- 1Department of Political Science, University of Lucerne, Lucerne, Switzerland

- 2Department of Sociology, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), Madrid, Spain

The increase in divorce rates over the past decades challenges the traditional image of the two-parent family, as new family forms are increasingly more common. Yet, the traditional view of the family has remained central to political socialization research. Therefore, we propose and empirically test a theoretical framework regarding the consequences of parental separation for processes of political socialization. While the impact of parental divorce has been studied extensively by sociologists, the political implications of this impactful life event have remained largely uncovered. We identify two mechanisms that we expect to predict more leftist political orientations in children of separated parents compared to those from intact families: experiences of economic deprivation and single-mother socialization. Multi-level analyses using the European Values Study (2008) and two-generational analyses with the Swiss Household Panel (1999–2020) support our expectations, indicating that in case of parental separation offspring tends to hold more leftist political orientations, controlling for selection into parental separation and the intergenerational transmission of political ideology. We find empirical support for mechanisms of economic deprivation and single-mother socialization across our analyses. The implications of our findings are that in the family political socialization process, offspring's political orientations are not only influenced by their parents' ideology, but also by formative experiences that result from the family structure.

Introduction

The increase in divorce rates over the past decades challenges the traditional image of the two-parent family: divorce rates have doubled since the 1970s, and up to 25 per cent of children now grow up in a single-parent household (OECD, 2018; Eurostat, 2022). Yet, the traditional two-parent household with a stable union remains most often central to political socialization research (Jennings and Niemi, 1971; Beck and Jennings, 1975; Rico and Jennings, 2016; Hatemi and Ojeda, 2021), even though this no longer reflects the reality of many families in advanced democracies. Despite this significant demographic change, little is known about how family structure interferes in processes of political socialization while family sociologists consistently show on average negative consequences of parental divorce and separation1 for different life outcomes of their offspring, including psychological wellbeing, health, and educational performance (Amato, 2000; Bhrolcháin et al., 2000; Bernardi and Radl, 2014; Härkönen et al., 2017). However, despite some recent studies on the effect of (parental) divorce on political participation (Voorpostel and Coffé, 2015; Dehdari et al., 2022), hardly any studies have been conducted on the ideational and political consequences of parental separation.

Therefore, we ask whether and how parental separation affects the process of family political socialization and the intergenerational transmission of parental political attitudes. In doing so, we bring together the field of study on family political socialization and that on the consequences of parental divorce. We thereby contribute to both fields by focussing on both a process (family political socialization) and an outcome (political ideology) that has not been considered by previous studies, as well as by problematizing the assumption of the stable two-parent family in the study of the intergenerational transmission of political ideology. In particular, we contribute to the field of study on political socialization by showing that parental political socialization is complemented by additional formative early life experiences, such as parental separation, that predict political preferences in adulthood.

We develop a theoretical framework in which we relate the experience of growing up in a single-parent family as a consequence of parental divorce to political ideology later in adulthood, through differential processes of political socialization. We expect this altered political socialization experience to predict more leftist self-identification later in life in adult children of separated parents, compared to those from intact families. We identify two possible underlying mechanisms: (1) economic deprivation; and (2) single-mother socialization. The experience of economic deprivation is more often found in those growing up in single-parent families. Through this mechanism, parental separation increases the probability of growing up with scarcer resources, which could impact political attitudinal development. We also identify single-mother socialization as a factor of importance in the political development process of children of separated parents for two reasons: (i) children grow up in a norm-breaking family setting in which they are (ii) mainly socialized by the mother, who, on average, hold more leftist political views. We expect these socializing experiences to result in more left-wing self-identification in adulthood.

Our empirical analyses rely on comparative data from the European Values Study (2008) and the Swiss Household Panel (1999–2020). We focus on left-right political ideology as the main outcome variable, measured by self-identification with a position on the left-right scale. The results indicate that across Western democracies, adults with divorced parents hold more leftist political positions. This effect runs through their experiences of childhood economic deprivation and having grown up in a single-mother household. By making use of observations of two generations of respondents, analyses using the Swiss data indicate that our findings are not an artefact of parental self-selection into divorce, by including the mother-child intergenerational transmission of political ideology in our model. These results indicate that the experience of parental separation is an additional factor in the family political socialization process that is associated with more leftist self-identification in adulthood that does not solely run through the intergenerational transmission of political views. In the conclusion we further elaborate on the implications of our findings.

The political relevance of family structure

It is largely unknown what the consequences of growing up with separated parents are for the process of political socialization and the intergenerational transmission of parental political attitudes. Based on the ample evidence from sociology of negative consequences of parental separation for child socioeconomic outcomes (for overviews see Amato and Keith, 1991; Sigle-Rushton and McLanahan, 2004; Härkönen et al., 2017), we can expect this experience to also be of political relevance. Many studies in political socialization have demonstrated the importance of parents as impactful socializing agents in the process of development of political preferences and behavior (Sigel, 1965; Jennings and Niemi, 1968, 1974; Percheron and Jennings, 1981); with enduring influence until later in life on their adult children's political preferences (Jennings et al., 2009). Recent studies continue to show the relevance for parents for the political preferences of their offspring (Rico and Jennings, 2016; Kuhn et al., 2021; Van Ditmars, 2023).

However, none of the seminal studies to date in the field of political socialization have considered that a large proportion of children (up to 35–44% in France, Estonia, and the US) experience their parents' separation by the age of 15 (Andersson et al., 2017). Studies indicate that children of separated parents have lower educational attainment, decreased psychological well-being, health, and worsened parent–child relationships (Amato, 2000; Bhrolcháin et al., 2000; Kalmijn, 2013; McLanahan et al., 2013; Bernardi and Radl, 2014; Härkönen et al., 2017).2 These negative consequences often persist until in adulthood (Amato and Keith, 1991). Due to the importance of parents as key socializing agents in the political socialization process, we can thus expect that parental separation not only impacts children's cognitive and psychological development, but also their political development.

We currently have limited knowledge regarding the impact of parental separation on the political socialization process. Only one study to date has directly investigated the political effects of family structure, and did not find any effects of growing up in a single-parent family on political ideology or political cynicism in adulthood (Flouri, 2004). However, this is a single-case design, studying one specific cohort (born in 1958 in Great Britain) in which single parenthood was rather uncommon. Therefore, the external validity of the study is rather limited. Most other works studying the political effects of family structure have focussed on civic and political engagement. Dolan (1995) concludes that there is no relationship between family structure and political efficacy, political knowledge, and political participation among a representative sample of college students in the US. However, those who grew up with also a father present in the household showed somewhat higher levels of political trust. Sandell and Plutzer (2005) find a negative effect of parental separation on turnout in the US, but only for whites. More recent studies using household panel data demonstrate robust negative effects of family disruption on civic engagement (Hener et al., 2016), and political and civic participation, which partly reflects the lower participation levels of separated compared to non-separated parents (Voorpostel and Coffé, 2015).

Parental separation and family political socialization: theoretical framework

We develop a theoretical framework regarding the consequences of parental separation for family political socialization processes. The central hypothesis that we propose here, and empirically test in our analyses, is that the experience of parental separation is associated with more left-wing political orientations in adulthood. Based on the insights from the sociological study of parental divorce and the field of political socialization we identify two different mechanisms underlying this relationship.

The first mechanism through which we expect parental separation to affect the political socialization process regards the experience of economic deprivation during childhood, to which children of separated parents are more exposed. Divorce or relationship dissolution often has negative economic consequences for both partners involved, with larger economic losses for women and mothers (Andress et al., 2006; Sayer, 2006; Hogendoorn et al., 2020). Growing up in single-parent households is a major predictor of the risk of childhood poverty in many countries (OECD, 2018). We then expect that having experienced economic deprivation during childhood leads to more progressive socioeconomic attitudes and support for welfare provisions in general, and for single-parent families in specific, resulting in generally more leftist positions later in life. Flouri (2004) indeed finds the experience of economic disadvantage during childhood to result in more left-wing positions in adulthood (age 33). Regardless of individuals' own economic circumstances, the experience of relative poverty during childhood is therefore expected to leave a lasting imprint which leads to empathetic positions toward those who might benefit from welfare programs, and a corresponding leftist political orientation.

The second mechanism through which we expect parental separation to affect the political socialization process regards the direct experience of growing up in a single-mother household. Although joint custody arrangement are now rapidly increasing, the majority of parental separations result in single-mother families (OECD, 2018). The resulting political socialization experiences of these children are expected to importantly differ from those growing up in two-parent families. There are two distinct experiences that we are of political relevance in this respect.

First, there is the political socialization experience itself in a single-mother household. The social learning approach in political socialization states that offspring's political preferences are developed in relation to influences from the outside world, of which the transmission from parents to children through observation and imitation is an important foundation (Davies, 1965; Jennings and Niemi, 1974; Bandura, 1977; Percheron and Jennings, 1981). The fact that children in single-mother households spend most of their time with the mother (Koster et al., 2021) is expected to be key to the family political socialization process, as social learning does not only occur through overt transmission of preferences, but also works indirectly through the cue-taking of the children (Jennings and Niemi, 1968, p. 139). As on average, women are more likely to self-identify as leftist, hold more favorable attitudes toward redistribution than men, and are more likely to support left-wing parties (Inglehart and Norris, 2000; Abendschön and Steinmetz, 2014; Shorrocks, 2018), single-mother socialization3 is expected to result in more left-wing political orientations in their offspring, compared to those from two-parent families.

Second, we identify belonging to a norm-breaking family form another politically relevant experience of growing up in a single-mother household. Even though divorce and union dissolution of parents is becoming more and more common, this family form does not align with the traditional model of the two-parent family in which most current adults have grown up. The extent to which there is, and used to be, a social stigma associated with single-mother households is highly dependent on the country and social context of the family in question, as the acceptance of parental separation differs across countries, social groups, and over time (Gelissen, 2003). We argue that belonging to this non-standard family type, deviating from existing social norms, could result later in life to being less conforming and holding more liberal attitudes. These may be restricted to attitudes toward divorce and related issues (Amato and Booth, 1991; Sieben and Verbakel, 2013), but it could easily translate into a broader liberal outlook on sociocultural political issues, resulting in higher tolerance toward out-groups and more progressive corresponding views, that lead to more leftist political orientations.

Political socialization and left-right self-identification

We focus on left-right political ideology as the outcome variable, measured by self-identification with a position on the left-right scale. Recent studies are increasingly understanding political socialization processes in terms of the transmission of left-right self-identification (Corbetta et al., 2013; Rico and Jennings, 2016; Durmuşoglu et al., 2022; Van Ditmars, 2023), due to the salience of this dimension in Western Europe and the heuristic advantage of ideology as a cue for intergenerational transmission, especially in multiparty systems (Westholm and Niemi, 1992; Ventura, 2001). The terms “left” and “right” are the most used term to distinguish political ideologies, not only for political parties, but also for citizens. Left-right self-placement is a widely used summary concept of individuals' political ideology, considered as one of the main ways to describe individuals politically and a key predictor of party preference in Western Europe (Mair, 2007; Lachat, 2008).

This measure captures individuals' political self-identification and positions on socioeconomic as well as the sociocultural issues (Lachat, 2018) in one single measure, and is therefore a suited dependent variable for this study. The mechanisms that we identify in our theoretical framework relate to both socioeconomic and sociocultural political attitudes, as well as the intergenerational transmission of parental ideology and political self-identification more generally. Notably, the meaning of left and right can change over time (Bauer et al., 2017), which is rather an advantage in the study of political socialization processes, because this reduces the importance of specific issue salience that is more subject to political period and context effects (Van Ditmars, 2023). A more practical advantage of using this measure is that it can be well compared across the datasets used in this study, as the question wording is almost identical. This allows for an adequate comparison of the two analyses. Given the rarity of datasets including information about individuals' childhood family structure and their political attitudes, this is an important advantage.

Data and methods

We employ two valuable datasets that include information on respondent's political ideology, parental divorce, and key independent variables that allow us to test our theoretical framework.

First, we use the European Values Study 2008: a large-scale, pan-European study on adults' values collected in the period 2008–2010 (EVS, 2011). We use an analytic sample of 17'419 respondents from 19 countries.4 This dataset is collected using representative stratified random samples of the adult populations from age 18 years, using face-to-face interviews with a standardized questionnaire. Post-communist countries are excluded from the analysis, as left and right have a different meaning in post-communist Europe (Tavits and Letki, 2009), and the left–right self-placement scale is therefore used differently (Pop-Eleches and Tucker, 2010). Malta is also excluded, as divorce was not legal there in the year of the survey.

Second, we employ the Swiss Household Panel (SHP), waves 1999–2020 (SHP Group, 2022). This is a longitudinal survey interviewing all household members of a random sample of private households in Switzerland since 1999 stratified by the seven major statistical regions of Switzerland (Tillmann et al., 2022). The questionnaire is conducted using computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI), or alternatively using computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) or computer-assisted web interviewing (CAWI). The SHP is a particularly valuable dataset for our research question as it includes observations on individuals from the same household, resulting in two-generational data. As such, we do not only have direct observations of respondent's political ideology and their parental civil status and co-residency, but also of parental political ideology and other relevant traits, because parents and their children are both included in the surveys.

The construction of a datafile in which respondents' survey responses are linked to those of their parents, allows us to observe respondents and their parents jointly. The data includes direct observations of the family structure as well as political ideology of parents and children, which makes it very suitable to understand the consequences of parental separation for the political socialization process. Even though respondents are included from age 14 years onward, we include respondents from age 18 years, for adequate comparison with the EVS in which that is the minimum respondent age. Our analyses rely on an analytic sample of 2,984 respondents. Even though the SHP provides a representative sample of the Swiss population, our analytic sample is comprised only by respondents of whom the parents are also included in the study. Therefore, we control for sociodemographic variables including gender, age, socioeconomic status. The usage of direct observations of respondents and their parents, and the time span of the SHP implies that our analytic sample is relatively young. These respondents were most often initially included in the panel as children of the reference person for the survey (living at home with their parents) and then become old enough to participate in the survey and remain in the panel also after moving out of the parental home. As 96% of respondents of the two-generational analytic sample are younger than 35 years, we reduce the analysis to this age group to avoid impact of older outliers. Therefore, the inferences drawn from this analysis are limited to young adults.

Switzerland is a relevant case to study the political effects of divorce more closely next to our pan-European analysis. Divorce was legalized throughout Switzerland already in 1875 (Calot, 1998) but until the mid-1960s, the divorce rate was rather low. Since then, Switzerland's divorce rate has been rapidly rising, in line with trends across most OECD countries, and the crude divorce rate is very close to the OECD and EU averages, albeit slightly higher (OECD, 2022). After divorce, most mothers were awarded custody of the children up until 2014, while since then joint custody is the norm. Most single-parent households in Switzerland consist of mothers (85%) and this groups is two to three times as likely to experience poverty compared to the average population (Amacker et al., 2015). Switzerland has known a relatively late development of the welfare state, particularly regarding family policy (Baghdadi, 2010; Häusermann and Kübler, 2010). As a result, single, divorced and separated mothers are more affected by poverty than widowed mothers due to a lack of social benefits and high childcare costs as a result of low family policy expenditure in Switzerland (Baghdadi, 2010).

Variables and models

We perform two sets of separate analyses using the two datasets, using similar dependent and independent variables to ensure comparability. We use these two respective datasets to estimate the relation between parental separation and adult political ideology, paying particular attention to the potential problem of self-selection in divorce. Parents who separate are likely different from those who do not, therefore we control for differences between these groups. Religiosity is an important factor in attitudes toward divorce (Gelissen, 2003), and is also related to political conservatism and right-leaning political positions (Jost et al., 2009; Van der Brug, 2010). Therefore, religious socialization is included in the EVS analyses and mother's religiosity during childhood in the SHP analyses. Importantly, the SHP analyses include direct observations of the parental ideology. This way, the parent-child transmission of political ideology is estimated separately. Leaving these covariates out of the model would most likely lead to inflated effects of the coefficient for parental separation.

First, we estimate multi-level models with the EVS 2008 data, accounting for the structure of the data of respondents nested in countries (Snijders and Bosker, 1999). The dependent variable is left–right self-placement, measured on a 10-point scale (from 1 to 10, i.e., without a mid-point). Parental divorce, the main independent variable, is measured through a retrospective question whether respondents have ever experienced the divorce of their parents (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Economic deprivation during childhood is measured with a dummy variable that indicates whether parents had problems making ends meet when the respondent was 14 years old. Single-mother socialization is measured using a dummy variable indicating whether children lived only with the mother at age 14. Religious socialization is measured by asking how often respondents attended religious services when they were 12 years old apart from weddings, funerals and christenings (recoded into a dummy where 0=few times a year or less; 1 = once a month or more). Information on parental level of education and SES are also included because they can impact the probability to have experienced parental divorce and/or political leanings. The information is included about respondent's father if they lived with both parents or only the father, and about the mother if they lived with only the mother. Parental SES is included by using the SIOPS score indicating the occupational prestige (Treiman, 1977) of the father [mother] when the respondent was 14 years old. The SIOPS score in the EVS is obtained by recoding the ISCO88 two digits score using the recoding scheme as provided by Ganzeboom and Treiman (1996). Parental education is measured using one-digit ISCED codes of the father's [mother's] highest level of education completed (recoded into low/medium/high). Several individual control variables are used in the analyses: age, gender, educational level (ISCED, recoded into low/medium/high), and marital status.

Second, we analyse the SHP data using a similar analytic strategy to the one applied to the EVS data, with one large additional advantage: the inclusion of the parental political ideology. We estimate regular OLS regression models, using for each respondent the most recent wave in which they participated out of all available waves (1999–2020). As multiple children per family are included in the data, the standard errors are clustered per each mother in the sample (i.e., at the household level).

The main dependent variable is left-right political ideology, measured on a scale from 0 to 10. The main independent variable, separation/divorce of parents, is constructed as follows: a dummy indicates whether the respondent's parents are married and/or live together in the same household (0); or parents are separated/divorced or live apart (1), over all waves in which respondents have participated in the survey and the indicators for their parents' partner status and living arrangements are available, which are directly observed from their survey responses. Although the nature of the data in principle means that we can observe parental divorce occurring during the panel, for most respondents the partner status of the parents is stable over the period that they are included in the household panel (90% of our analytic sample). Parental divorce observed during the panel is therefore not included in our analyses. Importantly, it should be noted that these parental divorces occur when the respondents are already (young) adults and the family political socialization process, that is of main interest for this paper, for most individuals ends around this age. Even if there would be enough parental divorces observed during the panel, an individual fixed-effects approach in which the “causal” effect of parental divorce would be estimated, is not suitable to test our theoretical expectations, as this would require before and after measures of respondent's political ideology. This is not possible for parental divorce during childhood because political attitudes are not measured for children, nor would it be suitable to test our expectations, because our interest is in the altered political socialization process of children of separated parents. For these reasons, and to ensure comparability with the EVS analyses, in creating our parental divorce variable we consider as having experienced divorced/separated those respondents whose parents were divorced in the first wave of observation and remained divorced through the following waves.

Our key independent variables are directly observed from the mother during the childhood of the respondents (prior to age 18 years), including earlier waves prior to respondents joining the panel, but when the mother was already included. We rely on information of the mother (and not the father) because most children end up with the mother after a parental separation, and fathers who separated from their children's mother are underrepresented in the sample as the non-resident parent is more likely to show panel attrition after a separation. Economic deprivation during childhood is measured with a dummy variable that indicates whether the mother ever had arrears in paying household bills. Single-mother socialization is indicated by a dummy variable measuring whether the respondent ever lived only with the mother during childhood. Mother's political ideology is included by taking the mode (most observed value) of this variable for all available waves prior to respondent's age 18 years. It is the same left-right variable as for respondents (0–10 scale), recoded into the categories left (0–4), center (5), right (6–10), and not available. Mother's religiosity is indicated by a categorical variable indicating the highest frequency of mother's church attendance observed prior to respondent's age 18 years. It has the following categories: a few times a year or less; indicates once a month or up; and a category for whom this information is not available.

Control variables are included for mother's education (low, middle, high), respondents' civil status, educational level (low, middle, high), the prestige score (low, middle, high) of the parent's or the own occupation5 (Treiman, 1977), gender, and age.

Results

Descriptive analyses

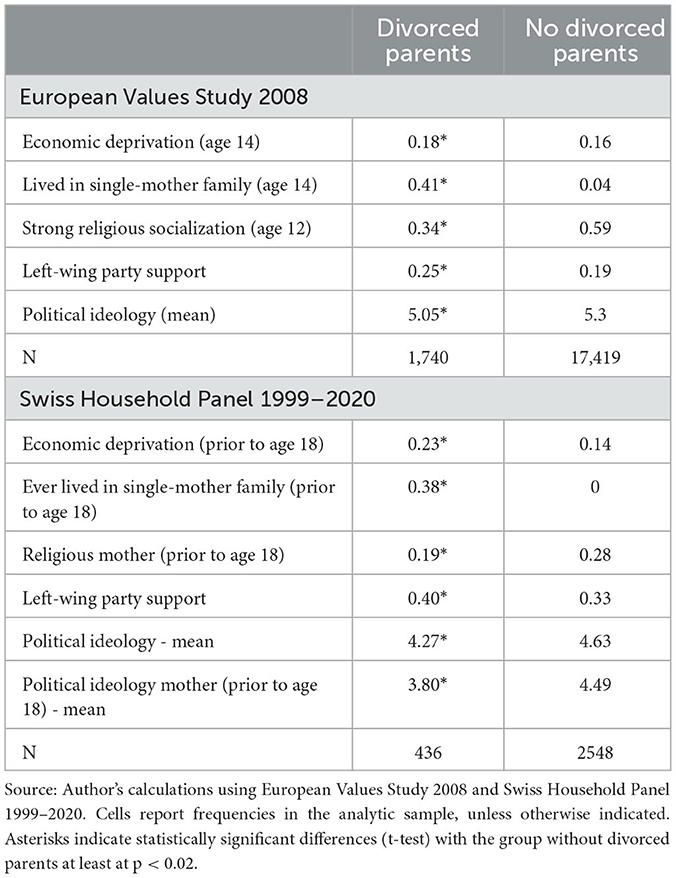

We first present descriptive results on relevant differences between respondents with and without divorced parents. Table 1 displays descriptive statistics of the EVS and SHP data, in which respectively 10 and 14.6% of respondents have experienced parental divorce. The figures indicate that there are statistically significant differences on the variables of key interests between individuals who have experienced parental divorce and those who did not, providing initial support for our theoretical expectations.

The figures in Table 1 indicate that in both analytic samples, respondents who have experienced parental divorce, also display higher rates of economic deprivation and living in single-mother households during childhood. The data also shows the self-selection into parental divorce by less religious households, as indicated by mother's lower church attendance during childhood. Importantly, offspring of divorced parents take significantly more left-wing political positions and are more likely to support left-wing parties. In the SHP we also have information about the parental political orientation: the difference in mean political ideology between divorced and non-divorced mothers is relatively large (mean difference of 0.69, p = 0.013). This is of a similar magnitude as the size of the gender gap – i.e., the difference between men and women in political ideology – in the Swiss sample, that is comparatively also quite large (0.67 among respondents, and 0.49 among mothers).

The results of additional statistical tests are also in line with expectations. In the EVS, respondents who have experienced economic deprivation at age 14, as well as those who lived only with the mother at that time, hold more left-wing positions than those without those experiences (differences in mean of 0.18 and 0.25, respectively, p = 0.000). Respondents with more intense religious socialization– who are less likely to have experienced parental divorce – hold less leftist positions (difference of 0.24, p = 0.000). These differences are similar in size to the gender gap in political ideology which amounts to 0.24 in the EVS sample (p = 0.000). In the SHP, the results are similar: respondents who ever lived in a single-mother household prior to age 18 years hold more leftist positions (difference in mean of 0.6, p = 0.000), while those who grew up with more religious mothers are more right-wing (difference of −0.27, p = 0.004). However, respondents do not show statistically significant differences in left-right positions by economic deprivation during youth (difference of −0.077, p = 0.5).

These descriptive results provide initial support for the theoretical expectations: children of divorced parents display more left-wing political preferences compared to those who did not experience parental divorce, which might be explained by experiences of economic deprivation (EVS only) and single-mother socialization. These results also show that it is important to control for self-selection into divorce by less religious and more politically progressive individuals, which is what we turn to in the subsequent multivariate analyses.

Multivariate analyses

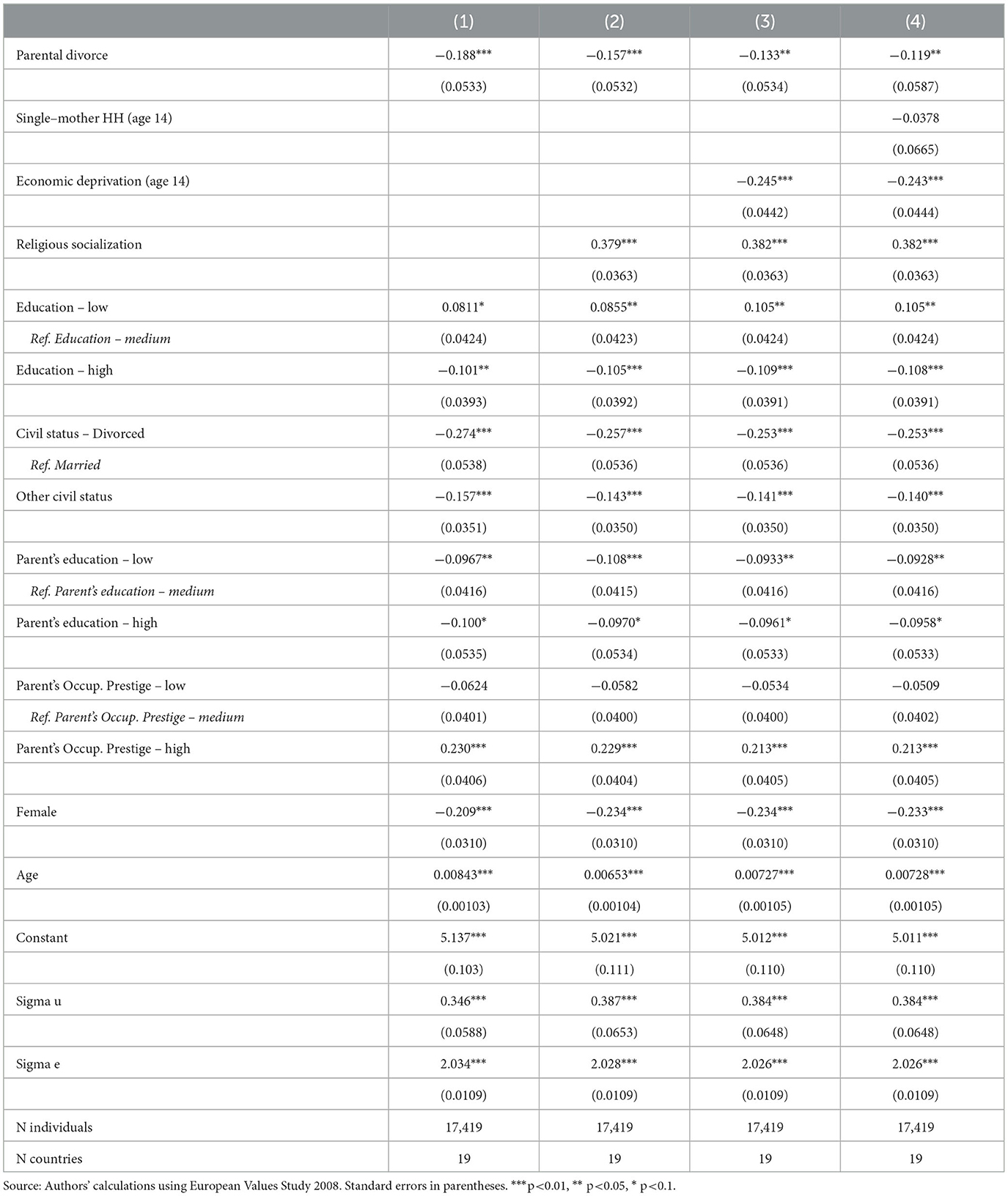

The results of the multilevel models using the EVS 2008, estimating the effect of the parental separation on left–right ideology, are presented in Table 2. The independent variables of key interest are stepwise added to the models. Negative coefficients indicate left-leaning effects, while positive coefficients indicate right-leaning effects: higher values in the dependent variable refer to more right-wing positions.

The first model shows a statistically and substantially significant left-wing coefficient for parental divorce of −0.19, indicating a mean difference of 0.2 on the left-right scale between respondents with and without divorced parents. Substantively, this difference is similar to the gender gap in political ideology (b = −0.21). When the independent variables of main interest are stepwise added in the next models, this reduces the coefficient for parental divorce, indicating that these factors contribute to the relation between parental divorce and left-wing political positions. In the second model, religious socialization is added, which reduces the coefficient for parental divorce to become smaller than the gender gap. The coefficient in the first model was thus slightly inflated due to the self-selection of non-religious individuals in parental divorce. In the third model, economic deprivation during childhood is added, which reduces the coefficient of parental divorce during childhood to −0.13, while economic deprivation predicts leftist positions even more strongly (b = −0.25). This indicates that part of the left-wing effect of parental divorce runs through economic deprivation, which predicts more left-leaning positions.

In the last model, living in a single-mother household during childhood is added, which does not significantly predict respondents' political ideology, when parental divorce is also included in the model, of which the coefficient remains similar with a magnitude of −0.12. Parental separation is thus a stronger predictor of respondent's political ideology, which could be because this variable is more adequately capturing the socialization experience that follows parental separation for all respondents, as the living arrangements variable is measured only for one point in time (age 14 years). Importantly, and in line with our expectations, throughout all models religious socialization predicts more right-leaning political positions, while higher educated respondents hold more left-leaning positions, and divorced respondents also lean more to the left.

Although this pan-European analysis indicates that parental divorce is associated with more left-wing political positions in adult children, it cannot be concluded that this finding is not due to self-selection effects. Children from divorced parents might simply be more left-wing to begin with, as less religious and more left-leaning individuals are more likely to get divorced, and parents pass on their political left-right positions to their children (Van Ditmars, 2023). Religious socialization was included in the previous models as it relates to both attitudes toward divorce and political ideology, but as this is not adequate to fully predict parental political ideology, and the political socialization that respondents have received from their parents. The indicator for living only with the mother during a moment in childhood did not have a separate effect on political ideology in the foregoing analyses, but this only partially captures the socialization experience as this was measured only at one retrospective timepoint and the political views of the mother are unknown. Therefore, the next analyses using the Swiss household data that include the mother's political views and more precise information about residency, will shed more light on these questions.

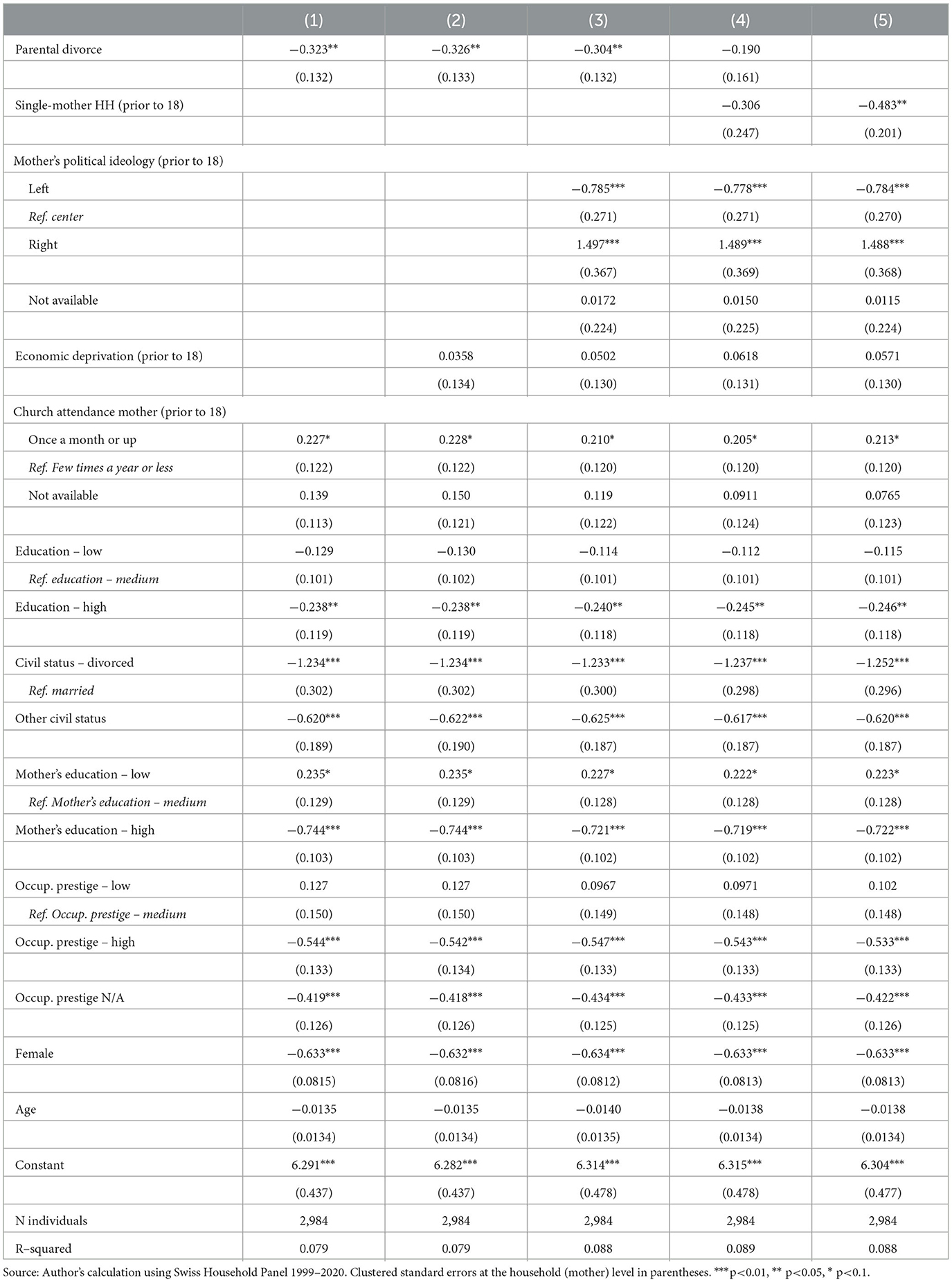

Table 3 presents the results of the regression models using the SHP in which left-right ideology is regressed on parental separation. Economic deprivation, the mother's political ideology, and living in a single-mother household are included stepwise in the models. The first model shows that when controlling for sociodemographic factors and mother's church attendance during childhood, offspring of separated parents display more left-wing political positions, with a difference of 0.32 on the left-right scale. In the second model, economic deprivation during childhood is added, which does not reduce the coefficient for parental divorce. Economic deprivation does not predict political positions, as the coefficient is not statistically significant and of very small magnitude – in line with the descriptive statistics presented earlier.

In the third model, mother's political ideology during youth is added. In line with previous studies, it has a strong and relatively large predictive effect on the adult child's political ideology (with coefficients of −0.79 and 1.5 for leftist and rightist mothers, respectively). The inclusion of this variable reduces the coefficient for parental divorce slightly to −0.30. Substantively, the size of the coefficient of parental divorce in this model is about half the size of the gender gap observed in this sample. In the fourth model, adding living in a single-mother household during childhood reduces the size and statistical significance of the parental divorce coefficient. As in the EVS models, the single-mother household variable does not have an additional effect on political ideology in itself, even though in the descriptive statistics this variable did show relevant political differences between the two groups. In fact, when in the final model we exclude the coefficient for parental separation, the coefficient for single-mother household during youth is strong and statistically significant, at b = −0.48. The two variables thus canceled each other out in model 4, while model 5 indicates the relevance of living in a single-mother household.

The results of the multivariate EVS and SHP both indicate differences in left-right positioning of respondents by the experience of parental divorce, controlling for self-selection into parental divorce. We interpret these analyses as indicative of the relation between parental divorce and more leftist political positions through altered political socialization experiences, and complementary to the intergenerational transmission of parental ideology. While in the EVS analysis, childhood economic deprivation seems to be part of the underlying mechanism in the relation between parental separation and political ideology, the SHP analysis shows no indication thereof, and underlines the importance of the experience of living in a single-mother household during childhood.

Conclusion

This paper has studied the consequences of parental divorce or separation for the political socialization process in shaping offspring's political ideology, arguing that parental separation predicts more leftist political positions in adulthood through experiences of economic deprivation and single-mother socialization. The analyses using the European Values Study and the Swiss Household Panel consistently show that adult children of separated parents tend to hold more left-wing political views than those without separated parents, and these differences remain when controlling for self-selection into parental divorce by more progressive and less religious families. Moreover, benefiting from the two-generational information in the SHP we show that parental separation and the mother's political ideology are both strong predictors of their adult offspring's political ideology. Our findings thus suggest that family structure results in formative experiences that are relevant to the political socialization process during the impressionable years, next to the intergenerational transmission of political views.

We theorized that two common consequences of union dissolution, economic deprivation and single-mother socialization, can explain the relation between parental divorce and left-wing political views. Across the two different analyses, we find empirical support for both these mechanisms. In the pan-European analyses with the EVS, we find strong indications that economic deprivation explains parts of the political differences predicted by parental divorce. In the Swiss analyses using the SHP, we did not find such support. While in the descriptive analyses respondents with divorced parents did more often experience economic deprivation during childhood, it does not predict differences in political positions. It might be that even when Swiss households have arrears in paying their bills (the measurement in the SHP), this does not importantly impact their living standard, explaining why this does not predict political positioning. However, participants in severe economic distress following a divorce are also more likely to show panel attrition and will be therefore underrepresented in analytic sample, while this issue does not arise when using retrospective information as in the EVS. Regarding single-mother socialization, both descriptive analyses indicated significant differences in political positioning by the experience of having lived in a single-mother household during childhood. However, in the EVS multivariate analyses it did not significantly predict respondent's ideology, nor did it affect the coefficient for parental divorce. In the SHP analyses on the other hand, the relation between parental divorce and political ideology runs mainly through the experience of single-mother socialization. This difference could be partially due to measurement issues because in the EVS, due to the retrospective measurement about one specific point in time (age 14 years), this variable does not capture the household composition of those who experienced parental divorce after that age.

Importantly, the SHP analyses indicated that mother's ideological self-placement during childhood significantly predicts adults' political positioning during adulthood, apart from the experience of living in a single-mother household. Our analyses also indicated that most respondents who experienced parental divorce ended up in single-mother households, and that divorced mothers take on average significantly more left-wing positions. Children growing up in single-mother households are thus on average more exposed to parental left-wing political socialization – apart from the fact that women take already on average more left-wing positions than men. The intergenerational transmission of political ideology is thus also interrelated with the political effect of parental divorce, and these factors are demonstrated to jointly predict offspring's political ideology in adulthood. By including the mother's ideological positions during childhood, we control for an important mechanism of self-selection of more politically progressive mothers into divorce. Next to that, as in the EVS analyses, we also control for religious socialization during childhood indicated by the mother's frequency of church attendance.

While this study is not without limitations, we are confident in having provided valuable first insights regarding the relation between parental separation, political socialization, and political self-identification in adulthood, with broader European analyses and more in-depth Swiss analyses using household data. The limitations of the study provide avenues for further research on the political implications of parental divorce in particular, and of family structure more generally. Additional research is needed to better understand how growing up in single-parent households affects individuals' political development, especially given the limited support for this mechanism in the EVS analysis. A challenge is thereby that retrospective information (as in the EVS) rarely provides the full range of information required, while the use of prospective information (as in the SHP) implies limitations of panel attrition, especially of households going through personal and/or financial turmoil.

Despite our efforts to control for self-selection into parental divorce, the SHP analytic sample is limited to respondents from households of which mothers and adult children are jointly included in the panel study and is therefore not a representative sample of the Swiss population. Therefore, we included socio-demographic controls as well, but one should remain careful generalizing those results to other samples and contexts, and the inferences drawn from this analysis are limited to young adults. Moreover, our analyses have been not able to directly study the impact of the theorized mechanism of witnessing parents breaking social norms. This is considered part of the experience of single-mother socialization, but is not directly captured by residency arrangements. Not all individuals will feel equally socially penalized by living in a non-standard family structure, as this will depend on a myriad of factors related to the social milieu, specific family context, as well as the wider societal context. More research is needed to better understand to what extent the norm-breaking behavior, to which divorce still belongs in many societies and subcultures, and certainly did in multiple cohorts in our study, contributes to the consequences of parental divorce for political socialization processes. If that is indeed a relevant factor, in younger cohorts where parental divorce is becoming increasingly common, this part of the political effects of parental divorce might fade away over time. Whether parental divorce will continue to be relevant in the political socialization process of younger generations in which divorce is more common, will depend on how they are socially and economically affected by this impactful life event.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: EVS, 2011. European Values Study Integrated File 2008 (EVS 2008). Cologne: GESIS Data Archive. ZA4800. ZA4804 Data file Version 3.0.0. https://search.gesis.org/research_data/ZA4800?doi=10.4232/1.13841. SHP Group, 2022. Living in Switzerland Waves 1–22 + Beta version wave 23 + Covid 19 data. Lausanne: FORS - Centre de compétences suisse en sciences sociales. Financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation, distributed by FORS, version 5.2.0. https://doi.org/10.48573/vaxa-3w42.

Author contributions

Both authors have contributed substantially and intellectually to the article, including its theoretical framework, research design, and interpretation of the results. MvD is lead author.

Funding

The publication of this article has been funded by an Open Access Grant of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of the University of Lucerne, Lucerne, Switzerland.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marieke Voorpostel, the editor and reviewers, as well as participants of the Swiss Political Science Association Annual Congress 2021 and of the Seminar in Politics and Society at Collegio Carlo Alberto for their helpful comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In this article we use the terms separation and divorce interchangeably.

2. ^The effects commented in the text are averages. Recent studies focus on the heterogeneous effect of parental separation that can actually be positive for some children, in particular in cases of separation that end abusive and conflictive relationships (Härkönen et al., 2017).

3. ^Of course, growing up in a single-mother family does not mean that the child is not exposed to socializing influences of the father as well. In fact, it could be even the case that the child sees the father as the political role model, even though they spend less time with him. In the political socialization literature, there is however no consensus regarding the gender dynamics that underlie the intergenerational transmission of political attitudes (Fitzgerald and Bacovsky, 2022; Van Ditmars, 2023).

4. ^The following 19 countries are included in the analysis: Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Great Britain.

5. ^For young respondents that are often still in school (under age 23 years), the prestige score of the parents is used, for the other respondents their own prestige score. The prestige score of the father's occupation is used for respondents from traditional two-parent households, while the prestige score of the mother's occupation is used for respondents with separated parents.

References

Abendschön, S., and Steinmetz, S. (2014). The gender gap in voting revisited: women's party preferences in a european context. Soc. Pol. Int. Stu. Gender State Soc., 21, 315–344. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxu009

Amacker, M., Funke, S., and Wenger, N. (2015). Alleinerziehende und Armut in der Schweiz. Bern: Interdisziplinäres Zentrum für Geschlechterforschung IZFG, Universität Bern.

Amato, P. R. (2000). the consequences of divorce for adults and children. J. Marriage Family 62, 1269–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01269.x

Amato, P. R., and Booth, A. (1991). The consequences of divorce for attitudes toward divorce and gender roles. J. Family Issues 12, 306–322. doi: 10.1177/019251391012003004

Amato, P. R., and Keith, B. (1991). Parental divorce and adult well-being: a meta-analysis. J. Marriage Family 53, 43–58. doi: 10.2307/353132

Andersson, G., Thomson, E., and Duntava, A. (2017). Life-table representations of family dynamics in the 21st century. Demograph. Res. 37, 1081–1230. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2017.37.35

Andress, H-. J., Borgloh, B., Brockel, M., Giesselmann, M., and Hummelsheim, D. (2006). The economic consequences of partnership dissolution–a comparative analysis of panel studies from Belgium, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, and Sweden. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 22, 533–560. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcl012

Baghdadi, N. (2010). Care-Work Arrangements of Parents in the Context of Family Policies and Extra-familial Childcare Provision in Switzerland. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

Bauer, P. C., Barberá, P., Ackermann, K., and Venetz, A. (2017). Is the left-right scale a valid measure of ideology? Polit. Behav. 39, 553–583. doi: 10.1007/s11109-016-9368–2

Beck, P. A., and Jennings, M. K. (1975). Parents as ‘Middlepersons' in political socialization. J. Politics 37, 83–107. doi: 10.2307/2128892

Bernardi, F., and Radl, J. (2014). The long-term consequences of parental divorce for children's educational attainment. Demog. Res. 30, 1653–1680. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2014.30.61

Bhrolcháin, M. N., Chappell, R., Diamond, I., and Jameson, C. (2000). Parental divorce and outcomes for children: evidence and interpretation. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 16, 67–91. doi: 10.1093/esr/16.1.67

Calot, G. (1998). Two Centuries of Swiss Demographic History. Graphic Album of the 1860-2050 Period. Neuchâtel: Swiss Federal Statistical Office.

Corbetta, P., Tuorto, D., and Cavazza, N. (2013). Parents and Children in the Political Socialization Process: Changes in Italy Over Thirty-Five Years. Growing into politics. Context and timing of political socialization. Colchester: ECPR Press, 11–29.

Davies, J. C. (1965). The family's role in political socialization. Annal. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 361, 10–19. doi: 10.1177/000271626536100102

Dehdari, S. H., Lindgren, K-. O., Oskarsson, S., and Vernby, K. (2022). The ex-factor: examining the gendered effect of divorce on voter turnout. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 116, 1293–1308. doi: 10.1017/S0003055422000144

Dolan, K. (1995). Attitudes, behaviors, and the influence of the family: a reexamination of the role of family structure. Polit. Behav. 17, 251–264. doi: 10.1007/BF01498596

Durmuşoglu, L. R., Lange, d. e., Kuhn, S. L. T., and van der Brug, W. (2022). The intergenerational transmission of party preferences in multiparty contexts: examining parental socialization processes in the Netherlands. Political Psychol. Early View. 11, 12861. doi: 10.1111/pops.12861

Eurostat (2022). Eurostat Divorce Indicator DEMO_NDIVIND. Eurostat, The Statistical Office of the European Union.

EVS (2011). European Values Study Integrated File 2008. (EVS 2008). Cologne: GESIS Data Archive. ZA4800, ZA4804. Data file Version 3.0.0.

Fitzgerald, J., and Bacovsky, P. (2022). Young citizens' party support: the “when” and “who” of political influence within families. Polit. Stu. Online First. 1, 323217221133643. doi: 10.1177/00323217221133643

Flouri, E. (2004). Parental background and political attitudes in British adults. J. Family Econ. Issues 25, 245–254. doi: 10.1023/B:JEEI.0000023640.19330.70

Ganzeboom, H. B., and Treiman, D. J. (1996). Internationally comparable measures of occupational status for the 1988 international standard classification of occupations. Soc. Sci. Res. 25, 201–239. doi: 10.1006/ssre.1996.0010

Gelissen, J. (2003). “Cross-national differences in public consent to divorce: effects of cultural, structural and compositional factors,” in The Cultural Diversity of European Unity. Findings, explanations and Reflections From the European Values Study, eds W. Arts, J. Hagenaars, and L. Halman (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill N.V), 339–370.

Härkönen, J., Bernardi, F., and Boertien, D. (2017). Family dynamics and child outcomes: an overview of research and open questions. Eur. J. Pop. 33, 163–184. doi: 10.1007/s10680-017-9424-6

Hatemi, P. K., and Ojeda, C. (2021). The role of child perception and motivation in political socialization. Br. J. Poli. Sci. 51, 1097–1118. doi: 10.1017/S0007123419000516

Häusermann, S., and Kübler, D. (2010). Policy frames and coalition dynamics in the recent reforms of Swiss family policy. German Policy Stu. 6, 163–194.

Hener, T., Rainer, H., and Siedler, T. (2016). Political socialization in flux?: linking family non-intactness during childhood to adult civic engagement. J. Royal Stat. Soc. 179, 633–656. doi: 10.1111/rssa.12131

Hogendoorn, B., Leopold, T., and Bol, T. (2020). Divorce and diverging poverty rates: a risk-and-vulnerability approach. J. Marriage Family 82, 1089–1109. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12629

Inglehart, R., and Norris, P. (2000). The developmental theory of the gender gap: women's and men's voting behavior in global perspective. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 21, 441–463. doi: 10.1177/0192512100214007

Jennings, M. K., and Niemi, R. G. (1968). The transmission of political values from parent to child. The Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 62, 169–184. doi: 10.2307/1953332

Jennings, M. K., and Niemi, R. G. (1971). The division of political labor between mothers and fathers. Am. Poli. Sci. Rev. 65, 69–82. doi: 10.2307/1955044

Jennings, M. K., and Niemi, R. G. (1974). The Political Character of Adolescence. The Influence of Family and Schools. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jennings, M. K., Stoker, L., and Bowers, J. (2009). Politics across generations: family transmission reexamined. J. Polit. 71, 782–799. doi: 10.1017/S0022381609090719

Jost, J. T., Federico, C. M., and Napier, J. L. (2009). Political ideology: its structure, functions, and elective affinities. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 60, 307–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163600

Kalmijn, M. (2013). Long-term effects of divorce on parent-child relationships: within-family comparisons of fathers and mothers. Eur. Sociolog. Rev. 29, 888–898. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcs066

Koster, T., Poortman, A. R., van der Lippe, T., and Kleingeld, P. (2021). Parenting in postdivorce families: the influence of residence, repartnering, and gender. J. Marriage Family 83, 498–515. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12740

Kuhn, T., Lancee, B., and Sarrasin, O. (2021). Growing up as a european? Parental socialization and the educational divide in euroskepticism. Polit. Psychol. 42, 957–975. doi: 10.1111/pops.12728

Lachat, R. (2008). The impact of party polarization on ideological voting. Elect. Stu. 27, 687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2008.06.002

Lachat, R. (2018). Which way from left to right? On the relation between voters' issue preferences and left–right orientation in West European democracies. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 39, 419–435. doi: 10.1177/0192512117692644

Mair, P. (2007). “Left-Right Orientations,” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior, eds R.J. Dalton and H.D. Klingemann (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 206–222.

McLanahan, S., Tach, L., and Schneider, D. (2013). The causal effects of father absence. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 39, 399–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145704

OECD (2018). OECD Family Database. SF1, 3. Further Information on the Living Arrangements of Children.

Percheron, A., and Jennings, M. K. (1981). Political continuities in french families: a new perspective on an old controversy. Comp. Poli. 13, 421–436. doi: 10.2307/421719

Pop-Eleches, G., and Tucker, J. (2010). After the party: legacies and left-right distinctions in post-communist countries. SSRN 1, 1670127. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1670127

Rico, G., and Jennings, M. K. (2016). The formation of left-right identification: pathways and correlates of parental influence. Polit. Psychol. 37, 237–252. doi: 10.1111/pops.12243

Sandell, J., and Plutzer, E. (2005). Families, divorce and voter turnout in the US. Polit. Behav. 27, 133–162. doi: 10.1007/s11109-005-3341-9

Sayer, L. C. (2006). “Economic Aspects of Divorce and Relationship Dissolution.,” in Handbook of Divorce and Relationship Dissolution, eds M.A. Fine and J.H. Harvey (New Jersey, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.), 385–406.

Shorrocks, R. (2018). Cohort change in political gender gaps in europe and canada: the role of modernization. Politics Soc. 46, 135–175. doi: 10.1177/0032329217751688

SHP Group (2022). Living in Switzerland Waves 1-22 + Beta Version Wave 23 + COVID 19 Data. Lausanne: FORS.

Sieben, I., and Verbakel, E. (2013). Permissiveness toward divorce: the influence of divorce experiences in three social contexts. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 29, 1175–1188. doi: 10.1093/esr/jct008

Sigel, R. (1965). Assumptions about the learning of political values. Annal. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 361, 1–9. doi: 10.1177/000271626536100101

Sigle-Rushton, W., and McLanahan, S. (2004). “Father absence and child well-being: a critical review,” in The Future of the Family, eds D. P. Moynihan and T.M. Smeeding (New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation), 116–155.

Snijders, T., and Bosker, R. (1999). Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Analysis. London: Sage.

Tavits, M., and Letki, N. (2009). When left is right: party ideology and policy in post-communist Europe. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 103, 555–569. doi: 10.1017/S0003055409990220

Tillmann, R., Voorpostel, M., Antal, E., Dasoki, N., Klaas, H., Kuhn, U., et al. (2022). The swiss household panel (SHP). Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 242, 403–420. doi: 10.1515/jbnst-2021-0039

Treiman, D. J. (1977). Occupational Prestige in Comparative Perspective. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Van der Brug, W. (2010). Structural and ideological voting in age cohorts. West Eur. Politics, 33, 586–607. doi: 10.1080/01402381003654593

Van Ditmars, M. M. (2023). Political socialization, political gender gaps and the intergenerational transmission of left-right ideology. Eur. J. Poli. Res. 62, 3–24. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12517

Ventura, R. (2001). Family political socialization in multiparty systems. Comp. Polit. Stu. 34, 666–691. doi: 10.1177/0010414001034006004

Voorpostel, M., and Coffé, H. (2015). The effect of parental separation on young adults' political and civic participation. Soc. Indic. Res. 124, 295–316. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0770-z

Keywords: political socialization, parental separation, political ideology, single-mother socialization, parental divorce

Citation: Van Ditmars MM and Bernardi F (2023) Political socialization, parental separation, and political ideology in adulthood. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1089671. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1089671

Received: 04 November 2022; Accepted: 19 May 2023;

Published: 16 June 2023.

Edited by:

Alina Vranceanu, Pompeu Fabra University, SpainReviewed by:

Aleš Kudrnáč, Umeå University, SwedenRidwan Raji, Zayed University, United Arab Emirates

Copyright © 2023 Van Ditmars and Bernardi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mathilde M. van Ditmars, bWF0aGlsZGUudmFuZGl0bWFyc0B1bmlsdS5jaA==

Mathilde M. van Ditmars

Mathilde M. van Ditmars Fabrizio Bernardi2

Fabrizio Bernardi2