94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 20 June 2022

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.885892

This article is part of the Research Topic Resilient Cities and Migration Governance View all 5 articles

The dramatic event that the great migration in the summer of 2015 entailed changed the migration policies of various countries. Substantial amendments were hastily made in a policy field in which already tense state-local relations struggled to manage coordination, responsibilities, and funding. Sweden, recognized as a final host country of the massive flows of refugees and asylum-seekers, was no exception. In Sweden, autonomy in terms of local refugee reception was circumvented in 2016. Municipalities' remaining discretion is above all concentrated to one of the most crucial spheres of refugee reception: the outline of local housing policies. We argue that housing may be perceived as a tool of resilience that local governments may use to maintain far-reaching influence over the settlement of migrants with a refugee background by selecting restrictive or generous policy options. In this paper, we conduct a theoretically grounded analysis of local housing policy for refugees among Swedish municipalities. To capture the intrinsic dynamic, we propose a generic typology applying the dimension of either a liberal or a restrictive housing policy and relate it to theoretical notions of refugee policy as characterized by either a rights-based or a more restrictive approach. Our findings show that local governments in Sweden pursue a wide array of policy stances that appear to be correlated with factors originating from prior experiences of refugee reception, conditions in the labor and housing markets, and political circumstances. Based on this, we argue that local housing policy has offered municipalities a tool to exert a form of intentional, or unintentional, migration control despite national efforts to impose a more just system of refugee reception.

The outbreak of the war in Ukraine in February 2022 has once more highlighted the challenges of nation-states and local governments connected to the provision of housing for refugees. These challenges do not constitute a new phenomenon but since the great migration in the summer of 2015, more attention have been directed toward refugee reception in what we argue is an ongoing housing crisis. In the current housing crisis, the main emphasis no longer revolves around controlling the great flows of asylum-seekers but to provide sustainable housing situations, i.e., tenure security, territorial access, and opportunities for participation, for those granted protection in times of mass displacement. Yet, the political will and the capacities to provide housing for migrants, already in the bottom of the social hierarchy, differs both nationally and locally. Therefore, using the concept of resilience, we seek to understand and describe how municipalities autonomously construct local housing policies to maintain, adapt, or even prevent the long-term settlement of migrants with a refugee background. Although several of the recent amendments in migration policies have been enforced at the national level, they have further altered domestic policy in which already tense state-local relations struggle to manage coordination, responsibilities, and funding related to refugee reception and settlement (Gammeltoft-Hansen and Tan, 2017; Hernes, 2018; Hagelund, 2020; Lidén and Nyhlén, 2022). Hence, the research community has shown a growing interest in examining if and to what extent national policy initiatives have trickled down to local governments (Filomeno, 2017; Zapata-Barrero et al., 2017).

In this article, we follow the local turn by providing a description of municipal housing policy in Sweden. Sweden is an interesting case, as the country, after Germany, approved the highest number of asylum claims in 2015 (and the highest number if counted per 100,000 inhabitants) (Eurostat, 2022). We argue that housing, besides its central role in the process of settlement and inclusion, can be perceived as a tool of resilience that local governments may use to maintain far-reaching influence over the settlement of migrants with a refugee background by choosing between restrictive and generous policy options1. Following this line of argument, we contribute with an empirical investigation of how post-entry instruments, often defined as integration policy, can be exploited to either restrict or facilitate access to a place or a territory (e.g., Hammar, 1985). Housing is a particularly interesting area in this regard and part of a more boundless policy that may attract or exclude new and already admitted citizens in the country, as popularized through movements of welcoming or sanctuary cities (Huang and Liu, 2018; McDaniel et al., 2019). Thus, besides the view of housing as one of several equivalent aspects of socio-economic integration (Penninx and Garcés-Mascareñas, 2016), this paper suggests that it may be exploited as a policy instrument to uphold intentional or unintentional migration control. We further argue that the role of local housing policy for migration control can be relevant to other countries as well as for deepening our understanding of the integration process and what helps or hinders individual migrants' resilience.

The different policy options chosen by local governments cannot easily be explained through a continuum ranging from liberal to restrictive policy. In this paper, we thus raise the question regarding the characterization of different policy options for local governments in terms of housing policy for refugees. To do this, we contribute with a novel typology that advances in different stages. First, it distinguishes the most restrictive policy option from a more generous one. Second, it captures the remaining complexity by inserting two dimensions: the temporal viewpoint on housing and the stated requirements for gaining access to housing. This typology is thereby based on the notions of refugee housing policy as characterized by either a rights-based or a more restrictive approach, the latter emphasizing individual responsibilities as a precondition for inclusion. In a second step, we use the constructed typology to address the question of which factors influence the observed variation. Our findings show that local governments in Sweden pursue a wide variety of policy stances that are correlated with factors such as prior experiences of refugee reception, conditions in labor and housing markets, as well as political circumstances.

We further motivate our focus on Sweden by the recent changes in its domestic national migration policies. Besides significant restrictions regarding the possibility to obtain a permanent residence status (Jutvik, 2020a), municipal autonomy was circumvented since refugees after their admission to Sweden are dispersed through a specific distribution model and no longer according to negotiated quotas potentially reflecting local ambitions. This is regulated through the 2016 Settlement Act with clear dispersal aims and an ambition to reach a more equal reception of refugees among local governments (Hudson et al., 2021). In this regard, Sweden is a particularly interesting case to study as municipalities have limited influence over the local number of admitted refugees but far-reaching autonomy to develop other related welfare services, such as the structure of housing.

The study proceeds as follow: In the following section, the background and regulation of the Swedish migration regime are described, in terms of both integration and housing policy. Thereafter, a review of previous research on local integration policy, particularly focusing on housing policy, is presented. This is followed by a theoretical discussion on how different policies in refugee research are based on contrasting notions of refugees. This kind of theoretical analysis enables us to disentangle two main standpoints. Next section consists of a presentation of the research design and data applied. Following this section, an empirical description of municipal variation in refugee housing policy is provided, which also includes a presentation of the methods applied. A joint analysis is then presented of the theoretical and empirical elements, followed by conclusions.

Swedish municipalities appear as key actors in the formation of refugee reception. As early as 1985, the admission of refugees was made into a local issue, in which the government established agreements with municipalities for placing refugees (Borevi, 2012; Qvist, 2012). Nevertheless, the distribution of refugees throughout Swedish municipalities has been highly debated. This system, with agreements based on negotiations and bargaining between government actors and local governments, created a significant variation from one municipality to another (Lidén and Nyhlén, 2014). The system was partly maintained by the municipalities' sense of solidarity with each other (Qvist, 2012). This model of agreements between the government and municipalities was in place until 2016, when the voluntary part of the system was replaced by the Settlement Act.

With the implementation of the Settlement Act, the Swedish Migration Agency (SMA) organizes the process for immigrants, including asylum seekers. During the asylum process, the SMA provides housing (ABO, “anläggningsboende” in Swedish)2. When a refugee receives a temporary or permanent residence permit, the SMA assigns the individual to a municipality (frequently not the same municipality where the migrant stayed during his or her asylum process). The municipality is then obliged to provide for the newly arrived individual and arrange housing, language training, and civic education during an establishment period of 2 years. Following the above, municipalities are no longer able to refrain from receiving refugees unless this is the outcome of the distribution model3.

Most countries have national housing policies but over time there have been an increased focus in most western countries on local solutions and local housing policies (Granath Hansson, 2017). In Sweden, municipalities have a monopoly on planning and are responsible for providing housing. Swedish housing policy is typically categorized as universal, where no housing tenure is reserved for a single category (i.e., it lacks an element of social housing). Most municipalities instead have a municipality-owned housing company (often referred to as public housing) (Holmqvist and Magnusson Turner, 2014). In general, allocation is made on the basis of time in housing queues (waiting lists) and not need. A major obstacle for Swedish municipalities today is housing shortage, as 83% of all municipalities reported a general housing deficit (National Board of Housing, Building and Planning (NBHBP), 2021). Mostly, there is a shortage of rental accommodation. The strained housing situations have particularly affected newly arrived refugees. During the 2020s, an overwhelming majority of municipalities estimate that they face a housing deficit with regard to this group. These kinds of contextual conditions may have an impact on local policy stances. When the new Settlement Act was implemented, the government thus imposed a bonus for municipalities receiving refugees if they also built new housing. This is seen as compensation for housing shortage problems in relation to refugee reception (Swedish Association of Local Authorities Regions, 2019b). Before the new Settlement Act, housing shortage was often an argument for only accepting a low number of refugees (Lidén and Nyhlén, 2022). As stated above, municipalities apply various policies when it comes to housing both during these first 2 years (called the establishment period) and after (County Administrative Board in Stockholm, 2020; Grange and Björling, 2020). General descriptions of this variation show that these policies are not evenly distributed throughout the country.

In line with the aspiration of this study, we departure from three related strands of literature. We discuss in turn (i) the role of local governments in pursuing migration and integration policies (ii) the local appliance of integration policies as a way to regulate inflow of migrants (iii) how local migration issues can be viewed from the theoretical perspective of resilience. Although the common denominator is the local perspective on migration issues—expanded through how knowledge from resilience can be applicable as a vital perspective to address unexpected events of migration and displacement—the question of housing is similarly brought to the core. In a final discussion, we expand on these three stands inherent relation with each other.

First, an expanding literature has come to examine the role of the local political arena in the development of their own migration and integration policy. This narrative is closely related to the emerging perception that these political entities are becoming more active actors than what has previously been acknowledged (Filomeno, 2017; Myrberg, 2017; Zapata-Barrero et al., 2017). Recently, several studies have focused on the role of local governments. For example, in surveys and case studies of local European governments conducted by the OECD (2018), it is evident that only slightly more than half the cases have adopted local strategies within this domain. Furthermore, European scholars have looked closer into such city activities, noticing that both motives originate from contesting ideological positions (Martínez-Ariño et al., 2019; Zuber, 2019) as well as structural and institutional conditions (Schammann et al., 2021). Further analyzing the subnational activation particularly in relation to housing, Meer et al. (2021) apply a governance perspective and examine urban areas in Italy, Sweden, Scotland, and Cyprus in terms of housing and accommodation for refugees. Findings state that local governments are crucial in the delivery of long-term settlement, often jointly with civil society, and that the Swedish situation, with a more centralized policy, has had an impact on housing issues. It is observed that this has meant greater differentiation regarding housing conditions at the local level and that examined cases in Sweden struggle to reach long-term solutions for received refugees. Myrberg and Westin (2016) show that the local housing market constitutes a significant challenge when it comes to receiving refugees. Søholt and Aasland (2021) showed how Norwegian municipalities also refrained from accepting refugees by referring to housing shortage, but how the increased need in 2015 made many municipalities more open to settle immigrants. However, fewer studies have explicitly focused on presenting a detailed description of the variation in housing at the local level. Two regional studies are exceptions (County Administrative Board in Stockholm, 2020; Grange and Björling, 2020), which describe a variation in reception and housing policy with regard to the regions of Stockholm and Gothenburg. A new study by Emilsson and Öberg (2021) find the same results, that the dispersal policy of refugees that aims at a more equal distribution among municipalities leads to inequalities at local level for refugees. One of the contributions of our study to the current state of research is a national overview of the variation in reception strategies and the role of housing policies at the local level.

The second strand concerns how local governments turn to traditional integration policy to either prevent or attract newcomers to reach the community. In line with Hammar (1985) notable distinction, traditional socio-economic integration efforts may also serve as an element that could ultimately decide who can be a long-term resident. Access to long-term settlement in a municipality and integration outcomes are thus not solely affected by policies aiming at direct migration control but also by other types of policy, such as housing regulations. This challenges prior notions of housing policy merely being one of several aspects of socio-economic integration (Penninx and Garcés-Mascareñas, 2016). As indicated by several authors (Phillips, 2006; Meer et al., 2021; for a review see Brown et al., 2022), accommodation can easily be used as an obstacle to integration, in which local governments pursue different strategies, including maintain housing of poor quality and only allowing it temporary. Considering that housing policy, in relation to other aspects, such as policies for facilitating employment, education, and health care, is even more of a basic criterion, its decisive dimension is underlined. Without policies that actually enable housing for refugees, the others will not be activated. Sufficient housing conditions are associated with several positive values, such as physical and emotional wellbeing, and are related to other dimensions of a successful integration process, such as possibilities for education and establishment in the labor market (Ager and Strang, 2008; Holmqvist et al., 2020; Sandström, 2020).

As a third field of interest, the concept of resilience, firstly used in psychology at individual and community level and then in ecology, has later been used in planning and politics to describe a city capacity to cope, adapt, recover, and even prevent effects from sudden stressful changes, often referring to climate change (Stumpp, 2013). More recently, however, migration and mass displacement have also been used as examples of shocks that nations and cities can be more or less resilient against (Bourbeau, 2015; Rast et al., 2020). A major critique of the resilience approach is that it can be used in a neoliberal model (Cretney, 2014) to decrease the “needy population” (Preston et al., 2021). Prokkola (2021) argues that protecting borders is done in the name of resilience to safeguard the carrying capacity of a state. The same line of argument is found for EU, using resilience to keep refugees from Syria outside the EU by giving neighboring countries as Jordan and Libanon aid (Anholt and Sinatti, 2020). We argue, in line with Ahouga (2018) that welcoming and blocking strategies could also be found at a city level, and cities may adopt a resilience argument as to who is to become a long-term resident. Søholt et al. (2018) found that rural areas in Norway, struggling with decreasing populations, used resilience as argument for increased immigration. These differences and trends could be seen in relation to the literature on welcoming cities, where the local government has adopted an inclusive approach to newcomers as well as immigrants (Huang and Liu, 2018; Turam, 2021).

Research on social resilience has highlighted the importance of local institutions and local contexts in facilitating an integration process of newly arrived migrants. These institutions are seen as key in the formation of welcoming cities. In this paper, we argue, in line with Preston et al. (2021), that local institutions are key for the ability of newcomers to become integrated into a new place, and that social resilience can be used to understand the role of institutions and local policies for the trajectories of migrants. Here, we focus on the role of local housing policy and housing context with regard to integration. While the concept of social resilience stresses integration as a two-way process, where the institutions assist migrants to overcome challenges, the more neoliberal use of resilience stresses that migrants should “settle on less”, where the individual is supposed to be more self-sufficient (Hall and Lamont, 2013; Preston et al., 2021). In line with this, we argue that the different housing models used by municipalities may be understood as the difference between housing as a basic right (provided by state/local institutions) and housing as a reward (individually obtained) after having accomplished integration in other spheres, such as the labor market.

Thus, departing from the three strands of literature above, our paper contributes with a theoretically grounded overview of local housing policy after 2016. In an additional contribution, we connect the policy variations to the concept of resilience and discuss the implications of our finding to the understanding of state-local relations as well as national ambitions to develop an equal refugee reception at the local level. In the next section, we turn to outline the foundations for the typology of housing policy for refugees.

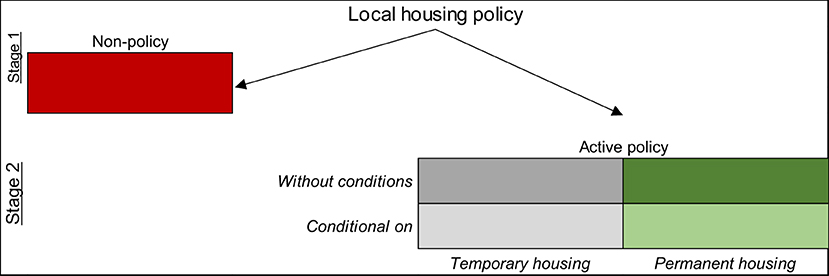

Our outlined typology is based on several dynamic elements visualized in Figure 1. In the first stage, it separates the local governments maintaining a minimalistic policy or refraining from maintaining a policy in this area (non-policy) from those having implemented an active policy. The distinction of non-policy and active policy has been widely applied in the field of migration (e.g., Williamson, 2018; Lidén and Nyhlén, 2022) and represents a parsimonious conceptualization in which the abstention of policy can generally be described as “…the municipality turns a blind eye to the problem” (Alexander, 2007, p. 41).

Figure 1. The figure displays two stages: 1) municipalities that maintain a minimalistic or non-policy and 2) municipalities that maintain an active policy. In the second stage, there are four outcomes in the form of a typology. The typology is based on two axes: outcomes of housing policy granted without conditions or requiring certain conditions and housing assured of a temporary or permanent nature.

In a second stage, accounting for the municipalities that maintain an active housing policy for refugees, distinctions are made based on two axes consisting of a rights- and responsibility-based dimension and a temporal dimension. Concerning the first axis, scholars have pointed to opposing approaches and logics that may permeate migration policy: a rights-based (without conditions) and a more responsibility-based approach (conditional on) (Borevi, 2010). Inspired by Marshall's (1950) seminal work, the rights-based approach suggests that equal access to civil, political, and social rights is a necessary condition for achieving successful integration. What facilitates refugee integration is thus rights, such as the provision of somewhere to reside, the opportunity to participate in the democratic sphere, or access to welfare. Quite the opposite, responsibility-based approaches argue that refugees should be given limited access and that only those succeeding in pre-stipulated areas of integration, such as integration into the housing market, the job market, or social life (such as culture and language), should be given additional access to welfare services (e.g., Koopmans, 2010). In comparison to the rights-based approach, what here pushes individuals to become integrated is instead requirements and conditions related to access. In the contemporary restrictive trend in migration policy, there is a general focus on individual responsibilities, quite the opposite of the Marshallian theory (Borevi, 2010, p. 27). Yet, it is unclear whether local governments have followed this trend regarding housing policy or whether they have attempted to circumvent or reinforce the (restrictive) policies by implementing unique local policies (Dekker et al., 2015).

Housing policy permeated by the above logics thus involves different ideas concerning the drivers of integration. When housing is viewed as a right, the implication is that housing is seen as the foundation for the process of integration (comparable to so-called housing first models for addressing homelessness). Thus, it is only when housing is in place that the refugee is equipped to move forward in the process of integration in other spheres (e.g., the labor market). When housing is formalized as a responsibility, the integration process does not start with a stable home but ends with this after specific criteria have been fulfilled. The refugee must then be established in order to find housing and a stable home. For example, a refugee must first learn Swedish to secure a job, which will give merits, such as sufficient income or employment status, to ensure a first-hand contract with a public or private landlord.

The second axis concerns the temporal aspect of housing policy being perceived as either temporary or permanent. This axis thus makes a distinction between a policy stipulating temporary housing solutions and a policy without such limitations. Again, housing policy permeated by these temporal differences may indicate differing ideas regarding the facilitators of integration. A permanent housing contract indicates a welcoming stance, offering a permanent base, and a potential end to the migratory process. Temporary housing contracts, on the other hand, signal that the migratory process is not over but that the offered housing is merely a sanctuary for a limited time. This stance is also closely related to a responsibility-based approach in which permanent housing is only available for those who fulfill certain criteria.

To address the second research question and provide empirical examples for the constructed typology, this study draws on data from a Swedish public authority, the National Board of Housing, Building and Planning (NBHBP), which covers the years of 2019 and 2020. The data displayed is collected through a yearly survey distributed to all municipalities. In the survey, questions are asked concerning the housing market in the municipality, but it also includes questions seeking to determine local policies regarding refugee housing. Although it could be seen as a threat to validity that specific officials in each municipality answer the survey and that it thereby does not reflect hard data, the County Administrative Board in each region is responsible for ensuring the accuracy of the responses provided by the municipalities.

Of specific interest for this study is a question in the NBHBP survey examining the time perspective in municipal settlement of refugees. It is phrased as which time perspective is used by the municipality in the settlement of assigned newly arrived refugees? A number of fixed answers are provided that reflect the situation concerning housing contracts for individual refugees. The supplied alternatives can be divided along the same dimensions as the typology. First, answers are divided based on whether municipalities maintain a long-term housing policy or whether the municipalities refrain from having any such policy. Second, the character of long-term policies is defined further based on their temporal aspects and whether or not they formulate certain requirements for the individual. Basing the analysis on this enables us to determine the results of municipal policies.

Drawing on this data does come with a few caveats. The first problem includes the possibility for responding municipalities to provide more than one option. Hence, this raises coding problems, and we employ several strategies to circumvent these. We either display complete answers given by the municipalities or, when settling with one answer given per municipality, we select the most restrictive option. The first alternative is applied for ensuring that we can display an overview of the situation in Sweden. The second option is preferred in analyses when one classification per municipality is necessary.

To ensure high validity in the coding, we also compare results from the NBHBP survey with a similar survey, conducted by the County Administrative Boards (County Administrative Board in Jönköping, 2019, 2020). When coding the answers given in the NBHBP survey, they are ordered based on how the most restrictive alternative given by the municipality is placed on a continuum from restrictive to liberal policy. This enables comparisons with the survey of the County Administrative Board following this scale. Correlation statistics imply satisfactory congruence between the two surveys (0.67 in 2019 and 0.64 in 2020). Further details are provided in Figure A1 of Appendix.

There are problems with missing data in the empirical analysis. As stated above, we have prioritized ensuring high validity in the transformation of survey answers to the theoretically grounded typology. An analysis of the non-respondents shows that this group primarily consists of smaller municipalities with fewer than 25,000 inhabitants in the data for 2019 as well as 2020. For a detailed view, see Tables A1, A2 in the Appendix.

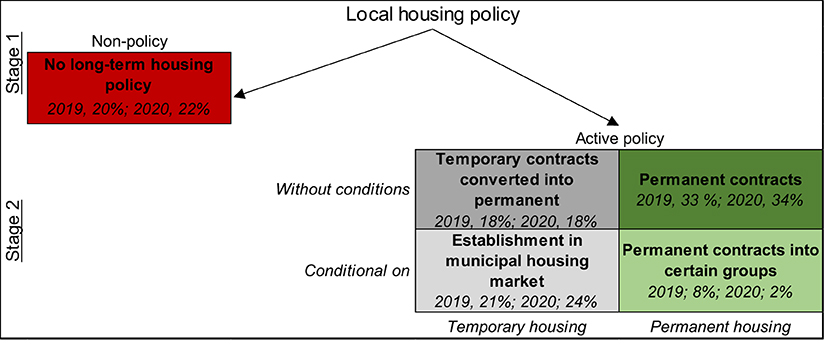

We now turn to the empirical section of this study. This empirical presentation is facilitated by an illustration capturing various municipal outcomes in this matter, see Figure 2.

Figure 2. The figure displays two stages: 1) municipalities that maintain a minimalistic or non-policy and 2) municipalities that maintain an active policy. In the second stage, there are four outcomes in the form of a typology. The typology draws on two axes: outcomes of housing policy granted without conditions or requiring certain conditions and assured housing being temporary or permanent in nature. Data on housing policy from National Board of Housing, Building and Planning (NBHBP) (2020, 2021).

The figure adds empirical substance to the theoretically derived typology. The demarcation point for the first stage concerns whether municipalities maintain an active or minimalistic policy in this area. In this position, we find municipalities only providing housing during the establishment period (i.e., they uphold responsibility for housing only during the first 2 years). Individuals are thereafter directed to the general housing market in Sweden. This policy category may push individuals with few resources to move to less attractive segments of the housing and labor market and thus lose the social contacts and networks they have developed during the establishment period. Hence, municipalities having adopted this housing policy have interpreted the Settlement Act in a minimalistic way, acknowledging responsibility for housing only during the initial time of settlement.

The opposite alternative entails a situation in which municipalities pursue an active housing policy, compromising four different outcomes, in the form of a typology. This typology is based on two axes: outcomes of housing policy granted without conditions or requiring certain conditions and assured housing being temporary or permanent in nature.

A position on the left side of the typology indicates an interpretation of temporary responsibility and may be either conditional or unconditional for the individual. The bottom-left box of the typology represents a policy type stipulating the provision of temporary contracts that remain in place until the individual has managed to establish him- or herself in the municipal housing market by, for instance, accumulating average time in the local housing queue or arranging a second-hand contract. Importantly, apart from the challenges to obtain housing, this category further demands integration into the labor market to meet the financial requirements often stipulated by private and public landlords. The second temporary option in the top-left box constitutes a policy with initial temporary housing contracts that are converted into permanent housing without any form of quid pro quo. Although the temporary contract will be converted into a permanent solution without conditions, from the perspective of the individual, the initial time may be perceived as a period of evaluation and, in combination with the short duration of the temporary residence permits granted (13 months or 3 years), as a time of uncertainty.

A position on the right side indicates an interpretation of long-term responsibility with or without conditions. The bottom-right box represents a policy in which certain groups are offered permanent housing while other groups are offered temporary housing. This policy thus identifies specific vulnerable or “deserving” groups that are to be exempt from the general housing policy. Empirically, these exceptions often concern families with children under the age of 18, which are offered first-hand contracts. The stance presented in the top-right box represents a policy in which refugees are given the possibility to sign a permanent housing contract without certain requirements already at the beginning of a reception process in a municipality.

In addition to capturing a procedural perspective of local housing policy, Figure 2 also contains a summary of municipal responses according to the annual survey managed by the NBHBP, covering the situation in both 2019 and 2020. As displayed in the figure, most Swedish municipalities maintain an active housing policy. There was still a substantial portion completely refraining from doing so and they have thus interpreted the Settlement Act in a minimalistic manner. Among the municipalities upholding some kind of policy, about the same portion settled on temporary as well as permanent housing contracts for refugees. The single most used option was the one granting individuals permanent housing contracts. Less common was to stipulate certain conditions that must be fulfilled. Quite common alternatives also included pursuing a line of temporary housing. More or less the same number of municipalities maintained such policies without further conditions as the number of municipalities requiring that individuals tried to establish themselves in the housing market. As already stated, municipalities were given the possibility to present several responses in the survey, which explains questions concerning the sums of proportions.

By using the distinction made in Figure 2, we now turn to illustrate the current situation of 2020, see Figures 3A–E. We present this in different stages and provide a more granular presentation in the counties harboring the Swedish metropolitan areas. Throughout this section, we now turn to classify municipalities based on the most restrictive options given.

Figure 3. (A) Displays housing policy in the first stage and visualizes municipalities that do not maintain, or maintain, a long-term housing policy. (B) Displays the same map but adds a more detailed view from stage 2. (C–E) Display housing policy in the three largest counties in Sweden: Stockholm, Skåne, and Västra götaland. Data from National Board of Housing, Building and Planning (NBHBP) (2021).

In the map on the left-hand side, the two outmost alternatives of policy stances are highlighted, indicating whether municipalities refrain from maintaining a long-term housing policy or whether they pursue the most liberal version of such policies—granting permanent housing without conditions. All other municipalities are lumped together and colored white. As seen in the map, it is evident that more municipalities pursue the most liberal policy compared to those lacking a long-term policy. While the liberal municipalities are scattered across the country, with the exception of the greater Stockholm area, the restrictive municipalities are more concentrated. Few of the cases in the latter group are located in the northern part of Sweden, while they are apparently more frequent in the areas in or close to the metropolitan regions.

In the second map from the left, all five outcomes from the typology are visible. This illustration juxtaposes municipalities with a minimalistic policy with those maintaining a temporary or permanent policy. As already noticed, municipalities lacking a long-term housing policy for refugees are predominantly concentrated in the metropolitan areas of the country. Even if a few other examples exist, they constitute deviating cases rather than representing any other pattern. The two categories representing temporary housing for refugees are scattered all over the country. However, there is a tendency in terms of their particular concentration in the metropolitan areas thereby aligning with the local governments having abstained from pursuing local housing policy. At the other end, municipalities ensuring refugees permanent housing, either after requiring certain conditions or not, are also found all over the country with the exception of the region surrounding Stockholm. An observed tendency is that the municipalities pursuing permanent housing policies are predominantly found in hinterland municipalities in the south and middle part of Sweden and that they are generally well-represented in the northern part of the country.

In the remaining three maps to the right, a more detailed focus is provided by displaying the counties of Stockholm, Västra Götaland, and Skåne. The three metropolitan areas of Sweden are gathered in these counties through the city of Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö, respectively. Starting with the municipalities of the county of Stockholm, they are to a large extent uniform in their absence of granting a long-term housing policy. In fact, the 20 municipalities in the region adopting this policy stance make up the most united proportion of all municipalities in Sweden taking this decision. The remaining three municipalities have instead settled for a temporary policy requiring that certain conditions are met (cf. County Administrative Board in Stockholm, 2020). Turning to the county of Västra Götaland and the Gothenburg region, it is evident that the situation is much more diverse. The county contains municipalities upholding a variety of policy stances, making the distribution quite similar to the country as a whole (cf. Grange and Björling, 2020). Finally, the county of Skåne is displayed. Including municipalities with various policy outcomes, the tendency is still leaning toward the more restrictive end of the spectrum. Thus, there are only a handful of municipalities granting a permanent housing policy while the more frequent stances are found across municipalities with a complete lack of a long-term policy or those upholding a temporary alternative. This closer look makes it possible to classify the county of Stockholm (Figure 3C) as the absolutely most restrictive among the three counties while the county of Västra Götaland (Figure 3E) represents a balance closer to the national average. The county of Skåne (Figure 3D) can be placed in an intermediate position somewhere between the other two counties.

In this section, we take a closer look at policy options across Swedish municipalities by adding variables that could reveal patterns influencing the outcomes. More precision is achieved by contrasting the policy stances in 2020 with a set of variables measured 1 or 2 years prior used for the characterization of municipalities, see Tables 1–3.

Although the tendency for the metropolitan areas to pursue a more restrictive form of local housing policy has already been noted, Table 1 adds details. We clearly see that it is much more common among municipalities in other regions of the country to maintain a more liberal policy compared to local governments in metropolitan areas.

The most common motive expressed by municipalities pursuing a more restrictive policy for refugees is the one related to housing shortages (Lidén and Nyhlén, 2022). As seen in Table 2 applying comparisons of means, there are reasons to at least partly verify this statement. There is more rental housing in municipalities maintaining a liberal policy compared with their more restrictive counterparts. A similar tendency is also noticed when looking at the extent of public housing in municipalities. However, the variation is not linear, illustrated by how the municipalities giving permanent contracts only to certain groups appear to have better conditions for a generous housing policy than those ensuring permanent contracts for everyone. The variable reflecting the share of available apartments among public housing companies corresponds to the expected pattern. There are, in general, substantially fewer available public housing apartments in the municipalities upholding a more restrictive policy than in municipalities granting permanent contracts.

It could be assumed that the prior experience of refugee reception will have repercussions also on how municipalities choose to outline their housing policy for the very same group. This argument is based on a logic that various policies in this area are seldom seen as isolated from each other (Filindra and Goodman, 2019). To examine this, we draw on data from the period before the Settlement Act, during which municipalities had influence over the magnitude of their reception. Even if this analysis presented in Table 2 yields no complete linearity over the categories, the pattern is still convincing. In general, municipalities refraining from having a long-term housing policy have also historically exhibited the most limited reception of refugees. Among municipalities giving temporary contracts to all refugees or ensuring permanent contracts, the average admission of refugees has been significantly higher.

Previous research has highlighted the paradox of refugee reception being particularly frequent in areas where conditions in the local labor market are particularly bleak (e.g., Wennström and Öner, 2015). A similar pattern is also found when substituting refugee reception with local housing policy for the same group, see Table 2. Hence, the municipalities harboring the labor markets with the lowest unemployment levels paradoxically present the most challenging conditions for refugees to remain within the premises of the municipality. On the contrary, generous housing conditions are granted in municipalities in which the local labor market is more challenging. Recent research has emphasized that the most advantageous regions for former refuges to find employment are either in the metropolitan Stockholm region or smaller cities and rural regions (Vogiazides and Mondani, 2020).

In a final characterization of patterns of local housing policy, political variables are exploited, measuring whether the local government is ruled by left- or right-wing coalitions, see Table 3. Prior studies both from European countries (Bolin et al., 2014; Jutvik, 2020b) and from the US (Walker and Leitner, 2011; Gulasekaram and Ramakrishnan, 2015) have reported that political factors influence policy outputs in the area of migration. The pattern is clear. All municipalities lacking a long-term housing policy are governed by right-wing or mixed coalitions. However, all forms of local government are represented among municipalities more prone to maintain long-term policies.

The contemporary era of mass displacement, most recently caused by the war in Ukraine in February 2022, has resulted in an ongoing and urgent housing crisis for those that flee violence and persecution (cf. Brown et al., 2022). We have therefore used the concept of resilience to describe how local housing policies can be used as a tool to maintain, adapt, or even prevent the long-term settlement of migrants with a refugee background at the local level. We have done so by performing a theoretically grounded analysis of different policy stances in Sweden following the implementation of the 2016 Settlement Act.

Our contribution is both theoretical and empirical in nature. First, with the help of dimensions reflecting views on conditionality, on the one hand, and temporal assessments, on the other, we have constructed a typology outlining theoretical foundations for the understanding of variations in outcome of local policy choices. Second, in terms of an empirical contribution, we demonstrate that housing policies targeted at refugees differ at the local level in Sweden when adding data to the theoretical perspectives. Importantly, we describe a large variation in housing policy from restrictive to more liberal strategies. Hence, we meet the aspirations of our first research question in providing a characterization of how different policy options are singled out across local governments. In relation to our second research question, on the factors influencing this variation, this study has shown that these policy stances are associated with specific types of municipalities, housing markets, prior experiences, and political ideologies. With these contributions in mind, there are at least three implications to consider.

First, discretion in local housing policy has enabled municipalities to circumvent the aims of the national directives, the Settlement Act, to facilitate a fair distribution of refugees granted residence via housing policy (Lidén and Nyhlén, 2022). We have shown that the municipalities that received the fewest number of refugees before the implementation of the dispersal policy have also implemented the most restrictive housing policies post-2016. From a social resilience perspective, though, our results show how municipalities have gone to any length to stretch the current legislation. By referring to the importance of local context and local institutions, like public housing, decisions have been reached regarding the long-term settlement of refugees. As refugees and households with more strained finances are more common in the public rental sector, keeping public rental properties at a minimum level could also be interpreted as a strategy to keep the number of more precarious households in the municipality at a minimum (see, for example, Baeten and Listerborn, 2015), which calls for caution when interpreting causality regarding housing shortages. In this respect, some municipalities have shown great resilience in maintaining a stance toward refugee inflow via housing policies. Resilience is here interpreted in a more neoliberal way, where status quo is maintained. Therefore, although the initial distribution of refugee reception may be fairer and more even after 2016, old patterns of migratory patterns have prevailed, in which long-term settlement continues to be difficult, or even impossible, in some municipalities.

Second, from an integration point of view, we have shown a mismatch between the possibilities to obtain secure housing and favorable conditions to be included. From a policy perspective, our results highlight a current mismatch in the Swedish reception system in which permanent housing is often given in contexts with weak labor markets (cf. Wennström and Öner, 2015). On the contrary, in the larger cities with stronger labor markets, temporary housing solutions are offered. The various outcomes of housing policy that we reveal imply that local governments perceive their capacity and utility of maintaining long-term settlement for refugees differently. However, such interpretations are not always in concordance with relevant conditions. Our description indicates that permanent housing is given in smaller municipalities less able to facilitate, for instance, a successful labor market integration. As an example, temporary housing contracts are more common in municipalities with strong labor markets and vice versa. On an individual level, having a strong and stable position in the labor market is crucial, as this is currently a requirement for obtaining a permanent residency permit in Sweden. As a policy recommendation, we thus suggest combining permanent housing with strong labor markets and not the other way around.

Third and importantly, the structure of housing policy for immigrants with a refugee background provides municipalities with a tool to exert a form of intentional, or unintentional, migration and local border control. This should be seen in the light of local level initiatives also being the arena where long-term solutions for refugees most easily can be achieved (Meer et al., 2021). We have pointed to different housing policy stances regarding more or less secure forms of tenure. The local policy stances may be related to lacking resources (intentionally or unintentionally) or previous decisions regarding housing or refugee settlement. However, we have shown that a restrictive housing policy is not always linked to lacking resources, such as housing shortage, and may thus be a political expression and a specific idea concerning refugee integration (Lidén and Nyhlén, 2014; cf. Jutvik, 2020b). In fact, many municipalities with a low degree of available housing in general still provide permanent housing options. Following the variation in local housing policy, we argue that municipal housing can indeed be viewed as a form of migration control, allowing municipalities to choose who can settle in the long term.

In summary, it is possible that local policies may not always reflect a lack of resources but a goal to avoid the settlement of “undesired” segments of the population if they are not capable of demonstrating an ability to find housing for themselves. Empirically, rights-based approaches are associated with municipalities governed by left-wing parties. Interestingly, even though duty-based approaches are associated with municipalities governed by right-wing parties, there is larger variation in this group in which many municipalities governed by right-wing coalitions provide permanent housing. These examples could be understood as welcoming or unwelcoming cities, with housing used as part of integrative or blocking strategies (Huang and Liu, 2018; Turam, 2021). Moreover, we have found empirical relevance for our theoretical model; in fact, all policy types are represented at the municipal level. So, the discussion of housing as a “right” or a “reward” at the local level is relevant from a theoretical perspective (cf. Borevi, 2010). This could also reflect which resilience approach is used—a social resilience approach or a more neoliberal approach. To conclude, we believe housing policy may function as a type of migration control in other countries as well, particularly in those in which the local level has influence over welfare services. As a venue for future studies, we argue that the application of our typology is useful in other international settings as well as in comparative work.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The datasets used in this article are publicly available at the homepage of each organization. See references for links to the datasets. The main data in the article constitute “Bostadsmarknadsenkäten” which is a yearly survey gathered by the National Board of Housing, Building and Planning (NBHBP). We use the survey data from 2019 and 2020. This data can be accessed freely from the webpage of the NBHBP. Please see link in reference list. Replication code is available upon request after contact with the corresponding author.

KJ and GL have implemented the analysis of the surveys and the construction of the housing index. KJ have designed the maps of the municipal housing policies in Sweden. All authors have contributed equally to the process of planning, writing, and reviewing the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

EH and KJ have received funding from Formas – a Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development (Grant Number: 2021-00085). EH have received funding from Formas (Grant Number: 2020-02046). KJ have received funding from Formas (Grant number: 2020-0232). GL have received funding from Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (Grant Number: SAB20-0023).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We are grateful for comments on previous versions of this manuscript by the reviewers, Sarah Leonard and Helga Kristin Hallgrimsdottir, Anton Ahlén and seminar participants at the Swedish Political Science Association, the staff at the National Board of Housing, Building and Planning, seminar participants at the European Consortium for Political Research, and seminar participants at European Network for Housing research.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.885892/full#supplementary-material

1. ^Even though not everyone in this group has been given residence permits in Sweden as recognized refugee, we use this term consistently.

2. ^Asylum-seekers and immigrants granted a residence permit may also arrange with their own accommodation, so-called EBO (“eget boende” in Swedish). Using this option, they can move to any municipality as long as they can find an apartment (usually, they are lodgers at friends and relatives). However, the focus in this paper is on the municipal (ABO) reception.

3. ^The model is based on the municipality's population size, the local labor market situation, and how many asylum seekers already reside in the municipality. The government proposes the number of refugees to be received by each region and municipality. Deviations from this proposal can only be accepted if they do not violate the quota that the region is obliged to accept. The County Administrative Board handles the next stage of the process, including any renegotiations between the municipalities involved.

Ager, A., and Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: a conceptual framework. J. Refug. Stud. 21, 166–191. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fen016

Ahouga, Y. (2018). The local turn in migration management: the IOM and the engagement of local authorities. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 44, 1523–1540. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2017.1368371

Anholt, R., and Sinatti, G. (2020). Under the guise of resilience: The EU approach to migration and forced displacement in Jordan and Lebanon. Contemp. Secur. Policy 41, 311–335. doi: 10.1080/13523260.2019.1698182

Baeten, G., and Listerborn, C. (2015). Renewing urban renewal in Landskrona, Sweden: pursuing displacement through housing policies. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 97, 249–261. doi: 10.1111/geob.12079

Bolin, N., Lidén, G., and Nyhlén, J. (2014). Do anti-immigration parties matter? The case of the sweden democrats and local refugee policy. Scand. Polit. Stud. 37, 323–343. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.12031

Borevi, K. (2010). “Dimensions of citizenship: European integration policies from a scandinavian perspective,” in Diversity, Inclusion and Citizenship in Scandinavia, eds. P. Strömblad, A.-H. Bay, and B. Bengtsson (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars).

Borevi, K. (2012). “Sweden: the flagship of multiculturalism,” in Immigration Policy and The Scandinavian Welfare State 1945–2010 (Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan), 25–96.

Bourbeau, P. (2015). Migration, resilience and security: responses to new inflows of asylum seekers and migrants. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 41, 1958–1977. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2015.1047331

Brown, P., Gill, S., and Halsall, J. P. (2022). The impact of housing on refugees: an evidence synthesis. Housing Stud. 1–45. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2022.2045007. [Epub ahead of print].

County Administrative Board in Jönköping (2020). Lägesbilder från kommuner och regioner 2020 - Mottagande av asylsökande, nyanlända och ensamkommande barn (Jönköping).

County Administrative Board in Jönköping (2019). Lägesbilder från kommuner och regioner 2019 - Mottagande av asylsökande, nyanlända och ensamkommande barn (Jönköping).

County Administrative Board in Stockholm (2020). Bostad sist? Om bosättningslagen och nyanländas boendesituation i Stockholms län (Stockholm).

Cretney, R. (2014). Resilience for whom? Emerging critical geographies of socio-ecological resilience. Geogr. Compass 8, 627–640. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12154

Dekker, R., Emilsson, H., Krieger, B., and Scholten, P. (2015). A local dimension of integration policies? Int. Migr. Rev. 49, 633–658. doi: 10.1111/imre.12133

Emilsson, H., and Öberg, K. (2021). Housing for refugees in Sweden: top-down governance and its local reactions. J. Int. Migr. Integr. doi: 10.1007/s12134-021-00864-8. [Epub ahead of print].

Eurostat (2022). Statistics. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/data/database (accessed May 10, 2022).

Filindra, A., and Goodman, S. W. (2019). Studying public policy through immigration policy: advances in theory and measurement. Policy Stud. J. 47, 498–516. doi: 10.1111/psj.12358

Gammeltoft-Hansen, T., and Tan, N. F. (2017). The end of the deterrence paradigm? Future directions for global refugee policy. J. Migr. Hum. Secur. 5, 28–56. doi: 10.1177/233150241700500103

Granath Hansson, A. (2017). Promoting planning for housing development: what can Sweden learn from Germany? Land Use Policy 64, 470–478. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.03.012

Grange, K., and Björling, N. (2020). Migrationens ojämna geografi: Bosättningslagen ur ett rättviseperspektiv. Mistra Urban Futures Report.

Gulasekaram, P., and Ramakrishnan, S. K. (2015). The New Immigration Federalism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hagelund, A. (2020). After the refugee crisis: public discourse and policy change in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Comp. Migr. Stud. 8, 13. doi: 10.1186/s40878-019-0169-8

Hall, P. A., and Lamont, M. (2013). “Introduction,” in Social Resilience in the Neoliberal Era, eds P. A. Hall and M. Lamont (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1–32.

Hammar, T. (1985). European Immigration Policy: A Comparative Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hernes, V. (2018). Cross-national convergence in times of crisis? Integration policies before, during and after the refugee crisis. West Eur. Polit. 41, 1305–1329. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2018.1429748

Holmqvist, E., and Magnusson Turner, L. (2014). Swedish welfare state and housing markets: under economic and political pressure. J. Hous. Built Environ. 29, 237–254. doi: 10.1007/s10901-013-9391-0

Holmqvist, E., Omanović, V., and Urban, S. (2020). Organisation av arbetsmarknads- och bostadsintegration. Stockholm: SNS Förlag.

Huang, X., and Liu, C. Y. (2018). Welcoming cities: immigration policy at the local government level. Urban Aff. Rev. 54, 3–32. doi: 10.1177/1078087416678999

Hudson, C., Lidén, G., Sandberg, L., and Giritli-Nygren, K. (2021). “Between central control and local autonomy – the changing role of swedish municipalities in the implementation of integration policies,” in Local Integration Policy of Migrants - European Experiences and Challenges (Cham: Palgrave MacMillan).

Jutvik, K. (2020a). Governing Migration: On the Emergence and Effects of Policies Related to the Settlement and Inclusion of Refugees. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Available online at: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-404108 (accessed December 20, 2021).

Jutvik, K. (2020b). Unity or distinction over political borders? The impact of mainstream parties in local seat majorities on refugee reception. Scand. Polit. Stud. 43, 317–341. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.12175

Kolada (2021). Kolada- Den öppna och kostnadsfria databasen för kommuner och regioner. Available online at: https://www.kolada.se/ (accessed May 10, 2022).

Koopmans, R. (2010). Trade-offs between equality and difference: immigrant integration, multiculturalism and the welfare state in cross-national perspective. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 36, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/13691830903250881

Lidén, G., and Nyhlén, J. (2014). Explaining local Swedish refugee policy. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 15, 547–565. doi: 10.1007/s12134-013-0294-4

Lidén, G., and Nyhlén, J. (2022). Local Migration Policy: Governance Structures and Policy Output in Swedish Municipalities. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Marshall, T. H. (1950). Citizenship and Social Class and Other Essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Martínez-Ariño, J., Moutselos, M., Schönwälder, K., Jacobs, C., Schiller, M., and Tand,é, A. (2019). Why do some cities adopt more diversity policies than others? A study in France and Germany. Comp. Eur. Polit. 17, 651–672. doi: 10.1057/s41295-018-0119-0

McDaniel, P. N., Rodriguez, D. X., and Wang, Q. (2019). Immigrant integration and receptivity policy formation in welcoming cities. J. Urban Aff. 41, 1142–1166. doi: 10.1080/07352166.2019.1572456

Meer, N., Dimaio, C., Hill, E., Angeli, M., Oberg, K., and Emilsson, H. (2021). Governing displaced migration in Europe: housing and the role of the “local.” Comp. Migr. Stud. 9, 2. doi: 10.1186/s40878-020-00209-x

Myrberg, G. (2017). Local challenges and national concerns: municipal level responses to national refugee settlement policies in Denmark and Sweden. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 83, 322–339. doi: 10.1177/0020852315586309

Myrberg, G., and Westin, S. (2016). “Bostadsbrist som problem vid bosättning av flyktingar - hur ser kommunerna på frågan?,” in Mångfaldens dilemman - Medborgarskap och integrationspolitik, eds B. Bengtsson, G. Myrberg, and R. Andersson (Malmö: Gleerups), 81–100.

National Board of Housing, Building Planning (NBHBP). (2020). Bostadsmarknadsenkäten 2019. Available online at: https://www.boverket.se/sv/samhallsplanering/bostadsmarknad/bostadsmarknaden/bostadsmarknadsenkaten/ (accessed May 10, 2022).

National Board of Housing, Building Planning (NBHBP). (2021). Bostadsmarknadsenkäten 2020. Available online at: https://www.boverket.se/sv/samhallsplanering/bostadsmarknad/bostadsmarknaden/bostadsmarknadsenkaten/ (accessed May 10, 2022).

OECD (2018). Working Together for Local Integration of Migrants and Refugees. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264085350-en (accessed May 10, 2022).

Penninx, R., and Garcés-Mascareñas, B. (2016). “The concept of integration as an analytical tool and as a policy concept,” in Integration Processes and Policies in Europe, eds B. Garcés-Mascareñas and R. Penninx (Cham: Springer), 11–29.

Phillips, D. (2006). Moving towards integration: the housing of asylum seekers and refugees in Britain. Housing Stud. 21, 539–553. doi: 10.1080/02673030600709074

Preston, V., Shields, J., and Akbar, M. (2021). Migration and resilience in urban Canada: why social resilience, why now? J. Int. Migr. Integr. doi: 10.1007/s12134-021-00893-3. [Epub ahead of print].

Prokkola, E.-K. (2021). Borders and resilience: asylum seeker reception at the securitized finnish-Swedish border. Environ. Plan. C Polit. Space 39, 1847–1864. doi: 10.1177/23996544211000062

Qvist, M. (2012). Styrning av lokala integrationsprogram. Institutioner, nätverk och professionella normer inom det svenska flyktingmottagandet. Linköping: Linköpings universitet.

Rast, M. C., Younes, Y., Smets, P., and Ghorashi, H. (2020). The resilience potential of different refugee reception approaches taken during the ‘refugee crisis' in Amsterdam. Curr. Sociol. 68, 853–871. doi: 10.1177/0011392119830759

Sandström, L. (2020). Seeking Asylum - Finding a Home? A Qualitative Study on Asylum Seekers' Integration in Two Different Housing Contexts. Available online at: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:oru:diva-78540 (accessed February 22 2022).

Schammann, H., Gluns, D., Heimann, C., Müller, S., Wittchen, T., Younso, C., et al. (2021). Defining and transforming local migration policies: a conceptual approach backed by evidence from Germany. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 13, 2897–2915. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2021.1902792

Søholt, S., and Aasland, A. (2021). Enhanced local-level willingness and ability to settle refugees: decentralization and local responses to the refugee crisis in Norway. J. Urban Affairs 43, 781–798. doi: 10.1080/07352166.2019.1569465

Søholt, S., Stenbacka, S., and Nørgaard, H. (2018). Conditioned receptiveness: nordic rural elite perceptions of immigrant contributions to local resilience. J. Rural Stud. 64, 220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.05.004

Statistics Sweden (2021). Statistikdatabasen. Available online at: https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/ (accessed May 10, 2022).

Stumpp, E. (2013). New in town? On resilience and “Resilient Cities”. Cities 32, 164–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2013.01.003

Swedish Association of Local Authorities Regions (2019a). Riksrevisionens rapport om stödet till kommuner för ökat bostadsbyggande.

Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (2019b). Styre och maktfördelning för tidsperioden 1994–2018.

Swedish Migration Agency (2021). Statistik. Available online at: https://www.migrationsverket.se/Om-Migrationsverket/Statistik.html (accessed May 10, 2022).

Turam, B. (2021). Refugees in borderlands: Safe places versus securitization in Athens, Greece. J. Urban Aff. 43, 756–780. doi: 10.1080/07352166.2021.1925128

Vogiazides, L., and Mondani, H. (2020). A geographical path to integration? Exploring the interplay between regional context and labour market integration among refugees in Sweden. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 46, 23–45. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2019.1588717

Walker, K. E., and Leitner, H. (2011). The variegated landscape of local immigration policies in the United States. Urban Geogr. 32, 156–178. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.32.2.156

Wennström, J., and Öner, Ö. (2015). Den geografiska spridningen av kommunplacerade flyktingar i Sverige. Ekon. Debatt 43, 52–68.

Williamson, A. F. (2018). Welcoming New Americans? Local Governments and Immigrant Incorporation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Available online at: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/W/bo28551595.html (accessed May 5, 2020).

Zapata-Barrero, R., Caponio, T., and Scholten, P. (2017). Theorizing the ’local turn' in a multi-level governance framework of analysis. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 83, 241–246. doi: 10.1177/0020852316688426

Keywords: migration, integration, resilience, Sweden, municipalities, local housing policy

Citation: Holmqvist E, Jutvik K and Lidén G (2022) Resilience in Local Housing Policy? Liberal or Restrictive Policy Stances Among Swedish Municipalities Following the Great Migration in the Summer of 2015. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:885892. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.885892

Received: 28 February 2022; Accepted: 26 April 2022;

Published: 20 June 2022.

Edited by:

Ricard Zapata Barrero, Pompeu Fabra University, SpainReviewed by:

Sarah Leonard, University of the West of England, United KingdomCopyright © 2022 Holmqvist, Jutvik and Lidén. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kristoffer Jutvik, S3Jpc3RvZmZlci5qdXR2aWtAaWJmLnV1LnNl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.