- 1Department of Political Science, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium

- 2Department of Politics and International Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Warwick, Coventry, United Kingdom

- 3School of Psychology, University of Sussex, Sussex, United Kingdom

- 4Sociology Department, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium

In recent years, deliberative democracy has drawn attention as a potential way of fighting polarization. Allowing citizens to exchange arguments and viewpoints on political issues in group, can have strong conflict-mitigating effects: it can foster opinion changes (thereby overcoming idea-based polarization), and improve relations between diametrically opposed groups (thereby tackling affective forms of polarization, such as affective polarization). However, these results conflict with social psychological and communication studies which find that communicative encounters between groups can lead to further polarization and even group think. The question therefore arises under which conditions deliberative interactions between citizens can decrease polarization. Based on a multidisciplinary systematic review of the literature, which includes a wide diversity of communicative encounters ranging from short classroom discussions to multi-weekend citizen assemblies, this paper reports several findings. First, we argue that the effects of communicative encounters on polarization are conditional on how those types of communication were conceptualized across disciplines. More precisely, we find depolarizing effects when group discussions adhere to a deliberative democracy framework, and polarizing effects when they do not. Second we find that the depolarizing effects depend on several design factors that are often implemented in deliberative democracy studies. Finally, our analysis shows that that much more work needs to be done to unravel and test the exact causal mechanism(s) underlying the polarization-reducing effects of deliberation. Many potential causal mechanisms were identified, but few studies were able to adjudicate how deliberation affects polarization.

1. Introduction

Polarization is increasingly seen as one of the main threats to the future of democracy (Carothers and O'Donohue, 2019; Orhan, 2022). Although the evidence on the potentially detrimental effects of the different forms of polarization (e.g., idea-based vs. affective polarization) is still emerging and consequently being debated (Ruggeri, 2021; Broockman et al., 2022; Voelkel et al., 2023), it seems that the future of strong and resilient democracy is directly challenged by polarizing dynamics. After all, previous research has established polarization's connection to various negative outcomes, including a decline in support for democratic values (Kingzette et al., 2021), biased treatment based on political affiliation (Westwood et al., 2018), political factionalism (Finkel et al., 2020), heightened social detachment (Iyengar et al., 2019), and an erosion of democratic systems (McCoy et al., 2018; McCoy and Somer, 2019; Orhan, 2022).

Even though this research agenda on polarization and its adverse political consequences and broader relationship with democracy has been prolific in recent years, empirical research on potential cures for polarization has only recently started to emerge (see e.g., Levendusky, 2018; Warner et al., 2020; Wojcieszak and Warner, 2020; Huddy and Yair, 2021; Hartman et al., 2022; Simonsson et al., 2022), and apart from interventions in controlled research environments, real-life depolarization initiatives have not yet been successfully deployed. While several solutions have been proposed, such as imposing social media regulations, fostering inclusive online spaces, or installing opposing viewpoint buttons (see e.g., Fagan, 2017; Sunstein, 2017; Persily and Tucker, 2020), most of them have remained primarily theoretical endeavors and thought experiments.

One notable exception, however, is the literature on deliberative democracy, which in its varied forms is considered a potential cure for political polarization (see e.g., Esterling et al., 2021; Fishkin et al., 2021; McAvoy and McAvoy, 2021). By allowing citizens to exchange arguments and viewpoints on political issues in group, processes of communicative interactions can have strong conflict-mitigating effects: they can foster opinion changes (thereby overcoming idea-based polarization) (Grönlund et al., 2015; Smith and Setälä, 2018), and improve relations between diametrically opposed groups (thereby tackling affective forms of polarization) (Gastil et al., 2010). This leads Dryzek et al. (2019; p. 1143) to conclude that:

“[d]eliberation can overcome polarization. The communicative echo chambers that intensify cultural cognition, identity reaffirmation, and polarization do not operate in deliberative conditions, even in groups of like-minded partisans. In deliberative conditions, the group becomes less extreme; absent deliberative conditions, the members become more extreme.”

Research on this topic has gained momentum in recent years, and there are solid reasons to assume that deliberation could reduce polarization (see e.g., Grönlund et al., 2015; Strandberg et al., 2019). However, these results conflict with social psychological and communication studies which find that communicative encounters between individuals can lead to further polarization and even group think. For instance, research on group decision-making as far back as the 1970's (Myers and Lamm, 1976; p. 603; see also Lamm and Myers, 1978) has found that when individuals convene in groups to discuss collective issues and come up with recommendations, their decisions were usually more extreme than what each of the individuals preferred (Forsyth, 2010; p. 333–334, see also Sunstein, 2000, 2002, 2009). As those forms of group discussions arguably differ from deliberation within a deliberative democracy framework, the question is then no longer whether group deliberation reduces polarization, but rather which conceptualizations of deliberation can have these effects.

Against this background, this paper aims to take stock of the research on deliberation and polarization across multiple disciplines. Based on the systematic review, which includes a wide diversity of communicative encounters ranging from short classroom discussions to multi-weekend citizen assemblies, this paper reports several findings. First, and in line with the contradictory findings of previous studies, we argue that group discussions do not consistently reduce polarization. Rather, we argue that the effects of communicative encounters on polarization are conditional on how those types of communication were conceptualized across disciplines. More precisely, we generally find depolarizing effects when group discussions adhere to a deliberative democracy framework, and more frequent polarization effects when they do not. Secondly, we also find that depolarizing effects depend on a number of contextual factors. In particular, design factors that are often implemented in deliberative democracy studies, such as group composition, facilitation, and interaction mode, are positively associated with depolarization. In other words, deliberation seen as a form of organized group decision-making with specific design features as advocated in the field of deliberative democracy, does indeed decrease polarization; but other forms of group discussion with less stringent design factors increase polarization. This confirms the argument of Dryzek et al. (2019) that deliberative democracy designs can decrease polarization. Finally, our analysis also shows that much more work needs to be done to unravel the exact causal mechanism(s) underlying the polarization-reducing effects of deliberation. We found that many potential causal mechanisms were identified, but few studies were able to test and adjudicate in which way deliberation affects polarization levels.

In the remainder of this paper, we first discuss the methodology of our systematic review and the characteristics of the sample. In the third section, our paper discusses the widely diverging conceptualizations of deliberation and polarization, before moving on to the potential effects of deliberation on polarization. The next section analyses the deliberative design characteristics that can potentially be linked to increasing or decreasing levels of polarization. We conclude by identifying potential causal mechanisms.

2. Research design, data, and methods

2.1. Selection process and inclusion criteria

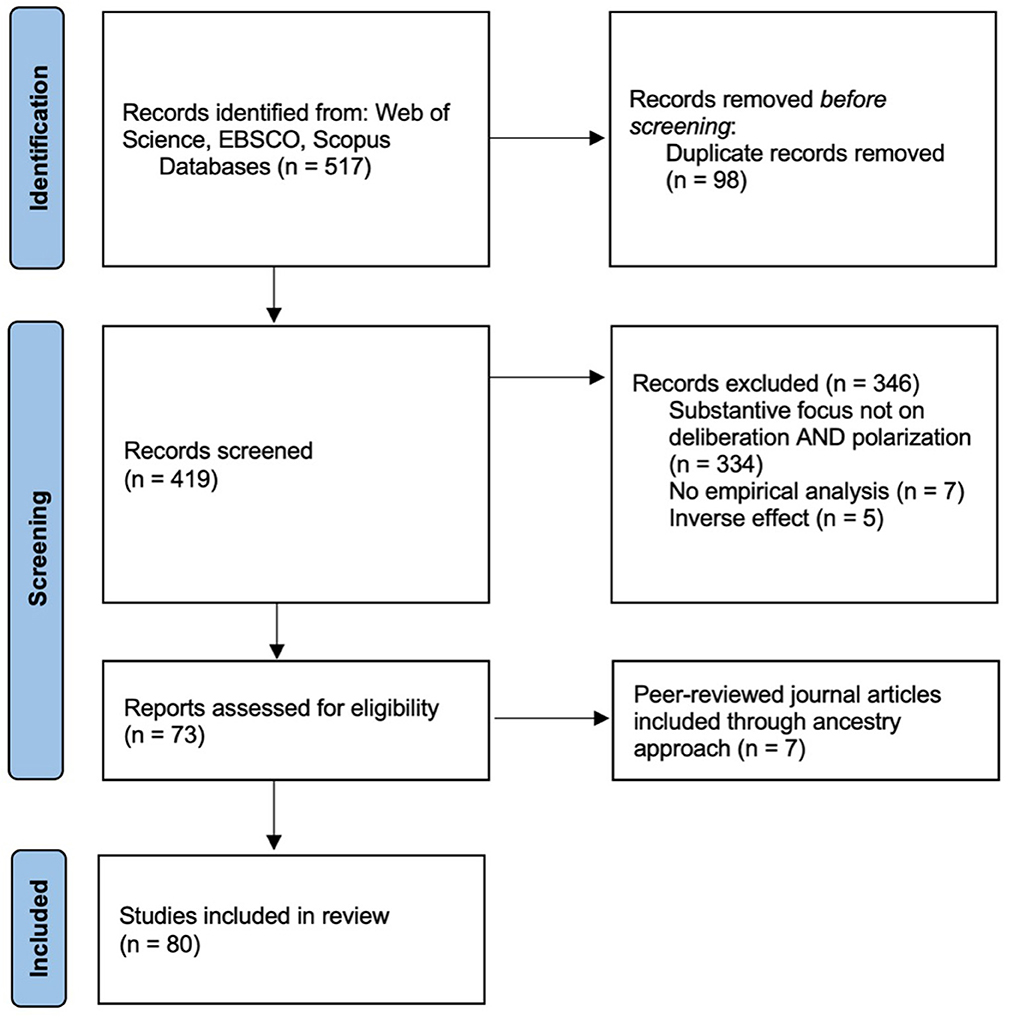

To study the complex relationship between deliberation and polarization, we conducted a systematic review of published studies following the standardized PRISMA protocol (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) (Moher et al., 2009) (see flowchart in Figure 1). An initial set of relevant publications was identified through a search process on Web of Science, Scopus and EBSCO, three databases containing primarily peer-reviewed articles in top-rated international journals, but also book chapters. The articles and chapters are predominantly published in English. In order to map the corpus of relevant publications, we searched for the following set of terms in the article titles, abstracts, or author keywords (date of the search: 18 November 2022):

“deliberation,” “deliberative,” “mini-public/s,” “minipublic/s,” “citizen assembly/ies,” “planning cell/s,” “citizen forum/s,” “deliberative poll/s,” “citizen panel/s,” “issue forum/s,” “group discussion,” “group talk,” “group decision-making,” OR “political talk”

in combination with “polariz/sation,” “polariz/sed,” “partisan/partisanship,” “sorting,” “divide/ision,” “disagreement” OR “extremiz/sation” (AND operator used)

As mentioned above, and as is clear from the list of search terms, we did not limit ourselves to only reviewing articles that study the strict Habermasian type of communicative action between citizens. We took a broad view on deliberation, going beyond the mere field of deliberative democracy, and including phenomena from communication studies and social psychology. Although not all these definitions meet the Habermasian standards of deliberation upheld by deliberative scholars, we chose to include them nevertheless for four reasons. First of all, both deliberative democracy and other disciplines rely on similar psychological mechanisms to explain why group communication leads to (de)polarization, such as biased information processing and identity theories. It might thus be interesting to check whether similar mechanisms are at play even in studies with widely diverging conceptualizations of deliberation. Secondly, broadening the conceptualization of deliberation allows us to go beyond traditional mini-public designs. This enables us to identify the diversity in conditions under which group discussion in various contexts might decrease polarization dynamics, and to understand how “rigorous” deliberation needs to be. Thirdly, deliberation is often considered as a broad concept in the deliberation literature itself (see for instance Polletta and Gardner, 2018; p. 71). Deliberation can take place in mini-publics, but also in everyday settings (Conover and Searing, 2005; Kim and Kim, 2008; Conover and Miller, 2018) or jury decision-making (Gastil and Hale, 2018). By including studies dealing with varying conceptualizations of deliberation, ranging from short experimental classroom discussions to multi-day citizen assemblies following deliberative democracy formats, we acknowledge that deliberation takes place in many instances and in many forms. Finally, even though many recent studies rely on deliberative mini-publics, few of them actually assess the quality of deliberation. In other words, there is an assumption that gathering citizens in well-designed mini-publics leads to deliberative types of communication, but few studies even in deliberative democracy scholarship measure the quality of the communication, e.g., using tools such as the (perceived) Discourse Quality Index (Caluwaerts and Reuchamps, 2014; Bächtiger and Parkinson, 2019).

Our selection criteria led to an initial set of 517 publications, of which 419 were unique publications and 98 duplicates. Of these 419 articles, we scanned the abstracts, introductions, methodological sections and conclusions to adjudicate which articles had a substantive focus on the effects of deliberation on polarization, and would therefore make it to the final selection. During this process, we used the following inclusion criteria:

1. First of all, the selected articles' substantive focus had to be on the relationship between deliberation and polarization. Many articles, especially since the early 2000's, often mention polarization or deliberation as a way of framing the issue or as a reflection on the implications of their findings on deliberation or polarization. On the one hand, some mention in their introduction that deliberation increasingly takes place in polarized political systems, but do not focus on polarization as such in the analysis. Polarization was merely used as a way of framing the context. On the other hand, some authors on polarization reflect on the implications of their findings and call for more deliberation as a potential solution, without actually including deliberation in the analysis. The publications (N = 334) in which the focus was not on the substantive relationship between deliberation and polarization, were not included in the final selection.

2. Secondly, the publications had to contain an empirical analysis of the relationship between deliberation and polarization. This means that we excluded studies making a purely theoretical argument, as well as publications relying on simulation studies, agent-based modeling, or formal models. Only studies reporting on empirical data on a wide range of deliberative encounters and polarization were included. We excluded seven studies based on this selection criterion.

3. The final inclusion criterion relates to the assumed directionality of the effects. We only selected those articles that investigated the effect of deliberation on polarization. Some studies (N = 5) reported results that referred to the opposite relationship, i.e., on the question whether increasing levels of societal/political polarization led to more engagement in, support for, or demand for deliberation and group discussion. These studies were not included in the final selection.

The application of these inclusion criteria meant that 346 publications were removed from the final selection, leading to a dataset of 73 published studies spanning a time frame ranging from 1966 to 2022. In a final step, we applied the ancestry approach in systematic reviews (Cooper, 1982; Mullen, 2003; Siess et al., 2014; Rockwood and Nathan-Roberts, 2018), which maps relevant publications that were referenced in these 73 publications. The ancestry approach only revealed seven additional (peer-reviewed) studies, bringing the total to 80.

Even though the selection criteria ensure that the selected studies are substantively relevant and academically high-quality, the selection process is limited in two ways. On the one hand, we only study published works of research. As Erzeel and Rashkova (2022) rightly mention, published work benefits from recognition from peers in the field, and ensures that quality-standards are met. However, this inevitably means that potentially valuable, but not yet published, studies are not included. This is not necessarily problematic, but we should be aware of a positive-results bias among authors, editors, and reviewers, especially in an emerging field like deliberative democracy. The published studies might overestimate trends that are considered established in a given field of research, and studies reporting negative or inconclusive results might have a harder time getting published. On the other hand, the use of Web of Science, EBSCO, and Scopus databases inevitably means an oversampling of publications in English. Relevant case studies of deliberative mini-publics and polarization in a particular country, published in a nationally or regionally relevant journal are therefore not included in the selection. Once again, we should therefore be aware that an oversampling of large, internationally known deliberative mini-publics, or mini-publics originating from English-speaking parts of the world is a by-product of our selection process.

2.2. Coding procedure

The abstracts and full texts of these 80 articles were systematically coded on the following variables. The first sets of codes were used to identify mere descriptives, including the year of publication, the type of publication (journal article, book chapter or proceedings), the country in which the study was conducted, and the primary discipline of the journal in which the articles were published.

Subsequently, we also coded the methodological variables, including the type of data-collection (quantitative, qualitative or mixed), the population from which the participants were drawn (students, specific demographic groups, or the general population), the total number of participants in the study and the recruitment method (targeted recruitment, random selection or self-selection).

Finally, we coded the central variables and the substantive results of the study. These included the following:

1. The conceptualization of deliberation: Even though democratic deliberation is often considered a clearly distinguishable form of communicative interaction based on reason, logic, argumentation, and respect (Landwehr and Holzinger, 2010), its implementation in empirical research is diverse. Mini-publics and group discussions vary widely in their specific designs, reflecting different underlying conceptualizations of deliberation, which is why we coded the key design features of the reported studies. These design features include the size of the deliberating group (the number of participants per deliberating group), the issue saliency (high, medium, low saliency), the mode of interaction (face-to-face or online), the presence of facilitators, and whether substantive information on the topic was given to the participants.

2. The conceptualization of polarization: Polarization is an essentially contested concept in the sense that there is no substantive agreement in the theory on the actual conceptualization of polarization (Lelkes, 2016). In general, it can be said to refer to a form of increasing distance between actors (Bosilkov, 2021). Within that, two main conceptualizations figure centrally in the literature, namely idea-based and affective polarization (Mason, 2013; Bernaerts et al., 2023). In the former, actors conflict over idea-based differences such as contrasting ideologies, political standpoints, and/or issue preferences, and become more distant in their idea-based positions as a result (see e.g., DiMaggio et al., 1996; Abramowitz and Saunders, 1998; Fiorina and Abrams, 2008). In the latter, actors are not necessarily in disagreement with each other, but diverge over their mutual identities, against which they feel negatively (see e.g., Iyengar et al., 2012; Mason, 2015; Reiljan, 2020). Affective forms of polarization thus include strong emotions and are based on affective, rather than intellectual distance.

3. The substantive results of the study: these variables included whether the study reports an actual effect (coded “yes,” “no” or “inconclusive”), the effect size in case an effect was reported (the standardized coefficient in case of quantitative studies, the authors' reported effect strength in case of qualitative studies), and the direction of the effect (“negative” if deliberation increased polarization, and “positive” if deliberation decreased polarization).

4. The causal mechanism: regarding the causal mechanism, we coded whether the authors mentioned any explanation for their findings, and in case they did, which causal mechanism was mentioned (e.g., intergroup contact theory, persuasive argument theory, common ingroup identity model).

The initial coding was conducted by author K.B. Author D.C. recoded all articles for the period 2016–2021 to validate the findings. Intercoder reliability tests were conducted on each of the variables. The rate of coder agreement (RCA) ranged between 86.8% and 100% over all codings. The lowest RCA was reported for the identification of the causal mechanism (intercoder agreement in 33 out of the 38 studies).

2.3. Data: sample descriptives

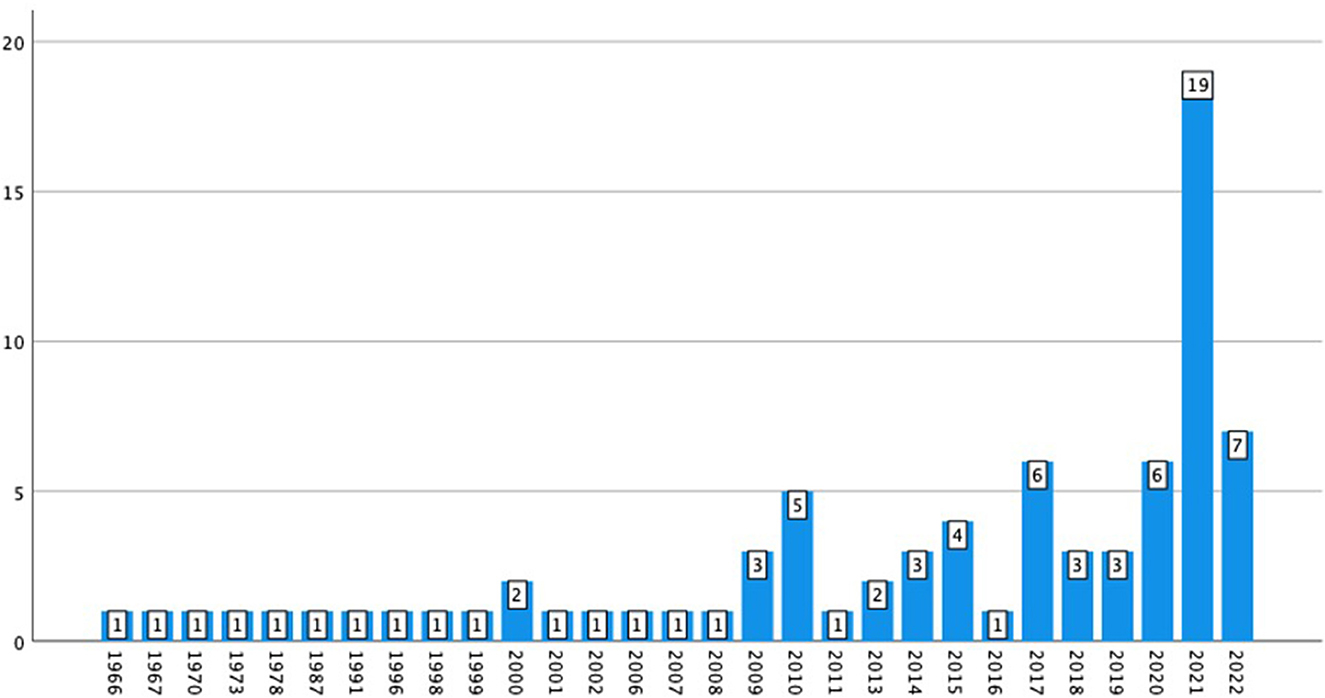

This section briefly discusses the basic descriptives of the sample of articles that were included in the dataset. First, we map the evolution of the publication of studies over time. Figure 2 shows a strong upward trend in the number of articles on the issue. It is clear that the relationship between deliberation and polarization has gained increasing attention over time. The bulk of studies on the issue were published after 2010 (60 out of 80 studies, or 75%), and this coincides with the empirical turn in deliberative democracy (Dryzek, 2010). However, what is especially striking is that no less than 26 studies (or 32.5% of the total) were published in the last two years.

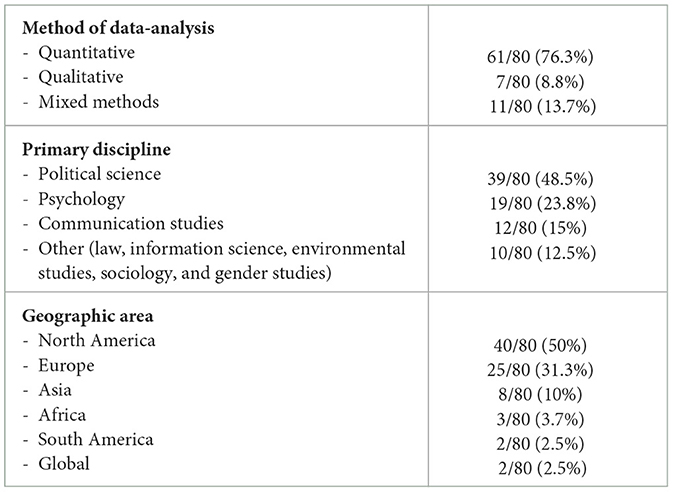

Of all studies included in the sample, the majority have been pursued quantitatively (61 out of 80 or 76.3% vs. 7 out of 80 or 23.7% qualitatively), and as can be seen in Table 1, almost half of them are published in political science (48.5%) and one quarter in social psychology (23.8%) journals. The table also shows the geographical spread, with most studies conducted in North America (50%) or Europe (31.3%).

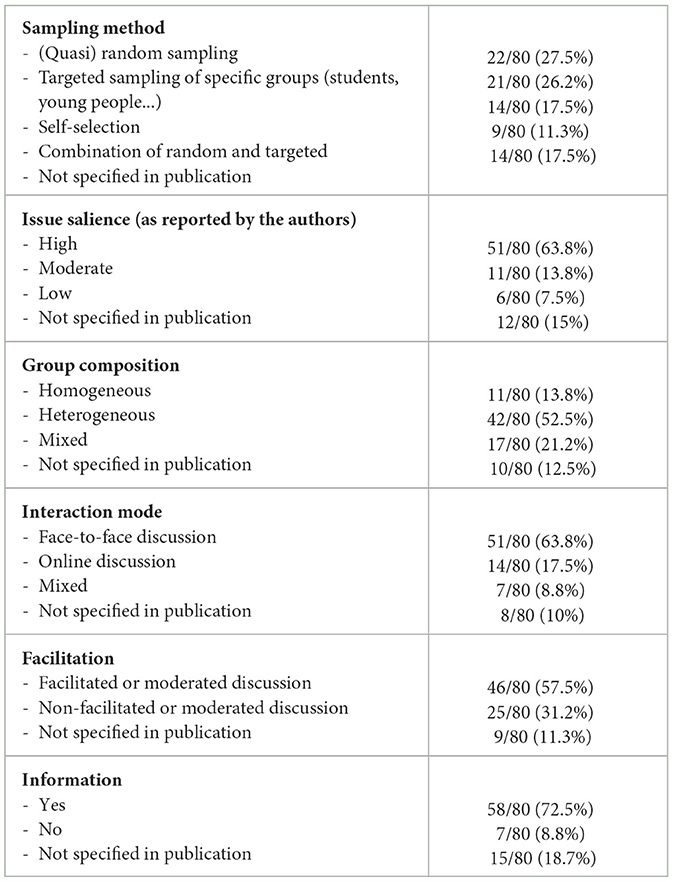

Lastly, as the studies varied to a great extent in terms of methodologies, an overview is also presented of the various kinds of methodological design features of the studies reported (Table 2). With regards to the population involved in the studies, 27.5% of the studies (22/80) relied on a (quasi-)random population sample. 26.2% used targeted recruitment, including citizens from a specific location or citizens having extreme attitudes, but also students. The salience of the topic of discussion, as reported by the authors themselves, was high in most studies (63.8%) and most of the salient studies dealt with immigration or climate change. About 52.5% of the discussion groups were heterogeneously composed, meaning that they consisted of participants that were deliberately diversely selected in terms of gender, ethnicity, religion, or opinion. 13.8% were homogeneously composed (consisting of members which explicitly shared a predetermined set of characteristics), and in 21.2% of the articles the researchers organized a combination of homogeneous and heterogeneous groups, mostly to assess the effect of group heterogeneity (see e.g., Caluwaerts and Reuchamps, 2014). In terms of interaction mode, the group discussions took place in a face-to-face format in 51 studies (63.8%), although computer-mediated (online) discussions were no exception (17.5%). Finally, facilitators were present in 57.5% of the studies, and in about 72.5% of the publications, the researchers provided substantive information about the discussion topic.

3. Conceptual diversity

As mentioned above, both deliberation and polarization are complex and multidimensional concepts. To properly understand the influence of deliberation on polarization, this paper takes a closer look at how both are conceptualized in the sample.

The first finding is the large amount of conceptual ambiguity or diversity. Even though we included the articles in the sample based on a broad repertoire of communicative interactions, it is striking that in those published articles claiming to test the effects of deliberation, the term “deliberation” seems to be used as a catch-all label encompassing a great many types of communicative interactions that are conceptually very distinct, and which vary along three axes. First, there is variation in the type of communication that is considered deliberation. This relates closely to type I (i.e., the strictly argument-based, rational, inclusive, respectful and consensus-oriented Habermasian conception of deliberation) and type II deliberation (i.e., a more open type of deliberation which allows for a multitude of communicative encounters including humor, rhetoric, and storytelling without the requirement to converge on a single position), which has figured centrally in the literature (Bächtiger et al., 2010; Bächtiger and Parkinson, 2019). Whereas some studies have very stringent definitions of which type of communication can be considered deliberative, others have very loose standards. About 30% of the studies (24 out of 80) mention that deliberation is conceptually distinct from mere communication in that it must meet some standards of respect, inclusion, and rationality. Another 55% of the publications (44 out of 80) include different types of organized group discussions, political talk among friends, family and colleagues, or jury deliberations. A final, more limited set of studies did not even organize deliberation but assessed the polarization-mitigating effects of for instance seeing a deliberative mini-public in action (i.e., seeing others deliberate) (Muradova et al., 2023) or being exposed to YouTube videos (Hwang et al., 2014). The latter types do not necessarily qualify as deliberation, in the sense of participants being able to interact with each other, but their findings were framed as such. We therefore still included them in the final dataset.

Secondly, there is variation in the type of interaction (see also Table 2). The majority of the studies (63.8%) rely on face-to-face interaction whereas 26.3% consisted of mediated types of interaction or a combination of both. The remaining studies did not explicitly specify how the participants interacted. Mediated interactions encompass both synchronous computer-mediated communication (i.e., live online deliberation), and asynchronous types of communication (e.g., people reacting to Tweets or newspaper articles).

Finally, the studies differ greatly in terms of the duration of the interaction. 44 out of 80 publications (about 55%) report the results of a deliberation that lasted 1 day or less, with group discussions ranging between 40 min and 8 h. Fifteen of them (or 18.8%) even lasted < 1 h. Another 17 studies (or 21.3%) lasted more than 3 days.

Even though this discussion on the different implementations of “deliberation” in the included studies seems conceptual and methodological, they greatly impact the overall effects we find as they reflect various conceptualizations of deliberation, as discussed above. After all, previous studies have highlighted that deliberation can only unleash its full potential when properly and carefully designed, i.e., when a diverse subsample of participants have had the opportunity to thoroughly and publicly argue their position and to listen to each other (Caluwaerts and Reuchamps, 2018). Any interpretation of the substantive findings on deliberation and polarization should therefore be closely linked to the conceptual discussion on how deliberation was implemented.

The same pattern of conceptual ambiguity can be observed regarding the definition of polarization along two axes. First, there was significant diversity in terms of the type of polarization. Polarization typically consists of two types: idea-based and affective polarization, essentially differentiating between polarization of substantive ideas or preferences on specific political issues (i.e., polarization of ideas), and polarization of people themselves based on their feelings, emotions and identities (i.e., affective polarization) (McCoy et al., 2018; Tappin and McKay, 2019; Reiljan, 2020; Boxell et al., 2022). Both types of polarization were represented in our systematic review, but the focus was strongly skewed in favor of idea-based polarization, which occurred in 53 articles (66.3%), while only 24 incorporated elements of affective polarization (30%). Most studies thus seemed to aim at de-politicizing and defusing specific political issues, rather than at bridging emotionally intensive conflicts of identity.

Secondly, there was significant ambiguity in the measurement of polarization. Among political scientists, sociologists, and social psychologists alike, there is disagreement on how to measure polarization exactly. Some, in the tradition of the risky shift phenomenon (Forsyth, 2010), claim that polarization is the process through which individuals in groups become more homogeneous and extreme in their previously held opinions and identities (see e.g., Lindell et al., 2017; PytlikZillig et al., 2018; Esterling et al., 2021). In other words, people in groups tend to cluster together toward one extreme position. Others argue, however, that extremization is not the same as polarization. Polarization means that individuals in groups tend to move toward opposing poles on the spectrum, and that distance from the mean opinion tends to widen (see e.g., DiMaggio et al., 1996; Hwang et al., 2014; Strandberg and Berg, 2020; McAvoy and McAvoy, 2021). A final way of measuring polarization is through the perception of polarization. Instead of measuring people's issue-based attitudes or their affective orientations, perception measures rely on people's subjective feelings about the level of polarization in the group and the perceived gap between opinions, which is usually overestimated (Ruggeri, 2021). Hitherto we found only one study which measures perceived polarization (albeit indirectly) in combination with deliberation and other measures (Caluwaerts and Reuchamps, 2014).

The same ambiguity can be witnessed in studies on deliberation and polarization. Within idea-based polarization (53 articles), two main forms are to be disentangled: unipolar convergence and bipolar divergence. The former, i.e., the process of attitudes converging toward one specific extreme (usually the one consistent with the groups pre-deliberation opinions), is observed in 27 articles (50.9%). The latter, which observes the creation of two (or more) poles within the group, figures centrally in 19 studies (32.1%).

Once again, this discussion might seem conceptual, but the implications are important. The manner in which one measures polarization, as one group becoming on average more extreme or two (or more) groups growing increasingly apart, is crucial in understanding the actual potential of deliberation as a depolarization strategy.

4. Directional effects

The descriptive results in the previous section show that the studies incorporated in this paper hold widely varying operationalizations of deliberation or polarization. In this section, we will discuss whether the studies show a trend in how deliberation affects polarization.

Despite their conceptual ambiguity, a clear pattern is discernible: the systematic review shows that 67 out of 80 studies (or 83.8%) did indeed find an effect of deliberation on polarization. Even though we should consider publication biases with authors, reviewers and editors being less likely to submit or accept null, negative or inconclusive findings, there is evidence that deliberation and polarization might be linked in a systematic and substantively significant manner.

Given that the measurement of deliberation and especially polarization varied widely across the studies, and given that not all studies reported comparable, standardized, quantitative effect measures, it is hard to assess its actual strength. We thus relied on the statistical effect size for quantitative studies, and on the strength of the effects reported by the researchers in qualitative studies. In 31.3% of the studies (25 out of 80), the authors reported that the relationship between deliberation and polarization was moderate at best, whereas in 15% of the studies (13 out of 80), the effect was strong. In 20% of the cases (16 out of 80), no conclusive results were reported because the effect of deliberation on polarization depended on a third variable. It is important to note that 71 out of 80 studies reporting an effect (88.8%), report the effect that was measured immediately after the deliberation. Very few studies thus actually assessed the long-term effects of deliberation on polarization.

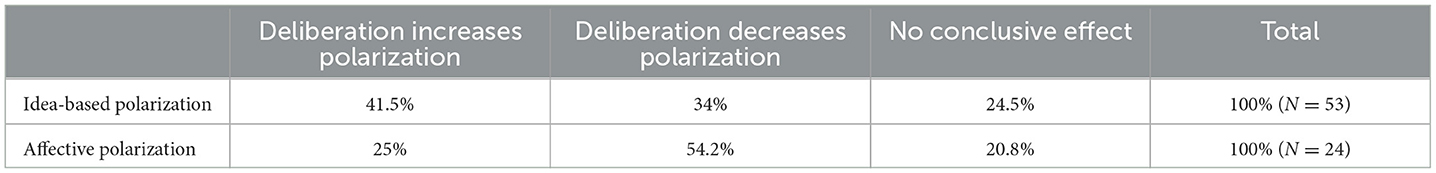

What is more interesting in light of our research question, however, is the direction of the reported effects. Of the articles reporting an effect, 29 observed a negative effect (43.3%), i.e., that deliberation increased polarization, and 31 a positive effect (46.3%), i.e., that deliberation reduced polarization. Moreover, as Table 3 shows, the direction of the effect also seems to depend on the type of polarization under investigation. After all, about 41.5% of all articles on idea-based polarization show that deliberation increases polarization, whereas deliberation is reported to decrease affective polarization in 54.2% of the cases. The effect of deliberation is thus contingent on the type of polarization, and deliberation seems to be more effective at decreasing affective types of polarization than on idea-based polarization. The suggestion that having groups of citizens discuss political issues suffices to decrease the levels of polarization within the group therefore needs qualification.

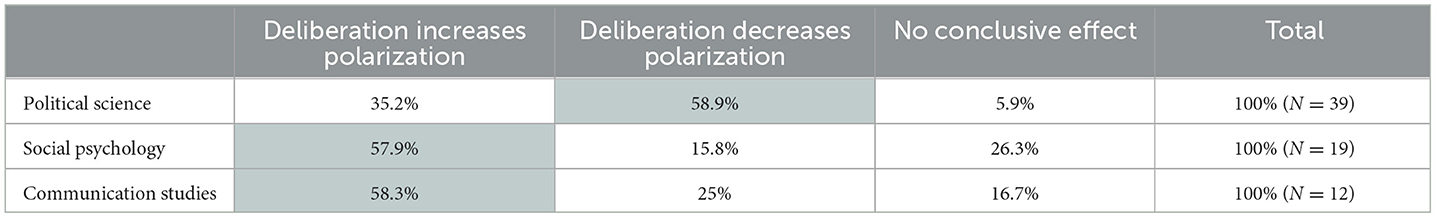

What the results furthermore tell us, is that the direction of the effect varies according to discipline (see Table 4). 59% of the articles published in political science journals report that deliberation can reduce polarization, whereas this effect is only reported in 17% of the social psychology studies. Social psychologists (paralleling the findings from the remaining disciplines) report much more often (in 61% of the cases) that group discussion actually increases polarization.

The strong association between the discipline and the results requires further investigation, but two explanations are possible. On the one hand, there might arguably be a positive-results bias. Political science approaches the issue mainly from the angle of deliberative democracy, and the wide-spread assumption among political scientists is that deliberation is capable of overcoming even the deepest and most contentious forms of disagreement. It is therefore expected that deliberation reduces polarization. In contrast, most psychological studies approach the theme from the polarization angle, and are interested in the risky shift phenomenon, predicting that deliberating groups would go to extremes. As such, studies reporting findings in line with the discipline's assumptions might get published more frequently, which might account for at least part of our findings.

On the other hand, the widely diverging findings in both disciplines might be due to the specific setup of the—mostly—experimental studies. Some design features which figure centrally in deliberative experiments in political science (among others independent facilitation, issue salience, information briefings, group size, duration, decision-making rules…) and are crucial from a deliberative democracy framework. However, they are not as prominent in social psychology where group deliberation usually involves brief interactions in small groups aimed at solving specific puzzles, or in communication studies where deliberation is often considered to be a specific type of political talk (see e.g., Burkhalter et al., 2002).

If the latter explanation holds true, there might be no publication bias, but the findings might reflect methodological design choices inherent to different conceptualizations of deliberation, as explained at greater length below.

5. The importance of deliberative design

Taken together, the findings in the previous section are generally incomplete. Based on the aggregate data presented, no definitive conditions can be identified under which deliberation increases or decreases polarization. To further examine this, we have also coded several of the methodological design features of the studies in our sample (Table 5). These might shed some light on the conditions under which deliberation has (de)polarizing effects and reflect various conceptualizations of deliberation as discussed above.

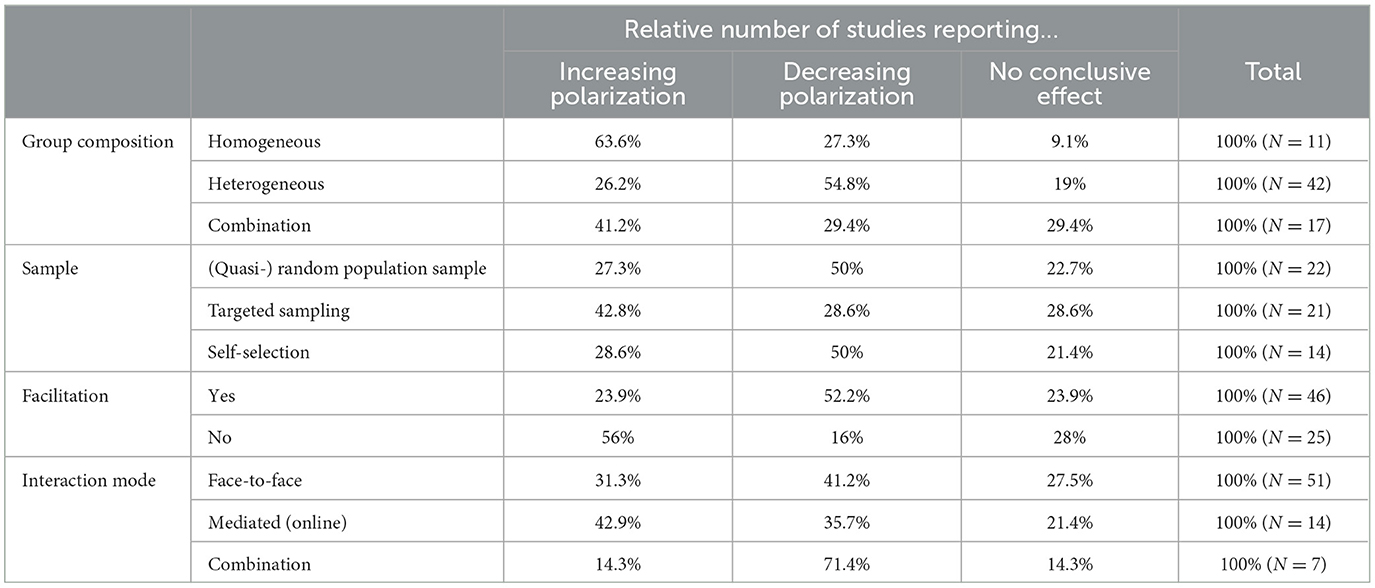

First, we looked at group composition, and the difference between groups that were deliberately homogeneously (e.g., based on the subjects' gender, opinions, ethnicity, or party affiliation) or heterogeneously composed. In line with Dryzek et al. (2019) argument, data suggest that deliberation among like-minded individuals is more likely to polarize groups (63.6%) than to moderate groups (27.3%) even though the number of studies with exclusively homogeneous groups is low (n = 11). Informational or affective inbreeding is thus reported to push groups to extremes more often than internally diverse groups. After all, heterogeneous groups observe more depolarization effects (54.8%) than polarization effects (26.2%). Based on the analyzed publications, deliberation can thus have depolarization effects, as long as there is sufficient disagreement in the deliberating group.

Secondly, we coded the sampling technique, and we distinguish between those studies which use (quasi-) random population samples (possibly quota corrected), targeted samples (focusing on specific groups of students, or people in certain geographic locations), and pure self-selection (where people volunteered to participate without stringent inclusion criteria). The result paint an interesting picture. Half of the studies using randomized population samples find that deliberation reduces polarization (50%), whereas only 27.3% find the opposite. The same trend is applicable to self-selected samples where 50% finds a decrease in polarization, and one quarter finds an increase. In contrast, 42.8% of the studies using targeted samples find that deliberation pushes groups to extremes, whereas about one quarter of those studies find that it reduces polarization (28.6%).

These findings can be explained in two ways. On the one hand, it might be that (quasi-) random samples encompass a more diverse subset of the population. Having such a diverse subset deliberate, might have the same effect as a deliberately heterogeneously composed group. Targeted samples might be more homogeneous and might therefore lead more often to an increase in polarization. In other words, the sampling technique might be a proxy for group heterogeneity. On the other hand, the findings could be an artifact of the discipline in which the studies were conducted: in line with what we reported before, political science studies (most often using some kind of random population sample in an effort to generate external validity) primarily find that deliberation reduced polarization, whereas studies in psychology (more often using targeted samples to maximize experimental control) find that the process increases polarization.

The third variable we coded was the presence or absence of a facilitator in the group discussion. Facilitation is generally considered a best practice in deliberative mini-publics (Spada and Vreeland, 2013), and this design characteristic seems to have a very substantive impact on the results. Of all the facilitated studies in our dataset, no less than 52.2% shows a downward trend and only 23.9% show increasing levels of polarization. In contrast, 56% of all studies with non-facilitated groups show increasing levels of polarization (versus 16% showing depolarization). In other words: groups which are guided by an independent facilitator tend to depolarize more often than to polarize; groups which are not facilitated tend to polarize much more often than to depolarize.

This is an interesting finding that could point in two directions. On the one hand, it could be that the presence of a facilitator ensures (1) that a space is created in which all arguments pro and con can be safely aired, and (2) that the norms of deliberation are enforced. The facilitator thus ensures experimental realism and conversational civility, thereby defusing potential tensions within the group and allowing the careful weighing of arguments. On the other hand, a less positive interpretation is that these findings might point to some experimenter bias. The mere presence of the researchers or their associate facilitators might convey the experimenters' expectations, and arguably be sufficient to cause groups to depolarize more strongly. Based on the systematic review, we cannot adjudicate which of these explanations holds true, but it does allow us to conclude that facilitation is a favorable condition for depolarization through deliberation.

The final variable of interest is the type of interaction, i.e., whether the participants in the deliberating groups met face-to-face, or whether their interaction was mediated (online). Even though we should be careful when interpreting the results, they do show a pattern: studies in which the participants are not physically confronted with each other more often report polarization (42.9%) than depolarization (35.7%). Among the face-to-face studies, these numbers are the inverse (41.2% reports depolarization vs. 31.3% reports polarization). Non-physical contact thus seems to increase, rather than decrease, conflict and polarization, which lends support to the humanization theory and the intergroup contact theory. It is easier to dehumanize your discussion partners and to devalue their arguments when you are not confronted with them, and there is very little incentive to give in to their ideas or arguments. This is in line with the Social Identity model of Deindividuation Effects (Reicher et al., 1995; Postmes et al., 2001; Spears et al., 2002; SIDE model) in social psychology, which states that non-physical contact between group members can reduce the salience of group norms. As such, the differences between (members of different) groups become more pronounced.

6. Causal mechanisms

The previous sections of this paper argue that design features and the conceptualization of deliberation play a crucial role in explaining deliberation's effect. Confirming earlier studies that deliberative designs which hold true to deliberative democratic designs, i.e., heterogeneous groups discussing salient issues in facilitated face-to-face interactions, might indeed decrease polarization Dryzek et al. (2019), those results are very interesting. However, the question remains how these results can be explained, and what the theoretical mechanisms are that supposedly explain either increases or decreases in polarization? Surprisingly few articles give any indication of why deliberation might have an effect. Only 47 out of 67 studies (70.1%) reporting an effect make some theoretical claim about the causal mechanism. When subdividing these explanations by the direction of the effect, it is striking that 75.9% of the studies reporting a negative effect (an increase in polarization) provide such an explanation, while only 58.1% of the studies with a positive effect (a decrease) do so. Table 6 gives an overview of the theories invoked by the different articles to explain the findings.

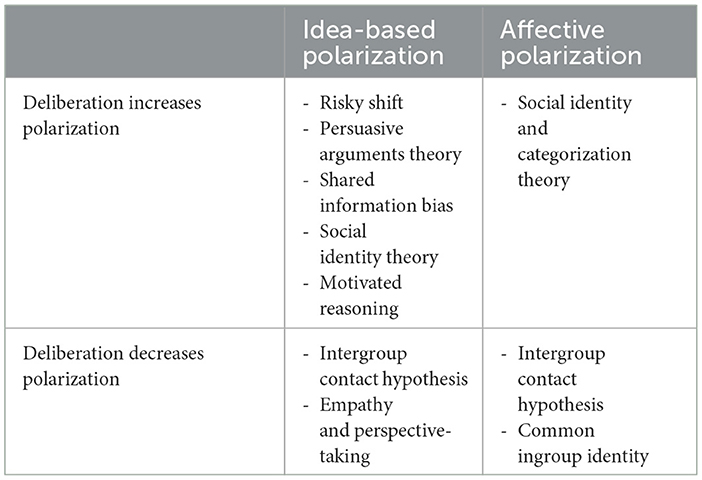

The finding that deliberation increases idea-based polarization, is most often explained by cognitive biases and errors in individual and group reasoning mostly. More specifically, and in line with the famous “risky shift,” the available theories in the sample argue that deliberating groups move to extremes due to persuasive arguments (i.e., more arguments will be brought to the table that support the groups pre-deliberation opinion), shared information biases (i.e. groups will only focus on that information that all members share), or social identity pressures (i.e., group members' tendency to be considered a prototypical group member by adopting a more extreme position than the group would adopt on average) (see e.g., Brauer et al., 2001; Sia et al., 2002; Hamlett and Cobb, 2006). Similarly, the theory of motivated reasoning, with participants not easily excepting new information when this does not support our initial idea, came across in one of the papers (Himmelroos and Christensen, 2020). The social identity theory is also mentioned in studies on affective polarization (Hwang et al., 2014): once group members figure out the attitudinal, emotional or identity orientations of the group, they tend to move more strongly in the group's pre-deliberation orientation to present themselves as the ideal, morally superior group member. Conversely, they stigmatize the less ideal members of their own group and devalue the outgroup. This further enhances pressures to conform to the group's—extreme—standpoint. In other words, it seems that the absence of deliberative norms that aim at fostering a rational debate between individuals, triggers cognitive biases that might explain the increase of polarization in those cases.

The explanation of the findings that deliberation decreases both forms of polarization, rests on a small number of theories. Most often, the articles point to the process of deliberation itself to explain the effect, without making very explicit which aspect of deliberation actually decreases polarization (see e.g., Wahl, 2021). At the most fundamental level, most studies argue that after the thorough and extensive process of deliberation and weighing information, the best arguments will prevail, and that these best arguments are generally not the most extreme ones. This argument is reminiscent of the dual process models of human rationality, which claim that deliberative reflection activates the analytic system, and decreases the chances of extreme decisions (Bago et al., 2020). Additionally, some authors claim that the physical presence of the other takes people out of their comfort zones, which in turn allows them to re-evaluate their own opinions (Lindell et al., 2017). Another formulation of this argument is that deliberation fosters depolarization through generating empathy. A deliberative space is one which is conducive to understanding others' opinions, arguments, and identities. Through deliberation, we empathize with others, acknowledge their humanity and moral concerns, and take their perspectives. This leads to understanding and moderation (Grönlund et al., 2017; Ugarriza and Trujillo-Orrego, 2017). This finding is particularly interesting because it contrasts with other research claiming that empathy can also increase polarization (Simas et al., 2020).

Even though the argument is most often invoked that the deliberative process is in some way exceptionally well suited to moderation and mutual understanding, two additional theoretically founded mechanisms are mentioned. Allport's intergroup contact hypothesis is mentioned, which claims that individuals will reduce conflict (and polarization) if they are put in a situation of equal status, physical contact, supportive group norms and overarching goals (see e.g., Caluwaerts and Reuchamps, 2014). Deliberation, in which everyone ideally has equal speaking time and influence, in which there are explicit group norms enforced by a facilitator, and in which the goal is to come to a collective decision, therefore meets the conditions for conflict-reduction set out by the contact hypothesis.

A final explanation for the conflict reducing potential of deliberation is inspired by the psychological common ingroup identity model. This explanation claims that polarization within the group will diminish as participants tend to develop a common identity as group members. Through deliberation, group members will come to identify with the deliberating group and overcome their differences, thereby reducing polarization within the group (Myers, 2021). Nevertheless, those theoretical mechanisms are to be studied in more detail, if we want to understand why exactly deliberative designs might help fight polarization in our democracies today.

7. Discussion

We are entering an age of anger, resentment, and disengagement, with rising levels of conflict and polarization. In response to those trends, deliberative democrats have argued that their talk-centric, procedural model of democracy might be the antidote to political and societal polarization. Democratic deliberation, as a process of weighing arguments and information among political equals, could counter centrifugal tendencies, and could incite accommodation and moderation between conflicting groups.

This assumption seems philosophically and democratically appealing, and many studies have been published on the subject, especially in recent years, both in the political science field and beyond. However, a clear overview of the promises and pitfalls of deliberation in the fight against polarization is missing. There are seemingly contradictory findings in the literature that deliberation (broadly understood) sometimes led to depolarization, and sometimes led to polarization of groups. We therefore conducted a systematic review of the literature, including studies ranging from short experimental group discussions to multi-day citizen assemblies, based on which we can draw several conclusions. First, we argue that the effects of communicative encounters on polarization are conditional on how those types of communication were conceptualized across disciplines. More precisely, we find depolarizing effects when group discussions adhere to a deliberative democracy framework, and polarizing effects when they do not. Fields outside of political science might use a conceptualization that does not fully reflect the original idea of deliberative democracy, and more often report polarization effects.

A second conclusion is that deliberation's effect on polarization can be positive and negative depending on the conceptualization of polarization. 43.3% of the studies found that deliberation increased polarization, whereas 46.3% found a decrease, and the other studies did not reach any definitive conclusion. Much depended on the exact type of polarization. Communicative encounters between group members more strongly increased idea-based polarization, but it decreased affective polarization. Additionally, the direction of the effects correlated with the discipline in which the effect was studied. Political science publications more often report a decrease in polarization; social psychology usually reports an increase in polarization. As mentioned before, this could be due to the methodological specifics of the studies, or to the different conceptualizations of deliberation in those studies.

A third finding is that deliberation's effect on polarization is contingent on many factors. We found that deliberation can decrease polarization albeit under the right deliberative conditions. Those conditions seem to be the group composition (with heterogeneous groups being more likely to depolarize than homogeneous groups), facilitation (with facilitated groups being much more likely to depolarize than non-facilitated groups), and interaction mode (with face-to-face deliberation being more likely to depolarize mediated (online) deliberation). This echoes an oft-heard finding in deliberative research that deliberative design matters a great deal.

A final finding is that—even if the majority of the articles report an effect in whichever direction—their authors often remain silent about the causal mechanisms underlying their findings. According to us, this constitutes one of the main shortcomings in extant research on the subject. Very few studies were able to corroborate any theoretical explanation for the findings, or adjudicate between different causal mechanisms, and very few mediating effects are listed.

Even though we have been able to draw some overarching conclusions on the contingent effect of deliberation on polarization, future research would ideally tackle two related issues. On the one hand, a first problem relates to the concept of deliberation. One of the main problems we faced during the coding and analysis, was the rich conceptual diversity in the studies on this subject. We justified earlier in this paper why we included a broad range of group interactions, but to some extent, the question whether deliberation impacts polarization depends on the question of how deliberation is conceptualized. After all, can we reasonably expect to find similar results from a 40-min classroom as from a multi-weekend citizen assembly? It would therefore be good to further deconstruct the concept of deliberation, and to determine how different conceptualizations produce different substantive results.

On the other hand, our finding that few studies explicitly mention a causal mechanism necessitates further inquiry. We have found that deliberation can have depolarizing effects under certain conditions, reflecting different conceptualizations of polarization, but we cannot yet draw definitive conclusions on why these conditions foster depolarization. What the scholarship needs is a much clearer answer to the question of what works for whom, under what conditions, and why. Deeper insight is therefore needed to pinpoint the exact psychological, institutional, or discursive mechanisms that underly the reported effects, and this inevitably means a stronger integration of different disciplines and methodologies on the fundamental psychological processes that are at work during group interactions. Meeting these challenges could offer us much-needed insights into how we can protect democracy against the forces of polarization in the future.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

DC, KB, RK, and BS contributed to initial conception and design of the study. DC, KB, and LS conducted the systematic literature search and study selection. DC and KB ran the statistical analyses. DC wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. RK, LS, and BS rewrote and reviewed sections of the manuscript. All authors substantially contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the NORFACE Joint Research Programme on Democratic Governance in a Turbulent Age and co-funded by [AEI, ANR, ESRC, FWO, NCN, NWO], and the European Commission through Horizon 2020 under grant agreement No. 822166, Research Foundation - Flanders (FWO Vlaanderen) [grant number G0G7620N], and EUTOPIA Institutional Partnership under [grant number EUTOPIA-PhD-2021-0000000058].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abramowitz, A. I., and Saunders, K. L. (1998). Ideological Realignment in the U.S. electorate. J. Polit. 60, 634–652. doi: 10.2307/2647642

Bächtiger, A., Niemeyer, S., Neblo, M., Steenbergen, M. R., and Steiner, J. (2010). Disentangling diversity in deliberative democracy: competing theories, their blind spots and complementarities. J. Pol. Philosophy 18, 32–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9760.2009.00342.x

Bächtiger, A., and Parkinson, J. (2019). Mapping and Measuring Deliberation. Micro and Macro Knowledge of Deliberative Quality, Dynamics and Contexts. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780199672196.001.0001

Bago, B., Bonnefon, J-. F., and Neys, D. e. W. (2020). Intuition rather than deliberation determines selfish and prosocial choices. J. Exp. Psychol. 3, 968. doi: 10.1037/xge0000968

Bernaerts, K., Blanckaert, B., and Caluwaerts, D. (2023). Institutional design and polarization. Do consensus democracies fare better in fighting polarization than majoritarian democracies? Democratization. 4, 300. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2022.2117300

Bosilkov, I. (2021). Too incivil to polarize: the effects of exposure to mediatized interparty violence on affective polarization. J. Elect. 4, 8679. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2021.1928679

Boxell, L., Gentzkow, M., and Shapiro, J. M. (2022). Cross-country trends in affective polarization. The Review of Economics and Statistics. doi: 10.1162/rest_a_01160

Brauer, M., Judd, C. M., and Jacquelin, V. (2001). The communication of social stereotypes: the effects of group discussion and information distribution on stereotypic appraisals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 81, 463–475. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.3.463

Broockman, D. E., Kalla, J. L., and Westwood, S. J. (2022). Does affective polarization undermine democratic norms or accountability? Am. J. Polit. Sci. 4, 12179. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12719

Burkhalter, S., Gastil, J., and Kelshaw, T. (2002). A conceptual definition and theoretical model of public deliberation in small face-to-face groups. Commun. Theory 12, 398–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00276.x

Caluwaerts, D., and Reuchamps, M. (2014). Does inter-group deliberation foster inter-group appreciation? Evidence from two experiments in Belgium. Politics 34, 101–115. doi: 10.1111/1467-9256.12043

Caluwaerts, D., and Reuchamps, M. (2018). The Legitimacy of Citizen-led Deliberative Democracy. The G1000 in Belgium. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315270890

Carothers, T., and O'Donohue, A. (2019). Democracies Divided: The Global Challenge of Political Polarization. Washington: The Brookings Institution.

Conover, P. J., and Miller, P. R. (2018). “Taking everyday political talk seriously,” in The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, eds Bächtiger, A., Dryzek, J. S., Mansbridge, J. and Warren, M. E. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 378-391. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747369.013.12

Conover, P. J., and Searing, D. D. (2005). Studying ‘everyday political talk'in the deliberative system. Acta Politica 40, 269–283. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500113

Cooper, H. M. (1982). Scientific guidelines for conducting integrative research reviews. Rev. Educ. Res. 52, 291–302. doi: 10.3102/00346543052002291

DiMaggio, P., Evans, J., and Bryson, B. (1996). Have American's social attitudes become more polarized? Am. J. Sociol. 102, 690–755. doi: 10.1086/230995

Dryzek, J. (2010). Foundations and Frontiers of Deliberative Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199562947.001.0001

Dryzek, J.Bächtiger, A., et al. (2019). The crisis of democracy and the science of deliberation. Science 363, 1144–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw2694

Erzeel, S., and Rashkova, E. (2022). The substantive representation of social groups: towards a new comparative research agenda. Eur. J. Polit. Gender. 3, 8686. doi: 10.1332/251510821X16635712428686

Esterling, K. M., Fung, A., and Lee, T. (2021). When deliberation produces persuasion rather than polarization: measuring and modeling small group dynamics in a field experiment. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 666–684. doi: 10.1017/S0007123419000243

Finkel, E. J., Bail, C. A., Cikara, M., Ditto, P. H., Iyengar, S., Klar, S., et al. (2020). Political sectarianism in America. Science 370, 533–536. doi: 10.1126/science.abe1715

Fiorina, M. P., and Abrams, S. J. (2008). Political polarization in the American public. Ann. Rev. of Polit. Sci. 11, 563–588. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.053106.153836

Fishkin, J., Siu, A., Diamond, L., and Bradburn, N. (2021). Is deliberation an antidote to extreme partisan polarization? Reflections on “America in one room”. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 3, 642. doi: 10.1017/S0003055421000642

Gastil, J., Bacci, C., and Dollinger, M. (2010). Is deliberation neutral? Patterns of attitude change during “the deliberative pollsTM.” J. Public Delibe. 6, 3. doi: 10.16997/jdd.107

Gastil, J., and Hale, D. (2018). “The jury system as a cornerstone of deliberative democracy,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Deliberative Constitutionalism, eds R. Levy, H. Kong, G. Orr, and J. King (New York: Cambridge University Press), 233-245. doi: 10.1017/9781108289474.018

Grönlund, K., Herne, K., and Setälä, M. (2015). Does enclave deliberation polarize opinions? Polit. Behav. 37, 995–1020. doi: 10.1007/s11109-015-9304-x

Grönlund, K., Herne, K., and Setälä, M. (2017). Empathy in a citizen deliberation experiment. Scan. Polit. Stud. 40, 457–480. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.12103

Hamlett, P. W., and Cobb, M. D. (2006). Potential solutions to public deliberation problems: structured deliberations and polarization cascades. Policy Stud. J. 34, 629–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2006.00195.x

Hartman, R., Blakey, W., Womick, J., Bail, C., Finkel, E. J., Han, H., et al. (2022). Interventions to reduce partisan animosity. Nat. Human Behav. 6, 1194–1205. doi: 10.1038/s41562-022-01442-3

Himmelroos, S., and Christensen, H. S. (2020). The potential of deliberative reasoning: patterns of attitude change and consistency in cross-cutting and like-minded deliberation. Acta Politica 55, 135–155. doi: 10.1057/s41269-018-0103-3

Huddy, L., and Yair, O. (2021). Reducing affective polarization: warm group relations or policy compromise? Polit. Psychol., 42, 291–309. doi: 10.1111/pops.12699

Hwang, H., Kim, Y., and Huh, C. U. (2014). Seeing is believing: effects of uncivil online debate on political polarization and expectations of deliberation. J. Broadcast. Elect. Media 58, 621–633. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2014.966365

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., and Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., and Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: a social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opin. Q. 76, 405–431. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfs038

Kim, J., and Kim, E. J. (2008). Theorizing dialogic deliberation: everyday political talk as communicative action and dialogue. Commun. Theory 18, 51–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00313.x

Kingzette, J., Druckman, J. N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M., and Ryan, J. B. (2021). How affective polarization undermines support for democratic norms. Public Opin. Q. 85, 663–677. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfab029

Lamm, H., and Myers, D. G. (1978). Group-induced polarization of attitudes and behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 11, 145–195. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60007-6

Landwehr, C., and Holzinger, K. (2010). Institutional determinants of deliberative interaction. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2, 373–400. doi: 10.1017/S1755773910000226

Lelkes, Y. (2016). The polls-review: mass polarization: manifestations and measurements. Public Opin. Q. 80, 392–410. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfw005

Levendusky, M. S. (2018). Americans, not partisans: can priming American national identity reduce affective polarization? J. Polit. 80, 59–70. doi: 10.1086/693987

Lindell, M., Bächtiger, A., Grönlund, K., Herne, K., Setälä, M., Wyss, D., et al. (2017). What drives the polarisation and moderation of opinions? Evidence from a Finnish citizen deliberation experiment on immigration. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 56, 23–45. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12162

Mason, L. (2013). The rise of uncivil agreement: issue vs. behavioral polarization in the American electorate. Am. Behav. Scient. 57, 140–159. doi: 10.1177/0002764212463363

Mason, L. (2015). “I disrespectfully agree”: the differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 59, 128–145. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12089

McAvoy, P., and McAvoy, G. E. (2021). Can debate and deliberation reduce partisan divisions? Evidence from a study of high school students. Peabody J. Edu. 3, 706. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2021.1942706

McCoy, J., Rahman, T., and Somer, M. (2018). Polarization and the global crisis of democracy: common patterns, dynamics, and pernicious consequences for democratic polities. Am. Behav. Scien. 62, 16–42. doi: 10.1177/0002764218759576

McCoy, J., and Somer, M. (2019). Toward a theory of pernicious polarization and how it harms democracies: comparative evidence and possible remedies. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 681, 234–271. doi: 10.1177/0002716218818782

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., and Group, P. R. I. S. M. A. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 151, 264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

Muradova, L., Culloty, E., and Suiter, J. (2023). Misperceptions and minipublics: does endorsement of expert information by a minipublic influence misperceptions in the wider public? Polit. Commun. 3. 735. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2023.2200735

Myers, C. D. (2021). The dynamics of social identity: evidence from deliberating groups. Polit. Psychol. 3, 12749. doi: 10.1111/pops.12749

Myers, D. G., and Lamm, H. (1976). The group polarization phenomenon. Psychol. Bull. 83, 602–627. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.83.4.602

Orhan, Y. E. (2022). The relationship between affective polarization and democratic backsliding: comparative evidence. Democratization 29, 714–735. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2021.2008912

Persily, N., and Tucker, J.A. (2020). Social Media and Democracy: The State of the Field, Prospects for Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108890960

Polletta, F., and Gardner, B. G. (2018). “The forms of deliberative communication,” in The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, eds Bächtiger, A., Dryzek, J. S., Mansbridge, J., and Warren, M. E. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 69-85. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747369.013.45

Postmes, T., Spears, R., Sakhel, K., and Groot, D. e. D. (2001). Social influence in computer-mediated communication: the effects of anonymity on group behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 27, 1242–1254. doi: 10.1177/01461672012710001

PytlikZillig, L.M., Hutchens, M.J., Muhlberger, P., and Gonzalez, F.J. Tomkins, A.J. (2018). Deliberative Public Engagement with Science. Chan: Springer Open. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-78160-0

Reicher, S., Spears, R., and Postmes, T. (1995). A social identity model of deindividuation phenomena. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 6, 161–198. doi: 10.1080/14792779443000049

Reiljan, A. (2020). ‘Fear and loathing across party lines' (also) in Europe: affective polarisation in European party systems. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 59, 376–396. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12351

Rockwood, J., and Nathan-Roberts, D. (2018). A systematic review of communication in distributed crews in high-risk environments. Proceed. Human Factors Ergono. Soc. Ann. Meet. 62, 102–106. doi: 10.1177/1541931218621023

Ruggeri, K. (2021). The general fault in our fault lines. Nat. Human Behav. 5, 1369–1380. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01092-x

Sia, C-. L., Tan, B. C. Y., and Wei, K-. K. (2002). Group polarization and computer-mediated communication: effects of communication cues, social presence, and anonymity. Inform. Sys. Res. 13, 70–90. doi: 10.1287/isre.13.1.70.92

Siess, J., Blechert, J., and Schmitz, J. (2014). Psychophysiological arousal and biased perception of bodily anxiety symptoms in socially anxious children and adolescents: a systematic review. Eur. Child dolesc. Psychiatry 23, 127–142. doi: 10.1007/s00787-013-0443-5

Simas, E. N., Clifford, S., and Kirkland, J. H. (2020). How empathic concern fuels political polarization. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev., 114, 258–269. doi: 10.1017/S0003055419000534

Simonsson, O., Narayanan, J., and Marks, J. (2022). Love thy (partisan) neighbor: brief befriending meditation reduces affective polarization. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 25, 1577–1593. doi: 10.1177/13684302211020108

Smith, G., and Setälä, M. (2018). “Minipublics and deliberative democracy,” in The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, eds Bächtiger, A., Dryzek, J. S., Mansbridge, J., and Warren, M. E. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 300–314. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747369.013.27

Spada, P., and Vreeland, J. (2013). Who moderates the moderators? The effect of non-neutral moderators in deliberative decision making. J. Public Delib. 9. doi: 10.16997/jdd.165

Spears, R., Postmes, T., Lea, M., and Wolbert, A. (2002). The power of influence and the influence of power in virtual groups: a SIDE look at CMC and the Internet. J. Soc. Issues 58, 91–108. doi: 10.1111/1540-4560.00250

Strandberg, K., and Berg, J. (2020). When reality strikes: Opinion changes among citizens and politicians during a deliberation on school closures. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 3, 5931. doi: 10.1177/0192512119859351

Strandberg, K., Himmelroos, S., and Grönlund, K. (2019). Do discussions in like-minded groups necessarily lead to more extreme opinions? Deliberative democracy and group polarisation. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 40, 41–57. doi: 10.1177/0192512117692136

Sunstein, C. R. (2000). Deliberative trouble? Why groups go to extremes. Yale Law J. 110, 71–119. doi: 10.2307/797587

Sunstein, C. R. (2002). The law of group polarization. J. Polit. Philos. 10, 175–195. doi: 10.1111/1467-9760.00148

Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Going to Extremes. How Like Minds Unite and Divide. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sunstein, C. R. (2017). #Republic. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400884711

Tappin, B. M., and McKay, R. T. (2019). Moral polarization and out-party hostility in the US political context. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 7, 213–245. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v7i1.1090

Ugarriza, J. E., and Trujillo-Orrego, N. (2017). The ironic effect of deliberation: what we can (and cannot) expect in deeply divided societies. Acta Politica 55, 221–241. doi: 10.1057/s41269-018-0113-1

Voelkel, J. G., Chu, J., Stagnaro, M. N., Mernyk, J. S., Redekopp, C., Pink, S. L., et al. (2023). Interventions reducing affective polarization do not necessarily improve anti-democratic attitudes. Nat. Human Behav. 7, 55–64. doi: 10.1038/s41562-022-01466-9

Wahl, R. (2021). Not monsters after all: how political deliberation can build moral communities amidst deep difference. J. Delib. Democ. 17, 160–168. doi: 10.16997/jdd.978

Warner, B. R., Horstman, H. K., and Kearney, C. C. (2020). Reducing political polarization through narrative writing. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 48, 459–477. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2020.1789195

Westwood, S. J., Iyengar, S., Walgrave, S., Leonisio, R., Miller, L., Strijbis, O., et al. (2018). The tie that divides: cross-national evidence of the primacy of partyism. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 57, 333–354. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12228

Keywords: deliberative democracy, polarization, affective polarization, democracy, systematic review

Citation: Caluwaerts D, Bernaerts K, Kesberg R, Smets L and Spruyt B (2023) Deliberation and polarization: a multi-disciplinary review. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1127372. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1127372

Received: 19 December 2022; Accepted: 15 June 2023;

Published: 29 June 2023.

Edited by:

Annika Lindholm, Université de Lausanne, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Staffan Himmelroos, University of Helsinki, FinlandJean-Benoit Pilet, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium

Jane Suiter, Dublin City University, Ireland

Copyright © 2023 Caluwaerts, Bernaerts, Kesberg, Smets and Spruyt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Didier Caluwaerts, ZGlkaWVyLmNhbHV3YWVydHNAdnViLmJl

Didier Caluwaerts

Didier Caluwaerts Kamil Bernaerts

Kamil Bernaerts Rebekka Kesberg

Rebekka Kesberg Lien Smets

Lien Smets Bram Spruyt

Bram Spruyt