94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Front. Polit. Sci., 29 March 2022

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.832440

This article is part of the Research TopicOrigins, Foundations, Sustainability and Trip Lines of Good Governance: Archaeological and Historical ConsiderationsView all 14 articles

For nearly 200 years, Western social science has argued that good government, embodied in democracy, originated exclusively in Western Europe and was introduced to the rest of the world. This Eurocentric vision has profoundly shaped social science's approach to the non-Western World (and pre-modern Europe). Importantly, distinct theories (e.g., Oriental Despotism, Substantivism, etc.) were developed to address premodern state-building in Asia, the Near East, Africa, and the Americas because “normal approaches” could not be applied in these areas. Regardless of the approach and the geographical area, Europe inevitably appears at the pinnacle of social evolutionary change. However, recently, Eurocentric theories have been subject to reevaluation. In this paper, we pursue that critical agenda through a comparative study of demokratia's original formulation and ask: would a 5th century B.C.E. Athenian recognize democratic attributes in 15th century C.E. Tlaxcallan, Mexico? We answer this question by first summarizing literature on Classical Athens, which concludes that among the key values of demokratia were isonomia and isegoria and then explore the evidence for similar values in Tlaxcallan. Our response is that an Athenian would see strong parallels between his government and that of Tlaxcallan.

In this paper, we examine the late pre-contact state of Tlaxcallan, located in the Central Mexican Highlands, through the lens of Classical Athenian political philosophy to challenge Eurocentric thinking on the evolution of political strategies in human societies. Western social science has repeated for nearly 200 years that good government, embodied in Western European democracy, originated exclusively in the West through the transition from the Medieval feudal order to the modern nation state. Then, as Tilly, 1975 expressed it (1975, p. 608), democracy “moved from the West to the rest of the world” (where it has a decidedly mixed history of providing good government, e.g., Rothstein, 2011) (see also Chou and Beausoleil, 2015, p. 1). In this Eurocentric discourse, the philosophical roots of democracy are traced ultimately to political reforms enacted during the 6th to 4th centuries B.C.E. in Athens. Yet, although the Athenians came to call their radical political experiment dημoκρατiα (demokratia)—rule by common people—it is not always regarded as “really” democratic, lacking political parties and competitive elections, and not everyone was allowed to vote (e.g., Hadenius and Teorell, 2005). In this argument, it has only been through the superior social evolution originating in Europe that “true” democracy could be realized (cf. Holland-Lulewicz et al., 2022).

While we see Eurocentric ideology in studies of democratic origins (Blanton and Fargher, 2008, p. 294–299), it has been marshaled repeatedly and continues to be a way to deny that non-Western peoples have ever been capable of constructing good government based on democratic principles or of exhibiting other features that are associated with modernity (Goody, 2006; see also Niaz, 2014; Chou and Beausoleil, 2015; Youngs, 2015; Economou and Kyriazis, 2017; Duindam, 2018; Putterman, 2018; Daly, 2019; Abbas, 2020; Weede, 2020). For example, Economou and Kyrizis as recently as 2017 assert that, “The emergence of property rights and their protection and security is now accepted as one of the basic elements for economic development and one of the basic differences in economic development that took place in some 16–17th century European states, such as England and the United Provinces (Dutch Republic) vis-a-vis the great Asian empires like the Ottoman, the Indian Mughal, and China under the Ming and Qing Dynasties (North, 1981, 1990) [emphasis added]” (p. 53). Accordingly, some Western social science continues to use liberal democracy, as it is understood in countries like the US (circa 1970), England, and Scandinavia, as the benchmark for critiquing other political formations (e.g., Hadenius and Teorell, 2005; Berman, 2007; Mainwaring and Bizzarro, 2019). In this vision, premodern Asian states and those in the Islamic Mediterranean have been viewed as mired in despotism, while, in the eyes of some, in sub-Saharan Africa states never did develop (as Scott (2017), p. 21 put it: “no cassava states”, cf. Blanton, 2019).

Yet recently anthropologists and anthropological archaeologist have begun to increasingly challenge Eurocentrism through comparative research (e.g., Blanton and Fargher, 2008; Blanton with Fargher, 2016; Carballo and Feinman, 2016; Feinman and Carballo, 2018; Blanton et al., 2020, 2021; Graeber and Wengrow, 2021; Blanton with Fargher see also the collection of papers included in this research topic). As part of this effort, in this article we present the case of Tlaxcallan, a late pre-contact state located on the Central Mexican Plateau. We do this because Tlaxcallan was among the most collective states in human history and possibly represents a polity comparable with the polis of Attica, with respect to the development of democratic values. To do this, we take a comparative approach that begins with a study of demokratia's original formulation in Classical Athens and then look for evidence of institutions in Tlaxcallan that materialized political philosophies comparable to those that were key to Athenian demokratia (especially isonomia and isegoria) with analogous outcomes (e.g., rights, political participation).

Cross-cultural comparison is a well-developed and empirically valid anthropological approach that allows for juxtaposing completely different cultural frameworks. Therefore, it differs from more traditional approaches in political science, where comparison is limited to modern nation states that in most cases feature similar governing structures and for which there are highly standardized data sources (e.g., UN, World Bank, WHO, Freedom House, etc.), as well as limited comparison with or among Medieval/Renaissance states. However, our method has also been influenced by political scientists (especially Coppedge, 1999 on the large-N, small-N problem). We agree entirely with Munck and Verkuilen (2002) that it is necessary to “balance the goal of parsimony with the concern for underlying dimensionality”, and with their comment that comparativists “should not define a concept with too many attributes” because of the way it will burden the potential for comparison. Thus, our focus here is on the key values that underlie demokratia in Classical Athens and not particular institutions or structures (such as juries or the Boule, etc.). As Hansen (1999), p. 85 points out, “The constant interplay of the two concepts is characteristic of Athenian democratic ideology and shows, once again, the close affinity between modern democracy and Athenian demokratia looked at as a political ideology rather than a set of political institutions [emphasis added].” Thus, we do not hold that demokratia is defined exclusively by the highly particular institutions developed in Athens, or any other democratic polis. Defining it as such serves to only to uphold the supposed uniqueness of Europe and defend Eurocentric arguments.

Accordingly, we first investigate the underlying values of demokratia as it developed during the 6th and 5th centuries B.C.E. in Athens and the materialization of these values in Athens' urban landscape (including Piraeus) and in the Athenian colony of Thurii. We then look for these attributes in the political system and urban landscape of Tlaxcallan. We conclude that while we cannot directly confirm that Tlaxcallan had a general assembly where all male citizens gathered in one place to vote (comparable to the ekklesia) (though we have strong circumstantial evidence), many other features consistent with demokratia's philosophy were materialized in its political institutions and structures, and some were far better developed than in Athens. Accordingly, we think that a Classical Athenian would consider Tlaxcallan to be comparable to dημoκρατiα (demokratia) and would see it as much unlike either government by a τv́ραννoς (tyrant) or an òλιγαρχiα (oligarchy).

The emergence of the democratic experiment in Classical Athens, as well as other Greek poleis, was a century-and-half long process in response to the unpopular Archaic period aristocracy and the growing marginalization of commoner households (e.g., Hansen, 1999, p. 32–34; Wallace, 2007, p. 49) who agitated for political and legal reforms. In the specific case of Attica, Drako's extremely harsh and elitist law code mostly likely contributed significantly to this marginalization in Attica (Tangian, 2020, p. 7–8). Thus, in many poleis, like Attica, populist strongmen manipulated discontent among the poor, gaining their support, which they used to rise to power as tyrants (Goušchin, 1999; Wallace, 2007, p. 51–52). They came to power with a mandate to bring the aristocracy under control and alleviate the plight of the poor, however, many ignored the mandate and concentrated power, becoming authoritarian dictators that played the poor off against the aristocracy (Wallace, 2007, p. 73, 75). In the face of social discord, the Athenian people turned to a forward-thinking, liberal aristocrat named Solon (although whether Solon was real and responsible for these reforms is less important than the changes that were enacted) to institute reforms. Rather than mobilizing the people to make him tyrant through violence (Wallace, 2007, p. 58), he followed a path of establishing rule of law (institutions) to realize good government (Wallace, 2007, p. 58).

According to the later accounts, Solon liberated debt slaves and made debt slavery for Athenian citizens illegal, including buying back citizens sold abroad (Wallace, 2007, p. 59). Extremists were calling for equal distribution of land, but Solon did not heed them (Wallace, 2007, p. 65). Instead, he “redistributed land” by returning plots lost by farmers who were indebted and liberated public lands from elite monopolization and reopened them (Wallace, 2007, p. 59). He established equality under the law for all citizens, setting in motion a series of changes that would eventually limit, if not end, special treatment for the wealthy (Wallace, 2007, p. 59). He also established the right for all citizens, including the poor, to appeal decisions made by elite justices to the Hλιαiα (heliaia or public court) (Wallace, 2007, p. 60). He structured (male) citizens into four classes based on landholding and military services. He expanded membership in the ekklesia (people's assembly) to include all four social classes [Drako may have contributed to the formation of the ekklesia, but no evidence remains of his laws making it difficult to assess his contribution (Tangian, 2020, p. 7–8)]. There is debate as to the degree of free speech in Solon's reforms. Some scholars argue that the lowest class, thetes (smallholders and landless citizens), could vote, but could not speak or propose laws (Wallace, 2007, p. 61). Others argue that they did in fact address the assembly, thus, free speech was an early development; while other historians have argued that thetes were excluded until reforms were made in the 5th century (Raaflaub, 2007, p. 150). Based on our experience with social class in premodern states, we think that Raaflaub (2007) overstates the ability of the state to distinguish easily between social classes, especially with a growing urban population (cf. Ober, 2007, p. 97; Vlassopoulos, 2007). Regardless of institutional frameworks at this time, in practice the economic burden for poor individuals was probably so significant that it limited the ability of many to participate in the ekklesia and juries.

Individuals from the upper two or three classes were elected by the demos (the people) to serve as archons, treasurers, “sellers” of public contracts (tax collectors), prison officials, and kolakretai (state financial administrators) (Wallace, 2007, p. 61). This reform removed control over these offices from the hereditary aristocracy. The four tribes of Attica selected 10 candidates each for the position of archon, from the two highest social classes (pentakosiomedimni and hippeis); and from them, nine were selected by lot to serve (Wallace, 2007, p. 62). At the end of their terms, they were subject to scrutiny by the demos for their conduct. The boule (senate) with 400 members (100 representatives from each of the four tribes of Attica) was created at this time [it is possible that it was created earlier as part of Drako's reforms, but direct evidence is absent (Tangian, 2020, p. 7–8)]. The members of the boule were drawn by lot from among the members of the two highest social classes (pentakosiomedimni and hippeis) (Wallace, 2007). It prepared motions to be heard by the ekklesia and oversaw various political officials. These changes enfranchised an expanding section of Athenian citizens and were the first steps to reducing the power of a high council (the areopagus) made up of hereditary elites who were life-time members of that council (archons and ex-archons).

Despite these reforms, problems persisted, and, around 560 B.C.E., Pisistratus violently installed himself as tyrant (Morris and Powell, 2010, p. 217). After 19 years as the ruler of Athens he died and by 511 B.C.E. his heirs were either killed or exiled (Morris and Powell, 2010, p. 217). Athens was in disarray and Isagoras, with the backing of the Spartan king, made his bid for tyranny, but as the story goes something unexpected happened. The boule refused to disband impeding the installation of 300 elites selected by the Spartan king to support Isagoras. In this moment the people (demos) rallied to the boule's support, forcing the Spartan king and his supporters first to retreat to the Acropolis and then to leave the city (Ober, 2007, p. 88). They then recalled Kleisthenes, an extremely wealthy politician, from exile to lead reforms in 508/07 (Ober, 2007, p. 85). Before his exile Kleisthenes had, unexpectedly, thrown his lot in with the lower classes. Upon his return, instead of using their support to make himself another tyrant, he held true to his promises to the demos, especially the poorest citizens (sub-hoplites) (Goušchin, 1999, p. 17; Ober, 2007, p. 85, 87, 88). Kleisthenes and the coalition he headed undertook a series of major reforms that further increased the power of commoners and reduced the power of the wealthiest class, proposals approved by a majority vote in the ekklesia, which, according to many scholars, was, at this point, dominated by the lower classes (Pomeroy et al., 2012, p. 206). Thus, the demos took charge of the government, making it a true democracy (Ober, 2007, p. 86; Raaflaub, 2007; Vlassopoulos, 2007, p. 150; disagrees and sees limits to participation by sub-hoplites).

Kleisthenes proposed a reorganization of the population of Attica into 30 trittyes, and ten tribes consisting of 3 trittyes, doing away with the traditional four tribes that had been a factor in political unrest (Wallace, 2007, p. 76). Each tribe then included one trittys from the coast, one from the interior, and one from urban Athens. Thus, each trittys contained several demes (villages or urban neighborhoods), and bound citizens together from across Attica and not just neighbors, creating a national identity (Morris and Powell, 2010, p. 219). He also strengthened the demes, making them democratic and partially self-governing. He established ~139 demes throughout Attica (Paga, 2010, p. 1; Wallace, 2007, p. 76). The deme became the backbone of the democratic reform. Deme authority was vested in a general assembly where all members voted (Whitehead, 2014). Each year the assembly elected a demarch as an administrative head and reviewed the financial statements of the previous demarch. The deme assembly selected the individuals who could potentially serve on the boule for 1 year (Whitehead, 2014). It also engaged in a range of other activities, including establishing local (deme-level) laws and norms. Each deme built a meeting place and maintained membership rosters (Wallace, 2007, p. 77; Whitehead, 2014). Importantly the reorganization of the demes removed elite control over local politics and placed that control in the hands of citizens. These reforms significantly increased local social capital as well as promoting shared service in the army and the boule, and collective participation in deme festivals (Raaflaub, 2007, p. 145). Social capital refers to the networks, institutions, and structures that encourage social actors to engage in specific behaviors or actions (Coleman, 1988, p. S98). The building of social capital, in the form of robust social networks based on repetitive interaction and local institutions backed by sanctions, has been demonstrated to be fundamental to the collective activities necessary to achieve democratic processes, because they build trust among local social actors (Blanton and Fargher, 2008; Ahn and Ostrom, 2009; Fargher and Blanton, 2021).

The Kleisthenic reforms intentionally mixed individuals that did not know each other or their families, thus family name and history could no longer be used to exclude people from political participation, a strategy long used by the aristocracy to control politics (Raaflaub, 2007, p. 145). The mixing of individuals from different regions of Attica ensured that members of demes and trittys did not know each other, which also blurred the distinction between hoplites and thetes (as well as some metics (foreigners) and slaves, and, thus, would have increased political participation at all levels (Ober, 2007, p. 97; Vlassopoulos, 2007).

Kleisthenes also proposed that the boule be reformed to include 500 members, 50 representatives from each of the 10 tribes selected by lot (Ober, 2007). Eligibility for selection was expanded to include more citizens. Free speech was increased in the ekklesia, making it in Athenian eyes a truly democratic assembly (Ober, 2007). While the exact number of members is unknown, and would have varied, the quorum was set at 6,000 members and attendance at its sessions was considered mandatory (Pomeroy et al., 2012, p. 245). Some powers still held by the areopagus and the archons were transferred to the boule, while the archons were left only with administrative duties (Pomeroy et al., 2012, p. 206). “The principal functions of the boule were to engage in deliberative decision-making regarding matters of state finance, religion, public works, and the army and navy, and to draw up the probouleumata (proposals) to present to the ekklesia” (Paga, 2021, p. 116). Ostracism was also introduced as a mechanism to limit the power of wealthy individuals seeking to consolidate their personal power and disrupt institutional processes (Ober, 2007, p. 85). The democratic and institutional changes enacted under Solon's and Kleisthenes' leadership are clearly visible in 465 B.C.E. when the archon Kimon was impeached on corruption charges and tried (Pomeroy et al., 2012, p. 238). Although he was acquitted, this process demonstrates that although the archons had great administrative powers, they were subject to control by the demos. However, a few final reforms were needed to fully bring the aristocracy under control.

These reforms came between about 460 and 450 B.C.E. First, the ekklesia approved a series of reforms, proposed by Ephialtes, that stripped the areopagus of the few functions it still retained, transferring them to the ekklesia, boule, and heliaia; this left the areopagus with jurisdiction only over homicides and some religious matters (Pomeroy et al., 2012, p. 241). Shortly thereafter, aristocratic conservatives, angered by the policy proposals of Ephialtes, arranged for his assassination, which left his ally Perikles as the demos' spokesman (Pomeroy et al., 2012, p. 241–242). Afterwards, eligibility for service as an archon was extended to members of the hoplite class, which effectively ended the aristocratic monopoly on the highest offices (Wallace, 2007, p. 80). Finally, Perikles proposed pay for citizens serving on juries, which was later expanded to other forms of political service (e.g., serving on the boule and as a magistrate, as well as attending ekklesia meetings and voting) (Pomeroy et al., 2012, p. 248). This pay made it possible for many poor citizens to fully participate in the government, which completed the transfer of power from the aristocracy to the demos. Some scholars have argued that participation in juries by a large number of citizens drawn from across social sectors would have provided an important element of democracy (e.g., McCannon, 2010).

From Solon's reforms, through Kleisthenes, to the final reforms proposed by Perikles and approved by the assembly, Athenian democracy developed around two basic principles: isonomia, or equal rights among citizens, and isegoria, free speech (Raaflaub, 1996, p. 143–145, 2007, p. 146; Ober, 2007, p. 95; cf. Hansen, 1999). Initially isonomia was applied by Solon in the area of legal rights, especially protections from debt slavery, equal legal rights, and the right to appeal legal decisions to the public courts. Over time, participation in public juries was expanded to ensure legal isonomia for all citizens, including instituting pay for jury duty so even the poorest citizens could fulfill this democratic duty. In terms of political rights, access to the ekklesia was extended to sub-hoplites (thetes) by either Solon or Kleisthenes, and rights to occupy other political offices, as well as serve on the boule, were gradually extended down the social hierarchy; as well, pay for these services was instituted during the mid 5th century. By the end of our focal period (600–450 B.C.E.), wide access had even been opened to the areopagus (which had been arguably the most elite body in Athens).

Equality was never totally achieved in the economic sphere, because not all Athenians had equal access to land or other revenue producing activities (Ober, 2007, p. 125). Thus, economic inequality persisted throughout the democratic period, despite high levels of equality in the political and legal spheres. However, comparative work by Ober (2007) has demonstrated that inequality decreased from the Archaic period into the Classical Period and by the end of the democratic period the poor and middle classes were better off as compared to their counterparts in Medieval Europe and Imperial Period in Rome (see also Morris, 1998; Kron, 2011; Patriquin, 2015). Despite these changes, quantitative analyses by Ober (2007) and Morris, (1998, p. 235–239) of inequality, using diverse methods, arrived at a Gini index for Classical Athens of roughly 0.38. This value is moderate when compared with more global studies, which demonstrate that wealth inequality was more strongly developed in Eurasia than North America and Mesoamerica (Kohler et al., 2017). More specifically when compared with the Gini value of 0.12 for Teotihuacan, a Central Mexican city that reached its apex between 400 and 600 C.E. with a population of 125,000 people, Classical Athens appears comparatively unequal (Kohler et al., 2017, Supplementary Table 2; Millon, 1973).

Coupled with isonomia, the democratic state protected isegoria. Again, with the reforms of Solon and Kleisthenes, it is not entirely clear if all citizens had equal rights to speak in the assembly or introduce legislation (Ober, 2007; Raaflaub, 2007; Wallace, 2007, p. 65–66). However, by the peak of the democratic period in the late 5th century to the middle 4th century (with some minor interruptions), all citizens were afforded the right to speak in the ekklesia (e.g., Raaflaub, 2007, p. 149; Wallace, 2007, p. 79). Given the anonymity afforded by the size of the assembly (6,000+ individuals) and the complexity of Athenian society, Vlassopoulos (2007) has argued that non-citizens (metics, slaves) may have masqueraded as citizens, addressed the ekklesia, and possibly voted (he even includes women disguised as men, but some scholars might question this). Overall, the implementation of this political philosophy produced a society marked by, “… the generalized feelings of trust and good faith between social classes, between mass and elite, between hoplites and thetes” (Ober, 2007, p. 101).

The transition to democracy in Classic Athens, not only required major institutional reforms that transferred power from aristocrats to commoners, but it also required reform of urban and rural landscapes to create a built environment suited to their new governing system. Within Athens, this involved moving the center of civil and political life to an open space adjacent to and below the Acropolis, Pnyx, and Areopagus (Ober, 2007, p. 98; Paga, 2021) which became the agora. It was anchored by the construction of a massive drainage canal, followed by erection of the structure that housed the boule (bouleuterion), along with other important public buildings and temples including the Stoa Basileiso (Paga, 2021). The bouleuterion was constructed as a nearly square hypostyle hall to provide intervisibility and to encourage participation (Paga, 2021, p. 97). Both the bouleuterion and the Stoa Basileiso were constructed using the ancient Greek Doric order, which served to sanctify and legitimate democratic political processes and governing (Paga, 2021). When the central market was also officially moved to the agora (Paga, 2021, p. 95), it concentrated political, economic, and some religious activities, making it the heart of the city. The mixing of the mundane, the political, and the religious that came to define the Athenian agora was reviled by conservative pundits (Vlassopoulos, 2007, p. 40). The nearby Pnyx Hill, located about 1,000 m from the agora, was selected as the seat for the ekklesia and new construction there created a flat space for the meetings of the assemblies (Kourouniotes and Thompson, 1932; Joyner, 1977). Its first construction phase created an open-air assembly space that could hold several thousand citizens, although later the space was significantly expanded in two additional construction phases during the 4th century (Kourouniotes and Thompson, 1932; Joyner, 1977) to accommodate increasing participation as the lower classes increasingly took control of the government.

Together the agora and the Pnyx Hill formed the spaces in which democracy played out at the polis scale. In the agora, where crowds of Athenians frequently gathered in shops, workshops, and open spaces, politicians would make speeches and engage in discussions to promote diverse policies and the people themselves would have discussed, debated, and deliberated on them and the tidings of the day Vlassopoulos (2007, p. 40–41). Paga (2021, p. 102) notes that, “An Athenian citizen could easily conduct his business in the agora, attend a meeting of the boule or read the announcements and pre-posted agenda, and then make his way to the Pnyx for debate and voting.” A citizen also could also see and hear activities like, “…trials, oaths, display of laws…” at the Stoa Basileios, which faced onto the agora Paga (2021, p. 106). Thus, as Vlassopoulos (2007, p. 42) concludes, “… in this non-institutional setting [the Agora], one can imagine poor, common Athenians speaking their own minds, presenting their grievances, even suggesting courses of action that might be subsequently taken up by the assembly.” Accordingly, it was in the agora that Athenians were informed and made up their minds concerning important policies that they would later vote on, influenced by one another, as well as politicians and the multitude of non-citizens (e.g., women, metics, slaves) that frequented this “free space” and participated in political discussions. The agora was such an important political space that Paga (2021, p. 94) contends that barring entrance of citizens from it effectively eliminated them from participation in the political system.

Although the data are thin, there are tantalizing tidbits in the historic and archaeological records that point to the fact that open and accessible spaces were also the focal point of deme political activities (Thompson, 1971, p. 73; Jones, 2011, p. 45, 294; Apostolopoulos and Kapetanios, 2021). Like the polis, demes were governed by assemblies that included all citizens that were registered members (Whitehead, 2014). In the case of at least one rural deme, we have documentary data indicating that an open space was donated by a wealthy citizen to be used as the deme's agora (Whitehead, 2014: passim). Documents also mention an urban agora associated with a deme of Athens (Osborne, 2007, p. 198). In other cases, demes constructed theaters dedicated to the Dionysus that were used for deme assemblies and other political activities (or even tribe assemblies) (Ober, 2008, p. 205–206; Paga, 2010). These spaces were key to social capital building activates that were part of the everyday democratic life of the deme, making it the backbone of Athenian democracy (cf. Fargher and Blanton, 2021). These activities include, for example, the deme assemblies, collective law making, evaluation of demarchs at the end of their terms, and the festival of Dionysus, etc.

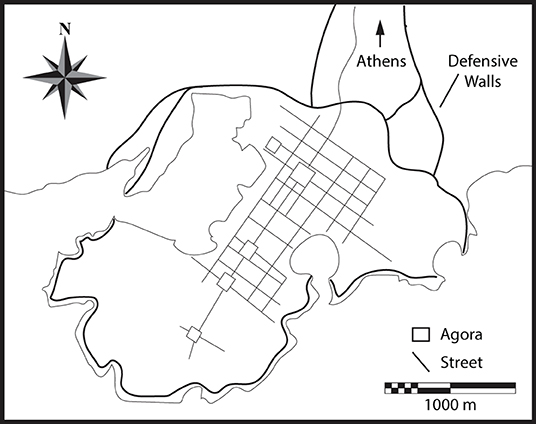

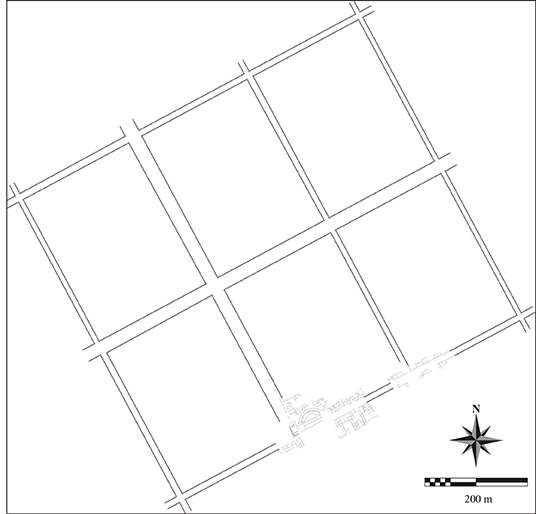

Our best evidence for democratic landscapes comes from town planning attributed to Hippodamus (Castagnoli, 1971). In the limited writings of Hippodamus that have come down to present, we know that he consciously linked town planning with political strategies and that he considered establishing order and standardization in town planning as key aspect of democratic processes (see Paden, 2001; Fleming, 2002; Mazza, 2009). Formally, Hippodamus divided urban space into public, private, and sacred and considered respect for these divisions key to establishing the social order necessary for democracy to flourish (Mazza, 2009). He also, in practice, apparently merged agorai and gridded street plans into the settlements that he planned (Paden, 2001, p. 43). Thus, agorai and orthogonal road systems became the recognized materialization of democracy in urban landscapes (Paden, 2001; Fleming, 2002; Mazza, 2009). The best examples of this style of town planning are visible in the construction of the Athenian port at Piraeus (we note that the palimpsest of Hippodamus' plan is still visible today in the modern city) and the colony of Thurii (known from archaeological excavations), which was promoted by Perikles as the ideal example of democratic order (Figures 1, 2) (Dicks, 1968; Paden, 2001; Fleming, 2002). Either consciously or unconsciously, the combination of agorai and orthogonal streets projected an ideological abstraction of order, freedom, and equality, because these planned towns ordered private, public, and sacred space, provided equal access to free spaces, and cut up residential spaces into highly standardized and uniform house lots that limited the degree to which any wealthy individuals could signal their importance through monumental residential architecture (Paden, 2001; Whitley, 2001, p. 359; Mazza, 2009). In both cases, we see the construction of multiple open spaces, linked with sacred precepts through temple construction where major streets crossed. This pattern is clearly visible in Piraeus with a line of agorai running along the central avenue, which formed the terminus of the highway that linked the port with Athens (Dicks, 1968: Figure 2). Temples and/or public buildings were constructed in several of these squares, as well as theaters at other important intersections (Figure 1). Thus, the Hippodamian city became a materialization of many aspects of Athenian democratic philosophy relating to equality.

Figure 1. Map of Ancient Piraeus (Adapted from Dicks, 1968: Figure 2 and Google Earth).

Figure 2. Map of Ancient Thurii (Adapted from Greco, 2009, Figure 9.4 and Google Earth).

The pre-Hispanic, indigenous state of Tlaxcallan (C.E. 1300–1521), located in central Mexico about 100 km east of the Basin of Mexico (the large interior drainage basin that surrounds modern Mexico City), we argue, provides analogs to the political participation, isonomia, isegoria, and built environment we described for Athenian democracy. Tlaxcallan was a small, independent state, comparable in scale to Classical Attica, that was founded around 1300/1400 based on radiocarbon dating and ceramic cross ties. Previously, we argued that Tlaxcallan emerged in response to imperial threats emanating from Aztec polities centered in the Basin of Mexico (Fargher et al., 2010). While city-states in the vicinity of Tlaxcallan fell under the expanding domination of the Aztec Triple Alliance (known colloquially as the Aztec Empire), especially after 1428, Tlaxcaltecan political architects instituted or strengthened collective political strategies, building a multiethnic confederation of settlements spread over ~2,500 km2, with a population of ~250,000 to 300,000. This confederation was able to withstand onslaught after onslaught by the Aztec and remained independent (Fargher et al., 2010, 2011).

The political integration of the Tlaxcaltecan confederation resulted in the emergence of a large, dense urban occupation at the newly founded eponymous city of Tlaxcallan. This city grew in an area of unoccupied hilltops to become a terraced city covering ~4.5 km2 and with a population of ~35,000 by the time of the Spanish Conquest in 1521 (Fargher et al., 2011). Surprisingly, although the city of Tlaxcallan was the largest, most important settlement in Tlaxcaltecan territory, it did not house the political capital (Figure 3). Tlaxcaltecan political architects instead built a disembedded capital on an isolated hilltop called Tizatlan, about 1 km beyond the limits of the city (Fargher et al., 2011). In what follows, we first describe Tlaxcaltecan political philosophy as it would have been in 1519 when Cortés and the other Conquistadores arrived in Tlaxcallan, and then examine the materialization of this philosophy through the results of various archaeological projects in Tlaxcallan and Tizatlan.

When Cortés arrived in Tlaxcallan he was struck by the political formation that he encountered. In his second letter to the Spanish Crown, he reports that the city was approximately the scale of Granada when it was retaken from the Moors (Cortés, 1963). He also points out that it did not have an overarching ruler, a king, and the closest political analogies to it in 16th century European political experience were the Italian republics (señorías), such as Venice, Genoa, and Pisa, among others (Cortés, 1963). Based on his descriptions and reports, along with those of other Conquistadores and early Colonial period documents and chronicles, we have been able to reconstruct Tlaxcaltecan political architecture prior to significant changes brought about by Spanish intervention (e.g., Fargher et al., 2010, 2011; Fargher, 2022).

Pre-Contact Tlaxcaltecan society was divided among three principal status categories: pilli (roughly translatable as “nobles”), an intermediate status (teixhuahau), and a peasantry (macehualli) (Gibson, 1952; Anguiano and Chapa, 1976). Interestingly, the indigenous (Nahua) term typically used for “slave” does not occur in Tlaxcaltecan documents, and another obscure term than may have referred to some type of attached/dependent or only part-free laborer is only rarely used (Anguiano and Chapa, 1976). Nobles headed four principal “house” types - teccalli (“lord's houses”), picalli (“noble houses”), huehuecalli (“old houses”), and yaotequihucali (“warrior's houses”) (Gibson, 1952; Anguiano and Chapa, 1976; see also Castillo Farreras, 1972). Surprisingly, only two of these house categories and their political positions were hereditary, picalli and huehuecalli. The other two, teccalli (the highest household rank in the Tlaxcaltecan state) and yaotequihucali were bestowed on individuals, from any social status, based on merit acquired through exceptional service to the state (Fargher et al., 2010). The most common pathway was through decorated military service, but religious service and providing wise “council” in the assembly were other pathways ( Motolinía, 1950; Muñoz Camargo's, 1986). Importantly, even the hereditary heads of picalli and huehuecalli had to provide service, or they would lose their status (Fargher et al., 2010; Fargher, 2022). Individuals that had lost their status as nobles were called pillaquistiltin; the widespread use of this term in early Colonial Tlaxcaltecan documents indicates that downward social mobility was very common (see Anguiano and Chapa, 1976). Based on early Colonial census data, Fargher (2022) estimated that these four categories consisted of ~4,000 households (of a total of ~28,000 to 29,000 households). Thus, the heads of these 4,000 households would have served in some capacity as political officials (e.g., tax collectors, corvée directors, military leaders, police, judges, legislators, administrative heads, etc.).

We have argued previously that the highest-level political officials in Tlaxcallan, tecuictli (holders of teccalli), formed a ruling council or senate consisting of somewhere between 50 and 200 members (Fargher et al., 2010). This body had the power to act as a supreme court, to declare war and peace, propose alliances, appoint, monitor, and punish political officials including tecuictli, and appoint ambassadors. Decisions were made through speechmaking and debate until a consensus was reached. Membership on this council was earned, and after elevation to the title of tecuictli, an individual was assigned an administrative/revenue producing district called a teccalli (lord's house). These districts provided revenue to the state and paid the salaries of the tecuictli. However, the lands associated with a teccalli remained state property and revenue flows were closely monitored. The early Colonial period mestizo-Tlaxcalteca chronicler Muñoz Camargo's (1986) noted that if a tecuictli accumulated too much wealth, he was executed and his properties and other assets were redistributed (it is unclear from Muñoz Camargo's writings if these actions were state sanction or an act of the people).

Diverse documents indicate that the teccalli districts were subdivided into smaller administrative units called tlaca (Fargher et al., 2010, 2011; Fargher, 2022). For example, an early Colonial period will from Ocotelulco (a district of the city of Tlaxcallan), indicates that this urban district was subdivided into five tlaca (or wards/neighborhoods)—Tlamahuco, Chimalpa, Contlantzingo, Tecpan, and Cuitlixco (García Sánchez, 2005, p. 113). Apparently, these wards were assigned to lower-level political officials such as pilli (heads of picalli) or yaotequihua (heads of yaotequihucali) (Muñoz Camargo's, 1986). Importantly, one pathway to tecuictli status, as we mentioned, was through providing valuable advice or council, which would indicate that these political officials and even other individuals attended and participated in the ruling council's sessions. Thus, for certain important decisions like declaring war, broader general assemblies including thousands of participants (e.g., lower-level administrators and possibly teixhuahau and macehualli) may have been called.

The documents also indicate that to Tlaxcaltecans, legal equality, comparable to the Greek concept of isonomia, was an important dimension of their collective political strategies. For example, Fray Toribio de Benavente Motolinía, (1971, p. 321), a Spanish friar who was among the first Europeans to live in Tlaxcallan, sometime around 1532–1533, detailed how no Tlaxcalteca was above justice and the law was applied equally to all. Especially visible in the chronicles is a focus on demonstrating that nobles did not receive special or distinctive treatment with respect to the law as compared with commoners. In one case, a high-ranking individual (the brother of Maxixcatzin, who was one of the most prominent politicians in 1519) was brought to trial for adultery and convicted (de Zorita, 1994, see also Motolinía, 1971, p. 321). Importantly, neither his status nor his brother's influence protected him from being sentenced to death. In another incident, Xicotencatl el Mozo (the younger), among the most important and successful military leaders of his day and a tecuictli, was indicted and convicted of treason when he defied the Tlaxcaltecan-Spanish alliance and attacked Cortés and his men (cf. the failure to convict Kimon of corruption). Interestingly, these high crimes are described as having been tried in the Tlaxcaltecan “senate” and the tecuictli acted as jurors (cf. Athenian juries).

We also note that Tlaxcaltecan citizenship was extended across diverse ethnic groups (e.g., Otomí and Pinome, etc.) and not limited to the dominant Nahuas (Fargher et al., 2010). This extension included the incorporation of immigrants, especially Otomí refugees fleeing oppression in the Basin of Mexico (cf. Athenian treatment of metics). This is not to say that some temporary residents or ambassadors did not retain their distinctive political and ethnic identities while residing in Tlaxcallan. We also know from Muñoz Camargo's (1986) writing that tecuictli-status was extended to important Otomí leaders, including immigrants, based on service. In at least one case, the Aztec Triple Alliance attempted to bribe Otomí-Tlaxcalteca leaders to turn against Nahua-Tlaxcaltecas. These Otomí refused and proudly affirmed that they could not be bribed because they were Tlaxcalteca and could not turn on themselves (Muñoz Camargo's, 1986). We also know that the most important military hero of the Tlaxcaltecan state was an Otomí named Tlahuicole. Tlahuicole was the most highly revered Tlaxcaltecan citizen at the time of contact with Cortés, even by Nahua-Tlaxcaltecas. To put this into perspective, we note that ethnic conflicts and oppression of minority ethnic groups, such as the Otomí, was widespread in other parts of central Mexico at this time.

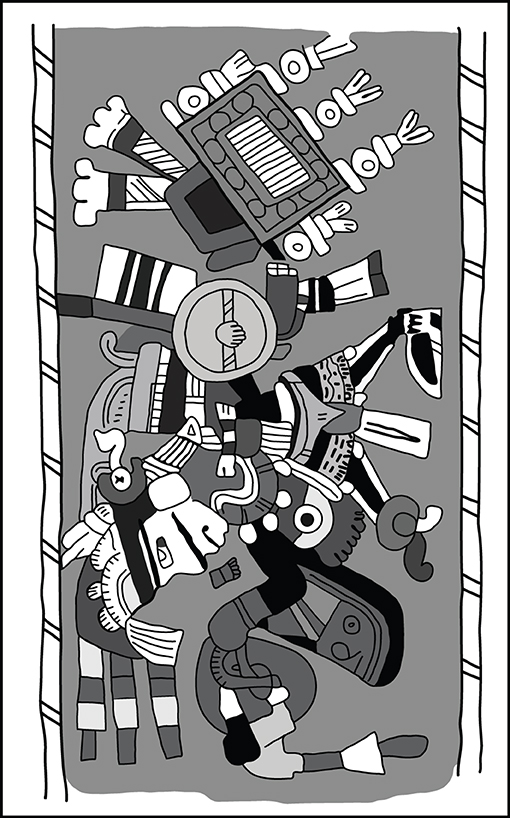

The Tlaxcaltecas revered Tezcatlipoca (Smoking Mirror) as their principal deity (Figure 4). According to indigenous (Nahua) mythic history, Tezcatlipoca is a powerful trickster that continually antagonized the god Quetzalcoatl, a mythic king and founder of royal Nahua lineages, and by extension the hereditary nobility and especially monarchs (Nicholson, 1971, 2001; Mónaco, 1998). As part of the mythic history of a lost kingdom called Tollan, Tezcatlipoca had a series of encounters with Quetzalcoatl, as well as other rulers, that illustrate key egalitarian aspects of Nahua morals (cf. Greek concepts of isonomia). In one encounter, Tezcatlipoca urged Quetzalcoatl to look into his magic mirror (Nicholson, 1971, 2001; Mónaco, 1998). When Quetzalcoatl looked, he was horrified by his reflection. The obsidian mirror had revealed his true nature, as a corrupt and wicked ruler. In another encounter, Tezcatlipoca encouraged Quetzalcoatl to go on a drinking binge (summarized in Nicholson, 2001, p. 47). Quetzalcoatl, intoxicated, made his sister drink with him, and then fornicated with her. Finally confronted with these transgressions and unable to manage his guilt, Quetzalcoatl fled his kingdom. Tezcatlipoca also influenced Huemac, a warrior and another ruler of Tollan. In this incident, Tezcatlipoca convinced Huemac to engage in human sacrifice and to include his sons and heirs in these rituals (Mónaco, 1998, p. 142–146). By sacrificing his heirs, Huemac was transformed into the god Atecpanecatl, the enemy of Quetzalcoatl and the destroyer of royal lineages (Mónaco, 1998, p. 144).

Figure 4. Tezcatlipoca, Mural A, Tizatlan (Adapted from Noguera, 1929: p. l.1).

Tezcatlipoca, with his special vision and magic obsidian mirror, possessed the ability to see the true nature of individuals, regardless of ascribed status, or even entire societies. As we pointed out previously, “We relate this kind of visual wisdom to the ability to see the potential for virtue in persons regardless of social standing, including the idea that success can be the product of achievement, not just noble birth …” (Fargher et al., 2010, p. 241). Accordingly, Tezcatlipoca was feared by the hereditary nobility among the Aztecs because he would appear and change the fortunes of the rich, demoting them to commoner status, as well as promote macehualli to the highest levels of society, thus blurring the distinction between elite and commoner. His egalitarian ideals (similar to isonomia) were played out in his diverse personifications, including as the god Moyocoyatzin (he who creates himself), as the god Ixquimilli (as a judge who symbolized blind justice), and as the god Tepeyollotl, the heart of the mountain, a jaguar figure linked to warriors and sacrifice through military service (Figure 5) (Seler, 1963, p. 112–113; Heyden, 1991, p. 189). Consequently, linking the state with this deity made equality a sacred political ideal that provided supernatural justification for the participation of individuals from any social status, including commoners, in the political system including serving as chief governing officials (cf. Hansen, 1999, p. 81–85). Moreover, as part of this ideology, both highly placed political officials and other individuals, including commoners, were afforded the right to speak before the governing council. Tezcatlipoca's egalitarian morals (cf. isonomia) promoted freedom of speech (cf. isegoria) as a fundamental tenant of Tlaxcaltecan political philosophy. It is of interest for purposes of this paper to note the similarities between Tezcatlipoca and the Classical Athenian god Dionysus, following authors such as (Connor, 1996, p. 222) who argued that: “Dionysiac worship…inverts, temporarily, the norms and practices of aristocratic society [and makes it possible]…to think about an alternative community, one open to all, where status differentiation can be limited or eliminated, and where speech can be truly free” (cf. Blanton with Fargher, 2016, p. 231–233).

From the study of the architectural remains of Tlaxcallan and Tizatlan (Figure 6), we find patterning consistent with both the political strategies and ideologies we have described. Our mapping project (see Fargher et al., 2011) documented that the city of Tlaxcallan was divided into three principal districts (teccalli) that were in turn subdivided into ~20 neighborhoods (tlaca). Each district and each tlaca was centered on a plaza bounded by a single temple-mound or multiple buildings. These plazas range in size from 500 to 12,000 m2, but no plaza stands out as a central place in the city. Analysis of artifacts recovered from plaza-mound complexes indicates that commercial, political, and sacred activities were hosted in them. The plazas were highly accessible, allowing for intermingling and collective participation in a range of everyday, special, and sacred activities. We imagine (as Vlassopoulos, 2007, p. 42 does for the agora) that Tlaxcaltecans discussed, argued over, and proposed policies in response to current political policies and tidings from other lands. Importantly, political officials were required to be present in the plazas, especially during important activities, for example, during market days to provide security, during religious rituals, and during significant political events like induction ceremonies (Cortés, 1963; Motolinía, 1971; Muñoz Camargo's, 1986). In an essential example, individuals elected to high-level governing positions were required to appear before the people in the plazas (Motolinía, 1971, p. 339–343). During this rite of reversal, the people stripped the candidate of his clothes, shoved, slapped, and hit him, and hurled insults upon him, testing the candidate's ability to maintain his composure under extreme stress. The rite also reminded the individual that regardless of his status he was a servant of the people. These plazas, like the Athenian agora, formed the backbone of social, political, economic, and religious life of Tlaxcaltecan society.

The individuals that frequented these free spaces lived in densely packed residential terraces that covered the hillslopes around the plazas (Figure 6). These terraces are extremely uniform ranging in size from about 500 to about 3,000 m2, with a median area of 1,700 m2 (Fargher et al., 2011). Our excavations on several terraces, plus excavations by other projects, have demonstrated that the largest ones were sub-divided between domestic and public areas or among multiple households (Fargher et al., 2020). Such use of terrace space means that the largest house lots in the city covered no more than about 2,000 m2 and the houses of even the richest members of Tlaxcaltecan society would have been well-under 1,000 m2. These data suggest a Gini index for residential land of ~0.23. In fact, the largest house excavated to date only had about 265 m2 of roofed space (Figure 7) (Fargher et al., 2020). Comparatively, the richest members of neighboring pre-Hispanic societies in Central Mexico and Oaxaca (Aztecs, Mixtecs, Zapotecs, etc.) lived in sumptuous palaces, often elevated on platforms, covering 8,000–20,000 m2 (Fargher et al., 2020). Furthermore, flooring, house foundations, and portable material wealth were highly uniform among households within the site. These data indicate that within the city of Tlaxcallan, political policy and ideology were materialized in a high degree of economic equality, a result consistent with descriptions by the Conquistadores that indicate that even the residence of Maxixcatzin, considered to be among Tlaxcallan's wealthiest citizens, was extremely modest (Fargher, 2022). Qualitative comparison with Aztec villages and Teotihuacan, shows that Tlaxcallan was more economically equal than both cases.

On a hilltop within a municipality now called Tizatlan, Tlaxcala, the Tlaxcalteca built a massive civic-ceremonial complex on a terrace or platform (Fargher et al., 2011). This complex covered at least 16,000 m2 and possibly as much as 24,000 m2 (modern construction has destroyed the northeastern boundary of the complex) (estimated using Google Earth Pro). This space apparently consisted of an open plaza covering at least 10,000 m2, as well as a religious sanctuary consisting of a number of small temples and auxiliary structures built around a patio. Like the Pnyx Hill, this complex acted as the most important political space in the Tlaxcaltecan state. It was a neutral location where the ruling council met to discuss and vote on important issues. The principal altar here depicts Tezcatlipoca along with other important deities (Caso, 1927), sanctifying the democratic political processes that took place there. Importantly, the scale of this complex indicates that many more individuals than just the 50–250 tecuictli met in this space for politico-religious ceremonies. The space was built to hold thousands of individuals. As we noted earlier, one pathway to tecuictli status involved providing sound advice or recommendations to the ruling council. Thus, the documentary and archaeological data indicate that many more individuals than just the tecuictli, possibly as any as 4,000 or more individuals, attended the most important assemblies and participated in their discussions.

We think the data presented here indicate an extremely high degree of coherence between the political philosophies and policies of Classical Athens and Late pre-Hispanic Tlaxcallan, despite variation in the particular institutions and structures developed to materialize them. Both states upheld a philosophy of legal equality (isonomia in Greek terms) and developed structures and institutions that sought to make it a reality for all citizens. While neither state created a legal-rights utopia, we think the Tlaxcaltecan state was much more thorough in its legal policies, given the very limited role of slavery and the full incorporation of diverse ethnic groups and immigrants into its political and legal systems (Motolinía, 1950; Gibson, 1952; Anguiano and Chapa, 1976; Muñoz Camargo's, 1986; Aguilera, 1991a,b). All political officials were carefully monitored, and malfeasance was punished. Moreover, there is evidence for specialized judicial officials, as well as formal police (Cortés, 1963), which suggested that civil and criminal justice systems in Tlaxcallan were comparable to those of neighboring Texcoco, and thus among the most sophisticated legal systems in the premodern world (see Offner, 1983). We also have documentary evidence of even the highest level and most respected political figures being punished, following due process, for violating norms or orders issued by the ruling assembly (Cortés, 1963). In terms of political equality, we think an Athenian would have been highly impressed by the degree and nature of citizen participation in Tlaxcallan's government. Again, we think Tlaxcallan exceeded Athens in this area. No citizen was excluded from participating fully at all levels of the government, including being elected to tecuictli status. While the pathway was different, through meritorious service and election by the council to achieved status in Tlaxcallan, vs. election at the deme level and selection by lot, the outcome was more egalitarian in Tlaxcallan when we consider that sub-hoplites were excluded from very high office in Athens during most if not all of the democratic period.

From the vantage of economic equality, Tlaxcallan far exceeded Athens. The degree of social inequality in the city of Tlaxcallan was compressed to an unprecedented degree as compared with other pre-modern states we are aware of in Mesoamerica or elsewhere. Our surveys and excavations demonstrate that the richest and most important Tlaxcaltecans resided in domiciles that were no more than 200–400 m2 for the most part while the poorest residents resided in dwellings that were 50–150 m2 (Fargher et al., 2010, 2011, 2020; Marino et al., 2020). Rich or poor, houses were constructed with stone foundations and adobe/cut tepetate (hard subsoil) block walls. Exterior foundations stones were faced, but interiors were rough. Floors were packed earth with whitewash. All residential space was uniformly organized around two spaces, a patio bounded by roofed rooms and an open area adjacent to the dwelling. Portable material wealth, including codex polychrome pottery and imported obsidian, was uniformly distributed among all households. In simple terms, there are no material identifiers that distinguish rich and poor Tlaxcaltecans within the city. Quantitatively, rough measures using the Gini coefficient indicate that Tlaxcallan was more economically egalitarian that Athens. To contextualize this, qualitatively Tlaxcallan equality far exceeded that of Teotihuacan, the most equalitarian case in the Kohler et al. (2017) database. As we pointed out previously (Fargher et al., 2020), these findings challenge the core of Eurocentric theory on non-Western, pre-modern states.

Free speech (comparable to Greek isegoria) was a fundamental aspect of Tlaxcaltecan political policy and practice. Not only was free speech exercised by all citizens in Tlaxcallan, but it was also the basis for political decision-making during assemblies of the governing council. During legislative sessions, diverse individuals attending assemblies would propose various policies, strategies, or projects (Muñoz Camargo's, 1986; Cervantes de Salazar, 1991). These proposals were debated until consensus was reached and proposals became law or policy. According to Muñoz Camargo's (1986), individuals that were not among the highest titled political officials provided advice or council during these sessions. Thus, they would have made proposals or argued for or against other proposals. We also believe that free political discussion was part of quotidian activities in the city of Tlaxcallan's numerous plazas, on market days as well as during other political and religious gatherings. These discussions would have included, as well as targeted, both local and central political figures. During specific political and ritual occasions, the people would have been able to exercise their right to make known their discontent with immoral/dishonest/corrupt political officials, as well as to punish them in various ways if they were unsatisfied with other measures implemented by the state.

In the city's built environment, much of the order envisioned by Hippodamian urban planning that was considered a fundamental aspect of democratic processes is visible. First, Tlaxcaltecan urban design materialized a division among private, public, and sacred space. Public spaces served political and economic functions and were sanctified through the construction of ritual buildings adjacent to them. Much like the Athenian Agora, Tlaxcaltecan plazas were places where politics, religion, and commerce intermixed. They were the “free spaces” where everyone participated in politics. As part of indigenous cultural traditions, women participated in market transactions throughout pre-Hispanic central Mexico (Berdan, 1975). So, plazas were foundational places for free speech (cf. isegoria), where political discussions and debates crossed gender lines. Second, much like Hippodamian design of Piraeus, plazas were distributed throughout the city of Tlaxcallan (Fargher et al., 2011: Figure 1). These plazas were the nodes of a road system that integrated the city. Moreover, neighborhood-scale plazas would have played a role akin to the agorai and Dionysian theaters in rural (and possibly) urban demes, as the focal point of sub-polity (local) scale political action. Third, much like the gridded road system in Athenian planned settlements, like Piraeus and Thurii, Tlaxcallan's residential terraces were highly standardized, resulting in a highly ordered and uniform urban landscape (Fargher et al., 2011). The uniformity of domestic space would have contributed strongly to ideologies of shared identity and equality that were crucial to equality and social integration that provided Tlaxcallan the capacity and will to deploy an essentially unstoppable homeland defense (Fargher et al., 2010).

While we do not imply that pre-Hispanic Tlaxcaltecans would have conceptualized their political philosophy in terms of isonomia and isegoria (or that Nahua equivalents existed in C.E. 1519), we argue that there were important points of comparability of these philosophies, political institutions, and urban landscapes. Thus, we can no longer discuss the global origins of democracy and good government while excluding non-Western political change. We also suggest that in philosophy and in practice, a Classical Athenian would conceptualize Tlaxcaltecan government as more comparable to demokratia than to either tyranny or oligarchy. If the Athenian were a conservative pundit, he would reject the strongly egalitarian aspects of Tlaxcaltecan politics, especially the elevation of commoners to the highest political offices. Conversely, a radical thete would have praised the Tlaxcaltecas for widespread political participation, as well as their unprecedented degree of economic equality. While neither our Classical Greeks nor pre-Hispanic Tlaxcaltecan political actors would have found it out of the ordinary, we note that lack of institutionalized political participation by women was a major shortcoming of both cases.

LF developed the article concept and was responsible for writing original draft. LF, RB, and VH participated in writing review and editing and supervised the Tlaxcallan projects and acquired funding. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

FAMSI (Project No. 06082), National Geographic (Grant #8008-06), and the US National Science Foundation (BCS 0809643) provided funding for the archaeological survey of Tlaxcallan. The US National Science Foundation (BCS 1450630) and Mexico's Conacyt (CB-2014-236004) provided funding for our excavations at Tlaxcallan.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbas, S. R. (2020). Beyond Civilization and History. New York, NY: Amazon. Available online at: https://philarchive.org/archive/ABBBCAv1 (accessed October 2, 2022).

Aguilera, C. (1991a). “Los Otomíes Defensores de Fronteras: El Caso de Tlaxcala,” in Tlaxcala: Textos de su Historia, Tomo 4: Los Origenes: Antropologia e Historia, eds C. Aguilera, and A. Ríos (Tlaxcala: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes y Gobierno del Estado de Tlaxcala), 472–485.

Aguilera, C. (1991b). Tlaxcala: Textos de su Historia, Tomo 5: Los Origenes: Antropologia e Historia. Tlaxcala: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes y Gobierno Tlaxcala.

Ahn, T. K., and Ostrom, E. (2009). “The meaning of social capital and its link to collective action,” in Handbook of Social Capital, eds D. Castiglione, J.W. van Deth, and G. Wolleb (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 70–100.

Anguiano, M., and Chapa, M. (1976). “Estratificación Social en Tlaxcala Durante el Siglo XVI,” in Estratificación Social en la Mesoamérica Prehispánica, eds P. Carrasco, and J. Broda (Mexico City: Centro de Investigaciones Superiores, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia), 118–156.

Apostolopoulos, G., and Kapetanios, A. (2021). Geophysical investigation, in a regional and local mode, at Thorikos Valley, Attica, Greece, trying to answer archaeological questions. Archaeol. Prospect. 28, 435–452. doi: 10.1002/arp.1814

Berdan, F. M. (1975). Trade, Tribute and Market in the Aztec Empire (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation). Department of Anthropology, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin.

Berman, S. (2007). How democracies emerge: lessons from Europe. J. Demo 18, 28–41. doi: 10.1353/jod.2007.0000

Blanton, R. E. (2019). Review of James C. Scott, against the grain: a deep history of the earliest states. Rev. Policy 81, 516–518. doi: 10.1017/S0034670519000068

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2008). Collective Action in the Formation of Pre-Modern States. New York, NY: Springer.

Blanton, R. E., Fargher, L. F., Feinman, G. M., and Kowalewski, S. A. (2021). The fiscal economy of good government: past and present. Curr. Anthropol. 62, 77–100. doi: 10.1086/713286

Blanton, R. E., Feinman, G. M., Kowalewski, S. A., and Fargher, L. F. (2020). Moral collapse and state failure: a view from the past. Front. Polit. Sci. 2:568704. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.568704

Blanton, R. E., and with Fargher, L. F. (2016). How Humans Cooperate: Confronting the Challenges of Collective Action. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Carballo, D. M., and Feinman, G. M. (2016). Cooperation, collective action, and the archeology of large-scale societies. Evol. Anthropol. 25, 288–296. doi: 10.1002/evan.21506

Castillo Farreras, V. M. (1972). Estructura Económica de la Sociedad Mexicana Según las Fuentes Documentales. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas.

Cervantes de Salazar, F. (1991). “Crónica de la Nueva Espana,” in Tlaxcala: Textos de su Historia, Tomo 6: Siglo XVI, eds C. Sempat Assadourian, and A. Martinez Baracs (Tlaxcala: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes y Gobierno del Estado de Tlaxcala), 30–36, 50–53, 60–64, 85, 86, 88–95, 98–102, 107, 108, 110–113.

Chou, M., and Beausoleil, E. (2015). Non-Western theories of democracy. Demo Theory 2, 1–7. doi: 10.3167/dt.2015.020201

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Soc. 94, S95–S120. doi: 10.1086/228943

Connor, R. W. (1996). “Civil society, dionysiac festival, and the athenian democracy,” in Demokratia: A Conversation on Democracies, Ancient and Modern, eds J. Ober, and C. W. Hedrick (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 217–226.

Coppedge, M. (1999). Thickening thin concepts and theories: combining large N and small in comparative politics. Comp. Politics 31, 465–476. doi: 10.2307/422240

Daly, J. (2019). How Europe Made the Modern World: Creating the Great Divergence. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

de Zorita, A. (1994). Life and Labor in Ancient Mexico: The Brief and Summary Relation of the Lords of New Spain. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Dicks, T. R. B. (1968). Piraeus: the port of Athens. Town Plan Rev. 39, 140–148. doi: 10.3828/tpr.39.2.765278g16442814j

Duindam, J. (2018). “Pre-modern power elites: princes, courts, intermediaries,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Political Elites, eds H. Best, and J Higley (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 161–179.

Economou, E. M., and Kyriazis, N. C. (2017). The emergence and the evolution of property rights in ancient Greece. J. Inst. Econ. 13, 53–77. doi: 10.1017/S1744137416000205

Fargher, L. F. (2022). “El Malinche and Tlaxcallan: a field guide to taking down democracy,” in Archaeology and Material Culture of the Spanish Invasion of Mesoamerica and Forging of New Spain, eds D. Carballo, and A. López Corral (Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, forthcoming).

Fargher, L. F., Antorcha-Pedemonte, R. R., Heredia Espinoza, V. Y., Blanton, R. E., López Corral, A., Cook, R. A., et al. (2020). Wealth inequality, social stratification, and the built environment in late prehispanic highland Mexico: a comparative analysis with special emphasis on Tlaxcallan. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 58, 101176. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2020.101176

Fargher, L. F., and Blanton, R. E. (2021). “peasants, agricultural intensification, and collective action in premodern states,” in Power From Below in Premodern Societies: The Dynamics of Political Complexity in the Archaeological Record, eds T. L. Thurston, and M. Fernández-Götz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 157–174.

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., and Heredia Espinoza, V. Y. (2010). Egalitarian ideology and political power in prehispanic Central Mexico: the Case of Tlaxcallan. Lat. Am. Antiq. 21, 227–251. doi: 10.7183/1045-6635.21.3.227

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., Heredia Espinoza, V. Y., Millhauser, J., Xiuhtecutli, N., and Overholtzer, L. (2011). Tlaxcallan: the archaeology of an ancient republic in the new world. Antiquity 85, 172–186. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X0006751X

Feinman, G. M., and Carballo, D. M. (2018). Collaborative and competitive strategies in the variability and resiliency of large-scale societies in mesoamerica. Econ. Anthropol. 5, 7–19. doi: 10.1002/sea2.12098

Fleming, D. (2002). The streets of Thurii: discourse, democracy, and design in the classical polis. Rhetor. Soc. Q. 32, 5–32. doi: 10.1080/02773940209391232

García Sánchez, M. A. (2005). Los que se Quedan: Las Familias de los Difuntos en la Región de Ocotelulco, Tlaxcala, 1572–1673. Un Estudio Etnohistórico con Base en Testamentos Indígenas (Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation), CIESAS, Mexico City.

Goušchin, V. (1999). Pisistratus' Leadership in AP 13.4 and the Establishment of the Tyranny of 561/60 BC 1. Class Q. 49, 14–23. doi: 10.1093/cq/49.1.14

Graeber, D., and Wengrow, D. (2021). The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. London: Penguin.

Greco, E. A. (2009). “The urban plan of Thourioi: literary sources and archaeological evidence for a Hippodamian City,” in: Inside the City in the Greek World: Studies of Urbanism from the Bronze Age to the Hellenistic Period, eds S. Owen, and L. Preston (Oxford: Oxbow Books), 108–117.

Hadenius, A., and Teorell, J. (2005). Assessing Alternative Indices of Democracy. C&M Working Papers, IPSA. Available online at: https://www.concepts-methods.org/Files/WorkingPaper/PC%206%20Hadenius%20Teorell.pdf (accessed February 25, 2022.)

Hansen, M. H. (1999). The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes: Structure, Principles, and Ideology. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Heyden, D. (1991). “Dryness before the rains: toxcatl and tezcatlipoca,” in Aztec Ceremonial Landscapes, ed D. Carrasco (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado), 188–204.

Holland-Lulewicz, J., Thompson, V. D., Birch, J., and Grier, C. (2022). Keystone institutions of democratic governance across indigenous North America. Front. Polit, Sci., in press.

Jones, N. F. (2011). Rural Athens Under the Democracy. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Kohler, T. A., Smith, M. E., Bogaard, A., Feinman, G. M., Peterson, C. E., Betzenhauser, A., et al. (2017). Greater post-neolithic wealth disparities in Eurasia than in North America and mesoamerica. Nature 551, 619–622. doi: 10.1038/nature24646

Kourouniotes, K., and Thompson, H. A. (1932). The Pnyx in Athens. Hesperia J. Am. Sch. Class Stud. Athens 1, 90–217. doi: 10.2307/146476

Kron, G. (2011). The distribution of wealth at Athens in comparative perspective. Zeitschrift Papyrol. Epigraphik 2011, 129–138.

Mainwaring, S., and Bizzarro, F. (2019). The fates of third-wave democracies. J. Demo 30, 99–113. doi: 10.1353/jod.2019.0008

Marino, M. D., Fargher, L. F., Meissner, N. J., Johnson, L. R. M., Blanton, R. E., and Heredia Espinoza, V. Y. (2020). Exchange systems in late postclassic mesoamerica: comparing open and restricted markets at Tlaxcallan, Mexico, and Santa Rita Corozal, Belize. Lat. Am. Antiq. 31, 780–799. doi: 10.1017/laq.2020.69

Mazza, L. (2009). Plan and constitution: Aristotle's hippodamus: towards an 'ostensive' definition of spatial planning. Town Plan. Rev. 80,113–141. doi: 10.3828/tpr.80.2.2

McCannon, B. C. (2010). The median juror and the trial of socrates. Euro J. Polit. Econ. 26, 533–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2010.03.005

Millon, R. (1973). Urbanization at Teotihuac?n, Mexico, Vol. 1: The Teotihuac?n Map. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Morris, I. (1998). “Archaeology as a kind of anthropology (a response to David Small),” in Democracy 2500? Questions and Challenges, eds I. Morris, and K. Raaflaub (Dubuque: Kendal/Hunt), 229–239.

Motolinía, T. (1971). Memoriales o Libro de las Cosas de la Nueva Espana y de los Naturales de Ella. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas.

Munck, G. L., and Verkuilen, J. (2002). Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: evaluating alternative indices. Comp. Polit. Stud 35, 5–34. doi: 10.1177/001041400203500101

Nicholson, H. B. (1971). “Religion in pre-hispanic central Mexico,” in Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 10, eds R. Wauchope, G.F. Ekholm, and I. Bernal (Austin: University of Texas Press), 395–446.

Nicholson, H. B. (2001). Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl: The Once and Future Lord of the Toltecs. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Noguera, E. (1929). “Los Altares de Sacrificio de Tizatlan, Tlaxcala,” in Ruinas de Tizatlan, Tlaxcala, Vol. 15. (Mexico City: Publicaciones de a Secretaría de Educación Publica, Talleres Gráficos de la Nación), 24–64.

North, D.C. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ober, J. (2007). “I besieged that man”: democracy's revolutionary start,” in Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece, eds K. A. Raaflaub, J. Ober, and R. Wallace (Berkeley: University of California Press), 83–104.

Paden, R. (2001). The two professions of Hippodamus of Miletus. Philos. Geogr. 4, 25–48. doi: 10.1080/10903770124644

Paga, J. (2010). Mapping politics: an investigation of deme theatres in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. Hesper 79, 351–384. doi: 10.2972/hesp.79.3.351

Pomeroy, S. B., Burstein, S. M., Pomeroy, B. D., Donlan, W., and Roberts, J. T. (2012). Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Putterman, L. (2018). Democratic, accountable states are impossible without “behavioral” humans. Ann. Pub. Coop. Econ. 89, 251–258. doi: 10.1111/apce.12198

Raaflaub, K. A. (1996). Equalities and Inequalities in Athenian Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Raaflaub, K. A. (2007). “The breakthrough of Demokratia in mid-fifth-century Athens,” in Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece, eds K. A. Raaflaub, J. Ober, and R. Wallace (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), 105–154.

Rothstein, B. (2011). The Quality of Government: Corruption, Social Trust, and Inequality in International Perspective. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Scott, J. C. (2017). Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Thompson, W. E. (1971). The Deme in Kleisthenes' reforms. Symbol. Oslo 46, 72–79. doi: 10.1080/00397677108590627

Tilly, C. (1975). “Western state-making and theories of political transformation,” in The Formation of National States in Western Europe, ed C. Tilly (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 601–638.

Vlassopoulos, K. (2007). Free spaces: identity, experience and democracy in classical Athens. Class Q. 57, 33–52. doi: 10.1017/S0009838807000031

Wallace, R. (2007). “Revolutions and a new order in Solonian Athens and Archaic Greece,” in Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece, eds K. A. Raaflaub, J. Ober, and R. Wallace (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), 49–82.

Weede, E. (2020). Geopolitics, economic freedom and economic performance. Econ. Voice 17:20190036. doi: 10.1515/ev-2019-0036

Whitehead, D. (2014). The Demes of Attica, 508/7-ca. 250 BC: A Political and Social Study. New Haven, CT: Princeton University Press.

Keywords: Athens, demokratia, good government, isonomia, isegoria, Tlaxcallan, Eurocentrism

Citation: Fargher LF, Blanton RE and Heredia Espinoza VY (2022) Collective Action, Good Government, and Democracy in Tlaxcallan, Mexico: An Analysis Based on Demokratia. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:832440. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.832440

Received: 09 December 2021; Accepted: 15 February 2022;

Published: 29 March 2022.

Edited by:

Anar Ahmadov, Leiden University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Bryan McCannon, West Virginia University, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Fargher, Blanton and Heredia Espinoza. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lane F. Fargher, bGFuZWZhcmdoZXJAeWFob28uY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.