- 1Department of Political Science, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, United States

- 2School of Politics and Global Studies, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, United States

Individuals in the United States appear increasingly willing to support and justify political violence. This paper therefore examines whether making partisan identities salient increases support for political violence. We embed priming manipulations in a sample of roughly 850 U.S. adults to investigate whether activating positive partisan identity, negative partisan identity, instrumental partisan identity, and American national identity might lead to differences in reported support for political violence. While we uncover no effects of priming various identities on support for political violence, we replicate and extend previous research on its correlates. Specifically, we demonstrate how various measures of partisan identity strength as well as negative personality traits are correlated with acceptance of political violence.

Introduction

On January 6th, 2021, protests left four people dead and dozens injured in events that culminated with insurrectionists occupying the United States (U.S.) Capitol and endangering elected officials (Barrett and Raju, 2021). The previous year, militia members attempted to kidnap the governor of Michigan (Flesher, 2020) and there have been multiple incidents of people fatally shooting protestors they were ideologically opposed to (Pietsch and León, 2020). At the same time, tolerance for political violence seems to be growing in the U.S.. For example, a recent survey found that 23% of respondents condoned violence in response to an electoral loss, and 40% regarded retaliatory violence as justified in some instances (Bright Line Watch, 2020). Given these trends and the potentially harmful consequences of violent rhetoric and political violence, there is a need to understand the causes of political violence and means to reduce it.

Political violence is, of course, a rare and extreme occurrence in the U.S. (Westwood et al., 2022). While this concept can broadly encompass acts such as political assassinations or attacks on government buildings, recent scholarship in the U.S. context primarily focuses more on threats leveled against political leaders, harassment, and hypothetical acts violence (Westwood et al., 2022). Such incivility and threats of violence are commonly examined against the backdrop of a record-high number of Americans displaying deep disdain and dislike for their partisan opponents, which has led to concerns that partisanship may ultimately fuel political violence. However, while much has been written on the deleterious effects of affective polarization, the extant literature does not clearly establish that affective polarization actually causes a range of political ills, including political violence (Iyengar et al., 2019; Yair, 2020). Most research on affective polarization focuses on non-political and social manifestations of the concept; for instance, its effects on romantic and familial relationships (e.g., Huber and Malhotra, 2017; Chen and Rohla, 2018; Iyengar et al., 2018) or economic interactions (e.g., Michelitch, 2015; McConnell et al., 2018). Indeed, results from experimental work that directly sought to manipulate affective polarization suggests that it has little to no effects on downstream political behaviors, including political violence (Broockman et al., 2020).

To date, however, there has been limited research examining whether partisan identity per se increases support for political violence. Notable exceptions include Kalmoe and Mason (2018) and Gøtzsche-Astrup (2021) who demonstrated that partisan strength and positive partisan identity predicted support for political violence and violent political intentions, respectively. This paper, first, seeks to replicate and extend work on correlates of support for political violence and, in particular, whether negative personality traits or more generalized negativity bias is associated with support for political violence.

The primary aim of the present study is to examine whether partisanship, in its various forms, affects acceptance of political violence. Moreover, because people hold multiple identities and we know that strong and activated identities will be more consequential politically (e.g., Huddy et al., 2015), and that the impact of partisan identity can be reduced (Levendusky, 2018), we test whether priming different social identities affects acceptance of political violence. Leveraging an original survey experiment, this paper investigates the relationship between the activation of various social identities related to partisanship and attitudes toward political violence. Using variables capturing partisan identity as priming manipulations, we heighten the salience of either negative partisanship, positive partisanship, instrumental partisanship, or American identity and test whether this affects support for political violence.

We acknowledge up front that we are principally concerned with the U.S. case given its high levels of affective polarization and partisanship. That said, the study is also relevant to multi-party systems given evidence of expressive, and even negative, partisan identities in such contexts (e.g., Bankert et al., 2017; Mayer, 2017) as well as a growing literature chronicling affective polarization and partisan outgroup hostility in multi-party and non-U.S. contexts (see e.g., Gidron et al., 2020; Reiljan, 2020; Harteveld, 2021; Wagner, 2021).

Different Facets of Partisanship

While partisanship is a potent force in American politics, researchers nonetheless disagree on the best way to conceptualize it. Campbell et al. (1960) famously defined partisanship as a “psychological attachment” to a political party. This definition, in turn, gives rise to two competing explanations of partisanship: an instrumental view and an expressive view (see Huddy et al., 2015). An instrumental approach to partisanship can be traced back to the idea of partisanship constituting a running tally of retrospective evaluations of party beliefs and performance (Fiorina, 1981; Achen, 1992). In this view, voters are primarily motivated by ideology, policy preferences, and performance evaluations, and update their affiliation accordingly, when parties change on one or more of these factors.

Expressive partisanship represents an alternative means of understanding partisanship. This approach conceptualizes partisanship as an enduring social identity with individuals developing a lasting, emotional connection to their party and short-term events do little to change such identification (Green et al., 2002). An expressive view of partisanship is grounded in social identity theory, which suggests that individuals tend to categorize themselves into “in-groups” and “out-groups,” based on perceived shared characteristics with other members of such groups (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). Thus, individuals are likely to have positive associations and emotional reactions toward their in-group, and may have negative, hostile reactions toward their out-group, as in-groups provide self-esteem and a sense of psychological reassurance.

Partisan identity may be especially powerful in the US context because of ideological and social sorting as American parties have increasingly come into alignment with political ideologies and other social identities (Malka and Lelkes, 2010; Mason, 2015, 2016). This means that individuals possess fewer “cross-cutting” identities which may dampen the effect of partisan identity, thereby increasing partisan bias, anger, and hostility when identities are aligned (Mason, 2016).

There is empirical evidence supporting both the expressive and instrumental views. Fiorina (1981), for instance, finds that economic performance affects citizens' presidential votes, supporting an instrumental view. More recently, Costa (2021) finds that voters penalize candidates for hostile, affective rhetoric, and prioritize policy and issue-level alignment over identitarian concerns. However, other scholarship challenges the assumptions of the instrumental view; for instance, Adams et al. (2011) find that European voters respond more to perceived partisan ideologies, rather than actual shifts in policy in party platforms.

In support of the expressive approach, Iyengar et al. (2012) find only a modest correlation between ideological disagreements and partisan identity when comparing ANES data on policy attitudes and in-party and out-party thermometer ratings. Moreover, there is evidence that some effects of policy preferences may actually be driven by these preferences signaling partisan identity rather than being the genuine result of instrumental preferences (Dias and Lelkes, 2021). Huddy et al. (2015) developed a unique, multi-item partisan identity scale, and compared how it predicted campaign involvement with a measure of ideological issue intensity, finding that partisan identity produced much stronger effects than instrumental concerns (see also Huddy et al., 2018 in a comparative context). Similarly, Mason (2015) showed that even people with moderate issue positions engage more in motivated reasoning, are more politically active, and express more anger with increasing identification. Moreover, in line with motivated reasoning stemming more from partisan identification than policy preferences, there further is evidence that partisans will easily alter their policy preferences following elite cues (Barber and Pope, 2019). Taken together, the above evidence points to an independent effect of partisan identity on political behavior that cannot be explained by a purely instrumental approach.

When considering social identities, a distinction can be made between in-group bias and out-group hostility (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). In the context of expressive partisan identity, the former is represented by “positive partisanship,” while the latter is represented by “negative partisanship,” capturing the idea that out-group hostility can exist independent of in-group bias, and vice versa (Abramowitz and Webster, 2018). For instance, an individual might choose to vote for Democrats primarily out of hostility toward the Republican Party, without necessarily having particularly positive feelings toward the Democratic Party. Scholarship demonstrates some correlation between in-group bias and out-group hostility; for instance, Mason (2015) finds that partisan sorting produces both increased partisan identity strength and anger directed at the out-party. Nevertheless, there is evidence that the concepts of positive and negative partisanship are, indeed, separate. Abramowitz and Webster (2018) find that negative ratings of each party have risen in the electorate in recent years, while positive evaluations of each have remained relatively stable. Thus, strong negative partisanship does not necessitate strong positive partisanship, and vice versa, given the different directions the two measures have followed. Bankert (2020) offers additional evidence, creating a Positive Partisan Identity Scale and a symmetric Negative Partisan Identity Scale to measure both concepts, finding that they predict political behavior in distinct ways: negative partisanship predicts anti-bipartisan attitudes more than positive partisanship does, while positive partisanship predicts political engagement and in-party vote more than negative partisanship does.

The Consequences of Partisan Identities

Strong group attachments predict several affective, emotional, and behavioral outcomes. For instance, more strongly identified members of a group display a greater need to uphold positive evaluations of their group (Branscombe and Wann, 1994; Doosje et al., 1995). Moreover, in the face of intergroup threat, social identity theory predicts that individuals who strongly identify with their group may exhibit more hostility toward their outgroup (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Hogg et al., 2017). Empirical evidence bears this out—Merrilees et al. (2014), for example, find that strong Catholic or Protestant identity in Northern Ireland youth predicts more aggressive behavior toward the respective out-group, when there is a threat of intergroup conflict. Individuals may engage in moral disengagement and out-group dehumanization to justify their, or their group's, harmful actions toward the out-group (Kelman, 1973; Bandura et al., 1975; Bandura, 1999).

As discussed previously, partisanship constitutes a powerful social identity. As such, partisanship displays similar dynamics, in terms of facilitating hostility toward the out-party, moral disengagement, and dehumanization. Webster (2018) finds that negative partisanship is associated with greater anger and hostility toward out-party candidates. Walter and Redlawsk (2019) demonstrate that voters are less likely to disapprove of politicians' immoral behavior if they belong to the same party, demonstrating the ability of partisan identity to motivate moral evaluations and reasoning. Stronger partisans are also more likely to dehumanize out-party members (Martherus et al., 2019; Cassese, 2020). These findings indicate a theoretical justification for positive and negative partisan identity increasing acceptance of political violence, as activating those group attachments may also activate the anger, moral disengagement, and dehumanization associated with them.

More directly, Gøtzsche-Astrup (2021) provides evidence for a relationship between positive partisan identity specifically being predictive of attitudes toward violence. Using a scale measuring intentions to engage in radical political action adapted from Moskalenko and McCauley (2009) and a manipulation from Delton et al. (2018) to experimentally heighten positive partisan identity, this work shows a relationship between positive partisan identity and greater intentions to engage in political violence. Kalmoe and Mason (2018) find a similar result, discovering that strong partisan identity predicts support for political violence, primarily in the form of threats and harassment.

Priming Social Identities

The salience of specific identities can be heightened through the use of psychological “primes,” or subtle cues intended to make a certain consideration more accessible (McLeish and Oxoby, 2008). Extensive literature demonstrates that priming identities can affect behavior and attitudes. For instance, priming individuals to consider their race or gender can produce “stereotype threat,” where individuals perform worse on tasks associated with negative stereotypes with regards to a group they belong to (Nguyen and Ryan, 2008; Picho et al., 2013). Researchers have also demonstrated that priming prisoners to consider their criminal identity results in more cheating in economic games (Cohn et al., 2015), and priming national identity results in more anti-immigrant attitudes (Wojcieszak and Garrett, 2018).

Individuals possess multiple social identities, from their race, to their gender, to their class. Partisan identity, thus, represents only one of many group identities individuals possess. Sometimes, these identities may compete with one another, with each representing different interests. Priming can, therefore, activate specific identities to influence preferences and behaviors. Klar (2013), for instance, examines the subgroup of Democratic parents, whose identities as parents and as Democrats sometimes clash in policy considerations. For instance, a parent might desire longer prison sentences for sex offenders, out of concern for their children, while Democrats generally prefer legislation that encourages rehabilitation. Priming either parental identity or Democratic identity shifted respondents' preferences on policies related to welfare spending, security spending, and criminal justice. Moreover, Levendusky (2018) finds that priming American national identity, can reduce affective polarization, as measured by feeling thermometer and trait ratings1. This likely occurs because the salient in-group shifts from being a partisan identity, where the other party represents an out-group, to being the broader collective of Americans, which includes both Democrats and Republicans. This recategorization demonstrates both the malleability of partisan identity and the efficacy of priming to activate different group memberships.

Hypotheses and Research Questions

Strong group attachments predict anger, moral disengagement, and greater willingness to engage in hostile and discriminatory behavior toward out-groups. We thus expect that making partisan identities more salient can increase such animosity. Conversely, in line with Levendusky's (2018) work, heightening the salience of a common in-group identity (i.e., Americans) should reduce such animosity. We thus hypothesize:

H1a: Increasing the salience of peoples' positive, negative, or instrumental partisan identity will increase support for political violence.

H1b: Increasing the salience of American identity will reduce support for political violence.

We are, furthermore, interested in whether increasing the salience of the identities listed in H1a leads to differential effects. The finding that partisan identity, as opposed to policy disagreement, drives affective polarization (Dias and Lelkes, 2021) and that strong social identities in general can be a precursor to violent behavior (Gøtzsche-Astrup, 2018), suggests potentially stronger effects for social identity variants of partisanship. Moreover, Bankert (2020) suggests that negative partisan identity may be particularly important for explaining partisan hostility and there is evidence that out-group hate drives behavior more than in-group love (see e.g., Weisel and Böhm, 2015). We therefore conjecture that the effects will be strongest for negative partisanship, followed by positive partisanship, followed by instrumental partisanship (H2).

In addition to the pre-registered hypotheses H1ab and H2 we also explore additional questions. We note that while we pre-registered these as secondary analyses, we considered them exploratory questions as opposed to directional hypotheses. First, we examine whether individual-level strength of the identities listed in H1ab (i.e., positive, negative, and instrumental partisan identity as well as American identity) is correlated with support for political violence.

Second, we use this study to replicate and extend prior work on the correlates of support for political violence. Here, the literature has focused on aggressive personality traits such as trait aggression as driver both of physical violence and support of violence more broadly (Kalmoe, 2014). Similarly, researchers have pinpointed the dark triad personality, which captures a variety of malevolent traits such as narcissism and Machiavellianism, as a key predictor (Jonason and Webster, 2010; Gøtzsche-Astrup, 2021). While we have no measure of trait aggression, we do examine whether respondents with dark triad traits show higher tolerance for political violence. At a more abstract level, we know that there is individual-level variation in negativity biases, which for instance, affect peoples' preferences for negative news (Bachleda et al., 2020) and thus we use this as a blunt proxy to examine whether people who seek out negative information (and thus might be more desensitized) are more tolerant of political violence. Moreover, while our focus is on specific conceptions of partisan identity, we also seek to replicate Kalmoe and Mason's (2018) and Gøtzsche-Astrup's (2021) finding that the traditional measure of partisan strength (i.e., the folded measure) is associated with support for political violence such that strong identifiers are more accepting of violence than independent leaners. Lastly, following Gøtzsche-Astrup's (2021) finding that the effect of partisan identity was moderated by dark triad traits, we also explore whether the individual-level factors outlined above moderate the dynamics outlined in H1ab.

Methods

We fielded an online survey using the Lucid platform, which provides a broad national sample of Americans (Coppock and McClellan, 2019). We excluded true independents from this experiment, resulting in a sample of 846 participants that was 56% Democratic and 44% Republican (including leaners). The sample was 50% female, with a mean age of 47 years. Prior to our experiment, the survey included standard demographic variables as well as the “Dirty Dozen” measure of the Dark Triad personality traits (Jonason and Webster, 2010) and a variable capturing negativity bias in news selection based on a headline selection task (Bachleda et al., 2020).

Our key experimental manipulation seeks to activate, or make salient, different identities by randomizing the questions respondents answer immediately prior to the partisan violence questions. Previous research has shown that the strength of identities can be increased through targeted question order manipulations (e.g., Kuo and Margalit, 2012) and that question batteries can act as primes by shifting salient identities and thus affecting political attitudes (e.g., Levendusky, 2018).

First, respondents in the control condition are not primed with any additional attitude battery. Second, respondents in the positive partisanship condition answer the questions comprising the eight-item “Positive Partisan Identity Scale” drawn from Bankert (2020). These questions tap into respondents' in-group affinity for their party by asking about agreement with statements such as “When I talk about this party, I say ‘we' instead of ‘them”' (α = 0.91)2. This treatment should primarily heighten in-group as opposed to out-group bias.

Third, respondents in the negative partisanship condition answer the questions from Bankert's (2020) eight-item “Negative Partisan Identity Scale,” which operationalizes respondents' hostility toward the out-party. For example, respondents are asked “When I talk about this party, I say ‘them' instead of ‘we”' (α = 0.88). Fourth, respondents in the instrumental partisanship condition answer a set of issue attitude questions drawn from Huddy et al. (2015). This ten-item battery gauges opinions on a range of polarized issues including abortion, immigration, and healthcare. For example, respondents are asked “In general, do you support or oppose same-sex marriage?” followed by how important the issue is to them personally (α = 0.55). Lastly, respondents in the American identity condition answer the five-question battery used in Levendusky (2018) as an American identity prime. It contains questions such as “How well does the term “American” describe you?” (α = 0.88). This condition aims to heighten the relevance of American identity as a salient in-group and thus de-emphasize partisan identity.

After answering these randomly assigned questions, respondents answer two sets of questions gauging their support for political violence. The first set is adapted from the 2020 ANES pilot study and contains three questions. The first asks whether it is justified for people to use violence to pursue their political goals, the second whether politicians deserve to be harassed or threatened, and the third whether members of the out-party “just deserve to be slapped.” The other set is drawn from Kalmoe and Mason (2018) and contains four questions that all include partisan information. For instance, respondents are asked whether it is ever justified for an in-party member to send threatening messages to an out-party leader.

Results

Before diving into the results, it is worth mentioning that most respondents reject political violence. We show the distribution of both dependent variables in Supplementary Figure A1 which highlights that the modal outcome for both scales is zero (i.e., full rejection of political violence) and that there is more variation in responses for the ANES questions which may capture more subtle forms of political violence (note that the scales are correlated at 0.74).

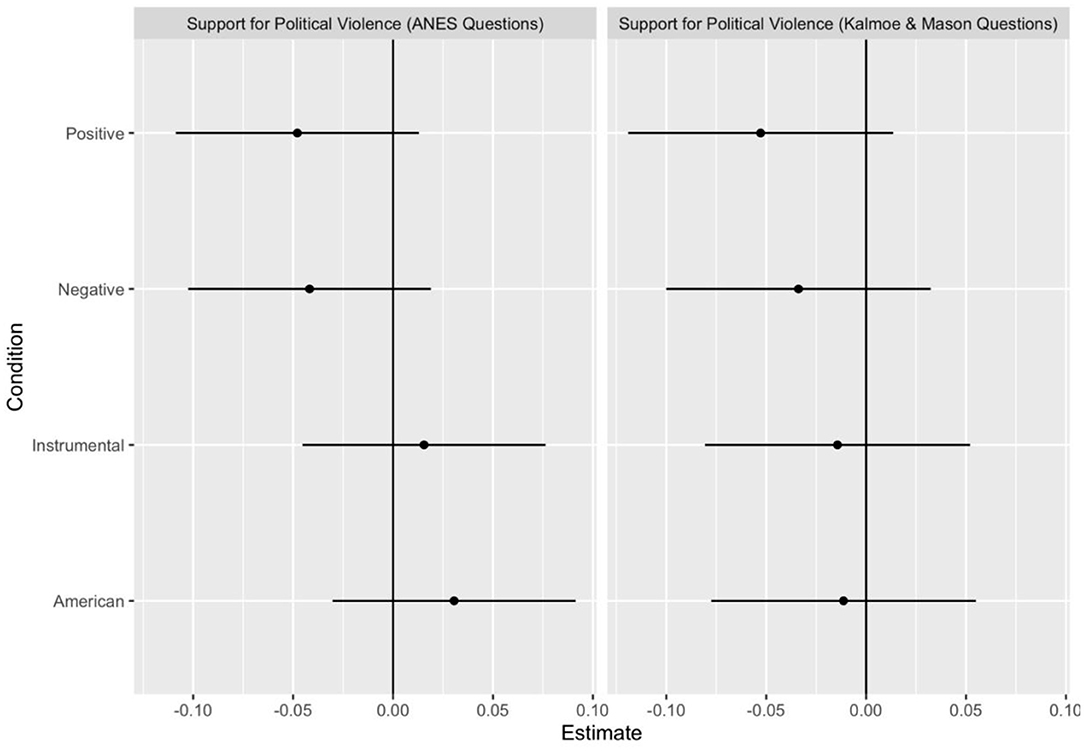

First, we turn to the correlational analyses and examine whether partisan strength, dark triad traits, and a propensity to seek out negative news are associated with support for political violence. We focus on respondents in the control condition to ensure no contamination from the experimental primes (though see Supplementary Table A2 for full sample models). We plot bivariate results in Figure 1 with models controlling for partisanship, sex, age, race, and education presented in Supplementary Table A3. Across both dependent variables we see that individuals who identify more strongly with their partisan group as well as those high in dark triad traits are more accepting of political violence, replicating both findings by Gøtzsche-Astrup (2021) and Kalmoe and Mason (2018). We find a somewhat weaker effect for individual-level negativity bias, providing marginal evidence that a general predisposition for negative news is associated with acceptance of political violence.

Figure 1. Relationship between key variables and support for political violence in control condition.

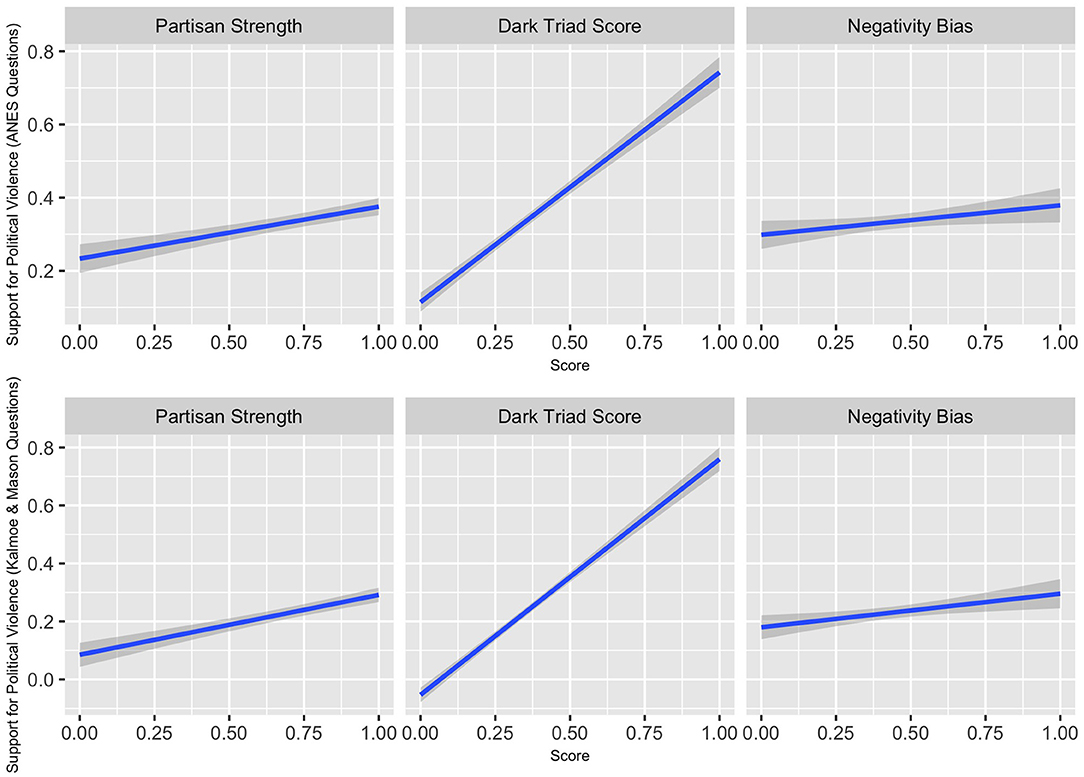

Next, we turn to our main analysis, namely whether priming different identities can affect support for political violence. Here, we regress the two political violence scales on a variable capturing treatment status. The resulting estimates (and 95% confidence intervals) are plotted in Figure 2, with the left panel showing results for the ANES questions and the right panel for the Kalmoe and Mason questions. The figure reveals no support for H1ab as none of the primes shift support for political violence vis-à-vis the control condition3. Moreover, as there are no effects for any of the conditions, we also do not uncover any support for differential effects in line with H2.

While we uncovered no direct effects of the priming manipulations, we also examine whether there are heterogeneous effects by partisan strength, dark triad traits, and negativity bias. The results (presented in Supplementary Figures A2–A4) do not provide evidence of any systematic heterogeneous effects. Across 24 panels we only uncover two significant interactions, thus leading to our conclusion that the insignificant main effects are not masking important treatment effect variation across these individual-level factors.

We also examine how the different scales capturing partisan and American identity that constituted our treatments are related to support for political violence. To guard against post-treatment bias, here we restrict the sample in each regression to only those respondents who answered each scale prior to the outcome variables. The results, controlling for the same variables as above, are presented in Table 1. There is strong evidence that both positive and negative partisan identity is strongly correlated with both operationalizations of acceptance of political violence. The results for American identity and instrumental partisanship are more mixed and inconsistent across the two specifications.

Lastly, in the Supplementary Material we consider the reverse question, namely whether priming political violence can shift responses to self-reported social identities. The rationale for this exploratory analysis is that priming the idea of political violence could either embolden partisans or it could lead to a backlash and thus result in muted expressions of partisan identity. We leverage the fact that all respondents answered these questions following the experiment. We find limited evidence for such a dynamic (see Supplementary Tables A4A,B).

Discussion

This paper did not uncover any evidence that priming political identities has any effect on acceptance of political violence. Several caveats need to be mentioned though. First, given the nature of our treatments, there were no manipulation checks and we thus cannot rule out failure-to-treat. Second, power analyses (using α = 0.05, and assuming a two-tailed test) suggest that our sample size was only sufficient to detect medium sized effects at 80% power (d = 0.3) and we thus caution that small effects may not be detectable given our sample size. Future research employing similar designs should thus seek to measure whether the primes indeed increase the salience of identification and should rely on larger samples given the possibility of small effects.

Despite the above caveats, the correlational findings presented here add to previous research examining the relationship between partisan identity as well as negative personality traits and support for political violence. Specifically, we find that the dark triad personality traits, partisan identity strength, positive partisan identity, and negative partisan identity are consistently associated with higher levels of support for political violence.

Data Availability Statement

Replication data and code are available at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GXGGGH.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Arizona State University's Institutional Review Board. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SK and FN conceptualized and designed the study and produced the manuscript. FN funded and fielded the study. SK analyzed the data and wrote the initial draft. FN led the revisions. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.835032/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Though note that there are questions surrounding the replicability of other non-experimental aspects of this work (see Brandt and Turner-Zwinkels, 2020).

2. ^See Supplementary Material for full question wordings of experimental conditions.

3. ^See Supplementary Material for an analysis looking at only respondents who passed an attention check.

References

Abramowitz, A. I., and Webster, S. W. (2018). Negative partisanship: why Americans dislike parties but behave like rabid partisans. Polit. Psychol. 39, 119–135. doi: 10.1111/pops.12479

Achen, C. H. (1992). Social psychology, demographic variables, and linear regression: Breaking the iron triangle in voting research. Polit. Behav. 14, 195–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00991978

Adams, J., Ezrow, L., and Somer-Topcu, Z. (2011). Is anybody listening? Evidence that voters do not respond to European parties' policy statements during elections. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 55, 370–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00489.x

Bachleda, S., Neuner, F. G., Soroka, S., Guggenheim, L., Fournier, P., and Naurin, E. (2020). Individual-level differences in negativity biases in news selection. Pers. Individ. Dif. 155:109675. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.109675

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 3, 193–209. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

Bandura, A., Underwood, B., and Fromson, M. E. (1975). Disinhibition of aggression through diffusion of responsibility and dehumanization of victims. J. Res. Pers. 9, 253–269. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(75)90001-X

Bankert, A. (2020). Negative and positive partisanship in the 2016 U.S. Presidential elections. Polit. Behav. 2020:282. doi: 10.1093/obo/9780199756223-0282

Bankert, A., Huddy, L., and Rosema, M. (2017). Measuring partisanship as a social identity in multi-party systems. Polit. Behav. 39, 103–132. doi: 10.1007/s11109-016-9349-5

Barber, M., and Pope, J. C. (2019). Does party trump ideology? Disentangling party and ideology in America. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 113, 38–54. doi: 10.1017/S0003055418000795

Barrett, T., and Raju, M. (2021). US Capitol Secured, 4 Dead After Rioters Stormed the Halls of Congress to Block BIDEN'S Win. Cable News Network. Available online at: https://www.cnn.com/2021/01/06/politics/us-capitol-lockdown/index.html

Brandt, M. J., and Turner-Zwinkels, F. C. (2020). No additional evidence that proximity to the july 4th holiday affects affective polarization. Collabra: Psychol. 6:39. doi: 10.1525/collabra.368

Branscombe, N. R., and Wann, D. L. (1994). Collective self-esteem consequences of outgroup derogation when a valued social identity is on trial. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 24, 641–657. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420240603

Bright Line Watch (2020). Bright Line Watch Survey Wave 12 Dataset [Data set]. Bright Line Watch. Available online at: http://brightlinewatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Public_Wave12.csv

Broockman, D., Kalla, J., and Westwood, S. (2020). Does Affective Polarization Undermine Democratic Norms or Accountability? Maybe not. Available online at: doi: 10.31219/osf.io/9btsq

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., and Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American Voter. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Cassese, E. C. (2020). Dehumanization of the opposition in political campaigns. Soc. Sci. Q. 101, 107–120. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12745

Chen, M. K., and Rohla, R. (2018). The effect of partisanship and political advertising on close family ties. Science, 360, 1020–1024. doi: 10.1126/science.aaq1433

Cohn, A., Maréchal, M., and Noll, T. (2015). Bad boys: How criminal identity salience affects rule violation. Rev. Econ. Stud. 82, 1289–1308. doi: 10.1093/restud/rdv025

Coppock, A., and McClellan, O. A. (2019). Validating the demographic, political, psychological, and experimental results obtained from a new source of online survey respondents. Res. Polit. 2019:22174. doi: 10.1177/2053168018822174

Costa, M. (2021), Ideology, not affect: What Americans want from political representation. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 65, 342–358. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12571

Delton, A. W., Petersen, M. B., and Robertson, T. E. (2018). Partisan goals, emotions, and political mobilization: The role of motivated reasoning in pressuring others to vote. J. Polit. 80:e697124. doi: 10.1086/697124

Dias, N., and Lelkes, Y. (2021). The nature of affective polarization: Disentangling policy disagreement from partisan identity. Am. J. Pol. Sci. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12628 [Epub ahead of print].

Doosje, B., Ellemers, N., and Spears, R. (1995). Perceived intragroup variability as a function of group status and identification. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 31, 410–436. doi: 10.1006/jesp.1995.1018

Fiorina, M. P. (1981). Retrospective Voting in American National Elections. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Gidron, N., Adams, J., and Horne, W. (2020). American Affective Polarization in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108914123

Gøtzsche-Astrup, O. (2018). The time for causal designs: Review and evaluation of empirical support for mechanisms of political radicalisation. Aggress. Violent Behav. 39, 90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.02.003

Gøtzsche-Astrup, O. (2021). Dark triad, partisanship and violent intentions in the United States. Personal. Individ. Differ. 173:e110633. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110633

Green, D., Palmquist, B., and Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan Hearts and Minds: Political Parties and the Social Identities of Voters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Harteveld, E. (2021). Fragmented foes: Affective polarization in the multiparty context of the Netherlands. Elect. Stud. 71:102332. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102332

Hogg, M. A., Abrams, D., and Brewer, M. B. (2017). Social identity: The role of self in group processes and intergroup relations. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 20, 570–581. doi: 10.1177/1368430217690909

Huber, G. A., and Malhotra, N. (2017). Political homophily in social relationships: evidence from online dating behavior. J. Polit. 79, 269–283. doi: 10.1086/687533

Huddy, L., Bankert, A., and Davies, C. (2018). Expressive versus instrumental partisanship in multiparty European systems. Polit. Psychol. 39, 173–199. doi: 10.1111/pops.12482

Huddy, L., Mason, L., and Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, Political emotion, and partisan identity. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 109, 1–17. doi: 10.1017/S0003055414000604

Iyengar, S., Konitzer, T., and Tedin, K. (2018). The home as a political fortress: family agreement in an era of polarization. J. Polit. 80, 1326–1338. doi: 10.1086/698929

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., and Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., and Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opin. Q. 76, 405–431. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfs038

Jonason, P. K., and Webster, G. D. (2010). The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychol. Assess. 22, 420–432. doi: 10.1037/a0019265

Kalmoe, N., and Mason, L. (2018). Lethal Mass Partisanship: Prevalence, Correlates, and Electoral Contingencies [Conference presentation]. APSA's Annual Meeting 2018, Boston MA, United States.

Kalmoe, N. P. (2014). Fueling the fire: Violent metaphors, trait aggression, and support for political violence. Polit. Commun. 31, 545–563. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2013.852642

Kelman, H. G. (1973). Violence without moral restraint: Reflections on the dehumanization of victims and victimizers. J. Soc. Issues 29, 25–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1973.tb00102.x

Klar, S. (2013). The influence of competing identity primes on political preferences. J. Polit. 75, 1108–1124. doi: 10.1017/S0022381613000698

Kuo, A., and Margalit, Y. (2012). Measuring individual identity: Experimental evidence. Comp. Polit. 44, 459–479. doi: 10.5129/001041512801283013

Levendusky, M. (2018). Americans, not partisans: Can priming American national identity reduce affective polarization? J. Polit. 80, 59–70. doi: 10.1086/693987

Malka, A., and Lelkes, Y. (2010). More than ideology: Conservative-liberal identity and receptivity to political cues. Soc. Justice Res. 23, 156–88. doi: 10.1007/s11211-010-0114-3

Martherus, J., Martinez, A., Piff, P., and Theodoridis, A. (2019). Party animals? Extreme partisan polarization and dehumanization. Polit. Behav. 43, 517–540. doi: 10.1007/s11109-019-09559-4

Mason, L. (2015). “I disrespectfully agree”: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 59, 128–145. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12089

Mason, L. (2016). A cross-cutting calm: How social sorting drives affective polarization. Public Opin. Q. 80, 351–377. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfw001

Mayer, S. J. (2017). How negative partisanship affects voting behavior in Europe: Evidence from an analysis of 17 European multi-party systems with proportional voting. Res. Polit. 4:2053168016686636. doi: 10.1177/2053168016686636

McConnell, C., Malhotra, N., Margalit, Y., and Levendusky, M. (2018). The economic consequences of partisanship in a polarized era. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 62, 5–18. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12330

McLeish, K., and Oxoby, R. (2008). Social interactions and the salience of social identity. J. Econ. Psychol. 32, 172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2010.11.003

Merrilees, C. E., Taylor, L. K., Goeke-Morey, M. C., Shirlow, P., Cummings, E. M., and Cairns, E. (2014). The protective role of group identity: sectarian antisocial behavior and adolescent emotion problems. Child Dev. 85, 412–420. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12125

Michelitch, K. (2015). Does electoral competition exacerbate interethnic or interpartisan economic discrimination? Evidence from a market price bargaining experiment in Ghana. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 109, 43–61. doi: 10.1017/S0003055414000628

Moskalenko, S., and McCauley, C. (2009). Measuring political mobilization: The distinction between activism and radicalism. Terror. Polit. Violence 21, 239–260. doi: 10.1080/09546550902765508

Nguyen, H. H. D., and Ryan, A. M. (2008). Does stereotype threat affect test performance of minorities and women? A meta-analysis of experimental evidence. J. Appl. Psychol. 93, 1314–1334. doi: 10.1037/a0012702

Picho, K., Rodriguez, A., and Finnie, L. (2013). Exploring the moderating role of context on the mathematics performance of females under stereotype threat: a meta-analysis. J. Soc. Psychol. 153, 299–333. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2012.737380

Pietsch, B., and León, C. (2020). Fatal Shooting in Denver Amid Dueling Protests, Police Say. New York, NY: New York Times.

Reiljan, A. (2020). ‘Fear and loathing across party lines'(also) in Europe: Affective polarisation in European party systems. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 59, 376–396. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12351

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1979). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict,” in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds S. Worchel and W. G. Austin (Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole).

Wagner, M. (2021). Affective polarization in multiparty systems. Elect. Stud. 69:102199. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102199

Walter, A. S., and Redlawsk, D. P. (2019). Voters' partisan responses to politicians' immoral behavior. Polit. Psychol. 40, 1075–1097. doi: 10.1111/pops.12582

Webster, S. W. (2018). Anger and declining trust in government in the American electorate. Polit. Behav. 40, 933–964. doi: 10.1007/s11109-017-9431-7

Weisel, O., and Böhm, R. (2015). “Ingroup love” and “outgroup hate” in intergroup conflict between natural groups. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 60, 110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.04.008

Westwood, S. J., Grimmer, J., Tyler, M., and Nall, C. (2022). American support for political violence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119, e2116870119.

Wojcieszak, M., and Garrett, R. K. (2018). Social identity, selective exposure, and affective polarization: how priming national identity shapes attitudes toward immigrants via news selection. Hum. Commun. Res. 44, 247–273. doi: 10.1093/hcr/hqx010

Yair, O. (2020). A Note on the Affective Polarization Literature. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3771264 (accessed December 25, 2020).

Keywords: partisan identity, political violence, priming, negativity, affective polarization

Citation: Kacholia S and Neuner FG (2022) Priming Partisan Identities and Support for Political Violence. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:835032. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.835032

Received: 14 December 2021; Accepted: 12 April 2022;

Published: 19 May 2022.

Edited by:

Alessandro Nai, University of Amsterdam, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Laura Stephenson, Western University, CanadaScott Clifford, University of Houston, United States

Copyright © 2022 Kacholia and Neuner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fabian Guy Neuner, Zm5ldW5lckBhc3UuZWR1

Suhan Kacholia

Suhan Kacholia Fabian Guy Neuner

Fabian Guy Neuner