- Centro de Estudios Arqueológicos, El Colegio de Michoacán, La Piedad, Mexico

Cross-cultural research on ancient societies demonstrates that collective social formations tend to experience a more sudden collapse with relatively catastrophic effects compared to formations low in collectivity. The demise of collective formations often involves more pronounced social unrest and a more complete disintegration of the agrarian and sociopolitical systems. This article further probes this general finding using the case of Teuchitlán, in the Tequila region of Jalisco, Mexico, which lasted for ~700 years, from 350 B.C.E. to about 450/500C.E., when it suddenly disappeared. It was characterized by power-sharing among multiple groups whose leaders employed varied political strategies. Structurally, Teuchitlán aligns with some of the precepts of collective action and good government, as it was inwardly focused and placed great emphasis on the joint production of the polity's resources, especially agriculture, as well as the equitable distribution of benefits, such as community feasting and ritual, and some form of political participation or voice (e.g., power-sharing). Scholars working in the area have invoked various environmental factors, demographic movements, natural disasters, the collapse of central places, and a breakdown in trade connections, among others, as causes of Teuchitlán's disintegration—and the answer may indeed lie in a combination of these phenomena. This article explores the major shifts in the institutions that comprised Teuchitlán, thereby presenting an alternative view of its nature and disappearance. Settlement patterns, architectural differences, ceramic decoration and vessel forms, and lithic technology from the period following Teuchitlán's collapse suggest major changes in ideology, economy, and politics. The placement of large centers along trade routes, coupled with increased control of interregional exchange, indicates a shift toward direct, discretionary control of polity revenues by political leaders with little benefit for the populace. As part of these changes, the human landscape became more ruralized. Teuchitlán is comparable to other well-known cases in the world where more collective forms of political organization met a similar fate, such as Chaco Canyon (Southwest USA), Jenne-jeno (Mali), and the Indus Civilization.

Introduction

Archaeology's view of the evolution of complex ancient societies is still heavily engrained in ideas stemming from Marx's Asiatic mode of production (Lull and Micó, 2011; Rosenswig and Cunningham, 2017; see also Blanton and Fargher, 2008, pp. 6–10), an approach which assumed that all non-Western societies are led under the authority of (sometimes) ruthless rulers who naturally acquired goods and services from the subaltern population free of any questioning. This theory presumes the existence of a political structure in which 90% of the population was ignored, instead focused on the actions and material remains of the few; that is, those who wielded power to control the people and an area's natural and ideological resources, with no limits on the scope of their rule and authority. Their almost supernatural powers influenced the forces of nature and allowed them to legitimize their positions of power and status. Furthermore, the origins of complexity (e.g., states) were interpreted as the result of the genius and “true” consciousness of those few, as opposed to the false consciousness of the masses. Archaeological research guided by these assumptions thus concerned a select group of people (elites, leaders, rulers, kings), their accomplishments and failures, and their lives and deaths. Anthropological archaeologists are correcting this myopic view of the evolution and nature of ancient societies by focusing on the interplay between leadership groups (perhaps 10% of the population) and the rest of the people. They now place greater consideration on people's agency and their role in the organization and structure of societies (Dobres and Robb, 2000; DeMarrais and Earle, 2017, p. 184), sustaining that elites are not self-made.

Fortunately, significant advances in theory (Blanton et al., 1996; Blanton and Fargher, 2008, 2016; Carballo, 2013; Fargher and Heredia Espinoza, 2016; Feinman, 2018), have moved away from the quest to find the rich and famous in all complex formations, and instead focus on the multiple avenues that lead toward complexity. Commoners now are more visible and are the focus of discussion as political, economic, and ideological actors. Thus, overwhelming amounts of archaeological evidence for a diverse array of ancient sociopolitical formations, however, can no longer be ignored, and any attempt to explain complexity with a “one-size-fits-all” model will be flawed. Numerous societies do not conform to the Asiatic mode of production (Blanton and Fargher, 2008; Fargher et al., 2010, 2011a; Carballo, 2013; Fargher and Heredia Espinoza, 2016; Heredia Espinoza, 2020, 2021), and new theoretical developments in anthropological archaeology are illuminating a fuller spectrum of our ancient heritage.

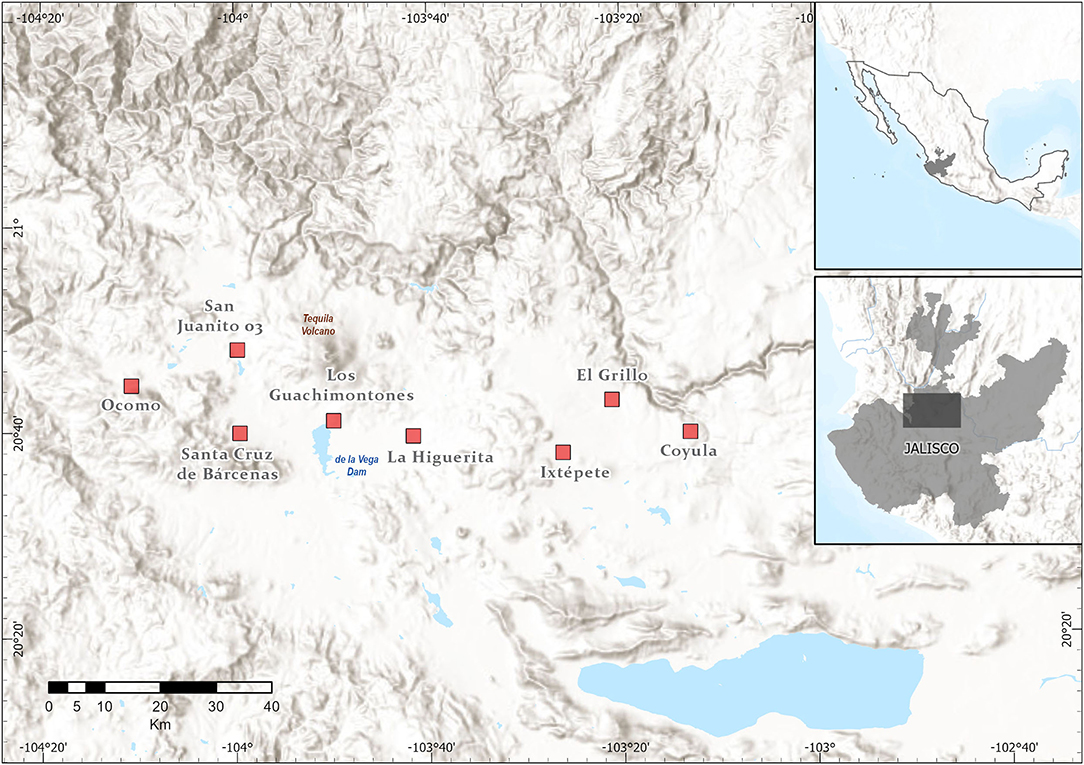

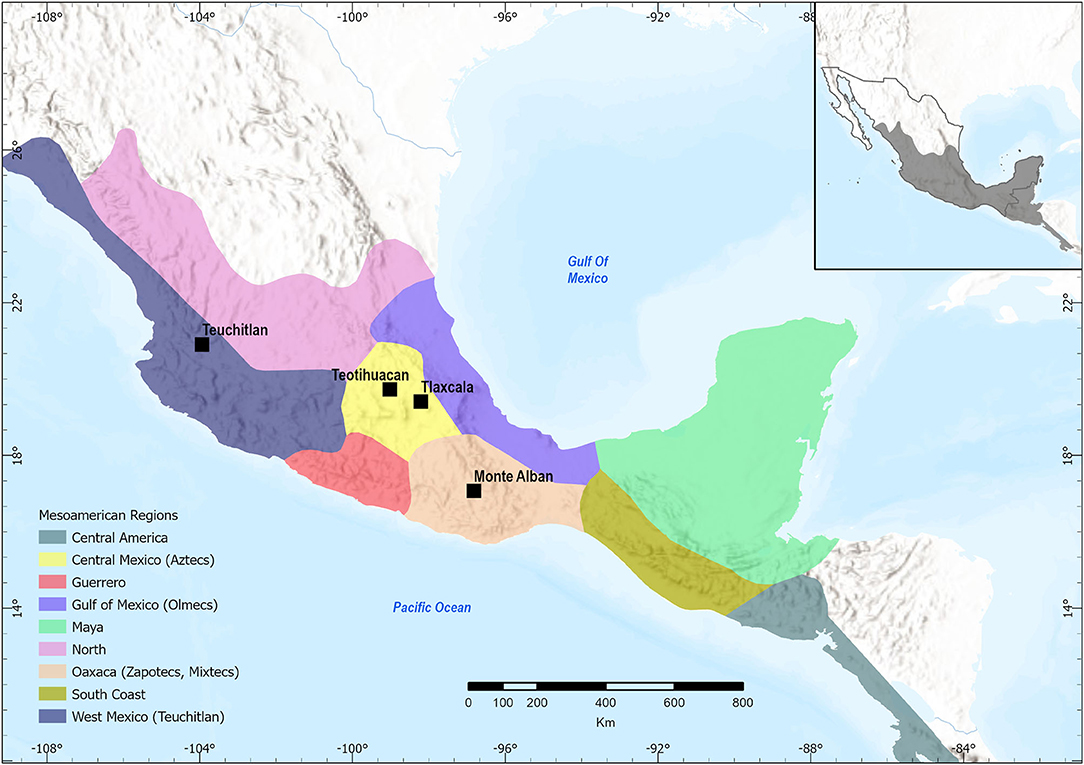

In Mesoamerica (Figure 1), Teotihuacan and Tlaxacallan in central Mexico (Fargher et al., 2011b; Manzanilla, 2015; Carballo, 2020), Monte Albán in Oaxaca (Joyce et al., 2001; Fargher, 2016; Feinman et al., 2021), the Gulf region (Stark, 2016), and the western reaches of this area (Heredia Espinoza, 2016, 2020, 2021; Beekman, 2020), all offer cases that defy deeply-held notions of past sociopolitical structure. This article describes Teuchitlán in the Tequila region of Jalisco, Mexico (350 B.C.E.−450 C.E.), a singular cultural phenomenon that was large in scale (its core developed region covered roughly 2,500 km2), had a population of at least 20,000, was urbanized, relied on intensive agricultural practices, and specialized craft production, and displayed outstanding architecture (Weigand, 1996; Heredia Espinoza, 2017). Yet Teuchitlán was so distinctive that it cannot be described as similar to any other Mesoamerican state. In fact, Teuchitlán aligns with some of the precepts of collective action and good government, including power-sharing among multiple groups, the presence of public goods and a public voice, all manifested in public spaces, cooperation, and reciprocity (Beekman, 2008; Heredia Espinoza, 2020, 2021). But Teuchitlán disappeared suddenly around 450 C.E., giving way to smaller, wholly new, and non-Teuchitlán-like material cultures and institutions.

Figure 1. Regions and places in Mesoamerica mentioned in the text (map modified from Solanes Carraro and Vela Ramírez, 2000:16).

Blanton et al. (2020) suggest that collective societies tend to experience more sudden collapses with relatively catastrophic effects than formations characterized by low collectivity. These effects include more pronounced social unrest and a more complete disintegration of the agrarian and sociopolitical systems. The moral collapse of state authorities (i.e., the failure to honor their commitments to the people, thus undermining confidence in political leaders and institutions) is cited as the primary cause of such disruptions. These conclusions are based on a previous article by Blanton (2010) in which, setting out from resilience theory, he explored “the degree to which the dynamic properties of adaptive cycles reflect, in part, the influence of political factors associated with collective action in state formation” (p. 41). In ecology, “ecological transformations result when ecosystems collapse and then are reorganized through a process they call adaptive cycles” (Blanton, 2010, p. 41). Using a cross-cultural study of premodern state formation in 30 societies, Blanton sought to apply resilience theory to sociopolitical transformation. The results revealed that collective action as a political process impacts cross-cultural variation in the properties of adaptive cycles. The results of his analysis indicate that collective societies crash harder or collapse more drastically due to hypercoherence or overconnectedness because they require “an increase in the centralized control of flows of information and materials across the social system as a whole” (Blanton, 2010 p. 44). Findings also indicated that collective societies tend to last longer than societies that are low in collectivity.

Adopting the primary premise that collective societies collapse in a more turbulent manner proposed by Blanton et al. (2020), I explore the Teuchitlán debacle of circa 450 C.E. Briefly, local and regional changes in administrative hierarchies, in the distribution and size of rural and urban settlements,1 in the relative scale of civic-ceremonial architecture, and in productive infrastructure (e.g., agricultural terraces, raised fields, etc.) lead me to argue that people shifted from a more collective formation to one more individual-centered or authoritarian.

Setting the Stage for the Tequila Region

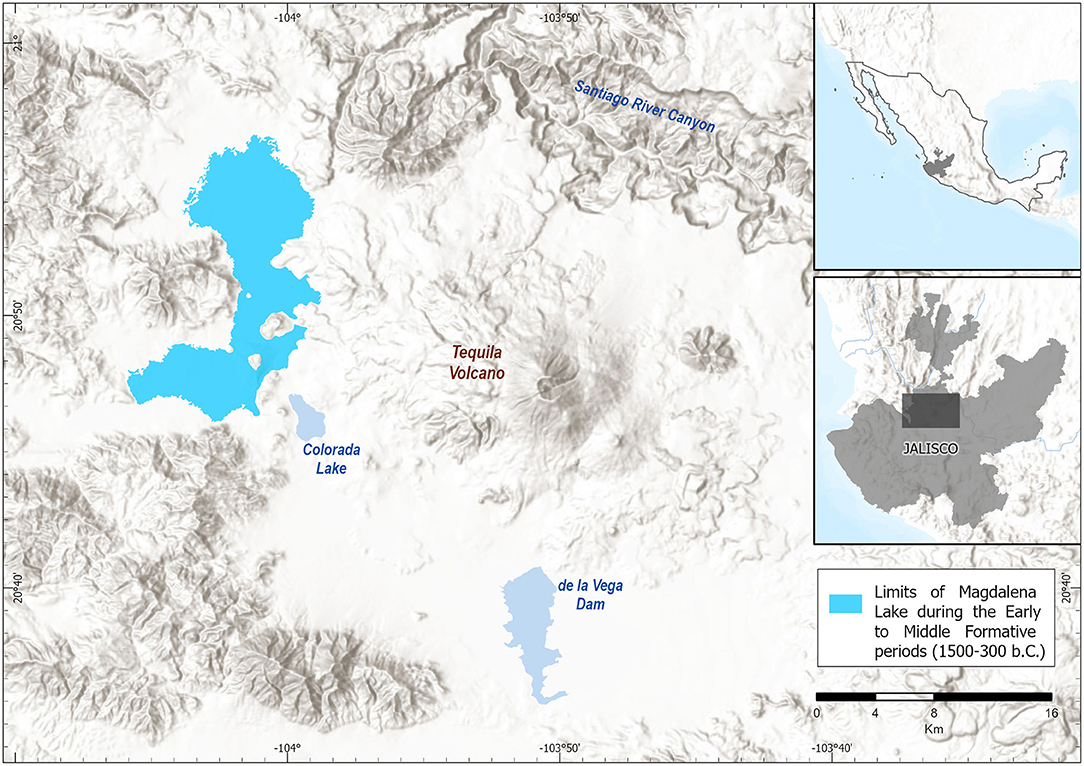

For most readers, ancient Mexico was the land of the Aztecs, Maya, and, perhaps, Olmecs, Zapotecs, and Mixtecs (Figure 1). The area around Tequila, in contrast, conjures up images of a famous alcoholic beverage, for the indigenous culture that evolved in this region is not so well-known. What we call Teuchitlán society was centered in the Tequila region (Figure 2). Its material trademarks, which turn up repeatedly as a set in the architectural record, are shaft tombs, patio groups, ballcourts, and circular platform complexes called guachimontones (Figure 3). There is evidence of intensive agricultural practices (e.g., terracing and raised fields) and craft specialization (e.g., obsidian) from excavations and surveys, both older and more recent. To date we have surveyed thousands of square kilometers in search of ancient sites (Weigand, 1996; Anderson et al., 2013; Heredia Espinoza, 2017).

Figure 3. Aerial view of guachimontones and a ballcourt (a) at the Los Guachimontones site (photograph courtesy of Sebastian Albachens). Landscape view of Los Guachimontones' main civic ceremonial area (b) looking south toward the de La Vega dam (photograph courtesy of Lic. María Ramírez Ramírez and Dra. Estefanía Hurtado Llanes @DroneTuVuelasYoVoy 01.11.2020).

Teuchitlán and Its Institutions

Political Institutions

The political structure from 350 B.C.E. to about C.E. 450 is the most widely discussed and debated topic in the Tequila region (Weigand, 2007; Beekman, 2008; Heredia Espinoza, 2017). Specifically, discussions have dwelled on whether it represented a state or some other type of political formation, perhaps a chiefdom. Debate has raged for years: what type of polity2 was Teuchitlán?; did a state develop there?; was it an endogenous development or did it emerge through interaction with other “more developed” areas in Mesoamerica?; or did the people in this region live in a longstanding chiefdom condition (Mountjoy, 1998; López Mestas and Montejano, 2003; López Mestas, 2011) where powerful chiefs/leaders governed by birthright and through their prowess in manipulating ideology and supernatural forces?

Weigand (2007) recognized the eccentricity of the archaeological remains from this region and suggested that Teuchitlán could be understood as a segmentary state. Southall (1988, p. 52) defines this kind of state “as one in which the spheres of ritual suzerainty and political sovereignty do not coincide. The former extends widely toward a flexible, changing periphery. The latter is confined to the central, core domain.” In a segmentary state, the core of the political structure is tightly unified as a single political entity, while political authority dissolves in the periphery, though ideological suzerainty is maintained. These political structures are marked by fluid political and ideological boundaries where factional competition and political instability prevail. In Southall's model, however, the term “state” is misleading since these are not like the states we know from archaeology, which exhibit at least three levels of administrative hierarchy (Wright and Johnson, 1975). The segmentary state model is also inadequate for explaining the archaeological evidence from Teuchitlán because segmentary states tend to be low on collectivity and align best with autocratic governments (Fargher and Blanton, 2012; Heredia Espinoza, 2020). Teuchitlán, in contrast, exhibits notable collective and cooperative features that are difficult to fit into this political structure.

More recent work has attempted to avoid the typological trap. Beekman considers multiple fields (built spaces) where political leaders employed varying political strategies (some more individualized, others more group oriented) to attain distinct goals (Beekman, 2016a, 2020). He proposes that multiple lineages shared power and ruled over the several polities in the region. Based on evidence of sequential interments and genetic relatedness of the deceased in shaft tombs (López Mestas and Ramos, 2000), Beekman (2008) infers the presence of lineages. Tombs often contain thousands of luxury objects from distant places, and they also differ in size and form (Beekman, 2016b; Mountjoy and Rhodes, 2018). The deepest ones consist of a vertical shaft that links to one or more burial chambers (Ramos de la Vega and López Mestas, 1996; Beekman, 2016b, p. 85). Unfortunately, these tombs are highly-coveted by looters, so the largest and—possibly—richest ones have been vandalized. The location of tombs varies as well since some are isolated, but others are associated with architectural features (Beekman, 2016b). The widespread destruction of these contexts impedes our understanding, for only one intact tomb has been excavated to date, located in what appears to be a private residence adjacent to public architecture (Ramos de la Vega and López Mestas, 1996). At Los Guachimontones, the largest and most complex Teuchitlán site,3 a modest (in size and offerings) shaft tomb was located underneath public architecture. It included multiple individuals placed in the cardinal directions. Other elaborate (alas, also looted) shaft tombs are known to be located underneath mounds (Beekman, 2016b).

While the sample of scientifically excavated shaft tombs is meager, the single intact, rich excavated shaft tomb at Huitzilapa indicates that the individuals interred there were related by kinship (Ramos de la Vega and López Mestas, 1996). Based on osteological analysis, five of the six individuals revealed a congenial hereditary malformation known as Klippel-Feil (López Mestas and Ramos, 2000, p. 62). Archaeologists in the area interpret these data as indicative of ruling lineages. In addition to these tombs, the governing groups are visible in a distinct style of architecture that is more group oriented than individual.

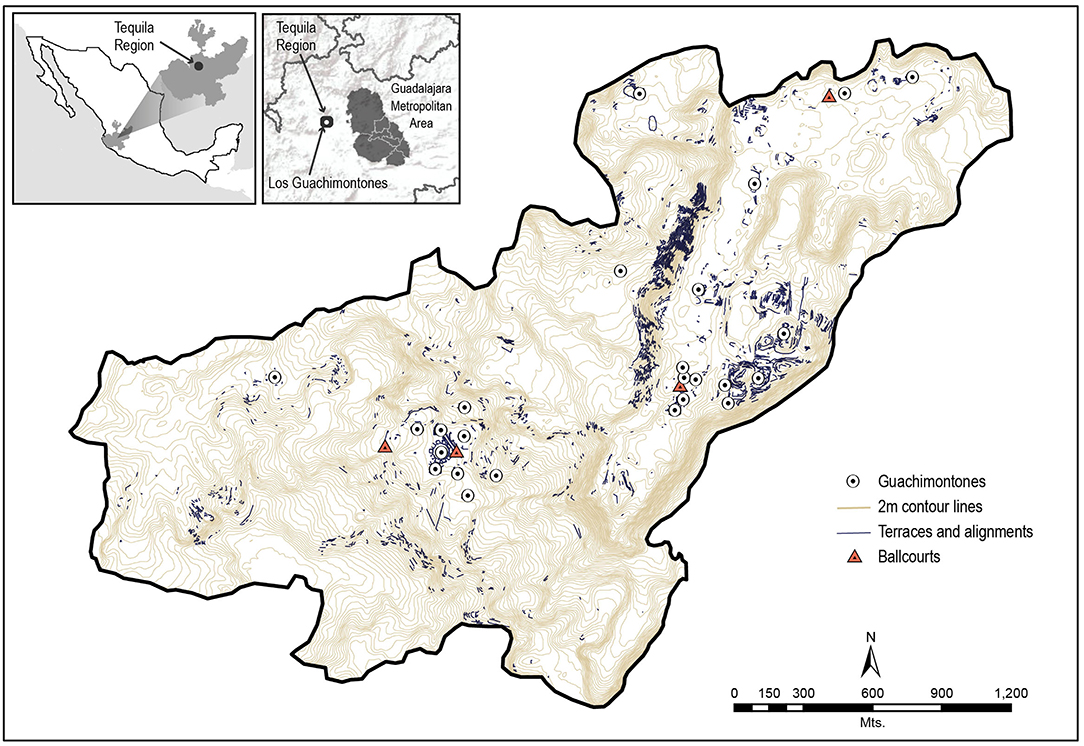

The guachimontones, the most pervasive architectural form, suggest that collective rather than autocratic politics prevailed. These are circular architectural complexes comprised of a central temple or altar and a circular patio with a series of rectangular, usually even-numbered, platforms, 4, 6, 8,10, or 12, around them that form several concentric circles (Figure 3). Our current understanding is that each platform around a circle was occupied (temporarily) by a power-sharing group that sponsored and conducted festivities. The circles represent cooperation both individual and collective in nature as they are a form of public architecture built by different sources of labor. Analysis of construction methods and labor investments point to both crews and communal labor at a single guachimontón (Weigand, 2007; Beekman, 2008; DeLuca, 2019). Excavations on the platforms show differences in the construction skills required to build them and the quality of the raw materials used. Numerous ceramic models show each platform with subtle differences in roof decoration (von Winning, 1996). The size of individual buildings, however, is restricted by the overall shape of the circular complex itself (Beekman, 2008), hindering any overt dominance of one over the rest that is suggestive of commensurable power and authority among constituent groups. The construction techniques and materials of the central patios and altars suggest collaborative building (DeLuca, 2019). Interpretations thus posit that the guachimontón symbolically and materially represents a political institution that consists of several social groups which shared power and collaborated in decision-making.

The guachimontón complexes were not exclusive to one group of individuals (e.g., leaders) but were meeting places for a broader set of people. Spatial analyses of several circles indicate that they had fairly open access and, hence, were accessible to the average person (Sumano Ortega and Englehardt, 2020). The guachimontón embodies the basis of a political life in which cooperation among diverse groups and individual and group effort all converged, while serving as a meeting place where people and authorities assembled. It was the location for opining and participating, one where authorities displayed their commitment to collective endeavors while simultaneously fostering trust and unity among the people (Heredia Espinoza, 2021).

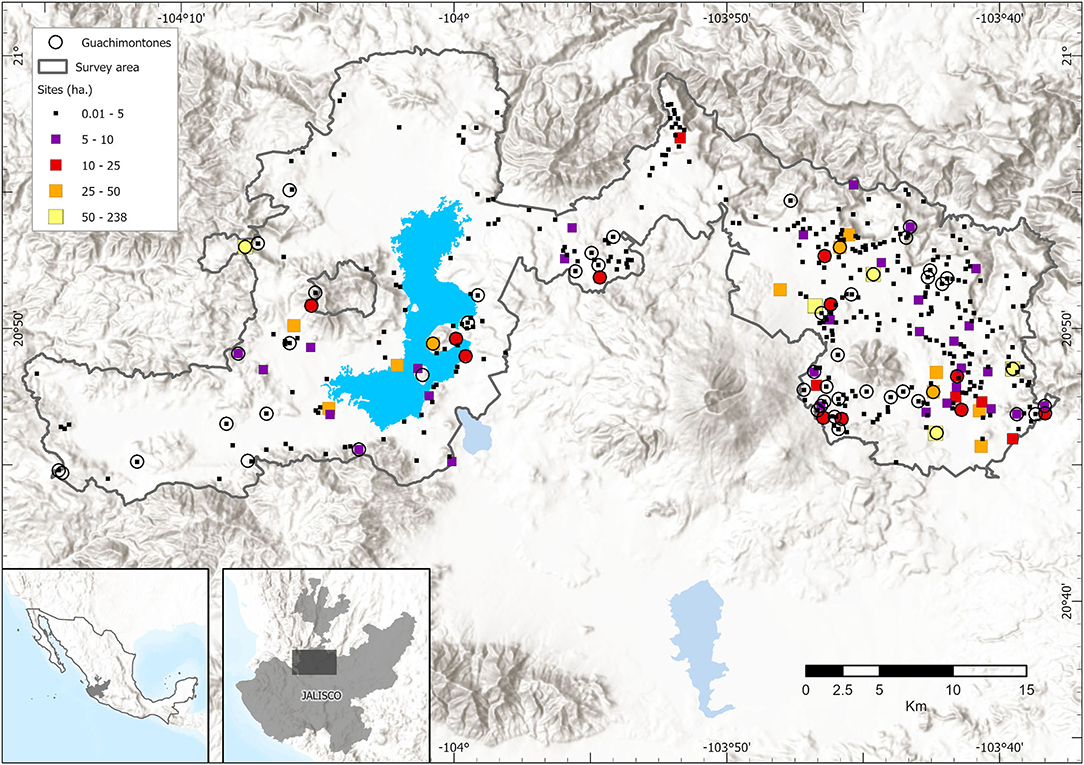

The distribution of the guachimontón architectural complexes shows that this political institution was widespread in the Tequila region. In an area surveyed systematically north and west of the Tequila volcano, 90 guachimontones were identified in 63 settlements (Figure 4), while south of the volcano there are at least 38 more settlements that contain this type of architecture (Weigand, 1985, p. 83; Ohnersorgen and Varien, 1996). There is a hierarchy of guachimontones by size (i.e., area) and by number per site (see Heredia Espinoza, 2021). Clusters of settlements, each containing a hierarchy of as many as 17 guachimontones, have also been observed. I have interpreted this pattern as a series of multiple small polities that acted both independently and semi-independently in economic, ideological, and political matters (Heredia Espinoza, 2017; see also López Mestas, 2011).

While this circular architecture is widespread around Tequila, it is not the only type of public architecture where political and social institutions intersected. Ballcourts were a prominent feature of the Mesoamerican built environment for millennia (Hill and Clark, 2001) and are ubiquitous in the Tequila region as well (Figure 3), even being portrayed in ceramic models. Interpretations as to their function and meaning range from political to sportive (Blanco Morales, 2009; Beekman and Heredia Espinoza, 2017). It is not completely clear who used them or for what specific purposes, yet their location within settlements indicates that they had public functions in which the community participated and promoted festivities. They may also have played a role in each of these settlement clusters as places for social negotiation and identity (following Fox et al., 1996; Beekman and Heredia Espinoza, 2017).

Figures of West Mexican ballplayers and ceramic models display distinctive paraphernalia (Day et al., 1996; Butterwick, 2004, p. 17; Oliveros Morales, 2013). It is possible that they were members of a particular group with a set of duties (i.e., an institution, following Holland-Lulewicz et al., 2020). Elaborate shaft tomb offerings sometimes include figures of ballplayers that may allude to the deceased's connection to, or participation in, ballgames (Ramos de la Vega and López Mestas, 1996). In other places in Mesoamerica, ballplayers belonged to a privileged group that played to acquire wealth and status (Hill and Clark, 2001). Thus, the ballcourts around Tequila may have constituted an institution in which the political and religious realms intersected. But the game also acted as a social lubricant and vehicle through which people, or entire communities, regulated internal competition (Fox et al., 1996; Hill and Clark, 2001). The ceramic assemblages from two ballcourts excavated at Los Guachimontones revealed a high frequency of coarse, closed ceramics (e.g., jars) rather than open (e.g., bowls), decorated, finely-made pottery, pointing to integrative public events rather than competitive status competition activities (Beekman, 2020, p. 86). Researchers have devised a series of archaeological correlates related to types of feasting events and ceramic forms and decoration. Briefly, open, decorated, fine pottery is associated with food serving at events geared toward status distinctions and competitiveness (but see Mills, 2007, for an example of the use of decorated pottery supra-household commensalism) whereas coarse and/or plain serving vessels, along with large, but small-mouthed, vessels for cooking large amounts of food are associated with integrative events that involved transport, supply, and food preparation assemblages (Hayden, 2001).

To summarize, circular guachimontón complexes and ballcourts were prominent public architectural features of the built environment in Tequila. Broadly speaking, tombs and private residences are generally modest in comparison, highlighting the importance of the public over the private sphere. The prevalent political institution of Teuchitlán at the regional level can thus best be conceived as some sort of alliance among several corporate groups4 that shared power. This political institution was closely related to religion as well.

Religious Institutions

Ritual architecture –that is, “temples”– is another integral feature of these circular complexes. The central altar, specifically, represents the earth and sky (Beekman, 2003, p. 12). The altars vary in volume and form (Ohnersorgen and Varien, 1996, Table 4), as only some are square. But the largest ones (volumetrically) served community or region-wide ceremonies in which a pole was erected in the center and a priest specialist balanced himself on his abdomen atop it. This ritual may have been related to a wind deity yet we have no indications of specific deities for this time. However, for some time Weigand (1993, p. 224) suggested a proto-Ehecatl as the supreme deity for the area, but Teuchitlán is not contemporaneous with this iconography. Depictions of these temples in ceramic models represent ceremonies performed in public spaces with popular participation, events that involved food, drink, music, and dance (Day et al., 1996; von Winning, 1996). Temples, of course, require personnel, but we have yet to learn about who those people may have been. May they have been a group of specialists dedicated to these rituals only? Did they come from specific families, and did they have specific training? The celebrations and spectacles reproduced in clay art certainly suggest that some of the participants must have had special training, knowledge, and skills. These participants would have been members of other formal and informal institutions that I describe next.

Social Institutions: Households, Intermediate Sociospatial Units, and Rural Communities

Households are groups of people who may share an identity or have kinship ties and who share a dwelling or a residential compound (Blanton, 1994, p. 5). Economically they work together in production and reproduction and can partake in decision-making in political matters (Carballo, 2011). Households are detected archaeologically by the remains of structures (e.g., houses or house foundations). Teuchitlán household arrangements took many forms: some are isolated while others constitute more formalized patio groups (Ramos de la Vega and López Mestas, 1996; Herrejón Villicaña, 2008; Smith Márquez, 2009). Patio groups consist of 3–4 structures that share a patio or open space for daily activities. Households are commonly represented in ceramic models that depict an array of activities and the presence of both genders that suggests their social composition. Groups of houses may cluster in such a way that they could constitute higher-level, more formal social institutions.

The leading scholar of Teuchitlán studies, Phil Weigand, argued that the settlements with circular architecture clustered near each other in ways that resembled neighborhoods (2010). The settlement at Los Guachimontones was subdivided into intermediate sociospatial units (neighborhoods and districts), each focused on a circular complex (Figure 5, Heredia Espinoza, 2021). These units may have functioned as nodes between government authorities and the people. Groups of households (neighborhoods, see Arnauld et al., 2012) that shared public spaces were embedded within larger districts that contained the full range of services (ritual, economic, political) (Heredia Espinoza, 2021). The residential clusters that surround public architecture indicate that services (religious and political) were widely available and easily accessible to the population. We have yet to determine whether the clustering detected at Los Guachimontones is replicated elsewhere in the area, but we can identify groups of households away from districts and neighborhoods.

Such is the nature of rural communities, which are collections of households that lack larger functions and at least some basic services (Kowalewski and Heredia Espinoza, 2020, p. 506), though they participate as entities in higher-level activities for a neighborhood or district. In the area surveyed, degrees of “ruralness” are based on measurements of the distance from residential settlements to the nearest civic-ceremonial place (e.g., guachimontones, ballcourts, plazas). A nearest neighbor analysis of sites with guachimontones did indicate such clustering (ratio: 0.681104, z-score: −4.842, p < 0.001) and an average distance among them of only 1,458 m, a distance easily walkable in about 15–25 min. Moreover, almost everyone −98% of the population– lived within a 2-h walk of a central place. This means that central services were available to almost all rural settlements from multiple centers within a walkable distance (see Anderson, 1980; Ligt de, 1990, pp. 31–32).

Economic Institutions

Among the services available to people were various basic goods such as ceramic vessels and obsidian tools, some of which presumably could be obtained through exchange systems such as markets. Archaeologists have devised ways to infer the potential and optimal physical places where markets can be located. Open markets, where people from multiple communities and social sectors meet to buy and sell (Marino et al., 2020), tend to be held in accessible spaces (Garraty, 2010, pp. 9–10; Kowalewski, 2012; e.g., formal plazas or similar open areas). They appear more frequently in cities and towns where there are more people and greater demand for goods and services (Blanton, 1976; Kowalewski, 2016). Hence, settlements that exhibit an array of other services (administrative, ritual, etc.) are more likely to offer market services as well. There are numerous examples of this phenomenon in the study region, which is relatively flat, has few natural barriers, and is easily traversed on foot (Figure 2). Formal open spaces like plazas are scarce, but open areas adjacent to civic-ceremonial and residential zones are relatively abundant (Muñiz García, 2017). While market exchange is not well-researched in this region, some data point to its presence in the Teuchitlán economy.

Archaeometric analyses of samples of ceramics and lithics provide evidence of open exchange systems and multiple production locales. Petrographic analyses (a technique employed to identify different types of rocks) of ceramics from several sites point to multiple production locales north of the Tequila volcano (Heredia Espinoza, 2019). Results of these analyses indicate that there were at least seven production locales. These locales supplied consumers in three main geographical/geological locations suggesting that, even though some ceramics moved across the region, some were distributed in a more localized clustered manner.

An additional key economic resource in the region is obsidian, which form from lava ejected from volcanoes. Over 50 obsidian sources are known in the Tequila region (Spence et al., 2002). For a time, it was proposed that obsidian mines, the production of obsidian goods, and internal and external5 exchange of those goods took place under elite supervision (Spence et al., 2002, p. 70; Esparza López, 2015), but such control or long-distance exchange of obsidian is yet to be proven. Because it is widely available, controlling obsidian acquisition would have been a costly undertaking. Broad obsidian scatters, interpreted as large-scale workshops, are more likely the result of continuous use over millennia or the residue of more intensive obsidian production from C.E. 900 to 1600, a few centuries before the arrival of Europeans. Obsidian chunks without modification and cores with cortex recovered from residential structures point to households as the main actors in the production of obsidian goods (Mireles Salcedo, 2018, p.166). Further, pXRF analyses (also known as portable X-ray fluorescence, a technique that measures elemental concentrations) of samples of obsidian artifacts from numerous sites showed that they originated from multiple mines associated with specific volcanic sources, with no indication of localized distribution (Carrión, 2019). In other words, the distribution of obsidian objects throughout the valleys derived from different sources and moved some distance, suggesting exchange mechanisms that may have resembled market exchange, which is characterized by a standardization of raw material sources across social sectors (based on household's artifact categories). In markets people can acquire diverse types of goods, regardless of their status (Hirth, 1998), and allow common people to produce for profit—not just subsistence–while also providing opportunities to adopt new economic pursuits and diversify economic activities. Again, most of the obsidian objects manufactured were used primarily for domestic tasks, and many were employed in subsistence activities like agriculture and plant-processing throughout the pre-Hispanic period (Heredia Espinoza and Mireles Salcedo, 2016; Mireles Salcedo, 2018). It is now evident that obsidian as a potential source of external funding is highly unlikely from 350 B.C.E. to 450 C.E. Agriculture, however, was an important economic endeavor relating to subsistence and an internal source of revenue6 for the polity.

In fact, the people who inhabited the Tequila region before contact with Europeans invested heavily in agriculture. Based on field surveys and interpretations of aerial photographs, Weigand argued that there were ~300 km2 of raised fields (Weigand, 2001, p. 406) throughout the region, but only a fraction of these have been corroborated in the field (Stuart, 2005, pp. 187–188). Dating these features is especially challenging because organic residues do not preserve well in these contexts. Two, out of nine, radiocarbon dates (Stuart, 2003, Table 6.1, 2005, p. 189), produced dates that fall within Teuchitlán. Based on the Oxcal report, the one date is from A.D. 200 to 380 (90.8% probability) and the other A. D. 418–577 (95.4% probability) though the latter year extends well beyond the end of Teuchitlán. There is, however, a positive correlation among the distribution of settlement clusters, soil types, hydrological resources, and agricultural productivity based on site catchment analysis (Trujillo Herrada, 2020, pp. 181–185; Weigand, 2007). Iconographic analyses of symbols depicted on fine vessels provide additional support for the importance of agriculture (López Mestas, 2005, 2007; Heredia Espinoza and Englehardt, 2015). Beekman (2003, Figure 7) has proposed that the guachimontón architectural plan may depict the cross-section of a corn cob.

In summary, the regional economy centered mostly on the production of foodstuffs and the tools necessary to produce them. These products and items were for immediate use and largely destined for circulation within the region. Hence, as I have argued elsewhere, during the study period Teuchitlán was inward-looking (Heredia Espinoza, 2017) with a focus on internal resources, especially intensive agriculture with some obsidian manufacturing, both likely carried out on a household scale. This mode of production would have been difficult for potential autocrats to appropriate. However, by the end of the fifth century, Teuchitlán's institutions had collapsed, leaving few traces behind. What came after was an entirely new set of institutions.

A Whole New World

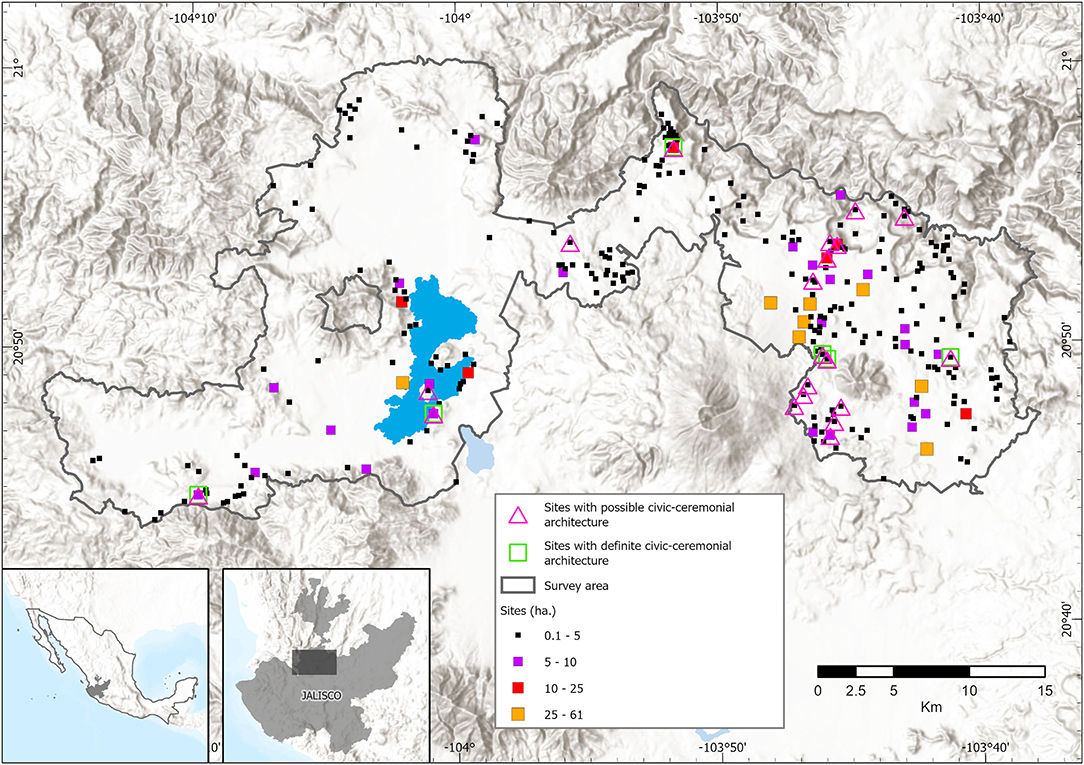

The changes ca. C.E. 450 were dramatic and definitive, as is reflected in settlement patterns, architecture, and material culture. Without doubt, they represent major shifts in the nature of the new institutions. There are no more circular complexes, ballcourts, shaft tombs, or patio groups. Whereas before, circular architecture was found at sites both large and small, after C.E. 450 there are few places with architecture beyond domestic functions (Figure 6). Indeed, the landscape appears to have become ruralized (Heredia Espinoza, 2017) as it is dotted with small villages and hamlets. The Los Guachimontones site, once the most important center, lost its prominence and was reduced to small, occupations.

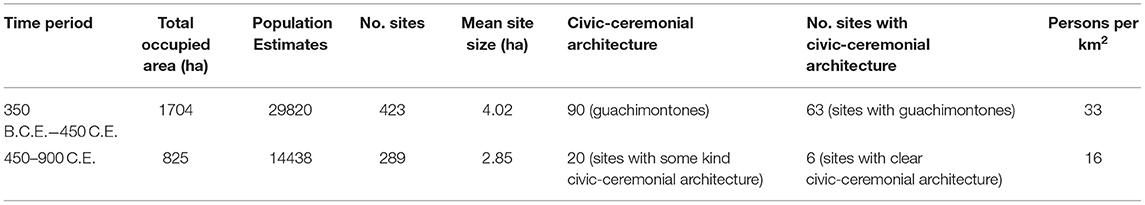

These transformations were further accentuated by a change in scale, as can be seen in the data recovered from an area covering some 900 km2. Table 1 contrasts these changes in size, occupation, and population between the two time periods. The total occupied area and population estimates both shrink to less than half compared to the previous period. Population estimates, in low ranges, were calculated in single component settlements with their residential structures and groups. Based on the smallest structures and compounds, we established minimum and maximum populations, respectively, to finally determine a range per hectare. The largest site in the earlier period extended over some 238 ha vs. only 60 ha in the ensuing period. The number of sites also decreases, and average site size falls by over a hectare. Populations plummeted 52%, from 33 to just 16 persons per km2, as did the total occupied area. The number of settlements decreased by roughly 32% and mean average site size also decreased. There was also a decrease in number of settlements with extant civic-ceremonial architecture from 15% to just 2%. If we take into consideration that in the previous time period there were 63 settlements with a total of 90 guachimontones, then 331 persons had access to at least one guachimontón. After C.E. 450 the pattern is clearly distinct. If we take the total number of sites that had public or special architecture (20), the number of people serviced by each one is 722. If, however, we consider only the six sites that had clear functions beyond the domestic sphere, that number increases to 2,406.

People from 350 B.C.E. to 450 C.E. clearly had easier access to civic-ceremonial spaces per capita; that is, the number of civic-ceremonial places was greater and more readily accessible to the average person. After C.E. 450, there were few central places, and they were more dispersed with indications of a more centralized landscape in some areas and an acephalous pattern in others. The appearance is that of a fragmented political-economic landscape with some areas better serviced than others, perhaps an open system with permeable boundaries (Heredia Espinoza, 2017). These changes are observed in both the settlement pattern and the influx of new material culture and ideas (Beekman, 2010, p. 71, 2019).

New architectural forms, such as rectangular, “L”-, and “U”-shaped structures come on stage. Sunken or enclosed patios, typical of nearby regions in Mesoamerica, also make the scene (Beekman, 1996; Weigand, 2015, p. 57). Significantly, the form of civic-ceremonial architecture changed from round to rectangular or square structures. In the surveyed area, 20 sites contain special types of architecture (e.g., L- or U-shaped structures, enclosed patios, large platforms supporting multiple structures), but only six have multiple buildings or edifices substantial in volume and scale (Figure 6). The largest two are in the southern Magdalena basin (Ocomo and San Juanito 03). They have large platforms that support multiple structures and enclosed patios (for Ocomo see Smith Márquez, 2018). The platform at Ocomo supported a large, enclosed space surrounded by several structures. Its architectural plan resembles the Mexica palaces of central Mexico a few centuries before European arrival (Weigand, 1993, pp. 147–148). Both sites extend for six hectares, taken up mostly by the platforms. The other four sites have modest architecture ranging from 270 to 1,500 m2. The question of how much authority these centers wielded in the region is still unexplored, but the settlement pattern around them is light and there are no large concentrations of people, indicative of a ruralized, deurbanized landscape (Figure 6).

Another important difference is the disappearance of ballcourts. These architectural features were presumably associated with conflict resolution, so their absence suggests several possibilities. One, perhaps fewer services of the kind they had offered earlier were required; two, methods of conflict resolution changed, or three, a reduction in the frequency of conflicts made them unnecessary. Alternatively, it is possible that conflict resolution was concentrated in the few centers with the largest architecture.

Gone as well are the shaft tombs where multiple individuals were buried, replaced by individual box tomb burial chambers as the typical type of interment (Aronson, 1993; Galván, 1993). A large platform at La Higuerita (Figure 7) yielded elaborate burials and offerings in box tombs (López Mestas and Montejano, 2003). The individuals interred there are believed to have been members of the elite whose power and authority were based on the control of exchange networks of exotic goods (López Mestas et al., 2020). It appears, moreover, that the power-sharing groups that led the political institutions embodied in the guachimontón were replaced by a more autocratic political system.

Evidently, public temples also decreased in importance, given the diminished number of civic-ceremonial centers. Sunken or enclosed patios represent one of the key architectural forms after 450 C.E. They originated in the region of the Bajío (another area within West Mexico, Figure 1). Excavated contexts suggest that they may have had both political and religious functions as some display central shrines or altars (Cárdenas García, 2008).

Changes in neighborhood composition—or the lack thereof—indicate that whatever caused these dramatic shifts penetrated deeply, right down to the household level. The guachimontón had been an organizing component of neighborhoods (Weigand, 2010; Heredia Espinoza, 2021), so its disappearance transformed the built landscape. The concentration of civic-ceremonial architecture in so few areas is suggestive of a weakening of the communication nodes (e.g., administrative places) that once connected people to government officials. Nevertheless, a nearest neighbor analysis suggests that sites show clustering (ratio 0.596, z-score: −13.145, p < 0.000). However, the average distance to civic-ceremonial places increases for most of the population.

Outside the Tequila area only a handful of central places emerge at a distance from the ancient seats of government (Figure 7). Large centers established in the southern part of the valleys and others also followed a linear path (Beekman, 2019). That was a time when information and prestige goods networks were expanding from eastern and northeastern Mesoamerica into West Mexico (Aronson, 1993, p. 358; Jiménez, 2020, Ch. 4). Hence, their establishment may be attributable to long-distance trade networks (López Mestas et al., 2020). Given the cultural transformations within and outside the region, it appears that leaders shifted to external funding to achieve their goals, controlling the flow of prestige goods.

To summarize, what we see in the Tequila region are quantitative changes in diverse institutions and a qualitative transformation of their content. The number of institutions decreased, as can be seen in the associated architecture, while the political and religious institutions that had been embodied in ballcourts and guachimontones vanished. Intermediate sociospatial units like neighborhoods also dissolved, suggesting the disappearance of connections between the common folk and higher-order political offices.

What Emerged Post-collapse?

Collapse studies, like the present one, “are important, not only because they deal with significant, though often poorly understood sociocultural phenomena, but also because they provide excellent points of entry into the social configuration of the societies that were collapsing” (Yoffee, 2005, pp. 131–132). Teuchitlán, a rather collective political structure, collapsed completely, giving way to various types of institutions that archaeologists are familiar with. Extant data suggest that after 450 C.E. the area became more autocratic as revealed by the shifts in institutions, the decrease in public goods (accessible civic-ceremonial spaces), and a likely turn toward external sources of funding. Carballo and Feinman (2016, p. 293) state that

Early cases of urbanization in Mesoamerica generally appear to have followed more collective lines, but the disintegration of these systems led to balkanized political landscapes and power vacuums which, in many cases, were initially filled by smaller kingdoms. The leaders of these smaller polities, in contrast to their predecessors, frequently drew power more from external or spot resources, coercive military practices, and interpersonal networks, expressing the trappings of nobility without returning many public goods.

This extract accurately summarizes the transformations that occurred in the Tequila region.

A likely change from internal (e.g., agricultural and craft production) to external funding (e.g., prestige goods and interregional exchange) is supported by the evidence currently available. Jiménez (2018) argues that the presence of Teotihuacan exotics—like Thin Orange ceramics and green obsidian—in West Mexico mark the spatial extent of prestige goods networks (2018, p. 82). The smaller amounts of public goods also point to a turn toward external sources of revenue and the disintegration of institutions that could potentially foster cooperation (e.g., intermediate sociospatial units, plazas, public ritual spaces). Corporate groups or families that balanced each other politically apparently gave way to fewer groups that monopolized power. It is also possible that certain factions were able to draw upon external sources of wealth and ideological support to withdraw from the moral contract with the people. In this regard, a parallel can be made with the Maya at Piedras Negras, where the authority of dynastic rulers was progressively weakened as they ceded prerogatives to non-loyal elites and were increasingly forced to shore up their authority through warfare (Houston et al., 2003).

I recognize that this article does not address the causes of the collapse of Teuchitlán society, but the data point largely to external forces, since there is no evidence of burning, large-scale destruction, termination rituals, or crisis architecture (Zuckerman, 2007) that would correlate with internal causes of collapse. However, it is important to note that more arid climatic conditions were gradually creeping into the valleys. Three radiocarbon dates from charcoal collected in stratigraphic layers interbedded with tephra in the Magdalena Lake basin (Figure 2) indicate that a volcanic eruption occurred sometime between 540 and 660 C.E. That event must have contributed partially to the social disruption and destabilization we observe in the archaeological record (Anderson et al., 2013). To date, however, we have been unable to chemically match the burst to a specific volcano. Lake sediments from the Magdalena Basin revealed a drop in the water level from 1,363 m around 350 B.C.E. to 1,361 m after 450 C.E. (Figures 4, 6). The extension of the lake was thus reduced from 53.08 to just 24.91 km2. These major changes would certainly have altered agricultural cycles and the entire array of ritual enterprise associated with them.

Similar examples to Teuchitlán and its fate are known cross-culturally. In the next section, I will briefly describe three examples from different places in the world that have historically raised controversy due to the absence of archaeological correlates that point to more individual- (or group-) centered societies. These cases come from North America (Chaco Canyon), Africa (Jenne-jeno) and Asia (Indus Valley civilization).

Comparative Discussion

Chaco Canyon, Jenne Jeno, and the Indus Valley civilization differ in many ways among themselves and with respect to Teuchitlán, but they all depart from typical forms of sociopolitical complexity since there were no palaces, disparities in wealth and prestige were narrow, public goods abounded, and power and authority were diffused, among other features that point to alternative sociopolitical formations. Their downfall was in some cases abrupt and what followed was more readily recognized archaeologically.

Chaco Canyon

Chaco Canyon in the southwestern United States has long challenged archaeologists because it does not conform to standard models of sociopolitical complexity (Renfrew, 2001; Mills, 2002). The Chaco macroregional system extended over most of the Colorado Plateau, while its core was at Chaco Canyon. Chacoan elements included widespread architectural features such as great houses and kivas, irrigation systems, road networks, high populations, and interregional integration (Gregory and Wilcox, 2007). At Chaco, there were multiple great houses, including temporary multistory residential infrastructure, great kivas (circular subterranean ceremonial structures), roads, plaza areas, and mounds (Mahoney and Kantner, 2000, p. 3; Mills, 2002, p. 68).

Great houses are multistory masonry buildings that contained hundreds of rooms (Mahoney and Kantner, 2000, p. 3). The exact function of these buildings is still controversial, even though they may seem like obvious residential constructions, the lack of clear indications for this, continues to puzzle archaeologists. There are many great houses, clustered in proximity in the canyon, and while a hierarchy is apparent, it is difficult to demonstrate that power and authority were concentrated in one single center. Great houses also include kivas, semi-subterranean, circular structures, and plazas that have yielded exotic goods, artifacts from distant places, and objects that were used in ceremonial events (Mattson, 2016). The sheer size of the great houses testifies to their importance in the region, while their repetitiveness in the San Juan Basin speaks of a shared worldview.

Despite this grandeur, no palaces have been recorded to date and evidence of ranking is fleeting at best. However, interpretations vary between researchers who see indications of a ruling elite and other authors who conclude that they were just ritual specialists (Mahoney and Kantner, 2000, p. 4). Most scholars agree that there is no evidence for autocratic governance, yet just how to properly characterize the Chacoan system is still a subject of lively debate.

Other researchers are currently investigating the degree of inequality that existed within the population of Chaco Canyon. Ellyson et al. (2019) have identified wealth inequality based on house size. Overall, they see that these differences are greater within clans than among households. Further, recent archaeogenomic work by Kennett et al. (2017) indicate that an elaborate crypt that contained several genetically related individuals provide evidence for hereditary leadership. These findings may have some implications for the political structure as it refers to degrees of inequality and its political structure.

Chaco Canyon was abandoned after the mid-twelfth century, its fall accompanied by violence and the construction of new settlements in clearly strategic, defensive locations (Ware, 2014, Ch. 6; Sedig, 2015, p. 248). New clusters of villages were established along what had been the peripheries of the Chacoan system, but many were abandoned in the following centuries, with further consolidation leading to the fifteenth-century and historically-known societies such as the Rio Grande Valley pueblos, Zuni, and Hopi. These pueblos had their own distinctive architecture and were also organized collectively with institutions such as kachina cults, plazas, and smaller kivas, but none had the singular Chacoan architecture.

Jenne-jeno

Africa seldom figures in discussions of complex societies (e.g., states and empires) or urbanism (McIntosh, 1999a; Dueppen, 2012, Ch. 1; Davies, 2013), but our conviction that complexity can come in many forms and varieties allows us to modify our view of this continent and the complexities it presents. Jenne-jeno (250 B.C. to A.D. 1400), a large city in the Middle Niger Delta in Mali, for example, features a clustered settlement pattern (i.e., urban) with a site hierarchy consisting of three tiers (McIntosh, 1999b, p. 154). At its height, Jenne Jeno reached a maximum population of 10,000 people in an area that extended over almost 33 hectares, though its urban complex and networks of physically distinct communities across a 4-km radius probably reached 50,000 souls (McIntosh and McIntosh, 2003, p. 119). Inhabitants enjoyed a high standard of living (McIntosh, 2000, p. 21). Status and ranking differences are not evident in residences or burials, and there are no clear indications of a prestige goods economy in which elites controlled highly-valued goods (McIntosh, 1999b, p. 161) as an instrument to solidify their positions and acquire wealth. The only monumental architecture identified is a wall around the perimeter of the site. This case has a distinct archaeological imprint because other monumental architecture, kings, and elites are all absent (McIntosh, 2000, p. 21).

Rather than a single, well-defined settlement, Jenne-jeno was made up of several clusters of densely-populated settlements, none of which appears to have dominated the others (McIntosh, 1999b, p. 161). The multiple clusters were not organized into a hierarchy; rather, the people of the Middle Niger Delta opted for solidarity and cooperation among multiple and diverse corporate groups that resisted centralized authority (McIntosh, 2000, pp. 21–22; McIntosh and McIntosh, 2003). The urban cluster at Jenne-jeno included various corporate groups that engaged in diverse craft specializations including iron-working, fishing, and hunting. Specialists clustered according to their craft specialization to preserve their identities. Those corporate groups created horizontal economic links with no single overarching political authority. Heterarchical arrangements of this kind constitute, in fact, a strategy to circumvent and resist centralization (McIntosh, 2000, p. 23). Finally, there is some evidence of long-distance exchange organized by commoners (McIntosh and McIntosh, 1986, pp. 437–438).

Jenne-jeno's demise has been attributed to the expansion of Islam (McIntosh and McIntosh, 1986, p. 428; Dueppen, 2016, p. 251) as the conversion of local leaders to the new faith led to the expansion of the Mali empire (McIntosh, 1999b, p. 161), in addition to the growing importance of the Saharan trade (Chipps Stone, 2015, p. 46). Jenne-jeno began declining in A.D. 900 (2015, p. 46) and was abandoned sometime around A.D. 1400 (LaViolette and Fleisher, 2004, p. 334), leaving behind what had been a successful heterarchical structure in which multiple groups created innovative means that did not include centralization, social hierarchy, or any monopoly of decision-making (McIntosh, 2000, p. 22).

Indus Civilization

The Indus civilization in Pakistan and India extended for over 1,000,000 km2 and lasted for 600 years, from 2,500 to about 1900 B.C.E (Possehl, 1998, p. 261). It represents another case in which leadership was based on an egalitarian ethos with faceless rulers or kings and a homogenous material culture that has long puzzled archaeologists (Miller, 1985; Possehl, 1998; Green, 2021). Despite its obvious sociopolitical complexity, a century of research has not yet unveiled the hallmarks of autocratic leadership embodied in palaces, sumptuous tombs, and other clear manifestations of aggrandizement (Possehl, 1998).

Harappa and Mohenjo Daro are the two largest cities, with substantial populations of perhaps 30,000–60,000 inhabitants (Dyson, 2018, p. 29). Those cities were organized on a grid pattern with citadels and warehouses (Miller, 1985, p. 47). There is also abundant evidence of public infrastructure goods, such as public drains, baths, and waste management systems (Wright and Garrett, 2017). In contrast, there is no indication of any significant disparities in wealth and resource distribution, as material culture tends to be rather standardized. Burials were modest for the dead were interred with few personal items. There is little evidence of violence either, as warrior or warfare imagery is absent and weapons few and far between (Miller, 1985).

The people of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro engaged in long-distance trade with Mesopotamia, Africa, and Central Asia (Possehl, 1997, pp. 435, 450; Wright and Garrett, 2017, p. 291). Craft specialization was widespread, but there is little indication that it was controlled in any way. Rather, those economic activities seem to have occurred in diverse spaces, including small workshops and households. Ceramic vessels often bear the potter's signature (McIntosh, 2008, pp. 391, 396). It seems, therefore, that important economic matters remained beyond the control of a selected group of people, and that the economy was largely in the hands of commoners.

The Indus civilization wound down after almost six centuries. Dramatic changes abandonment of cities, establishment of new settlements in sometimes marginal locations, reorganization of trade networks (Wright, 2012, p. 102) a proliferation of settlements but a decrease in the occupied area and average site size and a process of deurbanization that signaled important transformations in settlement and subsistence linked to changes in political and economic institutions (Possehl, 1997, pp. 429, 450). At Mohenjo Daro, the quality of houses declined and the maintenance of infrastructure, such as drains, ceased. Treatment of the dead became careless as “bodies were given perfunctory burial in disused houses or streets” (McIntosh, 2008, p. 396). There is also evidence that people hoarded and hid valuables, often a sign of a highly volatile social environment. The causes of the collapse of the Indus civilization are still not completely known but contributing factors may have included a decline in the health and conditions of the environment, changes in long-distance trade, violence, new settlers, and the monsoon season (McIntosh, 2008, pp. 396–400; Giosan et al., 2012). After the collapse, each former component of Indus society became self-sufficient, relying on its own resources and local trade networks. Regional cultures emerged with many material similarities to the earlier local cultures (Possehl, 1997, p. 450).

Cross-Cultural Recap

There are many cases of collective formations in different areas of the world that have been historically difficult to type or fit into the traditional models; the cases just discussed, and that of Teuchitlán, are all good examples. Those societies were horizontally and vertically complex, exhibited little or no conspicuous consumption, provide no clear signs of palaces, and had narrow gaps of wealth. Therefore, it is difficult to identify privileged groups in their archaeological remains, though settlement patterns indicate high populations, and we know that agricultural intensification had an important role in Chaco and Teuchitlán, while Jenne-jeno and Mohenjo Daro seem to have placed greater emphasis on long-distance exchange, though that exchange was in the hands of the common people, not a select group of individuals. These examples indicate that complexity comes in different forms and that there are differences within such collective formations that merit greater, in-depth scientific inquiry.

Concluding Thoughts

Blanton et al. (2020) proposed that more collective societies collapse abruptly, and this paper set out to probe whether Teuchitlán, an at least somewhat collective society, collapsed catastrophically as their model predicts. Teuchitlán was an atypical polity that lasted for seven centuries before suddenly disappearing, leaving few traces for subsequent developments. This shift in complexity entails the transformation of institutions both formal and informal. A view from the perspective of institutions shows the complexities of past sociopolitical structures that far exceed the simplicity attributed to the Asiatic mode of production.

In another aspect, the development of the power-sharing institutions that materialized in the guachimontones and ballcourts indicates the nature of the political structure of Teuchitlán society and the prevalence of a more inclusive, collective ethos committed to cooperation between people and governing authorities. A reliance on agricultural intensification and obsidian production for overwhelmingly local and regional consumption points to internal revenues, a variable strongly related to collective endeavors. The collapse of Teuchitlán concurs with Blanton et al.'s proposal that collective societies tend to suffer drastic, even catastrophic, effects at the time of collapse. While the causes of these upheavals may be diverse, the inability of leaders to cope with changes and continue to provide necessary services may well have led to the collapse of institutions. People readjusted to a new reality marked by a shift toward institutions that centralized power and authority, while religious institutions adopted distinctive pan-regional qualities. The new political institutions that were established developed a greater reliance on external revenues and, it can be assumed, less commitment to local populations. The institutions that had made Teuchitlán society so distinctive never reappeared and, although other collective formations emerged later, their material remains are clearly dissimilar (Heredia Espinoza, 2016). Teuchitlán thus represents an example of a society that does not conform to theoretical models about past ancient societies. Indeed, its study encourages us to eschew inflexible perspectives and, instead, analyze the complexities (institutions, structures, and organizations) of social formations through time.

There are many cross-cultural examples like Teuchitlán that are similarly difficult to catalog, and whose complexities require additional fieldwork, testing, and comparisons to more autocratic formations that tend to be relatively simple and are more familiar to archaeologists. Atypical formations like the one examined herein thus urge us to develop a new language and models capable of explaining the intricacies of such ancient societies.

Author's Note

In this article, I present Teuchitlán, an atypical society in prehispanic Jalisco which has been hard to categorize using traditional models of sociopolitical complexity. I argue that it displays features of collective societies and as such, the demise of Teuchitlán was dramatic as proposed by Blanton and colleagues. The institutions that comprised Teuchitlán underwent major changes which resulted in a new set of institutions. New settlement pattern data is presented to support the statement that collective formations tend to collapse rather drastically compared with other formations. The article provides cross-cultural examples of societies that are also difficult to describe. Finally, it adds to a growing understanding of the diverse ways in which past societies organized themselves.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

Funding for the regional surveys was provided by El Colegio de Michoacán, A.C, the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (#07012), the Secretaría de Cultura del Estado de Jalisco, the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (#131056), the National Geographic Society (#8711-09), the National Science Foundation (BCS-1219619), and the municipalities of El Arenal, Amatitán, Tequila, and Teuchitlán, Jalisco.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Stephen A. Kowalewski and Christopher S. Beekman for reading and commenting on a previous version of this manuscript. Thanks to three reviewers who provided insights and suggestions for improvement. The flaws and errors in this article are, however, my own responsibility. The Consejo de Arqueología, INAH, provided the necessary permits to carry out the surveys. Thanks to Jesús Medina Rodríguez from the Centro de Estudios de Geografía Humana (CEGH) at El Colegio de Michoacán, who crafted all the map figures.

Footnotes

1. ^Locations with remains of human habitation.

2. ^Autonomous (i.e., self-governing and, in that sense, politically independent) sociopolitical units situated besides, or close to, each other within a single a geographical region, or in some cases more widely (Renfrew, 1986, p. 1).

3. ^An arbitrary term that archaeologists use to define bounded cultural remains.

4. ^Groups of people who may share residence, kinship ties, occupational specialization, and property.

5. ^Revenue sources owned and/or controlled directly by the state (not synonymous with non-local) (e.g., landed estates, monopoly on long-distance trade; control of serf-like laborers) (Fargher et al., 2011b, Table 1).

6. ^Revenue collected by the state from free constituents or taxpayers (not synonymous with local) (e.g., income tax, sales tax, land tax) (Fargher et al., 2011b, Table 1).

References

Anderson, A. G. (1980). The rural market in west Java. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change. 28, 753–777. doi: 10.1086/451214

Anderson, K., Beekman, C. S., and Heredia Espinoza, V. Y. (2013). The Ex-Laguna de Magdalena and pre-Columbian settlement in Jalisco, Mexico: the integration of Archaeological and Geomorphological datasets. Paper presented at the Royal Geographic Society, Annual International Conference, August 2013. London.

Arnauld, C. M., Manzanilla, L. R., and Smith, M. E, . (eds). (2012). The Neighborhood as a Social and Spatial Unit in Mesoamerican Cities. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

Aronson, M. A. (1993). Technological change: West Mexican mortuary ceramics (Ph.D. dissertation). Department of Materials Science and Engineering; The University of Arizona, Tucson, United States.

Beekman, C. S. (1996). “El Complejo Grillo del centro de Jalisco: Una revisión de su cronología y significado,” in Las Cuencas del occidente de México (época prehispánica), eds E. Williams and P. C. Weigand (Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán), 247–291.

Beekman, C. S. (2003). Fruitful symmetry: corn and cosmology in the public architecture of late formative and early classic Jalisco. Mesoam. Voices 1, 5–22.

Beekman, C. S. (2008). Corporate power strategies in the late formative to early classic Tequila Valleys of Central Jalisco. Lat. Am. Antiq. 19, 414–434. doi: 10.1017/S1045663500004363

Beekman, C. S. (2010). Recent research in West Mexican archaeology. J. Archaeol. Res. 18, 41–109. doi: 10.1007/s10814-009-9034-x

Beekman, C. S. (2016a). “Built space as political fields: community vs. lineage strategies in the Tequila Valleys,” in Alternative Pathways to Complexity: A Collection of Essays on Architecture, Economics, Power, and Cross-Cultural Analysis, eds L. F. Fargher and V. Y. Heredia Espinoza (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado), 59–78.

Beekman, C. S. (2016b). “Settlement patterns and excavations: contexts of tombs and figures in central Jalisco,” in Shaft Tombs and Figures in West Mexican Society: A Reassessment, eds C. S. Beekman and R. B. Pickering (Tulsa, OK: Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art), 85–96.

Beekman, C. S. (2019). “El Grillo: The Reestablishment of Community and Identity in Far Western Mexico,” in Migrations in Late Mesoamerica, ed C. S. Beekman (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida), 109–147.

Beekman, C. S. (2020). “People, fields, and strategies: dissecting political institutions in the Tequila Valleys of Western Mexico” in The Evolution of Social Institutions, eds D. M. Bondarenko, S. A. Kowalewski, and D. Small (New York, NY:Springer), 523–553.

Beekman, C. S., and Heredia Espinoza, V. Y. (2017). Los Juegos de Pelota de Jalisco: ¿Competencia o Integración? Arqueol. Mex. 25, 64–69.

Blanco Morales, E. S. (2009). El Juego de Pelota en la Tradición Teuchitlán: Hacia una propuesta sobre su función social (Master's tesis). El Colegio de Michoacán, La Piedad, Mexico.

Blanton, R. E. (1976). Anthropological studies of cities. Annu. Rev. of Anthropol. 5, 249–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.an.05.100176.001341

Blanton, R. E. (2010). Collective action and adaptive socioecological cycles in premodern states. Cross Cultural Res. 44, 41–59. doi: 10.1177/1069397109351684

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2008). Collective Action in the Formation of Pre-Modern States. New York, NY: Springer.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2016). How Humans Cooperate: Confronting the Challenges of Collective Action. Boulder, CO: University Press ofColorado.

Blanton, R. E., Feinman, G. M., Kowalewski, S. A., and Fargher, L. F. (2020). Moral collapse and state failure: a view from the past. Front. Polit. Sci. 2, 568704. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.568704

Blanton, R. E., Feinman, G. M., Kowalewski, S. A., and Peregrine, P. N. (1996). A dual-processual theory for the evolution of mesoamerican civilization. Curr. Anthropol. 37, 1–14. doi: 10.1086/204471

Butterwick, K. (2004). Heritage of Power: Ancient Sculpture from West Mexico. The Andrall E. Pearson Family Collection. New York, NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Carballo, D. (2020). “Power, politics, and governance at teotihuacan,” in Teotihuacan: The World Beyond the City, eds K. G. Hirth, D. M. Carballo, and B. Arroyo (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 57–96.

Carballo, D. M. (2011). Advances in the household archaeology of highland mesoamerica. J. Archaeol. Res. 19, 133–189. doi: 10.1007/s10814-010-9045-7

Carballo, D. M, . (ed.). (2013). Cooperation and Collective Action: Archaeological Perspectives. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Carballo, D. M., and Feinman, G. M. (2016). Cooperation, collective action, and the archaeology of large-scale societies. Evol. Anthropol. 25, 288–296. doi: 10.1002/evan.21506

Cárdenas García, E. (2008). Método para el análisis espacial de sitios prehispánicos. Estudio de caso: El Bajío. Palapa 3, 5–16.

Carrión, H. (2019). Patrones de consumo de obsidiana en la región norte del Volcán de Tequila durante las fases Tequila II a IV (350 b.C.-500 d.C.) y El Grillo (500-900 d.C.) (Master's tesis). El Colegio de Michoacán, La Piedad, Mexico.

Chipps Stone, A. (2015). Urban herders: an archaeological and isotopic investigation into the roles of mobility and subsistence specialization in an iron age urban center in Mali (dissertation). Washington University, St. Louis, MO, United States.

Davies, M. (2013). “The archaeology of clan- and lineage-based societies in Africa,” in The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology, eds P. Mitchell and P. J. Lane (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 719–732.

Day, J. S., Butterwick, K., and Pickering, R. B. (1996). Archaeological interpretations of West Mexican ceramic art from the late preclassic period: three figurine projects. Anc. Mesoam. 7, 149–161. doi: 10.1017/S0956536100001358

DeLuca, A. J. (2019). “Dual labor organization models for the construction of monumental architecture in a corporate society,” in Architectural Energetics in Archaeology: Analytical Expansions and Global Explorations, eds L. McCurdy and E. M. Abrams (New York, NY: Routledge), 182–204.

DeMarrais, E., and Earle, T. (2017). Collective action theory and the dynamics of complex societies. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 46, 183–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-102116-041409

Dueppen, S. A. (2012). Egalitarian Revolution in the Savanna: The Origins of a West African Political System. Sheffield: Equinox Publishing.

Dueppen, S. A. (2016). The archaeology of west africa, ca. 800 BCE to 1500 CE. Hist. Compass 14, 247–263. doi: 10.1111/hic3.12316

Dyson, T. (2018). A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellyson, L. J., Kohler, T. A., and Cameron, C. M. (2019). How far from Chaco to Orayvi? Quantifying inequality among Pueblo households. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 55, 101073. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2019.101073

Fargher, L. F. (2016). “Corporate power strategies, collective actin, and control of principals: a cross-cultural perspective,” in Alternative Pathways to Complexity: A Collection of Essays on Architecture, Economics, Power, and Cross-Cultural Analysis in Honor of Richard E. Blanton, eds L. F. Fargher and V. Y. Heredia Espinoza (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado), 309–326.

Fargher, L. F., and Blanton, R. E. (2012). “Segmentación y acción colectiva: un acercamiento cultural-comparativo sobre la voz y el poder compartido en los Estados premodernos,” in El poder compartido: Ensayos sobre la arqueología de organizaciones políticas segmentarias y oligárquicas, eds A. Daneels and G. G. Mendoza (Zamora: CIESAS-El Colegio de Michoacán), 205–235.

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., Espinoza, V. Y. H., Millhauser, J., Xiutecuhtli, N., and Overholtzer, L. (2011a). Tlaxcallan: the archaeology of an ancient republic in the New World. Antiquity 85, 172–186. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X0006751X

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., and Heredia Espinoza, V. Y. (2010). Egalitarian ideology and political power in pre-hispanic Central Mexico: the case of Tlaxcallan. Lat. Am. Antiq. 21, 227–251. doi: 10.7183/1045-6635.21.3.227

Fargher, L. F., Heredia Espinoza, V. Y., and Blanton, R. E. (2011b). Alternative pathways to power in late postclassic highland Mesoamerica. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 30, 306–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2011.06.001

Fargher, L. F., and Heredia Espinoza, V. Y. H, . (eds). (2016). Alternative Pathways to Complexity: A Collection of Essays on Architecture, Economics, Power, and Cross-Cultural Analysis. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Feinman, G. (2018). The governance and leadership of prehispanic mesoamerican polities: new perspectives and comparative implications. Cliodynamics 9, 1–39. doi: 10.21237/C7CLIO9239449

Feinman, G. M., Blanton, R. E., and Nicholas, L. M. (2021). “The emergence of Monte Albán,” in Power from Below in Premodern Societies: The Dynamics of Political Complexity in the Archaeological Record, eds M. Fernández-Götz and T. L. Thurston (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 220–246.

Fox, J. G., Ashmore, W., Blitz, J. H., Gillespie, S. D., Houston, S. D., Ted, J. J., et al. (1996). Playing with power: ballcourts and political ritual in southern mesoamerica [and comments and reply]. Curr. Anthropol. 37, 483–509. doi: 10.1086/204507

Galván, L. J. (1993). El Clásico del Occidente de Mesoamérica: Visto desde el Valle de Atemajac. Unpublished paper in author's possession, Zapopan.

Garraty, C. P. (2010). “Investigating market exchange in ancient societies: a theoretical review,” in Archaeological Approaches to Market Exchange in Ancient Societies, eds C. P. Garraty and B. L. Stark (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado), 3–32.

Giosan, L., Clift, P. D., Macklin, M. G., Fuller, D., orian, Q., Constantinescu, S., et al. (2012). Fluvial landscapes of the Harappan civilization. Prod. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 10138–10139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112743109

Green, A. S. (2021). Killing the priest-king: addressing egalitarianism in the indus civilization. J. Archaeol. Res. 29, 153–202. doi: 10.1007/s10814-020-09147-9

Gregory, D. A., and Wilcox, D. R, . (eds). (2007). Zuni Origins Toward a New Synthesis of Southwestern Archaeology. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

Hayden, B. (2001). “Fabulous feasts: a prolegomenon to the importance of feasting,” in Feasts: Archaeological and Ethnographic Perspectives on Food, Politics, and Power, eds M. D. and B. Hayden (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press), 23–64.

Heredia Espinoza, V. Y. (2016). “Complexity without centralization: corporate power in postclassic Jalisco,” in Alternative Pathways to Complexity: A Collection of Essays on Architecture, Economics, Power and Cross-Cultural Analysis, eds L. F. Fargher and V. Y. Heredia Espinoza (Boulder, CO: University of Colorado Press), 79–103.

Heredia Espinoza, V. Y. (2017). Long-term regional landscape change in the northern Tequila region of Jalisco, Mexico. J. Field Archaeol. 42, 298–311. doi: 10.1080/00934690.2017.1338510

Heredia Espinoza, V. Y. (2019). Regional Survey in the Core Zone of the Teuchitlán Tradition. Report to the National Geographic Society, Jalisco.

Heredia Espinoza, V. Y. (2020). “What the teuchitlán tradition is, and what the teuchitlán tradition is not,” in Ancient West Mexicos: Time, Space and Diversity, eds J. D. Englehardt, V. Y. Heredia Espinoza, and C. S. Beekman (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida), 233–268.

Heredia Espinoza, V. Y. (2021). The built environment and the development of Intermediate Socio-Spatial Units at Los Guachimontones, Jalisco, Mexico. Lat. Am. Antiq. 32, 385–404. doi: 10.1017/laq.2021.10

Heredia Espinoza, V. Y., and Englehardt, J. D. (2015). Simbolismo Pan-Mesoamericano en la Iconografía Cerámica de la Tradición Teuchitlán. Travaux et Recherches Dans Les Amériques Du Centre 68, 9–34. doi: 10.22134/trace.68.2015.1

Heredia Espinoza, V. Y., and Mireles Salcedo, C. M. (2016). “Spatial differences in the distribution of distinct types of scrapers in the Tequila region as indicators of task specialization,” in Cultural Dynamics and Production Activities in Ancient Western Mexico, eds E. Williams and B. Maldonado (Oxford: Archaeopress), 55–68.

Herrejón Villicaña, J. (2008). “La Joyita. Un primer acercamiento a los espacios domésticos de la Tradición Teuchitlán,” in Tradición Teuchitlán, eds P. C. Weigand, C. Beekman, and R. Esparza (Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán), 63–89.

Hill, W. D., and Clark, J. E. (2001). Sports, gambling, and government: America's first social compact? Am. Anthropol. 103, 331–345. doi: 10.1525/aa.2001.103.2.331

Hirth, K. G. (1998). The distributional approach: a new way to identify marketplace exchange in the archaeological record. Curr. Anthropol. 39, 451–476. doi: 10.1086/204759

Holland-Lulewicz, J., Conger, M. A., Birch, J., Kowalewski, S. A., and Jones, T. W. (2020). An institutional approach for archaeology. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 58, 101163. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2020.101163

Houston, S. D., Escobedo, H., Child, M., Golden, C., and Muñoz, R. (2003). “The moral community: maya settlement transformation at Piedras Negras, Guatemala,” in The Social Construction of Ancient Cities, ed M. Smith (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute Press), 212–253.

Jiménez, P. F. (2018). Orienting West Mexico: the mesoamerican world system 200-1200 CE (Dissertation). University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Jiménez, P. F. (2020). The Mesoamerican World System, 200-1200 CE: A Comparative Approach Analysis of West Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Joyce, A. A., Bustamante, L. A., and Levine, M. N. (2001). Commoner power: a case study from the classic period collapse on the Oaxaca Coast. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 8, 343–385. doi: 10.1023/A:1013786700137

Kennett, D. J., Plog, S., George, R. J., Culleton, B. J., Watson, A. S., Skoglund, P., et al. (2017). Archaeogenomic evidence reveals prehistoric matrilineal dynasty. Nat. Commun. 8, 14115. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14115

Kowalewski, S. A. (2012). “A theory of the ancient mesoamerican economy,” in Political Economy, Neoliberalism, and the Prehistoric Economies of Latin America, eds T. Matejowsky and D. C. Wood (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 187–224.

Kowalewski, S. A. (2016). “It was the economy, stupid,” in Alternative Pathways to Complexity: A Collection of Essays on Architecture, Economics, Power, and Cross-Cultural Analysis, eds L. F. Fargher and V. Y. Heredia Espinoza (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado), 15–39.

Kowalewski, S. A., and Heredia Espinoza, V. Y. (2020). “Mesoamerica as an assemblage of institutions,” in The Evolution of Social Institutions, eds D. M. Bondarenko, S. A. Kowalewski, and D. Small (New York, NY: Springer), 495–522.

LaViolette, A., and Fleisher, J. (2004). “The archaeology of sub-saharan urbanism: cities and their countrysides,” in African Archaeology: A Critical Introduction, ed A. B. Stahl (Malden, MA: Blackwell), 327–352.

Ligt de, L. (1990). The roman peasantry between town and countryside. Leidschrift. Historisch Tijdschrift 7, 27–41.

López Mestas, M. L. (2005). “Producción especializada y representación ideológica en los albores de la tradición Teuchitlán,” in El antiguo occidente de México, eds E. Williams, P. C. Weigand, L. L. Mestas, and D. C. Grove (Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán), 233–253.

López Mestas, M. L. (2007). “La Ideología: Un punto de acercamiento para el estudio de la interacción entre el occidente de México y Mesoamérica,” in Dinámicas Culturales entre Occidente, el Centro-Norte y la Cuenca de México, del Preclásico al Epiclásico, ed B. Faugère-Kalfon (Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán), 37–50.

López Mestas, M. L. (2011). Ritualidad, Prestigio y Poder en el Centro de Jalisco Durante el Preclásico Tardío y Clásico Temprano. Un Acercamiento a la Cosmovisión e Ideología en el Occidente del México Prehispánico (Dissertation). Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social en Occidente, Guadalajara, Mexico.

López Mestas, M. L., and Montejano, M. (2003). Investigaciones Arqueológicas en La Higuerita, Tala. Rev. Sem. Hist. Mex. 4, 11–34.