94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 11 January 2023

Sec. Peace and Democracy

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.981867

This article is part of the Research TopicIsrael/Palestine: The One-State Reality Implications and DynamicsView all 8 articles

The paper analyzes the regime in Israel/Palestine using a political geographical perspective. It demonstrates how a combination of colonial, national, capitalist and liberal forces have put in train a process of “deepening apartheid” in the entire territory controlled by Israel—between River and Sea. This undeclared regime has been established to guard the 'achievements' of settler colonial Judaization of the land and the domination of the Jewish minority. As described by the Rome Statute, it has become an institutionalized regime of systematic oppression and domination by one group over others, with the intention of maintaining that regime. Hence the political geographical analysis shows clearly that the wide description in academic and international circles of Israel as “Jewish and democratic,” is based on a denial of the clear racialized hierarchy of civil statuses. This setting enhances Jewish supremacy (using different methods) it in all regions, while Palestinians are fragmented into lower rungs on the ethnic hierarchy—de facto and de jure—thereby contradicting the tenets of democratic civil equality. Theoretically, the paper draws on the links between settler colonial expansion, the rise of ethnocracy, partial liberalization under global capitalism, and the making of apartheid. It shows that historically Jewish colonization of Palestine—the underlying logic of the regime—has advanced in six main historical-geographical stages, encountering persistent, and at times violent, Palestinian resistance. The paper then analyzes in more detail the emergence of one regime between River and Sea, in which the state uses military, spatial, economic, and legal powers, as well as geopolitical maneuvering (particularly US support) to oppress Palestinians, while promoting democratic rights and economic development among Jews. This has enabled Israel to integrate and “whiten” Mizrahi and other Jewish groups into mainstream Zionism. Rivaling Palestinian political projects have been fragmented, ghettoized, attacked violently, and severely weakened. The paper shows how Jewish colonization, on both sides of the Green Line (which has also included some tactical withdrawals), has led to the establishment of four hierarchical types of citizenship, governed as “separate and unequal”. The relations between the groups resemble the racialized categories used in Apartheid South Africa and include (a) “White”—Jewish Israelis—with full citizenship rights; (b) “Colored”—Palestinian Arabs with Israeli citizenship with partial rights; (c) “Black”—Palestinians under occupation lacking citizenship or political rights; (d) “Gray”—an emerging group, consisting of non-citizen migrants and asylum seekers.

We must internalize the simple truth: Israel has a democratic constitution.... a Jewish and democratic state that also includes non-Jewish minorities. Our existence as a state in which non-Jewish minorities are entitled to full equality represents both our situation and aspiration… it will guide our national development as an enlightened society in the future. Barak (1998)

The above declaration, made by the former President of the Israel Supreme Court, represents the prevailing discourse among Jews in Israel and most international circles in framing the regime in Israel as “Jewish and democratic,” Such statements are routinely made literally daily by most leaders and observers in Israel and the West. The political assumption remains that the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip are “outside” of the Israeli political system while the Palestinian Arabs in Israel are full citizens of a “Jewish and democratic” state.

The current article challenges the credibility of this democratic definition which is based on persistent denial of the history, geography, demography, and political system created under Jewish colonization of the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. The repeated declarations of “Israeli democracy,” including wide circles in Israeli academia, are part of an intense effort to maintain an illusion of democracy despite ruling over millions of Palestinians who are either “temporarily” under military occupation, or possess a second-class citizenship (see Lustick, 2020).

A more credible analysis of the prevailing legal and spatial reality in recent decades points to a process of deepening apartheid that supports the maintenance of Jewish colonization. It is characterized by the regime's structural foundations that comply closely with the wording of Article 7 of the Rome Statute (1998; 2002) defining apartheid as an:

“Institutionalized regime of systematic oppression and domination by one racial group over any other racial group with the intention of maintaining that regime.”

The illusion of a Jewish and democratic state is significant because it represents the lived experience of most Jews in Israel, who enjoy substantial political rights and a plethora of democratic institutions on various levels of governance. These include freedom of mobility in most regions, freedom of expression, relatively unrestricted media, and reasonable, if partial (for women and religious minorities) protection of their human, civil and political rights. The functioning of selective democracy is critical for the sense of justification and legitimacy enjoyed by the Israeli state, internally and globally. Nonetheless, this democratic illusion conceals the oppressive nature of the regime toward all other ethnic groups.

Deepening apartheid is the result of historical spatial-political and legal processes that are rarely mentioned in Jewish discourse as being part of the Israeli regime. These include the displacement of most Palestinians during the 1948 war; the steady persistent expansion of Jewish settlement since 1948 within Israel Proper and mainly on Palestinian lands; the denial of the right of return for Palestinian refugees, and the gradual absorption of colonized (occupied) Palestinian territories into “Israeli proper” to form a single regime. Scholars have identified “a one-state reality” (Lustick, 2020; Lynch et al., 2020), despite the varied legal definitions and political arrangements that apply to different regions within the territory controlled—directly or indirectly—by Israel. During this process, the Green Line has all but disappeared for Jews who move freely throughout most of the territory, but has ‘hardened' for the Palestinians who have been placed under increasing surveillance, with their movement and rights severely limited (Sa'adi, 2016; Tawil-Souri, 2016; Erakat, 2019; Erakat and Reynolds, 2022).

Thus, the meta-logic of the regime is ethnocratic and colonial, namely Judaizing the power apparatus and land in which two nations of equal size reside, in order to entrench Jewish supremacy over the entire land, barring small and tightly bordered Palestinian enclaves. Hence, Israel should not be characterized as only a Jewish, but rather as a Judaizing state with severe consequences for its relations with the Palestinians.

“Political regime” is defined here as the combination of laws, institutions and long-term governmental policies and practices that promote the goals set by the centers of political power in a given territory. In Israel/Palestine, the regime is controlled by Jewish elites that represent approximately half of the population under its control. It has at its disposal the mechanisms of state, as well as powerful para-state institutions such as the Land Authority, Jewish National Fund, the Jewish Agency and the Settlement Division of the International Jewish Federation.

Most Jewish elites benefit from violent (“security-oriented”) control of the land, from a strong economy established through a process of market liberalization and integration into the global economy, despite persisting ethno-class inequalities among Israeli groups. The growing Israeli economy has managed to gradually integrate (unevenly) peripheral groups of Jews, most notably the Mizrahim (Middle Eastern Jews) and “Russian” (post-Soviet migrants) and even sections among Palestinian citizens who have enjoyed a measure of upward class mobility and the creation of a growing middle class. Nonetheless, these elites are simultaneously creating a discriminatory regime that oppresses most Palestinians, who are forcibly separated on geographic and ethnic bases, by imposing a regime rationale clearly divergent from the principles of democracy and international law, or from basic ethics of just and equal governance, as detailed below.

The central claim of this paper is that the combination of over a century persisting and violent colonization, strong nationalism and capitalist process of liberalization, have led together to the formation of de facto and de jure consolidation of an apartheid regime. This regime is marked by four main types of 'separate and unequal' civil statuses reminiscent of the apartheid regime in South Africa. (a) “Whites”—Israeli Jews with full citizenship rights; (b) “Coloreds”—Palestinian Arabs with Israeli citizenship and partial rights; (c) “Blacks”—Palestinians in the colonized/occupied territories who lack citizenship or political rights, as well as Palestinian refugees denied of the right of return; and (d) “Grays”—primarily non-citizen labor migrants, temporary residents, and asylum seekers. The regime has been established to guard the “achievements” of settler colonial Judaization of the land and the domination of the Jewish nation.

Significantly, the Zionist settler project has met, and continues to meet, persistent resistance from Palestinians, including political, legal, and at times terrorist acts. Unlike other European settler contexts, the conflict between the two ethno-national groups is yet to be determined. Therefore, the Palestinians, despite their current weakness and internal divisions, should not be treated as passive recipients of Israeli policies. They are key actors within an asymmetrical power dialectic that is yet to be finalized.

In this vein, somewhat paradoxically, the ongoing efforts by the Palestinian Authority and Hamas to promote Palestinian sovereignty contribute to some aspects to deepening the apartheid (Zreik and Dakwar, 2020). However, they and their power remain confined to small enclaves including significant control over only 6% of the land (Gaza and Area A), with their power effectively limited to places where Israel is uninterested to exert direct control (Ghanem, 2019).

The process of creating civil statuses is based on an assemblage of different “packages of rights” allocated according to ethnic origins and geographical location. The hierarchy has now expanded, in various ways, to both sides of the Green Line, becoming institutionalized and legalized, thereby reinforcing a political regime that advances its goals despite creating multiple ethno-national and ethno-class conflicts.

A key aspect that reflects and daily recreates the hierarchical civil status is the degree of group mobility. As shown comprehensively by Barda (2018), Bishara (2022), and Peteet (2017), Jews face no obstacles to full mobility across the entire Israel/Palestine, as well as the right for residence and housing on both sides of the Green Line (barring Gaza). Palestinians on the other hand enjoy very localized sets of rights which greatly vary from region to region. In general, Palestinian citizens of Israel have almost totally freedom of movement across the land, similarly to Jews, but they are severely restricted from settling or purchasing land outside their enclaves and some large cities. Palestinians in the territories are controlled by a strict permit regime that bars the majority of them from traveling into Israel proper, let alone reside or purchase land.

The common use of ethno-national (Palestinian, Jewish) and ethno-class categories (e.g., Mizrahi Jewish, Druze or Bedouin Arab, etc.) in the Israel/Palestine context, highlights some important differences between the South African and Israeli cases. While a systematic comparison is beyond the limits of this paper (see Clarno, 2017; Greenstein, 2020; Zreik and Dakwar, 2020), it should be noted that ethno-nationalism in Israel/Palestine largely plays the role “race” played in apartheid South-Africa. Thus, ethnonational affiliations most often denote ascribed impregnable identities carried by group members from birth to death. Ethno-class boundaries, created through Jewish immigration/colonization and socioeconomic stratification, are ever-present, but somewhat more porous within both Jewish and Palestinian collectivities (for elaboration see Sultany, 2014; Sadiq, 2017; Yiftachel, 2021).

Notably, the “color” categories I use to describe the hierarchy of group identities in Israel/Palestine do not imply an identical historical process of racial stratification as occurred South Africa, but are flagged to highlight the existence of a rigid hierarchy of collective affiliations—constructed as a given societal order—resembling pre-1994 South Africa. Notably, Jews and Palestinians are not distinguished by skin color, but the metaphor connects the processes in Israel/Palestine that are commonly treated as “sui generic” but most Israeli social scientists (Smooha, 1997), to similar processes in other colonial settler societies (Stasiulis and Yuval-Davis, 1995). The color metaphor also highlights the historical process in which Israel was established mainly by European Jews (“whites”), that used their superior “Western” image to marginalize peripheral Jewish groups, such as Mizrahim and “Russians.” Over time, however, these groups have also been politically “whitened” through gradual political and economic integration, while non-Jewish identities have continued to be constructed as “others” marking them as different and inferior.

The remainder of article aims to provide a broad geographic-political perspective. Therefore, it does not offer fine empirical details, which may be found in a range of previous publications (Yiftachel and Ghanem, 2004; Yiftachel, 2017, 2021). Moreover, defining the Israeli regime as apartheid is not intended to challenge the recognized right of Israel to exist as a sovereign state. Rather, it is intended to inform a process of decolonization and democratization, in both academic and public discourse.

The article proceeds with several definitions, continues with a brief account of critical literature to analyze the geographical and political development of colonization in Israel/Palestine through six principal historical stages, and examines the civil statuses that have become institutionalized during the process deepening apartheid.

Before delving into these issues, let us define several key concepts1:

• Democracy—A regime “by and for the people” based on the existence of a “demos,” a body of citizens with equal rights that includes all permanent residents of a given territory, for whom (and for no one else) the laws of the state are enacted by elected officials. The government is elected in periodic, general, free elections, and is committed to protecting equality, minority and human rights. The regime grants freedom of organization and expression, while protecting minorities from the tyranny of the majority.

• Ethnocracy—A regime in which a dominant ethno-national group appropriates the state apparatus in order to enshrine its ethnic control over resources and power systems in a multi-ethnic, conflicted space. An ethnocracy most often maintains a “layer” of formal democratic features such as citizenship for all, periodic elections, relatively free media, and basic human rights that coexist with a deep structure of ethnic control in most arenas of power, resources, and culture.

• Colonialism—A process of expansion in which a state or group violently invades a territory beyond its recognized borders in order to subjugate and exploit the indigenous population and its resources, thereby denying its right of self-determination. The indigenous population in the colonized territory is denied full citizenship and political rights. Colonialism is prohibited by international law. Internal colonialism is a similar process, often less violent, whereby the dominant group expands into spaces and resources associated with minority groups within the sovereign territory in order to appropriate resources and control the population.

• Apartheid—a regime promoting systematic oppression and domination by one identity over other groups with the intention of maintaining that domination. Apartheid regimes deny the oppressed groups full political legal and spatial rights. “Apartheid” as a crime is defined by two key international documents: the UN Apartheid Convention (1973) and the Rome Statute (1998; 2002) Since the ratification of the Rome Statute by most countries around the world, “apartheid” has become a generic term for regimes practicing racist collective discrimination that does not necessarily replicate the “original” South African model.

After decades in which most international scholars related to Israel unproblematically as a democracy, a significant change has occurred in recent years. Considering the reality of occupation, colonization, settlement, and persistent oppression of Palestinians on both sides of the Green Line, some scholars have begun to relate to Israel as an ethnocracy and colonial, apartheid regime. This trend began among Palestinian researchers during the latter part of the twentieth century and recently expanded into additional academic circles (for early works see: Sayegh, 1965; Rodinson, 1973; Zureik, 1979).

The public debate has changed as well, with a series of ground-breaking reports by key human rights organizations during the 2020–21 period, including Yesh Din (2020), Al-Haq (2021), B'tselem, Badil, Human Rights Watch (2021), and Amnesty International (2022). All are united in their conclusion that Israel has crossed the threshold necessary to define it as an “apartheid state” in some or all of the territories it controls. This is clearly a paradigm shift (Ben-Natan, 2022). That said, the academic, political and social discourse in Israel and among most social scientists internationally, maintains the view that Israel is a Jewish and democratic state (for comprehensive reviews, see Busbridge, 2018; Yacobi and Tzfadia, 2019; Ariely, 2021; Fakhoury, 2021; Sabbagh-Khoury, 2021).

Since the 1990's, a small group of critical Israeli scholars has begun to challenge the “self-evident” assumption of democracy; they include As‘ad Ghanem, Rouhana, Kimmerling, Jamal, Tzfadia, Yacobi, Kedar, Honaida Ghanim, and the current author. More recently, Sabbagh-Khoury (2021), Fakhoury, Nasasra, and Abu Rabia have joined the effort. These scholars categorize the regime in Israel as a settlement “ethnocracy” that is developing on colonialist roots; some have even warned early of a process of creeping apartheid (e.g., Yiftachel, 2000, 2005; Anderson, 2016; Ghanim, 2018; Kedar et al., 2018; Zreik and Dakwar, 2020).

Most of these scholars have adopted a settler-colonial perspective, which has been all but denied by the mainstream Israeli academic discourse. Yet, the theoretical connection is well-established between colonial expansion, as evident in Israel for seven decades, and a clear hierarchy of racialized civil statuses, buttressed by the racialized control of economic capitalist development (see Sartre, 1963; Fanon, 1965; Zureik, 1979; Said, 1993; Stasiulis and Yuval-Davis, 1995; Wolfe, 2006; Clarno, 2017). Influential works by Mamdani (2020), Veracini (2015), and Wolfe (2006), for example, show that settler colonialism establishes long term political systems of ethnic/racial domination, and that a primary rationale of settler societies is to replace the natives with new settlers. Unable to accomplish this end, such regimes often strive to minimize the civil, economic and spatial power and presence of indigenous populations (Wolfe, 2006; Veracini, 2015; Clarno, 2017; Khalidi, 2018; Mamdani, 2020).

I have previously defined the Israeli regime as “ethnocratic”—a general model of government whereby thin and partial features of formal democracy, such as elections and free media are undergirded by strong frameworks of ethnic domination, My analysis noted that ethnocracy in Israel/Palestine is undergoing a process of “creeping apartheid” (Yiftachel, 2000, 2017). Given the transformation during the last two decades, as detailed below, the regime has come far closer to a fully blown apartheid.

This occurred as a result of the ongoing colonization of Palestinians in different ways on both sides of the Green Line. In this process, Jews—spanning all ethno-class divisions and inequalities—benefit from relatively full and equal formal rights in all areas under Israeli control, while the Palestinians are divided into subgroups, each “enjoying” a different partial package of de jure rights, and political and spatial capabilities which are inferior to those enjoyed by Jews. This process has a clear spatial expression; the Palestinians are increasingly pushed into enclaves similar to the ghettos of the “Black” and “Colored” people that characterize racist regimes (see Bimkom, 2008; B'Tselem, 2021), while Jews continue to enjoy almost complete freedom of movement and residence both in Israel proper and Jewish areas in the colonized territories.

As Jamal (2016) skillfully depicted, the Israeli citizenship of Palestinian Arabs is significant, because it facilitates opportunities for upward mobility that separate them from the Palestinians in the territories. Yet, their political citizenship is still “hollow” with negligible impact on the nature of the Israeli regime and its policy toward occupation and colonization (Jamal, 2016, 2020).

Concurrently, the rapid economic neo-liberalization and globalization experienced in Israel in recent decades should be factored into the making of its political geography. Shafir and Peled (2002) clearly show how these processes have produced partial political liberalization (primarily among Jews), while simultaneously maintaining ethno-class inequalities. These structural forces expand the gaps between the material effects of the various “citizenship packages” offered to the various ethnic groups and feed the process of deepening apartheid (see Yacobi et al., 2022).

My central argument, let me recap, is that the Israeli regime has been constructed, as a main foundation, around the project of immigration and colonial settlement. In this context, a major blind spot in general regime theory is the widespread disregard of regime-building spatial processes. Most literature—in general and on Israel/Palestine, focuses on the characteristics of regimes at particular points in time (see Ariely, 2021). This literature tends to overlook the spatial and material changes that occur “under the shadow” of formal institutions and laws, including a foundational “colonial momentum” by which a dominant group expand into disputed regions, while evicting, marginalizing, and oppressing their indigenous inhabitants.

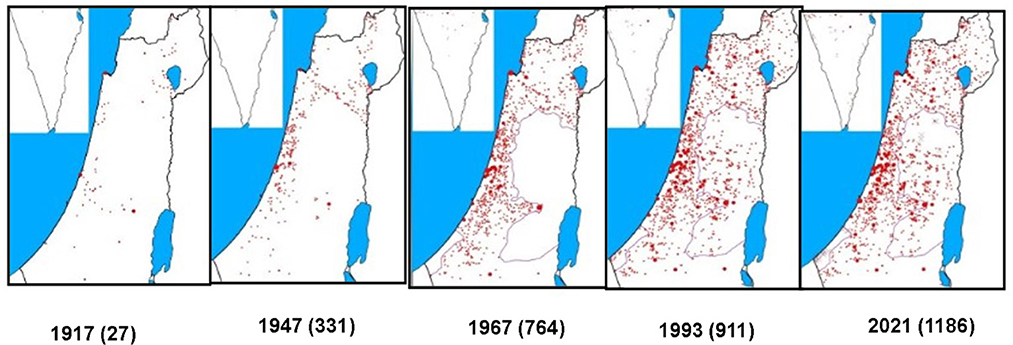

Figure 1 shows that the historical colonial momentum through which nearly 1,200 Jewish settlements have been established, is continuous and structural on both sides of the Green Line. This process of expansion cannot eventuate without violent, spatial, legal and institutional infrastructure that now form the foundation for the deepening apartheid regime. The “dark side” of this process is a massive shrinking of Palestinian space, the destruction of over 400 Arab localities by Israel and the tight policy of ghettoization that has ensued for the last seven decades (see Yiftachel, 2017). Historically, this colonization process has progressed in several key historical stages, as follows.

Figure 1. Jewish settlement in Palestine/Israel 1917–2021 showing number and location of settlements.

The first stage, from the late nineteenth century until 1947 can be characterized as “colonialism of refugees.” During this period, most Jews coming to the Land (which Jewish culture always regarded as a historical homeland) could be considered refugees or forced migrants because their emigration was motivated by political and economic oppression in their prior countries of residence, during and after the Holocaust (Yiftachel, 2021). Even the relatively small, ideological core that came willingly was motivated, as seen in the writings of most Zionist leaders, by anti-Semitism in Europe and later by Arab nationalism that marginalized and displaced Jews. Upon arrival, these “forced migrants” naturally became part of Zionism and expanded their settlements in Palestine, by purchasing land and establishing settlements, causing some displacement of Palestinian Arabs, mainly peasants. Simultaneously, particularly after the arrival of hundreds of thousands of refugees from Germany and Eastern Europe during the 1930's, who strengthened Zionist national institutions and armed forces, thereby laying the foundation for the future nation-state.

The second stage occurred during the 1947–1949 war. At first, this stage was characterized by conflicts between Jewish and Palestinian communities, following Palestinians rejection of UN Resolution 181 (“two states with economic union”). The war developed into conflict between the State of Israel and Arab States following its declaration of independence. During this war, Israel, Jordan, and Egypt each conquered portions of the would-be Arab-Palestinian state. More than 700,000 Palestinians were forced out of the territory captured by Israel; hundreds of villages were completely demolished, and the return of Palestinian residents was blocked. This was the most significant stage in the shaping of the Israeli regime, which ever-since has worked to protect the territorial and demographic “achievements” gained during the war. In 1949, Israel became a member of the UN and gained firm international legitimacy within the 1949 borders. Simultaneously, the Palestinians became a defeated and dispersed nation. They lost most of their settlements and lands within Israel proper and were displaced as refugees into surrounding states and new diasporas, while their homeland was being Judaized.

The third stage, from 1949 to 1967, was characterized by internal colonization. The State prevented the return of the Palestinian refugees and nationalized their lands. Simultaneously, Israel absorbed massive Jewish immigration, primarily refugees and forced migrants from Europe and Islamic countries. Following these waves of immigration, hundreds of new Jewish settlements were established on former Palestinian lands and beyond. The Jewish settlements were intended not only to Judaize the Arab Palestine but also to shape the structure of Jewish Israeli society, using national, centralized, modern planning, dictated by Eurocentric perceptions and ideologies. During this stage, Israel established an ethnocratic regime—some formal democratic institutions and universal elections, while expanding Jewish control and placing Palestinian citizens in ghetto-like enclaves under military rule until 1966.

The fourth stage, from 1967 to 1993, began with Israel's conquest of the West Bank, Sinai, Gaza Strip, and Golan Heights. The conquest was accompanied by limited destruction of Palestinian localities and unlike 1948, most Palestinians remained in their place. At the same time, the Jewish colonial project continued to expand with the establishment of some 120 colonial settlements, housing ~100,000 Jews, in clear contravention of the international law. The process included Palestinian East Jerusalem (Al-Quds) which was partially annexed to Israel (without either formally changing the international border or granting citizenship to its residents). During this period, an important precedent of evacuating Jewish settlements was also established as part of the peace agreement with Egypt in 1978. Meanwhile, religious narratives began to occupy a growing place in the spatial imagination of both peoples and were recruited to justify the escalating conflict. The Judaization process continued primarily by establishing Jewish settlements and suburban communities on both sides of the Green Line. This was accomplished using a rigid regime of restricting the growth of Palestinian localities and nationalizing Palestinian lands by manipulative use of the legal system. Palestinian resistance climaxed with the First Intifada (1987–1993) which was a popular, mostly non-violent, uprising which momentarily changed the course of history.

The fifth stage began in 1993 and continued until the beginning of the third Netanyahu government in 2015. It was characterized by slowing down, even reversing Zionist expansion. For more than 20 years, it seemed that there had been a deep change in Jewish discourse, with a sequence of Israeli prime ministers—Rabin, Barak, Olmert, and even Netanyahu, supporting the idea of establishing a Palestinian state. The Oslo Accords Israel recognized the Palestinian national movement, despite the outbreak of the very violent second intifada during which waves of unprecedent terror hit Israeli cities. It later became clear that although some steps appeared at the time to be historical, the rhetoric around a Palestinian rights was not supported by significant steps toward decolonization. These included allowing a Palestinian Authority to be established in Ramallah; withdrawals from Palestinian cities and “Area A” (under the only partially fulfilled 1993 Oslo accord), complete withdrawal from occupied southern Lebanon (year 2000); and military and settlement exit from Gaza (the 2005 “Disengagement”). Yet, with the perspective of time, it appears that these small but significant territorial retreats occurred without significant change in the Israeli goal of maintaining ultimate Jewish control of all territory between Jordan and Sea (for mapping details - Arieli, 2021).

As Jewish expansion slows down, and at times even retreats during this stage, the land's political geography is characterized by a transition from “horizontal” expansion (military, settlement, and land seizure) to “vertical” ethnic control (legal, institutional, and political). This point is critical for understanding the gradual imposition of apartheid mechanisms, intended to “restrict” hostile populations by imposing substantive uneven separation between Jews and Palestinians. The most conspicuous act was the construction of the separation fence/wall/barrier in the colonized West Bank during the early twenty-first century in partial response to Palestinian terror attacks. The barrier severely impairs Palestinians' right to movement, development and fabric of life. Indeed, The ICJ in The Hague deemed its construction at its specific location illegal. Another move was the ongoing siege of the Gaza Strip and the conduct of several extensive military “operations” in response to Hamas' ongoing attacks on civilians in southern Israel. This polarizing process led to the strengthening of the nationalistic and religious rightwing in the Israeli elections of 2013 and 2015, and the establishment of Hamas as the undisputed ruler in Gaza, as well as the rise of the United Arab List in the Israeli elections of 2015.

The sixth stage begins with the rise of the fourth Netanyahu government in 2015. Its roots lie in the backlash against previous conciliation and withdrawal moves during Barak's, Sharon's and Olmert's reigns as Prime Ministers. A rise of nationalist politics intensified the pace of de-facto “creeping apartheid” and accelerated its transformation into a de jure “deepening apartheid.” This was characterized by legislation, institutions and overt practices designed to anchor Jewish superiority and advance annexation. The most conspicuous move was passage of the Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People (2018) which attempts to enshrine Jewish superiority in the entire Land of Israel and establishes continuing Jewish settlement as a national value. This law ignores the existence and identity of Palestinians who constitute about half of the population in the areas under Israeli control; and demotes the status of Arabic from its previous status as an official language. Also enacted during this period were the “Judea and Samaria Settlement Regulation Law” (later struck out by the High Court); the Acceptance Communities Law (which allows hundreds of Jewish gated communities to screen their in-coming residents); and the “boycott law,” deterring Israelis from advocating boycott against Israeli institutions anywhere. Settler-colonial institutions also initiated additional moves such as establishing dozens of Jewish pastoral farms occupying large areas of the West Bank, constructing several dozen new residential “outposts” in the West Bank, continuing efforts to settle Jews and displace Bedouins in the Negev/Naqab, and establishing and funding urban settler groups (“Gar'inim”) in order to Judaize both ethnically and religiously, in Israeli cities (Shmaryahu-Yeshurun, 2022; Yacobi et al., 2022).

Another key step taken during this stage was the effort to annex parts of the West Bank, which the Likud party adopted as central to their platform for four elections held during 2019–2021. Although yet to be implemented de-jure, annexation has become a goal shared by most rightwing and religious Jewish parties in Israel, together with adopting governance practices which increasingly include direct legislation and regulation of Jewish residents of the West Bank. A representative expression of the sixth stage was the broad support of the Jewish center and rightwing parties for the “Deal of the Century” plan promoted by US President Donald Trump. The Deal included annexing approximately one-third of the West Bank, creation of several dozen Palestinian enclaves as the divided infrastructure for a shrunken, non-contiguous Palestinian state, and even a dramatic provision for transferring regions populated by Israeli Arab citizens to the future Palestinian state. The plan also allocated some remote and disconnected desert regions as partial “compensation” for the Palestinians. In response to these polarizing steps, a round of violent confrontations erupted in May 2021, the first in decades to occur within the Green Line, concentrating in binational (“mixed”) cities. Similarly, in spring 2022, there were direct confrontations on several university campuses in Israel when students raised the Palestinian flag at events marking the Nakba and encountered mass rejection by Jewish groups.

Yet, the same period (2021) saw the establishment of the first Israeli (Bennet-Lapid) government with the United Arab List as a minor non-ministerial coalition partner. Although this significant step can be seen as countering apartheid, it should be noted that the coalition agreements avoided all matters related to the Palestinian issue, making it possible to continue the colonization of Palestinians while increasing material resources to Israel's Palestinian citizens. Within our proposed framework, establishment of this coalition could be understood as the partial participation by “the Coloreds” in “White” colonial power, thereby legitimizing it but also increasing the divisions between “Blacks” and “Coloreds” amongst the Palestinian people. As such, the new ruling coalition, under which occupation and colonization continues, provides an important, if unintended, oil in the cog wheels of a deepening apartheid regime. It is symbolic that the Bennet-Lapid government collapsed in June 2022, after one year in office, due to its inability to pass the so-called “the apartheid regulations”—extending emergency regulations that allow West Bank Jewish settlers to be subject to Israeli law and administration.

Why has the discourse that classifies Israel as apartheid become prevalent during the last few years, including not only Palestinian and Israeli NGOs, but also reputable organizations such as Human Rights Watch (2021), Amnesty International (2022), and the UN's Special Rapporteur to the Palestinian Territories, Michael Lynk? (for review, see Ben-Natan, 2022)?

The timing is not accidental. The change is related to the nationalist-colonialist reaction to attempts at reconciliation with the Palestinians; and to the slowdown in settlement and Judaization momentum since the 2005 “disengagement.” The powerful governmental, public, diaspora, and capitalist institutions vested in the Judaization project continue to produce such agendas. In addition, the fact that Jews are likely to become a demographic minority in the area under Israeli control, while attempting to maintain political supremacy and Palestinian marginalization, “necessitate” the regulation and practice of apartheid. The new laws and regulations have the effect of normalizing Jewish supremacy in the eyes of most Israelis, while strengthening nationalist elements in Israeli politics. Notably, Palestinian and (meek) international opposition to such moves has been muted by the US support of Israel in most international bodies, including the UN, thereby shielding all attempts to punish its continuing blatant contravention of international law and norms.

As time passes, an increasing number of these practices will be considered “essential” for thwarting Palestinian struggle for rights, which is painted as an existential threat to Israel. Acts of resistance to Jewish supremacy are labeled “treason,” “invasion,” and “subversion” or “support for terrorism” thereby placing such acts beyond the boundaries of legitimate politics. The steps taken during the sixth stage are clear testimony to a geographical-political stage of regime transformation where deepening “vertical” legal and political frameworks of Jewish supremacy between the River and the Sea are becoming the norm.

In light of the above, it is important to note that scholars of the Israeli/Palestinian sphere do indeed have difficulty formulating an accurate, uniform definition of the “Israeli regime.” The difficulty stems from several factors, most importantly the mismatch between the territory controlled by the regime and the country's internationally recognized borders. “Apartheid” in Israel/Palestine is therefore a process, more than a formally defined system of government. Under current conditions, the occupation and colonization of the territories (and associated persistent discrimination of the Palestinians) is considered by Israel, and, to some extent, international law, to be “temporary” and moreover, justified by the security rationale of the occupying state. This “temporary” status is used by the Israeli “hasbara” (public relations) and by most Israeli scholars to deny the charge of apartheid and justify the putative democratic nature prevailing in “Israel Proper” (Radday, 2022).

But clearly, the “temporariness” of the occupation, which has no foreseeable end, and Israel's self-defined “security needs,” are intended to circumvent and distort international law that prohibits forcible takeover and appropriation of territories outside the state border. Although the claim of temporariness remains a public relations tool used by Israel, its political and legal credibility has been seriously weakening. Recently the UN Human rights Council concluded the following with respect to ending the occupation:

“It is this lack of implementation coupled with a sense of impunity, clear evidence that Israel has no intention of ending the occupation, and the persistent discrimination against Palestinians”

The picture is further complicated by the Jewish-religious discourse, which provides the ideological basis for much of the settlement project and considers the takeover (or “liberation”) of the West Bank as a permanent, civilian project. This contradicts Israeli official line that presents the settlements as part of a temporary belligerent occupation of ‘contested territory', or answer to security needs.

Moreover, settlers residing in the West Bank are key players in Israeli politics, and have been instrumental in all rightwing governments over the last four decades. Simple electoral analysis shows that if election results were counted democratically only within Israel's recognized borders, the Center-Left coalitions would have won 12 or the last 15 election campaigns, instead of two (!) in reality. Due to the settlers vote and their permanent membership in all Israeli governments since the 1980's, as well as a general shift to the nationalist Right, particularly by the ruling Likud and Ultra-Orthodox parties, the state has been dominated by rightwing nationalism and apartheid supportive agendas. Hence, it is a blatant distortion to separate the political regimes on the two sides of the Green Line, simply because Jewish political space truly stretches on both sides, and Jewish colonial settlers are key factors in determining the racist rule over their Palestinian neighbors. At the same time, Palestinians have no political right to determine the government, laws and policies that rule over their regions.

Hence, I argue, it is time to depart from the common use of the word “occupation,” which is no longer appropriate for credible account of the power structure governing the Palestinian territories. International law defines “military occupation” as a temporary military government, external to the state borders and polity, such was Israeli control of southern Lebanon or the American-British control of Iraq. In the eyes of most Jews, Israeli rule over the territories is precisely the opposite—permanent, civil and internal to the Israeli political system.

Therefore, it is time to call the child by its name: the occupation of the territories has become part of an overall apartheid regime, which facilitates on-going seizure of the land and control over its residents and resources. It is no longer possible to separate “here” from “there,” when there are some 700,000 Jews residing in the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and nearly two million Palestinian Arabs residing within Israel Proper. Geographically and politically, the settler population, whose municipal areas cover about half of the West Bank, is an integral part of the Israeli political and civil community.

There is still military control, of course, but it is limited to the Palestinian population, and serves as the violent infrastructure of an imposed multi-layered regime. Although the situation with Hamas rule in Gaza is more hostile, it is not principally different. Israel imposes a tight blockade which makes Hamas dependent on Israel. This creates a tense status-quo which does not disrupt, and even assists through total separation, the deepening of the regime elsewhere.

Therefore, large parts of the Palestinian territories have long been not only “occupied” but also “colonized,” i.e., settled by Jews and de-facto annexed to the Jewish state, including the vast amount of land registered as “state land” (in distortion of local and international law, see B'Tselem, 2012). Israel has an interest in continuing to present the situation as a “temporary” thereby maintaining the illusion of separation between “democracy within the Green Line and temporary occupation in the territories.” This process also facilitates the on-going denial of the Palestinian right of self-determination and civil rights. Nonetheless, it is plain to see that this distinction has long since disappeared. The scope of the settlement project is tremendous and the political involvement of the settler population in the Israeli government has grown considerably, including membership in all governments during the last two decades.

As regards the Palestinians, Israel continues to control almost all central aspects of sovereignty in the West Bank and even in the Gaza Strip, leaving the Palestinian Authority and Hamas mainly the power of internal policing, local economic policies and symbolic representation, The PA and Hamas are effectively maneuvered by Israel (through bordering and economic dependency) to subdue Palestinian discontent, and thus assist in stabilizing apartheid. To illustrate, Israel controls immigration, population registration, imports and exports, water supply, transportation infrastructure, internet infrastructure and data management, land use policy and planning (in area C), foreign relations and foreign investments, as well as complete military control over land, sea, air, cyberspace, and media (Tawil-Souri, 2016).

Given the permanent settlement, creeping annexation and Israeli exercise of sovereign power over Palestinians, it is no longer possible to distinguish two regimes on either side of the Green Line, as commonly done in Israeli politics and academia. Therefore, to truly understand the nature of the current regime, we should examine the varied levels of rights enjoyed by groups of Jews and Palestinians under this regime.

To be sure, the political separation of Israel and Palestine is not a total impossibility, but highly unlikely to be attempted, let alone succeed, thereby putting paid to the classical two state solution. This shattered illusion has been termed “the two state illusion” by scholars who have announced the “collapse of the paradigm” and beginning of a situation similar to what Antonio Gramsci called an “interregnum,” a dangerous situation in which the old order collapses without a new one being consolidated (see Lustick, 2019).

The side effect of Judaization is exacerbating relationships among groups internally within Israel, particularly between the Jewish majority and Palestinians Arabs, and “foreigners” such as asylum seekers and migrant workers. Antagonism toward civil society organizations and political groups that oppose the continuing colonization of the Palestinian people is also increasing.

However, some trends in the opposite direction are also taking place. For example, there has been partial, but important improvements in the living conditions of Palestinians in Israel, with development in certain policy areas, such as Government Resolution 922 that transferred new budgets to reduce the Arab-Jewish socioeconomic gaps and growing levels of education and expanding Arab middle class. Simultaneously, there has been significant growth in civil society activity on behalf of Jewish-Arab equality in Israel, which became significant during the May 2021 clashes (Fakhoury, 2021). Despite this, the damage inflicted on the Palestinian Arab minority through the Judaization process remains conspicuous and structural. For example, since the “October events” of 2000, strict regulations have been enacted on personal liberty of Palestinian Arab citizens, exposing them to increasing digital monitoring, limiting their employment possibilities and continuing discrimination in matters of land use and planning. This has been accompanied by racist political discourse, which has aired threats of denying Palestinian citizenship, transferring areas with large Palestinian populations to the Palestinian state (the one whose establishment Israel is preventing…), and most recently, threats of a “second Nakba” by senior Likud leaders such as Yisrael Katz and Uzi Dayan, following Nakba day events in 2022.

A series of recent laws—the Nakba Commemoration Law, the Law for Prevention of Damage to State of Israel through Boycott, the “screening committees” Law and Amendment 44 to the Basic Law: The Knesset that allows the Knesset to expel members—were enacted, primarily with the intention of continuing political control over Palestinian citizens of Israel.

Within the Green Line, the deepening Apartheid effect is especially felt among Negev/Naqab Bedouins who are fighting displacement policies and house demolitions. The state denies many Bedouin communities rights to lands and planning recognition, and hence basic services such as water, electricity, roads, public transportation and educational institutions. Continuing state violence is used against the Bedouins in the form of unprecedented waves of house demolitions reaching nearly 11,000 during the 2018–2020! To emphasize the severity of this blow, note this number is four times higher than demolitions in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem together during the same period. In some ways, the lack of basic security and difficult living conditions of the more than 120,000 Bedouins living in unrecognized villages is even worse than those Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, including the refugee camps. These conditions are a stinging reminder that the ongoing, deepening apartheid practices are apparent also toward Arab citizen inside Israel Proper (see Kedar et al., 2018).

From this perspective, the process of deepening apartheid becomes clear: in practice, Israel officially ranks Palestinian groups de-jure and grants each of them different status and hence a different “citizenship package. The Palestinians are divided into the following main groups, ranked according to their rights: Druze; Palestinians Arabs in the Galilee and Triangle region; the Bedouins in the Negev; Palestinians in Jerusalem; Palestinians in the West Bank other than Jerusalem; residents of Gaza; and refugees not under Israel's control whose claims for residency and reclamation of property are rejected out-of-hand.

Although all are subject to a consistent policy of Judaization, these groups differ in their legal status and exposure to oppression and violence. There is a significant gap in the realization of their rights, economic status, and way of life. Arab citizens of Israel, despite their relative marginality, enjoy certain fruits of citizenship, political representation, and Israeli economic power, which differentiate them from their brethren in the colonized territories. However, they are not equal to Jewish groups. These structural differences are essential for understanding the regime of “separate but unequal.”

To summarize, as already noted, we can conceptualize citizenship type in the entire Israeli-controlled area using the tropes of South African apartheid. Accordingly, it seems that over several decades Israel has created structural stratification, with four major types of civilian status in areas under its control:

1. “Whites” (Jews, anywhere on the entire land)

2. “Colored” (Palestinians with Israeli citizenship)

3. “Blacks” (Palestinians with no Israeli citizenship)

To whom, a minor yet growing group has recently been added:

4. “Grays” (labor migrants, temporary residents, and asylum seekers)

Within each of these major categories there are multiple subgroups, divided on an ethno-class basis, such as Mizrahim, immigrants from the former FSU, Ultra-Orthodox or National Orthodox Jew, or West Banker, Jerusalemite, Gazan, Druze or Bedouin among Palestinians. But the type of 'citizenship package' enjoyed by these groups, too, is strongly related to their position vis-a-vis the colonial momentum in Israel/Palestine. Beyond the details, and the many internal Jewish and Palestinian tensions, it is important to discern the overall structural picture in which these four types of citizenship have evolved over time as foundations of the Israeli apartheid regime.

The one-regime reality has also created an economic “shekel space” between River and Sea, where all groups use the Israeli currency, and where Israel controls all major economic parameters. Within that space the “separate and unequal” regime has been translated into clear socioeconomic gaps: the GDP per capita in 2021 in Israel was about $43,000, 13 times higher (!) than the West Bank Palestinian figure of $3,200, while Gaza's figure is estimated below $2,000. Within Israel, the average income of Arab citizens is about 55% of their Jewish counterparts (Adva Center for Social Equality, 2021). The trend in unemployment figures is similar: in 2019, the real unemployment rate in the occupied territories was 35–40%, while among Palestinian citizens of Israel, it was 12–13%, and only half that among Jews. Approximately 77% of Palestinians in the occupied territories live below the poverty line, compared to 58% of Palestinian citizens of Israel and 17% of the Jews. In other words, the combination of the Judaization project and the nature of Israeli controlled capitalism, has created three distinct ethno-classes which largely overlap the “black-colored-white” distinctions made above.

A central foundation of the deepening apartheid regime relies on spatial control in the form of settlement, land, development, municipal boundaries and control of movement and development. As of 2021, Palestinians accounted for about half the population between the River and the Sea (approximately the same as Jews), but controlled only 15% of the land. Jews (as individuals, organizations and state authorities) control the entire remaining area, including most of the infrastructure and natural resources. Within the Green Line the gaps are even greater: Palestinians are 19% of the population and control < 3% of the land.

Jewish land seizure has expanded rapidly. In 1947, at the end of the first stage of the Zionist enterprise, Jews controlled only around 5% of the land in historical Palestine and 7% in the territory to become the State of Israel. The remaining lands were owned and/or controlled by Palestinian Arabs or lacked ownership or use. State lands that the British mandatory government transferred to the State of Israel are estimated at only 1% of the territory (see Kedar and Yiftachel, 2006). At present, however, Jews (mostly through the Jewish state) own 97% of lands within the Green Line.

The process combined violent seizure, discriminatory legislation and institutionalized land grab as protection for Jewish settlements. The planning, housing and land institutions, for example, are characterized by only negligible representation of the Arab population. For example, of 78 members on the six district planning commissions in Israel, only five are Arabs. In the colonized West Bank, there is no representation of Palestinians in Israeli planning institutions. The situation is even more severe in other planning and land institutions, which are controlled entirely by Jews. The most important of them, the Israel Land Council, does not have a single Arab-Palestinian representative. Other semi-governmental Jewish organizations that promote spatial Judaization include the Jewish National Fund, the Jewish Agency, the Settlement Division, Amana and the Jewish regional councils in the West Bank and to a lesser, yet significant degree, Regional Councils within Israel that cover 84% of the state territory.

The gap between citizens of different ethnic origins is especially conspicuous in matters relating to building and house demolition. For example, in area C of the West Bank, only about 20% of the over 400 Palestinian villages had approved outline plans in 2020 covering only 1% of the area, while most Jewish settlements have approved plans, covering 9% of the area. Without such plans, it is impossible to receive a building permit, and hence most Palestinian construction is deemed “illegal.” Consequently, more than 2,000 Palestinian homes were demolished by Israel between 2010 and 2019, and demolition orders were issued against thousands more. Jewish residents of the region suffered only a few dozen demolitions and generally benefited from creeping approval of outposts built in violation of international and Israeli law (Al-Haq, 2020).

The situation is similar, although less severe, in most Palestinian towns in Israel proper where approximately one-half of the Palestinian towns and villages lack approved outline plans, causing underdevelopment and home demolitions. In 2000, there were 22,000 unauthorized structures in Arab towns and villages in central Israel, not including the Negev, compared to 16,000 in the Jewish sector. Yet, in Arab towns, more than 800 homes were demolished in 2003–2020 while in the Jewish sector (which is four times the size) there were only 150 demolitions. Furthermore, 62 private farms were established in the Negev for Jews without planning permits and were deemed illegal by the court. Yet, all of them were retroactively legitimatized by legislation. Meanwhile, more than 17,000 Bedouin homes were demolished, in the same area, during 2009–2020. These were homes built on indigenous lands inherited by their owners from their ancestors. These forms of spatial oppressions illustrate again the tiered level of citizenships under the apartheid regime.

The process of Judaizing land, on all levels, has turned Palestinian towns and villages into a mosaic of isolated enclaves and ghettos whose dimensions are frozen at the size they were in the late 1960's, while the population has grown 5-fold! Jews benefit not only from larger living space, but also from freedom to live to settle, colonize and travel. In the metaphorical language used here, Palestinians in the colonized territories reside in what can be described as “black ghettos,” strictly controlled from “above,” with their residents subject to severe restrictions on movement and development. These ghettos are spatially divided due to serving the “needs” of (illegal) Jewish state or settlers, particularly those defined as “security needs.”

The boundaries of the “colored” enclaves, where most Palestinian citizens of Israel reside, are “softer” than those in the West Bank and Gaza, but their residents are also systematically discriminated against. Approximately half their lands have been nationalized, and Arab residents are subject to a range of boundaries and restrictions, deriving from tight control over municipal boundaries., Lack of development, and restrictions on their freedom of residence (most notably born of the ability of Jewish non-urban localities to “screen” their incoming residents and market mechanisms in Israeli cities), discriminate against low-income groups. Palestinians in Israel find it very difficult to emigrate from their villages due to the complete absence of new Arab settlements (other than those established in order to urbanize the Bedouins) since the establishment of the State of Israel. In addition, there exist provisions preventing them from purchasing land or housing in most of the country, and the lack of educational, cultural, and religious institutions in areas outside their communities. Only in the few binational cities is there some level of integration, primarily through middle class Palestinian Arabs migrating to Jewish neighborhoods.

The ghettoization of Palestinian spaces is also highly marked on the macro legal level. A blatant example of this is the prohibition on family unification in Israel between Palestinians from the territories and Palestinians who are citizens of Israel (enacted 2003) which was renewed as part of the Citizenship Law in 2021. This means that two groups of Palestinians, who live under the same regime are prevented from establishing joint families and living together in Israel (for similar colonial situations, see Fanon, 1965).

While Palestinian groups are spatially and legally separated, Jews on both sides of the Green Line operate as a single “seamless” entity, for economic, social, cultural legal, and political purposes. The uniform legal and geographic status of Jewish space between River and Sea displaces Arab spaces which have become divided, weak and threatened. In terms of spatial management, as outlined above, the nearly contiguous Jewish spaces present multiple limitations on the rights and movements of Palestinians and other non-Jewish groups through a range of ethnically based and market-led mechanisms.

Supreme Court rulings in recent years reflect this deep change in the legal and political geography. For example, the 2013 ruling that permitted the removal of the Bedouin settlement Umm al-Hiran in the Negev to make room for the planned Jewish settlement Hiran on the very same land; or the 2018 ruling that similarly permitted the removal of the West Bank village Khan al-Ahmar to facilitate expansion of a Jewish settlement. In April 2022, the Supreme Court went even further with a consent for the removal of seven Palestinian villages, all are part of Musafer Yatta in southern Mount Hebron, to create a military training area. This action affirmed the putative superiority of Israeli law over international law (!) even in territories declared by Israel as existing under military occupation, as articulated by the Court.

Even if we assume that it is necessary to examine the actions of the military commander in the region according to provisions of the “treaty norm,” no one disputes that when Israeli law conflicts with the rules of international law, Israeli law prevails (emphasis O. Y.).2

This illustrates how the apartheid regime is thickening and deepening. Israel (and most international circles) continue to hold the bogus description of the military occupation as 'temporary', ignoring the permanent transformation of the area by Jews using racist discrimination. At the same time, “Israel proper” is declared a democracy, while infringing many tenets of such a regime.

Here is how apartheid is developing: on the one hand Israeli distorted claims about the temporary nature of the occupation and the existence of “democracy” within the Green Line (echoed by most intentionally blind international circles), while on the other, hand—systemic discrimination of Palestinians backed by permanent settlement, legislation and government practices.

Beyond the political and moral urgency of seriously addressing the deepening apartheid regime, there is also a pressing need for further scholarly analysis of the transformation of ethnocracy into apartheid. Rather than argue about the existence or otherwise of apartheid, which is plain to see, it should become a starting point for serious research that compares and analyzes the various types of apartheid regimes, which differ in detail but not in principle from the infamous South African case. As shown above, the apartheid in Israel/Palestine is based on ethnic and national discrimination. This may differ from oppression on the basis of “race” (i.e., skin color) that was practiced in South Africa. Is this a political and ethical distinction with genuine significance? Is Israel perhaps more similar to the Serbian model of apartheid in Kosovo during the 1990's or of that in Sri Lanka or Northern Ireland? Is there, for example, a distinct type of “ethnic apartheid?” or are ethnicity and race interchangeable as categories of hierarchical citizenship? Comparative studies would be most enlightening.

It is also important to scrutinize the dimension of political and legal time in the making of apartheid regimes. As we saw, the legitimation of the Israeli regime is based primarily on the notion of “permanent temporariness” which characterizes the political geography of the colonized territories, Bedouin localities, and (non)treatment of asylum seekers. How long can the “temporariness” of occupation regime be extended? What are the internationally comparable cases (e.g., Turkish rule of Northern Cyprus, Moroccan rule of Western Sahara or Russian of Ukraine). What impact does temporariness have on the population both on the ruler and the rulers? As scholars such as Jamal (2008), Kedar (2016), and Tzfadia and Yiftachel (2021) show, the politics of spatial time has other dimensions, such as the valorization or denial of ethnic history, spatial continuity, and the links between local histories and land rights. Another dimension of time is the impact of labor migration on political regimes, with the key examples of the Gulf States, such as the Emirates and Kuwait accommodating a majority of non-citizens as multi-generational “temporary” residents, thereby creating new versions of apartheid. Clearly, then, further exploration of the political geography of time in general, and “apartheid time” regime in particular, would add much to our understanding of the emergence and maintenance of apartheid regimes.

A further aspect worthy of consideration in future research is the intersection of identity and class, including connections between apartheid-style forced separation and the accelerated privatization and globalization of the Israeli/Palestinian economy. Further to the work of Shafir and Peled (2002). Farsakh (2015) and Yacobi and Tzfadia (2019), it would be appropriate to ask: What role do global (particularly western) capital and markets play in this process of stratified citizenship in Israel/Palestine? What are the implications of the massive importation of foreign labor migrants to replace Palestinian workers? How is deepening apartheid fed by the rapid accumulation of capital in the hands of national elites? How does ghettoization of the Palestinians influence the making of all ethno-classes in Israel/Palestine? And what has been the impact of the BDS movement and other quieter boycotts of Israel and other criminal states?

Most importantly, the issue of decolonizing an apartheid regime “on the ground” clearly requires a deep change in scholarly and political orientations. This begins with a change in the framing, discourse and awareness, and continues in political mobilization and regime transformation. In Israel/Palestine, such changes are not presently visible on the horizon, primarily because the “pro-apartheid camp” has grown stronger in Israeli politics, protected by the “shield” provided by powerful American geopolitics and the active Israel lobby in Washington, and to a lesser degree European diplomacy, which allow Israel to continue violating international law with impunity. Likewise, increasing divisions within Palestinian society, ongoing terrorism against Israeli civilian populations, and closer relations between Israel and some parts of the Arab world—all contribute to the ongoing deepening of apartheid.

Yet, the apartheid regime in Israel/Palestine still appears unstable, unworthy, illegal and immoral. Therefore, it is high time for Israeli and international scholars to analyze accurately the political regime ruling over the entire territory. Transforming the scholarly and media discourse to reflect the situation on the ground is essential for de-colonizing the Palestinians, consciously, politically and materially.

Finally, it should be highlighted that several civil initiatives “on the ground” to resist apartheid have been launched in recent years. Space does not allow elaboration on these movements beyond highlighting their rejection of the “international consensus” over a traditional, segregated and heavily bordered two state solution. These movements—that include “A Land for All,” “One Democratic State,” “Combatants for Peace,” and the “Federation Movement,” among others, explore new waves to decolonize relations between Jews and Palestinians on the basis of integration, equality, power-sharing, and freedom of movement (for reviews—Scheindlin, 2018; Halper, 2021; Yiftachel, 2021). The visions of these new anti-apartheid initiatives are all anchored in the understanding that both Jews and Palestinians see the entire land as their homeland, and that ways must be found to decolonize the regime, in order for the two peoples to exercise their right of self-determination while sharing the land in equality and dignity.

In 20th of June 2022, Naftali Bennett, the Israeli Prime Minister resigned after weeks of political instability. The final “straw” was the inability of the government to pass the Judea and Samaria (West bank) Regulations known among Palestinians as “the settlers law” or “the apartheid law.”3 These regulations enable Jewish West Bank settlers to remain under the jurisdiction of the Israeli judicial and administrative, as opposed to their Palestinian neighbors, who are subject to military rule. Bennet stated:

“… I held a series of talks with the attorney general and security officials and realized that if the emergency regulations are not approved… the State of Israel would come to a standstill… I could not agree to harm Israel's security and decided to take responsibility and call new elections.”4

This statement lays bare what Israel generally tries to conceal—that the very structure of the regime is premised on apartheid regulations. The Prime Minister felt obliged to resign from the most powerful position in the country in order to maintain the apartheid order. The ensuing November 2022 elections returned to power the previous PM—Benjamin Netanyahu, who has openly supported annexation of parts of the West Bank, and whose main coalition partners are parties representing West Bank Jewish settlers. Upon swearing in his sixth government Netanyahu twitted on 29.12.2022: “The Jewish people have an exclusive right to all areas of the Land of Israel... the government will promoted and develop settlement in all parts of parts of the Land... Galilee, Negev, Golan and Judea, and Samaria.” Hence, apartheid in Israel/Palestine is set to deepen even further in the coming years.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^These definitions are summarized on the basis of entries in the Oxford Dictionary of Political Concepts and the Blackwell Dictionary of Human Geography.

2. ^https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/05/un-experts-alarmed-israel-high-court-ruling-masafer-yatta-and-risk-imminent

3. ^https://www.juancole.com/2022/06/israels-apartheid-government.html

Adva Center for Social Equality (2021). Israel – Social Report 2021. Available online at: https://adva.org/en/socialreport2021/ (accessed December 15, 2022).

Al-Haq (2020). Annual Report on Human Rights Violation. Available online at: https://www.alhaq.org/monitoring-documentation/17950.html (accessed December 15, 2022).

Al-Haq (2021). The Legal Architecture of Apartheid. Available online at: https://www.alhaq.org/advocacy/18181.html (accessed December 15, 2022).

Amnesty International (2022). Israel's Apartheid Against Palestinians. Available online at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2022/02/israels-system-of-apartheid/ (accessed May 26, 2022).

Anderson, J. (2016). Ethnocracy: exploring and extending the concept. Cosmopolit. Civ. Soc. 8, 1–29. doi: 10.5130/ccs.v8i3.5143

Ariely, G. (2021). Israel's Regime Untangled: Between Democracy and Apartheid. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108951371

Barda, Y. (2018). Living Emergency: Israel's Permit Regime in the Occupied West Bank. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781503605299

Ben-Natan, S. (2022). The Apartheid Reports: A Paradigm Shift on Israel/Palestine (Part I). Available online at: http://opiniojuris.org/2022/04/12/the-apartheid-reports-a-paradigm-shift-on-israel-palestine-part-i/ (accessed May 26, 2022).

Bimkom (2008). The Prohibited Zone: Israeli Planning Policy in Palestinian Villages in Area C. Available online at: https://bimkom.org/wp-content/uploads/the-prohibited-zone-heb-2.pdf (accessed December 15, 2022).

Bishara, A. (2022). Crossing a Line: Law, Violence and Roadblock for Palestinian Political Expressions. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781503632103

B'Tselem (2012). Under the Guise of Legality: Israel's Declaration of State Lands in the West Bank. Available online at: https://www.btselem.org/download/201203_under_the_guise_of_legality_eng.pdf (accessed December 15, 2022).

B'Tselem (2021). A Regime of Jewish Supremacy From the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea: This Is Apartheid. Available online at: https://www.btselem.org/publications/fulltext/202101_this_is_apartheid (accessed May 26, 2022).

Busbridge, R. (2018). Israel-Palestine and the settler colonial ‘turn': from interpretation to decolonization. Theor. Cult. Soc. 35, 91–115. doi: 10.1177/0263276416688544

Clarno, A. (2017). Neoliberal Apartheid: Israel/Palestine and South Africa After 1994. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226430126.001.0001

Erakat, N. (2019). Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781503608832

Erakat, N., and Reynolds, J. (2022). Understanding apartheid. Jewish Current. p. 107–118; Available online at: https://jewishcurrents.org/understanding-apartheid

Fakhoury, A. (2021). Palestinian arab politics in the netanyahu era: a comparison and conflict between Odeh's politics and Abbas' politics. Theor. Crit. 53, 187–202 (Hebrew).

Farsakh, L. (2015). Apartheid, Israel and Palestinian Statehood in Pappe. Israel and South Africa, Ist Edn. doi: 10.5040/9781350220898.ch-005

Ghanem, A. (2019). Israel in the Post Oslo Er: Prospects for Conflict and Reconciliation with the Palestinians. London: Routledge.

Greenstein, R. (2020). Israel, Palestine and Apartheid, Insight: Challenging Ideas. Available online at: https://www.insightturkey.com/articles/israel-palestine-and-apartheid (accessed December 15, 2022).

Halper, J. (2021). Decolonizing Israel, Liberating Palestine. London: Pluto. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1dm8d20

Human Rights Watch (2021). A Threshold Crossed. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/04/27/threshold-crossed/israeli-authorities-and-crimes-apartheid-and-persecution (accessed May 27, 2022).

Jamal, A. (2008). “On the burdens of racialized time,” in Racism in Israel, 1st Edn, eds Y. Shenhav and Y. Yonah (Jerusalem: Van Leer), 348–380.

Jamal, A. (2016). Constitutionalizing sophisticated racism: Israel's proposed nationality law. J. Palestine Stud. 45, 40–51. doi: 10.1525/jps.2016.45.3.40

Jamal, A. (2020). “Introduction,” in The Politics of Inclusion and Exclusion in Israel-Palestinian Relations. Tel Aviv: Walter Lebach Institute, Tel Aviv University.

Kedar, A., Amara, A., and Yiftachel, O. (2018). Emptied Lands: A Legal Geography of Bedouin Rights in the Negev. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

Kedar, A. S., and Yiftachel, O. (2006). “Land regime and social relations in Israel,” in Realizing Property Rights: Swiss Human Rights Book, eds H. de Soto and F. Cheneval (Zurich: Ruffer & Rub Publishing House), 127–144.

Kedar, S. (2016). Dignity takings and dispossession in Israel. Law Soc. Inq. 41, 886–87. doi: 10.1111/lsi.12208

Khalidi, R. (2018). Israel: “A Failed Settler-Colonial Project.” Available online at: https://www.palestine-studies.org/en/node/232079 (accessed May 27, 2022).

Lustick, I. (2019). Paradigm Lost: From Two-State Solution to One-State Reality. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Lustick, I. (2020). “One State Reality: Israel as the state ruling the population between Mediterranean Sea and Jordan River,” in Israel and Palestine: A One State Reality, eds M. Barnett, N. Brown, M. Lynch, and S. Talhami. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press).

Lynch, M., Barnett, M., and Brown, N. (2020). Israel and Palestine: A One State Reality. Available online at: https://pomeps.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/FINAL-POMEPS_Studies_41_Web-rev2.pdf (accessed December 15, 2022).

Mamdani, M. (2020). Neither Settler nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. doi: 10.4159/9780674249998

Peteet, J. (2017). Space and Mobility in Palestine. Bloomington, IN: University of Indiana Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt1zxxznh

Radday, F. (2022). Amnesty's distorted framing of an evolving tragedy. Palestine-Israeli J. Available online at: https://www.pij.org/articles/2172/amnestys-distorted-framing-of-an-evolving-tragedy

Rome Statute. (1998; 2002). Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. New York, NY: UN general Assembly.

Sa'adi, A. (2016). Stifling surveillance: Israel's surveillance and control of the palestinians during the Military Government Era. Jerusalem Quart. 68, 35–55.

Sabagh-Khoury, A. (2021). Tracing settler colonialism: A genealogy of a paradigm in the sociology of knowledge production in Israel. Polit. Soc. 50, 44–83. doi: 10.1177/0032329221999906

Sadiq, K. (2017). Limits of Legal Citizenship: Narratives from South and Southeast Asia. Durham: Duke University Press.

Sartre, J. P. (1963). “Preface,” in The Wretched of the Earth, eds F. Fanon and J. P. Sartre (New York, NY: Grove Press), 7–31.

Scheindlin, D. (2018). An Israel-Palestinian Confederation Can Work, Foreign Affairs. Available online at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/06/29/an-israeli-palestinian-confederation-can-work/ (accessed December 15, 2022).

Shafir, G., and Peled, Y. (2002). Being Israeli: The Dynamics of Multiple Citizenship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139164641

Shmaryahu-Yeshurun, Y. (2022). Retheorizing state-led gentrification and minority displacement in the Global South-East. Cities. 130, 103881. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2022.103881

Smooha, S. (1997). Ethnic democracy: Israel as a prototype. Israeli Stud. 2, 198–241. doi: 10.2979/ISR.1997.2.2.198

Stasiulis, D., and Yuval-Davis, N. (1995). Unsettling Settler Societies: Articulations of Gender, Race, Ethnicity and Class. London: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781446222225

Sultany, N. (2014). “Liberal zionism, comparative constitutionalism, and the project of normalizing Israel,” in On Recognition of the Jewish State, eds H. Ghanim (Ramallah: Madar Center), 91–109. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2405372

Tawil-Souri, H. (2016). Surveillance sublime: security state in Jerusalem. Jerusalem Quart. 68, 65–78.

Tzfadia, E., and Yiftachel, O. (2021). Displacement from the city: a Southeastern view. Theory Crit. 54, 59–86.

UN Apartheid Convention. (1973). International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid. New York, NY: UN General Assembly.

Veracini, L. (2015). What can settler colonial studies offer to an interpretation of the conflict in Israel–Palestine? Settler Colonial Stud. 5, 268–271. doi: 10.1080/2201473X.2015.1036391