95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 30 August 2022

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.943120

This article is part of the Research Topic The Politics of the Commercial Determinants of Health View all 11 articles

After a public consultation in 2018, Singapore implemented standardized tobacco packaging as part of its portfolio of tobacco control policies in 2020, in compliance with Article 11 guidelines for implementing the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. This study analyzed policy actors in opposition to standardized packaging in Singapore and their submissions to the public consultation. Policy actors were profiled, and their arguments were then coded and compared across submissions. Descriptive results were then summarized in a narrative synthesis. In total, 79 submissions were considered for final analysis that opposed plain packaging in Singapore. Thematic analysis shows that transnational tobacco companies and their subsidiaries in Singapore, along with a variety of policy actors opposed to the standardized packaging policy, have significant similarities in arguments, often with identical statements. Industry tactics included framing tobacco as a trade and investment issue; utilizing trade barriers, intellectual property, and investment rights; pursuing litigation or threat of litigation; mobilizing third-party support and citing policy failure. This study provides evidence that further contributes to the growing literature on commercial determinants of health particularly industry tactics and, in this case, where the tobacco industry and its local and global allies, utilize to counter evidence-based tobacco control measures.

The World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Guidelines for implementation of Article 11 encourages parties to the FCTC to consider standardized packaging by eliminating the effect of advertising or promotion on the packaging (WHO FCTC Conference of Parties, 2008). After Australia's success in defending its 2012 plain packaging law that was legally challenged by the tobacco industry, several countries followed suit, including France and the United Kingdom in 2017; New Zealand, Norway, and Ireland in 2018; Turkey and Thailand in 2019 and Singapore in 2020.

Singapore proposed to implement standardized tobacco packaging and launched a public consultation on the proposed measure in 2018 (Ministry of Health Singapore, 2018b). In February 2019, the Singapore Parliament passed the amendments to the Tobacco Act with the enabling regulations for standardized packaging to take effect after 1 year. On 1 July 2020, the Tobacco (Control of Advertisements and Sale) (Appearance, Packaging, and Labeling) Regulations 2019 was implemented after a 12-month transition since the standardized packaging regulations were announced in July 2019. The policy process leading to the announcement of the policy in July 2019 and enforcement in July 2020 is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. Buttressed by a public health goal to move toward a tobacco-free society, Singapore implemented strict tobacco control policies that have been lauded globally, from its high tobacco taxes, smoke-free environment measures, comprehensive ban on tobacco advertising, promotion, sponsorship, and display to its progressive raising of minimum legal age to 21 (Amul and Pang, 2018a). Singapore has already made substantive progress in reducing smoking prevalence from 18.3% in 1992 to 12% in 2017, the lowest in Southeast Asia (Amul and Pang, 2018b). The last decade, however, has shown stagnation in smoking rates, hovering between 12 and 14% (Amul and Pang, 2018a).

The tobacco industry has opposed plain packaging based on the key argument that it will increase the illicit tobacco trade (Lie et al., 2018; Crosbie et al., 2019; Gallagher et al., 2019). However, research evidence does not substantiate this argument (Joossens, 2012; Evans-Reeves et al., 2015; Scollo et al., 2015b; Haighton et al., 2017). Additionally, post-implementation studies in countries that have implemented plain packaging have shown that it has contributed to the reduction of smoking prevalence and facilitated the easier identification of illicit cigarettes from other countries (Brennan et al., 2015; Durkin et al., 2015; Scollo et al., 2015a; Wakefield et al., 2015). Moreover, analysis of the framing of the tobacco industry's public relations campaigns and public consultation submissions in various countries against plain packaging point to a strategic coordinated approach—with similarities in structure and content, lack of transparency, and quality of evidence—toward delaying the adoption of plain packaging (Hatchard et al., 2014; Evans-Reeves et al., 2015; Lie et al., 2018; MacKenzie et al., 2018). This analysis of policy actors' submissions to the public consultation on plain packaging in Singapore aims to contribute to this literature.

To examine the potential challenges from the tobacco industry to Singapore's implementation of standardized tobacco packaging in 2020, the study involves a systematic content analysis of documents submitted by policy actors to the 2018 public consultation process that Singapore's Ministry of Health conducted on its proposed plain packaging measures. It aims to answer the question: what strategies did the tobacco industry use to influence the policy on plain packaging in Singapore? The study contributes to strengthening the evidence base not only on industry framing of plain packaging and illicit tobacco trade but also on industry interference in Southeast Asia, with a focus on the case of Singapore.

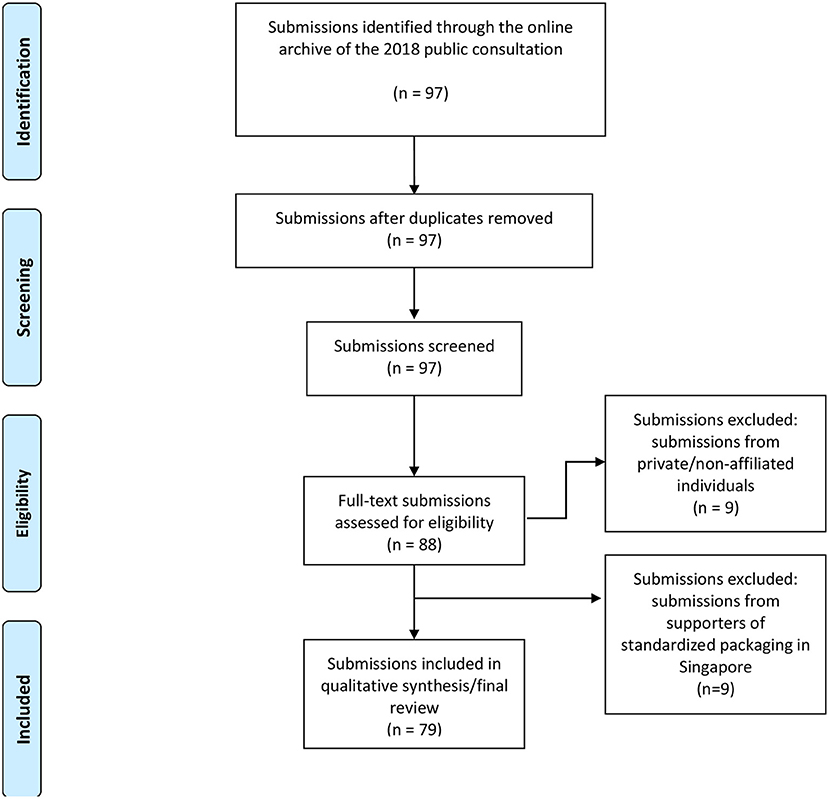

Submissions were reviewed according to a systematic screening process. Submissions were screened to only include submissions from policy actors (organizations and their representatives) and exclude submissions from private or non-affiliated individuals (see Figure 1). The submissions analyzed include only those that opposed plain packaging in Singapore. The policy actors were also grouped by their home country and classified by whether these countries have tobacco trade relations with Singapore. The policy actors were then mapped according to the type of entity: (1) whether it is a national or multilateral or civil society organization; and (2) whether it is tobacco industry-related or trade-related. This profiling of policy actors also included cross-checking with existing profiles of third-party lobby groups, astroturf groups, and front groups of the tobacco industry in the existing literature and on the University of Bath-Tobacco Control Research Group's TobaccoTactics.org website.

Figure 1. Selection criteria and study flowchart for qualitative analysis of stakeholder submissions.

Arguments and policy recommendations were coded (deductive and inductive) and compared across submissions. The arguments that form the basis of the policy actor's position, as interpreted by the researcher, were then compiled, and analyzed according to four sets of known discursive (argument-based) and instrumental (action-based) strategies according to the policy dystopia model that inherently assumes that proposed policies are doomed to fail. These strategies include: framing tobacco—a health issue—as a trade and investment issue; utilizing trade barriers, intellectual property, and investment rights; pursuing litigation (or threat of litigation); and mobilizing third-party support (Crosbie et al., 2019). Other arguments identified through the policy dystopia model but cannot be categorized in the above four sets of tobacco industry strategies were also included in the thematic analysis using an inductive approach (Ulucanlar et al., 2016; Matthes et al., 2021).

The policy dystopia model offers a comparative framework with which to understand elements of the political power of corporations to influence public health policies. For this study, the model helps primarily to identify corporations' discursive power through ideas, norms and arguments (e.g., framing tobacco as a trade and investment issue, and utilizing trade barriers, intellectual property and investment rights) that not only promote corporate interests (a narrative that proposed policies are undesirable by deeming them costly and by dismissing potential benefits) but also project that these interests are synonymous to the state's interests (Fuchs, 2007; Mikler, 2018; Matthes et al., 2021). Political communication, which includes corporations' submissions to public consultations on public health policies, lends to the increasing perception of corporations as legitimate political actors (Fuchs, 2007).

Additionally, the model also helps to identify corporations' instrumental power through lobbying strategies (e.g., the threat of litigation, and mobilizing third-party support) that support the construction and dissemination of its narratives to convince policymakers to proceed with policy action or inaction that favor corporations' interests (Fuchs, 2007; Matthes et al., 2021). Instrumental power primarily plays out in state-corporate relations which includes directed and strategic efforts to directly lobby and influence states (Mikler, 2018).

While the model emphasizes discursive and instrumental power, a missing element of the policy dystopia model is the structural power of corporations. Such power is exercised by corporations through capital mobility (movement of investments and employment opportunities) and more recently, through self-regulatory mechanisms and public-private partnerships (Fuchs, 2007).

While no intercoder reliability analysis was performed as the researcher is the only coder, the researcher compared the identified strategies with existing studies of tobacco industry strategies globally to ensure the validity of the results (Amul et al., 2021; Matthes et al., 2021). The researcher also benefited from feedback on the identified strategies from three subject matter experts on a working paper that this study is based on.

The descriptive results were then summarized in a narrative synthesis. All submissions included in this study are archived on the Singapore Ministry of Health's website and are publicly available (Ministry of Health Singapore, 2018a). Ethical approval was not necessary for the study which included only publicly available secondary data for analysis.

Singapore's Ministry of Health received 97 submissions in total from February to March 2018 and June 2018. Only seven policy actors responded to the second round of consultations in June 2018, six of which had original submissions to the first round of consultations from February to March 2018. In total, 82 unique policy actors responded to the public consultation process. After screening, 79 submissions were considered for final analysis (see Figure 1).

About 16 (22%) of the 73 policy actors that opposed the policy are based in Singapore, including three major transnational tobacco companies and their subsidiaries in Singapore, particularly Philip Morris International, British American Tobacco, and Japan Tobacco International (Japan Tobacco International, 2018) (see Supplementary Map). Singapore is the sixth top exporter of cigarettes globally (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2017a).

Fifty-nine policy actors opposed to standardized packaging are from 22 countries that Singapore has tobacco trade relations with (see Supplementary Table 1). About 14 policy actors that challenged standardized packaging were from the top 20 tobacco-producing countries, particularly the Philippines, the US, Indonesia, and Italy (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2018). Nineteen policy actors were from the top 20 tobacco-exporting countries, including the Philippines, the US, Indonesia, Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, and Bulgaria (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2017b). Seventeen policy actors were from the top 20 exporters (by quantity) of cigarettes globally, particularly Indonesia, the Netherlands, Russia, South Korea, Switzerland, Ukraine, and the US (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2017b). Consequently, all these countries have tobacco trade relations with Singapore (see Supplementary Table 1). The Dominican Republic, one of the four countries (along with Indonesia, Honduras, and Cuba) which disputed Australia's plain packaging to the WTO, was also represented in the public consultations. Belarus, despite having no tobacco trade relations with Singapore, had at least two policy actors that contributed to the public consultations.

The typology of tobacco industry-related and trade-related policy actors was further expanded to include various subtypes of policy actors that were involved in the public consultation process including (1) foreign government offices; (2) industry associations; (3) manufacturers' and exporters' associations; (4) retailers' associations; (5) intellectual property rights groups; (6) industry interest groups; (7) consumer interest groups; (8) academic institutions; (9) research organizations, and; (10) professional associations (see Table 1).

Of the 73 policy actors that opposed standardized packaging in Singapore (Table 1 and Supplementary Map), only eighteen policy actors have previously been profiled in TobaccoTactics.org as third-party lobby groups, astroturf groups, and front groups of the tobacco industry, most of which are either funded by the tobacco industry or have ties to transnational tobacco companies as their listed members (see Table 2).

Table 2. Policy actors profiled as third-party lobby groups, astroturf groups and front groups of the tobacco industry.

Applying the classification of tobacco industry strategies against plain packaging by Crosbie et al., thematic analysis shows that transnational tobacco companies and their subsidiaries in Singapore, along with a variety of policy actors that submitted their opposition to the standardized packaging policy, have significant similarities in arguments, often with identical statements across different submissions (Crosbie et al., 2019). These rubber-stamped submissions often bear the same references, with signatories as the only difference across several submissions. Figure 2 shows the breakdown of the number of policy actors citing identical arguments.

As a strategy to exercise discursive power, framing tobacco as a trade and investment issue is one of the most common arguments from the policy actors that opposed Singapore's standardized packaging proposals. The most prominent was that plain packaging will increase illicit trade, particularly smuggling contraband tobacco products, bootlegging, and the proliferation of counterfeit tobacco products. Illicit trade was cited by 64 policy actors, with about 88% of all policy actors against plain packaging. Figure 3 shows the various sectors and specific policy actors framing tobacco as an illicit trade issue.

These policy actors cited reports of counterfeit plain packs in the UK and France, the increase of confiscated counterfeit tobacco, and the increasing proportion of illicit tobacco in Australia. The International Trademark Association, for example, noted that:

“Standardized packaging will benefit the trade in counterfeit products. By making packaging simple and uniform, the currently complex techniques of packaging will be cheaper to produce, lowering the barriers of entry for criminals to enter this market, while at the same time increasing profit margins for these actors (de Acedo, 2018b).”

Moreover, the International Chamber of Commerce's Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy alludes to enforcement issues noting the burden on police and customs authorities in dealing with “a growing illicit market and other unintended consequences” and citing that the authorities will have difficulty in differentiating illicit products from legal and duty-paid products (International Chamber of Commerce Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting Piracy, 2018). Similarly, the UK's Institute of Economic Affairs noted how plain packaging made “branded cigarettes only available on the illicit market” and lowered costs for counterfeiters (Institute of Economic Affairs, 2018). The US Taxpayers Protection Alliance also cited the Oxford Economics and ITIC's reports on increasing illicit tobacco trade in Singapore, despite the methodological issues of the report that have been flagged by tobacco control scholars and despite other sources reporting a decrease in Singapore's illicit tobacco trade (Williams, 2018a). The US Taxpayers Protection Alliance as well as the INDICAM (Italy) cited the KPMG study about the increase of illicit tobacco in Australia, noting that the “absence of branding removes numerous protections in place to prevent counterfeiting and makes illicit products relatively less unattractive compared to legal products (Bergonzi, 2018; Williams, 2018a).” Additionally, Malaysia's Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs argued that plain packaging will lead to an increase in the consumption of illicit tobacco and “forces consumers to make uninformed decisions and forces them to enter the illicit black market in search of goods (Salman, 2018).” Furthermore, the International Advertising Association also claimed that Australia's plain packaging facilitated counterfeits and bootlegging without any decrease in smoking rates (Szulce, 2018). The Australasian Association of Convenience Stores grossly exaggerated how the market for illicit tobacco has “spiraled out of control” and “coincided directly with the increase in the regulation governing the sale of legal tobacco products (Spanish National Tobacco Retailers Association, 2018).” This was also cited by Amcor Specialty Cartons, noting how plain packaging can lead to “misinformation of customers by removing the ability of consumers to authenticate and differentiate between legitimate and illicit tobacco products (Czubak, 2018).”

Six policy actors linked illicit trade to tax evasion and the “tax gap” from the related losses in government revenue from excise and customs duties due to price competition and down trading (Heng, 2018a; International Chamber of Commerce Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting Piracy, 2018; Japan Tobacco, 2018; Japan Tobacco International, 2018; The Romanian Scientifically Association for Intellectual Property, 2018; van Schaik, 2018; Zimmerman and Michael, 2018). For example, the UK Tobacco Retailers Alliance noted how plain packaging will “exacerbate the tax gap,” which they estimated to be at GBP 3.1 billion in lost revenue (Khonat, 2018a). Moreover, the Taxpayers Protection Alliance (US) cited AUD 1.5 billion in lost revenue due to illicit tobacco trade in Australia that they attributed to plain packaging measures (Williams, 2018a). Five policy actors—including the International Trademark Association, Consumer Choice Center, France's Union des Fabricants (UNIFAB), and the Institute of Public Affairs further pointed out the economic costs of illicit trade mostly for governments and businesses (Davidson, 2018; de Acedo, 2018b; Roeder, 2018; Sarfati- Sobreira, 2018).

Eight policy actors—including Japan Tobacco, the European Chamber of Commerce in Singapore and the International Chamber of Commerce, and associations of licensed tobacco retailers in Singapore—linked illicit tobacco trade, purportedly fueled by plain packaging, with a growth in organized crime, including human trafficking, drug trafficking, money laundering, and terrorism financing (Hin et al., 2018; International Chamber of Commerce Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting Piracy, 2018; Japan Tobacco International, 2018; Khonat, 2018a,b; Roeder, 2018; Seah, 2018a,b; Zimmerman and Michael, 2018). For example, the Taxpayers Protection Alliance (US) specifically highlighted smuggling as an issue, citing the US State Department and US House of Representatives Homeland Security Committee Report on how illicit tobacco trade provides a source of financing for international terrorist networks, narcotics, and human trafficking (Williams, 2018a). At the local level, licensed tobacco retailers in Singapore also saw plain packaging as a “security threat” with the rise of gangs involved in smuggling cigarettes (Hin et al., 2018; Licensed Tobacco Retailers, 2018).

Moreover, six policy actors, particularly Japan Tobacco International and its parent company Japan Tobacco, the Japan Business Federation, the International Chamber of Commerce Switzerland and the International Chamber of Commerce Joint Task Force on Labeling and Packaging Measures, BelBrand, the Association of Dominican Cigar Manufacturers (PROCIGAR) also framed plain packaging around Singapore's investment potential, citing Singapore's reduced appeal for investment and innovation, which in turn “undermine a country's international reputation as a good place to do business (Gough, 2018; Hara, 2018; Japan Tobacco, 2018; Japan Tobacco International, 2018; Kelner, 2018; Pletscher, 2018; Taipov, 2018).” Citing reputational damage through alleged violations of investment rights is a known discursive strategy that has been used by the tobacco industry and its coalition of allies to block plain packaging measures in other countries (Crosbie et al., 2019). It also alludes to the structural power of corporations with reference to the “ease of doing business index” where the World Bank ranks states according to the context for conducting business and is now being reformulated as the “business enabling environment.”

Thirty-four policy actors – including consumer groups like Consumer Choice Center, Ukrainian Economic Freedoms Foundation, Forest EU and various retailer associations like the Australasian Association of Convenience Stores, Malaysia-Singapore Coffee Shop Proprietors General Association, Spanish National Tobacco Retailers Association, Asia Pacific Travel Retail Association, and European Travel Retail Confederation exerted that standardized packaging negatively affects consumer rights and encroaches upon economic freedom with the deprivation of consumer choice and consumer protection, and increased consumer risks with the increase in illicit trade (Barrett, 2018; Mong, 2018; Périgois, 2018; Roeder, 2018; Rogut, 2018; Spanish National Tobacco Retailers Association, 2018; Spinks, 2018; Zablotskyy, 2018).

However, such recommendations around strengthening measures to suppress illicit trade, while worthwhile in themselves, are not necessitated by vulnerabilities specifically created by adopting plain packaging measures, despite the claims by the tobacco industry and its coalition of third-party groups of allies.

Despite tobacco being a health issue, only five policy actors – including the Tobacco Institute of the Republic of China (Taiwan), Amcor Specialty Cartons, Australasian Association of Convenience Stores, Scottish Grocers' Federation, and Minimal Government Thinkers (Philippines) – opposed to standardized packaging cited health inequalities, health outcomes, and the health risks from illicit tobacco trade (Czubak, 2018; Lee, 2018; Oplas, 2018; Rogut, 2018; The Tobacco Institute of the Republic of China, 2018). The ASEAN Intellectual Property Association even cited the UK Department of Health's findings that “tobacco smuggling exacerbates health inequalities and discourages younger smokers from quitting because of the cheaper price (ASEAN Intellectual Property Association, 2018).”

Another discursive strategy that the tobacco industry has utilized is citing trade barriers, intellectual property rights, and investment rights in their arguments. Eleven policy actors – including members of the Philippine Congress, Indonesia's Directorate General of International Trade Negotiation, and various chambers of commerce, argued that plain packaging is a technical trade barrier that is “more restrictive than necessary,” “excessive,” “unreasonable” and will negatively impact exports of tobacco-producing countries (de Acedo, 2018a,b; Duran, 2018; Heng, 2018a,b,c; International Chamber of Commerce Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting Piracy, 2018; Moeftie, 2018; Pambagyo, 2018; Panganiban, 2018; Pletscher, 2018; Rodriguez et al., 2018; Sagala, 2018; Seah, 2018a,b). Seventeen policy actors – all international policy actors from Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, Russia, and Belarus – highlighted Singapore's status as a supporter of free trade and how plain packaging negates free trade principles (Andreu, 2018; Arranza, 2018; Campos, 2018; Cheng, 2018; Karas, 2018; Katchkatchisvili, 2018; Minsch and Herzog, 2018; Nam-Ki, 2018; Ors, 2018; Pambagyo, 2018; Panganiban, 2018; Pletscher, 2018; Rodriguez et al., 2018; Sagala, 2018; Spanish National Tobacco Retailers Association, 2018; The Tobacco Institute of the Republic of China, 2018).

More importantly, 48 policy actors – about 66 per cent of the policy actors opposed to the measure - also argued that plain packaging constitutes a violation of intellectual property rights, particularly of trademarks and brands, claiming plain packaging's inconsistency with international law and Singapore's domestic laws (de Acedo, 2018a,b; Gough, 2018; Japan Tobacco, 2018; Montanari and Thompson, 2018; Pambagyo, 2018; Seah, 2018a; Szulce, 2018). This is in contrast with the World Intellectual Property Rights Organization's response to British American Tobacco in 1994 that limiting trademarks under national law does not constitute a violation of the Paris Convention (Latham, 1994).

About fifteen policy actors from the tobacco industry, industry associations, intellectual property rights groups, foreign government agencies, and tobacco industry-related sectors (packaging) referred to the conflicts of plain packaging with Singapore's bilateral trade agreements and bilateral investment treaties, the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and the Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement (TBT). At least nine policy actors – only one of which is based in Singapore, the European Chamber of Commerce – referred to Singapore's domestic laws, including the Trademarks Act and Registered Designs Act (Seah, 2018a). Three policy actors from the Philippines and Indonesia referred to the issues that plain packaging would trigger for regional economic integration in ASEAN, regional frameworks like the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Intellectual Property Cooperation, and the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) (Pambagyo, 2018; Panganiban, 2018; Rodriguez et al., 2018).

The Property Rights Alliance (Montanari and Thompson, 2018) and Taxpayers Protection Alliance also cited Singapore's ranking in the Intellectual Property Rights Index (which is also published by Property Rights Alliance) where Singapore was ranked seventh in the world and second in the region (Williams, 2018a). Additionally, the International Chamber of Commerce and its various country offices argued how countries' standardized packaging regulations will lead to the tobacco industry's loss of “valuable” trademark rights that merit compensation to the industry (Cheng, 2018; International Chamber of Commerce Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting Piracy, 2018; Katchkatchisvili, 2018; Pletscher, 2018).

Furthermore, 13 policy actors including profiled tobacco industry front groups also utilized the “slippery slope” or “policy spillover” argument, particularly how plain tobacco packaging will impact not only health but also trade policies and serve as a precedent for other “unhealthy” consumer products and other industries including “alcohol, meat, sugar-sweetened food, sugary beverages, salty food, junk food, fatty food, cereals, infant formula, cosmetics, clothing, and toys (Andreu, 2018; Arranza, 2018; ASEAN Intellectual Property Association, 2018; Baba, 2018; Bergonzi, 2018; Campos, 2018; de Acedo, 2018a; Delaney, 2018; Ganev, 2018; Hara, 2018; Heng, 2018b,c; Humphrey, 2018; International Chamber of Commerce Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting Piracy, 2018; Katchkatchisvili, 2018; Meng, 2018; Minsch and Herzog, 2018; Montanari and Thompson, 2018; Nam-Ki, 2018; Oplas, 2018; Ors, 2018; Pambagyo, 2018; Páramo, 2018; Périgois, 2018; Pletscher, 2018; Popovichev, 2018; Roeder, 2018; Salman, 2018; Sano, 2018; Sarfati- Sobreira, 2018; Schauff, 2018; Seah, 2018a; Spanish National Tobacco Retailers Association, 2018; Szulce, 2018; Taipov, 2018; The Romanian Scientifically Association for Intellectual Property, 2018; Zablotskyy, 2018; Zimmerman and Michael, 2018).

The threat of litigation can be considered as both a discursive and instrumental strategy in this context. For plain packaging measures, the threat of litigation was looming as there was litigation against Australia's plain packaging measures at the time of the public consultation.

At least 11 policy actors, including known third-party lobby groups for the tobacco industry, alluded to litigation with reference to the recently settled appeal to the WTO Appellate Body on the dispute against Australia's plain packaging. According to these policy actors, the then-pending appeal in 2018 warrants that Singapore delays the implementation of plain packaging until the WTO Appellate Body releases its report, conducts a hearing and decides on the appeal (Andreu, 2018; Arranza, 2018; Campos, 2018; Duran, 2018; Katchkatchisvili, 2018; Nam-Ki, 2018; Ors, 2018; Popovichev, 2018; Spanish National Tobacco Retailers Association, 2018; The Romanian Scientifically Association for Intellectual Property, 2018; The Tobacco Institute of the Republic of China, 2018). Several of these policy actors are from the Dominican Republic which challenged Australia's plain packaging laws at the WTO.

An instrumental strategy, building a coalition of third-party supporters or allies was vital for building the volume of submissions that Singapore received in the public consultation process for standardized packaging. Table 1 shows the number and types of policy actors opposed to standardized packaging, some of which have disclosed their ties to the tobacco industry along the tobacco supply chain – from tobacco-producing countries, manufacturing and packaging sectors, exporters, designers, and advertisers, to retailers. These interest groups, which mobilized to lobby against standardized packaging policies in Singapore, constitute a wide network of actors acting to reinforce not only their sectoral interests but also the interests of the tobacco industry (see Table 1 and Figure 3). These third parties echoed the majority of the tobacco industry's discursive framing strategies.

Policy actors from tobacco-producing countries, including members of the legislature in the Philippines and government agencies in Indonesia– two of the top 20 tobacco-producing countries – cited standardized packaging's indirect impact on their tobacco farmers (Philippines) and those working in the supply chain industries for tobacco products (Pambagyo, 2018; Panganiban, 2018; Rodriguez et al., 2018; Sagala, 2018). The Dominican Republic's submission also centered on its dependence on the tobacco industry, particularly its tobacco farming and processing, and cigar manufacturing industry (Ors, 2018). Similarly, cigar manufacturers in the Dominican Republic highlighted that cigars are a luxury good and should be treated differently from cigarettes (Kelner, 2018). Notably, 10 policy actors, including manufacturers' associations and industry associations from Russia, Spain, the Philippines, Indonesia, an intellectual property rights group in South Korea, and the International Chamber of Commerce in Georgia submitted almost identical position papers with the primary argument that plain packaging does not work (Andreu, 2018; Arranza, 2018; Katchkatchisvili, 2018; Moeftie, 2018; Nam-Ki, 2018; Popovichev, 2018).

Thirty-five policy actors, including industry associations and retailer associations, highlighted how plain packaging will increase costs, risks, and burden to retailers, including the display, labor and training costs, tobacco sales leakage (for duty-free retailers), and security risks to retailers (Hirst, 2018; Khonat, 2018a; Lee, 2018; Licensed Tobacco Retailers, 2018; Meng, 2018; Páramo, 2018; Spanish National Tobacco Retailers Association, 2018). Duty-free retailers, travel retail associations and even Singapore's Changi Airport Group also voiced their opposition to standardized packaging by framing their argument from the narrative of retailers, particularly duty-free retailers and with specific reference to “tobacco sales leakage” to regional competitors (Changi Airport Group, 2018; Spinks, 2018).

Another major argument espoused by at least 45 policy actors against plain packaging is that it is essentially a policy failure in the countries where it has been implemented, citing post-implementation reviews, industry-commissioned reports, and industry-funded market research. A key assumption of the policy dystopia model, citing policy failure is included here as part of the tobacco industry's strategy and exercise of discursive power. According to these policy actors, these reports showed that there has been no decrease in smoking prevalence in Australia, France, and the UK after the implementation of plain packaging, despite evidence to the contrary. These policy actors –including transnational tobacco, various chambers of commerce, and business associations similarly highlighted that there is an increasing number of countries and industry associations rejecting plain packaging as a tobacco control measure (EU-Georgia Business Council, 2018; Gough, 2018; Heng, 2018b,c; Japan Tobacco, 2018; Japan Tobacco International, 2018; Karas, 2018; Katchkatchisvili, 2018; Minsch and Herzog, 2018; Moeftie, 2018; Schauff, 2018; Seah, 2018a).

Citing policy failure, fifteen policy actors proposed that Singapore should review its current tobacco control policies before considering the introduction of plain packaging and conduct a regulatory impact assessment of plain packaging. At least seventeen policy actors also proposed that instead of introducing plain packaging, Singapore should instead conduct public information/awareness campaigns and targeted education programs. Several policy actors recommended youth smoking prevention campaigns, including raising the minimum legal age, negative licensing schemes, imposing stiff penalties for sale to children (which are already being implemented in Singapore), and criminalizing “proxy” purchasing. Moreover, a number of these policy actors, including the tobacco industry, proposed that Singapore should consider implementing larger graphic health warnings only or allowing “minimum” trademarks but with larger graphic health warnings. Eight policy actors suggested that Singapore should delay consideration of plain packaging or delay implementation until the resolution of the trade dispute appeal against Australia at the World Trade Organization. Five policy actors, including British American Tobacco, the Taxpayers Protection Alliance, Australian Taxpayers Alliance, the Institute of Economic Affairs, and Forest EU proposed that Singapore should repeal its ban on electronic cigarettes and vapor products, and increase support for smoking cessation through harm reduction measures (Heng, 2018b,c; Institute of Economic Affairs, 2018; Marar and Andrews, 2018; Périgois, 2018; Williams, 2018a,b). At least five policy actors suggested the exemption of cigars, other non-cigarette tobacco products, and duty-free tobacco products from standardized packaging. Three policy actors, including the ASEAN Intellectual Property Association, the International Chamber of Commerce, and the Consumer Packaging Manufacturers Alliance encouraged Singapore to engage in stakeholder participation and collaboration in the formulation of plain packaging measures (Joossens, 2012; ASEAN Intellectual Property Association, 2018; International Chamber of Commerce Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting Piracy, 2018).

The findings in this study confirm and substantiate previous findings in the literature about the tobacco industry's discursive (framing or argument-based) and instrumental (action-based) strategies to counter plain packaging measures in public consultations globally (Evans-Reeves et al., 2015; Ulucanlar et al., 2016; Lie et al., 2018; MacKenzie et al., 2018; Crosbie et al., 2019; Hawkins et al., 2019). This study offers an additional case from Southeast Asia of how the tobacco industry and its network of associated interest groups – third-party lobby groups, astroturf groups, and front groups – are reusing similar frames of arguments to persuade countries to either delay the implementation of standardized packaging or to drop the policy entirely. This study corroborates previous findings that this network of policy actors supports the position of the tobacco industry by framing plain packaging through trade and investment, particularly illicit trade, intellectual property rights, international and domestic law, the threat of litigation, and the slippery slope argument that plain packaged tobacco will serve as the precedent for plain packaging of other unhealthy consumer products (Evans-Reeves et al., 2015; Lie et al., 2018; MacKenzie et al., 2018; Crosbie et al., 2019). It also contributes to the discourse on policy dystopia or “policy failure” metanarrative built by the tobacco industry to convince and persuade policymakers to adopt the industry's preferred policies over evidence-based public health measures (Ulucanlar et al., 2016). Contrary to the arguments posited by the policy failure metanarrative, there was no evidence of an increase in the use of illicit tobacco, or impact on retailers and small businesses in countries where standardized packaging was implemented (Wesselingh, 2018).

The resolution of the WTO dispute against Australia's plain packaging offers concrete evidence that the plain packaging of tobacco products is a pragmatic tobacco control measure and justifiable public health agenda. Even with Australia's victory against the appeal to the WTO resolution, this points to the challenge that countries like Singapore that are implementing plain packaging, and other countries considering the implementation of plain packaging, still need to prepare for possible interference (if not litigation) to delay, amend, or weaken plain packaging measures at the local, regional, bilateral, and multilateral levels. As the case of Australia shows, transnational tobacco corporations with their resources can profusely engage in “forum shopping,” which includes institutional trade and investment regimes such as the WTO Dispute Settlement System and Investor-State Dispute Settlement Mechanisms within bilateral investment treaties to challenge domestic policies (Eckhardt et al., 2016; Hawkins and Holden, 2016).

In the case of Singapore, the sheer number of policy actors that opposed and tried to influence the timeline of Singapore's standardized packaging proposal, compared to those supporting the policy, is stark. As noted above, this strategy of mobilizing third-party groups has already been documented in the literature on tobacco industry interference. The results of the policy process seem to show that the 1-year transition was a generous compromise given by the Singapore government to provide tobacco manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers time to prepare for the full implementation of the standardized packaging measure. This is relatively a long timeline since Singapore has been considering plain packaging measures since 2015 and included it in wider public consultations on potential tobacco control measures in 2016. Several of the policy actors involved in the 2018 public consultations even attached copies of their submissions to the 2016 public consultations, which formed the basis of their 2018 submission or simple reiterations of those submissions. However, it is encouraging for countries in the region that while Singapore received this barrage of submissions from the tobacco industry and its allies – albeit flawed and often identical – nonetheless proceeded to implement standardized packaging.

It is also interesting to note that the number and types of organizations that oppose tobacco control measures are becoming more diverse. The emergence of new policy actors trying to influence tobacco control policy outside of their sectors and geographic limits can also point to the alliance-building process that the tobacco industry continues to engage in, essentially building a coalition to support its strategies (Matthes et al., 2021). This lends support to the argument in the literature about the political power of corporations, such that the power of the global corporate sector – in this case, the tobacco industry and its network – rests on what Freudenberg termed the “corporate consumption complex” and was described by May as “the work of a complex and extensive network of agents all in their interests seeking to further and reinforce elements of the agendas that favor corporations” which includes financial institutions, trade associations, advertising, public relations firms, law firms, lobbying groups, think tanks and research organizations, astroturf citizen groups, and media platforms (May, 2015; Freudenberg, 2016). This points to the challenge of increased civil society-led monitoring of tobacco industry tactics, including their use of front groups and third parties, and other sectors to lobby against plain packaging measures not only on tobacco but also on other harmful consumer products, and against other evidence-based public health policies. The history of tobacco industry interference in the region has been widely documented (Amul et al., 2021).

A limitation of this study is the lack of access to previous public consultations on standardized tobacco packaging in Singapore. The results of the 2016 public consultations are not publicly available and could not be included in this study for analysis and comparison. While some of the policy actors – particularly transnational tobacco companies – participated in the 2016 public consultation and attached their previous submissions to their 2018 submissions, the author does not have access to the rest of the public consultation submissions from 2016. Due to limited space, this study did not include policy actors' submissions supporting standardized packaging in Singapore (see Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Note).

Identifying the strategies with which corporations, particularly that of the tobacco industry and its allies, exercise their instrumental and discursive power contributes to the increasing literature on the politics of commercial determinants of health. With the tobacco industry's history of political strategies in obstructing and interfering in public health and given that illicit trade remains an argument of the tobacco industry, Singapore needs to be vigilant and stringent in the enforcement of tobacco control measures, and more specifically to prevent and control the illicit tobacco trade in Singapore. This becomes more critical since the tobacco industry uses think tanks and research organizations to overestimate illicit tobacco trade, influence the debate over illicit tobacco trade, and undermine the WHO FCTC Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products with an industry-developed track and trace system (Evans-Reeves et al., 2015; Gilmore et al., 2015, 2019; Gallagher et al., 2019). The next possible step it can take is, to begin with, a comprehensive evaluation of Singapore's current policies to prevent illicit tobacco trade and consider accession to the WHO FCTC Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products. As of this writing, there are 65 parties to the Protocol. While none of the ASEAN member states has ratified the Protocol, Singapore can serve as a regional leader in reinforcing measures to control the illicit tobacco trade in the region.

Four critical challenges remain for Singapore in controlling the illicit tobacco trade. First, it needs to prepare for claims from the tobacco industry that standardized packaging is a policy failure and that it contributed to illicit trade. Second, Singapore should continue to cooperate and share information about the tobacco industry's tactics and its complex network of lobby groups, front groups, and astroturf groups. Third, Singapore needs to continuously monitor the size of illicit trade (beyond seizure statistics) and generate an independent estimate of the size of the problem. Last but not the least, Singapore needs to strictly enforce its current policies to control illicit tobacco trade, but at the same time gradually consider its accession to the WHO FCTC Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products.

On a global level, parties to the WHO FCTC that are implementing standardized tobacco packaging and other evidence-based tobacco control measures – including high-income and especially low- and middle-income countries – that are considering the implementation of plain packaging, still need to prepare for industry tactics to delay, amend, or weaken other tobacco control measures. Parties to the WHO FCTC should also consider acceding to the WHO FCTC Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products to contribute to global tobacco control efforts. Policymakers need to recognize tobacco industry tactics that can also be utilized by other health harmful industries (alcohol, sugary beverages) against other evidence-based public health policies.

Civil society organizations and public health advocates, especially those seeking corporate accountability, can utilize the results of this research to counter tobacco industry arguments against plain packaging measures, not only in low- and middle-income countries in the Southeast Asian region but also, globally. Researchers, investigative journalists, and civil society organizations alike can also support policymakers and the public in exposing, identifying, and monitoring policy actors from other health harmful industries (alcohol, sugary beverages) and raising public awareness of the tactics utilized by these industries to prevent effective evidence-based health policies from being proposed or implemented.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/proposed-tobacco-control-measures.

GA conceptualized and designed the study, compiled, analyzed the data, prepared, revised, finalized the manuscript, and is accountable for the content of this article.

GA carried out the research for this article with financial support from Cancer Research UK and Canada's International Development Research Centre (Grant No. 108822-001 for Advancing Tobacco Taxation in Southeast Asia: Addressing Evidence and Action). This work was produced under the Advancing Tobacco Taxation in Southeast Asia (ATT-SEA) Research Fellowship Program implemented by the School of Government, Ateneo de Manila University, Philippines.

The author would like to thank Dr. Ulysses Dorotheo, Prof. Hana Ross, and Prof. Nadia Doytch for reviewing earlier versions of the working paper on which this article is based. The author would also like to thank Ms. Ariza Francisco and Mr. Alen Santiago, former and current Program Managers for Tobacco Governance at the School of Government, Ateneo de Manila University respectively for their administrative support and assistance during the fellowship. The working paper was published under the Ateneo School of Government Working Paper Series. The author would also like to thank the reviewers who volunteered their time and expertise to review this manuscript and helped improve the quality of the manuscript.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Ateneo de Manila University, International Development Research Centre or its Board of Governors.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.943120/full#supplementary-material

Amul, G. G. H., and Pang, T. (2018a). Progress in tobacco control in Singapore: Lessons and challenges in the implementation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Asia Pacific Policy Stud. 5, 102–121. doi: 10.1002/app5.222

Amul, G. G. H., and Pang, T. (2018b). The state of tobacco control in ASEAN: Framing the implementation of the FCTC from a health systems perspective. Asia Pacific Policy Stud. 5, 47–64. doi: 10.1002/app5.218

Amul, G. G. H., Tan, G. P. P., and van der Eijk, Y. (2021). A systematic review of tobacco industry tactics in Southeast Asia: Lessons for other low- and middle-income regions. Intl. J. Health Policy Manage. 10, 324–337. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.97

Andreu, J. D. M. (2018). “ADELTA, Public consultation on standardized packaging and enlarged graphic health warnings for tobacco products, March 2, 2018,” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 1 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Arranza, J. L. (2018). “Federation of Philippine Industries, Inc., Response to the Ministry of Health's public consultation on the potential adoption of standardised packaging (March 5, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 2 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

ASEAN Intellectual Property Association (2018). “ASEAN Intellectual Property Association, Proposed amendments to the Tobacco Act to incorporate plain packaging measures,” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Baba, W. J. (2018). “Malaysian International Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Public Consultation on proposal to introduce standardized packaging of tobacco products in Singapore (March 16, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 7 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Barrett, M. (2018). “Asia Pacific Travel Retail Association (APTRA), Public Consultation on proposal to introduce standardized packaging of tobacco products in Singapore (March 16, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 6 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Bergonzi, C. (2018). “Istituto di Centromarca per la lotta alla contrafazzione (INDICAM), Response to the Ministry of Health's Public Consultation on the potential adoption of standardised packaging (March 14, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Bialous, S., and Corporate Accountability International (2015). Article 5.3 and International Tobacco Industry Interference, Report Commissioned by the Convention Secretariat. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

Brennan, E., Durkin, S., Coomber, K., Zacher, M., Scollo, M., and Wakefield, M. (2015). Are quitting-related cognitions and behaviours predicted by proximal responses to plain packaging with larger health warnings? Findings from a national cohort study with Australian adult smokers. Tobacco Cont. 24(Suppl 2):ii33. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052057

Campos, J. A. M. (2018). “ANDEMA, Response to the Ministry of Health's public consultation on the potential adoption of standardised packaging, March 8, 2018,” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 2 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Changi Airport Group (2018). “Changi Airport Groups' response to the public consultation on standardised packaging and enlarged graphic health warnings for tobacco products,” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submission to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 6 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Cheng, A. (2018). “International Chamber of Commerce Malaysia, Public Consultation on proposal to introduce standardised packaging of tobacco products in Singapore (March 16, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submission to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 5 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Crosbie, E., Eckford, R., and Bialous, S. (2019). Containing diffusion: the tobacco industry's multipronged trade strategy to block tobacco standardised packaging. Tob. Cont. 28:195. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054227

Czubak, J. (2018). “Amcor Specialty Cartons, Public Consultation to introduce standardized packaging of tobacco products in Singapore (March 13, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 3 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Davidson, S. (2018). “Submission to Singaporean plain packaging consultation (March 2018), Research Fellow at Institute of Public Affairs & Academic Felllow at the Australian Taxpayers' Alliance,” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

de Acedo, E. S. (2018a). “International Trademark Association (INTA) Submission to Public Consultation on Singapore Ministry of Health study on Standardised Packaging in relation to non-cigarette tobacco products (June 21, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 9 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

de Acedo, E. S. (2018b). “International Trademark Association (INTA) Submission to Public Consultation on Singapore Ministry of Health Study on Standardised Packaging in relation to non-cigarette tobacco products (March 15, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 3 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Delaney, E. (2018). “The Hibernia Forum, Response to the Ministry of Health's Public Consultation on the potential adoption of standardised packaging, March 6, 2018,” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 2 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Duran, L. F. (2018). “National Free Zones Council of the Dominican Republic, Public Consultation on proposal to introduce standardized packaging of tobacco products in Singapore (March 16, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 7 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Durkin, S., Brennan, E., Coomber, K., Zacher, M., Scollo, M., and Wakefield, M. (2015). Short-term changes in quitting-related cognitions and behaviours after the implementation of plain packaging with larger health warnings: findings from a national cohort study with Australian adult smokers. Tobacco Cont. 24(Suppl 2):ii26. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052058

Eckhardt, J., Fang, J., and Lee, K. (2017). The Taiwan Tobacco and Liquor Corporation: To join the ranks of global companies. Glob. Public Health 12, 335–350. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1273366

Eckhardt, J., Holden, C., and Callard, C. D. (2016). Tobacco control and the World Trade Organization: mapping member states' positions after the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Tob. Control 25:692. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052486

EU-Georgia Business Council (2018). “EU-Georgia Business Council Position Paper in response to the Public Consultation on proposed tobacco control measures (March 15, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 6 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Evans-Reeves, K. A., Hatchard, J. L., and Gilmore, A. B. (2015). ‘It will harm business and increase illicit trade’: an evaluation of the relevance, quality and transparency of evidence submitted by transnational tobacco companies to the UK consultation on standardised packaging 2012. Tob. Control 24:e168. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051930

Food and Agriculture Organization (2017a). Exports, Countries by Commodity, Tobacco Unmanufactured. FAOSTAT).

Food and Agriculture Organization (2018). Production, Countries by Commodity, Tobacco Unmanufactured. FAOSTAT.

Freudenberg, N. (2016). Lethal but Legal: Corporations, Consumption, and Protecting Public Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fuchs, D. (2007). Business Power in Global Governance. Boulder; London: Lynne Rienner Publishers. doi: 10.1515/9781685853716

Gallagher, A. W. A., Evans-Reeves, K. A., Hatchard, J. L., and Gilmore, A. B. (2019). Tobacco industry data on illicit tobacco trade: a systematic review of existing assessments. Tob. Control 28:334. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054295

Ganev, P. (2018). “Institute for Market Economics, Response to the Ministry of Health's Public Consultation on proposal to introduce standardised packaging of tobacco products in Singapore (March 15, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Gilmore, A. B., Fooks, G., Drope, J., Bialous, S. A., and Jackson, R. R. (2015). Exposing and addressing tobacco industry conduct in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 385, 1029–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60312-9

Gilmore, A. B., Gallagher, A. W. A., and Rowell, A. (2019). Tobacco industry's elaborate attempts to control a global track and trace system and fundamentally undermine the Illicit Trade Protocol. Tob. Control 28:127. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054191

Gough, J. (2018). “Japan Tobacco International, Response to Study on Standardised Packaging in relation to non-cigarette tobacco products (June 21, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 9 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Haighton, C., Taylor, C., and Rutter, A. (2017). Standardized packaging and illicit tobacco use: A systematic review. Tob. Prevent. Cessation 3, 13–13. doi: 10.18332/tpc/70277

Hara, I. (2018). “Keidanren (Japan Business Federation), Public Consultation on proposal to introduce standardized packaging of tobacco products in Singapore (March 13, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 3 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Hatchard, J. L., Fooks, G. J., Evans-Reeves, K. A., Ulucanlar, S., and Gilmore, A. B. (2014). A critical evaluation of the volume, relevance and quality of evidence submitted by the tobacco industry to oppose standardised packaging of tobacco products. BMJ Open 4:e003757. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003757

Hawkins, B., and Holden, C. (2016). A corporate veto on health policy? Global constitutionalism and investor-state dispute settlement. J. Health Polit. Policy Law 41, 969–995. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3632203

Hawkins, B., Holden, C., and Mackinder, S. (2019). A multi-level, multi-jurisdictional strategy: Transnational tobacco companies' attempts to obstruct tobacco packaging restrictions. Glob. Public Health 14, 570–583. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2018.1446997

Heng, L. (2018a). “GD Machinery South East Asia Pte Ltd, Public Consultation on Proposal to Introduce Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products in Singapore (March 9, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Heng, S. (2018b). “British American Tobacco Sales & Marketing Singapore, Public Consultation on Standardised Packaging and Enlarged Graphic Health Warnings for Tobacco Products (March 16, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 8A (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Heng, S. (2018c). “British American Tobacco Sales & Marketing Singapore, Re: Study on Standardised Packaging in relation to Non-Cigarette Tobacco Products (June 25, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 9 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Hin, H. P., Foo, L. K., Suaa, G. K., and Tay, A. (2018). “Foochow Coffee Restaurant & Bars Merchants Association, Kheng Keow Coffee Merchants Restaurant and Bar-Owners Association, Singapore Provision Shop Friendly Association, Singapore Mini Mart Association, Public Consultation on Standardized Packaging and Enlarged Graphic Health Warnings for Tobacco Products (March 16, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 6 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Hirst, J. (2018). “Singapore Retailers Association (SRA) feedback regarding the public consultation on proposal to introduce standardised packaging of tobacco products in Singapore (March 16, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submission to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 5 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Humphrey, C. (2018). “EU-ASEAN Business Council, Public Consultation on proposal to introduce standardised packaging of tobacco products in Singapore (March 16, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submission to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 5 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Institute of Economic Affairs (2018). “Response from Christopher Snowdon of the Institute of Economic Affairs to the Singapore government's consultation on standardized packaging (March 12, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 2 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

International Chamber of Commerce Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy (2018). “International Chamber of Commerce Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy- BASCAP response to the 2nd Consultation of the Standardised Packaging Proposal in Singapore (March 15, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submission to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 5 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Japan Tobacco (2018). “JT's Response to the Public Consultation on Proposed Tobacco Control Measures in Singapore (March 15, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Japan Tobacco International (2018). “Japan Tobacco International, Submission to the Public Consultation on Proposed Tobacco Control Measures in Singapore (March 15, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Karas, M. (2018). “Association of European Business (AEB) (Belarus), Public Consultation on Proposal to Introduce Standardized Packaging of Tobacco Products in Singapore (February 21, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 7 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Katchkatchisvili, Z. (2018). “International Chamber of Commerce Georgia, Response to the Ministry of Health's Public Consultation on the potential adoption of Standardised Packaging (March 13, 2018),” Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 3 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Kelner, H. (2018). “Association of Dominican Cigar Manufacturers (PROCIGAR), Public Consultation on proposal to introduce standardised packaging of tobacco products in Singapore (March 9, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Khonat, S. (2018a). “Response by the UK Tobacco Retailers' Alliance to Singapore's Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products Consultation (March 16, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 3 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Khonat, S. (2018b). “Tobacco Retailers' Alliance UK, Re: Study on Standardised Packaging in relation to Non-Cigarette Tobacco Products (June 25, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 9 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Latham, D. A. (1994). Letter to Jacqueline Smithson, enclosing the WIPO advice. Lovell White Durrant, Law Firm, in British American Tobacco Records.

Lee, J. (2018). “Scottish Grocers' Federation, Public Consultation on Proposed Tobacco Control Measures in Singapore: Plain Packaging in Sotland (March 15, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submission to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 5 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Licensed Tobacco Retailers (2018). “Licensed Tobacco Retailers (Singapore), Response to the Public Consultation on Standardised Packaging and Enlarged Graphic Health Warnings for Tobacco Products (March 13, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submission to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 5 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Lie, J. L. Y., Fooks, G., de Vries, N. K., Heijndijk, S. M., and Willemsen, M. C. (2018). Can't see the woods for the trees: exploring the range and connection of tobacco industry argumentation in the 2012 UK standardised packaging consultation. Tob. Control 27:448. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053707

MacKenzie, R., Mathers, A., Hawkins, B., Eckhardt, J., and Smith, J. (2018). The tobacco industry's challenges to standardised packaging: A comparative analysis of issue framing in public relations campaigns in four countries. Health Policy 122, 1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.08.001

Marar, S., and Andrews, T. (2018). “Joint Comments of Australian Taxpayers' Alliance (ATA) and MyChoice Australia (MC), Public Consultation on Standardised Packaging and Enlarged Graphic Health Warnings for Tobacco Products (February 15, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submission to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 5 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Matthes, B. K., Lauber, K., Zatonski, M., Robertson, L., and Gilmore, A. B. (2021). Developing more detailed taxonomies of tobacco industry political activity in low-income and middle-income countries: qualitative evidence from eight countries. BMJ Global Health 6:e004096. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004096

May, C. (2015). Global Corporations in Global Governance. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315880204

Meng, H. C. (2018). “Federation of Sundry Goods Merchants Associations of Malaysia, Public Consultation on proposal to introduce standardised packaging of tobacco products in Singapore (March 12, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 2 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Mikler, J. (2018). The Political Power of Global Corporations. Cambridge; Medford, MA: Polity Press.

Ministry of Health Singapore (2018a). Public Consultation on Proposed Tobacco Control Measures in Singapore.

Ministry of Health Singapore (2018b). Singapore to Introduce Standardized Packaging and Enlarged Graphic Health Warnings.

Minsch, R., and Herzog, E. (2018). “Economiesuisse Response to the Ministry of Health's Public Consultation on the potential adoption of standardised packaging (March 15, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submission to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 5 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Moeftie, M. (2018). “Gabungan Produsen Rokok Putih Indonesia (GAPRINDO), Public Consultation on Proposal to Introduce Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products in Singapore (March 14, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Mong, H. S. (2018). “Malaysia Singapore Coffee Shop Proprietors' General Association, Public Consultation on Proposal to Introduce Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products in Singapore, March 8, 2018,” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 2 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Montanari, L., and Thompson, P. (2018). “Property Rights Alliance Consultation Submission concerning the SP Proposal on Tobacco Control Measures (March 12, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submission to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 5 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Nam-Ki, C. (2018). “Trade-related IPR Protection Association (TIPA), Response to the Ministry of Health's Public Consultation on the potential adoption of Standardised Packaging (March 13, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 3 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Oplas, B. S. (2018). “Minimal Government Thinkers, Standardised Packaging Proposal for Tobacco Products in Singapore, March 8, 2018,” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 2 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Ors, M. (2018). “Camara Oficial de Comercio de España en República Dominicana, Response to the Ministry of Health's Public Consultation on the Potential adoption of Standardized Packaging (March 9, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 3 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Pambagyo, I. (2018). “Directorate General of International Trade Negotiation (Indonesia), Public Consultation on Standardized Packaging and Enlarged Graphic Health Warnings for Tobacco Products in Singapore (March 13, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 6 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Panganiban, J. J. T. (2018). “Jose T. Panganiban, Jr., Chair, Committee on Agriculture and Food, House of Representatives, Philippines (January 17, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 1 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Páramo, J. (2018). “Mesa del Tabaco, Public Consultation on Standardised Packaging and Enlarged Graphic Health Warnings for Tobacco Products (March 15, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Périgois, G. (2018). “Public Consultation on Standardised Packaging and Enlarged Graphic Health Warnings for Tobacco Products:Forest EU Response to the Public Consultation,” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Pletscher, T. (2018). “International Chamber of Commerce Switzerland, Response to the Ministry of Health's Public Consultation on the potential adoption of Standardised Packaging (March 14, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Popovichev, A. (2018). “Association Rusbrand, Response to the Ministry of Health's Public Consultation on the potential adoption of standardized packaging, March 1, 2018,” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 1 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Rodriguez, M. B., Bravo, A. M., de Vera, E. M., Salon, O. T., Chavez, C., Arcillas, A. B., et al. (2018). “Members of Philippine Congress (House of Representatives), Public Consultation on Proposal to Introduce Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products in Singapore (March 5, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Roeder, F. C. (2018). “Consumer Choice Center, Comment on Public Consultation Paper on Proposed Tobacco Control Measures in Singapore (June 21, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 9 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Rogut, J. (2018). “AACS Submission: Public Consultation on Standardised Packaging and Enlarged Graphic Health Warnings for Tobacco Products (March 9, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 2 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Sagala, K. (2018). “National Standardization Agency of Indonesia, Indonesia Comment Related to Proposed Tobacco Control Measures in Singapore (March 13, 2018)”, in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 3 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Salman, A. (2018). “Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs (IDEAS), Public Consultation on Proposal to Introduce Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products in Singapore (March 14, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 3 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Sano, H. (2018). “Japan Intellectual Property Association (JIPA) Opinion on Potential Standardised Packaging Policy in Singapore (March 8, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Sarfati- Sobreira, D. (2018). “Union des Fabricants (UNIFAB), Response to the Health Singapore “Consultation on 'Plain and Standardized Packaging' for Tobacco Products” (March 12, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 2 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Schauff, F. (2018). “Association of European Businesses, Response to the Ministry of Health's Public Consultation on the potential adoption of Standardised Packaging (March 15, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Scollo, M., Bayly, M., and Wakefield, M. (2015a). Availability of illicit tobacco in small retail outlets before and after the implementation of Australian plain packaging legislation. Tob. Control 24:e45. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051353

Scollo, M., Zacher, M., Coomber, K., and Wakefield, M. (2015b). Use of illicit tobacco following introduction of standardised packaging of tobacco products in Australia: Results from a national cross-sectional survey. Tob. Control 24(Suppl 2):ii76. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052072

Seah, E. (2018a). “European Chamber of Commerce, Singapore, Industry Feedback on the Public Consultation on Proposed Tobacco Control Measures (March 15, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Seah, E. (2018b). “European Chamber of Commerce, Singapore, Industry Feedback on the Public Consultation on Proposed Tobacco Control Measures/Industry Comments on the Study on Standardised Packaging in relation to non-cigarette tobacco products (June 20, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 9 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Spanish National Tobacco Retailers Association (2018). “Unión de Asociaciones de Estanqueros de España (Spanish National Tobacco Retailers Association), Response to the Ministry of Health's Public Consultation on the potential adoption of Standardised Packaging (March 9, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 2 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Spinks, K. (2018). “European Travel Retail Confederation, Public Consultation on Proposal to Introduce Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products in Singapore (March 16, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submission to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 5 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Szulce, D. (2018). “International Advertising Association, Public Consultation on Proposal to Introduce Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products in Singapore (March 5, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 4 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Taipov, A. (2018). “BelBrand Association for Intellectual Property Protection, Public Consultation on Proposal to Introduce Standardized Packaging of Tobacco Products in Singapore (February 21, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 7 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

The Romanian Scientifically Association for Intellectual Property (2018). “The Romanian Scientifically Association for Intellectual Property (ASDPI), View on the infringement of the intellectual property rights by the introduction of plain packaging of tobacco products (March 16, 2018),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 6 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

The Tobacco Institute of the Republic of China (2018). “The Tobacco Institute of the Republic of China, Standardised Packaging Proposal for Tobacco Products in Singapore, March 8, 2018 (Translated),” in: Result of the Public Consultations, Submissions to Feb-March 2018 Public Consultations, Batch 2 (Singapore: Ministry of Health Singapore).

Tobacco Control Research Group (2020a). Consumer Choice Center. University of Bath. Available online at: https://www.tobaccotactics.org/index.php?title=Consumer_Choice_Center

Tobacco Control Research Group (2020b). Consumer Packaging Manufacturers Alliance [Online]. University of Bath. Available online at: https://www.tobaccotactics.org/index.php?title=Consumer_Packaging_Manufacturers_Alliance

Tobacco Control Research Group (2020c). European Carton Makers Association [Online]. University of Bath. Available online at: https://www.tobaccotactics.org/index.php?title=European_Carton_Makers_Association