- Department of Medical Psychology and Medical Sociology, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany

Objective: Research on the impact study participation has on participants has shown that, even though they may find it stressful during participation, overall, they appear to benefit personally and emerge with a positive cost-benefit-balance. In 2013, the first psychological study on German occupation children (GOC), a potentially vulnerable and hidden study population, was conducted, after which respondents shared a high volume of positive feedback. In the context of a follow-up survey, the impact of study participation on participants was investigated to determine the causes of this distinctly positive outcome.

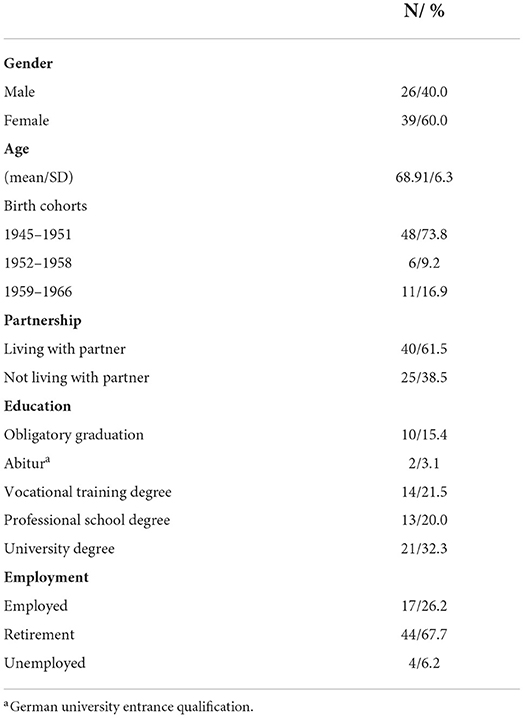

Methods: Mixed-methods approach using the standardized Reactions to Research Participation Questionnaire (RRPQ) as well as open-ended questions on expectations toward participation, and changes due to participation in dealing with GOC background and in personal life. Analyses included N = 65 participants (mean age 68.92, 40% men) and were carried out with descriptive measures for RRPQ and inductive content analysis for open-ended questions.

Results: Participants specified six motives for participation besides answering the standardized form; 46.2% (n = 30) saw their expectations met. Although participation was related to negative emotions during participation, participants' overall experience was positive; 89.2% (n = 58) stated an inclination to participate again. 52.3% (n = 34) reported participation had helped develop new ways of dealing with their GOC experiences; five contributing factors were observed. Changes in private life were reported by 24.6% (n = 16); three aspects were identified. The vast majority (81.5%; n = 53) stated, following participation, they were able to disclose their GOC background to others. Participants placed emphasis on four aspects of this experience.

Conclusion: Although study participation was described as emotionally challenging during participation, participants felt that the overall impact it had on them was positive. The study was the first of its kind and thus presented an opportunity for a previously hidden population to step out of the dark, simultaneously gaining insight that helped them better understand themselves as GOC, and thereby increase their capacity for self-acceptance. Participants also benefitted from learning about the study's findings and connecting with other GOC through activities that ensued. In conclusion, results suggest that vulnerable and/or hidden populations benefit from specific attention to their lived experiences even at higher age.

Introduction

The area of research that is focused on research impact investigates the consequences study participation can have for study subjects. In the past, studies in this area had centered around participating trauma survivors for a large part. This interest was primarily sparked by immense concerns of international research boards and ethics committees that conducting research on sensitive respondents might endanger or possibly re-traumatize them, due to supposed diminished autonomy and vulnerability. According to Newman et al. (2006) these concerns had limited the research on trauma related areas of interest for years, preventing traumatized individuals from participating, yet they were based on subjective assessments, measures and biased opinions, vulnerable to common decision making errors, such as common sense and under utilization of base rate information. Fortunately, a growing body of research on respective populations indicates that while a minority of trauma research participants recalls the initial research process as being stressful or challenging, the majority would participate again, have no regrets regarding their participation, and view research as personally beneficial (e.g., Brabin and Berah, 1995; Walker et al., 1997; Newman et al., 1999, 2001; Dyregrov et al., 2000; Ruzek and Zatzick, 2000; Disch, 2001; Dutton et al., 2002; Kassam-Adams and Newman, 2002, 2005; Newman and Kaloupek, 2004; Hebenstreit and DePrince, 2012; van der Velden et al., 2013; Lawyer et al., 2021; Robertson et al., 2021), suggesting that talking to trauma survivors might be more beneficial and therapeutically valuable rather than risky or harmful (Bassa, 2011);–provided that the research complies with common ethical principles and respects human rights (Hebenstreit and DePrince, 2012). These results have paved the way for eye-to-eye encounters with trauma survivors in research. Aside from concerns about the resilience of trauma survivors, costs of participation, as in emotional distress, are not unique experiences in trauma research, but also found in other research populations, where a small percentage of participants reports distress (e.g., Legerski and Bunnel, 2010; van der Velden et al., 2013). The limited research on long-term effects of participation also suggests few long-term negative effects (Martin et al., 1999; Galea et al., 2005 cited in Newman et al., 1999; Legerski and Bunnel, 2010). Instead results point toward an increase of affect positive appraisals over time (Newman et al., 2006; Legerski and Bunnel, 2010). In this regard, Kilpatrick (2004) cautioned that, “we should consider the ethics of not conducting important research”, since research is needed in order to determine risks for symptom development, developmental pathways and possible interventions. Therefore, a balance between the responsibility toward participants and the responsibility toward society is needed (Newman et al., 2006).

The core principles of ethical research are laid down in the Helsinki Declaration, which, though not a legally binding instrument under international law, is nevertheless regarded as the global standard for the development of legislation and regulations (World Medical Association, 2013). The key ethical principle in research is to balance the aim of “gaining knowledge” with the responsibilities to “do no harm” and “to ensure that the research does not in any way perpetuate or aggravate the specific circumstances that have put a participant at the center of the researcher's interest”(Galeziowski et al., 2021, p. 37). Another core value is the “gain for participants”, as in the benefit participants may experience from participating.

Occupation children

At the end of World War II (WWII) and thereafter, approximately 400,000 children were born to German women fathered by soldiers of the four occupying forces (Britain, France, USA, Soviet Union) (Satjukow and Stelzl-Marx, 2015, p. 12). These are called “children born of occupation” or “occupation children” in research and represent one category of children born of war (CBOW) (Mochmann and Lee, 2010; Lee and Glaesmer, 2021). The term “child” in CBOW is used to express the generational connection of a person as the “descendant of biological parents.” In a similar sense, the term “born of war” expresses the imperative connection between the existence of the person and the context of war—outside of which the person would not have been conceived. Several archival and case studies conducted by historical and social scientists have described the hardships German occupation children (GOC) faced, especially pertaining to their being “born out of wedlock” as a “child of the enemy” into a defeated and chastened former National Socialist society, where losing the war, did not however necessarily result in a change of mindset. Those studies' results hint at a disrupted sense of belonging, and emotional as well as mental distress among many in this population (Ericsson and Simonsen, 2005; Mochmann et al., 2009; Satjukow, 2009, 2011; Stelzl-Marx, 2009; Virgili, 2009; Lee, 2011; Satjukow and Stelzl-Marx, 2015). Based on these reports of difficult developmental conditions and hardship, we define GOC a potentially vulnerable group.

GOC study, results, and further studies

The first psychological study on GOC was conducted in 2013 and focused on three main aspects: identity development, stigmatization/discrimination, and child maltreatment (Glaesmer et al., 2012). It aimed at investigating the psychosocial consequences of growing up as GOC in a post-WWII societal context. Via press release and contact with platforms/networks of occupation children, 164 people were recruited, of which 146 were included in the analyses (mean age 63.4, 63.0% women). Since CBOW are difficult to reach, and their population size is small and can only be estimated, they constitute what is termed a “hidden population”. These populations cannot be investigated solely by standardized instruments, rather they also require the use of a participative research approach that involves tailor-making instruments capable of capturing their lived experiences (Heckathorn, 1997; Salganik and Heckathorn, 2004). Participative research enhances chances of acceptance and compliance among the target population (Brendel, 2002). Therefore, an instrument for GOC was developed that consists of two parts. The first was self-developed for capturing experiences specific to this group of CBOW as deduced from literature and a participative process involving occupation children and experienced researchers in this field. The second part consisted of standardized psychometric instruments designed to assess current mental distress and traumatic childhood experiences (among others) (Kaiser et al., 2015a). Findings were compared with a representative birth-cohort-matched sample (BCMS) from the German general population (where available). In summary, the study results show that GOC resemble a subpopulation of the general German population with very specific developmental conditions (Kaiser et al., 2015a; Kaiser, 2017). According to the theoretical framework relevant to the study of the psychosocial effects of growing up as a CBOW (Glaesmer et al., 2012; Kaiser, 2017), findings show that GOC's developmental conditions (post-WWII social environment with resentment, single mothers, financial hardship, change of primary caregivers) made them vulnerable to child maltreatment (Glaesmer et al., 2017), high impact traumatic events (Kaiser et al., 2015b), inconsistent attachment experiences (Kaiser et al., 2016), and experiences of stigma and discrimination (Assmann et al., 2015). Moreover, experiences of child maltreatment, high-impact traumatic events, and inconsistent attachment were associated with current psychological distress (depression, somatization, PTSD), underscoring their long-term effects (Glaesmer et al., 2017). Once the data had been analyzed, all former participants, as well as other interested parties, were informed about the study results in a newsletter sent by mail.

In a further step, the GOC questionnaire was translated to investigate other CBOW populations, namely occupation children in Austria (AOC), “Wehrmacht children” in Norway, and children born of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the 1990s as part of the Yugoslav Wars.

In a descriptive analysis of quantitative questionnaire data from GOC and AOC, the impact that secrecy around the subject of those participants' origins/fathers has had on them was analyzed (Mitreuter et al., 2019). For obvious reasons, many occupation children were not told the truth about their origins/fathers until adulthood, and the older the people were when they were informed, the more painful the realization was. After learning the truth about their origins, most set out to find their father, hoping in particular to identify commonalities (in personality and physical appearance) with them. Both AOC and GOC reported similar experiences.

Previous work in a follow-up interview study (Chibow.org, 2019) addressed how occupation children born of sexual violence (CBSV) experienced their relationship with their mothers. Roupetz et al. (2022) were able to show that CBSV report a great diversity of experiences and that this had a lifelong impact on them. Based on CBSV's descriptions of their past and present relationships with their mothers, three broad groupings could be identified: conflictual relationships, an absent parent, and positive upbringings. Positioned along three axes of relationality, the participants' perception of their relationships with their mothers fell into categories of patterns of interaction that emerged: accountability and agency vs. exoneration and victimhood of the mother; accountability and agency vs. exoneration and victimhood of the child; longing vs. detachment.

Distelblüten

A non-scientific, but very congenial and touching result of the GOC study was the foundation of a network for GOC whose fathers were deployed for the Soviet Army. Today they call themselves “Russenkinder” or “Distelblüten” (engl. “Russian children” or “thistle blossoms”), maintain a website (https://www.russenkinder-distelblueten.de/english/), and have an annual meeting in Leipzig, Germany. Out of this network a literary collection of life stories has been published, and readings are held regularly, sometimes even abroad (Behlau, 2015).

During the recruitment stage of the initial project named “Occupation Children: Identity Development, Stigma Experiences, and Psychosocial Consequences of Growing up as a 'German Occupation Child”' (Kaiser, 2017) it became evident that some GOC (German occupation children) had not dealt with their origins/past before that point. Some reported that they had previously believed their experience to be an isolated one. Others reported years of searching and finding or not finding their father, and described the impact those efforts had had on their lives. After the survey was conducted, many participants spontaneously followed up with phone calls, emails, and letters to add more detail to their story. Topics they commonly brought up were: their relationship with their mother, longing for their father, the path of and sometimes struggle for personal development, tensions related to integration efforts, and the ways they were burdened by their life story. In some cases, people described having a strong sense that they needed to make something of their life and be successful in some way. Simultaneously, many also described how, despite having achieved that, they still felt subject to emotional impairments such as burnout, depression, mood swings, and distrust, responses that correspond with the results of the survey. Some gave feedback expressing thanks to the researchers for having finally taken up this topic, along with hope that more justice and visibility will result. Others reported that their participation had initiated intensive reflection processes, which led them to a better understanding of their mothers and a more coherent comprehension of their own biographies. For others, participating in the study prompted them to search for their father (again) or to write down their life story.

Research interest

The intense feedback of former participants led to the idea of empirically investigating the long-term impact of study participation on GOC. Our initial study on GOC was the first of its kind; following it, our aim shifted to examining the effects study participation had on the respondents and learning about the root causes of the reported positive and strong effects.

Thus the present study was conceived to explore the following questions:

What reasons led GOC to participate in the initial study?

What initial reactions do participants report regarding study participation?

What expectations did GOC have of study participation and were these fulfilled?

Would participants participate again?

What changes did participants notice in dealing with their GOC background as a result of study participation?

What changes did participants notice in their personal life as a result of study participation?

What experiences have participants had if they exchanged with others about their GOC background or went public (as a result of study participation)?

Materials and methods

To investigate the root causes of the reported positive observations following study participation, the study attempted an overall equal-status pragmatist mixed research approach (Johnson, 2011; Johnson et al., 2017).

Instruments

In adherence to the study questions a two-part survey was designed comprised of: Part (I) a questionnaire (RRPQ, Newman et al., 2001) measuring respondents' quantitative, standardized reactions to research participation, translated into German in accordance with state of the art standards (Bracken and Barona, 1991; International Test Commission, 2005). Part (II) was developed in a participative process and piloted in cooperation with GOC and colleagues from the field that involved discussing quantitative and qualitative questions about expectations, research impact, remaining questions, and GOC's wishes. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Leipzig University.

Part I: Reactions to research participation questionnaire (RRPQ)

The RRPQ (Newman et al., 2001) is a two-part standardized instrument comprised of nine items for ranking the top three reasons for study participation and a 23-item scale assessing participants' reactions to research participation on five subscales: general attitudes about personal satisfaction (participation; four items), personal benefits gained from participation (personal benefits; four items), emotions experienced during the protocol (emotional reaction; four items), perceived drawbacks of the study (perceived drawbacks; six items), and global appraisal of the research protocol (global evaluation; five items). Each subscale gets scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale with response options ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Means were calculated for each subscale, whereby higher scores indicate more positive reactions to the research experience. The RRPQ has good reliability and validity (Kassam-Adams and Newman, 2002; DePrince and Chu, 2008; Schwerdtfeger, 2009).

Part II: Self-developed instrument

This instrument focused on seven main topics: (1) Expectations of study participation in respondents own words (three items); (2) readiness to participate again (three items); (3) changes due to participation in dealing with own GOC background (three items); (4) changes due to participation in private life (five items); (5) experiences in exchange with others about GOC background and going public (after study participation); (6) topics/questions still relevant today (three items); and (7) wishes for occupation children (three items). A mix of open-ended and quantitative questions was designed for each topic; each section consisting of superordinate and refining subordinate questions. The first five topics were relevant to the research questions presented and will be analyzed below. The exact wording of the questions will be introduced at the beginning of each results section. The complete questionnaire is available online as supplement 1 (Kaiser and Glaesmer, 2022).

Participants

In 2017 the questionnaire was sent to all N = 146 participants in the initial study. Ten envelopes were returned due to failed delivery attempts (five addressees unknown, two deceased, three no interest). Of the 67 returned questionnaires, two were missing written consent and thus were excluded (44.8% response rate). Overall N = 65 (mean age 68.91, 40% male) response sets were included in the analyses. The sociodemographic sample characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The biological father of participants had served in the US army in 49.2% (n = 32) of cases, while 20% (n = 13) were the offspring of a member of the French Army, 24.6% (n = 16) of the Red Army, and 3.1.% (n = 2) of the British Army. 3.1% (n = 2) did not know their procreator's origin. The majority stated they were conceived by voluntary sexual activity (78.5%; n = 51), 7.7% (n = 5) were conceived by rape, and 12.3% (n = 8) did not know their procreational background.

Analyses

Quantitative analyses

Quantitative analyses using IBM SPSS Statistics 21 for Windows were conducted to obtain mean scores and frequencies for the RRPQ according to instructions in the RRPQ original version (Newman et al., 2001), as well as for sociodemographic values and quantitative measures of the self-developed instrument.

Qualitative analyses

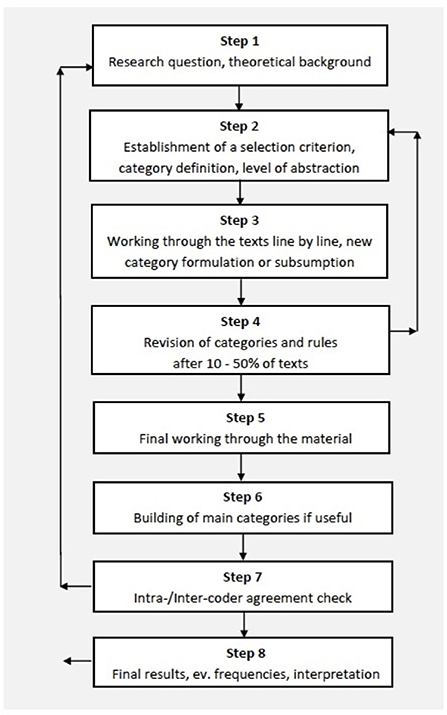

The qualitative analysis of the responses to the self-developed, open-ended questions of the questionnaire was conducted by means of qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2010, p. 601). Since our initial study on GOC was the first of its kind (on CBOW in general) and the experiences of CBOW are very specific, an explorative design was the best choice to learn about the root causes of the observed positive and strong effects reported by the participants after participation [Mayring, 2014, p. 12, 79]. The qualitative analysis thus followed a summative approach, aiming to find conclusions about key statements, aggregated to more abstract inductive levels (Mayring, 2010, p. 602). Relating to the step model of inductive category development (see Figure 1; Mayring, 2014, p. 80) a criterion of definition was formulated derived from GOC‘s personal post-participation feedback. Accordingly, the qualitative analyses focused on the following topics: (1) expectations in own words; (2) changes due to study participation in dealing with GOC background; (3) changes due to study participation in personal life; (4) experiences in exchange with others about GOC background and going public (after study participation). Under application of this criterion the data was read and preliminary categories were derived in a step by step process. This process is reflexive, categories are revised and reduced to main categories; their reliability is inquired. The data set of statements to the above mentioned four open-ended questions served as material for analysis.

Figure 1. Steps of inductive category development (Mayring, 2014, p. 80).

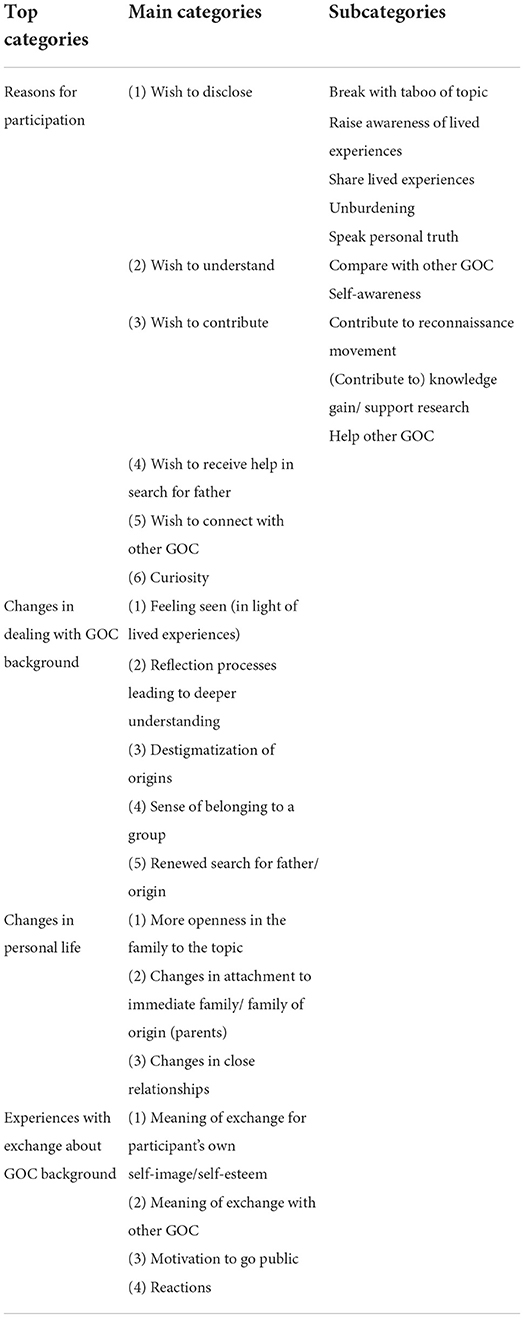

Sometimes a statement was related to another question of the questionnaire and was then reassigned to the respective section. Please refer to Kaiser and Glaesmer (2022) for the final category system with example quotes (supplement 2), as well as the analysis table with the corresponding quotes (supplement 3). An overview of the top, main and subcategories is shown in Table 2. The original language of the material was German. The data was coded by the first author and, according to the step model, checked for intra-coder reliability by re-visiting parts of the material after 10–50% of material. Inter-coder reliability was checked by the second author, coding material selectively. Quotes were translated by the first author and an English native speaker independently, then discussed and finally consented for best fit.

Results

Part I: RRPQ

Reasons for participation

According to the RRPQ, leading motivators for participation were: curiosity (73.8%; n = 48), the wish to help oneself (53.8%; n = 35), the feeling that participation was necessary (53.8%; n = 33), and the wish to help others (47.7%; n = 31). Thirteen participants mentioned an additional topic (other, 20%, n = 13), namely, to support research on the topic. Further responses on the list were: “I didn't want to say no” (12.3%, n = 8), and “I thought it might improve my access to health care” (9.2%, n = 6). Multiple answers were possible.

Impact of research

According to four of the five scales of the RRPQ, participants' experiences with study participation were positive and above average ratings. Scales were rated from 1 to 5 and assessed: general attitudes about personal satisfaction (participation; mean/SD = 4.25/0.49); personal benefits gained from participation (personal benefits; mean/SD = 3.94/0.75); perceived drawbacks of the study (perceived drawbacks; mean/ SD = 4.54/0.37); and global appraisal of the research protocol (global evaluation; mean/SD = 4.53/0.37). In general, the higher the scores, the more positive the reactions were to the research. On the “emotional reaction” scale, describing emotions experienced during the protocol (emotional reaction; mean/SD = 2.89/0.98), participants gave their experience below average ratings indicating a rather negative emotional experience during participation.

Part II: Self-developed part

Expectations

“Were your expectations met?”

Almost half of all participants, 46.2% (n = 30), said their expectations were fully met; 33.8% (n = 22) reported this to be partially the case; and 9.2% (n = 6) said their experience of participating did not meet their expectations.

“Can you briefly describe in your own words what your expectations were for participation in the study?”

When asked to express their motivation to take part in their own words, participants stated a variety of different expectations that are described below and supported by representative quotes. Six different main categories were identified: (1) wish to disclose; (2) wish to understand; (3) wish to contribute; (4) wish to receive help in search for father; (5) wish to connect with other GOC; and (6) curiosity. Some participants stated they had no expectations but further explained what their reasons for participation were. The first three main categories contain further subcategories, explicated in each of the following sections.

Wish to disclose

The wish to disclose spoke out from many texts and was presented with finely nuanced differences. Sometimes the desire to share was linked to the intention to break the taboo around the topic of one's own origin or seen as an opportunity to tell their personal truth. Others wanted to raise awareness for their lived experiences or to simply share them with others. For some, participation was a way to unburden themselves.

Break with taboo of topic: Participants described wanting to participate in order to (finally) overcome the stigma of their origin and to break the taboo around the topic.

“[…] To draw attention to what was denied and kept silent. To personally meet people with the background of experience of being a child of occupation. […] To be an object of this investigation and still be a subject.” ID46

“Participation in the study was very important to me, because these problems of the “Russian children” were never talked about (in the GDR1).” ID154

Raise awareness of lived experiences: Participants aim to bring light into the darkness, and draw attention to themselves and their experiences. By participating they hope to raise visibility of the topic in public.

“First and foremost, I wanted to help shed some light on the subject, i.e. I wanted to support the scientific work. The consequences of the war are intensively studied in the media, but not the psychological side. In my opinion, this is neglected. Just as there was a silence in my family about who my father was, my producer, better said. This carries through into 'big' politics.” ID16

Participation is also seen as a chance to contribute to a reappraisal of history, their life story, and to pass on their legacy.

“The subject of occupation children had exclusively negative connotations at the time of my birth and adolescence. Their raison d'être was denied by different parts of the population. In many cases, even by their own mothers. Even their procreators felt no obligation and were supported in this by the military services of the occupying powers, who sometimes also forcibly prevented them from claiming their children. These omnipresent rejections have shaped this generation. I do not want this part of history to be simply forgotten. That is my expectation of this study.” ID45

Share lived experiences: Participants describe participation as a possibility to share lived experiences.

“[…] But came to participate without any fixed expectation. I hoped to share my thoughts, feelings, and my experiences. I knew that many people shared my fate, each in their own way.” ID88

Unburdening: Participation was described as a means of unburdening through having a context within which one's life story could be dealt with without shame. The precondition for this purpose is understood to be having someone who is genuinely interested, listens, and believes.

“I wanted to be heard for once. I wanted to be understood. I wanted to unburden myself by opening up without fear of being made to look like a liar.” ID62

Speak their personal truth: Participation was also seen as an opportunity to finally speak one's truth, and thereby challenge the established generally accepted view (in the family). Participants want to feel seen with their burden and know that it is recognized. To do this, they want to be able to tell their story, an act that, for them, is predicated on being heard and taken seriously.

“For once in my life I had the opportunity to write or say everything about how I felt as a child, student, adolescent, and to some extent as an adult with this past. The subject was taboo in the family. Even today, my mother's point of view is considered correct. She denies me having problems with it.” ID98

“I didn't have any expectations. It was only important to me that I was allowed to tell my story, and to people I was sure would take me seriously, maybe that was my expectation. That I'd be taken seriously.” ID175

Wish to understand

For some participants, participation was also motivated by the hope of finding out something about themselves, their own origins, in order to better understand. This intention was also expressed by the desire to be able to compare themselves with other GOC.

Compare with other GOC: Another reason for participation was described as an interest in learning more about other GOC for purposes of comparison and alignment, for example, regarding how others deal with their past, their experiences, and their current condition.

“Since I felt I was alone with my fate before, I wanted to know if there were others with similar experiences and feelings.” ID8

“That many others who participated would become a kind of witness to my own story with their accounts, as well as the feeling of not being alone in this.” ID131

Self-awareness: Participants also voiced the hope that study participation could help them gain insight into their life story and could also be beneficial to processing their lived experiences.

“I hoped to get answers to questions that had been unspoken since I was a kid. Why the bad relationship with my mother, why am I mostly a loner, etc.” ID53

“My expectation was to get clarity about myself again, while supporting scientific research in the field.” ID144

Wish to contribute

Furthermore, participation offered the opportunity to make a personal, societal contribution, and thus be connected to something larger. This contribution could be the connotation of participation as helping other GOCs or as enriching public knowledge through the support of research.

(Contribute to) knowledge gain/support research: Participants stated their participation was motivated by a desire to promote knowledge growth and/or to gain more knowledge themselves.

“More information for society! But also information for affected persons to cope better.” ID30

“1) That as many as possible participate. 2) That the results are presented publicly. 3) New knowledge is gained.” ID40

Contribute to enlightenment movement: Participation can also be seen as being part of a peaceful movement.

“[…] To be part of a peace initiative, to live understanding and bridge building. […]” ID46

Help other GOC: Participants want to help other GOC find their fathers, give them hope for it, or encourage them to disclose their heritage and contribute to the reappraisal of the past for the benefit of other GOC.

“Helping others to go more public. To be open with the past. To stand by who you are. Talking about it with those around you, associations, friends.” ID68

“To help other occupation children, who have not yet come out, with my experiences.” ID153

Wish to receive help in search for father

Others hoped to find out more about their father by participating, or that they might receive assistance in finding their father, for example, via access to contact addresses or perhaps archives.

“[…] My expectation was actually that I could possibly, through this study, gather clues about my father, origin, date of birth […].” ID75

“My expectation was to find my father - to better understand the time back then.” ID116

Wish to connect with other GOC

A further motivator was the hope of meeting other GOC.

“[…] Getting to know people with the experience background of an occupation child personally. […]” ID46

“[…] To meet others with similar fates; […]” ID153

Curiosity

Finally pure curiosity was also a motive for participation.

“When filling out the questionnaire, I had no expectations. I assumed it was for research purposes only and didn't expect to get any feedback. At the same time, I had tried to get other contacts, but received no response […] actually, I was just curious, with no expectations.” ID18

“I was curious. A mixture of curious and anxious feelings. I reveal a lot and show my vulnerable sides. On the other hand, it's useful for others affected to shed light on the story.” ID64

Further participation

“Would you participate again?”

When asked if they would participate again, the majority (89.2%; n = 58) stated they would be very likely to: 72.3% (n = 47) answered “yes, definitely”, 16.9% (n = 11) “probably yes”. Only 4.6% (n = 3) would most likely not participate again: “probably not” 3.1 (n = 2), “definitely not” 1.5 (n = 1).

Changes due to study participation in dealing with the GOC background

“Has participation in the study changed anything about how you deal with being an occupation child today?”

In this section of the questionnaire, participants were asked if they had noticed any changes they may have experienced due to participating in the study. This was done via: (a) a binary question; (b) a request to rate these changes on a scale of 1 (negative) to 10 (positive); (c) a request to describe those changes in their own words.

Half of the participants stated that they had noticed changes in how they deal with their GOC background as a consequence of study participation (52.3%; n = 34). Changes were perceived to be rather positive (MW 7.85/SD 2.35, MIN = 0, MAX = 10; n = 37).

The changes participants described in their own words were coded into five main categories: (1) feeling seen; (2) reflection processes led to deeper understanding; (3) destigmatization of own origin; (4) sense of belonging to a group; and (5) renewed search for the father/origin. When breaking the categories further down, it seemed that, to a certain degree, some categories built on each other in terms of content.

Feeling seen (in light of lived experiences)

Overall, participants considered it a positive thing that someone took on the topic and showed a genuine interest in their story. They particularly emphasized that it had been an important experience for them to not be treated with inhibition or judgement.

“No one has been derogatory or amused or dismissed my story as if it was all not so bad.” ID 175

“Questions were asked or situations were addressed that I personally could not share or discuss with anyone before.” ID 184

Reflection processes leading to deeper understanding

Dealing with the topic set in motion reflection processes, which in part led to participants reassessing their own life story and thus gaining a deeper understanding of their own behavior/emotions, and by extension a greater sense of self-assurance.

“A change in self-awareness, at times, I can better categorize feelings/behaviors because I am more aware of the connection to my biography.” ID 11

“I believe that, among other things, participation has enabled me to further process and integrate my life story and thus at least gain more distance from it. So things have been put into perspective a little bit.” ID 41

Destigmatization of origins

Participants described experiencing a more positive sense of self and satisfaction overall after study participation. This aspect entailed participants developing a more self-accepting approach to their origins, thereby making it possible to destigmatize those origins. This flowed out of participants being able to talk and deal more openly with their own life story.

“I could never talk about the subject without trepidation although my family and acquaintances knew “everything.” After the study and our Leipzig meetings, dealing with the topic feels relaxed and low-pressure for me. We talk about it more often and my family is very interested.” ID 88

“[…] the flaw that I knew how to hide outwardly well has also dissolved inwardly afterwards.” (ID 162)

Sense of belonging to a group

Participants reported that due to the researchers communicating the results of the study with them they were able to see the larger picture of the entire GOC situation. They talked about how they are now able to classify themselves and their biography within this group, and emphasized their sense of belonging to a group. This experience offered participants the chance to compare their shared fate and recognize parallels. This aspect in particular, of no longer being alone with their own life story and getting in touch with other GOC for the first time, was described by many as novel and satisfying.

“A year before the study started, I found my father and I know how important the topic can be in the minds of those affected. I feel more like an “equal among equals” after the study, and meet other people more impartially; enjoy listening to other biographies.” ID 29

“Your study results from (date) confirm that there are still many occupation children who are searching. You somehow feel like you belong to this group and would like to contribute your experiences as well.” ID 117

Apparently, learning about the situation of other GOC via the study results had a strong self-affirming effect for participants, and seems to have made a decisive contribution to the positive development and re-evaluation processes many participants described undergoing.

Renewed search for father/origin

In addition to the reflection processes about the past and the enriched knowledge about the fate of others, for some, study participation triggered a (renewed) search for their biological father and/or the desire to learn more about their origin.

“Unlike others, I began for the first time to deal intensively with my story of origin, the circumstances surround it, concomitants, etc. Since I didn't know anyone of the same origin and hadn't had any negative experiences, this had not been much of an issue in my life up to that point, especially not in the society of the GDR2. The subject of occupation children only became an issue as a result of my participation. Since then it's occupied me daily!” ID 18

“Answering the questions helped me systematically examine my own thoughts and feelings as well as my life story, and furthermore motivated me to research the identity of my biological parents.” ID 144

Changes due to study participation regarding personal life

“Has anything changed in your personal life (e.g., family life, home environment) as a result of participating?”

This section addressed changes in personal life catalyzed by study participation. Participants were asked about changes they had observed with: (a) a binary question; (b) a request to rate those changes on a scale of 1 (negative) to 10 (positive); (c) a request to further explore the nature and extent of those changes in their own words.

One quarter (24.6%; n = 16) reported changes in their private life due to study participation, changes that were deemed positive developments (MW 7.05/SD 2.64, MIN = 1, MAX = 10; n = 22).

Responses to this question dealt with issues that fell into three main categories: (1) more openness in the family to the topic; (2) changes in attachment to immediate family and family of origin (parents); (3) changes in close relationships.

More openness in the family to the topic

After participation some participants experienced more openness in their family.

“Within the family it was a difficult subject, everything has become more relaxed.” ID 82

“Approaching the topic needed a lot of tact in the family (German family). But suddenly the aunts who were still alive could talk about it more openly.” ID 184

Changes in attachment to immediate family/family of origin (parents)

For others, their own reflection stemming from their participation led to changes in attachment to family members.

“Interaction with my parents has become even more important to me and the need to visit my family in England even more intense, as well as, unfortunately, the pain of separation when I leave there again.” ID 85

“I have more confidence and can hold my own. With my sister I shared many memories from our childhood and since then we get along well and are closer than ever.” ID 166

Changes in close relationships

For some, addressing the topic also seems to have led to changes in close relationships, such as breakups or relationship clarification.

“I think it wasn't the study. It was the whole process. My shame is gone, my husband is gone. I was so happy and full about finding [my father3], there was nothing else for me. It was such a longing before, that I plunged in.” ID 64

“So-called friendships drifted apart, there was a distance. My marriage that was ailing ultimately ended in divorce.” ID 68

A careful hypothesis here is that, in taking up the topic, some GOC may have experienced a legitimization of addressing the topic intensively, which led to a new clarity or a greater awareness of their own existential core and identity, and thereby empowered them to prioritize within or even end unstable relationships.

In sum, these statements are to be seen in connection with the processes described in the previous section. By reevaluating one's own origins and experiencing a sense of belonging within a group, a basis for a new sense of identity and new self-confidence can emerge. This may have given participants the courage to open up.

Experiences in exchange with others about GOC background and going public (After study participation)

“Were you able to speak to others about your GOC background or did you go public? If so, what experiences have you had with it?”

This part of the questionnaire resembles a subsection of the section on changes in dealing with being an occupation child and concerns disclosure regarding their GOC background.

The vast majority of participants (81.5%; n = 53) stated they were able to disclose their GOC background to others or went public following study participation.

The answers to these questions particularly emphasized the impact of disclosure and exchange. Participants' statements regarding their experiences were sorted into four main categories: (1) meaning of exchange for participants' self-image/ self-esteem; (2) meaning of exchange with other GOC; (3) motivation to go public; (4) reactions. The fourth category delineates three different types of reactions: mixed, positive, negative, of which the first two were predominant.

Meaning of exchange for participants' self-image/self-esteem

Participants emphasized the positive effect of disclosure on their self-image/self-worth. They reported receiving recognition and compassion when disclosing; and they felt pride through talking about their origins with others.

“A lot of positive feedback, high regard, and recognition came from important personalities. This was very good for my self-esteem.” ID 8

“Very good experience! Sympathy, exchange of opinions, interest from media, and my pride solidified!” ID 63

“For many it was an unknown story, the subject of occupation children, in general. However, I gained personal recognition.” ID 184

Meaning of exchange with other GOC

The other, apparently very important, aspect of participation seems to be the connection it facilitated with other GOC. The following statements refer to the meetings held by the “Distelblüten” (thistle blossoms) group. In such a group, participants feel they can be a part of the lives of others, feel understood, and secure. Connecting to other GOC (for the first time) is also associated with arriving at oneself.

“The evaluation of the study has brought some satisfaction. A wonderful “family” has been found, the group around [Distelblüten initiators]. I can participate in the lives of other Russian children, can speak freely and feel secure in the group. And maybe my search will be successful, I will report about it later - whether successful or not…?” ID 88

“The outcome statistics didn't show me much, but the personal contact with affected people did. Without participation in the study, these connections would not have been possible.” ID 8

According to these testimonies on experiences with disclosure, contact with other GOC seems to have had a self-affirming effect, an element that is related to having a sense of belonging and thereby helps strengthen a person's identity. This aspect is also resembled here:

“There was a change in attitude toward life toward the positive, no more depressive thoughts. New-found good connections, conversations - worldwide.” ID 8

“I could only “give free rein” to thoughts and feelings at our second meeting in Leipzig. It felt like an arrival.” ID 88

These testimonies illustrate how powerful and empowering the experiences of speaking up and coming out are, as well as being in connection with people with shared background and experiences. It is possible that the experience of exchanging about their shared GOC background had a positive reinforcing effect on participants' self-esteem - a result of positive reflection processes initiated during study participation and continued by learning of the results and networking with other GOCs.

Motivation to go public

Some participants felt motivated to share their story with the public, e.g. by publishing their biography/book on the topic, giving talks, or participating in interviews.

“It has always been talked about [in my family]4. However, rarely. Writing about my life story and origins did the family, above all, the children, a service. I organize readings of the book I helped to write. I have become more 'aware' of my origins. Positive. Proud? Close. In one case, an aunt made negative and derogatory comments about my mother after reading about me in the local press. There are positive reactions from other relatives and acquaintances. I'm intentionally going public.” ID 18

“Am more confident about this. Have given talks and made an effort to formulate something.” ID 46

“At my age, you get thoughtful. You gave me the right push to actually publish my book, i.e. my autobiography. Thank you for that. My participation has made me courageous, has made me strong!” ID 62

Reactions

Generally, participants reported very different reactions to disclosures of their background or talking openly about the GOC topic.

Mixed reactions

“Open-mindedness to shirking.” ID 42

Positive reactions

Positive reactions to participants' disclosures were perceived as relieving, beneficial, and inspiring.

“Positive! I was amazed at the response the telling of one's own fate can elicit, even to the point of sympathy.” ID 29

“Since participating in the study, I have mustered the courage more often to talk to others about my background, and to my relief, everyone has responded positively.” ID 166

Negative reactions

Negative reactions were described as depressing, disappointing, and discouraging.

“In personal conversations, I have found that others can hardly comprehend the impact that rape, even more so by an occupying soldier, can have on the personal development of the resulting child.” ID 81

“Only or mostly bad experiences. Depressing. Questions like: 'Why are you doing this? You've always been fine. No reaction at all.” ID 121

Discussion

Following a study on the psychosocial consequences of growing up as an occupation child in post-WWII Germany, many participants shared personal feedback on the study, including descriptions of positive developments they experienced later on due to their participation. The results of this initial study showed the potential long-term impact of unfavorable developmental conditions, as well as stressful to potentially traumatic experiences for many but not all participants (Kaiser, 2017). The aim of the present study from 2017 was to explore which aspects of participating in the 2013 study influenced GOC respondents' positive feedback and the positive developments in their personal lives so many of them reported. Furthermore, we were interested in learning what benefits participants derived from the initial study and what conclusions can be drawn for future studies on CBOW and other potentially vulnerable/ sensitive and/or hidden populations. Lastly, since there was a time span of more than 3 years, between the initial study in 2013 and the present study, it can be understood as an investigation of a long-term participation impact. Our initial study was the first in the field to use a psychological approach on GOC. The present study revealed that, although respondents found it emotionally challenging to participate in the survey of the initial study itself, they also observed that the mid- and long-term impacts of taking part in the study were positive overall. According to the RRPQ, leading motivators for participation were: curiosity, the wish to help oneself, feeling that participation was necessary, wanting to help others, and a desire to support research on the topic. These findings were mirrored when the participants were asked to explain their expectations of the experience in their own words. Six different motivations were identified including: (1) wish to disclose (break with taboo of topic, raise awareness of lived experiences, share lived experiences, unburden themselves), tell their own truth), (2) the wish to understand (compare with other GOC, increase self-awareness), (3) the wish to contribute (contribute to enlightenment movement, (contribute to) knowledge gain/support research, help other GOC), (4) the wish to receive help in search for father, (5) wish to connect with other GOC, and (6) curiosity. Almost half the participants saw their expectations met and the majority said they would participate again. With regard to possible changes experienced resulting from participating in the study, half of the participants stated that they had noticed changes in how they deal with their GOC background, and that those changes had been predominantly positive. Five different categories of change following study participation were identified: (1) Feeling seen; (2) reflection processes leading to deeper understanding; (3) destigmatization of origins; (4) sense of belonging to a group; (5) feeling prompted to renew their search for their father/origin. One quarter reported experiencing changes for the better in their private life due to study participation. Three main areas of change were identified: (1) More openness in the family to the topic; (2) changes in attachment to immediate family/family of origin (parents), (3) changes in close relationships. The vast majority of participants stated they were able to disclose their GOC background to others or went public following study participation. Four aspects were especially emphasized by participants: (1) meaning of exchange for the person's self-image/self-esteem; (2) meaning of exchange with other GOC; (3) motivation to go public; and (4) reactions (to disclosure).

Our study showed that people who grew up as GOC predominantly benefited from the attention they received as part of the process of participating in the study (interest in their life story, removal of taboos, acknowledgment of specific living conditions and associated challenges, having their say, being seen). This phenomenon has been described as the participants' “genuine need to ‘have their voices heard”', and has been reported of other CBOW populations as well (e.g., Lee and Bartels, 2019a). Moreover, our findings are in line with studies on risks and benefits in (trauma) research participation, stating that despite a possible negative emotional reaction during the study protocol, the majority reported beneficial aspects resulting from participation. Reported benefits were such as finding it useful to reflect on and think about experiences, even if painful (Dyregrov et al., 2000); gain new insight, find it generally helpful to be able to talk about experiences, and that participation clarified past memories (Carlson et al., 2003). Another study reported increased self-esteem, the feeling of self-empowerment and validation, as well as continued positive changes following research participation (Disch, 2001). Parallels to these statements are found in our results as main effects of participation reported by our respondents were their new-found sense of community with other GOC, social acknowledgment, and increased levels of self-acceptance and self-esteem. Participants said that filling out the questionnaire facilitated reflection processes that deepened their understanding of themselves, and that they felt better understood by others in the context of their GOC experiences. It seems that for some, a long-held desire for a sense of belonging was met through activities that took place in the wake of the study, including communication pertaining to the study results and opportunities to exchange with other GOC. GOC were able to compare their lived experiences with those of other GOC, and thus felt affirmed in their own perceptions and feelings. To gain this benefit, even at a later stage of life, appears to be a deeply empowering experience.

In addition to the similarities in benefits with other research populations another notable aspect of our study results is, that the participants' evaluation of the experience was more positive than has been the case among the populations presented by Newman et al. (2001; individuals with PTSD, trauma experience, unaffected) in the RRPQ validation study. It does appear that in the present case, the participants' gain outweighed the costs, whereas in former studies there seemed to be an equipoise between costs and benefits for participants. With this clearly positive evaluation, our study results contribute to the conclusion, that obviously people in general, whether “unburdened” or carrying a “hidden” burden (e.g., traumatized individuals, people with PTSD), stand to benefit from the attention they receive and being heard while participating in a study.

Another interesting finding concerns recurring questions participants have lived with regarding their identity (e.g., lack of information about their origin, their father, the relationship between their mother and father, and by extension, themselves) accompanied by a strong urge to fill in these gaps in their knowledge. These needs are reflected in the expectations participants had toward study participation. Participants reported feeling a need to tell their story, be heard, and be taken seriously. They wanted to unload their emotional burden and break the taboo surrounding their origins. As far as the desire for belonging described by so many of the respondents is concerned, this aspect of the GOC experience can be seen as an expression of the universal and fundamental human need to feel one has a right to exist and is welcome in the world, to be seen in the context of one's lived experiences, and to being able to locate and understand one's self.

Similar questions, needs and aspirations have been described for other CBOW populations as well (Schretter et al., 2021, p. 60) and may be explained by similar specific developmental conditions that influence CBOW growing up and impede healthy development, leaving these individuals with similar existential topics to deal with in their lives (lack of opportunities, need for understanding, desire for belonging and being accepted). Furthermore, research on adopted and sperm donor children clearly showed that knowledge of one's origins is central to identity development (Turner and Coyle, 2000), as is the perception and appraisal of children by their social surroundings and society (von Korff and Grotevant, 2011).

To properly explain the positive impact of our study on GOC, it is important to understand their situation in Germany before the study took place. Our project was the first psychological investigation ever conducted on this population and many had lived their lives with little awareness of other GOC or opportunity to talk openly about their background. Suddenly researchers were present who were interested in their life story, consistently approached them with an interested and open attitude, and reliably responded to their concerns and questions. Those who desired it were also provided information in support of their search for their fathers. During the recruitment stage, they were given time to speak about their experiences, fears, and concerns on the phone or via email. After data analysis, results were shared with all involved via a newsletter that reported the main findings in laymen's terms. In addition, the entire study protocol was developed in collaboration with GOC and experts to ensure close alignment with their lived experiences. Support groups for GOC sired by American and French soldiers already existed before the 2013 study was conducted. As this was not the case for descendants of Red Army soldiers, the researchers initiated and assisted the formation of a network, who then held their inaugural meeting in Leipzig. At the time of the initial study, in 2013, various media outlets were addressing the topic of GOC simultaneously. There were interviews with researchers and GOC were asked for interviews. Reports on the subject were broadcast by radio and television. Those GOC, who had been nearly invisible with their backgrounds before and had previously only revealed themselves to people in their immediate social environment, if at all, now became socially visible. They spoke out for themselves, published autobiographies, connected with other GOC, and renewed their efforts to identify and locate their fathers. The visibility and the possibilities of exchange with people who grew up under similar, very specific developmental conditions was satisfying and reassuring for them. They describe experiencing a new sense of feeling accepted and complete. A subject that, for many, had never really found a place in their lives now suddenly became part of their identity and thereby had a self-empowering effect. The reactions participants shared after completing the study clearly show that the participants experienced acceptance and empowerment through participating in the study, effects which resulted from disclosing their personal truth, and receiving genuine interest and attention along with increased visibility and social acknowledgment.

As shown above, the positive experiences during as well as in the development in the wake of study participation contrast with the previous life reality of many GOC. In connection with the results of the initial study, which reported adverse experiences in childhood and adolescence, e.g., in the form of child abuse and maltreatment, as well as experiences of stigmatization and discrimination, the initial situation is reminiscent in aspects of feelings of isolation, of being unconnected, of not being heard and perceived, as described in the concepts of experienced injustice. There are various theories on this, but two seem to be closest to these experiences: testimonial injustice, as one aspect of epistemic injustice (Fricker, 2007), and ethical loneliness (Stauffer, 2015). Epistemic injustice focuses on discrimination, which refers to the systematic disadvantage of individuals in terms of their personal knowledge. “Testimonial injustice is present when negative stereotypes result in individuals being denied both credibility and epistemic capacity due to prejudice” (Kavemann et al., 2022, p. 140). The result may be a credibility deficit, which leads to the less powerful social groups having to fight to be heard (Fricker, 2007, p. 17). The concept of ethical loneliness has parallels to this. It is the condition of people who have been wronged by other people or political structures, but whose testimony is neither properly heard nor listened to by the surrounding world. This experience deepens the feeling of “ethical solitude” and the sense of homelessness and distrust in the world (Urquiza-Haas, 2018, p. 115). The introduced findings from both GOC studies suggest that these two concepts of experienced injustice could also be considered for GOC.

In addition to all these positive accounts regarding study participation, there were also negative statements regarding the initial study that should be mentioned here. During recruitment, for example, there were messages on the study answering machine advising against carrying out the study at all, saying that history should be put to rest. After study participation, there were participants who expressed disappointment because their hopes of finding their father through participation were not fulfilled, e.g.:

“If one wants to help the occupation children appropriate references must be published, so that this circle of persons finds out where they can turn. This is fundamentally lacking.” ID23

Others would have liked to see political pressure on the occupying powers to locate the fathers and/or open the archives for occupation children as a result of participation and were disappointed that this pressure has not yet been apparent, e.g.:

“The first 4 (from the previous question)5 are certainly fulfilled, but also because society is more open. I can't even begin to identify any political pressure!” ID2

One person said that, in addition to scientific findings, s/he would have liked to see practice-oriented recommendations:

“I had hoped that practice-oriented recommendations would have emerged in addition to scientific findings.” ID23

Some participants hinted that the results were incomplete and voiced reservation, e.g.:

“The transmission of the study results in full would be nice; The construction of an internet forum to exchange with and “find each other”, which could potentially have resulted from the study, is missing. What will change as a result of the study, will such minorities be heard from anymore?” ID29

Furthermore, there was disappointment about failed contact attempts to get in touch with other GOCs:

“My personal story has been placed in its historical context. I have learned (also through subsequent reading) that other children of the occupation have developed similar experiences, feelings, and behavior and thus I no longer feel so alone and isolated. Attempts to contact e.g. [GI trace coordinator for Germany/ Austria] have come to nothing: am I not a child of the occupation accepted as such, since I was born “only” in 1961? I would like to have contacts with other GI children! This expectation has not been met.” ID41

Conclusion

In line with numerous other studies reflecting on participation impact on populations with differing degrees of potential vulnerability, we have learned that by participating in a study that touches on personally meaningful topics, and learning about the results, experiencing oneself as part of a group, and thereby fulfilling the desire to belong and to be accepted, people have the opportunity to reflect in new ways about themselves, their life stories, and the larger context of their lives — even if not all expectations of study participation can be met. In addition, participants' testimonies clearly showed that the benefits reverberate over a period of several years. An impressive example of the reverberating process, which can also occur with a delay, is demonstrated by this email from a former study participant, which may be published here with kind permission:

“I have only now become aware of this in such a complex way. We children of the occupation are only a part of it. I am grateful that I was able to gain this knowledge, albeit late. And, dear Marie, I am grateful that back in 2013, in May, I received a call from you with the offer to participate in the study. That was the beginning of getting to know so many people with such different fates, all in the late search for self-discovery and their identity. I see the entire generation of war children [CBOW] with different eyes and different emotions than I have in my entire life so far, even though I have not lived “behind the moon.” I have always been politically open and have read a lot. But it has only been in the last few years that the topic of children born of war has been given space in research and in literature.” (ID18; October, 2019)

This statement and our findings clearly show that research can do much more than collect data and generate knowledge. It can be community-building, identity-strengthening, and ultimately also life-changing. The sometimes difficult path of researching hidden populations is worthwhile. For participants, beyond the significance of feeling heard the opportunity to be actively involved in the study process and have personal contact with research staff appears to further enhance the empowering effect of the whole experience. In addition to this, an attitude of fairness by researchers toward participants also appears to be beneficial — having the opportunity to give and take in respectful cooperation. For future studies on potentially vulnerable/sensitive and/or hidden populations, the following best practices can be recommended as gleaned from this work: (1) Cooperation of researchers and study subjects established through a participative research approach to ensure the instrument used is tailored to the specific circumstances of the study population; (2) Personal support of the study subjects during recruitment and (3) embedding the survey in a close-knit network of research staff, thereby contributing to much greater compliance; (4) Communication of the study results to the former participants in the form of a newsletter; (5) Facilitating networking among the participants — when applicable, especially if the study is the first of its kind and therefore the starting point for empowerment for a specific population; (6) Discussion of the study results with contemporary witnesses, in order to interpret them correctly/not to overlook any aspects; (7) Attitude of respect, openness, and appreciation toward study participants underlying the entire study process.

Limitations and further research

The results of the study presented should be viewed in light of the following limitations. First, self-selection bias is inherent to this study format. Less than half (44.52%) of the initial study participants took part in this follow-up survey, and even the participants of the initial study were self-selected. It remains unclear what impact study participation had on the non-responders. It could be that participation was very disappointing or stressful for them, or that more positive turns in their lives occurred, or that participation did not matter to them. However, if one compares the participants with the non-responders with respect to some core characteristics assessed in the initial study, there are no significant differences with regard to parameters such as age, gender, procreation background, army for which the biological father was deployed, experiences of stigma, experiences of child abuse, or current psychological distress [for more details please refer to Kaiser and Glaesmer (2022); supplement 4]. Another aspect concerns the completeness of the available data. Because we used a self-completion questionnaire, the participants were free to either answer the open-ended questions or not. Therefore, the aspects highlighted by the analysis do not reflect the opinions of all participants. These could be more positive or more negative or raise completely different topics that could not be covered by the analysis of the available data. Furthermore, the analysis of written answers must always be seen against the background of the wording of the questions. Aspects that emerged by chance, such as the motivation to participate to be part of an enlightenment movement, may well be more widespread among the respondents than they appear to be based on a single recorded statement, since there were no questions that specifically addressed this. Additionally, the analysis is based on information provided in writing in response to a questions posed in a self-completion format. Accordingly, there are several conceivable points at which misunderstandings could have occurred. On the one hand, it is possible that participants did not understand the questions in their entirety. On the other hand, it is possible that what was written, was understood differently by the authors in the analysis than what was originally intended by the participant. In contrast to an interview, an anonymous questionnaire does not offer the possibility to ask clarifying questions in the case of ambiguous statements.

Despite these limitations, the results of our study on the impact of research participation provide rich insights into beneficial effects of study participation and reasons why initial participation in the study might have elicited such positive feedback. Thus, researchers should be encouraged to continue research to give voices to potentially vulnerable/sensitive and/or hidden populations, enabling them to tell their story, and/or should not refrain from conducting studies on lived experiences on populations of higher age as well. Looking at the GOC in particular, their identity questions as well as the positive twists related to sense of belonging, social recognition, and self-esteem stand out. Therefore, future research should address experiences of injustice, as well as the aspect of disclosure in the lives of GOC, in order to gain deeper insight into the dynamics of these experiences. Interesting questions would be: Are the specific experiences of GOC reflected in the concepts of ethical loneliness or testimonial injustice? How did GOC experience the knowledge of their occupation child background? How did they cope with this knowledge? What impact did this knowledge have on their subsequent lives as well as on their evaluation of their previous lives?

Regardless of the benefits that study participation may have for individuals from a potentially vulnerable/sensitive and/or hidden population, it is important at this point to reiterate the importance of cultural sensitivity as an ethical principle in research. When conducting research it must be acknowledged that the social preconditions under which a candidate CBOW population currently lives dictate the level of access researchers have to them and influence CBOW's freedom to pursue their interests. Questions to be considered in advance are, for example, whether it might be shameful or even dangerous to identify as a CBOW, to network with other CBOW, or to cooperate with researchers? What social consequences might be associated with study participation? How are CBOW seen and recognized in their respective societies? Is there an intrinsic need to get in touch with other CBOW, or questions about one's identity/ origin?

Following are some examples of countries struggling to come to terms with their past. During the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) in the 1990s, about 20,000 to 50,000 girls, women, and men were exposed to conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV; e.g., Council of Europe: Parliamentary Assembly - Resolution 993, 1993). “Until now, there is little public acknowledgment of committed war crimes. The deliberate political denial will create great obstacles for peace, reconciliation and social stability in the region, because this way of dealing with the past not only denies memories and experiences of victims during the war, it also channels memories in the establishment of a main narrative, which creates the respective historical background of one ‘national truth'. {…} This social-political desire of silencing the past has an impact on women witnesses, facing re-traumatization in post-war Bosnian society” (Gödl, 2013, p. 9). While the psychological, physical, and social consequences of CSRV for the victims has been investigated during the last decade, “the issue of children as ‘secondary war victims' was still behind a wall of silence” (Gödl, 2013, p. 8). The issue was not addressed in the public debate on children's rights or in academia until the first psychological study was conducted in 2016 (Roupetz et al., 2021, p.127; Carpenter, 2010; Delić et al., 2017). Furthermore, in 2015, the former children of war (now young adults) have founded a network led by Ajna Jusić that was initiated by neuropsychiatrist Amra Delić (Forgotten Children of War Association, www.zdr.org.ba/). Members of the network see themselves as bridge builders to advance reconciliation in the country and to fight for equal rights and respect (www.trtworld.com; Chibow.org, 2019; Jusić, 2019; trtworld.com, 2019; Forgotten War Children Association, 2021).

The above-mentioned aspects to consider before planning research surely apply to other potentially vulnerable/sensitive and/or hidden populations in a similar way, as well as for reappraisal processes around sensitive issues in general. Poland provides a vivid example of this in its handling of the WWII issue. Although research has been conducted concerning the reappraisal of Poland's involvement in WWII, the Polish government seems eager to subdue any activity deviating from their view of history. According to Paveł Machcewicz, the former director of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdansk, the controversy around the museum depicts the convergence of history, remembrance, and politics. It is a two-fold controversy about WWII: “On the one hand, it concerns the museum, and on the other it is a controversy over the so-called Holocaust Act of 2018 as an attempt to block and punish testimony and research that might show Poland as complicit in the persecution and killing of Jews” (Golanska and Bittner, 2019). Obviously, nations just like individuals need time to be able to touch old wounds, clean them, and make them available for (public) healing and debate.

According to the Hamburg Arbeitsgemeinschaft Kriegsursachenforschung (AKUF; Hamburg working group on the causes of war) there were 29 wars/armed conflicts in 25 countries in 2020 (AKUF, 2020). Each of these countries is different in terms of the nature of their conflicts and how they deal with CBOW. It is now recognized that the living conditions of CBOW are specific and often precarious, and that this population is often highly distressed (e.g., Mochmann, 2008; Lee, 2017; Lee and Bartels, 2019a,b, p. 54; Roupetz et al., 2021, p. 130; Seto, 2013; Wagner et al., 2020). That said, we hope that future studies will have similar positive resonance with participants from CBOW populations in a greater variety of contexts and initiate positive developments in their lives—and we are eager to see future studies that will investigate this.

In summary, besides adding to the body of scientific knowledge, our study showed that participating in a study that addresses relevant and personal issues may have benefits on self-esteem, attachment and social acknowledgment for participants, which in turn may have the potential to initiate or resume reflection processes and enhance personal development. With a view to increasing life-expectancy, the study results additionally highlight the potential benefits of disclosure in later life, even regarding long-past (and long-lasting) problems. Benefits that may be meaningful for years to come. Therefore, more research on (older adult) potentially vulnerable/sensitive and/or hidden populations as well as older adults in general is therefore to be encouraged, provided it adheres to ethical guidelines, as it can make an important contribution not only to the understanding of the populations itself, but also to their lives.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty, Leipzig University (No. 415-12-17122012). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MK: person in charge of the initial study and the follow-up study presented here: responsible for preparation of questionnaire, recruitment of participants, conduction the study, data entry and cleaning, data analysis, and preparation of publication. HG: supervision of all study processes, co-analyst for qualitative data, supervision, and correction of publication. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The initial project was partially funded by a doctoral scholarship granted to MK by the State of Saxony. The University of Greifswald [BMBF grant number (FONE-100)] supported the start of the project with a starting grant for material.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and University of Leipzig within the program of Open Access Publishing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^GDR stands for German Democratic Republic.

2. ^GDR stands for German Democratic Republic.

3. ^Author's comment.

4. ^Author's comment.

5. ^Author's comment.

References

AKUF (2020). Zwei neue Kriege in diesem Jahr. Pressemitteilung der AKUF. Available online at: https://www.wiso.uni-hamburg.de/fachbereich-sowi/professuren/jakobeit/forschung/akuf/archiv/akuf-pressemitteilung-2020.pdf (accessed November 8, 2021).