- Department of Political Science and History, Panteion University, Athens, Greece

Research on political incivility in social media has primarily been focused on the types and frequency of impolite or uncivil language used to attack politicians. However, there is so far little evidence on the uncivil use of organic targeting tactics. We define organic targeting tactics as the ways through which users can utilize the Twitter tagging conventions (hashtags and mentions) and its “reply” feature to target specific publics and accounts other than those in their followers' list. In the discussion on the study of political incivility on Twitter we introduce organic targeting tactics as another critical element of political incivility which may involve the violation of several political civility norms or essentially alter the intensity of their violation. Based on data from Greek Twitter this paper identifies and explores how users exploited the hashtag, mention, and reply feature of Twitter to target political out- and in-group politicians and publics and wide audiences with uncivil political messages. The dataset includes 101.512 tweets containing the “Syriza_xeftiles” hashtag posted during the period between January 2015 and early June 2019, obtained from the Twitter Search API. The dataset contains only tweets from Twitter user accounts that have posted at least 30 #Syriza_xeftiles tweets during the period under study. Analyses organic targeting tactics were based on an inductive lexicon-based approach. Evidence presented in this paper indicated that Twitter users gradually learned how to weaponize the hashtag, reply, and mention features of Twitter to target more and more regularly a variety of political accounts, publics, and audiences in Greek Twitter with uncivil political narratives. The weaponization of these Twitter features often involved the combination of several political incivility dimensions, which apart from the use of insulting utterances included the use of deception through hashjacking and the discursive dimension, which in effect constituted space violations, interruptions, and discussion prevention. We argue that this practice is indicative of a qualitatively different kind of political incivility because it does not simply aspire to establish ad-hoc political publics where incivility is the norm but also to deliberately expose other political and non-political publics to uncivil political narratives. Therefore, the deliberate use of organic targeting tactics can have far wider implications on affective polarization and ultimately on democratic processes.

1. Introduction

Issue-based polarization understood as divisions around one or more policy positions or issues was for over two decades the main focus of the discourse on political polarization (DiMaggio et al., 1996; Duffy et al., 2019). Since the mid of the first decade of the twenty-first century, in parallel with the vast expansion in the use of social media, there was identified another form of polarization, called affective polarization (Iyengar et al., 2012, 2019). Affective polarization emerges when the distance between groups moves beyond principled issue-based political/ideological differences toward social identity differences, as a process where “individuals begin to segregate themselves socially and to distrust and dislike people from the opposing side, irrespective of whether they disagree on matters of policy” (Duffy et al., 2019, p. 6). Affective polarization, the deep division into mutually antagonistic “us” vs. “them” camps, is for some scholars the central mechanism leading to perniciously polarized societies (Somer and McCoy, 2019). While affective polarization has mostly been addressed by scholars in the USA who identified an increased partisan animosity between Democrats and Republicans, research has indicated that the degree of affective polarization in some European Union countries is much higher than in the USA, particularly in Greece, Portugal, and Spain (Gidron et al., 2019; Reiljan, 2020; Wagner, 2021). In the case of Greece, the findings regarding the degree of partisan animosity between the two major parties, ND and Syriza have been described by Reiljan (2020) as “shattering.”

Research has indicated that exposure to and engagement in uncivil behavior is related to political polarization. However, research on the direction(s) of the relationship between political incivility in social media and polarization is still inconclusive. Massaro and Stryker (2012) have suggested that this relationship is more likely to be reciprocal than unidirectional. However, in a study on political blog discussions it was suggested that affective polarization, i.e., a “strong dislike of political opponents,” is responsible for political incivility, “… out of genuine emotion and/or a strategic effort to discredit their arguments” (Suhay et al., 2015, p. 662). On the other side, a body of research mainly in the USA suggests that incivility in social media can contribute to polarization. Anderson et al.'s (2014) study suggested that exposure to uncivil blog comments can contribute to the polarization of perceptions about an issue among different audience segments that hold different values. An experimental study conducted by Suhay et al. (2018) found that exposure to partisan criticism online led to affective and social polarization among USA partisan identifiers. A study by Kim and Kim (2019) indicated that exposure to uncivil opposing comments on Facebook may induce attitude polarization. Buder et al. (2021) study suggested that negativity in users' tweets was most strongly related to indicators of polarization, such as attitude extremity and reduced attitude ambivalence. An experimental study by Muddiman et al. (2021) found that incivility in Twitter messages increased attributions of malevolent motives to the out-group political party, which they consider as “… an antidemocratic attitude because it undermines the incentive to compromise…” (Muddiman et al., 2021, p. 1506).

From a wider perspective, the idea that incivility in social media contributes to political polarization is very appealing to both scholars and political commentators. One reason why is that, at least in certain democratic nations throughout the world, uncivil attacks on politicians and political parties on social media have grown widespread and very visible. Theocharis et al. (2020) study found that around 18% of tweets addressed to Members of Congress in the USA were uncivil. Rheault et al. (2019) have estimated that among the social media messages addressed to Canadian politicians and US Senators around 11% and 15%, respectively, are uncivil. Furthermore, high-profile women politicians are more likely to receive uncivil messages than their male counterparts. What Woolley and Guilbeault call “citizen-built bots” were probably responsible “… for the largest spread of propaganda, false information, and political attacks during the 2016 [USA presidential] election” (Woolley and Guilbeault, 2017, p. 8). In another study, Theocharis et al. (2016) found that, on average, 18% of all tweets mentioning a Greek candidate in the 2014 European Parliament elections were impolite. According to another recent study, almost 10% of the tweets received by less high-profile MPs in the UK were uncivil (Southern and Harmer, 2021). Ward and McLoughlin's (2020) study found that around 2.5% of tweets addressed to MPs in the UK contained some type of direct abuse. In one study in Brazil, it was found that incivility and intolerance in Facebook and news websites comments' section was predominantly used to target politicians, and political actors and institutions (59% and 85.9%, respectively) (Rossini, 2019). Fuchs and Schäfer (2021) study concluded that female politicians on Japanese Twitter daily face hate speech and verbal abuse.

Uncivil behavior against politicians and political parties in social media is often understood as being facilitated by anonymity, the creation of online imaginary personas, and a wider sense of unidentifiability (Suler, 2004; Lapidot-Lefler and Barak, 2012). However, within networked public spheres, incivility is also fuelled by politicians who use strategically such behavior to mobilize voters and to strengthen their political affiliation (Ott, 2017; Rega and Marchetti, 2021; Heseltine and Dorsey, 2022; Frimer et al., 2023). Furthermore, political actors outside the circle of the pre-election campaign strategists and party leadership (from self-styled candidates to regional party officials, semi-autonomous party groups and non-formal party organizations to genuine supporters, various interest groups, and foreign actors, etc.), may strategically engage in their own “subversive” campaigns (Römmele and Gibson, 2020) to smear other parties and candidates (e.g., see Ferrara, 2017; Badawy et al., 2018; Zannettou et al., 2019).

Over time, online political incivility can become normalized, as people who are frequently exposed to or practice it may stop even thinking that what they experience or do is not “normal.” This can be due to desensitization processes that decrease the perception of its harmfulness (Soral et al., 2018), and because the normative borders have been shifted to the point that offensive and abusive language used in politics is increasingly perceived as a standard element of public discourse (Krzyzanowski, 2020). One line of research (e.g., see Chan et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2019) has suggested that political incivility is particularly normalized within politically partisan echo-chambers formed in social media, i.e., fragmented online communities of like-minded individuals who discuss politics and exchange information in ways that reinforce and amplify their pre-established beliefs (Jamieson and Cappella, 2008). The reason why echo-chambers may facilitate the normalization of political incivility is that these offer “…a safer discursive space in which people feel freer to employ extreme language when criticizing out-group members” (Lee et al., 2019, p. 4954).

1.1. On political incivility

Understandably enough, political incivility is difficult to conceptualize and operationalize in empirical research in ways that would ensure the external validity of research results in different national contexts. Differences in political culture, history, and democratic traditions between countries make it difficult to reach a consensus as to how political incivility may be defined and what may constitute observable indications of such behavior. This does not mean that there are fewer challenges in our efforts to define political incivility within a specific national context. As Harcourt argues, politics, after all, is “an uncivil business,” because the outcomes of political antagonism over how democratic governments (re)distribute opportunities, resources, education, jobs, and wealth among citizens are “… by no means “civil”—if by civil, again, we mean that they do not harm, injure, or prejudice members of our shared community” (Harcourt, 2012, p. 350). Therefore, definitions (and perceptions) of political incivility are ultimately connected to social hierarchies and relations of power and simultaneously are constitutive of power relations.

Normative approaches frame political incivility within wider theories of democracy and the associated norms of political conversation. As Papacharissi (2004) argues, democratic norms encourage disagreement about issues. Therefore, “… a conversation may be passionate, heated, and even rude, but it does not necessarily have to be uncivil at the same time” (Papacharissi, 2004, p. 276). Under this perspective, political incivility should not be equated to impoliteness. According to Papacharissi (2004, p. 267), incivility can be identified as a set of behaviors that show disrespect for the collective traditions of democracy, stereotype social groups, and deny people their personal freedoms. As she argues, “…anything less has no lasting repercussions on democracy” Papacharissi (2004, p. 267). Thus, in her perspective, the use of vulgarity, name-calling (e.g., “traitor”), aspersions (e.g., “un-American”), and hyperbole should be considered as instances of impoliteness but not political incivility.

Another approach to the conceptualization of political incivility is to explore citizens' beliefs about what types of generic behaviors may be indicative of political incivility. Different people may perceive differently what constitutes political incivility (Kenski et al., 2020). People may also assess differently the severity of different types of norm violations, depending on their individual characteristics, such as gender, personality traits, ideology, and roles (Bormann, 2022), as well as on their perceptions about the characteristics of the political actors who engage in uncivil behavior, such as their gender and political insider/outsider status (Muddiman et al., 2022).

Stryker et al. (2016, 2022) analysis of survey data, which involved samples from the USA, indicated that perceived political incivility is an overarching construct with three analytically distinct, inter-correlated dimensions: insulting utterances, deception, and discursive. Stryker et al. (2022) suggested that insults include utterances such as name-calling, demonizing political opponents, use of slurs, vulgarity, etc. The discursive dimension includes space violations, preventing taking part in discussions, interruptions, etc. Finally, the deception dimension includes intentionally false or misleading statements, exaggerated statements, and failures to provide reasons or evidence. A distinct and more extreme set of uncivil behaviors is threatening harm and encouraging others to threaten harm. Muddiman (2017) used an experimental research design that involved USA participants who were asked to evaluate situations of norm violations that have been associated with incivility and impoliteness. In particular, she made a distinction between personal-level and public-level incivility. She assumed that in the case of public-level incivility the norms that are predominantly violated are norms about political processes. In the case of personal-level incivility, the violated norms are those of interpersonal politeness. The analysis indicated that the participants did perceive distinct latent personal-level incivility and public-level incivility factors. Personal-level incivility included statements that made use of name-calling, insults, impoliteness, and all kinds of attacks in the context of political campaigns. Even extreme partisan attacks, such as calling the political oppositions “Nazis,” were perceived to be personal-level incivilities, i.e., that they violate norms of interpersonal impoliteness, a finding which was in line with Papacharissi's (2004) argument that these are instances of impoliteness but not of incivility. On the other hand, public-level incivility was identified with situations that are related to a lack of compromise and refusing to work with an opposing political party (Muddiman, 2017). However, as Muddiman et al. (2021) argue, what people understand as personal-level vs. public-level attacks is normatively important. Personal-level attacks imply that politicians are not good at doing their job while public-level attacks imply criminal intent and question their legitimacy.

Sobieraj and Berry (2011) suggested that a special case of a more dramatic type of political incivility is “outrage.” According to them, “outrage discourse involves efforts to provoke a visceral response from the audience, usually in the form of anger, fear, or moral righteousness” (Sobieraj and Berry, 2011, p. 19). Outrage discourse includes types of impolite and uncivil behaviors also described in other typologies, such as insulting language, name-calling, verbal fighting/sparring, character assassination, misrepresentative exaggeration, mockery, conflagration, ideologically extremizing language, slippery slope, belittling, and obscene language, but also emotional display, and emotional language. In their study of TV and radio commentary and talk shows, political blogs, and mainstream newspaper columns in the USA, they used content analysis to identify manifestations of outrage discourse. Their analysis indicated that all or almost all of the TV and radio shows studied and more than 80% of the political blogs incorporated utterances of outrage.

While definitions and typologies of political incivility such as those presented above may provide some help to the study of political incivility in social media, the complexities of political communication in social media raise considerable challenges. In social media political discussions, the fact that many people are rude does not imply that they have a political agenda that is promoted by consistently being rude or uncivil against political opponents. Some of them, at least sometimes, are likely to impulsively use swear words or outright insults just to express their angry feelings. As impoliteness and even extreme political incivility in social media become more and more commonplace, it also becomes more difficult to spot the difference between spontaneous impoliteness or incivility and calculated use of uncivil behavior. An impolite utterance (e.g., “Traitors!”) could be a spontaneous response to an impolite comment by another participant in an ongoing discussion on social media. At the same time, the same utterance, in this or another discussion, may as well be part of a premeditated and systematic effort to attack political opponents not present in this discussion. To determine whether or not a particular message represents a calculated act of political incivility, we also need to identify the tactics used to attack the targets of such behavior.

1.2. Organic targeting tactics on Twitter

Barnard and Kreiss suggest that “targeting refers to the direct or indirect transmission of specific communications to individuals or groups identified in advance...” (Barnard and Kreiss, 2013, p. 2048). Targeting in social media shares some characteristics which are common across many platforms, such as the use of hashtags, but it is highly dependent on the social media platform logic.

In this study, we are focusing specifically on what we call “organic targeting tactics” on Twitter. We define organic targeting tactics as the ways through which users can utilize the Twitter tagging conventions (hashtags and mentions) and its “reply” feature to target specific publics and accounts other than those in their followers' list. In parallel, such tactics are also essentially message amplification tactics. Our assumption is that because Twitter has adopted, and over the years refined, rules regarding abusive behavior1, using Twitter services to implement paid campaigns that promote abusive behavior against political parties, politicians, and their supporters run the risk of being banned. On the other hand, detecting the systematic implementation of organic targeting tactics in uncivil tweets can be a challenging endeavor. As Twitter admits “some Tweets may seem to be abusive when viewed in isolation, but may not be when viewed in the context of a larger conversation. When we review this type of content, it may not be clear whether it is intended to harass an individual, or if it is part of a consensual conversation” (Twitter Help Center, 2022). It is exactly because of such ambiguities that Twitter users with an agenda to spread uncivil messages against political opponents may turn to organic targeting tactics to minimize the risk of being detected and face penalties for violating Twitter's policy on abusive behavior.

In this study we particularly focus on the following tactics:

(a) combinations of uncivil hashtags with other hashtags in the body of a tweet,

(b) combinations of uncivil hashtags with mentions to other Twitter accounts, and

(c) use of uncivil hashtags to replies to other Twitter accounts.

1.2.1. Hashtag-based targeting tactics

As Bruns and Highfield (2015) argue, the structural transformations of the system of political communication which were intensified by social media, have led to the creation of a fragmented and complex system of distinct and diverse public sphericules that are formulated around specific themes and micro-publics or topical issue publics, which co-exist, intersect, and overlap in multiple forms. Various features of social media platforms facilitate users to create and contribute to networked publics such as hashtags, lists of “friends,” or “followers.” Hashtags index keywords on Twitter and allows users to follow topics of their interest, thus aiding the formation of ad-hoc publics around specific themes and topics (Bruns and Burgess, 2011). The use of hashtags is according to Bruns and Burgess “... an explicit attempt to address an imagined community of users who are following and discussing a specific topic” (Bruns and Burgess, 2011, p. 4). Furthermore, hashtags are also “conversational” in nature because they can prompt users to tweet their thoughts on the hashtag topic (Huang et al., 2010). Hashtags may not be just descriptive of a topic but also evaluative. As Zappavigna and Martin (2018) argue, hashtags may also commune affiliation.

Impolite or uncivil hashtags naming a particular politician or a political party (e.g., #RepublicansAreFascists), are essentially calling other Twitter users to express not just their thoughts and feelings in an impolite or uncivil way against the named politician or party but also to bond around this message. The very use of an uncivil hashtag instead of just an uncivil expression in the body of a tweet (e.g., “America knows you are all traitors and guilty, #RepublicansAreFascists,” instead of instead just “America knows you are all traitors and guilty”) is a clear indication that the specific tweet is not merely intended to be circulated among the list of followers of the particular Twitter user or within the context of a specific conversation. It represents a calculated act of political impoliteness or incivility addressed to a wider imagined community of potentially like-minded people.

Combinations of impolite or uncivil hashtags with other hashtags may simultaneously target many publics interested in a potentially huge variety of themes and topics. The systematic use of such hashtag combinations is indicative of premeditated efforts to make attacks on political opponents visible to different publics. Tweets with uncivil hashtags may target in-group and out-group political publics when coupled with hashtags that are commonly used by these communities on Twitter. Such combinations may also target non-partisan political publics or publics formed on Twitter around cultural, educational, or recreational issues and events. Also, the tagging of names of media and news shows is indicative of an intention to target audiences that use Twitter to get news. The deliberate use of hashtags that are commonly used by political or other out-groups in order to expose these publics to counter-messages has been named “hashjacking” (Bode et al., 2015; Darius and Stephany, 2019, 2022). Research on hashjacking has indicated that it is a popular practice particularly by far right (or alt right) groups on Twitter. For example, Bode et al. (2015) found that hashjacking was very popular practice among Twitter users close to the conservative Tea Party movement in the USA during the 2010 midterm election. Darius and Stephany (2019, 2022) found that hashjacking is a popular practice among Germany's political far-right Twitter users to polarize political debates.

The aims of the combined use of impolite or uncivil with other hashtags depend on the targeted publics. The aim of such a tactic addressing out-group political publics may be to penetrate the political opponent's conversation space on Twitter and saturate it with insulting messages thus shattering the opponents' echo chambers, demobilizing political opponent's sympathizers, and destabilizing its ad-hoc communities. Similarly, this tactic can be used to strengthen in-group political identity, mobilize supporters, and so on.

1.2.2. Mention-based targeting tactics

A second organic targeting tactic is the use of tags mentioning other Twitter accounts (e.g., @username). A tweet with a mention of another user's username will appear in the mentioned user's notification tab but not on that user's profile page. Mentions can be used as a tactic to notify a rather small number of users of the content of an uncivil tweet. With the use of a @mention in the body of a tweet a notification is sent to the mentioned Twitter account. Therefore, the primary role of a mention is to grab the mentioned users' attention. Typically mentions are used in Twitter conversations involving several users as a means to specify the user(s) someone is referring to in his/her tweet. However, because Twitter users can mention any other account, deliberate use of mentions in uncivil tweets can be used to target individual accounts belonging to different target groups for different purposes. For example, research on the use of mentions has shown that candidates mention accounts of political opponents primarily as a means to attack them and not to invite them to a public discussion (Hemsley et al., 2018). But mentions of prominent politicians' usernames can also serve another purpose. One can search Twitter for tweets mentioning the username of any user. In this case, the search results will include all tweets that mention a particular username. For example, an uncivil tweet mentioning the Twitter username of a prominent politician will only appear on the notification tab of his/her account. However, any user who performs a Twitter search on “@politician_username” will get among the results all the uncivil tweets mentioning his/her username. This is another Twitter feature that makes the use of mentions a potentially powerful organic targeting tactic.

The mention-based targeting tactics are used (a) to implement micro-targeting, tailoring uncivil messages to the characteristics and expectations of each micro-targeted audience, (b) to spread uncivil messages to a variety of audiences, and (c) to directly address media accounts to influence those who make the news. As McGregor argues, the media and journalists/commentators often use Twitter to report “… online sentiments and trends as a form of public opinion that services the horserace narrative and complements survey polling and voxpopuli quotes” (McGregor, 2019, p. 1070). By flooding their Twitter list of messages with replies and notifications with uncivil tweets against a political party, the hope is not so much to influence newsrooms and journalists' views about this party as to influence their reports and news stories about the “popular” sentiment around it.

1.2.3. Reply-based targeting tactics

Another important tactic to make an uncivil message visible on Twitter is to post tweets as replies to conversations that have been initiated by others. In this case, anyone who is participating in or views such a conversation is likely to also be exposed to this message. This tactic can be more effective when the conversations have been initiated by very popular Twitter accounts (e.g., media outlets, journalists, politicians, celebrities, etc.) with thousands of followers because an uncivil message can thus reach wide audiences. This tactic is particularly useful to users that have not managed to create a critical mass of followers on their own or have been created just for the purpose to attack a political opponent.

Depending on the type of popular accounts, one can target specific audiences. For example, audiences that are in favor of a political party and follow its most prominent accounts can be exposed to counter-messages through replies to their conversations. Such a tactic is practically aiming to create holes in the information bubbles of political opponents. On the other side, replies to popular accounts of political friends can help strengthen the cohesiveness of the information bubbles of like-minded people.

An advantage of hashtag-based targeting tactics is that they facilitate message amplification to a variety of publics. Account-based organic targeting tactics utilize the @mention and “reply” Twitter features to direct messages to specific accounts. Therefore, the advantage of account-based tactics is that they can be utilized to implement micro-targeting campaigns, by adapting uncivil messages to the characteristics and expectations of each micro-targeted audience. The drawback is that they can reach only limited, as compared to hashtags, numbers of target accounts. Performing a premeditated and systematic effort to attack political opponents through the use of uncivil messages on Twitter based on account-based organic targeting tactics is like performing digital “door-to-door” canvassing. You need a lot of resources on the ground to directly reach many people. In Twitter terms, this means that you need to mention and reply to a large number of accounts and differentiate your messages according to what you think will be more effective for each targeted micro-public. All these are likely to be well-beyond the capacities of grassroots “amateur” political campaigners on Twitter. Furthermore, unsolicited replies to tweets of accounts that are outside the personal network of followers could always be perceived as abusive behavior and the receivers can ban you. Excessive use of unsolicited mentions and replies also risks suspension because it violates Twitter rules.

1.2.4. Political civility norm-breaking uses of organic targeting tactics on Twitter

In liberal democracies, a critical political norm is reflected on the belief, or shared code of conduct, according to which political parties, politicians, and their supporters who engage in a public partisan political activity should not experience intimidation and disruptions from people who hold different political views. This norm is injunctive in the sense that it is based on an ideal about how political parties, politicians, and ordinary citizens should and should not behave when engaging in democratic political processes (Muddiman et al., 2022). It is derived from a more generic political norm which is based on the expectation that the organization and conduct of democratic political processes are free from outside manipulation or disruption, which in turn is based on the democratic norm of mutual toleration (Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2019). In the context partisan political activities performed in physical spaces (e.g., a pre-election public speech by a party leader in a concert hall, a press conference, etc.), systematic attempts by members of political out-groups to disrupt them and intimidate those who participate are easier to identify as cases of political incivility. Depending on the political process that is disrupted by uncivil behavior, the consequences of breaking this norm can potentially have grave consequences for democracy. The disruption of a joint session of the U.S. Congress in the process of affirming the presidential election results on January 6th, 2021, is, among other things, a high-profile case of violation of this norm. As more and more partisan political activities and broader democratic political processes take place online, it is important to study how organic targeting tactics on Twitter may disrupt such processes and what their implications may be.

According to Sydnor (2019a), people assess the incivility of an online message on the basis of the message's substance, the tone of the message and the message sender. In the discussion on the study of political incivility in social media, focusing in particular on Twitter, we introduce the organic targeting tactics as another critical element that needs to be considered. What interests us more here is under what conditions the organic targeting tactics adopted when posting a tweet may be considered as violations of political civility norms or essentially alter the intensity of their violation.

A racist comment by an “anonymous” user in Twitter against a politician can be considered as a typical case of political incivility, because, as Papacharissi (2004) argues, “it is when people demonstrate offensive behavior toward social groups that their behavior becomes undemocratic” (p. 267). When this racist tweet has no hashtags, and is just posted in a conversation initiated by the “anonymous” user, no other public is targeted apart from those who participate in the conversation and the followers of this user. Therefore, it can be assumed that the potential harm that is done is mainly contained within this user's “micro-public,” i.e., the group of people who are actively interested to know and perhaps discuss the views of this particular user. The nature and intensity of the potential harm of the same racist comment essentially changes when this “anonymous” user chooses to also (a) use a hashtag that is commonly used by the political party of the politician who is the victim of the racist attack, and/or (b) mention the Twitter username of the politician(s) who is the victim of the racist attack, and/or (c) post this racist comment as a reply in a Twitter conversation initiated by this politician(s). In this case, the “anonymous” user purposefully exposes the targeted politician and his/her followers to this racist comment. Such a behavior adopts an intentionally confronting mode of conduct and could be identified as a case of “getting in an opponent's face” which, according to Stryker et al. (2016), constitutes a kind of “space violation.” Aiming to confront their opponent head-on, such tactics sometimes also involve deception, which according to Stryker et al. (2016) is another dimension of political incivility. For example, the use of hashtags that commune affiliation to a political party or politician in order to expose publics close to them to insulting comments is a misleading practice. We argue that even comments on Twitter that could be characterized as merely impolite in the context of conversations within a user's own “public” (personal-level incivility) could become politically uncivil when combined with organic tactics aimed at “space violation,” i.e., target directly the accounts and publics of a political opponent (public-level incivility) (Muddiman, 2017).

Tweets with insulting comments against a political party or its supporters that exploit Twitter's features to target non-political publics, violate, at the most basic level, a generic cooperative communication process norm (Bormann et al., 2022). This is because the political content of such tweets is largely unrelated to the non-political topics of conversations among members of these publics. In terms of political incivility, such tactics represent cases of deception and space violation because those who use them practically exploit trending non-political hashtags and non-political influencers (through mentions or replies to their conversations) to spread insulting messages. From a wider social perspective, organic tactics, by exploiting the “super-spreading” capacity of popular accounts and of trending non-political topics on Twitter, are parasitic in nature because they aim to feed off the social networks created and maintained by unsuspecting users.

The paradox regarding the norm-breaking capacity of organic targeting tactics is that when combined with political arguments that are stated in ways that are respectful to the views of political opponents may promote democratic deliberation and encourage political participation. For example, in democracies, mainstream parties, candidates, and political activists, in their efforts to reach as many people as they can during their campaigns, they regularly target a wide variety of non-political publics, and audiences that are not at all interested in politics or are distrustful and politically disaffected. By doing so, they do commit violations of communication process norms but this is something to be expected by politicians and their supporters or by political activists. After all, at least from the perspectives of deliberative and participatory democratic theories, it is among the duties of not just political parties and politicians but also of democratic citizens to broaden public participation in politics (Dalton, 2008). Furthermore, the uses of organic targeting tactics that involve deception and space violation with the aim to confront political opponents head-on, when combined with arguments that challenge the political positions or acts of political opponents in a respectful way, may in effect contribute to democratic deliberation.

2. #Syriza_xeftiles: A case study of political incivility tactics in Greek Twitter

In this paper, we study a case of what Van Spanje and Azrout (2019) have called “indisputable stigmatization” of a political party and its leadership, i.e., the systematic labeling of a political party, its leaders, and supporters with terms that are commonly understood as having extremely negative connotations. In particular, the aim is to analyze and discuss the organic targeting tactics used in Twitter against Syriza, a small radical left party that managed to rapidly gain political support and become the major party in a coalition government in Greece between 2015 and mid-2019.

The study of these tactics is specifically focused on the evolution of the hashtag “Syriza_xeftiles.” In the Greek language “xeftiles” means that someone, the party of Syriza in this case, is morally degraded, has been humiliated, or has no dignity at all. To make sense of why calling Syriza, its leadership, and supporters “morally degraded” (“xeftiles”) became the main slogan in attacks against Syriza in Greek Twitter, we need to contextualize it within the wider moral narratives of the Greek debt crisis of the last decade. During this decade, these moral narratives served in important ways to legitimize an astonishingly wide range of intense acts of political incivility by national and international political elites and the media, and the political publics in Greece and across Europe.

2.1. Moral narratives of the Greek crisis

The phenomenon of social media abuse against political parties and politicians is part of a highly polarized political climate in Greek society. Since 2010 Greece experienced a debt crisis that caused a full-blown recession of unprecedented depth and duration and was subjected to harsh austerity measures and unpopular labor market reforms (e.g., see Perez and Matsaganis, 2018), which in turn caused significant political ruptures and social upheaval (Karyotis and Rüdig, 2018).

The Greek debt crisis, its causes, and remedies were variously narrated in terms of morality. One “morality tale” talked about Greeks who, living imprudently and irresponsibly, being irresponsible in their financial dealings and not respecting the moral obligations that come with loans, now have no choice but to be punished for their sins and take the “bitter medicine” of harsh and unpalatable austerity (Kitromilides, 2013, p. 627; Herzfeld, 2016, p. 11). An associated narrative talked about the political system's moral bankruptcy (Kountouri and Nikolaidou, 2019). Moreira Ramalho's (2020) analysis of over 1,200 public declarations produced from 2009 to 2016 by “Troika” (which represented the creditors' side, comprised of the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund) suggested that the “… framing of the euro crisis presented it as resulting from moral hazard: uncooperative Member States pursued poor economic policies that led to an accumulation of ‘imbalances’. The Troika's discourse further presented both bailouts and ‘punitive’ austerity as inevitable” (Moreira Ramalho, 2020, p. 688). This morality tale, which was adopted also by the traditionally dominant political elites in Greece, “… relied on a series of normalizing dichotomies between good and evil utilizing therapeutic, zoomorphic and pedagogical metaphors (health vs. illness, responsibility vs. irresponsibility, maturity vs. immaturity, humanity vs. animality, normality vs. abnormality)” (Stavrakakis and Galanopoulos, 2019, p. 179).

A counter-narrative talked about the “morality of resistance,” which politicized morality as a moral obligation to collective action to help the most vulnerable and invisible and to attack the symptoms of social decay (Douzinas, 2013, p. 63). The Aganaktismenoi (Indignants) movement, which resisted austerity in the Syntagma Square of Athens, adopted the name of an emotion, which may be interpreted as an ethical response to injustice and evil (outrage) or hatred toward those who have inflicted injustices (indignation) (Douzinas, 2013, p. 160), the Troika and the political and economic elites in Greece in this case. The role of the Aganaktismenoi movement was crucial in transforming the public sphere, undermining the traditional parties, contributing to the emergence of a new divide in Greek society between pro- and anti-bailout citizens, and effectively helping Syriza to win the 2015 elections (Aslanidis and Marantzidis, 2016). Syriza, a party with strong ties with the historic Left in Greece as well as with social movements also capitalized on another powerful moral narrative. As Douzinas has argued, “the Greek Left has a major moral advantage compared with other political forces. It is based partly on its clean past but, more importantly, on its commitment to equality and justice” (Douzinas, 2013, p. 197). Calling Syriza, its leadership and supporters as morally degraded (“xeftiles”) fitted very well into the wider moral narratives of the Greek crisis. It essentially aimed to deconstruct the moral narrative of Syriza.

A completely different narrative of moral advantage was promoted by Golden Dawn (GD), a pro-Nazi, extreme right-wing party (Georgiadou, 2013), which managed to win an unprecedented 6–7% of the vote in the 2012 and 2015 national elections, sending 17–18 of its members to the Greek parliament. Golden Dawn's moral narrative of the crisis targeted, apart from the “corrupted political and economic elites,” the millions of immigrants who “steal jobs” from Greeks, “exploit” the public welfare and health care system, and “commit crimes.” Its morality tale was constructed on GD's version of “community activism” which ranged from paramilitary-style patrols to ensure “crime-free” inner-city neighborhoods and rural areas (Petrou and Kandylis, 2016), to staged open food donations “only to Greek families,” the formation of a Greeks-only “blood bank,” a “Medicines Avec Frontiers” organization and a job seeking service. In the case of GD's “Greeks-only” narrative, which justified its actions to thousands of its voters and supporters, spectacles of extreme political incivility, was a strategic choice that often included violence. The slapping of an MP in a live TV show or televised attacks on migrant merchants at flea markets across Greece were just the tip of the public “presence” of GD. Behind the cameras, GD militias were engaged in systematic violence against immigrants, asylum seekers, and anti-fascists, which also included murders (Koronaiou and Sakellariou, 2013; Ellinas and Lamprianou, 2017)2.

2.2. The Greek political context of the period 2015–2019

After winning the elections in January 2015, the new Syriza-led coalition government under PM Alexis Tsipras followed an aggressive strategy in the bailout negotiations with Greece's official lenders. It was a period of extreme intensification of political incivilities from all sides. The morality tale of lazy Greeks who are refusing to take the “bitter medicine” was further strengthened by the “irresponsible” behavior of PM Tsipras and his coalition government members. According to Bild, Germany's (and Europe's) biggest newspaper, the new Greek government was a “mad coalition” and a “squad” while G. Varoufakis, the new Greek finance minister, was the “Greek money-grubber” and the “Greek liar” (Ervedosa, 2017, p. 149).

After yet another round of failed meetings with the Eurogroup finance ministers, the Greek PM called for a referendum on June 27, 2015. People were called to decide whether Greece was to accept the terms proposed by the so-called “Troika.” A week later, Greeks voted by a landslide “No” (61%), rejecting Troika's conditions. Nevertheless, the Greek PM came into agreement with Troika and called for a new round of elections. On September 2015 Syriza managed to win the snap elections without losing ground. New heatedly debated issues, such as the resurgence of the immigration/refugee crisis (since 2015), the dispute over the name “Macedonia” between Greece and the Former Yugoslavian Republic of Macedonia, and the 2018 wildfires in Attica that caused the death of 102 people, reshaped the field of political and social conflict and sharpened new dividing lines.

In Greece, the extended election cycle between 2015 and 2019, included one referendum, one European Parliament election, and two national elections. Despite the government's successes in getting Greece back on track regarding its finances and in resolving the dispute with the now-called Republic of North Macedonia, Syriza was met with social and political upheaval. Syriza often became the target of outrage and contempt by supporters who felt that it failed to fulfill its pre-election promises, and by political opponents as well as mainstream media which blamed Syriza for gross populism, mishandling of the immigration crisis, and lack of patriotism in the case of the Macedonian issue.

2.3. Research problem and research questions

Previous studies on uncivil behavior against politicians and parties in social media have primarily focused on the frequency of such behavior and the types of political incivility addressed to them. However, there is so far little evidence regarding the organic targeting tactics used to attack the targets of such behavior. Furthermore, while previous research identifies as primary targets of political incivility the Twitter accounts of individual politicians or parties, there is little emphasis on exploring the political and other publics that are directly or indirectly targeted by uncivil tweets addressed at politicians and parties.

#Syriza_xeftiles started sporadically appearing in tweets early in 2015, with the election of Syriza in power, and gradually became the central slogan in thousands of anti-Syriza tweets toward the 2019 national elections. However, no Greek political party or other political actors ever claimed, admitted, or was openly accused of initiating or backing a #Syriza_xeftiles negative campaign on Twitter, and so far no evidence points to this direction. Seemingly, #Syriza_xeftiles was mostly adopted by “anonymous” Twitter users. Some of them posted #Syriza_xeftiles tweets quite frequently. By focusing on these frequent #Syriza_xeftiles twitters during the period when Syriza was in government (Jan. 2015–Jul. 2019) we aim to explore the following research questions:

(a) What were the trends in the evolution, endorsement, and engagement with #Syriza_xeftiles tweets?

(b) To what extent frequent #Syriza_xeftiles twitters combined uncivil and descriptive hashtags in their tweets and what were their target publics on Twitter?

(c) To what extent frequent #Syriza_xeftiles twitters used tags mentioning other Twitter accounts, and what were the types of mentioned accounts and the publics targeted?

(d) To what extent frequent #Syriza_xeftiles twitters targeted other Twitter accounts via replies, and what were the types of accounts and publics targeted?

3. Materials and methods

The dataset of this study has in total 101.512 unique tweets (no re-tweets included) containing the “Syriza_xeftiles” hashtag (in Latin or Greek letters) obtained from the Twitter Search API (Kim et al., 2013). The period covered is from January 26th, 2015, when Syriza formed its first coalition government with its junior partner ANEL, to 1 day before the national elections of July 7th, 2019 when Syriza was defeated by the right-center party of New Democracy (1.623 days in total). Twitter searches on this hashtag and data collection were performed using a custom application. The dataset includes only tweets from Twitter user accounts that have posted at least 30 #Syriza_xeftiles tweets during the period under study.

Among the 867 Twitter accounts in the dataset, six accounts belonged to members of the Greek Parliament and one to a prominent journalist. The public profile of 734 accounts (84.7% of the total) did not provide any information about the identity of the person(s) behind these accounts (anonymous or pseudonymous accounts). The profile of the rest 126 (14.5%) accounts provided personal information that, at least partly, revealed the identity of the users (e.g., account name with an image of the face of a person, biographical information, and/or location and links to their Facebook accounts or to their personal/professional web page). By the end of 2019, in total 137 accounts (15.8%) in the dataset were found to be either non-existent (95 accounts), or suspended for violations of Twitter rules (42 accounts).

It should be noted that between September 2013—when for the first time a #Syriza_xeftiles hashtag was used in a tweet—and January 26, 2015, when Syriza formed its first government, only 36 #Syriza_xeftiles messages were twitted.

To perform analyses on hashtag-based organic targeting tactics, an inductive lexicon-based approach was implemented. From the body of #Syriza_xeftiles tweets were first extracted all extra unique hashtags (case insensitive, diacritics removed from Greek letters). In total, 13.532 unique hashtags were extracted. Among them, 3.248 were purely descriptive hashtags, i.e., they labeled a topic or an issue without including any evaluative term (e.g., #economic_policies but not #bad_economic_policies), were organized in 12 broad categories of topics/issues.

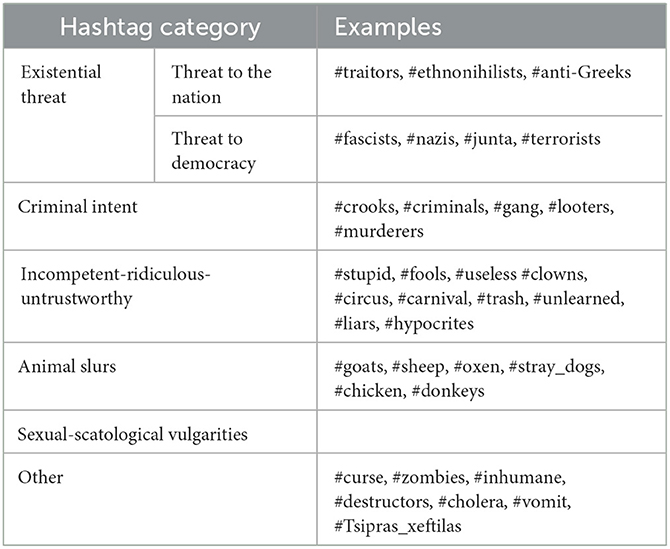

Furthermore, 1.263 unique hashtags with impolite or uncivil language were organized into broad categories (see Table 1).

Based on Muddiman et al. (2021), we first identified groups of hashtags that question the legitimacy of a political party or politician. The “existential threat” category includes two sub-categories of uncivil hashtags that imply that a political out-group represents a serious threat that may endanger the very existence of the nation or democracy in the country. The “criminal intent” category includes hashtags that imply that a political out-group has been or plans to be engaged in some kind of criminal activity. The first two main categories of hashtags essentially question the legitimacy of the political out-group and imply that the political out-group has evil ulterior motives. The “incompetent-ridiculous-untrustworthy” category includes hashtags that imply that the political out-group does not have the intellectual capacity and essential skills to act in a politically responsible, efficient, and effective way. Animal slurs imply that the political out-group has animalistic traits, something that may trigger dehumanization psychological processes of out-group partisans (Moore-Berg et al., 2020b). Finally, sexual-scatological vulgarities of the kind that we have identified in the #Syriza_xeftiles tweets imply that the political game is “a massive dick-waving contest” (Schwanebeck, 2017) in which the political out-group has feminine traits or has a passive homosexual role, and hence it is subject to domination and defeat.

Mentions to users (e.g., @username) appearing in the body of tweets were also extracted to analyze account-based organic targeting tactics (mentions and replies). In total, 4.982 mentioned or replied account usernames were extracted. Among these accounts, 316 accounts belonged to media and journalists/commentators, 149 accounts to the party of Syriza and members of its leadership, and 155 accounts to other Greek political parties and their leadership (12.4% of the total mentioned or replied usernames). In a third step, each of these lexicons was used to implement lexicon-based searches on the body of tweets in the dataset to obtain data on the hashtag- and accounts-based organic targeting tactics presented in the results section.

4. Results

4.1. Evolution, endorsement, and engagement with #Syriza_xeftiles tweets

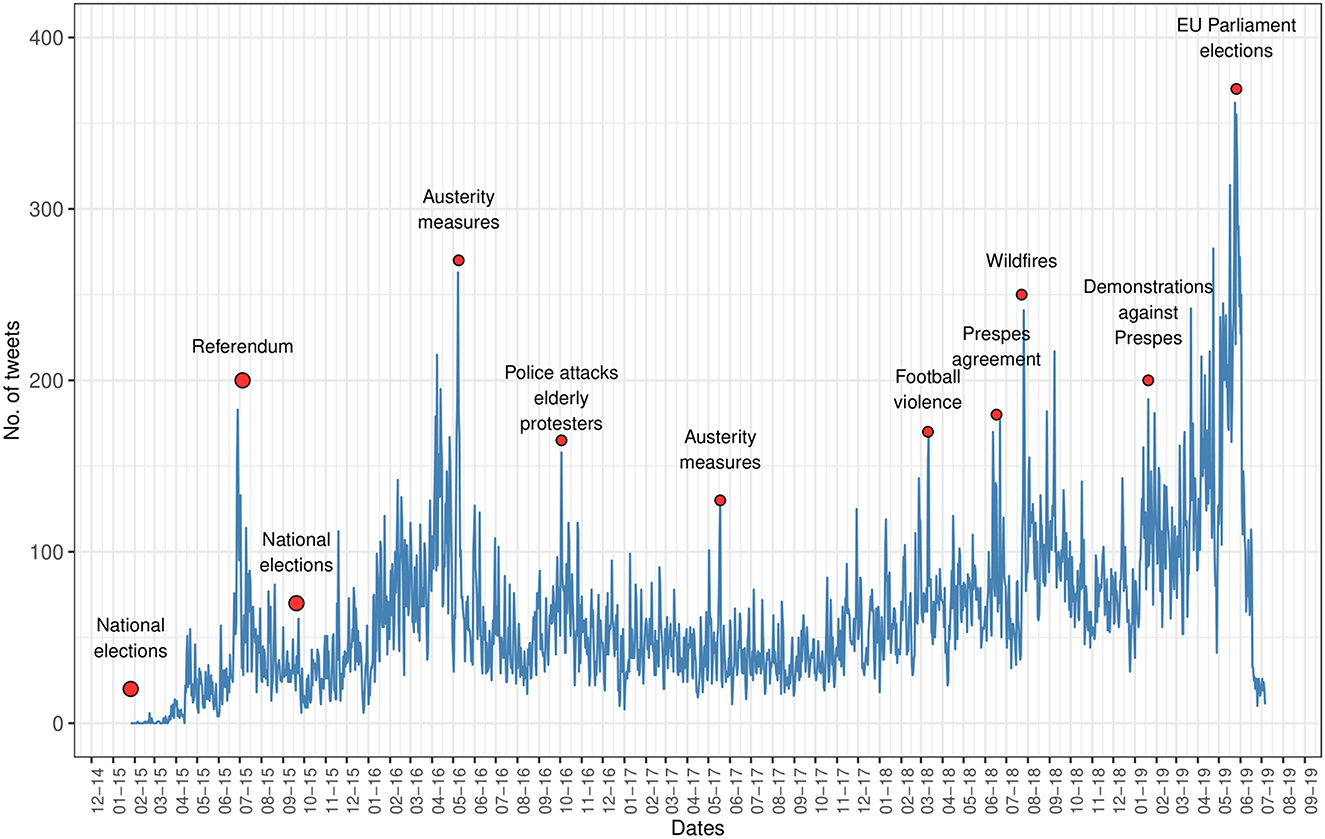

The timeline of #Syriza_xeftiles tweets posted by frequent users of this hashtag during the period when Syriza was in government along with major political or other events that coincided with spikes of #Syriza_xeftiles tweets is presented in Figure 1. The first spike coincides with the referendum on Greece's bailout conditions that took place on July 5, 2015. Practically the referendum with its binary logic crystallized a severe political and societal polarization that emerged after years of harsh austerity measures and labor market reforms that failed to help Greece return to economic development. However, just after the referendum and despite the victory of the side supporting rejection of the creditors' terms, which was backed by Syriza, PM Tsipras chose to strike an agreement with the creditors and eventually call for early elections in September 2019. In the post-referendum period up to the early national elections, there is observed a sharp drop in #Syriza_xeftiles tweets. Perhaps this is an indication of a drop in political polarization because the new Syriza's realpolitik, a dramatic policy reversal over austerity demands made by Greece's creditors which led to a split that led hardliners to leave the party, had helped to calm down the anti-Syriza mood among its political opponents.

After Syriza's victory in the early elections of September 2015, Syriza is gradually now targeted as “xeftiles” because of the introduction of new austerity measures. Up to May 2017, the main spikes of #Syriza_xeftiles tweets coincide with periods when Syriza was negotiating new austerity packages with Greece's creditors, parliamentary processes related to the formal approval of austerity measures, and demonstrations against them. An incident on October 2016 became the focal point of a new #Syriza_xeftiles spike when riot police tear-gassed elderly citizens who protested cuts in pensions. This incident offered an opportunity to attack Syriza as yet another cynical political power that not only failed to keep its promises but also did not hesitate to inflict harm on innocent and powerless citizens.

After May 2017 the attention of #Syriza_xeftiles tweets drifts away from economic policies possibly because GDP growth turned positive. The violence that erupted in a football game became hugely politicized leading to a sharp #Syriza_xeftiles spike, also because the wealthy and powerful owners of the clubs involved had strong ties in the world of politics and the mainstream media.

The July 2018 wildfires that left more than 100 people dead within just a couple of hours offered new opportunities to attack Syriza as incompetent and hence dangerous to the citizens. Within a few days after the wildfires #Syriza_xeftiles tweets sharply spiked, reaching the level of the spike of the first austerity measures introduced by Syriza 2 years earlier. In between, the Prespes Agreement settled Greece's dispute with the now-called Republic of North Macedonia (see Nimetz, 2020), offering new opportunities for political and affective polarization. The mainstream media promoted the narrative that the Prespes Agreement posed an “existential threat” to Greece (Karyotakis, 2022). Most opposition parties fiercely opposed the agreement. It was particularly the center-right party of ND, the major party in the opposition, which, according to Skoulariki (2020), helped to the legitimization of far-right pressure groups and their ultra-nationalistic rhetoric. In 2018 and early 2019, three major #Syriza_xeftiles spikes coincided with events directly related to this agreement. Exploiting popular sentiment, opposition parties offered political support to mass demonstrations organized by grassroots nationalist groups all over Greece. Practically, issues around which could be constructed a wide political consensus (football violence, natural disasters, national issues) became objects of highly polarized political discourse. Opposition parties essentially followed the “popular sentiment” of football fans who felt their club is unfairly treated by the “system,” of shocked and hurt citizens in the aftermath of an unspeakable disaster, of citizens who have been raised with nationalist narratives that exclude any solution to the Macedonian issue that would not deny from the citizens of Greece's northern neighbor their nationalist narratives.

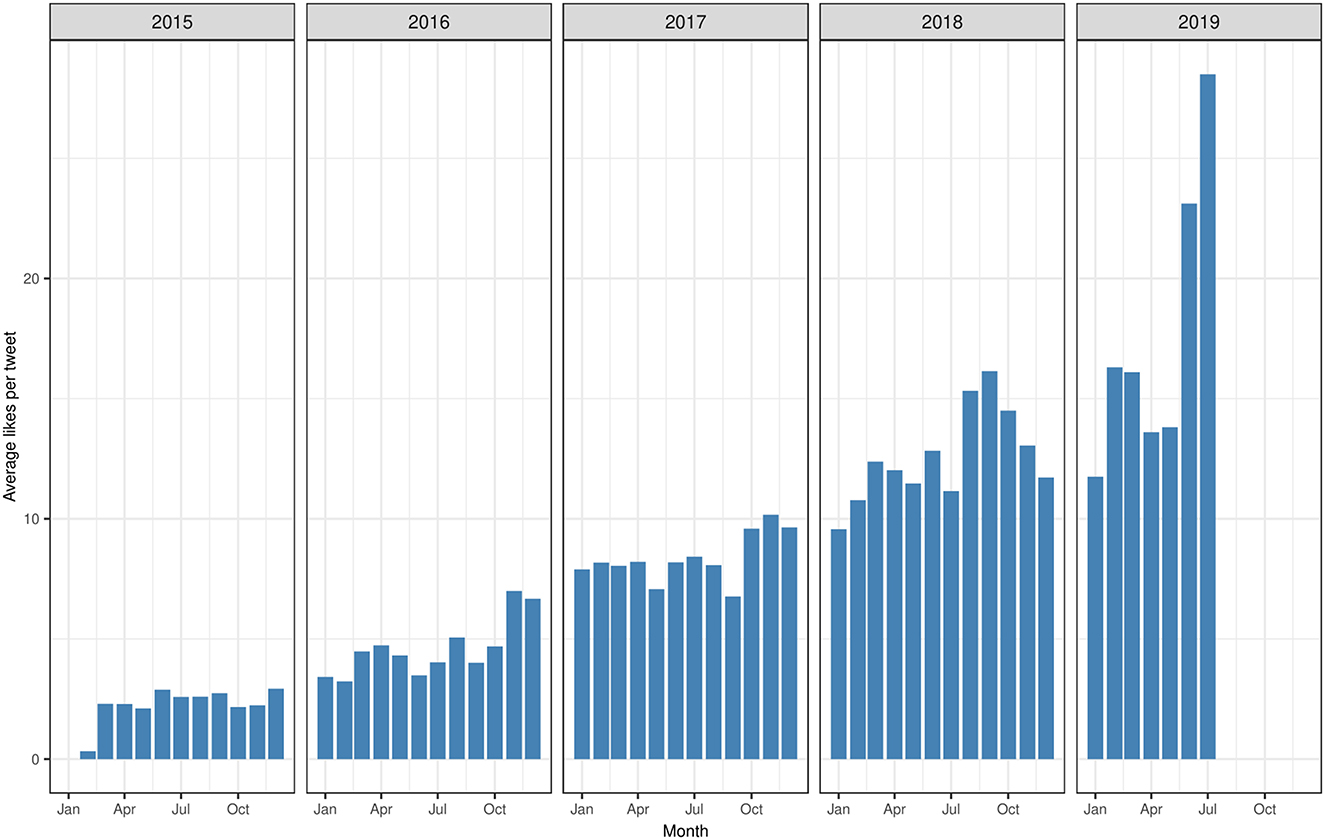

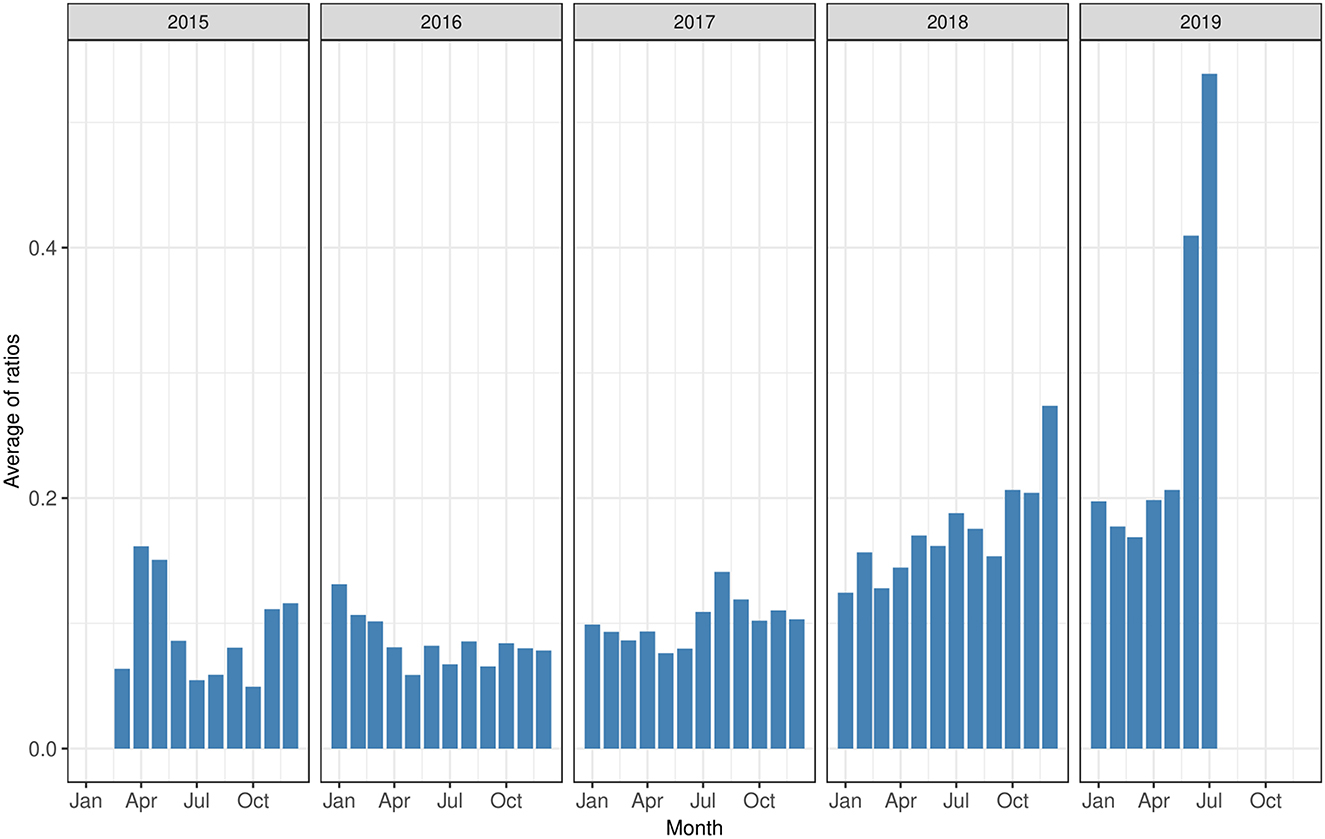

Figure 2 depicts the “likes” that #Syriza_xeftiles tweets received on average per month/year. As it is shown, from month to month and year to year there is a steady increase in the average likes per #Syriza_xeftiles tweet. Characteristically, on average #Syriza_xeftiles tweets received 2.6 likes in 2015, 4.5 in 2016, 8.4 in 2017, 12.9 in 2018, and 14.5 in 2019.

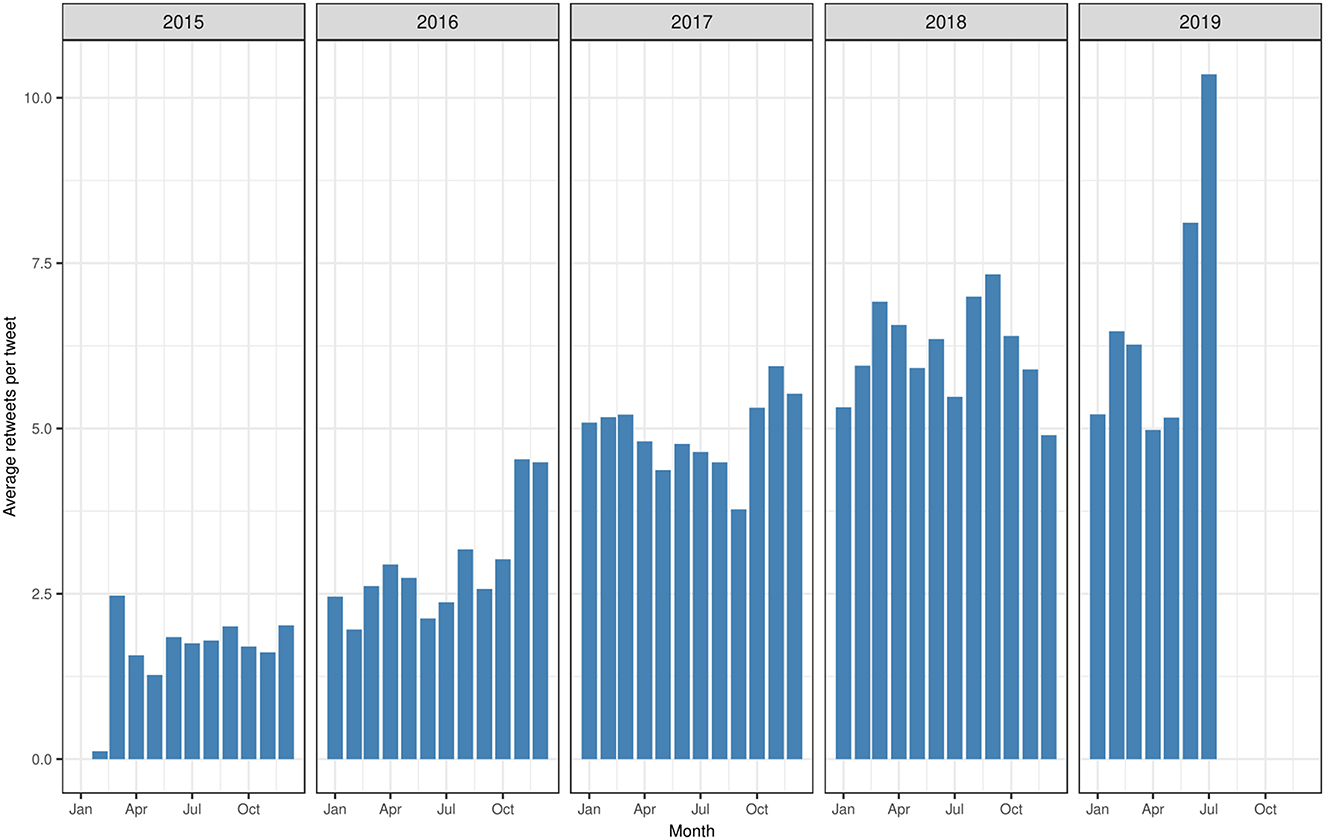

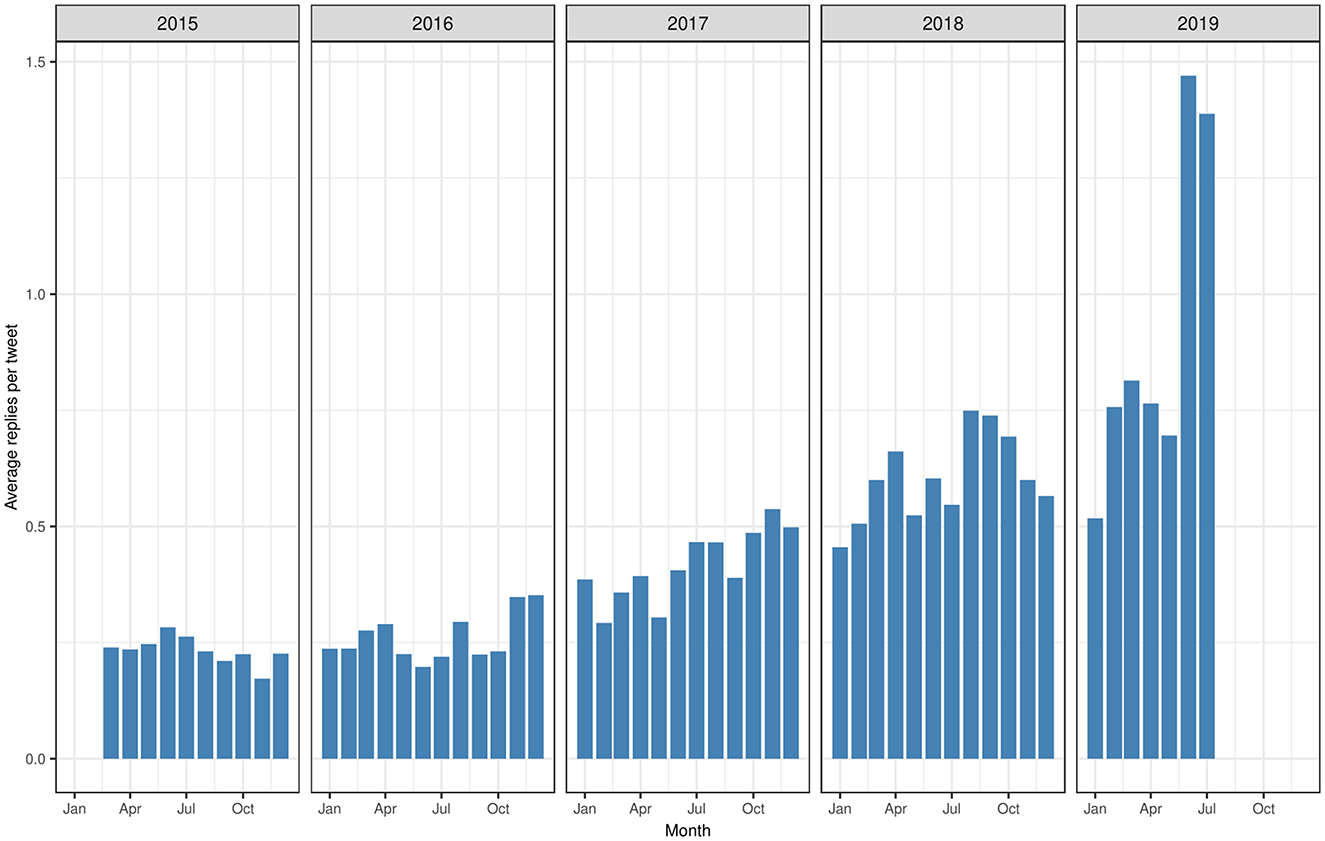

During the period Syriza was in government #Syriza_xeftiles tweets were also more and more re-tweeted (see Figure 3) and received more and more replies (see Figure 4), findings which possibly indicate that #Syriza_xeftiles was normalized within the anti-Syriza political publics in Twitter, i.e., that it became a valid ground for conversations between anti-Syriza twitter users.

One way to develop an understanding of why such a polarizing message managed to become viral on Twitter is to study more closely the targeting tactics of frequent #Syriza_xeftiles twitters. In the following sub-chapters, three different tactics that have been used by frequent #Syriza_xeftiles twitters to spread their message to wider political publics are identified and analyzed.

4.2. Combinations of #Syriza_xeftiles with other hashtags in tweets

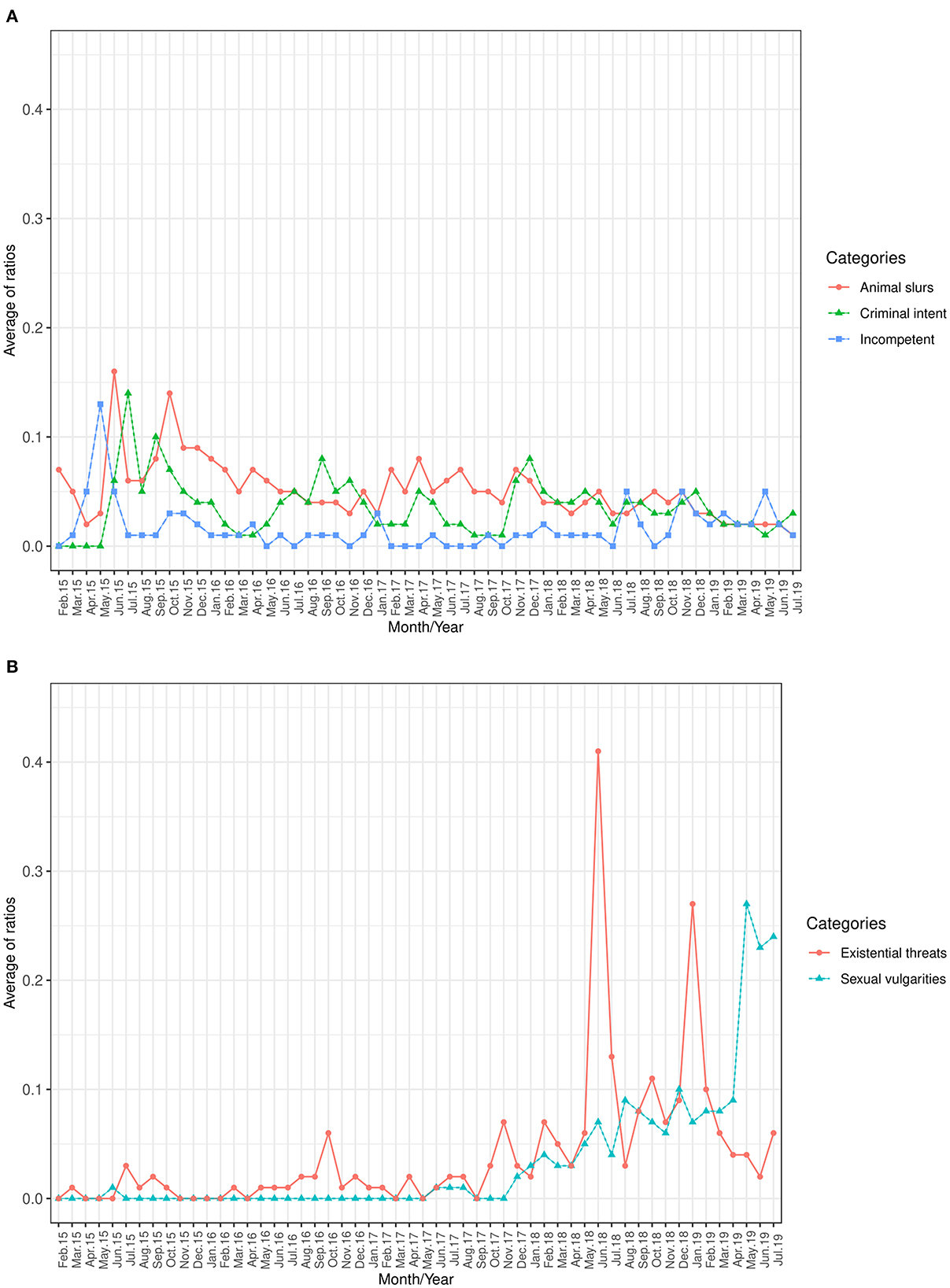

Around 16.4% of the tweets combined #Syriza_xeftiles with at least one extra uncivil hashtag. As shown in Figures 5A, B, between the two national elections of January and September 2015, #Syriza_xeftiles was more often combined with uncivil hashtags implying that Syriza was incompetent, had criminal intents, and animal-like traits. Overall, the dominant line of uncivil attacks was focusing on the “moral degradation” of Syriza as being justified based on traits which implied that Syriza and its government was a gang consisting of incompetent, ridiculous, or untrustworthy politicians, and followed by supporters who blindly (like “goats” or “sheep,” mostly) believed in Syriza leadership's populist propaganda. During this first phase of #Syriza_xeftiles tweets the extra uncivil hashtags in the body of tweets tended to express personal-level attacks on Syriza, its leadership, and its supporters.

Figure 5. Monthly average of ratios between uncivil hashtag categories and total tweets. (A) Criminal Intent, incompetence, and animal slurs. (B) Existential threats and sexual-scatological vulgarities.

However, gradually #Syriza_xeftiles was combined with a different kind of uncivil hashtags which had to do not so much with personal attacks but with attacks on Syriza policies. In other words, the uncivil attacks became political and pointed to the existential threat that these represent to the nation and democracy in Greece. The peaks of these attacks coincided with the government's efforts toward and after the Prespes Agreement. Sexual and scatological vulgarities peaked toward the pre-election period of 2019, stressing that Syriza, which has feminine traits or a passive homosexual role, is unavoidably subject to domination and defeat in the upcoming elections.

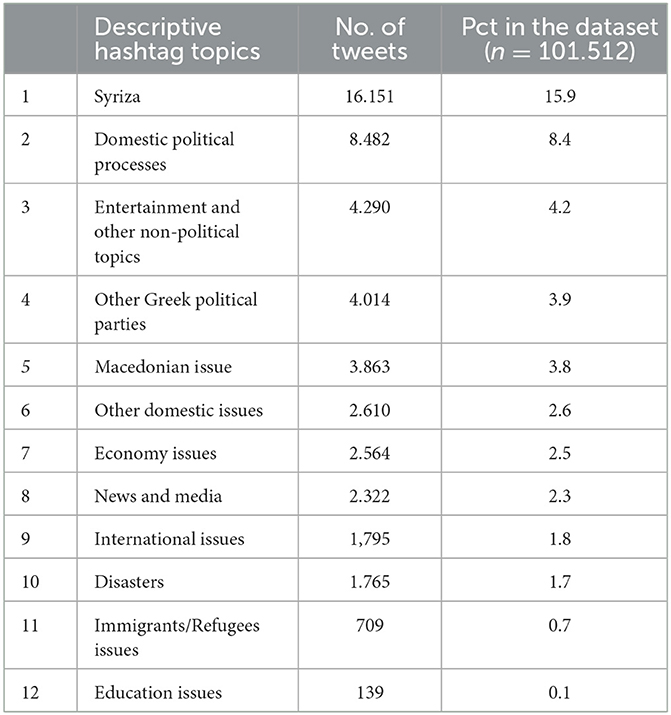

While the study of combinations of uncivil hashtags may reveal the underlying narratives of uncivil attacks and how these may change over time, the study of combinations of uncivil hashtags with descriptive ones may reveal the types of publics targeted by these attacks. Among the 101.512 #Syriza_xeftiles tweets in the dataset, 34.525 (34%) included at least one descriptive hashtag (e.g., #AthensFilmFestival). This is an indication that the use of the tactic of combining #Syriza_xeftiles with descriptive hashtags was quite extensive. Almost 65% of the accounts adopted this tactic in at least 20% of their tweets. Of particular interest is the use of #Syriza_xeftiles in combination with descriptive hashtags naming:

a) political parties and political processes, such as elections and parliamentary debates, effectively aiming to disseminate #Syriza_xeftiles messages to publics that are especially interested in politics,

b) media and news outlets to target those who are following those hashtags to get news, and

c) non-political interest topics to target the varied, random, and wide publics in Greek Twitter.

The list of the most popular descriptive hashtag groups with which #Syriza_xeftiles was combined in the body of tweets is presented in Table 2. Almost 16% of all tweets combined #Syriza_xeftiles with at least one descriptive hashtag naming Syriza, its leadership, or partisan media supporting Syriza. Essentially, this tactic points to a deliberate effort to penetrate the information and conversation space of Syriza on Twitter. The second target of this tactic was users interested in political processes, such as parliamentary discussions and electoral processes (8.4%). The publics around other parties were of much less interest as targets of #Syriza_xeftiles tweets (3.9%). Based on these findings it can be assumed that comparatively much more emphasis was placed to demobilize Syriza sympathizers and destabilize the ad-hoc publics close to Syriza, and strengthening the anti-Syriza sentiment among publics interested in politics in general. This ordering in the choice of targets seems quite reasonable given the high degree of party animosity and polarization which ensured that publics close to other parties were already strongly against Syriza.

According to the 2019 Reuters Institute report, 67% of people in Greece who are online use social media to get news (Newman et al., 2019, p. 88). The tagging of names of media and news shows in #Syriza_xeftiles tweets (2.3%) is indicative of an intention to target this varied and massive media audience that uses Twitter to get news. What is, however, a very clear indication of the intentions of targeting tactics aimed at massive audiences is the effort to expose to #Syriza_xeftiles tweets those users who were following and/or talking about a wide range of non-political topics on Twitter, from the Oscars nominations to popular reality shows and religious celebrations (4.2%). Essentially this finding is indicative of a high degree of cynicism and ruthlessness on behalf of at least some of the frequent #Syriza_xeftiles twitters. The issue that was comparatively given more attention in descriptive hashtags was the Macedonian issue which was settled in June 2018 between Greece and the now-called Republic of North Macedonia with the Prespes Agreement, despite fierce opposition by most political parties in Greece and a series of massive demonstrations.

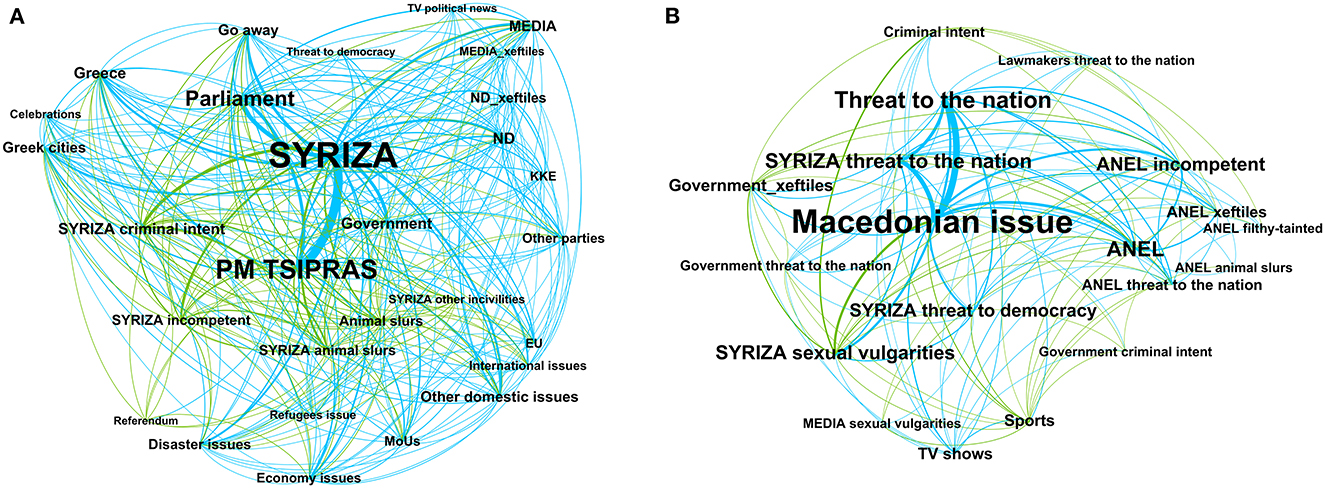

To further explore how descriptive and uncivil hashtags were combined with #Syriza_xeftiles, a semantic network analysis was performed on pairs of hashtag category co-occurrences in the body of tweets. From the analysis, it was filtered the #Syriza_xeftiles hashtag because it was always present. The rest of the most popular hashtag category co-occurrences were analyzed with the Louvain modularity clustering algorithm (Blondel et al., 2008) of Gephi software, using as weight the frequency of their co-occurrence. This algorithm partitioned the network of co-occurring hashtag categories into two main communities of densely connected hashtag categories.

The first, and denser, community of co-occurring hashtag categories is reflecting the targeting tactics of #Syriza_xeftiles tweets aiming predominantly to attack the Syriza publics and PM Tsipras (see Figure 6A). #Syriza_xeftiles tweets are combined with animal slur hashtags (e.g., “goats,” “sheep”), hashtags implying that Syriza and its leadership is incompetent, ridiculous, or untrustworthy (e.g., “stupid,” “liars”), has criminal intentions (“crooks, “gang”), and hashtags that imply a threat to democracy in Greece (“fascists,” “junta”).

Figure 6. Communities of often co-occurring hashtag categories. (A) The Syriza and PM Tsipras community of hashtag categories. (B) The Macedonian issue community of hashtag categories.

In this hashtag community, #Syriza_xeftiles is combined with descriptive hashtags referring to the handling of the economic crisis and the negotiations with Troika (e.g., Memorandum of Understandings—MoUs, and the 2015 referendum), to the immigration/refugees issue (primarily to the full-blown crisis in the summer of 2015 when an estimated 1 million refugees from Syria and elsewhere crossed Greece's borders), to the July 2018 wildfires that left more than 100 people dead, and other domestic and international issues. These issue-based hashtag categories often co-occur with descriptive hashtags naming media, TV political shows, various national or religious celebrations, and a large number of Greek cities. This is an indication of efforts to deliberately make anti-Syriza tweets visible to wide media audiences and non-political local mini-publics on Twitter. Furthermore, the use of descriptive hashtags naming other political parties (e.g., ND, KKE) is indicative of a deliberate effort to also target other partisan publics. What is interesting to note is that occasionally the targeting of other partisan publics is also combined with hashtags that attack these parties (e.g., “ND xeftiles”).

The second hashtags community of #Syriza_xeftiles tweets (see Figure 6B) is focusing on the Macedonian issue and the Prespes Agreement that PM Tsipras signed with PM Zaev, settling the dispute over the official name of Greece's northern neighbor now called Republic of North Macedonia. The cloud of co-occurring hashtags on this issue includes hashtags that stigmatize Syriza and its leadership as a threat to the nation (e.g., “traitors”) or to democracy (e.g., “fascists”) (apart from “xeftiles”). “Traitors” because they “sold” the name of Macedonia which should belong only to the Greeks and “fascists” because they did not listen to the popular demand not to make any compromises over this national issue. The co-occurrence of descriptive and uncivil hashtags naming ANEL, the junior coalition party in the government, as well as lawmakers in the Greek Parliament is also an indication of attempts to stigmatize those MPs who chose to vote in favor of the Prespes Agreement in the Parliament to the targeted Macedonian issue-based public but also well-beyond it. Overall, this hashtag community represents not just a sum of often co-occurring uncivil hashtags but an uncivil political narrative framing the Macedonian issue, full of dragons but no fairies. The #Syriza_xeftiles tweets on the Macedonian issue also combined descriptive hashtags on popular non-political TV shows and sports topics. This tactic is pointing to a deliberate effort to disseminate these messages and their underlying political narrative to wide political and non-political publics.

4.3. The use of mentions in #Syriza_xeftiles tweets

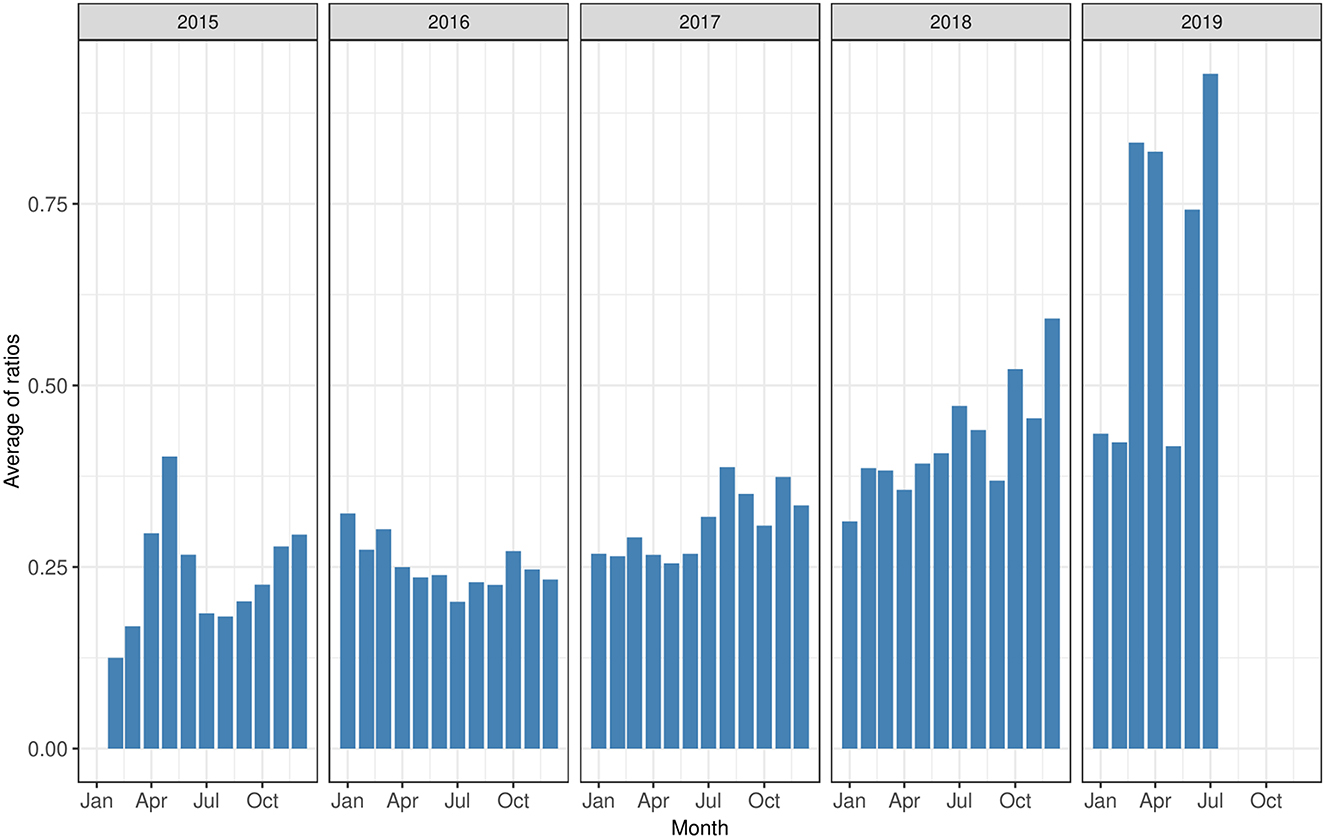

In our dataset, 37.976 mentions in #Syriza_xeftiles tweets were made to 4.982 unique accounts. Figure 7 shows that mentions of other Twitter accounts in #Syriza_xeftiles tweets proportionally increased over the years. It is observed a sharp rise between early 2018 and the months before the European parliament election and the regional/municipal elections of May 2019, when Syriza suffered heavy defeats, leading PM Tsipras to announce early general elections. This finding indicates that #Syriza_xeftiles twitters, or at least many of them, gradually learned how to weaponize the @mention feature of Twitter to target more and more accounts of interest to them.

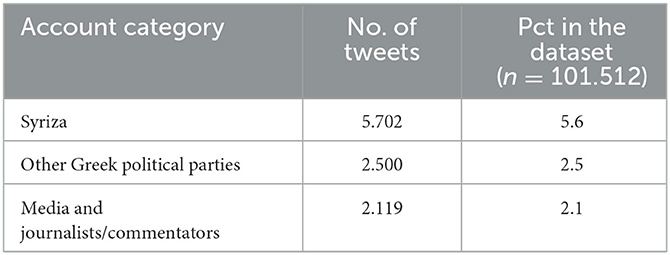

Of particular interest is the use of mentions to Twitter usernames belonging to (a) Greek political parties and politicians, (b) the Greek government and public services, and (c) media and journalists/analysts. Micro-targets of mentions became predominantly the accounts of the political and media elite in Greece (see Table 3). By targeting these accounts, the #Syriza_xeftiles tweets aimed to indirectly reach a vast number of their followers and all those interested in their activities. Almost half of the mentions (49.8%) in #Syriza_xeftiles tweets were made to just 100 accounts. This is indicative of very selective targeting of specific accounts. Among these, 58.5% were accounts of the Syriza government members and party leaders or from a small list of media accounts openly supporting Syriza. Mostly the target was PM Tsipras and the official account of Syriza (26.1% of all mentions in #Syriza_xeftiles tweets among the top 100 mentioned accounts).

In total 9.2% of the #Syriza_xeftiles tweets included at least one mention to accounts of the political and media elite in Greece. This organic targeting tactic was used at least once by 688 (79.3%) of the users in our dataset, and 98 of them (11.3%) used this tactic in at least 20% of their #Syriza_xeftiles tweets.

4.4. The use of replies in #Syriza_xeftiles tweets

In our dataset, 13.927 #Syriza_xeftiles tweets (13.7% of the total) were replies to conversations initiated by other accounts (2.133 unique accounts in total). In Figure 8 it is shown that #Syriza_xeftiles replies to Twitter conversations proportionally increased over the years. As with the case of mentions, this finding is likely to indicate that #Syriza_xeftiles twitters gradually learned how to weaponize the reply feature of Twitter to target more and more accounts of interest to them.

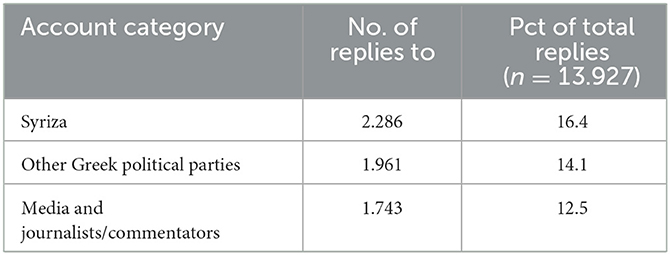

More than half of the users (51.4%) posted at least one reply in conversations initiated by political and media elite accounts. Among the #Syriza_xeftiles tweets that replied in such conversations, 2.286 (16.4% of the total replies) replied in conversations initiated by members of the Syriza government, by Syriza party leaders, and by Syriza-friendly media (see Table 4). This finding is indicative of a predominant intention (also identified in the case of hashtags and mentions), to expose Twitter publics close to Syriza to counter-messages that stigmatize their party and to disrupt conversations taking place within these publics.

Table 4. Frequencies and percentages of replies to target Twitter accounts by target account category.

Furthermore, another 14.1% #Syriza_xeftiles replies were posted in conversations initiated by officials and prominent members of opposition political parties, and 12.5% in conversations initiated by mainstream media and journalists. In total, 43% of the #Syriza_xeftiles replies were aimed at conversations initiated by high-profile political accounts on Twitter, most likely to reach wide audiences interested in news and to target specific political publics. It is also characteristic that just 99 accounts posted almost 74% of all #Syriza_xeftiles reply tweets. A small “army” of 99 accounts appears to have adopted the tactic to push as hard as it could the #Syriza_xeftiles message using as vehicle conversations initiated by other accounts, preferably accounts with a high-level political profile.

5. Discussion

This paper aimed to address through empirical research the gap in the literature on the study of organic targeting tactics of uncivil behavior on Twitter against politicians and political parties and the publics that are directly or indirectly targeted by these tactics.

The findings regarding the hashtag-based targeting tactics show that around 66% of the #Syriza_xeftiles tweets did not make use of any additional descriptive hashtags referring to political or non-political topics. This finding indicates that the aim of the use of hashtag-based organic targeting tactics was primarily to establish a special kind of ad-hoc anti-Syriza public on Twitter. In the early days of #Syriza_xeftiles tweets, this hashtag expressed a call to form an imagined community preater-hoc (Bruns and 2011, p. 7), in anticipation of the formation of an ad-hoc public of “morally outranged” anti-Syriza users. Initially, this hashtag was conversational rather than organizational (Huang et al., 2010) given that #Syriza_xeftiles tweets were very infrequent. These early #Syriza_xeftiles twitters were not just interested to use impolite language to express their moral outrage against Syriza and to make it known to the circle of their followers or in the context of a specific Twitter conversation. The choice of adding the #Syriza_xeftiles hashtag and its stigmatizing message into the body of their tweets also expressed their intent to inspire and prompt other users to use it. As #Syriza_xeftiles became more popular, this hashtag was also communing affiliation (Zappavigna and Martin, 2018). Engagement with this hashtag meant that users were participating in morally outraged conversations on Twitter which shared the understanding that Syriza is indeed morally degraded or at least expected to be exposed to content that provided arguments and evidence of the immoral behavior of Syriza and its leadership, in combination with other uncivil attacks that questioned its legitimacy, its motives, and its skills. In other words, the aspiration was to co-create a political public where users will feel free and safe to use even extremely impolite language when criticizing a political out-group (Lee et al., 2019). This is bad enough but, after all, it is something that takes place between condescending individuals. Liberal democracies, no matter how flawed they may be, as in the case of Greece, are not threatened by how like-minded people talk about politics with each other in online (and offline) public spaces.

However, a sizable chuck of tweets was also targeting other political and non-political publics. Our findings show that more than one-third of #Syriza_xeftiles tweets were combined with at least one additional descriptive hashtag. Furthermore, mentions of other Twitter accounts in #Syriza_xeftiles tweets proportionally increased over the years and a similar trend was observed in the case of the reply targeting tactic. The use of these two account-based targeting tactics sharply increased just prior to the European parliament election and the regional/municipal elections of May 2019. Evidence presented in this paper indicates that Twitter users gradually learned how to weaponize the hashtag, reply, and mention features of Twitter to target more and more regularly a variety of publics and audiences on Greek Twitter with uncivil political narratives. The primary targets were the politicians and publics close to Syriza, and, to a lesser degree, politicians and publics close to other political parties, non-political publics, and issue-based publics. The weaponization of hashtag, reply, and mention features of Twitter often involved the combination of several political incivility dimensions, as these were identified by Stryker et al. (2016, 2022), namely the dimension of the use of insulting utterances (utterance incivility), the use of deception through hashjacking (Bode et al., 2015; Darius and Stephany, 2019, 2022) and the discursive dimension (discursive incivility), which in effect constituted space violations, interruptions, and discussion prevention.

Our findings indicate that in the case of mentions, it was adopted a very selective targeting approach, as almost half of the mentions in #Syriza_xeftiles tweets were made to just 100 Twitter accounts. Most of them were accounts of the Syriza government and party leaders or news media accounts openly supporting Syriza. Furthermore, more than 16% of the total #Syriza_xeftiles replies to other users were posted in conversations initiated by Syriza-affiliated accounts. These findings indicate the motivation to confront Syriza publics head-on with insulting language within their own public spaces on Twitter. By intentionally getting in the opponent's face, the use of insults such as calling Syriza, its leadership or supporters as #stupid, #fools, or #chicken was not merely impolite but politically uncivil. This is because such targeting practices violate the norm related to the expectation in liberal democracies that the organization and conduct of democratic political processes are free from outside manipulation or disruption and therefore parties, politicians, and their supporters can engage in public partisan political activities without being exposed to intimidation and disruptions from people who hold different political views. The uncivil use of organic tactics to attack political parties and politicians by tagging their names and replying to their conversations can also have far wider implications on affective polarization and ultimately on democratic processes. One reason is that members of the publics of the targeted parties and politicians may develop the perception that literary everyone who happens to share common political views with Twitter users who use such tactics holds demeaning views about their in-group. Meta-perceptions, i.e., how we think the out-group perceives our in-group, may become extremely exaggerated when the timelines and conversations of the politicians and parties are flooded by uncivil messages mostly from anonymous out-group trolls and individuals who hold extreme views. Such meta-perceptions may play an important role in driving affective polarization (Moore-Berg et al., 2020a), especially when they encourage in-group members who are conflict-approaching (Sydnor, 2019b) to seek retaliation and choose to confront their opponent head-on using the same uncivil targeting tactics.

The violation of the expectation in liberal democracies that the organization and conduct of democratic political processes are free from outside manipulation or disruption can have grave consequences for democratic processes not only at the broader level of party competition but also on the level of political participation and engagement of individual citizens and politicians in social media. Prior studies suggest that the manipulation of targeting tactics (tagging and reply features) to attack politicians may affect primarily women politicians (e.g., Ward and McLoughlin, 2020), and especially multiply-marginalized women politicians (Kuperberg, 2021). These findings suggest that uncivil targeting tactics make it much more challenging for women politicians to engage in online political activities as compared to men. Furthermore, anecdotal as well as systematic evidence suggests that some politicians choose to close down their social media accounts as a result of abuse, limit their presence in social media by self-censoring themselves, and by avoiding interacting with other users, or even choose to stand down as MPs (e.g., see Gorrell et al., 2020; Ward and McLoughlin, 2020; Erikson et al., 2021).