- Political Science and International Relations, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand

The adoption of restrictive policies to contain the spread of COVID-19 has led many to fear the authoritarian implications of excessive government powers over compliant publics. One of the strongest government responses took place in New Zealand, followed only a few months later by the landslide election victory of the Labour Party, the dominant party in the pre-election coalition. This article tests a claim that authoritarian dispositions were mobilized into an authoritarian electoral response. It finds no evidence of a significant shift toward authoritarianism. Authoritarianism did not increase in the mass public and liberals were more likely than authoritarians to approve of the government response and to move toward a vote for the Labour Party, a tendency most apparent among liberals on the right. To the small extent that some disposed toward authoritarianism did move toward the government, they tended to be on the left and/or have higher than average trust in politicians.

Introduction

A burgeoning literature is emerging on and around the analysis of political responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Within it, there has been much attention to the concept of authoritarianism. Strong government responses to restrict transmission of the virus have prompted criticisms of excessive state power. Following the logic of recent theories of authoritarianism, some commentators, and researchers go further to suggest that because of increased threat, fear and insecurity, there could be a consequent authoritarian shift in mass public opinion (Karwowski et al., 2020; Pazhoohi and Kingstone, 2021). Such a shift might be further encouraged by draconian government responses, paving the way for breaches of liberal principles that may constitute a threat to democracy itself (Funk and Linzer, 2020; Gebrekidan, 2020; Maerz et al., 2020; Simandan et al., 2021). Indeed, some researchers in Europe report that it was right-wing, traditional, authoritarian, and nationalist governments that acted more quickly to impose lockdowns and require the closure of schools (Toshkov et al., 2021). However, in the United States, Republican Governors were slower than Democratic Governors to impose social distancing rules (Adolph et al., 2021), and authoritarians have been found to have had less concern about COVID-19 than liberals (Prichard and Christman, 2020)1.

In the light of conflicting findings, relationships between attitudes, ideology and partisan control of governments and the extent, nature and success of the COVID-19 response remain uncertain. Meanwhile from a different direction a host of other studies have provided convincing evidence that levels of political and generalized social or interpersonal trust may provide stronger explanations for the public response to governments' actions to protect their populations from COVID-19 (for example, Altiparmakis et al., 2021). Trust also has some associations with the authoritarian-liberal dimension. There is evidence that because of their respect for authority authoritarians are more prone to political trust, particularly under conditions of threat (Dunn, 2020). On the other hand, authoritarians are prone to strong group identifications, and therefore tend to trust leaders that express their values and concerns and potentially distrust those who do not (Porter, 2007, p. 42). Interactions between political trust and authoritarianism need further research. Recent German evidence identifies an entirely different angle, finding that high political trust makes it possible for liberals to accept government restrictions they might otherwise oppose (Jäckle et al., 2022).

Case Selection

Analysis of public opinion and behavior at the time of the New Zealand general election of October 2020 uncovers a series of circumstances, events, and government policies that go to the heart of some of these concerns and questions. Using time series, panel, and post-election survey data from the New Zealand Election Study (NZES), this paper addresses not only the question of mass public attitudes but, going beyond much of the current literature, their electoral effects. New Zealand's government responded more strongly than that of any other advanced democracy. Its lockdowns were among the most comprehensive but also the most effective. New Zealand closed its borders to almost all but New Zealand citizens and residents, and quickly moved to require compulsory quarantine of those returning in government-controlled facilities. Government policy was strongly shaped by advice from health professionals both inside and outside of government, given greater force because of New Zealand's very low ratio of intensive care units to population, one of the lowest among the advanced economies (OECD, 2020, p. 7, 13).

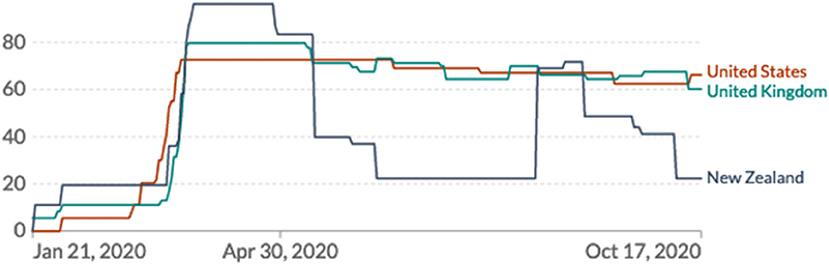

The pay-off was a successful elimination strategy over almost 2 years (Cameron, 2020). As Figure 1 shows, throughout 2020 lockdowns were sharp but also short, at least in comparison to those of other countries. The death rate remained extremely low when compared to rates almost everywhere else. Until the arrival of the more infectious Omicron variant, successful lockdowns were based on a “go hard/go early” principle, leaving the country COVID-free for much of 2020 and 2021 although the largest city, Auckland, suffered more than the rest of the country, and was locked down off and on for about a quarter of the period during the years 2020 and 2021. Meanwhile a strong fiscal stimulus addressed the consequences of the lockdowns and border closure (IMF Fiscal Affairs Department, 2021).

Figure 1. COVID-19 stringency index, New Zealand, the United States, and United Kingdom January–October 2020. Our world in data, under creative commons.

The government that faced the onset of COVID-19 was a center-left leaning coalition of the Labour and New Zealand First parties, with the support of the Green Party. Labour Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern took a major role presenting the government's public face to the pandemic. As the cases grew, she held daily media briefings that were televised nationally and had a wide audience (Grieve, 2020; Beattie and Rebecca, 2021). Her appeals for kindness, understanding and national unity resonated strongly, as did her use of the term “team of five million” to underpin a sense of collective identity expressed by the Ministry of Health's slogan “Unite Against COVID-19.”

The general election scheduled for September was postponed for a month because of a revival of cases in Auckland that triggered a regional lockdown. By the time of the election on October 23, cases had subsided and it could be held under near normal conditions. Successful encouragement of advance voting reduced crowding in voting places. The Labour Party was rewarded with a historic landslide victory, securing a single-party government majority for the first time under the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) electoral system adopted after a referendum in 1993. Labour's coalition partner New Zealand First made the mistake of distancing itself from the government response and paid the price in vote losses that excluded it from Parliament because of failure to meet the 5 per cent thresold required for representation. The Opposition centre-right National Party's vote sank to just over 25 per cent, while the libertarian-right ACT Party increased its vote significantly to 8 per cent, still putting the centre-right parties well short of government. An anti-lockdown party, Advance New Zealand, secured only one per cent of the vote.

On the surface there appears evidence of an authoritarian response, voters apparently rewarding the government for its actions, despite criticism that some of the restrictions imposed lacked initial legal foundations (McLean et al., 2021). However, data from the VDEM democratic backsliding project (Pandemic Backsliding Project, 2022) has continued to maintain New Zealand at its highest level of liberal democracy and records no significant violations of democratic standards during the period 2020–20222.

Authoritarianism, Trust, Expectations, and Hypotheses

The concept of authoritarianism entered social science in the aftermath of World War Two as an explanation of the mass attitudes mobilized by Fascist and Nazi Parties (Fromm, 1941). In the hands of Adorno et al. (1950), it was theorized as an attribute of personality. Its dictionary definition is “the enforcement or advocacy of strict obedience to authority at the expense of personal freedom” (Lexico, 2022). Initially derived from psychoanalytic theory, the origins of authoritarianism were identified in childhood socialization within the family. Measurement of authoritarianism at the individual level was operationalised by a series of thirty questions added together to form “the F-scale,” short for Fascism scale. Inspection of the items today indicates how much was shaped for its particular time and place (see Anesi, 2018). While the scale itself has been found wanting in subsequent research, particularly because the acquiesence bias of its instruments, many of its underlying concepts and modified versions of several of its components have survived in theory and in survey research up to the present (see Duckitt, 2022 for a review).

Two of its elements are the most relevant for the present inquiry; first, projectivity, the belief that the world is a dangerous place, full of dangers and threats (Duckitt, 2013), perceptions likely to be enhanced by a pandemic experience with the potential to unleash “a primal, deep fear of death” (Baekgaard et al., 2020). The second element is power and toughness, particularly bound up with identification and deference to those in authority. The emphasis on power and toughness has carried through into two scales now widely used in political psychology, based on survey instruments that estimate social dominance orientation (SDO) and right wing authoritarianism (RWA) (Altemeyer, 1981; Sibley and Duckitt, 2008). Together they are successful in explaining prejudice and other authoritarian attitudes and behaviors, SDO primarily among authoritarian leaders and RWA among followers (Asbrock et al., 2010).

Early criticism of the original F-Scale was also based on its identification of authoritarianism as necessarily on the political right or associated with conservatism. Altemeyer's RWA scale can also be criticized on similar grounds. Recently there has been renewed interest in the phenomenon of left wing authoritarianism, hitherto lacking a sustained research effort (Duckitt, 2022, p. 180). Scales estimating left-wing authoritarianism have been proposed and successfully tested (Conway et al., 2018; Manson, 2020; Costello et al., 2021). Similarities between left and right-wing authoritarianism have been identifed in the United States (Manson, 2020): belief in a dangerous world, and a preference for state control.

However, if authoritarianism can be found on both left and right, it should have underlying elements independent of left- or right-wing ideologies. Ideally, it should be identifiable in its own terms, and condition and interact with left and right positions, consistent with a picture of two-dimensional “ideological space” widely understood in political science (for example, Dalton, 2020, p. 146–154). Estimation of both left and right wing authoritarianism is largely based on its manifestations rather than on its underlying core, raising questions of endogeneity (Van Assche et al., 2019; Satherley et al., 2021). Choice of such manifestations also runs the risk of cultural, national, or historical bias. For example, several questions in the RWA scale implicitly tap into a European or North American form of conservative Christianity (see Johnson, 2020). Most now using the concept of authoritarianism acknowledge that it is better regarded as a set of related beliefs or attitudes than a personality trait (Duckitt, 1989). One must also be careful about implying that authoritarianism is necessarily pathological, a natural assumption given the origins of the concept in study of Fascism. Authoritarianism can have a “good side,” notably in its concern with social solidarity and the protection of other members of one's society, values that came to the fore in New Zealand's COVID-19 response. And authoritarians do not necessarily have a monopoly over intolerance of those with whom they disagree (Tillman, 2021, p. 45).

A turn toward operationalisation of the concept as a “disposition” has considerable promise. It is based on the underlying mechanism of childhood rearing values (CRV) first proposed by Adorno and his colleagues. A series of questions ask respondents to choose between various pairs of alternatives that counterpose liberal vs. authoritarian approaches to child-rearing (Feldman and Stenner, 1997; Engelhardt et al., 2021; Feldman et al., 2021). Following Stenner (2005), we might therefore expect an “authoritarian dynamic”: that is, authoritarian dispositions based on CRV will be projected into explicit authoritarian attitudes and behaviors under conditions of normative threat such as those presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. Some evidence for this proposition has been found in both the UK and Ireland. Among those for whom anxiety about COVID-19 had become intense, those with high RWA became more nationalistic and opposed to immigration (Hartmann et al., 2021). From this standpoint, the RWA scale or many of the questions derived from it are best seen as outcome variables triggered by threat and lying in a mediating position between dispositions and political behavior. The underlying dispositional foundations of authoritarianism are therefore best measured by the CRV approach described above. If those can be successfully conditioned by the cross-cutting dimension of left and right, a relatively independent measure of authoritarianism could be in sight. But because the RWA scale has an implicit bias to the right, it is not a likely instrument for this task.

Because of the tendency of authoritarians to unite around in-group loyalty, we might expect left and right to cut across authoritarian/liberal attitudes most obviously in terms of identification with those currently in authority. Consequently left authoritarians might respond favorably to decisive policies from a government of the left, but not to those of a government of the right, with the opposite effect on left authoritarians with a government of the right. In New Zealand in 2020, if this logic is correct one can hypothesize that, all else equal, left authoritarians would support the government and its policies, and right authoritarians should oppose them.

Meanwhile trust has emerged as an important explanation of infection and fatality rates associated with COVID-19 over the first year of the pandemic: both trust in government and generalized social or interpersonal trust (Altiparmakis et al., 2021; COVID-19 National Preparedness Collaborators, 2022; Stefaniak et al., 2022; Yuan et al., 2022). Both social and political trust have implications for authoritarianism. A lack of generalized social or interpersonal trust in a world full of danger has been one of the factors associated with authoritarianism from the very beginning of its operationalisation in the F-scale3. Another factor associated with authoritarianism is founded in the distrust implicit in belief in conspiracy theories, and has been found to be associated with resistance to government measures against COVID-19 (Rieger and Wang, 2021). Authoritarians are also more resistant to vaccination (Oleksy et al., 2022).

In general, trust in politicians should be expected to make citizens more receptive to government action to address the pandemic, and this is confirmed by research in the UK and Germany (Dohle et al., 2020; Weinberg, 2020). But trust might be expected to play out differently among liberals and authoritarians, again requiring a conditional or interactive approach. On the one hand, deference to authority could be associated with high trust of politicians among authoritarians. On the other, as theories of authoritarianism have long acknowledged, if authoritarians perceive government as weak, indecisive, or failing to govern according to their principles, they could perceive a normative threat that might therefore lead them to have a relatively low level of political trust. As for liberals, they might be expected to resist stringent COVID protection policies. However, liberals with trust in government might accept them. And indeed in Germany high levels of political trust are found to have led liberals to support a strong government response (Jäckle et al., 2022).

The effects of generalized social or interpersonal trust are more contested territory. Like political trust, interpersonal trust measured at the country-level tends to be associated with fewer cases and deaths (for example, COVID-19 National Preparedness Collaborators, 2022). People who are trusting may be more likely to comply with government restrictions particularly if their fellow citizens are obeying the rules. But others argue that a high level of generalized social trust encourages people to see government restrictions as unnecessary (see Jäckle et al., 2022 for a brief summary of this literature). This factor deserves initial consideration in the analysis to come but, as will be seen, it seems to have little leverage in the case to hand.

The four hypotheses to test are therefore as follows.

H1. The experience of COVID-19 will generate higher levels of attitudinal authoritarianism than in the immediate past.

H2. A movement toward authoritarian attitudes will be associated with:

H3. Political trust and the authoritarian/liberal dimension will interact in one of two ways.

H4. Left authoritarians will accept restrictions and support the government, and right authoritarians will tend to oppose them both.

Data, Instruments, and Context

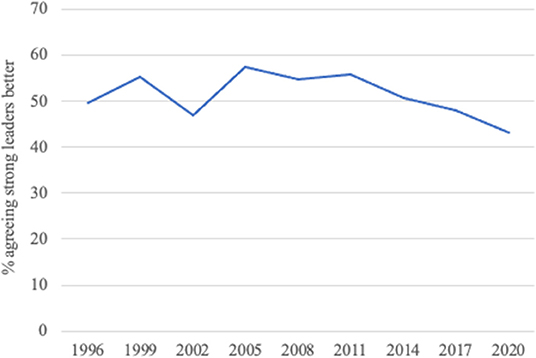

Data for this analysis comes first from the time series of the New Zealand Election Study (NZES) from 1996 to 2020, followed by analysis centred on its 2020-2017 panel and finally its 2020 cross-section (Vowles et al., 2021)4. The initial focus is on mobilization of the potential authoritarian preference for strong leadership based on the question: “A few strong leaders could make this country better than all the laws and talk” (Sanford, 1950; Janowitz and Marwick, 1953). This is a question modified from one in the original F-scale, further modifications of which are also part of the RWA battery and continue to be used in election studies up to the present (Engelhardt et al., 2021).

This question has been consistently asked in the New Zealand Election Study since 1990. With two other associated items, it was included because of claims that New Zealand in the 1950s and 1960s and before had a somewhat authoritarian political culture (Ausubel, 1965; Bedggood, 1975). Indeed, there has been a relatively recent historical experience of authoritarian government underpinned by a supportive mass public. The National party government led by Robert Muldoon in office from 1975 to 1984 remains notorious for the Prime Minister's bullying style of political leadership, its disregard of constitutional norms, its rhetorical attacks on the mass media, and the extreme lengths it took to closely control and regulate the economy. Authoritarian public attitudes were also associated with those wishing to retain New Zealand's previous first past the post electoral system, and liberal attitudes were associated with those wishing to adopt MMP (Lamare and Vowles, 1996). An authoritarian style of leadership persists within the New Zealand First Party, led by former National Party Cabinet Minister Winston Peters. While a minor party, because of its pivotal position in the party system New Zealand First has on three occasions been included in governments, one with National, and two with Labour, including the government in office at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Populist and authoritarian attitudes were a focus of the 2017 NZES (Vowles and Curtin, 2020).

In the 2020 NZES although not in earlier studies the underlying CRV authoritarian disposition is estimated from a series of questions on childrearing. All questions are introduced with the statement: “although there are a number of qualities that people think children should have, every person thinks that some are more important than others. Although you may feel both qualities are important, please choose which one of each pair of desirable qualities for children you think is more important...” The pairs are: independence or respect for others; good manners or curiosity; self-reliance or obedience; being well-behaved or being considerate; being imaginative or being orderly; being polite or being free-spirited. The questions are scored by addition, where 1 or the authoritarian response, 0 non-authoritarian, with those not responding coded at 0.5 (Feldman and Stenner, 1997, p. 751). Because of the content, this scale is also widely understood to be a measure of social conservatism as against social liberalism (Duckitt, 2022, p. 178).

In New Zealand in October 2020 respondents were distributed normally across the dimension, with a skew toward liberalism. About 60 per cent of respondents sat at the mid-point or in the adjacent category. The items scale with an alpha of 0.625. The scale correlates with the authoritarian leadership question at r = 0.23. There is significantly higher support for authoritarian leadership than there appears to be for authoritarian expectations of childhood behavior. To some extent, this could be attributable to response acquiesence bias in the leadership question. But the modest correlation also suggests there are other sources of support for authoritarian leadership outside the childrearing practice definition. Most notably, there are many dispositional liberals who favor authoritarian leadership: 17% of the sample, a slightly higher proportion than the number of dispositional authoritarians who favor it. The correlation between the two variables survives modestly because it is driven almost entirely by the tendency of dispositional authoritarians not to favor weak leadership. It is possible that appreciation of strong leadership is a facet of New Zealand political culture, as discussed earlier. Appreciation of strong authoritarian leadership is also found on the left, making up about 8 per cent of the sample, but dispositional authoritarianism is much less prevalent on the left at only 3 per cent (see Supplementary Tables 1–3).

Placing the New Zealand case in global trust rankings, the 2017–2020 wave of the World Values Survey (WVS) confirms relatively high levels of social and political trust in New Zealand before the pandemic when compared to similar countries (Haerpfer et al., 2002). Among democratic countries with a free media New Zealand rates well for confidence in government and also in trust for people one does not know6. Survey research on trust within New Zealand reports findings consistent with the WVS sample taken at much the same time, as well as a slight increase in political trust after the Labour-led coalition took office in 2017 (Chapple and Prickett, 2019). Ardern's government had the advantage of relatively high levels of political trust, almost certainly giving it an advantage to build on a foundation or “stock” not available in many other countries. Indeed, the pre- and post-lockdown changes have been tracked with a particular emphasis on the short-term effects of lockdown that had a positive impact on trust (Sibley et al., 2020). Trust in politicians is measured simply by the five-point agree/disagree question: “Most politicians are trustworthy” and generalized social/interpersonal trust by a reveral of agreement and disagreement with the statement “Most people would try to take advantage of others if they got the chance,” again on a five-point scale. Left-right position is based on respondents self-assigned position on the standard ten-point Left-Right scale.

Given the big economic effects of lockdowns and the government response in general, in the cross-sectional analysis the standard sociotropic economic voting question is required as a control variable to allow for approval or disapproval of the response and of the government on economic grounds, high values indicating a positive evaluation. “Would you say that over the last 12 months the state of the New Zealand economy has got a lot better, a little better, stayed the same, got a little worse, got a lot worse.”

The two outcome variables are, first, approval or disapproval of the government's COVID response, based on the question: “Do you approve or disapprove of the way the government has responded to the COVID-19 outbreak?.” For clarity of interpretation, approve and strongly approve categories are merged, scoring one, and the rest in the alternative category, scoring 0. The second outcome variable is report of a party vote for Labour at the 2020. Turnout has been validated from the marked electoral rolls.

Data Analysis

Time Series

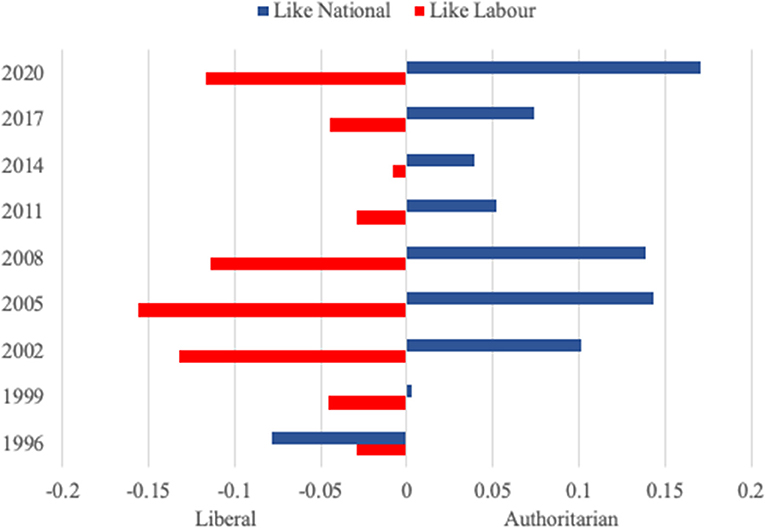

Addressing hypothesis 1, and using the NZES time series from 1996 to the present, the association between preferences for authoritarian leadership and those for political parties can be examined over time in Figure 2. In 1996, like/dislike preferences for both major parties were more closely associated with liberalism or non-authoritarianism: at that time, at the first election under the MMP system, the center-right New Zealand First and left-wing Alliance parties were challenging the dominance of the traditional major parties, and drew their support somewhat more from authoritarian than liberal voters. A clear distinction between National and Labour appears on the dimension in 2002, and it strengthened in 2005 and 2008 when a period of tighter two-party competition concluded with a change of government from Labour to National in 2008. Authoritarian/liberal polarization weakened under the National-led government that followed, but began to open again up in 2017, widening still further in 2020.

Figure 2. Correlations between like/dislike scales of the two major parties and preferences for authoritarian leadership 1996–2020. NZES time series.

These findings pose some points for reflection. Given the international and recent New Zealand evidence, it is unsurprising that authoritarianism is more of a right- than left-wing phenomena in contemporary New Zealand although the variation over time indicates this is not necessarily a consistent association. In the current context, authoritarians might be more reluctant to be mobilized by a center-left government's response to a normative shock. On the other hand, with a significant pool of authoritarians on the right, and historical evidence of a different pattern, in October 2020 there was significant potential to attract some at least toward the left, particularly those closer to the centre than to the futher right. Indeed, it was the Labour Party that gained the most from the collapse in the vote for the New Zealand First Party, among whose voters authoritarianism was relatively prevalent (Curtin et al., 2022). Despite this, there seems little evidence of a significant authoritarian shift to Labour, although deeper analysis is required for confirmation. Further widening the focus, Figure 3 shows that, over time, preferences for authoritarian leadership have tracked downwards over successive elections since 1996. There was no net increase in authoritarian attitudes about leadership between 2017 and 2020.

Panel Analysis

Penetrating below the surface of these most recent net changes, the next step is to examine panel data. The 2020 NZES contains a panel of respondents initially participating in 2017, allowing estimation of change in preferences for authoritarian leadership between the two elections and thus testing hypothesis 2. If underlying dispositions were mobilized between the two elections toward a more explicit authoritarian response, this should be apparent. The 2017 and 2020 authoritarian leadership questions correlate at p = 0.48, a reasonable level of consistency.

About 40 per cent of respondents were entirely consistent in both years, with 32 per cent shifting toward liberalism and 27 per cent toward authoritarianism. However, these could be minor shifts, not necessarily taking them across the halfway mark between the two sides. Forty four 44 per cent crossed the boundary, although including those who moved in or out of a neutral position. Of the full sample, 9 per cent were authoritarians who moved to liberalism, 6 per cent were liberals who moved to authoritarianism; however, neutrals in 2017 were slightly more likely to move to authoritarianism than liberalism (8 compared to 6 per cent). But authoritarians were also slightly more likely to move to neutrality than liberals, forming 8 and 6 per cent of the sample (see Supplementary Table 4). The overall shift was about 3 per cent in the direction of liberal attitudes to leadership.

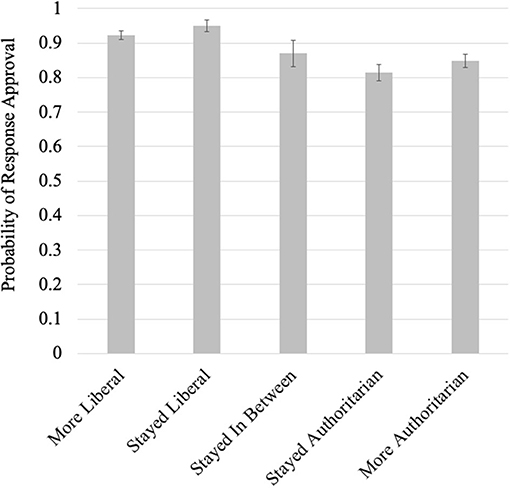

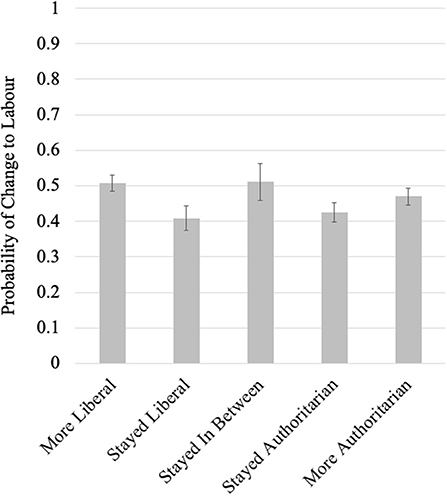

Figure 4 reports findings from a simple regression of changes in authoritarian leadership preferences between 2017 and 2020 on approval of the government's COVID-19 response. Again it is those who shift in a liberal direction who are most supportive of the COVID-19 response. Figure 5 shows probability estimates from a regression of authoritarian leadership change preferences with Labour vote in 2017 as a control against Labour vote in 2020, making it a more robust change model. The tables displaying the coefficients and standard errors for these regressions can be found in Supplementary Appendix. The patterns here are less obvious but the positive association between Labour vote and a liberal shift still stands out. Those shifting toward authoritarianism as well as toward support for Labour remain as equally prone to do so even after vote for New Zealand First in 2017 is added as a control in an alternative version of the model. Nonetheless, the two biggest shifts were among those becoming more liberal and those who remained at a balanced position between authoritarianism and liberalism, not those staying authoritarian or moving in that direction. As will be seen in the next sub-section, there was a shift to Labour among dispositional authoritarians but the shift to Labour among liberals was far more substantial.

Figure 4. Changes in preferences for authoritarian leadership on response approval 2017–2020. Logit model, Supplementary Table 5.

Figure 5. Changes in preferences for authoritarian leadership on change to Labour 2017–2020. Logit model, Supplementary Table 5. *represents interaction effect between the two variables.

Cross-Sectional Analysis, 2020 Election

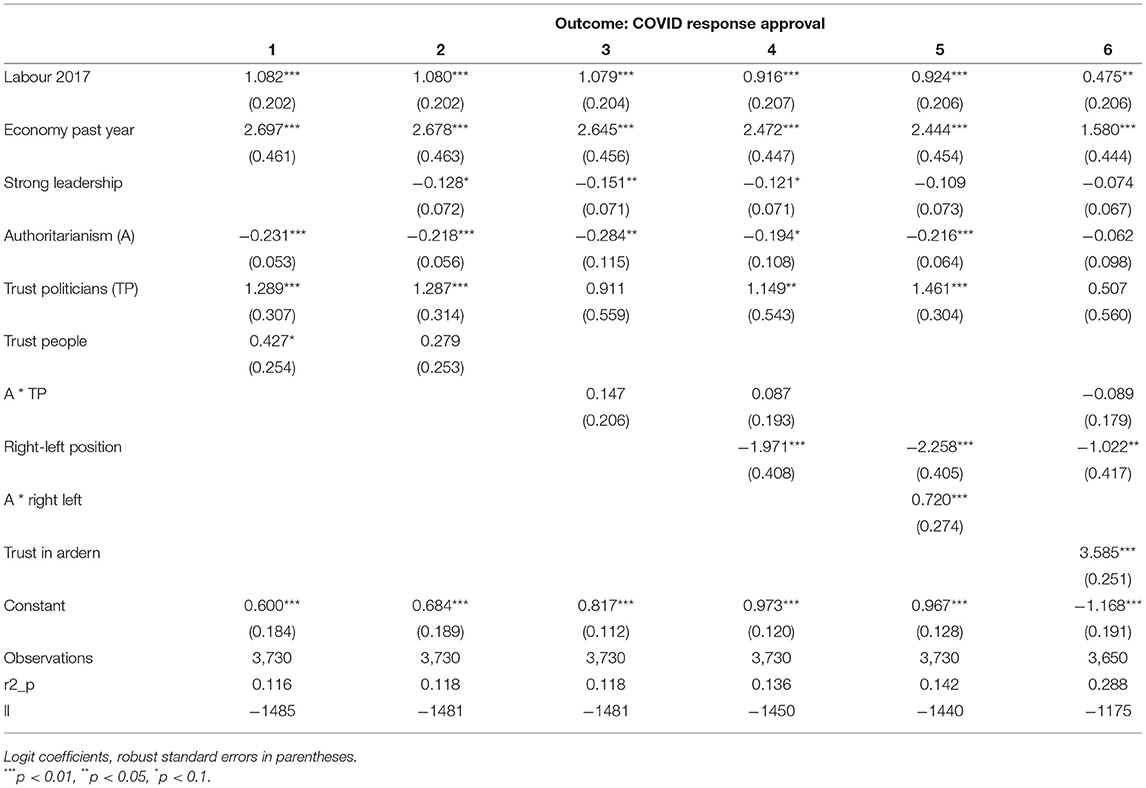

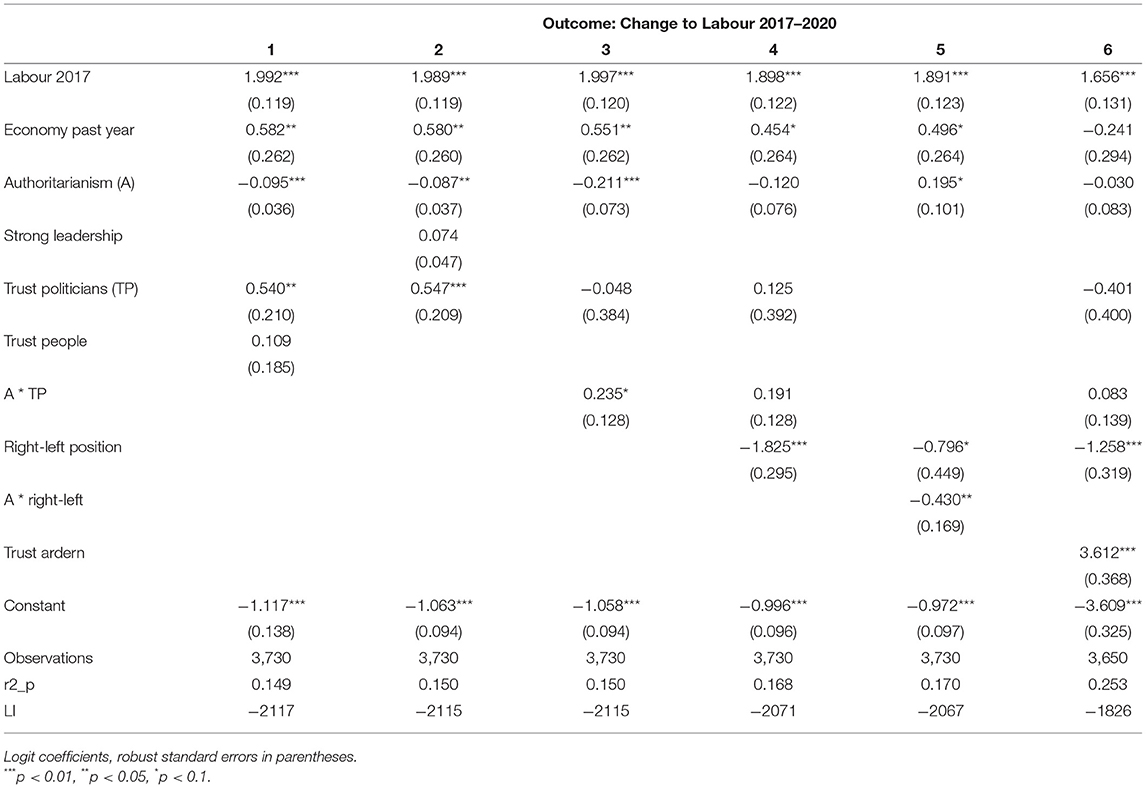

Further filling out the testing of hypothesis 2 and moving on to hypothesis 3, Table 1 displays the findings of a logistic regression model using the full 2020 NZES cross-sectional data. The binary outcome variable is from the question: “do you approve or disapprove of the way the Government has responded to the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak?” The same model is used against Labour vote in 2020, reported below.

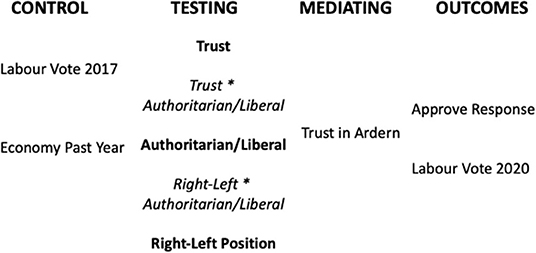

Figure 6 lays out the logic of the modeling. Labour vote in 2017 is a baseline control variable, estimating prior bias. Because the objective is to partial out the effects of attitudes net of other factors, perceptions of the health of the economy over the previous year are a further control. COVID-19 itself, government restrictions, and stimulus had an economic impact of interest to others, but only secondary to the matters to hand here. The explanatory variables of direct interest here are political and social trust—as it turns out, entirely the former—dispositional authoritarianism/liberalism, and right-left position (all in bold in the Figure 6). The two interaction terms in italics directly address the expectations established by hypotheses 3 and 4. Trust in Ardern reflects the more immediate short-term political context that should significantly affect the fit of the model and give a sense of the extent to which trust in Ardern may have been primed by the prior factors, as reflected in the lowering of their regression coefficients with its addition to the model. This is of little or no relevance to the hypothesis testing, but speaks to a more general interpretation of election, in which Ardern's leadership was a key element. Supplementary Table 6 displays a correlation matrix of all the variables and confirms that there is no multicollinearity of any concern after the interacted variable values were centred on their means.

Figure 6. Modeling on response approval and change to Labour 2020. Variables in bold those of most significance; those in italics are the interactions.

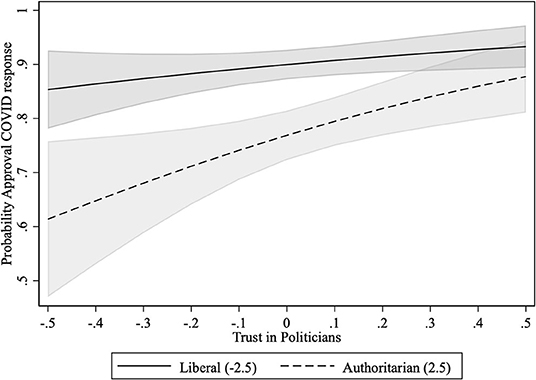

Table 1 displays the results of modeling on approval or disapproval of the government response. In the baseline version of the model, authoritarianism as a disposition has a negative effect on approval: that is, those potentially disposed toward authoritarianism are more likely to disapprove of the government response. In the next step, preferences for authoritarian leadership are added on top of the dispositional question. While significant, it adds nothing to the variance explained; at best, it mediates a very small part of the effects of the authoritarian disposition. If added prior to the dispositional version, authoritarian leadership explains notably less variance than does disposition. Trust in politicians, as expected, is associated with approval of the COVID-19 response. Interpersonal trust loads positively, but only significant at p <0.1 and drops out completely in the second step. The third step of the model adds the crucial interaction between trust in politicians and dispositional authoritarianism. While the interaction term itself is not significant, the authoritarian main effect is strong. And as Brambor et al. (2006, p. 74) advise, “it is perfectly possible for the marginal effect of X on Y to be significant for substantively relevant values of the modifying variable Z even if the coefficient on interaction term is insignificant.” For this reason it is imperative to plot the probabilities rather than inferring solely from the coefficients and their standard errors; indeed, in all cases the interpretation of interaction effects is greatly aided by this approach. Consequently, Figure 7 plots the probabilities and confidence intervals. It shows that trust in politicians increases support for the COVID response but much more so among authoritarians: liberals have a high level of support regardless of political trust and are hardly affected. Dispositional authoritarians disapprove of the COVID response, unless they have high trust in politicians7. This finding is almost exactly opposite to that reported in Germany (Jäckle et al., 2022).

Figure 7. How trust in politicians conditioned by authoritarianism/liberalism affects response support. Table 1, Model 3.

Self-identified right-left position is added next. This could have been included as a control in the earlier step. Its inclusion in step 4 reduces the impact of the authoritarian disposition on the outcome variable, and of the interaction term between authoritarian disposition and political trust. But it is of greater interest at step 3 to estimate the effects of authoritarianism without washing the effects out by way of the impact of a potential mediation through right-left. The possibility of an interaction between the authoritarian disposition and left-right is tested in the next step. The result is displayed in Figure 9, for discussion below. The final step adds trust in Jacinda Ardern. This washes out the effects of political trust, the short-term effect of trust in Ardern capturing all of its prior “stock” as an indirect effect. Right left position remain significant to the end although about half of its effects flow through trust in Ardern. As expected addition of trust in Ardern greatly enhances the fit of the model and makes it a more comprehensive analysis of the main features of the election in which public appreciation of Ardern's leadership did much to generate the Labour landslide.

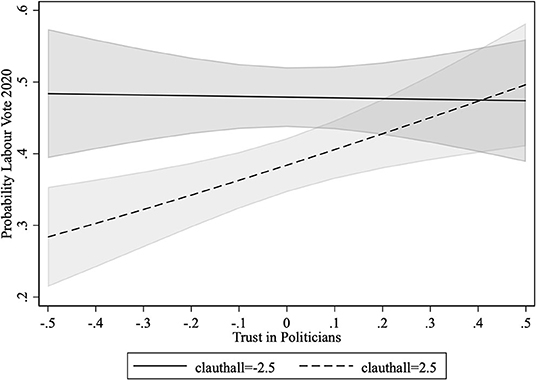

On Labour vote in 2020, the same step by step model strategy is applied, with results reported in Table 2. Those disposed toward authoritarianism tended to vote against Labour. Political trust is strongly associated with a Labour vote. When added in the second version of the model, authoritarian leadership preferences were insignificant and added nothing to the fit of the model. The same pattern as for response support is found when trust and those disposed to authoritarianism are interacted in Figure 8: high dispositional liberal support for Labour is entirely unaffected by political trust, but trust in politicians does help shift some of those disposed to authoritarianism to Labour. At the next step in the model, right-left self-identification is sufficient to remove the authoritarianism disposition from statistical significance, indicating indirect effects of authoritarianism running through left-right. All political trust effects also run through trust in Ardern when that variable is added, again greatly improving the fit of the model.

Figure 8. How trust in politicians conditioned by authoritarianism/liberalism affects change to Labour. Table 2, Model 3.

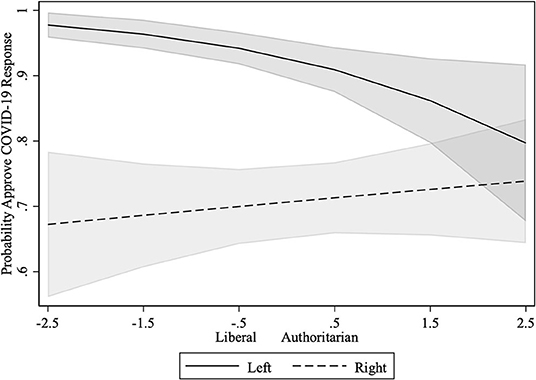

To address hypothesis 4, in the final step of the model right-left and dispositional authoritarianism-liberalism are interacted. Figure 9 reports the estimates from the Table 1 analysis of attitudes to the COVID-19 response. The left is estimated at −0.4, or 1 on the ten-point scale and the right at (0.4, or 9 on the scale). Those on the right support the response but it matters little whether they are dispositional liberals or authoritarians. For those on the left, liberals support the response at extremely high levels but dispositional authoritarianism reduces that support to almost the level of those on the right.

Figure 9. How authoritarianism/liberalism conditioned by left-right position affects approval or disapproval of the COVID-19 response. Table 1, Model 5.

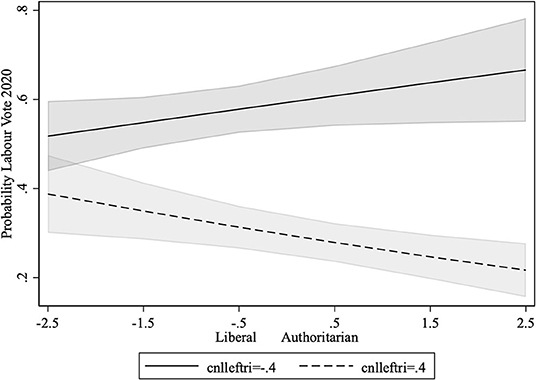

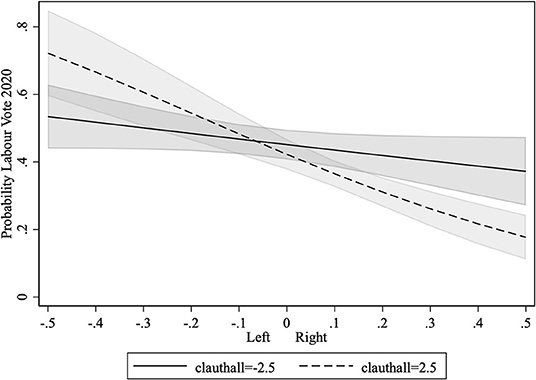

Figures 10, 11 show the effects of the interaction of the probability of change to Labour first conditioning liberal-authoritarian on left right, and next vice versa. Figure 10 shows a stark contract between those on the left and those on the right. The more authoritarian a person on the left, the more likely they will shift toward Labour; the more liberal, the less likely. Indeed statistically speaking the most liberal person on the left is almost as likely to have shifted to Labour as their counterpart on the right. But authoritarianism makes people on the right much less likely to vote Labour. Hypotheses 4 is strongly confirmed. Figure 10 stands the analysis on its head. Left-right differences polarize authoritarians, but are far less polarizing among liberals. It is notable that authoritarianism slightly drives the left away from COVID-19 response approval, but not from voting Labour, left position apparently overriding doubts about the COVD-19 response. Alternative models using authoritarian leadership in place of authoritarian disposition find no interactive effects at all.

Figure 10. How authoritarianism/liberalism conditioned by left-right position affects change to Labour. Table 2, Model 5.

Figure 11. How left-right position conditioned by authoritarianism/liberalism affects change to Labour. Table 2, Model 5.

At the outset, four hypotheses were advanced; the first, that experience of COVID-19 should generate higher levels of attitudinal authoritarianism than in the immediate past. As applied to a time trend between post-election samples elections in 1996 and 2020, the claim can be robustly rejected. New Zealanders' preferences for authoritarian leadership have been in decline over the last few years and COVID-19 has not disrupted that trend. No data is available to measure the underlying disposition toward or against authoritarianism before 2020, but one suspects that if such data existed, it would show much the same.

The second hypothesis proposed that a movement toward authoritarian dispositions and attitudes would be associated with support for the government's approach and a net gain in support for the government. There was no net movement toward a preference for authoritarian leadership, and panel analysis showed little or no sign that the individual-level movements that took place were as hypothesized. Those becoming more liberal were those most likely to move toward the government, although there was some evidence of a small countervailing left authoritarian shift in the other direction.

The third hypothesis posed two alternatives; that with high levels of trust either liberals or authoritarians would be most prone to favor the government response and shift to Labour. Liberals approved of the government response and were prone to shift to Labour almost entirely regardless of their trust or distrust of politicians. Trust in politicians led some authoritarians to favor the government response and shift to Labour. In terms of the broader pattern, liberals favored the government response and Labour, and authoritarians opposed both. Finally, hypothesis 4 proposed that left authoritarians would be more likely to support the response and Labour and right authoritarians would oppose it. Support for the response was high in general, but contrary to the hypothesis left dispositional authoritarians were somewhat less likely to support it than liberals. But the hypothesis that left authoritarians would be more likely to change to Labour and right authoritarians would not was strongly supported.

Discussion and Conclusions

The main thrust of the findings reported here should be of no surprise to anyone having paid attention to the mass politics of the COVID-19 response across the established democracies. While research on partisan differences in response in terms of the composition of governments remain at an early stage, opposition to strong government efforts to contain COVID-19 have been most apparent on the extreme right, where authoritarianism also tends to flourish. Liberal criticisms of what many perceive to be authoritarian government actions should be taken seriously, but in most cases those actions have not been justified by resort to authoritarian values. Instead, one sees the curious phenomenon of political movements identified with authoritarian values adopting liberal criticisms of the policy response in the name of freedom.

Philosophical justifications for governments' attempts to contain COVID-19 by way of lockdowns, at the most extreme, or other restrictive measures have not received much attention (although see Parker, 2021). The responses have been pragmatic, with their underlying values rarely explicit other than by very general statements. One can read some obvious consequentialist arguments into the policies: protection of individuals from the virus, and an unwillingness to throw the vulnerable to their fates as “the interest of everybody is sacred, or the interest of nobody” (Bentham, 1840, I, 144). Temporary sacrifice of liberty by some is justified to protect against greater harm to others. The otherwise adverse consequences of social disruption require a united response. For a short time, freedoms must be set aside in the interests of social cohesion. Scientific evidence is marshaled to model the consequences of failure to act, and the various strategies available.

Such arguments fall on stony ground for those whose explicit or implicit values are based on deontological arguments that identify ethical principles that must be applied regardless of consequences, and particularly as those consequences affect others. Such extreme rights-based arguments tend to be based on religious principles, or on other deeply held beliefs such as historical necessity, market-fundamentalism, or national or “racial” destinies8. These attitudes are widely found in political movements associated with social conservatism and authoritarianism. The social cohesion and compliance with authority demanded by these authoritarians is on their terms only.

New Zealand has been fortunate because the authoritarian response that paradoxically opposes COVID-19 restrictions has been much weaker than in other comparable countries. But these attitudes are found in a clustering of parties on the extreme right: the New Conservative Party, Vision New Zealand, the ONE party, and Advance New Zealand, summed together achieving just under three per cent of the party vote at the 2020 general election. The Advance New Zealand Party, in particular, incorporated the New Zealand Public Party, led by Billy Te Kahika. Based on internet-sourced misinformation, Te Kahikka denied the danger of COVID-19 and strongly opposed the government response. His party gained one per cent of the vote, unfortunately disproportionally concentrated among people of the Māori and Pasifika indigenous minorities who for genetic, socio-economic and historical reasons are highly vulnerable to the virus.

Average scores on the dispositional authoritarianism scale by groups of party voters are the highest over all other parties for these three right-wing parties at 3.31 out of six. National Party voters follow at 3.05, just above the mid-point, not far from New Zealand First at 2.92, with Labour voters at 2.45. Voters for the economically right-wing libertarian ACT party average on the non-authoritarian side at 2.69.

In the year following the 2020 election, against several incursions New Zealand continued to stem the tide of COVID-19 and, indeed was on the point of eliminating the Delta variant of the virus when the greatly more infectious Omicron version penetrated border controls at the beginning of 2022, making the strategy no longer possible. Because of relatively high vaccination rates, the prognosis was for sufficient suppression of the virus to protect the hospital system from overload, but this was by no means certain. The government's vaccination mandate required vaccination for access to all but essential services, and led to many who refused to be vaccinated losing their employment. It provided an opening for an extreme authoritarian response among a small but highly mobilized minority who either opposed vaccination itself, or merely the mandate. The next election in 2023 is likely to bring all these elements to the boil.

Around the world, analysis of COVID-19 responses has emphasized the importance of trust. Despite fears about an authoritarian response, only a few studies have addressed the matter or penetrated to the micro-level and fewer again have shifted attention to the analysis of its possible electoral effects. Here some largely unplowed ground has been tilled. Meanwhile the effects of cross-national variation in the partisan composition of governments have hitherto received little attention. Governments of the left and right, governments composed of parties that lean toward social conservatism or liberal values, and the very fact of being in government itself have been the first ports of call in a fresh research agenda (Rovny et al., 2022). This emerging literature focusses almost entirely on the United States and Europe and cross-national comparisons addressing the policy responses so far neglect the effects among the mass public (for example, Greer et al., 2020). The contrast between findings in Germany and New Zealand suggests there are many questions still to address when cross-national survey data can be brought to bear. It will almost certainly matter which sort of government is in power, centre-left or centre-right, not only for the substance of the response, but even more strongly in terms of how support for the government and its response will be shaped by the authoritarian-liberal dimension. Contrasting findings between New Zealand and Germany hint at this strongly. One can only speculate about a New Zealand counterfactual that would have been a National-led government in office in the time of COVID-19, with the same or perhaps a somewhat different response.

Thinking about authoritarianism in the context of a pandemic has also thrown up findings that challenge how we think about the concept in social science and how we identify it in mass public attitudes. In the name of freedom, authoritarian movements now challenge a policy response based on the values of the social cohesion that authoritarians are supposed to value. The answer to this paradox partly lies in differences between authoritarian leaders and authoritarian followers. Most authoritarian-liberal measures of mass attitudes apply to authoritarian submission, not dominance. But this may not be an entirely satisfactory explanation.

In the context of a post-COVID-19 election study, measuring authoritarian and liberal dispositions according to the CRV instrument has demonstrated its value by confirming some pertinent hypotheses and refuting others. Theoretically, one would have expected that attitudes about authoritarian leadership would have driven the analysis with the CRV dispositions more in the background. One can suggest two reasons authoritarian leadership failed to register. First, attitudes in favor of authoritarian leadership are a facet of New Zealand political culture, affecting even those otherwise of a liberal inclination, and thus lacking the punch normally expected. Second, it is possible that the ongoing COVID-19 crisis itself did had a triggering effect, making the CRV scale a more potent instrument that it might have been in normal times.

It may be, as Duckitt argues, that the CRVscale best estimates social conservatism and social liberalism. Its successful interaction with left-right position could indicate its value as an independent measure that cuts across left and right. However, a caution remains; the proportion of left authoritarians gleaned from tabular analysis of the data under examination here is very small. As Duckitt suggests, measures that draw on a dimension defined between consequentialism on the one side and extreme deontological values on the other might offer more promise for the future; as he puts it, “a broader conception of authoritarianism as a morally absolutist and intolerant desire for the coercive imposition of particular beliefs, values, way of life, and form of social organization on people irrespective of their wishes and of any human costs involved” (2022, p. 181).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be available in the Australian Data Archive https://ada.edu.au/. Data from 2017 and earlier are available through www.nzes.org.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Victoria University Human Ethics Committee. The ethics committee waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The 2020 NZES was funded by Victoria University of Wellington, the New Zealand Electoral Commission, and the Universities of Auckland and Otago.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.885299/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Identifying authoritarianism requires a term for its alternative. “Non-authoritarian” and “libertarian” are commonly used. The term “non-authoritarian” begs the question and the term “libertarian” is strongly associated with a radical right wing economic ideology, often associated with beliefs in the dominating force of the market that may approach authoritarianism. Here the term “liberal” is adopted.

2. ^For the government's position on the legal implications of its response see (Parker, 2021).

3. ^For recent review, theorization and operationalisation of the concept of social/interpersonal trust see Krueger and Meyer-Lindenberg, 2019.

4. ^The 2020 NZES is a post-election survey of a representative sample of the enrolled New Zealand electorate, also containing a panel made up of persons also participating in the 2017 NZES that was administered immediately after the 2017 general election. Administered by mail and online, it had a response rate of 32 per cent for those freshly sampled. It contains oversamples of younger voters and the Indigenous Māori population with weights applied by gender, age, Maori/non-Māori, education, and validated and reported vote. The 2020 dataset will be deposited in the Australian Data Archive by the end of 2022. Earlier datasets are available online at www.nzes.org.

5. ^This scale began its life with four items. Our six-item version of this scale applied in the 2020 NZES incorporated advice that it worked better with two additional items. Since then, a further two have been developed (Engelhardt et al., 2021).

6. ^This said, only 50 per cent expressed confidence in government in the New Zealand WVS sample taken before the pandemic. But this compares favourably to Germany (44 per cent), Australia (31 per cent) and the United States (31 per cent).

7. ^The probabilities are estimated at one up from the most liberal (-2.5) and one down from the most authoritarian [3.5 positions as there is a relatively small group who are the most extreme dispositional authoritarians (see Figure 4)].

8. ^Some of these themes emerge from Van Proojen and Krouwel (2019), which reviews literature seeking to find common ground between left and right-wing extremism.

References

Adolph, C., Amono, K., Bang-Jensen, B., Fullman, N., and Wilkerson, J. (2021). Pandemic politics: timing state-level social distancing responses to COVID-19. J. Health Polit. Policy Law 46, 211–233. doi: 10.1215/03616878-8802162

Adorno, T., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D., and Sanford, N. (1950). The Authoritarian Personality. Harper and Brothers.

Altiparmakis, A., Bojar, A., Brouard, S., Foucault, M., Kriesi, H. P., and Nadeau, R. (2021). Pandemic politics: policy evaluations of government responses to COVID-19. West Eur. Polit. 44, 1159–1179. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2021.1930754

Anesi, C. (2018). The F-Scale. Available online at: https://www.anesi.com/fscale.htm

Asbrock, F., Sibley, C., and Duckitt, J. (2010). Right-Wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation and the dimensions of generalized prejudice: a longitudinal test. Eur. J. Personality 24, 324–340. doi: 10.1002/per.746

Ausubel, D. (1965). The Fern and the Tiki: An American View of New Zealand National Character. New York, NY: Holt, Reinhart and Winston.

Baekgaard, M., Christensen, J., Madsen, J. K., and Mikkelsen, K. S. (2020). Rallying around the Flag in Times of Covid-19: societal lockdown and trust in democratic institutions. J. Behav. Public Adm. 3, 1–12. doi: 10.30636/jbpa.32.172

Beattie, A., and Rebecca, P. (2021). ‘We Rewatched Last Year's 1pm Briefings. Today, the Team of Five Million Needs a Pep Talk'. The Spinoff. Available online at: https://thespinoff.co.nz/politics/23-03-2021/we-rewatched-last-years-1pm-briefings-today-the-team-of-five-million-needs-a-pep-talk/ (accessed: March 23, 2021).

Bedggood, D. (1975). “Conflict and consensus: political ideology in New Zealand,” in New Zealand Politics: A Reader, ed L. Stephen (Melbourne: Cheshire), 299–311.

Bentham, J. (1840). Theory of Legislation. Translated from the French of Etienne Dumont, by Richard Hildreth, 2 vols. Bristol: Thoemmes Continuum (2004).

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., and Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: improving empirical analyses. Polit. Anal. 14, 63–82 doi: 10.1093/pan/mpi014

Cameron, B. (2020). Captaining a Team of 5 Million: New Zealand Beats Back Covid-19, March –June (2020). Global Challenges Covid-19. Princeton School of Public and International Affairs. Available online at: https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/publications/captaining-team-5-million-new-zealand-beats-back-covid-19-march-%E2%80%93-june-2020

Chapple, S., and Prickett, K. (2019). Who Do We Trust in New Zealand 2016. Wellington, Institute for Governance and Policy Studies (2019). Available online at: http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10063/8255/trust-publication-2019.pdf?sequence=1

Conway, L., Houck, S., Gornick, L., and Repke, M. (2018). Finding the Loch Ness monster: Left- wing authoritarianism in the United States. Polit. Psychol. 39, 1049–1069. doi: 10.1111/pops.12470

Costello, T. H., Bowes, S. M., Stevens, S. T., Waldman, I. D., and Lilienfeld, S. O. (2021). Clarifying the structure and nature of Left-Wing Authoritarianism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 122, 135–170. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000341

COVID-19 National Preparedness Collaborators (2022). Pandemic preparedness and COVID-19: an exploratory analysis of infection and fatality rates, and contextual factors associated with preparedness in 177 countries, from Jan 1, 2020 to Sept 30, 2021. Lancet. (2022) S0140-6736(22)00172-6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00172-6

Curtin, J., Greaves, L., and Vowles, J, . (ed.) (2022). A Team of Five Million? COVID-19. New Zealand General Election. Canberra, ANU Press, Under Review (2020).

Dalton, R. J. (2020). Citizen Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies, 7th ed. Los Angeles, Sage/CQ Press.

Dohle, S. T, Wingen, M., and Schreiber (2020). Acceptance and adoption of protective measures during the Covid-19 pandemic: the role of trust in politics and trust in science. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 15, 1–23. doi: 10.32872/spb.4315

Duckitt, J. (1989). Authoritarianism and group identification: a new view of an old construct. Polit. Psychol. 10, 63–84. doi: 10.2307/3791588

Duckitt, J. (2013). Authoritarianism in societal context: the role of threat [special section]. Int. J. Psychol. 48, 1–59. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.738298

Duckitt, J. (2022). “Authoritarianism,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Political Psychology, eds D. Osobnre, S. Sibley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). 177–197. doi: 10.1017/9781108779104.013

Dunn, K. (2020). The Authoritarian Predisposition, Perceived Threat, and Trust in Political Institutions. PsyArXiv 1–37. [preprint]. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/ewtdr

Engelhardt, A. M., Feldman, S., and Hetherington, M. J. (2021). Advancing the measurement of authoritarianism. Polit. Behav. doi: 10.1007/s11109-021-09718-6

Feldman, S., and Stenner, K. (1997). Perceived threat and authoritarianism. Polit. Psychol. 18, 741–770. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00077

Feldman, S., M?rola, V., and Dollman, J. (2021). “The Psychology of Authoritarianism and Support for Illiberal Policies and Parties,” in Routledge Handbook of Illiberalism, eds A. András Sajó, R. Uitz, and S. Holmes (Taylor and Frances). doi: 10.4324/9780367260569-46

Funk, A., and Linzer, I. (2020). How the Coronavirus Could Trigger a Backslide on Freedom Around the World, Editorial. Retrieved from The Washington Post. Available onine at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/03/16/how-coronavirus-could-trigger-~backslide-freedom-around-world/.

Gebrekidan, S. (2020). For Autocrats, and Others, Coronavirus Is a Chance to Grab Even More Power. New York Times. Available onine at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/30/world/europe/coronavirus-governments-power.html doi: 10.12968/prma.2020.30.8.30

Greer, S. L., King, E. J., Da Doncesca, E. M., and Peralta-Santos, A. (2020). The comparative politics of COVID-19: the need to understand government responses. Glob. Public Health 15, 1413–1416. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1783340

Grieve, D. (2020). ‘The Epic Story of NZ's Communications-Led Fight against Covid-19'. The Spinoff (2020). Available onine at: https://thespinoff.co.nz/politics/11-05-2020/a-masterclass-in-mass-communication-and-control/.

Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J, . (eds.). (2002). World Values Survey: Round Seven - Country-Pooled Datafile. Madrid, Spain and Vienna, Austria: JD Systems Institute and WVSA Secretariat.

Hartmann, T., Stocks, T. V. A., McKay, R., Gibson-Miller, J., Levita, L., Martinez, A. P., et al. (2021). The authoritarian dynamic during the COVID-19 pandemic: effects on nationalism and anti-immigrant sentiment. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 12, 1274–1285. doi: 10.1177/1948550620978023

IMF Fiscal Affairs Department (2021). Fiscal Monitor Database of Country Fiscal Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. IMF, New York. Available onine at: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Fiscal-Policies-Database-in-Response-to-COVID-19

J"ackle, S., Tr?dinger, E., Hildebrand, A. T, and Wagschal, U. (2022). A matter of trust: how political and social trust relate to the acceptance of Covid-19 policies in Germany. Ger. Polit. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2021.2021510

Janowitz, M., and Marwick, D. (1953). Authoritarianism and political behavior. Public Opin. Q. 17, 185–201. doi: 10.1086/266453

Johnson, C. (2020). The RWA Scale. Available onine at: http://www.panojohnson.com/automatons/rwa-scale.xhtml

Karwowski, M., Kowal, M., Groyecka, A., Białek, M., Lebuda, I., Sorokowska, A., et al. (2020). When in danger, turn right: does Covid-19 threat promote social conservatism and right-wing presidential candidates? Hum. Ethol. 35, 37–48, doi: 10.22330/he/35/037-048

Krueger, F., and Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2019). Toward a model of interpersonal trust drawn from neuroscience, psychology, and economics. Trends Neurosci. 42, 92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2018.10.004

Lamare, J., and Vowles, J. (1996). Party interests, public opinion, and institutional preferences: electoral system change in New Zealand. Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 31, 321–346. doi: 10.1080/10361149651085

Lexico (2022). Authoritarianism. Available onine at: https://www.lexico.com/definition/authoritarianism.

Maerz, S. F., Lührmann, A., Lachapelle, J., and Edgell, A. B. (2020). Worth the Sacrifice? Illiberal and authoritarian practices during COVID-19. SSRN Electron. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3701720

Manson, J. H. (2020). Right-wing authoritarianism, left-wing authoritarianism, and pandemic-mitigation authoritarianism. Pers. Individ. Dif. 167:110251. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110251

McLean, J., Rosen, A., Roughan, N., and Wall, J. (2021). Legality in times of emergency: assessing NZ's response to Covid-19. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 51, S197–S213. doi: 10.1080/03036758.2021.1900295

OECD (2020). Beyond Containment: Health Systems Responses to COVID-19 in the OECD. Available onine at: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=119_119689-ud5comtf84andtitle=Beyond_Containment:Health_systems_responses_to_COVID-19_in_the_OECD

Oleksy, T., Wnuk, A., Gambin, A., Lys, A., Bargiel-Matusiewicz, K., and Pisula, E. (2022). Barriers and facilitators of willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19: role of prosociality, authoritarianism and conspiracy mentality. A four-wave longitudinal study. Personal. Individ. Dif. 190:111524. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2022.111524

Pandemic Backsliding Project (2022). Pandemic Backsliding: Democracy During COVID-19 (March 2020 to June 2021). Available online at: https://www.v-dem.net/shiny/PanDem/

Parker, D. (2021). The Legal and Constitutional Implications of New Zealand's Fight Against COVID. Available onine at: https://www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/legal-and-constitutional-implications-new-zealand%E2%80%99s-fight-against-covid

Pazhoohi, F., and Kingstone, A. (2021). Associations of political orientation, xenophobia, right-wing authoritarianism, and concern of COVID-19: cognitive responses to an actual pathogen threat. Pers. Individ. Dif. 182:111081 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.111081

Porter, J. (2007). Using structural equation modeling to examine the relationship between political cynicism and right-wing authoritarianism. Sociol. Spectr. 28, 36–54. doi: 10.1080/02732170701675128

Prichard, E. C., and Christman, S. D. (2020) Authoritarianism, conspiracy beliefs, gender COVID-19: links between individual differences concern about COVID-19, mask wearing behaviors, the tendency to blame China for the virus. Front. Psychol. 11:597671. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.597671

Rieger, M. O., and Wang, M. (2021). Trust in government actions during the COVID-19 crisis. Soc. Indic. Res. 1–23. doi: 10.1007/s11205-021-02772-x

Rovny, J., Bakker, R., Hooghe L Jolly, S., Marks, G., Polk, J., Steenbergen, M., et al. (2022). Contesting Covid: the ideological bases of partisan responses to the Covid-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Polit. Res. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12510

Sanford, F. (1950). Authoritarianism and Leadership. Philadephia Institute for Research into Human Relations.

Satherley, N., Sibley, C. G., and Osborne, D. (2021). Ideology before party: social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism temporally precede political party support. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 60, 509–523. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12414

Sibley, C. G., and Duckitt, J. (2008). Personality and prejudice: a meta-analysis and theoretical review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 12, 248–279. doi: 10.1177/1088868308319226

Sibley, C. G., Greaves, L. M., Satherley, N., Wilson, M., Overall, N. C., Lee, C. H. J., et al. (2020). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdown on trust, attitudes toward government, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 75, 618–630. doi: 10.1037/amp0000662

Simandan, D., Rinner, C., and Capurri, V. (2021). Confronting the Rise of Authoritarianism During the COVID-19 Pandemic Should Be a Priority for Critical Geographers and Social Scientists. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies.

Stefaniak, A., Wohl, J. A., and Elgar, F. J. (2022). Commentary on “Different roles of interpersonal trust and institutional trust in COVID-19 pandemic control. Soc. Sci. Med. 299:114765. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114765

Stenner, K. (2005). The Authoritarian Dynamic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511614712

Tillman, E. (2021). Authoritarianism and the Evolution of West European Electoral Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780192896223.001.0001

Toshkov, D., Caroll, B., and Yesilkagit, K. (2021). Government capacity, societal trust or party preferences: what accounts for the variety of national policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe? J. Eur. Public Policy. doi: 10.31219/osf.io/7chpu

Van Assche, J., Dhont, K., and Pettigrew, T. F. (2019). The social-psychological bases of far-right support in Europe and the United States. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 29, 385–401. doi: 10.1002/casp.2407

Van Proojen, J., and Krouwel, A. (2019). Psychological features of extreme political ideologies. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 28, 159–163. doi: 10.1177/0963721418817755

Vowles, J., and Curtin, J, . (ed.) (2020). A Populist Exception? The 2017 New Zealand General Election. Canberra, ANU Press.

Vowles, J., Greaves, L., and Curtin, J. (2021). New Zealand Election Study. Dataset, University of Auckland/Victoria University of Wellington.

Weinberg, J. (2020). Can political trust help to explain elite policy support and public behaviour in times of crisis? Evidence from the United Kingdom at the height of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic. Polit. Stud. 1–25. doi: 10.1177/0032321720980900

Keywords: authoritarianism, COVID-19, New Zealand, election, public opinion, trust, left-right

Citation: Vowles J (2022) Authoritarianism and Mass Political Preferences in Times of COVID-19: The 2020 New Zealand General Election. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:885299. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.885299

Received: 27 February 2022; Accepted: 01 April 2022;

Published: 18 May 2022.

Edited by:

Daniel Stevens, University of Exeter, United KingdomReviewed by:

John Duckitt, The University of Auckland, New ZealandIan Mcallister, Australian National University, Australia

Copyright © 2022 Vowles. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jack Vowles, amFjay52b3dsZXNAdnV3LmFjLm56

Jack Vowles

Jack Vowles