- 1Department of Medical Psychology and Medical Sociology, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany

- 2Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, HELIOS Hanseklinikum Stralsund, Stralsund, Germany

- 3Department of Psychiatry, University Medicine Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany

Objective: Children Born of War (CBOW) are an international and timeless phenomenon that exists in every country involved in war or armed conflict. Nevertheless, little is known on a systematic level about those children, who are typically fathered by a foreign or enemy soldier and born to a local mother. In particular, the identity issues that CBOW often report have remained largely uninvestigated. In the current qualitative study we began filling this gap in the scientific literature by asking how CBOW construct their identity in self-descriptions.

Method: We utilized thematic content analysis of N = 122 German CBOWs' answers to an open-ended questionnaire item asking how they see themselves and their identity in the context of being a CBOW.

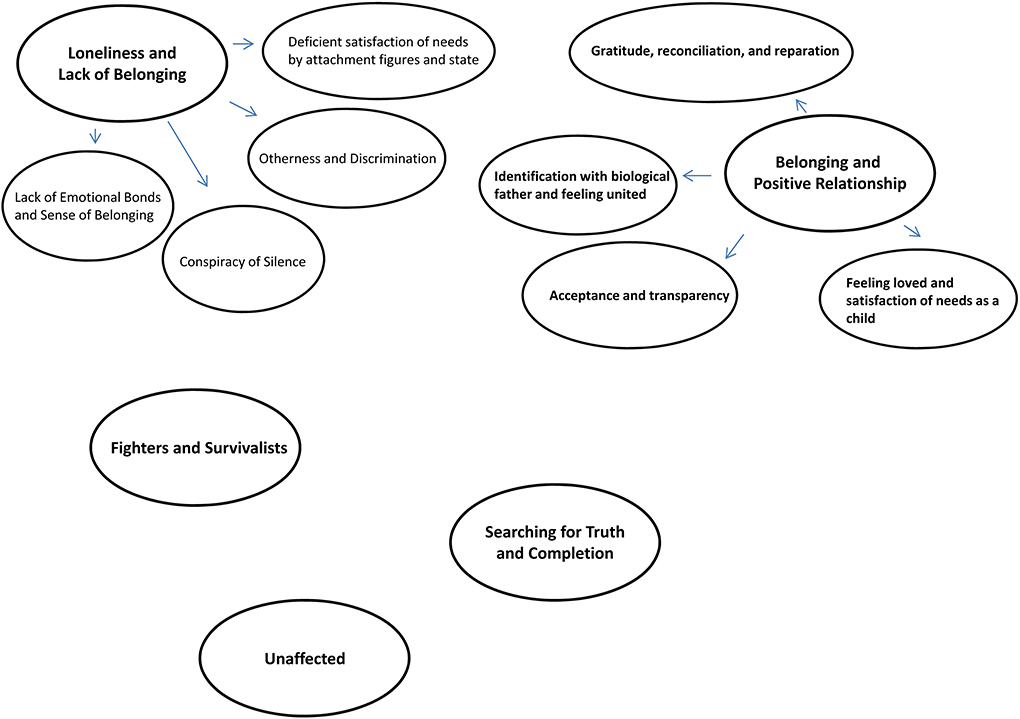

Results: We identified five key themes in CBOW' identity accounts. Loneliness and lack of belonging appeared as a paramount aspect of their self-descriptions next to narratives about belonging and positive relationship. On a less interpersonal basis, we found fighting and surviving and searching for truth and completion overarching aspects of their identities. There were also few accounts growing up unaffected by the fact of being born a CBOW. Although all themes portray different perspectives, they all (but the last one) clearly indicate the impeded circumstances under which CBOW had to grow up.

Conclusions: Integrating our findings with existing interdisciplinary literature regarding identity, we discuss implications for future research and clinical and political practice.

Introduction

In the presence and aftermath of armed conflict, there has always been contact between armed troops and civilians from superficial to intimate; and from these contacts children have been born. These children are so-called Children Born of War (CBOW)—typically born to local mothers and foreign soldier fathers. Their existence is a worldwide and timeless, yet widely ignored reality—to the detriment of those individuals and their communities.

German Occupation Children (GOC), of which we will report in this article, are a subgroup of the worldwide population of CBOW. An estimated number of 400.000 GOC were born at the end of World War II (WWII) and the following ten and more years to a German mother and were fathered by a member of one of the four allied military forces (from Great Britain, Soviet Union, France, and USA) that occupied Germany in 1945 (Stelzl-Marx and Satjukow, 2015). The relationships of their parents ranged from intimate love relationships to mutual businesslike relationships to systematic rapes. GOC share some experiences with all the other children, who were born and raised during that difficult post-war period. Some developmental conditions such as economic hardship, missing or emotionally absent fathers and hard-working single mothers were oftentimes similar irrespective of having a German father or a father belonging to foreign military. After all, about 25% of children had a father who did not return from the war (Radebold, 2008). Nevertheless, GOC have shown to represent a population with specific experiences. They are at a significantly higher risk to suffer from mental disorders such as Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), major depression or somatoform syndrome and show a higher prevalence of traumatic events (e.g., sexual abuse, neglect, and physical violence) and child maltreatment (Kaiser et al., 2015b; Glaesmer et al., 2017). They are also more likely—even decades later—to display insecure attachment in their current relationships (Kaiser et al., 2016). Furthermore, societal attitudes toward children who were born out of wedlock and their mothers were generally negative and this stigma was perpetuated by being a child born from a foreign soldier who had left the country and was still considered the enemy in many minds (Satjukow, 2011). A further and striking difference that might be at the core of many other of the above-mentioned problems was that their biological fathers were not only missing in person or being emotionally absent, but that there were no narratives about them, no stories or photos that portrayed a father that a child could relate to, i.e., identify with or distance itself from. No proof of existence. The vast majority of mothers and other family members remained silent about the biological father and asking questions about him was oftentimes an unspoken taboo irrespective of the background of their parents' relationship (Mitreuter et al., 2019). This conspiracy of silence has been reported as a widespread and omnipresent phenomenon in the context of CBOW (Ericsson and Ellingsen, 2005; Øland, 2005; Schmitz-Köster, 2005; Mochmann and Larsen, 2008; Stelzl-Marx, 2015; Koegeler-Abdi, 2021). The uncertainty about their biological origin is a persisting topic that challenges their wellbeing (Lee, 2017) and leaves many with an impaired sense of belonging (Ericsson and Ellingsen, 2005; Øland, 2005; Provost and Denov, 2020).

Identity issues are a widely reported problem amongst CBOW (e.g., Glaesmer et al., 2012) and at the same time remain a largely unresolved and diffuse topic. There has been some recent quantitative and descriptive research (Stelzl-Marx, 2015; Mitreuter et al., 2019) as well as reports from testimonies (Øland, 2005; Schmitz-Köster, 2005) that showed that almost all CBOW set out on an often impossible search for their biological fathers after they had been told the truth about their biological origin. Locating their fathers implied for many to feel more complete and at peace with themselves (Mitreuter et al., 2019). The results of this research can therefore serve as an indicator of how important finding and knowing their biological father is for an integrated identity and their wellbeing. However, the topic of identity issues in CBOW is still a scientifically new and complex phenomenon with no standardized and valid assessment instruments and there is still much to learn. It is for example unclear, how CBOW construct their identities and which core themes make up their identity descriptions. There has been a recent study by Schwartz (2020), who analyzed the construction of identity from a couple of narratives by German GOC, whose mothers were raped by Soviet soldiers at the end of WWII. The author found that the construction of a meaningful self and of an acceptable image of the father was crucial to the participants. However, her analysis was of a deductive nature and was guided by theories of trauma and definitions of resilience by LaCapra (2001). We were interested to see what themes we could extract following an inductive analysis and focusing on a bigger sample that included GOC from all types of parental relationships and all paternal ethnicities.

The current study

To gain a deeper insight into what identity issues mean for GOC, we utilized a qualitative and inductive approach to assessing and understanding potential identity issues. We therefore analyzed the answers to an open-ended questionnaire item asking GOC about how they would describe their identity in the context of being a CBOW. We were primarily interested in the underlying main themes that we could extract from their accounts to improve our understanding of the nature of their identity issues.

Procedure and participants

We collected a sample of GOC (N = 131) within the project “Occupation children: Identity development, stigma experience, and psychosocial consequences growing up as a German Occupation Child.” Participants were recruited via press releases, various national and international networks (e.g., www.childrenbornofwar.org; www.bowin.eu), and online-platforms for occupation children and children born of war in general (e.g., www.gitrace.org; www.coeurssansfrontiers.com). Within these calls, we invited potential participants to contact our research group to learn more about the project and to leave their contact details. Inclusion criteria were being born after 1940 to a German mother, being fathered by a soldier of one of the foreign occupation forces, and being able to understand and read the German language. Questionnaires, a study information sheet, and consent forms were subsequently sent to GOC via postal mail. One hundred eighty-four questionnaires were sent out and 164 were returned of which 9 had to be excluded because they did not fit the definition of “occupation children.” The participation rate was hence 88.6%, corrected for neutral drop-outs. We excluded another nine outliers with respect to age. Seventeen participants did not respond to the item subject to analysis or gave answers that we could not decipher leaving 131 valid cases (and a response rate of 89.73%), which were born between 1945 and 1966. Sixty-three percentage of the sample were female with a mean age of 63.4 (SD = 5.7) years. Seventy-one GOC have a US American father, 33 have a French (or French-Algerian/-Moroccan/-Corsican) father, 32 have a Soviet father, and 6 have a British father. Of those 131 GOC, 14 are not sure about their fathers' origin and another 4 do not know their father's origin. More information about the methodological approach, sample characteristics, and background of the original study are provided in Kaiser et al. (2015a). The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Department of the University of Leipzig.

Study design

CBOW are hidden populations, which are difficult to access and whose specific experiences are not accounted for by established instruments (Mochmann, 2013). For this reason, we acted two-fold to assess the topic identity within our larger questionnaire study: We adopted an existing questionnaire developed by Mochmann and Larsen (2008), who investigated children born of Wehrmacht soldiers in Norway and Denmark; And we applied a participatory approach to develop and amend questions and items that—amongst other topics—address aspects of identity (e.g., search for father, questions about origin, background of procreation, and feelings of shame, pride, and belonging) of GOC. The questionnaire, i.e., data corpus was mainly a tool intended to gain quantitative data, but for the current study, our data set consists of the answers to one open-ended question: “How do you see yourself when you think of your identity? Which specificities do you think result from being a German Occupation Child?” Participants were provided with one DINA-4 page to write down their answers and some extended this space onto the last empty pages of the questionnaire or added sheets of paper themselves. The answers ranged from 5 words to 1,714 words.

Data analysis

Taking a constructionist and inductive approach and aiming at a rich description of the whole data set, i.e., all accounts to our posed question, the analytical process was comprised of five overlapping iterative phases in accordance with Braun and Clarke (2006) outline for thematic analysis. We conducted a reflexive thematic analysis according to Braun and Clarke (2021). First, we familiarized ourselves with the data by reading and re-reading the accounts. Second, we generated initial codes from the text by summarizing and deconstructing it into identifiable units of meaning. The same unit of text could be included in more than one category or code. Although we had some knowledge about identity theories prior and at the time of the analysis (e.g., narrative identity theory McAdams and McLean, 2013), we tried to approach the data with an open mindset and in an inductive manner in an attempt to generate codes and themes from the text that might not have been represented by existing theories. Thus, in the next phase we identified themes and overarching categories that would organize a body of codes. We then went back and forth between potential themes to scrutinize them for consistency and representativeness of their codes and to collate them where possible into a higher-order theme.

Interpretation and validity

The current study availed itself of an interpretative and constructionist perspective. We perceived our findings as one of many possible interpretations of the data (Lincoln et al., 2011). Utilizing an interpretative phenomenological approach, we were aiming at identifying what the participants themselves were revealing in their accounts, in order to give voice to their authentic testimony regarding their specific experiences. Thus, throughout the analysis, we maintained a hermeneutics of faith (Josselson, 2004) and accepted the participants' accounts at face value. We evaluated our conceptualizations and interpretations by using the following validity criteria: (a) Sources of interpretation were exclusively actual pieces of data and existing theories only served as a tool for explanation. (b) Interpretations that were considered valid may not contradict each other in any way. Finally, all accounts were compared to gain a holistic understanding in line with the aim of our study and our research question.

Results

The analysis led to the identification of five recurring themes (see Figure 1) indicating how heterogeneous the detailed experiences of growing up as a GOC are. However, the thickness of some themes over others clearly demonstrates the overall hardship and in particular loneliness and isolation, from which the majority of GOC had suffered when growing up in post WW II Germany. In the following section, we shall elaborate on each theme as it unfolds to further understand how these experiences relate to each other. All quotes were translated from German by the first author and confirmed as loyal to the original German wording by the second author.

“No one who cared for me my whole life”—loneliness and lack of belonging

From previous reports and testimonies in which many CBOW describe their suffering from being discriminated against or being the unloved and odd one out within their family or wider social environment, we expected that we would see related topics within our data. However, we were surprised by the many ways and the frequency, in which topics referring to deep (existential) loneliness were reported. The identified theme of “Loneliness and Lack of Belonging” was by far the thickest and most substantial of all. We saw this theme conveyed through a multitude of subthemes, with the most dominant one speaking of a lack of belonging or lack of emotional bonds and attachment figures.

Lack of emotional bonds and sense of belonging

Agathe and Christine described how their life-long sense of not belonging within their families, but also in a wide social context have influenced their self-esteem and wellbeing:

“I never felt like I belonged within my family. I never belonged anywhere. I still have this feeling today, at work, with friends—even if it is not true (anymore). I have suffered from a strong loss of trust because everyone lied to me throughout my whole childhood. […] I was in analytical therapy for many years and could reappraise and incorporate a lot through transference of relationship with my therapist. This has helped me, but ‘the wound of the unloved one' remains” (ID 47, father member of the US American army).

“Today, I see myself as a content woman. But I had to work for it my whole life and went through very difficult times […] because I was always on the edge, I never belonged. […]. [During childhood] my mother visited me every 2 months. I adored her but she was emotionally unattainable for me and stayed this way until her death in 2007. I had no self-esteem, never voiced any needs. I lived merely passively. I was a good student, but secondary school was out of question. When I think back, my childhood appears gray, joyless, and filled with fear” (ID 34, father member of the US American army).

Although it is not typical for GOC to have grown up without their mothers according to our data, the sense of detachment and alienation from the family is widely reported. A lack of parental tenderness and love was doubtlessly also conditioned by post-wartime and the shortage of time and existential threat that it posed to many parents who had to work hard to survive and supply for their children. But what GOC describe has a deep level of existential loneliness to it:

“Today, I feel uprooted with respect to my identity, but also free. The price of that freedom is the lack of a sense of belonging in a profound way. I rarely tie myself to people and if I do it is temporary. Because of the knowledge that my biological father was a soldier in the US-army I have mixed feelings about this country. It provides a repelling attraction” (ID 144, father member of the US American army).

The feeling of being uprooted or in free fall, not being held by anyone and not being able to relate to anyone was something we often saw in the data and shows how isolated GOC felt growing up. This uprooting also seems to be associated with the attachment issues in later life that have been reported by Kaiser et al. (2016). Feeling a “repelling attraction” toward the father, or the home country of the father showcases the inner conflict and disruption with themselves and their identity. It seems to reflect their constant search for belonging but at the same time fear of not being able to belong to the father after all and maybe in this connection losing hope of ever being able to really belong.

Conspiracy of silence

Another highly pervasive subtheme emerging from the identity descriptions is the topic of silence. The taboo surrounding their origin and the truth about their conception is something widely reported that at the same time is experienced as extremely aversive and harmful for a healthy identity development and the development of trustful relationships within and later also outside the family:

“The whole kinship of mother has kept silent!! All my life I haven't had anyone I could relate to, no father, no siblings. Mother still does not want anything to do with me, apparently because I remind her of 1952. She cannot handle it, but also does not want to talk about it. I would still like to search my father but mother won't tell me his name” (ID 30, father member of the French army).

“The family put a heavy cloak of silence over my origin. If relatives were upset with me, they were dropping allusions: ‘You are not who you think you are”' (ID 40, father member of the Soviet Army).

Hans and Richard were kept in the dark. Other GOC also report of a dark spot, a dark hole that cannot be filled because their origin was treated a taboo in their social environments. If ones origin is unspeakable and taboo, these GOC might have felt like a taboo themselves and something to be ashamed of. But also keeping silent themselves was experienced as aversive and isolating and turning toward more openly speaking about one's own past and biological origin seemed to be associated with relief and healing:

“In the past: intense shame, fear of being discovered and bullied subsequently, because people spoke disparagingly about other illegitimate children. […] As a consequence: great silence, hushing up—I forged my life story to avoid becoming ‘noted which led to long periods of depression. Today I can speak openly about who I am. I know who I am and I tell it to everyone” (ID 8, father member of the Soviet Army).

Otherness and discrimination

GOC tend to suffer from multiple stigmata often leading them to feel devalued, rejected and isolated. In post-war Germany, for example, it was still heavily frowned upon to be born out of wedlock, which was the case for almost all GOC born after WWII, such as Peter describes:

“I have always felt like a 2nd class human, because I was in addition [to being a child of a foreign soldier] born out of wedlock. That also made me an outcast” (ID 12, father member of the British army).

In addition, they were born as the children of foreign soldiers, who still were considered the occupying enemies in many people's minds. Beyond all that, many had visible features that made them look different from their peers, which oftentimes subjected them to racist treatment like John reports:

“As a child, people often asked me to show my teeth or asked whether they could touch on my hair. Total strangers asked me that. In kindergarten, I was supposed to play burned bread […]. Very often people told me they didn't have a problem with People of Colour. On my graduation ball no girl wanted to dance with me although I was at least the most handsome (just joking). No matter the occasion; searching for a job, going to a club, getting to know girls etc.—I always had an oppressive feeling due to my skin colour. Sometimes I even felt strange to myself” (ID 151, father member of the US American army).

This kind of othering and racist treatment thwarted their need for belonging and isolated them not only from others, but also led to alienation from themselves.

Deficient satisfaction of needs by attachment figures and state

Another subtheme contributing to GOC' loneliness and lack of belonging was what we called “Deficient satisfaction of needs by attachment figures and state”:

“We [occupation children] never looked for connection or contact amongst each other. We never really had the chance to, which I greatly regret. There were no contact persons we could talk to about our woes and sorrows. No one ever talked to me personally; everything was decided over my head. We were without rights and left with nothing. Outcasts” (ID 61, father member of the US American army).

There were no advocates for their needs and rights and no cohesion and solidarity amongst occupation children even if in some cases they were known to each other or suspected others to be just like them. In GOC life stories, we also found a high prevalence of them being sexually abused as children (Mitreuter, 2021). It seems as if the isolation and a consequential vulnerability of GOC was recognized and exploited by the perpetrators. The following quote about a mother who did not take any action against the sexual abuse of her son is exemplary for the lacking protection that many GOC experienced, be it by primary caregivers or the state:

“Back where I lived as a child, there was a catholic congregation. Four brethren and one Father administered one courtyard. The Father had a habit of touching and “playing” with some of our penises. My mother took no action against it, because she worked in the monastery's household and would have lost her job. Another mother reported the case and the Father was transferred as a result” (ID 44, father member of the Soviet Army).

“Mother gave everything she could”—belonging and positive relationship

In contrast to the previous theme, there were some accounts with a clear emphasis on belonging and positive relationship, although the impedimental circumstances under which most CBOW grew up often shone through nonetheless. Belonging and relationship comprised subthemes such as “feeling loved and satisfaction of needs as a child,” “acceptance and transparency,” “identification with biological father and feeling united,” and “gratitude, reconciliation, and reparation”.

Feeling loved and satisfaction of needs as a child

One of the strongest indicators that we saw connected to a feeling of belonging and positive relationship was the feeling of being loved and that fundamental needs were satisfied as a child. We found this to be a major theme in CBOW's identity descriptions:

“My grandmother mourned two sons, who did not return from the Eastern front. Despite this, she loved me and she was my closest ally until her death” (ID 18, father member of the Soviet army).

“My mother did everything for my happy childhood. I'm sure she suffered very much herself. There were people, who tried to take advantage of this: The Soviet intelligence service wanted to take me so that they did not have to pay any more alimony. Interrogations, recruitment for espionage etc. Therefore, my mother declared my father unknown“(ID 58, father member of the Soviet army).

Gustav, the son of a Soviet soldier, reports being loved by his grandmother until her death even though both of her sons had died at the hands of Soviet soldiers. Many accounts suggest that it often seemed to suffice for an overall positive account to have had one person, who provided a reliably loving relationship for them to feel wanted and loved. This person was mostly either the mother or grandmother. These reports tell of protection like above where a mother protected and therefore concealed the origin of her child at the risk of being discovered and punished. They tell of continuous loving relationship free from spite and violence and support to develop their own abilities and talents (within financial possibility).

Acceptance and transparency

Acceptance and transparency means that the truth about their biological origin and their conception was known and accepted at least by the mother and/or grandparents, but also by the step-father if applicable and wider social environment such as teachers and classmates. Transparency refers to GOC growing up knowing all they could potentially know from their mothers or other primary caregivers about their conception and true biological origin and that there was no taboo to speak of their biological fathers or to ask questions. These accounts were rare, but the following is an example:

“I've always known everything but before I turned 25 I still didn't really talk about my origin to anyone outside the family, simply because I was never asked. I lived in an intact and loving family. In 1981, I visited my father and his family in Kiev together with my husband, my two sons, and my half-brother […]. We were lovingly welcomed and taken in with much leniency and acceptance” (ID 14, father member of the Soviet army).

Identification with biological father and feeling united

Many GOC report of always having felt wrong within their own family or different from all the other family members and rejected by society. As displayed in the following quote, it seemed to be of great importance to GOCs' feeling of self-worth and healthy identity to see their fathers in a positive light and to feel connected to them or the culture of their home countries:

“Personally, I don't see myself as an occupation child, but the child of a LIBERATOR! […] I see myself as a survivalist; freethinker, fighter and I like to confront prejudiced people. I can be proud and I am proud of my origin and let everyone know about it” (ID 63, father member of the US American army).

Some report being relieved not to be all German, but for example half-French or half-American. It seems like the need to belong is so strong that many feel connected to someone like their biological father or to the culture of a country even if they do not know them at all and have not seen them or been there even once in their lives.

Few CBOW have had the chance to locate or even meet their biological fathers and if so, getting to know or meeting them in person was not always experienced as positive (see Mitreuter et al., 2019). However, given finding and meeting him or his remaining family members was overall positively experienced, it often had the chance to become a deeply positive turning point in their lives:

“[…] My youngest daughter found [my half-brother] on Facebook. Ever since, we all frequently chat and mail each other, we exchange photos back and forth. We all immediately became Facebook friends. It is wonderful—and both families have the same marvelous feeling that we are finally a family. I cannot describe the warm-heartedness that comes across via the Facebook pages. It is as if I had longed for it my whole life. I received photographs of my father and the—for me most important information—that he had wanted to return back to my mother in Germany and get in touch with her. However, he was stopped by the authorities for reasons that we all know now—but, had it worked, I now wouldn't have this astounding brother in Israel” (ID 19, father member of the US American army).

“Daddy will come to visit me! […] Praise the Lord for showing me my father. We love each other very much and have been very affectionate with each other. My joy is immense. Here in France [where I moved to], many GI-Babies search for their father in the US. I have found my own roots. That heals all wounds. My self-esteem is restored (ID 62, father member of the US American army).

Uniting with the biological father or members of his family in case of his decease like it was the case for these two GOC provided them not only with joy, but a deep sense of—maybe even long-needed—belonging and connection.

Gratitude, reconciliation, and reparation

We found that expressions of gratitude and mentioning of reconciliation and reparation in CBOW' identity descriptions were strongly linked to a feeling of belonging and the reporting of positive and meaningful relationship.

“I particularly admire my mother, how she mastered life, how much she put everyone's needs before her own, had to live a very modest life (disability pensioner after a head surgery) and how she paved my way into school and vocation. She supported me and made the impossible possible” (ID 80, father member of the French army).

This GOC experienced it as “the impossible” to have grown up as a happy child and to receive the full love and support from a resilient mother. A mother who herself had to suffer much being despised by her own father and part of the society surrounding her and being scorned for having had intimate contact to a foreign soldier and to have his child. Through this love and support this GOC found a way into a life well-integrated into society. This is definitely a life course that is rarely told amongst GOC. More common are the reports of a difficult childhood and youth that took a turn to the better due to recovery, healing, with reconciliation, and reparation:

“On the whole, I can say that I had more positive than negative experiences. And the most negative things, I experienced during my youth, approximately […] until my daughter was born! From that moment on, I had a goal: To lead my children onto the right path from the beginning—based on my personal experiences. And this worked out wonderfully” (ID 33, father member of the US American army).

This GOC tells of experiencing difficulties during childhood and youth with many people “still living in the 3rd Reich mentally” (ID 33, father member of the US American army) and discriminating against her for being a person of color. Her self-description speaks of a sense of identity and meaning through being a successful mother by bringing up happy children. Becoming the creator of a new and intact family appears to be an important act of reparation and healing for those who managed to do so.

“Against all negative prognoses”—fighters and survivalists

In contrast to the first two themes, “Fighters and Survivalists” comprises statements, which pronounce GOCs' own inner achievement and agency and focus more on the self rather than a relationship dimension. Common ground was the hardship, which they had been exposed to in clear contrast to the “Unaffected” reports following later.

“I am a fighter. I discovered abilities within me, which I never thought I had and I've grown more confident” (ID 5, father member of the US American army).

“I see myself as a survivor. Despite all tribulations, violence, and danger I was exposed to, I did not end up in a psychiatric hospital and never clashed with the law. I could adjust to every new situation in my life and assert myself” (ID 4, father member of the Soviet army).

These accounts convey the sense of being a survivor vs. the sense of being a victim or scapegoat, which is more commonly found within the “Loneliness and Lack of Belonging” theme. They convey defiance and pride in mastering the difficult circumstances on their own and show some degree of resilience. There was often a clear development from negative to positive circumstances and outcomes, in particular based on own accomplishment:

“I felt only 50% complete. […] Since I managed to prove my identity using DNA analysis and found the American part of my genetics, I am 100% complete and like to tell it to others. I finally started believing in myself and finally have self-esteem. I only really started being alive in 2012” (ID 29, father member of the US American army).

Like above, the fighting aspect was often accentuated by expressions such as “others were proven wrong,” “having proven it to others,” “I made it,” “I worked hard for my happiness,” “I fought through,” “against all odds,” and “against all negative prognoses”.

“Aching to see father only once”—searching for truth and completion

The theme of “Searching for Truth and Completion” is somewhat related to the theme of “Loneliness und Lack of Belonging,” but we also considered it original and in part independent from it. Searching did not necessarily evolve from feelings of loneliness and lack of belonging, but often also from a seemingly deep and existentially driven curiosity to know more about one's second biological half and thereby to trace and prolong one's own biography into the past via the line of the own biological parents.

“I was searching for my identity for a long time, sometimes desperately. As a child, I always felt incomplete—something was missing. I couldn't accept my step-father” (ID 16, father member of the French army).

“I am an addict. Was my father one, too? From the maternal side, there are no connections to addiction. What did my father do for a living? According to unconfirmed reports, he was supposed to be working as a pharmacist. Was he successful? How was he? Honorary offices? Success? Many questions that are waiting for an answer to this day” (ID 121, father member of the French army).

The need to find out more about their unknown other biological half seems to be a universal need as almost all GOC indicated a wish to find or at least learn more about their fathers. It seems almost as if knowing the father did not only offer identification, but almost a kind of verification of the self. Finding their fathers seems to be linked to achieving a sense of an integrated identity and a positive life resolution for some GOC. And the opposite seems to hold for those like Gerd, who cannot mirror themselves in their fathers and hence do not receive that kind of confirmation of themselves:

“I wish I had met my biological father or at least knew who he was. Until this day, I can neither find peace within myself nor the peace to deal with not knowing” (ID 37, father member of the US American army).

However, there were also accounts, in which we found searching and longing to rather revolve around a sense of “Loneliness and Lack of Belonging” like in Gustav's account:

“Relationships and friendships have always fallen apart after some time. There is no continuation in my life. I feel like I am always searching, restless… (I move approximately every 5 years for example)” (ID 35, father member of the US American army).

“Growing up sheltered and unsuspectingly”—unaffected

Some accounts entailed several co-existing themes. The “Unaffected” shared descriptions of “Belonging and Positive Relationship,” but there was no “despite being a GOC” in their words, because sometimes they were unknowing of the fact but unsuspectingly at the same time. These participants were very few, but they all reported their identity not having been affected at all by being a GOC. Others grew up not knowing about being a GOC and at the same time not feeling any different to the others in their surroundings like Hans' account suggests:

“Due to learning about the particularity [of being a GOC] quite late, I grew up unselfconsciously—from my point of view. […] Additionally, the conditions of the former GDR [German Democratic Republic] accommodated me. […] I met the requirements: good grades, good conduct, stemming from humble homes” (ID 9, father member of the Soviet army).

Other “Unaffected” GOC pronounced that difficulties in their lives did not originate from being born a GOC, but merely from the economic hardship of that time if they had experienced any difficulties at all. Others described being popular and well-adjusted from childhood on just like Theresa:

“As a child, my advantage was that I looked quite cute. I was always treated nicely by everyone. I was invited to other children's birthday parties, even from families which were out of our “reach” such as the daughter of the clockmaker foreman, both daughters of the car workshop owner, a medical officer of health…maybe (how I learned later) it was because my mother had insinuated that she had been raped. Maybe the town's reaction was an act of pity” (ID 9, father member of the Soviet army).

Even though Theresa suspects being treated differently, in fact more favorably, due to potentially being born from the rape of a Soviet soldier, she still seemed to have lived a sheltered life as a child.

Discussion

In the context of every armed conflict, children are born, who are fathered by the foreign or enemy soldiers and born to local mothers. These children tend to grow up under hindering circumstances both in society and within their families and often report suffering from identity issues amongst others. To better understand what their identity issues mean and how they construct their identities, this study explored the open-ended answers of (N = 131) German Occupation Children to a question about how they saw themselves and their identity in the context of being an occupation child.

“Loneliness and Lack of Belonging” appeared to be a most relevant theme when the occupation children thought about their own identity. We found that a conspiracy of silence around their biological origin and an often reported lack of emotional bonds to primary caregivers as well as a feeling of not belonging anywhere greatly contributed to this loneliness. Many GOC reported being discriminated against and being made outsiders, often when they visibly differed from the majority society, which we saw connected to feelings of loneliness as well. These two topics of “conspiracy of silence” and “discrimination and stigmatization” have been widely found in other reports and research on CBOW (Ericsson and Ellingsen, 2005; Øland, 2005; Mochmann and Larsen, 2008; Stelzl-Marx, 2015; Provost and Denov, 2020; Koegeler-Abdi, 2021). Last, they reported not only a lack of positive and stable emotional bonds but also a deficient satisfaction of their needs as children and adolescents by their primary caregivers but also the state, which seemed to fail in its responsibility to provide for and protect them as a vulnerable minority as well as supporting them to locate their fathers.

As a counter pole, there were also reports that conveyed a “Feeling of Belonging and Positive Relationship,” in which GOC felt accepted or loved by at least one primary caregiver (often a grandmother if not biological mother). Feeling accepted seemed to go in hand with their family being honest and transparent about their biological origin. How important it is for children to be told the truth about their biological origin has already been widely investigated and found in the context of child adoption and so-called donor offspring studies (see for example Freeman and Golombok, 2012; Golombok et al., 2013; Freeman, 2015; Ilioi et al., 2017). There is one recent study by Koegeler-Abdi (2021), who conducted a qualitative analysis of testimonies and interviews with Danish CBOW and attempted to theorize the functions of secrecy within families. The author found that secrecy was not only a root cause for identity crises amongst CBOW, but also a potential resource for resilience. According to Koegeler-Abdi, secrets worked like storage vessels with a protective function, which could keep a secret until it was ready and safe to be let out and processed. Some of the CBOW in her study showed understanding and appreciation of their mothers' secrecy. We found this very interesting, especially as it is something we could not replicate for our data set. There was no single instance, in which family secrecy was reported to have felt fair or helpful. It would be interesting to analyze in the future under which conditions secrecy might feel protective and productive (for instance within a stable family with loving relationships) and in which it did not. The two rather oppositional themes of loneliness on one and belonging on the other side did not necessarily exclude one another within an individual account as there were some reporting being lonely as a child, adolescent or young adult but healing and finding reconciliation later in life when for example they built their own loving family, underwent successful psychotherapy or united with their father. However, these two themes do have in common that they are opposite poles on a continuum that is of social nature. The following two themes, as different as they are, are rather rooted in a deeply personal domain:

“Fighters and Survivalists” comprises statements focusing on personal achievement and growth despite the hardship rather than focusing on the interpersonal domain. Reports revolved around personal strength and mastery that helped these individuals to gain control over their own lives “against all odds.” This theme could potentially be associated to the concept of resilience (Herrman et al., 2011), post-traumatic growth (Linley and Joseph, 2004) or the concept of agency (McAdams and McLean, 2013), a concept within narrative identity theory that shows the degree to which participants are able to assert control over their own lives or influence others in their environment, which is often shown through acts of self-mastery, empowerment, achievement or status.

“Searching for Truth and Completion” represented the seemingly fundamental need to know about ones biological origins. Of particular interest seem to be similarities in personality, appearance, and talents (Mitreuter et al., 2019). A preliminary analysis of life story interviews (Mitreuter, 2021) found how closely linked finding their fathers is to achieving a sense of an integrated identity and a positive life resolution for many GOC. Interestingly, it often seemed to be more relevant to simply know about the father, who he was and where or whether he still lived than being in actual contact with him (Mitreuter et al., 2019). This finding is in line with our argument that the theme “Searching for Truth and Completion” has a deeply personal and existential meaning rather than a social one. That it is more about the self than the connectedness. This fact is also in accordance with studies of McAdams and McLean (2013), who found that a gap in the continuity of the biography is threatening an integrated identity and hence an individual's wellbeing.

As a fifth theme we identified accounts, in which identity descriptions seemed unaffected by the fact that they were GOC often because they were unaware of the fact but had no reason to suspect any different either. These accounts were few and often, but not always involved statements about belonging and positive relationships, which is why we considered it a separate theme in our analysis.

Strengths, limitations, and further research

Our study does not only substantiate the current state of the field and offer more weight due to its systematic approach and sample size, but it also adds new analytical insights as even more widely found topics such as a conspiracy of silence or a pervasive discrimination and stigmatization of CBOW and their mothers had not yet been put into a broader context of identity. This study contributed to a deeper insight into the plurality of identity aspects specifically relevant to CBOW and generated a first systematic overview of these aspects, their interrelatedness, and potential connection with psychological theories on trauma or narrative identity.

Despite the benefits and importance of the current study, it is also limited in several ways. First and foremost, it is not a representative study in the target group as CBOW qualify as hidden populations. We reached out for participants publicly, who then reacted if they were interested. The sample is hence self-selective and the entire population is unknown, which makes it impossible to conduct a representative study. Second, our data is of cross-sectional nature and the participants answered the item in retrospect, which makes our data subject to potential bias of retrospective self-report. The data is only a reflection of the current status when interviewed. We acknowledge that identity and identity construction are dynamic processes that would highly benefit from a life-course perspective. Although we could gather some information on within-individual development of identity over time, these measurements still remained cross-sectional, which clearly poses a limitation in understanding a time sensitive and dynamic phenomenon such as identity. Third, even if CBOW worldwide share many specific experiences, our data might not be generalizable to other CBOW populations due to specificities of each population such as culture, the type of war or the degree of hostilities between the parties for example. Other studies might yield other results, which is why further studies in other CBOW populations are much needed. Future research could focus more on systematic analyses and possibly standardization of instruments to allow for cross-cultural comparisons. Fourth, at the same time, we feel that there is still need for open and qualitative research in these populations, especially if a phenomenon as complex and scientifically new as identity in CBOW is being investigated. The given written material within the quantitative questionnaires was in many cases short or warranted more context as they were given. So in some cases our analyses stayed descriptive whereas a life story interview for example would have allowed for more in-depth interpretation of a person's account. We asked for identity “in the context of being a child born of war.” This means that some other aspects or areas of identity could have been neglected and underreported. We hence suggest the analysis of life story interviews for a more complete understanding of CBOW identity.

Implications for clinical and political practice

Despite the limitations, our study can serve as a cornerstone in improving our understanding of CBOW and their unique biographies together with previous and future research. It can inform political practice as such that it is vital for children born of war to be able to access their biological family members and to get support for example in forms of networks who help bring them together with family members but also other CBOW (like some already exist in Germany or France) to foster a feeling of belonging and shared lived experiences. A prerequisite for this is that the existence of CBOW must enter the public discourses internationally in a de-stigmatizing way. We plead for an international children's right to know about their biological origins and to facilitate them locating their biological parents. Considering the deleterious ramifications associated with loneliness (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010), we advocate that clinicians be aware of its existence in addition to and irrespective of mental health symptoms.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committees of Leipzig University (415-12-17122012). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SM designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. HG and MK collected the data and supervised analyzing the data and writing the manuscript. PK assisted in collecting the data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No 642571 (Network website: www.chibow.org) and from the State of Saxony (Grant No. WE-V-G-07-2-0612). The University of Greifswald [BMBF Grant No. (FONE-100)] supported the start of the project with a starting grant for material.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 18, 328–352. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Ericsson, K., and Ellingsen, D. (2005). “Life stories of Norwegian war children,” in Children of World War II. The Hidden Enemy Legacy, eds K. Ericsson and E. Simonsen (Oxford: Berg), 93–112.

Freeman, T. (2015). Gamete donation, information sharing and the best interests of the child: An overview of the psychosocial evidence. Monash Bioeth. Rev. 33, 45–63. doi: 10.1007/s40592-015-0018-y

Freeman, T., and Golombok, S. (2012). Donor insemination: a follow-up study of disclosure decisions, family relationships and child adjustment at adolescence. Reprod. Biomed. Online 25, 193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.03.009

Glaesmer, H., Kaiser, M., Freyberger, H. J., Brähler, E., and Kuwert, P. (2012). Die Kinder des Zweiten Weltkrieges in Deutschland-Ein Rahmenmodell für die psychosoziale Forschung. Trauma Gewalt Forschung Und Praxisfelder 6, 319–328.

Glaesmer, H., Kuwert, P., Braehler, E., and Kaiser, M. (2017). Childhood maltreatment in children born of occupation after WWII in Germany and its association with mental disorders. Int. Psychogeriatr. 29, 1147–1156. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217000369

Golombok, S., Blake, L., Casey, P., Roman, G., and Jadva, V. (2013). Children born through reproductive donation: a longitudinal study of psychological adjustment. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 54, 653–660. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12015

Hawkley, L. C., and Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 40, 218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

Herrman, H., Stewart, D. E., Diaz-Granados, N., Berger, E. L., Jackson, B., and Yuen, T. (2011). What is resilience? Can. J. Psychiatry 56, 258–265. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600504

Ilioi, E., Blake, L., Jadva, V., Roman, G., and Golombok, S. (2017). The role of age of disclosure of biological origins in the psychological wellbeing of adolescents conceived by reproductive donation: a longitudinal study from age 1 to age 14. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry All. Discipl. 58, 315–324. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12667

Josselson, R. (2004). The hermeneutics of faith and the hermeneutics of suspicion. Narrat. Inq. 14, 1–28. doi: 10.1075/ni.14.1.01jos

Kaiser, M., Kuwert, P., Braehler, E., and Glaesmer, H. (2015b). Depression, somatization, and posttraumatic stress disorder in children born of occupation after world war II in comparison with a general population. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 203, 742–748. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000361

Kaiser, M., Kuwert, P., Braehler, E., and Glaesmer, H. (2016). Long-term effects on adult attachment in German occupation children born after world war II in comparison with a birth-cohort-matched representative sample of the German general population. Aging Ment. Health 22, 197–207. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1247430

Kaiser, M., Kuwert, P., and Glaesmer, H. (2015a). Growing up as an occupation child of world war II in Germany: rationale and methods of a study on German occupation children [aufwachsen als besatzungskind des zweiten weltkrieges in deutschland - hintergrunde und vorgehen einer befragung deutscher besatzungskinder]. Zeitschrift Fur Psychosomat. Med. Psychother. 61, 191–205. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2015.61.2.191

Koegeler-Abdi, M. (2021). Family secrecy: experiences of danish german children born of war, 1940–2019. J. Fam. Hist. 46, 62–76. doi: 10.1177/0363199020967234

LaCapra, D. (2001). “Interview for Yad Vashem (June 9, 1998),” in Writing History, Writing Trauma (Baltimore, MD: JHU Press), 142–180.

Lincoln, Y. S., Lynham, S. A., and Guba, E. G. (2011). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited. Sage Handb. Qual. Res. 4, 97–128.

Linley, P. A., and Joseph, S. (2004). Positive change following trauma and adversity: a review. J. Traum. Stress 17, 11–21. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e

McAdams, D. P., and McLean, K. C. (2013). Narrative identity. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 22, 233–238. doi: 10.1177/0963721413475622

Mitreuter, S. (2021). “Questions of identity in German occupation children born after world war II: approaching a complex phenomenon with mixed-method analyses,” in Children Born of War eds S. Lee, H. Glaesmaer, and B. Stelzl-Marx (New York, NY: Routledge), 153–165. doi: 10.4324/9780429199851-8-9

Mitreuter, S., Kaiser, M., Roupetz, S., Stelzl-Marx, B., Kuwert, P., and Glaesmer, H. (2019). Questions of identity in children born of war—embarking on a search for the unknown soldier father. J. Child Fam. Stud. 28, 3220–3229. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01501-w

Mochmann, I. C. (2013). “Ethical considerations in doing research on hidden populations-the case of children born of war,” in Second International Multidisciplinary Conference “Children and War: Past and Present” (Salzburg).

Mochmann, I. C., and Larsen, S. U. (2008). Children born of war”: the life course of children fathered by german soldiers in Norway and Denmark during WWII—some empirical results. Hist. Soc. Res. 33, 347–363. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20762268

Øland, A. (2005). “Silences, public and private,” in Children of World War II. The Hidden Legacy, 53–70.

Provost, R., and Denov, M. (2020). From violence to life: children born of war and constructions of victimhood. N. Y. Univ. J. Int. Law Poli. 53, 70. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3475496

Radebold, H. (2008). “Kriegsbedingte Kindheiten und Jugendzeit. Teil 2: väterliche abwesenheit und ihre auswirkungen auf individuelle entwicklung, identität und elternschaft,” in Transgenerationale Weitergabe kriegsbelasteter Kindheiten: Interdisziplinäre Studien zur Nachhaltigkeit historischer Erfahrungen über Vier Generationen, eds H. Radebold, W. Bohleber, and J. Zinnecker (Beltz Juventa), 175–182.

Satjukow, S. (2011). “Besatzungskinder” Nachkommen deutscher frauen und alliierter soldaten seit 1945. Gesch. Gesell. 37, 559–591. doi: 10.13109/gege.2011.37.4.559

Schmitz-Köster, D. (2005). “A topic for life: children of german lebensborn homes,” in Children of World War II: The Hidden Enemy Legacy, 213–228.

Schwartz, A. (2020). Trauma, resilience, and narrative constructions of identity in Germans born of wartime rape. German Stud. Rev. 43, 311–329. doi: 10.1353/gsr.2020.0046

Stelzl-Marx, B. (2015). Soviet children of occupation in Austria: the historical, political, and social background and its consequences. Euro. Rev. Hist. Rev. Euro. D'hist. 22, 277–291. doi: 10.1080/13507486.2015.1008416

Keywords: Children Born of War, hidden populations, vulnerable populations, conflict, identity, thematic analysis

Citation: Mitreuter S, Glaesmer H, Kuwert P and Kaiser M (2022) Loneliness and lack of belonging as paramount theme in identity descriptions of Children Born of War. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:851298. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.851298

Received: 09 January 2022; Accepted: 11 August 2022;

Published: 13 September 2022.

Edited by:

Vinicius Rodrigues Vieira, Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado, BrazilReviewed by:

Martina Koegeler-Abdi, Lund University, SwedenBogdan Voicu, Romanian Academy, Romania

Renata Summa, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Copyright © 2022 Mitreuter, Glaesmer, Kuwert and Kaiser. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Saskia Mitreuter, U2Fza2lhLk1pdHJldXRlckBtZWRpemluLnVuaS1sZWlwemlnLmRl

Saskia Mitreuter

Saskia Mitreuter Heide Glaesmer

Heide Glaesmer Philipp Kuwert2,3

Philipp Kuwert2,3 Marie Kaiser

Marie Kaiser