94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 22 June 2023

Sec. Dynamics of Migration and (Im)Mobility

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1145634

This article is part of the Research TopicIdeational Aspects of Migration and Integration Policy, Politics and GovernanceView all 6 articles

In this paper, I try to better understand the intersection between “integration” in legal terms, and how long-term resident “non-citizens” and migrants from the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) situate themselves in narratives of belonging vis a vis the normative power structure that constitutes the Swiss body politique. More specifically, how do labor and forced migrants from former Yugoslavia negotiate the shifting understanding of “integration” in Switzerland in legal and social terms? Former Yugoslavs constitute not only a comparatively large number of “non-citizens” in Switzerland, but individuals from-and-with-connections to this community also embody numerous labels and categories of migrant that statistical databases, the media, and legal practices attach to them since the 1970s. Key findings in this paper illustrate a two-tiered narrative: “non-citizens” seemed to have maintain(ed) their pursuit of not attracting attention to their persona—a strategy that allowed individuals to disappear within the larger society. Ensuing Europeanization processes, coupled with the Wars of Yugoslav Succession during the 1990s, however, brought to the fore “a politics of rupture” that called into question othering processes, and the seemingly tightening sociolegal basis of belonging to the Swiss body politique. Hitherto examined data suggests that interlocutors pursue a “positive essentialist frame” to counter exclusionary narratives “non-citizens” experience to postulate “rights claims”. Interviewees, in other words, activate diaspora connections and networks to support and aid each other when legal and socio-political questions arise, but also to actively influence the political and legal landscape in Switzerland.

Switzerland and the Western Balkans are inextricably linked by way of labor migration starting with a slow trickle of dentists in the 1960s, followed by active labor recruitment in the 1970s, family unification, and asylum during the 1980s and 1990s, respectively. Relying heavily on Italian labor migration as a pre-WWI continuation, Switzerland lost some of its appeal compared to other European Community (EC) states during the 1960s. Because Italian labor migrants enjoyed broader access to political and civic rights in EC member states, especially in Germany, Switzerland not only signed a revised labor agreement with Italy that allowed family unification in 1964, but the country also diversified its geographic recruitment strategy to include Turkey, Spain, Portugal, and SFRY as illustrated in Figure 1. By the mid-1990s, individuals from SFRY comprised the second largest migrant community in Switzerland.

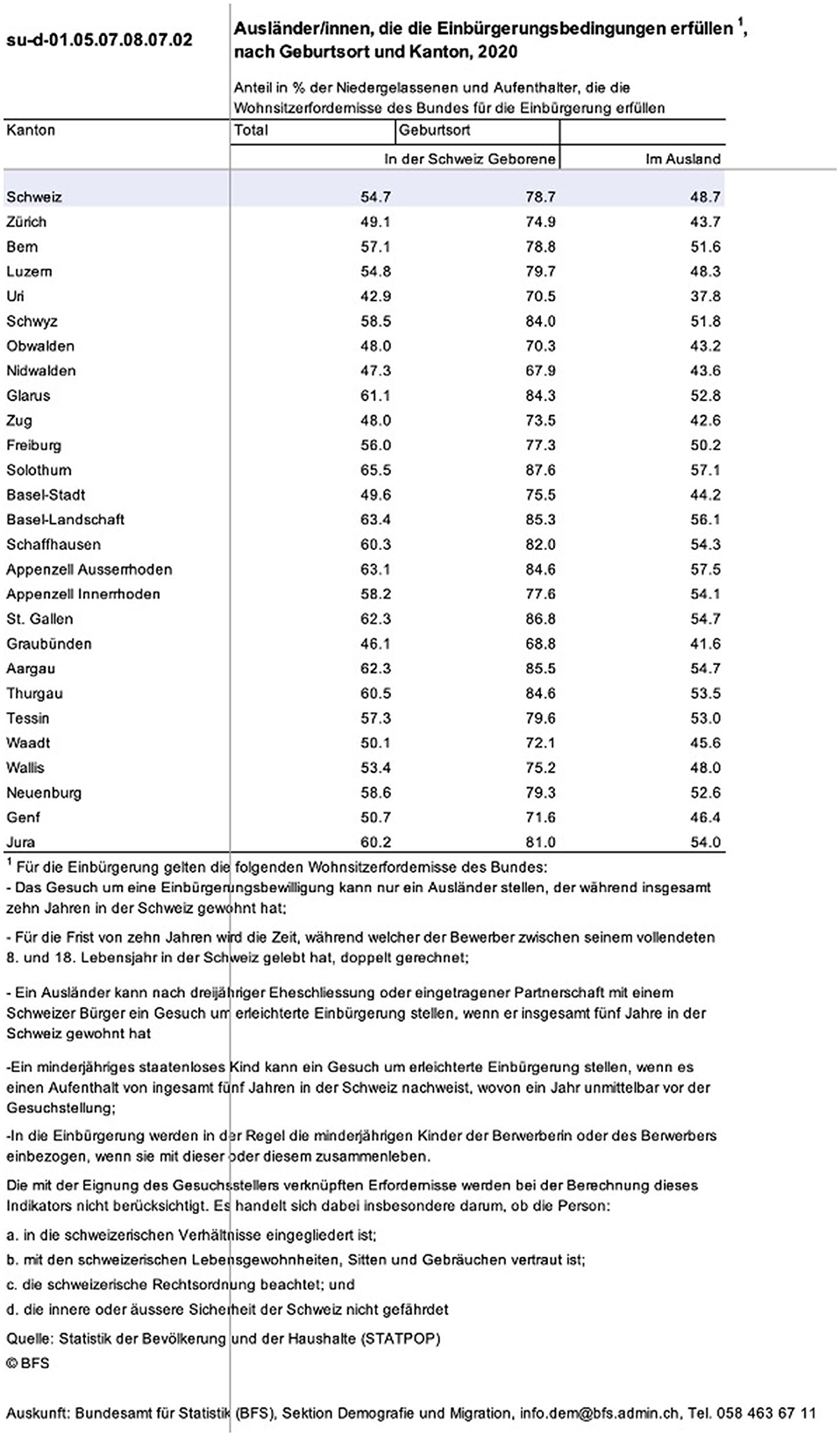

Figure 1. Foreigners who meet the naturalization requirements, by place of birth and canton (Bundesamt für Statistik., 2021).

The twenty-year timeframe between 1970 and 90 is a caesura continuing to shape the Swiss migration architecture for three reasons. First, as illustrated in Figure 1, the number of (labor) migrants increases substantially, reaching the one million mark in the early 70s. As a result, conservative elements, above all James Schwarzenbach, member of the National Action party (1961), initiated a radical initiative by which the proportion of foreigners in Switzerland should not exceed 10 percent of the overall population (see Eidgenössische Volksinitiative “Ueberfremdung”). In practice, this would have meant that ca. 300,000 workers would have had to leave Switzerland overnight. The referendum was put to the vote on June 7, 1970, with a record-breaking turnout of almost 75%. Fifty four% of those voting rejected the initiative, 46 percent voted in favor. The so-called Schwarzenbach initiative is since understood as a blueprint about how to instrumentalize and/or mobilize anti-foreigner and xenophobic sentiments in Switzerland—a blueprint that came to fruition with the Ausschaffungsinitiative (Deportation Initiative) in 2010. The popular initiative came to a vote on 28 November 2010 with a direct counter-proposal and was approved by a majority of 52.9 percent of those voting thus approving the expulsion of “foreigners” lawfully present in Switzerland based on offenses against life and limb, welfare abuse, drug trafficking, and burglary (see Volksinitiative 'für die Ausschaffung krimineller Ausländer, 2010). The initiative serves as the basis for contemporary migration laws pertaining to third-country nationals, and the constant need to control, or rather obstruct access to the Swiss body politique.

Second, an important layer of complexity is added regarding the outbreak of the Yugoslav Wars of Succession. During the 1990s, labor migrants either united with family members through the family unification scheme, while others fled SFRY on their own to seek asylum in Switzerland and elsewhere in the world, though oftentimes arrived in pre-existing networks of acquaintances. The Yugoslav migrant community is therefore heterogenous, and moreover illustrates the “legal fiction” underlying the labor migrant/refugee binary (Hamlin, 2021; Abdelaaty and Hamlin, 2022).

Third, the consolidation and harmonization of the EC, especially the Free Movement of Persons Agreement (FMPA) signed in 1999 and enforced in 2002, lead to a fundamental recategorization of who is othered as “foreign”. While Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish labor migrants turned into Europeans, Yugoslavs were ethnisized, and turned into so-called third-country national non-Europeans. The discourse surrounding the former labor community, in other words, assumed an “ethnic” character, restricting mobility patterns as well as access to the labor market. Since then, a combination of institutional practices, social habits, and preconceived notions create structural barriers that inhibit equal access to upward social mobility. Migrants from the Western Balkans (and Turkey), including their children, reach lower educational levels compared to their Swiss-born peers as well as highly educated migrants from western/northern Europe. Perhaps not surprisingly, individuals from this region rarely reach academic or highly ranked executive positions. Recent studies further indicate people of Western Balkan origin face substantial penalties in the job market (Hangartner et al., 2021) as well as when applying for citizenship (Hainmueller and Hangartner, 2013).

The transformation of Yugoslav labor migrants into third-country non-Europeans materialized against the backdrop of two interrelated developments. While EC member states consolidated the idea of who is European, individuals in SFRY lived through the first full-blown war on European soil since WWII. At the same time, Switzerland harmonized its migration governance in accordance to fit that of Europe. In practice, this meant a reduction of workers from third countries, and an intended increase of highly skilled employees—preferably from EC states. However, because the Swiss are inextricably linked with the Western Balkans, labor migrants often served as brokers through which asylum seekers found safety in Switzerland by way of family unification. Immigration to Switzerland from the Balkans thus increased just when Switzerland sought to reduce the number of labor migrants, i.e., non-European third country nationals. Consequently, integration becomes an instrument by which to discipline migrants in Switzerland, but first and foremost individuals from third countries. As such, integrationism—the need to restrain the movement and regulate the behavior of immigrants—is contextualized within Europeanization processes against the backdrop of the Wars of Yugoslav Succession. Seen from this relational perspective, the focus of this paper lies on how migrants experienced the transformation of the Swiss migration architecture without rendering these individuals as objects of the study.

Christian Joppke and Antje Ellermann ruminated the above questions in their respective articles “Why Liberal States Accept Unwanted Immigrants”, and “When [Can] Liberal States (Can) Avoid Unwanted Immigration” (Joppke, 1998; Ellermann, 2013). Switzerland pursued a policy of segmented labor policy and, on the one hand, needed an ever-increasing workforce to build up the infrastructure needed. At the same time, a segment of citizens with voting rights felt uneasy about the ever-growing foreign population. The steady increase of labor migrants, according to Joppke, is comprehensible when viewed from the perspective of “self-limited sovereignty”. Conceptualized as such, states follow the logic of client politics as well as moral obligations (Joppke, 1998, p. 292). Accordingly, migrants were invited to work in Switzerland due to the economic boom and retained because of moral obligations. Liberal states are consequently, according to Joppke, unable to curb immigration to zero. Ellermann argues the opposite, namely from the perspective of “elite-insulation”, and “policy-learning” (Ellermann, 2021). Switzerland, according to this scenario, summoned labor migrants knowing full well about the need to handle entry permits restrictive based on historical, pre-WWI experiences with Italian labor migrants. Swiss legislative elites are, additionally, politically exposed to popular initiatives, and therefore prone to be influenced by them (Ellermann, 2013, p. 515–516). The latent and manifest fear of Überfremdung (overforeignization), respectively, serves as an instructive illustration. Building on both Joppke and Ellermann, this study reformulates their question to ask who is considered foreign in the first place.

Statistical calculations about non-citizen denizens residing in Switzerland are instructive, as illustrated in Figure 1. In total, 54.7% of two million people1 considered foreign residents theoretically fulfill the naturalization criteria, but “choose” not to initiate the naturalization process due to high costs, and/or stringent integration criteria, of which 78.7% were born in Switzerland. An examination from the perspective of EU and non-EU members allows for a better understanding about third-country nationals to which the Yugoslav community was relegated during the 1990s. Of the roughly 400,000 non-citizens holding a so-called third country status, 74.4% theoretically fulfill the formal naturalization criteria, 91.1% of which were born in Switzerland. Previous research presented findings about how Swiss naturalization practices function along the lines of cultural assimilation, especially when it comes to culturalized values (e.g., Achermann, 2013; Burri et al., 2014; Lüthi and Skenderovic, 2019; Dahinden and Stefan, 2022; D'Amato, 2022; Stefan Manser-Egli this issue, Dahinden and Stefan, 2022). One is therefore left wondering if the persistently high immigration numbers pertaining to Switzerland are “a home-made statistical one”, as I have argued elsewhere (King-Savic, 2022, reflecting on Bade, 2003, p. 244). Seen from this vantagepoint, Switzerland has a substantial democratic deficit.

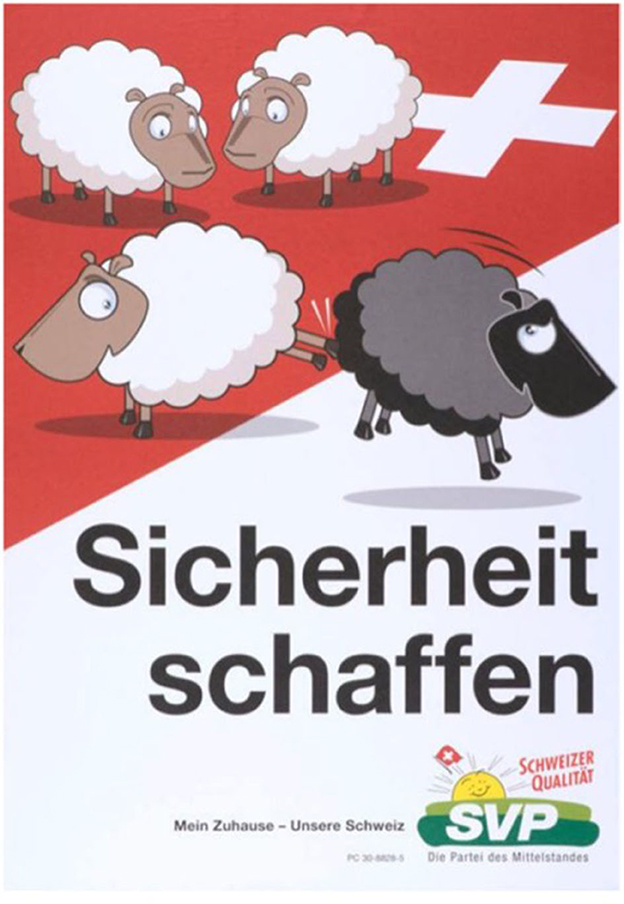

Three interrelated phenomena are notable. First, Swiss migration law is guided by an intersubjective, normative conversation about who should be Swiss. Ostensibly, people “from the Balkans” are not. Figure 2 revealing in this context.

Figure 2. Creating Safety. My Home–our Switzerland (2007) Designer: Goal AG für Werbung und Public Relations, Dübendorf, CH (gegründet 1994). Client: Schweizerische Volkspartei, SVP, Bern, CH (gegründet 1971), accessed at Museum of Design Zurich, Archive of the Zurich University of the Arts (accessed April 28, 2023).

Figure 3 illustrates an individual, purportedly a rapist of obvious Slavic—most likely Western Balkan background. Ivan S., unshaven, sporting a thick necklace and white undershirt can neither be trusted, nor is he likely able to integrate. As such, criminal individuals such as Ivan S. are, quite literally to be kicked out of Switzerland to uphold a safe “home”. A home were people of color, and the likes of Ivan S. do not belong. Judging from these xenophobic depictions, it seems that the cultural difference between the Swiss and people from the Balkans and fellow third country nationals appears too large to surpass. The law is thus based on a conservative, homogenizing vision of a morally upright, genuine Swiss person, to frame it in Mikhail Bakhtin's words, to create “the other” in its image (Holquist, 2002, p. 27). In so doing, the law mirrors political processes set in motion during the 1970s. Such othering processes, or labeling specific groups as culturally distant, therefore mirrors larger (socio-) political processes at work. Second, migrants actively “consented” to belong to the Swiss body politique, unlike most citizens who received their passports by way of the jus sanguinis principle (Song, 2019, p. 9). And yet, individuals are considered “strangers” before the law even if they were born in Switzerland, and/or considered Swiss “on paper only” upon receiving Swiss citizenship. Strangers, borrowing from Isin, “are those subjects who, while accepted into citizenship, are still considered strangers in the sense that they have not yet fulfilled requirements to act as citizens (Isin, 2020, p. 503). As such, the central question surrounds the understanding “peoplehood” (Bauböck, 2010). Reflecting on Rogers Smith, Rainer Bauböck states that:

[P]olitical legitimacy in every polity is generated through “stories of peoplehood” that include not only narratives about economic advantage and political power, but also “ethically constitutive stories” about collective identities and belonging. This is true not only for independent states, but also for various types of nation-state polities. We therefore need to trace the public discourses as well that construct (transnational) citizenship not merely as legal statuses and rights, but also as a significant way of belonging to a political community (Bauböck, 2010, p. 299).

Figure 3. Ivan S., Rapist – soon to be Swiss? Ivan S., Vergewaltiger - bald Schweizer? Gegenentwurf nein - Ausschaffungsinitiative ja - Überparteiliches Komitee Gegenentwurf Nein - www.kriminelle-nein.ch, 2010. Designer Goal AG für Werbung und Public Relations, Dübendorf, CH (gegründet 1994). Client Überparteiliches Komitee “Gegenentwurf Nein”, Bern, CH. Accessed at the Museum of Design Zurich, Archive of the Zurich University of the Arts (accessed April 28, 2023).

“Peoplehood” as postulated by the law, more closely coincides with an understanding of membership that is based on “political power” and a “shared national identity” (as defined by Smith, 2015: 69; Song, 2019, p. 9; see also Favell's discussion on the Weberian nation-building model, 2022). Interlocutors, on the other hand, invoke what Sarah Song coined “membership based on participation in shared institutions” (Song, 2019, p. 9, 53).

All things considered, the way in which the above illustrated phenomena come together during the 1990s present a considerable “democratic legitimacy gap”, to frame it in the words of Ayelet Shachar, who stated:

A prime example is the German treatment of so-called Gastarbeiter (guest workers) and their offspring who gained a right to stay but not to become citizens or voters that plagued the country for years until the reform of Germany's citizenship law in 2000 (Shachar, 2009, p. 136–137).

Switzerland, borrowing from Shachar, has a considerable “democratic legitimacy gap” considering the above statistics. Interlocutors know this, and actively push the boundaries by way of building political mobilization through, in part, diaspora networks to make visible their “enactments of rights claims” (Isin, 2020, p. 505) and influence the sociopolitical and legal landscape in Switzerland. To date findings suggest that participants and co-creators of this study, perhaps unwittingly, “pursue a positive essentialism” frame to bring to the fore experienced inequalities (Spivak, 1988). In doing so, interlocutors considerably contribute to their own “de-migrantization” by, however, drawing on their experiences with migration (Phillips, 2010; Dahinden, 2016, p. 2212, reflecting on Fraser and Honneth, 2003).

Heeding Janine Dahinden who called for a de-migrantization of migration and integration studies, I ask if, and if so, to what extent individuals with a so-called migration-for-or-background/migration-biography (Jain, 2021, p. 362) themselves “pursue a positivist essentialism” strategy to counter the three phenomena elucidated above, including, first, the socio-political and legal processes of othering people with a third-country status and specifically people from former SFRY. Second, hitherto examined data suggests that while individuals with a migration biography linked to the former SFRY build networks to aid each other, they do so based on an “ethics of universal membership principle” (Song, 2019, p. 190). Third, knowing about the “legal fiction” pertaining to the migrant/refugee binary, interlocutors with a migration biography linked with the former SFRY lobby to realize “what the state owes to those who perform the role of the citizen, regardless of their documented status” (Isin, 2020, p. 510–511). Focusing on individuals from former SFRY, one can elicit the ways in which jurisdictional processes contribute to the making of ethnic and national communities, but also, importantly, how individuals perform these roles strategically to practice “rights claims” to the Swiss body politique.

This paper is based on a grounded theory approach, a controlled process of data collection during which I moved in and out of the field to evaluate, test, and substantialize findings to develop a theoretical framework (Glaser and Strauss, 2008; Brunnbauer, 2019). Methods include ethnographic research and repeated in-depth biographical and situational interviews with individuals to date since 2019. In all, I recorded repeated, semi-structured interviews with 19 males, and 22 females, all of whom had arrived in Switzerland between the 1960s and late 1990s. I therefore conducted interviews and participant observation in multiple stages. Moving in and out of field allowed for a validation and substantialising of findings. Controlled field activities thus ensured that findings were “independent of accidental circumstances of the research” (Kirk and Miller, 1986, p. 11, 20). As a routine, I spend much of my time meeting with people informally prior to setting up open-ended, biographical interviews. I observed daily activities, engaged in informal and casual conversations, and continued to interview a range of residents who had migrated to Switzerland between the 1970s and 90s. I recorded all but one open ended autobiographical interview, in contrast to casual conversations, which were not recorded. Interviews lasted between 1 and 3 h, transcribed with F4, coded, and analyzed with Atlas.ti. Each transcription took between 5 and 7 h per one interview hour, depending on the clarity of speech, background noise, and the general speed with which interlocutors spoke. A number of these interlocutors turned into important collaborators and friends over the years. The project was approved by the Human Subjects Committee at the University St. Gallen upon assurance to keep all interviewees anonymized.

Participant observation was conducted with full knowledge of all parties during cultural gatherings including movie screenings, music venues, readings, and other third spaces (Oldenburg, 1999) such as beauty salons and online forums since 2019. To learn about how migrants experienced the transformation of the Swiss migration architecture, I approached my research as a “student-child apprentice,” to put it in Michael H. Agar's words, and sought to create a frame to build on, and integrate the knowledge of group members (Agar, 2008, p. 242–243). As such, I relied on ethnographic tools to tease out overlapping, conflicting, and subsidiary narratives about how migrants experienced the transformation of the Swiss migration architecture.

To better understand interviews, I triangulated ethnographic data with the Newsweek on Wednesday – For Our Citizens in the World (Vijesnik u Srijedu – Za Naše Gradjane u Svijetu, VUS) newspaper series, published between March 24th 1971 and December 31st 1977 according to a Discourse Historical Approach (Wodak and Meyer, 2009, DHA). Following a “socio-diagnostic critique” allowed for a comparative reconstruction and contextualization of interviews with interlocutors to illustrate the tension inherent in which labor migrants lived before the law in a Swiss, as well as a former SFRY context. On the one hand, the VUS was written by and for labor migrants. As such, individuals presumably contributed articles that were regularly published under the heading e.g., Dopis iz (letter from), or Pisma uredniku (letters to the editor). Other contributions revolved around activities organized by labor migrant social- and sports clubs. And yet, the paper also served as a representative organ of the SFRY government that instructed labor migrants about their rights, as well as expectations raised on the side of the authorities. Labor migrants, for instance, were variously described as naši ljudi (our people), naši radnici (our workers), radnici privremeno zaposleni u inozemstvo (workers temporarily employed abroad), etc. Interestingly, the term diaspora is never mentioned in the examined period between 19719 and 77. Instead, the editors and perhaps the letter writers themselves used euphemisms such as naši ljudi (our people), and naši radnici u svetu (our workers in the world), emphasizing the ostensibly temporary character inherent in this type of labor mobility. Former SFRY authorities to some extent claimed labor migrants as their own, at least during the period under examination. Due to the existing mobility regime format that was at the time still considered a Rotationsmodell (short-term recruitment model), party organs oversaw and/or variously interpreted the rights of-and-for labor migrants abroad.

My personal background was often a subject of interest and may have influenced how much and what kind of information interlocutors chose to disclose, and consequently their decision to introduce me to further informants, or not. As such, the positionality of researchers, as previously noted by Lotte Höck, influences “the type of data they gather, and the analytical perspectives they chose” (Höck, 2014, p. 105).

My upbringing was in many ways ordinary. Born to Yugoslav parents in Switzerland, we socialized with a range of people, visited the Yugoslav afterschool program, and followed both the Swiss as well as SFRY media. Like other labor migrant kids, I traveled alongside my family to SFRY during summer and winter breaks to visit, as an extended network of family and acquaintances worked on the house we were to move into after my parents finished their stint as labor migrants. These plans changed with the outbreak of the Wars of Yugoslav Succession and as did other former labor migrants at the time, my parents initiated the naturalization process during the mid-1990s. I was in my mid-teens, and wondered why I was gifted a Swiss cookbook during the initiation ceremony. Gender stereotypes aside, memory surely plays tricks on us with events going back decades. This occasion is, however un/fortunately immortalized on digitalized video recordings. The person extending the gift to me ceremoniously exclaimed that now, ‘you can learn to cook real Swiss meals'. Surely well intended on the side of the person extending the gift, I was puzzled by this statement, having been accustomed to both SFRY and Swiss food. It was only much later, 2 years into my U.S. residency, that I was learning about the tools to frame and articulate circumstances surrounding the migration-integration-citizenship triad as I embarked on my university education at the age of 27. I am still learning, mostly from interlocutors who invite me to their homes, and into their lives.

In seeking to go beyond binary reflections of belonging, I am inspired by Magdalena Nowicka and Louise Ryan who stated, “the insider-outsider dichotomy inevitably ends in the question on the meaning of group categories such as ethnicity and nationality for the design and conduct of the research” (Nowicka Magdalena and Louise Ryan, 2015, p. 2). I therefore assume “uncertainty” as a point of departure in my effort to sidestep the chance of employing a “methodological nationalist” lens (Wimmer and Glick Schiller, 2002). I do not, in other words, assume inferred commonalities based on ethnicity and/or nationality. Instead, interlocutors might relate to my being a woman, an educator, a former bar tender, or an avid hiker.

In what follows, I am merging two bodies of literature, namely aspects of the Swiss migration law and critical migration studies literature. First, I will briefly outline mobility movements between Switzerland and SFRY, including the corresponding legal frame that governed said mobility since the 1970s. This section serves the purpose of framing both the Yugoslav mobility, as well as migration and asylum legislature within a historical context. This first section is based on interviews, legal documents and interpretations, and the Wednesday News—For Our Citizens in the World (VUS) newspaper to elicit “rights claims” lodged and/or practiced in Switzerland. Second, I introduce a narrative frame surrounding Europeanization processes, as well as legislative changes during the 1990s. In this section, I rely on legal documents and interpretations, as well as interviews to better understand if, and at which point legislative processes contributed saliently to process of othering individuals belonging to the SFRY community—self ascribed or externally attributed. Third, drawing on the notion of performative citizenship by Engin Isin, I illustrate the ways in which interlocutors perform the notion of citizenship to push the boundaries of belonging to the Swiss body politique by.

An initially salient factor that contributed to the large-scale mobility from the SFRY to Switzerland is labor. Consequently, this migrant group came to be known as “Gastarbeiter” (guest workers).2 In the case of SFRY, the state regulated the outward labor migration of its citizens. Josip Broz Tito, late president of the SFRY, officially restricted the emigration of Yugoslav citizens until 1965. After 1965, the socialist leadership actively encouraged the mobility of its citizens to curb unemployment within state borders. It is instructive to recall here that full employment served as a raison d'être of a real-socialist system.3 Encouraging labor migration therefore relieved the socio-political pressures and economic shortcomings in the republic (Brunnbauer, 2019).

Once in Switzerland, labor migrants were subject to ordinances within the jurisprudence of the Residence and Settlement of Foreigners law (Aufenthalt und Niederlassung der Ausländer, ANAG) during the so-called Trente Glorieuses (thirty glorious years). Cornelia Lüthi said it perhaps more poignant: “For more than 40 years, until the introduction of the Federal Act on Foreign Nationals (Bundesgesetz über Aufenthalt und Niederlassung der Ausländer (ANAG) vom 26. März., 1931), the management of labor immigration was regulated not by law but by ordinances (BVO)” (Lüti, 2022, p. 21). Lüthy subdivides the roughly 40 years under the ANAG into three phases. The first period was heavily influenced by the 1948 recruitment agreement between Italy and Switzerland (Lüti, 2022, p. 19). It is during this phase when Swiss cantons received sovereignty over the act of issuing temporary residence permits, while the federation remained responsible concerning settlement permits. A combination of reasons lead to this split of powers between the federal government and cantons. Lüthy clarifies that cantons were, on the one hand, aware of the looming labor shortage and thus tasked to issue temporary permits under more stringent conditions (Lüti, 2022, p. 19). These included regular repatriation before years-end, as well as the prohibition to bring along family members—it is the coming into existence of the Rotationsmodell (short-term recruitment model). As such, labor migrants were not to receive permanent residency to assuage the latent fear of over-foreignization within the Swiss population (Überfremdungsängste). A further point of contention came from the political left of center wing regarding potential competition with the domestic work force and prospective wage dumping (Spescha et al., 2019, p. 50). The federal government was thus tasked with protecting the domestic workforce, and henceforth responsible for the regulation of permanent resident permits (Holenstein et al., 2018, p. 312).

The 1960s, according to Lüthy, ushered in the second phase with the by now manifest fear of over-foreignization, and the ensuing implementation of quotas. During this time, labor migrants no longer came to Switzerland exclusively from Italy, France, and Austria. Instead, they also originated from Spain, Turkey, and former Yugoslavia. Two important developments ensued simultaneously during this time. First, the short-term recruitment model was no longer considered to be cost-effective due to lost time upon continued turnover of labor migrants. Second, Switzerland lost some of its appeal as European Community (EC) members liberalized its laws pertaining to labor migrants (Holenstein et al., 2018, p. 313). Citing Federal Council message BB1 1964 II, Thomas Gees notes that Rome reprimanded Switzerland for lagging behind other EC member states regarding the social security situation of Italian labor migrants and demanded improved conditions for its compatriots (Gees, 2006, p. 121 footnote 156). At the time, Italians composed by far the largest labor migrant community with a total of 49 percent. It is safe to assume here that the Federal Council knew full well about its reliance on this workforce due to the sustaining economic boom, as well as the declining appeal for prospective workers from other EC member states. As a result of this pressure, Switzerland signed a new general agreement with Italy in 1964. The most important concessions included child allowances to migrant workers engaged in the agricultural sector, the prospect of permanent residency upon 45 months of service within 5 years (Spescha et al., 2019, p. 56), and thus inclusion into the unemployment insurance scheme, as well as permission for family unification following an 18-month incubation period (Gees, 2006, p. 121–129, see also Ellermann, 2013, 2021).

In anticipation of the Schwarzenbach Initiative, the Federation introduced global quotas to bring down the number of labor migrants allowed to pursue work in Switzerland. This, according to Lüthy, heralded the third and last period under the ANAG (Lüti, 2022, p. 19). Important to note here is that by that time, according to Spescha et al., the first generation of secondos and secondas had already been born in Switzerland or joined their working parents by way of the family unification scheme (Spescha et al., 2019, p. 51). A variegated combination of political and social factors in Yugoslavia as well as in Switzerland therefore shaped the mobility regime of migrants from the SFRY from the outset. Whereas individuals arrived as labor-migrants since the 1950s, applications for the purpose of family reunification and conversions from seasonal to permanent residence permits increased since the 1980s. The recruitment ban of 1973/74 contributed significantly to this development as laborers feared injunctions against their re-entry to Switzerland. Labor migrants, in other words, turned into permanent residents starting in the 1980s, in part e.g., because of political unrest and socioeconomic shortcomings in SFRY (Brunnbauer, 2019), and/or because their children were born and had begun their schooling in Switzerland.

While abroad, labor migrants were, according to Mišo Kapetanović, discouraged from engaging politically in receiving states (Kapetanović, 2022, reflecting on Bratić, 2000, p. 93). Moreover, to ensure Yugoslav workers stayed connected among themselves as well as SRFY, they were not only fostered and supported by Belgrade, but they were also supervised, held in check, and controlled by Yugoslav authorities (Bürgisser, 2017, p. 540). The former is an important point, because it illustrates that labor migrants were seemingly kept in check by both the sending, as well as the receiving state. A note from a Swiss delegate illustrates this in no uncertain terms. In it, he praises workers from SFRY because they refrained from engaging in political activities:

It seems that the Yugoslavian guest workers concentrate much more on earning money than on politics; moreover, it turns out that they adapt much faster to our conditions and learn our language with surprising ease [Schreiben des Direktors des BIGA (1962), accessed via Dodis, cited by Bürgisser (2017), p. 551, footnote 2001, emphasis added].

Yugoslavs were, as this note (Aktennotiz) illustrates, considered welcome because they presumably cared little for political involvement, unlike “the partially remote-controlled foreign labor population from Italy” [(Notiz des Botschafters in Belgrad (H. Keller) vom 6, 2015), accessed via Dodis, cited by Bürgisser (2017), p. 552, footnote 2006]. It is, further, important to note that this delegate deemed the Yugoslav population as adaptive, and therefore presumably integrable (integrierbar). To be considered integrierbar, one might argue that labor migrants were to simply work and submit to their status. They were, in other words, expected to stand “before the law” (Ewick and Susan, 1998; Eule et al., 2019). Interviewees reflected their everyday experiences as labor migrants along similar lines. RuŽa, who had migrated to Switzerland in the 1970s, frames her encounter with Swiss acquaintances in the following terms:

The main thing is not to attract attention…for fear that I won't be good enough for them (my Swiss acquaintances). I always have this fear inside me that I won't be good enough for them #01:23:22-6# Interview with RuŽa on September 22nd 2020, Northern Switzerland.

A good labor migrant was therefore evidently a silent, non-political labor migrant. So-called second-generation migrants echoed the experiences of their parents, such as Admir:

What I noticed is that this generation, the most affected generation from the Balkans in Switzerland, does not politicize, they very rarely politicize. They have planned to come here, to lower their heads, not to stand out, not to demand anything, just be quiet, adapt #00:21:47-8# (Interview with Admir on December 1st 2021, Eastern Switzerland)

Admir had come to Switzerland during the late 1980s. His father, a former labor migrant, brought his family under the family unification scheme due to the ensuing unrest in Kosovo. For Admir, as for many other second-generation migrants, it was inexplicable why their otherwise eloquent, sometimes boisterous, or confident parents turned into silent, sometimes introverted, recluse individuals. Admir, as is the case for other interviewees, could not understand why their parents “chose” to stay silent. To be sure, the above situation unfairly renders individuals of the Yugoslav labor migrant community, passive, and suggests that individuals were at the mercy of decision and lawmakers in Switzerland as well as SFRY authorities. Individuals certainly carved out spaces of agency during this period. Brunnbauer, for instance, illustrates that labor migrants “voted with their feet”. Outmigration was therefore a silent critique of the government that was not able to keep its promises of socioeconomic security (Brunnbauer, 2019). The VUS provides illustrative examples about how individuals navigated their terms of labor migration.

An article published in the 26. April 1972 VUS edition estimates the number of SFRY individuals employed abroad amounts to 800,000 adding that this type of “modern labor migration” (moderna seoba radnika) has international dimensions (Vijesnik u Srijedu, 1972; Vjesnik u Srijedu, 1972a). Individuals abroad, according to the paper, were owed rights wherever they lived. These included, among others, decent living conditions, protection and safety at work, tools to integrate socially in the receiving state, and guaranteed education for the children in whichever receiving state labor migrants found employment (Vjesnik u Srijedu, 1972b). The SFRY trade union, meanwhile, situated itself as the major instigator that not only called international attention to existing problems, but styled itself as the organ that was tasked with overseeing that receiving states meet these demands. The term integration is interesting here and merits some more attention. Integration, as explained in an article published in 1975, included for labor migrants to gain access to decent housing, and equal chances for kids who accompanied their parents. Concerns raised repeatedly included language learning programs in the receiving state, as well as the establishment of SFRY learning institutions—essentially afterschool programs for kids “so they would not forget” their cultural heritage (VUS 5. January 1975). Integration, in other words, was framed as a positive-rights understanding, and thus clearly spelled out what labor migrants were owed to by Switzerland.

Clubs most often served as incubators where children were socialized into Yugoslav heritage, language, and other cultural affinities. Petar Dragišić found, for instance, a total of 39 clubs listed in Switzerland by 1978, 28 of which were registered with the SFRY General Secretariat—an official party organ (Dragišić, 2010, p. 129). This suggests a high fealty on both sides, the labor migrant population in Switzerland, as well as the Yugoslav authorities. Indeed, based on his research in the Jugoslav Archives, Dragišić cites a note in which a party delegate reports about the “massive base” that frequents the Jugoslav Clubs in Switzerland (Dragišić, 2010, p. 129). Besides serving as afterschool programs for kids and spaces of socialization, the clubs also registered how often and during which events individual labor migrants showed up. Clubs in Switzerland, as recorded by Dragišić, often projected movies of educational and propaganda value. An estimated 500 people, for instance, showed up to see news from Yugoslavia, while an estimated 13,000 people took part in the ceremonial Republic Day celebrations on November 29th 1978 (Dragišić, 2010, p. 131). The paper, in turn, often published about gatherings and outings organized by the clubs. In one of the columns titled Pisma Uredniku (Letters to the Editor), for instance, the Labor Migrant Club in Zürich invited people to attend further education for aspiring secretaries, adults who wished to complete their high school education, or joint outings to nearby cities (Vjesnik u Srijedu, 1971a). While information-harvesting during social activities served party organs, labor migrants cherished the space offered. Equally important were these mediums as spaces in which individuals received information regarding political developments in receiving states, including Switzerland.

Among the many insightful articles from the paper, two of them merit closer inspection. In the June 24th 1971 VUS issue, one J.O. contributed an article titled “What is Schwarzenbach up to this time?” (Vjesnik u Srijedu, 1971c, p. 67). In the article, J.O. recounts the previous Schwarzenbach initiative that was nearly adopted with a 54 no to 46 percent yes vote. The 1970s initiative was launched by James Schwarzenbach who managed to mobilize voters for or against a significant restriction to further migration with an incredible 74 percent voter turnout. Labor migrants presented the focal point of the initiative, and as such were slated for removal had the initiative been successful (see, for instance, Holenstein et al., 2018, p. 320–322; Tanner, 2015, p. 398–340). Reflecting on Schwarzenbach, and his involvement in the formation of the Republican Movement, a faction that had split from the National Action party,4 Rojčević states:

In the elections for the federal assembly in Bern, held at the end of October, these two xenophobic political structures won a total of 11 seats in the council of the federal parliament. A lot of people wonder what it means, and the direction into which this country is heading. (…) It can certainly be argued that a good part of the workers' votes went into his [Schwarzenbach] account, i.e., his supporters. Because their demagoguery is in short this: we are expelling foreign workers, so there will be plenty of apartments, hospitals, schools, the environment will be cleaner, and the purity and order that characterized the country through the ages, will be restored. In doing so, uncomfortable questions about the economy of the country, especially in the sectors of the most difficult jobs, with the most difficult working conditions, jobs that domestic workers do not want and will not accept, not to mention [the fact] that the country would not function at all, remain unanswered. Despite the success, or better yet the expansion of xenophobia from the level of a political party to the political agenda of the country's highest legislative institution, many believe that this will have no significant impact on government policy toward foreigners. Truth be told, the state is doing very little to protect foreign workers and improve their status especially considering the series of injunctions that even prevent people from choosing their place of work freely, change their employer, place of work, profession, and even the cantons [in which they live] (J.O. Vjesnik u Srijedu, 1971b, p. 67, emphasis added).

Labor migrants were not apolitical or passive, as the above news clippings illustrate. Quite the opposite is the case. Individuals were aware about their status as a disenfranchised workforce that had migrated to Switzerland for a specific purpose: to do “the most difficult jobs”, under “the most difficult conditions” that “the domestic workforce was not willing to accept”, as stated in the above article by J.O. It is, further, important to note that J.O. mentions conversations with other people in the clipping. “A lot of people” seemingly talked about the initiative that was launched about them—the foreign workforce—and “many believed” that whatever the outcome, no significant changes would come about. This is significant for two reasons. It suggests that an ostensibly critical number of labor migrants closely followed political discussions and understood the political processes by which they were portrayed “as the other”.

The lack of rights conferred upon labor migrants is a recurring point of contention in all the years examined between 1971 and 1977. It is interesting to note, however, that the Sindikat (labor union) spoke in the name of Yugoslav labor migrants as well as sectors that were particularly affected, instead of individuals on their own behalf. In an article published in 1975, a headline read: Sezonci nemaju sva ljudska prava! (Seasonal workers are not granted all the human rights):

Foreign workers, who have significantly contributed to the progress of the Swiss economy, are very affected by the consequences of the crisis. In the last 2 years, more than 100,000 of them could not keep their jobs, a good part of them were forced to return to their homeland. Employed foreigners (zaposleni stranci) and their families in Switzerland live in constant fear of losing their existence (Vjesnik u Srijedu, 1975, p. 22).

These lines were quoted from a labor union report stating that workers faced precarious working conditions, especially those working in the construction sector. It is here where we see the inherent “instability of citizenship” (Isin, 2020, p. 502). Switzerland ascribed to former Yugoslavs a “seemingly universal characteristic”, namely that of temporary labor migrants (Isin, 2020, p. 502). As a result, decisions enacted by the Swiss government and carried out within administrations, not only appeared overtly as a given, but laws also governing labor migrants seemed to have rendered “breaking frame, that is, rupturing normal relationships, practices, and identities”, very difficult (Ewick and Susan, 1998, p. 87). Because individuals were to some extent subject to both Swiss and SFRY mobility regimes, labor migrants kept a low profile and stood before the law in a way that entailed a reification process of legality by which individuals understand the law as a coherent, powerful, and fixed entity (Ewick and Susan, 1998, p. 86). It is important to emphasize here that labor migrants understood very well the sociopolitical discourse as well as the legal system that rendered their precarious position in Switzerland. They openly debated their rights, or lack thereof, with colleagues as well as in the paper. Understood from a “fair play” perspective, labor migrants ought to have already belonged to the sociopolitical community of Switzerland in addition to the SRFRY body politique judged by their “contributions to public institutions, including the public goods they provided” (Song, 2019, p. 176–177). At the time, however, the SFRY labor migrant community in Switzerland fits best within the engagement policies as to some extent navigated and developed by home states (Délano and Gamlen, 2014; Gamlen, 2014; e.g., Mencutek and Baser, 2018).

Starting in 1995−4 years into the Yugoslav Succession Wars—Western European states, including Switzerland, came to favor migrants from European member states (Sandro et al., 2013). Two developments thus transpired simultaneously: Switzerland increasingly sought to attract highly skilled migrants while individuals sought asylum from the Wars of Yugoslav Succession. Former Yugoslav citizens no longer came as labor migrants, but fled Yugoslavia as involuntary and forced refugees, often in the form of family unification arrangements. The war years thus introduce a significant geopolitical rupture into the ongoing sociolegal rupture taking place in Switzerland at the time. Switzerland, as well as EU member states at the time, reformulated their need for the type of labor needed to sustain economic productivity in Central and Western Europe. The question at the time was how to curb the up to this point predominant labor migration, to attracting a highly educated work force. It is here where one might locate the constituting political power narrative by which the above anonymized writer labels former Yugoslav as culturally distant. This rather “hostile environment” not only shaped the Yugoslav diaspora considerably but brought it into conscientious existence as a “rights claiming” (transnational) diaspora during the 1990sv. For this, the cooperation between individuals of the overlapping mobility regimes from before and after the 1990s was instrumental.

Migrants are, as I have learned while working on this project for the past 3 years, often “hyperaware” of the state (Menjívar, 2020). Inclusion to a state is tied to the papers one carries, and thus shapes one's sense of belonging especially when bureaucratic inscription practices bourgeon accordingly. The Yugoslav community serves as an exemplary community by which to illustrate this process. Former Yugoslavs constituted not only the dominant labor migrant group at the time, together with the Turkish and Portuguese populations (Spescha et al., 2019, p. 56–57). Instead, Switzerland also pursued to actively reduce the presence of former Yugoslav labor migrants by way of tightening the governance of belonging in legal, and then in social terms as the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), to which a majority of SFRY labor migrants belonged to in legal terms, was in the process of vanishing. As such, the convergence brought to the fore a lack of social and political rights conferred upon—or perhaps claimed by—the SFRY community up until the 1990s.

Sladjana: It was like someone had pulled the rug out from under me... When the war broke out, my residence permit was changed to F (temporarily admitted, Vorläufig Aufgenommen). #00:24:38-6#

Sandra: Do I understand you correctly, that you were a Saisonnier (Status A) before, and then the people at the Hallwilerstrasse changed your status to F? #00:24:50-2#

Sladjana: Yes … You have… if you look at the policy and legislative change regarding foreigners, you come to the Three-Circles-Model of the 90s. There, you will see several countries from which employers should hire workers, and from which countries they should not hire migrants. And, I mean, very soon all the Balkan countries were no longer recommended. Not at all anymore… #00:25:32-6# Interview with Sladjana on July 3rd 2020, Central Switzerland.

On May 16th 1991, the Federal Council releases a report under the title Foreigner and Refugees Policy (Report 91.036, 16. May 1991). The report introduced the Three Circles Model that, in harmonization with Agreement on the Free Movement (AFMP, Freizügigkeitsabkommen FZA) of Persons categorized foreigners into three sections:

- In an inner circle (freedom of movement), restricted to the countries of the EC and EFTA, the movement of persons is gradually freed from the existing restrictions on foreigners and the labor market.

- A middle circle (limited recruitment) includes the countries which belong neither to the EC nor to EFTA, i.e., which are not part of the inner circle, but in which we want to recruit within the framework of a limitation policy. From today's point of view, these include the USA and Canada in particular. The inclusion of other countries (especially in Central and Eastern Europe) is possible in the coming years. It will be easier to admit top executives from middle-income countries. Administrative simplifications, improvements in legal status, support for professional training and integration are possible.

- In the outermost circle (no recruitment, exceptions possible) are all other countries. This strict practice may be relaxed for highly qualified specialists for a stay of several years, but for a limited period of time, whereby the brain drain must not be accelerated (Report 91.036, 15. May 1991, p. 302).

At the time, former Yugoslavia was considered a “traditional area of recruitment” together with the USA and Canada. These states, legislators deemed, were “countries where cultural, religious, and social values are like ours (Report 91.036, 15. May 1991, p. 302, emphasis added). This means that, in other words, legislators considered Swiss people as culturally like other Europeans—those of the EC, i.e., Western Europe, to be sure—and somewhat like those of the second circle. The third circle was deemed “the other”, according to this logic.

The above-mentioned report triggered a fundamental debate surrounding political participation, naturalization, and the differentiation between so-called “real” refugees, and “economically motivated” individuals who sought to earn Swiss wages. Doing justice to the archival volume surrounding discussions about the three-circles model goes beyond the scope of this paper. I will therefore highlight small segments from discussions following the presentation of the report here.

Opponents of the proposal criticized the three-circles model as potentially racist, and discriminatory (Report 10. June 1991, p. 999). Switzerland was not only about to ratify racist and discriminatory policies but was further in danger of violating the Human Rights Charta, as well as UN Pact 1&2 (Report 10. June 1991, p. 1003). Speakers further praised labor migrants as essential in the service and construction sectors and emphasized that every ninth person working in the service industry was a labor migrant (Report 10. June 1991, p. 1002). Supporters, meanwhile, warned that the infrastructure in Switzerland suffered due to an “ever higher flood” of migrants, which might lead to the creation of ghettos in specific neighborhoods (Report 10. June 1991, p. 1000). Speakers further warned that “Switzerland is not a country of immigration” (Migrationsland), emphasizing that only migrants who have the capacity to integrate ought to migrate to Switzerland, especially as regards cultural and religious values (Report 10. June 1991, p. 1001).

Parliamentarians further debated questions revolving around the situation of “real vs. sham asylum seekers”, as well as labor migrants already present. One of the speakers framed it most poignantly:

What is the situation in practice with Turkey, for example, a classic recruiting country where political repression is the order of the day? Or how do these Federal Council criteria fit in with the situation in Yugoslavia? Yugoslavia has been a traditional recruiting country for many years. Today, citizens of this country top the list of asylum seekers. Does the Federal Council intend to delete Yugoslavia as a recruiting country? This would, above all, affect the 150,000 or so Yugoslav guest workers already working in Switzerland. This would exacerbate the problem of false asylum seekers (Report 10. June 1991, p. 1016).

Conversations following the three-circles proposal are illustrative for number of reasons, including the question about who belonged to the first circle. The question here is inherently orientalizing and illustrates how institutions tasked to resolve political participation and equality before the law do so based on a “consensus born of a basic violence” (Favell, 2022, p. 11).

In September 1991, the Federal Council downgraded Yugoslavia from the second- to the third circle. One year later in 1992, Yugoslavs were deemed kulturfremd (culturally alien) (see also Bürgisser, 2017, p. 561). Seasonal work permits had led, according to lawmakers, to massive immigration flows of low-skilled workers—a situation that needed correction. At the time, the popularity of the Yugoslav workforce declined steadily, as meticulously researched by Bürgisser. He notes that initially positive impressions, as illustrated above, soon gave way to rather negative stereotypes. Citing notes penned by the Federal Department of Justice and Police (FDJP) and their recommendation to suspend the 1968 visa agreement with Yugoslavia, Bürgisser traces how the Yugoslav workforce falls into disrepute (Bürgisser, 2017, p. 559). The reasons cited by the FDJP included increased delinquency, as well as pursuing work without a permit (Bürgisser, 2017, p. 558–559). While the three-circles model was to serve the purpose of a transitional period during which seasonal work permits were to be discontinued, it was never implemented due to relentless criticism in governmental and non-governmental criticism (see, for instance, Statement of the Federal Commission against Racism on the three-circle Model of the Federal Council on Swiss Foreigners Policy). Nevertheless, since 1994, seasonal permits were no longer issued to third-country nationals, particularly Yugoslavs, and the up until now possible conversion of the seasonal permit into an annual residence permit was denied (Spescha et al., 2019, p. 57). These developments unfolded considering Europeanization processes underway. Switzerland, as did EU member states at the time, reformulated their need for the type of labor needed to sustain economic productivity in Central and Western Europe.

In 1999, Switzerland signed the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons (AFMP), which officially replaced the Saisonnierstatut in 2002 that had hitherto governed the movement of all labor migrants, including that of the Italian, Spanish, as well as the Portuguese communities. While Swiss Europeanization processes subsumed the aforementioned communities within the AFMP, Swiss labor laws categorized Yugoslav and Turkish labor migrants as third-country “non-citizens” (Anderson, 2013) upon enforcing the treaty in 2002. At the time of ratifying the AFMP in 1999, the Wars of Yugoslav Succession had given way to the War in Kosovo that concluded a decade of warfare in the former SFRY. As such, the transforming legal system concerning labor migrants in Switzerland (and Europe more generally) based on the Swiss Europeanization processes coincided with the Wars of Yugoslav Succession. The concept of free movement in Europe created a common—not equal—ground for EU members, while third country individuals no longer fit within this constituting Swiss (as well as European) “community of value” (Anderson, 2013). My hitherto research suggests that it is during this timeframe in which the Yugoslav labor migrant community and the constituting SFRY diaspora turn their attention to understanding, internalizing, and transmitting questions pertaining to the legality of migration governance. Labor migrants, and especially their descendants, no longer stand before the law.

Razija: A lot has changed with since we moved to Switzerland. In Yugoslavia we always thought we were somehow welcome and had a good image in the world as a people. And then when we came to Switzerland, we realized that they didn't really mean anything good when they called us Yugo. And then we were a little surprised that we were not perceived in the way we expected, that the image of us is pretty different #00:11:35-#

Sandra: How do you mean? In what ways did you notice this? #00:11:49-6#

Razija: In the beginning it was small things. For instance, we had to buy furniture for the apartment. I remember we bought a new television, and when we went up to the counter to pay for it, the salesperson discouraged us from buying the model we had wanted. He said this model was way too expensive for us. Like this, small things. When we looked for an apartment, I had to call there for my parents, because they didn't speak German very well, and I learned it relatively quickly. My sister had learned it quickly, too. Landlords often rejected us during that time. They said we wouldn't get the apartment because there are four of us, but surely there would be ten of us squatting in the apartment. Other times we would come to the apartment to see it, but the people who were supposed to show us the apartment didn't show up at all. In the beginning, you don't connect the dots, but pretty soon, I realized that it was all somehow connected, when they started to call me Yugo at school. Yugo meant that a person had dirt on them. #00:13:03-4# (Interview with Razija May 12th 2019, North-Eastern Switzerland).

The term Yugo indeed turned into a pejorative term during the 1990s, as also conveyed by Razija. This was, however, not the case in the past. “Yugos” is an abbreviation for the word Yugoslav(s) and refers to Yugoslav people from the former SFRY. Jugo-Slav translates into a person of south-Slavic origin in Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian/Montenegrin (BCSM). The term “Yugos” developed into a pejorative term for people of Yugoslav origin that had migrated as labor- and forced migrants to Switzerland, especially since the dual rupture during the 1990s. The term Yugos, however, served as a simple self-ascribed attribute among former Yugoslavs that was used in casual conversations, as well as the paper. One can, for instance, find headlines such as:

Turnir u Baselu u čast Titova jubileja—Pokal dobrom domaćinu—sa svečanosti upućeno pozdravno pismo prisjedniku Titu—priznanja “Jugosu” za vrlo dobru organizaciju nogometnog turnira (Tournament in Basel in honor of Tito's jubilee—Trophy to a good host—a welcome letter to President Tito from the ceremony—recognition of the “Jugos” for a very good organization of the football tournament, Vjesnik u Srijedu, 1972c, p. 59).

Dopis iz Züricha: Uspjesi “Jugosa” I jedinstva. (Letter from Zurich: Successes of the “Jugos“ and unity, Vjesnik u Srijedu, 1971c, p. 75).

Around the year 2000, individuals started to deconstruct these narratives that dominated the logocentric assumptions surrounding the supposedly homogenous Yugoslav community. Individuals, in other words, assumed strategic essentialist positions to perform citizenship (Spivak, 1988; Isin, 2017).

Deconstructing sociopolitical stereotypes included multiple forms of resistance including music, cultural events that targeted “both citizens and non-citizens”, and active cooperation and lobbying in politics through social clubs and political associations (Isin, 2017, p. 503). To date, I have counted 67 clubs and associations, many of them with explicitly political goals and aims to connect and support members in the diaspora, e.g., the Albanian Association for Promotion and Integration5, i-plattform for Bosnians and Herzegovinians in Switzerland,6 amongst many others. Political strategies by which interlocutors occupied subject positions to make visible their critique “from within a structural position of subordination in society, while also critiquing that position” (Wolff, 2007, p. 4798).

We have only slowly come to the age, the second and third generation. Italians have already been a little more confident and cheeky during the 90s. So we, when I say we I mean those who came to Switzerland during our adolescent years, those of us who experienced the condemnation, something shifted in us. We had to do something. Take for instance Fete7 from Kosovo, I mean from Zug. Take Nenad8 from Ticino. Sure, we played a small role in the Seconda/Secondo movement, the original one. But it is more of a culture, we followed the culture of them a little bit and then we changed it to this Secondo, Secondo Plus. We wanted political participation; we demanded political participation. We wanted to get into politics. It was our goals to establish a lobby. We want to bring in our people. We wanted to bring in more diversity, more issues connected to questions revolving around migration. Since then, the movement got bigger and more diversified, later they came up with Operation Libero, and little by little we managed to get into politics… I mean, the term Secondo is per se a bad name, and it was always the goal to resolve that…But, anyway. Now, we our people in these [mainstream] political parties through this initial push, and we can lobby directly, though our people in parliament, for instance, who can represent our issues there now. And so, we have this national construct at one level, and we have dissolved into that. In individual cantons, this movement still exists. INES is one example. There are quite a lot of people from this first Secondo Plus group who are participating there now. #00:13:41-2# Interview with Ivo, J. 1, 2020. Northern Switzerland, emphasis added).

To bring in more issues of migration, as highlighted by Ivo and other interlocutors, meant that individuals highlighted their migration history to at once claim, and make visible their space at the socio-political center of Switzerland as members of a perceived minority. Officially, Ivo came to Switzerland together with his mother and brother to join his father under the family unification scheme during the 1990s, while he describes himself as an asylum seeker. Having initially fled from Bosnia to Croatia in 1992, his father brought him and the rest of the family to Switzerland shortly thereafter.

Ivo addresses several fundamental questions that illustrate how the creation of laws for a defined group stigmatizes people. Or, to frame it in the words of Karen Brodkin, the state, in this case the federal government, became a central force in defining a certain group “by having assigned them their spatial, cultural and socioeconomic place in this society” (Brodkin, 1998, p. 89). Namely, casual conversation and interviews with interlocutors, no matter when they immigrated, identify the 1990s as the crucial decade that defined their sense of belonging to Switzerland. Of course, one might argue, this is when the incredibly violent Wars of Yugoslav Succession broke out that accompanied this community for over a decade. And yet, examining closely the sayings and doings of interlocutors, it is also a loss of feeling safe in Switzerland as defined members of an unintegrierbaren group in addition to the loss of SFRY. Making rights claims thus served the purpose of claiming agency:

Sladjana: Somehow, everything came together. And I thought, okay, everything is somehow going in an unpleasant direction, even in my home country, and I have to make an effort to make this country my home country, or my second home country. I learn a new skill, something new. And so, I enrolled part-time at the University of Applied Sciences for Social Work, because everyone needed help somehow and I was always on duty. I translated at the women's shelter, translated for Caritas, just everywhere. #00:20:14-3#

I: How did this work? Was there any recognition of that? Where you there from the beginning, when they just starting to do that? #00:20:39-4#

B: The first translation lessons were interesting, with the counsellors and in the refugee centres. Well, I remember one of them did not consider to pay me? He said, “you are doing this for your compatriots”. I protested, and I said no, no, you can forget it, that's my time, give me the money, or else... So, it's like, you had to stand your ground like that. #00:21:15-3#

Sladjana pulls the narrative strands of this paper together in her reminiscing the 1990s. On the one hand, she lost her existential security with the discontinuation of Saisonnier permits, and her receiving a permit for temporarily admitted foreigners. Not only was it substantially more difficult to find work on a temporary status. Instead, potential employers expected her to work for free. Because Sladjana spoke BCSM, English and German with fluency, aid organizations perceived it as an obligation that she offer translation services for free based on Sladjana's place of origin. In this way—unwittingly or not—aid organizations and state employees reified the supposed homogeneity of the SFRY community. Sladjana finished her education in social work, and opened a business where she works with troubled youth from the Western Balkans.

In this paper, I am documenting the emic understanding of these othering processes to better understand the jurisdictional architecture of migrant “integration”, or rather exclusion, at present.

To be sure, focusing solely on people with migration biographies with, or otherwise individuals connected with the former Yugoslav community in Switzerland might insinuate a “methodological nationalist frame of reference”. Three motives, however, suggest themselves as explanations as to why I examine this community. First, former Yugoslavs were specifically targeted by legislature as being unable to integrate during the 1990s. Former Yugoslavs were therefore ethnified as one coherent group against the backdrop of one supposedly homogenous, integrated Swiss society. By focusing on the Yugoslav community, I hope to contribute to dismembering this binary misconception of homogeneity along ostensibly ‘ethnic' lines. Second, Five percent of the Swiss population has roots in Southeastern Europe (Bürgisser, 2017). Going back to the 1970s, Yugoslav mobility patters in Switzerland were linked to labor migration. While labor migration continued to dominate, family unification became equally dominant during the 1980s and 1990s as labor migrants already working in Switzerland sought to unite with their spouses and children while individuals sought asylum during the 1990s Wars of Succession. As a result, Switzerland is inextricably connected to the Western Balkans.

The Yugoslav “community” is far from uniform. And yet, categorizations abound, including the Yugoslav-state-perspective that abstracted labor migrants as “good migrants” vs. political émigrés, the latter of which SFRY considered as hostile toward the real-socialist project. These frames, conceptualized in the sending state, also carried over into the receiving state that is Switzerland, specifically regarding perceptions of the “good labor migrants” during the 1970s and 1980s. Individuals considered as low skilled workers, predominantly recruited as hands in the agricultural, construction, and service sector, and considered uneducated in Central and Western Europe, and bound to the seasonal worker statute to be renewed every 9 months. Qualified individuals, meanwhile, received temporary yearly permits, while many came as irregular-(ized) labor migrants especially during the 1970s, again others fled the violence during the Wars of Yugoslav Succession. The SFRY migrant community was therefore quite heterogenous to begin with.

The twenty-year time frame between the 1970s—and 1990s illustrates the extent to which Europeanization processes contributed to creation of third-country nationals, including former Yugoslavs, as “the other”. While labor migrants of Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese descent turn into Europeans Yugoslavs turned into ethnified and racialized. And yet, interviewees actively built Swiss-wide diaspora-connections and networks to aid each-other when legal and administrative questions arise, but also to actively influence the political and legal landscape in Switzerland.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because The project was approved by the Human Subjects Committee at the University St. Gallen upon assurance to keep all interviewees anonymized. Fieldnotes and interview transcripts will thus not be shared. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to c2FuZHJhLmtpbmctc2F2aWNAdW5pc2cuY2g=.

The study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee at the University St.Gallen. All participants provided their written and verbal informed consent to participate in this study.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

This study would have been impossible without interlocutors, and their willingness to share their emic perspective about the migration-integration-citizenship triad. I am indebted to Alberto Achermann who provided expert insight on the legal architecture of Switzerland's migration law. Katrin Kremmel, Oleksandra Tarkhanova, Jelena Tošic̀, Karolina Czerska-Shaw, Anna Mann, Insa Koch, and Kijan Espahangizi provided an invaluable space in which to discuss the migration-integration-citizenship triad on an ongoing basis. I would like to thank the Historical colloquium at the University of St. Gallen, especially Karen Lambrecht and Caspar Hirschi, as well as the Migration Colloquium at the University of Neuchatel, especially Christin Achermann and Stefan Manser-Egli, for inviting me to discuss early and consecutive drafts of this paper. Special thanks to David Nugent who directed my attention to questions of class and inequality before the law. Last but not least, I would like to thank the three reviewers who took their time to provide insightful and constructive feedback. Of course, all omissions are my own.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^Federal Statistical Office: “Composition of the foreign population: The permanent foreign resident population is the reference population in population statistics. The majority of foreign nationals permanently resident in Switzerland come from Europe, mainly from EU/EFTA countries. Permanent foreign resident population by nationality (at year-end, in thousands)”. Accessed January 9, 2023 at https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/bevoelkerung/migration-integration/auslaendische-bevoelkerung/zusammensetzung.html.

2. ^Please note that the term ‘labor migrant' includes highly educated, educated, less educated, and uneducated migrants.

3. ^Горана Крстић и Божо Стојановић, анаʌыза формаʌног и неформаʌног трзиста рада у србији, у приʌози за јавну расправу о Институционаʌним реформама у Србији, Божо Стојановић и др Београд: Центар за ʌибераʌно-Демократске Студије (2002): 31–33.

4. ^The Republican Movement split from National Action (NA) after a dispute between James Schwarzenbach and NA.

5. ^For more information see: https://avfi.ch.

6. ^For more information see: https://www.i-platform.ch.

7. ^First political delegate of Kosovo-Albanian descent in central Switzerland.

8. ^Elected to the Lugano City Council for the Ticino SP in 2004, and in 2007 to the Grand Council.

Abdelaaty, L., and Hamlin, R. (2022). Introduction: the politics of the migrant/refugee binary. J. Immigrant Refugee Stud. 20, 233–9. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2022.2056669

Achermann, C. (2013). “Excluding the unwanted: dealing with foreign-national offenders in Switzerland,” in Ataç, I., Sieglinde, R. eds. Politik der Inklusion und Exklusion p. 91–109.

Agar, H. M. (2008). The Professional Stranger, 2nd edition. United Kingdom- North America-Japan-India - Malaysia- China: Emerald.

Anderson, B. (2013). Us and Them? The Dangerous Politics of Immigration Control. Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199691593.001.0001

Bade, J. K. (2003). “Migration and migration policies in the cold war,” in Bade, KJ, ed Migration in European History. doi: 10.1002/9780470754658

Bauböck, R. (2010). “Cold Constellations and hot identities: Political theory questions about transnationalism and diaspora in Diaspora and Transnationalism—Concepts,” in Rainer, B. and Thomas, F., eds Theories and Methods. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. doi: 10.5117/9789089642387

Bratić, L. (2000). Soziopolitische organisationen der migrantinnen in Österreich. Kurswechsel. 1, 6–20.

Brodkin, K. (1998). How Jews became White Folk and what that says about Race in America. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Brunnbauer, U. (2019). Yugoslav gastarbeiter and the ambivalence of socialism: framing out-migration as a social critique. J. Migrat. History 5, 413–437. doi: 10.1163/23519924-00503001

Bundesamt für Statistik. (2021). Ausländer/innen, die die Einbürgerungsbedingungen erfüllen, nach Geburtsort und verschiedenen soziodemografischen Merkmalen. Available online at: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/bevoelkerung/migration-integration/auslaendische-bevoelkerung/zusammensetzung.html (accessed January 9, 2023).

Bundesgesetz über Aufenthalt und Niederlassung der Ausländer (ANAG) vom 26. März. (1931). (Stand am 30 November 2004).

Bürgisser, T. (2017). Wahlverwandtschaft zweier Sonderfälle im Kalten Krieg. Schweizerische Perspektiven auf das sozialistische Jugoslawien 1943–1991. Bern: Diplomatische Dokumente der Schweiz

Burri, S. B., Efionayi-Mäder, D., Hammer, S., Pecoraro, M., Soland, B., Tsaka, A., et al (2014). Die Kosovarische Bevölkerung in der Schweiz. Bundesamt für Migration BFM/EJDP. Available online at: https://www.sem.admin.ch/, 1–140.

Creating Safety. My Home–our Switzerland (2007). Museum of Design Zurich Archive of the Zurich University of the Arts. Available online at: https://www.emuseum.ch/objects/130220/ivan-s-vergewaltiger–bald-schweizer-gegenentwurf-nein-?ctx=53a9d1397823ee3d8b8bb3dc6339b7188692ccb6andidx=27, last updated (accessed April 7, 2023).

Dahinden, J. (2016). A plea for the ‘de-migranticization' of research on migration and integration. Ethnic Racial Stud. 39, 2207–2225. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2015.1124129

Dahinden, J., and Stefan, M-. E. (2022). Gendernativism and liberal subjecthood: the cases of foced marriage and the burqua ban in Switzerland. Soc Polit Int Stud Gender State Soc. 30, 140–163. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxab053

D'Amato, G. (2022). “Immigration and Integration in Switzerland: Shifting Evolutions in a Multicultural Republic,” in Hollifield James F., Martin Philip L., Orrenius Pia M., Martin Philip L., Héran François (éd.), Controlling immigration: a comparative perspective. Fourth edition. (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press) p. 457–489. doi: 10.1515/9781503631670-027

Délano, A., and Gamlen, A. (2014). Comparing and theorizing state–diaspora relations. Polit. Geography. 41, 43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.05.005

Dragišić, J. (2010). Dragišić, Petar: Klubovi jugoslovenskih radnika u zapadnoj Evropi sedamdesetih godina. Tokovi istorije 1S, 128–138.

Ellermann, A. (2013). When can liberal states avoid unwanted immigration? Self-limited sovereignty and guest worker recruitment in Switzerland. World Polit. 65, 3. doi: 10.1017/S0043887113000130

Ellermann, A. (2021). The Comparative Politics of Immigration: Policy Choices in Canada, the Unites States, Germany, and Switzerland. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781316551103

Eule, T. G., Borrelli, L. M., Lindberg, A., and Wyss, A. (2019). Migrants Before the Law—Contested Migration Control in Europe. London: Palgrave McMillan. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-98749-1

Ewick, P., and Susan, S. S. (1998). The common place of law—Stories from everyday life. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226212708.001.0001

Favell, A. (2022). Immigration, integration and citizenship: elements of a new political demography. J. Ethnic Migrat. Stud. 48:3–32 doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2022.2020955

Fraser, N., and Honneth, A. (2003). Redistribution or Recognition? A Political-Philosophical Exchange. London and New York: Verso.

Gamlen, A. (2014). Diaspora institutions and diaspora governance. Int. Migrat. Rev. 48, S180–S217. doi: 10.1111/imre.12136

Gees, T. (2006). Die Schweiz im Europäisierungsprozess – Witschafts- und gesellschaftspolitische Konzepte am Beispiel der Arbeitsmigrations-, Agrar- und Wissenschaftspolitik, 1947-1974. Zürich: Chronos Verlag.

Glaser, B. G., and Strauss, A. L. (2008). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New Brunswick, NJ, Transaction.

Hainmueller, J., and Hangartner, D. (2013). Who gets a swiss passport? A natural experiment in immigrant discrimination. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 107, 159–187. doi: 10.1017/S0003055412000494

Hamlin, R. (2021). Crossing: How we Label and React to People on the Move. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781503627888

Hangartner, D., Kopp, D., and Siegenthaler, M. (2021). Monitoring hiring discrimination through online recruitment platforms. Nature 589, 572–576. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03136-0