- 1Department of Social and Cultural Sciences, Fulda University of Applied Sciences, Fulda, Germany

- 2Department of Democracy Studies, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany

Based on a genealogy of the concept of Legitimacy, the goal of the paper is to develop a proposal that unites normative-theoretical and empirical approaches and hence reconciles two different conceptual-theoretical camps in legitimacy research. Legitimacy is a core concept in Political Science that relates to fundamental questions of politics, polity and policy–the relation between rulers and ruled, the properties of a political system, its democratic quality, the rule of law, and its policy output. However, in academia, no consensus has evolved on the conceptual and empirical core of legitimacy, it is still essentially contested. One main reason for this is that a concept such as legitimacy is not only a tool for analysis, but can also become an object of academic controversy itself, as researchers give different answers to key questions related to conceptualizing it. This is why academic controversies on a concept highlight key issues, questions and dimensions of understanding, defining, and operationalising it—which is also the case for legitimacy. The paper therefore recollects the main controversies around the concept of legitimacy since the 1950's by tracing a genealogy of legitimacy in the Social Sciences. A genealogy is a methodological tool in intellectual and conceptual history. Different from a classical literature review, a genealogy summarizes the main lines and traditions of thinking on a concept, the key controversies, predominant understandings, and crucial issues of conceptualizing it. In the conceptual debates on legitimacy in Political Science, the core controversy is the one between normative-theoretical and empirical approaches. Based on the genealogy, we develop a proposal for conceptualizing legitimacy that enables to reconcile the normative-theoretical and empirical camps in legitimacy research.

Introduction

Concepts in Political Science have several functions (see in detail Wiesner et al., 2018). A decisive one is that they serve as tools, or lenses, to analyse reality. Legitimacy is one core concept in Political Science. It relates to fundamental questions of politics, polity and policy – the relation between rulers and ruled, the properties of a political system, its democratic quality, the rule of law, and its policy output, to name but a few (on the following see also Wiesner and Harfst, 2019b). Moreover, the concept of legitimacy refers to normative and theoretical as well as empirical dimensions of research. After one or two decades in which the topic seemed to be rather marginalized, academic discussions on legitimacy have been on the rise in recent years (see, e.g., Ferrin and Kriesi, 2016; Wiesner and Harfst, 2019a; Kneip and Merkel, 2020).

However, in the academic debate, no consensus has evolved on the conception of legitimacy. The concept of legitimacy (still) is essentially contested (Gallie, 1955) in the Social Sciences—besides a core understanding (see below and Section Reconciling camps: a proposal), there is little agreement on how it should be correctly understood and operationalised. This is not only because of the concept's multidimensional character (Beetham, 1991, p. 4; Kaase, 1985). The interrelation between the normative-theoretical conceptualization of legitimacy and the empirical measurement of legitimacy is a crucial issue and a crucial tension that has proven difficult to resolve. Thus, this relation has been theorized and operationalised in very different ways by different authors.

One main reason behind this and other controversies is that a concept is not only a tool for analysis, but can also become an object of academic controversy itself. Usages, meanings and interpretations of concepts in academia relate to key questions of different epochs and academic circles—they are subject to academic controversies. Moreover, different researchers give different answers to key questions related to conceptualizing it. This is why academic controversies on a concept highlight key questions and dimensions of understanding, defining, and operationalising it (on conceptual controversies see in detail Wiesner et al., 2018; Wiesner, 2020)—which is also the case for legitimacy. This is why in the following these key questions of conceptualizing legitimacy are assembled via an analysis of the main controversies around the concept, i.e., by tracing a genealogy (Urbinati, 2006; Skinner, 2009) of legitimacy in the academic debate in the Social Sciences. On this basis, it is the principled aim of this article to develop a conceptual solution for the dilemmata of operationalising legitimacy that will be discussed in the course of the genealogy. The conceptual matrix presented in Section Reconciling camps: a proposal allows to integrate and reconcile both a normative-theoretical and an empirical perspective on legitimacy.

In all this, we depart from the basic definition that legitimacy is to be understood as the “worthiness of a political order to be recognized as such” (Anerkennungswürdigkeit einer politischen Ordnung, Habermas, 1976, p. 39). This is also a conceptual core common to most definitions of legitimacy that will be discussed in the following.

Furthermore, as also spelt out in the introduction to this symposium, we distinguish three dimensions of legitimacy (Scharpf, 1999; Schmidt, 2013; see also the discussion in Wiesner and Harfst, 2019b):

The input dimension refers to the citizen's input into the system (e.g., the principle of popular sovereignty and the popular election of political leaders).

The throughput or system dimension refers to the system's political processes (e.g., the rule of law and the democratic quality of the political system and its institutions).

The output dimension refers to (a) a system's policy output and (b) the effectiveness and efficiency of its policies.

After having said what we understand by legitimacy, we will also spell out what we will not discuss. The dimensions sketched above have to be distinguished from legitimation, or the process(es) through which legitimacy is acquired and reproduced. The present article focuses on the concept of legitimacy as a state, leaving the process of legitimation aside (on distinction between legitimacy and legitimation see Barker, 2001, p. 1–29).

To be precise, we further argue that a number of concepts and items that usually belong to the classics in legitimacy analysis actually need to be differentiated from legitimacy (see Wiesner and Harfst, 2019b; the list could be expanded, see Norris, 1999):

a) Support for a polity (Easton, 1953, 1975).

b) Identification with the polity (Easton, 1953, 1975).

c) Satisfaction with democracy (see, e.g., Linde and Ekmann, 2003; Ferrin and Kriesi, 2016).

We do not understand any of these three concepts as being identical to legitimacy. Neither do we discuss in this paper related approaches and fields that study similar phenomena 1.

Legitimacy: Genealogy of an essentially contested concept

The path to conceptualizing legitimacy involves several steps. In particular, researchers need to position themselves regarding the normative-theoretical and the empirical dimensions of the concept. A genealogy of legitimacy in the Social Sciences highlights a number of key controversies that are related to the steps of conceptualizing legitimacy (on these controversies see also Stillman, 1974; Denitch, 1979; Schaar, 1984; Beetham, 1991; Kneip and Merkel, 2020).

A genealogy is a methodological tool in intellectual and conceptual history (on the concept of representation see Urbinati, 2006; on the concept of the state see Skinner, 2009). Different from a classical literature review, a genealogy summarizes the main lines and traditions of thinking on a concept, the key controversies, predominant understandings, and crucial issues of conceptualizing it. The goal of the following genealogy therefore is accordingly to trace these controversies, different understandings and core questions. The criterion for selection of the literature in the following accordingly is the relevance and contribution of a respective text to the conceptual debate on legitimacy. It focuses on those contributions that made crucial arguments and emphasize the key issues of the conceptual controversy.

In the conceptual debates on legitimacy in Political Science, the core controversy is the one between normative-theoretical and empirical approaches. But it is not only the concept of legitimacy and its normative-theoretical foundation that is controversial, it is also the relation of normative-theoretical and empirical dimensions in the conceptualization. In particular, as will be discussed in Section Reconciling camps: a proposal below, it is decisive to decide whether a system that is deemed legitimate by its citizens empirically can also be judged as legitimate when it does not comply to normative-theoretical standards of legitimate regimes.

This relates to the fact that measuring legitimacy involves, on the one hand, to measure legitimacy empirically, in the sense of the citizen's belief that the actions of a government are right and coherent to their views and values. Whether the actions and decisions of an institution can be found to be legitimate (or not) is then a matter of whether these are perceived to be legitimate (or not). These perceptions classically are measured with surveys, i.e., quantitative-empirical tools. A crucial issue about these empirically oriented understandings is their subjectivity, as will be discussed in the genealogy below: if and when researchers base the judgement of a system as “legitimate” solely on empirical indicators of citizens' beliefs in the legitimacy of this system, an autocracy that is believed to be legitimate by its citizens would have to be classified as a legitimate system.

To avoid this, a judgement on legitimacy, on the other hand, also involves a normative-theoretical judgement of a specific regime's worthiness to be recognized. As argued by several authors in the debate on legitimacy (see especially Beetham, 1991; Kneip and Merkel, 2020), there are good arguments to base this external judgement on criteria that refer, first, to the accordance between the actions of a ruler or a government and the basic criteria of the rule of law. The rule of law includes a balance of powers between legislative, executive and judicial institutions and an established set of laws and civil and political rights that are legally and politically enacted and controlled. A normative-theoretical judgement should, second, also include the citizen's expressed consent to the ruler or government. This would usually involve free and fair elections.

Besides this dilemma between empirical-analytical and normative approaches to legitimacy, controversies focus on the appropriate operationalisation of legitimacy, the conceptual fit of existing operationalisations, and suitable methods and techniques for its analysis. In the following we will trace these conceptual controversies.

We begin our genealogy with the decisive conceptual move in the academic debate on legitimacy that marked the turn toward empirical-analytical legitimacy models. It is to be situated in the US-American debate of the 1950's: following a period in which legitimacy had mainly been conceptualized with a purely theoretical or normative-theoretical orientation, political science now focused on the empirics.

The 1950's: The empirical turn

In 1952, the “Social Science Research Council's Interuniversity Research Seminar on Comparative Politics” at Northwestern University2 discussed the theoretical and empirical foundations of political legitimacy, with a focus on empirical and measurement questions. The Symposium's discussion is related to a more general debate in political science on the field's culture and methods, and to the question whether political science should shift from descriptive and normative to empirical-analytical approaches.

Roy Macridis and Richard Cox reported the symposium results in a report that proposes to re-orient comparative political science toward an analytical founding of research questions, concept formation, and criteria for comparison, rather than focusing on descriptive studies of institutions. It also presents decisive conceptual moves for the future understanding of political legitimacy (Macridis and Cox, 1953).

“The function of politics, in the total social system, is to provide society with social decisions having the force and the status of legitimacy. A social decision has the force of legitimacy if the collective regularized power of the society is brought to bear against deviations and if there is a predominant disposition among those subject to the decision to comply” (Macridis and Cox, 1953, p. 648–49).

However, the symposium itself did not yet use the concept of legitimacy, but the one of “legitimacy myth”:

“Concepts of legitimacy or “legitimacy myths” are the highly varied ways in which people justify coercion, conformity, and the loss of political ultimacy to some superior groups or persons, as well as the ways by which a society rationalizes its ascription of political ultimacy and the beliefs which account for a predisposition to compliance with social decisions” (Macridis and Cox, 1953, p. 649).

In the seminar's understanding, a legitimacy myth defines the conditions of individuals' obedience to political rule. Politics itself is part of a battle for legitimacy. The groups struggling for legitimacy aim at recognition and, ultimately, the realization of their respective political goals, which is equivalent to legitimacy. Legitimacy then means the political reflection of a society's value system, which is itself the result of politics (Macridis and Cox, 1953, p. 649). In further specification, the seminar report continues that,

“Some of the group were of the opinion that the concept of the legitimacy myth needed some clarification in order to be made operationally useful. It was suggested therefore that the legitimacy myth concept be viewed as an amalgam of four operational concepts: (a) habitual acquiescence; (b) the partial internalization of command; (c) self-involvement; and (d) structural transfer to other social stereotypes” (Macridis and Cox, 1953, p. 650).

In 1959, Seymour Martin Lipset went a step further when he defined legitimacy and economic development as two “[…] structural characteristics of a society which sustain a democratic political system” (Lipset, 1959, p. 71). Legitimacy is furthermore closely linked to a system's efficiency–while for Lipset efficiency relates to the system's performance, “legitimacy is more affective and evaluative” (Lipset, 1959, p. 86). Legitimacy, finally, is conceptualized as independent of the regime type:

“Groups will regard a political system as legitimate or illegitimate according to the way in which its values fit in with their primary values. […] Legitimacy, in and of itself, may be associated with many forms of political organization, including oppressive ones” (Lipset, 1959, p. 86).

Lipset furthermore argues that a loss of legitimacy will occur alongside decisive social transitions—in cases where not all relevant groups in society are represented in the political system, or if the status of central institutions is threatened, legitimacy can be lost (Lipset, 1959, p. 86–87).

In sum, these key contributions to the academic debates of the 1950's resulted in a broad consensus that legitimacy need to be studied empirically, based on an analytical approach. Lipset's work is a model case for this approach. He summarizes legitimacy as an affective and evaluative resource of system stability, at the same level as a system's effectiveness and its economic development. This conception has close similarities to Easton's concept of system support (Easton, 1953, 1975).

1970's and beyond: Criticism of capitalism, or the return of normative-theoretical approaches

In the years post-1950's the academic debate on legitimacy ebbed off. It revived in the course of the economic crises of the 1970's. It is interesting to note that, in fit with the 1968 student uprising and its critical impetus, legitimacy debates also took on a decidedly critical stance, often in opposition to the analytical approaches of the 1950's. In particular, a number of authors highlighted that the examination of legitimacy should transcend empirical-analytical approaches and begin to (re-)incorporate normative-theoretical perspectives.

A core contribution to this debate comes from Schaar (1984). He undertakes a conceptual move to criticize empirical analytical legitimacy concepts and toward a normative-theoretical legitimacy conception. In his discussion of the “legitimacy crisis” of the 1970's, Schaar (1984) therefore characterizes Lipset's concept of legitimacy as an uncritical, system-oriented approach equating political legitimacy and mere opinion. He argues in favor of a more comprehensive legitimacy concept–without, however, making suggestions for it. But Schaar sums up three critical points in analytical legitimacy definitions. First, based on a comparison of definitions of political legitimacy in encyclopedias with current definitions in analytical sociology, he states that the latter leave important dimensions of previous conceptions of legitimacy aside: “The new definitions all dissolve legitimacy into belief or opinion” (Schaar, 1984, p. 108). Accordingly, Schaar criticizes that, if legitimacy is merely understood as legitimacy belief, public opinion alone would be enough to decide whether a regime can be considered as legitimate or not. Second, he states that it is not evident what it is that the empirical measurements concretely show: “[…] legitimacy and acquiescence, and legitimacy and consensus, are not the same, and the relations between them are heterogeneous” (Schaar, 1984, p. 109). Third, and finally, Schaar is critical of a bias in the analytical models that follows from the dominant approaches. If legitimacy is regarded as a system's capacity to convince citizens of its worthiness to be recognized, only top-down dynamics are analyzed:

“The flow is from leaders to followers. […] The regime or the leaders provide the stimuli, first in the form of policies improving citizen welfare and later in the form of symbolic materials which function as secondary reinforcements, and the followers provide the responses, in the form of favorable attitudes toward the stimulators” (Schaar, 1984, p. 109).

Accordingly, Schaar ends with a strongly critical account of empirical legitimacy concepts:

“Legitimacy, then, is almost entirely a matter of sentiment. Followers believe in a regime, or have faith in it, and that is what legitimacy is. The faith may be the product of conditioning, or it may be the fruit of symbolic bedazzlement, but in neither case is it in any significant degree the work of reason, judgment, or active participation in the processes of rule” (Schaar, 1984, p. 109).

Schaar's arguments are particularly interesting for a genealogy of the concept, since they underline four core questions of conceptualizing legitimacy:

1) Should legitimacy be conceptualized in purely analytical terms, with an emphasis on its measurement, or should empirical and normative-theoretical dimensions be integrated?

2) If legitimacy covers both empirical-analytical and normative dimensions, how should these be related to one another in their operationalisation?

3) What are the good criteria and items for measuring or analyzing legitimacy?

4) What relations and interrelations between rulers and ruled do we assume (top-down and/or bottom-up)?

In a similar vein, (Connolly, 1984, p. 224) criticizes “thin” conceptions of legitimacy because they postulate that (a) political systems are supported until open opposition appears, (b) legitimacy belief is equated with legitimacy, (c) orientations which are at the basis of legitimacy are also the ones that carry the political order, and (d) goals and means of political systems are rational and hence legitimate. These postulates, Connolly argues further, invite a number of fallacies:

“First, if the preunderstandings implicit in social relations seriously misconstrue the range of possibilities inherent in the order, expressions of allegiance at one moment will rest upon a series of illusions which may become apparent at a future moment. […] Second, a widespread commitment to the constitutional principles of the political order may be matched by distantiation from the role imperatives governing everyday life. […] Third, the ends and purposes fostered by an order can themselves become objects of disaffection. […] Fourth, the identities of the participants are bound up with the institutions in which they are implicated” (Connolly, 1984, p. 224).

Based on a more normative-theoretically grounded understanding of legitimacy, Connolly furthermore discusses the legitimacy of capitalism. He highlights that a legitimacy crisis of capitalism occurred in the 1970's:

“First, the ends fostered by the civilizations of productivity no longer can command reflective allegiance of many who are implicated in those institutions, while the consolidation of these institutions into a structure of interdependencies makes it extremely difficult to recast the ends to be pursued” (Connolly, 1984, p. 232).

Habermas (1976, 1984) similarly sees such a legitimacy crisis of capitalism as given, arguing that Western welfare states are not strong enough to fully compensate the dysfunctionalities of capitalism. Since western welfare states continue to justify the capitalist order that produces unsatisfactory outputs, they face a crisis of legitimacy (Habermas, 1976, p. 50–52, 1984). For Habermas, legitimacy crises also explain the conjunctures in academic debate: He argues that the concept of legitimacy is usually debated when the legitimacy of a certain political order is threatened (Habermas, 1976, p. 39).

Taken together, the contributions by Schaar, Connolly and Habermas point to two more crucial conceptual questions:

5) What does it mean for the legitimacy of a political system if its basic principles (such as a capitalist economy) are no longer supported by relevant parts of the population?

6) The output dimension of legitimacy has a decisive function. If policy output is not judged satisfactory any longer, not only system support, but also legitimacy can face crises: But what is the turning point in this respect? Which degree of legitimacy loss is critical, and from which degree of legitimacy loss onwards does a system face troubles?

The 1990's: Reconciling normative-theoretical and analytical approaches

The conceptual debate on legitimacy took the next crucial turn in the 1990's. With Beetham's (1991) contribution the debate on legitimacy intensified again. Beetham proposes a path for reconciling normative-theoretical and analytical approaches in legitimacy research. To do so, he introduces the concept of justification:

“A given power relation is not legitimate because people believe it is but because it can be justified in terms of their beliefs. We are making an assessment of a degree of congruence, or lack of it, between a given system of power and the beliefs, values and expectations that provide its justification. We are not making a report on people's beliefs in legitimacy” (Beetham, 1991, p. 11).

Beetham further argues (Beetham, 1991, p. 13–25), that because of this need for justification, legitimacy needs to be studied in context, i.e., by testing if the legitimacy judgements of the population are in fit with predominant values. In the following he argues that a lawyer, a philosopher, and a social scientist would each add different dimensions to legitimacy. Accordingly, argues Beetham, a first dimension of legitimacy relates to rules, with power being legitimate “[…] if it is acquired and exercised in accordance with established rules” (Beetham, 1991, p. 16).

Since such legal validity is insufficient for securing legitimacy, he continues, the rules face the need of justification in terms of beliefs shared by both dominant and subordinate. At this point, Beetham also highlights the crucial question of the good degree needed for a satisfactory justification and its potential contestedness: “Naturally, what counts as an adequate or sufficient justification will be more open to dispute than what is legally valid” (Beetham, 1991, p. 17). As a third dimension, Beetham introduces “[…] the demonstrable expression of consent on the part of the subordinate […] through actions which provide evidence of consent” (Beetham, 1991, p. 18).

These arguments bring Beetham toward a threefold matrix of legitimacy and its opposites (Beetham, 1991, p. 20):

1. Conformity to rules (legal validity), with the opposite of illegitimacy.

2. Justifiability of rules in terms of shared beliefs, with the opposite of a legitimacy deficit stemming from a discrepancy between rules and supporting beliefs.

3. Legitimation through expressed consent, with the opposite of delegitimation, i.e., the withdrawal of consent.

Reconciling camps: A proposal

As the genealogy has shown, despite decades of academic debate on legitimacy, legitimacy research still faces core conceptual questions and problems:

1) Should legitimacy be conceptualized in purely analytical terms, with an emphasis on its measurement, or should empirical and normative-theoretical dimensions be integrated?

2) If legitimacy covers both empirical-analytical and normative dimensions, how should these be related to one another in their operationalisation?

3) What are the good criteria and items for measuring or analyzing legitimacy?

4) What relations and interrelations between rulers and ruled do we assume (top-down and/or bottom-up)?

5) What does it mean for the legitimacy of a political system if its basic principles (such as a capitalist economy) are no longer supported by relevant parts of the population?

6) The output dimension of legitimacy has a decisive function. If policy output is not judged satisfactory any longer, not only system support, but also legitimacy can face crises: But what is the turning point in this respect? Which degree of legitimacy loss is critical, and from which degree of legitimacy loss onwards does a system face troubles?

In the following, we will not be able to answer all of these questions, but we can tackle some of them. We will concentrate especially on the first one, but give some preliminary answers to the second and the fourth questions.

The above underlines that in order to conceptualize legitimacy, researchers need to answer these questions and take positions. First, they have to clarify whether they understand legitimacy primarily, or solely, as a normative-theoretical concept or if they seek a concept that can be measured empirically (Schaar, 1984; Beetham, 1991). More recent research on legitimacy has come to the agreement that legitimacy always unites both dimensions (e.g., Kriesi, 2013), i.e., a normative and an empirical dimension, which need to be related theoretically and conceptually. We take this claim as a first step of approaching the concept of legitimacy. Against this backdrop, we depart from the definition mentioned in the beginning: legitimacy is to be understood as the “worthiness of a political order to be recognized as such” (Habermas, 1976, p. 39).

This involves both a subjective-empirical and a normative-theoretical definition of legitimacy. One is needed to compensate for the limitations of the other. The empirical analytical definition of legitimacy is a subjective one: it maps citizens' beliefs on the rightfulness of their government's actions and whether these actions are coherent to their views and values. It follows that if researchers judge a system as “legitimate” solely based on empirical indicators of citizens' beliefs in its legitimacy, an autocracy can be found to be legitimate. To avoid such counter-intuitive results, judgements on legitimacy have to involve a normative-theoretical judgement of a specific regime's worthiness to be recognized.

In answer to question (1), should legitimacy be conceptualized analytically, with an emphasis on legitimacy measurement, or it if should also be judged normatively?, we thus opt for the second solution. Having thus decided on the fundamental relation between the normative-theoretical and empirical-analytical dimensions of the concept, we will now proceed toward a proposal to reconcile and integrate normative-theoretical and empirical approaches to legitimacy.

In accordance with most contemporary legitimacy research (e.g., Kriesi, 2013), we thus argue that normative-theoretical conceptualization of legitimacy and empirical operationalisations need to inform each other (Wiesner and Harfst, 2019b). Hence, our proposal includes an empirical and a normative component. Regarding the second question—whether legitimacy covers both empirical-analytical and normative dimensions and how these should be related to one another in their operationalisation? —the answer is more complicated. Even if we depart from the Habermasian definition of legitimacy as a worthiness of a political order to be recognized, we soon encounter the question how to decide on and how to measure what is “worthy to be recognized.” But Habermas also opens a path toward reconciling normative-theoretical and analytical dimensions of the concept of legitimacy. His definition of legitimacy as a political order's “worthiness to be recognized” (Habermas, 1976, p. 39) enables both these understandings. He further underlines that every legitimacy claim must be justified in the views of those who grant legitimacy–but this, he stresses, does not mean to confuse legitimate orders and orders that are only understood as being legitimate (Habermas, 1976, p. 55). Habermas therefore proposes legitimacy as a concept to include both the acceptance of legitimacy claims and the reasons given for this (Habermas, 1976, p. 58).

This argument is quite similar to Beetham's (1991), and his threefold matrix of legitimacy and its opposites (Beetham, 1991, p. 20), including Conformity to rules (legal validity), with the opposite of illegitimacy; Justifiability of rules in terms of shared beliefs, with the opposite of a legitimacy deficit stemming from a discrepancy between rules and supporting beliefs; and Legitimation through expressed consent, with the opposite of delegitimation, i.e., the withdrawal of consent.

This means that an integration of empirical and normative-theoretical dimensions of legitimacy into one model requires to relate the quality dimensions of this system and their perception by the citizens. In order to move further toward an inclusive model of normative-theoretical and empirical dimensions of legitimacy analysis, we return to discussing the benefits and limits of both approaches.

First, if legitimacy is analyzed empirically, the empirical investigation has to take into account both the (more abstract) expectations of the population regarding a political system's qualities as well as the (more concrete) evaluations of the realizations of these expectations. But it is always the sovereign people, and only the sovereign people, that decides what is worthy to be recognized, and what is then measured by the researchers. If the sovereign's expectations match its evaluation of the system, the system can be deemed legitimate. This approach has the advantage that it is enough to measure citizens' beliefs. Such an understanding of legitimacy is hence subjective, and it is internal in the sense that the system is judged by its members. No normative-theoretical and hence no criteria for measuring legitimacy that are external to the system are needed. This allows to measure the legitimacy of a system irrespective of its regime type.

One benefit of this approach is that it also allows to understand why certain historical types of political systems can be judged legitimate (Beetham, 1991). For instance, two out of Weber's three types of legitimate rule (Weber, 1972, p. 19), traditional and charismatic rule, are based on such a congruency of legitimacy beliefs and legitimacy claims. But, as underlined above, the decisive problem of this approach is that also as long as it is deemed subjectively legitimate by the sovereign modern, a non-democratic systems can pass the hurdle to legitimacy–and, as mentioned above, most non-democratic regimes will rely (more or less strongly) on oppressive and/or unlawful mechanisms, even if citizen support may be high.

Therefore, it is indispensable to also include external, i.e., normative-theoretical standards that are not immediately related to citizens' beliefs into the analysis. The legitimacy of a political system on this basis can be judged externally, i.e., as according to normative-theoretical standards. They can be based on the well-founded and well-argued canon of criteria for legitimate systems. These include the rule of law and hence a balance of powers between legislative, executive and judicial institutions as well as an established set of laws and civil and political rights that are legally and politically enacted and controlled, i.e., political rights, freedom rights and minority protection (Kneip and Merkel, 2017, 2020). An external, normative-theoretical judgement should also include the citizen's expressed consent to the ruler or government. This would usually involve free and fair elections. A regime that is not based on the rule of law and citizen consent will rely (more or less strongly) on oppressive and/or unlawful mechanisms, for which, in our view, no satisfactory normative external justification can be found (see in detail Kneip and Merkel, 2020).

But we still may face the problem that the externally defined normative-theoretical standards do not necessarily match the internal expectations of the population. At this point of the conceptualization we are confronted with a dilemma. Either we accept that practically any kind of political system can be legitimate as long as the population believes it to be legitimate, or we are confronted with the criticism to apply criteria that are externally defined and hence possibly are deemed inappropriate to the particular political system in question, for instance because they are based on Western traditions of democratic thought.

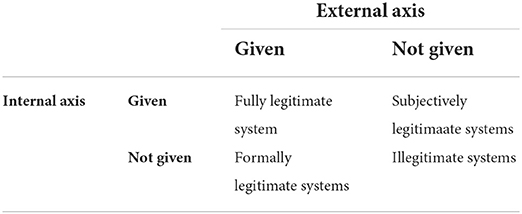

To do justice to this dilemma and to integrate subjective/internal and empirical as well as external, normative-theoretical dimensions into the operative conceptualization of legitimacy, a solution consists in conceptualizing legitimacy beyond an either-or of solely empirical or normative-theoretical dimensions, but to allow for variety. We therefore suggest to structure the concept of legitimacy alongside two axes (see in detail Wiesner and Harfst, 2019b, p. 28). The first axis represents the subjective dimension of legitimacy, i.e., a population's beliefs (internal legitimacy). The second axis expresses the normative-theoretical standards for legitimacy (external legitimacy) (Table 1).

On the first axis, a system is to be classified as being internally legitimate if the population judges it to be legitimate as according to the criteria defined by the population itself. Accordingly, authoritarian systems that rely on sufficient recognition by their population would appear as internally, i.e., subjectively legitimate. Given their scores in citizen support, regimes such as contemporary Russia or China could be classified as subjectively legitimate. In order to include the normative-theoretical character of legitimacy as well, the second axis of legitimacy analysis uses external criteria. On this axis, the respective political system is evaluated according to well-founded normative-theoretical standards. These standards, then, must represent a minimum consensus that can be guaranteed by a reasonable number of states. A definition of democracy such as the one by Diamond und Morlino offers a potential minimum consensus3:

“At a minimum, democracy requires: (1) universal, adult suffrage; (2) recurring, free, competitive, and fair elections; (3) more than one serious political party; and (4) alternative sources of information” (Diamond and Morlino, 2004, p. 21).

This canon also represents a possible answer to question (2)—What are the good criteria and items for measuring or analyzing legitimacy?

If we thus combine internal and external measures of legitimacy, we arrive at four different subtypes. First, there are systems that are neither internally nor externally legitimate, and hence illegitimate. An autocracy that oppresses its population, maybe even violently, would fall into this category–contemporary Syria could be an example. Second, there are systems that are both internally and externally fully legitimate. This would be the case for most fully developed democratic regimes that rank both highly in democracy rankings and enjoy high levels of congruence between citizens and governments empirically. In addition, there are two hybrid types: a system that is deemed legitimate internally by its citizens, but does not dispose of sufficient external legitimacy, possesses subjective legitimacy. As said above, Russia and China could be classified thus. Finally, a system that is to be deemed legitimate as according to the external normative standards, but does not possess the internal legitimacy of the population, is marked by formal legitimacy. This would go for any system that is in decisive lack of congruence between citizen beliefs and the government. As the debate on democratic deconsolidation underlines, a number of developed democracies currently are at least in danger of falling into this category (see the debate by Alexander and Welzel, 2017; Foa and Munck, 2017a,b; Norris, 2017).

The classification developed above obviously consists of ideal types, and there are—as in every typology—several degrees and shades of political legitimacy to be imagined that will fall in between the ideal types of this typology. This is why it is useful to speak of axes of legitimacy: the approach presented in the table also enables us to include degrees of both the internal and the external criteria into the analysis. It means that the more a system shifts from internal legitimacy to internal illegitimacy, it risks to collapse. This is a part answer to question (6)—Which degree of legitimacy loss is critical for a political system's survival?

Furthermore, regarding our external criteria there may be cases in which it is useful to apply only minimalistic external criteria for formal legitimacy. In a study on an autocratic regime, for instance, the introduction of free and fair elections might be considered a decisive step. In other cases, however, those minimalistic criteria will not be adequate for measuring changes of legitimacy: in a study on a country such as Sweden, gradual changes in dimensions such as freedom of the press or minority rights will be much more decisive.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we think to have opened a useful avenue for both reconciling normative-theoretical and analytical dimensions in legitimacy research and for analyzing shades and degrees of legitimacy.

The discussion has shown, first, that it is useful to establish genealogies of contested concepts in order to get to grips with crucial questions of their conceptualization and operationalisation. The Social Sciences could benefit from a more frequent and more sophisticated application of this methodological tool that is borrowed from intellectual and conceptual history. Second, the discussion also has established that and why any conceptualization of legitimacy must integrate normative-theoretical as well as empirical dimensions.

Third, and most importantly, the proposal for integrating both these approaches that was presented above is a means and a pathway to not only integrate these approaches in analytical research, but also to give both their specific credit. The fourfold matrix that comes out of it, in addition to all this, is a more fine-grained tool of classification than a binary model of separating legitimate and illegitimate systems only. As it combines both empirical and normative-theoretical perspectives, it allows to describe the specific different patterns and subtypes of legitimacy that range from illegitimate over subjectively and externally legitimate systems and fully legitimate systems. We argue that this is a convincing and promising path for further research on legitimacy.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^By way of example and illustration, we mention the debate in manegemnt studies on institutions, their organizational structures and their stability [see the classic conribution by DiMaggio and Powell (1983)].

2. ^“Members of the Seminar were: Samuel H. Beer and Harry Eckstein, Harvard University; George I. Blanksten and Roy Macridis (Chairman), Northwestern University; Karl W. Deutsch, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Kenneth W. Thompson, University of Chicago, and Robert E. Ward, University of Michigan; Richard Cox of the University of Chicago acted as rapporteur. Several other persons participated in some of the meetings, but responsibility for the Report is assumed by the authors and members of the Seminar” (Macridis and Cox, 1953, p. 641).

3. ^We are well aware that this is a minimum definition of democracy and that there are much more comprehensive ones - but the aim here is not to analyse the quality of democracy, but to give an indication of minimum standards for legitimate systems.

References

Alexander, A., and Welzel, C. (2017). The Myth of Deconsolidation: Rising Liberalism and the Populist Reaction Web Exchange. Available online at: https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/sites/default/files/media/Journal%20of%20Democracy%20Web%20Exchange%20-%20Alexander%20and%20Welzel.pdf (accessed November 13, 2018).

Barker, R. S. (2001). Legitimating Identities: The Self-Presentation of Rulers and Subjects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beetham, D. (1991). The Legitimation of Power. (Issues in Political Theory). Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press International.

Denitch, B. D. (1979). “Legitimacy and the Social Order”, in Legitimation of Regimes: International Framework for Analysis. (Sage studies in international sociology, 17), eds B. D. Denitch (London: Sage Publications), 5–22.

Diamond, L. J., and Morlino, L. (2004). An overview. J. Democracy 15, 20–31. doi: 10.1353/jod.2004.0060

DiMaggio, P. J., and Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 48, 147. doi: 10.2307/2095101

Easton, D. (1953). The Political System. An Inquiry into the State of Political Science. New York, NY: Knopf.

Easton, D. (1975). A re-assessment of the concept of political support. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 5, 435–457. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400008309

Ferrin, M., and Kriesi, H. (2016). How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. (Comparative Politics). Corby: Oxford University Press.

Foa, R., and Munck, Y. (2017a). The End of the Consolidation Paradigm. Available online at: https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/sites/default/files/media/Journal%20of%20Democracy%20Web%20Exchange%20-%20Foa%20and%20Mounk%20reply−2_0.pdf (accessed November 13, 2018).

Foa, R., and Munck, Y. (2017b). The signs of deconsolidation. J. Democracy 28, 5–15. doi: 10.1353/jod.2017.0000

Gallie, W. B. (1955). Essentially contested concepts. Proc. Aristot. Soc. 56, 167–198. doi: 10.1093/aristotelian/56.1.167

Habermas, J. (1976). “Legitimationsprobleme im modernen Staat”, in Legitimationsprobleme politischer systeme: Tagung der Deutschen Vereinigung für Politische Wissenschaft in Duisburg, Herbst, 1975. (Politische Vierteljahresschrift: Sonderheft, 7, 1976), eds P. Kielmansegg (Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag), 39–60.

Habermas, J. (1984). “What does a legitimation crisis mean today? Legitimation problems in late capitalism”, in Legitimacy and the State, eds W. E. Connolly (New York, NY: New York Univ. Press), 134–155.

Kaase, M. (1985). Systemakzeptanz in den westlichen Demokratien, Zeitschrift für Politik (Sonderheft), 99–125.

Kneip, S., and Merkel, W. (2020). “Demokratische Legitimität: Ein theoretisches Konzept in empirisch-analytischer Absicht”, in Legitimitätsprobleme: Zur Lage der Demokratie in Deutschland, eds S. Kneip, W, Merkel, and B. Wessels (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 25–55.

Kriesi, H. (2013). Democratic legitimacy: Is there a legitimacy crisis in contemporary politics? PVS Politische Vierteljahresschrift 54, 609–638. doi: 10.5771/0032-3470-2013-4-609

Linde, J., and Ekmann, J. (2003). Satisfaction with democracy: a note on a frequently usedindicator in comparative politics. Eur. J. Political Res. 42, 391–408. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00089

Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some social requisites of democracy: economic development and political legitimacy. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 53, 69–105. doi: 10.2307/1951731

Macridis, R., and Cox, R. (1953). Seminar report. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 47, 641–657. doi: 10.2307/1952898

Norris, P. (1999). Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

Norris, P. (2017). Is western democracy backsliding? diagnosing the risks. Web exchange. SSRN Electr. J. 5, 1972. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2933655

Schaar, J. H. (1984). “Legitimacy in the modern State”, in Legitimacy and the State, eds W. E. Connolly (New York, NY: New York Univ. Press), 104–133.

Scharpf, F. W. (1999). Regieren in Europa: Effektiv und demokratisch? (Schriften des Max-Planck Instituts für Gesellschaftsforschung). Frankfurt: Campus.

Schmidt, V. A. (2013). Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union revisited: input, output and throughput. Polit. Stud. 61, 2–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00962.x

Skinner, Q. (2009). A genealogy of the modern state: British academy lectures. Proc. Brit. Acad. 162, 325–370. doi: 10.5871/bacad/9780197264584.003.0011

Urbinati, N. (2006). Representative democracy. Principles and genealogy. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

Weber, M. (1972). Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft: Band I/22,1-5 + I/23: Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Jubiläumspaket. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Wiesner, C. (2020). “Introduction: rethinking politicisation in politics, sociology and international relations”, in Rethinking Politicsation in Politics, Sociology and International Relations, eds C. Wiesner (Palgrave Macmillan), 1–15.

Wiesner, C., Björk, A., Kivistö, H. M., and Mäkinen, K., (eds.). (2018). “Shaping Citizenship as a Political concept,” in SHAPING CITIZENSHIP: A Political Concept in Theory Debate, and Practice [S.l.] (Routledge), 1–16.

Wiesner, C., and Harfst, P., (eds.). (2019a). Legitimität und Legitimation: Vergleichende Perspektiven. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Keywords: legitimacy, concepts, genealogy, normative-theoretical, empirical-analytical, methods, quantitative, theory

Citation: Wiesner C and Harfst P (2022) Conceptualizing legitimacy: What to learn from the controversies related to an “essentially contested concept”. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:867756. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.867756

Received: 01 February 2022; Accepted: 30 September 2022;

Published: 28 October 2022.

Edited by:

Egle Gusciute, University College Dublin, IrelandReviewed by:

Martijn Christian Vlaskamp, Institut Barcelona d'Estudis Internacionals, SpainMarcelo Bucheli, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United States

Copyright © 2022 Wiesner and Harfst. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Claudia Wiesner, Y2xhdWRpYS53aWVzbmVyQHNrLmhzLWZ1bGRhLmRl

Claudia Wiesner

Claudia Wiesner Philipp Harfst

Philipp Harfst