- 1School of Politics and International Relations, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia

- 2Department of Political Science, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, United States

Sexist attitudes influence a wide range of political behaviors, including support for explicitly gendered policies like gender quotas. But we know much less about how sexism might broadly shape policy preferences. We argue that some policy domains are implicitly associated with being pro-women or pro-men because of gender socialization, gender segregation in the workforce, and differences in policy preferences in the general population and among political elites. As (hostile) sexists view women as inherently undeserving, making illegitimate claims on government, and getting ahead at the expense of men, we hypothesize that they will oppose policies associated with women, while supporting “male” policies such as defense and law enforcement. We test our hypothesis using the 2019 Australian Election Study and 2018 US Cooperative Congressional Study. We find similar patterns of policy preferences, wherein those holding sexist attitudes (net of other attitudes and demographic characteristics) want to cut funding for pro-women policies like social services, education, and health, while they approve of increased funding for law enforcement and defense.

Introduction

Gender role socialization theory argues that girls are socialized to prefer (and excel at) caring and interpersonal skills, while boys are socialized to have stronger leadership skills (Eagly and Koenig, 2006). Translating into adulthood, these gender roles shape the career choices that individuals make (Diekman et al., 2010) and the expectations about the relative traits of men and women (Eagly, 2007). These population-level gender roles then influence how men and women make political decisions, so that women in the general population support policies that help others and are in the ethos of care at higher rates than men (Diekman and Schneider, 2010; Lizotte, 2019).

Socialized perceptions of individuals' strengths and weaknesses may therefore translate into expectations about the policy strengths of women in political office (Huddy and Terkildsen, 1993), including that woman are better suited to policy responsibilities such as children, education, and welfare. Extensive research finds evidence of gender stereotyping of political candidates and leaders, with consequences for electoral outcomes (Bauer, 2015, 2017; Holman et al., 2016, 2019). Additionally, women in political office become experts on making policy in these areas, both through their own interest and because of expectations placed upon them by party leaders and voters (Krook and O'Brien, 2012; Holman, 2014; Lazarus and Steigerwalt, 2018; Homola, 2021). As a result of these population level and political factors, issues like education and welfare are firmly feminized in public opinion.

In this article, we draw on gender role socialization and the feminization of policy domains to theorize that “women's policies” represent a threat to the gendered system orientation (Azevedo et al., 2017) of citizens with sexist views. While previous studies have compared men and women's gendered perceptions of politicians, leaders, and policies, this study instead looks at the relationship between (specifically hostile) sexist attitudes and those gendered perceptions. Specifically, we hypothesize that sexism negatively predicts support for government spending in policy areas “owned” by women—through gender stereotypes, gender differences in attitudes in the general population, and the actions of women in office and party leaders. Just as sexist individuals may disapprove of women leaders, so too will they disapprove of policies that they perceive as benefiting women. We test this theory using comparable measures of support for policy expenditure in two representative datasets: the 2018 Cooperative Congressional Elections Study in the United States and the 2019 Australian Election Study.

Across both cases, we find significant evidence that sexist attitudes are correlated with opposition to increased expenditure on any policy considered pro-women, even when controlling for gender, race, partisan affiliation, socio-economic status, and religion. Those who hold sexist attitudes do support funding increases in some areas though: law enforcement and national defense, or policy areas seen as pro-men and associated with masculinity. Despite a variety of political differences across the countries, the results are remarkably similar in both the United States and Australia. Our results build on work by scholars who have called for a deeper understanding of the ways that gendered attitudes shape political engagement and policy preferences, above and beyond the role of gender (Huddy and Willmann, 2018; Cassese and Barnes, 2019; Cassese, 2020).

Policy Preferences and Hostile Sexism

Preferences for government policy priorities are shaped by multidimensional factors: partisan identity (Bolsen et al., 2014), self-interest (Compton and Lipsmeyer, 2019), sociotropic concerns (Mansfield and Mutz, 2009), and ideology (Linos and West, 2003). The ideological explanation emphasizes that individuals' beliefs about the role of government and the relative importance of government and private forces comprise a general worldview, which dictates attitudes on specific policies or government expenditure. While ideology is regularly included as a core determinant of policy preferences, research rarely considers how both ideology and policies (as well as partisan identity, and the prioritization of self or community) are deeply gendered.

Gendered attitudes underpin a variety of political experiences and preferences. Here, we look explicitly at sexism, a key system-justifying belief that enables people to explain and defend inequalities between women and men (Jost and Kay, 2005). In turn, system justification theory helps individuals justify policy positions that reinforce inequalities between groups and preserve the status quo. The most explicit manifestation of sexist attitudes in political psychology is “hostile sexism” (Glick and Fiske, 2001; Cassese and Barnes, 2019): the “antipathy toward women who are viewed as usurping men's power” (Glick and Fiske, 1996, p. 109). For hostile sexists, women seek advancement at the expense of men, and should therefore be viewed as untrustworthy, power-seeking, and manipulative (Glick and Fiske, 1996; Glick, 2019). Furthermore, women make illegitimate claims on government to advance their position beyond their innate capacities. At the extreme end, hostile sexists believe women do not deserve equal footing in society and that discrimination against them is justifiable (Glick, 2019).

These attitudes can predict a wide range of political behaviors, including perceptions of political scandals (Barnes et al., 2020), responses to electoral campaign strategies (Cassese and Holman, 2018), and vote choice in the 2016 American presidential election (Bock et al., 2017; Frasure-Yokley, 2018; Schaffner et al., 2018; Cassese and Barnes, 2019; Glick, 2019), 2019 Australian election (Beauregard, 2021), and 2019 British general election (de Geus et al., 2021). Additional work has shown that sexism shapes views of explicitly gendered policies like gender quotas (Beauregard and Sheppard, 2021), but also opposition to policies that are perceived to be a threat to the status quo such as climate policy (Benegal and Holman, 2021). We extend this literature by arguing that hostile sexist attitudes underpin respondents' views of which policy areas deserve funding, and which do not. Since hostile sexists view women as undeserving, as making illegitimate claims on government, and making gains at the expanse of men, we hypothesize that they will reject policies that are typically considered feminine and could be perceived as disturbing the gendered status quo and support policies considered masculine and that maintain the status quo.

Hostile sexism is just one dimension of sexist views present in the public; many people also hold benevolent sexist views, which are rooted in the separate social roles that men and women occupy in society (Glick and Fiske, 1996; Glick, 2019). Benevolent sexists view women as needing protecting and men as the natural providers of that protection. Research on the effects of benevolent sexism on political attitudes and behaviors are much more mixed: benevolent sexists were not more likely to support Trump in 2016 or Boris Johnson in 2019 (de Geus et al., 2021). In this paper, we focus on hostile sexism for both theoretical and methodological reasons (which we discuss throughout the paper). The next section reviews how some public policies are gendered and describes the mechanisms through which hostile sexist attitudes affect policy attitudes.

Gendered Perceptions of Policies and Hostile Sexism

Gender role socialization theorizes that children are differentially socialized through internal and external rewards and punishments: girls are encouraged to develop interpersonal skills, to be more caring, and to engage in interpersonal smoothing, while boys are more commonly socialized to have leadership skills, to be more assertive and aggressive, and to be more inwardly concerned (Eagly, 1987; Eagly and Karau, 2002; Schneider and Bos, 2019). These gender roles translate into expectations, or gender stereotypes, which tend to associate adult women with being more caring and compassionate while men are more aggressive and decisive. Accordingly, these have been linked with perceptions of women being better at caring work (such as being teachers or nurses) and men at work requiring physical abilities or leadership (Eagly, 1987; Eagly and Karau, 2002).

These gender stereotypes have carried on to the political arena where policies are often seen as either feminine or masculine. Generally, policy areas that concerns the public sphere are deemed to be masculine (construction and public work, correctional service/police, defense, military and national/public security, enterprise, and transport) and policy areas associated with the private sphere are considered feminine (children and family, education, and health and social welfare) (Herrnson et al., 2003; Krook and O'Brien, 2012). This gendered division of policy areas can be observed both at the elite and individual level.

Gendered Behaviors Among Women Elites

At the elite level, gender differences in expertise and authority align with gender roles in society. By way of example, women promoted to political executives have disproportionately been appointed to portfolio areas reflecting traditional stereotypes (Davis, 1997; Reynolds, 1999; Siaroff, 2000; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson, 2005; Krook and O'Brien, 2012; Barnes and O'Brien, 2018). Women cabinet ministers or secretaries are more commonly assigned to health, social welfare, education, family, and culture responsibilities while men are more often responsible for economic affairs, defense, employment, and the budget. Furthermore, when women are assigned to typically male executive roles such as finance or defense, it is often (ostensibly, at least) to help a government reverse public perceptions of corruption or malfeasance—what has been called a “housekeeping” role (Armstrong et al., 2021).

The same phenomenon exists at sub-executive levels. Research on parliamentary committee finds gender differences in membership that follow gender stereotypes of labor division (Heath et al., 2005; Barnes, 2014; Bolzendahl, 2014; Pansardi and Vercesi, 2017; Goodwin et al., 2021). For instance, Coffé et al. (2019) find that women are overrepresented on parliamentary committees examining femininized issues such as health and family while men are overrepresented on committees overseeing foreign affairs and defense. These gender differences may reflect MPs' individual preferences, or women MPs might strategically specialize in policy areas less favored by men as a way of gaining access to parliamentary committees. However, similar differences also occur in electoral campaigns where women are more likely to talk about social policy issues than men (Ennser-Jedenastik, 2017), and in the legislature once elected (Bäck and Debus, 2019).

These patterns can be accelerated and encouraged by the behaviors of parties themselves, which engage in strategic action to attract voters by focusing on policies that give them a comparative advantage (Ondercin, 2017; Holman and Kalmoe, 2021). Indeed, parties on the left elevate women's issues on their party platforms, elite communication, committee appointments, and votes (Holman and Kalmoe, 2021; Coffé et al., 2019; Espìrito-Santo et al., 2020). Over time, parties on the right have engaged in strategic action to try to attract women voters by supporting issues like gender quotas and putting women on party tickets, but these have not generally been accompanied by concrete policy action on women's issues (Weeks et al., 2022). The actions of parties, particularly on the left, to focus on issues associated with women's concerns, then attract women as voters, reinforcing these patterns (Ondercin, 2017, 2018; Homola, 2019).

Overall, this literature finds that gendered divisions of labor in political work are both persistent across time (although some evidence suggests that it is slowly declining in advanced democracies) and in executive, legislative, and campaign contexts. The presence of women in politics can prompt citizens to think about appropriate roles for women in their society, in turn cuing gendered responses to survey questions on political attitudes (Atkeson, 2003; Morgan and Buice, 2013). Further, female politicians' perceptions of gendered expertise may discourage them from speaking on masculine-coded policy areas and risk any associated criticism for failing to conform to gendered expectations or for not “staying in their lane” (Atkinson et al., 2022).

Gendered Perceptions of Policy Competencies

When politicians behave in ways that both create and perpetuate gendered norms around policy domains, citizens are more likely to perceive those domains as gendered, and then to reward or punish those politicians for how they perform in policy areas that align with their gender. American voters perceive women candidates as more qualified to deal with traditionally-defined female issues relating to the private sphere, and men as more competent to deal with public sphere related policies (Huddy and Terkildsen, 1993; Sanbonmatsu, 2002; Fridkin and Kenney, 2009; Sanbonmatsu and Dolan, 2009).

However, research outside the United States has found less delineation between feminine and masculine policy areas (Devroe and Wauters, 2018; Lefkofridi et al., 2019). In Australia, Carson et al. (2019) even find that women are perceived to be more competent than men at both military and health care issues, but this has so far proven an outlier in the field. Bauer (2020) finds that female candidates emphasizing typical female issues such as education, health care, and welfare have better leadership evaluations generally: female candidates engaging with typically feminine identified issues send the signal that they are representing women's interests in a traditionally male arena. Alternatively, voters punish female candidates when they are perceived as not advancing women's issues or when they lack feminine traits (Cassese and Holman, 2018). When women politicians fail in feminized policy domains—their “home turf”—they lose votes (Roberts and Utych, 2022).

Further, voters who hold traditional views on gender (e.g., “gender essentialists”) are more likely to punish political candidates who engage in issues outside of their gendered domains (Swigger and Meyer, 2019). Gender essentialism is the tendency to believe traditional gender differences are natural, intrinsic, and immutable factors. While gender essentialism is different than hostile sexism, Swigger and Meyer (2019)'s findings indicate that respondent gender is not sufficient in understanding hostility toward politicians who cross into counter-gender policy areas; attitudes toward men and women and their roles in society are more useful predictors of subsequent evaluations of those politicians.

Gender Gaps in Policy Preferences

Beyond the perceived competencies of men and women politicians, men and women voters regularly report differences in policy salience and preferred policy outcomes (regardless of the gender of the politician delivering a policy). Women are commonly more likely to support government expenditure in feminized issue domains such as welfare, health, and childcare (Schlesinger and Heldman, 2001; Gidengil et al., 2003; Inglehart and Norris, 2003; Huddy et al., 2008; Barnes and Cassese, 2017). On the other hand, men are more supportive of the military use of force (Lizotte, 2017, 2019). Feminist actors have successfully leveraged gender gaps in public opinion and issue salience to frame certain issues as “women's issues” and focus public attention accordingly (Campbell, 2016; Yildirim, 2021). This approach has seen policy success in domains such as welfare spending and childcare reforms, with women voters persuaded to support policies across partisan boundaries.

We might therefore expect a “backlash effect” among voters with hostile sexist attitudes, as greater public framing and perception of certain issues as benefiting women makes those issues particularly salient. Policy advocated by feminist actors (Celis and Childs, 2020) should be perceived as disrupting the male-dominated status quo and as such should be opposed by hostile sexists. Furthermore, the greater support for some policy issues by women than men should indicate to hostile sexists that these policies are unworthy of government action and government engaging on this policy can only occur at the expense of the interests and priorities of men.

One caveat in the discussion of policy preferences is that few existing measures constrain preferences to be revenue-neutral (Barnes et al., 2021). Survey questions rarely force respondents to choose to increase funding in some policy areas while reducing it in others, so there is nothing to stop an individual from reporting a preference for increased expenditure across all domains. Other measures take a more expressive approach, asking respondents to name (or choose from within a list) the most important issues facing them personally or the country in general. We might conceptualize these different approaches as occupying a spectrum “embracing complexity of budget decision-making” to “measuring top-of-mind responses to different types of policy.” We currently have little sense of how gendered policy preferences might be conditional on the complexity of the measure, although Barnes et al. (2021) find that women and men have very similar views on which policies deserve more and less funding (in a revenue-neutral context) compared with earlier findings that (in unconstrained measures) women are more likely to prefer more government spending across both “male” and “female” domains (e.g., Gidengil et al., 2003).

Overall, the extant literature provides ample evidence that many public policies are gendered—that is, commonly associated with one gender or the other, by both political elites and ordinary citizens. This gendered differentiation of government actions tends to reflect stereotypes about the division of the public and private sphere. However, it is important to note that the gender differences identified above are tendencies. Men (and women, respectively) can and do support typically feminine (masculine) policies and/or engage across “gender lines.” Gendered policy division patterns are the broader picture and are reflected in the division of labor among elected representatives, the stereotypes citizens use to assess politicians and their expertise, and the policy preferences of women and men. In turn, these patterns should signal to hostile sexists that feminine policy areas should be opposed while masculine policy priorities should be supported.

Individuals with high levels of hostile sexism will be more likely to support increasing funding for men's issue policies and decrease funding for women's issue policies.

Data and Methods

To evaluate our hypothesis on the relationship between sexist attitudes and policy preferences, we rely on the 2018 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) and the 2019 Australian Election Study (AES). The CCES is uses online sampling from YouGov panels, advertisements, and other survey draws to collect political attitudes from a nationally representative sample of 60,000 respondents in its 2018 survey. The AES is sampled via the Geo-Coded National Address Frame, a national register of Australian addresses, and surveys completed either online (push-to-web) or via hardcopy questionnaire. The 2019 survey received 2179 responses with an effective response rate of 42.1%. Both datasets contain similar measures of sexist attitudes and policy support. The inclusion of data from both the United States and Australia allows to compare the relationship between sexist attitudes and policy preferences in a context where sexism is cued (United States) to a context where sexism plays a much less visible role (Australia). Cassese and Barnes (2019) argue that the election of Donald Trump in 2016 introduced an explicit gendered dynamic into the election and that this campaign context can explain why sexist attitudes matter to understand vote choice in 2016, but not in 2012. On the other hand, the 2019 (and the previous 2016). Australian election did not feature any comparable degree of gendered dynamics. Leaders of both major political parties were men, and gender issues were not especially salient throughout the campaign. However, sexism in Australian politics does remain salient among some voters following the leadership of Julia Gillard from 2010 to 2013 (Beauregard, 2021). Without direct measures of perceived policy competencies, we focus exclusively on respondents' policy preferences in this study.

Spending Preferences

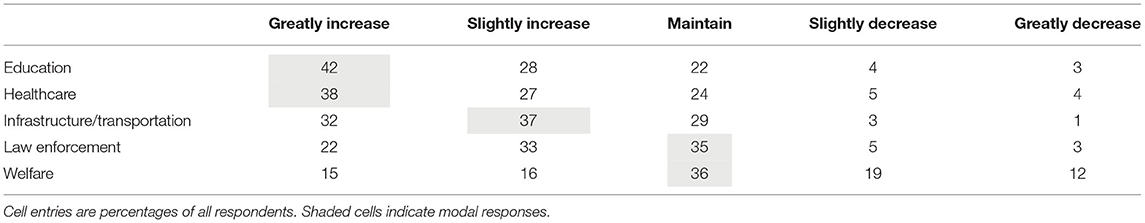

We use very similarly worded questions from the 2018 CCES and the 2019 AES to measure spending preferences among Americans and Australians. Using the 2018 Cooperative Congressional Elections Study (CCES), we look at responses to the question, “State legislatures must make choices when making spending decisions on important state programs. How would you like your legislature to spend money on each of the five areas below? Greatly increase; Slightly increase, Maintain; Slightly decrease; Greatly decrease.” As discussed, this measure does not constrain the respondent to revenue-neutrality but does provide a simple and easily understandable measure of expressive policy preferences. The five policy areas include: Education, Welfare, Healthcare, Transportation/Infrastructure, and Law Enforcement. The order of policies was randomized for each respondent. Among the areas, we categorize welfare, education, and healthcare as feminine issues areas, while law enforcement is a traditional masculine area (Lizotte, 2019); we are agnostic as to the gendered nature of infrastructure and transportation. Table 1 provides the spending priorities of Americans about these areas: across all respondents, increased education spending attracts the most support, while welfare spending is the least popular.

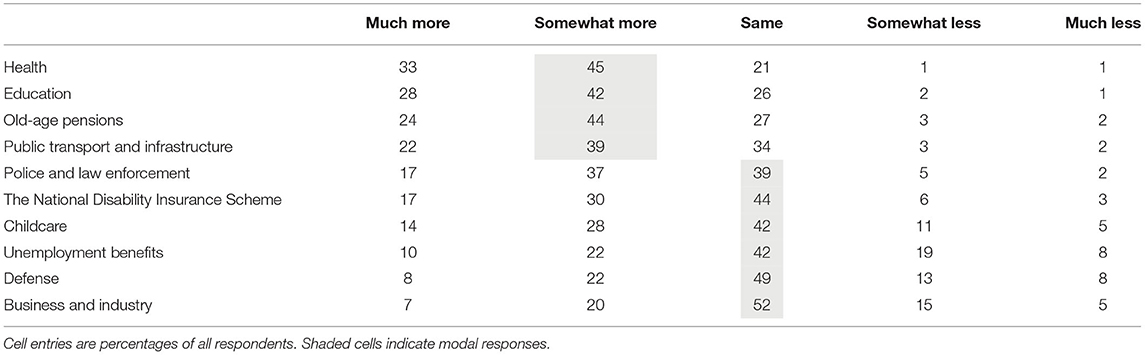

To evaluate policy preferences, we use 10 questions from the AES asking respondents: “Should there be more or less public expenditure in the following area? (1) Heath; (2) Education; (3) Unemployment benefits; (4) Defense; (5) Old-age pensions; (6) Business and industry; (7) Police and law enforcement; (8) The National Disability Insurance Scheme; (9) Public transport and infrastructure; and (10) Child care.” The order of policy (1) through (10) was randomized for each respondent. The response frame included: (1) Much more than now; (2) Somewhat more than now; (3) The same as now; (4) Somewhat less than now; and (5) Much less than now. Among the 10 policy areas, defense, police and law enforcement, and business and industry can be classified as masculine areas (Krook and O'Brien, 2012). Health, education, unemployment benefits, old-age pensions, the National Disability Insurance Scheme, and childcare are considered feminine policy areas. Again, we are agnostic about public transport and infrastructure.

Table 2 displays the spending preferences of Australians in the 2019 election. Most respondents favor increasing spending for health, education, old-age pensions, public transport and infrastructure, and police and law enforcement. A plurality of respondents favors spending to remain the same for the National Disability Insurance Scheme, childcare, and unemployment benefits while a majority of respondents want spending to remain at the same level for business and industry.

Sexism

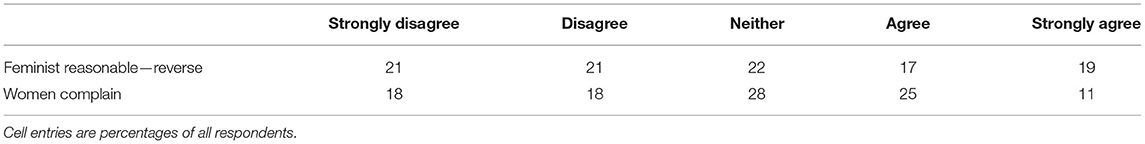

Both surveys ask questions aimed at tapping into hostile sexist views; we focus on measuring hostile sexism because we have clear theoretical expectations for how hostile sexism should relate to views on funding by policy arena and we have comparable measures across surveys in the two countries. We use two questions from the CCES to evaluate sexist attitudes: “Feminists are making entirely reasonable demands of men” (reverse coded) and “When women lose to men in a fair competition, they typically complain about being discriminated against.” Table 3 shows that responses to both questions are distributed evenly across all five categories; slightly more respondents display hostile sexist responses than not. We combine the two questions into a single index of the averaged response to the questions for subsequent regression analyses. These two questions are highly correlated (0.43) and hang together well (alpha 0.7059) in a single measure. Main results from the paper are replicated with individual sexism measures (see Appendix B).

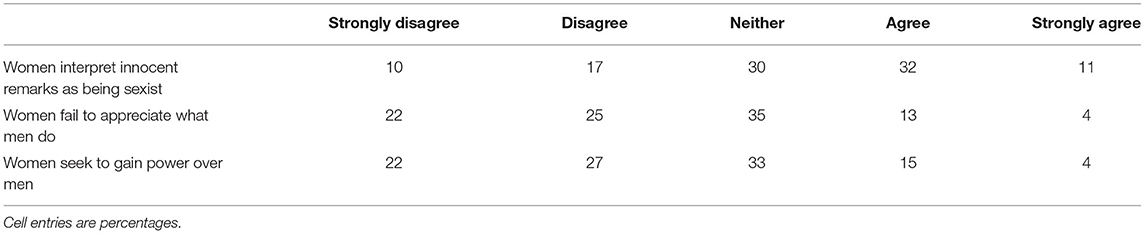

Sexist attitudes among Australians are measured with an abbreviated version of the hostile sexism scale developed by (Glick and Fiske, 1996). The AES includes three questions from this scale: “Please say whether you strongly agree, agree, disagree or strongly disagree with each of these statements (1) Many women interpret innocent remarks or acts as being sexist; (2) Women fail to appreciate what men do for them; and (3) Women seek to gain power by getting control over men.” All three questions are correlated with each other and were combined in a single index of the averaged response to the questions (alpha 0.8303). Main results from the paper are replicated with individual sexism measures (see Appendix B). Table 4 presents the distribution of answers for all three sexism questions and demonstrates that more than 40% of Australian respondents agree or strongly agree that women interpret innocent remarks or acts as being sexist. This is followed by over 18% of Australians who agree with the statement that women seek to gain power by getting control over men and 17% of respondents who agree that women fail to appreciate what men do for them. Across the three questions, Australian respondents demonstrate less hostile sexism than 2018 American respondents.

Finally, a series of control variables are used in the analyses with efforts to standardize across the two datasets as much as possible. The control variables include gender (Women = 1), age, annual household income (categorical), education (categorical), partisanship (Democratic = 1 in US; Labor = 1 in Australia; others = 0), and religion (Catholic, Evangelical, not religious, others). In the United States, we control for race.

Results

To start, we examine the bivariate relationships between sexism and spending preferences through correlations and linear fit lines, presenting the US data in the left-hand pane and the Australian data in the right-hand pane. Given that we have expectations for sexism to be associated with preferences for decreased spending in some areas and increased spending in others, we separate out women's issue areas (left) and men's issue areas (right). We have no strong a priori expectations for the gendered nature of infrastructure and transportation; some research would suggest that women in office prioritize the funding of issues like education and social services at the expense of infrastructure (e.g., Barnes et al., 2021) and men hold the overwhelming majority of jobs in this area (Barnes and Holman, 2021). This might produce the expectations that this area will be associated with men's issues and sexism will be positively correlated with the area. However, given that transportation is a public good and the AES asks about “public” transportation, we might expect that this policy area would be seen as expanding the size of government and as a form of wealth transfer, thus grouping it with women's issues. We thus are agnostic about the direction of the effect for attitudes about spending on infrastructure and transportation, but generally group it with men's issues in the results that we present.

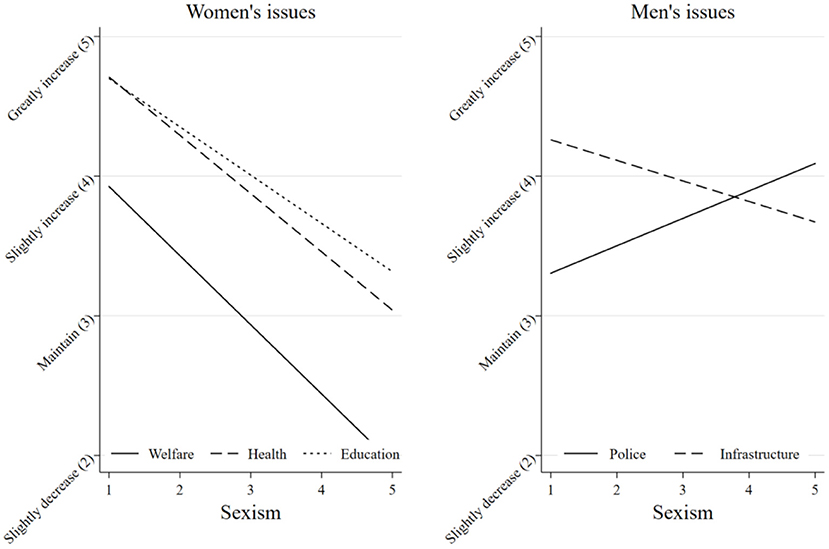

Looking first at the bivariate relationship between spending and sexism for women's issues in the United States (see Figure 1), we see a strong, consistent, negative relationship, with preferences for spending on welfare, education, and health decreasing as an individual's sexist preferences increase in the United States. With men's issues, however, we see a different pattern. Spending preferences on police fit with our expectations, but infrastructure does not.

Figure 1. Spending preferences and Sexism (United States, CCES 2018). Sexism ranges from 1 (low levels of sexism) to 5 (high levels of sexism).

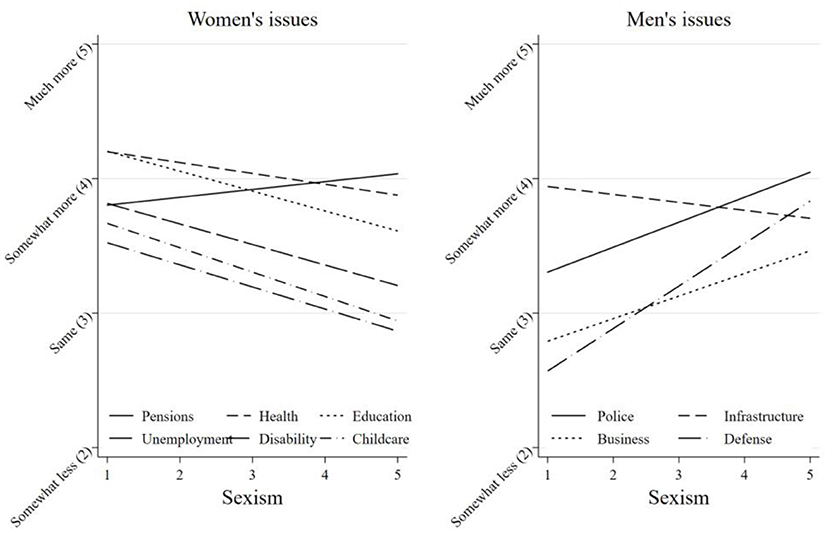

We see very similar patterns when we look at the bivariate relationships among Australians, as displayed in Figure 2. Overall, we see consistent patterns: sexism is associated with decreased preferences for spending on women's issues and increased spending on men's issues. Again, however, we find exceptions: pensions do not follow this pattern, with sexism positively correlated with the issue, even as it falls somewhat under the “women's issue” umbrella. And, again, like we found in the United States, we see that infrastructure is not positively correlated with sexism, but instead negatively correlated.

Figure 2. Spending preferences and Sexism (Australia, AES 2019). Sexism ranges from 1 (low levels of sexism) to 5 (high levels of sexism).

Multivariate Models

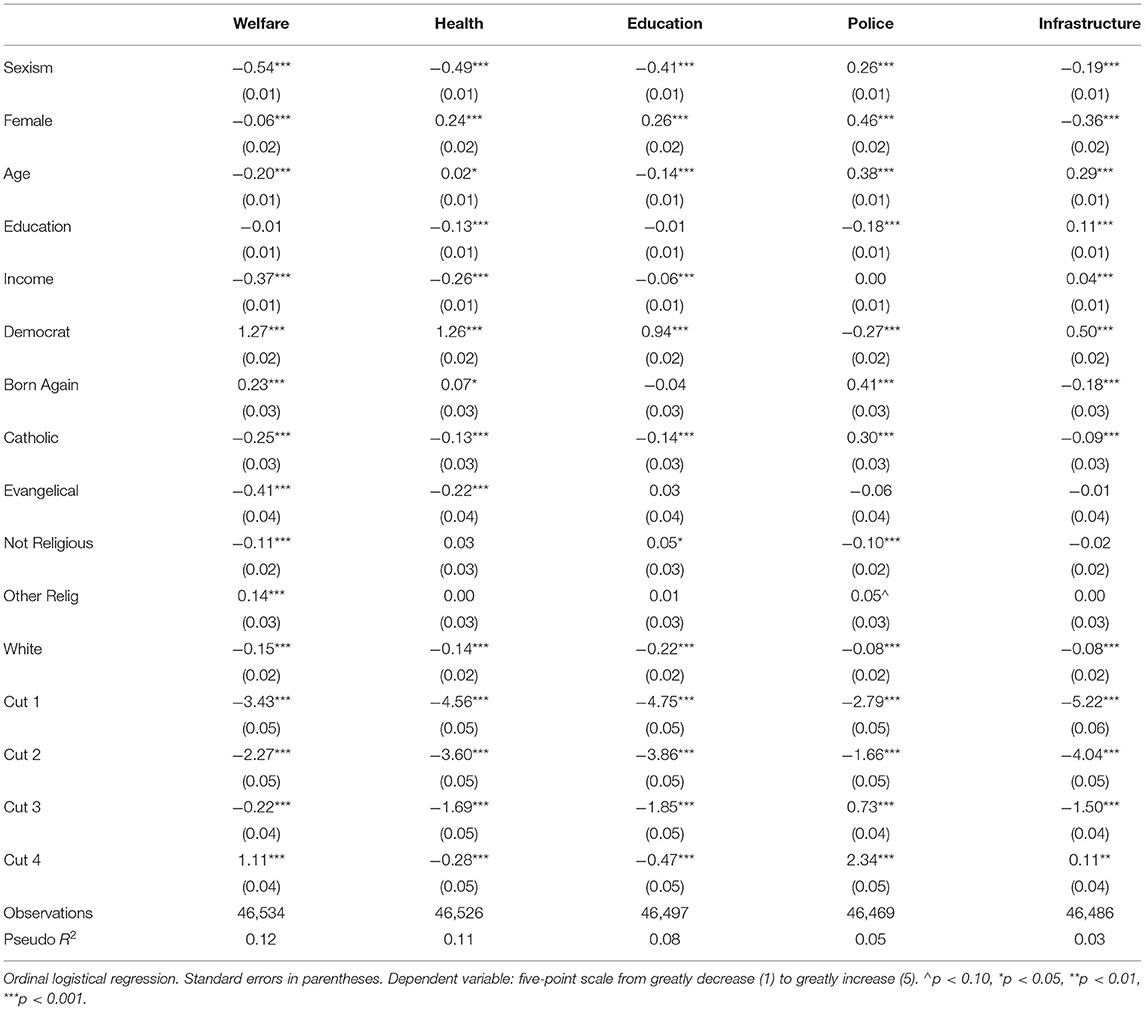

We next present multivariate models chronologically and start with the United States with the 2018 CCES results (Table 5), estimating each model of support for decreased or increased spending on welfare, health care, education, law enforcement, and transportation/infrastructure as an ordinal logistic regression. As expected, we find that hostile sexist attitudes are associated with support for reducing state spending on welfare, health care, and education and increasing spending on law enforcement. Interestingly, we see a continuation of the pattern on infrastructure: we find significant negative effects for transportation / infrastructure, a policy domain where we were agnostic about the effects of sexism. As we previously note, it may be that sexists associated a larger state and more spending generally with women's issues; we also see that the explained variance on the infrastructure model is much lower than the other models, suggesting different explanatory variables for spending on infrastructure.

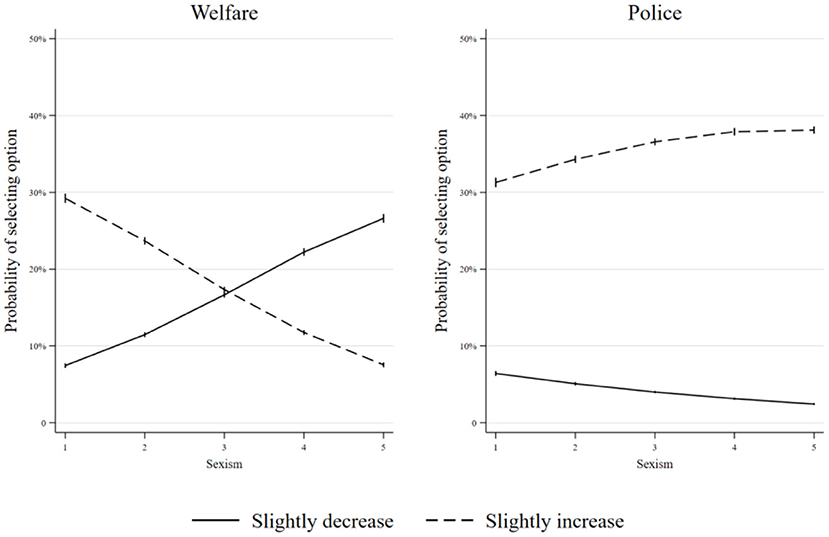

To provide an example of the substantive effects of sexism on policy attitudes, we next use post-estimation predicted probabilities to examine the average level of support for funding change across the spectrum of sexist attitudes in Figure 3. We estimate how the distribution of selecting “slightly decrease” and “slightly increase” as response options varies by individual sexist attitudes and plot those effects, with vertical bars indicating confidence intervals. We find substantively large, counter directional trends for the effect on sexism on attitudes about welfare: among those with low levels of sexism, there is a 29% probability of selecting the option “slightly increase” but only an 8% probability of selecting “slightly decrease.” In comparison, among those with high levels of sexism, we see almost exactly the reverse pattern: a 7% probability of selecting the slightly increase option and a 27% probability of selecting the slightly decrease. In comparison, sexism shapes views toward policing but with very different overall patterns: the probability of selecting “slightly increase” improves from 31 to 37% as individuals increase in sexism, and slightly decrease declines from 6 to 2%. In short, sexism is associated with much larger swings in preferences for the women's issue compared to the men's issue.

Figure 3. Sexism and preferences for welfare and law enforcement spending (US, CCES 2018). Post-hoc predicted values selection of “slightly decrease” and “slightly increase” generated from Table 5 with full controls. Vertical bars are 95% confidence intervals.

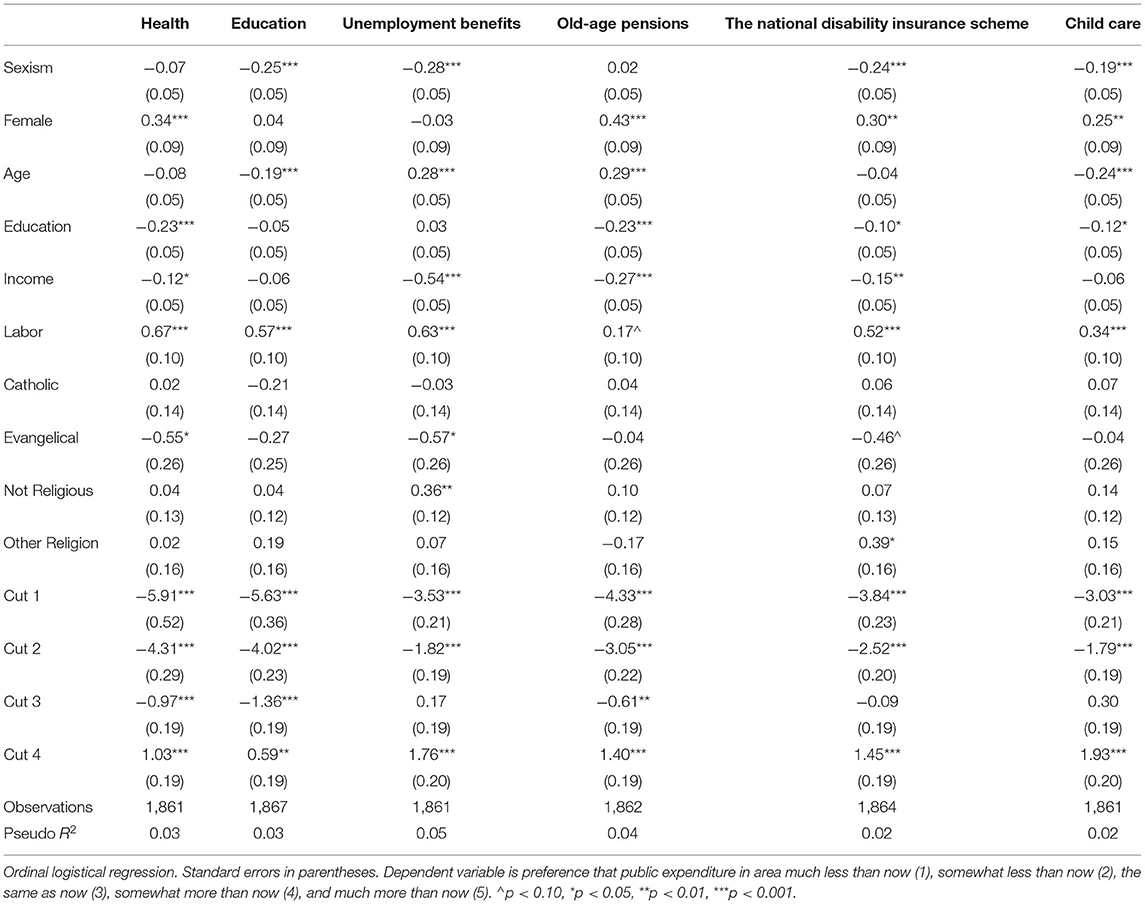

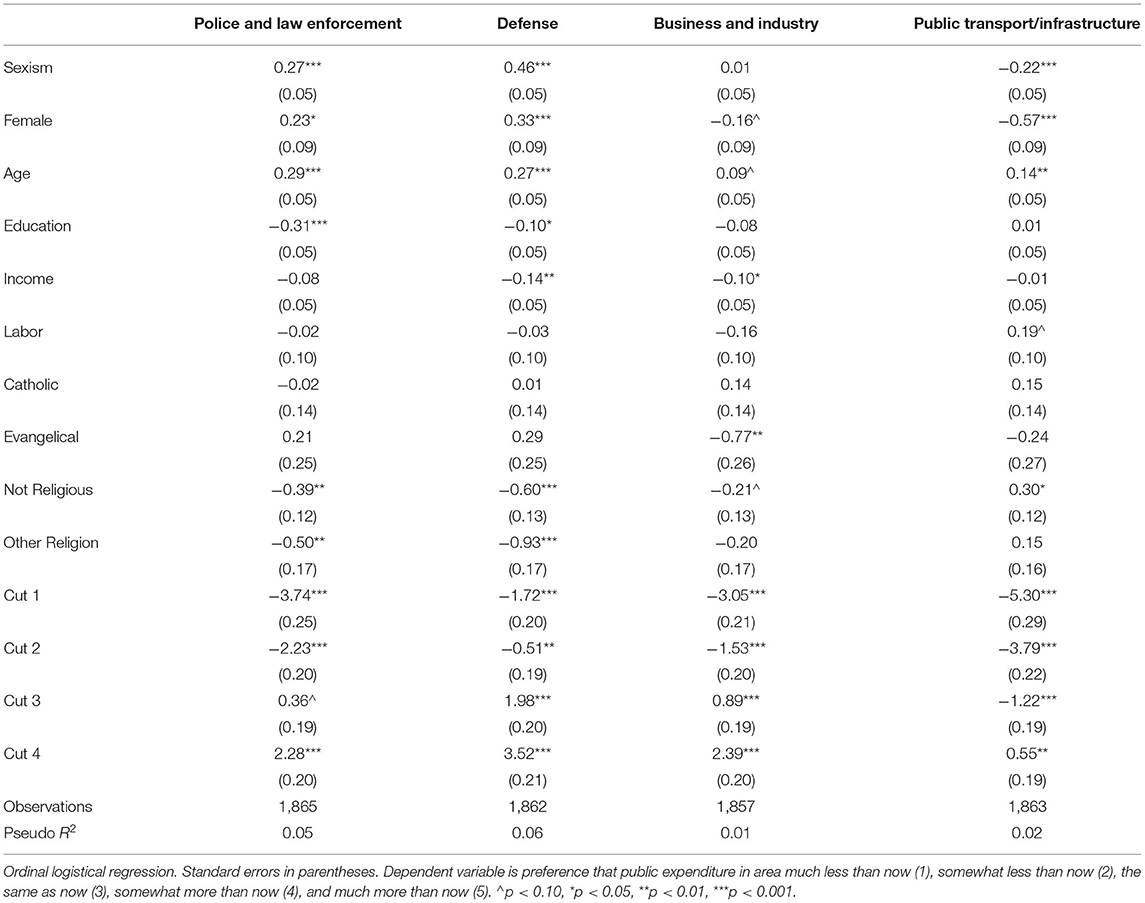

We next examine these multivariate relationships in Australia using ordinal logistical regression models. As expected, Australian respondents with high levels of hostile sexism are significantly less likely to favor increasing spending for women-friendly policy areas such as education, unemployment benefits, the National Disability Insurance Scheme, and childcare (Table 6) as well as policy areas associated with men (such as defense and police) and those areas where we are agnostic toward the effects (such as infrastructure); these results are presented in Table 7. We do identify surprising findings, starting with the non-significant relationship between sexist attitudes and preferences for health spending, aged pensions, and business and industry. Most research on gendered policy areas is from the United States; one possibility for these findings is that these policy areas are not associated with a particular gender in Australia. For example, health may be perceived as a comparatively neutral policy due to the presence of universal government-provided healthcare.

Among the masculine policy areas included in Table 6, hostile sexist attitudes are significantly associated with preferences for increased spending on defense and police and law enforcement, supporting our hypothesis. Sexist respondents' preferences for decreased spending for public transport and infrastructure are interesting. We were agnostic to the gendering of these areas with a weak expectation that sexist orientations should lead to preference for increased spending. We do not find this: sexism is associated with reduced preferences for spending. A possible explanation for the results in Table 6 might be that the questions in the AES include the words “public transport.” Public transport might be associated in the mind of respondents with welfare types of programs involving government spending that tend to benefit women. In this sense, taking the bus or train to go to work as opposed to using your car might be perceived as feminine (Benegal and Holman, 2021). Consequently, respondents holding sexist attitudes favor less spending on such government services.

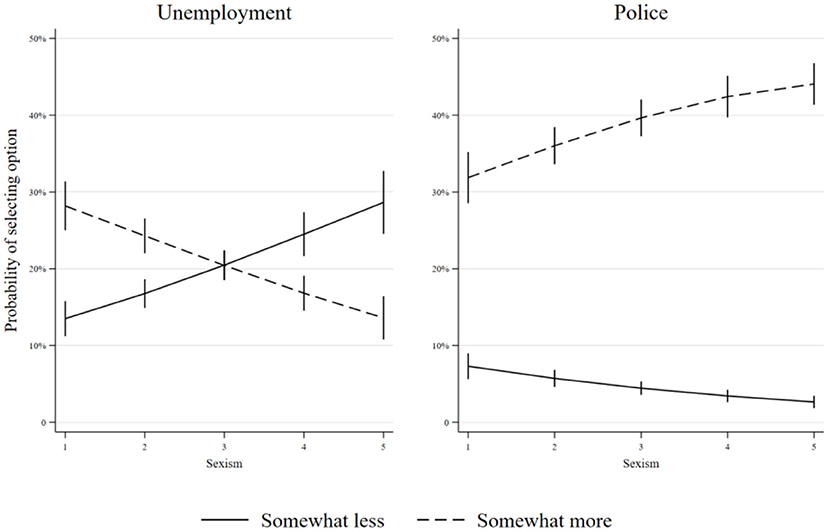

As another simple illustration of the patterns that we see in the data, we again use post-estimation predicted probabilities to examine the average level of support for funding change across the spectrum of sexist attitudes (Figure 4). We focus on the probability that an individual selected either of the mild preference options: “Slightly less” and “Slightly more.” We see a crossing and substantively large substantive effects for the spending preferences on the woman's issue (unemployment benefits) in a pattern that looks remarkably similar to the US data. Here, we also observe an interesting pattern in the policing question, where the effect of sexism is substantively larger in shaping the probability of selecting the “somewhat more” option. Here, the probability of selecting “somewhat less” declines from 7 to 2%, but “somewhat more” increases from 31 to 44% across the sexism measure.

Figure 4. Sexism and spending preferences on unemployment benefits and police, AES 2019. Post-hoc predicted selection of “slightly decrease” and “slightly increase” values generated from Tables 6, 7 with full controls. Vertical bars are 95% confidence intervals.

Conclusion

The findings presented above support our hypotheses regarding the relationship between sexist attitudes and policy spending preferences. Specifically, we hypothesized that individuals displaying hostile sexist attitudes should be less supportive of public policy considered feminine, and more supportive of masculinized public policies compare individuals that disagree with sexist attitudes. We find significant evidence that sexist attitudes are correlated with rejection of spending on welfare policies including health education, childcare and disability insurance, even when controlling for gender, race, partisan affiliation, socio-economic status, and religion. On the other hand, sexist attitudes are significantly associated with preferences for greater spending on police, law enforcement, and defense. We explain these findings by arguing that some public policies are “owned” by women, through gender stereotypes, gender differences in attitudes in the general population, and the actions of women in office and party leaders. As hostile sexism is associated with beliefs that women are undeserving and are making illegitimate claims on government, and that any gain achieved by women will be at the expanse of men, sexist individuals believe that feminine policy areas are similarly undeserving, illegitimate, and take away from more worthy masculine policy areas. We find support for this argument with public opinion data from the 2018 Cooperative Congressional Elections Study in the United States and the 2019 Australian Election Study.

The findings present here help resolve one of the central challenges of understanding the role of sexism in modern politics. Our approach accounts for the presence of hostile sexism across gender divides (Beauregard and Sheppard, 2021) and gets closer to uncovering a mechanism that explains why gendered assessments of “suitable” political work for men and women politicians persist, even as we become more used to seeing women in power (Atkinson, 2020; Hargrave and Blumenau, 2021). Indeed, the increased presence of women politicians responsible and discussing welfare, health, family, and childcare policies might lead hostile sexist individuals to view these policy areas as unworthy of government action, as taking resources away from more deserving (male) policy area, and as being use by women to challenge the status quo, which in turn will lead hostile sexists to oppose resources for femininized policy areas. That women in government are more effective policy leaders (Holman et al., 2021; Homola, 2021) might accelerate backlash effects from sexists.

One of the consistent and surprising findings in our research is that infrastructure does not fit with our expectations as a “man's issue” in either the United States or Australia. Here, more work in needed to understand attitudes about infrastructure spending in both countries and how it fits or does not fit with a gendered categorization scheme. Research on spending outcomes at the state and local level find that women's representation (particularly women from specific backgrounds) is often associated with increased spending on women's issues (Holman, 2014; Barnes et al., 2021), and decreased spending on infrastructure. Future research might consider the ways that attitudes about infrastructure map onto more general preferences about the size of government and gendered associations.

Despite a variety of political differences across the countries, the results are remarkably similar in both the United States and Australia. As such, influence of sexism on political behavior does not necessarily need to be cued by election campaign dynamics or strategies—at least for policy preferences. This may set policy preferences apart from voting behavior for candidates (see Cassese and Holman, 2018). Arguably, gender and sexism were more of a direct concern in the United States than Australia in the last election in both countries. However, Australia did experience public debates concerning gender and sexism during and after the 2010–2013 prime ministership of Julia Gillard, and this may have ongoing effects on political attitudes. Our findings also present enlightening differences between the two countries, particularly on attitudes toward health spending. While American sexists prefer less spending on health, there is no significant relationship between sexist orientations and spending preferences in Australia. This result might indicate that some policy areas can be delivered and framed in such ways as not to follow the typically feminine/private and masculine/public dichotomy. Finally, in both the United States and Australia, racism also shapes public opinion (Hutchings et al., 2021) but operates on an overlapping and varying structure from sexism (Banda and Cassese, 2021). Future research might evaluate how some policy arenas are both gendered and racialized (Benegal and Holman, 2021), thus shaping support for policies.

While the United States and Australia provide excellent comparative cases because of the similarities of the two countries, the nature of politics, service provision, and sexism in the countries also gives rise to questions about the applicability of these findings to other countries. Future research might examine the degree to which these relationships are present in countries with stronger welfare systems, pluralistic multi-party governing structures, or lower levels of sexism. Examining these relationships in New Zealand, Sweden, or Germany, for example, might tell us something about how politics shape the relationship between sexism and policy preferences. While scholars have documented the relationship between sexism and vote choice in the United States (Cassese and Barnes, 2019; Cassese and Holman, 2019), Australia (Beauregard, 2021), and the United Kingdom (de Geus et al., 2021), we know much less about gender stereotypes, sexism, and policy preferences in other settings, including in the Global South. Future research might also consider the ways that policy preferences and sexism shape preferences for right-leaning parties, particularly in multi-party systems or those with more extremist parties.

Data Availability Statement

Data for both the CCES and the AES are open-access and can be freely downloaded. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.892111/full#supplementary-material

References

Armstrong, B., Barnes, T. D., O'Brien, D. Z., and Taylor-Robinson, M. (2021). Corruption, accountability, and women's access to power. J. Polit. doi: 10.1086/715989

Atkeson, L. R. (2003). Not all cues are created equal: the conditional impact of female candidates on political engagement. J. Polit. 65, 1040–1061. doi: 10.1111/1468-2508.t01-1-00124

Atkinson, M. L. (2020). Gender and policy agendas in the post?war house. Policy Stud. J. 48, 133–156. doi: 10.1111/psj.12237

Atkinson, M. L., Reza, M., and Windett, J. H. (2022). Detecting diverse perspectives: using text analytics to reveal sex differences in congressional debate about defense. Polit. Res. Quart. doi: 10.1177/10659129211045048

Azevedo, F., Jost, J. T., and Rothmund, T. (2017). ‘Making America Great Again': system justification in the U.S. presidential election of 2016. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 3, 231–240. doi: 10.1037/tps0000122

Bäck, H., and Debus, M. (2019). When do women speak? A comparative analysis of the role of gender in legislative debates. Polit. Stud. 67, 576–596. doi: 10.1177/0032321718789358

Banda, K., and Cassese, E. (2021). Hostile sexism, racial resentment, and political mobilization. Polit. Behav. 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11109-020-09674-7

Barnes, T. D. (2014). Women's representation and legislative committee appointments: the case of the Argentine Provinces. Rev. Uruguaya Ciencia Polít. 23, 135–163.

Barnes, T. D., Beall, V., and Holman, M. R. (2021). Pink collar representation and policy outcomes in U.S. States. Legisl. Stud. Q. 46, 119–154. doi: 10.1111/lsq.12286

Barnes, T. D., Beaulieu, E., and Saxton, G. W. (2020). Sex and corruption: how sexism shapes voters' responses to scandal. Polit. Groups Ident. 8, 103–121. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2018.1441725

Barnes, T. D., and Cassese, E. C. (2017). American party women: a look at the gender gap within parties. Polit. Res. Q. 70, 127–141. doi: 10.1177/1065912916675738

Barnes, T. D., and Holman, M. R. (2021). Essential work is gender segregated: This shapes the gendered representation of essential workers in political office. Soc. Sci. Q. 101, 1827–1833. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12850

Barnes, T. D., and O'Brien, D. Z. (2018). Defending the realm: the appointment of female defense ministers worldwide. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 62, 355–368. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12337

Bauer, N. M. (2015). Emotional, sensitive, and unfit for office? Gender stereotype activation and support female candidates. Polit. Psychol. 36, 691–708. doi: 10.1111/pops.12186

Bauer, N. M. (2017). The effects of counterstereotypic gender strategies on candidate evaluations. Polit. Psychol. 38, 279–95. doi: 10.1111/pops.12351

Bauer, N. M. (2020). A feminine advantage? Delineating the effects of feminine trait and feminine issue messages on evaluations of female candidates. Polit. Gender 16, 660–680. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X19000084

Beauregard, K. (2021). Sexism and the Australian voter: how sexist attitudes influenced vote choice in the 2019 federal election. Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 56, 298–317. doi: 10.1080/10361146.2021.1971834

Beauregard, K., and Sheppard, J. (2021). Antiwomen but proquota: disaggregating sexism and support for gender quota policies. Polit. Psychol. 42, 219–237. doi: 10.1111/pops.12696

Benegal, S., and Holman, M. R. (2021). Understanding the importance of sexism in shaping climate denial and policy opposition. Clim. Change 167, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10584-021-03193-y

Bock, J., Byrd-Craven, J., and Burkley, M. (2017). The role of sexism in voting in the 2016 presidential election. Pers. Individ. Dif. 119, 189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.026

Bolsen, T., Druckman, J. N., and Lomax Cook, F. (2014). The influence of partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion. Polit. Behav. 36, 235–262. doi: 10.1007/s11109-013-9238-0

Bolzendahl, C. (2014). Opportunities and expectations: the gendered organization of legislative committees in Germany, Sweden, and the United States. Gender Soc. 28, 847–876. doi: 10.1177/0891243214542429

Campbell, R. (2016). Representing women voters: The role of the gender gap and the response of political parties. Party Polit. 22, 587–597. doi: 10.1177/1354068816655565

Carson, A., Ruppanner, L., and Lewis, J. M. (2019). Race to the top: using experiments to understand gender bias towards female politicians. Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 54, 439–455. doi: 10.1080/10361146.2019.1618438

Cassese, E. C. (2020). Straying from the flock? A look at how Americans' gender and religious identities cross-pressure partisanship. Polit. Res. Q. 73, 169–183. doi: 10.1177/1065912919889681

Cassese, E. C., and Barnes, T. D. (2019). Reconciling Sexism and women's support for republican candidates: a look at gender, class, and whiteness in the 2012 and 2016 presidential races. Polit. Behav. 41, 677–700. doi: 10.1007/s11109-018-9468-2

Cassese, E. C., and Holman, M. R. (2018). Party and gender stereotypes in campaign attacks. Polit. Behav. 40, 785–807. doi: 10.1007/s11109-017-9423-7

Cassese, E. C., and Holman, M. R. (2019). Playing the woman card: ambivalent Sexism in the 2016 U.S. presidential race. Polit. Psychol. 40, 55–74. doi: 10.1111/pops.12492

Celis, K., and Childs, S. (2020). Feminist Democratic Representation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Coffé, H., Bolzendahl, C., and Schnellecke, K. (2019). Parties, issues, and power: women's partisan representation on German parliamentary committees. Eur. J. Polit. Gender 2, 257–281. doi: 10.1332/251510818X15311219135250

Compton, M. E., and Lipsmeyer, C. S. (2019). Everybody hurts sometimes: how personal and collective insecurities shape policy preferences. J. Polit. 81, 539–551. doi: 10.1086/701721

Davis, R. H. (1997). Women and Power in Parliamentary Democracies: Cabinet Appointments in Western Europe, 1968-1992. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

de Geus, R., Ralph-Morrow, E., and Shorrocks, R. (2021). Understanding ambivalent Sexism and its relationship with electoral choice in Britain. Br. J. Polit. Sci. doi: 10.1017/S0007123421000612

Devroe, R., and Wauters, B. (2018). Political gender stereotypes in a List-PR system with a high share of women MPs: competent men versus leftist women? Polit. Res. Q. 71, 788–800. doi: 10.1177/1065912918761009

Diekman, A. B., Brown, E. R., Johnston, A. M., and Clark, E. K. (2010). Seeking congruity between goals and roles: a new look at why women opt out of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics careers. Psychol. Sci. 21, 1051–1057. doi: 10.1177/0956797610377342

Diekman, A. B., and Schneider, M. C. (2010). A social role theory perspective on gender gaps in political attitudes. Psychol. Women Q. 34, 486–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01598.x

Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-Role Interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Eagly, A. H. (2007). Female leadership advantage and disadvantage: resolving the contradictions. Psychol. Women Q. 31, 1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00326.x

Eagly, A. H., and Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol. Rev. 109, 573–594. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573

Eagly, A. H., and Koenig, A. M. (2006). “Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: implication for prosocial behavior,” in Sex Differences and Similarities in Communication, eds K. Dindia and D. Canary (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 161–177.

Ennser-Jedenastik, L. (2017). Campaigning on the welfare state: the impact of gender and gender diversity. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 27, 215–228. doi: 10.1177/0958928716685687

Escobar-Lemmon, M., and Taylor-Robinson, M. M. (2005). Women ministers in Latin American government: when, where, and why? Am. J. Pol. Sci. 49, 829–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00158.x

Espìrito-Santo, A., Freire, A., and Serra-Silva, S. (2020). Does women's descriptive representation matter for policy preferences? The role of political parties. Party Polit. 26, 227–237. doi: 10.1177/1354068818764011

Frasure-Yokley, L. (2018). Choosing the velvet glove: women voters, ambivalent Sexism, and vote choice in 2016. J. Race Ethnic. Polit. 3, 3–25. doi: 10.1017/rep.2017.35

Fridkin, K. L., and Kenney, P. J. (2009). The role of gender stereotypes in US Senate campaigns. Politics Gender 5, 301–324. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X09990158

Gidengil, E., Blais, A., Nadeau, R., and Nevitte, N. (2003). “Women to the left? Gender differences in political beliefs and policy preferences,” in Women and electoral politics in Canada. Don Mills, eds M. Tremblay and L. Trimble (Ontario: Oxford University Press), 140–159.

Glick, P. (2019). Gender, sexism, and the election: did sexism help Trump more than it hurt Clinton? Politics Groups Identities 7, 713–723. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2019.1633931

Glick, P., and Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 491. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

Glick, P., and Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. Am. Psychol. 56, 109. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.2.109

Goodwin, M., Holden Bates, S., and McKay, S. (2021). Electing to do women's work? Gendered divisions of labor in U.K. select committees, 1979–2016. Polit. Gender 17, 607–639. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X19000874

Hargrave, L., and Blumenau, J. (2021). No longer conforming to stereotypes? Gender, political style and parliamentary debate in the UK. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 1–18. doi: 10.1017/S0007123421000648

Heath, R. M., Schwindt-Bayer, L. A., and Taylor-Robinson, M. M. (2005). Women on the sidelines: women's representation on committees in Latin American legislatures. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 49, 420–436. doi: 10.2307/3647686

Herrnson, P. S., Lay, J. C., and Stokes, A. K. (2003). Women running as women: candidate gender, campaign issues, and voter-targeting strategies. J. Polit. 65, 244–255. doi: 10.1111/1468-2508.t01-1-00013

Holman, M. R. (2014). Women in Politics in the American City. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Holman, M. R., and Kalmoe, N. P. (2021). Partisanship in the# MeToo era. Pers. Polit. 48, 1–18. doi: 10.1017/S1537592721001912

Holman, M. R., Merolla, J. L., and Zechmeister, E. J. (2016). Terrorist threat, male stereotypes, and candidate evaluations. Polit. Res. Q. 69, 134–147. doi: 10.1177/1065912915624018

Holman, M. R., Merolla, J. L., Zechmeister, E. J., and Wang, D. (2019). Terrorism, gender, and the 2016 US presidential election. Elect. Stud. 61, 02033. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2019.03.009

Holman, M. R., Mitchell Mahoney, A., and Hurler, E. (2021). Let's Work Together: bill success via women's cosponsorship in U.S. state legislatures. Polit. Res. Q. doi: 10.1177/10659129211020123

Homola, J. (2019). Are parties equally responsive to women and men? Br. J. Polit. Sci. 49, 957–975. doi: 10.1017/S0007123417000114

Homola, J. (2021). The effects of women's descriptive representation on government behavior. Legisl. Stud. Q. doi: 10.1111/lsq.12330

Huddy, L., Cassese, E., and Lizotte, M. K. (2008). “Gender, public opinion, and political reasoning,” in Political women and American democracy, eds C. Wolbrecht, K. Beckwith, and L. Baldez (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 31–49. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511790621.005

Huddy, L., and Terkildsen, N. (1993). Gender stereotypes and the perception of male and female candidates. Am. J. Polit. Sci. (37), 119–147. doi: 10.2307/2111526

Huddy, L., and Willmann, J. (2018). The Feminist Gap in American Partisanship. Unpublished Manuscript, Department of Political Science, Stony Brook, NY: Stony Brook University.

Hutchings, V., Nichols, V. C., Gause, L., and Piston, S. (2021). Whitewashing: How obama used implicit racial cues as a defense against political rumors. Polit. Behav. 43, 1337–1360. doi: 10.1007/s11109-020-09642-1

Inglehart, R., and Norris, P. (2003). Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511550362

Jost, J. T., and Kay, A. C. (2005). Exposure to benevolent sexism and complementary gender stereotypes: consequences for specific and diffuse forms of system justification. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 88, 498. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.498

Krook, M. L., and O'Brien, D. Z. (2012). All the president's men? The appointment of female cabinet ministers worldwide. J. Polit. 74, 840–855. doi: 10.1017/S0022381612000382

Lazarus, J., and Steigerwalt, A. (2018). Gendered Vulnerability: How Women Work Harder to Stay in Office. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.9718595

Lefkofridi, Z., Giger, N., and Holli, A. M. (2019). When all parties nominate women: the role of political gender stereotypes in voters' choices. Polit. Gender 15, 746–772. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X18000454

Linos, K., and West, M. (2003). Self-interest, social beliefs, and attitudes to redistribution. Re-addressing the issue of cross-national variation. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 19, 393–409. doi: 10.1093/esr/19.4.393

Lizotte, M. K. (2017). Gender differences in support for torture. J. Conflict Resol. 61, 772–787. doi: 10.1177/0022002715595698

Lizotte, M. K. (2019). Investigating the origins of the gender gap in support for war. Polit. Stud. Rev. 17, 124–135. doi: 10.1177/1478929917699416

Mansfield, E. D., and Mutz, D. C. (2009). Support for free trade: self-interest, sociotropic politics, and out-group anxiety. Int. Organ. 63, 425–457. doi: 10.1017/S0020818309090158

Morgan, J., and Buice, M. (2013). Latin American attitudes toward women in politics: the influence of elite cues, female advancement, and individual characteristics. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 107, 644–662. doi: 10.1017/S0003055413000385

Ondercin, H. L. (2017). Who is responsible for the gender gap? The dynamics of men's and women?s democratic macropartisanship, 1950?2012. Political Research Quarterly, 70, 749–761. doi: 10.1177/1065912917716336

Ondercin, H. L. (2018). “Is it a Chasm? Is it a Canyon? No, it is the Gender Gap.” The Forums. 16. doi: 10.1515/for-2018-0040

Pansardi, P., and Vercesi, M. (2017). Party gate-keeping and women's appointment to parliamentary committees: evidence from the Italian case. Parliam. Aff. 70, 62–83. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsv066

Reynolds, A. (1999). Women in the legislatures and executives of the world: knocking at the highest glass ceiling. World Polit. 51, 547–572. doi: 10.1017/S0043887100009254

Roberts, D., and Utych, S. (2022). A delicate hand or two-fisted aggression? How gendered language influences candidate perceptions. Am. Polit. Res. 50, 353–365. doi: 10.1177/1532673X211064884

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2002). Gender stereotypes and vote choice. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 46, 20–34. doi: 10.2307/3088412

Sanbonmatsu, K., and Dolan, K. (2009). Do gender stereotypes transcend party? Polit. Res. Q. 62, 485–494. doi: 10.1177/1065912908322416

Schaffner, B. F., MacWilliams, M., and Nteta, T. (2018). Understanding white polarization in the 2016 vote for president: the sobering role of racism and sexism. Polit. Sci. Q. 133, 9–34. doi: 10.1002/polq.12737

Schlesinger, M., and Heldman, C. (2001). Gender gap or gender gaps? New perspectives on support for government action and policies. J. Polit. 63, 59–92. doi: 10.1111/0022-3816.00059

Schneider, M. C., and Bos, A. L. (2019). The application of social role theory to the study of gender in politics. Polit. Psychol. 40, 173–213. doi: 10.1111/pops.12573

Siaroff, A. (2000). Women's representation in legislatures and cabinets in industrial democracies. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 21, 197–215. doi: 10.1177/0192512100212005

Swigger, N., and Meyer, M. (2019). Gender essentialism and responses to candidates' messages. Polit. Psychol. 40, 719–738. doi: 10.1111/pops.12556

Weeks, A. C., Meguid, B. M., Kittilson, M. C., and Coffé, H. (2022). When do Männerparteien elect women? Radical right populist parties and strategic descriptive representation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1–18. doi: 10.1017/S0003055422000107

Keywords: sexism, policy attitudes, government spending, gender, surveys, Australia, United States

Citation: Beauregard K, Holman M and Sheppard J (2022) Sexism and Attitudes Toward Policy Spending in Australia and the United States. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:892111. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.892111

Received: 08 March 2022; Accepted: 28 April 2022;

Published: 27 May 2022.

Edited by:

Hilde Coffe, University of Bath, United KingdomReviewed by:

Lotte Hargrave, University College London, United KingdomRosalind Shorrocks, The University of Manchester, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Beauregard, Holman and Sheppard. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mirya Holman, bWhvbG1hbkB0dWxhbmUuZWR1

Katrine Beauregard

Katrine Beauregard Mirya Holman

Mirya Holman Jill Sheppard

Jill Sheppard