- Department of Government and Politics, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland

All political parties want candidates that will win elections but electability is an elusive trait and how it is understood, and pursued varies greatly. Political parties have formal rules, and informal practices and preferences, for selecting candidates and these tend to be dynamic, changing from election to election as parties review their performance and respond to changes in the political and legal environment. Generally, the last thirty years has witnessed a drift toward greater internal party democracy as party members have been given more extensive roles in important decisions such as selecting candidates for election. Ireland is an interesting case study that on the surface embraced internal party democracy (IPD) at an early point. All the major parties have empowered party members to vote for candidates at district level selection conventions. But closer inspection reveals that decision making remains highly qualified with party elites retaining decisive influence over the criteria which structure decisions by party members. Multi-seat constituencies, party finance rules and more recently the introduction of a legally binding gender quota mean that internal party democracy is far more constrained than the widespread adoption of one member, one vote and constituency level selection conventions might suggest. However, even the modest changes in the power balance in selection has contributed to an evolving profile of candidates at Irish general elections.

Introduction

Internationally, there has been a drift toward greater internal party democracy over the last thirty years. Political parties faced with declining and aging memberships sought new methods of involving their members in policy formulation and decision making (Bille, 2001; Cross and Katz, 2013; Coller et al., 2018). Empowering party members in the selection of candidates for election (Rahat and Hazan, 2001) and in the process of choosing the party leader (Cross et al., 2016) became common reforms. More recently, political parties from the far left and far right have embraced radical member based organizational structures in recent waves of party formation and reinvention (Vittori, 2022).

The onward march of internal party democracy (IPD) is part reality, part illusion among political parties in the Republic of Ireland (hereafter Ireland). Parties enthusiastically involved members in decision making from the 1990s. The Green Party and Fine Gael were early innovators and diffusion to all the established parties followed within two decades. But the democratization reforms are undermined by widely used powers that party elites retain to set the parameters of selection decisions. Most democratic political parties hold some central candidate selection and de-selection powers but in the Irish case, these powers are used frequently and motivated by an incentive structure that includes the electoral system, party finance rules, and legally binding gender quotas.

Party members have limited scope for independent decision making and when they do attempt innovation, they often find their decisions controversial and resisted (Weeks, 2008; Reidy, 2016).

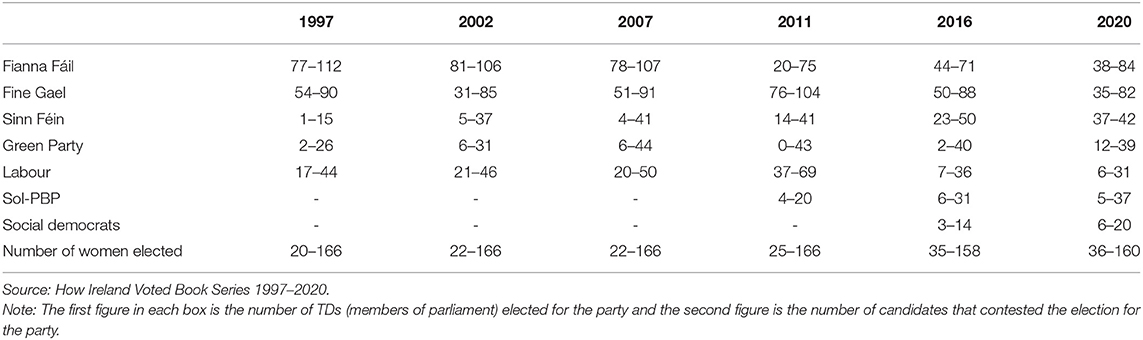

Electoral competition in Ireland tended to follow a stable pattern for much of the twentieth century as can be seen from the election results presented in Table 1. Ireland uses Proportional Representation by the Single Transferable Vote (PR-STV) as its electoral system. With its multi-seat constituencies, party elites in larger parties always recruit more than one candidate per constituency in the hope of winning multiple seats. Candidate selection procedures are thus complex; and geography, candidate age and gender, and party succession planning are among the criteria that feature in decision making.

Changing patterns of electoral competition coincided, and no doubt contributed to internal party reforms in the established parties, many enhancing IPD (see Barnea and Rahat, 2007). And this is also a period in which the legal and institutional political landscape began to evolve. Successive political corruption scandals led to major revisions in the laws governing party financing (Byrne, 2013). The economic crisis after 2008 also generated interest in the operation of the political system and led to further important changes relating to party finance, this time directly connected to the representation of women. A candidate gender quota linked state funding of political parties to improved female candidate selection and created a financial imperative for parties to ensure that party tickets had a minimum of 30% women candidates. Candidate gender quotas were first used at the 2016 general election and the quota will increase to 40 percent in any election after 2023. Parties receive state funding in two forms and the funding linked to the gender quota accounts for slightly more than half of the state funds that parties receive. Any party that does not meet the gender quota loses 50% of their potential funding under this allocation. The low levels of female candidacy across most parties meant party elites became significantly more interventionist in candidate selection processes from 2016 onwards.

The number of candidates seeking election was fairly stable until 2011, oscillating in the high 400s. The 2008 economic crisis led to an EU and IMF bailout in 2010 which brought about a sharp increase in interest in governance and a corresponding increase in candidate numbers. Five hundred and sixty six candidates contested the 2011 election. Candidacy has trended downwards since 2011 but it remains above the norm set from 1992 to 2007. Table 1 provides an overview of candidate patterns, and also the number of candidates elected for each party. There are some important trends in the table. Political fragmentation has increased and the numbers of candidates being put forward by parties has changed noticeably. Parties of the center left (Labour, Sinn Féin, Green Party, Social Democrats) have been increasing their candidate numbers while parties of the centre right (Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael) are clearly contracting. Combined, centre right parties selected 202 candidates in 1997 and this had dropped to 166 in 2020. In contrast, parties of the centre left selected just 85 candidates in 1997 and this had risen to 169 in 2020.

Independents (non-party) candidates are an unusual feature of Irish elections, they are not considered in this analysis as they do not go through a selection process.

This article will proceed with its analysis organized around two research questions presented in section two. Thereafter section three presents a short note on the data sources used and section four provides an overview of formal party rules and practices to demonstrate that there was a notable diffusion of democratic candidate selection methods in the main political parties and to set the scene for the research. Section 5 uses interviews and party data from elections in the last decade to highlight the changing balance of internal party democracy between members and elites and to concretely demonstrate the limits of the democratization reforms highlighting the limiting institutional factors at work and unpacking the overlapping and conflicting dynamics. The analysis proceeds to demonstrate that despite the limits of the democratization reforms, patterns of candidate selection have evolved and candidate profile data from 19970 to 2020 are analyzed.

Analytical Framework

All political parties want candidates that can win elections. But the method to deliver the most electable candidates and what makes a candidate electable remains the subject of heated debate, discussion and experimentation within political parties and political science.

Beginning with the process of candidate selection, Rahat and Hazan (2001) presented a four dimensional classification system for analyzing selection methods which included rules governing standing for a party, who gets to make the candidate selection decisions, at what level of political organization and finally how are the candidates formally selected (appointment or voting). Candidacy rights determine who can be chosen to present as a candidate for selection by a political party. For example must the candidate be a party member, are there restrictions related to residency within a state. The selectorate is the name given to the group of people who make the selection decision. Including all party members, or indeed all voters, placed a party on the inclusive end of the Rahat and Hazan scale while rules which rested decision making with party elites or the party leader placed the party on the exclusive end. The third consideration of the model was the level at which selection choices were made. The centralized end of the scale involved decision making at the national level within the party while decentralized decisions were taken by members at the district or constituency level. And the final dimension looked at whether decision making was by appointment or voting. This framework informs the presentation of IPD in Irish parties in section four.

The question of who gets chosen as a candidate and why has generated one of the most rich and comprehensive literatures, especially in relation to gendered aspects of political recruitment. This review highlights research on the impact of specific institutional factors on IPD, the electoral system, gender quotas and party finance before also looking at how the revealed preferences of selectors can be used to infer insights in the absence of available data.

In relation to electoral systems, Marsh (1981) elaborated on the complexities presented when an electoral system requires parties to run more than one candidate in a constituency. How this practice is managed and evolves as party support changes is essential to understanding the management of candidate selection. Hazan and Voerman (2006) have argued although electoral systems may not be “causal” to the understanding of outcomes of selection processes, they do play a role. They highlighted candidate centered electoral systems as especially important.

Rahat et al. (2008) posit that there may be an inverse relationship between inclusive selection procedures and the representativeness of the candidates chosen for election (see also Rahat, 2009). This is especially important to note as increased IPD may be making it more difficult for women and minority candidates to emerge. Wauters and Pilet (2015) expand on this point in relation to the election of women leaders arguing that direct membership votes require appeals to large audiences and often greater financial resources to campaign, points which both mitigate against the success of women leadership candidates. They point out that these arguments can also be expanded to those with lower socioeconomic backgrounds. This point is picked up in the examination of candidate backgrounds in the penultimate section. Bjarnegård and Kenny (2016) also highlight the decentralized aspect of selection processes and argue that local influence over selection contributes to the continued over selection of male candidates.

The field consensus points toward enhanced IPD creating obstacles to the selection of women candidates and potentially impeding other forms of diversity. Many countries have sought to counter low levels of female candidacy with different forms of gender quotas which have become widespread in the last three decades (Hughes et al., 2019). Support for quotas tends to be variable across groups but overall tends to be low (Keenan and McElroy, 2017). Gender quotas interact with internal candidate selection procedures in that they are directional toward the selection of women in most cases (Bjarnegård and Kenny, 2015). Thus, they can limit the freedom of party selectorates. This is especially the case with quota structures that contain financial penalties for failure. If a political party loses resources when it does not meet a quota requirement, strong incentives are created for the party to adopt internal candidate selection procedures that ensure quota targets are met. Across the democratic world, political parties have become heavily reliant on state financing as personal and corporate donations have been heavily regulated.

Party finance rules have notable implications for impact on their strategic priorities of parties. Cross and Katz (2013, p. 3) unpack a variety of these interacting dynamics in their discussion of how IPD is “constrained by state imposed party laws.” The analysis in this article is particularly concerned with the ways in which party funding laws and the legislative gender quota interact with IPD in Irish political parties.

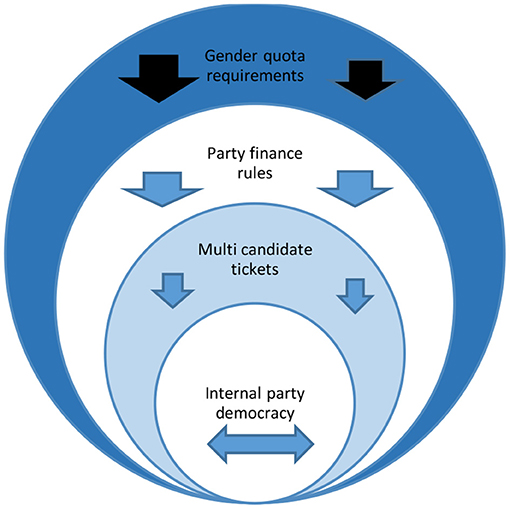

Drawing these threads together leads to a conceptualization of overlapping dynamics where parties internally favor and enact reforms to enhance IPD but these reforms exist within a wider institutional and legislative framework which often constrains or pushes back against IPD (see Figure 1).

How these interacting forces impact on the motivations and the decisions made by selectors is a much more open question. Gallagher and Marsh (1988) described candidate selection as the “secret garden” of politics. While some research over the intervening period has revealed how power is distributed within parties, how this distribution has evolved and the consequences for parties remains an important knowledge gap. Strøm (2005) unpacks the dynamics of internal decision making in parties and highlights the information asymmetries at play when parties delegate decisions on candidate selection to party members who may not be fully informed on strategic objectives or indeed immediate requirements. The motivations, priorities and knowledge profiles of party selectors remain substantially obscure. Bochel and Denver (1983) revealed the interplay of selector and candidate ideology, and conceptions of electability. More recently Vandeleene et al. (2016) noted a strong preference among selectors in Belgian political parties for experienced candidates. It is complex to survey party members most especially because parties rarely want to share their inner deliberations with competitors, so the few studies which have been conducted provide valuable insights which can be pursued more widely, although imperfectly, using other forms of data. Thus, the experience, gender and professional profiles of candidates are often observed closely to understand indirectly the preferences of selectors and how they might be changing. The effect of greater IPD (Galligan, 1999) and the impact of major political crises and events (Kakepaki et al., 2018) on the preferences of selectors can be tracked on one level through observing the outcomes of their decisions in the form of the socioeconomic and demographic profiles of candidates and this is done in the penultimate section.

Bringing the strands in the literature together leads to two central questions guiding this Irish case study:

RQ1: How have institutional factors and legislative changes impacted internal party democracy in Irish political parties?

RQ2: What have been the consequences of these changes for the representativeness of candidates at general elections?

Method and Data

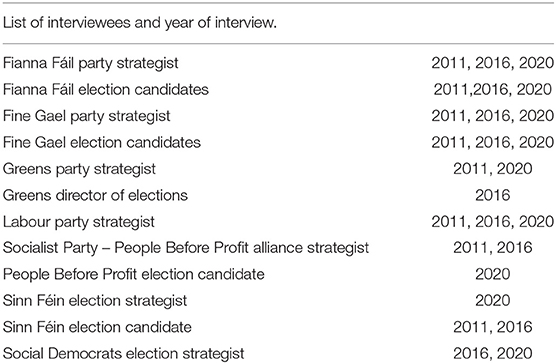

The research draws on three data sources. In the first instance, IPD in Irish parties is described using party constitutions and rule books. Details of each document are included in the reference list. Interviews with party strategists, candidates and party members are used to interrogate the countervailing democratizing-centralizing dynamics at play. The interview data were collected after the general elections in 2011, 2016, and 2020. Interviews were not recorded but extensive contemporaneous notes from each were taken. Interviewees are not identified given the sensitivity of the strategic party decisions discussed in the research but a list with relevant party labels is included in Appendix 1. Evidence from these two sets of sources are used to address RQ1.

To evaluate the changing profile of candidates selected to contest elections in Ireland (RQ2), data on candidate characteristics are presented. An average of 500 candidates contested each of the elections and the gender, occupation and family link in politics information are mostly available for each candidate from the five preceding general elections. The occupation classification used is drawn from the How Ireland Voted book series and the data were collected initially as part of the research for the book series. The move to one member, one vote at selection conventions started in the 1990s and with some interruptions, data from elections over the period 1997–2020 are presented and any change in the profile of candidates could be expected to be evident over the elections covered in the research.

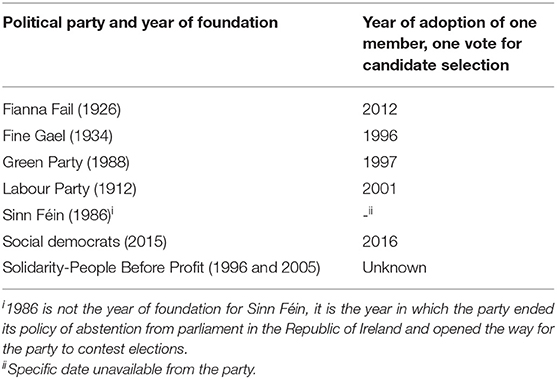

Table 2 provides a list of parties included in the analysis with the year in which they adopted one member, one vote as their method of candidate selection. The year of party formation is included in brackets for information.

Internal Democratization

In common with parties across the world, Irish political parties began enfranchising their members more extensively in candidate selection, leader selection, and policy development from the 1990s. There was notable diffusion of democratization patterns among the parties thereafter. Up to this point, selection decisions were usually taken at constituency level but with a restricted franchise operating, the branch delegate model being the most common approach. Usually each branch of the party within the constituency nominated a number of delegates to vote at the selection convention. Most parties had rules about the duration of existence for braches, the number of delegates usually varied from two to four and they were generally drawn from the officer board of the branch.

Fine Gael and the Green Party were the first of the established parties to introduce the system of one member, one vote at selection conventions. Fine Gael initiated the change in 1996 and used the process for its selections at the 1997 general election (Galligan, 1999) while the Green Party codified the procedure in its 1997 constitution (Bolleyer, 2010; Green Party Constitution). The Labour Party adopted one member, one vote in 2001 but it did not use the process for general elections until 2007 (see Galligan, 1999). Of the mainstream, established parties, Fianna Fáil retained the delegate model the longest. Traditional in outlook and in operation, the party engaged in widespread internal reform at its 2012 national party conference. The impetus for reform came from a catastrophic election defeat in 2011 when the party lost almost three quarters of its members of parliament and its long dominant position in politics. In addition to instituting one member, one vote for candidate selection, the 2012 party conference also voted to give members an important role in the election of the party leader (Fianna Fáil, 2016; Reidy, 2016).

Among the more recent party additions to the electoral competition arena, internal democratic procedures have also been widely adopted. Sinn Féin is a difficult party to study and is generally reticent about engaging with political science research. The party did not contest general elections until the late 1980s and reports that it used one member, one vote thereafter (correspondence with party strategist). The Social Democrats were founded by three TDs (MPs) in 2015. The party used informal procedures to select candidates at its first general election in February 2016 but one member, one vote was formally instituted in the party's first constitution which was adopted in late 2016 (Social Democrats Constitution, 2021). Solidarity-People Before Profit is a fluid electoral alliance of two main groups which emerged from the Socialist Party and the Socialist Workers Party, respectively. Their cooperation works at a number of levels but they retain separate organizational structures and procedures for determining their electoral and candidate strategies. Both sides of the alliance use one member, one vote at constituency level selection conventions. While the parties have rulebooks governing procedures, interviews with party candidates confirmed that selection decisions are rarely contested and an informal approach is taken to decision making (PBP candidate interview, 2020).

Irish political parties apply a common threshold requiring candidates to become members of the party and some also require candidates to sign a party pledge (Fianna Fáil) with policy compatibility assessed by interview in a small number (Labour, Social Democrats, Sinn Féin). For party selectors, membership is a criterion for exercising voting rights and again there is some variation in the duration of membership required (from 6 months to 2 years).

As parties reformed and codified their electoral procedures, many also formally adopted PR-STV as the electoral system for selecting candidates at conventions. While this had been in use by some parties (Fine Gael, Labour) preceding the 1990s, it was not used by all in part because of the small numbers of voters and decisions. Research investigating candidate decision making noted that parties reported increased attendance at selection conventions following moves toward wider enfranchisement (Galligan, 1999; Reidy, 2016).

Following the Rahat and Hazan (2001) classification system, Irish political parties generally have quite inclusive candidacy requirements and the parties are mostly inclusive and decentralized in their approaches to their selectorates and the use of constituency level candidate selection conventions. Parties also have clear voting and ratification rules. These findings on the surface suggests a strong level of internal party democracy. But closer investigation reveals that decision making is highly qualified with party elites retaining decisive influence over the rules which structure decisions by party members. All of the political parties retained decision making functions for party elites during their reform phases. Political parties had, and have, procedures in place to determine the overall electoral strategy of the party and concretely in the area of candidate selection, each party has a system in place for adding or de-selecting candidates (see party constitutions). The addition of candidates is a power that all parties use, some with regularity, while de-selection is rarely employed (Reidy, 2021). Parties also have procedures to ratify the full slate of candidates. Thus, while there is evidence of drift toward empowerment of party members in selection decision making, it is qualified and next, the role of institutional factors in shaping the constrained empowerment of members is evaluated in more detail.

Countervailing Selection Dynamics

This section is concerned with the countervailing incentives emanating from the electoral rules and institutions that act against the drift toward internal party democracy. The introduction and analytical framework identified three important factors shaping the power centralizing incentives of party elites in Ireland: the electoral system, gender quotas and party finance rules. In this part of the analysis, each of these is examined, and interviews with party elites and candidates from elections in 2011, 2016, and 2020 are used to highlight the dynamics at play.

Electoral System

The use of PR-STV with its multi-seat constituencies means that medium to large parties can potentially win more than one seat in a constituency and thus need to engage in strategic assessments of how many candidates they should run. That the electoral system also allows voters to choose among both parties and candidates is a further complicating feature and leads to parties taking account of a suite of local factors including geography, succession planning, incumbency, and political factions. These aspects have been a perennial feature of party decisions on candidate numbers (Marsh, 1981; Weeks, 2008). Parties may lose seats through selecting too many candidates and may also lose seats by not having enough candidates in the race (Gallagher, 1980). Thus, party calculations are complex and furthermore evolve as the election approaches and opinion poll numbers crystallize levels of party support. Changes close to the election rarely involve members and party rules facilitate elite-led decisions as rapid decision making is often required.

Typically Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, the two largest parties, deployed multi candidate tickets at elections. As party support levels fluctuated up and down, Labour and Sinn Féin also ran more than one candidate in a small number of constituencies. Decisions on candidate numbers are in the first instance taken by the electoral strategy committees in all parties. Interviews with party strategists confirm a similar approach to decisions with reviews of opinion poll patterns, performance at the preceding election, available candidates, especially incumbents and geography all featuring as the party determines how many candidates should contest each constituency. Party strategists often report direct engagement with regional and local branch structures to secure the views of local party activists and ensure that they have a direct input into national strategy (Interviews with Fine Gael strategists, 2016, 2020; Interviews with Fianna Fáil strategists 2016, 2020). The final decision, known as the candidate directive, is communicated to the local constituency organization and critically, structures the decision to be made by members.

The unusual features of the electoral system combined with localist tendencies in politics mean that party elites have a strong incentive to carefully configure the parameters of constituency level selection conventions. Furthermore, on rare occasions, the strategy teams may have already decided on candidates that they will add to the ticket irrespective of the decisions taken locally. Party mergers and the defection of candidates from other parties have occasionally provided clear examples of candidates added by parties centrally where it was clearly expected that they would not have been successful in coming through a local selection convention.

In Ireland's localist political culture, voters and party selectors, favor candidates from their constituency and successive waves of the Irish election study have also demonstrated that a track record of constituency work is valued (Marsh et al., 2008; Farrell et al., 2018). Thus, the geographic location of candidates within constituencies is an important criterion, this has often led party elites to further qualify the candidate directive with additional geographic requirements, obliging that the selectors choose candidates from specific areas. Since the introduction of gender quotas, discussed later, gender has also become an additional qualifying criterion.

To illustrate the complexity produced by multi-seat constituencies, two cases are worth highlighting, over selection by Fianna Fáil in 2011 and under selection by Sinn Féin in 2020. Fianna Fáil experienced a dramatic collapse in support in the years preceding the 2011 general election. The party leader changed just weeks before the election, there was a sharp increase in retirements of incumbents and party tickets were in flux until the close of nominations. Party elites struggled to manage candidate numbers. The party had selected a large number of candidates at conventions but as poll numbers declined, it became evident that the party had far too many candidates on its ticket. Although retirements close to the election helped reduce numbers to 75 candidates, this was still largely judged to have been many more than would normally be run by a party polling at <20 percent (Gallagher, 2021). Interviews with party strategists confirmed that the party worked to reduce candidate numbers by encouraging some candidates to move constituencies and others to stand down. However, in the midst of an electoral meltdown, although party elites retained official power to de-select candidates, in practice it could not do so as this would only have contributed to the febrile political atmosphere (Interview with Fianna Fáil strategist, 2011). Ultimately the party won just 17.4 percent of the vote, down from 41.6 percent in 2007. In candidate and seat terms, just 19 of the 75 candidates that contested the election were elected, a success rate of 25 percent. While in 2007, 77 of the party's 106 candidates were elected, a success rate of 75 percent (Gallagher, 2008, 2011, see also Table 1). Over selection was certainly a component of the party's woes in 2011, it had too many candidates for its reduced circumstances.

In contrast, Sinn Féin entered the 2020 elections with too few candidates to maximize returns on its rapidly rising poll numbers. Party strategists discussed how a poor performance in the local and European Parliament elections and weak poll figures encouraged the party to take a conservative approach to election preparations (Interview with Sinn Féin strategist, 2020). The party did not contest one constituency, selected two candidates in just four constituencies and had one in all other constituencies. Many of the selection decisions had been taken up to 2 years before the election. Indicative of internal concerns about a possible poor performance, in some cases candidates that stood down before the election were not replaced (Reidy, 2021). This was a serious strategic error. Polling numbers tracked upwards as election day approached and the party found itself with too few candidates in the race. Eighty eight percent of Sinn Féin candidates were elected in 2020 (37 of 42 candidates). This contrasts with the party's success rate of 46 percent in the preceding election in 2016 (Gallagher, 2016).

The Fianna Fáil (2011) and Sinn Féin (2020) cases provide insights into extreme examples of how parties can both over-select and under-select candidates. Fluctuating poll numbers when combined with a highly proportionate electoral system mean that decisions on the number of candidates to select can be complex and subject to sharp misalignment especially if party support levels vary as the election approaches. This dynamic provides a strong incentive for party elites to retain important decision levers in relation to overall candidate numbers.

Gender Quotas

The slow pace of improvement in the gender profile of parliamentarians became a notable part of a debate on political reform in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crash. While the gender profile of candidates was mentioned by party strategists in interviews at the 2011 election, it was clearly not an immediate priority shaping decisions. Acknowledged as generally important by the center right Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, they did little in concrete terms to change the overall balance in their candidate slates. After the selection conventions were complete, Fianna Fáil added one woman and Fine Gael two women to their overall candidate tickets, marginal increases on already quite low numbers of women candidates in 2011 (see Buckley and McGing, 2011). The left leaning parties were more proactive and Labour, Sinn Féin and the Green Party had local branches seek out potential female candidates and had been emphasizing gender balance in internal decisions for some years (Buckley and McGing, 2011; Reidy, 2011; see also Labour Party Constitution, 2017; Social Democrats Constitution, 2021).

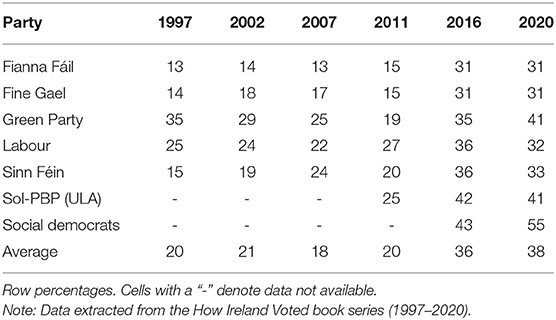

By 2016, the selection context on gender had been transformed with the introduction of legislative gender quotas. The financial penalties accruing if a party failed to meet the 30% threshold of candidates from both genders (essentially a female gender quota) were such that all parties actively deployed strategies to improve gender balance. Table 5 provides an overview of the evolving gender profile of candidates. The parties began by taking direct action at the 2014 local elections when there was a notable emphasis on selecting female candidates. Parties on the left of the spectrum were considerably more successful in achieving their own gender targets with Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael failing to meet even their own internal criteria (see Buckley and McGing, 2011). As the 2016 election approached, parties deployed more structured interventions with training courses and dedicated campaign supports for women offered widely. However, these softer approaches were insufficient especially for the larger center right duo which had sizable numbers of incumbent male MPs and longstanding candidates. Thus, direct intervention by elites in selection decisions increased notably for the 2016 selection cycle.

Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil issued five gender directives each to selection conventions for the 2016 general election. These varied in specifics but all required that at least one woman be selected. Some of the gender directives proved very controversial and the legislation was challenged in the higher courts in the run up to the election. In addition to using their powers to structure decisions at constituency selection conventions, parties also directly added candidates to the party ticket. Fifty six percent of the candidates added by Fianna Fáil were women, sixty percent of Fine Gael additions were women (Buckley et al., 2016; Reidy, 2016). While party strategists in Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael refuted the assertion that the sharp increase in the addition of women candidates by party elites close to the election was a purely expedient exercise in ensuring that they were compliant with the gender quota legislation, they did agree that a more interventionist approach to candidate selection had been required throughout the selection cycle as a result of the gender quota laws. Ultimately both parties met the quota barely (Fianna Fáil at 31%; Fine Gael at 30.7%).

The left leaning smaller parties had stronger gender balance among their incumbents going into the election and this partly explains their somewhat smoother selection seasons. Nevertheless, the parties were not complacent about reaching the target and many wanted to exceed the target as a matter of political intent. The Labour Party required gender balance in all constituencies where it ran more than one candidate and additionally prioritized selection of women candidates. Sinn Féin had a “gender intervention process” devised in advance of the election and this resulted in one gender directive at a selection convention and two thirds of its additions (of a total of three) were women. The Social Democrats had three incumbents entering the 2016 election and two of these were women. This strong gender profile was replicated in the wider ticket of candidates and the party ultimately fielded a slate with 43% women candidates. The Green Party reported few problems with the gender quota but in interviews stressed that it was kept under review throughout the election cycle (Interview with director elections, 2016). The Solidarity-People Before Profit Alliance tends to have a high turnover of candidates at each election and both constituent parties performed well on gender balance with 42 percent women candidates (see Buckley et al., 2016 and Reidy, 2016 for a longer discussion).

By the time candidate selections were initiated for the 2020 general election, the discourse around gender balance had become more firmly embedded in politics. The 2016 general election exit poll also demonstrated a high level of public support for the measure which party strategists reported as helpful in advancing discussions especially at the 2019 local and European Parliament elections. Although this point contrasts with a view that generally there is low support among publics for legal positive action measures (Coffé and Reiser, 2021). Fianna Fáil strategists noted that there was considerably less direct resistance to requirements for gender balance on party tickets and Fine Gael strategists also reported the need for less direct intervention. Nevertheless, neither party advanced its candidate gender balance at the election selecting 31 percent and 30.5 percent female candidates, respectively. For the Labour Party and Sinn Féin, the picture was one of deterioration with both parties running lower percentages of women candidates than in 2016. These figures are important because the gender quota is due to rise to 40 percent at elections after 2023 and thus party elites are likely to need to resort to 2016 style interventions as the election approaches, providing gender directives and disproportionately adding women candidates to tickets.

The evidence suggests that the gender quota provided a direct impetus for party elites to become more interventionist in selection decision making in 2016. Selectorates were required to pick female candidates in some instances while in others party elites bypassed selectorates and made direct candidate decisions. Direct interventions reduced in 2020 but were still a notable feature of decision making. Thus, while party selectors play a part in the selection of women candidates, these decisions are often directly structured, and supplemented by party elites. The financial penalties faced by parties that do not meet the quota requirements are sufficiently onerous that all parties prioritize gender in the candidate selection process, sometimes at the expense of electability.

Party Finance Rules

The large parties in the system are affected by decisions on the number of candidates to run in each constituency and with larger numbers of incumbent male candidates, they also struggle more with reaching gender quota requirements. Smaller parties however are more directly influenced by party finance laws in their candidate selection decision making. The legal framework governing the funding of political parties was updated significantly in 1997. Parties became eligible for funding in proportion to the number of first preference votes they received subject to meeting a two percent minimum threshold. Individual and corporate donations to political parties and candidates are heavily restricted and parties are largely dependent on the state for funding their activities. As a result, there is a financial imperative for small parties to reach the two percent funding threshold.

All parties seek to maximize the number of votes they get but many smaller parties highlighted the two percent threshold as being an explicit motivating factor in shaping selection strategies (Interviews with Green Party strategists, 2011, 2016; Social Democrats, 2016; Solidarity-People Before Profit, 2020). The Green Party has run a candidate in every constituency since 2007 to offer a choice of voting Green to all voters (Weeks, 2008). But following a severe decline in 2011 and losing its state funding, meeting the two percent threshold became an important priority at the 2016 general election and was cited in interviews by both the director of elections and candidates interviewed for this research as another contributing reason why the party ran a candidate in constituencies where they had no expectations of featuring in the final competition. The party needed every vote to ensure it met the threshold, which it did comfortably in the end. Having been set up in 2015, the Social Democrats also prioritized the funding threshold at the 2016 election. The party was questioned about running paper candidates in some constituencies purely for funding purposes, a point it denied however having just formed, funding was undoubtedly a priority to build a national infrastructure. Finally the far left leaning Solidarity-People Before Profit alliance are rarely willing to discuss their internal operations with researchers but in one interview in 2020, the funding threshold was highlighted by a candidate who indicated that it was an important incentive which led to candidates being selected in some constituencies where the parties did not have existing branch infrastructures.

The funding threshold requirement thus leads smaller political parties to select candidates in areas where they often do not have a critical mass of supporters and party branch infrastructures. The selection decisions are sometimes not made by members on the ground, rather by party elites that tend to seek out possible candidates that are willing to be flag bearers for their parties. Oftentimes these candidates engage in only the most minimal campaigning. Thus, the funding laws lead to additional incentives that bolster elite decision making and bypasses members.

In combination, the electoral system, gender quotas and party finance laws provide important incentives for political parties to intervene and carefully craft candidate selection decisions. The electoral system is a long standing feature of politics but party funding and gender quota laws were being introduced in the same decades that parties were also engaging in IPD reforms and worked to constrain IPD by creating critical financial imperatives that parties had to meet. Following Strøm (2005) information asymmetry also helps to understand why elites are required to intervene. They have a full national overview of the slate of party candidates, their gender profiles and likely electoral performance. They are usually full time political professionals whereas the selectorate are party supporters that give their time in support of the democratic process. They have more restricted access to information and their decisions are in part structured by this.

Candidate Characteristics

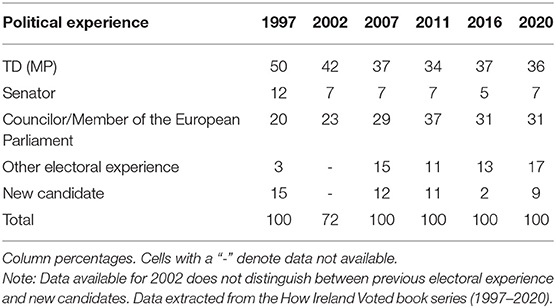

The analysis addressing RQ1 has essentially argued that the extent of IPD has been constrained by party elites but there is evidence to show that patterns of candidate selection in the main parties have evolved over recent elections. Unfortunately, data is not available to identify differences between convention selections and party elite selections but some general trends are clear and important. The data presented in the following tables cover all the major party candidates for the elections from 1997 to 20201. In Table 3 for completeness, this includes candidates from two small parties that no longer contest elections: the Progressive Democrats was disbanded in 2009 and Democratic Left merged with the Labour Party in 1999. The number of candidates, the size of parliament and the number of public representatives at local government level all varied over the period so figures are expressed in percentages for clarity of interpretation.

In seeking candidates that will win elections, political parties often prioritize experience and the literature in section two suggested that candidates with previous political experience were more likely to be selected. Indeed the benefits of incumbency at elections have been demonstrated widely across election types and electoral systems. The data presented in Table 3 largely confirms the electoral experience proposition. Fifty percent of candidates selected by parties at the 1997 general election were members of parliament (TDs), the dominance of incumbents has declined but they still account for more than a third of candidates. Members of the upper house (senators) account for on average a further 7.5 percent of candidates and the number of councilors chosen has been increasing since 1997.The percentage of new candidates chosen by political parties is very low and hovers around 10 percent, falling to just 2 percent at the 2016 election. The overall pattern is that parties (selectors and elites) strongly favor experienced political candidates and research that identifies local government as a major pipeline for candidates into national politics is directly corroborated in the data presented. The category other political experience includes people who have previously either contested an election or served in office and returned after a period out of politics, again, this accounts for a relatively small percentage of total candidates.

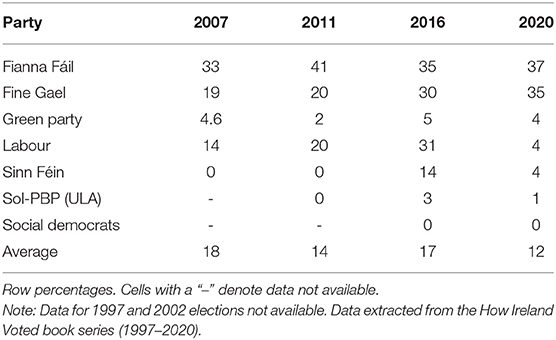

Political dynasties have been a feature of both local and national politics for generations. There is a long tradition of family members following a parent, or close family relative, into politics and also of siblings entering political life. A change in institutional rules in 2004 precluded members of parliament from also being local councilors at the same time and this led to a notable surge in the number of the family members of national parliamentarians contesting and winning local election seats, thus increasing the percentage of candidates with family connections in politics. Dynasties are occasionally subject to negative political commentary but dynastic candidates prove popular with voters and are generally seen as attractive candidates by political parties as they have a family record in politics and are likely to be able to mobilize existing campaign resources. Dynastic connections thus hint at a more intangible form of political experience. The data in Table 4 record candidates that have, or had a close family member active in politics. The connection does not have to be in the same party.

The older parties of the center right have the highest percentages of candidates with family members in politics, or previously in politics, but the data also shows that it is a fairly widespread phenomenon with all but the Social Democrats now recording some family political connections. The greater enfranchisement of party members has not diminished the selection of candidates from political dynasties with numbers in parties showing some variation but no sustained downward trend. The largest increase in family connections occurred in Fianna Fáil for the 2011 election. The Fianna Fáil vote collapsed at the election, several candidates withdrew in the run up to the election and the high percentage with a family connection likely reflects that those who remained on the ticket were drawn from longstanding dynasties with the most enduring connections to the party.

Progressing to gender, from Table 5 and from the earlier discussion, it is clear the gender profile of candidates has notably changed. The first election at which the legislative gender quota applied was 2016 and there was a sharp rise in the proportion of female candidate selected by the main political parties for that election. The percentage of women being selected by parties had been creeping up very slowly since the early 1990s but the pace of change was glacial and indeed this was one of the major arguments advanced to support the introduction of the quotas. The quotas caused a marked change and the percentage of female candidate more than doubled between 2011 and 2016 in the center right parties and although the left leaning parties tended to have better gender balance to begin, they also selected more women candidates after the introduction of the quota. While the overall percentage of female candidates improved again in 2020, the change was quite small and indeed some parties recorded a dis-improvement (Sinn Féin and Labour).

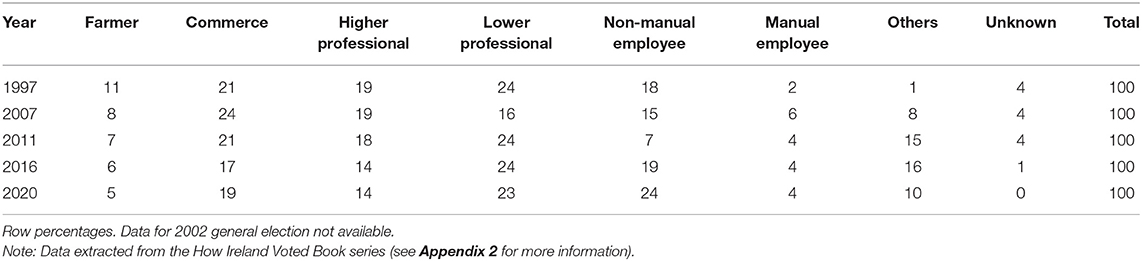

Finally turning to the occupation profile of candidates chosen by parties, the data in Table 6 uses the occupational classification system of the How Ireland Voted book series. The occupations are as follows: Farmer was a notable occupational background for politicians in Ireland for many decades although as will be shown in the data, as a group they are declining in politics; Commerce refers to those from a business backgrounds and includes small and medium sized business owners and those working in corporate roles in large firms; Higher professional includes the legal profession, architects, engineers, doctors, and pharmacists; The lower professional category includes teachers, nurses, and various types of medical therapists; Non-manual employee includes many types of civil and public servants, community and development workers, trade union officials and administrative staff; Manual workers includes those working in retail, tradespeople, and manufacturing; Others covers a wide variety of occupations that do not fit into any of the other categories but notably students, pensioners, and careers.

Table 6 shows that farmers as an occupational category are in decline across the five elections covered. This confirms a widely discussed pattern in Irish politics. Interestingly, there is also decline in the commerce category, albeit with a slight improvement in 2020. Higher professional is down across the period while lower professional is broadly stable. While non-manual employee percentages are up, the manual category increased between 1997 and 2007 but has been stable since and also accounts for the lowest proportion of candidates selected. The data suggest some small diversification in the occupational backgrounds of candidates across the period but those from professional backgrounds are the most likely to enter politics and account for more than a third of candidates across the whole period. Occupation background provides some insights into the socioeconomic profile of candidates. Wauters and Pilet (2015) argued against selectorate votes highlighting that they would favor well-networked individuals with greater access to resources and to a great extent, this is evident in the Irish data with the professions predominating and those from manual employment backgrounds amongst the least likely to enter politics.

There are also interesting cross party variations. Small parties of the left (Labour and the Greens) and the parties of the center right have large concentrations of candidates from professional backgrounds and commerce while farmers are concentrated in the two large center right parties (Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael). Non-manual and manual employees are more likely to become candidates for parties of the mid left and far left (Sinn Féin and Solidarity-People before Profit).

Summing up, striking changes in the gender profile of candidates are visible but this change has substantially been driven by the introduction of binding gender quotas. Patterns of change are of a much more modest order in the other characteristics highlighted. Parties continue to favor experienced political candidates, family links in politics have dropped a little and while there has been some diversification of the occupation profile of candidates, it is difficult to strip out the extent to which the greater presence of left wing parties in politics might be as important in shaping the change as IPD. Parties of the left have become considerably more successful at elections and are running more candidates, and they are more likely to select manual and non-manual employees. Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael have reduced their candidate numbers underpinning the reduction in the number of farmers and business people contesting elections.

Conclusion

The drift toward enhanced IPD and more inclusive decision making has been documented concretely around the world and Irish political parties were early adapters. Fine Gael and the Green Party were the first to use one member, one vote widely in selection decisions and they also allocated roles for party members in selecting party leaders, developing election strategy and voting on policy decisions. Decisions are taken at the constituency/district level using PR-STV as the voting system. All of the mainstream parties followed suit with some minor differences in relation to the membership qualification periods for becoming a candidate and exercising voting rights at conventions.

However, following Cross and Katz (2013), this article has also sought to demonstrate that institutional features such as the electoral system and party laws have notably qualified the advance of IPD within parties. Multi-seat constituencies under the PR-STV system have always meant that parties invested considerable time and resources in calibrating precise candidate numbers and their distribution across constituencies. The larger parties issue candidate directives setting out the number of candidates to be chosen and from which areas. But increased electoral volatility has made these scenarios more uncertain with changes to candidate numbers required often influenced by opinion polls even after the election is called. The need for continuous management and last minute changes to party tickets has led to greater intervention by party elites and diminution of the role of party members in the selection process. Furthermore, changes to party finance laws have created incentives for small parties to run paper candidates in a clear attempt to reach the funding threshold. And the gender quota has been carefully approached by party elites with a two pronged strategy deployed by the larger parties; requiring gender balanced tickets to be selected by party members at local conventions while also adding extra female candidates directly to the party ticket through elite decision structures. The electoral system has been a constant but increased volatility has required more intervention by elites. And legislative changes on party finance and gender quotas have inadvertently changed the balance of power within parties leading to a resurgence in elite decision making on candidate selection.

Finally, candidate numbers and profiles have evolved. The picture is complex. As Rahat (2009) argued, the more inclusive selectorate did not necessarily lead to more representative candidate selection decisions. It was not until gender quota legislation was implemented that the gender profile of candidates improved noticeably and as discussed this often involved direct intervention and structuring of decisions by party elites. The occupational profile of candidates has diversified with changes in all parties but the larger numbers of candidates from left wing parties has been a major driver in this area. But parties also continue to favor incumbents and those with family connections in politics suggesting that conceptions of electability have widened in some regards but longstanding features relating to incumbency are deep rooted and persist.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The data for general elections from 2011-2020 are held directly by the author and data for the 1997, 2002 and 2007 general elections were taken from the How Ireland Voted book series. The author is especially grateful to Yvonne Galligan and Liam Weeks who as authors of the candidate selection chapters in each of those volumes collected detailed information on the candidates that contested those elections.

References

Barnea, S., and Rahat, G. (2007). Reforming candidate selection methods: a three-level approach. Party Polit. 13, 375–394. doi: 10.1177/1354068807075942

Bille, L. (2001). Democratizing a democratic procedure: myth or reality? Candidate selection in Western European parties, 1960-1990. Party Polit. 7, 363–380. doi: 10.1177/1354068801007003006

Bjarnegård, E., and Kenny, M. (2015). Revealing the “secret garden”: the informal dimensions of political recruitment. Polit. Gend. 11, 748–753. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X15000471

Bjarnegård, E., and Kenny, M. (2016). Comparing candidate selection: a feminist institutionalist approach. Gov. Opposition 51, 370–392. doi: 10.1017/gov.2016.4

Bochel, J., and Denver, D. (1983). Candidate selection in the labour party: what the selectors seek. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 13, 45–69. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400003136

Bolleyer, N. (2010). The Irish Green Party: from protest to mainstream party? Irish Polit. Stud. 25, 603–623. doi: 10.1080/07907184.2010.518701

Buckley, F., Galligan, Y., and McGing, C. (2016). “Women and the election: Assessing the impact of gender quotas,” in How Ireland Voted 2016, eds M. Gallagher, and M. Marsh (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 185–205. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-40889-7_8

Buckley, F., and McGing, C. (2011). “Women and the Election,” in How Ireland Voted 2011, eds M. Marsh and M. Gallagher (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 222–239.

Byrne, E. A. (2013). Political Corruption in Ireland: 1922–2010. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Coffé, H., and Reiser, M. (2021). How perceptions and information about women's descriptive representation affect support for positive action measures. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. doi: 10.1177/0192512121995748

Coller, X., Cordero, G., and Jaime-Castillo, A. M., (eds) (2018). The Selection of Politicians in Times of Crisis. Routledge.

Cross, W. P., and Katz, R. S., (eds.) (2013). The Challenges of Intra-Party Democracy. Oxford: OUP Oxford.

Cross, W. P., Kenig, O., Pruysers, S., and Rahat, G. (2016). Promise and Challenge of Party Primary Elections: A Comparative Perspective. Montreal, QC; Kingston: McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP.

Farrell, D. M., Gallagher, M., and Barrett, D. (2018). “What do Irish voters want from and think of their politicians?, in The Post-Crisis Irish Voter., eds M. Marsh, D. Farrell, and T. Reidy (Manchester: Manchester University Press), 190–208. doi: 10.7765/9781526122650.00015

Fine Gael (2014). Fine Gael Constitution. Available online at: https://www.finegael.ie/app/uploads/2017/05/FG-Constitution-2014-Aug.pdf

Gallagher, M. (1980). Candidate selection in Ireland: the impact of localism and the electoral system. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 10, 489–503. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400002350

Gallagher, M. (2008). “The earthquake that never happened: analysis of the results,” in How Ireland Voted 2007: The Full Story of Ireland's General Election, eds M. Gallagher and M. Marsh (London: Palgrave Macmillan), p. 78–104. doi: 10.1057/9780230597990_6

Gallagher, M. (2011). “Ireland's earthquake election: analysis of the results,” in How Ireland Voted, eds M. Gallagher, and M. Marsh (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 139–171. doi: 10.1057/9780230354005_7

Gallagher, M. (2016). “The results analysed: the aftershocks continue,” in How Ireland Voted (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 125–157. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-40889-7_6

Gallagher, M. (2021). “The results analysed: the definitive end of the traditional party system?” in How Ireland Voted, eds M. Gallagher M.Marsh, and T. Reidy (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 165–196. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-66405-3_8

Gallagher, M., and Marsh, M., (eds.) (1988). Candidate Selection in Comparative Perspective: The Secret Garden of Politics.

Galligan, Y. (1999). “Candidate selection,” in How Ireland Voted (Routledge), 57–81. doi: 10.4324/9780429499999-3

Galligan, Y. (2003). “Candidate selection: More democratic or more centrally controlled?” in How Ireland Voted, eds M. Gallagher, M. Marsh, and P. Mitchell (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 37–56. doi: 10.1057/9780230379046_3

Green Party (2018). Green Party Constitution. Available online at: https://www.greenparty.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Green-Party-Constitution-2018-1.pdf

Hazan, R. Y., and Voerman, G. (2006). Electoral systems and candidate selection. Acta Polit. 41, 146–162. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500153

Hughes, M. M., Paxton, P., Clayton, A. B., and Zetterberg, P. (2019). Global gender quota adoption, implementation, and reform. Comp. Polit. 51, 219–238. doi: 10.5129/001041519825256650

Kakepaki, M., Kountouri, F., Verzichelli, L., and Coller, X. (2018). “The sociopolitical profile of parliamentary representatives in Greece, Italy and Spain before and after the “eurocrisis”: A comparative empirical assessment,” in Democratizing Candidate Selection (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 175-200. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-76550-1_8

Keenan, L., and McElroy, G. (2017). Who supports gender quotas in Ireland? Irish Polit. Stud. 32, 382–403. doi: 10.1080/07907184.2016.1255200

Labour Party (2017). Labour Party Constitution. Available online at: https://labour.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/labour_party_constitution_2017.pdf

Marsh, M. (1981). Localism, candidate selection and electoral preferences in Ireland: the general election of 1977. Econ. Soc. Rev. 12, 267–286.

Marsh, M., Sinnott, R., Garry, J., and Kennedy, F. (2008). The Irish Voter: The Nature of Electoral Competition in the Republic of Ireland. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Rahat, G. (2009). Which candidate selection method is the most democratic? Government Opposition 44, 68–90. doi: 10.1177/1354068808093405

Rahat, G., and Hazan, R. Y. (2001). Candidate selection methods: an analytical framework. Party Polit. 7, 297–322. doi: 10.1177/1354068801007003003

Rahat, G., Hazan, R. Y., and Katz, R. S. (2008). Democracy and political parties: on the uneasy relationships between participation, competition and representation. Party Polit. 14, 663.

Reidy, T. (2011). “Candidate selection,” in How Ireland Voted, eds M. Gallagher and M. Marsh (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 47-67. doi: 10.1057/9780230354005_3

Reidy, T. (2016). “Candidate selection and the illusion of grass-roots democracy,” in How Ireland Voted, eds M. Gallagher and M. Marsh (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 47–73. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-40889-7_3

Reidy, T. (2018). “Candidate selection in Ireland: New parties and candidate diversity,” in The Selection of Politicians in Times of Crisis, eds X. Coller, G. Cordero, and A. M. Jaime-Castillo (Routledge), 133–148. doi: 10.4324/9781315179575-9

Reidy, T. (2021). “Too many, too few: candidate selection in 2020,” in How Ireland Voted, eds M. Gallagher, M. Marsh, and T. Reidy (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 41–69. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-66405-3_3

Social Democrats (2021). Social Democrats Constitution. Available online at: socialdemocrats.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Social-Democrats-Constitution-Updated-27th-February-2021.pdf

Strøm, K. (2005). “Parliamentary Democracy and Delegation,” in Delegation and Accountability in Parliamentary Democracies (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 55–106. doi: 10.1093/019829784X.003.0003

Vandeleene, A., Dodeigne, J., and De Winter, L. (2016). What do selectorates seek? A comparative analysis of Belgian federal and regional candidate selection processes in 2014. Am. Behav. Sci. 60, 889–908. doi: 10.1177/0002764216632825

Vittori, D. (2022). Vanguard or business-as-usual? ‘New' movement parties in comparative perspective. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. doi: 10.1177/01925121211026648

Wauters, B., and Pilet, J. B. (2015). “Electing women as party leaders in cross,” in The Politics of Party Leadership: A Cross-National Perspective, ed J. B. Pilet (Oxford: Oxford University Press). P. 73–89. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198748984.003.0005

Weeks, L. (2008). Candidate selection: democratic centralism or managed democracy? In: How Ireland Voted 2007: The Full Story of Ireland's General Election, eds M. Gallagher and M. Marsh (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 48–64. doi: 10.1057/9780230597990_4

Appendix

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Candidate Professional Profile Data Sources

Data for Table 6 on the occupational profiles of candidates at elections were extracted directly from the How Ireland Voted book series. Specifically, see the following:

Galligan, 1999. Candidate selection. In How Ireland Voted 1997 (pp. 57-81). Routledge.

Pp. 72.

Galligan, 2003. “Candidate selection: More democratic or more centrally controlled?” in How Ireland Voted, eds M. Gallagher, M. Marsh, and P. Mitchell (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 37–56. doi: 10.1057/9780230379046_3

Weeks, 2008. Candidate selection: democratic centralism or managed democracy? In How Ireland Voted 2007: The Full Story of Ireland's General Election (pp. 48-64). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Pp. 59.

Reidy, 2011. “Candidate selection,” in How Ireland Voted, eds M. Gallagher and M. Marsh (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 47-67. doi: 10.1057/9780230354005_3

Reidy, 2016. “Candidate selection and the illusion of grass-roots democracy,” in How Ireland Voted, eds M. Gallagher and M. Marsh (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 47–73. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-40889-7_3

Reidy, 2021. “Too many, too few: candidate selection in 2020,” in How Ireland Voted, eds M. Gallagher, M. Marsh, and T. Reidy (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 41–69. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-66405-3_3

Keywords: candidate selection, one member, one vote, gender quotas, Irish elections, party finance laws, PR-STV

Citation: Reidy T (2022) Forwards-Backwards: Internal Party Democracy in Irish Political Parties. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:850607. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.850607

Received: 07 January 2022; Accepted: 31 May 2022;

Published: 30 June 2022.

Edited by:

Guillermo Cordero, Autonomous University of Madrid, SpainReviewed by:

Pierre Baudewyns, Catholic University of Louvain, BelgiumCarles Pamies, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), Spain

Copyright © 2022 Reidy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Theresa Reidy, dC5yZWlkeUB1Y2MuaWU=

Theresa Reidy

Theresa Reidy