Abstract

We introduce a new framework of the functions of direct democracy within a democratic political system. These are: (1) channeling political input into the decision-making arenas by circumventing organized interests (input function), (2) channeling political issues out of the representative decision-making system (exit function), and (3) producing decisions about political questions (decision function). Based on the analysis of 277 instruments of direct democracy on the national level in 103 countries around the world, we find that the input and exit functions are rather unbalanced in their dynamics. The exit function shows a tendency to strengthen the concentration of power, whereas the input function rarely allows for access to both decision-making arenas. However, once issues reach the referendum, the impact is often strong, and only a small minority of states conduct referendums without any formal consequences. Beyond these results, the presented approach allows to start long-time observations of the state of direct democracy in democratic systems.

1 Introduction

In the classic understanding of democratic political systems, intermediary actors like political parties select and transport political issues into the institutions of democratic decision-making (Easton, 1965). In the last decades, the representative nature of most democracies has lost its exclusiveness, and instruments of deliberative and direct participation have been established all over the world. Instruments of deliberative and direct democracy offer alternative ways of input and decision-making functions. For the year 2020, Altman and Sánchez (2020) counted 30 national votes, two-thirds of which took place in free countries, and a quarter in partly free countries (p. 31). For Vatter (2009), direct democracy has become the third dimension of democracy.

Within this broader picture of the transformation of contemporary democracy to a hybrid of representative (still dominant), direct, and deliberative elements, we further elaborate what we consider to be the main functions of direct democracy in democratic political systems: (1) channeling political input into the decision-making arenas by circumventing organized interests and their selection logics (input function), (2) channeling political issues out of the representative decision-making system (exit function), and (3) producing decisions about political questions (decision function). These functions are solely based on the formal regulations of the instruments of direct democracy, like the requirements for launching, the competencies for authorship, or the conditions for the validity of a vote. There are already several studies investigating the role of the various designs of direct democracy. For example, research focuses on the impact of the types of direct democracy on the satisfaction with the functioning of democracy (Frey and Stutzer, 2000; Stutzer and Frey, 2003; Leemann and Stadelmann-Steffen, 2022), or the role of the level of signature requirements on participation (Schaub and Frick, 2022). The present work goes beyond the existing concepts of measuring direct democracy as we look at the functions within the political system in general. However, in contrast to the work of Vatter (2000, 2009), we make no systematic connection to specific types of democratic systems at this point.

We present an approach that allows for comparisons between countries, regions, and cities or any group of entities (such as the EU countries) and establishes a measure for the future to observe the development of direct democracy in the world. With annual reports of the system functions of direct democracy, we will be able to portray the change of contemporary democracy toward more or less direct democracy, identify strongholds of direct democracy in the world, and observe how democratization or backsliding affect the rules and functions of direct democracy. However, as our concept refers to the formal regulations of direct democracy, we make no predictions about actual votes. This is analogous to the parliamentary arena, where the electoral law is crucial for understanding elections, even without knowing single parties. In such an institutionalist view, the rules of the game determine the game and what we seek to present is a full account of the functions of direct democracy in democratic political systems.

We start by elaborating and explaining the three functions of direct democracy based on the literature about the formal organization of direct democracy. For the input and exit functions, as they are similar in their logic, we measure the availability and issue permeability. The decision-making function of direct democracy relies on the requirements for participation and approval. What is special about this concept is that the focus is not on the instruments and the functions are not rigidly aligned with the instruments, but that the functions are in the foreground. An instrument can be part of one function, but not of another. The separation of the functions is, of course, analytical, because in reality, single instruments are part of one direct democratic process. We show how five different designs of instruments of direct democracy allow for diverting political issues out of the parliamentary decision-making system in the exit function (veto initiative, authority referendum, two versions of the veto referendum, and mandatory referendum), and two different designs allow for inserting political input in the parliamentary system (agenda initiative) and the referendum (citizen initiative). The agenda initiative is not part of the decision-making function.

In the second part, we present our methods. Each function combines different variables, which are mainly already used in the literature. The concept is applied to 277 instruments of direct democracy on the national level in 103 countries around the world. The criterion for including countries is that they are classified as free or partly free by Freedom House. We take our data concerning the single instruments from the Direct Democracy Navigator project.1 The Navigator is one of the largest data sets about direct democracy, and it was thoroughly revised in 2022.2 Based on the Direct Democracy Navigator, we are able to specify the system functions of direct democracy. In the fourth section, we present our results, separately for the three functions and then in a general comparison. How strong are the different functions of direct democracy in reality? What dynamics arise from the formal architecture of direct democracy for its functioning?

2 The three functions of direct democracy in modern democracy

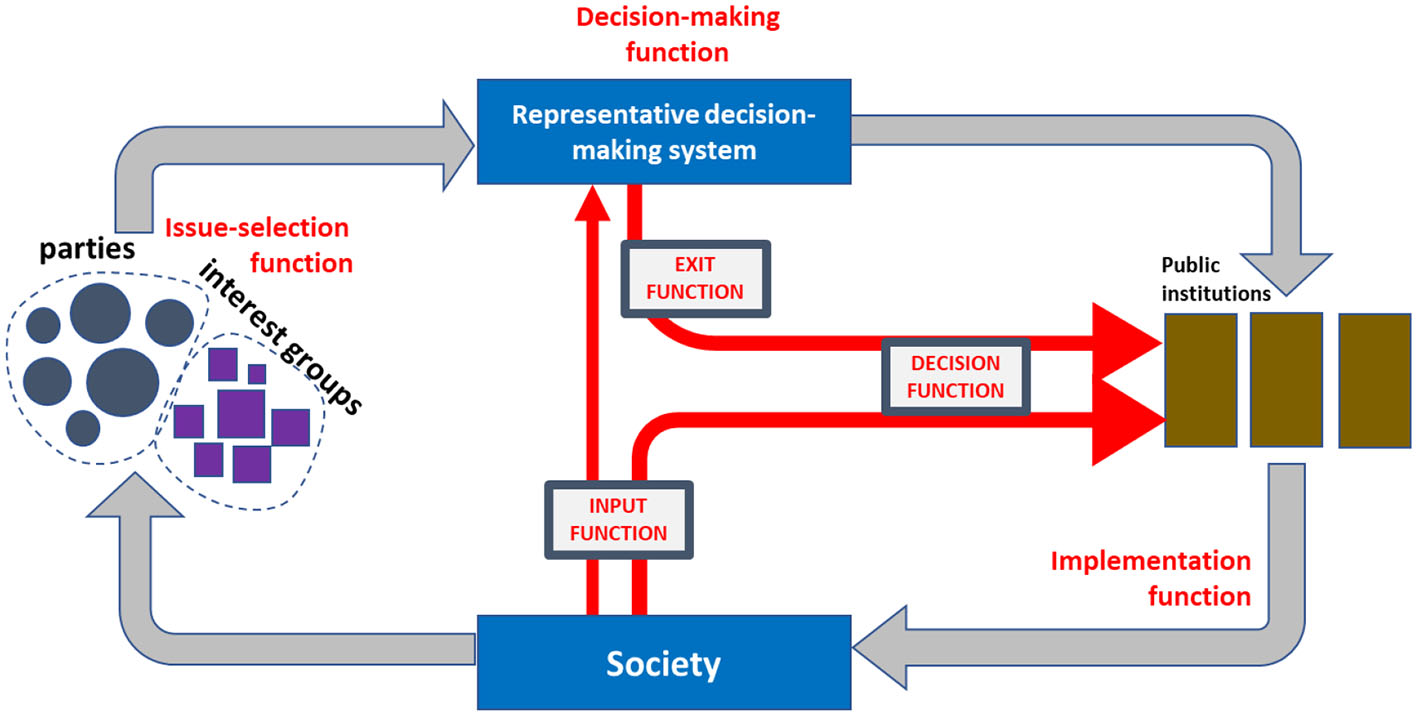

In the classic understanding of political systems, intermediary actors like political parties or interest groups select and transport political issues into the institutions of democratic decision-making (Figure 1) (Easton, 1965). Respective decisions are then implemented by public institutions and generate new political demands within the society. Yet instruments of deliberative and direct democracy offer alternative or additional functions within this understanding of politics. In the following, we further elaborate on what we consider to be the three main functions of direct democracy in democratic systems: (1) channeling political input into the decision-making stage by circumventing organized intermediary actors and selection functions (input function), (2) suspending representative decision-making by channeling political issues out (exit function), and (3) producing decisions about political questions (decision function). The magnitude of these functions depends on the institutional design of the single instruments of direct democracy.

Figure 1

Simplified policy cycle of contemporary democracy (based on Easton, 1965) including the three system functions of direct democracy (red lines) (source: by the authors).

In his classic work about the functional properties of the referendum, Smith (1976) points to the source of initiation as the main difference between various types of referendums. Accordingly, in referendums, the source of initiation is the government itself; by only launching those votes, it is sure to win. These are therefore controlled votes. On the other hand, popular initiatives are labeled as uncontrolled referendums, as they are about to bring change to the existing status quo. In addition, “between the polarities, there are varying degrees of “control”, depending on the “rules” which operate and the prevailing balance of political power” (Smith, 1976, p. 6). This view on the capacity to launch a vote as the main criterion for distinguishing instruments of direct democracy found its way into the literature (for example Moeckli, 1994, p. 50; Serdült and Welp, 2012, p. 70), either in the terminology of controlled and uncontrolled referendums (Vatter, 2000, 2009; Morel, 2007) or in the slightly different perspective of bottom-up and top-down instruments (Papadopoulos, 1995; Serdült and Welp, 2012; Cheneval and El-Wakil, 2018). However, there are also authors questioning whether votes launched exclusively by political authorities are direct democracy at all, given their plebiscitarian character (Marxer, 2018, p. 33). In terms of the voting issues, the question is: “Can the initiator be the author of the proposal?” (Morel, 2018, p. 31). Here, the same dualism between bottom-up and top-down instruments applies.

Furthermore, scholars also point to the question of whether votes are formally binding or consultative as a typological criterion (Moeckli, 1994, p. 50; Altman, 2011, p. 8; Morel, 2018). Yet Jung argues that this aspect can be neglected as referendums are usually politically binding (Jung, 2001, p. 86). Consequently, the compulsoriness drops out of her and other typologies (Hornig, 2011a; Merkel and Ritzi, 2017, p. 24), even though we miss empirical proof for this thesis so far. Further typological criteria discussed in the literature relate to the qualifications for validity of voting decisions like quorums of participation or approval, or the relationship to the legislative. In terms of the latter aspect, the question is whether the people's vote comes instead of a parliamentary decision or afterward (Jung, 2001; Hornig, 2011a; Merkel and Ritzi, 2017). Consequently, votes can be deciding or affirming.

In the following sections, we rely on the typology of the Direct Democracy Navigator project. It reflects the aforementioned discussion and identifies three main types: (1) initiatives are launched by the people in a bottom-up logic; (2) referendums (in a narrow sense) are launched top-down by political authorities; and (3) the mandatory referendum is triggered by law (constitution). This threefold approach is widely established in the literature (except for example Moeckli, 1994). However, this order of instruments is newly added to the three functions of direct democracy.

2.1 The input function of direct democracy

The input function in modern democracy serves to select and transport political issues to the decision-making stage. In the representative sphere, this linkage function is provided for by political parties and organized interests. Even though different in quantity and quality, instruments of direct democracy can serve this function, circumventing the organized interests. Research has shown that political parties in particular often make use of direct democracy (Hornig, 2011a; Rochat et al., 2022) and that political motives play a major role for parties while launching votes (Morel, 2007). Here, the logics of party competition serves as a filter for issues when potentially launching votes. This can be circumvented with direct democracy, and issues can either be transported to the parliamentary decision-making system for further negotiation or be transported to an alternative decision-making: the referendum. In the latter case, political decision-making is completely autonomous from the parliamentary arena. Both input channels relate to specific instruments of direct democracy.

The first input channel provided by direct democracy completely avoids the representative system and leads political issues directly to the referendum as an alternative decision-making system. Here, the people can choose the content and timing of a vote; in the terminology of Smith, a vote is uncontrolled by political authorities. Votes can be launched by collecting a prescribed number of signatures. The fact that in practice these are often organized interests such as political parties (Hornig, 2011a; Serdült and Welp, 2012, p. 82) is another matter. For such a mechanism, different terms can be found in the literature: “popular initiative” (Vatter, 2009, p. 128; Altman and Sánchez, 2020, p. 34), “legislative initiative” (Qvortrup, 2018, p. 1), “citizen-initiated referendum” (Moeckli, 2021, p. 6) or “law initiative” (Hornig, 2011a, p. 37). This instrument is also labeled as an “active instrument” according to Vatter “because of the active role played by non-governmental actors (e.g., citizens) in launching them” (Vatter, 2009, p. 128). Similar to the International IDEA (2008), we use the term citizen initiative from the Navigator typology to underline the role of the citizens in the timing and content of the vote. By using citizen initiatives, political actors can circumvent the usual intermediary actors (and their proper preferences) and insert political questions directly into the process of decision-making (by public vote).

The second input channel is transporting political issues directly into the parliamentary arena. This corresponds to the so-called agenda initiative (International IDEA, 2008; Moeckli, 2021). It allows for the people to make parliament discuss a certain issue. There is unclarity in the literature on how to handle and classify the agenda initiative. On one hand, “the citizen initiative must undoubtedly be ranked among popular rights increasing the direct influence of the people on legislation” (Morel, 2018, p. 30). What the agenda initiative has in common with other forms of direct democracy is the collection of signatures. However, on the other hand, the agenda initiative is distinct from other instruments of direct democracy for a clear reason: It is missing a vote. For Altman, a vote is an absolute prerequisite for direct democracy, which is why he excludes “legislative popular initiatives” from direct democracy (Altman, 2011, p. 7). Furthermore, other typological considerations leave it out (see for example, Vatter, 2000, 2009; Hornig, 2011a). In our concept, we can escape such discussions as we focus on the system functions of direct democracy. The agenda initiative is included, as it serves to insert issues directly into the decision-making process by circumventing the filters and organizations of organized interest. Yet, at the same time, we acknowledge the qualitative difference between the agenda and the citizen initiative, as the destination of input transported by the agenda initiative is nonetheless the hands of representative actors.

2.2 The exit function of direct democracy

In the exit function, direct democracy does not serve as a tool to insert political input into the system but offers a way to lead it out again and transfer the authority of deciding to the people. It offers an exit-option for institutional actors to break out of the rules of legislation in representative organs. This may be especially relevant for the opposition or political minorities in general, but it may also serve to dissolve possible blockades within the political system (Hornig, 2011b). Analogous to specific institutional designs of direct democracy, the exit function knows five different channels. They differ according to how strongly they suspend representative proceedings by assigning decisions to the referendum.

The first channel represents only a minor intervention in the representative logic. Here, either the government or the majority in parliament decides to hold a referendum, whereas the motives for this can be manifold (Morel, 2007). Launching the vote, however, takes place within the framework of competencies. Majoritarian actors like governments (usually) benefit either from a majority of electoral support (in presidential systems) or from a majority in parliament (in parliamentarian systems). The issue and the point in time of the vote likely resemble what Smith called a controlled referendum. Political authorities expect to win the vote and therefore launch it. Typologically, this constellation resembles an authority referendum in the Direct Democracy Navigator typology. While Morel (2007, 2018) separates the government and the legislative as actors in her typology, the Navigator combines them in one type. The important notion here is the majority, as votes are launched out of a position of strength and not to veto a law (see below). This first case represents the weakest deviation from the logics of representative systems.

The second channel is also used by political authorities, but this time under different conditions. The government or parliament makes use of direct democracy to avoid the passing of a law by the other institution capable of doing so. The crucial point is that on this level the actors are in a horizontal relationship and can block each other. The same applies in a bicameral system when one chamber is entitled to veto by referendum a law proposal coming from the other chamber. Altman and Sánchez (2020) mention that the term plebiscite marks votes used for “the bypassing of one representative institution by another (usually the executive avoiding the legislative branch)” (p. 29). In our understanding, this constellation is not necessarily problematic but can be interpreted as a result of the division of power and as a tool to release blockades (Hornig, 2011b). Typologically, this constellation matches the veto referendum in the Direct Democracy Navigator typology. Compared with the first level, the (horizontal) veto referendum represents a stronger suspension of respective regulations as an actor without a majority can avoid the finalization of a law.

The third exit channel is available for a structural minority within the political system. This can be a number of members of parliament or, in bicameral systems, even a minority in one chamber. Furthermore, subnational minorities may be entitled to cease regular proceedings by calling for a referendum. Here, direct democracy offers the respective minority a tool to equalize its status, divert a political process out of the parliamentary agenda, and improve its chances in a veto referendum. Such a veto referendum is not always present in the literature (see for example, Vatter, 2009; Altman and Sánchez, 2020, p. 34). Moeckli (2021) combines the referendum and veto referendum in one type, which “can be triggered by the legislature (or parts of it), the executive (or parts of it) or (a certain number of) subnational entities” (p. 6). Nonetheless, we include this second version of the veto referendum in our concept to highlight the differences within the exit function.

The fourth channel of the exit function represents a stronger deviation from the logics of representative systems, as certain decisions are automatically diverted to the people. Some constitutions prescribe that a public vote must be held when the legal status quo of a particular matter is changed by the law-making institutions. This can either be the constitution itself or the electoral laws and international treaties. In these cases, a vote is mandatory. Almost all typologies include a mandatory referendum as a proper type (for example Morel, 2007; Vatter, 2009; Hornig, 2011a; Marxer, 2018; Moeckli, 2021, p. 128). The mandatory referendum guarantees the redirection of decisions to the referendum in certain policy fields, independent from the will of political majorities.

Finally, the last channel of the exit function represents the strongest suspension of parliamentary system proceedings by direct democracy as any political actor is entitled to call for a referendum through the means of a signature collection. Existing laws, new laws, or law proposals, which originate in the representative system, can be decoupled from parliamentary approval and voted upon. This means that the citizens can determine the timing of a vote, but not the content. Respective designations in the literature are: “referendum initiative” (Hornig, 2011a, p. 37), “popular initiative” (Morel, 2007, p. 1043), “rejective referendum” (Altman and Sánchez, 2020, p. 34), “citizen-initiated referendum” (Qvortrup, 2017, p. 146), “referendum” (Altman, 2016, p. 1211), “optional referendum” (Vatter, 2009, p. 128), and “facultative referendum” (Marxer, 2018, p. 26). Moeckli (2021) speaks of a citizen-initiated referendum with a proactive version (our citizen initiative) and a rejective version (p. 6). Following the Navigator typology, we call this instrument veto initiative to indicate the role of the people and the main function. Even though such a veto instrument is usually classified as a bottom-up instrument due to the open capacity to launch such a vote, we only focus on the capacity to divert content from the political decision-making system to the referendum—here the strongest intervention level.

2.3 The decision function of direct democracy

The decision function of direct democracy serves to end the political process by leading to decisions by public vote. This is the core of direct democracy as the people make use of their rights and vote. This function does not apply to the agenda initiative. For all other instruments, the question is: how strong is the decision function? The more definite the voting result of a referendum is, the stronger the decision function. The decision-making function asks whether there are formal qualifications to be met in order for direct democratic decisions to become formally effective, similar to the qualifications of votes taken in parliament. In the representative arena, decision-making needs to fulfill certain demands, for example, special supermajorities in the case of constitutional reform. In the direct democracy arena, instead, the quora of participation or approval play a vital role (Aguiar-Conraria and Magalhães, 2010; Herrera and Mattozzi, 2010; Aguiar-Conraria et al., 2016). “Basically, quorums in general have two major objectives: to stop change and to provide legitimacy” (Altman, 2016, p. 7).

2.4 Discussion of the proposed concept

The purpose of the presented approach is to document the strength of the system functions of direct democracy within one political system. To have a functioning direct democracy, the decision function and either one of the inputs or the exit function must be in place. However, depending on the respective national context and the variety of instruments, all three functions can be present as well. The average of all three subfunctions constitutes the final system function of the direct democracy score.

The approach presented differs from previous work in the field primarily through three characteristics. First, the approach offers an empirical understanding of direct democracy in representative systems that aim at the discussions about the agenda initiative as an instrument. By clearly assigning a function within the political system while taking into account the limited resources of the agenda initiative, the present concept can mediate between the existing works. Second, by precisely naming the functions of direct democracy, the otherwise rigid dualism of top-down and bottom-up instruments can be avoided. From the authors' point of view, this dualism too often obscures crucial differences between the instruments. Third, the proposed concept still manages to compress the complexity of direct democracy in representative systems into three understandable functions and thus create new accessibility to the subject.

At the same time, our approach is not limitless and undifferentiated, as the example of the recall process makes clear. The three functions do not include the option that the people can directly decide whether a public official should resign from office or whether to recall elected officials by a public vote, the so-called recall (International IDEA, 2008; Altman, 2011; Serdült and Welp, 2012; Marxer, 2018). The two obvious similarities with direct democracy are the collection of signatures and (if sufficient) the public vote about the question at stake. The latter point is also the reason why Altman includes the recall in his system of direct democracy (Altman, 2011). Yet, we leave the recall because we think it refers too strongly to the sphere of representative democracy and the question of who should be in public office as a representative of the public. Just as elections bring someone into office, a recall can bring this person out again. No surprise, Altman speaks of a “recall election” (Altman, 2016, p. 1210).

3 Methods

We rely on the data from the 277 instruments of direct democracy on the national level in 103 countries3,4 worldwide. The selection of countries is based on the “Freedom in the World” assessment by Freedom House5, comparable to Morel (2018) and Silagadze and Gherghina (2020). Accordingly, countries have to be rated as free or at least as partly free6 to be integrated into the navigator dataset.7 In 2022, a total of 144 countries and territories worldwide fell into these two categories. This means that instruments of direct democracy are present (on the national level) in 103 of 144 countries worldwide classified by Freedom House as free or partly free (71.5%). Of the 277 different legal provisions for direct democracy on the national level in the 103 countries, there are 85 mandatory referendums (30.6%), 83 authority referendums (29.9%), 41 agenda initiatives (14.8%), 29 citizen initiatives (10.4%), 21 veto initiatives (7.5%), and 18 veto referendums (6.4%). In the terminology of bottom-up and top-down instruments, the former account for 91 instruments (32.8%) and the latter for 186 cases (67.1%).

How do we operationalize the three functions? Leemann and Stadelmann-Steffen (2022) follow the question of whether instruments of direct democracy on the subnational level elevate satisfaction with democracy and present a measure for subnational direct democracy. Their concept contains three major elements to conceptualize direct democracy: openness, effectiveness, and threat. Even though their research question is completely different from our approach, it underlines that the analysis of direct democracy has constitutive elements. Our measurement of the system functions of direct democracy builds on three elements somewhat similar to the first two of Stadelmann-Steffen and Leeman. These are the availability and permeability of the input and exit channels, as well as the effectiveness of the decisions. What Stadelmann-Steffen and Leeman call threat refers to the actual use of instruments of direct democracy and therefore drops out in our consideration as we only deal with the formal institutions of direct democracy.

(1) Availability: The first criterion takes into account to what degree the different channels of a function are available in a legal design of direct democracy. Yet, we do not simply count the presence of the instruments but also carry out a weighting based on the importance of the respective channel for the function. For the input function, we refer to the citizen initiative and the agenda initiative as possible channels. Both circumvent the process of intermediary actors selecting issues and instead offer a shortcut into decision-making processes. In terms of the importance of the function, the main difference between them is the destination of the political input they transport. The citizen initiative directly leads to a referendum, and the agenda initiative leads to the parliamentary arena. While both instruments circumvent the intermediary actors, the citizen initiative also circumvents the parliamentary system. Therefore, we assign it 0.75 points and the agenda initiative 0.25 points. With both types of input instruments present, the theoretical maximum score is 1 point.

In terms of exit function, the five different channels are assigned different scores in an ascending way as well (Table 1). The leading question is how strong does an instrument suspend representative processes? The exit character of a referendum becomes stronger when it is triggered by minorities or even the people. The more direct democracy allows for circumventing the mechanisms of majority and minority, the stronger the exit function. The maximum availability of the exit function is reached when all exit channels are present (1 point). If one type of instrument is present more than once, it will be counted only once nonetheless, because every further one does not change the function per se but touches upon further policy areas, which would be reflected in the permeability score (see below).

Table 1

| Launching actor | Related instrument | Score |

|---|---|---|

| People | Veto initiative | 0.3 |

| Constitution | Mandatory referendum | 0.25 |

| Minority | Veto referendum | 0.2 |

| Authorities (Veto) | Veto referendum | 0.15 |

| Authorities (Dominance) | Authority referendum | 0.1 |

Measurement of the availability of the exit function.

To acknowledge the formal demands for signature collection for the bottom-up instruments (citizen initiative, agenda initiative, and veto initiative) as well, we use a signature-time-ratio score. The signature requirement to launch a vote is supposed to indicate the level of support within the electorate (Schaub and Frick, 2022). The signature thresholds of bottom-up instruments are at the center of many elaborations on direct democracy (Leemann and Stadelmann-Steffen, 2022). To keep the measurement comprehensible and simple, we calculate the percentage of the electorate that needs to support a proposal within 1 month in order to fulfill the requirements. When there is no time regulation, we calculate with 1 year. We subtract the signature-time-ratio score from the 0.25 points, 0.3 points, or 0.75 points of the instruments. In the case of duplicate instruments, we calculate the averages. When the input function is missing completely, the score is automatically 0 points.

(2) Permeability: The second aspect asks the question: How broad is the spectrum of issues that are allowed to be channeled through the input and exit functions? While one instrument may exclude an issue, it may be accessible through another instrument nonetheless. The consequence may be that all issues are accessible through direct democracy but not with every instrument. But what are all the issues? Silagadze and Gherghina (2020) investigate what policies have been the subject of referendums throughout history and how they can be grouped thematically. They present a fourfold concept of issues. The four policy domains are the international system, domestic norms, welfare, and postmaterialist issues. Every domain can be divided further according to the degree of abstraction.

We adapt the concept of Silagadze and Gherghina (2020) to the dataset provided for by the Direct Democracy Navigator. Therefore, we merge the four policy domains of Silagadze/Gherghina with the seven policy domains of The Direct Democracy Navigator dataset.

-

The domain “international system” matches the Navigator's policy area “International Treaties”.

-

The domain “domestic norms” is assigned to “constitutional policy”, which combines four related policy areas of the Navigator (constitution, basic principles and fundamental rights, institutional structure,8 and state territory9).

-

Instead of welfare, we conceive the Navigator policy area “Finances, taxation, budget” as the third policy domain. Even though related, the Navigator category is narrower as it relates to public spending and anything related to public finances like taxes, tariffs, charges, public service salaries, and pensions. In the present analysis, the finance category explicitly includes the annual state budget.

-

The fourth policy domain we simply call “others”. Here, we make use of the fact that the Navigator reports whether issues are explicitly excluded from voting by law or whether single voting instruments are explicitly reserved for certain issues. When issues 1–3 are excluded, the “other” domain always remains free as there are some allowed issues in any case. Otherwise, the instrument would make no sense. In the contrary case, when instruments are reserved for single policy areas like the constitution, the “other” category may be classified as restricted as well.

This leads to the following calculation method. For every relevant instrument available on the national level in a country, we identify restrictions in the four policy domains, separated according to exit or input function. In the example of Table 2, the first instrument has restrictions in constitutional policy, international treaties, and finances, whereas the “other” category has to remain free to acknowledge that there are issues to be voted upon after all. The second referendum is solely designed for voting about the merger of communities, which is one of the four subareas of the “constitutional policy” category. As only one of the four subcategories is not restricted, it leads to a score of the constitutional policy domain of 0.75 points. For the final permeability score, we calculate . In the present case, the permeability score is 0.84 points [1–(6.75/8)]. Voting instruments without any issue restrictions have a score of 1 point automatically. A total revision of the constitution is regarded as an instrument without any policy restrictions as a new constitution can affect all four policy dimensions.

Table 2

| Constitutional policy | International treaties | Finance, budget, taxes | Other | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constitution | Rights | Institutions | Territory | Total | ||||

| Instrument 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Instrument 2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sum | 1.75 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Restriction score = 6.75 | ||||||||

Example of the measurement of the issue permeability of voting instruments (1 = restriction).

(3) Effectiveness: Voting results can be generally binding, non-binding, or conditionally binding. For the latter, the conditions for validity depend on certain requirements of participation and approval, so-called quorums. Unfortunately, in the literature, we find no coherent operationalization of these conditions. Again, the quorums are part of Altman's (2011; 2016) rich body of methods for constructing indices of direct democracy. His main message is that the different qualifications have to be looked at in a common picture and not as separate institutions. Therefore, he introduces the SQS-concept, which allows us to visually identify the logical possibilities of status quo change for single instruments. This is also used by Leemann and Stadelmann-Steffen (2022). We agree with the argument, that “[r]egardless of whether the decision is binding, any decision taken directly has a great dose of legitimacy” (Altman, 2016, p. 10). But this dose of legitimacy can vary, and therefore, we stick to the formal regulations.

Our measurement is less complex as we “only” report the conditions discussing their interactions. A binding vote without any quorums is automatically assigned 1 point, while a non-binding vote is assigned 0 points. Measuring the range of conditionally binding votes in between relates to the quorums of participation and approval. Quorums always formulate some condition involving a certain percentage of the electorate to do something—either approve a bill or participate in the vote. The normal majority requirement in votes is not yet a quorum. For both types of conditions (participation and approval), we calculate 1 minus the percentage rate of the respective quorum. For example, an approval quorum of 75% leads to a score of 0.25 points (1–75% = 25). The final permeability value is always the average of the scores of the participation and approval dimensions.

In the Direct Democracy Navigator dataset, we only find 6 out of 277 instruments of direct democracy on the national level with both quorums in place at the same time (2.1% of all cases). In five cases (1.8% of all cases), a territorial dimension is also part of the conditionality, what Altman calls the administrative quorum (AQ). In one variant, voters in a certain number of subnational territorial units need to support a proposal. One well-known example of this is the Swiss constitutional citizen initiative. In the second variant, a certain level of participation in a certain number of subnational territorial units is demanded. Depending on whether the participation or approval dimension is connected to the territorial dimension, both are multiplied. For example, an approval quorum of 0.5 points and a territorial quorum of 0.5 points lead to a new approval score of 0.25 points. The deterioration of the score is to indicate the higher requirements for success in the vote.

4 Results: the system functions of direct democracy in international comparison

We start by displaying the results for the single functions, then compare them, and finally generate a total system function score composed of all three functions. First, we turn to the exit function as it is part of the majority of political systems. The average strength of the exit function is at 0.39 points (0.30 points availability; 0.48 points issue permeability). The strongest exit function of direct democracy can be found in Austria (0.68 points), Switzerland and Moldova (both 0.65 points), and Iceland (0.63 points). In the Austrian case, three exit channels are available on the national level: The mandatory referendum about the complete revision of the constitution of the country, the veto referendum on partial constitutional revisions, and two authority referendums (“Volksabstimmung” und “Volksbefragung”). Apart from the veto referendum on constitutional revisions, issue restrictions are almost absent, leading to a high issue permeability of the Austrian exit channels. Neighboring Switzerland, on rank 2, has two veto initiatives on the partial and total revision of the constitution (even though only one is counted here) and the mandatory constitutional referendum. Due to the issue restrictions, the average issue permeability is at 0.5 points. At the other end of the spectrum are the Netherlands due to the missing exit function and then Honduras with only 0.13 points. In the Netherlands, there is only an agenda initiative in place, and the authority referendums in Honduras are strongly restricted in their use.

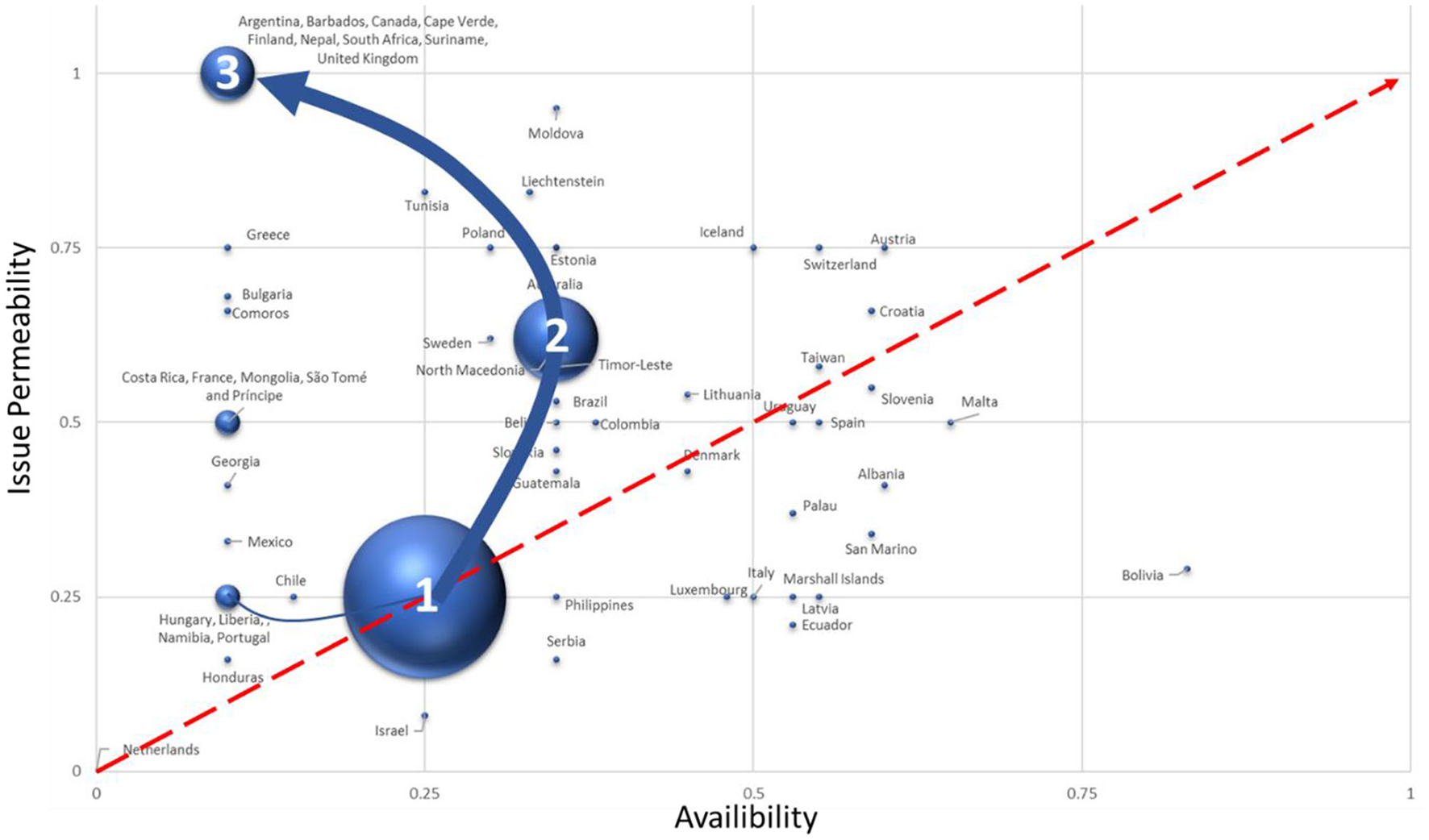

Figure 2 shows three main clusters of countries, and many single cases spread around the spectrum. The largest bubble belongs to the 27 countries with only a mandatory referendum and a low issue permeability of 0.25 points. Typically, these are mandatory referendums for constitutional reform. The exit function of direct democracy is rather weak in total, as only one instrument with one policy area is available. Interestingly, these are countries with British heritage, but also Japan and Czechia. The second bubble stands for the 14 countries with the combination of (at least) one authority referendum and (at least) one mandatory referendum (together 0.35 points). The respective score could also be the result of a combination of the two forms of veto referendums, but this case does not apply. Thus, the exit function in these countries becomes stronger as a further instrument also brings further issues available for diverting out. The crucial point here is that the authority referendum is the instrument with the least disruption to representative proceedings (see below). The third bubble represents a group of eleven countries with only an authority referendum present. This group is very diverse, including countries like Nepal, Finland, Argentina, and Namibia. In sum, half of all countries in the study are part of these three groups.

Figure 2

Issue permeability and availability scores per country for the exit function and implied main dynamic in the function (blue lines).

What is the main dynamic of the exit function? About half of the cases form a line from the lower left to the center and then further to the upper left corner. This distribution of cases points to a certain logic in the exit function. When there are only mandatory referendums present, issue permeability is low. Usually, only constitutional issues can be diverted out. While constitutional policy is of course important, it is only one of four policy areas. Once authority referendums also come into play (in cluster no. 2), the issue permeability increases as they are only rarely restricted. Is the authority referendum the only instrument (like in country cluster 3)? Issue restrictions often drop completely and the issue permeability is high. In the authority referendum cluster in the upper left corner, the power to use direct democracy is concentrated in the hands of political authorities only and the deviation from the regular mechanism of representative politics is small. Presidents and parliaments can use the referendum at their disposal and face almost no issue limits. Therefore, in this case, the exit function serves rather as a power concentration. The more the right to divert issues out of the parliamentary system is dispersed, for example to the constitution, the higher the issue restrictions.

Cases in cluster 1: Botswana, Czechia, Dominica, El Salvador, Fiji, Ghana, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Japan, Kenya, Kiribati, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mauritius, Micronesia, Nauru, Niue, Panama, Peru, Samoa, Seychelles, St Kitts & Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines, The Bahamas, and Vanuatu.

There are only a handful of cases pointing to the exit function as a tool serving the division of power. Here, a higher availability of the exit function comes along with higher issue permeability. This applies to Switzerland, Austria, Croatia, Taiwan, Slovenia, and Malta. As already mentioned above, the two alpine countries, Austria and Switzerland, possess a variety of exit instruments with comparatively minor issue restrictions. In Croatia, a mandatory referendum, a veto referendum, and a veto initiative allow for a rather broad spectrum of exit channels with minor issue restrictions. The Croatian constitution provides in Art. 87 for the president to start a referendum, with the consent of the prime minister, “on a proposal to amend the Constitution or any such other issue as he/she may deem to be of importance to the independence, integrity, and existence of the Republic of Croatia.”10

The highest availability of the exit function has been measured in Bolivia. There the mandatory referendum, the veto initiative, the authority referendum, and the veto referendum lead to an availability score of 0.85 points.11 However, not all instruments have the same access to the policy arenas. The confirmation of international treaties is the sole policy area that allows for a mandatory referendum, a veto referendum, and a veto initiative. Three further instruments only deal with the institutionalization of a constitutional convention. Thus, the high number of eight exit channels of direct democracy mainly deals with the issues of international treaties, constitutional conventions, and constitutional reform. In sum, Bolivia has the 10th strongest exit function in total. But apart from Bolivia, the lower right corner of Figure 2 is empty as the combination of a high availability and lower issue permeability does not apply. Having the spectrum of channels available but nothing to decide seems futile, whereas having only one of a few channels but all the policy options is rather common. With that, the exit function is rather unbalanced pointing toward a concentration of power through direct democracy. The higher the availability of the function, the lower the issue permeability, yet with a dozen countries as exemptions.

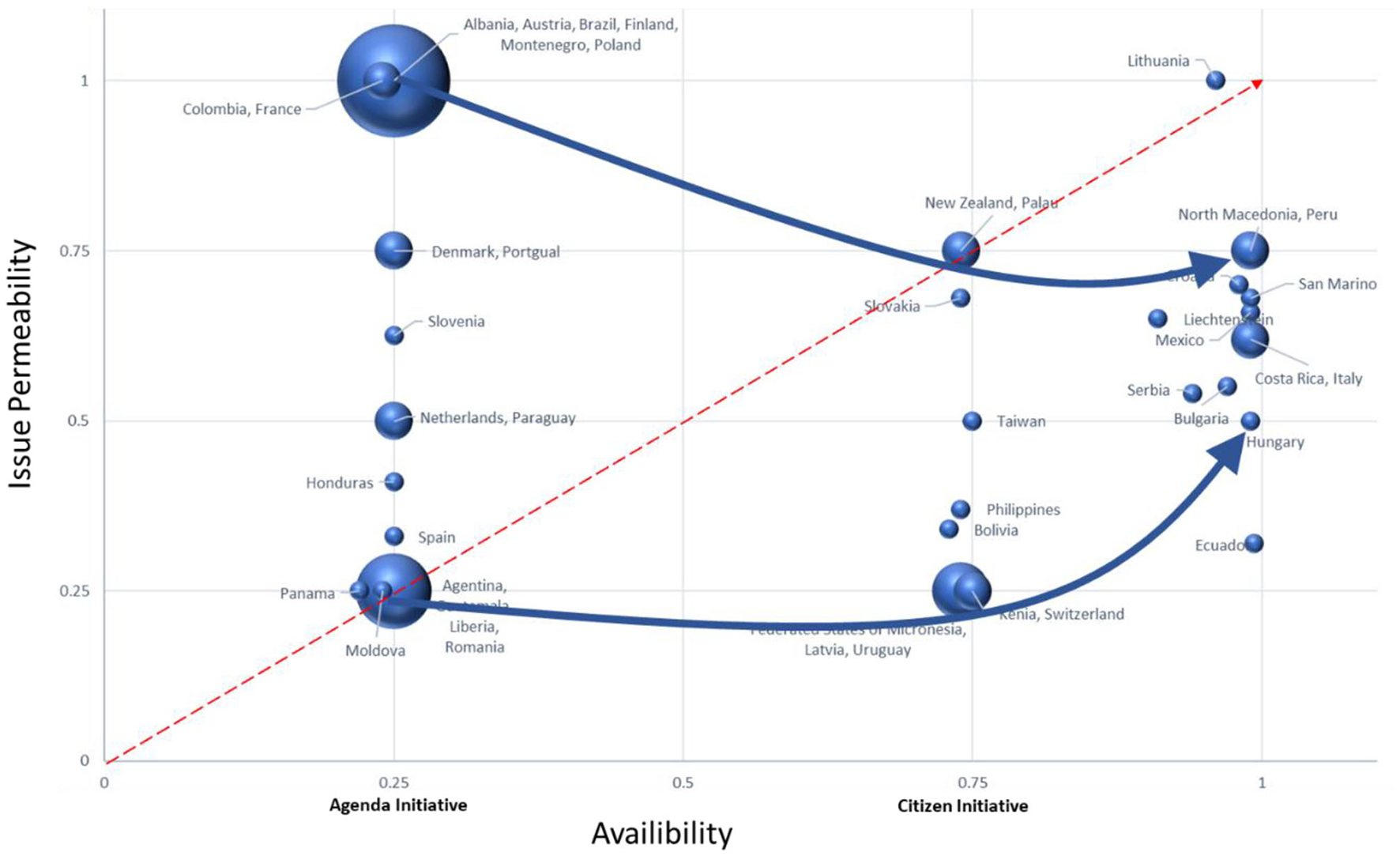

Next, we turn to the input function, which is present in only 45 of the 103 countries. In contrast, in the majority of the democratic and free countries with direct democracy on the national level, bottom-up instruments are missing completely. This group automatically scores 0 points in this function. The average score of those 45 countries with an input function is at 0.56 points (availability score 0.55 points; issue permeability score 0.56 points). The highest national scores belong to Lithuania (0.98 points), Peru and North Macedonia, (0.87 points), and Georgia and San Marino (both 0.84 points). In Lithuania, we find an unrestricted agenda initiative leading into the parliamentary decision system and an unrestricted citizen initiative leading to the referendum. The small deduction of 0.02 points is explained by the signature-time ratio, which is minimal nonetheless. The first 10 countries in the list all combine a sort of agenda initiative with a citizen initiative and score between 0.91 and 0.99 points in terms of availability. The Italian “referendum abrogative” allows the people to delete complete (ordinary) laws or cut out pieces. With this opportunity to cut out even single words, the instrument serves rather as a citizen initiative and less as a veto initiative (Hornig, 2021). At the bottom of the list are six countries with a score of 0.25 points (Argentina, Guatemala, Romania, Moldova, Liberia, and Panama). In these countries, the agenda initiative, as the only available instrument, is strongly restricted in its function. Switzerland only comes at rank 28 with an availability score of 0.75 points and an issue permeability of 0.25 points—combined 0.5 points. The low Swiss permeability score is due to the restriction of the citizen initiative to constitutional matters.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of the relevant cases (with an input function) according to the availability and issue permeability scores. Obviously, the distribution is determined by the occurrence of the two input channels. On the left side, along the vertical 0.25 points line, we find the first group of countries with only the agenda initiative as input channels. The main point here is that the countries are lined up along the entire spectrum from 0.25 points to 1 point. A bigger cluster of six countries can be found in the upper left corner. Here, the issue permeability is high, and direct democracy offers a full-scale access to the parliamentary decision-making system circumventing the intermediary actors and logics. At the bottom of this line is a group of six countries (Spain, Argentina, Guatemala, Moldova, Romania, Liberia, and Panama), where access through the agenda initiative to the parliamentary arena is restricted to one policy area only. Thus, the main message here is that agenda initiatives can be either fully open or highly restricted.

Figure 3

Issue permeability and availability scores per country for the input function and main dynamic in the function (blue arrows).

Further to the right in Figure 3, we find the next vertically arranged group of countries. The majority of them are clustered at the lower end. These are those countries with only one (or more) citizen initiatives but no agenda initiatives. Here, we find countries like Switzerland, Kenya, and Uruguay. These are citizen initiatives with low issue permeability, allowing the transport of only one specific policy area, mainly constitutional policy. The Swiss constitutional initiative is the best example here. The further the cases are located up the vertical 0.75 points line, the more policy areas are possible to address. The strongest instruments in this group can be found in New Zealand and Palau, where the scores on both axes are at 0.75 points. In the case of the Philippines, the Initiative and Referendum Act states that an initiative can deal with a “proposed law sought to be enacted, approved or rejected, amended or repealed”, which means that laws can be given a new meaning. This is counted as a citizen initiative and not as a veto initiative.12 On the right side of the figure, we find 13 countries with the highest availability scores as both input channels are available. The absolute highest score belongs to Lithuania, as already mentioned above. The other countries with both access channels available know some degree of issue restriction. It is important to remember that the scores here are average scores combining both input channels.

When looking for a general dynamic in the input function, the differences between the three groups of countries within Figure 3 seem to be relevant. As mentioned above, the “agenda initiatives only group” comprises instruments with and without issue restrictions. However, when it comes to the citizen initiatives leading directly to the referendum, issue restrictions are usually higher; the visual distance between the cases on the vertical 0.75 points issue permeability decreases with New Zealand and Palau being at the top. The message seems to be that: As long as representative institutions have the final say, channels of direct democracy can be wide open. However, when people decide directly, the window for passing issues through is never fully opened. No surprise then that those countries with both instruments present are all more or less located in the middle of the issue permeability spectrum.

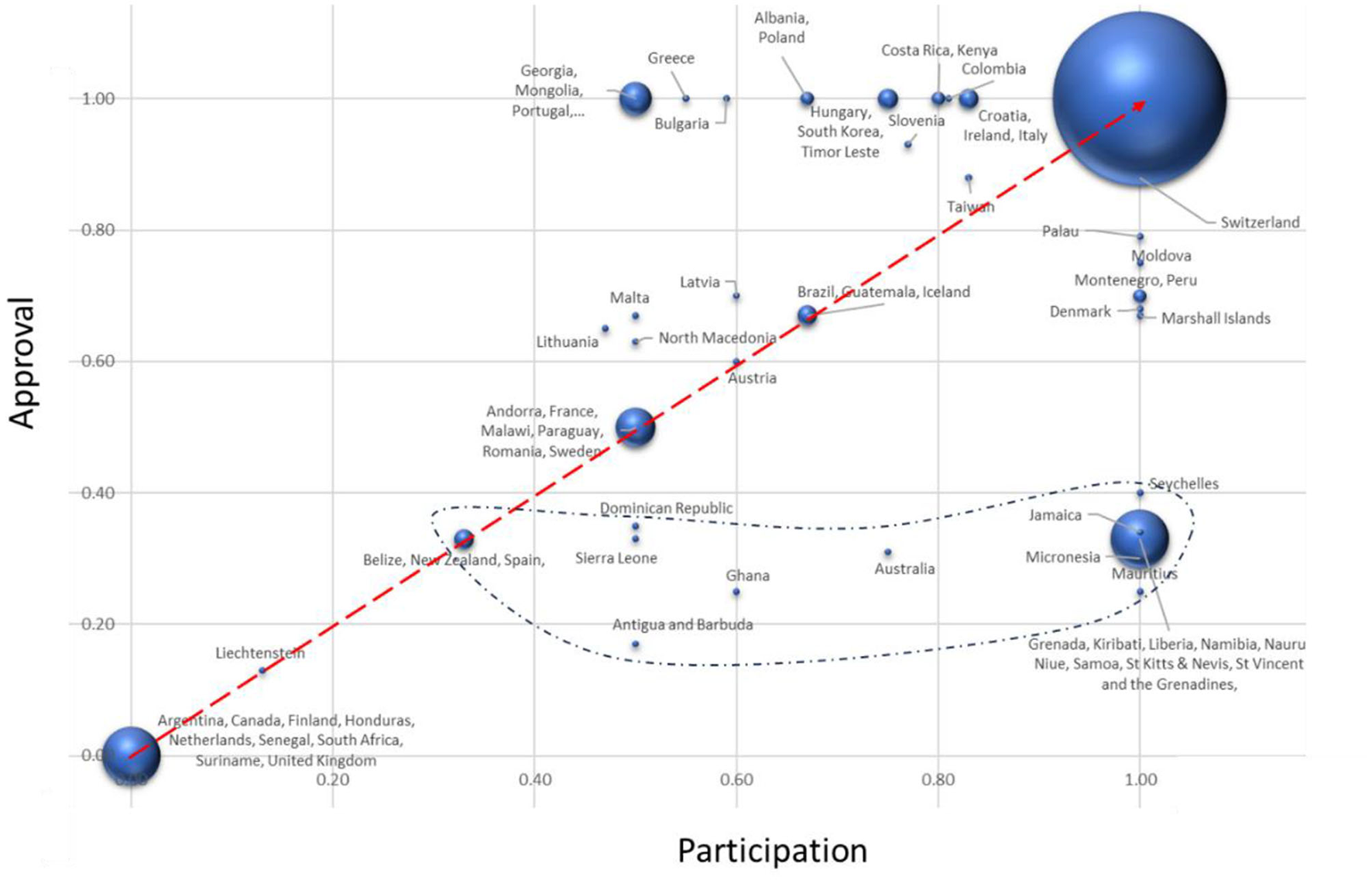

Finally, we come to the decision function of direct democracy. The average decision strength score is 0.71 points, which is clearly higher than the average scores of the two other functions. Figure 4 shows the distribution of the countries according to the effectiveness. We see that by far the largest cluster of 27 countries (26.2%) is located in the upper right corner with a score of 1 point on both axes. In these countries, the respective instruments of direct democracy are unconditionally valid, independent of the level of participation by the people or the level of approval for a proposal. Here, the effectiveness is high and decision-making by referendum always leads to a change of the legal status quo. Under these conditions, decision-making by direct democracy is equivalent to the parliamentary process in its effect. In direct contrast, in the lower left corner, we find those nine countries (8.7%) where voting results are generally non-binding. This group comprises countries as diverse as Argentina and Honduras, but also the UK, Canada, and South Africa.

Figure 4

Approval and participation scores per country (decision function).

Cases in the main cluster: Barbados, Botswana, Cape Verde, Chile, Comoros, Czechia, Dominica, El Salvador, Estonia, Fiji, Guyana, Israel, Japan, Lesotho, Luxembourg, Madagascar, Maldives, Nepal, Niger, Panama, Philippines, Sao Tome and Principe, San Marino, St. Lucia, The Bahamas, Tunisia, and Vanuatu.

In the remaining 71 countries, the regulations of direct democracy prescribe some sort of conditions for validity for one or all instruments of voting present. There are some countries with mixed regulations, where one voting instrument knows some qualifications in terms of participation or approval and the other instruments do not. Probably the most famous example of such a mixed picture is Switzerland, where only the citizen initiative on the partial revision of the constitution prescribes the approval by the voters in general and the voters in the majority of the subnational cantons. In contrast, the other three Swiss instruments on the national level have no further qualifications for validity, not even the citizen initiative on the complete revision of the constitution. Another well-known case is Italy with the “referendum abrogativo” and its participation quorum of 50%, which has played a major role in its decision function in the past (Uleri, 2002). Besides the referendum abrogative, the Italian constitutional referendum prescribes no further requirements in terms of participation or approval.

In the lower half of Figure 4, a group of countries is connected through a dashed line. These are almost all countries of British heritage. The common feature of this group of countries is that voting results are bound to the degree of approval and sometimes also to the level of participation. Interestingly, the UK itself is in the group of only consultative votes. The remaining cases are spread around rather unsystematically. Furthermore, the case of Liechtenstein is unique, as the sovereignty in the country rests with the Prince of Liechtenstein and the people. This means effectively that decisions taken by referendum are generally not binding unless the Prince gives his consent to the decision taken. This formal veto power over decisions taken by the people, which has been central in many debates about the constitution in the country (Marxer, 2018, p. 301–306), leads to a decision function score of 0 points. In addition, Bulgaria deviates from the common regulations, as the turnout quorum of the citizen initiative and the authority referendum there relate to the latest parliamentary election. In the 2023 National election in Bulgaria, the turnout was 40.6% of the electorate,13 which serves as a reference here.

The results show a mainly strong decision function of direct democracy with unrestricted decision power in a third of the countries, partly limited decision-making in 60% of the countries and non-binding decisions in only a small fraction of countries. It seems that once decision-making per referendum is installed, it is invested with real decision power. Yet at this point, there is no systematic pattern evolving behind the distribution of countries. Obviously, there are differences in the effectiveness of the different channels. The highest average decision function score of 0.86 points belongs to the veto initiative, followed by the veto referendum with 0.84 points, and the mandatory referendum with 0.82 points. The average decision function score of all citizen initiatives is only at 0.75 points, but the by far lowest score belongs to the authority referendum (0.58 points). The more channels available in a political system, the higher the final decision function country score, which is a mixture of the different channels and potentially lower.

After looking at the three functions separately, we now come to the overall picture of the general system function of direct democracy. The average system function of direct democracy score of all 103 countries is at 0.45 points. As the rare presence of input instruments in the 103 countries already indicate, the input function is by far the weakest with an average of only 0.26 points. The average scores of the exit function and the decision function are 0.39 points and 0.70 points, respectively. This means that it is by far more difficult to insert political input into the two decision-making processes than to have decisions diverted out of the parliamentary system to the referendum. However, the exit function restricts the right to divert issues out mainly to political authorities and the constitution, whereas a broad dispersion of exit channels is rare.

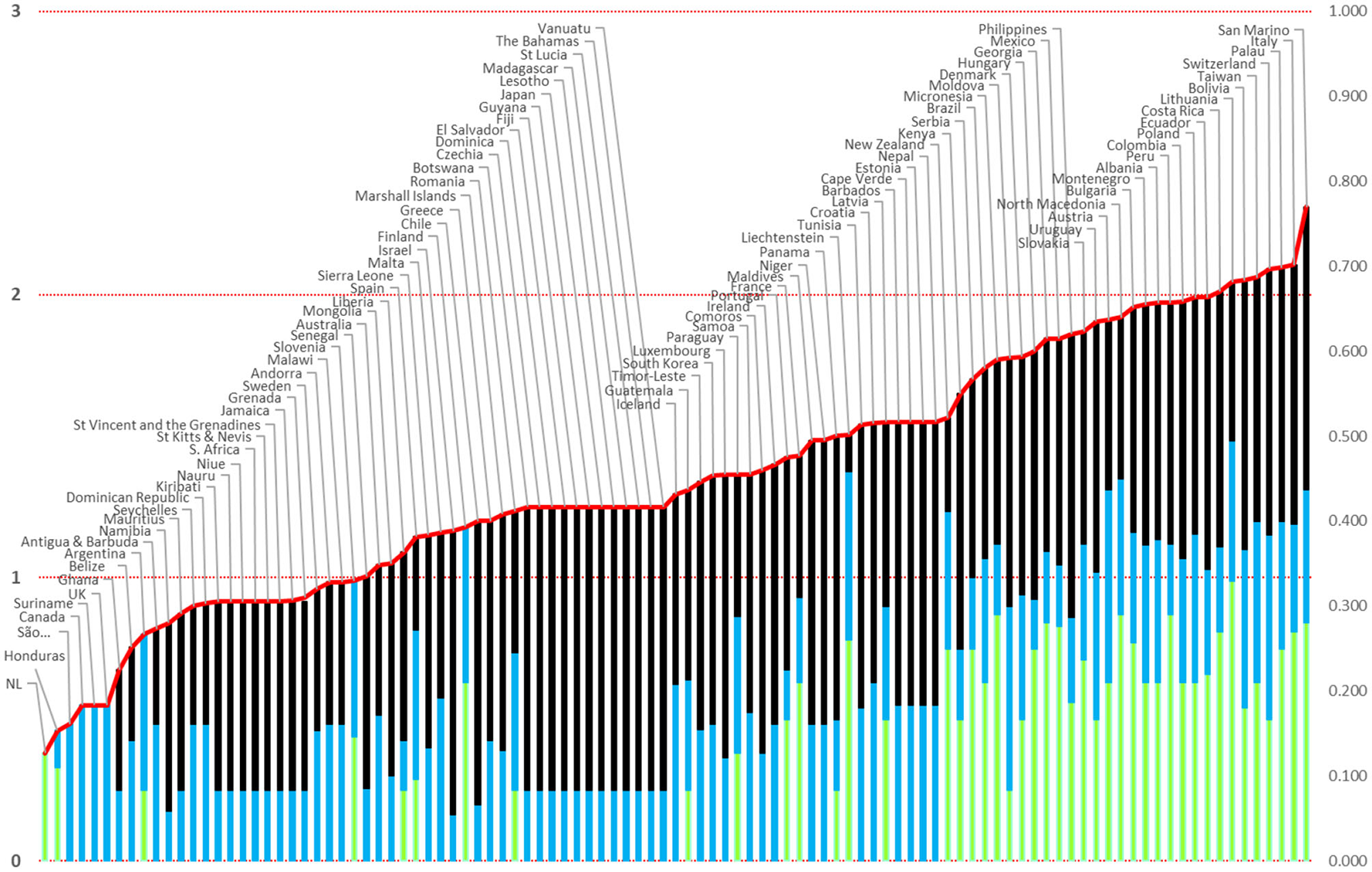

When looking at the final system function of direct democracy ranking in Figure 5, we can identify three main groups of countries. The first group is those 40 countries with all three system functions of direct democracy operating. These countries feature the “whole package”. In these countries, direct democracy can be said to have a strong or stronger systemic function. This applies to the top 30 countries in the ranking. At the top are San Marino (0.77 points), Italy (0.70 points), Palau and Switzerland (both 0.69 points), and Taiwan with 0.68 points. However, there are also exceptions like Liberia as the country with the lowest rank (no. 74) but still, all three functions are in operation. In Liberia, we find a weak agenda initiative, an authority referendum with only one policy domain, and high requirements for effectiveness.

Figure 5

Added scores of the input function (light green), exit function (blue), and decision function (black) per country (left axis) and overall system function score of direct democracy (right axis).

In the second group are countries where the decision-making function is very strong (since votes are mainly binding), but the input function is missing and the exit function is rather weak. This is particularly clear in Figure 5 for a middle block of countries starting in the ranking with Nepal. The strong decision-making power of voting is counteracted by the weakness of the other two functions. A large proportion of these are cases in which there is only an authority referendum as a channel, but this channel has practically no restrictions on content. Examples are the countries between Vanuatu and Botswana or Malawi and Namibia. This constellation repeats what has been observed before in the context of the exit function. In these cases, direct democracy rather serves the concentration of power (in the hands of the political authorities) than the division of power.

The third group is composed of those five countries at the bottom of the ranking with only one function operation. These are the Netherlands (0.12 points), São Tomé and Príncipe (0.16 points), and Canada, Suriname, and the UK all with 0.18 points. The Netherlands only features a weak input function into the parliamentary system with an agenda initiative, whereas Suriname or Canada only features a very weak exit function, but scores 0 points in the other functions due to the missing input channels and the non-binding voting results. At the bottom of the ranking, direct democracy plays only a marginal role in the political system, when votes are generally non-binding, or like in the Netherlands, even missing.14

5 Conclusion

The background of the present study is the transformation of contemporary democracy to more hybrid forms, combining representative elements with deliberative or—as in our case—direct-democratic elements. What functions does direct democracy provide and how common are they?

We introduced a new way of measuring the institutional constructions of instruments of direct democracy in a ranking with three separate functions. These functions can be positioned within the classic understanding of political systems and the policy cycle of politics. Accordingly, instruments of direct democracy offer a way of channeling political input into the two main institutions of political decision-making: the parliamentary arena and the referendum arena (if present). Second, instruments of direct democracy offer the possibility to suspend the logics of parliamentary decision-making and to divert issues out toward the referendum as an alternative decision-making arena. Third, instruments of direct democracy offer the possibility to take decisions on issues of political contestation and end political processes (not necessarily controversy). The last function is the most obvious function of direct democracy.

The provided approach is supposed to allow researchers to capture the state of direct democracy in democratic systems in one country, in many countries, in the past, present, and future. In the future, it will be interesting to observe how the functions develop over time. One of the advantages of the proposed concept is that it does not run the danger of (major) normative bias, usually discussed in the field of direct democracy. The reason is that we measure the institutional presence of three different functions, and the input and exit functions are treated as equal functions here. Even though the decision-making function represents the conditio sine non qua, there is no hierarchy in the functions of direct democracy. In previous versions of this study, we were focused on the dualism of input and decision function only and inevitably came to the usual point where the bottom-up instruments score better in the input function than the top-down instruments, running the risk of tautology. With the clear separation in distinct functions, we do not compare oranges with apples but are able to capture the entire spectrum of functions of direct democracy, including the agenda initiative as an instrument. However, it must be said again that the results on the system functions of direct democracy do not automatically mean that there actually have been referendums.

One of the challenging tasks in the future will be to explore the causal background of the system functions of direct democracy. It has already become somewhat apparent that the past as a colony in the British Empire could play a role in shaping direct democracy in political systems. Beyond that, however, no patterns or backgrounds could be identified at this point. For now, the main result is, that direct democracy around the world is far away from a standardized design. Within the functions, we find major differences between the countries. The input and exit functions are rather unbalanced in their dynamics. The exit function shows a tendency to strengthen the concentration of power, whereas the input function rarely allows for access to both decision-making arenas. However, once issues reach the referendum, the impact is often strong and only a small minority of states conduct referendums without any formal consequences. One may say that the power of the system function of direct democracy is concentrated at the wrong end of the process. In other words, to put it in a picture, having the most precise gun with an unprecedented range is futile if there is no ammunition to use.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: www.direct-democracy-navigator.org.

Author contributions

E-CH and CF contributed to the intellectual development of the main ideas of this manuscript equally. The structure was drafted by E-CH. E-CH led on the writing and CF reviewed and significantly edited. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^ www.direct-democracy-navigator.org

2.^ Until now, it has been a rather laborious business to make the diversity of direct democracy visible in bundled overviews, given the complexity of the issue. Accordingly, only few such overviews exist, for example Altman (2011, p. 49–54). One recent example is Morel's overview “Types of referendums: Provisions and practice at the national level worldwide” (Morel, 2018). Here Morel not only works out a typology of instruments of direct democracy but also offers a valuable overview of their presence and use worldwide.

3.^ Countries and number of instruments of direct democracy in parentheses: Albania (7), Andorra(2), Antigua and Barbuda (2), Argentina (3), Australia (4), Austria (5), Barbados (1), Belize (3), Bolivia (10), Botswana (1), Brazil (4), Bulgaria (4), Canada (1), Cape Verde (1), Chile (1), Colombia (5), Comoros (1), Costa Rica (3), Croatia (3), Czechia (1), Denmark (5), Dominica (1), Dominican Republic (2), Ecuador (9), El Salvador (1), Estonia (3), Federated States of Micronesia (4), Fiji (1), Finland (2), France (5), Georgia (3), Ghana (1), Greece (2), Grenada (1), Guatemala (4), Guyana (1), Honduras (2), Hungary (3), Iceland (3), Ireland (2), Israel (1), Italy (4), Jamaica (1), Japan (1), Kenya (2), Kiribati (1), Latvia (5), Lesotho (1), Liberia (2), Liechtenstein (8), Lithuania (6), Luxembourg (2), Madagascar (1), Malawi (2), Maldives (2), Malta (3), Marshall Islands (3), Mauritius (1), Mexico (3), Moldova (3), Mongolia (2), Montenegro (3), Namibia (1), Nauru (1), Nepal (1), Netherlands (1), New Zealand (3), Niger (2), Niue (1), North Macedonia (5), Palau (7), Panama (4), Paraguay (3), Peru (3), Philippines (5), Poland (4), Portugal (2), Romania (4), Samoa (1), San Marino (6), São Tomé and Príncipe (1), Senegal (2), Serbia (4), Seychelles (1), Sierra Leone (2), Slovakia (3), Slovenia (5), South Africa (1), South Korea (2), Spain (4), St Kitts & Nevis (1), St Lucia (1), St Vincent and the Grenadines (1), Suriname (1), Sweden (2), Switzerland (4), Taiwan (4), The Bahamas (1), Timor-Leste (2), Tunisia (2), UK (1), Uruguay (3), and Vanuatu (1).

4.^ It should be noted that, in the case of Liechtenstein, not all relevant instruments could be included. There are four bottom-up instruments that are triggered by community meetings (“Gemeindebegehren”) with no prescribed quorum of citizen participation. See Marxer (2018) for more details.

6.^ Deadline is 1 November 2022.

7.^ The dataset itself has been compiled since the year 2010 and has been constantly cross-checked by international experts, for example, on the occasion of the annual Global Forum on Modern Direct Democracy organized by the Swiss Democracy Foundation and Democracy International. See https://www.democracy.community/global-forum/2022-global-forum-modern-direct-democracy (accessed 18.09.2023).

8.^ Institutional structure includes the republican form of government; the internal organization or regulation of representative bodies and the judicial power, electoral law, judicial, or administrative procedures.

9.^ State territory includes the establishment of new municipalities, the merger, modification, incorporation and dissolution of municipalities.

10.^ See https://www.sabor.hr/sites/default/files/uploads/inline-files/CONSTITUTION_CROATIA.pdf.

11.^ See the Bolivian Referendum Law online at: https://reformaspoliticas.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Ley_N_026.pdf.

12.^ See https://direct-democracy-navigator.org/legal-design-filter/detail/?ldid=1270.

13.^ See data at: https://data.ipu.org/node/26/elections?chamber_id=13351 (accessed: 18.09.2023).

14.^ A national level veto initiative was abolished in the Netherlands after only three years of existence, making the Netherlands the first democratic country to abolish its national referendum legislation (van der Meer et al., 2022).

References

1

Aguiar-Conraria L. Magalhães P. C. (2010). Referendum design, quorum rules and turnout. Public Choice144, 63–81. 10.1007/s11127-009-9504-1

2

Aguiar-Conraria L. Magalhães P. C. Vanberg C. A. (2016). Experimental evidence that quorum rules discourage turnout and promote election boycotts. Exp. Econ.19, 886–909. 10.1007/s10683-015-9473-9

3

Altman D. (2011). Direct Democracy Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

4

Altman D. (2016). The potential of direct democracy: a global measure (1900–2014). Soc. Indicators Res.133, 1207–1227. 10.1007/s11205-016-1408-0

5

Altman D. Sánchez C. T. (2020). Citizens at the polls. Direct democracy in the world, 2020. Taiwan J. Democ.17, 27–48.

6

Cheneval F. El-Wakil A. (2018). The institutional design of referendums: bottom-up and binding. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 24, 294–304. 10.1111/spsr.12319

7

Easton D. (1965). A Systems Analysis of Political Life.John Wiley & Sons: Chicago/London.

8

Frey B. S. Stutzer A. (2000). Happiness, economy and institutions. Economic.10.2139/ssrn.203211

9

Herrera H. Mattozzi A. (2010). Quorum and turnout in referenda. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 8, 838–871. 10.1111/j.1542-4774.2010.tb00542.x

10

Hornig E. C. (2011a). Die Parteiendominanz direkter Demokratie in Westeuropa. Nomos: Baden-Baden.

11

Hornig E. C. (2011b). Direkte Demokratie und Parteienwettbewerb – Überlegungen zu einem obligatorischen Referendum als Blockadelöser auf Bundesebene. Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen3, 475–492. 10.5771/0340-1758-2011-3-475

12

Hornig E. C. (2021). “Direkte Demokratie in Italien – zwischen Reform und Beharrung,” in Direkte Demokratie, eds. Heußer, H., Pautsch, A., and Wittreck, F. Stuttgart: Richard Boorberg 471–497.

13

International IDEA (2008). Direct Democracy. Stockholm: The International IDEA Handbook.

14

Jung S. (2001). Die Logik direkter Demokratie. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

15

Leemann L. Stadelmann-Steffen I. (2022). Satisfaction with democracy: when government by the people brings electoral losers and winners together. Comp. Polit. Stud. 1, 93–121. 10.1177/00104140211024302

16

Marxer W. (2018). Direkte Demokratie in Liechtenstein. Entwicklung, Regelungen, Praxis, Liechtenstein Politische Schriften Bd. 60. Bendern: Verlag der Liechtensteinischen Akademischen Gesellschaft.

17

Merkel W. Ritzi C. (2017). “Theorie und Vergleich,” in Die Legitimität direkter Demokratie, eds. MerkelW.RitziC.Cham: Springer, 9–48.

18

Moeckli D. (2021). “Introduction to The Legal Limits of Direct Democracy,” in The Legal Limits of Direct Democracy. A Comparative Analysis of Referendums and Initiatives across Europe, eds. MoeckliD.Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 1–9.

19

Moeckli S. (1994). Nove democrazie a confronto, in: Democrazie e Referendum, eds. Caciagli, M., and Uleri, P. V. Bari: Laterza.

20

Morel L. (2007). The rise of “politically obligatory” referendums: the 2005 French referendum in comparative perspective. West Eur. Polit.30, 1041–1067. 10.1080/01402380701617449

21

Morel L. (2018). “Types of referendums, provisions and practice at the national level,” in Handbook to Referendums and Direct Democracy, eds. Morel, L., and Qvortru, M. London: Routledge, 27–59.

22

Papadopoulos Y. (1995). Analysis of functions and dysfunctions of direct democracy: the top-down and bottom-up perspective. Polit. Soc.23, 421–448. 10.1177/0032329295023004002

23

Qvortrup M. (2017). The rise of referendums: demystifying direct democracy. J. Democ. 28, 141–152. 10.1353/jod.2017.0052

24

Qvortrup M. (2018). “The history of referendums and direct democracy,” in Handbook to Referendums and Direct Democracy, eds. Morel, L., and QvortrupM.London: Routledge, 11–26.

25

Rochat P. Milic T. Braun Binder N. (2022). “Die Volksinitiative: Nur ein weiteres parlamentarisches Instrument?,” in Direkte Demokratie in der Schweiz. Neue Erkenntnisse aus der Abstimmungsforschung, eds. Bühlmann, M., and Schaub, H. Zurich: Seismo, 23–42.

26

Schaub H. Frick K. (2022). “Die Unterschriftensammlung: Ein geeigneter Prüfstein für die Relevanz von Initiativen und Referenden?,” in Direkte Demokratie in der Schweiz. Neue Erkenntnisse aus der Abstimmungsforschung, eds. Bühlmann, M., and Schaub, H. Zurich: Seismo 43–68.

27

Serdült U. Welp Y. (2012). Direct democracy upside down. Taiwan J. Democ. 8, 69–92. 10.5167/uzh-98412

28

Silagadze N. Gherghina S. (2020). Referendum policies across political systems. Polit. Quart.1, 182–191. 10.1111/1467-923X.12790

29

Smith G. (1976). The functional properties of the Referendum. Eur. J. Polit. Res.4, 1–23. 10.1111/j.1475-6765.1976.tb00787.x

30

Stutzer A. Frey B. S. (2003). “Institutions matter for procedural utility: an economic study of the impact of political participation possibilities,” in Economic Welfare, International Business and Global Institutional Change, eds. R. Mudambi, P. Navarra, and G. Sobbrio. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 81–99.

31

Uleri P. V. (2002). On referendum voting in Italy: YES, NO or non-vote? How Italian parties learned to control referendums. Eur. J. Polit. Res.6, 863–883. 10.1111/1475-6765.t01-1-00036

32

van der Meer T. W. G. an dWagenaar C. C. L. Jacobs K. (2022). The rise and fall of the Dutch referendum law (2015–2018). initiation, use, and abolition of the corrective, citizen-initiated, and non-binding referendum. Acta Politica57, 96–116. 10.1057/s41269-020-00175-3

33

Vatter A. (2000). Consensus and direct democracy: conceptual and empirical linkages. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 38, 171–192. 10.1111/1475-6765.00531

34

Vatter A. (2009). Lijphart expanded: three dimensions of democracy in advanced OECD countries?Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1, 125–154. 10.1017/S1755773909000071

Summary

Keywords

direct democracy, referendum, political systems, worldwide, democracy

Citation

Hornig E-C and Frommelt C (2024) The system functions of direct democracy - a ranking of 103 countries in the world. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1146307. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1146307

Received

17 January 2023

Accepted

14 December 2023

Published

24 April 2024

Volume

5 - 2023

Edited by

Anastasia Obydenkova, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), Spain

Reviewed by

Arjan Schakel, University of Bergen, Norway

Davide Morisi, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Hornig and Frommelt.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eike-Christian Hornig Eike-Christian.Hornig@Liechtenstein-Institut.li

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.