94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 05 April 2023

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1123332

This article is part of the Research TopicLobbying in Comparative ContextsView all 5 articles

The postbellum rise of voluntary, federated associations set the stage for modern pressure politics in the American states, yet the connection between associations and lobbying in this era is grossly understudied. Relying on associations' own records and a new dataset of state lobbyists, we explore this relationship more deeply, documenting how federated associations gained membership, created political agendas, and lobbied state legislators for reform. To understand better the processes linking group strength with direct lobbying, we present descriptive case studies of the Grange (agriculture), the “Big Four” railroad brotherhoods (skilled labor), and the American Bankers' Association (finance). Our findings reveal how group strength, measured by association membership or local organizing, was not always related to the choice to lobby legislatures directly. These findings suggest pathways for future research comparing Progressive Era associations to one another, as well as showing how their actions parallel those of modern pressure groups. This analysis also paves the way for a more robust temporal understanding of lobbying in the American states.

Historians and political scientists have long noted that the United States is a “nation of joiners” (Schlesinger, 1944; see also Tocqueville, 1863[1838]). This aspect of the American nation developed over time but assumed great importance in the late 1800s and early 1900s. During those decades, federated associations spread across the nation and united citizens for political purposes. While their popularity waned with the advent of advocacy and non-profit groups in the 1960s, associations were foundational to American society and representative government (e.g., Putnam, 1995; Skocpol, 2003).

Yet, political scientists have given little attention to associations' political activities before the advocacy explosion of the 1960s. Tichenor and Harris (2005, p. 257–58) label this “the conceits of modern times”—that is, interest group scholars tend to dismiss the past and focus on the post-World War II era.1 Tichenor and Harris (2002–2003) counter these omissions by examining the rise of lobbying in Congress from 1833 to 1917, revealing that activity increased after the Civil War and became more prominent with the expansion of the national government's policy agenda during the Progressive Era. This early 20th century advocacy explosion was critical to the development of the American interest group state and the use of direct lobbying targeting state governments (Lane, 1964; Clemens, 1997).

To date, existing research has not linked the spread of state and local affiliates of national, often federated, associations with increased pressure on politicians across state governments. This is an important oversight. The mobilization of associations and their rise to prominence in the early 20th century corresponded to the first efforts at tracking lobbyists; whether and how this mobilization via large membership associations translated into direct lobbying merits study. Such an analysis will provide a better sense of how so-called modern lobbying developed in this era, and in turn shape how we broadly think about lobbying across American political history.

In this paper, therefore, we explore the relationship between the emergence of pressure politics in state legislatures and the postbellum rise of associations. To facilitate this analysis, we employ a comparative case study approach focused on three large associations that utilized direct lobbying in the states: the Grange (a membership group of farmers), the “Big Four” railroad brotherhoods (labor unions of skilled workers), and the American Bankers' Association (a trade group composed of leaders of member banks). We utilize a unique combination of state lobbyist registration and association data, supplemented with qualitative evidence from primary sources, to draw comparisons between how various types of associations used direct lobbying. By using three case studies of associations with some type of federated structure based on members joining local units, this descriptive approach will help us to illustrate when and how association-driven mobilization leads to direct lobbying.

Our results reveal that all of the groups we study pursued direct lobbying and state-level policy advocacy, but when and how they employed these strategies varied. The Grange was a prominent lobbying force in states where it had more members, suggesting that federated membership associations could utilize their sheer size to support direct lobbying. But, the connection between membership and lobbying is weaker for the railroad brotherhoods and absent for the American Bankers' Association. For these associations, the turn to lobbying came about through greater inter- and intra-association collaboration at the state and national levels. Cooperation across associations on joint legislative boards helped the railroad brotherhoods establish themselves as a potent lobbying force, while the ABA adopted a top-down approach, facilitating state lobbying efforts through the use of a full-time, professional lawyer and lobbyist who worked on behalf of the national organization. We conclude that membership type, association strength, and internal group strategy all affected the use and prevalence of state legislative lobbyists during the Progressive Era; these findings add to the literature by emphasizing that the relationship between interest group mobilization and direct lobbying varied significantly across association type. These findings also underscore that the activities of these groups—which mirror 21st. century interest group behaviors—have significant implications for modern scholars interested in questions about issue advocacy and social capital. In particular, studying specific groups and cases can illuminate patterns and strategies that might be underappreciated or go unobserved in large-N quantitative studies.

Federated voluntary associations have long been classified as “pressure groups”—organizations that take positions on political issues and advocate for policy change. Pre-1940s accounts of these groups' advocacy laid the groundwork for many influential modern studies of interest groups and lobbying. Odegard (1928), for example, examined how the Anti-Saloon League's prohibition advocacy transformed pressure politics. His work motivated Clemens (1997) to examine other groups' activities during this era. Herring (1929) evaluated the growth of organizations as lobbyists in Congress, inspiring later analyses by Schlozman and Tierney (1986) and Baumgartner and Leech (1998). And, Belle Zeller's (1937) groundbreaking work on association advocacy in New York showcased the importance of studying group activity at the subnational level, influencing state politics scholars to consider the density and diversity of interest communities (e.g., Gray and Lowery, 2002).

Modern scholarship on interest groups and lobbying, thus, owes a debt of gratitude to earlier research. Yet, there is little modern research on the initial development of relationships between groups and lobbyists, and how these connections shaped the interest group environment. One notable exception is the work of Tichenor and Harris (2002–2003). Informed by analyses tracing the development of labor, agricultural, and women's associations, they use congressional hearing records to examine the growth of lobbying from 1833 to 1917 and find evidence of substantial increases during the Progressive Era. In so doing, they make a significant contribution to understanding the origins of influence in American politics. Critically, Tichenor and Harris (2002–2003, p. 606) suggest that future studies of interest group systems should consider five key factors: “the aggregate number of organized interests; the variety of organized interests; the nationalization of organized interests; the professionalism of organized interests; and the structural opportunities and obstacles confronting organized interests.”

Empirical data that speak to these five factors are available for both groups and lobbying at the state level, but political scientists (including Tichenor and Harris) generally study them separately. With respect to associations, Gamm and Putnam (1999) collected counts of groups from city and organizational directories, and Skocpol (2003), her co-authors (Skocpol et al., 2000; Crowley and Skocpol, 2001), and other scholars (Chamberlain et al., 2017, 2019, 2020), have gathered information from associations' annual reports and other records. These studies address two of Tichenor and Harris' five factors, namely the formation and mobilization of organized interests. But, how these organized interests—given their number, diverse goals, centralization, professionalization, and ability to pressure government officials—turned mobilization into political pressure requires careful analysis of lobbying activity.

We seek to bridge this gap between mobilization and lobbying. Such an analysis both establishes a foundation for the systematic, quantitative study of pressure groups during the late 19th and early 20th centuries and begins to build connections between comparative state analyses in this era and modern research on issue advocacy and social capital. Mobilization in this era found its voice in membership associations, and these associations became politically engaged in direct lobbying. Therefore, it is imperative to focus on when and how this mobilization in associations related to leaders' efforts at reforming public policy through direct lobbying.

Our analyses focus squarely on the locations where federated associations were built and lobbying regulations were first enacted: the states. The rationale for a state-centered focus begins with the rise of antebellum voluntary associations, most of which were federated. These groups, like the American national government, recognized states and localities as organizing units. This mode of organization continued after the Civil War, particularly in the North, where citizens were invigorated by a victorious war effort (Crowley and Skocpol, 2001). Throughout the last quarter of the 1800s, federated voluntary membership associations formed rapidly and expanded. Professional and business (trade) associations did so too, looking to government—and especially state governments—for rules and regulations as modernization transformed the country (Wiebe, 1989[1962]). Yet, why turn to direct lobbying?

This is an important question; direct lobbying is just one pressure strategy available to associations. During the antebellum era, for example, abolition and temperance groups often relied on petitions to seek redress for grievances (Carpenter and Moore, 2014; Carpenter and Schneer, 2015; Carpenter et al., 2018). After the Civil War, moral reform groups continued to use petitions, labor unions grappled with strikes, and corporate and business leaders entered politics via campaign donations, gifts, and, at times, nefarious tactics to extract demands from elected officials. If these tactics had been sufficient, associations would not have borne the costs of direct lobbying, which included paying or otherwise authorizing individuals to communicate and build relationships with lawmakers. Direct lobbying also entailed reputational risks, since, at the time, it was seen as a tactic used most often by private interests, particularly businesses, that also engaged in corrupt acts.2

We argue that post-Civil War federated associations turned to direct lobbying, in part, in response to the structural opportunities and challenges Tichenor and Harris urged scholars to consider. Greater resources—population, mobility, and modernization (Chamberlain et al., 2017)—provided opportunities for organizational expansion and professionalization, which became increasingly important as the environment became densely populated with associations competing for members, resources, and government attention. As part of this transition, groups became less reliant on the work of individual members—who were often costly to manage and could choose to operate in opposition to group goals—in favor of direct lobbying that conveyed the organization's demands to legislators more efficiently.

One example of this strategic shift is the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). Founded in 1874, it originally used moral suasion to win supporters to the temperance cause. This was abandoned, however, by the association's second president, Frances Willard (who served from 1879 until her death in 1898). In her Home Protection Manual, Willard called for increased attention to policymakers; petitioning was significant, but the need for model legislation that could be passed by any state legislature was more important. This approach was refined by Mary Hunt, the so-called “Queen of the Lobby,” who coordinated a massive direct lobbying campaign in the 1880s to ensure schools taught scientific temperance education (a “science-based” curriculum explaining the dangers of alcohol). Her approach included directly contacting state legislators and going to state legislative sessions to ensure model bills were introduced, approved by committees, and enacted into law (Zimmerman, 1992).

The shortcomings of post-Civil War state legislatures—frequently ridiculed for being inadequate, incompetent, indecent, or some combination of the three—also presented groups with an opportunity to act as conduits of information. Legislators were paid little for their time and lacked office space and administrative support; they had few resources for learning about political issues (Squire, 2012, p. 231–248). Early legislative reforms in some states (such as Wisconsin) alleviated some of these limitations, but most state legislatures did not professionalize until the 1960s. In this institutional environment, associations and lobbyists could serve as intermediaries, subsidizing the legislative process and educating citizens, and simultaneously achieving their own organizational goals (Thompson, 1984; Hansen, 1991; Berkman, 2001; Hall and Deardorff, 2006).

In response, state legislatures began to regulate lobbying activities (Strickland, 2021). Massachusetts, one of the states most connected to the early development of associational life (Brown, 1974), set the benchmark by passing a lobbyist registration law in 1890. Wisconsin, another state with a strong history of associations, passed a similar measure in 1899. This was followed by Maryland in 1901. By 1927, 20 states required lobbyists to register, 32 had some limitations on lobbying activities, and nearly all had anti-bribery statutes (Pollock, 1927). These laws preceded Congress' first permanent lobby statute (enacted in 1946) by several decades.3 Though enforcement was uneven across states (Lane, 1964, p. 154–162), lobbyists and associations generally complied with the laws.

In combination, then, the growth in associational membership, coupled with evidence of lobbying by associations from these state records, are essential to understanding the development of the American interest group state.

Our analysis relies on three case studies: the Patrons of Husbandry of the National Grange, better known as the Grange (an agricultural association); the Big Four railroad brotherhoods (the Brotherhoods of Locomotive Engineers, Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen, and Railway Trainmen, and the Order of Railroad Conductors; organizations of skilled workers involved in running trains); and the American Bankers' Association (ABA) and its state affiliates (a professional business class). We choose to examine these organizations because all were prominent, well-funded organizations with political goals that had members they could mobilize for or against causes and candidates, thereby buttressing inside lobby efforts.4 Each association also functioned with some form of federated structure, with the Grange and ABA following a national-state-local structure, and the brotherhoods a national-local structure with a more flexible arrangement for state intermediaries.5

Yet, their members were drawn from different segments of the population. The Grange was a broad-based association of farmers that allowed both men and women to join, the railroad brotherhoods allowed membership only for white men in particular railroad jobs, and ABA's members were banking institutions. These distinct memberships allow us to study how and when large membership associations with political goals turned to direct lobbying and the degree to which it was used. Farmers, skilled labor, and banking interests- major policy areas during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era- all developed legislative agendas. But, as we shall see, this was accomplished at different times and in different ways.

In pursuing this approach, we do not posit specific hypotheses. Instead, we take descriptive, exploratory approach (see Gerring, 2004). Specifically, we aim to illuminate when and how mass mobilization led late 19th and early 20th century associations with distinct political agendas to shift to direct lobbying strategies.

To study the activities of federated voluntary associations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we rely on groups' meticulous documentation of conventions known as “minutes,” “proceedings,” or “reports.” (Hereafter, all variants are referred to as “proceedings”). These proceedings documented the various state associations, national committees, and national leaders' progress and struggles. Accountings of membership were also common; we use this information at the state level for both the Grange (individual members) and the ABA (member banks), and nationally for the railroad brotherhoods. Some groups also provided directories listing local groups; these are the source of local lodge counts for the railroad brotherhoods. We supplement annual proceedings with associations' periodicals; these were a means of communicating more up-to-date information to affiliates, members, and the public.

To study lobbying in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we rely on state legislative lobbying registration records. State legislatures were the first governments in the world to require lobbyists to register on a repeated basis (Opheim, 1991). The practice spread, resulting in 20 states requiring some form of lobbyist registration by 1927.6 These states were primarily located in the Northeast and Midwest (Strickland, 2021). When registering with state officials, lobbyists were required to provide both their names and the names of the interests they represented. Most state archives and libraries have retained dockets of legislative agents and counsel,7 providing a vital link to the past and allowing us to study the degree to which the rise of associations led to direct lobbying.8

Over several years, an author visited archives or libraries in numerous states and collected lobbyist registration forms dating from 1891 to the present. The agent and counsel forms list client organizations, durations of employment, and subject matters of lobbying efforts.9 The oldest lobby records any other study has examined data from the 1960s: Lane (1964) compared numbers of registered lobbyists and client organizations across states to understand compliance with lobby laws. Gray and Lowery (1996) examined client organization totals from 1975 and later years to understand how communities of organized interests grow over time. Studies of Gilded Age or Progressive Era lobbying do not examine lobby records at all and, in studies on other topics, the influence of organized interests during these periods is estimated using proxies (e.g., economic statistics or membership totals) (e.g., Thompson, 1984; Baack and Ray, 1985; Ainsworth, 1995; Clemens, 1997; Barney and Flesher, 2008). Carroll and Hannan (2000) make considerable progress in explaining the demographics of business firms and other organizations, they do not examine instances of political lobbying. Thus, our study is the first to empirically observe historical lobby efforts directly, and therefore the first to do so in relation to data collected on large voluntary associations that were active at the time lobbyist registration laws were first enacted in the states.

The first case we examine, the Patrons of Husbandry of the National Grange (hereafter, the Grange), was formed in 1867 by Oliver Kelley, a Mason and bureaucrat with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Its goal was to create a national voice for farmers (both men and women), especially in the South and West. It rose to prominence in the early 1870s, and its members in some states moved toward partisan political action. As shown in Table 1, which illustrates family memberships in the Grange, the organization grew quickly in the early 1870s. It scored successes by pushing for “Granger Laws” regulating railroads and shipping rates in the states, but many of these laws were later gutted by courts. Soon after, Grange membership tapered off until leadership pursued a more moderate, reform-oriented strategy that mobilized new members; it capitalized on its substantial membership to pressure Congress on issues such as tariffs (Velk and Riggs, 1990), rural free (postal) delivery (Kernell and McDonald, 1999), and road improvements (Wells, 2006). This so-called second Granger movement—a reinvigoration of the original association—caught on among farmers in the industrialized Northeastern states and in some Midwestern and Western states. By the late 1880s, the Grange was once again a growing association of farmers seeking support for agriculture's role in an ever-urbanizing society. Ultimately, the Grange became a key part of rural life in many regions of the country.

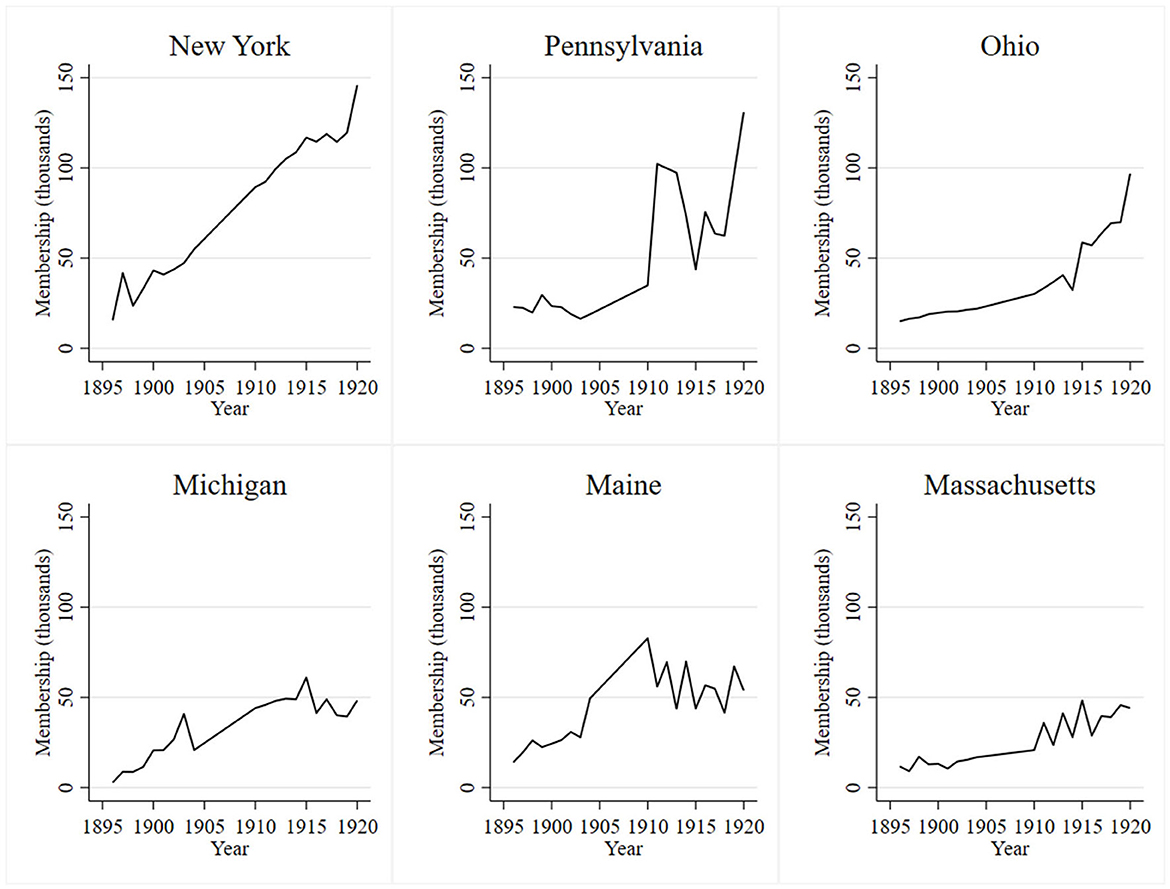

Despite national goals, the states and state lobbying were key to the Grange's reemergence. To illustrate this, Figure 1 shows the growth in Grange membership in the six states where it had the highest membership—New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maine, Michigan, and Massachusetts—from 1896 until 1920 (excluding 1905 to 1909, when the Grange did not report dues for any state). Membership was calculated by the authors from per capita dues at the rate of $0.05 annually per member from the state to the national body, as recorded in the annual proceedings of the National Grange. The Grange had sizable membership in all six states by the 1890s, especially when we consider that only farmers could join and that, except Maine, these states were predominantly urban.10 A comparison of membership and farms in a state is instructive of the group's reach and influence. In 1920, there were approximately 44,000 members and 32,001 farms in Massachusetts; approximately 146,000 Grange members and 193,195 farms in New York; and in Ohio, approximately 96,850 members and 256,695 farms. The growth noted in Table 1 was heavily driven by these states where industrialization and modernization reshaped rural life.

Figure 1. Grange Membership in Six Key States, 1896–1920. Note: Membership totals generated from per member state payments to the national body. No data were published from 1905 to 1909.

Critically, it was in these states with large, vibrant Granges that the association took on active legislative agendas. For example, the activities reported to the national body in 1915 by the six state Granges shown in Figure 1 are extensive (National Grange, 1915). In the Mid-Atlantic, the New York Grange listed its main successes as stopping two bills: adverse reforms to the dairy industry and an education reform bill that would have hurt rural schools (82). In Pennsylvania, the membership “exhibited sovereign citizenship by the fights they have waged for local option, business roads without bonds, practical schools and a just distribution of the burdens of taxation” (90). In the Midwest, the Ohio Grange claimed legislative victory on all aspects of its agenda, though specific policies were not detailed in the report. The Michigan Grange reported a mixed session, with successful efforts to improve the standing of the state's agricultural college, a market commission law, appropriations for state and county fairs, and “[a] law regulating the galvanizing of wire fencing” (68). Finally, in New England, Maine noted specific advocacy for woman suffrage and road improvements, issues that affected both state and national governments, along with “other lines of public policy” (62). In Massachusetts, the Grange noted several accomplishments, specifically “the packing and grading of apples; Farmer's [sic] Land Bank Bill; public markets in towns of over 10,000; also, in opposing the appointment of a commission to investigate all agricultural methods” (66).

In total, the largest Grange affiliates were very politically active, and the increases in membership starting in the mid- to late-1880s allowed it to become the preeminent farmers' association of the early 20th century. Its move into direct lobbying occurred prior to, and continued along with, the association's continued growth throughout the early 20th century. To illustrate this pattern, we rely on lobbyist registration data, presented in Table 2. States are listed in the first column, according to the age of their earliest available records.11 The second column shows years for which lobbyist records are available from before 1925.12 The third column presents numbers of legislative sessions for which lobbyist records are available for each state, and the fourth column indicates the number of those sessions during which the Grange registered at least one lobbyist.

From Table 2, we see that the Grange maintained a strong lobbying presence in most Northeastern states, especially Massachusetts, New York, and New Hampshire. Ohio and Kansas are the only other states in which the Grange appeared regularly. These trends align with the Grange's general membership numbers by region (see Table 1; Tontz, 1964, p. 147). Furthermore, the average number of lobbyists the Grange authorized in each state during sessions in which it lobbied was highest in states where it maintained the most persistent lobby presence. In Massachusetts, for which the most data are available, lobbying occurred across the period—one lobbyist consistently from 1891 to 1899, with a period of little to no lobbying in the first decade of the 20th century, followed by consistent lobbying with more than one lobbyist (and up to 11 in 1919) from 1914 into the early 1920s. In 1915, the year we examined associational records, the Grange had four lobbyists in Massachusetts and two in Ohio; New York lists none. In less populated states with a strong Grange presence, the group registered three lobbyists in New Hampshire and four in Kansas.

These trends in lobbying across states suggest that, for the Grange, mobilization, as measured by members in state associations of the Grange, was correlated with a greater use of lobbyists (in terms of numbers and frequency of lobbying efforts). Hence, the National Grange could rely on its strongest state associations to advocate for items on its national agenda in particular state legislatures. It also provided leeway to state and local associations to pursue their own needs and interests.

The Big Four railroad brotherhoods began as fraternal efforts to provide skilled railroad workers with sickness and injury benefits (see Arnesen, 1994; Taillon, 2001, 2002, 2009). At their outset, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (BLE; founded in 1863), the Order of Railway Conductors (ORC; 1868), the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen (and Enginemen by 1907) (BLFE; 1873), and the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen (BRT; 1883) were generally conservative, viewed strikes as a dangerous last resort, and were more apt than other unions to work closely with employers to achieve their goals. But, the Big Four began to move toward direct political action around the turn of the 20th century. As the groups became more political, their already well-established memberships—they each had tens of thousands of members by the mid-1890s, with lodges nationwide—grew at rapid rates, as displayed in Figure 2 (data from Order of Railway Conductors, Proceedings of the Grand Division and The Railway Conductor magazine, various dates). All of these brotherhoods saw continued gains in the early 20th century; by 1920, the BLFE and the BRT reached over 100,000 members each, and the ORC and BLE reached over 50,000 each.

Figure 2. Membership in the “Big Four” Railroad Brotherhoods, 1896–1920. Note: BLFE stands for Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen; ORC stands for Order of Railway Conductors; BRT stands for Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen; and BLE stands for Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers. Data compiled from various sources (e.g., Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (Various Dates), 1922; Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen, 1922; Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, 1922; Order of Railway Conductors (Various Dates), 1922).

The groups' first steps to overcoming their political reluctance involved the creation of state legislative boards that coordinated policy efforts and selected representatives to lobby legislatures. The BRT appears to have been the first to create such boards in the mid-1890s (Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, 1909, p. 156–157), and the BLFE quickly followed suit; by 1900, it had active legislative boards in New York and Ohio (Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, 1900a,b, p. 197, 505). These actions signaled a growing sense that coordinated direct lobbying in the states was necessary for these associations to properly express their demands to government officials.

Soon, the brotherhoods began to form joint legislative boards to maximize their lobbying efforts on shared policy goals. For example, an 1899 conference in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, established rules for collaboration between the BRT, the ORC, and the Order of Railroad Telegraphers (Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, 1901, p. 65–67). These efforts were quite successful. By 1902, the federal government's Industrial Commission (1902, p. 832) noted that, “The railroad brotherhoods have probably a more effective machinery for influencing legislation than any union in any other occupation.” The report goes on to note how, “strong lobbies have from time to time been maintained by the brotherhoods, sometimes throughout the legislative sessions.”

Efforts toward coordination continued as the brotherhoods continued to mobilize. In 1913, all four brotherhoods formed a National Joint Legislative Board (Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, 1914, p. 92) to address national legislation but also offer information and support relative to “anything in the matter of state laws or state legislation bearing directly or indirectly on labor's interests” (Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen, 1915, p. 88). Since not all states had created their own legislative boards, this clearinghouse was a venue to collaborate for policy change. At the national level, a united front forced Congress to pass legislation granting an 8-h workday to many railroad workers in 1916 (Robbins, 1916, 1917). State boards were similarly active and successful. One notable effort was the coordinated effort to pass “full crew” laws, mandating minimum crew sizes on railroad lines of particular classes and lengths. By 1917, 22 states had these highly contentious laws, with 18 of them attributed, at least in part, to the BRT's efforts (including Maryland and Wisconsin in 1911 and Massachusetts, New York, and Nebraska in 1913) (Garrett, 1917).

Given the dominance of the railroads during this time, it is not surprising that the brotherhoods were frequent lobbyists. Table 3 reveals that lobbying was widespread across states for which records exist; only in Rhode Island—by far the smallest U.S. state geographically—did the brotherhoods never employ a lobbyist. The brotherhoods' legislative efforts, thus, touched more states than the Grange. Perhaps this was because, unlike the Grange, the brotherhoods' lobbying efforts do not appear to be contingent on the organization's mobilization in a state, measured here using the number of lodges (individual membership data are unavailable by state).13 Instead, the collaboration fostered by legislative boards seems to have sparked lobbying after the turn of the century. For example, in Massachusetts and Wisconsin, the brotherhoods rarely participated before 1900, but participated in upwards of 90 percent of legislative sessions after that date.

Additionally, a greater number of lobbyists generally registered on behalf of the brotherhoods than the Grange. The average lobbyist count across all four brotherhoods, per session lobbied, ranges from a low of 2.6 in Maryland to more than eight lobbyists per session in Wisconsin. While the Grange could still potentially rely on grassroots pressure tactics (letters and petitions) to supplement its direct lobbying, the Big Four brotherhoods sought to dominate legislative sessions by strategically collaborating, cross-brotherhood, via state legislative boards. These boards likely generated more resources to facilitate extensive lobbying, which allowed the brotherhoods to maintain a significant presence at state legislative sessions. It should also be noted that brotherhood lobbyists were often among the first lobbyists that arrived at legislative sessions.

In total, the mobilization of skilled railroad workers into the Big Four brotherhoods, as measured by counts of local lodges in a state, were not particularly related to the number and frequency of lobbying efforts (i.e., lobbyists) in state legislatures. While overall mobilization of skilled railroad workers in the late 1800s helped to bring the Big Four into closer contact with one another, the collaboration facilitated by joint legislative boards appears to have mattered more to direct lobbying and continued organizational growth throughout the first two decades of the 20th century.

Finally, the American Bankers' Association (ABA), formed in 1875, was an association of bank presidents that came to have affiliates in every state. The ABA saw modest membership growth in its first 25 years, serving as a means for bank presidents to communicate with one another about issues of the day. By the early 20th century, however, the ABA transformed itself into an industry-wide association. Membership totaled 8,362 banks in 1906. By 1920, membership stood at 22,441 banks out of an estimated 32,336 banks in the nation, or 69.4 percent of all banks (American Bankers' Association, 1920, p. 226–27). The ABA became, therefore, a powerful and expansive voluntary professional association.

Though the ABA's membership was naturally inclined toward a close affiliation with state legislatures, the organization's early legislative efforts were not centrally coordinated. In time, however, it became apparent that much of the association's work required professional counsel. The association hired a lawyer, Thomas Paton, who served as editor of The Banking Law Journal. So critical and important were Paton's services that the ABA established a General Counsel position by 1908 and hired him “at a salary of $5,000 per annum” (American Bankers' Association, 1908, p. 62).14 By September of that year, Paton was actively working with the ABA's new Standing Law Committee. In addition to presenting a lengthy report on legislative efforts in the states (169–177), the committee held a conference of “legislative committeemen of all the State Bankers' Associations” to receive feedback on potential legislation, improve, and create uniformity in, existing laws, and “establish an effective working organization under the auspices of the Standing Law Committee by which necessary legislation in the various States may be furthered” (American Bankers' Association, 1908, p. 177).

At the start of 1911, Paton announced that the ABA had “an active and aggressive campaign… planned for the promotion of uniform legislation” (American Bankers' Association, 1911, p. 393). Eleven pieces of model legislation were circulated; these addressed issues such as false statements used to obtain credit, the use of explosives during burglaries, and uniform bills of lading. In most cases, draft legislation was sent to state associations, but Paton also stated, “Requests for drafts of certain of these laws, received directly from members of the legislatures in a number of States who recognize the desirability of such legislation, have been complied with also” (393). To catalog the progress of these activities, the Journal also published a list of state legislative passages (American Bankers' Association, 1912, p. 365–370). This organization and outreach concerning state legislation illustrates how the ABA mobilized its member banks and served as a key lobbyist and legislative subsidy by the 1910s.

To further illustrate the ABA's presence, Table 4 displays totals of lobbyists hired by the American Bankers' Association or state affiliates. It also splits states, when records are available, into the period up to 1908 (before Paton was hired by the ABA) and from 1909 onwards (when Paton implemented a national strategy for pushing state legislation). Three points stand out. First, bankers, like the Grange, were more regionally clustered in their lobbying activity, with a particularly strong presence in the Northeast and major Midwestern states. Unlike the Grange, though, the ABA had a presence in the Plains and the South, even if not as strong; this pattern matches the regional concentration of banking and capital during this period (Bensel, 2000, p. 19–100).

Second, the ABA's frequency of lobbying and the average number of lobbyists per session lobbied shows the organization to be less active in the legislatures than the Big Four railroad brotherhoods and perhaps not as active as the Grange in similarly-ranked states. As a privileged association, it likely had prior connections to some state legislatures—and perhaps some legislators had been in banking at one time. It also seems likely that legislators, fearing corruption charges, were more reluctant to accept public advances from bankers. Thus, while a lobbyist(s) could be effective, there was no need for multiple lobbyists in each state, in almost every session. As a result, there is no correlation between the number of member banks and the amount of lobbying taking place.15

Thus, the mobilization of bankers into the ABA was not an immediate catalyst for direct lobbying. Unlike the Grange, where more members equated to more instances of lobbying, and unlike the Big Four railroad brotherhoods where the general mobilization of skilled workers led to cross-association collaboration on joint legislative boards, the ABA's appearance in state lobbyist dockets can be attributed almost entirely to the work of lawyer Thomas Paton, a single individual hired by the ABA to facilitate this work.

This work set out to explore how the relationship between mobilization and direct lobbying in state legislatures during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. We find that our three case studies—the Grange (agricultural), the Big Four railroad brotherhoods (skilled labor), and the American Bankers' Association (professional/finance)—all gained membership during the era yet varied in their transitions to, and strategies for, direct lobbying. These findings, drawn from data that have not been previously used in combination in academic literature, demonstrate how comparisons across group activities may be made, both during the Progressive Era and over time. We encourage scholars to build on these insights to expand the body of knowledge on civic engagement and social capital.

The Grange was the least specialized of these organizations: those living in rural communities of the Northeast and parts of the Midwest were the main targets of its mobilization efforts. Among the three organizations we examined, membership mattered the most for this citizen-based group. We find a clear correlation between larger state membership and more direct state legislative lobbying, suggesting that mass mobilization may have played a critical role in its lobbying strategy. We see similar patterns today with membership-based associations, including groups that represent farmers, the handicapped, and women (Walker, 1991).

The Big Four railroad brotherhoods were organizations of specialized railroad trades, and as such were not representative of the common laborer; their focus on a specific area of legislative interest brought them into considerable contact with one another and with legislators. Though all four gained members across the Progressive Era, there is only a weak correlation between mobilization, measured as the number of lodges in a state and the frequency and number of registered lobbyists. Instead, for the brotherhoods, the creation of inter-organizational legislative boards around the turn of the century appears to have been more of an impetus for widespread, direct lobbying in the states than the simple growth in membership. This is likely because of the coordination needed by leaders across all four brotherhoods to ensure that legislative goals were clear, much like what we see today with coalitions of interest groups (Hula, 1999).

Finally, the American Bankers' Association was a professional membership association of banks, representing white-collar interests. The ABA became a consistent lobbyist in state legislatures only after the hiring of a single individual, Thomas Paton, in 1908 to organize and coordinate state legislative efforts. More member banks did not correlate with more lobbying or more lobbyists per session lobbied; likely, the lack of a connection stems from the top-down approach used by the ABA, other avenues of influence open to bankers, and, potentially, concerns about the appearance of corruption. This points to the importance of professionalism in lobbying campaigns, akin to the role of organizational resources in modern interest group lobbying (Baumgartner et al., 2009, p. 199–212).

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that analyses of the relationship between of mass mobilization and lobbying strategies can be conducted across early 20th century associations. Different types of associations developed direct lobbying repertoires, and they did so in different ways. It is therefore imperative that scholars seek to expand on these findings by conducting more comparative work within this time period across an even broader range of associations, as well as across time, by directly comparing the conditions that give rise to lobbying regardless of era.

To the former point, the Gilded Age and Progressive Era were periods in which a predominantly rural, agricultural society moved to an increasingly urban, industrial, and diversified economy—a key factor in stimulating group development (Truman, 1951). As associations became more commonplace, there were increasing demands for government action at both the federal and state levels. Likely, where, when, and how groups lobbied was dictated by legislative interest—often measured by presence at hearings (Tichenor and Harris, 2002–2003)—and state capacity for policymaking in particular areas, potentially related to legislative professionalism (e.g., Teaford, 2002; Squire and Hamm, 2005; Squire, 2012). Federal and state lobbying efforts could also have affected one another, potentially creating a situation in which one (un)successful lobbying effort begat another (e.g., Leech et al., 2005). If so, this may have affected the degree to which state and local affiliates of federated associations gained more members or spawned more local groups. Previous research suggests that the density of a state affiliate's local groups and membership may become large enough that further growth is made difficult (Chamberlain et al., 2019, 2020), but lobbying successes may expand an association's popularity, leading to more growth, or it could sap the membership of its initial drive, leading to declines.

The findings of these can serve as the basis for studies of the latter point: comparisons to interest group lobbying in the states today. The contexts in which associations turned to politics and the choice and effectiveness of lobbying techniques are all considerations echoed by modern interest group scholarship (e.g., Hojnacki et al., 2012). We encourage scholars particularly to examine the past outside lobbying efforts and campaign finance activities (as in Gais, 1996) of organized interests, which remain generally uncharted. At times, this may involve conducting large-sample, quantitative studies as more data from this era are compiled; but it also suggests that a greater appreciation for comparative case studies of associations and groups across time may reap benefits, particularly when studying the effects of mass mobilization. By building on our findings, scholars will create a more robust picture of the development of lobbying across American history. Like Tichenor and Harris (2002–2003), we encourage others to push away “conceits of modern times” and look to the past for new insight.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^But see, in political science, Gamm and Putnam (1999), Sanders (1999), Skocpol et al. (2000), Crowley and Skocpol (2001), Skocpol (2003). In history, Wiebe (1967), Galambos (1970), Link and McCormick (2013[1983]). In sociology, Clemens (1997).

2. ^During Reconstruction, lobbyists were portrayed as sources of corruption, and as they became more entrenched in Congress, calls grew for lobbying regulations. A registration measure was enacted, but it applied only to lobbyists active in the House during one session. In the states, the rise of lobbyists also precipitated popular concerns over corruption. Constitutional bans on lobbying and bribery emerged in several states. Scandals still occurred however, and states began to transition from outright bans to registration and disclosure by the 1890s and 1900s (Lane, 1964; Thompson, 1984).

3. ^The first use of “lobbyist” in a political context was in 1829 in Albany, New York (Lane, 1964, p. 19).

4. ^For a modern perspective on outside-inside lobbying strategies, see Hall and Reynolds (2012).

5. ^At times, different brotherhoods also cooperated based on company rail lines.

6. ^Registration spread more slowly throughout the 1920s and 1930s, but after Congress enacted its first permanent registration statute in 1946, six more states adopted registration within two years. A third wave of transparency followed in the 1960s and 1970s. By 1975, all states required lobbyist registration.

7. ^In Massachusetts, if lobbyists desired to speak with legislators personally, they were required to sign their names in a “docket of legislative agents” maintained by the legislature's Sergeant-at-Arms. Anyone who sought to testify for legislative hearings had to sign a “docket of legislative counsel.” The early distinction between agents and counsel was adopted in some other states, including Kansas, Maryland, Rhode Island, and South Dakota.

8. ^Non-registered or “shadow” lobbying is a concern in the modern era (LaPira, 2015; Strickland, 2019). Lobbyists during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era might also have failed to register. Evidence, however, suggests that, while strict enforcement generally did not occur (except in Wisconsin; Lane, 1964, p. 154-62), lobbyists continued to register but failed to submit expense statements, or submitted inaccurate reports. Thus, lobbyist registrations from the Gilded Age and Progressive Era are likely reliable.

9. ^For an example of a lobbyist registration form from the Gilded Age, see Strickland (2021).

10. ^New York, Massachusetts, Ohio, and Pennsylvania had majority-urban populations in both the 1910 and 1920 Census, and Michigan was majority urban by 1920.

11. ^Alaska and Kentucky required lobbyists to register before 1925 but early records could not be located by archival staff.

12. ^The Illinois Senate enacted a resolution requiring lobbyists to register in 1915. The resolution applied only to lobbyists soliciting senators. Illinois enacted a permanent lobby statute in 1959.

13. ^Rankings of states based on lodges per type of railroad employees did not provide any clear connections between size and lobbying, either.

14. ^This annual salary equates to $145,000 in 2020 dollars (Williamson, 2021).

15. ^The percentage of member banks relative to total banks does not change the interpretation; a greater percentage of banks joined in states without many banks.

Ainsworth, S. (1995). Electoral strength and the emergence of group influence in the late 1800s: The Grand Army of the Republic. Am. Polit. Q. 23, 319–38. doi: 10.1177/1532673X9502300304

American Bankers' Association (1908) Proceedings of the Thirty-Fourth Annual Convention of the American Bankers' Association. New York: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co.

American Bankers' Association (1912). Legal notes and opinions. J. Am. Bankers' Associat. 5, 365–70.

American Bankers' Association (1920). Membership by states, August 31, 1920. J. Am. Bankers' Associat. 13, 226–27.

Arnesen, E. (1994). ‘Like Banquo's ghost, it will not down': The race question and the American railroad brotherhoods, 1880–1920. Am. Historical Rev. 99, 1601–33. doi: 10.2307/2168390

Baack, B. D., and Ray, E. J. (1985). Special interests and the adoption of the income tax in the United States. J. Econ. History 45, 607–25. doi: 10.1017/S0022050700034525

Barney, D. K., and Flesher, T. K. (2008). A study of the impact of special interest groups on major tax reform: agriculture and the 1913 income tax law. Account. Historians J. 35, 71–100. doi: 10.2308/0148-4184.35.2.71

Baumgartner, F. R., Berry, J. M., Hojnacki, M., Leech, B. L., and Kimball, D. C. (2009). Lobbying and Policy Change: who Wins, Who Loses, and Why. University of Chicago Press.

Baumgartner, F. R., and Leech, B. L. (1998) Basic Interests: The Importance of Groups in Politics Political Science. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400822485

Bensel, R. F. (2000). The Political Economy of American Industrialization, 1877-1900. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511665004

Berkman, M. B. (2001). Legislative professionalism and the demand for groups: The institutional context of interest population density. Legislat. Stud.Quarterly 26, 661–79. doi: 10.2307/440274

Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (1900b). Untitled report on Ohio state legislative board. Locomot. Eng. J. 34, 197.

Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (1914). National joint legislative board. Locomot. Eng. J. 48, 92.

Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (Various Dates) (1922). Statements of membership. Brotherhood Locomot Eng J. 2, 56.

Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen. (1915). Our national joint legislative board. Locomot. Firemen Enginemen's Magazine 58, 87–90.

Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen. (1922). Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen's Magazine 10, 72.

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen (1901). Proceedings of the Fifth Biennial Convention of the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen. Cleveland: Britton Publishing Company.

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen (1922). Reports of Grand Lodge Officers, Year of 1922. Cleveland: Allied Printing.

Brown, R. D. (1974). The emergence of urban society in rural Massachusetts, 1760–1820. J. Am. History 61, 29–51. doi: 10.2307/1918252

Carpenter, D., and Moore, C. D. (2014). When canvassers became activists: antislavery petitioning and the political mobilization of American women. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 108, 479–98. doi: 10.1017/S000305541400029X

Carpenter, D., Popp, Z., Resch, T., Schneer, B., and Topich, N. (2018). Suffrage petitioning as formative practice: American women presage and prepare for the vote, 1840–1940. Stud. Am. Polit. Develop. 32, 24–48. doi: 10.1017/S0898588X18000032

Carpenter, D., and Schneer, B. (2015). Party formation through petitions: the whigs and the bank war of 1832–1834. Stud. Am. Polit. Develop. 29, 213–34. doi: 10.1017/S0898588X15000073

Carroll, G. R., and Hannan, M. T. (2000). The Demography of Corporations and Industries. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Chamberlain, A., Yanus, A. B., and Pyeatt, N. (2017). From reconstruction to reform: modernization and the interest group state, 1875–1900. Soc. Sci. Hist. 41, 705–30. doi: 10.1017/ssh.2017.28

Chamberlain, A., Yanus, A. B., and Pyeatt, N. (2019). Revisiting the ESA model: a historical test. Interest Groups Advocacy 8, 23–43. doi: 10.1057/s41309-018-00046-5

Chamberlain, A., Yanus, A. B., and Pyeatt, N. (2020). Expanding the energy-stability-area model: Voluntary membership associations in the early 20th century. Interest Groups Advocacy 9, 57–79. doi: 10.1057/s41309-019-00075-8

Clemens, E. S. (1997). The People's Lobby: Organizational Innovation and the Rise of Interest Group Politics in the United States, 1890–1925. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Crowley, J. E., and Skocpol, T. (2001). The rush to organize: Explaining associational formation in the United States, 1860s−1920s. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 45, 813–29. doi: 10.2307/2669326

Gais, T. (1996). Improper Influence: Campaign Finance Law, Political Interest Groups, and the Problem of Equality. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.14656

Galambos, L. (1970). The emerging organizational synthesis in modern American history. Bus. Hist. Rev. 44, 279–90. doi: 10.2307/3112614

Gamm, G., and Putnam, R. D. (1999). The growth of voluntary associations in America, 1840–1940. J. Interdisciplin. History 29, 511–57. doi: 10.1162/002219599551804

Garrett, P. W. (1917). The administration of the “full-crew” laws in the United States. State Research, Supplement to Vol. IV, ‘New Jersey,' No. 4. Newark: New Jersey Bureau of State Research.

Gerring, J. (2004). What is a case study and what is it good for? Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 98, 341–54. doi: 10.1017/S0003055404001182

Gray, V., and Lowery, D. (1996). The Population Ecology of Interest Representation: Lobbying Communities in the American States. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.14367

Gray, V., and Lowery, D. (2002). State interest group research and the mixed legacy of Belle Zeller. State Polit Policy Quarterly 2, 388–410. doi: 10.1177/153244000200200404

Hall, R. L., and Deardorff, A. V. (2006). Lobbying as legislative subsidy. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 100, 69–84. doi: 10.1017/S0003055406062010

Hall, R. L., and Reynolds, M. E. (2012). Targeted issue advertising and legislative strategy: the inside ends of outside lobbying. J. Polit. 74, 888–902. doi: 10.1017/S002238161200031X

Hansen, J. M. (1991). Gaining Access: Congress and the Farm Lobby, 1919-1981. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Herring, P. (1929). Group Representation before Congress. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hojnacki, M., Kimball, D. C., Baumgartner, F. R., Berry, J. M., and Leech, B. L. (2012). Studying organizational advocacy and influence: Reexamining interest group research. Annual Rev. Polit. Sci. 15, 379–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-070910-104051

Hula, K. W. (1999). Lobbying Together: interest Group Coalitions in Legislative Politics. Washington, DC.: Georgetown University Press.

Industrial Commission (1902) Final Report of the Industrial Commission Volume XIX. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Kernell, S., and McDonald, M. P. (1999). Congress and America's political development: the transformation of the Post Office from patronage to service. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 43, 792–811. doi: 10.2307/2991835

Lane, E. (1964). Lobbying and the Law. Berkeley: University of California Press. doi: 10.1525/9780520332263

LaPira, T. M. (2015). “Lobbying in the shadows: How private interests hide from public scrutiny, and why that matters,” in Interest Group Politics, 9th Edition, eds Allan J. C, Burdett A. L., and Anthony J. N. (Washington, DC: CQ Press), p. 224–248. doi: 10.4135/9781483391786.n11

Leech, B. L., Baumgartner, F. R., La Pira, T. M., and Semanko, N. A. (2005). Drawing lobbyists to Washington: Government activity and the demand for advocacy. Polit. Res. Q. 58, 19–30. doi: 10.1177/106591290505800102

National Grange (1915). Journal of Proceedings of the National Grange of the Patrons of Husbandry, Forty-Ninth Annual Session. Concord, NH: Rumford Press.

Odegard, P. (1928). Pressure Politics: The Story of the Anti-Saloon League. New York: Columbia University Press.

Opheim, C. (1991). Explaining the differences in state lobby regulation. Western Polit. Quarterly 44, 405–21. doi: 10.1177/106591299104400209

Order of Railway Conductors (Various Dates) (1922). Proceedings of the Grand Division 1905–1911, biennial; 1913–1922, triennial. Various Publishers.

Pollock, J. K. (1927). The regulation of lobbying. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 21, 335–41. doi: 10.2307/1945182

Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. J. Democracy 6, 65–78. doi: 10.1353/jod.1995.0002

Robbins, E. C. (1916). The trainmen's eight-hour day. Polit. Sci. Q. 31, 541–57. doi: 10.2307/2141627

Robbins, E. C. (1917). The trainmen's eight-hour day II. Polit. Sci. Q. 32, 412–28. doi: 10.2307/2142076

Sanders, E. (1999). Roots of Reform: Farmers, Workers, and the American State, 1877–1917. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Schlesinger, A. (1944). Biography of a nation of joiners. Am. Historical Rev. 50, 1–25. doi: 10.2307/1843565

Schlozman, K. L., and Tierney, J. T. (1986). Organized Interests and American Democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

Skocpol, T. (2003). Diminished Democracy: From Membership to Management in American Civic Life. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Skocpol, T., Ganz, M., and Munson, Z. (2000). A nation of organizers: The institutional origins of civic voluntarism in the United States. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 94, 527–46. doi: 10.2307/2585829

Squire, P. (2012). The Evolution of American Legislatures: Colonies, Territories, and States, 1619-2009. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.4401998

Squire, P., and Hamm, K. E. (2005). 101 Chambers: Congress, State Legislatures, and the Future of Legislative Studies. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press.

Strickland, J. (2019). A paradox of political reform: shadow interests in the U.S. states. Am. Polit. Res. 47, 887–914. doi: 10.1177/1532673X18788049

Strickland, J. (2021). A quiet revolution in state lobbying: government growth and interest populations. Polit. Res. Q. 74, 1181–96. doi: 10.1177/1065912920975490

Taillon, P. M. (2001). Americanism, racism, and ‘progressive' unionism: the railroad brotherhoods, 1898–1916. Aust. J. Am. Stud. 20, 55–65.

Taillon, P. M. (2002). ‘What we want is good, sober men': Masculinity, respectability, and temperance in the railroad brotherhoods, c. 1870–1910. J. Soc. Hist. 36, 319–38. doi: 10.1353/jsh.2003.0037

Taillon, P. M. (2009). Good, Reliable, White Men: Railroad Brotherhoods, 1877–1917. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Teaford, J. C. (2002). The Rise of the States: Evolution of American State Government. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Thompson, M. S. (1984). The “Spider Web”: Congress and Lobbying in the Age of Grant. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Tichenor, D. J., and Harris, R. A. (2002–2003). Organized interests and American political development. Polit. Sci. Quarterly 117, 587–612. doi: 10.2307/798136

Tichenor, D. J., and Harris, R. A. (2005). The development of interest group politics in America: Beyond the conceits of modern times. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 8, 251–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.7.090803.161841

Tontz, R. L. (1964). Memberships of general farmers' organizations, United States, 1874–1960. Agric. Hist. 38, 143–56.

Truman, D. B. (1951). The Governmental Process: Political Interest and Public Opinion. New York: A.A. Knopf.

Velk, T., and Riggs, A. R. (1990). Getting down to business: Tactics and ethics of the National Grange, 1905–1911. Am. Econ. 34, 46–54. doi: 10.1177/056943459003400207

Walker, J. L. (1991). Mobilizing Interest Groups in America: Patrons, Professionals, and Social Movements. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.12845

Wells, C. W. (2006). The changing nature of country roads: Farmers, reformers, and the shifting uses of rural space, 1880–1905. Agric. Hist. 80, 143–66. doi: 10.1525/ah.2006.80.2.143

Williamson, S. H. (2021). Seven ways to compute the relative value of a U.S. dollar amount, 1790 to present. Measuring Worth website www.measuringworth.com/uscompare/.

Zeller, B. (1937). Pressure Politics in New York: A Study of Group Representation before the Legislature. New York: Prentice Hall.

Keywords: interest group, state politics, lobbying, federalism, Progressive Era, the Grange, railroad brotherhoods, American Bankers Association

Citation: Chamberlain A, Strickland J and Yanus AB (2023) The rise of lobbying and interest groups in the states during the Progressive Era. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1123332. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1123332

Received: 13 December 2022; Accepted: 20 March 2023;

Published: 05 April 2023.

Edited by:

Anthony Nownes, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, United StatesReviewed by:

Emily Schilling, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Chamberlain, Strickland and Yanus. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adam Chamberlain, YWNoYW1iZXJAY29hc3RhbC5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.