95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 16 May 2023

Sec. Dynamics of Migration and (Im)Mobility

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1100446

This article is part of the Research Topic Migration and Integration: Tackling Policy Challenges, Opportunities and Solutions View all 13 articles

Syrian nationals are not only the largest refugee group in Germany but also the third largest group of foreigners living in Germany. The naturalization trend among this group has been very pronounced in the last two years and is expected to increase sharply in the coming years. However, little is known about their political interest in German politics.1 Given the importance of “political interest” as an indicator of social integration and future active citizenship, this paper examines the extent to which Syrian refugees are interested in German politics and how local conditions at the time of arrival influence refugees' interest in German politics. We focus on three dimensions of the neighborhood context theory (social networks, economic situation, and political environment) in combination with traditional political participation theory. The empirical strategy relies on the exogenous allocation of refugees across federal states, which can be used to identify the effect of local characteristics on refugees' political interest. We use in our analysis a nationally representative sample in Germany (IAB-BAMF-SOEP-Refugee-Sample). Our findings suggest that ethnic social networks play a significant role in boosting newly arrived refugees' interest in German politics. Moreover, a higher unemployment rate among the foreign population is associated with an increase in political interest among Syrian refugees. We also confirm that a high political interest among the native population in Germany leads to a higher political interest among Syrian refugees. These results show that more attention needs to be paid to the integration of Syrian refugees and underline the need to reassess the efficiency of the distribution policy for Syrian refugees.

“Wir schaffen das”

Phoenix, 2015 (previous German chancellor)2

“Ja, wir haben es geschafft, wir sind angekommen”

Deutsche, 2021 (first Syrian refugee candidate for the Bundestag elections 2021)3

Following the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in 2011 and the brutal civil war that followed, a large part of the Syrian population was forced to flee the country. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, there are currently more than 6.8 million Syrian refugees and asylum seekers in Syria's neighboring countries, Europe, and more than 100 other countries around the world. Germany has emerged as a major European destination for Syrian refugees. Between 2015 and 2016, more than 430,000 Syrian refugees applied for asylum in Germany, representing 30% of all asylum applications (BAMF, 2017) (see Appendix Figure 2A). Syrian nationals are not only the largest group of refugees but also the third largest group of foreigners living in Germany. The trend toward naturalization of this group has been very clear in the last 2 years (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2022) (see Appendix Figure 1A) and is expected to increase sharply in the coming years. As potential voters, Syrian refugees will gain political weight in the future and are undoubtedly a relevant group to be considered by German policymakers. However, little is known about their political interest in German politics and what determines this interest. Therefore, we explore the following questions:

– To what extent are Syrian refugees interested in (German) politics?

– What determines the political interest of Syrian refugees in Germany?

Low political interest is one of the consistent findings in surveys of immigrants in Germany (Diehl and Blohm, 2001). Nonetheless, several reasons support the need to study and promote the political interest of immigrants. Political engagement enables immigrants, in particular refugees, to defend their interests and rights in their new society against the rise of radical right-wing and anti-immigrant parties. Thus, increased political interest or participation by immigrants may promote public policies that conflict less with immigrants' preferences (Vernby, 2013). A greater level of political engagement can promote the social integration of immigrants in general and enable a successful adaptation to the host society.

Determinants influencing immigrants' political interest or/and participation have been studied from various perspectives. Recent studies suggest that standard predictors such as socioeconomic status can only predict immigrants' political participation to a certain extent (Rooij, 2012; Wass et al., 2015). The experiences of immigrants prior to their arrival, such as their cultural background and previous exposure to democracy, have been highlighted in other works as key factors influencing the level of political engagement in the host society (Dancygier, 2013; Strijbis, 2014; Voicu and Comşa, 2014; Wass et al., 2015; Ruedin, 2017; Rapp, 2018). Moving beyond the individual level, some studies highlight the role that local governments, immigrant associations, and advocates can play in promoting the political integration of immigrants in the cities where they live (Koopmans, 2004; Bloemraad, 2005; Bloemraad and Schönwälder, 2013; de Graauw and Vermeulen, 2016). Beyond the role of individual socioeconomic characteristics, in this study we focus on the impact of local characteristics of initial reception districts on interest in German politics. Our work is inspired by recent studies on this topic by Bratsberg et al. (2021) and Lindgren et al. (2022), who investigated the local neighborhood theory in the Swedish and Norwegian context. We contribute to the literature by analyzing the impact of local characteristics in the German context based on the three dimensions of ethnic social networks, economic situation, and political environment in addition to socioeconomic factors. Other than adding to the debate on the neighborhood context theory by transferring it to the German context, our contribution is also important from a policy perspective. Our findings on the group of Syrian refugees are to some extent also applicable to other groups of refugees in Germany as the local characteristics apply to all refugees. In our calculations, we also accounted for other refugee groups (see Appendix Table 4A). However, looking at other refugee groups in more detail may lead to small variations as differences between the groups do exist. Further studies would be needed in order to find out how other refugee groups are affected by the same local characteristics.

This paper consists of seven sections. Section two illustrates the institutional background and Section three provides an overview of the theory of political interest and participation. In Section four we describe our research design and thereafter, show the results in Section five. We discuss the results and summarize these in Sections six, seven.

Most Syrians were never exposed to democracy in Syria (Marshall, 2014). Since its independence in 1946, Syrians have mostly been living under military authorities and/or ‘civil' dictatorships characterized by high levels of political repression (Lange, 2013). After independence, Syria experienced its only democracy in modern history. The period between 1946 and 1956 witnessed several attempts to establish a democratic system (Lange, 2013). Despite the richness of experience, Syria had twenty different cabinets and drafted four separate constitutions, which destabilized the democratic system. Syria's union with Nasserist Egypt in 1958–1961 brought an end to the brief democratic interval before the 1963 Ba'th coup, which has been controlling the state by totalitarian-style governments that exercise social, economic, and political repression as well as an extremely high degree of control over everyday life (Maktabi, 2010; Musawah, 2020; Yonker and Solomon, 2021). These practices have remained even after Bashar Al-Asaad took over as president when his father and former president of Syria Hafis Al-Assad died in 2000 (Lange, 2013). With Basher Al-Assad in power, a new era was promised. The establishment of political parties was allowed and the restrictions on civil organizations were limited to some extent (Moubayed, 2008). Economic liberalization and political pluralism have served Asaad's regime and his family (Daher, 2018). All political parties in Syria are (in)directly part of the Asaad system. They work under the supervision of the intelligence service and obey its orders, i.e., the role model, officially or unofficially, directly or indirectly, is the Baath Party. Political participation can only happen under strict government control and should serve the established regime (International Crisis Group, 2004; Human Rights Watch, 2010).

Nonetheless, this period has also witnessed a couple of attempts to change the status quo in order to obtain more freedom of choice and be able to participate in political decision-making (Carnegie Middle East Center, 2012).4 All peaceful movements have been suppressed. Abroad, Syrians in exile have been playing an essential role in the Syrian political game against the established regime for a long time. The USA and Europe have hosted political Syrian refugees, who have tried to participate at the national and international levels to influence public opinion toward the Syrian political situation. Their efforts, however, remain limited.

The Arab Spring, which began in Tunisia and was followed by Egypt and Libya in March 2011, has brought the biggest change for the country and has broken the stagnant political situation in Syria (Żuber and Moussa, 2018). Hundreds of demonstrations and protests have been organized (Yacoubian, 2019), and thousands of people have participated in this uprising, particularly young males (Ahmed, 2014). March 2011 marked the start of the civil war in Syria. It started with peaceful student protests against the Syrian government and was met with a massive crackdown by the government (Reid, 2022). Further protests and government crackdowns followed, militant groups formed and the pro-democracy protests expanded into a civil war in 2012 (Reid, 2022). This has led to about 13 million Syrians being forcibly displaced, more than half of the country's population. Of these 13 million Syrians around 6.8 million are refugees and asylum-seekers who have fled the country. The rest, around 6.9 million people, are displaced within Syria (Reid, 2022).

Our expectations of the interest in politics among Syrian refugees in Germany are based on the above-mentioned history and forced migration background. On the one hand, one can expect a lack of interest in politics, since life in Syria has been a source of suffering persecution, deportation or execution. Therefore, it can be assumed that Syrian refugees keep intentionally away from any political participation or involvement in order to protect themselves. On the other hand, Syrians, who participated in the revolution and were politically active under these life- threatening situations, may see the democratic system in Germany as an opportunity to continue their activism or redirect their interest into politics.5

Hosting over 1 million refugees in 2022, Germany is the fifth largest host country worldwide (UNHCR, 2021). Over half of these 1 million refugees in Germany, particularly 560,000 of them, are Syrians (UNHCR, 2021). Together with other non-citizens, this group of refugees, makes up 13.1% of foreigners in Germany in 2020 (Statista, 2022a). The group of people with a migration background comprises almost 30% of the German population (Statista, 2022b), which highlights the need for all-encompassing migration policies.

According to the Migration Integration Policy Index 2020, which compares 56 countries worldwide, it can be said that Germany fares rather well in their integration and migration policies when compared to other countries (MIPEX, 2020b). However, when comparing Germany to other Nordic countries or neighboring countries, Germany's policies are less comprehensive (MIPEX, 2020b). With a MIPEX score of 58/100 Germany lost its place in the international top ten because Germany lacks behind in providing non-EU immigrants with equal basic rights and with a secure future (MIPEX, 2020a). The MIPEX report underlines that Germany's approach “encourages the public to see immigrants as their neighbors, but also as foreigners and not as the equals of native German citizens” (MIPEX, 2020a).

In the following a short overview of possible political participation forms is outlined.

First, German law does not allow refugees or other non-European residents, who do not have a German citizenship, to participate in elections or to vote (Bekaj et al., 2018, p. 35). As a result, a large section of the immigrant population, including Syrian refugees, is left disenfranchised. Party membership, however, is permitted even without voting rights Most parties represented in the German Parliament (Bundestag) allow membership to non-EU-citizens based on residency permits in Germany (CDU et al., 2018; FDP, 2019; BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNE, 2021; DIE LINKE, 2021; Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, 2021): Joining the Christian Democratic Union of Germany is only possible via a guest member and is restricted to people, who have lived in Germany for at least 3 years (Tagesspiegel, 2017). Furthermore, non-German nationals are allowed to register a party if the majority of its members or the members of the board are German citizens as outlined in the law on political parties [Parteigesetz, para. 2 (3)], Otherwise, they are only permitted to organize in the form of political associations, and hence are prevented from participating in elections.

Given the lack of opportunities for traditional forms of democratic participation, foreign advisory and migration and integration councils (Ausländer-, Migrations-, and Integrationsbeiräte) have been established in various German cities and municipalities since the mid-1970s to ensure political representation of migrants at the local level (Gesemann and Roth, 2014). Regulation of the formation of these consultative bodies is governed by different constitutions of the German federal states (Hanewinkel and Oltmer, 2017). Often, integration councils tend to have an advisory function, and therefore can only advocate for the interests of the immigrant population, but do not make binding decisions (Hanewinkel and Oltmer, 2017). Furthermore, it has been highlighted that next to the lack of decision-making power, the scarce financial resources of many integration councils limit their capacity to exert influence at the communal level (Hunger and Candan, 2009). The low turnout at many council elections, which amounts to ten per cent, poses another challenge to the legitimacy of migrant representative bodies (Vicente, 2011).

Next to state-led initiatives, there are several civil society organizations, trade unions, and political foundations in which asylum seekers and refugees can be active members that promote civic and political participation (Leinberger, 2006). Furthermore, migrants or refugees in Germany have the opportunity to establish organizations that produce collective goods for their group such as ethnic sports organizations, mosque, cultural organizations, political organizations, and interest groups. Furthermore, refugees can join already existing organizations and associations such as human rights and antiracist organizations, Christian humanitarian groups, and immigrants' and asylum rights organizations.

However, by joining these existing organizations or forming their own groups, refugees often face obstacles such as language skills or the complexity of the political system in Germany (Pearlman, 2017; Roth, 2017). Also, it is often the case that organizations take over as the voice of refugees and advocate the refugees' political interests to politicians (Bekaj et al., 2018). In order to shed light on the political interests of refugees, particularly Syrian refugees, we make use of the data on (subjective) interest (van Deth, 2013) in (German) politics provided by the IAB-BAMF-SOEP refugee sample. In public discourse, political interest is usually addressed in its inverse, disenchantment with politics. It is a precursor to political engagement and thus, represents a conative—i.e., action-, anticipation-, and influence-related—component of the attitude system (Breckler, 1984).

While political interest is often discussed in the context of political participation theory (Brady et al., 1995; Verba et al., 1995; van Deth, 2009; Wildenmann and Downs, 2013) not many studies focus on political interest in general and in combination with the political interest of refugees. Furthermore, the explanations of political interest are mostly based on political participation theory and do not take other factors such as the neighborhood context into account. Recent studies confirm that more factors are needed in order to explain the political interests of migrant groups (Rooij, 2012; Wass et al., 2015) and that the neighborhood context is playing an important role (Bratsberg et al., 2021; Deimel and Abs, 2022; Lindgren et al., 2022).

In the following theory section, the concept of political participation as a whole and political interest as the biggest factor leading to participation (van Deth, 2000) are described first, followed by a theory section about the neighborhood context describing how the context influences the concept of political interest.

When looking at political participation, which can be described as a behavior related to the political sphere (Lengfeld et al., 2021), several studies demonstrate that individuals' political participation can be explained by socioeconomic factors such as resources and skills as well as demographic factors (Diehl and Blohm, 2001; Mays, 2019). Verba et al. (1995) attribute political participation to social position and individual resources and show in their study that certain social groups, such as women or people with a migration background, are disadvantaged and therefore have a lower level of political participation. In order to explain political participation Verba et al. (1995) developed the Civic Voluntarism Model (CVM). In addition to the resources of their previous Socio-economic status model which incorporates variables such as income, education, and exployment status, the CVM also includes resources such as time, money and civic skills. Civic Skills are equated with communication and organizational skills. Overall, three areas are cited as favoring political activity: (1) motivation, (2) the resources such as time and money to participate in political processes, and (3) being involved in a recruitment network (Rubenson, 2000; Lüdemann, 2001). Motivation includes political interest, political knowledge, political identification, and political self-efficacy (Soßdorf, 2016). The recruitment network consists of contacts in the context of work, church, and various clubs.

As an explanation of these three additional factors, Brady et al. (1995) look at why people do not participate politically and come to the following conclusion that it is “because they can't, because they don't want to, or because nobody asked” (p. 271). Here it can be stated that the “can't” refers to time, money, and civic skills. The “not wanting to” aspect can be attributed to one's motivation, while the “not asking” aspect is related to the non-existent recruitment structures.

Political interest is understood as a precursor to political participation and as a part of one's personal attitude (Breckler, 1984). Similar to political participation, political interest is closely tied to resources, especially to education (Hadjar and Becker, 2006). Political interest is also closely tied to socialization processes and to the social context (Hadjar and Becker, 2006). For instance, the political stimuli of family and friends promotes political interest and can lead to political participation in adulthood (Kinder and Sears, 1985; Verba et al., 1995; Neundorf and Smets, 2017). People who come from a politician's family or who grow up in a politically affine family tend to show higher political interest than people who receive little or no political stimuli growing up (Neundorf et al., 2013; Quintelier, 2013, 2015). When considering people, who migrate to another country, studies show that people, who were already interested in politics in their country of origin continue to show a high level of political interest in their host/ arrival country (Wilson, 1973; Black, 1987). This illustrates a translation of previously established patterns, which is not just limited to political interest, but to political identification and participation as well (Black, 1987; Finifter and Finifter, 1989; Müssig, 2020).

However, the neighborhood context also plays an important role when it comes to political interest and political participation in general. Research about the neighborhood context can be divided into three areas: as it either highlights (1) the economic context within the neighborhood, (2) the political context within the neighborhood and/or (3) the size of social networks one has within the neighborhood.

In their studies, Huckfeldt (1979), Cohen and Dawson (1993), as well as Marschall (2004), shed light on the relevance of the neighborhood context as a factor influencing political behavior, specifically when considering the economic context within the neighborhood (1). They show that poorer neighborhoods show less political activity, while neighborhoods with a high socio-economic status promote political interest and political engagement of individuals. In a recent study Vasilopoulos et al. (2022) showed that a neighborhood with a higher unemployment rate in combination with a higher share of immigrants within a neighborhood can also influence party preference. Furthermore, Kern et al. (2015) have found a correlation between rising unemployment and an increase in political mobilization. Other than the economic context, the political environemnt (2) has also been found to influence one's political motivation factors such as political interest, voting behavior and political identification (Brown, 1981; Harrop et al., 1991; Jöst, 2021; Vasilopoulos et al., 2022). Furthermore, Finifter and Finifter (1989) have shown that voting behavior and party identification become more similar to the new neighborhood to which people move.

Several studies see the reason for a higher political activity not just in the socio-economic and the political context of the neighborhood (Huckfeldt, 1979; Giles and Dantico, 1982; Harrop et al., 1991; Jöst, 2021), but also in the networks (3), especially in the number of immigrants living in the neighborhood (Nihad, 2018; Bratsberg et al., 2021; Vasilopoulos et al., 2022). Bilodeau (2008) encountered that immigrants living in an area with a higher share of immigrants are more prone to take part in political actions. This can be due to a higher possibility of recruitment via one's own community and more political discussions and information sharing taking place (Leighley and Matsubayashi, 2009; Nihad, 2018). With more political information being shared, political knowledge increases, which, further supports political participation (DeSante and Perry, 2015; Bratsberg et al., 2021). Although living in neighborhoods with people, who have a similar migration background, supports the dimensions of participation (Togeby, 1999; Bilodeau, 2008), and shows a higher level of political recruitment taking place (Nihad, 2018), access to both, immigrants and non-immigrants within one's neighborhood is most effective for political participation (Nihad, 2018). Cohen and Dawson (1993) also assume that the neighborhood context can link people to norms or to social learning, which stimulates an assimilation process regarding political behavior. Also, Finifter and Finifter (1989) have shown that the more extensive one's network is, the more likely one's party identification with a party of the host country is. Another reason that is claimed to foster political engagement is group consciousness (Verba and Nie, 1972). With the ethnic share increasing it is believed that the ethnic enclave engages more in politics when they believe that participation benefits their group and them. As an addition to the developed CVM, Verba et al. (1995), however, found that group consciousness does not have an impact on political participation when other factors such as resource endowments and other conditions of participation are taken into account. One explanation for this contradiction is that group consciousness is often constrained to only one aspect of the concept (group identity) instead of to the three dimensions of group identity, recognition of disadvantaged status and the desire for collective action to overcome this status, which can lead to misleading results (Sanchez, 2006). In contrast to the Nihad's (2018) claim that contact with non-immigrants affects political participation, Lindgren et al. (2022) could not find an effect between contact with natives and the political participation of immigrants.

We use four different sources of data in this research: the German Socio-Economic Panel v37, the main dataset of refugees IAB-BAMF-SOEP Refugees Sample, and macro-data at the district level from the German Federal Statistical Office and the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR).

The Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP)6, is a multidisciplinary household survey in Germany, interviewing about 30,000 people in 15,000 households each year. It includes not only Germans but also foreign nationals living in Germany. The SOEP includes self-reported variables such as age, gender, household composition, education, employment status, occupation, earnings, health, satisfaction, attitudes, values, and personality indicators, and more.

The IAB-BAMF-SOEP Refugee Sample in Germany (Brücker et al., 2017; Kuehne et al., 2019) is a survey which is collected as part of the Socio-Economic Panel [SOEP, see Goebel et al. (2019)] with a focus on migrants seeking protection from political persecution, war, and conflict and has been conducted annually since 2016. It is representative of the nationalities and demographic characteristics of refugees who arrived in Germany in 2013 or later. Our research topic (interest in politics and attitudes toward the political system in Germany) was conducted mainly in 2017 and 2018.7 Therefore, we pool information from those two waves. The survey is well-suited for our empirical strategy because it provides information on refugees' residences at the time of the survey and their first residences and the level of interest in (German) politics. This information allows us to exploit the exogenous allocation of refugees to different German districts. The total sample includes 9,760 adults (18 years and older), i.e., 5,485 in 2017 and 4,275 in 2018. For the empirical analysis, we define our analysis sample as follows: (i) we include only Syrian refugees or asylum seekers8 of working age who participated in at least one of the 2017-2018 waves of the IAB-BAMF-SOEP survey; (ii) we further restrict the sample to refugees who provide information on their interest in German politics; (iii) we also limit the sample to refugees whose interview was during their first 3 years of residence in Germany to ensure that our sample only includes refugees who are exogenously allocated to districts; (iv) we then drop respondents without information on their primary residence. In our final sample, we examine 2,2739 Syrian refugees of both genders, distributed among 289 districts and were between 18 and 64 years old during the survey year. Table 1 shows a summary of all variables of interest for this paper.

Before we start with the empirical analysis, we give a descriptive overview of political interest among Syrian refugees. Thus, we compare our study group (Syrian refugees) with German citizens in terms of their interest in politics10, then we illustrate the level of interest in German politics among Syrian refugees as a function of several individual characteristics [gender (male | female), level of education before migration (low | medium | high), and years of residence in Germany (1 | 2 | 3)].

In the empirical part, we aim to determine the influence of the primary residence of refugees on their interest in German politics. Our outcome “Interest in German politics” is a dummy variable that takes the 1 if refugees are weakly, strongly or very strongly interested in German politics, and the value 0 if they have no interest at all.11 In addition to the primary residence effect, we illustrate the role of individual socioeconomic characteristics of refugees on their interest in German politics.

In our identification strategy, we rely on the exogenous distribution of refugees across federal states and, to some extent, counties within a federal state that can be used to credibly identify the effect of local characteristics on refugees' political interests (Edin et al., 2003; Beaman, 2012; Dustmann et al., 2016; Aksoy et al., 2020). The distribution of refugees in Germany follows a fixed two-step procedure: First, the central distribution to the federal states takes place according to the so-called “Königstein Key”12; the authorities in the federal states are responsible for the next step, the regional distribution of refugees to the districts. As many refugees are expected to stay in Germany for a long time, the federal government also passed the Integration Act in July 2016, which severely restricts the free choice of residence for refugees, and unless legal exception criteria13 apply, refugees with a temporary or permanent residence permit are obliged to stay in their primary residence for at least 3 years.

Considering that the majority of refugees are still not in employment or education, which in turn means that the exemption criteria are not met, movements within and between the federal states are considered to be unlikely among refugees in Germany. Although procedures may vary between the federal states14, they share a common feature: allocation is very rarely tied to individual desires, economic prospects, or cultural proximity (Stips and Kis-Katos, 2020). Aksoy et al. (2020) found that not only the number of refugees but also their socio-demographic characteristics are not correlated with district-level conditions. To ensure that the characteristics of the initial county allocation are not strongly correlated with the individual socioeconomic status of Syrian refugees, we follow Bratsberg et al. (2021) and fit the following set of regressions:

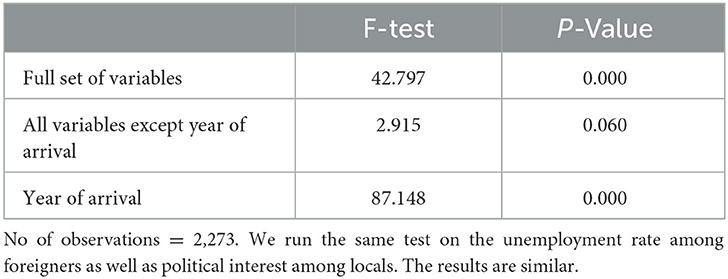

where initial_place refers to the local characteristics i.e., in our case they are ethnic social network, unemployment rate and political interest among locals, and X refers to a vector of individual-level variables measured at the time of arrival, including gender, age, level of education as well as income before migration and the year of arrival. In Table 2, we show the results of the F-tests that we run after the regression with ethnic social network. Despite the F-value being statistically significant, it is mainly driven by the set of arrival year dummies; other covariates produce only small F-values when years of arrival are included. We therefore can conclude that characteristics of the initial allocation are quasi-exogenous if we control for arrival year fixed effects.

Table 2. F-tests of relationship between ethnic social network and individual characteristics in districts at the time of arrival.

Our empirical strategy is to exploit variations across districts in Germany to estimate the effects of different characteristics (e.g., social network, economic situation, and political environment) on Syrian refugees' interest in German politics. Therefore, we control for unobservable variables by including the fixed effect of federal state in the year of refugee arrival (Bratsberg et al., 2021). This allows us to control for a number of factors that apply to districts in a federal state and that could affect the outcome variables but that we cannot observe directly (e.g., migration- and integration-related policies and measurements). In addition, we control for a number of individual socioeconomic characteristics—such as age, gender, city of origin, religion, health, accommodation situation and pre-migration economic, and educational status—that could influence interest in German politics.

Our baseline estimation equation is as follows:

where yijt is the outcome of interest, which in our case represents if refugee i in district j at the time t is interested in German politics or not. initial_placeijt is our main vector of the explanatory variables and represents the initial place characteristics (ethnic social network, unemployment rate among foreigners and the level of political interest among locals). However, before we run our main equation, we test other different local characteristics and their correlations with the outcome. Therefore, we estimate our equation separately using: (1A) share of the same age group, (2A) share of same sex group, (3A) share country of origin (Syria), (4A) share of asylum seekers and (5A) share of foreigners at the year of arrival. The second set includes economic indicators of the place of residence at the time of arrival such as different unemployment rates: (1B) among the total population, (2B) among both sex groups, (3B) foreigners, (4B) youth, and as another indicator we consider (5B) the GDP per capita at district level at the time of arrival. In the third set we look at the political environment in the initial district of residence. Here, we consider two indicators: (1C) interest in politics among the local population15 in the initial district of residence at the time of arrival; (ii) we consider the federal parliament election “Bundestagwahlen” in 2013 also as a proxy that measures the political environment. Therefore, we take (2C) the turnout rate16 in the district and (3C) the election results of extreme right-wing political parties (NPD, AFD) as well as (4C) the result of other parties which were elected into the parliament in 2013 (Union, SPD, Green party, and the Left party). The Xit represents a set of individual characteristics (age at the time of the interview and its square, age at the time of arrival and its square, sex, young children in the household) (no children | at least one child under 6 years old | at least one child 6 years old or older, but no children under 6), and the interaction between sex and children, legal status in Germany, level of education before migration (per ISCED 2011), level of income before migration, German skills before migration, the dummy for city of origin (takes the value 1 if a refugee comes from Damascus or Aleppo, 0 if otherwise), religion (a dummy takes 1 if Islam and 0 if otherwise), health (subjective estimation from the interviewee takes 1 if they feel to be in good health and 0 if otherwise), and accommodation situation (a dummy takes 1 if they live in a private accommodation and 0 if otherwise). Zjt represents a set of control variables at the district level such as the population size and the density at the time of arrival (the value in 1,000). ωi; φt ;τt are federal state fixed effects and time fixed effects of arrival year and year of survey. εijt is the error term.

We use the high dimensional fixed effects regression model to estimate our equation. For that we apply the stata command “reghdfe”17 which also allows us to cluster the standard error at the individual and district levels.

Before we answer our research question, we aim to provide a descriptive overview of the political interest among Syrian refugees in this section. Therefore, we provide a general comparison of the local population regarding their political interest and then we try to cluster the interest in German politics among Syrians by selected socioeconomic characteristics.

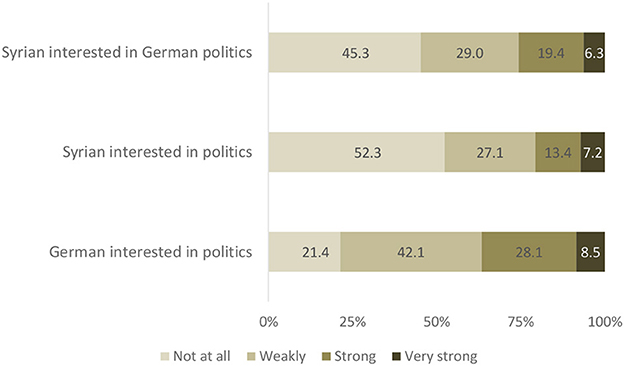

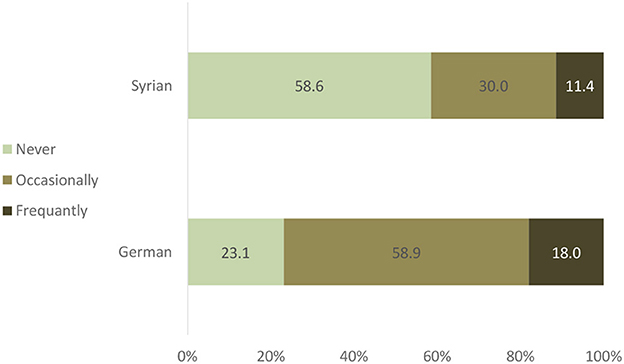

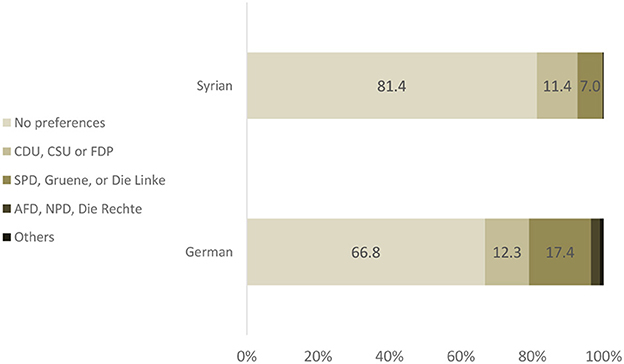

Compared to Germans, Syrian refugees have a significantly lower interest in politics. As Figure 1 shows, about half of the Syrian refugees in Germany answered “not at all” to the question of whether they are interested in politics in general or in German politics in particular.18 The lack of interest in politics is also reflected in Figure 2, which shows that 59% of Syrian refugees in Germany never talk about politics in their daily lives, while less than a quarter of Germans have never discussed political issues. Furthermore, Figure 3 shows that the majority of Syrian refugees have no party preferences (81%). Those who lean toward a German political party are mainly distributed among the parties that formed the government at the time in 2017–2018 (CDU/CSU and SPD). However, Syrian refugees show more interest in German politics in comparison to political topics in general (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Interest in (German) politics, comparison between Syrian and German population 2017/2018. Source: SOEP, survey years 2017–2018, own calculation.

Figure 2. Discuss politics, comparison between the Syrian and German population 2017/2018. Source: SOEP, survey years 2017–2018, own calculation.

Figure 3. Party preferences, comparison between the Syrian and German population 2017/2018. Source: SOEP, survey years 2017–2018, own calculation.

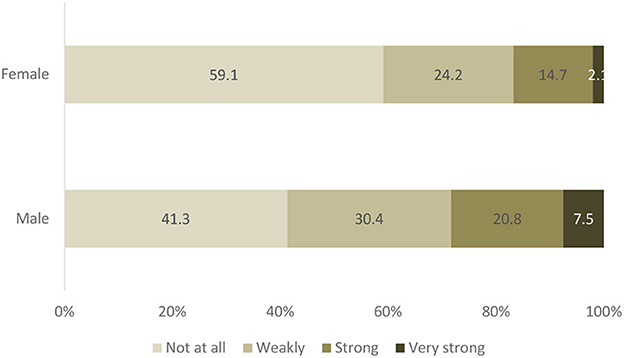

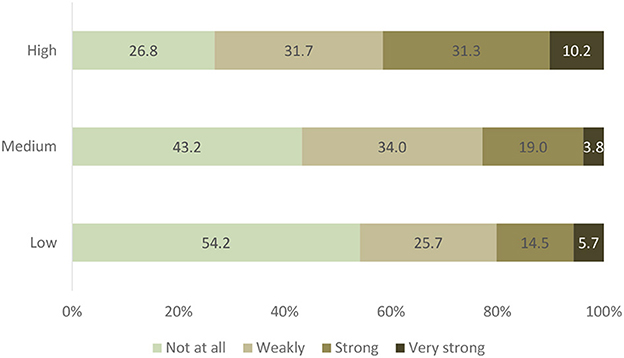

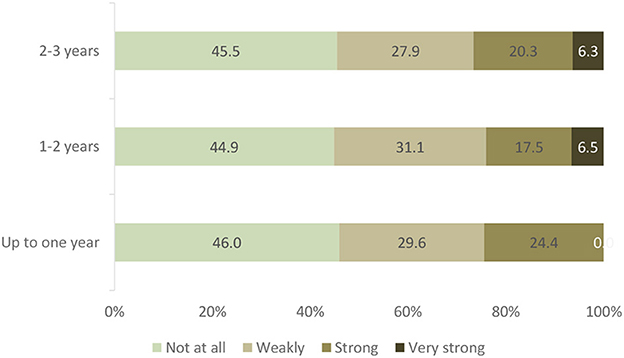

Interest in German politics among Syrian refugees varies by socioeconomic characteristics. As Figure 4 shows: a large gap between Syrian female and male refugees in terms of their interest in (German) politics. Compared to 60% of female Syrian refugees, who are not at all interested in German politics and only 17% who are (very) interested, a significantly higher percentage of male Syrian refugees in Germany are (very) interested in German politics (about 28%) and only about 40% are not interested at all. Moreover, the differences in the level of interest in German politics are also clearly shown by the differences in educational backgrounds (see Figure 5). Syrian refugees with a higher level of education have significantly more interest in German politics than those with a lower level of education. About 41% of those with a high level of education are (very) interested in German politics, compared to only about 20% of those with a low educational background. Syrian refugees do not show a very strong interest in German politics in their first year in Germany (see Figure 6). However, in the second and third year the share of Syrian refugees who are very interested in German politics reaches 6%.

Figure 4. Interest in German politics among Syrian refugees, by gender 2017/2018. Source: SOEP, survey years 2017–2018, own calculation.

Figure 5. Interest in German politics among Syrian refugees, by education 2017/2018. Source: SOEP, survey years 2017–2018, own calculation.

Figure 6. Interest in German politics among Syrian refugees, by duration of stay 2017/2018. Source: SOEP, survey years 2017–2018, own calculation.

We explore the question of how local conditions at the time of arrival influence refugees' interest in German politics. We focus on three dimensions (social networks, economic situation, and political environment). We begin by examining each dimension in order to determine which factors correlate with interest in German politics among Syrian refugees. Then, we run our main regression with all three significant local variables on which our final results are based. Finally, we conduct several sensitivity analyses to ensure the robustness of our results.

We first test the correlation between five different potential social networks for Syrian refugees and their interest in German politics. The results of the regressions can be seen in Table 3. The results indicate that the Syrian population share, (ethnic share), as a potential social network has a positive correlation with interest in German politics among Syrian refugees and is statistically significant. A 1% increase in the proportion of Syrians in the district is thus associated with a 6% higher probability of being interested in German politics, with a significance level of 0.001. In addition, the proportion of asylum seekers also shows a positive relationship, but it is less strong, i.e., a 1% increase in the proportion of asylum seekers is associated with a 2% increased likelihood of being interested in German politics. This may be related to the high proportion of Syrian asylum seekers in this group. However, all other types of social networks show no statistically significant correlation with the outcome.

Here we look at the impact of the economic situation of the initial placement of Syrian refugees on their interest in German politics. Unemployment rates, and GDP per capita are our main economic indicators. The results in Table 4 suggest that the unemployment rate has no significant explanatory power for Syrian refugees' interest in German politics. In fact, the only economic indicator that appears to have a statistically significant correlation with the dependent variable is the unemployment rate among the foreign population. In other words, a 1% increase in the unemployment rate among foreigners in a district is associated with a 2% increase in the probability of being interested in German politics. The income variables, as well as other unemployment rates, do not have statistically significant coefficients that could be interpreted in the context of the main outcome of interest.

As a proxy for the political environment in the initial placement district, we consider three indicators: the turnout rate of the federal parliament election ‘Bundestagwahl (BTW)' in 2013, the result of radical right-wing political parties, and the result of political parties which were elected in the Bundestag. In addition to that, we use the information on the political interest of the local population in the year of arrival at the district level. The regression results shown Table 5 suggest that the level of political interest among the local population has a significant positive correlation with the interests of Syrian refugees in German politics where a 10% increase in the level of political interest is associated with a 5% of probability of a Syrian refugee being interested in German politics. The turnout rate and election results show only a short-term and very weak association with the probability of being interested in German politics.

Variables in the first three models are interacted with the year of arrival. In the fourth model, there is no interaction term.

In a further step, we now add all three statistically significant local variables (share of Syrians, unemployment rate among foreigners, and interest in politics among locals in the district at the year of arrival) in one regression. In this way, we can ensure that we control for all potential influence factors of initial district placement on the interest in German politics among Syrian refugees. Table 6 shows the results of the main regression.

First, the findings of the regression suggest that the socioeconomic status of Syrian refugees has an undeniable relationship with the likelihood of being interested in German politics. A female Syrian refugee has a 10% lower probability of being interested in German politics than a male Syrian refugee. Moreover, the probability of being interested in German politics is further decreased by approximately 13% among women who have children in their household under 6 years old in comparison to women who do not have children at all. Syrian refugees with higher educational attainment have a significantly higher probability (24%) to be interested in German politics in comparison to those with a medium or low education level. Moreover, Syrian refugees who have a positive response on their asylum application, i.e., their legal status allows them a (temporary) residence permit in Germany are 11% less likely to be interested in German politics than refugees who do not have a residence permit.

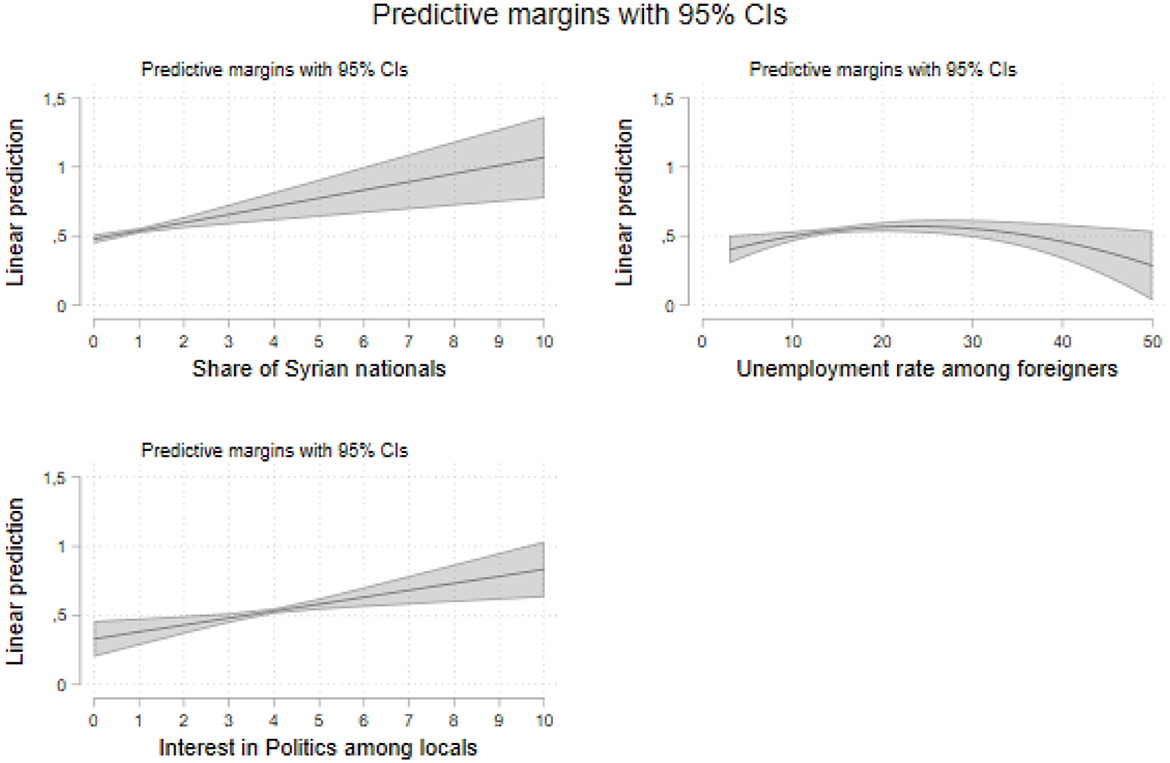

Our findings regarding the initial placement could be interpreted in a way that the local characteristics do have an effect on the interest in German politics among Syrian refugees and through different channels. The probability of being interested in German politics will increase by about 6% if the share of the Syrian population in the district of initial placement increases by 1%. The unemployment rate among foreigners also shows a positive effect on political interest. Hence, we can say that the interest in German politics will increase by 2% if the unemployment rate increases by 1% (note that the coefficient of the square value of the unemployment rate among foreigners shows a non-linear relation, i.e., at some point of the relatively very high unemployment rate, the relation with probability with the interest in German politics, turns to be negative). Finally, the political environment in the initial placement among the local population has a non-negligible effect on the level of interest in German politics among Syrian refugees.

To illustrate this finding more clearly and get an even better sense of the effect, we calculate the predicted probability of being interested in German politics by the share of Syrian nationals, the level of unemployment rate among foreigners and the level of interest in politics among locals as shown in Figure 7 (it is based on the result shown in Table 6). The figure shows that the probability of being interested in German politics increases substantially as ethnic share increases. For example, a Syrian refugee has been placed in a district where the ethnic share (7 percent) is more than 1.5 times as likely to be interested in German politics than a similar individual living in a district, where ethnic share is at 3 percent. The same goes for the interpretation of the political environment. However, as Figure 7 shows the non-linear relation between the unemployment rate among foreigners and the likelihood of being interested in politics. Thus, refugees who are placed in a district with a higher unemployment rate among foreigners are more likely to be interested in German politics, but this effect is inverted after the unemployment rate hits 25%.

Figure 7. Predictive margins, based on the main regression (Table 6).

To ensure the validation of our results we run several sensitivity analyses with more sample restrictions or even extensions. One could assume a biased estimation by districts with too few observations. Therefore, we exclude all districts with less than 10 observations (they are 141 districts and 423 observations that we exclude). The results as shown in Appendix Table 2A still supports our main findings. On the other hand, it could be argued that the large districts, especially those that also represent a whole federal state (Bundesland), could bias our findings as well. Based on that, we run the regression after excluding Berlin, Hamburg, Bremen, and Saarland.19 Again, our findings remain valid. Due to the differences between East and West Germany, we run our regression with East and West Germany separately. The result is driven mainly by West Germany, but the low number of Syrian refugees in the Eastern part could be the reason. Moreover, we check if the repeated observations in our sample bias our result. Therefore, we run our regression again, once with only the first occurrence in the survey (2017) and once with the last one (2018). The results remain robust.

Furthermore, we relax the sample restriction, in which we only consider Syrian refugees whose interview was during their first three years of residence in Germany. Thus, we include all Syrian refugees who arrive in Germany in 2013 or later. The results confirm our findings and ensure their robustness. However, caution must be exercised in interpreting causality because the random distribution no longer holds after the sample restriction is relaxed. Finally, we change the dependent variable to ‘interested in politics in general' to test whether the characteristics of the initial location have an effect specifically on the interest in German politics or on politics in general. The result shown in the Appendix Table 1A suggests that initial location in Germany affects the probability of being interested in German politics rather than in politics in general.

Moreover, we run a logit regression model. An advantage of this model is that we can take the binary nature of our dependent variable into account. Furthermore, given that our dependent variable originally has a scale from 1 (not interested at all) to 4 (very strongly interested), recoding it as a dummy variable could cause a loss of information. Therefore, we run our regression again using multinomial logit regression as seen in Appendix Table 6A. Our results are valid. However, the effects at level 4 are not significant any more, which could be related to the small number of observations at this level. In a further step, we test the ability of generalization of our findings. Therefore, we try to apply our analysis to the sample of all refugees20 in Germany. Looking at the results in Appendix Table 4A, we can, to some extent, apply our findings to the whole group of refugees in Germany.

In this article, we outline the interest of Syrian refugees in German politics and what impacts this interest.

Our key finding regarding the neighborhood context suggests that the ethnic social network plays a significant role in boosting the interest of new refugee arrivals in German politics. Common concerns and language skills are very decisive as a mechanism of this role. These results are in line with migration literature on the importance of the ethnic enclave as a source of information and motivation for political participation, particularly in the initial phase (Leighley and Matsubayashi, 2009; Nihad, 2018; Bratsberg et al., 2021; Lindgren et al., 2022). However, these findings challenge the group consciousness argument by Verba et al. (1995) which claims that belonging to a certain ethnic group—operationalized by ethnic group consciousness, experiences of discrimination and perceptions of commonly shared problems—has no independent influence on the extent of political participation once one controls for resource endowments and other conditions of participation. In fact, this study shows that ethnic share does indeed have an effect on the political interest of Syrian refugees if one controls for socio-demographic and socio-economic variables. A more thorough study is needed, however, in order to investigate which dimensions of the group consciousness model affects the political interest of Syrian refugees. In contrast to Bilodeau (2008) and in line with Lindgren et al. (2022), we find that a higher share of foreigners or the native population in the neighborhood in general does not affect the political interest of Syrian refugees.

When considering the economic situation of the neighborhood context theory our results cannot confirm traditional findings by Huckfeldt (1979), Cohen and Dawson (1993), or Marschall (2004), as the neighborhood unemployment rate and GDP per capita do not have an effect on the political interest of Syrian refugees. However, when considering unemployment rates among the foreign population, a positive effect on the political interest of Syrian refugees can be observed. This finding is consistent with Kern et al. (2015), i.e., rising unemployment is associated with an increase in (non)institutionalized political participation, which is to some extent applicable to Syrian refugees' political interest.

Our results can also confirm that political context has an effect on political motivational factors (Brown, 1981; Harrop et al., 1991; Jöst, 2021; Vasilopoulos et al., 2022), as high political interest among the local population in Germany leads to higher political interest among Syrian refugees. Electoral events and their voter turnout and election results show only very weak associations with the likelihood of being interested in German politics. This could conceivably stem from the fact that Syrian refugees were not yet eligible to vote, so that voter turnout does not yet affect them. However, further studies should investigate how this influence changes with a higher proportion of naturalized Syrians.

Regarding our descriptive results, we found that Syrian refugees are less interested in politics compared to the German population. Their lack of political interest is also reflected in the abundance of party preference as well as in the abundance of political discussions. Interestingly, the descriptive statistics also show that Syrian refugees are slightly more interested in German politics compared to political topics in general. Looking at socio-economic and socio-demographic factors, it comes as no surprise that resources such as education have a big impact on political interest. This aligns with traditional political participation research as higher-educated people are more politically interested than those with lower education (Verba et al., 1995). Another unsurprising finding was that female refugees are less interested in German politics than male refugees. Considering traditional political and gender participation studies, women tend to be less politically active and less interested. Often “time” is the explaining factor, as many women care for children. Additionally, in this case female refugees with children under 6 years of age show lower political interest than women who do not have children at all.

Overall, our results show that the neighborhood context, in particular the ethnic share, does play an important role next to other traditional socio-economic and socio-demographic factors for political interest. With only a few studies shedding light on the neighborhood context within their national settings so far (Bratsberg et al., 2021; Lindgren et al., 2022), this study represents the first quantitative article relating neighborhood context theory to the political interest of Syrian refugees in a German setting.

We have to mention that our study does have some limitations as our data only represents Syrian refugees from the years 2017 and 2018. Since the database does not include variables concerning political participation, NGO membership or the political background of the family, we cannot link our political interest variable to political participation and therefore do not know whether political interest is translated into political engagement after all. Furthermore, more data regarding the origin country is needed to order to fully explain why some cities lead to a higher interest in politics than others.

Nevertheless, this study is significant for future policies regarding refugees, especially when it comes to their allocation since this article proves that the neighborhood context is not only relevant for social and economic integration, but also for political interest. While this article only focuses on Syrian refugees, future research should also focus on other refugee groups or take other countries as their setting. While our study focuses on a macro-perspective, future studies should also aim to go even more in-depth by looking at the mechanisms driving Syrian refugees' interest in German politics. This could be done by qualitative narrative interviews with either Syrian or other refugee groups in order to find out what factors influence the political interest and understand why they do so. Another option would be a survey experiment with a hypothetical situation and hypothetical action. This would allow for separately measuring the factors of influence without the problems of real-world correlations and even make measuring (hypothetical) political action possible. This dissection would also allow for deeper insights regarding policy recommendations.

The datasets analyzed in this study can be found online via the following link: https://www.diw.de/de/diw_01.c.601584.de/datenzugang.html.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

We would like to thank all IAB-colleagues for their data preparation and helpful comments as well as all colleagues of the NRW Ph.D. programme Online Participation for their extensive feedback.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2023.1100446/full#supplementary-material

2. ^In English: “We can make it”. A statement made by Angela Merkel on 31.08.2015. For more information see Phoenix (2015).

3. ^In English: “Yes we have made it, we have arrived”. Tareq Alaows: He would be the first Syrian refugee to become a parliamentarian in the Bundestag (federal election, 2021). Yet he gave up after being harassed and threatened. For more information see Deutsche (2021).

4. ^The Damascus Declaration (DD) is a secular opposition umbrella coalition called for a multiparty democracy in Syria, named after a declaration written in 2005 by numerous opposition groups and individuals. It calls for a gradual and peaceful transition to democracy and equality for all citizens in a secular and sovereign Syria. For more information see Carnegie Middle East Center (2012).

5. ^For more information on the political situation in Syria after 2011, see TDA (2015).

6. ^The Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP): SOEP-Core v37, EU Edition, 2022. For more information see Liebig et al. (2022)

7. ^The variable on the interest in politics in general was conducted in each year.

8. ^From here on, we refer to asylum seekers and recognized refugees as “refugees”.

9. ^In 1,775 individuals have participated only once (547 in 2017 & 730 in 2018); 498 individuals have participated twice.

10. ^There are certain discrepancies between the German nationals and the group of Syrian refugees regarding their demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Therefore, we use a matching approach to ensure the comparability of the two groups. We use the stata-command “ebalance” (Hainmueller and Xu, 2013) which allow us to reweight the control group (the German citizens in this case) depending on several socio-economic and demographic variables. We control for the following individual characteristics: Gender is a dummy variable (0 if male | 1 if female); Age is a categorial variable illustrates 3 age groups (18–29 | 30–49 | 50-max); Education level is a categorial variable illustrates 3 level of education according to the International Standard Classification of Education 2011 (ISCED 0–2 low | 3–4 medium | 5–8 high education); Employment status is a dummy variable (0 if unemployed | 1 if employed); Federal state is a dummy variable for the federal state of place of residence; Survey year is a dummy variable for the year of survey.

11. ^The variable is based on the question: (How interested are you in politics in Germany? [1] Very interested [2] Moderately interested [3] Weakly interested [4] Completely disinterested). In the robustness check section, we use the categorical nature of the variable and we run a multinomial logit regression in order to ensure that we do not lose information through recoding the variable as binary dummy.

12. ^According to the “Königstein Key”, the distribution across the federal states is based on population and tax revenue. Distribution within the Federal states is often based on population and the availability of housing.

13. ^Finding a job or vocational training offer or university place.

14. ^In six out of 16 Federal States, approved refugees are allocated to certain regions within the state (districts or municipalities), typically the region where they have received their asylum decision.

15. ^This variable comes from the SOEP dataset. We use the question “how are you interested in politics?” “1 Not at all, 2 Weakly, 3 Strong, 4 Very strong”. We then transfer the 4 scale to 1–10 scale (to ease the interpretation) and we use the aggregated mean at district level as political environment indicator.

16. ^Depending on the election system in Germany Turnout rate is measured by the second vote [to a party and not to direct candidate (Zweitstimme)].

17. ^For more information see Correia (2014, revised 2019).

18. ^The more recent data on interest in politics (2019–2020) does not show significant difference.

19. ^Saarland has many districts but one Foreigner office, that's why we consider it as one district.

20. ^All refugees who provide information on their country of origin in the survey.

Aksoy, C. G., Carpenter, C. S., De Haas, R., and Tran, K. D. (2020). Do laws shape attitudes? Evidence from same-sex relationship recognition policies in Europe. Eur. Econ. Rev. 124, 103399. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2020.103399

Beaman, L. (2012). Social networks and the dynamics of labour market outcomes: evidence from refugees resettled in the U.S. Rev. Econ. Stud. 79, 128–161. doi: 10.1093/restud/rdr017

Bekaj, A., Antara, L., Adan, T., de Casanova, J.-T. A., El-Helou, Z., Mannix, E., et al. (2018). Political Participation of Refugees: Bridging the Gaps. Sweden: International IDEA. doi: 10.31752/idea.2018.19

Bilodeau, A. (2008). Immigrants' voice through protest politics in Canada and Australia: assessing the impact of pre-migration political repression. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 34, 975–1002. doi: 10.1080/13691830802211281

Black, J. H. (1987). The Practice of Politics in Two Settings: Political Transferability Among Recent Immigrants to Canada. Canad. J. Polit. Sci. 20, 731–753. doi: 10.1017/S0008423900050393

Bloemraad, I. (2005). The Limits of de Tocqueville: How Government Facilitates Organisational Capacity in Newcomer Communities. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 31, 865–887. doi: 10.1080/13691830500177578

Bloemraad, I., and Schönwälder, K. (2013). Immigrant and Ethnic Minority Representation in Europe: Conceptual Challenges and Theoretical Approaches. West European Politics 36, 564–579. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2013.773724

Brady, H. E., Verba, S., and Schlozman, K. L. (1995). Beyond SES: A resource model of political participation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 89, 271–294. doi: 10.2307/2082425

Bratsberg, B., Ferwerda, J., Finseraas, H., and Kotsadam, A. (2021). How settlement locations and local networks influence immigrant political integration. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 65, 551–565. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12532

Breckler, S. J. (1984). Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 47, 1191–1205. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.47.6.1191

Brown, T. A. (1981). On contextual change and partisan attributes. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 11, 427–447. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400002738

Brücker, H., Rother, N., and Schupp, J. (2017). IAB-BAMF-SOEP Refugee Survey: Outline. Available online at: https://doku.iab.de/fdz/iab_bamf_soep/IAB-BAMF-SOEP-REF-Kurzbeschreibung_en.pdf (accessed August 15, 2021).

BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNE (2021). Mitglied werden - BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN. Available online at: https://www.gruene.de/mitglied-werden (accessed July 1, 2021).

Carnegie Middle East Center (2012). The Damascus Declaration. Carnegie Middle East Center - Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available online at: https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/48514?lang=en (accessed November 12, 2022).

CDU CSU SPD. (2018). Koalitionsvertrag zwischen CDU, CSU und SPD. Deutscher Bundestag. Available online at: https://archiv.cdu.de/system/tdf/media/dokumente/koalitionsvertrag_2018.pdf?file=1 (accessed December 15, 2022).

Cohen, C. J., and Dawson, M. C. (1993). Neighborhood poverty and african american politics. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 87, 286–302. doi: 10.2307/2939041

Correia, S. (2014). REGHDFE: Stata module to perform linear or instrumental-variable regression absorbing any number of high-dimensional fixed effects. Boston College Department of Economics.

Daher, J. (2018). The political economic context of Syria's reconstruction: a prospective in light of a legacy of unequal development. European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies.

Dancygier, R. (2013). “Culture, Context, and the Political Incorporation of Immigrant-origin Groups in Europe,” in Outsiders No More? Models of Immigrant Political Incorporation, eds. J., Hochschild, J., Chattopadhyay, C., Gay, and M., Jones-Correa (New York: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199311316.003.0008

de Graauw, E., and Vermeulen, F. (2016). Cities and the politics of immigrant integration: a comparison of Berlin, Amsterdam, New York City, and San Francisco. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 42, 989–1012. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2015.1126089

Deimel, D., and Abs, H. J. (2022). Local Characteristics shape the intended political behaviours of adolescents. Soc. Indic. Res. 162, 619–641. doi: 10.1007/s11205-021-02852-y

DeSante, C. D., and Perry, B. N. (2015). Bridging the Gap. Am. Polit. Res. 44, 548–577. doi: 10.1177/1532673X15606967

Deutsche, W. (2021). Meinung: Wenn Tareq Alaows nicht kandidieren kann, verlieren wir alle. Deutsche Welle. Available online at: https://www.dw.com/de/meinung-wenn-tareq-alaows-nicht-kandidieren-kann-verlieren-wir-alle/a-57075307 (accessed November 13, 2022).

DIE LINKE (2021). Gibt es bestimmte Voraussetzungen, um bei der LINKEN mitmachen zu können? Available online at: https://archiv2017.die-linke.de/partei/eintreten/faq-zum-parteieintritt/gibt-es-bestimmte-voraussetzungen-um-bei-der-linken-mitmachen-zu-koennen/ (accessed July 1, 2021).

Diehl, C., and Blohm, M. (2001). Apathy, adaptation or ethnic mobilisation? On the attitudes of a politically excluded group. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 27, 401–420. doi: 10.1080/136918301200266149

Dustmann, C., Schönberg, U., and Stuhler, J. (2016). The impact of immigration: why do studies reach such different results? J. Econ. Perspect. 30, 31–56. doi: 10.1257/jep.30.4.31

Edin, P.-A., Fredriksson, P., and Aslund, O. (2003). Ethnic enclaves and the economic success of immigrants–evidence from a natural experiment. Quart. J. Econ. 118, 329–357. doi: 10.1162/00335530360535225

FDP (2019). Bundessatzung. Available online at: https://www.fdp.de/sites/default/files/import/2020-01/8077-fdp-bundessatzung-broschuere-2019-10.pdf (accessed July 1, 2021).

Finifter, A. W., and Finifter, B. M. (1989). Party identification and political adaptation of American migrants in Australia. J. Politics 51, 599–630. doi: 10.2307/2131497

Gesemann, F., and Roth, R. (2014). Integration ist (auch) Ländersache! Schritte zur politischen Inklusion von Migrantinnen und Migranten in den Bundesländern. Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Giles, M. W., and Dantico, M. K. (1982). Political participation and neighborhood social context revisited. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 26, 144. doi: 10.2307/2110844

Goebel, J., Grabka, M. M., Liebig, S., Kroh, M., Richter, D., Schröder, C., and Schupp, J. (2019). The German socio-economic panel (SOEP). Jahrbücher Nationalökonomie Statist. 239, 345–360. doi: 10.1515/jbnst-2018-0022

Hadjar, A., and Becker, R. (2006). “Politisches Interesse und politische Partizipation,” in Die Bildungsexpansion. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften 179–204. doi: 10.1007/978-3-531-90325-5_7

Hainmueller, J., and Xu, Y. (2013). Ebalance : A stata package for entropy balancing. J. Stat. Softw. 54, 1–18. doi: 10.18637/jss.v054.i07

Hanewinkel, V., and Oltmer, J. (2017). Integration und Integrationspolitik in Deutschland. Migrationsprofil Deutschland. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Available online at: https://www.bpb.de/gesellschaft/migration/kurzdossiers/265044/integration-und-integrationspolitik (accessed March 27, 2020).

Harrop, M., Heath, A., and Openshaw, S. (1991). Does neighbourhood influence voting behaviour - and why? Br. Elect. Part. Yearbook 1, 101–120. doi: 10.1080/13689889108412897

Huckfeldt, R. R. (1979). Political participation and the neighborhood social context. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 23, 579. doi: 10.2307/2111030

Human Rights Watch (2010). Syria: Al-Asad's Decade in Power Marked by Repression of 7/16/2010. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2010/07/16/syria-al-asads-decade-power-marked-repression (accessed November 12, 2022).

Hunger, U., and Candan, M. (2009). Politische Partizipation der Migranten in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und über die deutschen Grenzen hinweg. Münster, Universität Münster, FB Erziehungswissenschaft und Sozialwissenschaften, Institut für Politikwissenschaft.

International Crisis Group (2004). Syria under Bashar (II): domestic policy challenges. Amman/ Brussels.

Jöst, P. (2021). Where do the less affluent vote? The effect of neighbourhood social context on individual voting intentions in England. Polit. Stud. doi: 10.1177/00323217211027480

Kern, A., Marien, S., and Hooghe, M. (2015). Economic crisis and levels of political participation in europe (2002–2010): The Role of Resources and Grievances. West Eur. Polit. 38, 465–490. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.993152

Kinder, D. R., and Sears, D. O. (1985). “Public Opinion and Political Action,” in The Handbook of Social Psychology, 3rd eds G., Lindzey, and E., Aronson (Random House) 659–741.

Koopmans, R. (2004). Migrant mobilisation and political opportunities: Variation among German cities and a comparison with the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 30, 449–470. doi: 10.1080/13691830410001682034

Kuehne, S., Jacobsen, J., and Kroh, M. (2019). Sampling in times of high immigration: the survey process of the IAB-BAMF-SOEP survey of refugees. Survey Methods: Insights from the Field. doi: 10.13094/SMIF-2019-00005

Lange, K. (2013). Syrien: Ein historischer Überblick. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung of 2/14/2013. Available online at: https://www.bpb.de/shop/zeitschriften/apuz/155119/syrien-ein-historischer-ueberblick/ (accessed November 13, 2022).

Leighley, J. E., and Matsubayashi, T. (2009). The Implications of Class, Race, and Ethnicity for Political Networks. Am. Polit. Res. 37, 824–855. doi: 10.1177/1532673X09337889

Leinberger, K. (2006). Migrantenselbstorganisationen und ihre Rolle als politische Interessenvertreter. Am Beispiel zweier Dachverbände in der Region Berlin-Brandenburg. Berlin: Münster, Lit.

Lengfeld, H., Liebig, S., and Märker, A. (2021). Politisches Engagement, Protest und die Bedeutung sozialer Ungerechtigkeit. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Available online at: https://www.bpb.de/shop/zeitschriften/apuz/25732/politisches-engagement-protest-und-die-bedeutung-sozialer-ungerechtigkeit/ (accessed September 18, 2022).

Liebig, S., Goebel, J., Grabka, M., Schröder, C., Zinn, S., Bartels, C., et al. (2022). Sozio-oekonomisches Panel, Daten der Jahre 1984-2020 (SOEP-Core, v37, EU Edition).

Lindgren, K. O., Nicholson, M. D., and Oskarsson, S. (2022). Immigrant political representation and local ethnic concentration: Evidence from a Swedish refugee placement program. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 52, 997–1012. doi: 10.1017/S0007123420000824

Lüdemann, C. (2001). “Politische Partizipation, Anreize und Ressourcen. Ein Test verschiedener Handlungsmodelle und Anschlußtheorien am ALLBUS 1998,” in Politische Partizipation in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Empirische Befunde und theoretische Erklärungen 43–71. doi: 10.1007/978-3-322-99341-0_3

Maktabi, R. (2010). Gender, family law and citizenship in Syria. Citizenship Stud. 14, 557–572. doi: 10.1080/13621025.2010.506714

Marschall, M. J. (2004). Citizen participation and the neighborhood context: a new look at the coproduction of local public goods. Polit. Res. Quart. 57, 231–244. doi: 10.1177/106591290405700205

Marshall, M. G. (2014). Polity IV Project: Country Reports 2010. Available online at: https://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm (accessed January 20, 2022).

Mays, A. (2019). Fördert Partizipation am Arbeitsplatz die Entwicklung des politischen Interesses und der politischen Beteiligung? Zeitschrift Soziol. 47, 418–437. doi: 10.1515/zfsoz-2018-0126

MIPEX (2020a). Germany | MIPEX 2020. Available online at: https://www.mipex.eu/germany (accessed November 13, 2022).

MIPEX (2020b). Migrant Integration Policy Index 2020. Available online at: https://www.mipex.eu/political-participation (accessed July 16, 2021).

Moubayed, S. (2008). Syrian Reform or Repair? Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available online at: https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/21158 (accessed November 12, 2022).

Musawah (2020). Thematic Report on article 16, muslim family law and muslim women's rights in Afghanistan. Musawah. Available online at: https://www.musawah.org/resources/musawah-thematic-report-afghanistan-cedaw75-2020/ (accessed 2/3/2022).

Müssig, S. (2020). Politische Partizipation von Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund in Deutschland. Eine quantitativ-empirische Analyse. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-30415-7

Neundorf, A., and Smets, K. (2017). Political Socialization and the Making of Citizens. Nw York: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935307.013.98

Neundorf, A., Smets, K., and García-Albacete, G. M. (2013). Homemade citizens: The development of political interest during adolescence and young adulthood. Acta Polit. 48, 92–116. doi: 10.1057/ap.2012.23

Nihad, E. (2018). Local Conditions of Democracy – The relevance of neighborhoods for first and second-generation immigrants. Berlin, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Pearlman, W. (2017). Culture or Bureaucracy? Challenges in Syrian Refugees' Initial Settlement in Germany. Middle East Law Govern. 9, 313–327. doi: 10.1163/18763375-00903002

Phoenix (2015). Flüchtlingspolitik: “Wir schaffen das”-Statement von Angela Merkel am 31.08.2015, 31.08.2015. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kDQki0MMFh4 (accessed November 13, 2022).

Quintelier, E. (2013). “The Effect of Political Socialisation Agents on Political Participation Between Ages Sixteen and Twenty-one,” in Growing into politics. Contexts and timing of political socialisation, eds. S. Abendschön, A., Blanc, N., Cavazza (Colchester, ECPR Press Univ. of Exter) 139–160.

Quintelier, E. (2015). Engaging adolescents in politics. Youth Soc. 47, 51–69. doi: 10.1177/0044118X13507295

Ragab, N. J., and Antara, L. (2018). Political Participation of Refugees. The Case of Afghan and Syrian Refugees in Germany. doi: 10.31752/idea.2018.14

Rapp, C. (2018). National attachments and the immigrant participation gap. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 46, 2818–2840. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1517596

Reid, K. (2022). Syrian refugee crisis: Facts, FAQs, and how to help. World Vision of 7/12/2022. Available online at: https://www.worldvision.org/refugees-news-stories/syrian-refugee-crisis-facts (accessed November 13, 2022).

Rooij, E. A. (2012). Patterns of immigrant political participation: explaining differences in types of political participation between immigrants and the majority population in western Europe. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 28, 455–481. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcr010

Roth, R. (2017). “Politische Partizipation von Migrantinnen und Migranten,” in Stadtentwicklung. Politische Partizipation von Migrantinnen und Migrantinnen 243–247.

Rubenson (2000). Participation and Politics: Social Capital, Civic Voluntarism and Institutional Context. Available online at: https://ecpr.eu/Filestore/PaperProposal/00cdee63-6d2e-478e-91a6-4d6de3a01a2b.pdf (accessed April 20, 2020).

Ruedin, D. (2017). Participation in Local Elections: ‘Why Don't Immigrants Vote More? Parliament. Affai. 71, 243–262. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsx024

Sanchez, G. R. (2006). The role of group consciousness in political participation among latinos in the United States. Am. Polit. Res. 34, 427–450. doi: 10.1177/1532673X05284417

Soßdorf, A. (2016). Zwischen Like-Button und Parteibuch. Die Rolle des Internets in der politischen Partizipation Jugendlicher. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-13932-2

Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (2021). Soziale Politik für Dich – für 83 Millionen. Für dich – und mit dir. Werde jetzt SPD-Mitglied! Available online at: https://www.spd.de/unterstuetzen/mitglied-werden/ (accessed July 1, 2021).

Statista (2022a). Ausländer aus Syrien in Deutschland bis 2020 | Statista. Available online at: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/463384/umfrage/auslaender-aus-syrien-in-deutschland/ (accessed May 1, 2022).

Statista (2022b). German population by migrant background 2021 | Statista. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/891809/german-population-by-migration-background/ (accessed November 13, 2022).

Statistisches Bundesamt (2022). 20% mehr Einbürgerungen im Jahr 2021. Pressemitteilung Nr. 237 vom 10. Juni 2022. Available online at: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2022/06/PD22_237_125.html (accessed November 13, 2022).

Stips, F., and Kis-Katos, K. (2020). The impact of co-national networks on asylum seekers' employment: Quasi-experimental evidence from Germany. PLoS ONE 15, e0236996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236996

Strijbis, O. (2014). Migration background and voting behavior in switzerland: a socio-psychological explanation. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 20, 612–631. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12136

Tagesspiegel (2017). Geflüchtete in politischen Parteien: Ideen sind willkommen - Politik - Tagesspiegel. Available online at: https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/gefluechtete-in-politischen-parteien-ideen-sind-willkommen/20293224.html (accessed July 1, 2021).

TDA (2015). Negotiating a Political Solution in Syria. Opinion Survey. Available online at: https://tda-sy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Negotiating-a-Political-Solution-in-Syria.pdf (accessed February 3, 2023).

Togeby, L. (1999). Migrants at the polls: An analysis of immigrant and refugee participation in Danish local elections. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 25, 665–684. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.1999.9976709