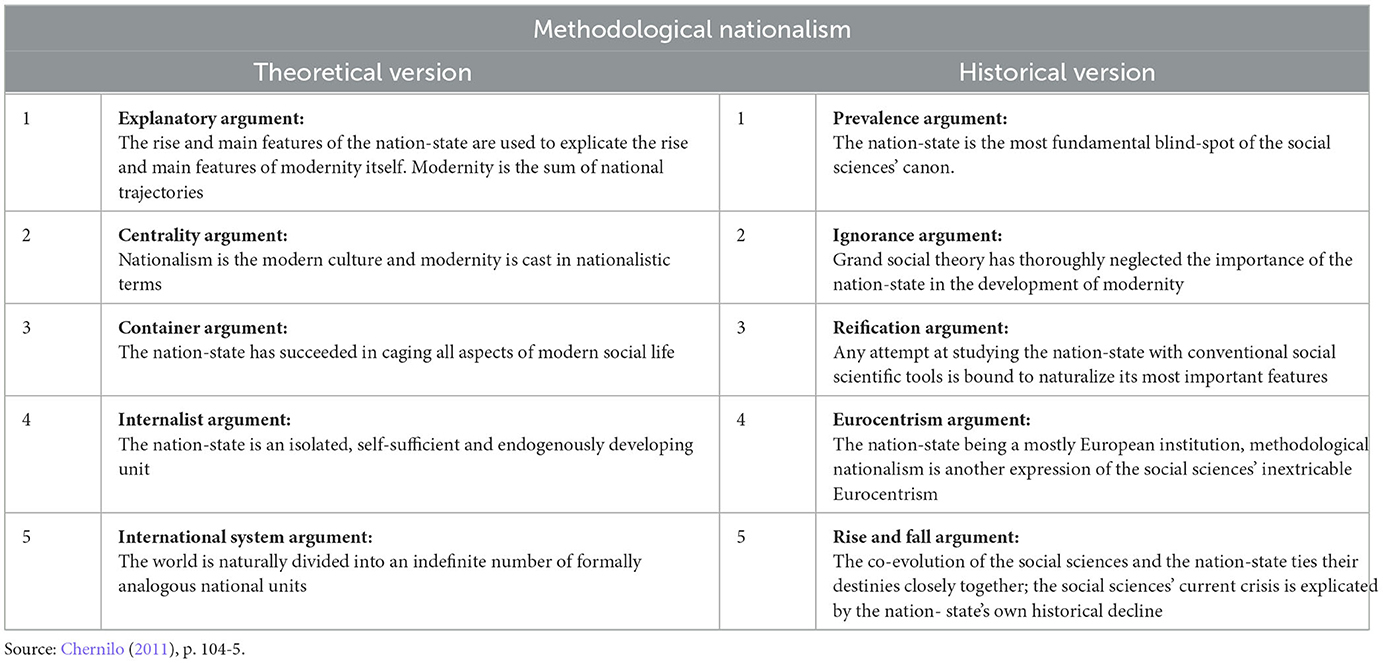

Building upon the trilateral interplay of modernity, the social sciences, and the nation-state, Chernilo (2008, 2011) has delineated two predominant facets and a spectrum of ten distinct arguments concerning methodological nationalism. In the theoretical rendition of methodological nationalism, the social sciences' categories and concepts are contextualized within the national framework, while presupposing a certain correspondence between the attributes of modernity and the regime of nation-state. The historical variant of methodological nationalism asserts that from the inception of the social sciences and the ascendancy of nation-states, the social sciences aimed to shape their foundational constructs, encompassing notions of society, state, and culture, in alignment with the core principles of the nation-state. Here, by considering modernity uniformly and ignoring the various types and paths of modernity, the historical development of modernity is also understood in relation to the process of nation-state formation. Based on these two versions of methodological nationalism, Chernilo derives ten arguments, which can be seen in Table 1.

Drawing upon prevailing critiques, the problem of methodological nationalism can be addressed across three overarching tiers. Certain critiques of methodological nationalism have emanated from ontological standpoints. Assertions at this stratum contend that social science and theory have historically and ontologically crystallized in conjunction with classical modernity—an epoch characterized by the modern and imperialist Western European milieu, wherein the unit or container of the nation-state, its confines, components, and dynamics, reigned supreme. In the present era, as this world enters into a new wave of modernity, fresh national, transnational, and global dynamics have surged to the forefront, accompanied by the waning of many erstwhile elements and entities. Social structures, relationships, and the broader fabric of reality itself have undergone a profound transformation. Novel social constructs have surfaced, obliterating numerous established boundaries, liberating hitherto excluded non-modern rationales, and orchestrating a paradigm shift on a global scale. Consequently, the recognition of these novel components and entities mandates the deconstruction and subsequent reconstruction of countless erstwhile cognitive categories and conceptual entities (Lyotard, 1986; Featherstone, 1991; Seidman, 1994; Robinson, 1998, 2001; Giddens, 1999; Bauman, 2000, 2002; Held and McGrew, 2003; Albrow, 2004; Wallerstein, 2004; Beck and Sznaider, 2006; Dicken, 2007; Held, 2010; Nash, 2010; Amelina et al., 2012; Arjomand, 2014).

Within the epistemological realm, methodological nationalism assumes the guise of a cognitive bias demanding re-visitation and critique by amending the current semantics, semiotics, and conceptual apparatuses that have been entrenched within the nation-state's prevailing regime of truth. Amidst this avenue of critique, the assertion stands that within the sphere of the social sciences, both theoretical and empirical analyses find themselves circumscribed by the boundaries of nation-states. The presumption prevails that the tapestry of social realities solely encompasses national entities and collectives characterized by a shared history and attributes. In this respect, Wimmer and Glick Schiller (2003, p. 577-578) distinguish three interconnected variants of this bias in social sciences:

“1. Ignorance or disregarding the fundamental importance of nationalism for modern social sciences; 2. naturalization of the global regime of nation-state or taking for granted that the boundaries of the nation-state delimit and define the unit of analysis; 3. territorial limitation which confines the study of social processes to the political and geographic boundaries of a particular nation-state.”

Together, these variants generate an epistemological context in which social entities are seen as universal, taken-for-granted, and positive units—analytical units that, while originating within the sphere of modern Western Europe, are deemed to be positively and objectively generalizable and applicable across all societies (Connell, 2007). Essentialism, universalism, state-centrism, groupism, territorialism, etc., are considered the causing factors as well as manifestations of the bias (Martins, 1974; Wimmer and Glick Schiller, 2002, 2003; Chernilo, 2006, 2011; Seidman, 2008; Amelina et al., 2013; Sager, 2016, 2021).

The normative dimension highlights the Eurocentric aspect and the politics of nationalism that are embedded within modern social science and theory. Here, it is attempted to reveal that the dominance of methodological nationalism in social science has led to dismissing or naturalizing various social others, otherings and antagonisms that have intentionally or unintentionally brought about the exclusion of so-called internal and external anti-national or non-national actors (Wimmer, 2002; Chatterjee, 2020). In this regard, it is claimed that one of the normative consequences of methodological nationalism is the dominance of a kind of state-centered conception of territory, space, and society (Dumitru, 2014), a situation in which “state territories delineate the boundaries of the political; society is conceived as composed of immobile, culturally homogenous citizens, each belonging to one and only one nation-state; and even in economics, the distribution of goods and services are examined according to a sharp contract between the domestic and the international” (Sager, 2016, 2018, 2021, p. 1).

While all of these critiques are accompanied by a general claim on the historical correspondence and entanglement between early modernity and the social sciences, they have offered various solutions to overcome the problem of methodological nationalism. In dealing with this problem, by deferring the notions of society and the social, some critiques have called for the abandonment of sociology as a modern, national, and universal science, in favor of a kind of liquid, relational, contingent, and more global knowledge (Lyotard, 1986; Bauman, 2002); referring to premodern components and units, such as ethnie (Smith, 1986) or other units of analysis like empire (Steinmetz, 2014, 2016) and civilization (Arjomand and Tiryakian, 2004), has been urged by some sociologists; some have sought to historicize the objects, categories of analysis, and the relationships between social researchers and their objects of study (Marjanen, 2009); some theorists have suggested notions such as “global sociology” (Albrow, 1996), “world society” (Meyer et al., 1997; Meyer, 2018), “world system” (Wallerstein, 2004), “global field” (Go, 2008) to tackle this problem; some have considered “methodological cosmopolitanism” as an alternative to methodological nationalism, thus introducing the idea of “cosmopolitan sociology” (Beck, 2006, 2016a,b; Beck and Sznaider, 2006) and urged for constant criticism in support of cosmopolitan social science (Sager, 2018); by displaying the ambiguous encounter of social theory with the nation-state and also the ambivalent position of the nation-state in modernity at three levels, namely historical, sociological, and normative, some critical efforts have sought to release social theory from the clause of methodological nationalism by revisiting the relationship between the nation-state and modernity (Chernilo, 2008, 2011), or by addressing different manifestations of methodological nationalism such as state-centrism (the supremacy of the modern state over society), territorialism (understanding space as divided into bounded territories and in an absolutist conception), and groupism (assuming society as a collection of national groups) (Dumitru, 2014); some scholars have suggested a kind of spatial turn (Adamson, 2016), the priority of the relativist concept of space (Pries, 2007), a cross-border concentration (Amelina et al., 2012), a multi-sited ethnography (Marcus, 1995), and an emphasis on the transnational field (Go and Krause, 2016), or transnational space (Crang et al., 2004). In this respect, transnational studies and some parts of migration studies have principally tied the life of their own field to the critique and overcome of the problem of methodological nationalism. They ponder that understanding transnational phenomena and actors primarily depends on suspending the bias of methodological nationalism and finding alternative approaches and methods (Amelina et al., 2012, 2013; Faist, 2012; Amelina and Barglowski, 2018).

In this regard and in a different approach, Mandelbaum (2020) contends that the ideal of state/nation congruency in modernity is conceivable based on a kind of genealogy, i.e., focusing on the conditions that made this convergence possible. According to his reading, understanding this congruency is the key to grasping methodological nationalism, and in this respect, its precise understanding is possible only by deploying discourse analysis and Lacanian psychoanalytical approach, analyses that reveal how the dominance of the technologies of homogenization in modernity has set the ground for the congruency. Drawing on a Lacanian psychoanalytical approach, finally, Mandelbaum concludes that, these congruency and homogenization, are essentially a kind of fantasy, that is, “an endless effort of overcoming the lack and contingency of social life by offering a ‘fullnessto-come” (Mandelbaum, 2020, p. 3). This fantasy, as Mandelbaum puts it, “masks the disunity of, and the split in, society by offering an explanation for why “we” (the “nation,” “people,” “society” and other tropes referring to an imagined collectivity) are not yet congruent and by promising resolution and thus unity “... once a named or implied obstacle is overcome” (Mandelbaum, 2020, p. 4). Congruency must be endlessly re-imagined and re-invented, a certain utopia that is never determined and thus constantly invoked, because such a state of completeness or wholeness, a fixed and solid identity, is never achievable. This re-imagining or re-invention has become the basis for the formation of a regime of methodological nationalism. But what we have access to are the moments of actualization of the congruency of the state/nations in different forms, the moments in which methodological nationalism crystallizes itself. An outcome of this type of deconstruction of methodological nationalism is its indetermination.

In general, in many of these revisionist approaches, dealing with modernity and its political, economic, and cultural representations has been the primary step in rethinking the social sciences. These approaches can be divided into two categories: one is the reformist approaches that seek to decentralize modernity in general and the nation-state in particular in the social sciences, and the other is the revolutionary approaches that, by deconstructing modernity as well as the entity of the nation-state, seek to suspend their dominance in the social sciences (Chakrabarty, 2000). According to Saïd Amir Arjomand, this decentralization of modernity in the social sciences has taken place in two ways: “firstly, by historicizing social evolution and developmental patterns in different civilizations as well as varying regional paths of modernization, and secondly, by introducing varieties of modernity lite in the overlapping forms of multiple, colonial, subaltern, and peripheral modernities” (Arjomand, 2014, p. 16). By historicizing and restructuring dominant notions and categories in the social sciences, in this direction, endeavors are being made to rethink and modify them in proportion to the globalized and pluralistic contemporary world (Wittrock, 2014). This pervasive approach still retains the ontological, epistemological, normative, and historical foundations of the modern social sciences and pursues only minor modifications and promotions in social science and theory. And in Michel Foucault's words, these amendments are still being made within the modern episteme. Almost all of the critiques and alternatives outlined above fall into this category because their main attempt is to modify the social sciences or to introduce alternatives (with the same cognitive coordinates) to the categories and theories of the social sciences. These efforts can be a noble starting point for criticizing the dominant notions and categories of the social sciences, but given the global ontological developments as well as the epistemological and normative implications of the sciences, they are by no means the final step.

This coincidence of the emergence of nation-states and the discourse of nationalism, and modernity, is not a historical incident, rather, this synchronicity will be understood precisely in terms of the evolution of the regime of power as well as the cognitive context in which categories such as society, people, state, citizen, nation, etc. emerged. It can be argued that these categories and discourses owe their very existence primarily to a regime of differentiation imprinted within “the modern episteme.” Therefore, merely retrieving and correcting these categories or criticizing, controlling, and eliminating the national dimensions of these categories cannot help much to overcome the problem of methodological nationalism. The initial stride toward addressing this issue necessitates historicizing the intricate interplay between social science, modernity, and the formation of nation-states. This historicizing can be traced in two strands: one is to scrutinize this entanglement in relation to the social and historical developments of modern Europe in the age of state-nation-building, and the other is to place this relationship and examine its conditions of possibility within the context of the modern episteme. The second branch, which is a kind of deconstruction of modern social sciences as well as the discourse of nationalism, reveals how the domination of modern man, as well as the precedence of a kind of differentiating regime in the modern episteme, has crystallized in many conceptual and discourse constructs, a supremacy that can be perceived in modern social sciences, its central categories, and especially nationalist discourses. Then, through this historicization, it can be demonstrated that, by exercising techniques of control as well as domination of a regime of foundationalist differentiation, nationalism is just a discourse in modernity that has been able to be hegemon in a certain period. On the other hand, by referring to the epistemological contexts of the emergence of social science in classical and then modern episteme, it can be argued that many central categories and divisions of this science, such as society or the social, and later their integration into the discourse of nationalism, were fundamentally premised on the obligations and necessities of the modern episteme. In this way, it is possible to provide a ground for deconstructing the foundations of these categories and discourses.

Social science, as an historiographical discipline that emerged within the realm of classical modernity, stands at a juncture that necessitates a comprehensive deconstruction of modernity itself to adapt to the novel global circumstances—an undertaking that demands dismantling several prevalent conceptions and frameworks within social science. Consequently, the advent of the new globalized and transnational world order compels the pursuit of the second way, which involves the rupture and deconstruction of modernity's very foundations. This deconstruction must take place at the deepest cognitive basement of the modern world, i.e., the modern episteme, and one of its most important representations, i.e., the dominance of methodological nationalism. Existing criticisms of methodological nationalism at the high level have been critiques of one of the premier manifestations of the modern episteme without digging deeper into the basic driving forces of this bias. Basically, the kind of intention—namely nationalistic inclination—toward the globe, and deploying some distinctions and categories for making sense the world, have all developed through specific historical process and in a particular context in the period of nation-states-building in the modern world. This period has exactly coincided with the dominance of the modern episteme in Western Europe. The primary objective of this research is to demonstrate that this coincidence was not accidental. Principally, the construction of categories such as nation, society, state, individual, order, freedom, etc., with special implications, have undergone historical transformations rooted in both social and epistemological dynamics. These categories, characterized by their considerable malleability, have, in the contemporary era, encountered a decline in their capacity to provide comprehensive explanations and have consequently transitioned into what can be termed as “zombie categories” (see Beck, 2002; Beck and Williams, 2004).

The deferral of the correspondence between the idea of society and the formation of the nation-state in modernity compels, primarily, the suspension of the category of society as the central object of the social sciences and, simultaneously, the suspension of the premise that considers the nation-state the dominant entity in modernity. From a historical point of view, it becomes evident that these two categories are fundamentally interwoven within the tapestry of the modern episteme; concomitantly, nationalism surfaced as a discourse within this episteme that eventually ascended to the position of hegemonic discourse. This intricate entanglement across three strata—ontology, epistemology, and normativity—has precipitated the exclusion and rejection of a plethora of phenomena, actors, forces, ideas, and more, that have surfaced in the new global landscape. Thus, the deconstruction of both society and nationalism assumes significant potential in liberating the social sciences from the clutches of Eurocentrism and methodological nationalism.

3. Modern episteme and the rise of human science

Foucault (1966, 1971, 2002) in his first works, puts forward the idea of episteme to explain the deep structure on which discourses and discursive practices, as well as sciences or scientific discourses and any forms of knowledge in general, are formed and transformed. For him, the analysis of discourse formations in relation to epistemic constructs, in order to distinguish them from other possible forms in the history of knowledge, is the analysis of the episteme. Episteme is a general and principled system of understanding in a period of history that “imposes on each branch of knowledge the same norms and postulates, a general stage of reason, a certain structure of thought that the men of a particular period cannot escape” (Foucault, 2002, p. 211). Episteme refers to the historical a priori of an epoch (Oksala, 2005, p. 22) which grounds truth, knowledge, sciences, and discourses and provides the condition of their possibility (Peters, 2021). Each episteme possesses a set of regulations and principles ordered in systems; and based on the order in which these rules and principles are placed together in that system, the conditions of possibility of discourses as well as sciences are determined; their internal, conceptual, and fundamental relations are identified; the instruments and possibilities of consolidation as well as the dominance of discourses are provided; truth and falsehood, central and important as well as secondary and unimportant categories, insiders and outsiders, so on, are constructed and justified. Epistemes are cognitive contexts for understanding the order of the universe or the order of things. By episteme, Foucault means,

“the total set of relations that unite, at a given period, the discursive practices that give rise to epistemological figures, sciences, and possibly formalized systems; the way in which, in each of these discursive formations, the transitions to epistemologization, scientificity, and formalization are situated and operate; the distribution of these thresholds, which may coincide, be subordinated to one another, or be separated by shifts in time; the lateral relations that may exist between epistemological figures or sciences in so far as they belong to neighboring, but distinct, discursive practices. The episteme is not a form of knowledge (connaissance) or type of rationality which, crossing the boundaries of the most varied sciences, manifests the sovereign unity of a subject, a spirit, or a period; it is the totality of relations that can be discovered, for a given period, between the sciences when one analyses them at the level of discursive regularities (Foucault, 2002, p. 211).”

In any given culture and at any particular moment, there is always only one episteme that defines the conditions of possibility of all knowledge and discourses, whether expressed in a theory or silently invested in a practice (Foucault, 1966, p. 183). In the order of things (Foucault, 1966), Foucault identifies three epistemes in Western culture. In each of these three epistemes, which have dominated the Western world in three different periods, there is a specific and distinct form of the structure, arrangement, and pattern of knowledge. For Foucault, each episteme is configured around 19th key fundamental cores, logics, and notions. The first episteme, manifesting in the pre-classical era (the Renaissance), extended from the medieval period to the early seventeenth century, and was characterized by the principle of analogy and resemblance. In this period, human science hadn't yet fully emerged, so there is no difference between humans and non-humans. Based on the episteme, The study of the world was facilitated by the analogy between things and by the recognition of their resemblance to other entities and things.

The classic episteme constitutes the second prevailing episteme, coming into prominence from the mid-seventeenth century and extending through the early decades of the nineteenth century. In this period, which coincides with the emergence of scientific knowledge, the main focus was on the regulated and organic nature of things as well as their evolution, and on the other side, the external world could be imagined in the mind, just as light is reflected in a mirror. Rather than resembling one another, things here represent each other. Man, as a mind, possessed certain abilities to know the regime of representations, and by employing a variety of classification and categorization apparatuses, he tried to grasp the assumed order. The third type of episteme, i.e., the modern episteme, emerged in the modern epoch, that is, from the nineteenth century onwards, seeking to discover a rational and universal order that was supposed to be embedded behind the regulated facts and events of the universe, facts and events for which history was considered. A kind of essence, as well as the origin and thus history, are imagined for these phenomena, essences, and histories that can be comprehended by the subject. Order was grasped in this episteme, however, primarily on the basis of differentiation rather than resemblance or cognition of representations. Differentiation, as well as presupposing essence and history, were the central principles of this episteme, which took place based on a kind of foundationalism (Foucault, 1966). Firstly, the objects of knowledge in this episteme were regulated, homogeneous, positivist, and independent units. Secondly, a solid grounds, as well as an origin for these objects, was considered a priori, and the rational knowledge of these objects also depends on the knowledge of this foundation and its evolution. Third, and accordingly, the consideration of determinate and regulated objects, as well as the ultimate ground for them, implies the exclusion of many other events and phenomena.

It was precisely at the moment of Western culture's transition from representation to differentiation that (modern) man, as the prominent ground, was created. Here, man became a subject who made himself the object of his knowledge; one who must be conceived of and that which is to be known. According to Foucault (1966), this is where modern human science is born. In the modern episteme, the thinking man, or subject, no longer merely sought to know the a priori mathematical order or a posteriori empirical knowledge of life, economics, and language as given and positive objects. These were regulated objects that came into being and became meaningful in relation to man, and were transformed according to his will. These objects were, above all, constructive objects formed through the processes of identity and difference and, based on their presupposed foundations, objects for which history was also considered. This man's way of being in the modern episteme, as Foucault mentioned, led him to be “the foundation of all positivities and present, in a way that cannot even be termed privileged, in the element of empirical things” (Foucault, 1966, p. 375). Since the 18th century, the status has functioned as an almost self-evident foundation for modern thinking and “human sciences,” as the body of knowledge, or in other words, the body of discourse, that takes man as its main object. Unlike the classic episteme, where the main aim was grasping the given order of things through seizing its system of representations, here the universe or order of things is recognized through the mediation of human science, with the aim of identifying and mastering its various aspects based on human will.

By identifying the epistemological realms, the dominant sciences, and their relationships, as well as their transformation in the modern episteme, Foucault strives to depict the conditions of the possibility of human science. Through this examination, the regime of differentiation and ultimately the fundamental dualities that govern modern human science are presented—the regime and the dualities that are appreciated in every human and social analysis and even their critiques. In the order of things (Foucault, 1966), everything is explained in the form of a triad. The three fundamental sciences in modern episteme are the mathematical and physical sciences—“for which order is always a deductive and linear linking together of evident or verified propositions” (Foucault, 1966, p. 378), economics—“that proceed by relating discontinuous but analogous elements in such a way that they are then able to establish causal relations and structural constants between them,” and philosophy—“which develops as a thought of the same.” The modern human science as well as the discourses articulated in the modern world, while encompassing some aspects and categories of these sciences, go beyond them; and at another level, due to the centrality of man, they revisit and reconstruct these sciences. Foucault considers these three epistemological regions as the domains of the human sciences in the modern episteme. The various branches of the human and social sciences are formed and evolved in the middle of these three epistemological regions based on their constituent models. For Foucault (1966, p. 389), these constituent models are primarily borrowed from the three subsequent domains of biology, economics, and the study of language. By offering a definition of man, each of these three epistemological regions presents a logic of human behavior, a logic that can be interpreted in relation to some dualities. Given the centrality of man, then these realms themselves become the source of the emergence of other branches of social science such as psychology, sociology, linguistics, and mythology. As a result, we can discern a correlation between three levels of knowledge that might have been acquired through various sciences.

In biology, man is portrayed as a being that fulfills functions. He receives stimuli, including psychological, social, or cultural stimuli, and then responds to them, adapting, changing, evolving, or succumbing to the demands of the external environment. In dealing with imbalances, this person tries to eliminate them, and on another level, while generating regularities, he tries to adjust his behavior in relation to them. This is the process that somehow determines the “conditions of existence and the possibility of finding average norms of adjustment that permit him to perform his functions” (Foucault, 1966, p. 389). Here, the duality of function and norm is the duality on which human behavior is attempted to be explained. Man, who inherently possesses needs and desires, is the object of economics. In satisfying the needs, the man enters into conflict with other men with the same interests and expected profits. Therefore, man “appears in an irreducible situation of conflict; he evades these conflicts, he escapes from them, or he succeeds in dominating them, in finding a solution that will—on one level at least, and for a time—appease their contradictions; he establishes a body of rules that are both a limitation of the conflict and a result of it.” Here the duality of conflict and rule prevails. In the region of language, man's behavior looks like an endeavor to say something, whose every action and practice has meaning; “everything he arranges around him by way of objects, rites, customs, discourse, and all the traces he leaves behind him, constitutes a coherent whole and a system of signs” (Foucault, 1966, p. 390). The duality of signification and system is the duality that dominates in the realm of language and meaning. Reaching these dualities in human science is Foucault's main goal in the archaeology of (human) knowledge.

As mentioned earlier, what dominates all of these sciences, epistemological domains, and dualities is a kind of regime of foundationalist differentiation, a regime that produces closure units as objects of analysis in the human and social sciences, essentially in terms of the evolutionary process of identity and difference, on the basis of solid foundations. The embedment of these dualities, which is characteristic of Western metaphysical thought, is itself a manifestation of this regime. Foucault (1966) places these dualities at the two ultimate poles: the pole that refers to the first dimension of these dualities, namely function, conflict, and signification, an indeterminate and uncompleted state in which man is imagined in a somehow process of becoming; the opposite pole, which is focused on the second dimension of dualities, namely norm, rule, and system, highlights the determine and regulated condition in which numerous structured constructions and closed entities can be comprehended and identified. The first domain is the realm of events, process, and relative contingency, the second region is the realm of facts, regulation, and order. Different discourses about modern human science and even its critiques can be traced in different places between these two general poles. Even within these two poles, the regime of differentiation—with a kind of foundationalism—operates. In different discourses as well as sciences on humans, some functions, conflicts, and antagonisms, and significations are considered and highlighted, and others are left out. Any kind of definition of norm, rule, and system, or in other words, regulated and fixed categories—which comprises assuming foundations for them, requires the exclusion of various possibilities and relations that are either defined in opposition to regulation or, while having a level of regularity, entertain distinct specialties in respect to the mainstream as well as universal conceptions of norm, rule, and system. Units such as people, society, culture, and nation-state are categories that are considered in the second pole from a kind of static and regulated point of view. As the central notion and entity in the social sciences, for example, society is mainly depicted and understood in the second pole. Every imagination of society involves an image of non-society (Foucault, 2003). Here, too, society, according to the conditions of its emergence in early modernity, is regarded as a regulated and established entity, and the social is conceived as something that already exists and is predetermined (Latour, 2005).

In the words of Laclau (1999, p. 146), the notion of society points out “the possibility of closure of all social meaning around a matrix which can explain all its partial processes”. The closure comprises the exclusion of many other possibilities and options. On the other side, this entity itself is grounded upon “founding totality” (Laclau, 1991, p. 22), on the basis of which society is assumed to be a cohesive and regulated whole, an entity whose order can be identified and controlled. Therefore, any definition of the social entails some kind of fundamental differentiation. The genealogy of the social indicates that it has found its existence principally in contrast to the others, such as the individual, the economic, the religious, the political, the abnormal, the contingent, and so on. In favor of the determine, and on the horizon of the second pole, society and the social are beings that seek to set aside the indeterminate and events. In the meantime, considering the social as a contingent unity, which itself exists under certain conditions of possibility, as well as the issue of the origin, is neglected. Criticisms of these categories, criticisms of notions such as society, nation, citizen, institution, etc., by displaying their contingency as well as prioritizing the conditions of their possibility, are endeavors to radicalize the first pole of this general duality. While proving the impossibility of an entity such as society, here the social is assumed to be on the horizon of antagonism and the indeterminate order of things, the state in which we are faced only with moments of actualization of society. Henceforth, the whole order of reality cannot be reduced to the temporary moments of stability of the social, the moments that try to suspend the functional nature, the conflict, and the fluid system of signification in favor of the norm, rule, and system. This regime of foundationalist differentiation as well as the mode of analyzing the order of things are deeply embedded within social theory and its central categories that have emerged in the modern world and are represented through a variety of biases, including essentialism, groupism, anti-historicism, territorialism, various centrisms, foundationalism, etc. The bias of methodological nationalism, which is depicted as a kind of correspondence of nation, state, and society, or nationalism, modernity, and modern human science, can be understood effectively, convincingly and sufficiently in this line of discussion. Both modern human and social science and the discourse of nationalism have arisen from the modern episteme, dominated by these cognitive and epistemological relations and constructs, in which identity and difference, or various regimes of differentiation, have been the central elements to constructing and recognizing existing facts.

4. The discourse of nationalism and the regime of differentiation

In addition to the human sciences, the modern episteme also provided the conditions of possibility for various discourses and was able to imprint some of its fundamental marks throughout them. Discourses are “the systems of thoughts composed of ideas, attitudes, courses of action, beliefs, and practices that systematically construct the subjects and the worlds of which they speak” (Lessa, 2005, p. 285). The discourse of nationalism, alongside its corresponding discursive practices, which evolved in tandem with the rise and consolidation of modern human sciences, carried cognitive coordinates that closely mirrored those of science. The appearance and supremacy of the discourse of nationalism, as well as its associated regime of power and truth, established a cognitive ground under which every social phenomenon or event, as well as other discourses such as religious, cultural, economic, and political discourses, are compelled to determine their existence and implication in relation to the discourse's coordinates. At this level, one might talk about the intersection of the discourses of nationalism and the human sciences as scientific discourses. The regime of foundationalist differentiation that prevailed throughout the modern episteme manifested itself explicitly throughout the process of articulating the discourse of nationalism.

The ascendancy of this discourse's categories and the system of signification over the human sciences also led to the fact that determined and regulated entities and categories, such as society and the social, are considered to be identical with the nation and the national respectively, categories that themselves were cognitively constructed on the basis of the modern episteme and had the same constitutive characteristics. Hence, the knowledge of societies was considered essentially equivalent to the knowledge of nation-states. The totalitarian regime of differentiation ruling the nationalist discourses, as well as assuming and highlighting well-closed and determined national entities, caused all kinds of heterogeneous events, configurations, and phenomena to be (re)defined and excluded as non-national, both conceptually and empirically. Based on the famous definition of Gellner (1983, p. 1), “nationalism is primarily a political principle, which holds that the political and the national unit should be congruent.” Above all, this congruency is established and preserved through various regimes of boundary-making and homogenization, in such a way that “nationalist sentiments are deeply offended by violations of the nationalist principle of congruence of state and nation” (Gellner, 1983, p. 1). “This notion of congruency—a congruency of “people” with space and authority, or, briefly, the discursive idea by which nation and state ought to be aligned—, as Mandelbaum argues, “has become a leitmotif in our contemporary modes of thought” (Mandelbaum, 2020, p. 1).

In general, if we consider nationalism, in the words of Michel Foucault (2003), a kind of discursive framework and formation that comprises a way of speaking and carries a kind of consciousness, this discourse is articulated in the modern era and based on its cultural, economic, and political requirements; and, like many modern discourses, it has ideas about society, people, and language. The type of articulation of these discourses, the central themes, nodal points, and categories around which they are articulated, and the relationship between the different discourses in the modern world are, above all, determined by the cognitive context that, a priori, determined and made possible many of their features but at the same time has limited their articulation framework. Principally, nationalist discourses are distinguished from one another as well as non-nationalist discourses by a particular “concrete content” (Finlayson, 1998). Nationalist discourse is the narrative of an order of reality as well as a group of people who have possessed distinctive specificities, and simultaneously, it tries to make these particular features universal and natural. More than anything else, it was a narrative “that encodes and produces the transformation of people from a loose group of subjects under a sovereign monarch into an association of citizens forming a nation” (Finlayson, 1998, p. 101-2). Here individuals were redefined under a new discourse of men as citizens, and a new relationship was imagined between these citizens and, national communities, entities, and categories.

Through articulating, producing, and then dominating the idea of the nation, a conception of this group of individuals, as well as an order of things, attained stability and legitimacy. By depicting various orders of reality in a variety of nationalist discourses, different types of traits and groupings are attributed to this group of people, who have been called the nation. Craig Calhoun, for example, lists ten of the “concrete content(s)” referenced in nationalist discourses. These ten items are: ‘Boundaries, of territory, population, or both; indivisibility—the notion that the nation is an integral unit; sovereignty, or at least the aspiration to sovereignty, and thus formal equality with other nations; an “ascending” notion of legitimacy; popular participation in collective affairs; direct membership, in which each individual is understood to be immediately a part of the nation; culture, including some combination of language, shared beliefs and values, habitual practices; temporal depth—a notion of the nation as such existing through time, including past and future generations, and having a history; common descent or racial characteristics; special historical or even sacred relations to a certain territory” (Calhoun's, 1997, p. 4-5). While projecting a general picture of the social world and its order, nationalist discourses in the modern world strive to differentiate a certain group of people and give them a distinctive position, as well as reconstruct the social world based on the narrative about them. As previously argued, nationalist discourse is a constructed discourse in the modern episteme, and on the other hand, based on the characteristics of this cognitive context, the discourse itself is constructive, that is, it attempts to impose new order, subjectivity, and a system of signification on the social world by discarding or reorganizing existing forces, actors, antagonisms, and arrangements. The three dimensions of nationalism, namely nationalism as a discourse, a project, and an evaluation proposed in Calhoun's (1997, p. 9) definition may be precisely understood resting on the premise, aspects that are repeated in different articulations in various definitions of nationalism.

The regime of differentiation in the modern episteme can be clearly traced to the processes of articulation, consolidation, and hegemony of all kinds of discourses, especially nationalist discourses. This regime of foundationalist differentiation also allows us to precisely understand the regimes of congruency and homogenization that Mandelbaum (2020) seeks to interrogate. In his speech, order of discourse, Foucault (1971) describes in detail this regime of differentiation and the techniques of control that govern discourses. In the case of nationalist discourses, this regime and techniques play a pivotal role in preserving, expanding, and dominating the nationalist concrete content and its discursive order, a discourse that seeks to mark as well as distinguish specific groups, procedures, forces, categories, trends, and relationships. When it comes to the modern episteme, this discourse, while embracing many of the requirements of this episteme, has provided a platform for reconstructing other discourses and different forms of knowledge in the contemporary world. These techniques and the regime of differentiation, which has been instituted in the global regime of nation-states, are supposed to protect the discourse from events or the contingent that somehow threaten their existence or order. According to Foucault (1971, p. 8), “in every society the production of discourse is at once controlled, selected, organized and redistributed according to a certain number of procedures, whose role is to avert its powers and its dangers, to cope with chance events, to evade its ponderous, awesome materiality.”

As Foucault (1971, p. 8-9) points out, the regime of differentiation and control of discourses works on three levels: the external restrictions and controls imposed on discourse; the internal procedures of control and differentiation; and the restrictions that govern the production, distribution, and consumption of discourses . The external exclusionary procedures imposed on discourses include prohibitions, the topics that are taboo to talk about; divisions and rejections within discourses, divisions such as reason and madness, and rejection of madness; assuming the existence of a truth-oriented system, the will to truth, and the fundamental opposition between truth and falsity (Foucault, 1971, p. 10-12). Internal procedures of differentiation and maintenance of discourse's coherence operate at three levels: by introducing basic texts, categories, and principles, at the first level, discourses aspire to bind commentaries in some way in relation to them, to the extent that they are not considered creations. The second level is related to the special and unifying position of the author(s), with different levels of authority. By establishing a system of relations, the third level, namely the disciplinary, attempts to set a kind of stable regulation, and while putting the discourses as part of that system, it also considers a kind of regularity and stability for them (Foucault, 1971, p. 13-17). The third layer of this regime of differentiation is the a priori conditions that control the accessibility, production, and distribution of these discourses (Foucault, 1971, p. 17-18). Foucault identifies these conditions of appearance, growth, and variation at four levels: 1. The qualification of the speaking subject to enter the order of discourse. This qualification, as well as the signs that must complement the discourse, are outlined by rituals; 2. Societies of discourse that retain and disseminate discourses inside a restricted space; 3. doctrines (orthodoxy and heterodoxy) that belong to a group of people and, while distinguishing between groups, tend to bind them into entities; 4. appropriation, or more precisely, the social appropriation of discourse. Here, the dominant values and goals in discourse are internalized as the ends of discursive practices. Educational systems are the best example of this layer of this regime (Foucault, 1971, p. 19-21).

These three layers and ten levels can be well-tracked in the case of nationalist discourse, the dominant discourse that became hegemon in the late 19th century, and, based on its concrete content, somehow revisited the relationship between discourses as well as the order of knowledge. But when it comes to the modern episteme, according to Foucault (1971), the discourse's regime of differentiation operates on a cognitive basis, which prevents this discourse from being considered an objective reality or from becoming problematic in modern thought. In the episteme, the procedure operates through the precedence of a founding subject; emphasizing the originating experience, an experience that implies the presence of a chain of significations; or referring to universal concepts and categories—by presupposing the notions of essence and origin–in the process of understanding the order of realities, a process in which singularities are elevated into concepts. What happens throughout this procedure is the reduction of the whole discourse to its part of the signifier. On the other side, the discourse's regime of differentiation works with dualities that are deeply rooted in the modern episteme. In this episteme, the event is placed against creation, series opposed to unity, regularity vs. originality, and the condition of possibility in contrast to signification. Like in the previous section, these dualities are located in the two ultimate poles, and the second pole, namely creation, unity, originality, and signification, is considered the dominant one. Because of this regime, the determine, that is, the national, as well as the regular and universal entity, which are the nation and the nation-state, must be protected from the thread of the indeterminate, irregular, and singular. In other words, the process of nation-state formation and the dominance of nationalist discourse are fundamentally the re-establishment of the order of social reality on the basis of a discourse distinguished from others by the concrete contents. In terms of the characteristics of the modern episteme, with the dominance of any discourse, we are confronted with a type of methodological and agency centrism (Tabak, 2020), such as methodological statism, methodological cosmopolitanism, methodological ethno-symbolism, methodological transnationalism, and so on, biases with similar consequences to the problem of methodological nationalism in the humanities and social sciences. Since the existing critiques of methodological nationalism continue to address this bias in the coordinates of the modern episteme, they cannot offer an effective solution to overcome it and somehow fall into the trap of another centralism. Despite groundbreaking critiques of nationalist discourses, a deep and precise understanding and critique of nationalism, as well as methodological nationalism, rely heavily on an understanding and critique of modern episteme, its fundamental features, and its regime of foundationalist differentiation.

5. The politics of transnationalism

As discussed so far, identifying the coordinates of the modern episteme as well as the relationship between human and social sciences, and the discourse of nationalism is the first step in truly understanding the problem of methodological nationalism. Attempts were made in this paper to demonstrate in detail how this episteme operates on cognitive grounds that can be traced back to many of the intellectual and cultural constructs of late modernity. This very ground facilitated the historical and epistemological prerequisites for the correspondence or congruency of social science and the discourse of nationalism. The suspension of many of these features and functions can provide new horizons for overcoming the problem of methodological nationalism and making sense of a wide range of social phenomena on a global scale.

The central proposition of this paper asserts that any critique of methodological nationalism necessitates the provisional suspension of the overarching coordinates of the modern episteme. Thus, any critique of methodological nationalism must inherently begin its journey from an epistemic standpoint. Foucault himself presented general and philosophical critiques for transcending the modern episteme, which can potentially contribute to certain theoretical-philosophical aspects but remain inadequate from a precise methodological standpoint. Confronting this limitation, the present paper introduces the philosophy of post-foundationalism as a philosophical approach to navigate beyond the modern episteme and, consequently, methodological nationalism. The dominance of this approach, beyond its philosophical implications, carries significant consequences for the methodology of social and political inquiries, particularly concerning the units of analysis, reference, and measurement.

Foucault (1971, 2003) proposed that the initial stride along this trajectory involves the suspension or inversion of numerous dualities and fundamental tenets within the modern episteme, which establish and govern the regime of differentiation. However, his suggestions for transcending these dichotomies are quite broad and serve more as guiding principles, both in the analysis of the modern episteme and the analysis of discourses. For instance, he identifies the initial step as questioning the prevailing will to truth that has held sway over Western culture since ancient Greece until the contemporary era—a pursuit that has undergone diverse variations, otherings, and dualities. He also advocates for the pivotal reexamination of the human-centrism or humanism in modernity. The prominence of man and his position as a rational subject of the universe (thus establishing the subject-object relationship) should be temporarily set aside in favor of embracing multiple ontological states. Furthermore, Foucault suggests that accentuating the fluidity and conditionality of these dualities can potentially alleviate certain predicaments within the modern episteme and discourses.