Abstract

The conceptual novelty of this article rests in seeing identity not as a nominal category, but as a complex sequence of relationships between groups and narratives. It offers a deeper reading of Engin Isin's “citizenship in practice” and an empirical interpretation of how Andersen's imagined communities are brought to life through print media. Drawing from Raivo Vetik's analysis of the Estonian ethnopolitical field the author explores narratives of two major Russian language web-portals in Estonia: Rus.Postimees and Rus.Delfi. As a result, the reader may observe how the practice of citizenship simultaneously constitutes and is constituted by the minority's identity and subject position. The content analysis conducted from the samples of the aforementioned media outlets shows that the lack of shared citizenship practices between the majority and the minority causes a voluntary grouping along the lines of legal status, language, space and ethnicity. Discussing what constitutes Isin's act of citizenship the author concludes that acts are far more elusive than the ruptures they cause. A media analysis shows that aside from bearing long-term ruptures such as geographical, linguistic or formal, Estonian citizenship practice also received a new one, namely the symbolic rupture caused by the war in Ukraine. By breaking the previous status-quo, it pushes forward securitization and forces the minority to contest, redefine, and reestablish its allegiance and perceptions of its place in Estonian society.

Introduction

Rogers Brubaker's relational attack on the mainstream usage of categories such as nations, groups and diasporas has left a certain vacuum at the junction of nationalism, migration and citizenship studies. Calling for a “groupless language”, Brubaker focused on studying ethnic group mobilization in relational terms, while overlooking how his fellow-researchers construct those theoretical categories (Csergo, 2008, p. 393). The following article aims to overcome this shortcoming by appealing to Engin Isin's reading of citizenship within the Bourdieusian field theory.

I analyze the discourse of the Russian speaking media in Estonia as an example of Isin's citizenship in practice. Specifically, I claim that the practice of constitution of media narrative is the actual mechanism behind the creation of what Benedict Anderson called an “imagined community” (Anderson, 1983). Anderson stated that the “written word” plays a key role in forming a community, alluding to the invention of the printing press and multiple local communities transforming into a single nation by reading the same news, and imagining that it happens to the virtual “them”.

The structure of the article is as follows: A relational orientation to identities is undertaken by an explicit unpacking of Vetik's recent work in the Estonian ethnopolitical field. The need to explore the institutional, discursive and symbolic realms in tandem is explored through making a distinction between micro and macro identity partially covered in Tajfel's works. In this context, I explicitly bring Vetik in dialogue with Tajfel and other scholars in the field of ethnic identity construction to demonstrate how the basis of identity necessarily draws from self-identification of a group and external categorizations by out-groups. With this theoretical unpacking I aim to clarify what role identity has in the relational concept of citizenship.

The second section presents a broad exposition of the Estonian case using Isin's notions of citizenship practice, acts, and ruptures. These notions allow us to gain a deeper understanding of how citizenship practically acquires its meaning, content and purpose. Moreover, it shows how, thanks to acts, ruptures become part of citizenship practices. Also, this section strongly draws from Vetik's insight into the asymmetry of the Estonian ethnopolitical field and empirical data of Integration monitoring 2020. The third part, delves deeper into Benedict's Anderson's vision of imagined communities, print-capitalism, media and language domination. Using the Estonian example, I claim that identity is not simply narrated by print-capitalism, but rather engaged in a mutually constitutive relationship with it. In the final section, I am analyzing the role of largest Russian language news portals in forming our understanding of Estonian citizenship, particularly its vocabulary, practices and ruptures. Thus, before looking at the broader picture of interethnic relations in Estonia and the fragmentary nature of a citizenship practice, we need to ask what exactly is this identity that being imagined?

Micro and macro level identity

At this point we should distinguish the relational approach to group identity and citizenship from other essentialized versions. Vetik (2012, 2019) explores the Estonian ethnopolitical field in a relational language past the binaries of nominal essentialized groups. Similar to Isin, Vetik's insights provide an empirical unpacking of differences in subject positions (combination of opinions and perceptions defining a place of an individual within a social field) between competing majority and minority groups. Instead of seeing the categories of Russian or Russian Estonian, as nominal, Vetik invites reflection on the constitution of these subject positions. Following Bourdieu (1985), Vetik contends that identity and inter-ethnic dynamics are constituted in asymmetrical power relations. He further demonstrates how this field of ethnic identity is a relational and complex sphere where subjects, orientations and positions compete to establish and maintain an objective and subjective existence. In this context, the struggles for identification in ethnopolitics are not simple matters of the institutional vs. the symbolic, but draw in various scales from the macro and micro-level. Kruusvall et al. (2009) further argue that the space/field/arena in which these identity claims are articulated and challenged requires active engagement and strategic adaption from all subjects including minority and majority groups. Thus, the examination of Estonians or Russians is not simply a case of them existing, but must be unpacked. It is in this context that I claim that Anderson's imagined community and consumption of media help to demonstrate an ethnopolitical context in which claims of identity are standardized, negotiated, and contested. Further, Tajfel's insight relating complex micro-level subjectivities to macro-scale dynamics of identity can help to explore the nexus of relationships that constitute media discourses in Estonia.

According to Tajfel the social identity is “that part of an individual's self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership in a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership” (Tajfel, 1978, p. 68). However, if researchers excessively rely on the self-perception of their respondents, they tend to repeat the same mistake as the majority of those respondents: to treat features forming identity as real. But what problems does it actually entail and how can they be avoided?

Before giving a comprehensive answer to the question asked in the previous paragraph let us clarify the most serious contradiction between the micro and macro level understandings of citizenship and identity. The micro level understanding of citizenship perceives it as a membership or a position of an individual in a certain group. This level is arguably the closest to the everyday understanding of identity by a person without familiarity of the intricacies of existing debates in modern social science. By thinking about citizenship in terms of membership, an individual defines one's own place in a certain group (I am ethnic Estonian, ethnic Russian) and can formulate relatively clear criteria by which people are ascribed to an inner or an outer group (Estonian/Russian is my mother tongue, I can hear your accent and tell to which group you belong).

Tajfel and Turner (1986), standing at the roots of Social Identity Theory called this process: internalization of identity (p. 17). In other words, it is not enough for you to call yourself Russian, the members ascribing themselves to the group of ethnic Russians should also agree with you. This process also scales to a higher level: individuals need to internalize group membership in a way that should be recognized by the out-group (Tajfel and Turner, 1986, p. 17), or within the scope of this article, by ethnic Estonians. At this point Tajfel and Turner express a notable shift from nominal to more relational language. They emphasize that the attributes for the intergroup comparison must have a comparative value. Not all of the differences/similarities are valid when trying to tell one group from the other, but only those charged with the aim to achieve a superiority of one group vis-à-vis the other (Tajfel and Turner, 1986, pp. 17–18).

Isin warns, that when studying such a complex set of relationships, there is always the danger of falling into either objectivism or subjectivism (Isin, 2002, p. 26). Excessive objectivism is one of the varieties of essentialism, when a parameter pertaining to an analytical construct, such as social identity is perceived as a feature defining a group in reality. For example, when you frame the Russian minority in Estonia exclusively through ethnic, racial, labor market and language terms and expect the representatives of this group to behave in accordance to those properties. Subjectivism focuses on the self-perception of a person and assumes that self-definition is key to classification, while in fact it is also not. A member of a group might lack knowledge for such identification, never articulate it explicitly, or not be accepted by the other members of the group (Isin, 2002, p. 26). So, how can these issues be addressed?

Even though Isin warns against either objectivism or subjectivism, it is impossible to avoid them entirely. We cannot deny the fact that properties of social identity constantly manifest themselves in reality. Neither can we dismiss the subjective understandings of individuals about themselves and the out-group, because the sum of those subject position constitutes the relational field of a nation. The first thing we can do to solve this conundrum is to look within the field of psychology. For example, Ehala (2018) suggests stopping treatment of signs of identity as indices having a causal connection between the sign and its definition like a name or fingertips. Instead, he proposed perceiving the signs of identity as actual symbols defined in arbitrary terms, but requiring the agreement of the absolute majority (Ehala, 2018, p. 48).

Identity is but a part of citizenship, which is hardly possible to define without being political. Taking into consideration the complex process of internalization discussed at the beginning of the section, I claim that social identity is the closest thing individuals have to membership. However, Isin specifically points out that citizenship should not be considered as membership (Isin, 2009, p. 371). Instead, he provides the following relational definition:

“Citizenship is a dynamic (political, legal, social and cultural but perhaps also sexual, aesthetic and ethical) institution of domination and empowerment that governs who citizens (insiders), subjects (strangers, outsiders) and abjects (aliens) are and how these actors are to govern themselves and each other in a given body politic” (Isin, 2009, p. 371).

This definition allows us to look at citizenship as a macrolevel phenomenon including the membership function of identity, but not limited by it. I emphasize that such approach does not discard the theoretical concepts of Tajfel's and Turner's intergroup behavior, but instead utilizes them while looking beyond the microlevel internalization of identity. As we can see from the definition, the relational approach brings power and institutional structure into the picture. Even by ascribing oneself a certain identity an individual or a group claims dominance or resistance/adaptation to this dominance. At the same time, citizenship is not limited to the traditional static legal form, it also includes a practical everchanging aspect forming the positioning strategies of the engaged actors and the body politic itself. Nonetheless, the question which still remains is how does one operationalize Isin's version of citizenship?

Acts and practices of citizenship in Estonia

In Isin's vocabulary citizenship may manifest itself in two different ways: as a status and as a practice. Fein and Straughn (2014) suggest looking at citizenship from three basic understandings. The first one is normative/territorial, traditionally associated with a legal status pertaining to a certain territory, reinforcing an individual's human rights (reflected in the constitution and international law) and imposing obligations. The second is pragmatic/utilitarian, picturing citizenship as a choice benefitting an actor. The third one lies in the affective/symbolic dimension and signifies the feeling of attachment to an imagined community (Fein and Straughn, 2014, p. 694). If the first two fall under the umbrella of citizenship as status, the third category is much closer to “citizenship as a practice” associated with the issue of belonging, defining one's membership and place in the society.

What are the most important factors contextualizing minority citizenship practice in Estonia? Russians are the largest minority in Estonia. According to data from 2022, out of the total population of 1, 331, 796, there are 315, 242 Russian minority members, who comprise about 23.6% of the aforementioned total (Statistics Estonia, 2022). Most of the current minority members are first/second generation immigrants, or descendants of those, who came to Estonia after the Second World War. According to the demographic statistics from 1934, during the time of the first Estonian republic, Russians were a rather small minority, representing only 8.2% of the population, while by the end of the Soviet reign they amounted to 30.3% (Eesti Entsükloopedia, 2012). Such a rapid migration along with a different attitude toward the fall of the Soviet Union predetermined a number of long-term problems in the Estonian interethnic relations.

In constructing an identity based on both internal and external identifications of the other, the ethnic-minority in Estonia is simultaneously viewed by the Estonian state lens and by the lens of Estonian history as an external other in close proximity to the Russian federation (Pettai, 2006; Makarychev, 2019; Vetik, 2019). Thus, minorities in Estonia occupy the unique position of being considered a potential source of threat and a group requiring the focus of Estonian politicians, the ministry of internal affairs, and security agencies. For example, in February 2020, Riigikogu (2020) (Estonian national legislature) passed a statement “On Historical Memory and Falsification of History”, in which it condemned the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, laid equal blame on the USSR and Nazi Germany for the instigation of the Second World War, and accused modern Russia of weaponizing history. Later, on May 8th all three Baltic countries issued similar statements. The objectivity of these allegations notwithstanding, these interpretations of history provide a contentious backdrop where the wedge between the Russian minority and ethnic majorities can be played out. In this context, Russians in Estonia are led to reorient their identities and strategies of belonging, either in favoring the Riigikogu perspective or aligning themselves with the view offered by the Kremlin in which Russians are celebrated as the primary liberators of Europe from Nazism. Drawing from the idea that “collective memory is the keystone of national identity” (David and Bar-Tal, 2009, p. 168), I argue that, recasting of history is neither abstract nor passive, but is instead played out in active politics and used for solidifying identities as much as rupturing them.

Since the start of the Ukrainian war in February 2022, dilemmas for active association in history can be felt more tangibly in the Estonian ethnopolitical field. A particularly insightful moment where competing narratives of belonging come to light is the Narva tank incident. In August 2022, the Estonian government moved a soviet T-34 tank from the outskirts of Narva to the military history museum in Viimsi. In addition, it also forcibly removed and utilized some of the old Soviet sculptures and monuments devoted to the Second World War. This action was preceded by several weeks of protests attended by a notable number of local residents who stood vigil around the tank and surrounded it with flowers and candles, making it look more like a place of religious worship than a military monument. The celebration and active call for preservation of these monuments demonstrates how, for many Russians in Estonia, monuments are not passive objects of a forgotten era, but rock-solid proof of the role Russians played in history of Estonia and the whole of Europe. However, from the dominating Estonian point of view, the Soviet monuments are a living reminder of one oppression after another and that freedom did not come until the very fall of the USSR. The last time when these two irreconcilable narratives clashed was in 2007 (Ehala, 2009), when in Tallinn the relocation of “Bronze soldier” (a monument commemorating the soldiers who died in the Second World War) caused violent riots and looting by the Russian community, which felt its identity threatened.

In contrast with 2007, the 2022 protests were peaceful and subsequently followed by negotiations between the prime minister Kaja Kallas and the Narva city council, which started productively, but ended in an ultimatum, in which the national government demanded the local authorities remove the tank, or it would do so itself (Õhtuleht, 2022). The Narva city council made a counteroffer of moving the monument from its previous location, but in the end, refused to take responsibility, as voting on the issue ended inconclusively. As a result, the central government delivered on its promise and using considerable police force and building equipment, moved the tank and destroyed the other monuments. Despite the preceding protests, in contrast with 2007, the whole action was carried out without any clashes with the local community. What is evident in the example above is the contested nature of historical memory and its association with Estonianness today. In navigating the complex discursive and historical domains of Russians in Estonia, the minority finds itself having to negotiate, contextualize and challenge the state position on its loyalty and contributions against fascism.

The key to the Narva tank removal lies in the symbolic dimension. The government justified its actions by claiming that the Russian weaponry, which is currently deployed in Ukraine and has been used for Estonian oppression, should not be displayed as a monument and belongs in the past, as it provokes tensions (Õhtuleht, 2022). However, for a large share of the Russian minority community, these issues are not directly connected. As something used for liberation of Estonia from Nazism, the tank was a part of a positive identity. Nonetheless, it would be a mistake to present the entire problem as a dualistic conflict between the Soviet and the Estonian mainstream narratives. The entire field of subject positions within the local community has multiple discourses concerning historical and present issues, where a pro-Soviet stance is far from dominant. Despite the forceful approach of the government, the monument removal did not cause the Russian community to unite against this decision, because the hybrid Russian and Soviet identity is strongly marginalized and has no recourse for producing a viable political force (Makarychev, 2019). However, the problem is that securitization of state politics inevitably polarizes society and deepens the divide along ethnic lines (Bigo, 2006). That leaves both of the Estonian ethnic groups struggling for, as Vetik put it, the “moral high ground”, where the majority demands unity around ethnic nationalism and the minority group “calls for equal opportunities regardless of ethnic background, based on civic nationalist ideology” (Vetik, 2019, p. 413).

Almost every recent security action taken by the government in the year 2022 causes a further asymmetry in the field of interethnic relations. For example, the decision to confiscate firearms from permanent residents with Russian citizenship has branded them as potentially dangerous for Estonian security (RUS.ERR, 2022c). The decision of the new coalition, which equated the presence of Russian citizenship with a lack of loyalty to the Estonian state, was motivated by the current war in Ukraine. Therefore, such political actions polarize and simplify the field, causing minority members to contest the disloyalty alleged on the basis of formal citizenship and appeal to the equal rights narrative. This became even more salient when the coalition started debating the removal of voting rights from the same minority group over similar security concerns (RUS.ERR, 2022a) or decided to drive all international students with a Russian passport out of the country by forbidding them to apply for new resident permits (RUS.ERR, 2022b). Under these conditions, formal citizenship status becomes a key criterion, equating citizenship with loyalty. This negatively affects the unity of the nation as long term-minority members may feel their rights diminished. At the same time, recent migrants are outright rejected, as they are judged not on the basis of their actual political positions, skills and loyalty; but their citizenship, which they cannot easily change. This causes a notable shift in opinion on the issue among more mainstream-aligned members of the minority. Even if one does not exercise the right to bear arms and has zero regrets over Soviet symbols, it is still largely concerning to be treated as a threat and deprived of rights available to majority. Thus, due to this crisis, Estonian citizenship is being renegotiated in both of its aspects: as a status and as a practice, causing me to keep the focus on both.

Before revealing the next layer of Estonian interethnic field, we need to take a step back to Isin and discuss another theoretical concept involving citizenship. So far, we have already encountered citizenship as a status (bearing a passport of certain country) and citizenship as practice (or actions, which take place regularly and originate from various subject positions). What unites them both is relative stability of configuration: a legal status is visible, seldom changed, and easy to use for mobilizing identities, but may be misleading, as we can see from the previous paragraph. The practice of citizenship also presupposes repetitive patterns of behavior, which may be reflected in laws, customs, or other social institutions. In opposition to status and practice there stands an act of citizenship. According to Isin:

“How do we understand ‘acts of citizenship'? The term immediately evokes such acts as voting, taxpaying and enlisting. But these are routinized social actions that are already instituted. By contrast, acts make a difference. We make a difference when we actualize acts with actions. We make a difference when we break routines, understandings and practices” (Isin, 2009, p. 379).

Isin argues that acts introduce ruptures into practices. In terms of citizenship practices a rupture is a break, which changes the conditions in which actors operate. Following Isin's logic: if practice is following or reacting to a script, then an act means changing the script entirely, where rupture is the new beginning (Isin, 2009, p. 379–380). I find the notion of an act of citizenship fascinating but rather problematic to approach empirically. An act is always purposeful, but is not necessarily conscious, and there is no way to tell if it is “inherently exclusive or inclusive, homogenizing or diversifying, or positive or negative”, as qualities appear after an act has already taken place (Isin, 2009, p. 381). This retrospectivity and the difficulty with defining the level on which an act actually takes place gives a researcher immense freedom, where almost anything can be considered as an act of citizenship, given that it has transformed modes of being political and divided a nation into “citizens, strangers, outsiders and aliens” (Isin, 2009, p. 383).

Arguing whether a particular set of actions is an act or not, goes beyond the scope of this study, and might not be as productive as focusing on ruptures instead. I claim that some ruptures in the Estonian notion of citizenship are much larger than a single act and might be caused by multiple acts over time. Yet, it is not easy to identify a time horizon of any one particular act resulting in rupture. Rather, these ruptures can widely be seen across the linguistic, spatial, legal (formal) and more recently, symbolic domains that collectively constitute/frame citizenship. Hence, these ruptures require a deeper embedding in the acts, memories and symbolism that frame them. For instance, problems with Estonian language proficiency in Ida-Virumaa (the most Eastern part of Estonia), cannot be understood solely in relation to the consequences of post-Second World War migration (discussed at the beginning of this chapter) but extend to current events in independent Estonia. According to the most recent Estonian Integration Monitoring, only 21% of Ida-Virumaa residents demonstrate active language proficiency (EIM, 2020, p. 35). By explaining this with the high concentration of minority members in the northeastern region of Estonia, where there is no Estonian language environment, we can identify two ruptures.

First, there is an obvious linguistic rupture, which frames multiple practices from administrative (the language of government services available to the minority population) and political (language of political canvassing, communication with politicians) to education and media consumption. Second, the spatial rupture strongly influences language contact. Nation-wide data from Integration Monitoring indicates that most (51%) minority members interact with Estonians mostly at work or school and quite less often during their free time (32%) (EIM, 2020, p. 36). The lack of language proficiency and geographical distribution is constituted by and constitutes the format of contact between communities. Therefore, the nature of this contact reinforces the formality of majority-minority relationships, where the Estonian language gains a pragmatic role, rather than being socially or culturally uniting.

Second, about 6% (Statistics Estonia, 2022) of the current Estonian population still has a status of aliens or non-citizens. Those are Soviet Union citizens and their descendants, who by the decision of the authorities, did not qualify for Estonian citizenship right after Estonia regained its independence. According to the 1992 citizenship law, in order to be considered as Estonian national, these people should have provided proof, that their ancestors were citizens of the first Estonian republic prior to the 1940s. Many failed to produce such evidence, resulting in a large share of minority members in 1990s and later on opting for for an Estonian alien passport or Russian citizenship. This factor is quite well reflected in multiple works (Vetik, 2012; Fein and Straughn, 2014; Jašina-Schäfer and Cheskin, 2020), which try to distance themselves from a traditional state-centered view of citizenship and instead build their arguments around the logic of belonging and narratives behind the citizenship choice of the Russian speaking residents of Estonia. Balancing normative considerations, the actual utility of your passport, and the emotional connections to the Estonian state culture and nation, all of the aforementioned researchers touched upon the complexity of citizenship practices of the Russian minority of Estonia.

The analysis of both existing linguistic and formal citizenship ruptures between the communities is now further complicated by newer symbolic ruptures resulting from the ongoing war in Ukraine. The first one is related to the radical polarization within the Russophone communities in Estonia (more on this in the empirical section below) internally polarized the Russian speaking community in Estonia (Rus.Delfi, 2022). The attitude toward Ukraine and support of Ukrainian people fighting for freedom, liberty, and survival of their nation has become a watershed, excluding a pro-Kremlin stance in any form from being a part of Russian Estonian identity or a minority citizenship practice. The most recent manifestation of this rupture is the Narva tank removal, which outlines the contested boundaries of what is considered to be an appropriate display of a Russian Estonian identity and what cannot be a part thereof. During the debates around the meaning of the Narva tank and the actual necessity of its removal, most of the engaged individuals one way or the other based their line of argument on symbolic allusion to the current war in Ukraine.

Thus, what we observe across these ruptures, is a struggle for the moral high ground between the minority and majority members, where the majority's citizenship strategy is centered around the core of Estonian ethnic identity, which demands ancestral descent or proof of loyalty from potential citizens. From the dominating point of view of the majority, the primary threat to Estonian national unity is the uneven demographic composition left as an aftermath of the Soviet Union (Vetik, 2019, p. 408). Four years ago Vetik claimed that the demographic situation and Russian expansionism have been used as a justification by multiple Estonian politicians for pushing through security policies. They have tended to present those policies as countermeasures defending Estonian language and culture (Vetik, 2019, p. 409). Today we once again may witness the truth of this observation, as the war in Ukraine has been used in every instance when the minority rights or loyalty have been questioned (RUS.ERR, 2022a,b).

In case of formal citizenship, loyalty is measured by the wish to learn the Estonian language, pass a constitution exam and undergo the naturalization procedure. From the view of majority, this is a logical continuation of a “language-centered model” of integration of the Estonian society, where ethnic diversity is recognized alongside the common language denominator and implies hierarchal inequalities (EIM, 2020, p. 103). From the view of minority, this is the issue of equal rights. For many members of the Russian minority, being born in Estonia and living in it for dozens of years automatically means that one should qualify for Estonian citizenship and should not be treated as a migrant. Both narratives constantly compete with each other, and even though the majority's narrative is clearly dominant, many minority members contest it with their resistance to applying for Estonian citizenship on these conditions (EIM, 2020, p. 46). Nonetheless, this practice of citizenship does not acquire a performative aspect. Isin tells us that for an act of citizenship to happen, a group of people needs to claim their rights and enact political subjectivity (Isin, 2009, p. 368). Despite the belligerent lexis of this definition, the act of claiming does not necessarily mean an aggressive mobilization of Russian minority's ethnic identity, similar to the one which happened in the year 2007 when a mob outraged by the Bronze Soldier monument dismantling clashed with Police in Tallinn. Instead, it means the activation of an imagined identity trying to find its place, alterity, and belonging.

Imagining community

Undoubtedly, Benedict Anderson's “Imagined Communities” (Anderson, 1983) is one of the most well-known important works in the sphere of nation building. At the same time, it is one of the most misinterpreted studies in the field. As Enric Castelló emphasized in his review of the Anderson's work: many researchers tend to jump from the first few introductory pages to an automatic conclusion that nations are imagined through media, while ignoring the rest of the book (Castelló, 2016, p. 61). At the same time Anderson hardly uses the word media throughout the whole text and is more focused on print-capitalism or the way industrial productions of written texts shift the way individuals perceive the group to which they belong.

Anderson argued that printed capitalism affected the creation of national consciousness in at least three ways. First, it allowed multiple people within a nation to understand each other better thanks to standardization of language. Second, the same process granted people a certain level of temporal fixity and lowered the bar to accessing information, as instead of understanding the dialect or writing tradition of a specific monastery, people could rely on a certain standard. Third, printed media has inevitably empowered specific varieties of language while weakening others, which has made some of the ethnic groups dominant over the others, as their language became primary and all others turned into regional dialects (Anderson, 1983, p. 42–45).

In case of the major western powers, which acquired their independence a long time ago, the foundational part of the nation building has already ended. From Anderson's point of view, European nations cement the status-quo when a language becomes a language of power and linguistic nationalism reaches the point where status is no longer contested by a serious competitor (Anderson, 1983, p. 42–45). This does not necessarily mean a dominance of a single language, but instead may result in an equilibrium achieved by several languages like in the case Switzerland, where several monolingual nations are united by a bilingual or trilingual political class (Anderson, 1983, p. 138).

For Estonia this process is still ongoing and gradually happening even today. In a similar manner as vernacular languages overcame Latin as a lingua franca, the Estonian language has already substituted Russian as a language of power and administration, which Russian used to be in the times of the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, an even more serious problem is in the Russian language being perceived as contender, which results in segregation of the Estonian education system. On the one hand, a large share of the Russian minority parents defend a persistent narrative of minority children being entitled to education in their own language. According to data from the most recent Estonian Integration Monitoring, about 44% of minority parents would prefer their children to study at fully Russian-language schools or Russian-language schools where some subjects are taught in Estonian (EIM, 2020, p. 20). In contrast to that first group, is the 46% of minority parents, who would prefer fully Estonian schools, language immersion, or other Estonian medium schools with an in-depth focus on alternative languages (EIM, 2020, p. 20).

On the other hand, there is a certain resistance on the behalf of the Estonian schools who are trying to protect the Estonian language environment in the areas highly populated by the minority. Due to school classes being formed on the basis of language of instruction, it is frequent for Estonian and Russian speaking children to rarely meet in classes or sometimes even in a single school. A relatively recent problem in the Estonian language medium schools in Ida-Virumaa is an influx of Russian speaking pupils (RUS.ERR, 2019). With a large number of children speaking Russian as a native tongue, these schools have insufficient resources to guarantee the quality of education and the Estonian language environment. This problem concerns not only the schools of Ida-Virumaa, but also Russian schools in all major cities such as Tartu and Tallinn because few Estonian parents are keen on sending their children even to a language immersion school where their children learn both Russian and Estonian. Therefore, there is no consensus regarding the power position of the Russian language, but it gains the role of a contender in any case, notwithstanding the subject positions of those entering the school system.

In an analysis of print media, both content and language become equally important in shaping and framing practices. Let us take a look at how a language may manifest its power in technocratic choice as much as in politicized and contested vocabularies. Being in a power position, the Estonian media writing in the Russian language gradually and, not always consciously, updates even the language itself. There is a considerable number of words reflecting a specific Estonian institutional reality, which are not present in the Russian language: “Bolnichnaya kassa” (Больничная касса—Estonian Health Insurance Fund), “kassa po bezrabotse” (касса по безработице—Estonian Unemployment Insurance Fund), “digitalnyi” (дигитальный—digital, in opposition to the official Russian “electric” or “электронный”), etc. In these and many other cases, the power of Estonian language is not contested but even driven by the minority. Due to the institutional reality being accepted as a given, the dominance of the Estonian language is reinforced without a conscious understanding of the political nature of these repetitive actions. For example, the official Estonian regulations prescribe writing the word of the capital Tallinn with two “n”-s, while transcribing it into Russian (Таллинн). At the same time, in the official Russian language it must be written with a single “n” (Таллин). At some point the Russian authorities even argued against this to no avail, by claiming that laws of Estonia do not regulate the rules of the Russian language. Therefore, even the normalization of writing Tallinn with two n-s at the end is also an important part of symbolic power manifestation delivered through the Russian language print or internet media in Estonia.

Due to the undertaken timeframe and a specific focus on the power of words, Benedict Anderson did not concern himself with TV or radio as much as with the print media. Building parallels between different theoretical frameworks of this study, I claim that Anderson strongly focused on the standardization and the symbolic aspects of citizenship practice. He considered the action of reading the same news as a ritual, which produced the feeling of unity with thousands of people one had never met. It created an illusion of belonging or at the very least existing in the same community with similar interests and discourses:

“The significance of this mass ceremony—Hegel observed that newspapers serve modern man as a substitute for morning prayers—is paradoxical. It is performed in silent privacy, in the lair of the skull. Yet each communicant is well aware that the ceremony he performs is being replicated simultaneously by thousands (or millions) of others of whose existence he is confident, yet of whose identity he has not the slightest notion. Furthermore, this ceremony is incessantly repeated at daily or half-daily intervals throughout the calendar. What more vivid figure for the secular, historically clocked, imagined community can be envisioned?” (Anderson, 1983, p. 35).

Anderson's approach masterfully describes processes of identity formation, but at the same time he treats it as an empty box having almost no real continuity. He concentrates on his macrolevel model of analysis, where nationalism is always a product of language competition (Latin vs. vernacular, imperial European languages vs. colonial Creole languages) advanced through print capitalism and reflected in administration, bureaucracy, and education. Print media, for him, is always the means for achieving the ends in the form of an imagined community. He argues that nations are similar to children in the respect that their identity cannot be remembered, but only narrated to them by the continuing flows of information produced by print capitalism (Anderson, 1983, p. 204).

As much as I like this metaphor, I do not completely agree with it and consider it an overstatement. First, even if it is impossible to reproduce one's exact identity or state of consciousness in childhood, this does not mean that there's no continuity between different life stages and that people are completely oblivious of how they thought when they were younger. Identity and its historical continuity being an active form of engagement draws in passive subjectivities of experience, memory, longing, and sense of belonging and association. Besides, if it was so easy to narrate an identity, then being the dominant actors driving and regulating print capitalism, governments would have no problem integrating large minorities into their societies, who themselves challenge/resist/reinterpret or reevaluate claims of belonging. That would probably also result in the Russian minority sharing the same citizenship practice as the Estonian majority and this article never being written. Thus, identity is indeed narrated by print capitalism but only to an extent limited by collective memory. Besides, it would be more reasonable to consider print capitalism not as a single force, but a field of struggle, where multiple actors such as political parties, NGOs, various majority and minority interest groups, representatives of government institutions, private media editorials, journalists, bloggers, and even individuals compete for an actual narrative of identity delivered to recipients.

Second, print capitalism and identity have always been engaged in a mutually constitutive relationship. Even though print capitalism facilitated modern nationalism (or the form of it that we know from the 19th century), the content of the actual identity largely depended on the specific circumstances of the nations where it arose. This is not to say that print capitalism in itself is a sole “basis” through which identity comes to be constituted, but rather, that it is embedded in a larger relational schema of politics, history, discourses, and ideas—which facilitate the rise and fall of certain dialects/languages and attitudes in the media.

Media, citizenship, and the war in Ukraine

The Russian speaking Internet media in Estonia is represented by multiple sources, however the two largest of them act as the primary agents of print capitalism influencing the minority community. First is the oldest web portal's name is Rus.Delfi (2022), which is in fact a multilingual network of portals. The Estonian language version of the portal was launched in 1999 along with the Latvian language one. The number of browser contacts (views from a single opened browser) for Rus.Delfi fluctuates around 300–400 thousand views per week. Second, another portal, which constantly contests the title of the most popular Russian speaking news source in Estonia, is Rus.Postimees (2022). This portal is a Russian language version of the largest and the most popular Estonian newspaper established in 1886. During the 1990s, Postimees once again became a national Estonian paper and, between 2005 to 2016 issued a Russian language paper version. Since 2016, it has a news portal only. At the moment, the number of browser contacts fluctuates weekly, with the winner of most visited website changing frequently.

Both portals are an integral part of Estonian print-capitalism, which in contrast, with Rus.ERR (Russian version news outlet of the Estonian national TV and Radio company), are commercial institutions having private owners whose task and vision go beyond simply informing the population. They are both independent, compete for the media market, and serve as natural counterweights to the Russian news portals from Russia by propelling the Estonian mainstream narrative and acting as tools for internalizing the identity of Russian minority in Estonia. However, as we can see from the Estonian Integration Monitoring data, minority residents tend to be much more inclined toward local identities than toward the national one. For example, when asked to rate being informed about the events of their hometown during the last 5 years, minority respondents proved to be more informed about local news than about national news, while for majority members the picture is the other way around (EIM, 2020, p. 72).

In the previous chapter I argued that rather than being simple identity narrators, print-capitalist media sources are influenced by their readers, as much as the other way around. The narratives distributed by Rus.Delfi and Rus.Postimees are constantly being shared, contested, integrated into, or rejected from identities on a personal level. After multiple rounds of internalization (as described in the section on micro and macro identities) and standardization (as in the section on the imagining communities) these narratives are rooted in the ethnopolitical field as subject positions (as described by Vetik). Even if a reader's subject position is entirely different from the mainstream narrative, it is still situated within the field. In most of the cases even the vocabulary used by the competing narrative is not contested in terms of language or content. For example, when covering the issue of Narva tank, both the Estonian mainstream news and their Russian counter-parts used the same construction of “moving the Narva tank,” in Estonian “Narva tanki teisaldamine” and in Russian “Перенос Нарвского танка” Even the opponents of this measure did not use more assertive terms such as “sacrilege”, “destruction”, “vandalizing”, or even “removal.” Therefore, even the competing narratives were united by the sheer fact that the tank was simply “moved.”

I argue that this strongly reflects the symbolic aspect described by Anderson. The practice of repetitive reading of the same news from the same portals and sharing or arguing over the discourse distributed by familiar media sources creates a strong sense of belonging. However, for this sense to arise the print-media field should have a limited number of options and community members need to trust them. Internet media is much more accessible than a print newspaper and easily provides nation-wide coverage while generating a high level of trust. Russophones in Estonia clearly illustrate how this specifically works. According to EIM (2020) 72% of minority respondents named the Estonian Russian language news portals as a third important source of information outranked only by information from friends and relatives (89%) and colleagues/fellow students (75%) (EIM, 2020, p. 74). Therefore, I argue that studying the influence of selected media outlets allows us to perfectly capture the dominant political discourses of the Russian minority community in Estonia.

For the purpose of this work, I analyze the quantitative sample, which includes 9 986 articles from Rus.Delfi and 9 935 articles from Rus.Postimees for the period from 13.11.2021 to 18.04.2022, capturing the time before and after the war in Ukraine. The raw data was collected using four Python scripts scanning and processing information from the search pages of Rus.Delfi and Rus.Postimees. The first script scanned the websites for specific dates and extracted all the links, which were then stored in a table. The second script retrieved the texts of articles saving them and the dates when they were written. The third script performed tokenization of the saved articles, meaning breaking the saved texts into individual words, and then lemmatization, or the process of converting each word to the base form and then saving the resulting data in a separate table. Finally, the fourth script searched for identical words, counted their occurrences, and recorded the results in a separate table. This large sample size provides a comprehensive and representative view of the citizenship vocabulary of the Russian-speaking media in Estonia, enabling the identification of primary themes.

For processing this data, I apply theory-driven content analysis to examine the most frequently used words in the articles. The analysis employs Isin's concept of ruptures and reveals them across different dimensions, such as space, time, formal citizenship, language, ethnicity, and major events such as the war in Ukraine. Therefore, coding and grouping were conducted along those theoretical lines. Drawing from Anderson, I demonstrate how the mutually constituted media citizenship vocabulary shapes the readers' perception of these ruptures, defining a shared experience for them to imagine their identities. On the one hand, this approach does not allow for a detailed examination of the actual reactions to the media discourse per se. On the other hand, to outline the citizenship practices, the analysis of their vocabulary is more important, as these words serve as a container for multiple pro and contra subject positions. In other words, the acceptance or rejection of identities occurs in the terms formulated within the ruptures. Moreover, faced with the situation where the interests of a considerable part of the Russian minority conflict with the mainstream political agenda, we may observe how the media outlets function not only as separate actors informing the population but also as respondents, activists, or mutual translators, interpreting not only the actions of government to the general public but also vice-versa.

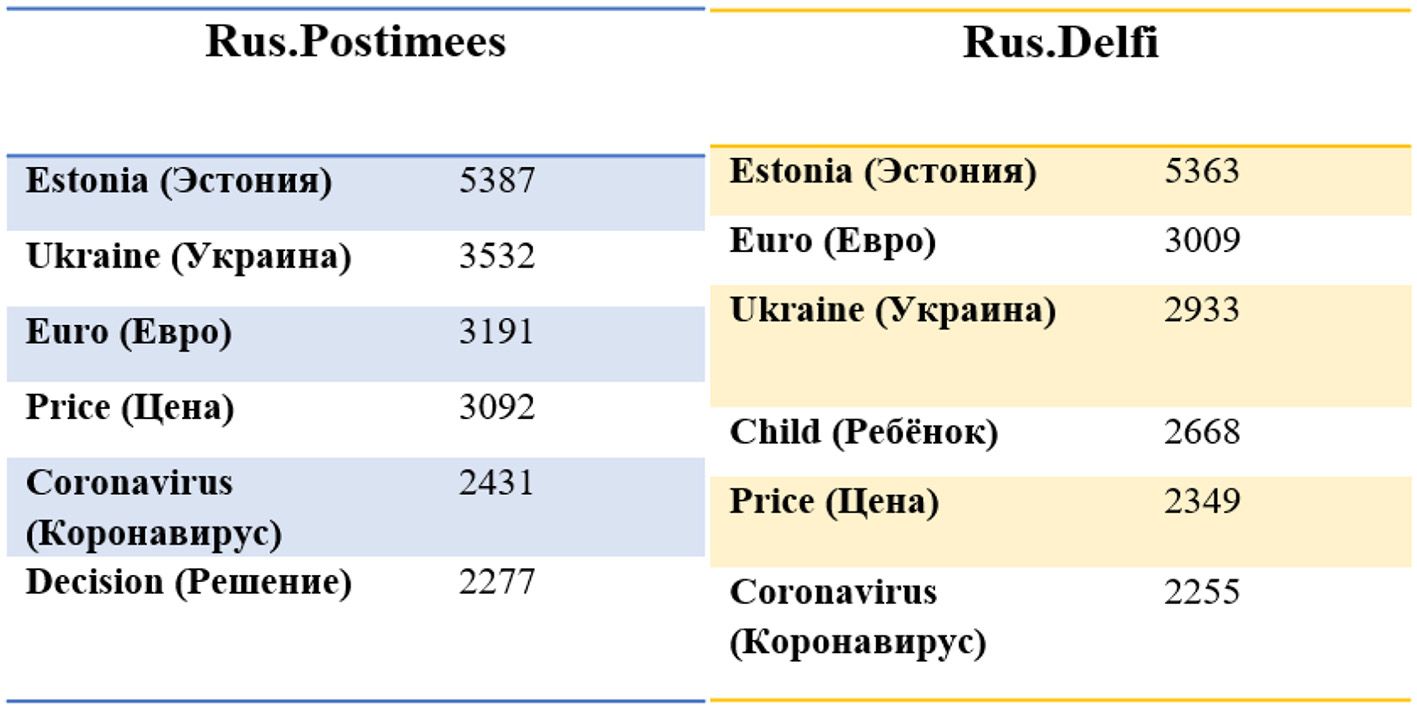

The war in Ukraine has drastically changed the discourse of the analyzed media outlets. From Figure 1 we may observe that 3 months before the war, even as the trouble that was brewing in Ukraine held much of the country's attention, the discourse of both portals was mostly focused on Estonia and its internal affairs: there were 5,387 mentions of Estonia for Postimees and 5,363 for Delfi. The overlapping themes were also focused on prices, stability of the Euro and coronavirus. We may also observe that Rus.Delfi also prioritized children in its coverage even before the war.

Figure 1

The top 6-word mentions before the start of the war in Ukraine (13.11.2021–23.02.2022).

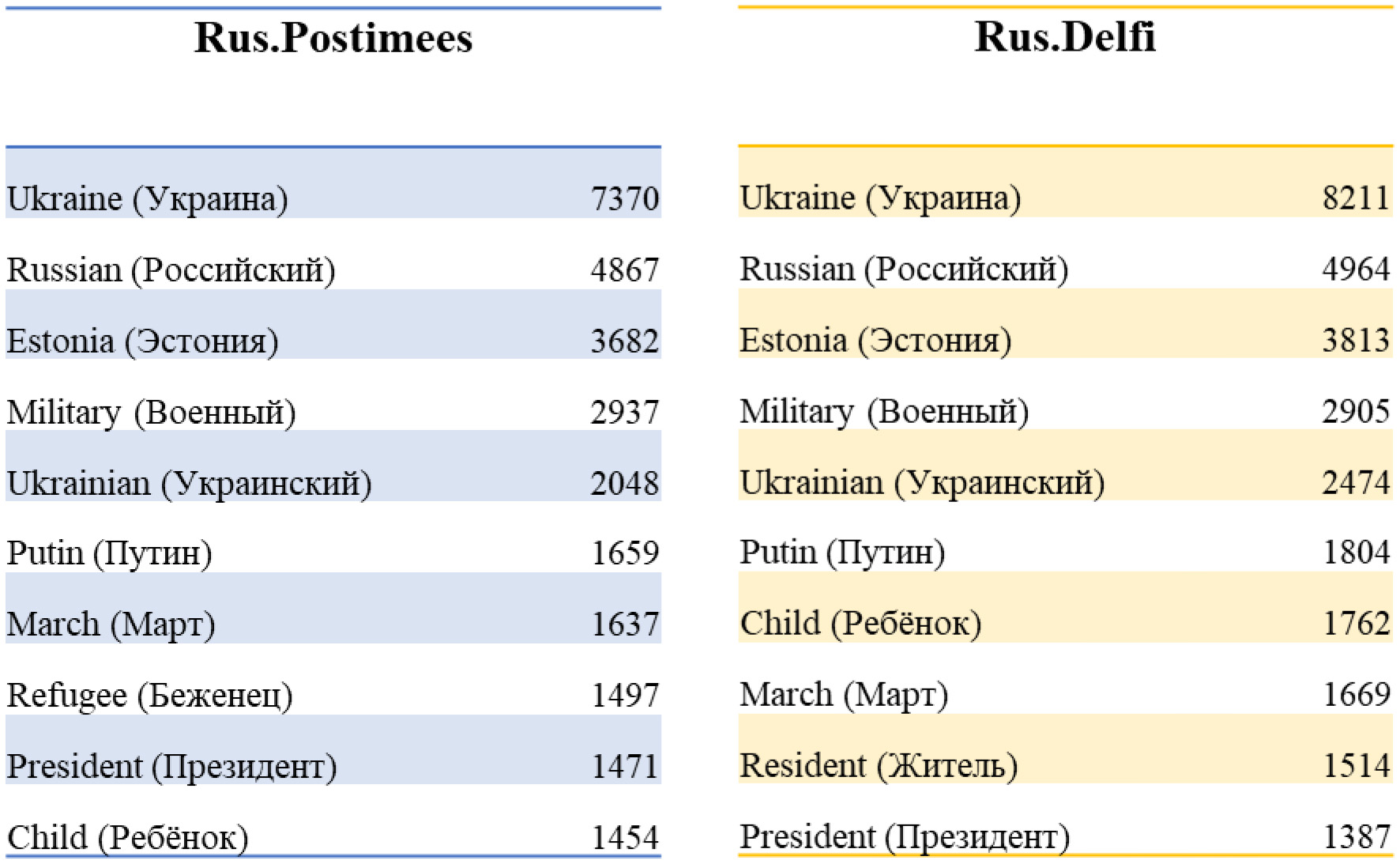

As we can see from Figure 2, after the start of the war, the top 6 words become identical in both of the portals: Ukraine, Russian, Estonia, Military, Ukrainian, and Putin. The shock of the horrifying Russian assault on Ukraine was so strong that it did not just capture the whole of media discourse, but to a certain extent, it even synchronized the vocabulary of both media outlets. Let us take a look at the empirical evidence supporting this statement (from now on Rus. Postimees will be referred to as PM and Rus.Delfi as D). Approaching the end of the most violent phase of the Russian offensive, both portals had similar mentions of the word March (PM: 1,637 and D: 1,669) and focused on the actions of the word leaders, explain why the word President is frequently mentioned (PM: 1,471 and D: 1,387). Rus.Postimees has also started to actively cover the issues of refugees (1,497) and children (1,454). Rus.Delfi kept the focus on children (1,762), but despite devoting significant attention to refugees (1,264 mentions), it was also more focused on residents (1,514): Ukrainian and local.

Figure 2

The top 10-word mentions after the start of the war in Ukraine (24.02.2022–18.04.2022).

From both sides of the theoretical framework of this study, the war in Ukraine has remarkably changed the citizenship practices of the Russian minority in Estonia. Aside from introducing the rupture between followers of the Kremlin's narrative and the independent news, the detailed analysis of which goes beyond the scope of this article, the war in Ukraine has subtly become a component of citizenship itself. Tracking the news about the war has become as much of a practice for readers, as writing about it for journalists and bloggers (Netpeak Checker, 2022). It is certainly not the first time that a subject position toward a war becomes a part of identity, but what makes this particular war different for Estonia is on the hand, the absence of an active involvement in combat, and on the other hand, a continuous and circulating information flow about the war, which challenges existing memories and identities and constantly raises the question of loyalty. No matter how we look at it: as Anderson's mass ceremony of simultaneous media consumption or Isin's collective act of citizenship, this results in the reimagining of the existing identities of Estonian Russians. As this process is currently continuing, it is too early to say how these identities will eventually look.

Mapping fragmented citizenship practices

The vocabulary of Estonian minority citizenship practices would not be complete, if we did not try to describe the four primary components it consists of: space and location, formal (legal) citizenship, language and ethnicity.

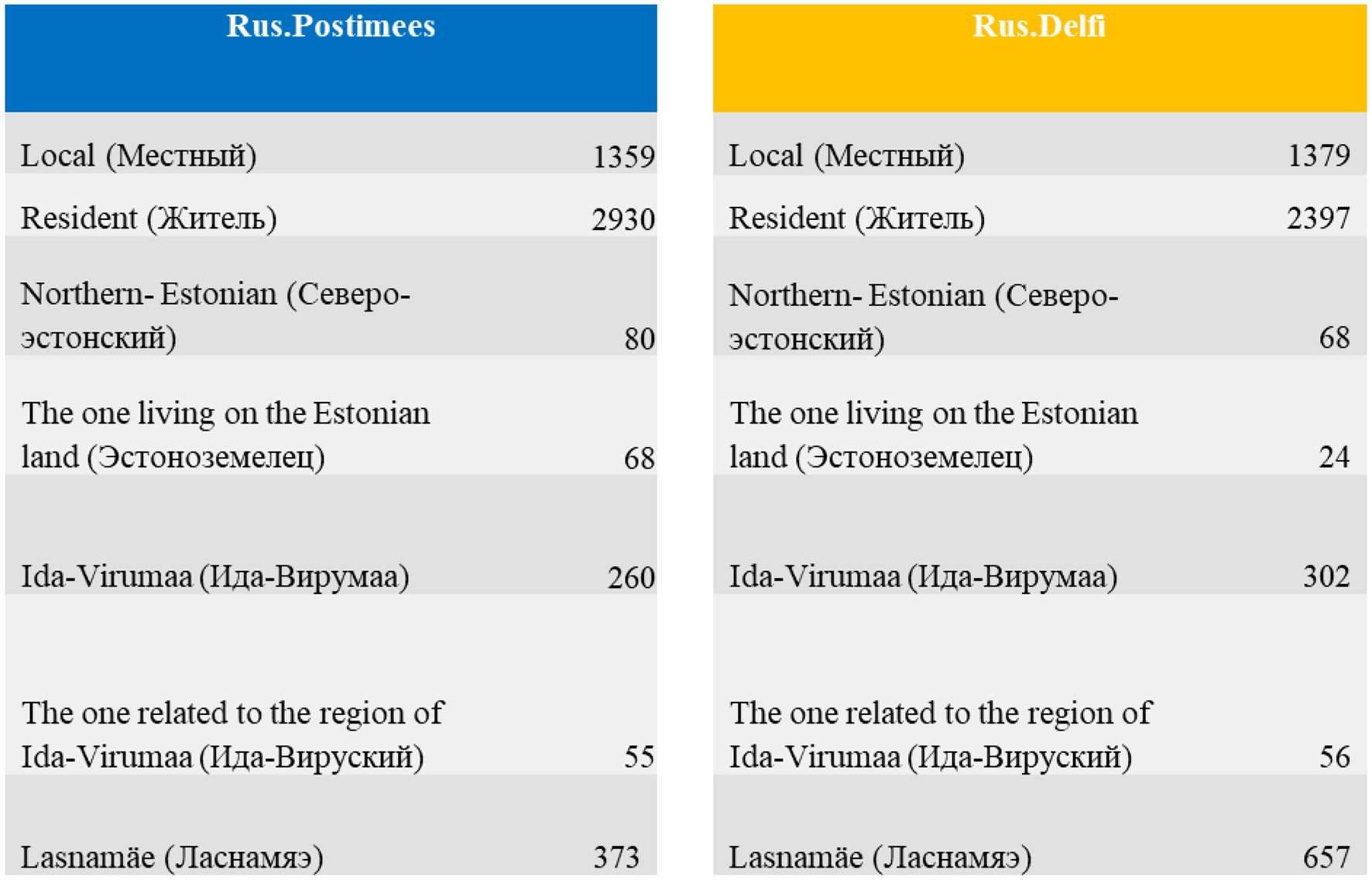

Contrary to the Estonian language-centered integration model, media discourse is emphatically regional. As we can see from the Figure 3, the word combinations of “local” (PM: 1,359, D: 1,379) and “resident” (PM: 2,930, D: 2,397) are widely used in characterizing identities. The geographical component is also visible in an extensive thematic focus on the minority populated areas, such as the region of Ida-Virumaa (PM: 315, D: 358, counting adjective forms) or the Lasnamäe district in Tallinn (PM: 373, D: 657). Another visible trend is a rather modest usage of a politically correct word form aiming to unite all Estonian residents “Estonozemelets” in Russian or “Eestimaalane” in the Estonian language (the one living on the Estonian land). Due to the large presence of minority members having foreign or no citizenship, the Estonian political elite tried to propose a land-based identity, which proved to be a rather contested substitute to legal or ethnic types of identities. Devoid of the imagining act, the term of “Estonozemelets” does not serve its primary purpose and instead of uniting the minority and majority, it stresses the existing status-quo of living in the same space. That is why even the mainstream internet portals do not use this term often (PM: 68, D: 24) in comparison with the regional denominators.

Figure 3

Word frequencies characterizing the space and location aspect of Russian minority identity.

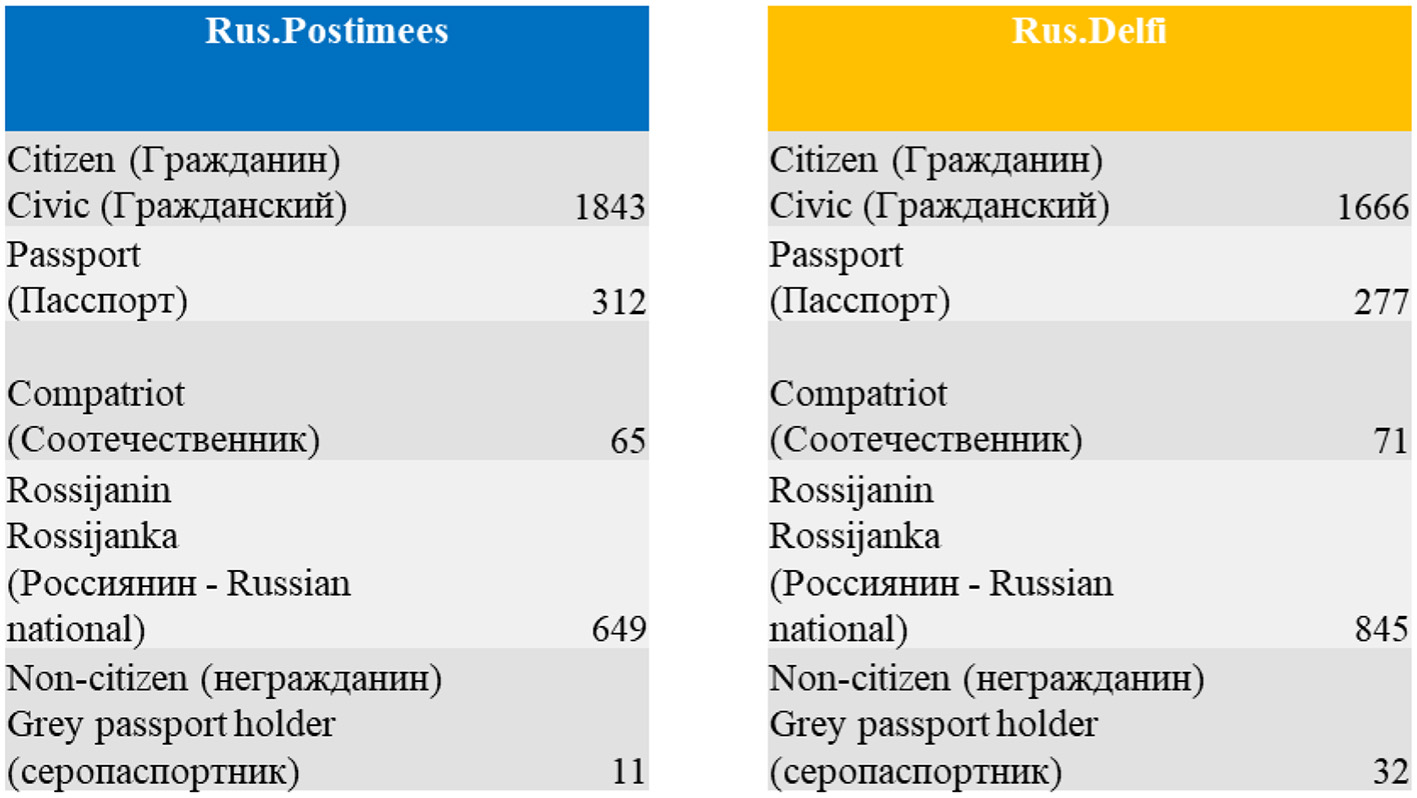

Legal status has become one of the primary stepping stones in identity differentiation. From Figure 4 we can see the following trends. First, we may observe the increased importance of the standard legal form of identity, which is rooted in words such as citizen and civic (PM: 1,843, D: 1,666). Also, due to historical developments, a popular manner of referral includes the word passport (PM: 312, D: 277) and adding an adjective red, blue or gray. Even though Estonian passports changed their color to red long time ago, in colloquial speech a red passport may often mean a Russian one, and a gray passport is way to refer to a person without citizenship. Second, as the Estonian authorities keep introducing new ways to sanction Russian passport holders, it has become of higher importance for both the mainstream media and ordinary Estonian minority readers to draw an additional line between themselves and “rossijane” (Russian nationals) (PM: 649, D: 845), meaning Russian nationals, but also having a connotation of those hailing from or residing in Russia. The frequent emphasis on the actions of “rossijane” emphasizes an attempt to further separate this identity from that of the local community. This stands in contrast to use of the word “russkiy”, which means an ethnic Russian. Finally, we see that attention on Estonian non-citizens has plummeted (PM: 11, D: 32). Considering that multiple researchers investigating the issue of minority citizenship in Estonia often focus on gray-passport holders, this trend signifies a large difference between a mainstream research and an insider perspective on the issue.

Figure 4

Word frequencies characterizing the legal aspect of Russian minority identity.

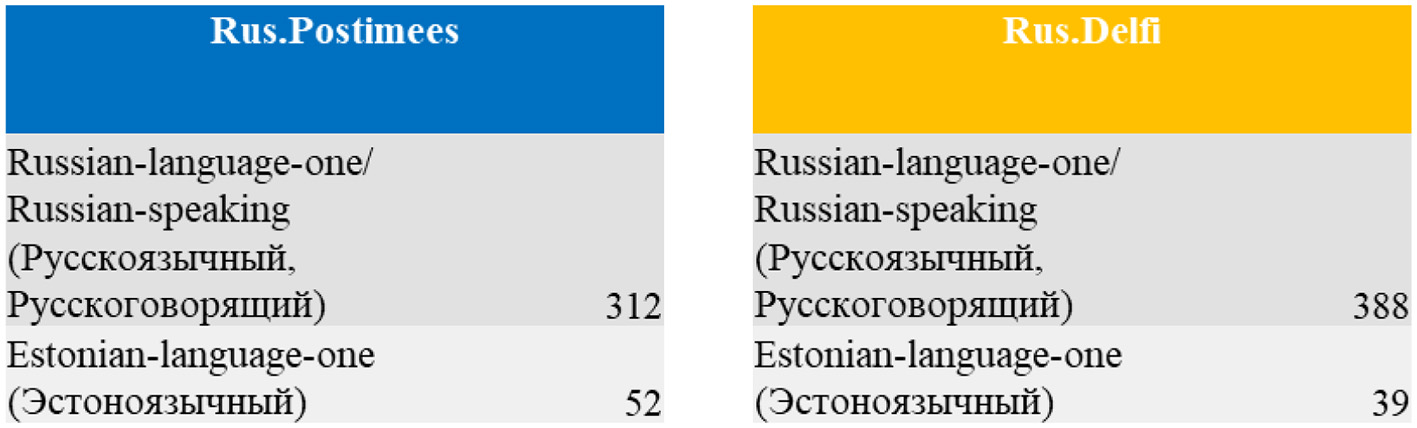

Integration monitoring asserts that the Estonian model of integration prioritizes the Estonian language as a primary tool for integration (EIM, 2020, p. 102). Looking at the data from the analysis, we may find additional support for this argument. Even discarding the contaminated data, in which it is impossible to differentiate between ethnicity and language, we can see from Figure 5 that linguistic indicators play an important part in identity construction. The “Russian-language-one” is a quite popular form designating a resident (PM: 312, D: 388). However, even though the Estonian-language-one (PM: 52, D: 39) is not as frequent, it demonstrates the dominating position of the Estonian language in society, as it reflects that people prioritize the word “Estonian” instead (PM: 3,002, D: 2,940). The intricate form of an adjective, “Russian-speaking-one,” is an attempt to further differentiate the language and ethnic aspects of the word “Russian.” Using this model of perception, the Russian-speaking resident of Estonia is much more integrated into society than the “Estonian Russian,” which brings in an ethnic aspect and more political subjectivity, similar to “African American.”

Figure 5

Word frequencies characterizing the legal aspect of Russian minority identity.

Adding the final strokes to this picture of the citizenship vocabulary of the Russian language web-portals of Estonia, I would like to highlight two more features. First, the theme of “discrimination” is present, but far from persistent (PM: 47, D: 78). Despite clear problems with the securitization of the Russian identity, this has not yet fully affected the minority community, which prefers the opposition strategy of differentiation, or distancing itself further from Russia and Russian nationals not just via legal status, but on the level of the discourse as well. Second, the dominating media discourse shows that the Russian minority of Estonia has accepted a one directional narrative of integration. In this narrative the non-majority members constitute an element that needs to be integrated (PM: 38, D: 40) rather than integrate itself (PM: 9, D:12). All of this shows that the Russian minority identity is currently in transition, the final result of which is yet to be seen.

Conclusions

The relational framework provides a researcher with multiple theoretical tools serving to engage with rich empirical material, such as that provided by the Estonian ethnopolitical field. In this sense the following article is an attempt to think along not only with Isin, but also Anderson, Vetik, Tajfel, and many other scholars. By employing relational language, I strive as much as possible to find the balance between objectivism and subjectivism and transcend nominal binaries and essentialism. Instead of treating groups as the real entities, I consider the subject positions constituting the ethnopolitical field of Estonia. I trace how citizenship becomes a fluid nexus between a status and practice for minorities. I observe how language gains power through print media and becomes involved in a constitutive relationship with identity, becoming a narrator as much as a listener. In this light, the act of citizenship fades into the background, exposing the ruptures of citizenship practice in Estonia.

The linguistic, geographical and formal status ruptures find their reflection in media narratives, forming patches of identities. Space and location become salient in the regional vocabulary, while the uniting mainstream identity based on land finds little support. Language rupture serves as an identity tool, where the Estonian language affirms its dominating position in the narrative. The weakness of shared citizenship practice encourages grouping along the lines of legal status, where Russian nationals become ostracized in the narrative, while non-citizens almost disappear from the discourse. In turn, the minority's subject position normalizes the language of integration narrative becoming primarily one-directional and inclining toward being integrated, rather than integrating itself.

The war in Ukraine has inflicted a new rupture upon citizenship practice, causing securitization and polarizing identities. In the new conditions, the Russian minority is driven into finding ways to prove its loyalty and rethink its historical contributions and its current role in the Estonian society. Even though the act of the Narva tank relocation and comparison of its significance with the Bronze soldier removal deserves a separate paper, in light of the rest of this analysis, it gives us an exact idea of how the war in Ukraine may manifest itself as a rupture in Estonian citizenship practices. As for now, the identity of the Russian minority remains fragmented and finding common citizenship practices with the Estonian majority is a task yet to be undertaken.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Anderson B. (1983). Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism.London: Verso.

2

Balti Uuringute Instituut Tallinna Ülikool SA Poliitikauuringute Keskus Praxis (2020). Eesti ühiskonna integratsiooni monitoring [The integration monitoring of the Estonian society]. Tallinn: Kultuuriministeerium. Available online at: https://www.kul.ee/en/estonian-integration-monitoring-2020 (accessed June 10, 2022).

3

Bigo D. (2006). “Globalized (in)security: The field and the ban-opticon,” in Illiberal practices of liberal regimes: The (in)security games, eds. D. Bigo and A. Tsoukala (Paris: L'harmattan) 5–49.

4

Bourdieu P. (1985). The social space and the genesis of groups. Theory Soc.14, 723–744. 10.1007/BF00174048

5

Castelló E. (2016). Anderson and the Media. The strength of “imagined communities”. Debats. J. Cult. Power Soc.1, 59–63. 10.28939/iam.debats-en.2016-5

6

Csergo Z. (2008). Review essay: Do we need a language shift in the study of nationalism and ethnicity? Reflections on Rogers Brubaker's critical scholarly agenda. Nations Nation.14, 393–398. 10.1111/j.1469-8129.2008.00346.x

7

David O. Bar-Tal D. (2009). A sociopsychological conception of collective identity: The case of national identity as an example. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev.13, 354–379. 10.1177/1088868309344412

8

Eesti Entsükloopedia (2012). Rahvuskoosseis Eestis. [National composition of Estonia]. Available online at: http://entsyklopeedia.ee/artikkel/rahvuskoosseis_eestis (accessed May 30, 2022).

9

Ehala M. (2009). The bronze soldier: Identity threat and maintenance in Estonia. J. Baltic Stud.40, 139–158. 10.1080/01629770902722294

10

Ehala M. (2018). Signs of Identity: The Anatomy of Belonging. NY: Routledge. 10.4324/9781315271439

11

Fein L. C. Straughn J. B. (2014). How citizenship matters: narratives of stateless and citizenship choice in Estonia. Citizenship Stud.18, 690–706. 10.1080/13621025.2014.944774

12

Isin E. (2002). Being Political: Genealogies of Citizenship.Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

13

Isin E. (2009). Citizenship in flux: The figure of the activist citizen. Subjectivity29, 367–388. 10.1057/sub.2009.25

14

Jašina-Schäfer A. Cheskin A. (2020). Horizontal citizenship in Estonia: Russian speakers in the borderland city of Narva. Citizenship Stud. 24, 93–110. 10.1080/13621025.2019.1691150

15

Kruusvall J. Vetik R. Berry J. W. (2009). The strategies of inter-ethnic adaptation of Estonian Russians. Stud. Transit. States Soc.1, 3–24. Available online at: http://htk.tlu.ee/stss/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/STSS_Kruusvall_Vetik_Berry.pdf

16

Makarychev (2019). Estonia's Russophones Tumble Between Two Populisms. PONARS Eurasia. Available online at: https://www.etis.ee/Portal/Publications/Display/12f51974-3d7c-48f8-bccc-9cf24c1c81d4 (accessed July 3, 2022).

17

Netpeak Checker (2022). SEO website analytics. Available online at: https://netpeaksoftware.com (accessed September 28, 2022).

18

Õhtuleht (2022). Peaminister Kallas Narvas: tank tuleb teisaldada kiiremini kui kahe nädalaga. Prime-minister Kallas in Narva: The tank should be relocated quicker than in two weeks. Available online at: https://www.ohtuleht.ee/1067721/peaminister-kallas-narvas-tank-tuleb-teisaldada-kiiremini-kui-kahe-nadalaga (accessed September 16, 2022).

19

Pettai V. (2006). Explaining ethnic politics in the Baltic States: Reviewing the triadic nexus model. J. Baltic Stud.37, 124–136. 10.1080/01629770500000291

20

Riigikogu (2020). The Riigikogu passed the Statement “On Historical Memory and Falsification of History”. Press Releases. Available online at: https://www.riigikogu.ee/en/press-releases/plenary-assembly/riigikogu-passed-statement-historical-memory-falsification-history/ (accessed July 4, 2022).

21

Rus.Delfi (2022). The official website of the Russian version of Delfi. Available online at: https://rus.delfi.ee/ (accessed August 8, 2022).

22

RUS.ERR (2019). Estonian schools cannot handle the influx of Russian pupils (in Russian).

23

RUS.ERR (2022a). Reform gets behind stripping Russian citizens of right to vote. Available online at: https://news.err.ee/1608721012/reform-gets-behind-stripping-russian-citizens-of-right-to-vote (accessed September 19, 2022).

24

RUS.ERR (2022b). Russian students: 'We can't go back to Russia because we support Ukraine'. Available online at: https://news.err.ee/1608683119/russian-students-we-can-t-go-back-to-russia-because-we-support-ukraine (accessed August 13, 2022).

25

RUS.ERR (2022c). Russian, Belarusian citizens will not be allowed to own firearms in Estonia. Available online at: https://news.err.ee/1608658276/russian-belarusian-citizens-will-not-be-allowed-to-own-firearms-in-estonia (accessed August 3, 2022).

26

Rus.Postimees (2022). The official website of the Russian version of Delfi. Available online at: https://rus.postimees.ee/ (accessed August 8, 2022).

27

Statistics Estonia (2022). Population by ethnic nationality (RV0222U: Rahvastik soo, rahvuse ja maakonna järgi). Available online at: https://andmed.stat.ee/et/stat/rahvastik__rahvastikunaitajad-ja-koosseis__rahvaarv-ja-rahvastiku-koosseis/RV0222U (accessed September 16, 2022).

28

Tajfel H. (1978). “Social categorization, social identity, and social comparison,” in Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations, ed. H. Tajfel (London: Academic Press) 61–76.

29

Tajfel H. Turner J. C. (1986). “The social identity theory of intergroup behavior,” in Psychology of Intergroup Relation, eds. S. Worchel, and W. G. Austin (Chicago: Hall Publishers) 7–24.

30

Vetik R. (2012). Nation-Building in the Context of Post-Communist Transformation and Globalization. New York, NY: Peter Lang Press. 10.3726/978-3-653-01615-4

31

Vetik R. (2019). National identity as interethnic (de) mobilization: a relational approach. Ethnopolitics18, 406–422. 10.1080/17449057.2019.1613065

Summary

Keywords

social identity, Estonia, minority identity, media analysis, nation building, relational approach, discourse, Russian minority

Citation

Polynin I (2023) Patching identity. How Russian language media in Estonia reconstitutes our understanding of citizenship. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1140084. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1140084

Received

08 January 2023

Accepted

27 March 2023

Published

20 April 2023

Volume

5 - 2023

Edited by

Ian A. Morrison, American University in Cairo, Egypt

Reviewed by

Greg Nielsen, Concordia University, Canada; Helga Kristin Hallgrimsdottir, University of Victoria, Canada

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Polynin.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ivan Polynin ivan.polynin@tlu.ee

This article was submitted to Political Participation, a section of the journal Frontiers in Political Science

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.