- Department of Sociology, Radboud Social and Cultural Research, Radboud University, Nijmegen, Netherlands

Right-wing populist voices argue that Muslims do not belong in Western Europe because Islam opposes the “core Western value” of women's empowerment. Ironically, such hostilities could cause European Muslims to reject antagonistic natives and their “Western values,” potentially creating backlashes in Muslims' support for gender equality. Delving into this possibility, this study diverges from simple conceptualizations of one inherently patriarchal Islam to study the diversity among Muslims in the gendered meanings they attach to their religion in different contexts. Empirically, we use a uniquely pooled dataset covering over 9,000 European Muslims in 16 Western European countries between 2008 and 2019. Multilevel models show that while mosque attendance limits support for public-sphere gender equality, religious identifications only do so among men and individual prayer only among women. Additionally, our results tentatively indicate that in more hostile contexts, prayer's effects become more patriarchal while religious identification's connection to opposition to gender equality weakens. We conclude that Islamic religiosities shape Muslims' support for public-sphere gender equality in far more complex ways than any right-wing populist claim on one essential patriarchal Islam captures.

Introduction

When considering opposition to gender equality in Western Europe, one group that is emphasized in public debates time and again concerns Muslim citizens (Roggeband and Verloo, 2007; Yilmaz, 2015). Right-wing populists argue in one breath that feminism and “gender theory” are elitist projects that go against the will of the people and simultaneously that Muslims do not belong in Western Europe because Islam opposes the “core Western value” of women's empowerment (Mayer et al., 2014; Spierings and Glas, 2021). While other works considered the first part and studied right-wing populist backlashes in support of women's rights generally (e.g., Norris and Inglehart, 2019; Lombardo et al., 2021), few have turned their attention to whether such hostilities also engender backlashes among Muslim citizens themselves (cf. Glas, 2022a; Röder and Spierings, 2022). How do Muslims connect their religion to women's emancipation in hostile contexts that tell them Islam necessarily opposes gender equality?

This study unpacks the relation between Islamic religiosity and support for (or hostility toward) gender equality, by disaggregating Islamic religiosity and assessing how its impacts are dependent on the hostility of the context. In doing so, we diverge from both right-wing populists' assumptions that there is one essentialist Islam that is necessarily hostile to women's empowerment (Güngör et al., 2013; Phalet et al., 2013; Kogan and Weißmann, 2020) and the majority of public studies that compare Muslims to other people and attribute any differences to patriarchal Islam (e.g., Diehl et al., 2009; Norris and Inglehart, 2012; Kalmijn and Kraaykamp, 2018). Instead of one patriarchal Islam, we argue that there is great diversity in the meanings Muslims attach to their religion and therefore disaggregate Islamic religiosity and its effects in different contexts.

Our theoretical starting point is that religious interpretations are not stable and fixed truisms but rather arise from active, meaning-giving processes that are gendered, subject to change, and dependent on contextual circumstances. Qualitative studies have argued that particularly migrants (rather than non-migrants) and women (rather than men) tend to be incredibly resourceful in reinterpreting Islam to meet the demands of their host societies (Read and Bartkowski, 2000; Predelli, 2004; Cesari, 2014; Rinaldo, 2014; Nyhagen, 2019). Similarly, an emerging strand of quantitative work has shown that varying dimensions of Islamic religiosity can shape gender values in different and context-dependent ways (Ginges et al., 2009; Glas et al., 2019; Beller et al., 2021; Glas and Spierings, 2021). Some conditions allow Muslim migrants to “decouple” religiosity from gender equality, i.e., combine the two (Van Klingeren and Spierings, 2020; Glas, 2022b; Röder and Spierings, 2022), whereas other circumstances spur reactionary religiosity (Wimmer and Soehl, 2014; Maliepaard and Alba, 2016). This all implies that the ways Islamic religiosities shape support for public-sphere gender equality are (a) multidimensional and (b) conditional.

Therefore, the goal of this study is to argue and test whether the ways that mosque attendance, the strength of religious identification, and individual prayer shape support for gender equality in the public sphere in Western Europe are gendered, and depend on the hostility of the context, and have changed over the years (2008–2019). First, we expect that men and women engage differently with dominant religious doctrines because religious socialization and mainstream interpretations of religious prescriptions are gendered (Scheible and Fleischmann, 2013; Glas et al., 2018; Van Klingeren and Spierings, 2020). Additionally, we argue that Muslim citizens respond to hostile Western European societies that portray Muslims as gender traditional others by closing ranks and reasserting the value of gender traditionalism, resulting in more reactionary religious interpretations (Roggeband and Verloo, 2007; Fleischmann et al., 2011; Phalet et al., 2013). However, these processes have to be disentangled from another societal trend that prominent qualitative scholars have noted has happened simultaneously: the emergence of a more individualized, postmodern “European Islam” over time (Duderija, 2007b; Kaya, 2010; Cesari, 2014). If European Islam has gained ground, Muslims should have increasingly decoupled their religiosity from gender values over the years, even in the face of growing hostilities (Alba, 2005; Güngör et al., 2013; Glas, 2021; Röder and Spierings, 2022). Ultimately, this study sheds further light on the conditions under which Islamic religiosity is a barrier to emancipatory values—and when it can be a bridge (Foner and Alba, 2008).

Theory

The bulk of existing quantitative migration studies concludes that Islam hinders migrants' integration based on comparisons between Muslim minorities and natives (e.g., Diehl et al., 2009; Norris and Inglehart, 2012; Kalmijn and Kraaykamp, 2018). While these existing works show that people who adhere to a denomination and Muslims in particular average lower support for gender equality than non-religious people, this tells us little about how or why religiosity decreases gender egalitarianism. Indeed, qualitative migration scholars have shown great diversity in how Muslims live their religion, so there is no such thing as one (patriarchal) interpretation of Islam to which all Muslims adhere similarly (e.g., Duderija, 2007b; Jeldtoft, 2011). Similarly, sociologists of religion have long argued that religiosity cannot be flattened to denominational differences (e.g., Stark and Glock, 1968; Cornwall et al., 1986). They argue that “religion” is a complex phenomenon that spans multiple beliefs, feelings, and practices that are not interchangeable. This study, therefore, conceptualizes “religiosity” multi-dimensionally, which promises to lead to a more in-depth understanding of how exactly Islamic religiosity shapes gender attitudes.

More specifically, we disentangle mosque attendance, feelings of identification, and individual prayer. We do not argue that these three together provide a complete picture of Muslims' religiousness, but we do restrict our—already complex—theorization to these dimensions, which we can assess empirically in a context-diverse sample. The first dimension we focus on, mosque attendance, captures communal religious practices (Stark and Glock, 1968; Cornwall et al., 1986). Attending mosques differs from feelings of identification and individual prayer because it is a social affair, opening the door to group processes including social pressures to adjust to group norms and social sanctions when failing to do so.

Second, identification—also termed “belonging” or “devotion”—captures the affective beliefs or feelings dimension of religion (Cornwall et al., 1986). Counter to attending mosques, personal identifications do not entail contact with others who make you change your values to fit into a (conservative) community. As such, identification has been linked to gender egalitarianism in Muslim-majority contexts (Glas et al., 2019), but it remains unclear how Muslim identifications function in Western Europe, because they do not merely signify an attachment to a particular religion but also to a minority group with highly politicized boundaries (Duderija, 2007b; Fleischmann et al., 2011; Phalet et al., 2013).

Finally, prayer outside of mosques probably functions differently yet again, because it captures a religious practice that is in principle observable by others but, unlike mosque attendance, is not a group ritual (Stark and Glock, 1968; Cornwall et al., 1986). Being an individual practice in that sense, prayer could reflect both orthopraxy in upholding the salat pillar of Islam, as well as solitary moments of reflection on the meanings of Islam, rendering its effects on support for gender equality unclear.

All this means that mosque attendance, identification, and prayer might shape support for gender equality in completely different ways, as has been shown by other public opinion studies (e.g., Glas et al., 2018; Beller et al., 2021). This also means that, rather than one patriarchal interpretation of Islam to which all Muslims adhere, religiosities and their meanings are multiple. Indeed, public opinion works have shown that the ways Muslims connect their religiosity to gender values differ across groups and contexts (e.g., Jansen, 2004; Rinaldo, 2014; Glas et al., 2019; Glas and Alexander, 2020; Van Klingeren and Spierings, 2020). Therefore, any blanket conclusion that Islam is one unified force that only blocks emancipation seems unfounded or at least a simplification of reality, giving rise to the questions of what aspects of religiosity help versus hinder support for gender equality—and for whom and when.

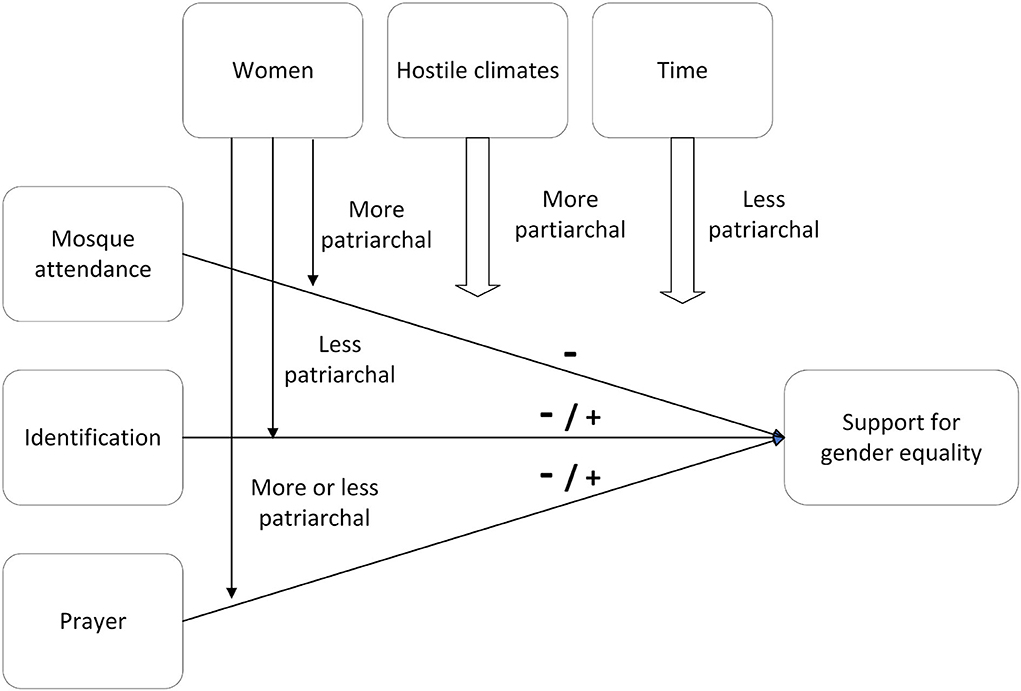

This section provides our theoretical answer to those questions. First, we argue that mosque attendance, feelings of religious belonging, and individual prayer are likely to shape Muslims' support for gender equality in the public sphere via partly separate and gendered mechanisms. Thereafter, we propose that the impacts of these dimensions of religiosity are context-dependent, and we focus on two opposing societal trends: increasing hostility toward Muslims in Western European countries (Roggeband and Verloo, 2007; Fleischmann et al., 2011) and the emergence of more individualized, postmodern interpretations of Islam over time (Kaya, 2010; Cesari, 2014). An overview of our expectations can be found in Figure 1 at the end of this section.

Throughout our arguments, readers should keep in mind that we focus on support for gender equality in the public sphere in particular—again, due to cross-context data availability. We do not claim that our insights can be generalized further, as dominant religious interpretations differ for varying gender values, and religiosity has been shown to be more loosely connected to public-sphere equality than to other gender values, such as the division of domestic duties and sexual liberalization (Glas, 2022b).

Mosques are patriarchal sites, but especially for women

Following the insights of a host of public opinion studies (e.g., Röder, 2014; Maliepaard and Alba, 2016; Glas et al., 2018), we expect that frequent mosque attendance generally curbs Muslim minorities' support for gender equality in the public sphere, for two reasons. First, when Muslims frequent mosques, they are exposed time and again to religious services that tend to be relatively conservative on women's role in the public sphere compared to views communicated in society at large (Baker et al., 2013). Those messages reinforce lower support for public-sphere gender equality when they are internalized. The authoritative status of imams makes questioning their conservative religious views difficult and believing what is shared in mosques more likely, catalyzing internalizations (Al-Hibri, 1982; Glas et al., 2019). Second, among Muslim minorities, frequent mosque attendance implies stronger integration into the conservative part of Muslim communities; because norms converge in groups via social pressures and sanctions, this would further hamper support for gender equality (Guveli et al., 2016; Beller et al., 2021; Röder and Spierings, 2022). This leads us to our general hypothesis that more frequent mosque attendance reduces support for public-sphere gender equality (hypothesis 1a).

At the same time, mosque attendance is highly gendered, as dominant religious interpretations stipulate that men should attend mosques frequently—at least for Friday prayers—whereas women are free to choose where to pray and thus face lower social pressures to attend mosques (Scheible and Fleischmann, 2013; Nyhagen, 2019). Qualitative studies have shown that women forego praying at mosques because they object to the genderedness of mosques, both in practical terms—such as the poor state of women's spaces and imams' lack of knowledge pertaining to women—and fundamentally—such as objections to gender segregation at mosques and not feeling included as an equal (Shannahan, 2014; Nyhagen, 2019; Ghafournia, 2020). This implies that women's self-selection for mosque attendance might be partly based on their gender attitudes, which is the first reason to expect gender differences.

Additionally, both of the mechanisms that underlie mosque attendance's patriarchal effects—internalizations of conservative sermons and norm convergence in conservative, mosque-going groups—are expected to feature more strongly among women. Qualitative studies have shown that the women who do choose to frequent mosques tend to do so not only for spiritual reasons but also because they actively seek out the religious knowledge of imams and community engagement (Ghafournia, 2020). Therefore, we expect that especially women internalize imams' patriarchal religious interpretations and comply with the norms of the conservative religious community, which is in line with the findings of several public opinion studies (Glas et al., 2018, 2019; Van Klingeren and Spierings, 2020). We thus formulate the expectation that more frequent mosque attendance is more strongly negatively related to public-sphere gender equality among women than among men (hypothesis 1b).

Identifying with faith vs. a community

The second aspect of Islamic religiosity we disentangle—feelings of religious identification—have been linked to both conservative and progressive outcomes. Some studies report that stronger identification decreases progressive values (e.g., Kogan and Weißmann, 2020), whereas other studies find nil-effects (Glas et al., 2018), and yet others report identifications to increase support for gender equality (Glas et al., 2019). To resolve this paradox, we propose that religious identifications set several processes in motion, some of them are more feminist, some are more patriarchal, and gendered processes might provide a first explanation of which gets the upper hand—another might flow from the context, as we will discuss further down below.

Building on insights from the sociology of religion and quantitative studies on Muslim-majority contexts, we expect that strong religious identifications have a feminist side. Sociologists of religion have argued that those who feel strongly attached to their religion are more likely to particularly take the main messages of their religion seriously, which include altruism, benevolence, and fairness, rather than just dogmatic rules (Saroglou et al., 2004; Bloom et al., 2015). For instance, dominant interpretations of Islam emphasize the importance of charity (zakat) and argue that judging people is up to Allah, not regular folk (El Fadl, 2001). This focus on benevolence among the strongly religiously identified, in turn, is expected to cause them to oppose discrimination, inequality, and intolerance (Spierings, 2019), which could explain why strongly identified Muslims have been reported to support gender equality more (Glas et al., 2019). This leads us to expect that stronger religious identifications increase support for public-sphere gender equality (hypothesis 2a).

Nevertheless, these arguments are mainly built on contexts where Muslims are the dominant majority and Islam is the predominant thus normalized faith. However, in Western European countries, strongly identifying with one's Muslim identity does not only signify an attachment to a faith pur sang but also an attachment to the Muslim-minority community (Duderija, 2007b; Fleischmann et al., 2011; Phalet et al., 2013). This in turn implies a stronger orientation toward the community's (imagined) values, which have been constructed to include traditional gender roles (Güngör et al., 2013; Glas, 2021). Considering religious belonging from a minority perspective thus leads us to the opposite expectation that stronger religious identifications decrease support for public-sphere gender equality (hypothesis 2b).

The question now becomes: for who does religious belonging mainly function as an attachment to the general, benevolent tenets of Islam, and for whom does turning away from liberal values constructed as Western take the upper hand? We argue a gender perspective might provide some answers. First, we expect women to relate the main tenets of their religion more strongly to benevolence than men because religious socialization and religious interpretations are gendered (Duderija, 2007a; Rinaldo, 2014). Women's socialization in general tends to underscore caregiving, compassion, and empathy more than men's, and religious socialization is no different (Glas et al., 2018). Therefore, strongly religiously identified women are expected to emphasize benevolence in particular as one of the main tenets of their religion, which implies that the feminist effects of religious belonging might be stronger among women and weaker among men.

Second, how the linkage between religious identification and stronger attachment to the Muslim-minority community's values plays out, is wholly dependent on what those values are imagined to be. Men are probably more likely to unquestioningly accept traditional roles for women, as they might believe they benefit from traditionalism and do not perceive the harms. Women, however, are expected to more actively question what restricting their activities in the public sphere has to do with an Islamic identity, as a plethora of qualitative studies has shown that women actively search for and apply feminist interpretations to their religion (e.g., Read and Bartkowski, 2000; Ramji, 2007; Rinaldo, 2014). Altogether, this leads us to expect that the patriarchal effects of religious belonging are stronger for men, which is in line with the findings of other public opinion studies (Scheible and Fleischmann, 2013; Glas et al., 2018): stronger religious identifications decrease support for public-sphere gender equality, especially among men (hypothesis 2c).

The duality of individual prayer

The final dimension of religiosity we focus on is prayer outside of mosques. Like religious belonging, we argue that individual prayer could theoretically have both patriarchal and feminist effects—and gendered (and context-dependent) forces might tip the scales in favor of one or the other.

Frequent prayer could have patriarchal effects if it signifies orthopraxy—living orthodox religious interpretations through practices. In this view, Muslims who pray more often do so in part to comply with conservative interpretations of religious prescriptions—particularly salat, praying five times a day. This implies that often-praying Muslims are more likely to subscribe to conservative religious interpretations, which include opposing women's roles in the public sphere (Ji and Ibrahim, 2007; Van Klingeren and Spierings, 2020). Prayer as orthopraxy thus leads us to expect that: Muslims who pray more frequently support public-sphere gender equality less (hypothesis 3a).

At the same time, we should again note that conservative interpretations of religious prescriptions are gendered. For men, conservative prescriptions are geared toward praying together at mosques more than praying individually (Mirza, 2016; Nyhagen, 2019). This means that individual prayer might denote orthopraxy not so much among men as among women. This in turn implies that the patriarchal effects of prayer-as-orthopraxy feature more strongly among women: more frequent individual prayer reduces support for public-sphere gender equality, especially among women (hypothesis 3b).

However, prayer outside of mosques has also been linked to thoughtfully engaging with Islam rather than salat (Jeldtoft, 2011; Cesari, 2014). In that interpretation, prayer denotes reflecting on what Islam means (ijtihad) through personal conversations with Allah instead of only adopting the religious interpretations of the Islamic establishment (Duderija, 2007b; Kaya, 2010). Muslims would pray regularly not to fit conservative interpretations of religious prescriptions but rather to think about and even question those very prescriptions through personal conservations with Allah (Jeldtoft, 2011). If individual prayer indeed signals a reflective process that entails questioning the conservative religious establishment, we would expect prayer to have feminist effects: Muslims who pray more frequently support public-sphere gender equality more (hypothesis 3c).

The feminist effects of prayer might also be gendered, for two reasons. First, women probably utilize prayer for reflective moments more often than men, as qualitative studies have shown how varied women engage with their religion and its establishment thoughtfully and critically (e.g., Read and Bartkowski, 2000; Ramji, 2007; Rinaldo, 2014). Second, even among those who use prayer reflectively, women are expected to be more likely to reflect on the gender implications of their religion in particular (Glas et al., 2018). Men are expected to be less likely to reflect on dominant religious interpretations of gender roles rather than other topics because their privileged status makes gender roles a less visible and pressing everyday concern to them. We thus arrive at the opposite expectation: more frequent individual prayer increases support for public-sphere gender equality, especially among women (hypothesis 3d).

Hostile hosts engender reactionary religiosity

Up to now, we have deduced arguments built on the multiplicity of religiosity and its gendered meanings, but this only captures the first part of our theoretical starting point. We now move on to the next part, which is that the meanings that are attached to religiosity's manifestations are not unchangeable and fixed but rather arise from context-dependent meaning-giving processes.

We start with the, at times, hostile climates toward Muslims in Western European host countries (Roggeband and Verloo, 2007; Fleischmann et al., 2011). Hostile climates can emanate from a range of actors, including political authorities, the judiciary, the media, and the general public, can be both formal and informal, and can be conscious exclusions as well as subconscious biases (Glas, 2022a). Hostile climates thus range from, for instance, laws prohibiting veiling in public spaces (formal, judiciary, and conscious) to negative characterizations of Muslims by government officials (informal, politicians, and (un)conscious) and anti-Muslim biases of the public (informal, public, and unconscious). The general undercurrent binding this broad spectrum together is that all hostilities construct the Muslim/non-Muslim divide as a bright boundary, whereby both groups are homogenized, differences within them overlooked and between them emphasized, and Muslims are constructed as the subordinate group. Because our theorization is already complex and as little work has been done on how these climates affect minorities' gender values at all (cf. Glas, 2022a; Röder and Spierings, 2022), we do not focus theoretically on how varying manifestations of hostility might have different effects. We instead empirically study a range of hostilities (formal and informal ones enacted by politics, judiciary, and the public, although mostly focused on conscious exclusions) and assess whether and how their effects differ empirically.

We expect hostile climates to affect the meanings Muslims attach to their religiosity through two mechanisms. The first is derived from the core thesis of social identity theory (SIT) that people strive for positive social identities—in our case, a positively-evaluated Muslim community (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). It is important to remember here that “social identity” does not merely denote a social category but also the significance of that category to people's self-concepts. Not all Muslims have some “Islamic social identity.” Rather, Muslims who are more strongly embedded in the community—through frequent mosque attendance—or more strongly attached to the community—through belonging—are expected to view Islam as more core to their social identity, whereas it is unclear that prayer, as an individual activity, similarly functions as an attachment to the Muslim community. As such, if societies are more hostile toward Muslims, Muslims who attend religious services more often and who identify as religious more strongly are expected to feel that their social identity is rejected1.

When social identities are met with hostility, SIT predicts that people employ coping strategies, one of which entails re-valuing the traits deemed negative by the dominant native majority as positive, thereby creating a positive social identity in the face of rejection (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Branscombe et al., 1999)2. As hostile European societies portray Muslims as foreign “others” based in part on their supposed lack of support for “the core Western value” of gender equality and their religion (Roggeband and Verloo, 2007; Yilmaz, 2015; Geurts and Van Klingeren, 2021), Muslims who frequent mosques and strongly identified Muslims are thus expected to re-assert the value of gender traditionalism in particular in hostile contexts (Phalet et al., 2013; Glas, 2021, 2022a; Röder and Spierings, 2022). Especially qualitative studies have shown how Muslims do just that, for instance arguing against the worth of sexual liberalization by slut-shaming non-migrant women who “sleep around” “as if they have no values” (Le Espiritu, 2001); see also (Ajrouch, 2004; Giuliani et al., 2017; Glas, 2021). Although quantitative studies are limited in this respect, Röder and Spierings (2022) have shown that discrimination does indeed strengthen the link between religiosity and hostility toward homosexuality. This all leads us to expect that hostile contexts beget reactionary religiosity especially among strongly identified Muslims and those who often attend mosque services.

The second mechanism that underpins the conditioning impact of hostile climates concerns the intra-community dynamics of external conflicts (Coser, 1956). When communities face an external threat, they are expected to close ranks, as it were, whereby community norms are sharpened and pressures to stick to them grow. This is especially likely to occur when a “subordinated” community (e.g., Muslims) is threatened by a dominant one (e.g., “native” whites), because subordinate communities lack the power to challenge the threat in other ways. In Western European societies that are more hostile toward them, Muslim citizens are thus expected to create more of a united front against the antagonist (cf. Fleischmann et al., 2011; Guveli et al., 2016; Beller et al., 2021). Consequently, in more hostile contexts, Muslims are expected to close opportunities for intra-community discussions and instead create one front with one set of values to which all members are expected to stick—and sanction transgressions severely (Coser, 1956).

In turn, closing ranks in hostile host societies is expected to strengthen the patriarchal impact of mosque attendance, religious belonging, and individual prayer in similar ways but for different reasons. First, we expect conservative norm convergence in mosque-going communities to be stronger in more hostile contexts. In those contexts, pressures to stick to community norms mount, and transgressing norms are more harshly sanctioned (Guveli et al., 2016; Beller et al., 2021; Röder and Spierings, 2022). Second, because hostile contexts signal that Muslims are necessarily “other” to the Western European community and its values (Roggeband and Verloo, 2007; Yilmaz, 2015), we expect strongly identified Muslims to close ranks by turning away from the values portrayed as fundamentally European, including public-sphere gender equality, in more hostile contexts (Verkuyten and Yildiz, 2007; Verkuyten and Martinovic, 2012; Eskelinen and Verkuyten, 2020; Glas, 2022a). Finally, we expect that the feminist potential of prayer is curbed in hostile contexts because reflecting on community norms and questioning dominant conservative religious identifications is discouraged when communities close ranks (Duderija, 2007b; Jeldtoft, 2011; Cesari, 2014). Altogether, we expect that: In more hostile European countries, more frequent mosque attendance (hypothesis 4a), stronger religious identifications (hypothesis 4b), and more frequent individual prayer (hypothesis 4c) are more strongly related to opposition to public-sphere gender equality.

Again, these relations might also be gendered, and we might tentatively expect that hostile contexts engender such reactionary religious interpretations among women especially. The reason is that women are expected to be the ones who utilized the space to deviate from patriarchal religious interpretations in less hostile societies in the first place, as qualitative studies have shown (Read and Bartkowski, 2000; Ramji, 2007; Rinaldo, 2014). Therefore, especially women's progressive religious interpretations are expected to be restricted in more hostile host societies. Additionally, women are expected to be socially sanctioned more harshly than men when they transgress community norms because women are in less powerful positions and tend to be made into symbols of the community (Le Espiritu, 2001; Ajrouch, 2004; Giuliani et al., 2017; Glas, 2021). Consequently, in more hostile contexts that more strictly uphold community norms, especially women's transgressions might be sanctioned and sanctioned more harshly, leading them to stick to reactive community norms more so than men. Altogether, hostile hosts might condition the relations between religiosity and gender values in gendered ways, which we shall address empirically.

Emerging European Islam drives decoupling

Lastly, Muslims might also respond to increasingly hostile societies by adjusting how they live their religion over the years (Phalet et al., 2013). Qualitative migration scholars have argued just that and proposed that, in the face of narratives that Islam would necessarily oppose gender equality, Muslims have been increasingly individually reflecting on what Islam means to them; an individualized, postmodern European Islam has been emerging over the years (Duderija, 2007b; Kaya, 2010; Cesari, 2014). This individualized Islam has, in Jeldtoft's (2011, p. 1137) words, “a strong focus on autonomy and the personal experience as opposed to religious authority and fixed traditions”—it is “‘un-churched', privatized and also quite pluralistic and inclusive.” Likewise, Duderija (2007a) argues that in recent years, Muslims would have started to question the conservative interpretations of religious authorities as imams more regularly, arguing that those interpretations are too rigid because they overlook the importance of the migration context. The religious interpretations of the establishment that deny women equal access to the public sphere would increasingly be viewed as “cultural” rather than “religious”—perhaps suited to stayers in, for instance, Pakistan but not to Muslims in Europe (Predelli, 2004; Naber, 2005; Ramji, 2007). These arguments from qualitative studies thus lead us to expect that, over the years, European Muslims' religious interpretations have been changing in a liberal direction, which has also been found by several quantitative studies (Röder and Mühlau, 2014; Phalet et al., 2018).

If an individualized, European Islam has indeed been gaining ground, Islamic religiosities are expected to be increasingly decoupled from gender values over the years (Röder, 2014; Van Klingeren and Spierings, 2020; Glas, 2022b; Röder and Spierings, 2022). What is proclaimed in religious services would be detached from life outside of mosques, as imams' conservative religious interpretations are increasingly reflected upon rather than indiscriminately adopted (Duderija, 2007a). Strongly identifying as Muslim would not imply unquestioningly adopting the imagined values of the Muslim community, but rather deliberating what Islam means to you individually (see also Röder and Mühlau, 2014; Spierings, 2015; Phalet et al., 2018). Fewer and fewer Muslims would use prayer as orthopraxy as religious prescriptions are questioned, and, instead, prayer would be increasingly utilized as a moment to reflect on religious meanings. Altogether, this leads us to expect that Islamic religiosities have been increasingly decoupled from traditional gender values over time: In more recent years, more frequent mosque attendance (hypothesis 5a), stronger religious identifications (hypothesis 5b), and more frequent individual prayer (hypothesis 5c) are more weakly related to opposition to public-sphere gender equality.

Decoupling might also be gendered, and we might tentatively expect that especially women have increasingly decoupled their religion from opposition to gender equality over time. The reasons are that women tend to use spaces for religious reinterpretation more and in more feminist ways, for instance, because they experience the sting of patriarchal religious interpretations more personally in their daily lives (Read and Bartkowski, 2000; Ramji, 2007; Rinaldo, 2014; Glas et al., 2018; Van Klingeren and Spierings, 2020). Consequently, if a more progressive European Islam has been emerging, women are likely to be the driving force behind it—at least in the case of progressive religious reinterpretations of gender relations. Indeed, existing work suggests that women more so than men have increasingly reinterpreted their religion, moving away from opposition to gender equality (Röder and Spierings, 2022). Therefore, we will also empirically address whether changes in the relations between religiosity and gender values are gendered.

Methods

Synchronizing survey sources

Cross-national studies into minorities' values and behaviors are limited by the data available. A major obstacle is that migrant-specific datasets tend to cover only a few contexts, while cross-national datasets tend to include a rather limited number of migrant-background citizens. To make more general claims (Spierings, 2016) and because we are interested in contextual effects (concerning hostility), this obstacle needs to be overcome.

This study uses a pooled dataset that combines all Muslim respondents from multiple (general and migrant-specific) cross-national surveys. Evidently, it would have been more ideal to have data from an annual migrant-specific survey in all Western European countries, for a time span of over 20 years, with representative migrant-background samples. Those data do not exist and will not exist soon. By pooling cross-national surveys and adjusting for measurement differences as other studies on similar topics have done (Spierings 2018, Spierings, 2019) and as we describe below and in Appendices A–C, we can create a database with over 10,000 potential Muslim respondents from all Western European countries, covering all years since 2000.

We selected the European Social Survey, European Values Study, World Values Survey, 2,000 Families data, and EURISLAM, because these surveys all include at least six Western European countries—in order to be able to build on similar measurements across countries—and measurements of our core concepts (gender attitudes, mosque attendance, identification, and prayer). After selection of self-identified Muslims (based on denomination) and valid scores on core variables, we were left with a dataset with no fewer than 9,461 Muslim respondents in 16 countries, covering a time span of 12 years. Due to our standardization procedures to harmonize the data discussed below, we cannot present descriptive figures on the current state of affairs but we can compare respondents and study the impact of Islamic religiosity in new ways, our main focus. Nevertheless, to further establish the robustness of our pooled results, we have also estimated their effects per survey source (Appendix D1, and split by gender in Appendix D2), as will be discussed as part of the results section.

Support for gender equality in the public sphere

To measure gender equality, we first selected items that theoretically fit support for gender equality in the public sphere. We do so as public-sphere equality is (a) covered by more surveys, (b) the predominant focus in the existing literature, and (c) connected to Islamic religiosity differently than other gender values (see Glas, 2022b; Glas et al., 2019). After conceptual reflections and estimating factor analyses (details in Appendix B), we concluded five sub-dimensions fit together well and measure our concept of interest: support for (i) female political leadership and (ii) business leadership, (iii) equal importance of higher education for girls and boys, and (iv) women's right to a job and (v) not considering men the sole proper breadwinners. Each of these relates to women being present in the public sphere and taking positions of power.

Evidently, these five different elements do vary to the degree they are considered controversial religiously or simply how widespread their support is (Glas, 2022b). To create an index valid across surveys, we re-categorized the answers if questions were the same but answer categories differed. Then, pivotally, we standardized (z-scored: mean = 0; SD = 1) each item separately, which takes into account how much support there is for a certain form of public equality (akin to β-values in regression models). If a certain form of equality is supported less on average, answering positively on this item gives respondents a relatively higher score. Of these resulting standardized variables, we took the mean per respondent (based on the available scores), which provides us with the degree of support for gender equality in the public sphere of each respondent relative to the others.

Islamic religiosity

Mosque attendance is asked across surveys with questions with at their core “How often do you attend religious services?” and four to seven answer options that range from never to daily. Across surveys we could regroup the answers to capture 0 “never to less than yearly,” 1 “yearly to monthly,” 2 “weekly,” and 3 “more than weekly” (details in Appendix C).

For respondents' religious identification, we selected items that are part of the subdimension of affective religiosity (see Stark and Glock, 1968; Cornwall et al., 1986; Glas et al., 2018). In each survey source, at least one indicator for one of the following three question types was present: the degree to which one sees oneself as Muslim, considers themselves religious, and the importance they attach to God or religion in their lives (see Appendix C). In existing studies, these three have been combined to measure identification among Muslim respondents and they have been empirically shown to tap one underlying concept (Glas et al., 2018; Spierings, 2019). Of the five available items across surveys, two are available together in multiple WVS and EVS rounds, each of a different question type: religiousness and importance of God. Despite one having only three answering options, these two correlate well over 0.4 in our data (p < 0.001), indicating they go together. Building on the procedure used in the studies mentioned above, we standardized each item, and then averaged the available standardized scores, which ascribes each respondent a score on religious identification relative to the other respondents.

Individual prayer was measured by questions that share a stem reading “How often do you pray?”. Three out of five surveys explicitly refer to praying apart from or outside of religious services in the question stem and a fourth makes this distinction in the answering options (WVS; details in Appendix C). Only the EurIslam questionnaire is not that explicit. The data suggest the risk of bias toward individual praying is minimal, as over 90 percent of respondents who say to pray daily or more frequently do not attend mosque daily, while of those attending mosque daily over 90 percent does pray daily. Especially considering that we also add mosque attendance (or: social prayer) to our models, in the EurIslam data praying during services is at the best a very small part of the reported prayer, hardly influencing the answers given the answering categories. Across surveys, we could regroup the answers categories, ranging from five to eight options, into four options across surveys: 0 “(practically) never”, 1 “less than weekly,” 2 “at least weekly,” and 3 “daily or more often.”

Context-level independent variables

We measure “hostility” in three different ways to capture different manifestations of hostile climates (formal and informal, emanating from the public, politicians, and the judiciary) based on exploratory factor analyses on 10 macro-level items (details in Appendix H). First, hostile public attitudes are based on aggregated scores from the European Social Survey's population samples covering a range of anti-migrant attitudes (European Social Survey a., 2016; European Social Survey b., 2016; European Social Survey c., 2018). Second, the presence of populist radical right-wing parties is based on publicly available national parliamentary election results. Finally, political and social harassment is based on a combination of the Global Restrictions on Religion Data coded by the Pew Research Center (Grim, 2019) and a newly created indicator. From the GRRD, we use two indicators: one on the social harassment of Islam (e.g., physical coercion or negative public comments by members of the public) and one on the political harassment of Islam (e.g., physical coercion or negative public comments by government officials). The third element in this index is a newly coded indicator regarding veil bans in national law, which provides a gender-specific form of legal harassment. Across these indices, a higher score indicates a higher degree of hostility.

Note that all hostilities are coded at the country (-year) level. Most of the manifestations of hostile climates we consider only pertain to countries (e.g., national laws, governments). However, hostile public attitudes occur at the subnational level as well. Such regional hostilities probably have stronger effects on the public than national ones, assuming that people are more likely to perceive hostilities closer to them (Spierings, 2015). Unfortunately, aggregations at the subnational level were impossible because the regional locations of respondents are not always known. Still, if anything, this might only lead to an underestimation of some of our effects.

We test whether the impact of Islamic religiosity has changed over the years (hypothesis 5) by including year as a contextual interaction factor. In line with our theoretical reasoning, the year is included as a linear variable, whereby we set the first year available to 0 and count onward, based on the year of the interview. To avoid type-2 errors and following our theoretical logic of time tapping societal change, we include the year as a contextual variable.

Control variables

Age was measured in years. We also included whether the respondent was born in the country of destination, in another country, or whether this is unknown. For respondents' education level, we distinguished between no education, primary education, secondary education, and tertiary education, and again unknown. We use dummy variables with a separate category for respondents with missing values on a specific variable in order not to lose cases, particularly so because missing values on for instance education are hardly ever non-selective. On people's main activity (or “employment status”), we make a distinction between being employed (making a considerable number of hours), being in education, and being neither. Lastly, relationship status was measured in the categories married/partnered, never married, and others (including divorcees and widows)3.

Model configuration

Given our data include individuals from various countries and years, we estimate three-level models: individuals nested in country-years nested in countries, with random intercepts at both higher levels. To control for differences between surveys and years, we instrumentally include dummies for the different source surveys (and we include a linear year variable to test hypothesis 5). This modeling strategy assures that macro-level differences between countries, years, and surveys (including the presence of specific items) in terms of support for gender equality are filtered out. Further details on model configuration are provided in Appendix E. We have also estimated our models per survey source (see Appendix D1) and discuss divergent results in the main text.

With respect to assessing the different effects of religiosity between men and women, we estimate split models throughout our study to avoid hard-to-interpret three-way interactions. However, while they show if certain effects are for instance statistically significant for men but not for women, these models do not include a formal test of whether this difference itself is statistically significant. To assess this we also specified a model including interaction terms with gender (see Appendix G), which we take into account when discussing our results in the text below.

Results

Gendering Islamic religiosities

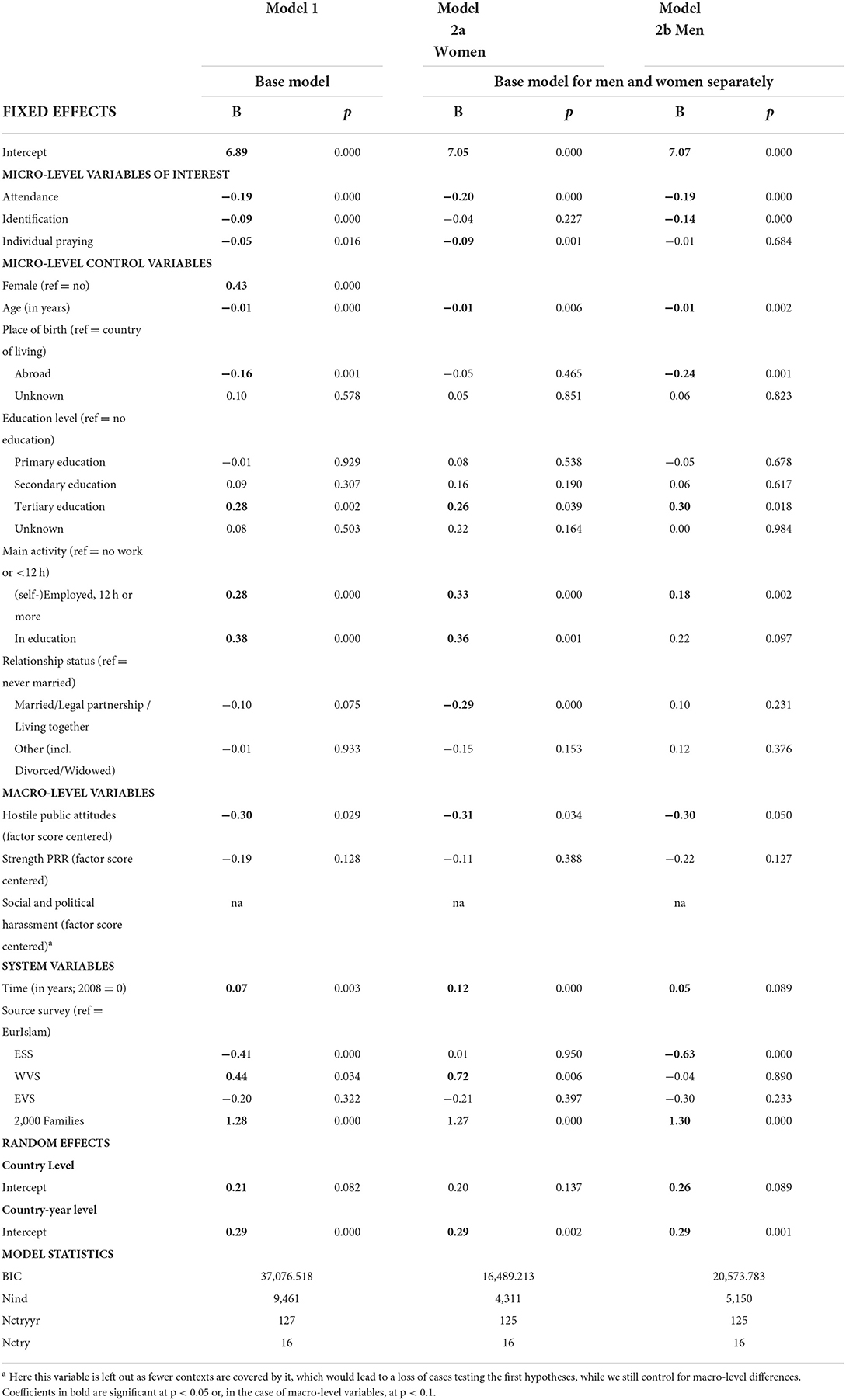

Although later analyses tell a more complex story, Model 1 in Table 1 shows that Islamic religiosity reduces support for gender equality in the public sphere. This model is most akin to standard studies on Islamic religiosity and gender equality, showing averages across two genders and different Western European contexts (e.g., Diehl et al., 2009; Norris and Inglehart, 2012). Here, we find that Muslims who attend mosques more often, who identify as more religious, and who pray more often on average support public-sphere gender equality significantly less than others.

Table 1. Multilevel regression models estimating the impact of Islamic religiosity on support for gender equality in the public sphere among self-identified Muslim citizens in Western Europe (2008–2019).

However, as the results in Appendix D1 show, there as some important nuances. The effect of attendance is most robust across survey sources, whereas that of prayer is present in the total sample, but picked up far less clearly by the separate samples4. When we separate different gender values (see Appendix F), we similarly find that attendance has the most general negative and significant effect, whereas identification and prayer show significant negative effects and nil-effects5. We would thus conclude on the overall average effects that Islamic religiosity is always a barrier to integration and emancipation, as others have done before, if we stopped here and had not studied Islam with attention to gender or context.

However, estimating our models for men and women separately already lays bare several divergent patterns (see Models 2a and 2b in Table 1; full interaction model in Appendix G; per-gender per-survey source models in Appendix D2). This underscores the importance of nuance in studying the effects of Islamic religiosities. Our only dimension of religiosity significantly reduces support for gender equality in the public sphere among both men and women in mosque attendance. Still, even the negative effect of mosque attendance is found per gender across surveys and this cannot simply be accounted for pointing out the reduced statistical power (see Appendix D2)6. Therefore, we accept hypothesis 1a and reject the gendered effect of mosque attendance specified in hypothesis 1b. Rather than Islam writ large, these results imply that the barrier to support for gender equality among Muslim minorities in Western Europe is frequent mosque attendance in particular (in line with Guveli et al., 2016; Glas et al., 2019; Beller et al., 2021).

Neither religious identification nor individual prayer is found to decrease support for gender equality in the public sphere among both men and women (especially when survey differences are considered, see Appendix D2)7. First, men who more strongly identify as religious support public-sphere gender equality significantly less, but women do not. These results falsify hypotheses 2a and 2b, which argued identification's effects would be similar among men and women, in favor of hypothesis 2c, which proposed a gendered effect of identification. These results might indicate that religious identification indeed partly reflects the attachment to the Muslim community and its imagined values in Western Europe, whereby men accept that those values include traditional gender roles, but women resist that notion. This would lead more strongly identified men but not more strongly identified women to oppose gender equality (Duderija, 2007b; Fleischmann et al., 2011; Phalet et al., 2013).

Our results show that the effects of individual prayer are also gendered, but the other way around. Although the interaction between praying and gender is only significant at p<0.06 in cross-gender models (see Appendix G), our results show that, among women, praying significantly reduces support for public-sphere gender equality, while, among men, individual prayer has no significant effect at all. These results support hypothesis 3b and falsify hypotheses 3a, 3c, and 3d. Individual prayer might reflect orthopraxy among women, so that often-praying women are more orthodox and conservative on gender matters as well, but not among men, as orthodox men probably believe they are required to pray not individually but in mosques (Mirza, 2016; Nyhagen, 2019).

Islamic religiosities in hostile environments

Moving on to the importance of environments, starting with hostility, our results generally show that Muslims support public-sphere gender equality less in more hostile European countries, particularly in terms of hostile public attitudes (Models 1 and 2 in Table 1)8. This is in line with general arguments from social identity theory and the dynamics of external conflict that communities retreat when under threat (in line with Glas, 2022a; Röder and Spierings, 2022). Populist signals that Muslims do not belong in Western Europe because Islam opposes women's empowerment and thus indeed seem to backlashes in support for gender equality among Muslims (Roggeband and Verloo, 2007; Mayer et al., 2014; Yilmaz, 2015; Spierings and Glas, 2021).

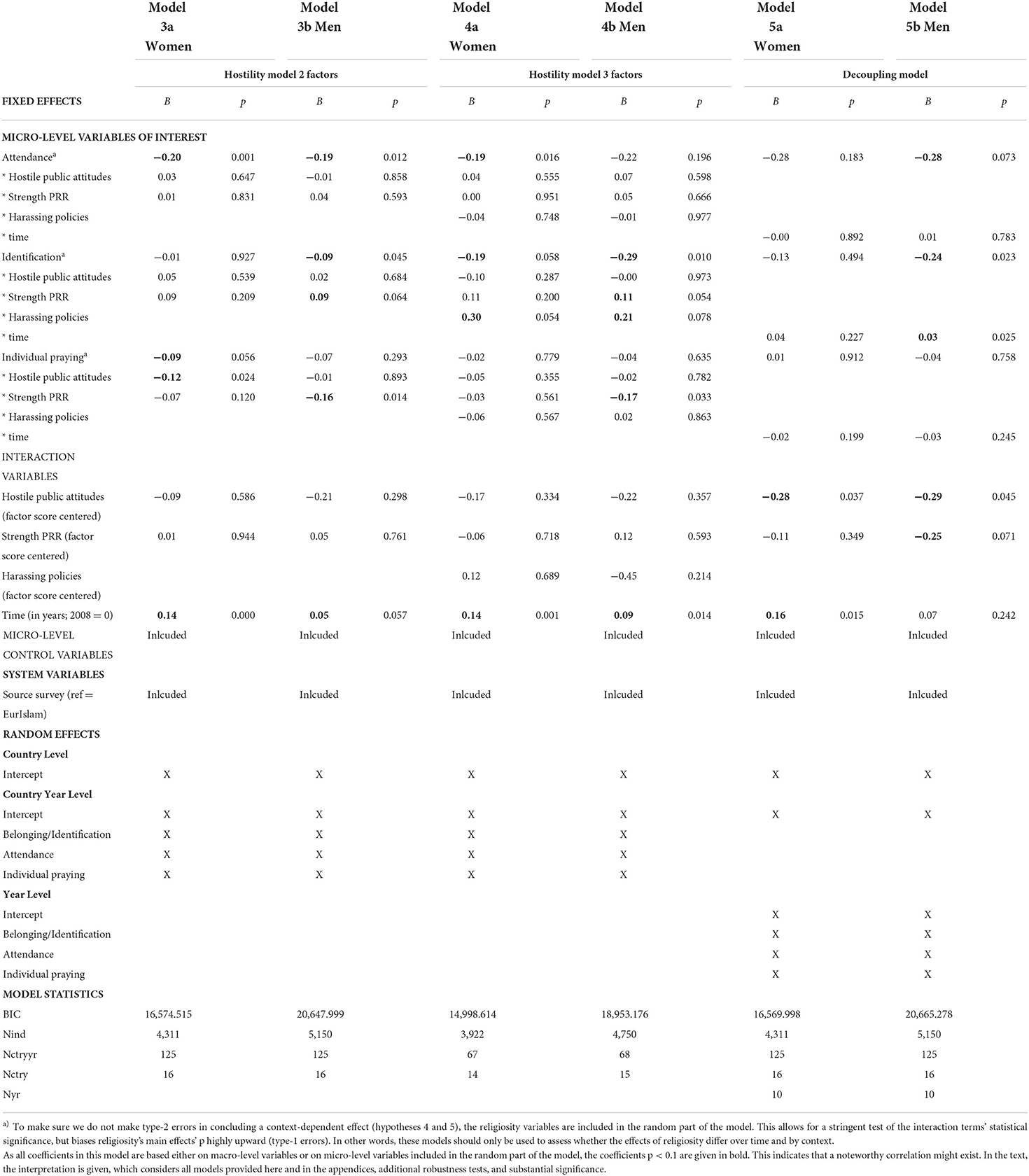

The question at hand now is whether hostile environments also cause Muslims to interpret their religion differently and in more reactionary, patriarchal ways. Table 2 shows models that test whether Islamic religiosity's impact is context-dependent. In general, we do find some indications that Muslims live their religion differently in more hostile contexts, but definitely not in every case and not always in the expected direction.

Table 2. Summarized multilevel regression models estimating the context-dependent impact of Islamic religiosity on support for gender equality in the public sphere among self-identified Muslim citizens in Western Europe (2008–2019).

First, the impact of mosque attendance is not significantly altered—in either direction—in more hostile European contexts (see Models 3 and 4). These results falsify hypothesis 4a; it seems that Muslims who are exposed more frequently to generally conservative sermons internalize these messages, regardless of gender or the hostility of the European context (countering Glas et al., 2018; Van Klingeren and Spierings, 2020; Röder and Spierings, 2022; more in line with Scheible and Fleischmann, 2013). Overall, the negative impact of mosque attendance on support for public-sphere gender equality seems pretty robust across genders, outcomes, and contexts.

The impact of religious identification, on the other hand, does seem to differ from the hostility of the European context, but in the direction opposite to our expectations (see Models 3 and 4). Generally, our results provide several indications that in more hostile contexts, religious identification's patriarchal effects are weaker rather than stronger. These results are not univocal and less robust, but no indications of a strengthening effect are found, clearly falsifying hypothesis 4b. As our results tend to reach marginal levels of statistical significance which we deem non-trivial given the number of higher-level units, and they do consistently point in the same direction, we tentatively conclude that contexts with more hostile institutions, but not publics, weaken the negative relationship between religious identification and support for public-sphere gender equality9. If so, we suggest this might indicate that when Western European Muslims encounter hostile environments that question the gender attitudes of their communities, they do not respond by re-appropriating the value of gender traditionalism. Rather, they might re-imagine their community values in a more liberal direction, as we shall return to in the conclusion (Verkuyten and Reijerse, 2008; Geurts and Van Klingeren, 2021; Dickey et al., 2022).

Turning to our third dimension of religiosity, our results indicate that prayer's patriarchal effects might strengthen in more hostile European contexts, as expected (see Models 3 and 4). In contexts with stronger populist right-wing parties, the negative impact of prayer on support for public-sphere gender equality intensifies among men, in accordance with hypothesis 4c. However, the same is not found for harassing policies, while for hostile public attitudes we find one such indication among women (and twice in Appendix G when estimated separately). So, we can only suggest that when they are met with hostility, some Muslims might respond by attaching more reactionary meanings to their prayer. Another possibility, to which we shall also return in the conclusion, is that hostile environments cause Muslims to pray less outside of services—especially those who would otherwise pray very often—for instance because Muslims fear being harassed if they pray at work. If those reductions in prayer in hostile contexts are stronger than the reductions in support for public-sphere gender equality, this would also cause the connection between prayer and opposition to gender equality to strengthen.

Overall, we do not find overwhelming support for the notion that hostile European contexts spur reactionary religiosity. But we also cannot report that hostile contexts do not affect the meanings Muslims attach to their religion (countering Röder and Spierings, 2022). Our results paint a complex picture, whereby religious identification and prayer are affected by some hostilities but not others, which sometimes beget more feminist effects of religiosity and sometimes more patriarchal ones. We return to this in the conclusion, because these results might actually feed into a broader understanding of how different dimensions of religiosity relate to support for gender equality.

Islamic religiosities over time

Finally turning to changes over time, our results show that European Muslims' support for public-sphere gender equality has increased over the years (see all models), which is in line with qualitative scholars' arguments on the emergence of an individualized and more progressive European Islam (Duderija, 2007b; Kaya, 2010; Cesari, 2014). At the same time, our results do not consistently show that Islamic religiosities have been increasingly decoupled from support for public-sphere gender equality (see Model 5 in Table 2), which refutes hypotheses 5a–c. While European Muslims have become more gender-egalitarian over the years, this does not seem to be due to them interpreting their religion in more feminist ways. Indeed, additional models provide indications that religious attendance, identification, and prayer have, on average, risen over time simultaneously.

Interestingly, we do find one relatively clear case of decoupling religiosity and gender attitudes, and it is among men. Men who more strongly identify as religious support gender equality less (see Model 2b in Table 1), but this effect has become significantly weaker over time (see Model 3b in Table 2). This implies that men are slowly starting to decouple religious identifications from gender values, as women have already done (see Model 2a in Table 1) (countering Röder, 2014; Van Klingeren and Spierings, 2020). Therefore, although these results do not support the claim that Muslims have started to decouple their religiosity writ large from their gender values over time, we do find that men are gradually starting to let go of connecting their religious identification to opposing gender equality.

Conclusion and discussion

Current Western European public debates fueled by right-wing populist sentiments argue that Muslims are hostile to gender equality due to Islam (Roggeband and Verloo, 2007; Yilmaz, 2015). While some dominant interpretations of Islam might currently be linked to hostility toward gender equality, such narratives simplify the matter and present Islam as one inherently patriarchal religion—views that are not questioned by the majority of quantitative studies, which show that Muslims, on average, support gender equality less than non-Muslims and attribute all differences to the patriarchal effects of Islamic religiosity (e.g., Diehl et al., 2009; Norris and Inglehart, 2012).

Diverging from this approach, this study addressed diversity among European Muslims, which allows us to consider that there is no one way to live Islam to which all Muslims adhere (Ginges et al., 2009; Beller et al., 2021; Glas and Spierings, 2021). Instead, we argue that Islamic religiosity is flexible: it consists of multiple dimensions, which, in turn, relate to gender values in different ways through meaning-giving processes that are gendered, subject to change, and dependent on contextual circumstances (Güngör et al., 2013; Phalet et al., 2013; Beek and Fleischmann, 2020; Kogan and Weißmann, 2020). Testing this framework using a pooled dataset that uniquely covers over 9,000 Muslims in 16 European countries between 2008 and 2019 and multilevel analyses, our results show that mosque attendance, religious identification, and individual prayer shape Muslims' support for public-sphere gender equality in far more complex ways than we expected—let alone any right-wing populist claim on one essential patriarchal Islam captures.

At the most general level, we believe that the intricate patterns in our results signify that mosque attendance, religious identification, and individual prayer reflect qualitatively different religiosities, which in turn react differently to gendered and contextual processes. First, mosque attendance is found to limit people's support for public-sphere gender equality, and, unexpectedly, its impact does not differ for men or women (countering Glas et al., 2018; Van Klingeren and Spierings, 2020), in more and less hostile contexts (in line with Röder and Spierings, 2022), or over time. These results imply that mosques remain patriarchal sites for all (Baker et al., 2013; Röder, 2014; Maliepaard and Alba, 2016; Glas et al., 2019; Nyhagen, 2019; Ghafournia, 2020), which might reflect that mosque-goers do not question the interpretations of religious authorities or fear rejections from conservative communities if they do. Altogether, the current study finds no support for arguments from qualitative scholars that European Muslims would increasingly question the conservative religious establishment (cf. Predelli, 2004; Duderija, 2007a,b; Kaya, 2010). Although Muslims have become more progressive over time, a more individualized and postmodern European Islam does not manifest itself through a changing relationship between visiting mosque services and support for public-sphere gender equality (cf. Cesari, 2014).

The strength of religious identification and prayer, on the other hand, are not necessarily barriers to Muslims' emancipation (Foner and Alba, 2008), but in different ways, so they do seem to reflect different religiosities (Stark and Glock, 1968; Cornwall et al., 1986). First, it seems that strong identifications capture attachment to the Muslim minority community and its imagined values, but these are viewed differently by men and women. Men might believe that their communities are built on gender complementarity whereas women resist that notion, which would explain why religious identifications only curb men's support for public-sphere gender equality but not women's (countering Kogan and Weißmann, 2020; Glas and Spierings, 2021; in line with Glas et al., 2018; Van Klingeren and Spierings, 2020).

On the other hand, we believe that prayer outside of mosques reflects orthopraxy. Women who pray more often might do so to live up to orthodox interpretations of religious prescriptions (i.e., salat) and consequently hold more conservative views on gender relations as well, as our results show. Orthodox Islam however expects men to pray at mosques rather than individually, which explains why we do not find any patriarchal effects of prayer among men (in line with Beller et al., 2021).

This line of reasoning would also explain why the effects of religious identification are weaker in more hostile contexts, whereas those of prayers are stronger, as our results tentatively indicate but we did not expect. The reason is that the imagined values of a community are changeable, but orthodox prescriptions are, by definition, unchangeable. Social identity scholars have argued that this changeability of group positions is pivotal to understanding how communities react to hostilities (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Branscombe et al., 1999; Verkuyten and Reijerse, 2008; see also Geurts and Van Klingeren, 2021; Dickey et al., 2022). If group positions are changeable, groups can change them when faced with hostile attacks. If they are not, groups have to dig in their heels. When met with hostilities, those who strongly identify with the Muslim community seem to re-imagine their community values to fit gender equality. Because orthodoxy leaves no such room for change, frequent prayers can only create positive group identities by doubling down and strengthening their opposition to gender equality. This would explain why our results simultaneously indicate a “digging in their heels” effect for individual prayer and a more egalitarian effect of identification in more hostile contexts.

Another reading of prayer's effects is that hostile environments might cause Muslims to pray less outside of services because they fear social sanctions of hostile non-Muslims. Although we cannot assess this directly, because there are currently no data available on whether prayer was private (non-visible to others) and what individuals believe that the purpose of their prayer is, prayer remains a visible practice. Because identifications are invisible feelings, it makes sense that similar reductions of religious identification's effects are not found in more hostile contexts. Although our results show support for gender equality also declines in more hostile environments, if reductions in prayer are stronger, this would also lead to intensifications in the relation between prayer and opposition to public-sphere gender equality.

Our findings on hostile contexts, however, are not robust. To our knowledge, this study is the first to include three aspects of hostile contexts (hostile public sentiments, populist right-wing parties, and harassing policies), and our results show that they do not all shape the relations between Islamic religiosities and support for public-sphere gender equality in the same way as one another. To start to understand why, future studies could address directly whether Muslims also perceive hostilities in all these contexts—directly or through indirect assessments of hostilities at the subnational level, which are more likely to be perceived. If particular hostilities are not perceived—for instance, because interaction with hostile natives is low or because politics are not closely followed—Muslims might not change the ways they live in Islam. Indeed, Röder and Spierings (2022) report that not the public's hostile attitudes but rather Muslims' perceptions of group discrimination matter here. Finally, because Western European countries across the board are currently relatively hostile to Muslims (Roggeband and Verloo, 2007; Foner and Alba, 2008; Yilmaz, 2015), differences in their absolute levels of hostility might be too small to be broadly translated to perceptions. Future studies could thus also address whether changes in these hostilities, which are more likely to be perceived, shape the ways Muslims live in Islam.

Another open question is how hostile environments shape Islamic religiosity's connection to gender values besides those in the public sphere. Islamic religiosity has been shown to be differently related to support for different gender values (Glas et al., 2019; Glas, 2022b), and the way hostilities shape these relations might consequently also differ. For instance, sexual values might be perceived to be unchangeable, core community values to a greater extent than public-sphere ones, and might be more strongly tied to and less easily decoupled from Islamic religiosity.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the current study has shown that there is no such thing as one essentially patriarchal Islam and simultaneously that Islamic religiosity is not a bridge to emancipation in Western Europe (Foner and Alba, 2008; Glas, 2022b; Röder and Spierings, 2022). The latter oppose findings from studies on Muslim-majority countries, where some religiosities have been shown to fuel support for public-sphere gender equality (Glas et al., 2018, 2019). At the risk of over-interpretation, this might imply that hostilities do matter from a global perspective, as hostilities toward Muslims in Western Europe are currently so ever-present that they might cause backlashes and close opportunities for Muslim feminism (Glas and Alexander, 2020). Still, even in this context, we do consistently find that some aspects of Islamic religiosity are not barriers to support for public-sphere gender equality among some groups. It deserves more study on what explains this, as it might be a prequel to an Islam that is less hostile to gender equality in Western Europe.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

The authors came up with this research idea together. SG wrote the majority of the manuscript. NS conducted the analyses and gave valuable feedback. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Part of the project was funded by the Dutch Research Council (VI.Vidi.191.023).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.909578/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^In more hostile contexts, belonging as attachment to faith is also expected to give way to religious belonging as orientation toward the minority community, because those contexts politicize Islam, rendering it a brighter boundary denoting different communities, thereby emphasizing that commitment to Islam entails commitment to a particular minority community (Alba and Nee, 2003).

2. ^Some of those strategies—including leaving the group, directly competing with the outgroup, or comparing the in-group with another, even more devalued out-group—are not expected to be available to or widely adopted by Muslims, because of the religion-tied nature of their group boundary and their overall low status in Western European countries.

3. ^Details on the harmonization, including the full code, can be obtained from the authors.

4. ^For attendance, all five coefficient are negative and four are statistically significant. For identification, three coefficients are significant, all negative. For praying only one coefficient is significant and one more is marginally significant, both being negative, implying that the negative average impact would not be picked up without the pooling of data.

5. ^We find indications that different gender values are differently shaped by Islamic religiosity (Glas et al., 2019; Glas, 2022b), particularly political leadership and university education. Prayer does not significantly reduce support for equality in political leadership, and neither identification nor prayer significantly reduces support for equality in education. These results underscore existing understandings that religiosity shapes different gender values in different ways (Glas et al., 2019; Glas, 2022b). Although we find no indications of religiosity being a bridge toward gender equality, these results further rebuke claims that Islam is necessarily a barrier to integration (Foner and Alba, 2008).

6. ^Mosque attendance has a negative and significant impact among women in 3 out of 5 surveys and among men in only 1 survey.

7. ^Identification's negative and significant effect among men is replicated in three (out of five) subsamples. Identification's non-significant effect among women is replicated throughout subsamples (two non-significant effects are positive). This supports the finding that identification matters more clearly and negatively among men. On praying, two significant effects, both negative, are found among women, while among men two effects are significant but in different directions. This indicates that the negative effect is more robust among women, albeit just, and that prayer is hardly an insurmountable barrier to emancipation.

8. ^The strength of the PRR also shows the expected negative coefficient but is not statistically significant at conventional levels (cf. Glas, 2022a). Only including this macro-level variable shows a similar result at p = 0.135. While this is not certain enough to draw strong conclusions, such a result on a low macro-level n further supports the conclusion we draw for hostility more generally, based on public attitudes variables.

9. ^Results can be obtained from the authors. Hostile contexts do not significantly increase religious identification, so we find no indication of rejection-identification (Branscombe et al., 1999).

References

Ajrouch, K. J. (2004). Gender, race, and symbolic boundaries: contested spaces of identity among Arab American adolescents. Sociol. Perspect. 47, 371–391. doi: 10.1525/sop.2004.47.4.371

Alba, R. (2005). Bright vs. blurred boundaries: second-generation assimilation and exclusion in France, Germany, and the United States. Ethnic Racial Stud. 28, 20–49. doi: 10.1080/0141987042000280003

Alba, R. D., and Nee, V. (2003). Remaking the American Mainstream. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Baker, P., Gabrielatos, C., and McEnery, T. (2013). Discourse Analysis and Media Attitudes: The Representation of Islam in the British Press. Cambridge: University Press.

Beek, M., and Fleischmann, F. (2020). Religion and integration: does immigrant generation matter? The case of Moroccan and Turkish immigrants in the Netherlands. J. Ethnic Migrat. Stud. 46, 3655–3676. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2019.1620417

Beller, J., Kröger, C., and Hosser, D. (2021). Disentangling honor-based violence and religion: the differential influence of individual and social religious practices and fundamentalism on support for honor killings in a cross-national sample of Muslims. J. Interpers. Viol. 36, 9770–9789. doi: 10.1177/0886260519869071

Bloom, P. B. N., Arikan, G., and Courtemanche, M. (2015). Religious social identity, religious belief, and anti-immigration sentiment. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 109, 203–221. doi: 10.1017/S0003055415000143

Branscombe, N. R., Schmitt, M. T., and Harvey, R. D. (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: implications for group identification and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 77, 135–149. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.135

Cornwall, M., Albrecht, S. L., Cunningham, P. H., and Pitcher, B. L. (1986). The dimensions of religiosity: a conceptual model with an empirical test. Rev. Relig. Res. 27, 226–244. doi: 10.2307/3511418

Dickey, B., Van Klingeren, M., and Spierings, N. (2022). Constructing homonationalist identities in relation to religious and LGBTQ+ outgroups: a case study of r/RightWingLGBT. Identities. doi: 10.1080/1070289X.2022.2054568

Diehl, C., Koenig, M., and Ruckdeschel, K. (2009). Religiosity and gender equality: comparing natives and Muslim migrants in Germany. Ethn. Racial Stud. 32, 278–301. doi: 10.1080/01419870802298454

Duderija, A. (2007a). Islamic groups and their world-views and identities: neo-traditional salafis and progressive Muslims. Arab Law Q. 21, 341–363. doi: 10.1163/026805507X247554

Duderija, A. (2007b). Literature review: identity construction in the context of being a minority immigrant religion: the case of western-born Muslims. Immigr. Minor. 25, 141–162. doi: 10.1080/02619280802018132

Eskelinen, V., and Verkuyten, M. (2020). Support for democracy and liberal sexual mores among Muslims in Western Europe. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 46, 2346–2366. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1521715

European Social Survey a. (2016). Cumulative File ESS 1-7. Data file edition ESS1-7e01. Norwegian Social Science Data Services.

European Social Survey b. (2016). Round 8 Data. Data File Edition ESS8e02. NSD - Norwegian Centre for Research Data.

European Social Survey c. (2018). Round 9: European Social Survey Round 9 Data. Data File Edition ESS9e03_1. NSD - Norwegian Centre for Research Data.

Fleischmann, F., Phalet, K., and Klein, O. (2011). Religious identification and politicization in the face of discrimination: support for political Islam and political action among the Turkish and Moroccan second generation in Europe. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 50, 628–648. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02072.x

Foner, N., and Alba, R. (2008). Immigrant religion in the US and Western Europe: bridge or barrier to inclusion?. Int. Migrat. Rev. 42, 360–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2008.00128.x

Geurts, N., and Van Klingeren, M. (2021). Do religious identity and media messages join forces? Young Dutch Muslims' identification management strategies in the Netherlands. Ethnicities. doi: 10.1177/14687968211060538

Ghafournia, N. (2020). Negotiating gendered religious space: Australian Muslim women and the mosque. Religions 11:686. doi: 10.3390/rel11120686

Ginges, J., Hansen, I., and Norenzayan, A. (2009). Religion and support for suicide attacks. Psychol. Sci. 20, 224–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02270.x

Giuliani, C., Olivari, M. G., and Alfieri, S. (2017). Being a “good” son and a “good” daughter: voices of Muslim immigrant adolescents. Soc. Sci. 6:142. doi: 10.3390/socsci6040142

Glas, S. (2021). How Muslims' denomination shapes their integration: the effects of religious marginalization in origin countries on Muslim migrants' national identifications and support for gender equality. Ethn. Racial Stud. 44, 83–105. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2021.1883082

Glas, S. (2022a). Exclusionary contexts frustrate cultural integration: migrant acculturation into support for gender equality in the labor market in Western Europe. Int. Migrat. Rev. 56, 941–75. doi: 10.1177/01979183211059171

Glas, S. (2022b). What gender values do Muslims resist?: How religiosity and acculturation over time shape Muslims' public-sphere equality, family role divisions, and sexual liberalization values differently. Social Forces soac004. doi: 10.1093/sf/soac004

Glas, S., and Alexander, A. (2020). Explaining support for muslim feminism in the Arab Middle East and North Africa. Gender Soc. 34, 437–466. doi: 10.1177/0891243220915494

Glas, S., and Spierings, N. (2021). Rejecting homosexuality but tolerating homosexuals: the complex relations between religiosity and opposition to homosexuality in 9 Arab countries. Soc. Sci. Res. 95:102533. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102533

Glas, S., Spierings, N., Lubbers, M., and Scheepers, P. (2019). How polities shape support for gender equality and religiosity's impact in Arab countries. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 35, 299–315. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcz004

Glas, S., Spierings, N., and Scheepers, P. (2018). Re-understanding religion and support for gender equality in Arab countries. Gender Soc. 32, 686–712. doi: 10.1177/0891243218783670

Güngör, D., Fleischmann, F., Phalet, K., and Maliepaard, M. (2013). Contextualizing religious acculturation. Eur. Psychol. 18, 203–214. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000162

Guveli, A., Ganzeboom, H., Platt, L., Nauck, B., Baykara-Krumme, H., Eroglu, S., et al. (2016). Intergenerational Consequences of Migration: Socio-Economic, Family and Cultural Patterns of Stability and Change in Turkey and Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jansen, W. (2004). The economy of religious merit: women and ajr in Algeria. J. North Afr. Stud. 9, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/1362938042000326263