94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY article

Front. Polit. Sci., 19 August 2022

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.870773

This article is part of the Research TopicOrigins, Foundations, Sustainability and Trip Lines of Good Governance: Archaeological and Historical ConsiderationsView all 14 articles

T. L. Thurston1,2*

T. L. Thurston1,2*What can the deep past tell us about how “good government” is instituted, replicated, and maintained through time? After a comparative look at late prehistoric political formation in Europe, a case study from Sweden is examined. During the Iron Age, systems of participatory governance developed across Europe, perhaps in response to the autocracies of the previous Bronze Age. Heterarchical structures with systems of checks and balances provided voice for ordinary people, as well as leaders, but there were clear “reversals of fortune,” as autocracy and more egalitarian structures were interspersed through time. The so-called “Long Iron Age” is consequently seen as an extended period of tension between different forms of government, different political ideologies, and the dynamic negotiation of socio-political norms, with repercussions that extend into recent times.

“Whenever I want to make some sort of a change for the better in administration, they straightway take to their pole-axes, and send round the bidding stick1 and most of all the Dalecarlians, who boast that they made me king, and are therefore entitled to immunities which no subjects should dream of claiming—they think that they ought to have the management of the State.”

What can the deep past tell us about how “good government” is instituted, replicated, and maintained through time? Feelings of what is fair—or “fair enough”—vary highly across societies, but in one form or another, seem to be a human social imperative1 (Ensminger and Henrich, 2014). How does a government reflecting—or tearing down—such culturally constructed notions come to be, and once in place, how does it persist?

To explore this question, this case study from Sweden will stretch back into the European Iron Age and forward into current times. The quote above comes from midway through this trajectory: a 1527 letter of Gustav Vasa, recently crowned king of Sweden. It might be imagined as the unremarkable complaint of a contemptuous ruler about some troublesome villeins. However, if carefully unpacked, it tells the story of over 2,500 years of political tension.

Vasa attained the throne, to which he was elected rather than born, only through the agency of these peasants, based on millennia-old social norms of shared governance. Soon after, Vasa seized them at traditional assemblies like the one where he had recently begged for their aid in throwing off foreign rule and avenging his murdered father, who had been seized at an assembly and killed by another king, who objected to the successful, long-term rule of Sweden's secular, non-royal administrators.

Throughlines of shared governance appear in many other ancient states, but a case study of Sweden is remarkably apropos; today Sweden is often held up to exemplify a model society with a responsive government and relatively little social stratification. This is of course more or less debatable (Syvertsen et al., 2014; Iqbal and Todi, 2015), but if we accept the general premise, we find that scholars trace the Swedish penchant for distributed power to various potential “beginnings.”

One of these is Folkhemmet, the period (1932–1976) when modern social democracy was established (Hirdman, 1995; Stråth, 1996). Others say it began during the later nineteenth century's labor unionism movements (Schön, 1982). Or was it the eighteenth century era of parliamentary rule, 1718–1772, called the “Age of Liberty” (Alestalo and Kuhnle, 1986; Rojas, 2005; Árnason and Wittrock, 2012)? Or did it begin with the numerous charters and constitutional documents of the 1300s, which claimed liberties and limited royal power that continued to be tweaked and amended into the early modern period (Rojas, 2005; Hervik, 2012; Korpiola, 2014)? While these are all important waymarkers, none constitute a “beginning.” If we seek something like a starting point, it is more likely traceable to the Iron Age, which, in this region, means 500 BCE−700 CE (Thurston, 2019a,b). Each waymarker was a response to a loss or erosion of rights in an extremely long, continuous political negotiation.

Shortly, we will look at the archaeological evidence for traditions of power sharing between rulers and ruled from the early Iron Age and into the so-called ‘Viking Age’ and beyond – the election of rulers, the existence of a common assembly, the primacy of law, the proscription of abusive leaders. The existence of these institutions in the Iron Age is not debated, they are common knowledge among historians, archaeologists, and the interested public.

What is rarely espoused is continuity between the deeper past and today, because, unlike historic and recent times, documentary transcripts are sporadic or lacking. There is archaeological evidence to fill in the gaps, but most archaeologists are unwilling to suggest such long-term continuities. Here again, Sweden, Scandinavia, and several other regions of Europe are among the global cases presenting optimal types of data, perhaps allowing us to extrapolate more widely.

This leads to the conceptual question at the heart of this offering. Once such governmental traditions and structures were originally won, can past people remember the history of their political struggles, or are they compelled to relearn the same lessons from scratch repeatedly, not for over a few generations, but for 1,000 years or more? Not a mythologized oral tradition, but a set of understandings about the rights achieved by their ancestors and their relationship with past leaders or rulers? Conceptually, it is not hard to reply that it can be achieved through the institutions of shared governance themselves, in which the issues and debates were reiterated over and over in a continuous cycle as each new challenge, coming in quick succession, was presented, especially where local or regional assemblies have deep histories and members maintain traditions of gathering regularly to discuss, debate, and/or legislate.

First, I briefly contextualize the case study (but see Thurston, 2010 for a fuller discussion). In hindsight, twentieth-century archaeologists did not do well with the study of either power or government. While this article's title references shared governance and decentralized power, we might review more fittingly how archaeologists have understood inequality through time (Thurston and Fernández-Götz, 2021).

Euro-American archaeologists of the nineteenth and early twentieth-centuries believed in a biologically determined, step-like social-evolutionary ladder leading from inchoate “savages” to hierarchical “civilizations.” If a political mechanism promoting equality was found in an ancient or traditional state society, it was deemed a “primitive” institution from the society's past. Euro-Americans' eighteenth and nineteenth-century attempts at constitutional monarchy, democracy, or federalism were excepted, with the a priori notion of Euro-American superiority. “Native” good government was uncouth, while Euro-American good government was leading-edge genius.

The entire notion of biologically determined stages of social evolution was being expunged by most academics in the 1920s and 30s, although, unfortunately, not always from the public consciousness. By the mid-twentieth-century, the bio-evolutionary ladder was replaced by a demographic “neo-evolutionary” ladder, where among other premises, the larger the polity, the more distant political participation becomes, and leadership becomes institutionalized and exclusionary. This era introduced the terms “band,” “tribe,” “chiefdom,” and “state” as ways of differentiating societies by scale. Monolithic and nearly obligatory until the late 1980s, this paradigm saw all large-scale societies as co-opted by powerful, managerially superior leaders, who made themselves absolute rulers by forcing, deceiving, or overawing their citizens into compliance or submission, using a variety of presumed legitimizing strategies. In fact, some archaeologists considered this an “achievement” (Chase and Chase, 1996, p. 803). The demos, or people, not only disappeared from theories of governance, but they also disappeared from existence in the archaeological literature.

Archaeologists, sometimes, call this phenomenon the “blob” effect; a term coined by Tringham (1991) in the late twentieth-century: the reduction of “masses” to mere implements for enacting the will of other, more important people. Archaeologists had long studied the detritus of ordinary people, but usually with the aim of saying something about their control, manipulation, undescribed, and/or generic use by elites. They could be divided into inhabitants of towns, regions, or provinces, or viewed as collective inhabitants of the nation. Tringham asked, “Why have archaeologists produced a prehistory of genderless, faceless blobs?”

Probably, the awe with which earlier archaeologists had viewed pyramids and palaces played a part in the willingness of mid- to late- 20th century archaeologists to maintain that the ancients apparently knew no other way to constitute the polity: only force or fear could produce state societies and magnificent cultural productions (Thurston and Fernández-Götz, 2021, p. 1).

However, by the 1990s, major paradigm shifts rocked the discipline with the realization that, as today, large-scale societies have always been organized in many ways. A century or more of accumulated archaeological data were re-examined and new data retrieved, little by little turning up many examples of less-hierarchical and less centralized policies where governance was shared.

In prehistoric and protohistoric times, different types of evidence for political change are most discernable: large swings in the structure of governments can be detected in slow, shifting spatial and organizational patterns of settlement, institutions, infrastructure, and landscape over time (Fargher and Blanton, 2021). Evidence of unrest can be seen in quick, singular, and tangible events like the destruction of a city, the remains of a battlefield, or the defacing of state monuments (Fernández-Götz and Arnold, 2019). These often speak for the entire context—equivalent to seeing the twentieth-century through a handful of scattered newspaper headlines. Missing are the actions and reactions of multiple overlapping generations of ordinary people, the interspersed years of waning and waxing advocacy, and the decades of clashes and decades of quiescence between people and the state.

If we could “see” this record, it would tell the story of how various (perhaps opposed) culturally “cherished” or hard-won rights, attached to specific political and social ideologies, persist over time, even during periods where the rights or privileges of one group or another, are eroded or repressed. Even though we will never have the facility of modern historic sources, ordinary people constitute the polity, and even if it is difficult to detect, we can be sure they existed. Between the sporadic headlines of prehistory, archaeologists find ways to fill in what is missing.

New concepts appeared toward the end of the twentieth-century: heterarchy, adopted from the natural sciences, was introduced into archaeology (Crumley, 1979, 1984; Crumley and Marquardt, 1987), describing societies that, instead of a centralized hierarchy, had several different but equally powerful authority structures that acted as checks and balances on each other, a way of reconciling vertical and horizontal organization (Cumming, 2016). Before long, the concept saw global application (e.g., Crumley, 1995; Saitta and McGuire, 1998; Mclntosh, 1999; O'Reilly, 2000; Chirikure et al., 2018; Grauer, 2021). The idea of the corporate state was also widely embraced, where authority was less concentrated in the hands of a few (Blanton et al., 1996). Such a society might be recognized by the absence or lessening of visible elite aggrandizement and the bolstering of more collectivity, an idea also incorporated into case studies the world over (e.g., Cowgill, 1997; Feinman et al., 2000; Robertshaw, 2003; Small, 2009).

One of the most recent and useful ways of conceptualizing the organization of large-scale ancient societies has been through collective action theory (CAT), a body of thought with a long history throughout the twentieth-century, distilled from many social sciences (e.g., Kendrick, 1939; Allport, 1940; Buchanan and Tullock, 1962; Olson, 1965; Ostrom, 1990, 1994; Ostrom et al., 1992; Congleton, 2015). Collective action, retooled and modified specifically for non-Western and ancient cases (Blanton and Fargher, 2008, 2016; Fargher and Blanton, 2021), describes how societies are organized in terms of the provision, or non-provision, of three kinds of affordances: fair and predictable taxation, public goods, and “voice.” The success of setting up a system capable of providing these affordances, termed bureaucratization, or the failure to do so, often predicts the level of stability and internal conflict within the polity. In this way, CAT explains both centralized, despotic autocracies and decentralized egalitarian democracies, as well as everything in between, equally well. Archaeologists, depending on the type of evidence recovered, usually have some methods for detecting these affordances.

Ironically, archaeologists long identified regimes bristling with internal enforcers and tax collectors, extracting high levels of labor and tribute, as “powerful” when their fundamental organization likely contained the stressors that caused their dissolution (Blanton and Fargher, 2008; Thurston, 2019a, p. 61). Counter-intuitively, CAT tells us that the regimes that seem to be the most “powerful”—militarized, repressive, and tyrannical—are the weakest. The most stable and easily governed societies are those in which people do not experience constant reminders of discontent. They need not be very good governments but just “good enough,” making them an apt tool of elite rulership, as well as a mechanism for at least a modicum of public wellbeing.

The payment of taxes or tribute can be seen through the organization of weights and measures, the location and context of coins and tokens, and non-defensive, administrative boundaries around sites of manufacture and trade, which often denote areas within which laws of the marketplace and protection from theft are provided by the state. Regularities in the sizes of house plots or fields over long periods are often interpreted as components of land-based taxation systems, as well as certain kinds of storage facilities and ancient toponyms referring to tithes or payments.

Tangible public goods and services can be seen in large-scale, transregional efforts, often with the hallmark of uniform state architectural styles or construction details, costly enough to be most easily attributed to rulers: road systems, bridges, port facilities, “built” marketplaces, monumentally defended borders, although care must be taken not to confuse “central” efforts with other large-scale projects that ordinary people are fully able to plan and carry out (cf. Fargher et al., 2019). Remarkably similar to modern public goods, these also benefited rulers, often through the long-term collection of use-fees, sometimes reasonable, sometimes not, as well as access to and taxation of whatever the demos were making, trading, or transporting.

“Voice,” or institutional venues, in which, and through which, the public can communicate with government, and in doing such, negotiate the terms under which they are governed, is a public voice for some portion of the citizenry. In many societies, assembly and voting locales are apparent materially or through toponyms, and early legal texts in many ancient societies often refer to traditions of assembly – with the caveat that there are clear cases where rulers introduce new rules into old agreements.

The establishment of such bureaucratization creates effective infrastructural power for the state (Blanton and Fargher, 2008), rather than giving its rulers heavy-handed personal power, and has the incidental effect of limiting elite ability to coerce or command with impunity (Fargher, 2016). For the state, bureaucratization is expensive and time-consuming to set up, but eventually creates governance that is relatively easy and cost-effective. Conversely, non-bureaucratized systems are money pits rendered weak by the need for thousands of tax collectors, enforcers, constabulary and military responses to unrest, and institutions to try, sentence, and punish those who resist or rebel. Moreover, these officials are often mired in corruption and malfeasance, siphoning off much of the revenue from taxes and fines meant for state coffers and oppressing taxpayers. Eventually, the “exit” of taxpayers, fed-up with failed government, from the tax rolls, through concealment or migration, further erodes the tax base and the ability to conscript labor (Scott, 2010).

If a change toward (or away from) a bureaucratized organization can be detected in periods with little or no documentary evidence, we can use CAT to hypothesize something about the causes and consequences of political change through time. The case study of Sweden presents a productive medium for this, as we can connect historic and proto-historical times with the early periods that have little or no documentary evidence by using archaeological patterns and data to hypothesize something about long term processes.

Reversal of fortune is an old phrase that originally refers to “luck” and references the goddess of luck, Fortuna, whom the Romans characterized as capricious. It has older roots in the Greek concept of peripeteia, a sudden reversal. Other Iron Age peoples, who were actively trading and interacting inter-regionally and with the Greeks, also likely shared this concept. This can mean an unintentional fall from a better to a worse condition, or the intentional undermining or removal of status. In terms of this discussion, it does not refer to any particular faction but only to the diminishment of whoever is in power. Here, it is used in reference to Haydu's (2010) concept of reiterated problem solving: how societies solve the same recurring problems, over and over, in somewhat different ways and in somewhat different circumstances. I return to this concept below.

The context of Mediterranean and Atlantic Europe provides several good case studies for the “wheel of fortune” that rolls over every party in turn. Before the Iron Age began, the Bronze Age cultures in the Mediterranean—the Mycenaeans, Hittites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Egyptians, and others, were largely elite-driven societies, low in collectivity with more centralized structures and powerful heads of state. Their political toolboxes comprised many top-down institutions. Around 1200 BCE, these societies began to collapse, one after the other, for what ancient historians frequently describe as somewhat mysterious reasons. For much of the twentieth-century, archaeologists characterized this as probably due to war-related or environmentally related economic disturbances in a highly connected world system, which at the time was the most popular way of explaining a “wave” of disruptive change. Today, we could say that whatever tipped the balance may have differed from region to region but is likely to have brought on social and political unrest as complex as any current global or regional eventful cascade.

Further to the west, the wave continued between 1100 and 750 BCE (Figure 1). In the central Mediterranean, archaeologically visible Greek Bronze Age elite culture “disappeared,” and based on material culture, society was transformed, marking the beginning of the Iron Age (Anderson, 2005; Kõiv, 2016). Between about 600 and 300 BCE, the system of governance called demokratia developed incrementally, also discussed by Fargher et al. (2022) in this issue, perhaps first in the Greek colonies of Sicily and from there spreading back to various Greek polities (Robinson, 2007). Despite the huge amount of political writing left behind by the Greeks, there is no explicit work dealing with democracy as a theory of government. Rather, in earlier periods there are treatises on isonomia, equal political participation, and isegoria, equality of speech, terms that became more important as democracy expanded over time (Raaflaub, 1983, p. 518).

In Athens, the most well-documented case, sometimes non-elite classes were pitted against tyrants and oligarchs, but often groups of elites battled each other (Forsdyke, 2005, p. 16) - those who believed in participatory government and those who believed that aristocratic intellectual and educational superiority made them the only group fit to rule - several thousand years before Madison and Jefferson. Thus, “the democratic notion of equality was under fire from the start... [many] noble, wealthy, educated, capable, experienced, and morally superior upper classes” (Raaflaub, 1983, p. 519) were strong critics of rule by “the poor, base, uneducated, incapable, and irresponsible masses” (Raaflaub, 1983, p. 519). Each side claimed that the opposing system was unequal, as it placed the rich over the poor, or the poor over the rich. Conversely, the earliest lists of Athenian archons show that great families with clear rivalries alternated their rulership. In other words, brief terms in office and electoral politics were devised mainly to create ‘fairness’ among the highest class and prevent violent squabbles – not solely to operationalize an ideology for the sake societal equality.

The role of inter-elite debates aligns well with CAT, as the collectivized government provides rulers the benefit of easier rulership over all classes. Greek democracy began with the noble, spread to the merely wealthy, then to agriculturalists who formed the warrior class, and lastly to the lowest class of the census: the thetes who rowed the ships of the Athenian fleet. Tellingly, they were described as the indispensable people without whom the city-state had no power or prosperity; here, perhaps, is a hidden transcript of enfranchisement negotiations through the affordance of “voice”—isegoria. Even at this point, only about 1 in 18 Athenian men were voters.

Beyond the ostensibly philosophical reflection of equal political participation, in practice, everyone was assigned certain civic duties: “the courts and the council, which supported the sovereign assembly in tasks of preparation and control, were manned by hundreds of citizens, thereby, truly representing the entire citizen body” (Raaflaub, 1983, p. 519). While this clearly spread power, it also spread effort and created a sense that service to the state was in one's own interest.

Talent, education, and skills were required for generals, financial administrators, and magistrates, so the law required that they be elected, and in early Athenian democracy, it was nearly always the aristocratic and wealthy classes that were most competent (Raaflaub, 1983, p. 519). Yet, in Athens at least, these leaders were elected by the people at assemblies (Stanton and Bicknell, 1987; Anderson, 2003) requiring a quorum of at least 6,000 citizens, which could be called by the public, or by leaders (Hansen, 1988, p. 53). Once in office, military and other leaders had to plead the case for their projects and initiatives. If the assembly did not support them, they did not go forward (Hamel, 1998).

In this democratic model, elected elites held the positions of military and economic decision-making but gained their power from lower class supporters who filled the ranks of low-level government. Those who supported oligarchy enjoined sub-elites to exercise their superiority and revoke the co-governance rights of the hoi polloi. The emergent event sequence was the side effect of these struggles, making it an inter-elite issue and “the development of the early poleis...cyclical and discontinuous” (Forsdyke, 2005, p. 16).

This minimal review is included only to contextualize Europe west of the Greek peninsula, where the early Iron Age period is almost completely prehistoric. As elsewhere, but a little later, from about 800 to 500 BCE, society was reorganized away from many Bronze Age regularities, yet still displayed authority invested in a wealthy elite culture. This period, called the Hallstatt era and sometimes the “First Iron Age,” saw numerous indigenous urban centers in Central Europe (Fernández-Götz and Krausse, 2013; Fernández-Götz, 2018) using Iron Age technologies, yet with spectacular Bronze Age-style wealth and a ruling class who were probably politically powerful. These polities were low in collectivity and, if they existed today, would be described as failed states (e.g., Rotberg, 2002).

Then, relatively abruptly, between 500 and 450 BCE, these elites “disappeared” in the archaeological sense, amid traces of violent internal conflicts, selective urban burning, destruction, and the cessation of elite construction and individualizing monumentality. A different kind of society emerged in the following La Tène period, sometimes referred to as the “Second Iron Age”, marked by signs of higher collectivity and good government (see below).

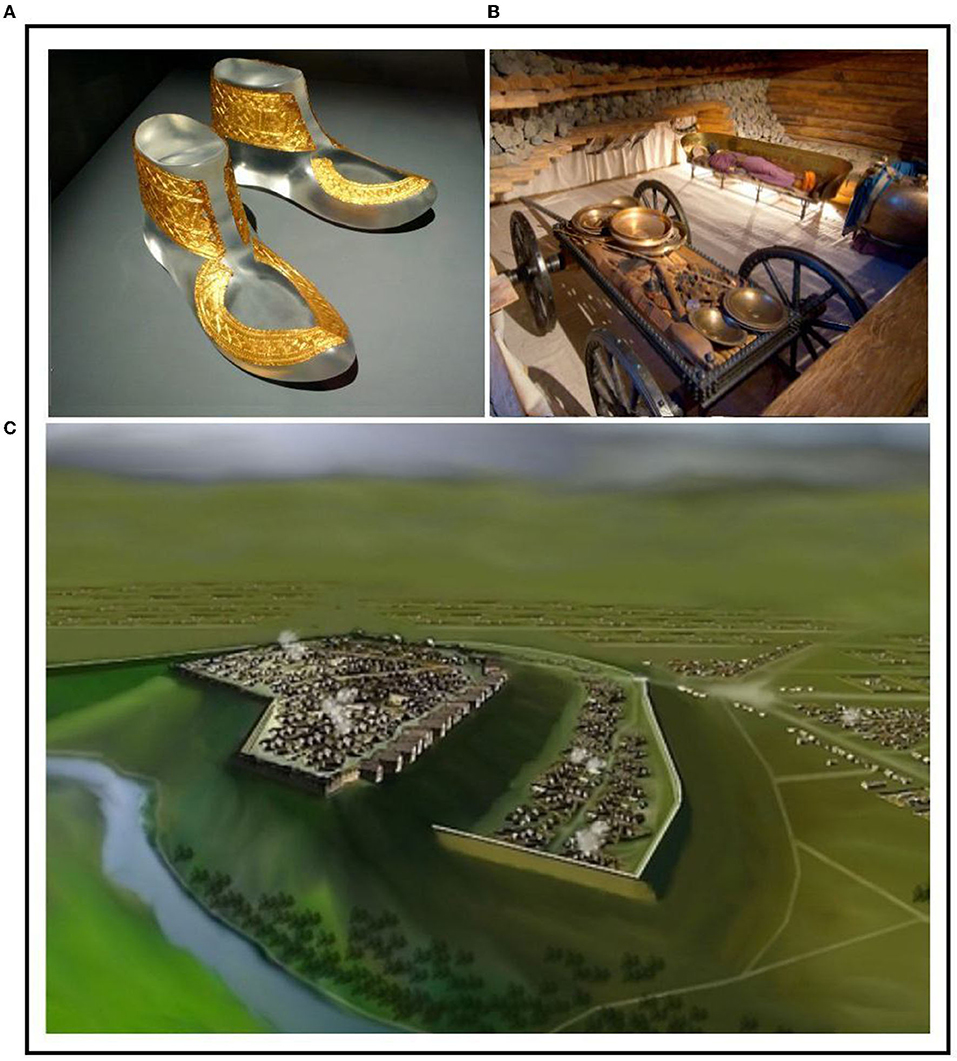

Once, it was assumed that the people behind this transition (ca. 620–450 BCE) were, in fact, emulating the Greeks themselves, whose democratic system was falling into place by the late sixth-century BCE. We now know that the processes in the east and west may have been largely contemporary; signs of internal conflict are seen at the Heuneburg urban's princely seat in what is now Germany between 530/540 BCE, followed by 3 more such episodes, accompanied by burning, destruction of ancestral images, and selective desecration of certain kin-group's graves (Fernández-Götz and Arnold, 2019). Pope (2021, p. 52), writing about the post-Hallstatt, pre-Roman era, described these Celtic-speaking people as, “fractured communities that disowned their past, [representing] a move against materialism in fourth century BCE Greece (Plato, Theopompus, Ephorus) that may then have begun at 550/540 BCE in the west with the active rejection of Greek-derived wealth, as typified by Hochdorf's golden shoes, in a move to an austere, egalitarian, and equitable north and west.” The golden shoes Pope refers to, found in a monumental grave of the vanished elite class, are a common synecdoche for the flagrant inequality of the Hallstatt era (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Hallstatt ‘First Iron Age’: (A) Hochdorf golden shoes (CC by 2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/rosemania/4120473429). (B) Hochdorf chieftain burial (CC by 2.5 https://www.flickr.com/photos/hagdorned/31711558200). (C) Heuneburg urban center (CC by 4.0 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heuneburg#/media/File:Heuneburg_600_B.C..jpg).

Today, “the role played by non-elites in transformative transitions has become a deliberate focus of archaeological research...investigating how commoners contribute to the social negotiation of dominant discourses through overlapping forms of social interaction, including engagement, avoidance, and resistance...these categories can be further subdivided into overt and subversive responses to internal as well as external stress. Labile socio-political systems like those of Iron Age Europe are subject to cyclical upheavals” (Fernández-Götz and Arnold, 2019, p. 658).

In La Tène cities, evidence emerged for public goods, including assembly places with voting facilities and sites for communal feasting, and indications of a heterarchic or corporate governing structure (Crumley, 1995; Fargher, 2016) with separate but equal institutions that shared power; each one internally ranked and each having checks and balances on the others: military professionals, law-keeping sacred specialists, and an assembly who met to seek legal recourse, debate community concerns, and elect leaders. Roman textual descriptions of this society appear in the first century BCE, but, generally, the prehistoric rupture between the Bronze Age and Iron Age is seen as the marker of the earliest change.

In the Celtic speaking regions, the strong, archaeologically visible break between 600 and 500 BCE, hinting at civil war or uprising, perhaps marks the beginning of a “democratic wave,” not unlike those in historical eras. Given the strong connection between Iron Age Central Europe and the Greek world's demokratia, were they part of wider simultaneous or overlapping sociopolitical changes?

Even without knowing the eventful history of this prehistoric era, we may draw some inferences. First, different groups of elites may have been at odds with each other, as in Athens. Given the large wealth gap in Early Iron Age urban centers, and what appears to be political and religious domination by a small group of families, there may also have been internal civil unrest from the lower classes—evidence perhaps of state failure—in light of Stewart's (2014, p. 47) four broad dimensions of horizontal inequalities that cause excluded groups to mobilize against other groups: economic issues such land ownership and wealth, social issues including health, services, and support networks; lack of access to political power at many levels, including overt governance, administrative bureaucracies, and military participation. The fourth and last dimension is what Stewart calls “cultural recognition or status”: the way one's group is treated within one's polity in terms of religion, language, and cultural productions like food, dress, arts, and other distinctions.

There is also evidence that spontaneous movements, running on anger alone, have great power to overthrow governments but ordinarily fail to effect lasting change (Weyland, 2014). The destruction in the “princely” towns at the transition from the early to the later Iron Age (Fernández-Götz and Arnold, 2019) might have been a spontaneous eruption after centuries of increasing elite-dominated inequality. Conversely, those led by experienced leaders with careful plans move more slowly but are far more successful over time (Weyland, 2014). The long-term erasure of elite culture and restructuring of institutions must have been well-planned: the overturning of the order succeeded, perhaps, beyond expectations, and the “checks and balances” remained for a long time.

For the study of such complex issues, then and now, critique has been leveled at researchers who confined their methods to atheoretical statistical models that are “unconvincing, schematic, and limited” (Weyland, 2019, p. 2,391). This might lie behind studies which, for example, inexplicably used statistical measures of vertical inequality between individuals to claim that there was no connection between inequality and internal conflict in societies (Collier and Hoeffler, 2004).

Certainly, vertical inequality, which means any poor person vs. any rich person, cannot explain or predict disruptive societal action. Even in nations (like modern Sweden) where there is a relatively egalitarian wealth and political structure, there are still substantial economic and political disparities (Buhaug et al., 2014, p. 424). Social scientists have acknowledged since the 1970s how groups use common identity (ethnicity, language, and religion) as instruments of mobilization (Barth, 1969), so, more recently, an ethnographic “mixed methods” approach has been taken for the “forecasting of conflict” (Ward et al., 2010, p. 364).

For example, Buhaug et al. (2014) created their own variables based on more narrative and ethnographic sources of data to measure horizontal inequality that explicitly refer to social groups within countries, establishing that there are indeed certain national or regional profiles associated with elevated risk for civil war, based on an outgroup's ethno-political and/or economic grievances, e.g., factors such as persistent inequality in the distribution of land between a specific subgroup and a ruling group.

This is good news for archaeologists. It would be difficult to create actual aggregate individual-level vertical data for a prehistoric period, but the position of an identifiable group relative to other groups or the larger society is something that archaeologists are good at identifying.

As the Romans under Julius Caesar conquered and wrote about the Gauls and other Celtic-speaking people, interpretations from prehistoric evidence are generally borne out (Fernández-Götz, 2014, p. 113; Fernández-Götz and Roymans, 2015, p. 20). They also described Germanic-speaking societies (Wells, 1999, 2009, 2011), including Scandinavia, especially in Tacitus' 98 CE Germania, an ethnographic account that includes these distant northern islands and peninsulas. While nineteenth and early twentieth-century archaeologists took Roman authors too literally (Arnold, 1990, 2004), more sophisticated approaches now reveal numerous archaeological findings that match details that the Romans described (Hedeager, 1992, 2011; Semple and Sanmark, 2013; Sanmark, 2017).

High northern Europe was farther away yet was still connected strongly to western and central European and Mediterranean spheres. Iron Age society was similar, but there were no first and second Iron Ages. Instead, after the Bronze Age collapse of elite culture came a “Long Iron Age,” from 500 BCE until around 700 CE, but, often, the following Viking Age is included, up until about 1000–1100 CE. Iron Age political and legal traditions lasted well into the medieval era, which, in Scandinavia, extends to the early-mid sixteenth-century, and as noted earlier, these, in turn, impact current forms.

Over the first five centuries, 500 - 1 BCE, there were few indexes of elite culture. Beginning in the first century CE, the Roman Iron Age, so-named due to interactions rather than conquest, locally made elite status markers and Roman imports appear, some interpreted as part of diplomatic exchanges (Herschend, 2009, p. 72; Grane, 2011, 2015). Slowly, burials, artifacts, architecture, and monuments show increasing display of social differentiation that had been long absent.

A Roman Iron Age cemetery connected with a single household gives a good example of sociopolitical change over several centuries (Stjernquist, 1955). Each group of graves, even the earliest, is associated with a set of separated and unfurnished graves that probably represent laborers, slaves, and other low status members of the household.

In the first century CE, a warrior-class presence is represented by a single male with a sword and some iron fittings. In the second century CE, there are five similar graves but with added bronze ornaments, combs, and finer ceramics, status markers but little inequality. In the third century, one has a shield, spear, lance, fine ceramics, and not only bronze, but silver ornaments. The richest contains spear and lance, spurs, shield, a sword with a scabbard ornamented with silver, gold foil, glass and beads, a coffer, and glass gaming pieces. A woman was buried with a silver collar, or torque, silver and bronze clasps and hairpins, and a diadem or headdress composed of blue glass, gold leaf, lead, and tin. By the fourth century, a “princely” chamber burial is occupied by a man with two gold rings, two silver rings, bronze ornaments, gaming pieces of bone and a gaming board, a comb, fine ceramics, a knife, a spear and lance, a sword and scabbard with silver and bronze ornaments, and a shield. The other male grave contains lower-level warrior equipment: a spear, lance, and comb. Of two females, one has bronze materials, the other a silver torque and pins.

The rich burials of the third and fourth centuries closely parallel later historic descriptions of powerful elite women, especially religious specialists, and the hierarchy within the warband: mounted chieftains, members of the retinue, and common soldiers. Other princely burials are found at sites that are evenly spaced across the landscape, perhaps a network of local rulers.

Despite this renewed social differentiation, we know that the outcomes were the heterarchically organized states of the Viking Age and early Middle Ages: along with influential militaristic families came the law-codes, the assembly, and pacts of mutual obligation. The slow creep of materially expressed elite status did not seem to displace these institutions, likely because warlords retinues consisted of 200 or 300 fulltime soldiers, while the larger forces of thousands needed for war or conquest were drawn from the farming class who insisted, in historical times, during face-to-face meetings with kings, that their rights should be no more or no less than those of their ancestors (Pálsson and Edwards, 1986, p. 55). They outnumbered professional fighters by vast ratios, and Viking Age and Medieval documents show that they were adamant about the maintenance of checks and balances (Thurston, 2010).

We now stand at the brink of where “pre-history” becomes “protohistory” and then “history.” For many generations of scholarship, these terms stood like heavy curtains, through which no one could see, making it conceptually impossible to connect them. We can see that certain forms and traditions persist, but what are the links between them, if any? Archaeologists who suggested throughlines across these invisible boundaries were dismissed (Randsborg, 1980, 1991; Kristiansen, 2000), but today, these curtains have been drawn back somewhat.

In the later twentieth century, questions of long-term processes were often addressed through contingency theory. Plainly stated, this means that whatever decisions people make in the present, are predicated upon what has happened in their past, and decisions made today constrain or shape the future. While many scholars still favor contingency, it has seen much critique. Some have rejected it, others attempt to improve it, and some are trying to rethink of it.

“The notion of contingency presents us with a quandary. We use it to designate what we do not know, what is outside the realm of an inquiry, or what eludes the grasp of an explanatory model...contingency has no fixed place and no content proper. Its boundaries are indefinitely extensible...It exists, so to speak, by proxy...Pointing to some form of indeterminacy lodged at the heart of the phenomena under consideration, it is supposed to tell us something about the nature of these phenomena” (Ermakoff, 2015, p. 64).

Contingency theorists look at long term chains of events, divided into episodes that might be single occasions, subtle series of minor events or trends, the actions of individuals or groups, or the creation of places or things. Tilly, in his discussion of mechanisms, processes, and episodes, identified episodes as “bounded streams of social life” (2001b, p. 26). Sewell noted that events are “unique and unpredictable sequences of happenings that must, by definition, be improvised on the spot” (Sewell, 1996, p. 868). Yet, such spontaneous events, situated in culture as they are, “take on aspects of ritual episodes [that] transform chaotic and contested politics into civilization-defining events” (Sewell, 1996, p. 871). Some scholars call this “event structure analysis” (Corsaro and Heise, 1990; Heise, 1991; Griffin, 1993, 2007; Hesse-Biber and Crofts, 2008) and have developed methods of tracing the causal relationships that drive trajectories along timelines. Some have also developed software to perform this complex modeling (Heise, 1989).

The most frequently critiqued aspect of contingency theory is a framework called path dependency. Path dependency organizes events into causal sequences that specify “how contingencies that may have steered a given case, like regime or an institution, in a direction different from that taken in another, similar case” (Haydu, 2010, p. 26). This becomes explanatory by identifying critical junctures, which foreclose options and steer history in one direction or another (Haydu, 2010, p. 29).

Explicit problems with path dependency are its assertion that contingent decision-making leads to “locked-in” sequences, where courses, once begun, are irreversible. This makes it difficult to explain frequently seen historical reversals (Haydu, 1998, p. 341)! Simple path dependency also “obscures larger trajectories across periods” (Haydu, 1998, p. 341). Some authors use it to explain only stability and not change.

Once considered a breakthrough, it was even adapted by several archaeologists in the late 1990s and early 2000s (Adams, 2001; Lucas, 2008). Remarkably, archaeologists are still discovering this approach, even calling it “new” (Jung and Gimatzidis, 2021), and in just the last few years, dozens of papers have appeared using this concept. In archaeology, path dependency is sometimes used merely as jargon for “the intuition that ‘history matters’ without a clear and convincing account of decision-making over time” (Kay, 2005, p. 554).

Vergne and Durand (2010) provided a strongly worded rebuke: authors must strongly reveal a link between causal decision-making and outcomes: the need for “specifying the missing link between theoretical and empirical path dependence. In particular, we suggest moving away from historical case studies of supposedly path-dependent processes to focus on more controlled research designs, such as simulations, experiments, and counterfactual investigation” (Vergne and Durand, 2010, p. 736–737).

Counterfactual investigation refers to testing a hypothesis about a causal chain of events by analyzing what would NOT have happened if a decision had been made in a different way or had the actual sequence of events or circumstances been different, or if a decision not been made at all.

Reiterated problem-solving is one of the solutions to the problems of path dependency. In an endorsement of so-called mixed methods, which unify qualitative and quantitative work, Haydu asserted like many others (Mishler, 1995; Franzosi, 1998) that

“Narrative has been widely prescribed as a cure...It promises to rejuvenate the study of class (and other group) formation, calling attention to how social actors construct meaningful stories of individual and collective identities by weaving together interpreted events... The analyst-as-storyteller identifies the ‘inherent logic,’ whereby, events alter the direction of social change and transform social structures, [and] event-structure analysis helps build the case that these connections are causal, rather than merely sequential connections, by using counterfactuals to ‘test’ assertions” (Haydu, 1998, p. 350).

Simply said, Haydu's concept allows that people have multiple options, that there is rarely a “lock in” because alternatives can always be found, minds and actions changed even at the last moment, resulting in significantly different outcomes. Figure 3 succinctly illustrates this difference.

Event structure analysis and similar frameworks are still considered emerging approaches within sociology (Hesse-Biber and Crofts, 2008) due to the many debates over the study of time and process, and battles between positivist empiricists and interpretive theorizers can get hot. “...We find intense interaction between historians and sociologists. We also find sharp disagreement. Questions of epistemology, ontology, and method align practitioners with competing answers to such questions as ‘What is an event?,’ ‘Can we detect causes in history?,’ and ‘Do all social processes result from individual choices?”' (Tilly, 2001a, p. 6,757).

Tilly noted that among political scientists, those focused on democratization have worked hardest to find legitimately comparable episodes to establish generalizations (Tilly, 2001b, p. 26) and to eliminate assumptions, “… that episodes grouped by similar criteria spring from similar causes....” The use of political event structure analysis has continued to be a productive approach by examining “contentious acts” through sites of regime power, a regime's acceptance of new actors, the stability of political relationships, potential allies or challengers, and the regime's repression or facilitation of collective claim-makers (Tilly and Tarrow, 2015, p. 59).

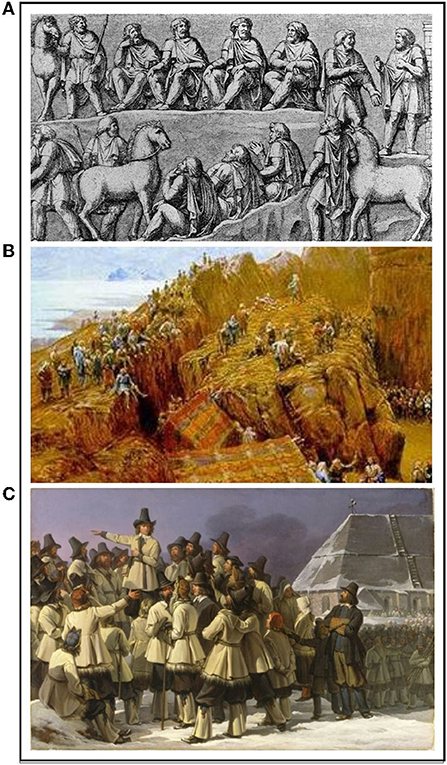

What the archaeological record has revealed in Sweden is similar to the rest of northern Europe: strong heterarchical or corporate institutions powered by common people despite the redevelopment of more visible and more powerful rulers (Figure 4). Roman accounts tell us that the assembly was in continuous use from the Iron Age, medieval chroniclers and missionaries attest to it in the early and later Viking Age, and it was a codified feature of government into the sixteenth century and beyond (Iversen, 2013; Oosthuizen, 2013; Riisøy, 2013; Smith, 2013): local, district and national thing-places, where actions, policies and laws were debated, and kings were elected by popular vote. A mid-fourteenth-century Swedish law code recommended that a king be elected from the king's sons, but that any man born in Sweden could be voted in.

Figure 4. The ‘Second Iron Age’ assembly in three eras: (A) Germanic thing, after a relief on the Column of Marcus Aurelius, c. 193 CE (public domain - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Germanische-ratsversammlung_1-1250x715.jpg). (B) Althing in Session (W. G. Collingwood, 1897), the law speaker of the Althing and the Icelandic parliament around CE 900-1000 (public domain - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._G._Collingwood#/media/File:Law_speaker.jpg). (C) On the church steps in Mora (J. G. Sandberg, 1836), Gustav Eriksson (later King Gustav Vasa) recruits Dalecarlian farmers to his cause (National Museum, Sweden, copyright-free collection, image 2451, https://www.nationalmuseum.se/samlingarna/fria-bilder).

Not surprisingly, there were opposing agents. In 1296, for example, one province sent a letter asking the Swedish king to update a particular regional code. A lawman was put in charge, he, in turn, selected 12 men from the nobility, clergy, wealthy commoners, and peasants who had knowledge of law and who had to collectively approve the amendment. The farmer class took part in the controls on the king and formulation and preservation of laws. Yet, by the fourteenth century, it seemed necessary to enact the so-called Swedish Magna Carta, the 1319 Charter of Liberties, a more formal pact between the king and the nobles, who claimed to protect the peasantry (Korpiola, 2014, p. 109).

In 1327, an almost identical letter arrived at court. This time, the appointed lawman selected only secular aristocracy, without members who were experts in the law. And, while in 1296 the panel of 12, including peasants, approved the final document, in 1327 it was simply proclaimed at many local assemblies, something of a sham exercise meant to resemble traditional events (Korpiola, 2014, p. 110).

Hence, in 1330, a new written and spoken oath was created for the king to swear upon his election to obey the law especially regarding taxation. This oath was incorporated into national law in 1350. The first Riksdag, or parliament, in Sweden, was established in 1435, its first iteration an invention of the nobility as resistance to royal excesses. Under government authority in 1527, it was explicitly directed to once more represent four groups: aristocrats, clergy, merchants, and farmers and other producers.

Sweden's law differed substantially from the English Magna Carta and other simultaneous constitutions enacted in Europe due to the traditionally

“electoral monarchy, the lack of true feudalism and serfdom, and the strong position of a landowning yeoman-type of peasantry…[and] lay dominance in the judiciary [that] came to be one of the cornerstones of Swedish legal cultural identity...[and] public territorial assemblies that formed the main venues for administration or legal affairs, resolving individual disputes, as well as making more general rules. Such traditions of ‘participatory justice’ continued at the local level until the High Middle Ages” (Korpiola, 2014, p. 96).

The linked chains of events in the protohistoric and historic eras, from the 800s to 1200s to 1500s, have self-referential mentions of how peasants referred to their own ancestors and ancient traditions, as well as complaints by many kings, in addition to Gustav Vasa's, whose response appears at the beginning of this article. Before this, there are “documentary gaps” between the era of the Franks and Roman times, and before the Romans, we rely solely on archaeological data and, perhaps, parallels with the Greeks, who were in regular trading and communication relations with the Celtic and Germanic-speaking peoples.

Tunisians had mass demonstrations and Syrians were like, “Hmm, interesting.”; And then, Egypt started. People were like, “Resign already!” and then, Mubarak resigned. We thought, “Holy shit. We have power.”—Syrian organizer, 2013, (cited in Gunitsky, 2018, p. 634)

“...the clue to an understanding of causal disruption... lies in a systematic analysis of how factors affecting individual agency can bring about breaks in patterns of social relations...distinguishing four types of impact:... A pyramidal impact rests on the existence of a hierarchical system of power relations. Pivotal impact is the action that decisively shifts a balance of power. Sequential impact describes the alignment of individual stances on observed behavior. Impact is epistemic when it affects beliefs that actors presume they are sharing” (Ermakoff, 2015, p. 66). The case study of Sweden as it emerges into historic times will illustrate these factors.

The utility of reiterated problem-solving lies in overcoming the domination of historical frameworks that cast a long record as a series of unrelated “ages” and a set of standard time periods defined by specific struggles. It is understandable that scholars examining a few decades to a couple of centuries view things in this way, yet with archaeological research, it becomes clear that they are part of longer and continuous cycles of conflict.

First, it appears that social memory has the potential to persist as long in pre- or non-literate societies as in those that are historically self-documented. In the absence of written records, practices for “remembering” are perfected. Many Iron Age groups eschewed written documents even when they could use them. The Celtic region's Druids used Greek script for ordinary transactions but would preserve law or religion only through memory. Germanic lawspeakers believed that written law could be corrupted by surreptitious amendments, which in historic times, it was! Once we imagine that the “ghosts of crises past” lived in minds of pre- and non-literate people, the reality of social memory is not so clouded.

More importantly, in the constant face of challenges between centralized and decentralized, authoritarian and democratic movements, the very act of affording oneself of “voice” in an assembly or other venue creates a continuous awareness of ongoing and long-term conflicts. Even in regions heavily disrupted by conquest or colonialism, this can persist; the value of a case where no such external disruption occurs, as with Sweden, is an object lesson in how this works.

The second argument is that many criteria used in the study of modern societies are equally present in all societies: rage at perceived injustice or atrocity, careful political plans made by leaders or through consensus, and understanding that vigilance is necessary to protect (any) sociopolitical ideals or systems from corruption.

At the close of the Late Bronze Age, when autocracies or oligarchies fell to more distributed governance principles, there were no instantaneous sources for news, but people were highly connected by continuous long-distance interactions flowing through professional messengers, long and short distance traders, and travelers. Additionally, while the cascade of prehistoric political collapses seems rapid, it is only archaeologically simultaneous, dated “together” with a +/– 100 or more years. This could be narrowed with Bayesian methods, but this has yet to be done for most sequences.

However, the outcomes of democratic diffusions are just as important for understanding how they occur than a precise timeline. Weyland summarized how such waves are observed to get underway: “1. protests surprisingly erupt after a long period of stagnation, 2. when participation in these protests quickly spirals to a large scale, and 3. when this mass contention achieves unusual success, especially the ouster of the incumbent ruler” (Weyland, 2019, p. 2,391).

The long sequence in our examples in Europe, stemming from the fall of highly stratified Bronze Age societies up to 3000 years ago, culminates here in the early modern era. I have not, and do not, claim to have performed an event structure analysis, as it lies beyond the scope of an article, but the following event sequence, especially when united with the late prehistoric, Iron Age and Viking Age record, awaits study and begs to be undertaken.

The historical archaeology of the mountainous Swedish province of Dalecarlia (modern Dalarna) and the province of Småland with its cold, high plateau has revealed that life for the people there was difficult but successful, fostering close-knit cooperative livelihood strategies. Communities were purposefully hidden in the folds of mountains and deep woods, making them difficult to surveil. Yet, they controlled many commodities (iron, wood, tar, charcoal) that were key to the state, especially to military supply (Cederholm, 2007; Thurston and Pettersson, 2022). In line with many ethnographic studies of people in such rugged regions, they relied on informal and formal mutual aid systems, and were fiercely protective of their rights (Cederholm, 2007; Thurston, 2018).

With the knowledge of the region's Iron Age and medieval traditions, we jump into the turbulent sixteenth century, 30 years of which are briefly outlined here to illustrate how ceaseless was the conflict between ideologies, and, hence, people. Sweden had been part of a triple alliance since 1397, nominally ruled by the Danish king, with regents in Norway and Sweden. In Sweden, there was a line of administrative caretakers, the Sture family, who had done a good job over several generations. The Stures dismissed the Danish diplomatic presence in 1470, but in 1513, a new Danish king, Christian II, aimed to take back full control of Sweden.

In early 1520 after defeating the Swedish army and causing the administrator's death, Christian proclaimed a full amnesty for the opposition, but after calling them to his coronation later in the year, “arrested ninety-six magnates, almost all of the nobles of the nationalist party, two bishops, and the burgomasters of Stockholm and other towns. They were all executed the next day after the semblance of a trial: this atrocity is generally known as the ‘Blood Bath of Stockholm’. After handing the administration of Sweden over to a colluding Archbishop... He imagined that he had won a complete victory by the extermination of the whole of the leaders... and returned to Copenhagen in triumph” [Oman, [1936 (2018)], p. 113].

Between 1521 and 1523, 25-year-old Gustav Ericson of Vasa, who was tangentially related to the Sture administrators, returned to Sweden; “...Luckily for him, he was not at home at the time of the Stockholm ‘Blood Bath,’ or he would have been one of its victims. His father Eric of Vasa, his brother-in-law and several more distant relations perished on the scaffold that day” [Oman, [1936 (2018)], p. 115].

Vasa was both enraged and ambitious. He was not royal and had none of the ascribed rights to rule that recent generations had maintained and could only rely on the still-current notion that “any man in Sweden” could be elected king. When he returned, he went straight to the Dales-men of Dalecarlia, where he knew he could find support for insurrection against Denmark. Their continued support enabled him to eventually gather an army and be elected “administrator.” As he prosecuted his war against the Danes, his forces swelled, he was victorious, and was crowned king in 1523.

However, the remnants of noble families taunted him with being the Peasant's King, “which was true enough, for it was with a peasant army that he had won his crown; the peasants looked upon him as their own man, whom they had made, and could possibly unmake if they grew discontented. Immense tact was required to keep them from being unduly casual, disobedient, and slow to pay taxes” [Oman, [1936 (2018)], p. 117]. “The Dalesmen had been Gustav's strongest and earliest supporters...they started grumbling about his actions... that he was becoming too strong and demanding too much of them [in] taxes and loans” (Satterlee, 2007, p. 95).

War necessitated taxes, and with so many nobles killed, many of the Dalesmen's old enemies were appointed to his administration. He also adopted Lutheranism, defying rural tradition. The Dalecarlians rose in rebellion three times: in 1524–1525, in 1527–1528, and in 1531–1533. In the first rebellion, the king persuaded them to stop by promising to meet their demands, but the leaders were extradited, tortured, and executed. In the second rebellion, Vasa called the Dalecarlian peasants to an assembly to negotiate, but then, demanded they turn over the rebels or every person in the district would be executed; this occurred and they were executed at the assembly. The third rising was similar, a tax rebellion where the king called them to an assembly to talk, but then forced payment, seized the rebels, and executed them instead.

The fact that, in a short decade, after calls to the assembly as part of an ancient and still active reciprocal arrangement, to then suffer arrest and execution rather than negotiation, was deeply shocking. They had acted on assumptions, without even thinking, that traditional ways were in order, and received entirely unexpected treatment. “These guiding assumptions are forms of tacit knowledge...these assumptions are not recognized as such. They are ingrained in how agents construct their situations, their decisions, and their actions. It follows that...the range of possible alternative courses of action that are scrutinized in the decision-making process is limited” (Kay, 2005, p. 564).

As noted above, movements that involve spontaneous emotion can at first have momentum, but usually fail. Weyland asked (Weyland, 2015, p. 494), “Do decision makers learn from the success of front-runners and assess the benefits and costs of their reforms in systematic, thorough, and rational ways? Or do innovative experiences serve as models that exert strong normative appeal and raise the standards of appropriate behavior, pushing latecomers toward imitation?”

Perhaps there was now time to adjust expectations before Sweden's other troublesome province rose. In 1536 and 1542, a wealthy Småland farmer called Nils Dacke is recorded as paying a blood money fine after his conviction in court for the killing of royal sheriffs over the collection of taxes. Later in 1542, Dacke emerged in command of a farmer army, and the fight was now clearly between rulers with different views on democracy. Dacke's army was far more organized and successful than the emotional response of the Dalecarlians, and Vasa's German mercenaries were massacred by battalions of crossbow-armed farmers in the unfamiliar dark forests and steep, rocky terrain. Then, Vasa cut off supply lines to Småland and labeled Dacke a heretic.

The rebellion spread throughout southern Sweden and along the Danish border, and Vasa, who realized the serious threat, signed a peace treaty that tacitly acknowledged Dacke as ruler of Småland. Dacke restored trade, lowered taxes, and re-established Catholicism. He was then courted by foreign powers who hoped to use developments to their advantage, but Dacke turned down offers of support. Vasa soon broke the treaty, and the following battles were not in the forest landscape; Dacke's forces were defeated, he was wounded and died on the border in 1543. Vasa sent his head and various pieces of his body to display across Sweden and imprisoned his family.

Why did Dacke turn down aid from foreign powers? It is unlikely he trusted Vasa after the Dalecarlian uprisings. If I were to construct an event structure analysis, I would first hypothesize that it was because as a leader, unlike Vasa, he expected to follow an old form of rulership, in which leadership was a temporary position, that he did not wish to be called a “king” or accept aid toward permanent rule in order to assure his followers he had no ambition to further erode the old legal and social codes.

Vasa next took what might seem inexplicable steps for a would-be authoritarian. Blaming the abuse of peasants on bailiffs he had appointed, he accepted the Småland farmers specific complaints, personally reviewed them, and replaced the tax collectors with “better” appointees (Hallenberg, 2012, p. 564). Additionally, he amended the Riksdag, or parliament, to explicitly include a forum where the farmers could present collective complaints (Hallenberg, 2012, p. 565), in the spirit of a king in the Iron Age. Fighting and repression were expensive: the bureaucratized state and collective action traditions made it easier, not harder, to rule the fractious and dangerous peasants because they accommodated voice and provided just taxation: a reversal of fortunes, but also of policies. This did not stop Sweden from moving toward short-lived autocracy in the 1600s, followed by an “Age of Liberty” in the 1700s.

Holenstein (2009, p. 2) noted that when states are constructed from below, the result, in later times, is often federalism or communalism of some type, created from an intersection of “moral concepts, corporate entities, interest groups,” and that this type of state building “no longer appears to be the exclusive achievement of dynasty members and their ministers, civil servants, and generals” (2009, p. 5). This is accomplished largely through institutions that constitute “empowering interactions.” For Medieval Sweden, Hallenberg (2012, p. 558) characterizes the relationship between Swedish kings and farmers as “empowering interactions” because “the bargaining over taxes was the most important social ritual connecting local society with the exercise of public power at the national level…This was not an exclusive top-down process: the negotiations also put political instruments into the hands of local agents who wanted a share in the growing authority of the state.”

“In a comparative perspective the Scandinavian peasantry seems both well-organized and disciplined...Whereas French peasants could protest by burning down the house of the local government agent, Scandinavian peasants usually wrote a petition and then sat down to wait for an answer from the king or his representatives. These differences should not be explained in terms of ‘national character' or other forms of folk psychology; rather they should be seen as products of different patterns of political socialization and organization over the centuries” (Löfgren, 1980, p. 198).

Vigilance is the best antidote. Consistent with CAT, Figure 5 illustrates the constant battle between peasants and kings over taxation, public goods and voice during the Middle Ages and Early Modern periods. We assume that prehistoric conflict was equally constant. This is what vigilance looks like, rendering unremarkable the notion that the same population could maintain ideological principles and pass on their imperatives to future generations. The process that began in prehistoric Sweden was a long series of continuous negotiations concerning older and newer institutions, laws, and roles, which went through periods of constructive change and others of violent chaos, a reiterated problem that needed solving.

This begs the question: if the Iron Age marked a period of change in reaction to the excesses of the Bronze Age, was that rejection couched within a kind of social memory of the pre-Bronze Age Neolithic, Mesolithic, and Ice Age models of more egalitarian societies co-evolving with the human species itself? Perhaps...but that is a question for another day.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^Budkavel (Old Swedish) were special torches, sent in all directions to rally people to assemblies, defense or rebellion. Magnus (2018) relates that those who did not bring the stick to the next village would be hanged and their homesteads burnt down.

Adams, R. M. (2001). Complexity in archaic states. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 20, 345–360. doi: 10.1006/jaar.2000.0377

Alestalo, M., and Kuhnle, S. (1986). 1. The scandinavian route: economic, social, and political developments in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. Int. J. Sociol. 16, 1–38. doi: 10.1080/15579336.1986.11769909

Allport, F. H. (1940). An event-system theory of collective action: with illustrations from economic and political phenomena and the production of war. J. Soc. Psychol. 11, 417–445. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1940.9918762

Anderson, G. (2003). The Athenian Experiment: Building An Imagined Political Community in Ancient Attica, 508–490 BC. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Anderson, G. (2005). Before turannoi were tyrants: rethinking a chapter of early Greek history. Class. Antiquity 24, 173–222. doi: 10.1525/ca.2005.24.2.173

Árnason, J. P., and Wittrock, B. (2012). “Introduction,” in Nordic Paths to Modernity, eds J. P. Árnason and B. Wittrock (Oxford; New York, NY: Berghahn Books), 1–23.

Arnold, B. (1990). The past as propaganda: totalitarian archaeology in Nazi Germany. Antiquity 64, 464–478. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00078376

Arnold, B. (2004). “Dealing with the devil the faustian bargain of archaeology under dictatorship,” in Archaeology Under Dictatorship, eds M. L. Galaty, and C. Watkinson (Boston, MA: Springer), 191–212. doi: 10.1007/0-387-36214-2_9

Barth, F. (1969). “Introduction,” in Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Difference, ed F. Barth (Boston, MA: Little, Brown), 9–38.

Blanton, R., and Fargher, L. (2008). Collective Action in the Formation of Pre-Modern States. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73877-2

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. (2016). How Humans Cooperate: Confronting the Challenges of Collective Action. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Blanton, R. E., Feinman, G. M., Kowalewski, S. A., and Peregrine, P. N. (1996). A dual-processual theory for the evolution of mesoamerican civilization. Curr. Anthropol. 37, 1–14.

Buchanan, J. M., and Tullock, G. (1962). The Calculus of Consent, Vol. 3. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Buhaug, H., Cederman, L. E., and Gleditsch, K. S. (2014). Square pegs in round holes: Inequalities, grievances, and civil war. Int. Stud. Q. 58, 418–431. doi: 10.1111/isqu.12068

Cederholm, M. (2007). De värjde sin rätt: Senmedeltida bondemotstånd i Skåne och Småland [They Defended Their Rights: Late Medieval Peasant Resistance in Scania and Småland]. Lund: Lunds University Press.

Chase, A. F., and Chase, D. Z. (1996). More than kin and king: Centralized political organization among the late classic Maya. Curr. Anthropol. 37, 803–810.

Chirikure, S., Mukwende, T., Moffett, A. J., Nyamushosho, R. T., Bandama, F., and House, M. (2018). No big brother here: heterarchy, shona political succession and the relationship between Great Zimbabwe and Khami, southern Africa. Camb. Archaeol. J. 28, 45–66. doi: 10.1017/S0959774317000555

Collier, P., and Hoeffler, A. (2004). Greed and grievance in civil war. Oxford Econ. Pap. 56, 563–595. doi: 10.1093/oep/gpf064

Congleton, R. D. (2015). The logic of collective action and beyond. Public Choice 164, 217–234. doi: 10.1007/s11127-015-0266-7

Corsaro, W. A., and Heise, D. R. (1990). Event structure models from ethnographic data. Sociol. Methodol. 20, 1–57. doi: 10.2307/271081

Cowgill, G. L. (1997). State and society at Teotihuacan, Mexico. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 26, 129–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.26.1.129

Crumley, C. L. (1979). Three locational models: An epistemological assessment for anthropology and archaeology. Adv. Archaeol. Method Theor. 1979, 141–173.

Crumley, C. L. (1984). “A diachronic model for settlement and land use in southern Burgundy,” Archaeological Approaches to Medieval Europe, ed K. Biddick (Kalamazoo: The Medieval Institute), 239–243.

Crumley, C. L. (1995). “Heterarchy and the analysis of complex societies,” in Heterarchy and the Analysis of Complex Societies, eds R. M. Ehrenreich, C. L. Crumley, and J. E. Levy (Washington, DC: Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association), 1–5. doi: 10.1525/ap3a.1995.6.1.1

Crumley, C. L., and Marquardt, W. H. (1987). Regional dynamics in Burgundy. Regional dynamics: Burgundian landscapes in historical perspective, New York: Academc Press, pp. 73–79.

Cumming, G. S. (2016). Heterarchies: reconciling networks and hierarchies. Trend. Ecol. Evolut. 31, 622–632. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2016.04.009

Ensminger, J., and Henrich, J, (eds). (2014). “Introduction, project history, and guide to the volume,” in Experimenting With Social Norms: Fairness and Punishment in Cross-Cultural Perspective. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 3–18.

Ermakoff, I. (2015). The structure of contingency. Am. J. Sociol. 121, 64–125. Available online at: https://sociology.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/466/2019/08/2015-Ermakoff-Structure-of-Contingency.pdf

Fargher, L. F. (2016). “Corporate power strategies, collective action, and control of principals: A cross-cultural perspective,” in Alternative Pathways to Complexity, eds L. F. Fargher and V. Y. H. Espinoza, 309–326.

Fargher, L. F., and Blanton, R. E. (2021). “Peasants, agricultural intensification, and collective action in premodern states,” in Power from Below in Premodern Societies: The Dynamics of Political Complexity in the Archaeological Record, eds T. L. Thurston., and M. Fernandez-Götz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 157–174. doi: 10.1017/9781009042826.008

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., and Antorcha-Pedemonte, R. R. (2019). 11 The archaeology of intermediate-scale socio-spatial units in urban landscapes. Archeol. Pap. Am. Anthropol. Assoc. 30, 159–179.

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., and Heredia Espinoza, V. Y. (2022). Collective action, good government, and democracy in Tlaxcallan, Mexico: an analysis based on demokratia. Front. Polit. Sci. 4, 832440. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.832440

Feinman, G. M., Lightfoot, K. G., and Upham, S. (2000). Political hierarchies and organizational strategies in the Puebloan Southwest. Am. Antiquity 65, 449–470. doi: 10.2307/2694530

Fernández-Götz, M. (2014). Sanctuaries and ancestor worship at the origin of the oppida. Mousaios 19, 111–132.

Fernández-Götz, M. (2018). Urbanization in iron age Europe: trajectories, patterns, and social dynamics. J. Archaeol. Res. 26, 117–162. doi: 10.1007/s10814-017-9107-1

Fernández-Götz, M., and Arnold, B. (2019). Internal conflict in iron age Europe: methodological challenges and possible scenarios. World Archaeol. 51, 654–672. doi: 10.1080/00438243.2020.1723682

Fernández-Götz, M., and Krausse, D. (2013). Rethinking early iron age urbanisation in central Europe: the Heuneburg site and its archaeological environment. Antiquity 87, 473–487. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00049073

Fernández-Götz, M., and Roymans, N. (2015). The politics of identity: late iron age sanctuaries in the Rhineland. J. N. Atlant. 8, 18–32. doi: 10.3721/037.002.sp803

Forsdyke, S. (2005). Exile, Ostracism, and Democracy: The Politics of Expulsion in Ancient Greece. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Franzosi, R. (1998). Narrative analysis—or why (and how) sociologists should be interested in narrative. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 24, 517–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.517

Grane, T. (2011). Varpelev, denmark - evidence of roman diplomacy? Bollettino di Archeologia on line, Edizione Speciale congresso di Archeologia A.I.A.C 2008, 37–44. Available online at: www.archeologia.beniculturali.it/pages/pubblicazioni.html (accessed December 10, 2014).

Grane, T. (2015). “Germanic veterans of the roman army in southern scandinavia-can we identify them?” in Proceedings of the 22nd Congress of Roman Frontier Studies (Ruse), 459–464.

Grauer, K. C. (2021). Heterarchical political ecology: Commoner and elite (meta) physical access to water at the ancient Maya city of Aventura, Belize. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 62, 101301. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2021.101301

Griffin, L. J. (1993). Narrative, event-structure analysis, and causal interpretation in historical sociology. Am. J. Sociol. 98, 1094–1133. doi: 10.1086/230140

Griffin, L. J. (2007). Historical sociology, narrative and event-structure analysis: fifteen years later. Sociologica 1, 1–17. doi: 10.2383/25956

Gunitsky, S. (2018). Democratic waves in historical perspective. Perspect. Polit. 16, 634–651. doi: 10.1017/S1537592718001044

Hallenberg, M. (2012). For the wealth of the realm: the transformation of the public sphere in Swedish politics, c. 1434–1650. Scand. J. Hist. 37, 557–577. doi: 10.1080/03468755.2012.716638

Hamel, D. (1998). Athenian Generals: Military Authority in the Classical Period. Leiden; New York, NY: Brill. doi: 10.1163/9789004351486

Hansen, M. H. (1988). The organization of the athenian assembly: A reply. Greek Roman Byzantine Stud. 29, 51–58.

Haydu, J. (1998). Making use of the past: time periods as cases to compare and as sequences of problem solving. Am. J. Sociol. 104, 339–371. doi: 10.1086/210041

Haydu, J. (2010). Reversals of fortune: path dependency, problem solving, and temporal cases. Theory Soc. 39, 25–48. doi: 10.1007/s11186-009-9098-0

Hedeager, L. (1992). Iron-Age Societies: From Tribe to State in Northern Europe, 500 BC to AD 700. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hedeager, L. (2011). Iron Age Myth and Materiality: An Archaeology of Scandinavia AD 400-1000. Leiden; New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203829714

Heise, D. (1989). Modeling event structures. J. Math. Sociol. 14, 139–169. doi: 10.1080/0022250X.1989.9990048

Heise, D. (1991). “Event structure analysis: a qualitative model of quantitative research,” in Using Computers in Qualitative Research, eds N. Fielding, and R. Lee (London: Sage), 136–163.

Herschend, F. (2009). The Early Iron Age in South Scandinavia: Social Order in Settlement and Landscape. Occasional Papers in Archaeology No. 46. Uppsala: Department of Archaeology and Ancient History.

Hervik, F. (2012). “The nordic countries,” in The Edinburgh Companion to the History of Democracy, eds B. Isakhan and S. Stockwell (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 143–153.

Hesse-Biber, S. N., and Crofts, C. (2008). “User-centered perspective on qualitative data analysis software: emergent technologies and future trends,” in Handbook of Emergent Methods (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 655–675.

Hirdman, Y. (1995). Att Lägga Livet Till Rätta: Studier i Svensk Folkhemspolitik. Stockholm: Carlssons.

Holenstein, A. (2009): “Introduction: empowering interactions: looking at statebuilding from below,” in Empowering Interactions. Political Cultures and the Emergence of the State in Europe 1300–1900, eds W. Blockmans, A. Holenstein, J. Mathieu, and D. Schäppi (New York, NY: Routledge), 1–31.

Iqbal, R., and Todi, P. (2015). The Nordic model: existence, emergence and sustainability. Proc. Econ. Fin. 30, 336–351. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01301-5

Iversen, F. (2013). Concilium and pagus - revisiting the early Germanic thing system of northern Europe. J. No. Atlant. 5, 5–17. doi: 10.3721/037.002.sp507

Jung, R., and Gimatzidis, S. (2021). “An introduction to the critique of archaeological economy,” in The Critique of Archaeological Economy (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-72539-6_1

Kay, A. (2005). A critique of the use of path dependency in policy studies. Public Admin. 83, 553–571. doi: 10.1111/j.0033-3298.2005.00462.x

Kõiv, M. (2016). Basileus, tyrannos and polis. The dynamics of monarchy in early Greece. Klio 98, 1–89. doi: 10.1515/klio-2016-0001

Korpiola, M. (2014). ‘Not without the consent and goodwill of the common people': the community as a legal authority in medieval Sweden. J. Legal Hist. 35, 95–119. doi: 10.1080/01440365.2014.925173

Löfgren, O. (1980). Historical perspectives on Scandinavian peasantries. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 9, 187–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.an.09.100180.001155

Lucas, G. (2008). Time and archaeological event. Camb. Archaeol. J. 18, 59–65. doi: 10.1017/S095977430800005X

Magnus, O. (2018). Olaus Magnus, A Description of the Northern Peoples, 1555: Volume III. Oxford; New York, NY: Routledge.

Mclntosh, S. K. (1999). Floodplains and the development of complex society: comparative perspectives from the west African semi-arid tropics. Archeol. Pap. Am. Anthropol. Assoc. 9, 151–165. doi: 10.1525/ap3a.1999.9.1.151

Mishler, E. G. (1995). Models of narrative analysis: a typology. J. Narrat. Life Hist. 5, 87–123. doi: 10.1075/jnlh.5.2.01mod

Oman, C. [1936 (2018)]. Tendencies And Individuals. Gustavus Vasa and Scandinavian Protestantism the Sixteenth Century. London: Routledge Revivals.

Oosthuizen, S. (2013). Beyond hierarchy: the archaeology of collective governance. World Archaeol. 45, 714–729. doi: 10.1080/00438243.2013.847634

O'Reilly, D. J. (2000). From the bronze age to the iron age in thailand: applying the heterarchical approach. Asian Perspect. 39, 1–19. doi: 10.1353/asi.2000.0010

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511807763