94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 04 August 2022

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.921252

This article is part of the Research TopicMind the Backlash: Gender Discrimination and Sexism in Contemporary SocietiesView all 11 articles

To explain women's underrepresentation in politics, supply-side factors receive much empirical support, emphasizing the low numbers of women on the ballot. Whether demand from voters also contributes to the problem is less clear, however, as both observational and experimental research shows that average voters are not less likely to vote for women candidates. We argue that voters actually do play a role, although not all voters to an equal extent. More precisely, we expect the gender bias in the electorate to be conditional upon partisanship and propose two mechanisms through which this materializes: political gender attitudes and/or gender stereotypes. Although the conditionality of voters' gender bias based upon partisanship is convincingly shown to exist in the US, much less is known about it in the European context, while its multi-party political systems lend themselves well for a more detailed differentiation between party families. We expect that right, and especially populist radical right, voters are biased in favor of men politicians, while left, and especially green left, voters are biased in favor of women politicians. We test our hypotheses with a large-scale vignette experiment (N = 13,489) in the Netherlands, and show that there is indeed a (slight) preference for women representatives among Green party voters, and a clear preference for men candidates among voters of populist radical right parties. Moderate left-wing or right-wing voters, however, show no gender bias. Thus, although right-wing populist parties have electoral incentives to be hesitant about promoting women politicians, most other parties face no electoral risk in putting forth women politicians.

Do voters contribute to the underrepresentation of women in political office? In explaining the low numbers of women in politics, existing work points to various factors: the gender gap in political ambition (Fox and Lawless, 2010), gendered party recruitment (Verge and Claveria, 2018), and gender-differentiated media coverage (Van der Pas and Aaldering, 2020). Voters, by contrast, are usually not seen as a main source of the gender imbalance in politics. Observational studies find a lack of impact of candidate gender on vote choice (e.g., Dolan, 2014; Hayes and Lawless, 2016; Bridgewater and Nagel, 2020), while experimental research shows that respondents are not more negative about women candidates and that they are also not less likely to vote for them (Schwarz and Coppock, 2022).

We argue that voters actually do play a role in women's underrepresentation, although not all voters to an equal extent. More specifically, we expect that voters of some specific parties prefer a man or a woman as representative. Put differently, the gender bias in the electorate is conditional upon partisanship. The conditionality of voters' gender bias based on partisanship is mainly been studied in the US, were it is shown that Republicans favor men politicians while Democrats prefer women candidates (e.g., Sanbonmatsu and Dolan, 2009; Schwarz and Coppock, 2022). However, very little is known about this in the European context, while the multi-party political system in most European countries lend themselves well for a more fine-grained examination of the role of partisanship. The main contribution of this paper is that we study this phenomenon in the multiparty context of the Netherlands, more finely distinguishing between different parties. Specifically, we expect that right and especially populist radical right voters are biased in favor of men politicians, while left and especially green left voters are biased in favor of women politicians.

We test our hypotheses with a vignette experiment (N = 13,489), which was integrated into two waves of the Dutch EenVandaag opinion panel. Prior to the experiment, we asked participants to answer questions measuring their attitudes toward women in politics. Three weeks later, we randomly assigned participants to the man or woman politician version of a newspaper-like introduction of a new member of Parliament, after which we gauged the evaluation of the politician. Because of the large sample size, we are able to distinguish the effect of politician gender among the electorates of five party families and twelve distinct parties.

The results provide cause for both concern and optimism when it comes to the prospect of gender parity in parliament. On the one hand, electorates of populist right parties are indeed biased against women representatives, making it very unappealing for these parties to increase their share of women in parliament. This is particularly detrimental, because these parties are major drivers of female underrepresentation in parliaments where they are present. On the other hand, most other parties, face either a bonus or no electoral repercussions from their voters from nominating women. Thus, particularly among the mainstream right, there is ample electoral opportunity for the improvement of equal gender representation.

Over 100 years after obtaining voting rights in most European and North American countries, women are still underrepresented in politics. In Europe, women make up just over 30% of country lower house members, in the US and Canada it is, respectively, 27.0 and 30.5%1. Party leaders in the post-war period have been overwhelmingly men (O'Brien, 2015), and the same holds for prime-ministers and cabinet members (O'Brien et al., 2015).

Explanations for women's underrepresentation can be divided into supply-side and demand-side focused (Karpowitz et al., 2017); see also Norris, 1996; Mügge and Runderkamp, 2019. On the supply-side are explanations for the low numbers of women candidates on the ballot. For instance, gendered socialization leads to different levels of political ambition among men and women (Fox and Lawless, 2011, 2014; Schneider et al., 2016), men and women respond differently to party recruitment (Preece et al., 2016), women are recruited less often (Sanbonmatsu, 2006; Lawless and Fox, 2010), and parties' electorates and candidate selection rules affect the gender balance of the candidate pool (Fortin-Rittberger and Rittberger, 2015).

Whether demand from voters also contributes to the problem is less clear. In fact, two types of evidence testify against a gender bias in the electorate. One is from observational data: The electoral outcomes of races in which women compete show that women win at equal rates as men (e.g., Sanbonmatsu, 2006). Similarly, election studies on large scale surveys indicate that the gender of a political candidate either hardly matters or has too little sway to override the overwhelming influence of partisanship (Dolan, 2014; Hayes and Lawless, 2016; Bridgewater and Nagel, 2020). However, this lack of gender bias might result from unobserved heterogeneity between men and women candidates, for instance, a higher quality of and/or effort paid by women than (Anzia and Berry, 2011; Lazarus and Steigerwalt, 2018; Bauer, 2020). Nevertheless, a second type of evidence, based on experimental studies, also finds no gender bias in voters' reactions to women politicians. In such studies, respondents see short profiles of candidates, in which the gender of the candidate is randomly assigned to man or woman, and they are asked for an evaluation or their vote intention. A recent meta-analysis of these type of experiments shows that, on average, respondents are not more negative about women candidates and that they are also not less likely to vote for them (Schwarz and Coppock, 2022).

Even though voters on average might not show a gender bias toward men or women political candidates, we argue that specific groups of voters might. Thus, we expect that voters do play a role in women's underrepresentation, although not all voters to an equal extent. We contend that voters of particular parties do prefer a man or a woman as their representative, or, put differently, that gender bias in the electorate is conditional upon the party preference of the voter. Our expectations, which we outline further below, are that left-party and particularly Green-party voters prefer women, while right-party and particularly populist right voters prefer men. As a result, right-wing and populist right parties actually face an electoral disincentive to increase the share of women among their candidates. In most legislatures, right-wing and particularly populist right parties are already the parties with the strongest male overrepresentation (e.g., Caul, 1999; O'Brien, 2018, p. 105; Sundström and Stockemer, 2021), which means that precisely those parties that are in the best position to improve women's representation, have no electoral incentive to do so.

This party-voter conditionality is not an entirely new argument: previous scholarship has shown a relation between voters' gender bias and partisanship in the context of the US. These studies show that Republican voters favor men candidates while Democratic voters prefer a women in office (e.g., Sanbonmatsu, 2002; King and Matland, 2003; Sanbonmatsu and Dolan, 2009; Schwarz and Coppock, 2022). However, very little is known about how this plays out in the European context with multiple parties competing rather than two. To the best of our knowledge, three prior studies provide some insight into this phenomenon in European multi-party systems, two of which make no further distinction among parties than a left/right dichotomy. Wilcox (1991), analyzing Eurobarometer data, showed that right-wing voters have less confidence in women legislators than in men legislators in five out of the eight countries studied. More recently, Dahl and Nyrup (2021) conducted a candidate choice experiment showing that left-wing voters prefer women candidates, while right-wing voters show no gender bias in Denmark. By contrast, Saha and Weeks (2020) did allow more fine-grained differences among parties, and show very little impact of partisanship on gender bias in preferences of candidates in the UK.

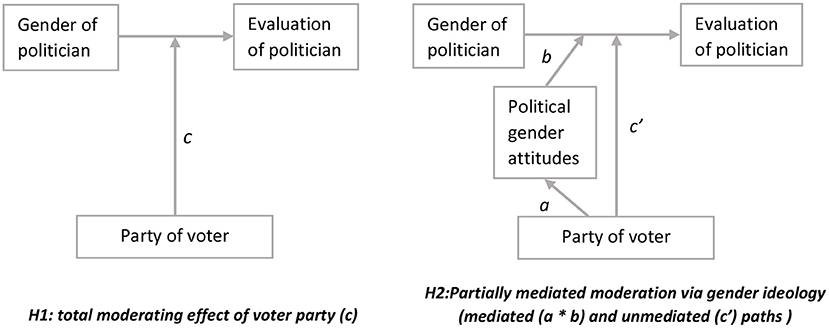

In all, little is known about the moderating role of voter party on gender differentiated favourability of politicians in Europe. In the remainder of this theory section, we argue why we expect that voters of some parties prefer men while those of other parties prefer women representatives. We propose two paths through which this party differentiated gender preference comes about: (1) voters of different parties have divergent attitudes about gender in politics (arrow a * b in Figure 1); and (2) because of ideologically laden gender stereotypes, men or women candidates may be directly more appealing to some party supporters (arrow c' in Figure 1). Figure 1 graphically displays the overall conditionality of voters' gender bias on party preference on the left side, while it outlines the two mechanisms on the right side. Before we further elaborate on these two mechanisms, we first posit the overall expectation in a hypothesis:

Figure 1. Causal model with total moderating effect on the left and mediated moderation on the right.

Hypothesis 1 (moderating effect of party preferences; arrow c in Figure 1):

Hypothesis 1.1: Right-wing -and particularly populist radical right- voters are biased in favor of men politicians.

Hypothesis 1.2: Left-wing -and particularly green left- voters are biased in favor of women politicians.

As the first mechanism, we posit that party ideology is associated with attitudes about gender in politics, which we refer to as political gender attitudes, and that these in turn lead to gender bias in candidate preferences. There is a long-established link on the party level between broader political ideology and ideas about gender. Economically left-wing political parties tend to promote egalitarian values (Saha and Weeks, 2020) and represent previously excluded groups, such as women (Matland and Studlar, 1996; Htun, 2005). Additionally, progressive, left-wing parties focus on post-materialist issues and favor expanding personal freedoms (Dalton, 1987); Bakker et al., 2015; see Röth and Schwander, 2021), espousing positive views on minority rights and traditional women's issues, such as equal pay, the right to abortion, and preventing gender-based violence. Historically, left-wing parties are linked to the women's movement (e.g., Jenson, 1985; Beckwith, 2000; Viterna and Fallon, 2008) and have strong women's organizations within the party that promote women's issues and representation (Franceschet and Thomas, 2015). Among left wing parties, Green parties have been particularly supportive of women in politics (Keith and Verge, 2018; O'Brien, 2018; Kantola and Lombardo, 2019; see also Caul, 2001). Greens were often the frontrunners in addressing feminist policy demands, such as childcare policies (Doherty, 2001), and are the strongest proponents of equal descriptive representation within their own organizations (i.e., by gender-related interventions in the recruitment process, see Reynolds, 1999).

Parties on the right, by contrast, usually stand for more traditional gender roles in society and are associated with social conservatism and traditional values (Wolbrecht, 2010; Saha and Weeks, 2020). In the UK, for instance, Conservative politicians have less positive attitudes about affirmative action for women and gender equality attitudes (such as the role of men and women within families) than politicians from the Labor party (Lovenduski and Norris, 2003). As a consequence of all this, liberal and left-wing political parties tend to do better in descriptive representation of women than conservative, right-wing parties (e.g., Caul, 1999; O'Brien, 2018, p. 105; Sundström and Stockemer, 2021). On the right side of the political spectrum, populist radical right parties stand out, having the reputation of ‘männerparteien' (Mudde, 2004; Spierings et al., 2015). O'Brien (2018), for instance, shows that nationalist far-right parties perform poorly compared to other right-wing parties, such as the Christian democrats and conservatives, in bringing women into parliament. Moreover, right-wing populist parties often employ an anti-feminist rhetoric and plead for traditional family roles, ending the discrimination of full-time mothers, and anti-abortion policies, while expressing ethnicized sexist claims (i.e., claims that immigrant, oftentimes Muslim, men are a physical/sexual threat to native women) (e.g., Akkerman, 2015; Berg, 2019), and femonationalist claims (i.e., presenting gender equality as core national value that is threatened by Muslim immigrants) (e.g., De Lange and Mügge, 2015; Fangen and Skjelsbæk, 2020).

While the preceding mainly concerns party ideology, these attitudes are also echoed in the parties' voter bases. Conservative voters in the US, for instance, score higher on modern sexism than liberal voters (Cassese et al., 2015), and research focusing on the 2016 US presidential elections shows that Republican voters score higher on the general sexist attitudes scale than Democratic voters (e.g., Blair, 2017; Bock et al., 2017; Valentino et al., 2018; Rothwell et al., 2019). Likewise, in various European countries, voting for left-wing parties is correlated to pro-feminist attitudes (e.g., Banaszak and Plutzer, 1993), while (far) right-wing party support is linked to stronger sexist attitudes (e.g., Lodders and Weldon, 2019). In addition, in both the US and Europe, there is a positive relationship between pro-environmentalist attitudes and feminist ideology (Somma and Tolleson-Rinehart, 1997).

Not only are broad ideas about gender in society linked to political ideology, left-wing and right-wing voters also differ in their more specific attitudes concerning women in politics, i.e., what we have called political gender attitudes (arrow a in Figure 1). In the US, for instance, Democratic voters have a stronger preference for gender parity in government than Republican voters (Dolan and Sanbonmatsu, 2009; Dolan and Lynch, 2015). In the European context, we similarly see that left-wing voters show more support for a higher number of women in political decision-making positions (Fernández and Valiente, 2021), while right-wing voters more often agree with the statement that men are better political leaders (Allen and Cutts, 2018).

Political gender attitudes, in turn, can be expected to result in a gender bias in candidate evaluations and voting behavior. Sanbonmatsu (2002), for instance, shows that voters have a “baseline gender preference,” i.e., a preference for a man or woman representative, all else equal, and that this baseline gender preference directly affects voting decisions. Paolino (1995) shows that voters who think it is important to have better descriptive representation of women in politics, are more likely to vote for a women candidate. Mo (2015), additionally, shows that citizens with a stronger bias in favor of men over women in political leadership positions, both measured explicitly and implicitly, are also more strongly inclined to vote for a men candidate over an equally qualified women candidate. Thus, we can expect that once voters have political gender preferences based on their ideology/partisanship (arrow a in Figure 1), they will also act accordingly and prefer/vote for men or women candidates based on their political gender attitudes (arrow b in Figure 1).

All in all, we expect right-wing (and particularly populist radical right) party supporters to have more conservative ideas about gender in politics, and we expect that those ideas lead to a preference for men politicians. Conversely, left-wing (particularly green) party supporters are expected to have favorable attitudes about women in politics, and those ideas are expected to lead to a preference for women politicians. In other words, we expect that the party-moderated biases in favor of men or women candidates of hypothesis 1, are party mediated via political gender attitudes (displayed in arrows a * b in Figure 1). However, we expect that the political gender attitudes mediate the moderation partly but not completely, for reasons we go into next.

Political gender attitudes, however, are not the only way in which party support is linked to a gender bias in candidate preferences. Even among voters with similar ideas about women in politics, men politicians might be more appealing to right-wing voters and women politicians to left-wing voter because of gender stereotypes. Stereotypes imply that identical characteristics are assigned to all members of a group, irrespective of the differences in characteristics within the group (e.g., Aronson, 2004). Voters have repeatedly been found to have gender stereotypes (e.g., Williams and Best, 1990; Brooks, 2013; Dolan, 2014), among which we can distinguish belief-, traits-, and issue gender stereotypes (Huddy and Terkildsen, 1993; Sanbonmatsu, 2002). Because of these stereotypes, left-wing and right-wing voters can have distinct candidate gender preferences, even without their political gender attitudes playing any part.

First, women are often assumed to be more left-leaning or liberal than their men colleagues. This belief-stereotype (or ideology-stereotype) received quite some empirical support. Koch (2000), for instance, compares the by voters' perceived ideology of politicians and their actual roll-call voting behavior and shows that women politicians are assumed to be more liberal than they actually are. Additionally, Huddy and Terkildsen (1993) show that women politicians are believed to be more liberal and more democratic than their men colleagues (see also Alexander and Andersen, 1993; Koch, 2000; King and Matland, 2003). If voters assume that women politicians are more left-leaning than their men opponents, then ideologically committed left-wing voters will have a stronger preference for women politicians and devoted right-wing voters a stronger preference for men politicians.

Second, and related to these belief-stereotypes, voters evaluate women and men differently in terms of their issue competencies. Women are thought to be particularly strong on compassionate issues like social welfare, health care, and the environment, while men are thought to be strong on issues like law and order, immigration, the military, terrorism, and fiscal policy (Huddy and Terkildsen, 1993; Sanbonmatsu, 2002; Lawless, 2004; Banwart, 2010; Holman et al., 2016). The compassionate issues that are linked to the feminine stereotype overlap strongly with the typical issues left-wing parties care about, while the so-called masculine issues are usually key policy issues for right-wing parties (e.g., Petrocik, 1996; Hayes, 2005; Green-Pedersen, 2007). Based on the stereotypical beliefs of issue importance and policy standpoints, thus, left-wing voters should be more likely to be attracted to women candidates and right-wing voters to men candidates.

Third, women and men are often believed to possess different character traits. Men are generally associated with agentic characteristics, such as aggressive, ambitious, independent, self-confident and active, while women are associated with more communal qualities such as empathetic, caring, emotional, and understanding (Kite et al., 2008; Banwart, 2010; Brooks, 2013; Bos et al., 2018). These trait stereotypes lead to distinct evaluations of candidates based on political ideology. Research shows that left-wing parties are strongly associated with communal traits while right-wing parties are more strongly linked to agentic traits (Hayes, 2005; see also e.g., Rule and Ambady, 2010; Winter, 2010). Thus, also based on the link between gender and partisan trait stereotypes, left-wing voters should be more inclined to prefer women candidates and right-wing voters men candidates.

In sum, the beliefs, traits and issues strengths associated with women politicians should be appealing to the left part of the electorate, and objectionable to the right2. Further, this appeal or repulsion should be especially apparent for voters of the most “extreme” parties on the left/right political spectrum: the populist radical right and the green left. Together, this implies that gender stereotypes should have different consequences for (populist) right-wing voters than they do for (green) left-wing voters. That is, if a women belief, trait or issue stereotype is applied in the mind of a right-wing voter, it functions as a push-factor, while for a left-wing voter it is a pull factor. Importantly, it can function as a push or pull factor regardless the ideas the voter has about the role of women in politics. In other words, this means that voter partisanship moderates the effect of candidate gender, also unmediated by political gender attitudes. In all, therefore, we expect that right-wing voters are biased in favor of men politicians and left-wing voters in favor of women (H1), and we expect this bias to be partially (path 1) but not fully (path 2) mediated by their explicit attitudes about gender in politics (H2):

Hypothesis 2 (Partially mediated moderation; arrows a * b and c' in Figure 1):

Hypothesis 2.1: Right-wing -and particularly populist radical right-voters' bias in favor of men politicians is partly mediated by political gender attitudes.

Hypothesis 2.2: Left-wing -and particularly green left-voters' bias in favor of women politicians is partly mediated by political gender attitudes.

The study was conducted in the Netherlands, a parliamentary democracy with an extremely proportional electoral system due to the low electoral threshold and single electoral district. Moreover, in this context, parties together with party leaders dominate electoral choice, while the rest of the parliamentary list plays only a small role. Thus, it is a context where one would not expect large effects of personal attributes of legislative candidates such as their gender. While it remains a single case-study, any gender bias we find could arguably be expected to be larger in more personal systems like the US or the UK.

To examine the preferences of various electorates with regards to the gender of politicians, and the extent to which those preferences are mediated by political gender attitudes, we developed a survey experiment. We fielded our experiment in the Dutch public opinion panel called EenVandaag, organized by a daily news show of the same name. This is an online self-application panel, of which around 25,000 unique respondents participate in their weekly online surveys. The data we use are collected in two waves, of which wave 1 (July 2019) took place 3 weeks before wave 2. In wave 1, we asked respondents about their political gender attitudes. In Wave 2, we included the survey experiment. The experiment consisted of a vignette that introduced respondents to a replacement representative. In the vignette, we randomized the gender of the politician by describing the politician using gendered pronouns (she/her/hers and he/his/him). To provide participants with contextual information, we explain that a Member of Parliament has to resign, and that the replacement representative is already experienced in local politics. This is a realistic scenario, as the Dutch electoral system uses a party-list, that indicates who is next in line to take up a seat for the party in Parliament. This replacement scenario allows us to inspect how voters evaluate the candidates a party puts on the list, but at the level of a single MP rather than an entire list, allowing us to isolate the effect of their gender.

The vignette describes the political party the politician belongs to, which we randomize over GreenLeft (GL), Christian Democrats (CDA), and the Populist Radical Right (PVV). These parties are, respectively, a left-wing opposition party, a confessional coalition party, and a right-wing opposition party. Additionally, we provide participants with some basic trait evaluations of the prospective politician, which we randomize over nine different traits, on which the fictitious politicians could either be evaluated positive or negative: competence, decisiveness, benevolence, listening to people, steadfastness, transparency, integrity, charisma, empathy. We developed two different versions of the vignette to which participants were randomly assigned: one in which the politician was described on all nine traits (N = 10,325) and one in which the candidate was only described in terms of one trait (N = 5,166). Appendix A shows an example of a full and small vignette. In the paper, we present results from a pooled analysis of both vignette types. The findings are substantively similar in separate analyses (reported in Appendix E), though they are mostly non-significant for the shorter version of the experiment. This is likely due to the smaller N per party electorate, but we cannot exclude the possibility that the type of vignette matters, for instance due to more prejudice suppression in this lower information context (see Horiuchi et al., 2021). After reading the vignette, respondents were asked to evaluate the proposed replacement representative.

In total, after accounting for missing values, 13,489 members of the EenVandaag panel participated in the experiment, 6,618 in the woman politician condition and 6,871 in the man politician condition. Of the participants, 27% identified as women, 73% as men and the mean age is 65 (SD = 11). Although the elderly, men and higher educated are overrepresented in the panel, it offers a broad cross-section of the Dutch population, and specifically political party electorates (see Appendix B), which suits the demands of our experiment. Appendix F replicates the main results, weighing for respondent gender.

The dependent variable is a rating of the fictitious politician that respondents were introduced to in the vignette. The rating variable asks how respondents evaluate the candidate overall on a scale from 0 (very negative) to 10 (very positive). Out dependent variable is thus not vote choice per se, something we come back to in the conclusion.

To measure political gender attitudes, we developed a scale including five items about the attitudes about gender in politics in the Netherlands (which were measured in Wave 1). We departed from the Classical and Modern Sexism scales (Swim et al., 1995; Ekehammar et al., 2000; Dierckx et al., 2017), but adapted the items to refer specifically to gender in politics, rather than society in general. Of the five items, two tapped into classical sexism (for example “men are more capable of making political decisions than women”), and three into modern sexism (for example, the reverse of “women get less chances in politics in the Netherlands than men”). Modern sexism has three components: denial of continuing discrimination, antagonism toward demands of women and resentment about special favors (Swim et al., 1995). We gave priority to the component denial of continuing discrimination with two items, and reserved only one item for a combination of antagonism toward demands and resentments about special favors. We did this so that people who oppose government action broadly speaking, would not score as gender conservative for opposing affirmative action. The exact wording of the items can be found in Appendix C. The reliability of the scale of the five items was good (Cronbach's alpha 0.82).

To establish respondents' political party preferences, we use a variable that asks about the party they voted for in the most recent national parliamentary election (2017). Below, we show the results in two ways: parties grouped into party families and all parties separately. The Green party family includes Groenlinks (Green Left, GL) and the Partij voor de Dieren (Animal Party, PvdD), the Labor/Socialists include the Socialistische Partij (Socialist Party, SP) and the Partij van de Arbeid (Labor party, PvdA), the Liberals include the Democraten 66 (Democrats, D66) and the Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (People's Party for Freedom and Democracy, VVD), the Christian party family includes the ChristenUnie (Christen Union, CU) and the Staatskundig Gereformeerde Partij (Reformed Political Party, SGP), the populist radical right party family includes the Partij voor de Vrijheid (Freedom Party, PVV) and the Forum voor Democractie (Forum for Democracy, FVD). 50Plus (Senior Party) voters are not included in the party family analyses because they fall outside the main party families, and Denk (Think, ethnic minority party) voters are excluded for their low number (seven respondents).

To model whether voters are biased against or in favor of women politicians, we interact dummies for the respondent's party family with a dummy variable for the gender of the politician, and calculate the effect of politician gender on the evaluation of the politician per party family. Thus, we understand the effect of the politician's gender on politicians' evaluation as gender bias, and we condition this effect on voter partisanship. To test hypothesis 1.1, we focus on the voters of the liberal (VVD and D66), Christian (CDA, CU, and SGP) and particularly radical right (PVV and FvD) party families. To test hypothesis 1.2, we focus on the voters of the Labor/Socialists (PvdA and SP) and particularly Green (GL and PvdD) party family. In all, hypothesis 1 establishes whether voters of certain party families are biased for or against women politicians through statistical moderation; hypothesis 2 further inspects to what extent this interaction effect is mediated by political gender attitudes (see Figure 1). In other words, this hypothesis assesses whether voters of certain party families hold progressive/conservative political gender attitudes, and whether these attitudes then moderate the gender bias, i.e., the effect of politician gender on evaluation of the politician. To examine this, we include the interaction between political gender attitudes and the gender of the politician in addition to the interaction between the party family and the gender of the politician, and compare the results to those of the model without this former interaction (see Hayes, 2017). The interaction between politician gender and party family in the model without political gender attitudes gives the total moderation of party family, while the interaction between politician gender and party family in the model with political gender attitudes indicates how much of the moderation is not mediated by political gender attitudes. Thus, by comparing the effect of politician gender per party family in the model with and without the political gender attitudes interaction, we can establish to what extent the party family differences in gender bias run through attitudes about women in politics3. Finally, while we test our hypotheses distinguishing between the electorates of the five party families, we subsequently we repeat the analyses distinguishing between 12 parties, to gain more fine-grained insight.

In our analyses, we control for level of education (low, medium, high), age, gender, the traits respondents encountered in the vignette experiment. In addition, as respondents randomly saw a vignette about one of three parties, we control for the party of the politician in the vignette and whether the party of the fictitious politician is a match to the respondent's own party preference in either a perfect match, a medium match (in the case of vignette party if Green Left party also left-wing opposition party, in case of CDA also coalition party, in case of PVV also right-wing opposition party), or no match. For our analysis, we ran a series of OLS regressions with various interaction effects.

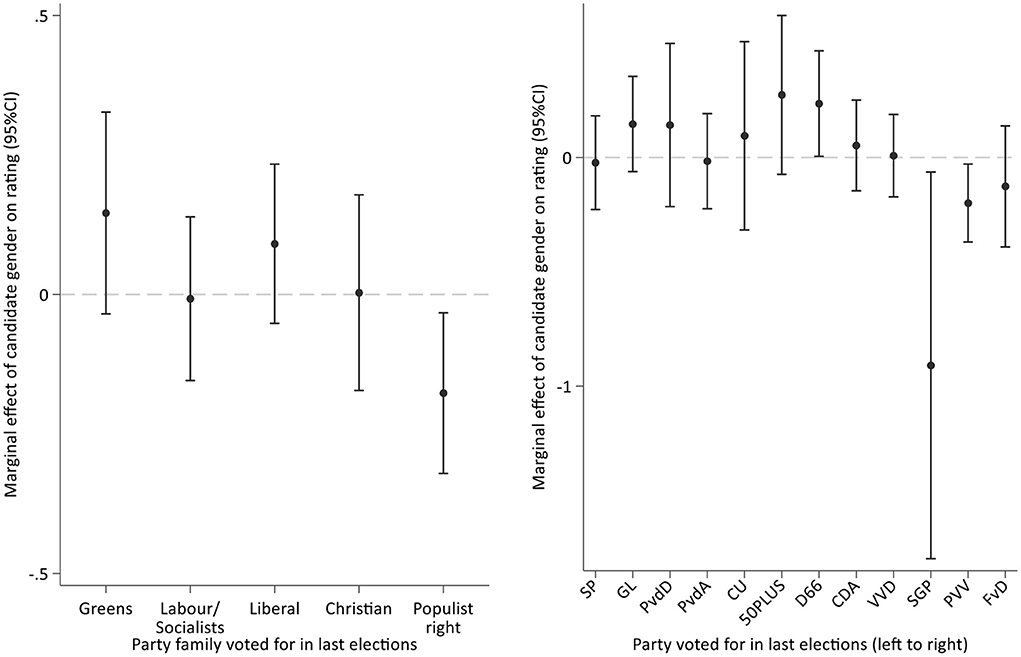

Are the voters of some parties biased in favor or against women legislators? Our first hypothesis states that on the one hand, left wing and particularly Green voters would be biased in favor of women politicians, while on the other hand right-wing and especially populist right voters would favor men. We model this by predicting the favourability toward a candidate by the gender of the candidate in interaction with the party family participants voted for, while controlling for demographic variables and other vignette properties. The left panel of Figure 2 displays the effect of legislator gender on their overall rating per party family (see Appendix D for full regression table). It shows that our expectations are partially supported. On the left flank, Green party voters are indeed more positive about a woman legislator, giving women a 0.15 higher rating on the ten-point scale, but this is only marginally significant (p = 0.113). Other left party voters taken together display no preference for either men or women, contrary to our expectation. Neither do voters of the liberal or Christian party families. Populist party voters, however, do espouse a preference for a men legislators, rating women 0.18 points lower on a ten-point scale (p = 0.016). All in all, both sides of hypothesis 1 are only partially supported.

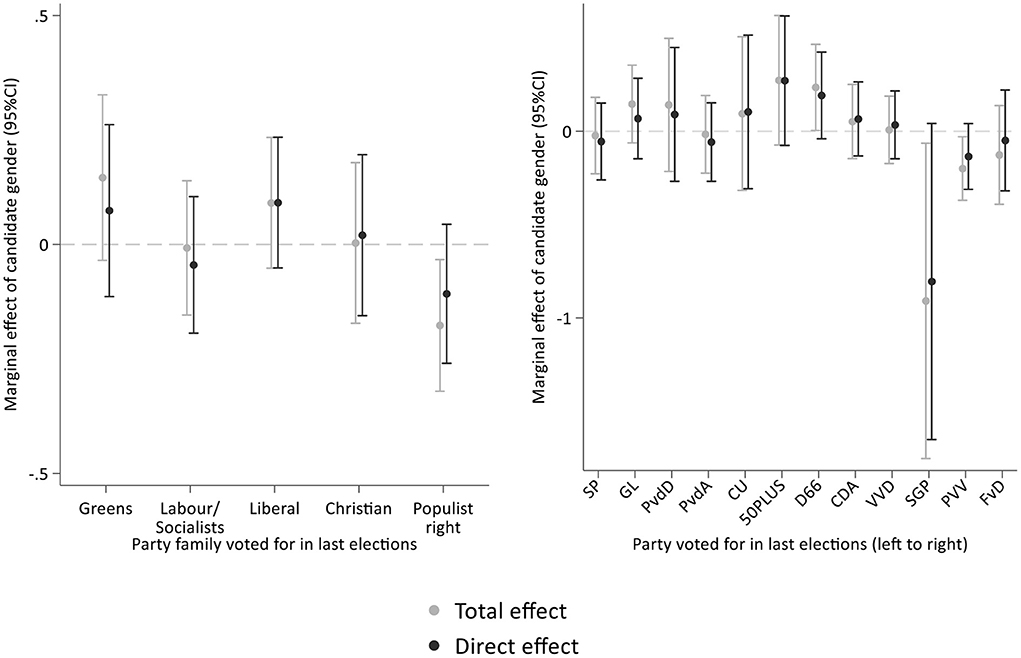

Figure 2. Total effect of voter party on gender bias. Full models in Appendix D. The left panel is based on model (1) in Appendix Table D1, the right panel is based on model (1) in Appendix Table D2.

The right panel of Figure 2 further splits out the results by party participants voted for, rather than party family. The parties are ordered by general left-right position (Jolly et al., 2022), which again shows that there is little support for the idea that gender bias is driven by left-right party attachment of the voter per se. Among the populist right parties we now see that PVV supporters have a clear and significant preference for a man legislator, while FvD supporters have a slightly smaller and non-significant preference for men. What jumps out most, however, is the strong preference for men representatives among voters of the small Christian party the SGP, who evaluate women almost an entire point lower than men (p = 0.035). This is perhaps not surprising, as this party only allows women as its representatives since 2013, and only did so after pressure from the Supreme Court. On the other side of the political spectrum, voters of the two Green parties, GL and PvdD, both prefer women legislators by about 0.15 (on the ten-point evaluation scale), but neither effect is statistically significant. Splitting out the liberal parties D66 and VVD shows that voters of the culturally more progressive D66 prefer women legislators by 0.24 (p = 0.045). Thus, summarizing the results thus far, there is evidence that populist right voters prefer men, weak evidence that Green party voters prefer women, and otherwise no clear left-right difference in gender bias.

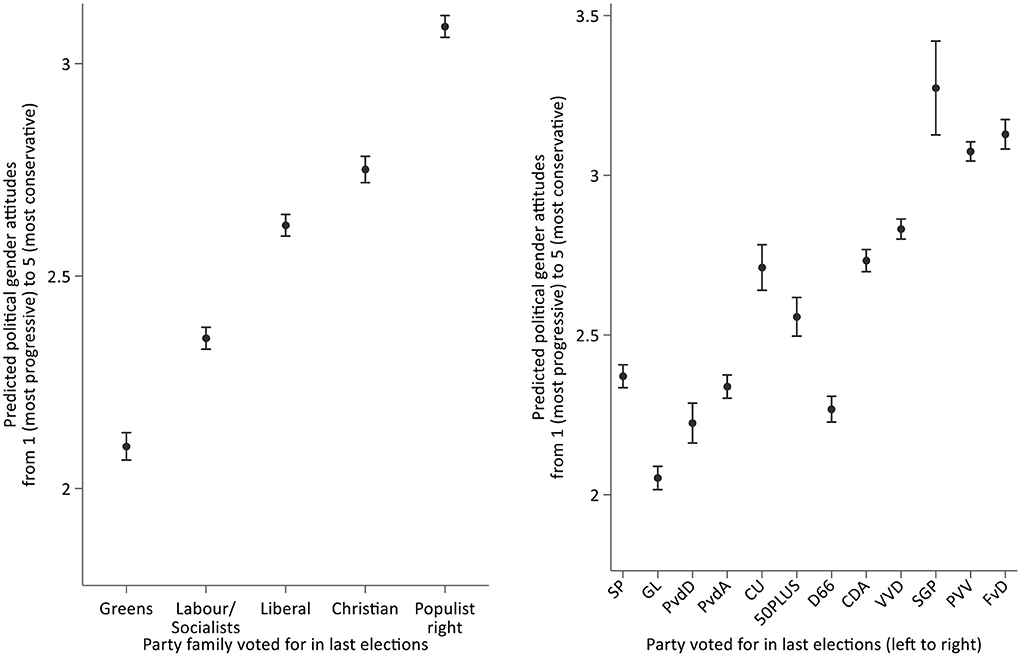

We now turn to the mechanisms for why some party voters prefer a man or a woman as representative. We begin by inspecting the first step in the mediated path we proposed, that is, by checking whether the voter bases of the various parties differ in their attitudes toward women in politics (arrow a in Figure 1). Figure 3 shows that they clearly do. On the left side of the figure, the party families line up in such a way that Greens have the most progressive gender attitudes, and populist right voters the most conservative. Voters of these two party families differ about one whole point on this four-point scale (p = 0.000). This is a substantial difference: Green voters are predicted to be at the 28th percentile in political gender attitudes, while populist right voters are considerably more conservative at the 75th percentile. Additionally, voters of traditional left parties (Labor/Socialists) have more progressive ideas about women in politics than right wing parties of the Liberal and Christian party families, with a difference of, respectively, 0.27 and 0.40 on the four-point scale. Splitting this out by party on the right side of the figure, we again see striking left-right pattern, with voters of left wing parties tending to be more progressive and right voters more conservative in their views on women in politics. Voters of the liberal party D66 form an exception, but that is not surprising given the progressive reputation and stance of this party on the cultural dimension. Also unsurprisingly, voters of the two small Christian parties CU and SGP stand out for their more conservative gender attitudes than suggested by their left-right position. The final exception to the left-right rule is the SP, whose voters have about the same ideas about women in politics as those of the Labor party (PvdA), while the party is more to the left.

Figure 3. Effect of voter party on political gender attitudes. Full models in Appendix D. The left panel is based on model (1) in Appendix Table D3, the right panel is based on model (2) in Appendix Table D3.

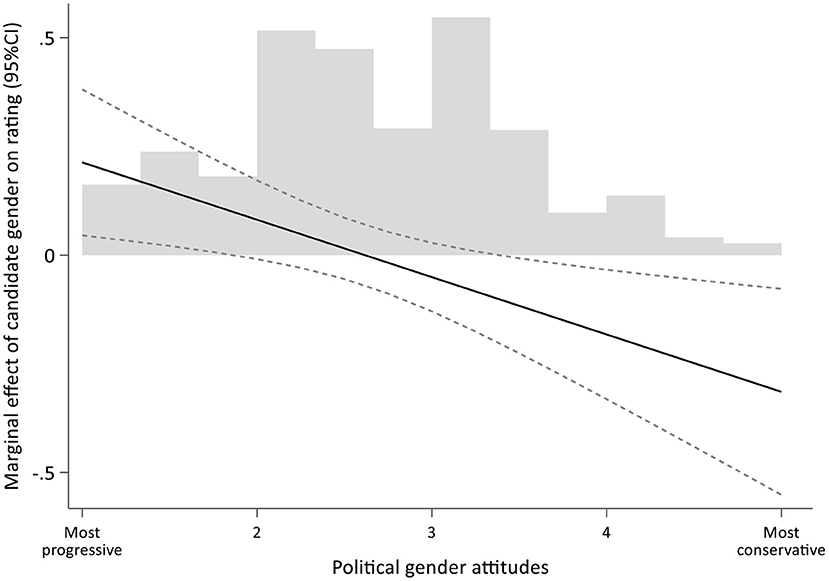

Next, do these attitudes about women in politics translate into bias toward a man or woman candidate? We examine the ensuing step in the mediating mechanism (arrow b in Figure 1) by adding the interaction between political gender attitudes and legislator gender to the model explaining rating, alongside the interaction between party family voted for and legislator gender. The added interaction is negative and significant (p = 0.006), indicating that political gender attitudes indeed affect bias toward a man or woman representative (see Appendix D for full results). Figure 4 illustrates this, showing that voters with progressive political gender attitudes rate women significantly more highly than men, while for voters with conservative political gender attitudes the opposite holds.

Figure 4. Effect of political gender attitudes on gender bias. Full models in Appendix D. This figure is based on Appendix Table D1 model (2).

Thus, party voter bases differ in their attitudes toward women in politics, and these attitudes predict whether they are biased in favor of men or women representatives, but can we conclude political gender attitudes mediate the effect of party support on gender bias? That is, to what extent do Green voters favor women legislators and populist right voters men legislators because of their ideas about the role of gender in politics? To study this, we compare the conditional effect of legislator gender by party voted for when modeled with, and without the interaction between legislator gender and political gender attitudes. If in that model the interaction effect between legislator gender and party is smaller, that informs us that this effect is mediated by the moderation between legislator gender and political gender attitudes. In other words, we compare the total effect of gender per party (arrow c in Figure 1) with the direct effect (arrow c' in Figure 1). Figure 5 compares the total effect (in gray) and direct effect (in black) for the party family model on the left again, and the party model on the right. On the left, we see that the direct effect of gender for Green party voters is quite a bit smaller than the total effect: it comprises about 51% of the original effect. Though this is an imprecise estimate, is says that about half the initial bias in favor of women candidates among Green voters can be attributed to their political gender attitudes. Similarly, of the preference for men among populist right voters, about 61% remains when controlling for political gender attitudes, so in our estimate about 39% runs through the mediated path. On the right side of the figure, these findings are seconded for Green parties GL (47% direct) and PvdD (64% direct) and populist right parties FvD (39% direct) and PVV (68% direct) separately. However, it is important to note that all of these estimates are very imprecise, and the mediated percentage may in reality be considerably larger or smaller.

Figure 5. Comparison of total and direct effect of voter party on gender bias. Full models in Appendix D. The left panel is based on models (1) and (3) in Appendix Table D1, the right panel is based on models (1) and (3) in Appendix Table D2.

Do voters contribute to the underrepresentation of women in politics? Although most recent research shows no gender bias in voter preferences (e.g., Dolan, 2014; Hayes and Lawless, 2016; Bridgewater and Nagel, 2020; Schwarz and Coppock, 2022), we posit that voters do help explain women's political underrepresentation, although not all voters to an equal extent. We expected that gender bias in the electorate is dependent on partisanship and that right—and especially populist radical right—voters are biased in favor of men politicians, while left—and especially green left—voters are biased in favor of women politicians. The findings partially support our expectations: Although most moderate left or right party voters show no clear gender preference in political candidates, Green party voters tend to favor a woman candidate, while right-wing populist party voters prefer a man candidate. Additionally, our findings show that the impact of party support on gender bias is partly mediated through political gender attitudes, i.e., the attitudes about women in politics. Around half of the impact of voting for the Green or the right-wing populist party on candidate gender preferences runs through these political gender attitudes.

There are two main take-aways from this study. First, we show that partisanship impacts voters' gender bias. Most studies on the impact of ideology or partisanship on gender bias are located in the two-party system of the US and reveal that Republican voters prefer men candidates while Democratic voters favor women politicians (see for instance Sanbonmatsu, 2002; King and Matland, 2003; Sanbonmatsu and Dolan, 2009; Schwarz and Coppock, 2022). Much less in known about the impact of partisanship on gender bias in the European context, in with the multi-party systems lend themselves for a more detailed differentiation between parties (but see Wilcox, 1991; Saha and Weeks, 2020; Dahl and Nyrup, 2021). Our experiment demonstrates that not all voters show a gender bias, only the voters from the “extreme” parties.

This first conclusion represents both good news and bad news for the representation of women in politics. On the one hand, this shows that female underrepresentation of women cannot be explained with supply-side explanations only, such as gendered party recruitment (Sanbonmatsu, 2006; Preece et al., 2016); Verge and Claveria, 2018) or gender differentiated media coverage of men and women politicians (e.g., Van der Pas and Aaldering, 2020), but that there is also voter demand for male overrepresentation. While an anti-women preference was present in only a relatively small part of the electorate, it is located exactly in the electorates of the parties which can do most to bring women into parliament. To illustrate, if the populist right and SGP would increase their parliamentary fractions to half women, female representation in the Dutch Lower House would jump from 61 (41%) to 70 (47%)4. Their electorates, however, unfortunately give them no reason to do so. On the other hand, the positive news is that other right-wing parties, or any of the other parties for that matter, face no electoral disincentive to place more women on their lists. This is encouraging considering that the descriptive underrepresentation of women in politics mainly stems from right-wing parties (e.g., Caul, 1999; O'Brien, 2018, p. 105; Sundström and Stockemer, 2021). To illustrate again with the Dutch case, this means that a party like the VVD, with currently 26% women in the Lower House, can aim for gender parity in parliament without fearing backlash from their electorate.

Second, this paper shows that the impact of partisanship on gender bias in candidate preferences is partly, but not fully, mediated by political gender attitudes. With our newly developed scale of political gender attitudes, we not only corroborate previous studies' results that left-wing voters have more progressive and right-wing voters more conservative attitudes about women in politics, but we also show the explanatory power of these attitudes in candidate preferences. The political gender attitudes mediate the effect of partisanship and explain around half of the impact of partisanship on gender bias. A fruitful line of further research could examine the causes of political gender attitudes, and particularly whether voters lead or follow their party elites on these. This is a pressing question in light of the growing electoral support for the populist right, which could potentially lead to a larger share of the electorate adopting conservative ideas about women in politics.

Our study is of course not without limitations. Most importantly, even though theoretically we are interested in gender bias in voting behavior, what we test in our analyses is a gender bias in candidate evaluations. Although previous research shows that candidate evaluations have an impact on voting behavior (e.g., Mughan, 2000; Bittner, 2011; Garzia, 2013; Lobo and Curtice, 2014; Aaldering, 2018), electoral decisions include many more factors, especially in the Dutch electoral system with party-list proportional representation. Future studies should test whether partisanship in the multi-party context of European democracies also directly affects gender bias in vote choice. Furthermore, although our findings largely corroborate similar research from the US, it relies on a single exposure experiment in the case of the Netherlands and generalizability to other multi-party systems can only be done with great caution. We invite future research to study the impact of partisanship on voters' gender bias experimentally or using observational data from other multi-party electoral contexts and highlight the urgent need for more comparative work on this topic.

All in all, this study shows that voters to some extent indeed contribute to the ongoing underrepresentation of women in politics: some parties have electoral incentives to be hesitant about promoting women politicians. However, this only applies to right-wing populist parties, mainstream right-wing parties face no electoral risk in putting forth women politicians. Generally, this could be explained as positive news for future women candidates, as it shows that the electorates of many parties that currently lack behind in the descriptive representation of women in politics have no electoral motive to do so.

The raw data and replication files are available upon request.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by AISSR Ethics Advisory Board of the University of Amsterdam. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

DP and LA wrote most of the paper and responsible for formulating the research question and hypotheses. DP, LA, and ES designed the study. ES collected the data and performed the majority of the analyses. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version

DP was supported by a grant from the Dutch Research Council (Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, Grant 451-17-025). LA was supported by a grant from the Dutch Research Council (Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, Grant VI.Veni.201R.068).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.921252/full#supplementary-material

1. ^https://data.ipu.org/women-ranking?month=2&year=2022 (accessed March 21, 2022).

2. ^This particularly holds if we assume voters prefer their representative to be less centrist than themselves, see Rabinowitz and Macdonald (1989).

3. ^This is similar to a regular strategy used to study mediation, where a model with and without the mediator are compared. In this case, as we study mediated moderation rather than mediation, rather than a simple mediator, the mediator is added in interaction with gender of the politician (see Hayes, 2017).

4. ^This applies to the Dutch Tweede Kamer as of April 2022. Counted as populist right are PVV, FvD, and off-shoot fractions formerly part of FvD.

Aaldering, L. (2018). The (ir) rationality of mediated leader effects. Elect. Stud. 54, 269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2018.04.010

Akkerman, T. (2015). Gender and the radical right in Western Europe: a comparative analysis of policy agendas. Patterns Prejud. 49, 37–60. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2015.1023655

Alexander, D., and Andersen, K. (1993). Gender as a factor in the attribution of leadership traits. Polit. Res. Q. 46, 527–545. doi: 10.1177/106591299304600305

Allen, P., and Cutts, D. (2018). How do gender quotas affect public support for women as political leaders?. West Eur Polit. 41, 147–168.

Anzia, S. F., and Berry, C. R. (2011). The Jackie (and Jill) Robinson effect: why do congresswomen outperform congressmen? Am. J. Polit. Sci. 55, 478–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00512.x

Bakker, R., De Vries, C., Edwards, E., Hooghe, L., Jolly, S., Marks, G., et al. (2015). Measuring party positions in Europe: the chapel hill expert survey trend file, 1999–2010. Party Pol. 21, 143–152. doi: 10.1177/1354068812462931

Banaszak, L. A., and Plutzer, E. (1993). Contextual determinants of feminist attitudes: national and subnational influences in Western Europe. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 87, 147–157. doi: 10.2307/2938962

Banwart, M. C. (2010). Gender and candidate communication: effects of stereotypes in the 2008 election. Am. Behav. Sci. 54, 265–283. doi: 10.1177/0002764210381702

Bauer, N. M. (2020). The Qualifications Gap: Why Women Must be Better Than Men to Win Political Office. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108864503

Beckwith, K. (2000). Beyond compare? Women's movements in comparative perspective. Euro. J. Polit. Res. 37, 431–468. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00521

Berg, L. (2019). “Between anti-feminism and ethnicized sexism: far-right gender politics in Germany”, in Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right. Online actions and offline consequences in Europe and the US, eds M. Fielitz and N. Thurston (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag), 79–92.

Bittner, A. (2011). Platform or Personality?: The Role of Party Leaders in Elections. Oxford: OUP Oxford. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199595365.003.0006

Blair, K. L. (2017). Did secretary Clinton lose to a ‘basket of deplorables'? An examination of islamophobia, homophobia, sexism and conservative ideology in the 2016 US presidential election. Psychol. Sex. 8, 334–355. doi: 10.1080/19419899.2017.1397051

Bock, J., Byrd-Craven, J., and Burkley, M. (2017). The role of sexism in voting in the 2016 presidential election. Pers. Individ. Dif. 119, 189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.026

Bos, A. L., Schneider, M. C., and Utz, B. L. (2018). “Navigating the political labyrinth: gender stereotypes and prejudice in U.S. elections,” in APA Handbook of the Psychology of Women: Perspectives on Women's Private and Public Lives, eds C. B Travis, J. W. White, A. Rutherford, W. S. Williams, S. L. Cook, and K. F. Wyche (Washington: American Psychological Association), 367–384. doi: 10.1037/0000060-020

Bridgewater, J., and Nagel, R. U. (2020). Is there cross-national evidence that voters prefer men as party leaders? Electo. Stud. 67, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102209

Brooks, D. J. (2013). “He runs, she runs,” in He Runs, She Runs. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400846191

Cassese, E. C., Barnes, T. D., and Branton, R. P. (2015). Racializing gender: Public opinion at the intersection. Polit. Gend. 11, 1–26. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X14000567

Caul, M. (1999). Women's representation in parliament: the role of political parties. Party Polit. 5, 79–98. doi: 10.1177/1354068899005001005

Caul, M. (2001). Political parties and candidate gender policies: a cross-national study. J. Polit. 63, 1214–1229. doi: 10.1111/0022-3816.00107

Dahl, M., and Nyrup, J. (2021). Confident and cautious candidates: explaining under-representation of women in Danish municipal politics. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 60, 199–224. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12396

Dalton, R. J. (1987). Generational change in elite political beliefs: the growth of ideological polarization. J. Polit. 49, 976–997. doi: 10.2307/2130780

De Lange, S. L., and Mügge, L. M. (2015). Gender and right-wing populism in the low countries: ideological variations across parties and time. Patt. Prejudice 49, 61–80. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2015.1014199

Dierckx, M., Meier, P., and Motmans, J. (2017). “Beyond the box”: a comprehensive study of sexist, homophobic, and transphobic attitudes among the Belgian population. Digest. J. Diver. Gend. Stud. 4, 5–34. doi: 10.11116/digest.4.1.1

Dolan, K., and Lynch, T. (2015). Making the connection? Attitudes about women in politics and voting for women candidates. Polit. Groups Ident. 3, 111–132. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2014.992796

Dolan, K., and Sanbonmatsu, K. (2009). Gender stereotypes and attitudes toward gender balance in government. Am. Polit. Res. 37, 409–428. doi: 10.1177/1532673X08322109

Dolan, K. A. (2014). When Does Gender Matter? Women Candidates and Gender Stereotypes in American Elections. New York: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199968275.001.0001

Ekehammar, B., Akrami, N., and Araya, T. (2000). Development and validation of Swedish classical and modern sexism scales. Scand. J. Psychol. 41, 307–314. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00203

Fangen, K., and Skjelsbæk, I. (2020). special issue on gender and the far right. Polit. Relig. Ideol. 21, 411–415. doi: 10.1080/21567689.2020.1851866

Fernández, J. J., and Valiente, C. (2021). Gender quotas and public demand for increasing women's representation in politics: an analysis of 28 European countries. Euro. Polit. Sci. Rev. 13, 1–20. doi: 10.1017/S1755773921000126

Fortin-Rittberger, J., and Rittberger, B. (2015). Nominating women for Europe: exploring the role of political parties' recruitment procedures for European Parliament elections. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 54, 767–783. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12101

Fox, R. L., and Lawless, J. L. (2010). If only they'd ask: gender, recruitment, and political ambition. J. Polit. 72, 310–326. doi: 10.1017/S0022381609990752

Fox, R. L., and Lawless, J. L. (2011). Gendered perceptions and political candidacies: a central barrier to women's equality in electoral politics. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 55, 59–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00484.x

Fox, R. L., and Lawless, J. L. (2014). Uncovering the origins of the gender gap in political ambition. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 108, 499–519. doi: 10.1017/S0003055414000227

Franceschet, S., and Thomas, G. (2015). Resisting parity: gender and cabinet appointments in Chile and Spain. Polit. Gend. 11, 643–664. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X15000392

Garzia, D. (2013). The rise of party/leader identification in Western Europe. Polit. Res. Q. 66, 533–544. doi: 10.1177/1065912912463122

Green-Pedersen, C. (2007). The growing importance of issue competition: the changing nature of party competition in Western Europe. Polit. Stud. 55, 607–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00686.x

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford publications.

Hayes, D. (2005). Candidate qualities through a partisan lens: a theory of trait ownership. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 49, 908–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00163.x

Hayes, D., and Lawless, J. L. (2016). Women on the Run: Gender, Media, and Political Campaigns in a Polarized Era. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316336007

Holman, M. R., Merolla, J. L., and Zechmeister, E. J. (2016). Terrorist threat, male stereotypes, and candidate evaluations. Polit. Res. Q. 69, 134–147. doi: 10.1177/1065912915624018

Horiuchi, Y., Markovich, Z., and Yamamoto, T. (2021). Does conjoint analysis mitigate social desirability bias? Polit. Anal. 1–15. doi: 10.1017/pan.2021.30

Htun, M. (2005). Women, Political Parties and Electoral Systems in Latin America. Women Parliament: Beyond Numbers, 112–121.

Huddy, L., and Terkildsen, N. (1993). Gender stereotypes and the perception of male and female candidates. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 119–147. doi: 10.2307/2111526

Jenson, J. (1985). Struggling for identity: the women's movement and the state in Western Europe. West Eur. Polit. 8, 5–18. doi: 10.1080/01402388508424551

Jolly, S., Bakker, R., Hooghe, L., Marks, G., Polk, J., Rovny, J., et al. (2022). Chapel hill expert survey trend file, 1999-2019. Elect. Stud. 75, 102420. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102420

Kantola, J., and Lombardo, E. (2019). Populism and feminist politics: the cases of Finland and Spain. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 58, 1108–1128. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12333

Karpowitz, C. F., Monson, J. Q., and Preece, J. R. (2017). How to elect more women: gender and candidate success in a field experiment. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 61, 927–943. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12300

Keith, D. J., and Verge, T. (2018). Nonmainstream left parties and women's representation in Western Europe. Party Politics 24, 397–409. doi: 10.1177/1354068816663037

King, D. C., and Matland, R. E. (2003). Sex and the grand old party: an experimental investigation of the effect of candidate sex on support for a Republican candidate. Am. Polit. Res. 31, 595–612. doi: 10.1177/1532673X03255286

Kite, M. E., Deaux, K., and Haines, E. L. (2008). “Gender stereotypes,” in Psychology of Women: Handbook of Issues and Theories, Chapter 7, 2nd edn, eds F. Denmark, and M. A. Paludi (Greenwood Publishing Group).

Koch, J. W. (2000). Do citizens apply gender stereotypes to infer candidates' ideological orientations? J. Polit. 62, 414–429. doi: 10.1111/0022-3816.00019

Lawless, J. L. (2004). Women, war, and winning elections: gender stereotyping in the post-September 11th era. Polit. Res. Q. 57, 479–490. doi: 10.1177/106591290405700312

Lawless, J. L., and Fox, R. L. (2010). It still takes a candidate: why women don't run for office. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511778797

Lazarus, J., and Steigerwalt, A. (2018). Gendered Vulnerability: How Women Work Harder to Stay in Office. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.9718595

Lobo, M. C., and Curtice, J. (Eds.). (2014). Personality Politics?: The Role of Leader Evaluations in Democratic Elections. Oxford: OUP Oxford.

Lodders, V., and Weldon, S. (2019). Why do women vote radical right? Benevolent sexism, representation and inclusion in four countries. Representation 55, 457–474. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2019.1652202

Lovenduski, J., and Norris, P. (2003). Westminster women: the politics of presence. Polit Stud. 51, 84–102.

Matland, R. E., and Studlar, D. T. (1996). The contagion of women candidates in single-member district and proportional representation electoral systems: Canada and Norway. J. Polit. 58, 707–733. doi: 10.2307/2960439

Mo, C. H. (2015). The consequences of explicit and implicit gender attitudes and candidate quality in the calculations of voters. Polit. Behav. 37, 357–395. doi: 10.1007/s11109-014-9274-4

Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Govern. Opposite. 39, 541–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

Mügge, L. M., and Runderkamp, Z. (2019). “De tweede sekse in politiek en openbaar bestuur: Verklaringen en oplossingen voor de ondervertegenwoordiging van vrouwen”, in Op weg naar een betere m/v-balans in politiek en bestuur, eds L. Mügge, Z. Runderkamp, and M. Kranendonk (Democratie in Actie), 5–17, 35–38. Available online at: https://www.lokale-democratie.nl/essaybundelop-weg-naar-een-betere-mv-balans-politiek-en-bestuur

Mughan, A. (2000). Media and the Presidentialization of Parliamentary Elections. New York: Springer. doi: 10.1057/9781403920126

Norris, P. (1996). “Legislative recruitment,” in Comparing Democracies: Elections and Voting in Global Perspective, eds L. LeDuc, R.G. Niemi, and P. Norris (London: SAGE).

O'Brien, D. Z. (2015). Rising to the top: gender, political performance, and party leadership in parliamentary democracies. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 59, 1022–1039. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12173

O'Brien, D. Z. (2018). “Righting” conventional wisdom: women and right parties in established democracies. Polit. Gend. 14, 27–55. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X17000514

O'Brien, D. Z., Mendez, M., Peterson, J. C., and Shin, J. (2015). Letting down the ladder or shutting the door: female prime ministers, party leaders, and cabinet ministers. Polit. Gend. 11, 689–717. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X15000410

Paolino, P. (1995). Group-salient issues and group representation: support for women candidates in the 1992 Senate elections. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 294–313. doi: 10.2307/2111614

Petrocik, J. R. (1996). Issue ownership in presidential elections, with a 1980 case study. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 825–850. doi: 10.2307/2111797

Preece, J. R., Stoddard, O. B., and Fisher, R. (2016). Run, Jane, run! Gendered responses to political party recruitment. Polit. Behav. 38, 561–577. doi: 10.1007/s11109-015-9327-3

Rabinowitz, G., and Macdonald, S. E. (1989). A directional theory of issue voting. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 83, 93–121. doi: 10.2307/1956436

Reynolds, A. (1999). Women in the legislatures and executives of the world: knocking at the highest glass ceiling. World Polit. 51, 547–572. doi: 10.1017/S0043887100009254

Röth, L., and Schwander, H. (2021). Greens in government: the distributive policies of a culturally progressive force. West Eur. Polit. 44, 661–689. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2019.1702792

Rothwell, V., Hodson, G., and Prusaczyk, E. (2019). Why pillory hillary? Testing the endemic sexism hypothesis regarding the 2016 US election. Pers. Individ. Dif. 138, 106–108. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.09.034

Rule, N. O., and Ambady, N. (2010). Democrats and Republicans can be differentiated from their faces. PLoS ONE 5, e8733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008733

Saha, S., and Weeks, A. C. (2020). Ambitious women: gender and voter perceptions of candidate ambition. Polit. Behav. 44, 779–805. doi: 10.1007/s11109-020-09636-z

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2002). Gender stereotypes and vote choice. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 20–34. doi: 10.2307/3088412

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2006). Where Women Run: Gender and Party in the American States. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.168630

Sanbonmatsu, K., and Dolan, K. (2009). Do gender stereotypes transcend party? Polit. Res. Q. 62, 485–494. doi: 10.1177/1065912908322416

Schneider, M. C., Holman, M. R., Diekman, A. B., and McAndrew, T. (2016). Power, conflict, and community: how gendered views of political power influence women's political ambition. Polit. Psychol. 37, 515–531. doi: 10.1111/pops.12268

Schwarz, S., and Coppock, A. (2022). What have we learned about gender from candidate choice experiments? A meta-analysis of sixty-seven factorial survey experiments. J. Polit. 84, 716290. doi: 10.1086/716290

Somma, M., and Tolleson-Rinehart, S. (1997). Tracking the elusive green women: sex, environmentalism, and feminism in the United States and Europe. Polit. Res. Q. 50, 153–169. doi: 10.1177/106591299705000108

Spierings, N., Zaslove, A., Mügge, L. M., and de Lange, S. L. (2015). Gender and populist radical-right politics: an introduction. Patt. Prejudice 49, 3–15. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2015.1023642

Sundström, A., and Stockemer, D. (2021). Political party characteristics and women's representation: the case of the European Parliament. Representation 58, 119–137. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2021.1898458

Swim, J. K., Aikin, K. J., Hall, W. S., and Hunter, B. A. (1995). Sexism and racism: old-fashioned and modern prejudices. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 68, 199. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.68.2.199

Valentino, N. A., Wayne, C., and Oceno, M. (2018). Mobilizing sexism: the interaction of emotion and gender attitudes in the 2016 US presidential election. Public Opin. Q. 82, 799–821. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfy003

Van der Pas, D. J., and Aaldering, L. (2020). Gender differences in political media coverage: a meta-analysis. J. Commun. 70, 114–143. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqz046

Verge, T., and Claveria, S. (2018). Gendered political resources: the case of party office. Party Polit. 24, 536–548. doi: 10.1177/1354068816663040

Viterna, J., and Fallon, K. M. (2008). Democratization, women's movements, and gender-equitable states: a framework for comparison. Am. Sociol. Rev. 73, 668–689. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300407

Wilcox, C. (1991). The causes and consequences of feminist consciousness among Western European women. Comp. Polit. Stud. 23, 519–545. doi: 10.1177/0010414091023004005

Williams, J. E., and Best, D. L. (1990). Measuring Sex Stereotypes: A Multination Study. Washington: Sage Publications, Inc.

Winter, N. J. (2010). Masculine republicans and feminine democrats: gender and Americans' explicit and implicit images of the political parties. Polit. Behav. 32, 587–618. doi: 10.1007/s11109-010-9131-z

Keywords: gender bias, candidate evaluations, political parties, gender attitudes, gender stereotypes

Citation: Pas DJvd, Aaldering L and Steenvoorden E (2022) Gender bias in political candidate evaluation among voters: The role of party support and political gender attitudes. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:921252. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.921252

Received: 15 April 2022; Accepted: 04 July 2022;

Published: 04 August 2022.

Edited by:

Marta Fraile, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), SpainReviewed by:

Andrew Q. Philips, University of Colorado Boulder, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Pas, Aaldering and Steenvoorden. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daphne Joanna van der Pas, ZC5qLnZhbmRlcnBhc0B1dmEubmw=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.