95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 19 December 2022

Sec. Dynamics of Migration and (Im)Mobility

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.974727

This article is part of the Research Topic Migration and Integration: Tackling Policy Challenges, Opportunities and Solutions View all 13 articles

Migrants play a significant role in European labor markets and are used as sources of “cheap labor”; often being disproportionately represented in low-wage, poor conditions, or otherwise precarious positions. Past research has suggested that the process of migrants being filtered into these low-end occupations is linked to institutional factors in receiving countries such as immigration policy, the welfare state and employment regulation. This paper calculates the extent of migrant marginalization in 17 European countries and uses qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and regression modeling to understand how institutional factors operate and interact, leading to migrant marginalization. The QCA showed that when a country with a prominent low skills sector and restrictive immigration policy is combined with either strong employment protection legislation or a developed welfare state, migrants will be more strongly marginalized on the labor market. The results of the statistical analysis largely aligned with the idea that restrictive immigrant policy by itself and in combination with other factors can increase marginalization.

Immigrants play a vital role in the economies of many western European countries and have done for decades, even centuries (Van Mol and Valk, 2016). Indeed, as Robinson puts it: “There has never been a moment in modern European history (if before) that migratory and/or immigrant labor was not a significant aspect of European economies” (Robinson, 1983, p. 23). Some perspectives stress global differences in wage-levels and prosperity between countries and processes of empire as central to explaining migrants' place in Western labor markets; firms in the global North pursue strategies of “labor arbitrage” at home for jobs that they haven't been able to outsource to countries with lower wages, and gain access to cheaper labor via migration (Wills et al., 2009; Smith, 2016). A significant amount of these migrant workers are used as a source of “cheap labor”: for jobs with low levels of pay, benefits, and employment protection (King and Rueda, 2008; Emmenegger and Careja, 2012). Ruhs and Anderson (2010) say that similar to how jobs previously performed by men become “women's jobs,” so too can jobs become “migrant jobs” and thus accrue lower social status, with such job demarcations and stigmatizations becoming structurally embedded with time (Ruhs and Anderson, 2010, p. 39). There has been significant discussion of the particularly unfavorable circumstances of migrant workers in European labor forces, with a number of factors combining and leading to migrants being relegated to a secondary labor market, working within a context of a new “migrant division of labor,” or in situations of severe precariousness more “extreme” or “hyper” than that of locals' (Piore, 1979; May et al., 2007; Porthé et al., 2010; Lewis et al., 2015).

This paper follows critiques of human capital and neoclassical approaches that overly focus on skill levels and supply-side factors and miss the importance of demand-side effects that shape labor market dynamics (e.g., Rubery, 2007; Grimshaw et al., 2017). Within the narrower but undertheorized frame of migrants' labor market and poverty outcomes, it has been shown that we need to go beyond mere migrant composition to explain their socioeconomic position, and also consider the broader institutional context (Büchel and Frick, 2005; Barrett and Maître, 2013; Hooijer and Picot, 2015; Eugster, 2018; Guzi et al., 2021; Krings, 2021; García-Serrano and Hernanz, 2022).

Contextual and institutional factors have been shown to interact to shape dynamics on national labor markets that can differentially affect migrants and locals: specifically the interplay of immigration policy, welfare policy and labor market regulation has been repeatedly highlighted as how migrants find themselves marginalized (May et al., 2007; Ruhs and Anderson, 2010; Pajnik, 2016). While employment regulation and welfare state elements are relevant for all people living in a country, migrants' access to and use of such institutions can be modulated by their status as migrants and the related forces this exerts on them. Eugster (2018) emphasizes that the interaction of such institutions is of large importance: e.g., even if a migrant has formal access to social rights or employment regulations, if they face negative consequences for receiving benefits, have less freedom to choose their employer/industry, or are segmented into “outsider” jobs that are not covered by employment legislation, their effective capacity to benefit from these institutions is less than locals'.

The goal of this paper is to understand how such institutional factors shape the extent to which migrants end up performing the least desirable jobs in Europe. Previous research using standard statistical methods has illuminated the presence and relevance of certain contextual factors. This paper adds to this body of work using similar methods with different specifications, and enriches our understanding in a novel way by identifying complex combinations of contextual factors by conducting a qualitative comparative analysis (QCA).

The next section begins with the theoretical frameworks that are drawn upon to conceptualize the situation of migrants in European labor markets, followed by previous empirical findings on the topic that inform the decision to focus on institutional-level explanations and selection of causal conditions. After this, the sample and methods are outlined, including how the outcome is derived and causal conditions operationalized. The results of the QCA analyses and a focus on two country cases follow. The results of the regression analysis are then presented. The paper concludes by considering the results' implications for the broader body of work on migrants' labor market outcomes and related institutional factors, as well as addressing limitations of the research.

Before engaging with the main theoretical and empirical works that this study engages with and is based on, a note on the term “migrant/immigrant” as conceptualized throughout and used in the analysis. “Immigrant/migrant” is not a naturally occurring category that can be defined from a completely objective standpoint, but is rather a particular and partial encircling of the various human mobilities that constantly occur (Favell, 2022). Previous research has operationalized “migrant”/”immigrant” using a number of approaches depending on the perspective and interest of the researchers. Indeed in the public discourse the term is understood in various ways at different points in time and in specific contexts. Given the topic of this paper is immigrants at the bottom end of contemporary European labor markets and their being a source of “Cheap Labor” for European economies, something that is inexorably tied to historical colonial and economic linkages between countries and regions globally (Cohen, 1988), migrant is primarily taken here to mean people from outside these core wealthy countries1. It's assumed that for migrants from these wealthier regions there are different mechanisms and causes at play, and that in trying to understand the phenomenon of migrants being used as “Cheap Labor,” theoretically migrants from wealthy countries are not part of the story. Fernández-Macías et al. argue that including such groups stretches the idea of “migrant worker” which is commonly understood as migrants from less-developed regions (Fernández-Macías et al., 2012, p. 113). As well as the common understanding that “immigrants” and “expats” are treated differently, there is also empirical research highlighting that these groups have qualitatively different experiences. A number of studies have empirically found migrants from North and Western Europe, North America and Australasia to fare better than those from CEE and non-EU countries, on various labor market outcomes, sometimes even surpassing nationals (Fernández-Macías et al., 2012; Felbo-Kolding et al., 2019; Fellini and Guetto, 2019; Heath and Schneider, 2021; Felbo-Kolding and Leschke, 2022).

Different schools of migration theory underscore how global inequalities drive migration dynamics in such a way that people from less wealthy countries end up working jobs at the low end of the labor market in wealthy destination countries (Massey et al., 1993). Neoclassical approaches see things in terms of equilibriums of wages/conditions and individual-level gain-maximizing decision making, so significant gaps in prosperity between countries will result in migrants from these places as having different frames of reference and perspectives to locals on what constitutes a job worth taking, given the higher potential for gains in terms of wages, wealth or living standards. Structural theoretical frameworks—e.g., dual labor market theory, world systems theory— seeing things more in terms of the macro-level forces and the structure of different modern economies point to labor demand in parts of European economies or the lack of quality employment opportunities in sending countries (Massey et al., 1993). However, structural accounts (such as Piore, 1979) also contain this mechanism that migrant workers accept these lower end jobs due to lower expectations in terms of wages and conditions.

A further element discussed throughout the paper are the pressures created by legal structures in the receiving countries via immigration policy, that often act more strongly upon people from countries outside the wealthy core (e.g., ease of getting a visa); which makes sense if one sees bordering processes as contributing to the reproduction of global inequalities (Favell, 2019).

Migrants can be seen as part of broader developments that have occurred since the 1980s, as those exposed most strongly to reforms at the workplace: “while subcontracting is now the paradigmatic form of employment across the world, the migrant is the world's paradigmatic worker” (Wills et al., 2009, p. 6). Wills et al. point to neo-liberal management of the domestic economy as a key factor in driving down wages and working conditions at home, while the export of neo-liberal policies create the need and desire for people abroad to migrate to look for work (Wills et al., 2009). Several frameworks present migrants as a group that seem to be at a sort of “cutting edge” or test subjects of negative developments for labor within Western societies. Nobil Ahmad says in many approaches dealing with precarious work, illegal migrants are seen as the emblematic precarious workers—an extreme case that experience the emerging neoliberal social order at its worst (Nobil Ahmad, 2008, p. 303). In Standing's work on “the Precariat” he says migrants make up an important part numerically and qualitatively of this emerging class, simultaneously being subjected to and blamed for the increasing insecurity and uncertainty we observe (Standing, 2011). Lewis et al. employ the notion of “hyper-precarity” to differentiate exploited migrants' situation from that of the precariat class more generally, as they are at a nexus of both employment and immigration precarity, leading to unfreedoms and lack of alternatives to submitting to exploitative and unfavorable working arrangements (Lewis et al., 2015, p. 588). In line with Sassen's influential work on global cities as command centers of global capitalism with stark job polarization, studies in London have spoken of a “Migrant division of Labor” to describe how the city is reliant on migrants to perform dirty work necessary for its functioning (Sassen, 1991; Datta et al., 2007; May et al., 2007; Wills et al., 2009).

Geddes and Scott (2010) argue that structurally, migrant workers function as a hidden “subsidy” to producers in the UK low-wage agricultural sector, and are seen as a qualitatively distinct form of labor. If we use the concept of a labor market, where people and their potential labor power are the commodities, then according to this analysis the buyers assess the migrant commodities differently from non-migrant ones. Pajnik points out that in EU-level debates and policy, migrants are viewed as mere commodities: skilled migrants as opportunities for economic development; low-skilled migrants as solutions to labor market shortages caused by nationals' unwillingness to carry out “3D” (dangerous, demanding, dirty) jobs (Pajnik, 2016, p. 160).

Migratory routes in Western Europe have had a number of permutations: some countries implemented “guest-worker” schemes to fill labor shortages; others facilitated labor from former colonies; and continuing until today there are programs to attract migrants for sectoral labor demands, often spurred employers associations (Sassen, 1991; Menz, 2008; De Haas et al., 2020). These migrants, who are generally able-bodied and young, have influenced the makeup of European labor forces and the likelihood of success for different industries and economic activities across the continent (Ruhs and Anderson, 2010). Certain industries, such as horticulture or social care in the UK (Geddes and Scott, 2010; Evans, 2021), could not exist in their current form without migrant workers to rely on.

Ubalde and Alarcón (2020) find a gap between the occupational status of migrants and locals, and the difference increases when only comparing with non-European migrants. These results were after controlling for human capital, acculturation, family background and sociodemographic elements, concluding that discriminatory factors in the European labor market do persist. Gorodzeisky and Richards (2013) summarize that there is a high degree of labor market segmentation between local and migrant workers in Europe, with the latter more likely to be concentrated in less-favorable sectors characterized by longer hours, lower pay, less employment stability and less skill development and promotion opportunities. The sectors migrants tend to be concentrated in are also those where unions are least likely to be present (Gorodzeisky and Richards, 2013).

Emmenegger and Careja (2012) show that in Germany, UK and France immigrants are disproportionately employed in sectors impacted by outsourcing to secondary labor markets and that are the most dualized (e.g., construction, restaurants, logistics, household, cleaning). Ambrosini and Barone (2007) report segregation into low-paying non-unionized job sectors with limited upward mobility, and note that these are often also unhealthy and dangerous roles. A number of other authors and literature reviews have concluded that migrants are overrepresented in jobs characterized by hazardous tasks, occupational risks, physically-demanding work, poor working conditions, uncertainty and low autonomy (González and Irastorza, 2008; Benach et al., 2010; Sterud et al., 2018; Arici et al., 2019).

The 2019 OECD Migration Outlook found the proportional gap of in-work poverty has increased over the last number of years, with 18% of working migrants in the EU living below the poverty threshold in 2017, compared to 8% of nationals (OECD, 2019a). The number of migrants working part-time and wishing to work more hours has grown (especially for women migrants), as has the gap in over-qualification rates (OECD, 2019a).

Burgoon et al. (2012) note that foreign-born workers tend to be easier for employers to pressurize and more difficult to organize than native workers. This is for several reasons, including being less familiar with the regulations and rights for workers, and having precarious legal positions (often related to the immigration policy they're subject too) leading them to be more docile in dealing with employers. Bridget Anderson et al. have considered how employers fuel the situation, what advantages they see in migrant labor, and the discourses that arise describing migrant workers. Anderson et al. (2006) showed that employers are aware that by hiring immigrants they often get high-quality, yet low-wage workers, who are more likely to accept more negative conditions such as unsociable shift times. Ruhs and Anderson (2010) describe how as employers hire migrant workers for these discount prices and company-favorable conditions over time, they are not forced to pursue other strategies of creating efficiencies that they otherwise would. They stress that labor demand and supply are not generated independently of each other, and that employers form expectations of and a reliance upon this source of labor. They show how the word “skills” is used in an ambiguous way and differs across contexts, sometimes referring to credentialized qualifications and soft skills, other times more personal characteristics and behavioral traits (e.g., “hard-working,” “friendly,” “caring” etc.). They warn that discussions of “skills,” “skill-shortages” and “skill-based immigration policies” should be scrutinized: that sometimes what is really meant by skills are traits and behaviors related to employer control over the workplace, e.g., a willingness to accept certain wages and working conditions (Ruhs and Anderson, 2010, p. 6). As well as determining whether workers have the required skills, employers assess what employment relations and conditions the workers will tolerate: what type of shifts they're willing to work, how easy they are to discipline, how compliant and cooperative they are, what levels of stress and emotionally draining work they can handle (Ruhs and Anderson, p. 20). Other research has shown that migrants, especially new arrivals, are sometimes seen as harder workers than the local labor supply, and as being prepared to work longer hours and generally more reliable, due to their lack of choice and undeveloped aspirations (MacKenzie and Forde, 2009).

Others have discussed the absence of union activity and collectivization by migrants, which might seem like the obvious strategy to combat and improve their lot at work. Rodriguez and Mearns (2012) say that due to legal insecurities and fear of repercussions if they were to enact political agency, migrant workers are unlikely to engage in trade unionism. King and Rueda describe how for several reasons “cheap labor” often fails to develop political strength and identities based in occupation, but instead according to their migration status, gender or ethnicity (King and Rueda, 2008, p. 293). This is said to be due to their political weakness in capitalist democracies, because they often move rapidly between jobs and don't have time to build ties, and how they have become politicized and treated as suspects of ideological extremism or objects of hostility from anti-immigrant movements (King and Rueda, 2008).

Emmenegger et al. (2012) identify migrants' limited political and civil rights, widespread discrimination and language problems as micro-level processes that form migrant workers into a qualitatively distinct group on the labor market. Discrimination against migrants (especially non-EU) in the hiring process has been found in multiple country studies, sometimes using experimental research methods (Nobil Ahmad, 2008; Carlsson, 2010; Weichselbaumer, 2015). The International Labor Organization report that in studies on a number of developed western nations, around one third of vacancies tested were closed to young male applicants of migrant or ethnic minority background, and that these discrimination rates were higher in smaller- and medium-sized businesses and within the service sector (International Labor Conference and Internationales Arbeitsamt, 2004). They also found irregular migrants were preferred by employers as they were willing to work for lower wages, short periods and perform hazardous tasks (International Labor Conference and Internationales Arbeitsamt, 2004).

In addition to general criticisms of orthodox/neoclassical and human capital approaches' to the labor market (Piore, 1979; Grimshaw et al., 2017), others have pointed out the limitations of such approaches' explanatory power specifically when it comes to migrants' labor market outcomes (McGovern, 2007; Ruhs and Anderson, 2010; Krings, 2021). Rather than seeing economic migrants as quintessential “homo economicus,” these authors highlight the importance of institutional elements of labor markets and the importance of the state. Büchel and Frick found that even when controlling for the socioeconomic characteristics of people within the household and individual-level indicators related to integration (years since migration, intermarriage), cross-country differences in migrants' economic success persisted, leading them to suggest that institutional-level factors such as access to the labor market and aspects of social security related to citizenship or immigration play an important role in migrants' economic success (Büchel and Frick, 2005). Devitt (2011) has highlighted how receiving country institutions shape domestic demand for migrant labor, including how domestic (under)supply can impact this demand.

Given migrants in low-end work in Europe is a topic that multiple strands of social research can provide insights about—migration, welfare state, varieties of capitalism, labor market economics, employment regulation—it is not surprising to find that many authors have stressed the overlapping and interacting of certain contextual and institutional factors in explaining the situation. In trying to understand precarious migrant workers (especially undocumented), Anderson et al. say we should do away with the overly-simplified image of the individual “abusive employer,” but recognize the active role of the state in structurally constructing these vulnerable groups and the important effects that employment and immigration legislation have in providing employers extra mechanisms of control over migrant employees (Anderson et al., 2006, p. 313). May et al. (2007) argue we need to consider how the welfare state regime interacts with other areas of state-craft like labor market (de)regulation and immigration policy to foster these labor market dynamics, in the context of immigrants' overrepresentation in low-paid jobs in London. Similarly, Corrigan (2014) lists citizenship and immigration policies, social welfare policies and labor market policies as the three institutional domains of the integration of migrants. Speaking of the structural demand for migrant workers in the UK context, Ruhs and Anderson (2010) say that this demand is created not just by immigration policy, but also other broader regulatory, institutional, and social policy systems.

Introducing the concept of migrant “hyper-precarity,” Lewis et al. (2015) posit that this state emerges from the interplay between neoliberal labor markets and restrictive immigration regimes. McGovern (2012) advocates that Piore (1979) influential account of the segmentation of immigrants in the labor market be extended to encompass the role of the state and immigration policies. Similarly, Pajnik (2016, p. 159) argues that labor market and migration regimes over-determine migrants' lives, and that neoliberal or market-oriented policies favoring “flexibility” in employment relationships have been accompanied by provisions that marginalize workers' rights, the shrinking and individualization of the welfare state, and the deregulation and wage-reduction in sectors that haven't been outsourced—that migrants often find themselves in (e.g., construction, agriculture, services). She says we need to consider the migration and labor market orders of workfare societies to intersectionally analyze migrant statuses, and the policies and industries of migrant work (Pajnik, 2016, p. 162). Krings (2021) while looking at migrant low-wage employment in Germany highlights that labor market outcomes of migrants are shaped by immigration rules and product market regulations, not just wage-setting institutions and employer behavior.

McGovern (2012) draws attention to the fact that by limiting the freedom of migrant workers to enter and by placing various controlling mechanisms on the nature and conditions of the work they can do, countries prevent individuals from freely selling their labor power to the highest bidder, despite markets (including labor markets) remaining unobstructed being a central dictum of neoliberalism. According to McGovern, this has created a legally-imposed and enduring form of labor market inequality negatively impacting migrants. After qualitatively studying the experiences of immigrant workers in Spain and comparing them to Spanish workers', Porthé et al. (2010) conclude that according to seven dimensions of precariousness, immigrant workers are pushed into situations of “extreme precariousness.” This is said to be due to them suffering an “accumulation of factors of vulnerabilities,” a vector including migrant status and socio-economic position (Porthé et al., 2010, p. 423).

Migrant poverty levels are closely related to labor market position, and here also the composition of migrants has been found to be insufficient in explaining poverty rates across countries. Using qualitative comparative analysis (QCA), Hooijer and Picot (2015) study migrant disadvantage in terms of risk-of-poverty, specifically how welfare state type, employment regulation and immigration policy influence this disadvantage. They find a generous welfare state alone is not enough to prevent poverty gaps between migrants and natives, as these rights can be strongly differentiated where countries receive high amounts of humanitarian immigration. At the same time, they find considerable gaps where the welfare state is lean and labor market deregulated—highlighting how the effect of certain institutions are conditional on others'.

The institutional component of migrant marginalization in the labor market (whose empirical existence is more strongly established) is under-theorized, and most work grappling with it has thus far focused on single policy areas, despite the above-mentioned emphasis on institutional fields overlapping and interacting to bring about these outcomes (Guzi et al., 2021). Some have studied institutional effects on migrant employment and unemployment rates (e.g., Huber, 2015), but as has been shown in above works illustrating the often bleak and exploitative situation for working migrants, just being employed doesn't assure sufficient quality of life or security. Two recent studies largely using a Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) framework have directly investigated institutional effects on migrant-native gaps in labor market outcomes, beyond individual-level composition (Guzi et al., 2021; García-Serrano and Hernanz, 2022). In terms of job quality, García-Serrano and Hernanz found more coordinated wage bargaining, union presence, and stricter EPL tended to disadvantage migrants vis-à-vis natives, while integration policies and government involvement in minimum wage reduced these gaps (García-Serrano and Hernanz, 2022). They also emphasized that the same policy wont bring identical results, but must be adapted for national contexts (García-Serrano and Hernanz, 2022). Guzi et al. found that EPL increases the gap between migrants and natives in terms of low-skill employment, while certain welfare spending measures decreased outcome gaps (Guzi et al., 2021). These works make great strides in advancing this field of knowledge, but in their use of frequentist statistical methods, potentially leave some of the complex interaction of institutional factors unexplored (Ragin, 2010). For this reason, this paper uses a QCA approach: to uncover not only which institutional factors are at play, but also how they interact with each other to bring about migrant marginalization. In allowing for conjunctural causation, equifinality and asymmetric causation, QCA is ideal for investigating exactly these complex mechanisms, not just their existence in isolation (Oana et al., 2021).

Having reviewed this literature, it is expected that where immigration policy is more restrictive, we would find a higher migrant marginalization and segmentation into lower-end jobs. It is primarily via this policy field that migrants' statuses are determined, and thus the stronger the restrictions, the more migrants are differentiated from locals' and we could expect patterns of segmentation to develop. How this combines with the welfare state and employment regulation to shape marginalization is difficult to predict, given these domains affect both migrant and national side of the equation. For example, while Sainsbury (2012) found that the type of welfare state a country has matters for migrants' social rights and decommodification, a leaner welfare state could potentially preclude the option for locals to refuse low-end jobs, thus leading to a lower gap between migrants and locals. Just as a stronger welfare state, if coverage is differentiated, could create a viable option for locals of a country to not take up work in low-end sectors, this could also foster a need to find migrant workers for these positions, potentially creating a larger migrant-local gap. Similarly, a highly deregulated labor market could create equally insecure conditions for migrants and locals alike, whereas migrants could potentially be unprotected in a country with high employment protection, due to their migrant status, visa or industry. Rather than working in a single causal direction, it is expected that EPL and the welfare state will be conditioned on the broader labor market and migration policy.

The primary data source is the European Union Labor Force Survey (EU LFS), provided by Eurostat. The EU LFS is a large cross-sectional household sample survey providing quarterly results on labor participation of people aged 15 and over as well as on persons outside the labor force. The data includes people living in private households; persons carrying out obligatory military or community service are not included in the target group, nor persons in institutions/collective households (Eurostat., 2020). To ensure a big enough sample size of migrant respondents in all countries without spreading the cross-section over too long a period, data from the 2017 and 2018 waves were combined, and the sample restricted to those of the commonly-used definition of being working-aged: 20–64 (OECD, 2020)2. A main advantage of EU-LFS is the large sample sizes allowing good representation of countries' migrant populations. A table with information on the size of the raw sample and subsequent steps excluding observations is provided in Supplementary material.

The groups compared are people born in country, to migrants working in that country. The migrant sample includes respondents not born in the survey country, nor the EU-15, North America or Australasia. The choice to operationalize the migrant group in this way is based on theoretical and empirical considerations as discussed at the beginning of the background section, and has similarly featured in methods employed by previous research (Kogan, 2006). Since according to both neo-classical and structural-macro theories of migration wage and prosperity gaps between countries are key in explaining migration (Massey et al., 1993), and these gaps contribute to the forces leading to migrants accepting undesirable jobs and unfavorable work conditions, migrants from the aforementioned regions were excluded due to the absence of these prominent inter-country wealth gaps.

Within this framework of wealthy countries engaging in labor arbitrage, migrants are not here limited or divided to smaller groups (e.g., migrants on particular types of work visas, refugees, or migrants from certain countries/religions) but include all people who have moved, since these broader forces stemming from global inequalities are relevant to all such sub-groups and they will generally all need to engage with the labor market. In a similar vein, “people with migration background” or “second/third generation migrants” are not included in the concept of migrant used here. This is not to deny that these groups can face real discrimination/marginalization, nor that there is overlap between what these groups and “first generation migrants” face related to the labor market; but this paper is not aimed primarily at dynamics of general racial or ethnic discrimination and the related processes that would be involved in explaining their labor market outcomes. Additionally, these groups are not as differentiated in legal terms as non-citizens and thus the institutional mechanisms that are central are not as relevant: e.g., differentiated access to the welfare state or being subject to immigration policy doesn't apply to “second generation migrants” as much as to people who have immigrated.

The country cases included are the EU-15 (including the United Kingdom), plus Norway and Switzerland. The main two reasons behind this are first, the majority of theoretical and empirical works handling the relevant contextual factors—the welfare state, migration (policies and macro explanations), employment systems and regulation—are based upon similar samples of wealthy Western European countries (Esping-Andersen, 1990; Ferrera, 1996; Freeman, 2006; Devitt, 2011; Hooijer and Picot, 2015). Second, the historical and institutional differences, as well as differences in the histories of migration, between these countries and the excluded post-socialist ones are too vast to usefully include them in the analysis. Settler colonial countries such as the US, Canada and Australia might share similarities, however their immigration systems and histories are also too distinct from the selected European cases to be included.

As discussed in the literature review, the situation of migrants in the workforce has been said to be shaped by numerous institutional fields: fields which have however been theorized and researched largely in isolation from one another (e.g., Boucher and Gest, 2015). Given that research has consistently stressed the multitude and interaction of institutional factors, qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) was chosen as a method to investigate how certain institutional factors bring about migrant marginalization. The paper follows a growing number of research works that employ both standard statistical analyses and QCA to benefit from the advantages of both approaches (Meuer and Rupietta, 2017). On the one hand the standard statistical analysis is variable-oriented and relies on correlational analysis, comparing across cases, QCA is based on set theory, case-oriented, and uses Boolean algebra to compare between cases (Meuer and Rupietta, 2017). While interaction effects within a standard frequentist/regression analysis approach can be used to investigate the interaction and combination of variables, QCA provides a flexible strategy to handle causal complexity and potential combinations are given central importance in the method. The core motivation of QCA is to account for the complex interplay of different factors bringing about an outcome of interest, and it is particularly suitable for addressing causes-of-effects questions (Oana et al., 2021). QCA incorporates the three core elements of causal complexity: assuming and allowing for conjunctural causation, equifinality and asymmetric causation, where different sets combine with the logical operations AND, OR and NOT, respectively (Schneider and Wagemann, 2012; Oana et al., 2021). QCA uses Boolean algebra to analyze which causes, or combinations of causes, are necessary or sufficient for a given outcome—the outcome here being migrant marginalization.

The outcome of the QCA was first calculated using statistical methods, as is commonly done (Meuer and Rupietta, 2017). Logistic regression models were used to estimate the levels of migrant marginalization in each country (see Section 3.3.6). The logistic regressions were performed in Stata 15, and all QCA steps performed with R using the “QCA” and “SetMethods” packages (Oana and Schneider, 2018). The selection of causal conditions was based on prior theoretical knowledge as outlined in the background section and further in the following section. This is a fuzzy set QCA (fsQCA), which allows cases to have partial membership scores in a set, ranging from 0 to 1 (as opposed to crisp set QCA where all cases are coded to either fully in or out: 1 or 0). Following the calibration (see Section 3.3.7)—that is, assigning country cases fuzzy-set membership scores in all conditions and the outcome (full details in Supplementary material)—the core elements of a QCA are performed: constructing a truth table, and analyses of necessity and sufficiency. Constructing the truth table involves three steps: the identification of all logically possible configurations; the assignment of each case to one of these truth table rows based on its membership scores; and the definition of the outcome values for each row (Schneider and Wagemann, 2012). The truth table is constructed so that we can investigate which conditions (or combinations of conditions) are sufficient for bringing about the outcome, via the logical minimization of the truth table (i.e., analysis of sufficiency) (Schneider and Wagemann, 2012). While sufficiency is about “whenever cause(s) X is present, outcome (Y) is also present” (Y is a superset of X), statements of necessity can be read as—“wherever Y is present, X is also present” (Y is a subset of X). After the “analytic moment” (Boolean minimization of the truth table) two brief case studies are undertaken to evaluate and further interpret results from the formal QCA analysis.

Some authors have criticized QCA on various grounds, including failure to produce correct causal pathways in simulated datasets (Lucas and Szatrowski, 2014). Defenses against this line of criticism have argued that it ignores the incorporation of case-based and other forms of substantive knowledge inherent to QCA as an approach (Ragin, 2014), as well as criticized the application of the method in tests (Ragin, 2014; Baumgartner and Thiem, 2020) and the expectation of QCA to recover regression models (Baumgartner and Thiem, 2020). The case knowledge used throughout the research process and in the case studies in this article is intended to ensure a fruitful “dialogue with the data” that should be part of a QCA (Rihoux and Lobe, 2013), while the use of established statistical analysis provides a valuable alternative, and here argued complimentary, approach to further our understanding of the topic.

Previous literature has highlighted the role of the welfare state, employment regulation and immigration policy as factors important to the situation of migrants in precarious and low-wage work around Europe, and thus form the first three causal conditions of the QCA. The fourth condition, the extent of low-skill employment in a country, is another important element and is further justified below. In-depth knowledge of cases and concepts minimize ex ante measurement error and threats to internal validity (Thomann and Maggetti, 2020). The welfare state and immigration policy causal conditions are based on in depth theoretical knowledge of cases (Esping-Andersen, 1990; Ferrera, 1996; Helbling et al., 2017), and the OECD employment protection index was compiled using the Secretariat's reading of statutory laws, collective bargaining agreements and case law as well as contributions from officials from OECD member countries and advice from country experts (OECD, 2020).

To differentiate countries by their welfare state systems, the well-known conceptual framework of welfare state regimes based on the work of Esping-Andersen (1990) is used. Since the original typology has been criticized for not adequately capturing the characteristics of Southern European countries, a fourth “southern” model was included on top of the three original regime types of “liberal,” “conservative” and “social-democratic” (Ferrera, 1996). This approach was chosen since other methods of operationalizing the welfare state, such as social spending as percentage of GDP, are less holistic and fail to understand a welfare state's role or character within the broader national context, and the typology framework has proven to be a useful, popular and easily-understood theoretical approach for comparing countries (Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser, 2011).

To capture a country's employment regulation, the OECD's Employment Protection Legislation index (OECD, 2021) for the year 2017 was taken. The index evaluates countries' regulations on the dismissal of workers on regular contracts and the hiring of workers on temporary contracts, and covers both individual and collective dismissals (OECD, 2021). While this is a detailed and relatively comprehensive indicator, it has also received criticism on a number of grounds (Crouch et al., 1999; Addison and Teixeira, 2003). To combat the general indicator's shortcomings, the data was reweighted following the strategy of Emmenegger (2011) (see Supplementary material).

Freeman says that “Hardly anything can be more important for the eventual status of immigrants than the legal circumstances of their first entry” (Freeman, 2004, p. 950). To capture and compare countries' immigration policies, the Immigration Policies in Comparison (IMPIC) database was used. IMPIC measures policy outputs of 33 OECD countries from 1980 until 2010 covering the regulation of labor immigration, family reunification, refugee and asylum policy, and policy targeting co-ethnics (Helbling et al., 2017). IMPIC defines and measures immigration policies as governments' statements of what it intends to do or not to do (including laws, policies, decisions or orders) in regards to the selection, admission, settlement and deportation of foreign citizens residing in the country. It is specifically designed to allow cross-national comparisons of countries' immigration policies. Based on the analytical approach of Helbling et al. (2020), itself stemming from the finding of Schmid and Helbling (2016), namely that the three policy fields of labor migration, family reunification and asylum can be reduced to a single and consistent empirical dimension, this one comprehensive IMPIC measure covering these three policy fields as a measure of a country's immigration policy was used. The data is from 2010, the most recent year available.

The size of a country's low-wage/low-skill employment sectors is one of the principle demand-side explanations for labor migration (Devitt, 2011). The type of jobs that are available in a country and employers' needs to find people to fill these positions are part of the pull-factors and network effects that shape migration flows (Ruhs and Anderson, 2010; Devitt, 2011). Since the outcome of the QCA analysis is the extent to which migrants end up filtered into the low-end of the labor market, the relative size and prevalence of this sector is an important element. While this could be included in the models calculating countries' marginalization scores, the extent of the low-skill sector in a country is actively shaped by states' economic, industrial and other policy, and is an interesting factor in itself; and so was included as a causal condition. Given that the particular low-skill industries or sectors that are prevalent in European countries differ, including sectors defined in a more absolute or concrete sense (e.g., size of the hospitality, agriculture, manufacturing industry) in the QCA analysis is not possible for such a wide assortment of economies (Devitt, 2011; Cangiano, 2012; World Bank, 2020; Guzi et al., 2021). To capture the importance of low-skill employment and simultaneously allow for the fact that the particular low-skill sectors that prevail differ across countries, the percentage of low-skill jobs in each country was calculated using the EU-LFS (ISCO 5 and 9 jobs as percentage of total employment, following Andersson et al. (2019) and the (OECD, 2019b).

The outcome is migrant marginalization in the labor market: more specifically, the likelihood of a migrant working in the lowest job quartile compared to a national in a given country. First, jobs were categorized by converting respondents' occupations to the International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status (ISEI) scale: a continuous hierarchical scale empirically constructed using income, education and occupational data from men and women, where the scores can be conceived of as the cultural and economic resources typical of the incumbents of certain occupations (Ganzeboom, 2010). Based on the ISEI composition in each country, four job quartiles were created for each country and respondents assigned to one. Using quartiles in this aggregated manner is suitable for synthesizing large amounts of data, and improves comparability between countries (Fernández-Macías et al., 2012, p. 24). Ubalde and Alarcón (2020) also used the ISEI scale in a comparative study of attitudinal context and migrant disadvantage in the labor market.

With “working a bottom quartile job” as the dichotomous dependent variable, logistic regression models were then ran with migrant status as the key explanatory variable. To account for compositional effects of countries' migrant and nationals' characteristics, respondents' gender, age, and education [split into three levels according to International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED)] were included as control variables. As a robustness check and to investigate the role gender plays, the regressions were re-ran separately for men and women, the results of which are provided in the Supplementary material. The distribution of countries according to the extent of their migrant marginalization was largely similar in these gender-separated models to the distribution of the overall sample (with Greece being the most notable exception). What was striking was that the magnitude of marginalization was considerably higher across the board in the women-only sample. The odds ratios of working a bottom-quartile job for a migrant compared to a local were larger in every country in the women-only sample.

The conditions of employment protection legislation (ER), restrictive immigration policy (I), prominent low-skill sector (L), and the outcome (O) were calibrated using the direct calibration method (or transformational assignment, in the language of Thiem and Dusa, 2013), whereby base quantitative values are mapped into unit intervals with the help of logistic functions, with minimum information from the researcher (Ragin, 2000; Oana et al., 2021). Welfare state development (W) was calibrated using the qualitative method, with countries being assigned scores solely based on prior theory. The raw data, calibrated scores, truth table and discussion of the calibration are supplied in Supplementary material.

A two-step regression approach is used to investigate whether country-level factors—comparable to the “causal conditions” in the QCA—moderate the migrant-national difference in low-end employment. The focus is thus on cross-level interactions between the country-level variables and being a migrant or national from a given country. The two-step strategy is a natural one for investigating such interactions, performs well when the number of observations at the cluster-level is low, and has the advantage over alternative methods to mixed modeling that the effects of the individual level variables can vary freely across countries (Heisig et al., 2017).

The two-step approach features two sequential estimations: firstly country-specific logistic regressions are run with working a bottom-quartile ISEI job as the dependent variable, and with the binary variable of being a migrant or not as the primary independent variable (using the same operationalization of migrant as discussed in Sections 2 and 3.1), while also including age, gender and education as control variables in the adjusted models. The coefficient estimates for the migrant variable give an estimate of “migrant marginalization” for each country. This estimate is then used in the second step “slopes-as-outcomes” regressions. The independent variables in these models are the four country-level variables immigration policy, employment protection legislation, welfare state regime and extent of low skill employment. These are all based on the same data sources as outlined in Section 3.3 (and provided in the Supplementary material), but here are operationalized as independent variables rather than being calibrated into fuzzy sets. All four country-level variables have been z-standardized to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 at the country level. Feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) estimation is used to account for the fact that the dependent variable is not an observed value but an estimated one, and thus subject to sampling error (see Lewis and Linzer, 2005; Heisig et al., 2017; Heisig and Schaeffer, 2020)3.

The second step regression contains models with the single country-level variables, and also models including interaction terms to investigate the combined effects of institutional factors. The interaction terms included are restrictive immigration policy (I), interacting with each of the other variables: employment protection legislation (E), welfare state regime (W) and low-skill employment (L). This was the most theoretically interesting interaction and hypothesized to operate by itself but also in interaction with the three other contextual variables. Each model is run on both the adjusted and unadjusted marginalization scores.

The code for the analysis is available in the following github repository: https://github.com/SeanKGitHub/MigrantMarginalisation.

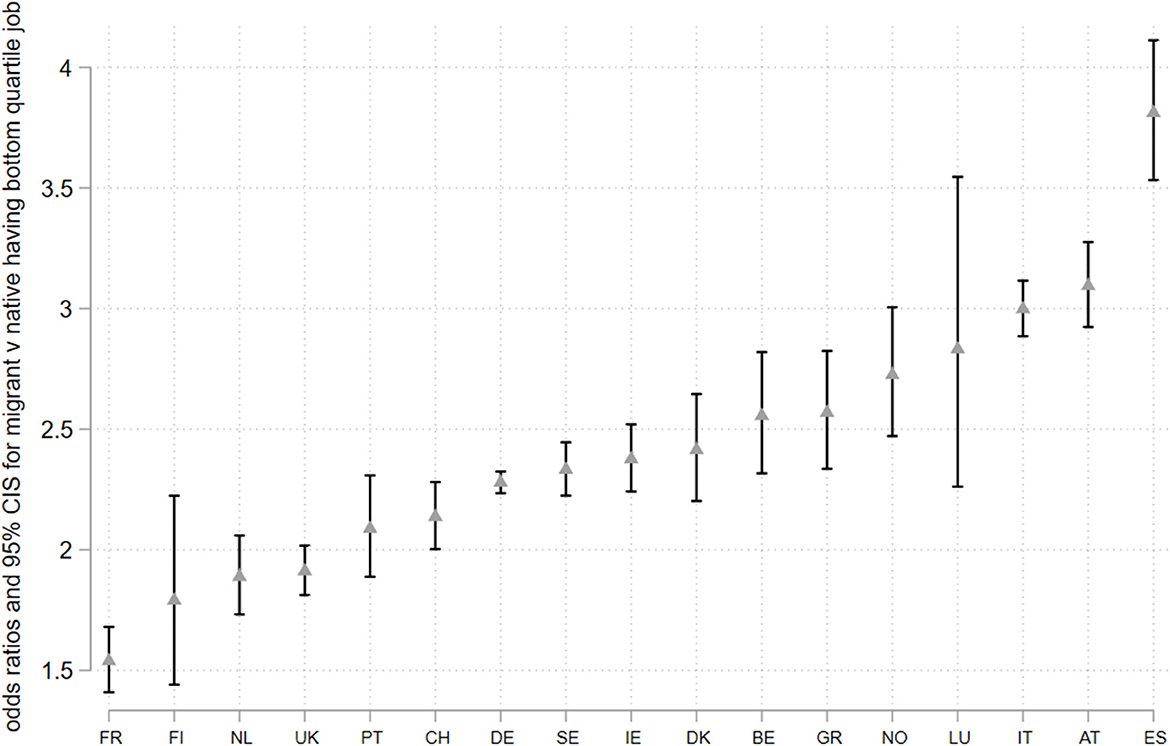

Figure 1 contains the odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals of a migrant to a local working a bottom quartile job, controlling for education, age and gender: These results then form the outcome in the next stage of analysis, the QCA. The first thing worth noting is that in all 17 countries there is a statistically significant difference between the odds of a migrant and a local working in the bottom quarter of the occupational distribution. From the graph we see that the gap between migrant and locals is largest in Spain, Austria and Italy, while the lowest differences are found in France, Finland and the Netherlands. Spain and Italy showing some of the highest scores for migrant marginalization and France's being considerably lower corroborates Fellini and Guetto's (2019) findings that non-Western migrants to the former two countries with highly segmented labor markets experience stronger occupational downgrading and lower upward mobility than in France. García-Serrano and Hernanz using a job quality index also found Italy and Spain to have the largest gaps between migrants and natives (2022).

Figure 1. Odd ratios of migrants working bottom quartile job compared to nationals, controlling for age, sex and education.

The analysis of necessity was first carried out to determine if any causal conditions were necessary for high migrant marginalization. No single conditions reached the recommended consistency threshold of 0.9 and so are not reported here. The same process was carried out separately for the negation of the outcome and again no single conditions were found to be necessary4. The potential necessity of combinations of conditions was also investigated. Given it is almost always possible to eventually find combinations that form supersets of an outcome (Oana et al., 2021), first it was attempted to identify combinations of causes that could represent a functional higher-order concept, but none were arrived at. QCA software was then used to check for possible combinations that would reach consistency of 0.9. Of the few that had consistency above 0.9, none had a relevance of necessity (RoN) that reached 0.5, and so were not further interpreted (Schneider and Wagemann, 2012; Oana et al., 2021). Results of the analysis of necessity are reported in Supplementary material.

For the analysis of sufficiency, first a truth table was constructed containing all possible combinations of causal conditions. Given there are four causal conditions, the truth table contains 24 = 16 rows of unique possible combinations5. Nine of these rows had conditions exhibited by at least one country case in the sample, while the other seven were logical remainders. For each individual row the QCA software then calculated its consistency score for the outcome using Boolean algebra. In the QCA literature a value of 0.75 or 0.8 has been established as a lower bound threshold consistency and here 0.8 was taken (Ragin, 2010; Schneider and Wagemann, 2012). This process can be summarized as calculating for each row that contains enough empirical evidence, whether or not the evidence is considered sufficient for the outcome (Oana et al., 2021). The full truth tables are found in Supplementary material. It has been argued by some that only the most parsimonious solution of a QCA can be interpreted causally (Baumgartner and Thiem, 2020), and so after first producing the conservative solution, specific logical remainders rows that produce the simplest summary of the empirical facts were allowed into the logical minimization of the truth table by the QCA software, to produce this most parsimonious solution. This however did not lead to any changes in the solution terms for the outcome of high migrant marginalization (but did for the analysis of sufficiency of the negation of the outcome, provided in Supplementary material). While the mechanisms involved in the negation of the outcome would require further theorizing outside the scope of this paper, this solution was an “Enhanced Standard Analysis,” whereby the simplifying assumptions included in the solution were checked for their tenability (Baumgartner and Thiem, 2020), and the solution was found to contain none of the three types of untenable assumptions—contradictory simplifying assumptions, assumptions contradicting claims of necessity, assumptions on impossible remainders (Oana et al., 2021).

Table 1 contains the most parsimonious solution of the logical minimization of the truth table for the existence of the outcome “High Migrant Marginalization.” We see that two causal pathways were identified as sufficient: the combination of employment protection, restrictive immigration policy and a prominent low-skill sector (ER*I*L), and the combination of restrictive immigration policy, a developed welfare state and prominent low-skill sector (I*W*L).

Figure 2 is the most parsimonious solution presented visually on an XY plot6. The strength of the solution's consistency is indicated by cases lying above or close to the diagonal, as we can see most do. We can further differentiate between the four quadrants. In the top right quadrant we have typical cases, where the country cases contain both the causal conditions found to be sufficient and the outcome: these can also be understood as cases explained by the solution formula (ES, IT, AT, DK, GR). The bottom left quadrant contains cases that exhibit neither the causal conditions in the solution nor the outcome, and are thus in line with the solution formula since the absence of the conditions don't lead to the outcome (UK, NL, FI, CH, FR, PT). The upper left quadrant contains deviant cases coverage: cases who do exhibit the outcome, but are not explained or covered by the solution formula (NO, IE, SE, BE, LU, DE). The bottom right quadrant of the plot is empty, indicating that there are no cases where they would have been the biggest challenges to claims of sufficiency if present: deviant case consistency in kind—exhibiting the conditions but not the outcome. A number of tests for robustness were performed to evaluate the sensitivity of the results to different methodological choices in the QCA process, as is recommended in the QCA literature (Schneider and Wagemann, 2012) and can be found in Supplementary material.

The first causal pathway to high migrant marginalization—the combination of a strong employment protection legislation, restrictive immigration policy and a prominent low-skill sector (ER*I*L)—covers the majority of explained cases: the southern group of Spain, Greece, and Italy, as well as Austria. The fact that Portugal is not included here in this cluster corroborates research by Ponzo (2021) where Portugal stood out as an exceptional case amongst this group of southern countries for having successful migrant integration. In this pathway there are many low-skill jobs to be done with relatively strong employment protection legislation regulating (at least parts of) the labor market, while restrictions on immigration and arrived immigrants are strong. Restrictive immigration policy can create limitations on migrants regarding their ability to change industry or employer, or even to leave their job at all (e.g., right to stay in the country is conditional on a single employer). Taking the presence of strong employment protection and high number of low-skills jobs alongside each other, we can imagine how it is likely to be in these low-skill jobs that employment protection is not fully enjoyed—via loopholes and exemptions from employment regulation which have become commonplace across Europe over the last number of decades of liberalization (Baccaro and Howell, 2011). To compound this, the migrant population affected by immigration policy may be more docile and fearful of speaking up to fight for regulation that exists on paper to be enforced in practice, or there can be explicit exemptions from employment regulation for immigrants. Echoing some of the dualization and job polarization literatures, we can imagine how a divide might develop between those jobs that enjoy strong employment protection regulation, and those low-skilled job positions that may not be as covered by employment protection legislation, and then tend to get filled by migrants.

The Southern European countries all have extensive agricultural/informal sectors featuring high migrant employment (Hazans, 2011; Natale et al., 2019; Nori and Farinella, 2020), much of whose extent of segmentation is not captured by official data due to its informal nature. The combination of employment protection and restrictive immigration might also directly influence the high levels of informal migrant work in these southern countries (Hassan and Schneider, 2016), in that employers and industries with low profit margins and limited legal access to migrant workers who are willing to work for less and in poorer conditions, are more likely to resort to informal and exploitative arrangements. While this isn't captured in official EU-LFS data, the actual existence of such high levels of informal work could contribute to the entrenchment of opinions and beliefs (e.g., “picking fruit is migrant work”) that would shape the patterns of segmentation detected in official data.

The second causal pathway for high migrant marginalization is restrictive immigration policy and prominent low-skill sector combined with a developed welfare state, observed in Denmark and Austria. A developed welfare state provides some capacity to refuse certain jobs and survive independently of pure market forces (Esping-Andersen, 1990), and it is likely that the high number of low-skill jobs that exist in these countries are those that people want to avoid. The restrictive immigration policy may prevent or disincentivise this same freedom to avert these jobs for migrants, as they may be formally limited in their access to the welfare state or freedom to change industry, or there could exist penalties when applying for prolonging their stay if they have had spells of receiving benefits. Eugster suggests a similar mechanism when interpreting her finding that there was no generosity-dependent reductive effect of social rights on immigrants' poverty: while possibly having formal access to social programs, migrants may not use them if welfare dependency jeopardizes their stay (Eugster, 2018). When recalling the notion of decommodification central to Esping-Andersen's welfare regime framework, we see here that the effective decommodification can be less for migrants when their ability to engage with and avail of the welfare state is limited via their status as immigrants (Esping-Andersen, 1990; McGovern, 2012).

“Just as reading a detailed map is not a substitute for taking a hike in the mountains,” ending the analysis with the abstract solution terms is incomplete without revisiting cases in light of them, and applying case knowledge (Ragin, 2000, p. 283). Here a brief country case study as an instance of each causal pathway is undertaken to further investigate and evaluate the plausibility of the solution terms of the formal QCA results, and to return the analysis from the abstract level to that of real cases7.

The Italian labor market is characterized by a low-skills equilibrium and low-wage regime, with firm size as another Italian idiosyncrasy (Devitt, 2018; Fellini et al., 2018). Devitt (2018) discusses how due to regulation changes from the 1970s, smaller firms became more competitive, with the typical firm now being a small family business relying on cheap low-skill labor. Firms employing migrants are smaller on average, and_flexible work contracts became more common from the 1990s, especially for migrants (Devitt, 2018). Resulting from the 2003 Biagi law, employers were given further means of eluding the state and providing less security to labor, such as “project collaborator” contracts which are often migrants working dangerous and tough jobs (Devitt, 2018). Overall there is heterogeneity in employment regulation and a weak employment compliance system—Devitt identifying at least four sectors: heavy regulated primary sector; moderately regulated secondary sector of small firms; the informal and gray economies (Devitt, 2018).

The segregation of migrants into the low-end of the labor market is known to be dramatic in Italy and has remained consistent over time despite the fact that the composition of migrants has changed (Fellini et al., 2018; Panichella et al., 2021). For non-western migrants, returns on education are low and only differs slightly by area of origin (Fellini et al., 2018). This is not just relevant for a migrant's first job in Italy, but occupational mobility afterwards is also low and so migrants get trapped in low-end jobs (Fellini et al., 2018). Panichella et al. (2021) found that migrants are penalized and trapped in the working class, and that the ethnic penalty is not fully explained by education and social origin. By 2007, 73% of migrant workers were registered as manual workers, with men mainly being found in industry and construction, women in domestic work (Ministero, dell'Interno, 2007, quoted in Devitt, 2018). Migrants tend to be overqualified and employed in low-wage positions at a higher proportion while having a higher employment rate than locals, as well as often experiencing shoddy working conditions, temporary contracts, and fewer employment rights (Bonifazi et al., 2020).

Bonifazi et al. (2020) suggest that immigration policy plays a role in these outcomes as migrants are required to have a working position to renew their permit to stay, and so may feel obliged to accept low-wage and low-skill work (of which there is plenty). This is a pressure that Italians don't have to deal with and so it makes sense that it would lead to differentials in outcomes.

Devitt (2018) highlights the significant role played by labor market institutions (particularly employment regulation and standards compliance, and labor market policies) in the growth in demand for migrant labor between the 1970s and 2007. She argues that this occurred via the generation of a large number of low-standards jobs, and by producing obstacles and disincentives to labor market participation of domestic labor (Devitt, 2018).

Fellini and Guetto (2019) highlight looser regulation for smaller firms in Italy as fostering strong labor market segmentation, and for all Southern countries, the prevalence of informal and irregular economies that migrants often work in. They discuss how in Southern countries there tends to be easy access to employment for migrants, but a substantial ethnic penalty regarding the type of jobs they will work. In contrast to less segmented or dualized labor markets, they say how in the Southern countries it can be difficult to escape low-status and -pay “immigrant jobs,” and that migrants' upward mobility is more likely to remain only within the secondary job market. After comparing labor market trajectories from different migrant groups, Fellini and Guetto also say that “historically rooted economic, political, and cultural relations between the sending and the destination countries defining the social standing of different national groups may be more important than skills transferability” (Fellini and Guetto, 2019, p. 52).

Fellini (2018) points to the segmented nature of the Italian (and Spanish) labor market and migration regulation that's used ex-post management of inward migration via regularization drives, as strengthening labor market segmentation and ethnic divide. She also concludes that the Southern “low unemployment risk—no access to skilled jobs” tendency in Italy has been reinforced since the 2008 financial crisis, with migrants even more negatively impacted and segregated into low-end jobs.

The extent of decommodification and non-reliance on markets to live —including the ability to say no to a given job—is central to understanding the efficacy of the welfare state (Esping-Andersen, 1990). In the Danish case this decommodification for migrant groups has been altered [often driven by ethnic or racial rhetoric (Fernandes, 2013)], resulting in differentiated capacity to engage with the labor market than Danes', on top of pronounced risks of ethnification on the labor market (Fernandes, 2013).

According to classic welfare state theory, Denmark as an instance of the social democratic regime is characterized by universal access, generous benefits, high degree of public involvement and levels of redistribution (Esping-Andersen, 1990). Of course this depiction is not static, and the Danish welfare state has undergone changes over the years including lowering taxes and increasing user-contributions and eligibility requirements (Møller, 2013; Trenz and Grasso, 2018). Denmark's immigration and integration regimes have been referred to as draconian in comparison to their Scandinavian neighbors' (Brochmann and Hagelund, 2011, p. 13). Møller (2013) points out that some benefit reforms related to labor market social risks—mostly reductions in amounts and durations, and restrictions in access—explicitly targeted immigrants. The most dramatic changes were special programs for newly-arrived immigrants and refugees: the “start-aid” scheme where they would receive ~35% less in social assistance than the general population, and the 2006 reforms de facto targeting immigrants and refugees that increased work demand for social assistance eligibility (Møller, 2013, p. 249). Andersen et al. (2019) found these reforms to have negative outcomes on various dimensions, including loss in disposable income, increase in (largely subsistence) crime, female labor force dropout, and education and language effects for children.

Møller ties these reforms to the idea that devolution via increased liberal “governance at a distance” can expose vulnerable social groups, including immigrants and refugees, to increased social risks, prejudice or discrimination (Møller, 2013, p. 258). Brochmann and Hagelund (2011) point out that Denmark has implemented policies that in practice target migrants, and in so doing have reformed general social policies. This is contrasted with the lack of measures taken to improve employment prospects of minority ethnic youth, in comparison with Sweden and Norway (Niknami et al., 2019, p. 8). Of the introductory labor market schemes brought in by Nordic countries, Denmark is the only to explicitly state as an aim that new immigrants must conform to an understanding of “Danish values” and norms (that they presumably do not have), and has policy with the most pronounced punitive and ethnified elements (Fernandes, 2013). While Sweden and Norway seem to be using the carrot and the stick, Denmark relies solely on sticks, with the problem and justifications for such policies being placed on the immigrants' themselves, their culture and religion (Fernandes, 2013, p. 212).

Suárez-Krabbe and Lindberg (2019) argue that as well as border, deportation and detention regimes—perhaps more obvious or “classic” sites when one thinks of the enforcement and reproducing of racialized logics and hierarchies (Richmond and Valtonen, 1994; Goldberg, 2011; Bowling and Westenra, 2018)—other areas of Danish policy and the welfare state like access to healthcare, housing, education and political participation, are increasingly organized on racial lines, resulting in racialized non-Western migrants being exposed to forms of structural racism from the Danish state. They say this hierarchization of immigrants on racial and colonial patterns produces group-differentiated racialized outcomes (Suárez-Krabbe and Lindberg, 2019, p. 91).

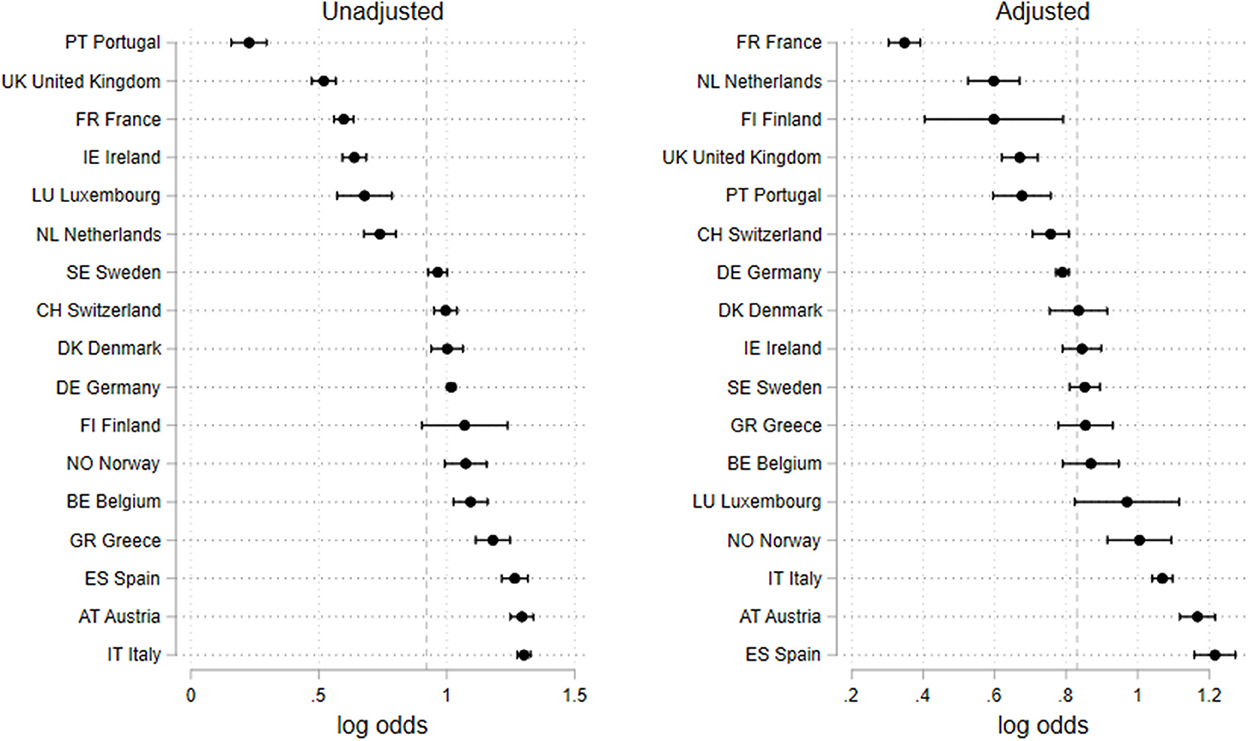

Figure 3 displays the migrant marginalization scores for all 17 countries, both when using just migrant status as a predictor and when in including the control variables education, gender and age. In all countries and in both models, migrants are more likely than nationals to work a bottom quartile ISEI job8. Italy, Austria and Spain have the highest marginalization scores in both models, while France, the UK and Portugal are all within the bottom five in both variants. These logistic regressions constitute the first step of the two-step strategy, and the estimates shown here are used as the dependent variable in the following second step regression models.

Figure 3. Migrant marginalization across 17 countries. Migrant vs. national working bottom quartile ISEI job. Source: EU-LFS. Results from country specific logistics regression. Adjusted scores control for education, age, and gender.

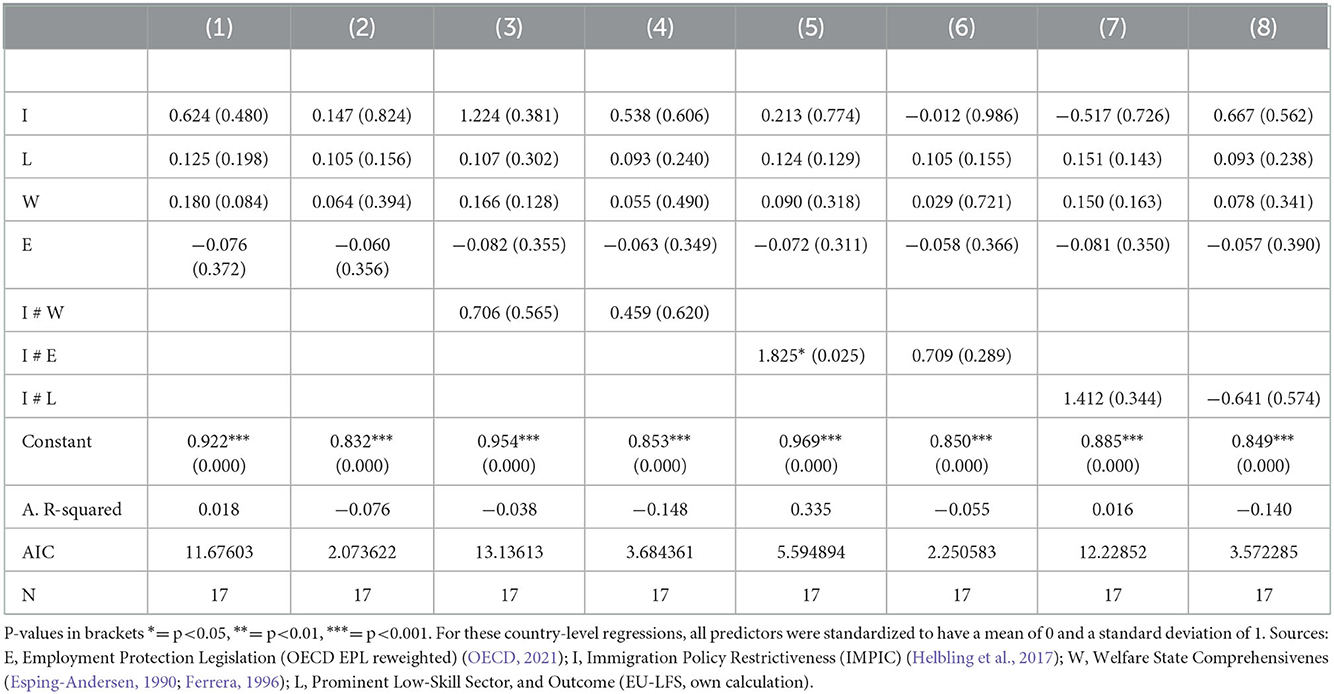

Now to inspect how country-level factors shape these marginalization scores, the results of the country-level feasible generalized least squares regressions are presented in Table 2. Columns 1, 3, 5 and 7 are all based on first step regressions without any control variables included (left column of Figure 3), while models 2,4,6 and 8 all include individuals' age, gender and education (right column Figure 3). In accordance with Figure 3, all the constant terms here are positive, implying that overall, migrants are more often in a bottom quartile job than nationals. The predictors in all models are z-standardized and so the constant term here represents the predicted marginalization score for a country with average scores on the country-level variables.

Table 2. Country-level regression (feasible generalized least squares) of migrant marginalization on institutional factors.

Looking at models 1 and 2, we see that the coefficient for restrictive immigration policy is positive, which is in the same direction as what was hypothesized: that the extent of migrant marginalization is higher where immigration policy is more restrictive. The coefficient is sizeably reduced from 0.624 to 0.147 when the model is adjusted for compositional factors at the individual level, but in both models the effect size is far from reaching statistical significance. Higher amounts of low skill employment (L) and a more comprehensive welfare state (W) follow the same pattern, correlating positively with more migrant marginalization, and with the coefficient reducing once compositional effects are included in the model. Stronger employment protection legislation (E) is the only country-level variable with a (slightly) negative coefficient. The coefficient for immigration policy is the largest of the country-level variable. As can be seen from the p-values however, none of the coefficients in either model reach statistical significance.

Moving to the models 3–8 that feature interaction terms, we first see that when restrictive immigration policy is combined with a more comprehensive welfare state, migrant marginalization is higher, as indicated by the positive coefficients in models 3 and 4, however again these are far from reaching statistical significance. In the models that interacts restrictive immigration policy and employment protection legislation however, the results are stronger. This combination is associated with higher migrant marginalization, and in the unadjusted model (5), reaches statistical significance at the 5% level. Once compositional variables are adjusted for, the coefficient drops from 1.825 to 0.709, and falls out of the statistically significant threshold, however the result is still noteworthy. The final combination of country-level factors investigated were immigration policy restrictiveness interacting with the extent of the low skill sector. Here in the unadjusted model 7, the direction of the effect is positive, implying the combination entails higher migrant marginalization, but in the adjusted model (8) the net effect of the combination is close to zero, with the interaction coefficient in neither model reaching statistical significance.

Across Europe, migrants from poorer countries continue to play a key role in the economies of their destination countries and are more likely everywhere to work a low-end job than locals, even when accounting for important individual characteristics. The extent to which migrants are allocated to lower status work differs across countries, and this paper has attempted shed light on what shapes these cross-national differences. The QCA analysis revealed two combinations of institutional factors as leading to this high migrant marginalization: restrictive immigration policy, a prominent low-skill sector combined with strong employment protection legislation; and restrictive immigration policy, prominent low-skill sector combined with a developed welfare state.

Both pathways contain a common base featuring policy that places restrictions upon migrants, and a large number of low-skill jobs to be done. When this base pairing is combined with what are designed to be protective institutions—the welfare state and employment regulation—high migrant marginalization occurs. With restrictive migration policy and individuals being strongly differentiated based on national origin, a kind of two-lane system develops, with migrants not benefitting from protective institutions as much as nationals, and being then filtered into the large pool of low-skill positions that need filling. This is in line with Eugster (2018) finding that more regulated wage bargaining coordination, minimum wage policies and generous traditional family benefits have a greater poverty-alleviating effect in countries with inclusive social rights for immigrants.

When it comes to the welfare state, if pressures exist that dissuade migrants from benefitting from the welfare state (e.g., consequences for residency, lower benefits for migrants), their effective decommodification is lower than locals', and thus freedom to operate on the labor market also. When we consider employment regulation in the twenty-first century, we must recognize that over time employer discretion has increased in different contexts in a variety of ways, and that circumvention and heterogeneity of regulation has become more commonplace (Baccaro and Howell, 2011). When there are a lot of low skill jobs, which are likely to be those where labor market regulations are more avoidable, migrants with extra pressures to be employed are more likely to take these jobs. When institutions contribute to fostering such dynamics, they can become ingrained socially, with certain jobs or industries becoming known as “migrant jobs” further deepening divides and marginalization.

In line with the work of Hooijer and Picot (2015) on poverty, these findings run counter to the idea that a single institutional element, like having a strong welfare state (e.g., Sainsbury, 2012), is enough to minimize disadvantage for migrants vis-à-vis nationals. We must be aware of how even protective and decommodifying institutions can foster marginalization if other policy domains are simultaneously in place and interact with them in certain ways—migrants position in the workforce is shaped by a multitude of forces.

The second methodological approach utilized in the paper, using two-step regression modeling, furthered the empirical base of our understanding how institutions impact migrant marginalization, and found evidence that, while somewhat suggestive, broadly aligned with the findings of the QCA. While many effects in the models failed to meet statistical significance levels, the effect of restrictive immigration policy, both by itself but also when interacted with a more comprehensive welfare state or stricter employment protection legislation, pointed in the direction of increasing migrant marginalization.

While the QCA identified causal pathways that operate in specific groups of cases, the regression analysis complemented this by looking at the overall effects of these country-level variables across all cases. Attempting to theoretically deduce how all relevant institutional factors could possibly interact and produce an effect of migrant marginalization is unreasonably ambitious, but the main hypothesis put forward, namely that more restrictive immigration policy by itself but also via interaction with other contextual elements increases migrant marginalization, is in alignment with the results of the regression models.

A limitation of this study due to its comparative nature was having to use a broad measure of “low-end work,” rather than more precise operationalizations that capture interesting dynamics of precarious migrant labor markets operating in different national contexts. The economic sectors where migrants tend to be concentrated is relevant to the topic, as are regional differences within countries, but in this design a quartile approach that equalized the concrete sectors was needed to allow comparability. While there are quality case studies on migrant workers in different industries within national contexts (e.g., Ruhs and Anderson, 2010), future research could use comparative designs to further understand how these rates differ within concrete sectors or regions across countries, and what is behind it. The study is also limited by having a focus on institutional-level explanations, and important factors that exist on the individual, interpersonal and discursive levels are not included in the analysis.