94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 18 May 2023

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1032470

This article is part of the Research TopicCrisis, Contention, and EuroscepticismView all 7 articles

Hungary has become the leader of democratic backsliding within Europe, with Prime Minister Viktor Orbán turning into the staunchest critic of the EU, despite a consistent support for the European project among the wider public and Hungary being a net benefiter of EU membership. Using a systematic analysis of all speeches, statements and interviews of the PM for his three consecutive governments 2010–2022, I claim the radicalization of this Eurosceptic discourse is a direct consequence of a continuous populist performance of crisis that demands the creation of images of friends and foes to unite and mobilize people. Orbán relies on discursive processes of othering to construct to his liking both “the good people” and its enemies, who are to be blamed for the crises. Anybody can become an enemy in the various crises that follow each other. At the same time, discursive conceptions of Europe vs. the EU remain in the center of the discourse to establish Hungary's European belonging as well as opposition to EU for policies that allegedly people reject. While the economic crisis pits an economic “us” against the former socialist political elite, foreign capital, and the EU and IMF that are all blamed for Hungary's near-bankruptcy situation. The refugee crisis redefines both “us” and “others”, the “self” is distinguished using ethno-linguistic criteria and identitarian Christianity to signal the cultural distance from the Muslim migrant “other” as well as multicultural EU. The pandemic crisis is performed only to further exacerbate the conflict between the illiberal “self” and the liberal “others”, where supranational EU, promoting multiculturalism, gender ideology or neoliberal policies not only threatens the very existence of traditional-national lifestyles but endangers the people themselves. With each crisis performed, newer and newer conflict lines between various “European self's” and “threatening EU” are identified, each adding to the radicalization of Orbán's discourse. The demonization of the EU and the pretext of saving Europe using these false discursive constructs enables Orbán strengthen his grip of power and drift to authoritarianism.

Over the past decade, Hungary has become the leader of anti-democratic and anti-European developments within the European Union. Ever since Prime Minister Viktor Orbán returned to power in 2010 (he previously held office from 1998 to 2002), his priority has been the building of an “illiberal democracy” (for details see Tóth, 2014), a regime to denounce liberal principles to serve the interest of the people and the nation. This has meant a total transformation of the country's political regime, economy, and also national community. Calling his 2010 landslide electoral win a “ballot revolution” against the post-communist Hungarian status-quo, Orbán quickly and completely dismantled democratic checks and balances in a country that used to be a poster-child for post-communist democratization and consolidated politics in Eastern Europe (Enyedi, 2016). In Orbán's illiberal democracy, while elections are organized, the system is tilted to favor Orbán's party, Fidesz (Scheppele, 2022), the opposition is side-stepped, and state institutions have been captured by party cronies to the extent that citizens have no control over rulers (Sata and Karolewski, 2020).

To respond to condemnation for deconstructing liberal democratic norms and violating European values, Orbán has deflected criticism by becoming the most vocal opponent of EU integration, blaming the EU for imposing policies that people reject. At the same time, public support for the European project has been consistently high among ordinary Hungarians and there is even an increase in support since 2012 (Göncz and Lengyel, 2021). Hungary also benefits the most from EU membership financially (Hungary Today, 2019). Notwithstanding these, Orbán has only radicalized his Euroscepticism once in office and has become the pariah of the EU.

Previous research on Orbán's populist discourse has argued that Orbán attacks the EU to maintain his populist strategy while in office. Hegedüs (2019) shows that Orbán “externalizes” from the domestic to the European/international level, the “us vs. them” populist strategy, to allow him to continue his radical “anti-elite” message despite being in office. Csehi (2019) shows that the endurance of Orbán's populism is explained by a “three-course approach”: an ability to reinvent and reinforce the dichotomy of the “people” vs. “elites” together with a remodeling of popular sovereignty. Kim (2021) argues similarly that pitting “good people” vs. various “evil elites”, it is the exclusive claim to popular sovereignty that makes Orbán's populism authoritarian; while comparing Orbán to Kaczyński, Csehi and Zgut (2021) argue that both exhibit a discourse of Eastern European version of Eurosceptic populism that relies on the “anti-imperialist tradition” popular in ECE to oppose the EU.

Building on these explanations, I argue that Orbán uses populist discourse to rally support based on crisis fears rather than policy performance. Orbán continuously performs and perpetuates crises—at least discursively—to turn policy choices into existential fights for Hungary and its people. The continuous performance of crisis is all about discursive processes of “othering” that not only define “the good people” but also its enemies to be blamed for the crisis(es). This study reveals the great flexibility in how Orbán attaches various meanings to the “empty signifiers” (Laclau, 2005) of “us” and “others,” to fit his interest. The various crises result in different understandings of both the “self” and “threatening others.” At the same time, Orbán always depicts Hungary as the center of Europe, while the EU (that Hungary is a member of) is the betrayer of people. This false discursive construct helps Orbán act European while working against the EU. With each crisis performed, new conflict lines between various conceptions of “European selves” and “threatening EUs” are identified, each adding to the radicalization of Orbán's discourse which is a populist narrative that is Eurosceptic at the core, being nativist and xenophobic in being anti-migrant and anti-Muslim, and anti-democratic and authoritarian in denying pluralism and minority opinion, all in the name of protecting people.

The article proceeds as follows: the first section provides a brief introduction to the Hungarian context and its roots in identity politics that the present discourse exploits. The next section presents how processes of discursive othering—defining both “us” and “others”—are key for both identity formation and performance of crisis that rests on defining both the good people and its enemies to be blamed for the crisis. The third section examines Orbán's political discourse during his 2010–2014 government and argues that the narrative is a prime example of economic grievance-based populism, where both the “self” and the “others” are understood in financial terms. Performing a financial crisis, the EU is portrayed as an enemy for betraying the ordinary people and siding with foreign capital and the IMF. The following section examines the discourse of 2014–2018 and claims that the othering gains an ethno-populist character from 2015 onwards, with a strong anti-migration stand, justified by Orbán's performance of the migration crisis as an existential threat. This way migrants and the EU's refugee resettlement system must be stopped to not water down Hungarian identity or traditional European culture. The following section presents the 2018–2022 discourse that continues to be anti-migrant and also presents the EU “gender ideology” and promotion of LGBTQ rights as endangering traditional Hungarian families and lifestyles. The 2020 pandemic crisis is performed by Orbán as any other crisis—The health emergency is just another opportunity to attack the political opposition and the liberal world order as embodied by the EU for allegedly putting Hungarian lives at risk. Finally, the article concludes by summarizing how each performed crisis and its corresponding images of the “self” and “dangerous others” only add to the radicalization of the discourse.

While suppressed under communism, nationalism and identity politics have gained prominence in Hungary after the regime change. While strong nationalist feelings characterize the entire Central and Eastern European region, nationalism plays a particular role in Hungarian politics for historical reasons. The country has lost about two-thirds of its territory and one-third of its people to neighboring countries after World War I and ever since, the protection of Hungarians abroad (a term used to refer to Hungarians living in countries neighboring Hungary) has been high on the political agenda. Care for the kin abroad has a specific role in international politics as well; post-communist Hungary established a very generous system of minority accommodation with extensive self-governance rights for minorities primarily to stand as an example for neighboring countries with Hungarian communities living there (Bárdi, 2013).

Nevertheless, in contrast to this exemplary minority policy aimed at the external world, chauvinism and xenophobia are common among ordinary Hungarians, as shown by public opinion polls (e.g., Simonovits et al., 2016; p. 41). Nationalist feelings are often coupled with anti-Semitism and anti-Roma sentiments. This is a little surprising, as Hungary comports with the region—majoritarian nation-building has happened at the expense of minorities in Central and Eastern Europe (Culic, 2009). These exclusionary sentiments and anti-establishment attitudes also explain the success of radical right parties1 in Hungarian politics (Karácsony and Róna, 2011; Bíró Nagy et al., 2013).

Exclusionary nationalist attitudes provide solid ground for current identity-based politics. Disillusion with the post-1989 political transition and economic hardship following the 2008 financial crisis only further radicalized societal views (Kim, 2021). Using a populist discourse, Orbán has successfully exploited identity fears to return to power, winning with his party, Fidesz, a two-thirds majority in 2010. Winning four consecutive elections (2010–2022), Orbán is one of the longest-ruling populist leaders in the world, showing no sign of moderation of his populist discourse. At the same time, Orbán's populist rule has replaced the programmatic appeal to the voter with identity politics. Fidesz has no party program: the party has won all successive elections (both national and European) since 2009 without a party manifesto.

Once in power, Orbán set out to build a “system of national cooperation”: he modified repeatedly Hungary's constitution and the electoral system and removed checks on executive power by weakening the judicial system (Scheppele, 2022). The state has been captured by the party, enabling Orbán to establish a vast patronal network, while extensive media control allows for controlling opposition voices and ethno-populism is employed to rally the support of the people (Sata and Karolewski, 2020) and mask the authoritarian move (Kim, 2021). The curtailment of democratic rights and rules went to such an extent that many question whether Orbán's illiberal regime is democratic at all (Bozóki and Hegedus, 2018; Palonen, 2018).

Identities are constructed based on differences from “others” as identity is impossible to define without a difference (Stavrakakis et al., 2018). It is processes of discursive othering that create the meaning of both “us” and “them,” defining who belongs to the community and those who do not. In these processes of othering, “us” vs. “them” are discursively defined, relying on inclusion and exclusion along several categories and symbolic boundaries. The different conceptualizations of identity compete with each other, both within the group and between groups (Abdelal et al., 2001). Identity is thus the result of both its content and relational feature as in-group identity produces competition vis-a-vis out-groups. In this sense, belonging to the national community can be understood as being a member of an “imagined” one and valued above all other groups' communities (Gellner, 1983; Anderson, 2006).

Political discourses and narratives play a key role in how people perceive themselves and others. At the same time, political discourse is central to developing new political strategies and policies that are considered legitimate by the public. In the ideal world, all policy is developed as a result of a series of debates among competing ideas and understandings of the world (Dryzek, 2013). It is this process of sharing knowledge, understanding, experiences, or expectations with other members of the community that creates a common understanding, an intersubjective construction of meaning (Christiansen et al., 1999). All political discourses interact with each other in the public sphere in a process that could be called the discursive construction of reality (Lazar, 2005), the means to provide the community with an understanding of the world (Wodak, 1997; Wodak and Weiss, 2005).

Processes of discursive othering are central not only to identity formation but also to political discourse. Distinguishing “the other” from “us” emphasizes (different) material characteristics but also centers on ideational aspects that distinguish the “self” from the “other” (Bacchi, 1999; Lazar, 2000). Human reality is socially constructed and articulated in discourse (Stavrakakis and Galanopoulos, 2018) and ideational interpretations are often more important than empirical facts. In this sense, the framing of “us” focuses on particularities—be it real or imagined—that are evoked to exclude the “others” (Yuval-Davis, 1998; Wodak, 2007a,b). Moreover, if the “other” is framed as posing threat, those allegedly responsible can be blamed for the problem (Meeusen and Jacobs, 2017). This way, the discursive processes of “othering” can condition identity formation for both “us” and “them” (Jensen, 2011) and provide a particular meaning or construct reality in specific ways, shaping identities, values, or political preferences.

Populism can be understood in many ways and there is no universally accepted definition in the literature. Some see it as a political logic (Laclau, 2005), others as a political communication style (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007), as a political style (Moffitt and Tormey, 2014), or as a strategy (Weyland, 2017). The most common understanding of populism, the ideational approach (Mudde, 2004; Stanley, 2008), claims that society is ultimately divided into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” and “the corrupt elite” or “dangerous others,” and politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people (Mudde, 2004, p. 543; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2013). At the same time, populist categories of “the people” or “elites” and “others” are “empty signifiers” (Laclau, 2005) or “empty vessels” (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2013, p. 151) that are retroactively constructed, creating with great flexibility the meaning that is supposed to express (Stavrakakis et al., 2018).

Processes of discursive othering give meaning to these empty signifiers of populist discourse, providing meaning for both “the people”and its enemies. While many think of populism as defined by homogeneity and a moral thesis—Mudde (2004) defines the homogeneous people as morally pure and opposed to evil and corrupt elites (see for similar argument Kim, 2021)—I believe the populist divide between the people and the elite/others is not necessarily a moral one but a political one. All kinds of political actors draw on moral values in their discourses and moralism cannot be used to distinguish populists from others (Wodak, 2007b; Stavrakakis and Jäger, 2018; Katsambekis, 2022). Instead, policies and policy issues can become moralized and demoralized (Kreitzer et al., 2019), based on how political actors treat these in their discourse.

This article adopts the performative theory of populism based on Moffitt's (2015) understanding that the performance of crisis is an essential core feature of populism. Accordingly, the crisis is only a crisis if it is experienced through performance and mediation and one can examine political discourse to reveal how social failures or problems are “constructed and performatively narrated as a crisis, attributed to the action of an enemy … simultaneously triggering the radical construction of the people” (Stavrakakis et al., 2018; p. 15). In turn, changes in the discourse will be reflected in the new discursive constructs of “us” and “others.” Performance of crisis helps populists divide “the people” and “others” and pretend they represent the “voice of the people.” This not only helps advocate strong leadership but also radically simplifies the terrain of political debate, often turning complex issues into binary views or rights and wrongs, which in turn call for simplified solutions of “with us” or “against us.”

Populism can be both inclusive and exclusive, depending on who is excluded from or included in the category of “people” (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2013). While populism on the left is rather transnational and views the “people” as the global under-dog (mainly in economic terms), right-wing populism is often (if not always) nationalist (Jenne, 2018; p. 546) and is defined by its exclusionary preferences (Ignazi, 2003; Mudde, 2007): “the core element of which is a myth of a homogenous nation, a romantic and populist ultra-nationalism which is directed against the concept of liberal and pluralistic democracy and its underlying principles of individualism and universalism” (Minkenberg, 2013; p. 11).

Euroscepticism has become a primary feature of party core ideologies (Szczerbiak and Taggart, 2017) and is often in tandem with populism (Rooduijn and van Kessel, 2019). Right-wing populist politicians are Eurosceptic because of their romantic and populist ultra-nationalism positions them by default wary of losing sovereignty to the EU. In line, Orbán's populism is Eurosceptic and combines nationalism with a neoconservative traditionalist ideology to promote a romanticized ideal of the national community in some golden age, uncorrupted by elites or “others.” For Orbán, the golden age does not refer to a specific time but is rather a patchwork of different elements of “greatness” (Dessewffy, 2022). Orbán discursively links this “greatness” to a pinnacle of European civilization to create a joint frame of reference and bolster Hungarian “proudness,” despite Hungary being a small European country. Nostalgia is used not only to legitimize Orbán's claims to political authority but to portray Hungary as defending traditionalist Europe against or from the EU (and various others). This false discursive construct of Europe against the EU is at the center of Orbán's right-wing populist strategy and allows Orbán to act “as European” and deflect all criticism of the illiberal regime as revenge for defending traditional forms of life and values from the Brussel elites.

The performative approach to populism ignores the demand side of populism by focusing exclusively on the supply side, as manifested in political discourse. Studies on populist discourse focus on rhetorical strategies, discourse-analytical concepts relating populism to hegemony, and the agenda of populist politics. Empirical studies rely on both quantitative and qualitative methods, covering different political actors and focusing on similarities and differences in their rhetoric and discourse across the globe and across political affiliations (see e.g., Hawkins, 2009; Bernhard et al., 2015; Kriesi and Pappas, 2015; Hawkins and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018; Hawkins and Silva, 2018; Schulz et al., 2018; Ribera Payá, 2019). In the same tradition, I examine how Orbán discursively performs crises and employs processes of discursive othering in defining “the good people” and its enemies. More precisely, I focus on how the “we” and the “other” are filled with meaning, using different criteria in each crisis performed, and how these conceptions change over time; what populist themes and frames are present; and how these interact with the processes of othering. Traditional themes and frames associated with populist discourse are an appeal to the people, representing people's will, or its anti-establishment, anti-elite, or anti-politics character; Manicheism; as well as questioning political correctness, a breakdown of taboos or bad manners that enter public talk (Moffitt and Tormey, 2014).

I look at framing as a tool-making aspect of certain issues more salient through different modes of presentation (McCombs, 2004). Framing is thus a central organizing idea or a storyline to provide meaning to an issue or an event (Feinberg and Willer, 2019). Based on their expectations about what frames will generate the most support within the public, political actors can use rational/instrumental frames to assess the value of a policy through its effects, or moral frames to involve moral arguments above all others (Chong and Druckman, 2007; Mucciaroni, 2011; Jung, 2020). I examine whether and how much Orbán's political messages are framed as questions of fundamental, moral beliefs about right and wrong (Lakoff, 2002) because morality frames also make discourse caustic and disable consensus, accusing rivals as immoral as they build animosity among individual citizens and largely increase affective polarization in society (Ryan, 2014; Feinberg and Willer, 2019; Jung, 2020).

While previous studies of Orbán's populist discourse focused on selected speeches only (e.g., Csehi, 2019; Hegedüs, 2019; Csehi and Zgut, 2021), this study examines all the speeches, declarations, interviews, or press statements delivered by Orbán between 2010 and 2022—three full governmental cycles that are available on the PM's website. While the texts contain different types of speeches, from public talks to press statements or interviews, both domestic and international, all speeches are treated the same for analysis.2 I focus on the PM's speeches because of his absolute power over Hungarian politics. I compare the discourse of the three governmental cycles to identify any substantial changes, possible moderation, or radicalization of the discourse. I employ mixed methods for discourse analysis that relies on quantitative exploration of the content of the speeches, followed by an analysis of the frames. The qualitative analysis relies on keyword and keyword-combination frequencies (see Supplementary material for figures and frequency scores) to establish the main frames of reference used in the discourse. Changes in the frequencies highlight how frames are constructed or changed and what the tone of the message is. Excerpts of the speeches are used to highlight the processes of discursive othering that fill up the meaning of both “us” and “dangerous others” in different ways for each different crisis that is being performed.

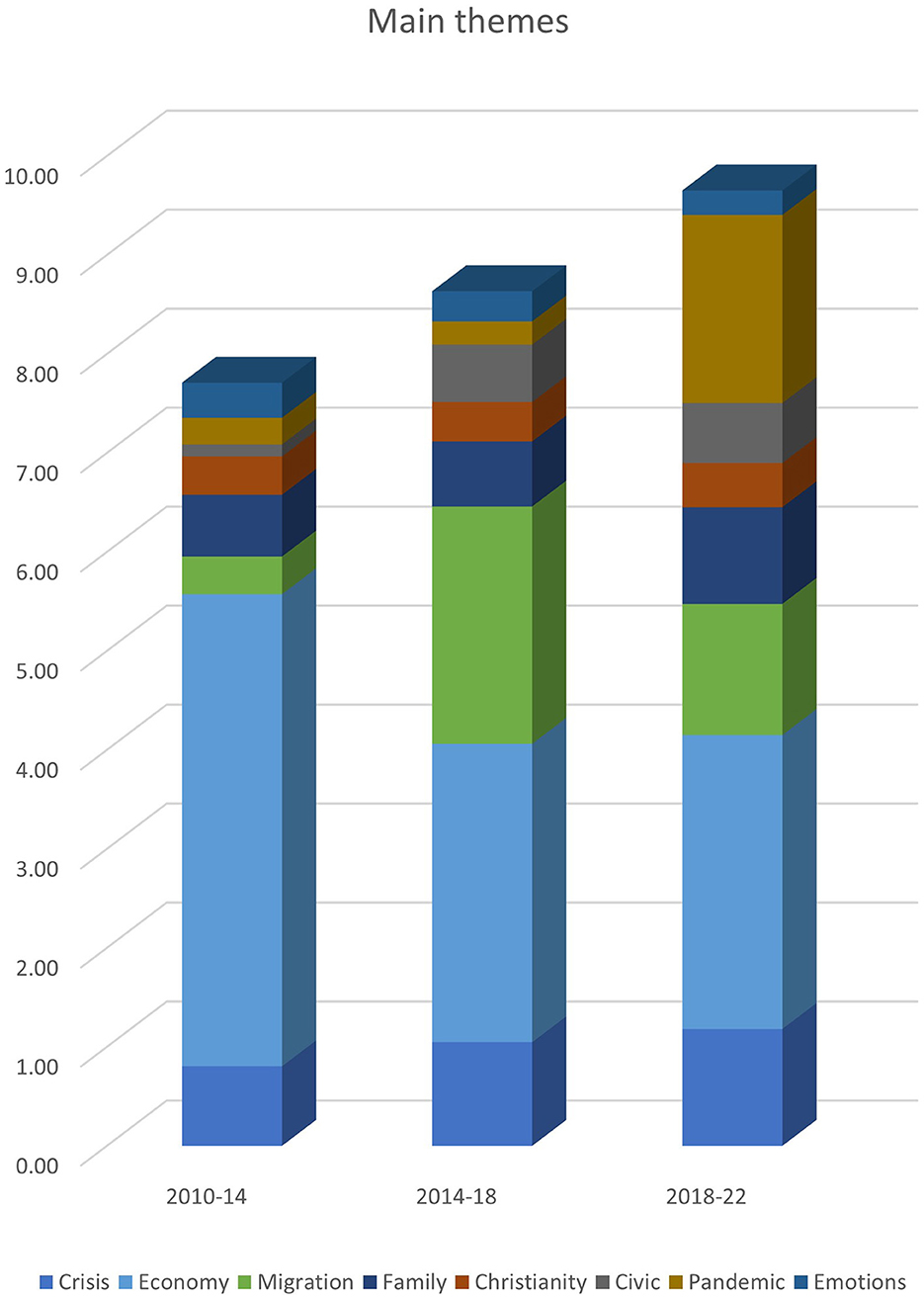

The primary theme for Orbán's discourse during his 2010–2014 government was the 2008 financial/economic crisis (Figure 1). This is not surprising since the economic crisis hit Hungary particularly hard, compared to other countries in the region. Performing economic crises, the speeches often talk about capital and markets vs. the people and the Hungarian economy—A prime example of populist discourse (Supplementary Table 1). The answer to the crisis offered by Orbán is also populist, a simple solution to a complex problem—The need to protect the people. This way, the financial crisis justifies decisive and immediate action—His unorthodox economic policies: the introduction of “crisis taxes” of various sectors, nationalization of private pensions to fill in budget holes, reductions in social aid and unemployment benefits, or reduction of energy tariffs but also a reconfiguration of the entire state apparatus, filling it up with Fidesz cronies all done under the pretext of protecting people's interest.

Figure 1. Main themes. Own computations, MAXQDA. Word combinations of two to five words are considered. All speeches of the respective period were compiled into a single document, words were lemmatized, and min. character length was set to 2. The software relies on English stop-words and only considers word combinations within a sentence or parts of sentences as defined by common separators (;, – () … []). To compile topics/themes, word context is explored, and context is set to 10 words ahead and 10 words for the selected word/phrase.

Although the financial crisis is an international crisis, all speeches target solely the national group: foreigners or aliens are barely mentioned, and migrants and immigrants are never of interest except when talking about Hungarians, who went to work abroad. Given the nature of the crisis, Orbán depicts the “self” in an economic conception, while the “dangerous others” are also portrayed in financial terms: “banks,” “bankers,” and “multinationals” represent international capital, blamed for the crisis. Orbán blames profit-seeking at the expense of “the people,” as well as the incompetence of the former political elite for the crisis “that threatened to push Hungary into bankruptcy” (Speech 36, 4 Oct. 2012). This way, the discourse is populist and anti-elite, while it also attacks the neo-liberal capitalist establishment, yet it constructs the community in economic rather than ethno-national terms (not all populism is nationalist, see Brubaker, 2020).

Following the 2008 crisis, the former socialist-liberal Hungarian government started bailout negotiations with the IMF that was joined by the EU in demanding austerity measures from Hungary. Claiming that these would hurt “the people,” Orbán broke negotiations once in power and opted for his unorthodox policies to manage the crisis in the “Hungarian way.” At the same time, despite Hungary being an EU member, he portrays the EU as a “dangerous other” for siding with IMF instead of supporting the Hungarian people. Orbán externalizes the populist “us vs. them” logic (Hegedüs, 2019) as EU bureaucrats become “others” to be blamed for the crisis and fought together with multinationals and bankers: “we do not wince with respect to anybody; not from the raised voices of multinational companies, nor from the threats of the bankers, nor from the negative forecasts of financial circles, nor from the raised fingers of Brussels bureaucrats' (Speech 100, 28 Jan. 2014).

Claiming that Hungary is a central member of Europe, Orbán is not shy to stand up to the EU and demand equal treatment instead “any of the EU's institutions behaving disrespectfully toward Hungarians” (Speech 9, 23 Oct. 2012). While Hungary's European belonging is cherished by Orbán, the EU is portrayed as “a bureaucratic empire in Brussels” (Speech 53, 16 Jul. 2013) that wants to “dictate a uniform economic policy” (Speech 53, 16 Jul. 2013). This way, the processes of discursive othering result in a fascinating duality of the discourse: the “cultural self” strongly belongs to Europe and European Christian civilization, but the “economic self” is defined in opposition against the EU and its common neoliberal market policies. Displaying demand for austerity policies as dictates of the Brussels empire, Orbán also relies on the anti-imperialist tradition to mobilize his supporters (Csehi and Zgut, 2021).

Despite this duality of the cultural and economic conceptions of the “self,” Orbán's speeches rarely mention culture and traditions specific to Hungary when defining the “good people” (Supplementary Table 1). There is only one exception to not using ethno-cultural markers of identity and that is language. Language becomes the basis of Hungarian uniqueness: “our language is a very unique one, a very ancient one, and is closer to logic and mathematics than to the other languages” (Speech 68, 18 Oct. 2013). Language not only defines the ethno-cultural community but also unites it since it is “a secret code for Hungarians that generates the feeling that we belong to the same family” (Speech 68, 18 Oct. 2013).

At the same time, since the Hungarian language is portrayed as unique, it also becomes a barrier to identifying with Europe since its uniqueness “excludes us from the world and encloses us within our own” (Speech 69, 22 Oct. 2013). To claim European belonging, Orbán opts to portray discursively Christianity and Christian roots as common markers of Hungarian and European identity. In line with Western right-wing populist politicians” use of religion only as identity without faith (Brubaker, 2017), Orbán claims that Hungary belongs to Europe via its Christianity—though without any religious meaning but rather understood as a set of values, standards, and behaviors, a source of morality.

Cherishing its Christian culture and values, the “self” can be portrayed with a high moral stance against the “immoral creditors” whose unrestrained profit-seeking is blamed by Orbán as causing the crisis. At the same time, Christian belonging is also a divider between Hungary and the EU, and Orbán attacks secular Europe claiming “Europe that has forgotten about its Christian roots is like a man who built his home on sand with no foundations” (Speech 13, 16 Nov. 2012). Opposed to this, Hungary is ready to fight “European political and intellectual trends and forces which aim to push back and undermine Christian culture, Christian civilization and Christian values” (Speech 15, 17 Nov. 2012).

Orbán's discourse revolves around the financial crisis that he evokes to blame it on the global world order and EU integration. In this conception, the EU is blamed for betraying the people since “the bureaucrats in Brussels, who rather than supporting us, stood by the banks and the multinationals” (Speech 92, 13 Dec. 2013). Blame attribution only helps him rally support for national sovereignty to be able to oppose EU common policies or market rules that supposedly lead to the economic downturn. To be able to resist foreign investors and multinationals, Orbán claims that nations should decide their economic policies on their own, without any supranational interference, to ensure that the profits of people's work “are not taken outside Hungary's borders” (Speech 26, 22 Feb. 2012).

Orbán performs the crisis not only to establish whom to blame but to present himself as one of the people, speaking for and in the name of the Hungarians—another populist discursive strategy—evidenced by the extensive use of the terms “us” and “our.” The discourse is anti-establishment, both directed at the domestic scene, as well as the international arena. The EU is accused of using double standards and abusing its power when dealing with Hungary (Speech 52, 4 Jul. 2013), while the former liberal-socialist government is blamed for cheating the people and leading the country into crisis, using a logic of “let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die” (Speech 15, 17 Nov. 2012). This way the processes of discursive othering are key to distinguishing the “good people” vis-à-vis corrupt domestic and international elites, blamed for the crisis. Elites are immoral as evidenced by Orbán portraying his political opposition as heirs of the socialist communist party, equating them with “a political construct based on the bad in people” (Speech 39, 30 May 2013), while using the same logic, the EU is compared to the Soviet Union for endangering sovereignty since “the decisions on Hungarian freedom and the fate of Hungary were not left to the Hungarians” (Speech 50, 2 Jul 2013).

Orbán's 2010–2014 political discourse is a textbook example of economic grievance-based populism. Orbán's discourse uses all the common populist frames to rally support for his regime: it blames former elites and the establishment as well as international markets and the EU for economic troubles, while it speaks as one of the people, for the people. He presents all issues through the populist performance of crisis, where Hungary is depicted as being cheated by its former elite as well as the EU, enabling foreign international capital (and IMF) to push the country into near bankruptcy. In this economic crisis, perceptions of the “self” are defined mainly in financial terms, in opposition to economic enemies with little to say about ethno-cultural identifiers. Hungarian interest is defined against foreign capital, while Hungarian sovereignty is to stand against the supranational EU and its common economic policies.

Following the introduction of a new electoral system that gives undue advantage to the winning party (Scheppele, 2022), Orbán's Fidesz has maintained its two-thirds majority in parliament with only 44.5% of the popular vote in the 2014 elections. Orbán's narrative remains populist and the 2014–2018 speeches show that crisis remains at the center of the discourse, the only change is that the 2008 economic crisis has been replaced with the 2015 European refugee crisis (Figure 1). Migration becomes the new performed crisis for Orbán's speeches, more than half are on this topic. Notwithstanding this, one should note that although hundreds of thousands of refugees entered Hungary in 2015, all of them left heading for Western Europe. Hungary has virtually no migrants and is not a target of migration but rather a source country for people leaving for work in the UK, Germany, or Austria.

As the frequency scores show (Supplementary Table 1), migration was never a topic until 2015. Yet, even before the 2015 refugee crisis emerges, Orbán claims in his State of the Nation Address on 27 February 2015 (Speech 233) that liberal multiculturalism must be opposed because migration brings “people, many of whom are unwilling to accept European culture, or who come here with the intent of destroying European culture.” Once the migration crisis starts in the summer, Orbán's discourse focuses exclusively on an anti-migrant narrative that only radicalizes over time, with Orbán soon breaking taboos—yet another populist discursive strategy—declaring that “immigration brings crime and terrorism to our countries” (Speech 325, 15 Mar. 2016).

Portraying migration as the new existential crisis for Hungary, Orbán's discourse also redefines conceptions of both the “self” and “others.” The processes of discursive othering remain at the center of the discourse, the previous financial understanding of the “self” is exchanged with a new, more cultural understanding, and the “other” is also reconceptualized either as the migrant or the common EU refugee scheme demanding that Hungary accepts refugees part of sharing the EU burden.3 Similarly to what we have seen for 2010–2014, the processes of discursive othering are clearly linked to blame attribution—migrants threaten Hungarian culture while the EU and liberal EU members are blamed for bringing migration to Hungary. Once again, Orbán defines Hungary's interest in opposition to the EU: while “in Brussels and in some large EU Member States the dominant opinion is still that immigration is on the whole a good thing” (Speech 285, 16 Nov. 2015), Orbán claims that migration will endanger the very existence of Hungary.

The performance of the migration crisis focusing on the cultural/civilizational divide between the “self” and “others” affects profoundly the re-conceptualization of the Hungarian self. Orbán stops using the term “the people of Hungary”, which would suggest addressing citizens, and instead focuses on the terms “Hungarian nation” and “Hungarians” (Supplementary Table 1), putting in focus the ethno-national community. This reconceptualization also results in an increased reference to Hungarian culture and traditions when defining the “self” that previously was missing. This new meaning of “us” is interwoven with ethnicity, culture, tradition, and a unique “thousand-year-old civilization” (Speech 398, 15 Dec. 2016). In turn, this essentialist understanding of identity is evoked by Orbán to exclude all other cultures or identities to safeguard Hungary's identity (Speech 335, 25 Apr. 2016). Keyword results suggest that even more threats from “others” as references to “protection” and “security needs” (Supplementary Table 1) have increased 5-fold as compared to the previous period. This way, the migration crisis is performed into a cultural threat, and the processes of discursive othering are tailored to tap into people's cultural fears.

The terms used by Orbán in his speeches also point out this radical anti-migrant discourse. He uses the terms “migrants” and “immigrant” five times more often than the terms “refugee” or “asylum seeker” (Supplementary Table 1). For Orbán, most refugees are economic migrants, seeking a better life in Europe and therefore are not entitled to empathy or support, Hungary has no duty to help but rather should defend its own interest. Orbán sees migration bring the threat of a “clash of civilizations” as accepting Muslim migrants, the “identity of civilization in Europe could change” (Speech 251, 2 Jun. 2016). This way, Orbán taps into the idea made famous by Huntington (1993) about essential cultural characteristics that render East and West incompatible and destined for conflict. Although this reductive approach to culture and geopolitics has been widely rebuked (Said, 2014), this does not prevent Orbán portraying the alien “other” not only as culturally distant but as civilizationally different, further distancing the in- and the out-group in the discursive othering process.

This cultural/civilizational understanding of the “self” also results in more cultural othering of migrants, which is most noticeable in the religious references used in the discourse. The previous identitarian reference to Christianity in defining the “self” has acquired a new, more religious understanding. This way, religion and faith become criteria of discursive othering, with Orbán often positing Christianity or Christians against Islam and Muslims. He is clearly committed to an exclusively Christian Hungary and Europe and he is proud to declare that “in Hungary Islamization is subject to a constitutional ban” (Speech 335, 25 Apr. 2016). Using religion as a means of othering presents a mixture of Eastern and Western use of religion in right-wing populist discourse that although driven by the notion of a civilizational threat from Islam, rejects Western nationalism's shift to civilizationism that “internalizes liberalism, secularism, philosemitism, gender equality, gay rights, and free speech” (Brubaker, 2017, p. 1208)—all opposed by Orbán.

While Orbán always performs crises to portray the various “others” as dangerous, the “migrant other” is conceived as a direct security threat for Hungary and Hungarians. Orbán defies political correctness when he not only claims that migration and criminality are linked but he thinks migration carries the “threat of terrorism or terrorists” (Speech 285, 16 Nov. 2015). For the same reason, while in 2010–2014, Orbán never really engaged with the issue of terrorism, since 2015, he often talks about terrorism or terrorist organizations (see Supplementary Table 1). This way, he does not only discursively construct the migrant into an “other” who is culturally, religiously, or civilizationally different, but also as someone posing a direct risk to the life of Hungarians (Speech 471, 19 Jul. 2017).

Securitizing the discourse against “dangerous others,” the migration crisis also calls for strengthening of Hungary's borders to protect the “good people.” Border protection becomes indispensable because, according to Orbán, “each nation is defined by its borders” (Speech 257, 24 Jul. 2015). Despite Hungary being part of Schengen and thus borderless Europe, Orbán believes only sovereign borders can protect Hungary and its culture. The Fidesz government has built a fence along most of the southern border of the country in 2015 and Orbán even claims that by stopping mainly Muslim immigrants, he is protecting “Europe's essence [that] lies in its spiritual and cultural identity” (Speech 283, 16 Nov. 2015).

At the same time, reinforcing borders also positions Hungary against a borderless EU since Orbán claims only the self-rule of the people—represented solely by his government—is legitimate. While in 2010–2014, Orbán portrayed himself as a defender of Hungarian economic interests, now he is fighting for the cultural survival of not only Hungary but Europe. In turn, the EU is once again portrayed as the threatening “other,” who endangers or would water down this civilization with its liberal multiculturalist policies. Claiming that the people do not agree with the politics of the EU (Speech 294, 2 Dec. 2015) and it is the EU's liberal philosophy and multiculturalism that makes Europe weak (Speech 265, 5 Sep. 2015), Orbán claims that Hungary—sharply opposed to the EU and its liberal core—will defend Europe and its civilization both from the migrants and the EU itself since Hungary is “the continent's gatehouse and bastion” (Speech 439, 20 May 2017).

To serve the process of discursive othering of the EU, Orbán also employs conspiracy theories that resemble a deep-state narrative when he claims that the EU enacts the so-called “Soros plan,” an alleged proposal of American billionaire of Hungarian origin George Soros supporting international migration. Orbán claims domestic and international NGOs, feminist activists, liberal thinkers, or university academics—the “Soros troops”—are the dangerous others because “they are ridiculing faith, and they regard families as redundant, and nations as obsolete” (Speech 515). Instead, Hungary is to be strengthened by family-friendly policies to stop the demographic decline (performed as another crisis by Orbán) without letting in immigrants.

At the same time, while the migration is identified as the new enemy to fight, there is little change in the rest of the discourse as conceptions of Hungary being in the center of Europe while the EU is a “threatening other” persist despite the very different nature of the 2008 and 2015 crises. In this conflict, the main dividing line between Orbán and the EU remains national sovereignty, and Orbán opposes any loss of sovereignty claiming that the right to decide is to be reserved for the people solely. Tapping into anti-communist and anti-imperialist traditions (Csehi and Zgut, 2021) common in Hungary, Orbán claims that “the task of Europe's freedom-loving peoples is to save Brussels from Sovietisation” (Speech 371, 23 Oct. 2016), as imposing EU rules (on migration or refugees) on Hungary is similar to Soviet practices of centralized rule. Orbán is ready to defy EU rules and rather defend people's will, even if this means “we can even expect revenge and blackmail from the Commission” (Speech 359, 3 Oct. 2016).

All the above shows that Orbán continues to perform crisis and the existential threats resulting from it are at the center of the discourse to rally the support of the ordinary people based on their various identity fears. In this sense, the only difference between the 2010–2014 and the 2014–2018 discourse is that we see more nativist elements enter the discourse to define both the “self” and the “other” in a more religio-cultural sense as the focus switches from the financial crisis to the migration crisis. At the same time, Orbán relies on the very same populist discursive strategies that he used before: he talks as one of the people and for the people, claiming to represent public will: “we want to govern on the basis of the mandate provided by the people, jointly with the people and in the interests of the people]” (Speech 201, 6 Jun. 2014).

Given the success of performing the migration crisis in mobilizing people, fighting migration remains one of the main topics for the 2018–2022 discourse (Figure 1), despite having no migrants and a fence erected to stop them from entering the country. Orbán is thus discursively creating/maintaining the crisis by blaming the EU and Western countries for wanting Hungary to become an immigration country. More precisely, Orbán maintains his conspiracy theory of the so-called “Soros plan,” claiming the “decision by the European Parliament is nothing less than a decision that serves and implements… George Soros's plan” (Speech 686, 25 Jan. 2019).

Since Orbán continuously performs the migration crisis, we see little change in the discursive construction of “us”: Hungary remains portrayed as a unique community, with a Christian culture and thousand-year traditions that is back on its feet—thanks to Orbán's leadership—ready to protect its culture. Even demographic decline is to be resolved by pursuing “family-centered policy” (Speech 644, 18 Sept 2018) instead of encouraging immigration. Hungary is not only projected to be at the core of Europe, but Orbán claims he is serving not only Hungarian but Europe”s interest—“Hungary comes first, but through our work we also want to strengthen Europe” (Speech 615, 20 May 2018). However, this is a Europe of sovereign nation states, defending tradition and Christianity since EU integration and multiculturalism are to be opposed as the main threat to cultural identity.

Based on the above, Orbán maintains discursively the migration crisis to continue to portray the EU as the “dangerous other” for promoting migration under the sway of George Soros (Speech 856, 7 Oct. 2020). The only change is a radicalization of this crisis narrative that projects an intensification of the alleged threat of “others”: while in the past Orbán has portrayed migration mainly as a question of national sovereignty and security, now he presents the issue as a subject of a fundamental question about rights and wrongs. He claims that on the one hand, EU liberals push for a secular, multicultural world with “neutral values” but people, on contrary, prefer “absolute values revealed by God, and the religious and biblical traditions that have grown out of these” (Speech 848, 21 Sep 2020).

By discursively constructing the migration crisis as a conflict about fundamental values, Orbán takes the conflict to a higher level. This is not a disagreement of policy preferences anymore but rather a fight about “justice, public morals and the common good” (Speech 621, 16 Jun. 2018). It is a value conflict between illiberal Hungary and liberal EU and Orbán claims that “[liberal] Europe's neutral fundamental values” must be rejected and a new “cultural era” (Speech 634, 28 Jul. 2018), opposed to the liberal world order, must be built in Hungary. The language of the discourse, which is more extreme than previously seen, often breaking taboos also signals this heightened conflict. Accusing the EU of giving up on its Christian values, Orbán talks about being forced to wear a “spiritual straitjacket” (Speech 621, 16 Jun 2018) that restricts freedom, since in his portrayal, “without Christian culture there is no Hungarian freedom—nor a free Hungary” (Speech 701, 15 Mar. 2019).

The exacerbated conflict between illiberal Hungary and the liberal world is also signaled by gender entering the “war of symbols” against liberalism (for a similar argument see Engeli et al., 2012) as gender becomes the “symbolic glue” (Kováts and Pető, 2017) to represent all progressive politics, which Orbán claims have “failed the people.” While Orbán's discourse never really talks about gender issues and the rights of sexual minorities, these enter his talk from 2018 and remain important topics even during the pandemic. Since Orbán only thinks of women as mothers and family caretakers, he proclaims “gender ideology and rainbow propaganda” (Speech 848, 21 Sep. 2020) are against the ideal of the family that Hungarians cherish. Opposed to this, the EU promotes “LGBTQ lunacy” (Speech 895, 4 Mar. 2021) that Hungarian children must be protected from.

European proceedings against Hungary's rule of law violations are also reinterpreted and performed as yet another crisis. Claiming Hungary is free of wrongdoing, the Sargentini report and the EP vote4 is presented as the EU's attack on Hungary that “seek[s] to pass moral judgement and stigmatize a country and a people” (Speech 640, 11 Sep. 2018). Orbán claims that alleged rule of law violations are a result of hate and revenge for opposing the EU migration scheme: “countries… that hated us since [the migration crisis] want to link the use of this money to political conditions. I'm not exaggerating; they have a personal antipathy to us Hungarians” (Speech 835, 24 Jul. 2020). This emotional appeal within the narrative not only signals a break with political correctness but also underlines that conflict with the EU is not about rational policy options anymore but rather portrayed as a fight of emotions.

The 2020 COVID crisis refocuses the post-2020 discourse on the pandemic but at the same time, Orbán continues to refer back to the financial as well as the migration crisis (Figure 1), portrayed as major points of success of his government in dealing with the crisis. This way, even the discourse of the pandemic is less about the actual health crisis but rather about crisis performance, more specifically the alleged success of Orbán's ability to fend off crises. Similar to the financial or the migration crisis, Orbán wants to go his own way to resolve the health crisis, accusing the EU's pandemic coordination efforts of unnecessary delays that “obstruct the Hungarian people's defense operation” (Speech 803, 27 Mar. 2020).

Orbán performs the COVID-19 crisis like any other crises—despite its extraordinary nature, the pandemic is just coupled with his discourse on the migration crisis by saying Hungary is “in a war on two fronts: on one front there is migration, and on the other the coronavirus epidemic” (Speech 795, 15 Mar. 2020). The health crisis is thus performed as part of the ongoing struggle between Hungary and the EU, and Orbán manages to convey blame on Brussels even for the pandemic: “they're sitting in some sort of bubble; and instead of saving lives, they're busy telling other people what to do” (Speech 804, 30 Mar. 2020). The domestic opposition shares the blame as it is allegedly not fighting the virus but rather Orbán's government. Critics of the regime are accused of all possible wrong-doing and betraying the nation for siding with the EU using language rarely seen in democratic politics: “backstabbing and backbiting, undermining of national strength and solidarity, sniping at political leaders and experts leading the country's defense operation, snitching and betrayal in Brussels, sabotage and trickery” (Speech 848, 21 Sep 2020).

Performing the pandemic crisis is yet another opportunity for Orbán to use war rhetoric and emphasize the need to unite the people to fend off the crisis: “let's form the front line in preparation for our common battle” (Speech 805, 3 Apr. 2020). As such, even the coronavirus becomes a dangerous enemy to be fought and just as he has fought migration by militarizing Hungary's borders, Orbán declares a “military-style plan” to fight infections with “hospital commanders” in charge (Speech 803, 27 Mar. 2020). Orbán justifies his approach by claiming his experience in fighting off crises is crucial in successfully dealing with the health crisis as “the way of thinking which was effective in 2010 and pulled us out of trouble then will also be successful now” (Speech 815, 15 May 2020).

The crisis is performed by Orbán to rally the support of the people for his immediate and extraordinary policies—special emergency rules that give uncontrolled power to executive rule via decrees: “we cannot react quickly if there are debates and lengthy legislative and law-making procedures. And in times of crisis and epidemic, the ability to respond rapidly can save lives” (Speech 803, 27 Mar. 2020). For the same reason, the political opposition that criticizes the unprecedented power grab is once again portrayed as traitors of the nation, who do not stand with the country in times of trouble. For Orbán, opposing his government means endangering people's life by weakening crisis management capabilities (Speech 831, 3 Jul. 2020). Furthermore, Orbán accuses the left of anti-vaccination activity and spreading falsehood for its criticism of Hungary's purchase of Chinese and Russian vaccines, with no approval of EU health authorities (Speech 908, 16 Apr. 2020).

The EU continues to be portrayed as an enemy even amidst the pandemic for its criticism of Orbán's unchecked executive power and pandemic management. Transforming the real crisis into a performed crisis, Orbán claims that some EU countries have made “the vaccine a political issue” (Speech 906, 2 Apr 2020) and this is why Chinese and Russian vaccines acquired by him are not approved, despite the delays in obtaining western ones. Instead of saving people's life, the EU betrays the people since “everyone knows perfectly well that for the European Union [the question of purchasing vaccines] was a business question” (Speech 956, 28 Jan. 2022). Moreover, Orbán charges the EU for delaying Hungary's access to the pandemic recovery funds over rule of law violations that allegedly are imposed “because of the LGBTQ lobby” (Speech 939, 8 Oct. 2022) in Brussels that cannot accept Christian Hungary.

The start of the Ukrainian–Russian war in February 2022 provides yet another opportunity for Orbán to perform crisis the way it suits his interests. Being Putin's strongest European ally, Orbán is reluctant to condemn the Russian aggression and opposes sanctions claiming that Hungary will be affected negatively as “neighbors are the first to pay the price for sanctions” (Speech 960, 4 Mar. 2022). Instead, he blames NATO and the EU—Hungary's allies—for destroying the geopolitical status quo by encouraging Ukrainian membership instead ensuring that Ukraine remained a buffer zone “under the influence of Russia 50%, and the West 50%” (Speech 783, 6 Feb. 2020). The crisis of the war also allows Orbán to attack his domestic opposition before the upcoming elections, accusing it once again that it works against people's will because it wants to “send soldiers to fight the Russians” (Speech 959, 2 Mar. 2022), despite no such plans. In return, as a simple solution to the crisis, Orbán claims that only he and his government can secure Hungary from being dragged into the war.

Using the same populist discursive strategies that we have seen employed from 2010 onwards, Orbán exaggerates the supposed “wrongdoing” of the “others” and uses foul language to elicit a stronger emotional response from his followers: European elites and institutions are not only portrayed illegitimate for failing “people's will” but continue to be charged with being controlled by shadow armies. Allegedly, instead of elected politicians, media and NGO networks decide on mass immigration and “promotion of gender ideology” (Speech 938, 6 Oct. 2021) because “a shadow army of George Soros” (Speech 607, 4 May 2018) operates both in Hungary and Europe. Soros allegedly finances “fake civil society organization” (Speech 633, 27 Jul 2018) and the opposition to Orbán's regime. The opposition coalition for the 2022 elections is presented in a similar demeaning way to question its worth: “the Hungarian opposition … has been ground up and stuffed into a sausage … the Soros sausage” (Speech 856, 7 Oct. 2020).

According to Orbán, all the crises Hungary must face—be that the financial crisis in 2008, the migration crisis in 2015, or the pandemic in 2020—can be blamed on the failures of liberal governments. As such, for Orbán, “liberal democracy in that sense is over” (Speech 783, 6 Feb. 2020). Portraying his regime of an illiberal democracy as an innovation in democracy that will not only make Hungary great again but save Europe from decay, he identifies the followers of the old order (liberal democracy) as enemies using foul language as “its financial beneficiaries, the lazy, the idle and the slothful [who] all join forces to attack the innovators” (Speech 609, 10 May 2018). It is for the same reasons that Orbán claims no other prime minister or country has a reputation as bad as he has (Speech 702, 23 Mar 2019).

In sum, the 2018–2022 discourse performs a series of crises to enlist all critics of Orbán's regime as “dangerous others” that threaten the very foundations of Hungary. Liberals are signaled out as the target of all blame, irrespective of whether they are part of the domestic opposition or the European (and Western) scene. Orbán claims that “there are two attacks on Christian freedom. The first comes from within and comes from liberals … and there is an attack from outside, which is embodied in migration” (Speech 735, 27 Jul. 2019). Yet, the “culture war is not being fought in Hungary, but in Europe” (Speech 652, 4 Oct 2018). This way, the main threat is portrayed not as the internal opposition of the regime (already weakened by his authoritarian policies) but as coming from outside, via the liberal international community that is embodied by the EU. Opposing the EU thus stands for opposing everything liberal: immigration, multicultural secularism, or “gender ideology”; and supranational: the resettlement quota, a coordinated effort to fight coronavirus or a common stance against the Russian aggression.

Orbán's political discourse is a prime example of a right-wing ethno-populist narrative that performs crises to legitimize the ruling regime and its policies by distracting public opinion from policy choice to politics of identity. Ever since taking office in 2010, Orbán's discourse has been focused on discursively creating the image of existential crisis(es) and enemies of the people to be blamed for these crises by exaggerating threats faced by society. The discursive performance of crisis is constant, only the crises change, which results in a constant reconstruction of both the “self” and the “dangerous others,” with great flexibility, via processes of othering and blame attribution. Blame attribution is key to portraying “others” as violators of moral behavior and it is used to justify exclusionist policies, extreme measures, or denial of rights that are all at the center of illiberal politics that challenge liberal equality and pluralistic democracy with radicalized inclusionary and exclusionary criteria (Krekó and Mayer, 2015; p. 185).

Performing crisis enables Orbán discursively construct to his liking the image of “Hungarian people” as well as its enemies to be fought. While originally, economic difficulties position the working people against international capital and its former domestic elite, blame is also extended to the IMF and EU for demanding austerity measures. Next, the migration crisis pits an ethno-cultural self against the culturally and religiously different migrant, but it is again the EU and specific Western countries that allegedly bring migration to Hungary. Defining the self through ethnic particularism, conservative traditionalism, and Christian religion, everything multicultural and secular becomes an enemy: promoters of gender ideology threaten families, LGBTQ rights endanger children and public morals, while the Soros network allegedly wants to destroy Hungary. In turn, the coronavirus threatens people but once again the real enemies playing with people's lives are the political opposition and the EU for criticizing Orbán's pandemic management. Similarly, the Russian–Ukrainian war is a threat blamed on the EU and NATO, as well as the domestic opposition that allegedly wants to drag the country into war as opposed to Orbán's depiction of the self as “peace-loving people.”

It is the processes of discursive othering that establish the conflict lines between Hungary and its enemies. Orbán's discourse is highly adaptive in incorporating new topics and concepts, provided to him by contextual changes. Each new crisis breeds new “friends” and “foes”—only traditionalist Hungary's opposition to the EU remains constant: the Hungarian economy vs. foreign capital; IMF and the EU; ethnic Hungarians vs. immigrants and EU's refugee quota; Christianity vs. Islam and secular EU; traditional society vs. liberals in the EU; traditional family vs. gender or LGBTQ rights of the EU; and Hungary's national sovereignty vs. EU solidarity. With each crisis performed, conceptions of the “self” become more and more exclusionary, while the number and variety of enemies to be fought increases continuously, producing a never-ending spiral of radicalization that helps Orbán portray each crisis as an existential threat, where different issues become matters of fundamental questions of rights and wrongs, with no compromise possible.

At the same time, irrespective of the crisis that is performed, the discursive processes of othering center on different conceptions of Europe vis-à-vis the EU: while Hungary is always portrayed as a bastion and savior of traditional Europe and its Christian civilization, the EU is conceived in different ways as the archenemy—the most dangerous “other,” an empire of all (liberal) evil. Each crisis performed only deepens the conflict between Europe and the EU by adding new layers of disagreement. The European Union is mentioned three times more often than any other identifier in the discourse, which shows that Orbán's populist discourse is Eurosceptic at its core, claiming that all EU criticism and rule of law violation proceedings are revenge for Hungary safeguarding Christian Europe and its traditional values. In turn, this false discursive construct of the EU against Europe, no matter how detached from reality is, rallies people's support based on nostalgia and legitimates Orbán's political strategy to build illiberal democracy as the anti-thesis of the liberal world order. It also shields the regime from criticism both at home and abroad by allowing Orbán to act as European, while working against the EU.

Orbán continuously performs crises—real or imagined—because the constant “righteous battle” against the various enemies, empowered or embodied by the EU, can only be waged with unchallenged power concentration in the hands of the ruler. Unrestrained power allows for creating and transforming elites and authority, enabling constitutional changes, weakening of former power holders, promoting adversarial politics, favoring majoritarian norms at the expense of minorities, and weakening the European spirit by craving sovereignty. Orbán's grip on power is strengthened under the pretext of promoting a neoconservative ideology to save European civilization and the populist mobilization along the lines of “us” vs. “them” to label critics enemies and traitors or external foes of the national cause. While Orbán claims that it is the “will of people,” this is nothing but a drift to authoritarianism.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The open access publication fee was covered by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada (Agency award number: 611-2021-0015), awarded to Michael Carpenter.

I am grateful to NOPSA colleagues, especially Michael Carpenter for feedback on an earlier version of this paper.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2023.1032470/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1. The 2010–2022 major topics and their components over the three government periods. Source: Own computations, MAXQDA. Word combinations of two to five words are considered. All speeches of the respective period were compiled into a single document, words were lemmatized, and min. character length was set to 2. The software relies on English stop-words and only considers word combinations within a sentence or parts of sentences as defined by common separators (;, – () … []). To compile topics/themes, word context is explored, and context is set to 10 words ahead and 10 words for the selected word/phrase. For all word frequencies see Supplementary Table 2, for all word combination frequencies see Supplementary Table 3.

Supplementary Table 2. All word frequencies 2010–2022 discourse. Available electronically.

Supplementary Table 3. All word combination frequencies 2010–2022 discourse. Available electronically.

1. ^The first such party, MIÉP, the Hungarian Truth and Life Party, passed the 5% parliamentary threshold with a pan-Hungarian agenda, open racism, and anti-Semitism (Minkenberg, 2013). Following the demise of MIÉP, Jobbik became popular by pursuing an agenda of “gypsy crime” (Karácsony and Róna, 2011) and by founding a paramilitary wing, the Hungarian Guard Movement (Bíró Nagy et al., 2013). Our Homeland Movement (Hungarian: Mi Hazánk Mozgalom) was founded in 2018 by Jobbik dissidents, claiming the party gave up its radical roots.

2. ^All speeches are available online on the website of the PM's Office, although some websites have been archived; See https://2010-2014.kormany.hu/en/prime-minister-s-office/the-prime-ministers-speeches; https://2015-2019.kormany.hu/en/the-prime-minister/the-prime-minister-s-speeches; https://abouthungary.hu/speeches-and-remarks.

I rely on the official English translation of the PM's speeches; although the language used in the English translations is typically toned down, Hungarian versions can use more radical expressions. I am grateful to the anonymous reviewer for pointing out that some speeches were not officially translated and thus are missing from the analysis. The missing data should not alter substantially the analysis given the very high number of speeches analyzed.

To ease referencing the speeches, more than 800 entries, these are numbered for each government cycle, always starting with the first post-electoral victory speech available on the website: 2010–2014 Speeches 1–142; 2014–2018 Speeches 201–565; and 2018–2022 Speeches 601–956. To help better situate individual speeches in the overall discourse, all speech numbers are followed by the date of the speech: Speech 1 (1 July 2010); Speech 201 (6 June 2014); Speech 601 (8 April 2018).

3. ^The EU mandatory quota system was approved in September 2015 to transfer 160,000 refugees from Greece and Italy to other states under the EU's refugee burden sharing policy. Hungary was supposed to accept 1,294 refugees but refused and challenged the system at the European Court of Justice.

4. ^On the 12th of September, the European Parliament voted on the so-called Sargentini Report, condemning the anti-democratic turn of Hungary and initiating the procedure related to Article 7(1) of the Treaty on the European Union. The vote and even the report itself have drawn huge attention to the continuous democratic erosion in Hungary. (https://www.boell.de/en/2018/09/19/sargentini-report-its-background-and-what-it-means-hungary-and-eu).

Abdelal, R., Herrera, Y. M., Johnston, A. I., and Martin, T. (2001). Treating Identity as a Variable: Measuring the Content, Intensity, and Contestation of Identity. San Francisco: APSA.

Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso Books.

Bacchi, C. L. (1999). Women, Policy and Politics: The Construction of Policy Problems. SAGE Publications. Available online at: https://books.google.hu/books?id=fa19u0LsUKQC (accessed March 27, 2023).

Bárdi, N. (2013). Magyarország és a kisebbségi magyar közösségek 1989 után. A Múlt Jelene–a Jelen Múltja. Folytonosság És Megszakítottság a Politikai Magatartásformákban Az Ezredforduló Magyarországán 40. Debrecen: Debrecen University.

Bernhard, L., Kriesi, H., and Weber, E. (2015). “The populist discourse of the Swiss People's party,” in European Populism in the Shadow of the Great Recession, eds H. Kriesi and T. S. Pappas (Colchester : ECPR Press), 125–139.

Bíró Nagy, A., Boros, T., and Vasali, Z. (2013). “More radical than the radicals: the Jobbik party in international comparison,” in Right-Wing Extremism In Europe: Country Analyses, Counter Strategies and Labor Market Oriented Exit Strategies. Eds R. Melzer and S. Serafin. (Friedrich Ebert Stiftung), pp. 229–253.

Bozóki, A., and Hegedus, D. (2018). An externally constrained hybrid regime: Hungary in the European Union. Democratization 25, 1173–1189. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2018.1455664

Brubaker, R. (2017). Between nationalism and civilizationism: the European populist moment in comparative perspective. Ethnic Rac. Stud. 40, 1191–1226. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2017.1294700

Chong, D., and Druckman, J. N. (2007). Framing theory. Ann. Rev. Pol. Sci. 10, 103–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054

Christiansen, T., Jorgensen, K. E., and Wiener, A. (1999). The social construction of Europe. J. Eur. Public Policy 6, 528–544. doi: 10.1080/135017699343450

Csehi, R. (2019). Neither episodic, nor destined to failure? The endurance of Hungarian populism after 2010. Democratization, 26, 1011–1027. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2019.1590814

Csehi, R., and Zgut, E. (2021). “We won't let Brussels dictate us”: Eurosceptic populism in Hungary and Poland. Eur. Polit. Soci. 22, 53–68. doi: 10.1080/23745118.2020.1717064

Culic, I. (2009). Dual citizenship policies in Central and Eastern Europe. ISPMN Working Papers in Romanian Minority Studies 15, 1–40. Cluj Napoca: Institutul pentru Studierea Problemelor Minoritǎţilor Naţionale.

Engeli, I., Green-Pedersen, C., and Larsen, L. T. (2012). Morality Politics in Western Europe: Parties, Agendas and Policy Choices ed L. T. Larsen. (Palgrave Macmillan UK). doi: 10.1057/9781137016690

Enyedi, Z. (2016). Populist polarization and party system institutionalization: the role of party politics in de-democratization. Problems Post-Commun. 63, 210–220. doi: 10.1080/10758216.2015.1113883

Feinberg, M., and Willer, R. (2019). Moral reframing: a technique for effective and persuasive communication across political divides. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Comp. 13, e12501. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12501

Göncz, B., and Lengyel, G. (2021). Europhile public vs. Eurosceptic governing elite in Hungary? Intereconomics 56, 86–90. doi: 10.1007/s10272-021-0959-8

Hawkins, K. A. (2009). Is Chávez populist? Measuring populist discourse in comparative perspective. Comp. Polit. Stud. 42, 1040–1067. doi: 10.1177/0010414009331721

Hawkins, K. A., and Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018). Measuring populist discourse in the United States and beyond. Nat. Human Behav. 2, 241–242. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0339-y

Hawkins, K. A., and Silva, B. C. (2018). Textual analysis: Big data approaches. In The Ideational Approach to Populism (pp. 27–48). Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315196923-2

Hegedüs, D. (2019). Rethinking the incumbency effect. Radicalization of governing populist parties in East-Central-Europe. A case study of Hungary. Eur. Polit. Soc. 20, 406–430. doi: 10.1080/23745118.2019.1569338

Hungary Today (2019). Hungary Profits Most from EU Membership GNI-wise. Hungary Today. https://hungarytoday.hu/hungary-profits-most-from-eu-membership-gni-wise/ (accessed March 27, 2023).

Ignazi, P. (2003). Extreme Right Parties in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand. doi: 10.1093/0198293259.001.0001

Jagers, J., and Walgrave, S. (2007). Populism as political communication style: an empirical study of political parties' discourse in Belgium. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 46, 319–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x

Jenne, E. K. (2018). Is nationalism or Ethnopopulism on the rise today? Ethnopolitics 17, 546–552. doi: 10.1080/17449057.2018.1532635

Jensen, S. Q. (2011). Othering, identity formation, and agency. Qualit. Stud. 2, 63–78. doi: 10.7146/qs.v2i2.5510

Jung, J. H. (2020). The mobilizing effect of parties' moral rhetoric. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 64, 341–355. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12476

Karácsony, G., and Róna, D. (2011). The secret of Jobbik. Reasons behind the rise of the Hungarian radical right. J. East Eur. Asian Studies 2, 1.

Katsambekis, G. (2022). Constructing ‘the people' of populism: A critique of the ideational approach from a discursive perspective. J. Polit. Ideol. 27, 53–74. doi: 10.1080/13569317.2020.1844372

Kim, S. (2021). Because the homeland cannot be in opposition: analyzing the discourses of Fidesz and Law and Justice (PiS) from opposition to power. East Eur. Polit. 37, 332–351. doi: 10.1080/21599165.2020.1791094

Kováts, E., and Pető, A. (2017). “Anti-gender discourse in Hungary: a discourse without a movement,” in Paternotte, Anti-Gender Campaigns in Europe: Mobilizing against Equality ed R. Kuhar (pp. 117–131).

Kreitzer, R. J., Kane, K. A., and Mooney, C. Z. (2019). The evolution of morality policy debate: moralization and demoralization. The Forum. 17, 3–24. doi: 10.1515/for-2019-0003

Krekó, P., and Mayer, G. (2015). “Transforming Hungary–together? An analysis of the Fidesz–Jobbik relationship,” in Transforming the Transformation? The East European Radical Right in the Political Process. M. Minkenberg (Ed.) (Routledge), pp. 183–205. doi: 10.4324/9781315730578-9

Kriesi, H., and Pappas, T. S. (2015). Populism in Europe During Crisis: An Introduction. Colchester: ECPR Press.

Laclau, E. (2005). On Populist Reason. Verso. Available online at: https://books.google.hu/books?id=_LBBy0DjC4gC

Lakoff, G. (2002). Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think, Second Edition. University of Chicago Press. Available online at: https://books.google.hu/books?id=R-4YBCYx6YsC

Lazar, M. M. (2000). Gender, discourse and semiotics: the politics of parenthood representations. Discou. Soc. 11, 373–400. doi: 10.1177/0957926500011003005

Lazar, M. M. (Ed.). (2005). Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis: Gender, Power and Ideology in Discourse. Palgrave: Macmillan UK. doi: 10.1057/9780230599901

Meeusen, C., and Jacobs, L. (2017). Television news content of minority groups as an intergroup context indicator of differences between target-specific prejudices. Mass Commun. Soc. 20, 213–240. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2016.1233438

Minkenberg, M. (2013). From pariah to policy-maker? The radical right in Europe, West and East: between margin and mainstream. J. Contemp. Eur. Stud. 21, 5–24. doi: 10.1080/14782804.2013.766473

Moffitt, B. (2015). How to perform crisis: a model for understanding the key role of crisis in contemporary populism. Govern. Opposite. 50, 189–217. doi: 10.1017/gov.2014.13

Moffitt, B., and Tormey, S. (2014). Rethinking populism: politics, mediatisation and political style. Polit. Stud. 62, 381–397. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12032

Mucciaroni, G. (2011). Are debates about “morality policy” really about morality? Framing opposition to gay and lesbian rights. Policy Stud. J. 39, 187–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00404.x

Mudde, C. (2004). The populist Zeitgeist. Govern. Opposite. 39, 541–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

Mudde, C. (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Cambridge Core. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511492037

Mudde, C., and Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2013). Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism: comparing contemporary Europe and Latin America. Govern. Oppos. 48, 147–174. doi: 10.1017/gov.2012.11

Palonen, E. (2018). Performing the nation: the Janus-faced populist foundations of illiberalism in Hungary. J. Contemp. Eur. Stud. 26, 308–321. doi: 10.1080/14782804.2018.1498776

Ribera Payá, P. (2019). Measuring populism in Spain: content and discourse analysis of Spanish political parties. J. Contemp. Eur. Stud. 27, 28–60. doi: 10.1080/14782804.2018.1536603

Rooduijn, M., and van Kessel, S. (2019). Populism and Euroskepticism in the European Union., 1045. Oxford: OUP.

Ryan, T. J. (2014). Reconsidering moral issues in politics. J. Polit. 76, 380–397. doi: 10.1017/S0022381613001357

Said, E. W. (2014). “The clash of ignorance,” in Geopolitics. (Routledge), pp. 191–194). doi: 10.4324/9780203092170-31

Sata, R., and Karolewski, I. P. (2020). Cesarean politics in Hungary and Poland. East Eur. Polit. 36, 206–225. doi: 10.1080/21599165.2019.1703694

Schulz, A., Müller, P., Schemer, C., Wirz, D. S., Wettstein, M., Wirth, W., et al. (2018). Measuring populist attitudes on three dimensions. Int. J. Pub. Opinion Res. 30, 316–326. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edw037

Simonovits, B., Bernát, A., Szeitl, B., Sik, E., Boda, D., Kertesz, A., et al. (2016). The Social Aspects of the 2015 Migration Crisis in Hungary. Budapest: Tárki Social Research Institute (Vol. 155).

Stanley, B. (2008). The thin ideology of populism. J. Polit. Ideol. 13, 95–110. doi: 10.1080/13569310701822289

Stavrakakis, Y., and Galanopoulos, A. (2018). Ernesto Laclau and Communication Studies. Oxford: In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.590

Stavrakakis, Y., and Jäger, A. (2018). Accomplishments and limitations of the ‘new' mainstream in contemporary populism studies. Euro. J. Soc. Theor. 21, 547–565. doi: 10.1177/1368431017723337

Stavrakakis, Y., Katsambekis, G., Kioupkiolis, A., Nikisianis, N., and Siomos, T. (2018). Populism, anti-populism and crisis. Contemp. Poli. Theory, 17, 4–27. doi: 10.1057/s41296-017-0142-y

Szczerbiak, A., and Taggart, P. (2017). “Contemporary research on Euroscepticism: The state of the art,” in eds B. Leruth, N. Startin, and S. Usherwood, The Routledge Handbook of Euroscepticism (pp. 11–21). Routledge. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/75059/

Tóth, C. (2014). Full text of Viktor Orbán's speech at Băile Tuşnad. Tusnádfürdo: The Budapest Beacon, 29.

Wodak, R. (2007a). Discourses in European Union organizations: aspects of access, participation, and exclusion. Text and Talk. 27, 655–680. doi: 10.1515/TEXT.2007.030

Wodak, R. (2007b). “Doing Europe”: “The Discursive Construction of European Identities,” in Discursive Constructions of Identity in European Politics, ed R. C. M. Mole. (Palgrave Macmillan UK), pp. 70–94. doi: 10.1057/9780230591301_4