94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 13 October 2022

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.984310

This article is part of the Research TopicMind the Backlash: Gender Discrimination and Sexism in Contemporary SocietiesView all 11 articles

This paper explores the question of what explains public opinion of women empowerment in the Middle East and North Africa. Muslim societies have often been accused of conservatism toward empowerment, stripping women of equal access to education and opportunities. However, many predominantly Muslim societies in the MENA region seem to be on the way to implement change to provide women with more rights. Prior research points to exposure to diversity as a contributor to the acceptance of a more egalitarian role of women in society. This article analyzes different mechanisms of the exposure hypothesis and whether they contribute to predicting positive public perceptions of women empowerment in the region. The empirical analyses rely on public opinion data collected by the Arab Barometer in 2018–19. The descriptive findings suggest attitudinal differences across countries, but also significant gender gaps and divergences across core explanatory factors found under the umbrella of the exposure hypothesis, such as diverse urban living, keeping religion a private matter, and connecting with the world via social media. These factors seem important to shift people's minds and to pave women's long way to liberalization.

A decade after the Arab uprisings, the “euphoria of the [Arab] Spring” (Moghadam, 2014, p. 137) seems to have vanished. While initially praised to be an upheaval of change, especially in the light of improving women empowerment across the region, most demands in this respect have hardly been met (e.g., Glas and Spierings, 2020). Despite the mass presence of women in revolutionary efforts in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) in the twentieth century, including the Arab Spring, women remain excluded from the center of power (e.g., Moghadam, 2010, 2014; Bayat, 2013; Sadiqi, 2020). This represents a central dilemma for countries' democratization efforts but also for women around the globe: States experiencing advances in women's rights and political participation are more likely to transition and consolidate as democracies, as modernizing women are found to be among the main advocates and agents of democratization (see e.g., Moghadam, 2010, 2014, 2018). This is possible because notable advances in education, paid employment, and political representation have been achieved for women globally and specifically in the MENA region over the past decade (e.g., Walby, 2003; Seguino, 2007; Feather, 2020). Yet, further strengthening of the rights and roles of women seems necessary to put them into a more equal position, moving beyond establishing economic growth (Kabeer and Natali, 2013) or ensuring equal legal rights (Robbins and Thomas, 2018). Empowerment may start in people's minds, as public perceptions of the rights and roles of women in society a critical element of disentangling women empowerment in the region (Thomas, 2019). It is thus important to regularly monitor public perceptions toward women empowerment.

Using data from the Arab Barometer collected in 2018–2019, this article explores factors that may shift public perceptions of women's rights and roles to enable women empowerment in the region. The MENA region has been ascribed relative public support for women's social and political rights despite some cross-country differences (Coffé and Dilli, 2015; Robbins and Thomas, 2018; Thomas, 2019). However, Muslim societies have also been found to be substantively less supportive of gender equality compared to other cultural contexts (e.g., Norris and Inglehart, 2011; Tausch and Heshmati, 2016).

We examine whether exposure to diverse and liberal views may have a positive effect on opinions on women empowerment, outlining various mechanisms including education, employment, urban living, secularization, and the use of social media (e.g., Bolzendahl and Myers, 2004; Davis and Greenstein, 2009; Kroska and Elman, 2009; Thijs et al., 2019; Kitterød and Nadim, 2020). As such, we take stock of public perceptions of women's roles and rights in the MENA region and empirically investigate crucial mechanisms of the exposure hypothesis.

The article is structured as follows: We begin with theoretically defining women empowerment for this paper, linking the literature to challenges of operationalization. Next, we review factors that influence perceptions of women empowerment and discuss the exposure hypothesis and its mechanisms. We present our data and methods before reporting the results of our analysis. The article closes with a discussion of our findings, their implications for future research, and a critical evaluation of our study.

Alexander et al. (2016, p. 432) posit that “a theoretically driven definition of […] empowerment does not exist”. This appears to be the dominant finding in prior research describing empowerment as a buzzword or fuzzy concept (e.g., Kabeer, 1999; Cornwall and Brock, 2005; Batliwala, 2007; Mandal, 2013; Alexander et al., 2016; Cornwall, 2016) with an almost organically changing scope.

In simple words, empowerment refers to people's ability to make choices and gain control over their lives (Kabeer, 1999). In turn, these abilities should enable them to act on issues that they deem important to improve their lives, communities, and society (e.g., Mandal, 2013). As such, the idea of empowerment touches on multiple dimensions of life, including (but not exclusive to) social, political, and economic aspects (e.g., Kabeer, 1999; Mandal, 2013; Alexander et al., 2016). Many definitions of empowerment have derived from the development literature. Alexander et al. (2016) argue that the broadest view and most comprehensive approach has been proposed by the World Bank in which Malhotra et al. (2002) suggests that empowerment entails a process of change from a condition of disempowerment to that of agency and choice. This summarizes the view of Kabeer (1999) who maintains that, at a minimum, empowerment describes people's ability to make choices related to the available resources, taking agency in decision-making, and making prospective contributions, or achievements. These definitions therefore take an operationalist point of view allowing development agencies to evaluate empowerment at the macro-level.

This article focuses on public perceptions and argues that change begins in people's minds. Cornwall (2016) notes that the concept of empowerment traditionally referred to grassroots efforts to address unequal and unfair power dynamics. This corresponds with our conceptualization of empowerment. Following Cornwall (2016), we use the term empowerment to describe public perceptions of people's core rights and roles in society and to disentangle potential unjust power relations at that end. When we speak about perceptions of empowerment, we thus indicate public views on the rights and roles that enable people (in this case women) to live their lives by making their own free life choices and exercising control over their lives.

Adding “women” to the equation seems to further complicate a theoretical approximation of a definition of women empowerment. Malhotra and Schuler (2005, p. 72) point out that researchers often use women empowerment synonymous with related concepts, such as gender equality, women's status, and female autonomy. When we add women to our definition of perceptions of empowerment, we refer to public views on the rights and roles of women in society. We acknowledge that women empowerment encompasses some unique features, following Malhotra et al. (2002, p. 5), who suggest that women represent a cross-cutting category of individuals which overlaps with many other groups with protected characteristics, such as race. Further, women might be disempowered by gatekeepers who can be found within their own families, which may not apply in the same way for other disadvantaged groups.

Prior research finds that global, political women empowerment needs to be regarded in a triage of elite actors exercising authority; civil society actors challenging and engaging with these elites; and citizens formally engaging and participating in politics, to implement change (Alexander et al., 2016). Thus, to empower women, scholars indicate that systemic transformation of institutions that support patriarchal structures is required (Malhotra et al., 2002; see also Seguino, 2007; Moghadam, 2010; Kabeer and Natali, 2013; Kabeer, 2016). While our article follows this view, its starting point is different, as we propose that investigating public views on women empowerment—which should be foundational to reforming systemic characteristics that may foster patriarchal structures—is essential.

The absence of a clear definition of empowerment pushes scholars to take an operationalist point of view depending on the research at hand. While hard indicators of women empowerment are scarce, previous work has predominantly relied on public opinion data to measure whether citizens perceive women to have certain rights in various areas of life. For instance, scholars have frequently employed survey questions by the World Values Survey (WVS) on women's social and political rights, focusing on their role in politics, society, and the household. Norris and Inglehart (2011) utilize the WVS's Gender Equality Scale combining a battery of five items with ordinal agreement scales1. Following principal component analysis to empirically establish whether these questions speak to similar underlying concepts, they propose an additive index of women's equality.

Employing the same data set, Seguino (2007) expanded on the number of questions analyzed but distinguished the gender equality items from social attitudes unspecific to gender. Empirically, the analysis treats each survey question in isolation from the others and investigates potential attitudinal changes across time. Her work shows that women have gained more opportunities across the globe. However, it also indicates that women are—as one would anticipate—more supportive of women's rights compared to men.

A comparable approach is followed by Robbins and Thomas (2018) and Thomas (2019) who examine data collected by the Arab Barometer for MENA countries. Both studies also find that women are more supportive of their own agency compared to men. In addition, Thomas (2019) also presents aggregate descriptive data across time and disentangles further dimensions beyond differences in perceptions across women and men, including age, education, and urbanity. While support for women's rights has seemingly increased across the region2, she observes country differences as well as disparities across the different break variables. For instance, for many individual questions, better educated respondents and those living in urban areas appear to hold more liberal views.

Relying on WVS data, Feather (2020) explores perceptions of four individual dimensions of women empowerment descriptively, distinguishing women's personal legal empowerment from their social, economic, and political empowerment. As a proxy, each dimension is measured by an individual survey question3.

Moving beyond operationalizing perceptions of women empowerment by individual survey questions or presenting them as an additive index, Glas and Spierings (2020) apply Latent Class Analysis (LCA) on data from the Arab Barometer and WVS to empirically establish types of feminists across the MENA region. While analytically this might be a superior modeling approach, merging different data sets and using repeated cross-section over time may pose other challenges to the data analysis strategy.

All approaches are valid but take a slightly different angle on women empowerment. Individual questions allow tackling various issues but not a broader concept of empowerment, while an additive index allows predicting broader dimensions of women empowerment. LCA again takes a slightly different approach by defining groups of feminists. As our goal is to understand public perceptions toward the broader concept of women empowerment, we opt for an additive index which we discuss in more detail in the methods section.

One potential problem repeatedly described by scholars of the MENA region is the frequency with which ongoing projects ask the same questions in the surveys (e.g., Seguino, 2007; Thomas, 2019; Glas and Spierings, 2020). Funded projects may not be able to survey in the same number of countries or in regular time intervals. It is also noteworthy that asking some questions may be inappropriate in some country contexts at a particular point in time, resulting in incomplete data in repeated cross-sections and / or time series4,5.

The variety of measures applied to capture perceptions of women empowerment re-emphasizes the importance and clarity of definitions. However, it also demonstrates that scholarship aims to better conceptualize and operationalize women empowerment.

Women around the globe, but especially those in contexts that do not classify as WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic; Henrich et al., 2010a,b), face a continuous struggle for empowerment. Even though clarifications in the legal status of females as well as the mobilization of women specifically have helped shape the nature of the uprisings in various contexts (Moghadam, 2018), only few countries managed to maintain the momentum. Scholars have observed limits to the progress of women empowerment, especially in the MENA region following the Arab Spring (Glas and Spierings, 2020).

To understand the mechanism of women empowerment, it is thus important to be aware that the contextual influences on individuals' attitudes, serve as a strong determinant of individuals' perceptions on indicators of women empowerment, given prevailing norms at the societal level (e.g., Kitterød and Nadim, 2020). We thus begin by putting women empowerment into context before moving on to discussing individual level mechanisms.

In understanding diverse attitudes on gender equality, Inglehart (2020; see also Inglehart and Baker, 2000) identifies forces of modernization, including economic security, urbanization, mass education, occupational specialization, and expansions in technology and communication, as explaining diminishing differences in the perception of gender roles across contemporary societies. These developments reflect an increase in rationalization, bureaucratization, worldview pluralism, and the differentiation of religion and traditional authority from social and political institutions (Kasselstrand et al., 2023). As such, modernization processes are believed to drive pervasive global patterns of social and cultural changes, including secularization (e.g., Wilson, 1982; Bruce, 2002; Kasselstrand, 2019), democratization (e.g., Inglehart and Welzel, 2009), and a shift from a materialist focus on survival to values of self-expression (Inglehart et al., 2003).

Regarding gender, Inglehart (2020, p. 8) notes that patterns persist across diverse sociocultural and geographical contexts and explains that “the sharply contrasting gender roles that characterize all preindustrial societies almost inevitably give way to increasingly similar gender roles in advanced industrial society.” In essence, women empowerment has increased around the globe in two stages of modernization: First, industrialization is accompanied by rising female labor force participation and increasing educational opportunities for women (see also Kabeer and Natali, 2013). Second, women access managerial, high-status positions, and attain political power during a post-industrial phase, which a majority of the countries in the world have yet to reach (Inglehart et al., 2003; see also Seguino, 2007).

Although modernization drives changes in gender equality, other contextual factors intervene in this process. For example, a country's religious background accounts for a larger proportion of the variation in gender equality than its level of development (Welzel et al., 2002). Muslim majority countries have been found to be the least supportive of gender equality (e.g., Norris and Inglehart, 2011) and it has been argued that women empowerment is strongly interrelated with the rejection of Muslim traditions (Tausch and Heshmati, 2016). According to Inglehart et al. (2003, p. 71), “[i]slamic religious heritage is one of the most powerful barriers to the rising tide of gender equality.” However, observations from the Western world demonstrate that religious influence in societal power structures is not limited to Muslim majority countries. The issue of abortion in Ireland, Poland, and most recently the United States, serves as one example. It is therefore important to recognize that economic development alone is not sufficient to create positive conditions for women empowerment. Although the rejection of traditional forms of authority and the differentiation of religion from power structures and social and political institutions usually accompanies other indicators of modernization, such as economic growth and urbanization, it is not always the case.

While these contextual-level factors shape the environment in which individuals find themselves, it is beyond the scope of this article to investigate them in depth. The goal is rather to disentangle individual-level explanations of public perceptions of women empowerment, acknowledging the continuum in which they exist.

The importance of religious liberalism, women's education and employment, and urban living on shaping liberal views on gender equality has often been framed through the lenses of exposure and interest (e.g., Bolzendahl and Myers, 2004; Davis and Greenstein, 2009; Thijs et al., 2019): Gender egalitarian attitudes are either shaped by people's exposure to diverse worldviews through socialization or in response to individual interest. The latter indicates that people tend to hold more liberal views when it is in their best interest to do so. This perspective is often employed to describe why women are more likely to hold gender egalitarian views than men (Bolzendahl and Myers, 2004; Kroska and Elman, 2009; Thijs et al., 2019; Kitterød and Nadim, 2020). The former assumes that those frequently exposed to diversity will adopt more egalitarian values. This article focuses on exposure rather than interest, following the notion that encountering and engaging with others who may hold more positive attitudes on women empowerment is essential in understanding how such views are shaped.

H1: Exposure to diverse world views increases the likelihood of positive public perceptions of women empowerment.

Below we identify different mechanisms by which exposure to diversity may influence public perceptions of women empowerment. We summarize these in Table 1 along with their anticipated effect and provide more detailed discussions in the following.

In many Arab countries, the urban population has multiplied by two or three in the last half of the twentieth century (Chaaban, 2009), demonstrating that urban living is more attractive, especially to young people given the prospects of better educational and employment opportunities. In line with the modernization argument at the macro-level (Inglehart and Baker, 2000; Inglehart and Welzel, 2009; Inglehart, 2020), urban living should coincide with a cultural shift at a faster pace. Furthermore, at the individual level, the exposure argument may apply given the more diverse world views encountered in an urban as opposed to a rural setting (Bolzendahl and Myers, 2004): Urban living may expose women and men to well-educated, liberal, working women, where they interact, engage, and exchange ideas with each other, potentially leading to more liberal views on women empowerment (see Table 1, row 1).

Previous research has found a clear relationship between education and feminist views (e.g., Bolzendahl and Myers, 2004; Auletto et al., 2017; Kyoore and Sulemana, 2019). Thijs et al. (2019, p. 597) explain that “education has a liberalizing influence, transmitting ideas about diversity and equality, countering gender stereotypes, and increasing individuals' openness to alternative perspectives on the roles of women and men in the public and private spheres.” In other words, education is an avenue through which people encounter diverse and non-traditional worldviews. Education may be an especially powerful explanation in the formation of attitudes about gender equality, as individuals are particularly impressionable and open to re-evaluate their position on a variety of social and political issues during late adolescence and early adulthood (Krosnick and Alwin, 1989; Thijs et al., 2019). In their study of the MENA region, Auletto et al. (2017) find that it is the completion of secondary education specifically that serves as an important determinant of gender egalitarian views, arguing that further investment in education should be made (see Table 1, row 2).

Another means by which the exposure hypothesis applies is through employment in the paid workforce (Rhodebeck, 1996; Bolzendahl and Myers, 2004; Kitterød and Nadim, 2020). Working women—and men for that matter—who are interacting with others, including women, in a work context may gradually perceive change and adopt a more liberal view on the role and position of women in society. They may also be engaged in interactions with business partners around the globe, where gender equality may be further ahead, exposing them to views and behaviors that affect shifts in their attitudes toward women in general (see Table 1, row 3).

Furthermore, and coinciding with a macro picture, are arguments about the role of religion. Prior research has shown that MENA countries remain among the least secularized in the world (e.g., Eller, 2010; Kasselstrand et al., 2023). Religious people tend to hold more traditional or patriarchal views on gender issues (Zuckerman, 2009; Schnabel, 2016), a pattern that remains particularly strong among Muslims (Alexander and Welzel, 2011). Being raised religious and within a MENA context that overall tends to be characterized by strong religious authority thus exposes people to more traditional gender roles. Nonetheless, recent trends of secularization in the region can be observed (Abbott et al., 2017; Maleki and Tamimi Arab, 2020). Less than half of youth identify as religious in the countries surveyed by the Arab Barometer, ranging from 15 percent in Algeria to 42 percent in Iraq (Raz, 2019). In Iran, 60 percent do not pray regularly, two-thirds want separation between the state and religion, and more than a third drink alcohol (Maleki and Tamimi Arab, 2020). The above discussion suggests that the religion may be central to studying women empowerment (see Table 1, row 4).

The exposure argument may also apply to participation in online communities. The Internet is a unique and largely anonymous space for sharing and encountering views that deviate from mainstream societal norms. While this seems obvious, it is important to note that this offers opportunities in the MENA region, where traditional media are often subject to state control (Al-Saggaf, 2006; Thorsen and Sreedharan, 2019). Thorsen and Sreedharan (2019, p. 1125) explain:

“[t]he Internet enables people to do online what they cannot do offline […] In this context, the online public spaces that have emerged in Arab countries could be seen as examples of counter-publics, where women have been able to articulate political views […] Such activism features a lack of institutional and cultural norms: it is bodiless, which enables women to choose their identities, to express and write about marginalization and to challenge the system of patriarchy.”

Providing evidence of the impact of Internet activism and the online public sphere, Al-Saggaf and Weckert (2005) found that an online Saudi community devoted to political discussion had a clear effect on the social and political environment more broadly. Moreover, the Internet, and social media, in particular, have been instrumental in driving public action, not the least in relation to the Arab Spring (Salvatore, 2013). Online outputs have also shifted from primarily being written in English to a foreign, often Western audience, toward Arabs engaging on social media in their own language (Thorsen and Sreedharan, 2019), extending the possibility of online communication driving public opinion in the MENA region. In line with this, Moghadam (2019) observed that, especially for women, political engagement and participation has expanded with developments in communication, such as access to the Internet and social media, within and across countries (see Table 1, row 5).

Prior research on the Arab Spring also proposed that the youth were disproportionately more likely to participate in protest action during the Arab Spring ascribing them more liberal stance on empowerment in general (e.g., Hoffman and Jamal, 2012; Mulderig, 2013; Abbott et al., 2017). However, others warned that that it would be a mistake to characterize the protests as dominated by young users of the Internet and social media (Abbott et al., 2017)6.

Following the argument of the exposure hypothesis, i.e., diverse worldviews have a liberalizing effect on opinions on gender equality, this study postulates that there is a positive relationship between education, employment, social media usage, religious liberalism, and urban living with public perceptions on women empowerment. Our research systematically examines how these mechanisms might simultaneously affect perceptions of women's roles and rights. As such, it is our goal to provide a more comprehensive overview of the drivers of women empowerment in the MENA region a decade after the Arab uprisings.

To investigate attitudes toward women empowerment in the Middle East and North Africa, the analyses rely on cross-sectional data collected by the Arab Barometer (2019). The project conducted public opinion surveys based on random probability samples in 11 countries7 in the Middle East and North Africa (Total n = 25,407)8. The surveys were fielded using Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) between September 2018 and January 2019. For security reasons, some of the interviews had to be conducted using interviewer-assisted Paper and Pencil Interviewing (PAPI). This concerns the full sample in Yemen (n = 2,400), interviews in the Gaza Strip in Palestine (n = 972), and the Kurdish areas in Iraq (n = 120). The response rates varied by country from 45.1 percent in Tunisia to 89.0 percent in Palestine. Whenever possible and suggested by the American Association for Public Opinion Research, Response Rate I was calculated9.

The questionnaire asked various questions on politics and society in the region, including a battery on women's political and social rights. The dependent variable is a standardized additive index of women's rights in the MENA region based on six questions that capture: (1) Support for a women's quota in elections; (2) acceptance of women as state leaders; (3) equal rights for women to make the decision to divorce; (4) rejection of the assumption that men are better political leaders; (5) rejection of the statement that men's education is more important than that of women, and (6) that husbands always having the final say in the household. All items were measured on a 4-point (dis-)agreement scale and recoded into binary variables, where 1 indicated the more liberal outcome and 0 the more conservative one10. Subsequently, an additive index was created and standardized to a range from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate more liberal views on perceived women empowerment.

One core explanatory variable predicting public perception toward women empowerment is religious liberalism. The Arab Barometer asked a series of questions about attitudes toward involvement of Islam in the political sphere including (1) whether or not religious leaders should not interfere with elections; (2) religious practice should be a private matter; (3) Islam does not require women to wear a hijab; (4) the country is better off with religious leaders in government; (5) Religious leaders should interfere with government decisions; and (6) that non-Muslims rights should be inferior to those of Muslims11. Similar to the women empowerment index, we recoded these items into dichotomous variables, where 1 indicated the liberal and 0 the conservative view on political Islam. Next, we created an additive index of the six items and standardized it to range from 0 to 1. Higher values indicate a higher level of religious liberalism.

As an indicator of connectedness with the global world, we employ two variables that focus on online participation. The Arab Barometer asked respondents how many hours they spent on social media utilizing an ordinal scale. We recoded the variable in a way that we end up with a dichotomous measure that is equal to 0 if the respondent reported that they do not use social media (0 hours per day), and 1 if they reported using social media daily (up to two hours or more). As the social media question was filtered on a survey item capturing whether or not people use the Internet and as such excluded all respondents who reported they never use the Internet, we also coded these respondents as 0 (=do not use social media as they are also not using the Internet).

The second social media indicator is the number of social media channels (NSMC) the respondents reported using. Overall, the survey captured whether people mentioned Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram, or Snapchat. We added up these items, so that our recoded measure indicates how many of these social media channels respondents employ. The overall range of our variable is 0–7, where 0 indicates they use none of these seven social media channels and 7 that they use all of these.

In addition, we account for the employment status, capturing whether respondents are employed (=1) or not (=0); where the respondents live, i.e., in urban (=1) or rural environments (=0)12; respondents' self-reported level of education (primary=0, secondary=1, or higher=2); their age in years; and their gender (women = 1; men = 0)13.

To avoid potential multicollinearity problems, we explored correlations of all indicators. The correlation coefficients displayed weak, but statistically significant associations.

We begin by presenting some descriptive results, looking at the mean scores on the perceptions of women empowerment measure by country as well as by gender; urbanity; education; employment; religious liberalism; and social media usage. Next, we estimate a series of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regressions starting with the sociodemographic model, and subsequently adding all explanatory variables individually. This allows us to observe any changes in the explained variance for each of the independent variables. We calculate clustered standard errors accounting for the intragroup correlation by country. All analyses presented apply poststratification weights by country provided by the Arab Barometer14.

Overall, the population across the MENA region is relatively supportive of women empowerment, with more than half falling above the average score of 59.015. However, there is noteworthy cross-country variation. Figure 1 plots the mean score of perceived women empowerment by country, with higher scores indicating more liberal views. On average, the Sudanese ( = 48.3) score lowest on the perception of women empowerment index, while the Lebanese appear to have the most liberal views on women empowerment ( = 68.5).

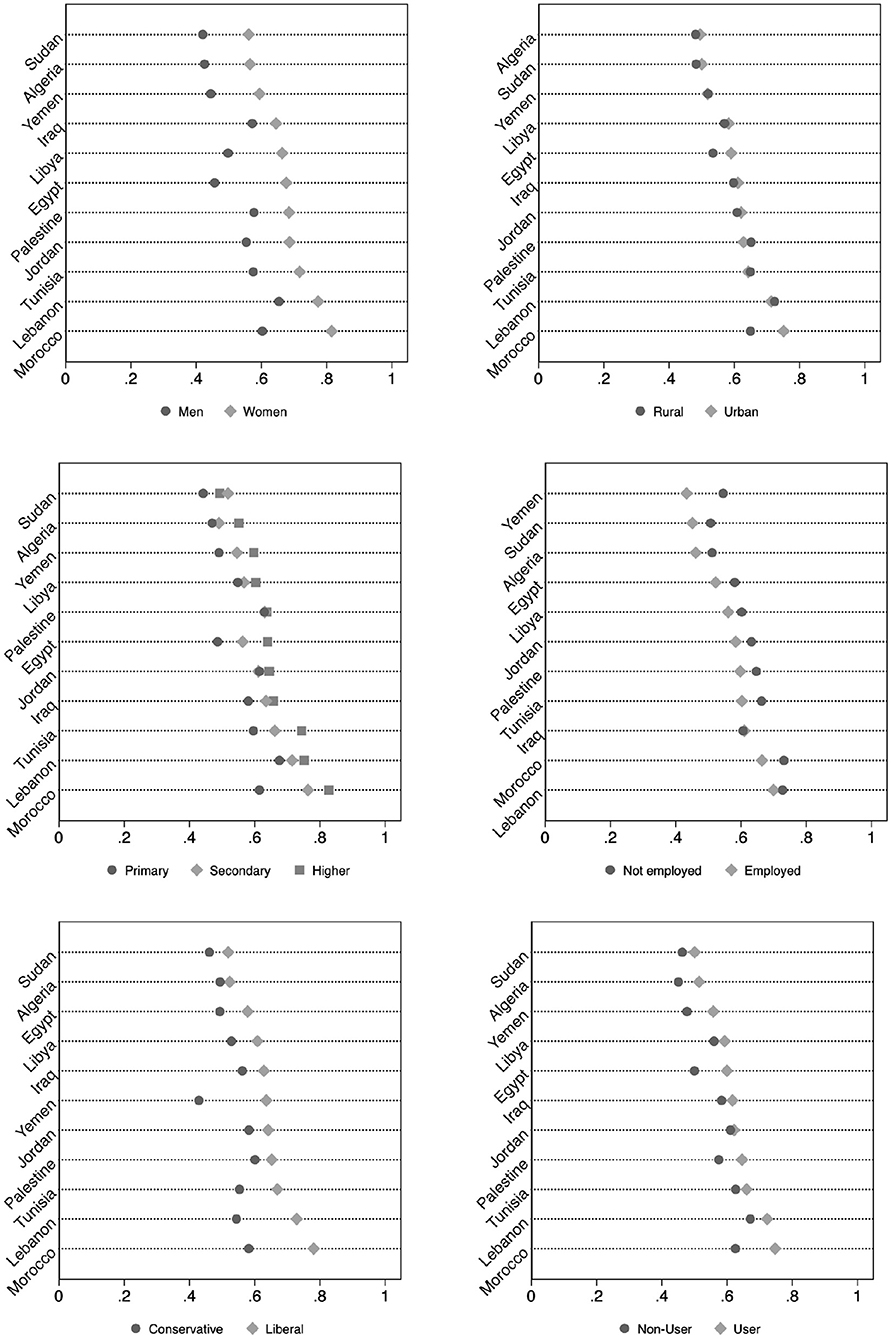

Some variation in views on women empowerment may be due to other factors, such as gender; urban living; education; employment status; religious liberalism16; or social media usage. Figure 2 thus plots the mean score of perceptions of women empowerment across countries by these features.

Figure 2. Mean perception of women empowerment in the MENA region by gender, urbanity, education, employment status, religious liberalism, and social media usage. Estimates weighted.

The top left graph presents the differences in average scores on women empowerment by gender. Unsurprisingly, we observe statistically significantly higher support for women empowerment among women compared with men across countries17. The largest differences can be observed in Egypt (Δxw−xm = −0.23, t = −21.23, df = 1,986; p-value < 0.01), the smallest difference in Iraq (Δxw−xm = −0.07, t = −8.05, df = 2,345; p-value < 0.01).

Looking at the variation by urbanity (top right graph), the picture painted is more diverse: In most countries, there is no statistically significant difference between urban and rural locations in the average score on women empowerment, with the exception of Morocco (Δxu−xr = −0.09, t = −6.32, df = 1,568; p-value < 0.01), Egypt (Δxu−xr = −0.05, t = −4.54, df = 1,986; p-value < 0.01), and Sudan (Δxu−xr = −0.03, t = −2.22, df = 1,662; p-value < 0.05), where those in urban areas are statistically significantly more likely to display more liberal views on women empowerment.

The general patterns for educational attainment are presented on the left-hand side in the middle row of Figure 2. It suggests that those with higher educational levels score higher on the women empowerment index, compared to those with primary and secondary education. The exceptions are Sudan, where those with secondary education seem to score higher compared to those with higher education, and Palestine, where no visible difference in average mean scores on women empowerment can be observed18.

The graph on the right in the middle row shows the patterns for employment status. The findings indicate statistically significant group differences across those employed vs. those not employed in all country contexts but Iraq. The largest difference can be observed in Yemen ( = 0.07, t = 4.91, df = 2,252; p-value < 0.05) and Sudan ( = 0.07, t = 4.74, df = 1,637; p-value < 0.01).

The bottom left graph displays the differences in mean perceptions on women empowerment by religious liberalism. It is noteworthy that those with more liberal views on the relationship between religion and the state are also statistically significantly more likely to score higher on the women empowerment index. The biggest differences can be observed in Yemen ( = −0.20, t = −16.08, df = 2,130; p-value < 0.01), Morocco ( = −0.19, t = −11.38, df = 1,074; p-value < 0.01), and Lebanon ( = −0.19, t = −11.71, df = 2,204; p-value < 0.01). The smallest, yet statistically significant differences, are seen in Egypt ( = −0.05, t = −3.86, df = 1,581; p-value < 0.01) and Algeria ( = −0.05, t = −4.37, df = 1,628; p-value < 0.01).

Finally, the bottom graph on the right displays the patterns across social media usage. The analysis suggests statistically significant group differences except in Jordan. The biggest differences can be observed in Morocco ( = −0.13, t = −8.57, df = 1,511; p-value < 0.01) and Yemen ( = −0.13, t = −8.83, df = 2,229; p-value < 0.01); the smallest, yet statistically significant difference in Iraq ( = −0.03, t = −3.05, df = 2,333; p-value < 0.01).

In sum, the descriptive results presented above seem to give a first indication that some of the mechanisms discussed in the literature review may indeed be relevant to predict perceptions of women empowerment in the MENA region.

Next, we estimated a series of models to test our hypotheses in a multiple regression environment. To recap, we begin with a socio-demographic model accounting for intragroup clustering by country calculating clustered standard errors. We do not present a graph for this model. We then add our explanatory variables testing the urbanity, employment, religious liberalism, and social media arguments step-by-step. The full modeling process is documented in Supplementary Table A1.

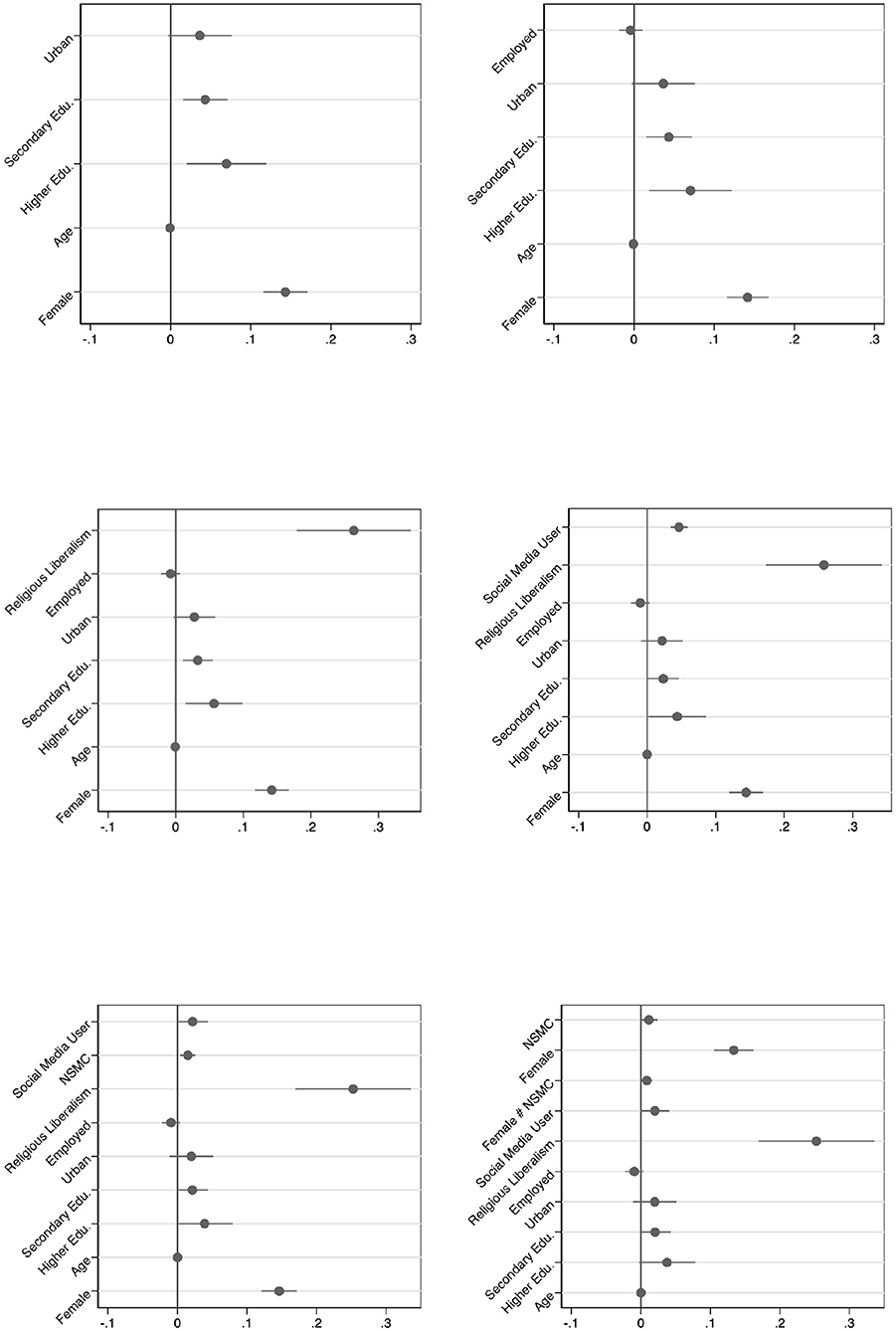

The top left graph of Figure 3 displays coefficients of the socio-demographic model plus urbanity, suggesting that women, better educated, and individuals who live in urban areas tend to be more likely to hold more positive views on women empowerment. We do not identify an age effect.

Figure 3. Coefficient plot of predictors of women empowerment in the MENA region. Whiskers represent 95%-confidence intervals. Estimates weighted.

The top right graph tests the employment argument. While the patterns identified in the previous model hold, the results do not display an employment effect as we had hypothesized.

The graph on the left-hand side in the middle row of Figure 3 adds the indicator for religious liberalism and displays a strong, positive impact on perceived women empowerment, holding all other variables constant. All other effects hold with small differences in the strength of the coefficients.

The graph on the right-hand side in the middle row of Figure 3 adds the first variable on social media usage to the equation. We make one important observation here: All but one previous relationship seems to hold when adding this variable, i.e., that of urbanity.

Admittedly, urban living only displayed a small positive impact at the 0.1-level of statistical significance. However, it appears that this is absorbed by adding the social media usage variable. We may carefully argue that the digital age allows those living in rural and urban areas to be exposed to the interconnected world, so perhaps where people live is no longer that important for the development of liberal attitudes.

We now turn to the bottom row of Figure 3, where the left graph adds the NSMC used to our regression model. We find a positive and statistically significant impact of NSMC on women empowerment. We make further observations here: The education effects seem to change somewhat. While the strength of both secondary and higher education in comparison to primary education remain similar to the previous models, the level of statistical significance drops to 90%. Further, we observe that the social media usage variable loses in strength and significance as well. It remains relevant with 90% confidence.

Our final model includes an interactive term between NSMC and gender, as the literature review pointed to the increased usage of social media by women to provide a safe and potentially anonymous way to express themselves (Thorsen and Sreedharan, 2019). Indeed, we do find a positive effect of the interactive term, suggesting that engaging in multiple social media channels has a stronger effect on liberal views for women than it does for men. Moreover, the individual effects remain. This supports the argument above. All other patterns identified in the previous model hold.

We plot the marginal effect of the interactive term with 95%-confidence intervals in Figure 4, following the advice by Brambor et al. (2006) to visually inspect the multiplicative term. The plot shows that for both women and men the probability of more liberal views on women empowerment increases the more social media channels they use. Further, we observe that the level of support for women empowerment for women and men is different throughout. As the confidence intervals for the line for women and men are not overlapping, we conclude that the statistically significant effect applies for the full scale of social media channels. This is in line with the suggestion that Moghadam (2019) makes about engagement, especially that of women, having expanded across counties. We interpret this as support for the social media mechanism of the exposure hypothesis, where more exposure to the diverse information should improve people's support for more egalitarian rights. Given the higher level for women in general, we would expect the level for women to be higher than for men, which the Figure 4 suggests19.

This article took stock of public perceptions of women empowerment in the Middle East and North Africa and studied mechanisms underlying the exposure hypothesis positing that exposure to diverse world views will have a liberalizing effect on public perceptions of women's rights and roles. Acknowledging the challenges in defining and measuring “true” empowerment of women, we conceptualize perceptions of women empowerment as self-reported attitudes toward questions of women's rights and roles. We argue that empowerment starts in people's minds and that more egalitarian views on women's rights and roles will be central to enabling women to make their own choice and take control over their own lives.

The article focuses on a region that struggles with the stigma of fostering and protecting patriarchal structures, which is often ascribed to prevalent conservative religious beliefs (Inglehart et al., 2003; Alexander and Welzel, 2011; Tausch and Heshmati, 2016). By analyzing data collected by the Arab Barometer in 2018–19, we were able to simultaneously test which mechanisms are at play for the wider region while controlling for country clustering in the data.

Empirically, we find that public perceptions on women empowerment show some indications toward liberalization. On average, Arab publics hold a relatively positive view on women empowerment. However, there is still a leeway for improvement, as we observe substantive cross-country variation, in line with the findings of previous studies (e.g., Coffé and Dilli, 2015). Exposure to diverse worldviews especially via the Internet and social media and by separating religious traditions and potential resulting constrains from social and political lives may contribute to more liberalization (see also Zuckerman, 2009; Alexander and Welzel, 2011; Schnabel, 2016; Tausch and Heshmati, 2016). We also find some support for the pathway of educational attainment, following the previous literature on the impact of education (e.g., Bolzendahl and Myers, 2004; Auletto et al., 2017; Kyoore and Sulemana, 2019). While we identify that urban living is also a predictor of more liberal views on women empowerment, it appears that digitalization replaces its impact. When testing the exposure argument of the digital world, looking at social media usage and the number of channels used, the effect of urban living seems to be absorbed by these variables supporting previous claims proposing that digitalization provides women with a new anonymous avenue for activism (Thorsen and Sreedharan, 2019). However, contrary to arguments made about exposure through employment (e.g., Rhodebeck, 1996; Bolzendahl and Myers, 2004; Kitterød and Nadim, 2020), we do not find that being employed has an impact on perceptions of women empowerment.

Overall, we find some support for the exposure hypothesis with the exception of employment and urbanity—at least once controlling for social media usage. This support is evident in three core mechanisms: education, religious liberalism, and social media usage. Public opinion is more susceptible to positive views on women empowerment for individuals displaying a higher educational attainment, more liberal views on religion, and frequent engagement on social media using a variety of different channels. These findings may help policy makers, charities, and the international community to optimize their campaigns to shift people's minds, suggesting that access to education, revisiting of religious traditions, and well-placed social media campaigns may help to address empowerment issues.

Our research has some limitations: Taking stock at one particular point in time does not allow us to systematically track the shifts in public opinion over time. As many scholars have pointed out before, the field lacks high-quality time-series data of questions tapping into the same dimensions of women empowerment (e.g., Feather, 2020; Glas and Spierings, 2020). Many projects only infrequently ask the same item in batteries on the role of women in society and politics. We also acknowledge the difficulty of asking about some items in public opinion surveys. For instance, it is almost impossible to capture freedom of violence or even attitudes about violence accurately and effectively given the sensitivity of this issue (see e.g., Kabeer, 2016). Moreover, our study focuses on self-reported exposure through education, employment, lifestyle choices, and social media use. However, one question remains unattended too, that is how contextual effects influence public perceptions. For instance, macro-indicators of human development, globalization, but also institutions (see e.g., Coffé and Dilli, 2015, testing contextual effects on participation in Muslim countries). Future research may also wish to further explore what kinds of information individuals have actually been exposed to by linking data on specific media content to public opinion data (Weaver et al., 2019; Horvath et al., 2022).

While public perceptions across the MENA region seem to have shifted toward a positive view on women empowerment, the ambitious research agenda into women's rights and roles and diverse findings are also indications that it is still a long way to liberalization and gender equality in the region. We conclude that exposure to diverse views should contribute to further strengthen women in this region on their pathway to empowerment.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.arabbarometer.org/survey-data/data-downloads/.

Neither ethical review and approval nor written consent to participate in the study were required, given the research employed secondary data. This is in accordance with the local and institutional requirements.

KT: idea and analysis. KT and IK: theoretical framework, design, manuscript draft, and final approval of the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.984310/full#supplementary-material

1. ^These questions ask as to whether respondents agree or disagree with statement prompting that men are better political leaders; if men should be prioritized on the job marked when jobs are scarce; if university education is more important for men than women; whether women need to have children to be fulfilled; and whether they approved of single women bringing up children.

2. ^However, the overall numbers reported are not directly comparable given that a different set of countries from the region participated across the years (Thomas, 2019).

3. ^Personal legal empowerment: “It is justifiable for a man to beat his wife”; social empowerment: “University education is more important for a man than a woman”; economic empowerment: “when jobs are scarce men should have priority for a job”; political empowerment: “Men make better political leaders” (Feather, 2020).

4. ^Thinking about the region studied, it should also be mentioned that many contexts are non-democratic, which poses challenges to the survey infrastructure but also raises the question who collects the data and what administrative hurdles and control governments may have during the approval process, i.e., asking projects to remove certain questions for political reasons.

5. ^A related issue is the accuracy with which women's rights questions can be measured in a survey environment. Certain questions, e.g., personal questions, may be prone to misreporting (Tourangeau et al., 2000; Krumpal, 2013) especially given potential underlying gatekeeper challenges within the household. Moreover, respondents may perceive any evaluative task that is not a traditional survey question as suspicious. Furthermore, countries in the global South may not have the capacity to implement such tests sufficiently, given potential ongoing interstate conflicts and/or underdeveloped infrastructures. Moreover, linking potential survey data might induce bias in samples if sub-populations of the intended sample systematically drop out affecting the representativeness of the study. To circumvent this issue, Nillesen et al. (2021) suggest moving away from observational survey data capturing explicit attitudes toward measuring implicit attitudes on women empowerment in the MENA region by employing so-called Implicit Attitude Tests (e.g., Ksiazkiewicz and Hedrick, 2013). While measuring implicit attitudes may reduce risks of misreporting, as the measures are based on affect, other problems may influence the accuracy of measurement.

6. ^While we do not present a specific mechanism for age in Table 1, we consider age in our empirical tests.

7. ^In alphabetical order: Algeria (n = 2,332), Egypt (n = 2,400), Iraq (n = 2,462), Jordan (n = 2,400), Lebanon (n = 2,400), Libya (n = 1,962), Morocco (n = 2,400), Palestine (n = 2,493), Sudan (n = 1,758), Tunisia (n = 2,400), Yemen (n = 2,400).

8. ^For detailed information about the Arab Barometer, see www.arabbarometer.org (accessed April 29, 2020).

9. ^For detailed information on response rates, see Methodology Report provided on the Arab Barometer's webpage: https://www.arabbarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/ABV_Methods_Report-1.pdf accessed May 27, 2022).

10. ^For some items (strong) agreement in the battery indicated the more liberal outcome (Q601A: “Some people think in order to achieve fairer representation a certain percentage of elected positions should be set aside for women”; Q601_1: “A woman can become President/Prime Minister of a Muslim country”; Q601_14: “Women and men should have equal rights in making the decision to divorce”. As a result, we collapsed (strong) agreement as 1 (liberal) and (strong) disagreement as 0 (conservative). For other items (strong) agreement in the battery indicated the more conservative outcome (Q601_3: “In general, men are better at political leadership than women”; Q601_4: “University education for males is more important than university education for females”; Q601_18: “Husbands should have the final say in all decision concerning the family”). Consequently, we collapsed (strong) disagreement as 1(liberal) and (strong) agreement as 0 (conservative).

11. ^As these questions were only asked of Muslims, we restricted the analysis to the Muslim population. Overall, 93 percent of the sample population self-identify as Muslim, only 6 percent as Christians, the remaining one percent as other.

12. ^The original variable also included respondents interviewed in refugee camps in Palestine (total n = 2,493), as the classification of these into urban and rural areas is unclear, we decided to drop these respondents (n = 270) from the analysis.

13. ^We also produced models that included a variable capturing whether or not respondents are form an above- or below-median income household. Due to severe loss in case numbers in addition to the fact that we did not hypothesize an effect of this variable, it was excluded in the final models.

14. ^The weights were calculated for each country. Base weight is the household size. Weights were calculated on the basis of age, gender, region, and – if applicable – religious sect. The latter was the case in Lebanon.

15. ^We dichotomized the women empowerment index at its mean to calculate this weighted estimate.

16. ^Note that the religious liberalism index was dichotomized to create Figures 1, 2. In order to achieve this, the index was split at its mean: Values below the average score indicate religious conservatism; values above the average score religious liberalism.

17. ^T-tests by country rejected the null hypothesis of the t-statistic that the means scores by gender are the same. The results can be provided upon request.

18. ^Detailed results of the t-tests when testing each of the educational dimensions against the other two can be provided upon request.

19. ^We also tested the multiplicative term of gender and social media usage, which did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance.

Abbott, P., Teti, A., and Sapsford, R. (2017). Youth and the Arab Uprisings: The Story of the Rising Tide. The Arab Transformations. Aberdeen: The University of Aberdeen Press.

Alexander, A. C., Bolzendahl, C., and Jalalzai, F. (2016). Defining women's global political empowerment: theories and evidence. Sociol. Compass 10, 432–441. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12375

Alexander, A. C., and Welzel, C. (2011). Islam and patriarchy: how robust is Muslim support for patriarchal values? Int. Rev. Sociol. 21, 249–276. doi: 10.1080/03906701.2011.581801

Al-Saggaf, Y. (2006). The online public sphere in the Arab world: The war in Iraq on the Al Arabiya website. J. Comput-Mediat. Comm. 12, 311–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00327.x

Al-Saggaf, Y., and Weckert, J. (2005). “Political online communities (POCs) in Saudi Arabia”, in Encyclopaedia of Developing Regional Communities With ICT, eds S. Marshall, W. Taylor, and X. Yu (Hershey, PA: Idea Group Reference), 557–563.

Arab Barometer (2019). Arab Barometer Wave V [Data File, file last updated: 21 September 2020]. Available online at: www.arabbarometer.org (accessed June 20, 2022).

Auletto, A., Kim, T., and Marias, R. (2017). Educational attainment and egalitarian attitudes toward women in the MENA region: insights from the Arab Barometer. Curr. Issues Compar. Educ. 20, 45–67.

Batliwala, S. (2007). Taking the power out of empowerment–an experiential account. Dev. Pract. 17, 557–565. doi: 10.1080/09614520701469559

Bayat, A. (2013). The Arab Spring and its surprises. Dev. Change 44, 587–601. doi: 10.1111/dech.12030

Bolzendahl, C. I., and Myers, D. J. (2004). Feminist attitudes and support for gender equality: opinion change in women and men, 1974–1998. Soc. Forces 83, 759–789. doi: 10.1353/sof.2005.0005

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., and Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: improving empirical analyses. Polit. Anal. 14, 63–82. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpi014

Chaaban, J. (2009). Youth and development in the Arab countries: the need for a different approach. Middle East. Stud. 45, 33–55. doi: 10.1080/00263200802547644

Coffé, H., and Dilli, S. (2015). The gender gap in political participation in Muslim-majority countries. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 36, 526–544. doi: 10.1177/0192512114528228

Cornwall, A. (2016). Women's empowerment: what works? J. Int. Dev. 28, 342–359. doi: 10.1002/jid.3210

Cornwall, A., and Brock, K. (2005). What do buzzwords do for development policy? A critical look at ‘participation',‘empowerment'and ‘poverty reduction'. Third World Q. 26, 1043–1060. doi: 10.1080/01436590500235603

Davis, S. N., and Greenstein, T. N. (2009). Gender ideology: components, predictors, and consequences. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 35, 87–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115920

Eller, J. (2010). “Atheism and secularity in the Arab world,” in Atheism and Secularity: Global Expressions, Vol. 2, ed P. Zuckerman (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger), 113–137.

Feather, G. (2020). “Cultural change in North Africa: the interaction effect of women's empowerment and democratization”, Double-Edged Politics on Women's Rights in the MENA Region, eds H. Darhour, and D. Dahlerup (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 97–130.

Glas, S., and Spierings, N. (2020). “Changing tides? On how popular support for feminism increased after the arab spring”, in Double-Edged Politics on Women's Rights in the MENA Region, eds H. Darhour, and D. Dahlerup (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 131–154.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., and Norenzayan, A. (2010a). Most people are not weird. Nature 466, 29. doi: 10.1038/466029a

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., and Norenzayan, A. (2010b). The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 33, 61–83. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Hoffman, M., and Jamal, A. (2012). The youth and the Arab spring: cohort differences and similarities. Middle East Law Governance 4, 168–188. doi: 10.1163/187633712X632399

Horvath, L., Banducci, S., Blamire, J., Degnen, C., James, O., Jones, A., et al. (2022). Adoption and continued use of mobile contact tracing technology: multilevel explanations from a three-wave panel survey and linked data. BMJ Open 12, e053327. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053327

Inglehart, R. (2020). Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, R., and Baker, W. E. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. Am. Sociol. Rev. 65:19–51. doi: 10.2307/2657288

Inglehart, R., Norris, P., and Ronald, I. (2003). Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Inglehart, R., and Welzel, C. (2009). How development leads to democracy: what we know about modernization. Foreign Affairs 88, 33–48.

Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: reflections on the measurement of women's empowerment. Dev. Change 30, 435–464. doi: 10.1111/1467-7660.00125

Kabeer, N. (2016). Gender equality, economic growth, and women's agency: the “endless variety” and “monotonous similarity” of patriarchal constraints. Fem. Econ. 22, 295–321. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2015.1090009

Kabeer, N., and Natali, L. (2013). Gender Equality and Economic Growth: Is There a Win-Win? Brighton: Institute for Development Studies. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/j.2040-0209.2013.00417.x (accessed June 27, 2022).

Kasselstrand, I. (2019). Secularity and irreligion in cross-national context: a nonlinear approach. J. Sci. Study Relig. 58, 626–642. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12617

Kasselstrand, I., Zuckerman, P., and Cragun, R. (2023). Beyond Doubt: The Secularization of Society. New York: New York University Press.

Kitterød, R. H., and Nadim, M. (2020). Embracing gender equality. Demogr. Res. 42:411–440. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2020.42.14

Kroska, A., and Elman, C. (2009). Change in attitudes about employed mothers: exposure, interests, and gender ideology discrepancies. Soc. Sci. Res. 38, 366–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.12.004

Krosnick, J. A., and Alwin, D. F. (1989). Aging and susceptibility to attitude change. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57, 416–425. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.3.416

Krumpal, I. (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: a literature review. Qual. Quant. 47, 2025–2047. doi: 10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9

Ksiazkiewicz, A., and Hedrick, J. (2013). An introduction to implicit attitudes in political science research. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 46, 525–531. doi: 10.1017/S1049096513000632

Kyoore, J. E., and Sulemana, I. (2019). Do educational attainments influence attitudes toward gender equality in Sub-Saharan Africa? Forum Soc. Econ. 48, 311–333. doi: 10.1080/07360932.2018.1509797

Maleki, A., and Tamimi Arab, P. (2020). Iranians' Attitudes Toward Religion: A 2020 Survey Report. Netherlands: Group for Analyzing and Measuring Attitudes in Iran.

Malhotra, A., and Schuler, S. R. (2005). “Women's empowerment as a variable in international development”, in Measuring Empowerment: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives, ed D. Narayan-Parker (Washington, DC: World Bank Publications), 71–88.

Malhotra, A., Schuler, S. R., and Boender, C. (2002). Measuring Women's Empowerment as a Variable in International Development. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Moghadam, V. M. (2010). “Gender, politics, and women's empowerment,” in Handbook of Politics, eds K. T. Leicht, and J. C. Jenkins (New York, NY: Springer), 279–303.

Moghadam, V. M. (2014). Modernising women and democratisation after the Arab Spring. J. North African Stud. 19, 137–142. doi: 10.1080/13629387.2013.875755

Moghadam, V. M. (2018). Explaining divergent outcomes of the Arab Spring: the significance of gender and women's mobilizations. Polit. Groups Identities 6, 666–681. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2016.1256824

Moghadam, V. M. (2019). Social Transformation in a digital age: women's participation in civil and political domains in the MENA region. IEMed. Mediterranean Yearbook 2019, 140–145.

Mulderig, M. C. (2013). An Uncertain Future: Youth Frustration and the Arab Spring. Boston, MA: Boston University Press. Available online at: https://www.bu.edu/pardee/files/2013/04/Pardee-Paper-16.pdf (accessed June 30, 2022).

Nillesen, E., Grimm, M., Goedhuys, M., Reitmann, A. K., and Meysonnat, A. (2021). On the malleability of gender attitudes: evidence from implicit and explicit measures in Tunisia. World Dev. 138, 105263. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105263

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2011). Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Raz, D. (2019). Youth in the Middle East and North Africa. Princeton, NJ: Arab Barometer. Available online at: https://www.arabbarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/ABV_Youth_Report_Public-Opinion_Middle-East-North-Africa_2019-1.pdf (accessed June 23, 2022).

Rhodebeck, L. A. (1996). The structure of men's and women's feminist orientations: feminist identity and feminist opinion. Gender Soc. 10, 386–403. doi: 10.1177/089124396010004003

Robbins, M., and Thomas, K. (2018). Women in the Middle East and North Africa: A Divide between Rights and Roles. Princeton, NJ: Arab Barometer. Available online at: https://www.arabbarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/AB_WomenFinal-version05122018.pdf (accessed June 23, 2022).

Sadiqi, F. (2020). “The center: a theoretical framework for understanding women's rights in pre- and post-Arab spring North Africa,” in Double-Edged Politics on Women's Rights in the MENA Region, eds H. Darhour, and D. Dahlerup (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 49–70.

Salvatore, A. (2013). New media, the ‘Arab Spring', and the metamorphosis of the public sphere: beyond western assumptions. Constellations 20, 217–228. doi: 10.1111/cons.12033

Schnabel, L. (2016). Religion and gender equality worldwide: a country-level analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 129, 893–907. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-1147-7

Seguino, S. (2007). Plus Ça Change? Evidence on global trends in gender norms and stereotypes. Feminist Econ. 13, 1–28. doi: 10.1080/13545700601184880

Tausch, A., and Heshmati, A. (2016). Islamism and gender relations in the Muslim world as reflected in recent World Values Survey data. Soc. Econ. 38, 427–453. doi: 10.1556/204.2016.38.4.1

Thijs, P., Te Grotenhuis, M., Scheepers, P., and van den Brink, M. (2019). The rise in support for gender egalitarianism in the Netherlands, 1979-2006: The roles of educational expansion, secularization, and female labor force participation. Sex Roles 81, 594–609. doi: 10.1007/s11199-019-1015-z

Thomas, K. (2019). Women's Rights in the Middle East and North Africa. Princeton, NJ: Arab Barometer. Available online at: https://www.arabbarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/AB_Women_August2019_Public-Opinion_Arab-Barometer.pdf (accessed June 23, 2022).

Thorsen, E., and Sreedharan, C. (2019). # EndMaleGuardianship: women's rights, social media and the Arab public sphere. New Media Soc. 21, 1121–1140. doi: 10.1177/1461444818821376

Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., and Rasinski, K. A. (2000). The Psychology of Survey Response. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Weaver, I. S., Williams, H., Cioroianu, I., Jasney, L., Coan, T., and Banducci, S. (2019). Communities of online news exposure during the UK General Election 2015. Online Soc. Networks Media 10, 18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.osnem.2019.05.001

Welzel, C., Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2002). Gender equality and democracy. Compar. Sociol. 1, 321–345. doi: 10.1163/156913302100418628

Keywords: women's rights, Middle East and North Africa (MENA), political Islam, exposure, Arab Barometer

Citation: Thomas K and Kasselstrand I (2022) A long way to liberalization, or is it? Public perceptions of women empowerment in the Middle East and North Africa. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:984310. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.984310

Received: 01 July 2022; Accepted: 20 September 2022;

Published: 13 October 2022.

Edited by:

Susan Banducci, University of Exeter, United KingdomReviewed by:

Helga Kristin Hallgrimsdottir, University of Victoria, CanadaCopyright © 2022 Thomas and Kasselstrand. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kathrin Thomas, a2F0aHJpbi50aG9tYXNAYWJkbi5hYy51aw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.