- Institute of Social Sciences, Humboldt University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany

This article uses a study on the impact of political (EU-specific) knowledge on perceptions of the legitimacy of the European Union to demonstrate the potential of the repertory grid method in the social sciences. The first objective of the study is methodological. The aim is to test the added value of the repertory grid method for surveying attitudes toward contested concepts, such as legitimacy. To this end, the influence of political knowledge on the perception of the legitimacy of the European Union is surveyed with the help of repertory grid interviews. Second, possible research questions on the effect of political knowledge on perceptions of legitimacy are developed, using the results of the present repertory grid study as a guidepost in this still underdeveloped field of research. The data collected in this preliminary study provide evidence that the importance of democratic norms and values for the evaluation of the legitimacy of national and European institutions is increasing, but at the same time critique of the political system is also increasing and the perception of legitimacy is thus decreasing.

Introduction

The democracies of the West are subjected to a crisis-like perceived transformation processes (Buchstein, 1996, p. 297). This, today more than ever (Ercan and Gagnon, 2014; Merkel, 2015), directs the focus to an increased need for legitimacy of democracy and the question of the preconditions of democracy. Debating Europe (Twitter, 9.5.2022, p. 10:21) recently tweeted in the context of the Conference on the Future of Europe with a quote from Cécile Robert1: “There is a legitimacy problem afflicting the EU, and it is important to find out how to overcome it. Debating EU attempts to answer this question by analyzing citizen positions”. Likewise, the argument of this paper, the position of the citizen is at the center of empirical legitimacy research. However, as legitimacy is one of the highly contested concepts of socio-political and also scientific debate, there is no consensus on how to define, operationalize and measure the concept of legitimacy. In the political science debate it is unclear, for example, whether legitimacy should be measured exclusively empirically or whether it should be evaluated normatively (Patberg, 2013), whether it should be understood as a bottom-up or top-down phenomenon, or whether legitimacy is a state or a process that itself constructs legitimacy (Wiesner and Harfst, 2019). This paper connects to this theoretical and especially methodological literature on the concept of legitimacy and its measurement, especially the Patberg-Zürn debate (Zürn, 2011; Patberg, 2013; Barnickel, 2021). Wiesner and Harfst (2019) suggest that these conceptual questions and problems regarding the empirical-analytical conception of legitimacy should be triggered by clarifying the role of normative standards in the empirical study of legitimacy. It is then necessary to ascertain which evaluation standards and which aspects of political legitimacy are considered relevant by the population, and then to examine the extent to which these standards or ideal concepts of legitimacy are congruent with the characteristics, norms, values and performance of the political system being evaluated. This is what Wiesner and Harfst (2019) describe as internal legitimacy, which focuses on legitimacy as Anerkennungswürdigkeit of a political system in the sense of Habermas (1976).2

In Europe, the debate on the legitimacy of political systems at the EU level is given additional controversy by persistent accusations of the EU's democratic deficit (Majone, 1998; Schäfer, 2006). In addition, the European multi-level system has its own peculiarities when it comes to the question of legitimacy, as the power relations between the Union, the member states, and the citizens are two-level via the circumventing route of the member states (Scharpf's, 2009). This complexity also entails the risk of inappropriate attributions of responsibility for national problems and, as a consequence, problems of legitimacy.

Given the strengths, but more importantly the weaknesses, of various models of empirical research on legitimacy, usually centered on traditional survey research, this paper seeks to develop an alternative approach that compares people's perceptions of the similarities between an observable phenomenon (governance structure) and their own normative values (what is legitimate) in the process of repertory grid interviews. The repertory grid is predestined for this type of research because it combines qualitative and quantitative methods. Since the initial data collection is qualitative, it allows for deeper and more nuanced meanings of the surveyed terms and concepts, while providing a potential solution to the problem of linguistic and cultural equivalence. The subsequent data analysis is both qualitative and quantitative. Therefore, individual data can be extrapolated to the macro level, allowing for comparability and transferability of results from the sample to a larger group. The paper discusses to what extent the repertory grid can facilitate the building of bridges between empirical legitimacy research as measurement or evaluation (Patberg, 2013), as it is neither based on pre-prepared questionnaires nor on prepared response scales but processes the respondents' own words and response scales.

In a first step, this paper presents the method of the repertory grid as an interface between the different approaches. Then, the theoretical background, data collection and analysis of the repertory grid are explained very briefly. The data analysis and potential of the repertory grid is illustrated by data from a current project on the influence of political knowledge on the perception of EU legitimacy.

Analyzing Legitimacy

Conceptional Approach of Empirical Research on Legitimacy

Empirical research on legitimacy comes with challenges that go beyond the EU-specific challenges of legitimacy research. From the author's point of view, the concept of empirical legitimacy goes beyond the acceptance of a political system (Beetham, 1991; Patberg, 2013), as the majority of the literature implements legitimacy empirically because it asks about the correspondence between the citizens' normative standards and the current political system (Beetham and Lord, 1999), what Weber (1992) called legitimacy beliefs or Habermas (1976) Anerkennungswürdigkeit (acceptability or recognizability) of a political system. These citizens' beliefs cannot be adequately measured with standardized surveys because their logic is deductively top-down oriented. Instead, there must be an evaluation (Patberg, 2013) by the citizens themselves in a more inductive bottom-up logic.

To put it in a nutshell: By measuring the acceptability of a political system, researchers are able to analyze the normative perspective of legitimacy (Schmidtke and Schneider, 2012, p. 226) represented by the positions articulated by citizens within the scientific construction of reality or, like Wiesner and Harfst (2019) call it, external legitimacy. It is not possible to analyze the attitudes of citizens in reality itself (Osterberg-Kaufmann, 2014). To analyze whether normative standards fit the experienced exercise of power and which normative standards lead to the judgment about the legitimacy of a political system (Fuchs, 2011, p. 31) [= the internal legitimacy of a political system (Wiesner and Harfst, 2019)], a mixed-methods approach is necessary, as Zürn (2013) points out. Repertory Grid sees itself as a methodological interface between measurement and evaluation, here of legitimacy. The paper aims to place repertory grid in this debate3 as a methodological alternative.

An Argument for Interdisciplinarity and for Mixed-Method Approaches

Despite all the innovations within the methodological perspective of political science in the survey of legitimacy, of which Barnickel (2020) has recently published a comprehensive analysis, this perspective nevertheless reaches its limits and therefore this article will not only promote a mixed-method approach, but also take a look beyond the disciplinary horizon. Empirical research on legitimacy is inherently a psychological measurement problem because the researcher aims to explore how individuals think and feel about legitimacy and the institutions being evaluated and, in turn, how these individual perceptions can be aggregated into a generalizable scale that can eventually be applied to entire populations, not just individuals. Within psychology, psychometric methods deal with similar issues. As an interdisciplinary approach, the application of psychometric methods for a more differentiated survey of legitimacy perception therefore seems promising (Rost, 2004; Moosbrugger and Kelava, 2008).

In both political science and psychometrics, the limitation to exclusively theoretical top-down approaches to quantitative measurement of citizens' legitimacy beliefs can be overcome by interviewing individuals from the target population along the steps of psychometric item development. This results in a wealth of information, but interpretation, structuring, and prioritization still remain purely qualitative judgments of the test developer. Therefore, although an exclusively qualitative bottom-up measurement is conceptually deeper than a theory-based quantitative measurement as we know it from legitimacy research, it is much more influenced by uncontrolled factors, comparable to exclusively qualitative approaches. In summary, the basic challenge for a comprehensive evaluation of something that is to be measured is usually the researcher telling the respondents what they have to answer (quantitative top-down approach) (Jankovicz, 2004). Alternatively, if qualitative additions are made, there is a risk that the object of measurement will be viewed from a highly subjective perspective of the researcher (qualitative bottom-up approach) (Osterberg-Kaufmann and Stadelmaier, 2020).

Repertory Grid as an Interface Between Measuring and Evaluating

The repertory grid represents a promising methodological alternative to the usual approaches (Kelly, 1955; Walker and Winter, 2007), especially when researchers want to explore a broader meaning of a concept, i.e., are looking for its differentiation. The repertory grid bridges the gap between qualitative and quantitative methods and can be the basis for a mixed-methods/multi-level approach, combining qualitative and quantitative instruments within a single study and using the data for a subsequent large-scale survey. In this sense, repertory grids according to Jankovicz (2004) can be considered a structured interview methodology combined with a multidimensional rating scale approach.

The Methodological Approach of Repertory Grid

Repertory grids consist of four aspects (Jankovicz, 2004; Shcheglova, 2010): The first aspect is the topic. The topic represents the experience of the respective respondents within the respective research subject. In this case, the topic is the legitimacy perception of the EU. The second aspect of the repertory grid is the set of elements. The elements are examples of the topic (e.g., institutions, persons, or the like that represent legitimate rule). The third aspect of a repertory grid is the so-called constructs. This term comes from humanistic psychology, in which it is assumed that each person constructs his or her own world through experience. His or her construction of reality is reflected in his or her constructs. The constructs of the respondents in the EU legitimacy perception study represent the individual constructions of legitimacy and are therefore the focus of interest. The theoretical pioneers of the psychology of personal constructs, George A. Kelly, assumed that a construct is always bipolar (Kelly, 1955). In this sense, “to the left” can be understood only in that the opposite pole is “to the right”. Finally, the fourth aspect of a repertory grid is the quantitative ratings of items by respondents on their constructs.

To arrive at these quantitative ratings of the elements by the respondents through their respective constructs, a repertory grid interview is conducted in the following steps. The respondent is presented with three items and asked which two of them are similar and at the same time different from the third. The respondent then states the way in which the two elements are similar. This becomes the first construct pole. The opposite construct pole is determined by asking the respondent to answer in what way the third element differs from the two similar ones. After the two construct poles are determined, the respondent conducts a rating of all the elements of the construct. This process is repeated several times with different element triads. On the one hand, this gives the researcher an extremely profound picture of individual rating patterns. On the other hand, the respective ratings create a data structure that can be analyzed using multivariate statistical methods (Osterberg-Kaufmann and Stadelmaier, 2020, p. 406f).

Research Example: Perceptions of Legitimacy in the EU and the Influence of EU-Specific Political Knowledge

The question of the perception of legitimacy, just like the question of the understanding and meaning of democracy, is always closely connected with the question of the preconditions and determining factors. Political knowledge is of great importance in both fields of research which have a certain conceptual abstractness in common. In addition to institutional arrangements and citizens' rights, normative theories of democracy repeatedly refer to certain qualifications or competencies of citizens which a functioning democracy requires. Within the discourse on civic virtues, Buchstein (1996, p. 302) summarizes these qualifications as cognitive and procedural competences for the formation of (strategic) political preferences on the knowledge dimension and habitual dispositions.

The majority of research to date devoted to the consequences of more or less political knowledge on attitudes and behavior (Delli Carpini and Keeter, 1996; Sinnott, 2000; Galston, 2001; Gilens, 2001; Karp and Bowler, 2003) focuses primarily on the influence of political knowledge on participation or voting behavior, that is, the observable part of habitual dispositions. Largely unexplored is the relationship between political knowledge and legitimacy, i.e., attitudes toward the political system that, along with other factors, lead to more or less participation and to certain electoral behavior.

From the literature on the influence of political knowledge on political attitudes, both a positive and a negative influence can be derived (Sinnott, 2000; Karp and Bowler, 2003). Against the background of this literature, the following will demonstrate, with an exemplary study on the influence of EU-specific policy knowledge on the perception of EU legitimacy, what kind of research is possible with Repertory Grid in political science.

Research Design

With a quasi-experimental time-series design, political knowledge (independent variable) is not measured directly, but in the logic of an experiment. Between time t1 and t3 at time t2 the teaching of EU-specific knowledge took place as treatment (X) and in the case of the control group this treatment did not take place. Using the repertory grid method, we only measured how the perception of the legitimacy of the EU (dependent variable) changed between time t1 and time t3.

The aim of experimental designs is to test whether an independent variable X has a causal effect on the dependent variable Y, based on a directed hypothesis. Under control of confounding factors, the independent variable that is expected to have an effect is manipulated (stimulus or treatment) and then observed to see if a change occurs in the dependent variable. Controlling confounding factors is much more challenging in the social sciences than in experiments under laboratory conditions in the natural sciences. The social sciences compensate for this by dividing the subjects into a test or experimental group and a control group. While the experimental group receives a treatment X, the control group does not receive this treatment. Ideally, this should be the only distinction between the two groups, so that the confounding factors that affect both groups in the time before treatment t1 and the time after treatment t3 are as constant as possible (Jäckle, 2015).

The distribution of the subjects to the experimental group and the control group is done according to the expression of assumed confounding factors, which are randomly distributed to both groups (matching). Precisely this randomized distribution is not possible in quasi-experiments, because the allocation to the control or experimental group is, for example, made by the study unit itself, is determined by the experimenter, or is made by natural division into, for example, school classes or seminar groups (Shadish et al., 2001). The internal validity of quasi-experimental designs is limited before this context because changes in the dependent variable cannot be unambiguously attributed to changes in the independent variable. Whether changes in the dependent variable are due to the treatment or to systematically different third-party variables such as intelligence, prior knowledge, or specific experiences cannot be stated with certainty (Jäckle, 2015). Thus, the control group serves only to control for time effects and not to prove the effectiveness of the treatment (Osterberg-Kaufmann, 2019a).

In the present study, students at university courses with EU-specific content were surveyed at two time points, once at the beginning of the semester (t1) and once at the end of the semester (t3) using the repertory grid. This EU group (students of courses with EU-specific content)4 was contrasted with a control group that attended an introductory course in which no EU topics were discussed. Both groups were students of the Political Science Major at Leuphana University of Lueneburg. The groups differed only in the overall number of program semesters. Accordingly, this arrangement represents a quasi-experimental design, as the assignment to the experimental group (EU-specific) and to the control group was not randomized but based on the teaching content of the respective course, similar to Green et al. (2011). The surveys took place in October 2014 and January 2015.

Legitimacy, as already mentioned, should be understood in the Weberian sense (1992) as the perception of legitimacy and, according to Ferrín and Kriesi (2016, p. 10), should be measured via the comparison between the (democratic) ideals and the actual functioning of democracy or the political system in general. It is through this necessary comparison, that the individual makes a judgment about the legitimacy of the object under study (for example, democracy, the EU, or the political system). Repertory grid enables the analysis of the correspondence between citizens' normative standards and their evaluation of the political system, measured against their own standards in each case, without making a detour via public communication (Zürn, 2013) or the interpretive researcher (Patberg, 2013). Repertory grid works with the words of the respondents themselves to measure their subjective constructs concerning the object of research. The key assumption behind the method is that people (re)construct reality in order to interact with the world. In doing so, people anticipate events by combining their own individual experiences. People finally evaluate the results of their actions with the personal constructs available to them from their experience and, following these personal constructs, adapt their behavior to the demands of the environment (Jankovicz, 2004).

In the repertory grid methodology, the elements are adequate representations of the selected topic [e.g., objects, people, and situations (Jankovicz, 2004)]. As in the current study on legitimacy perception of the EU, the developed set of elements, as the first step and basis of the repertory grid interview, consists of eight theoretical representations of the political institutions to be evaluated as legitimate, namely key national (German Bundestag, German Bundesrat, German Government, German Constitutional Court) and European (European Parliament, European Commission, European Court of Justice, European Central Bank) institutions as well as two additional, more general, elements as experts and the most legitimate rule to represent the normative standards of legitimacy (ideal) for the following study. These elements are compared to the normative standard of legitimacy (ideal) as well as to each other element of the interview (Osterberg-Kaufmann, 2019a,b; Osterberg-Kaufmann and Stadelmaier, 2020). The division of the elements into the national and the European level goes back to the specifics for legitimacy in the European multi-level system. Following Scharpf's (2009) considerations, the power relations in the European multi-level system move on two levels, which are reflected in the research design with the national and the European institutions.

A repertory grid interview is conducted in the following steps. The interviewee is presented with three elements and asked which two of them are similar and at the same time different from the third. The respondent then states the way in which the two elements are similar. This is the first construct pole. The opposite construct pole is determined by asking the respondent to answer in what way the third item differs from the two similar ones. After the two construct poles are identified, the respondent makes an assessment of all the elements of the construct. This process is repeated several times with different element triads. The combination of elements into triads follows the random principle and is done by the interview support software.5 As a general rule, about 10 constructs are revealed per respondent. On the one hand, this gives the researcher an extremely profound picture of individual assessment patterns. On the other hand, the respective ratings create a data structure that can be analyzed using multivariate statistical methods.6

Analyses of the Quantitative Data

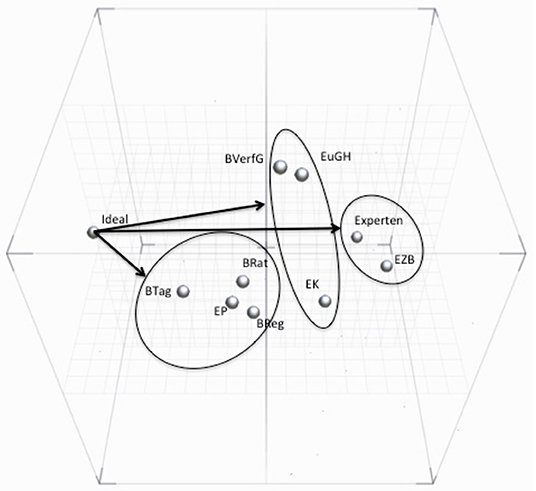

The repertory grid interview procedure and setting described above results in a data set that is the starting point for quantitative principal component analysis. Principal component analysis of a multiple repertory grid provides two basic pieces of information about how a group of people think and feel about a particular topic. The very first piece of information is the spatial arrangement of the individual elements. The farther apart the elements are, the more different they are perceived. On the other hand, the closer they are to each other, the more similar they are perceived. In the present study, the spatial distance of the items was determined by their factor scores for the identified principal components. The second piece of information of a multiple repertory grid is the spatial arrangement of the constructs compared to the spatial arrangements of the items. This was determined in the present study by the respective factor loadings of a construct item on each principal component. The closer a construct is to an element (determined by the factor loadings of the items compared to the factor loadings of the constructs), the more characteristic that construct is to that item.

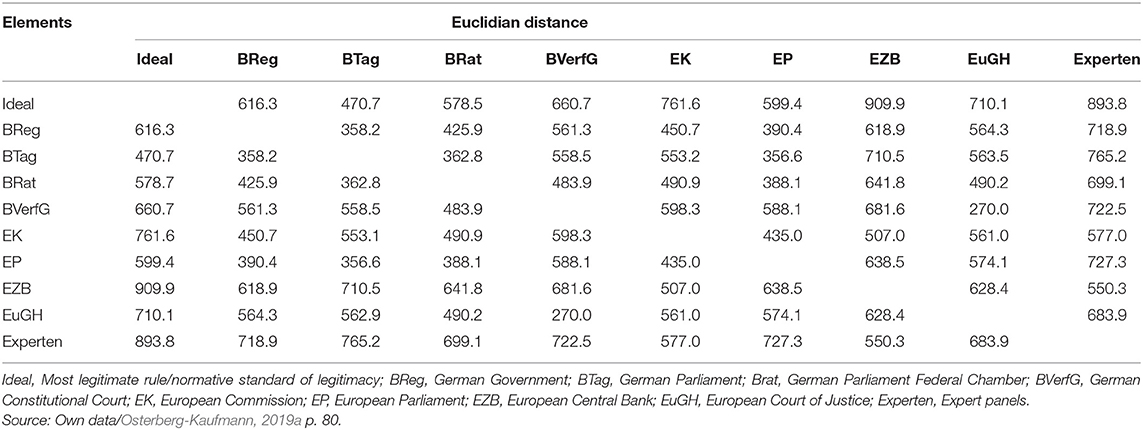

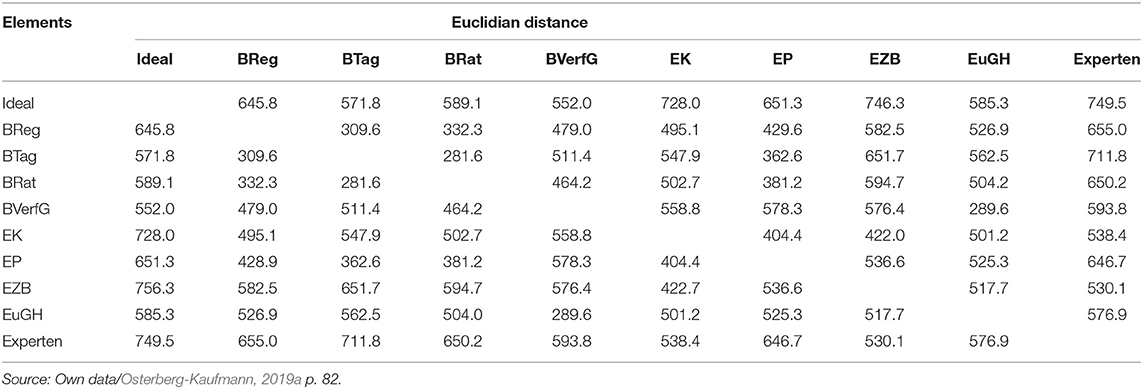

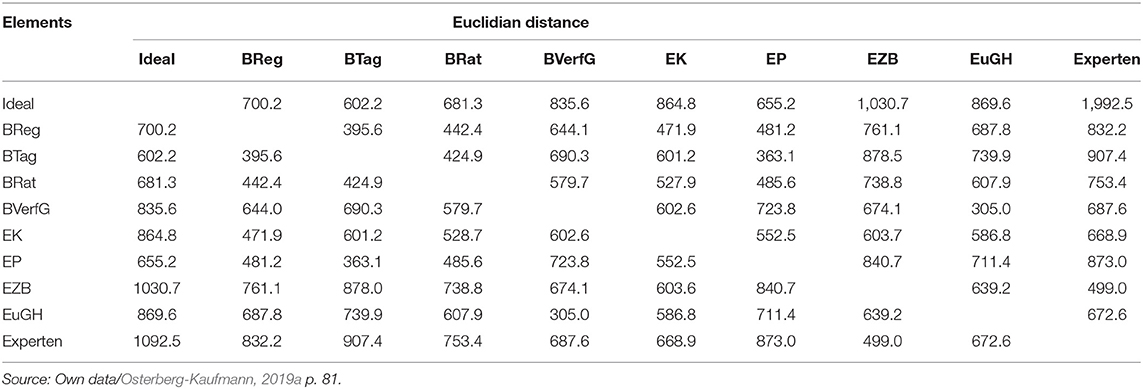

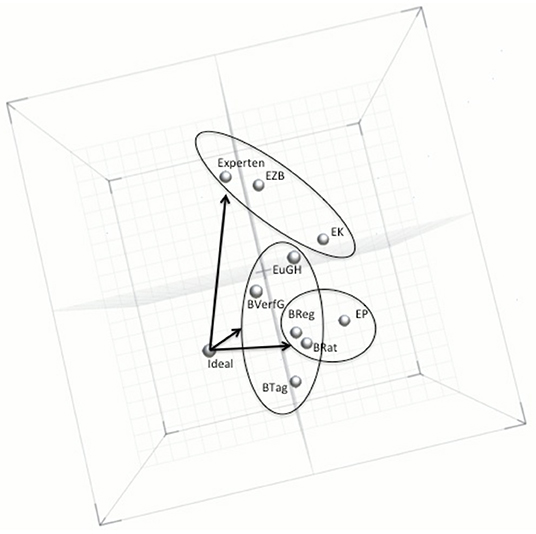

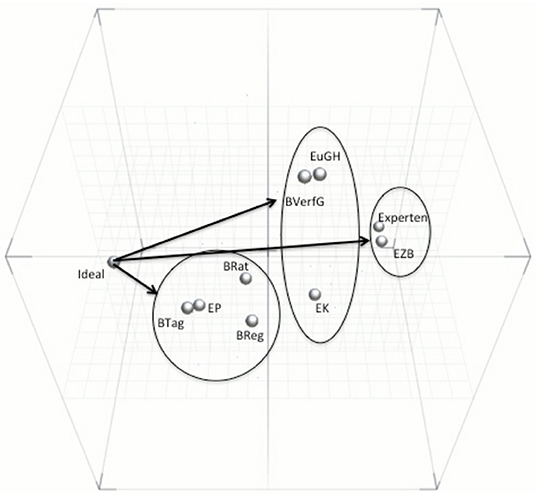

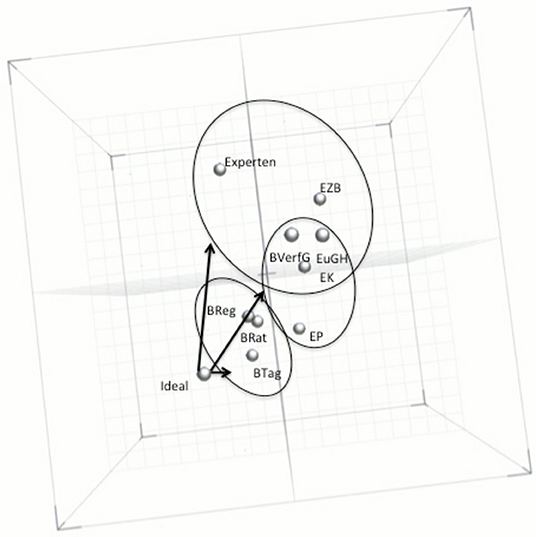

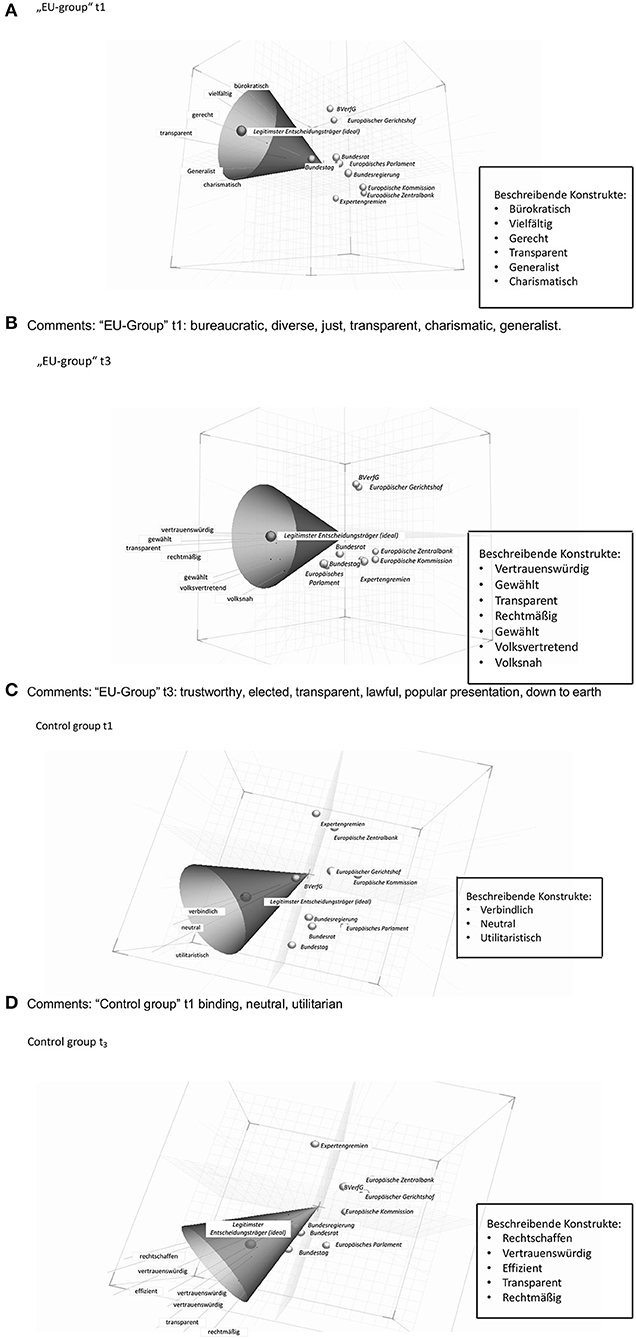

The software congrid® (permitto GmbH 2019) and SPSS were used for the statistical analyses. As a result of the interviews, 19 participants delivered a total of 824 constructs.7 Due to the combination of qualitative and quantitative methodology, the author believes that the sole use of quantitative measures to evaluate the results of the analysis would not be appropriate. Additional qualitative information should be considered when interpreting the spatial arrangement of elements and constructs. To this end, the congrid® software provides a graphical overview of the described spatial structure of the multiple repertory network, as shown in Figures 1–4. The underlying Euclidean distances8 are shown in Tables 1–4.

Figure 1. Elements and constructs Grid, EU group t1. Ideal, Most legitimate rule/normative standard of legitimacy; BReg, German Government; BTag, German Parliament; Brat, German Parliament Federal Chamber; BVerfG, German Constitutional Court; EK, European Commission; EP, European Parliament; EZB, European Central Bank; EuGH, European Court of Justice; Experten, Expert panels. (Source: Own data/Osterberg-Kaufmann, 2019a p. 80).

Figure 2. Elements and constructs Grid, EU group t3. (Source: Own data/Osterberg-Kaufmann, 2019a, p. 82).

Figure 3. Elements and constructs Grid, Control group t1. (Source: Own data/Osterberg-Kaufmann, 2019a, p. 81).

Figure 4. Elements and constructs Grid, Control group t3. (Source: Own data/Osterberg-Kaufmann, 2019a, p. 83).

By combining spatial arrangement and Euclidean distances, the data show, as a first result, that none of the elements conformed to normative standards of legitimacy (most legitimate rule) at any point in time. At the same time, once again, national institutions turn out to be more legitimate than European institutions in the perception of the respondents. These findings contradict the Eurobarometer data, according to which, for example, more trust is placed in the European Parliament than in national parliaments. However, this high level of trust in the European Parliament is discussed in the literature as surprising, since it lacks considerable powers compared to national parliaments (Schmidt, 2013). The results of the repertory grid studies are thus more in line with political science debates than the trust findings for the European Parliament in the Eurobarometer surveys.

The comparison between the two time points also shows that all elements have lost legitimacy. It seems that the legitimacy attributed to each element, as a second result of the exploratory study, decreases with increasing EU-specific knowledge between t1 and t3. This loss of legitimacy is dramatic in the EU group, although the elements lose legitimacy to varying degrees. The loss of legitimacy perceived by respondents is lowest for the European Parliament, the German government, the Bundesrat and the European Commission. The loss of legitimacy is highest for the European Central Bank, the Bundestag, the European Court of Justice, the Federal Constitutional Court and, above all, for the expert bodies. Among the group of EU institutions surveyed, those that have lost the most legitimacy (with the exception of the Bundestag) are those that are independent of the will of the voters and thus beyond democratic control. Thus, as a third finding, the results of the repertory grid contradict the thesis of the gain in legitimacy of non-majoritarian institutions discussed in the literature (Zürn, 2012, p. 60).

To sum up, the democratically legitimized core institutions have lost less legitimacy compared to all others and have thus gained in importance overall. However, all elements have lost legitimacy in the perception of respondents, as evidenced by the increasing (spatial and numerical) distance between the most legitimate decision-maker (ideal) and the other elements as a growing dissimilarity between the ideal notion of a legitimate decision-maker and all others. On the one hand, these results possibly show a trend of growing support for democratic norms and values, which was favored by confounding factors, as it is evident in the EU group, but even stronger in the control group. However, the other observed trend, namely the fundamental loss of legitimacy, has increased in the EU group due to the treatment teaching EU-specific knowledge and has been accompanied by a simultaneously more critical evaluation of the political system. The loss of legitimacy was more dramatic in the EU group than in the control group. This finding probably indicates growing support for democratic norms and values according to increasing political knowledge, which is accompanied by a more critical evaluation of the political system at the same time. The following discussion of the normative standards of legitimacy and the European Parliament strengthens this assumption.

Analyses of the Qualitative Data

In order to measure perceptions of legitimacy according to Ferrín and Kriesi (2016, p. 10) by comparing (democratic) ideals with the actual functioning of the political system, it is first necessary to ascertain the normative standard, i.e., the respondents' ideal conceptions of a legitimate government/rule. It is possible with the Repertory Grid to map this comparison by having respondents rate the elements. Furthermore, working with respondents' constructs provides qualitative data about the conceptual understandings, norms and values behind the evaluation. The ideal conception of legitimacy underlying each evaluation can be represented at both points in time of the study with the so-called semantic corridor. In order to visualize the normative standard of legitimacy and its change over time, those constructs with the greatest influence on the positioning of the element “most legitimate decision-maker” in the three-dimensional space are compared with each other, i.e., those constructs that are most relevant for the respondents in this context.9

The comparative analysis of the decisive constructs describing the element “most legitimate decision-maker” shows differences in the two groups of respondents at time t1 with regard to their understanding of legitimacy (Figure 5). While the EU group characterizes “the most legitimate decision-maker” as an ideal conception of legitimacy, as “bureaucratic,” “diverse,” “just,” “transparent,” “generalist,” and “charismatic”, the control group describes “the most legitimate decision-maker” as “authoritative,” “neutral,” and “utilitarian”. None of the other elements of the study show much similarity to the ideal conception of legitimacy (“most legitimate decision maker”).

Figure 5. Normative standard of legitimacy. (A) “EU-Group” t1: bureaucratic, diverse, just, transparent, charismatic, and generalist. (B) “EU-Group” t3: trustworthy, elected, transparent, lawful, popular presentation, and down to earth. (C) “Control group” t1 binding, neutral, and utilitarian. (D) “Control group” t3: righteous, trustworthy, efficient, transparent, and lawful. (Source: Own data, Osterberg-Kaufmann, 2019a p. 74–75).

At time t3, i.e., after the treatment, the EU group describes “the most legitimate decision maker” as “transparent”, as already at time t1, all other descriptive constructs deviate. “The most legitimate decision maker” is now described as “trustworthy,” “elected,” “legitimate,” “representative of the people,” and “close to the people”. Thus, after the treatment with elected and people-representative, components of representative democracy gain importance for the understanding of legitimacy. In the control group, “trustworthy,” “transparent,” and “lawful” also suddenly gain relevance for the description of “the most legitimate decision-maker”, as well as “efficient” and “righteous”. Constructs that stand for representative democracy, comparable to the EU group, are not found. Thus, it can be concluded that the increase in importance of the representative-democratic constructs “elected” and “representative of the people” is not due to confounding factors, but probably actually due to the treatment. The descriptive constructs “trustworthy” and “lawful”, on the other hand, gain in importance in both groups at time t3, indicating the influence of a confounding factor.

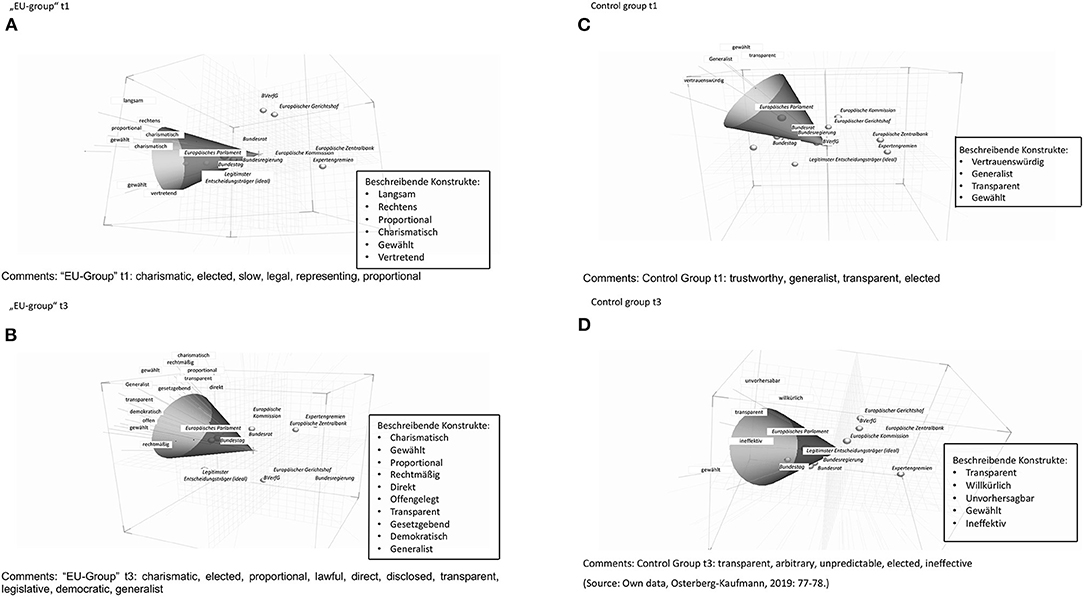

The comparative analysis of the crucial constructs describing the element most legitimate ruler shows an increase in representative-democratic norms and values with increasing EU-specific political knowledge. However, it is not the normative standards on legitimacy alone that have changed between the two survey dates. The perception of the European Parliament, as an example, has changed for the EU group after the treatment as well (Figure 6). The constructs that proved to be most decisive for the perceptions of the European Parliament in the “EU group” at t1 were: “charismatic,” “elected,” “slow,” “rightful,” “representative,” and “proportional”. At t3, the constructs: “charismatic,” “elected,” and “proportional” remained constant. Apart from that, the conception of the European Parliament changed toward descriptions such as “lawful,” “direct,” “disclosed,” “transparent,” “legislative,” “democratic,” and “generalist”. In the control group, the constructs that proved most crucial for the conceptions of the European Parliament at t1 were: “trustworthy,” “generalist,” “elected,” and “transparent”. While “elected” and “transparent” were descriptions that remained constant at t3, the constructs “arbitrary,” “unpredictable,” “partisan,” and “ineffective” characterized the European Parliament most decisively at t3.

Figure 6. Perceptions of the European Parliament. (A) “EU-Group” t1: charismatic, elected, slow, legal, representing, and proportional. (B) “EU-Group” t3: charismatic, elected, proportional, lawful, direct, disclosed, transparent, legislative, democratic, and generalist. (C) Control Group t1: trustworthy, generalist, transparent, and elected. (D) Control Group t3: transparent, arbitrary, unpredictable, elected, and ineffective. (Source: Own data, Osterberg-Kaufmann, 2019a p. 77–78).

Without wanting to interpret the results too strongly at this point, it seems that the perception of the European Parliament in the control group, which did not gain any EU-specific political knowledge in class between t1 and t3, shows a strong negative trend with the descriptions “arbitrary,” “unpredictable,” and “ineffective”.

As could be shown by means of the semantic corridor for understanding the “most legitimate decision maker” (Figure 5), a change in the perception of legitimacy toward democratic norms and values took place in the control group with increasing political knowledge (not EU-specific). As shown above, the understanding of legitimacy changed from: “binding,” “neutral,” and “utilitarian,” to: “rightful,” “lawful,” “elected,” “trustworthy,” “transparent,” and “efficient”. Given these changes in the understanding of legitimacy, the existing image of the European Parliament seems to be less in line with normative standards on legitimacy than before. Negative descriptions (“arbitrary,” “unpredictable,” and “ineffective”) are attributed to the European Parliament at t3 (Figure 6).

In the “EU group”, too, the perception of the European Parliament has changed, but less in the fundamental evaluation of this institution than in the form of a more differentiated evaluation with an increase in EU-specific knowledge. This change in perception does not affect the fundamental evaluation of the European Parliament. However, the view of the European Parliament became increasingly differentiated with increasing EU-specific political knowledge. The general evaluation of the European Parliament remained positive, but the crucial constructs almost doubled (Figure 6).10

In addition, the repertory grid data can be used to understand whether the same standards are applied to the EU institutions as to the national institutions. Are the constructs at both levels the same, and if so, are the standards used to assess the legitimacy of these institutions the same? To illustrate this methodological possibility, the German Bundestag, as a national institution with similar tasks, will now be added to the consideration of the most legitimate rulers and the European Parliament at the European level in a comparative way. Are they considered similar in terms of legitimacy and are they evaluated on the basis of the same constructs?

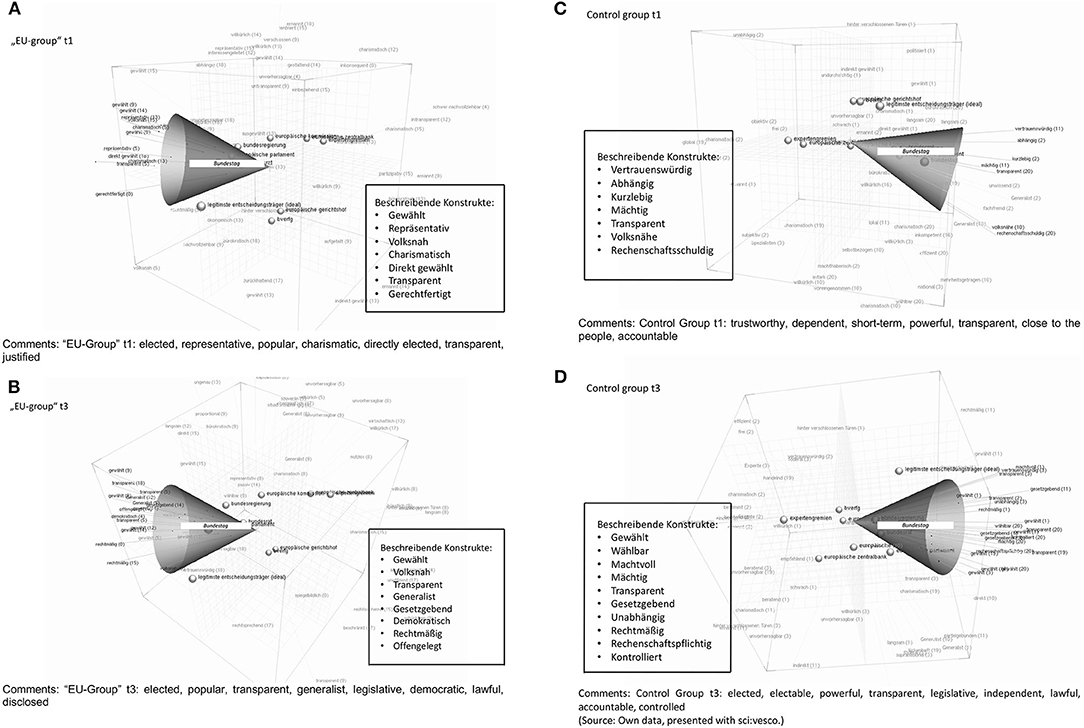

First of all, a clear difference in the perception of the European Parliament and the German Bundestag is noticeable at first glance. The descriptive constructs that are decisive for the German Bundestag (Figure 7) in the data evaluation are numerically larger and thus more differentiated than the perception of the European Parliament, in both groups and at both points in time. If we have seen that the perception of the European Parliament is more differentiated at time t2, especially in the EU group, we also see such a more differentiated perception in both groups at time t1 when looking at the German Bundestag. The available data point to how Delli Carpini and Keeter (1996) have been able to show for U.S. citizens' political knowledge and influence on political attitudes that there is a link between political knowledge and increasing complexity and sophistication of political attitudes. Increasing political knowledge triggers changes in perceptions of institutions, as do normative standards of legitimacy. In other words, institutions about which the respondent has more knowledge are perceived in a more differentiated way than less well-known institutions, as the comparison between the German Bundestag and the European Parliament shows.

Figure 7. Perceptions of the German Bundestag (Parliament). (A) “EU-Group” t1: elected, representative, popular, charismatic, directly elected, transparent, and justified. (B) “EU-Group” t3: elected, popular, transparent, generalist, legislative, democratic, lawful, and disclosed. (C) Control Group t1: trustworthy, dependent, short-term, powerful, transparent, close to the people, and accountable. (D) Control Group t3: elected, electable, powerful, transparent, legislative, independent, lawful, accountable, and controlled. (Source: Own data, presented with sci:vesco).

If we look at the development of the perception of the German Bundestag (Figure 7) in the EU group in terms of content, we see that the characteristics “elected” or “directly elected,” “close to the citizens,” “transparent,” and “justified” or “lawful” are perceived as decisive at both points in time. What got lost between t1 and t3 is the perception of the German Bundestag as “representative” and “charismatic”. What has been added at time t2 is the perception of the German Bundestag as “generalist” and “disclosed”, in a legitimatory perspective as “democratic” and functionally oriented as “legislative”.

In the perception of the control group, the characteristics “trustworthy” or “trusting,” “powerful,” “transparent,” and “accountable” were characteristic of the German Bundestag at both points in time. Thus, the perception of the German Bundestag as “transparent”, is the only agreement in both groups of respondents, at both points in time. And the European Parliament (Figure 6) is also perceived as “transparent” in the same way as the German Bundestag (with the exception of t1 in the “EU group”). Transparency thus seems to be a quality that is generally attributed to parliaments, regardless of whether they are located at national or European level. The perception of the German Bundestag (Figure 7) as “close to the people” and as “short-term” is no longer found at time t3. While the German Bundestag was interestingly perceived as “dependent” at time t1, this perception has completely reversed at time t2 and the German Bundestag is perceived as “independent”. The perception of the German Bundestag at time t3 has also become somewhat differentiated and is seen as “elected” or “eligible,” “legitimate,” and “controlled”.

Inquiring into the extent to which the constructs by means of which the European Parliament and the German Bundestag are evaluated and perceived are identical, we can observe such agreement very strongly in the EU group at both points in time (Figure 6). In the control group, on the other hand, which not only did not receive any explicitly EU-relevant knowledge, but also consisted exclusively of first-year students, we see hardly any agreement between the evaluation of the Parliament at European and national level. This suggests that the criteria for assessing how legitimate the European Parliament and the German Bundestag are differ greatly. Furthermore, it is striking that the German Bundestag is consistently characterized positively in this group of respondents, while the descriptions of the European Parliament are predominantly negative.

Overall, this qualitative finding comparing the European Parliament and the German Bundestag confirms the quantitative analysis. In accordance with very similar evaluation criteria, the EU group perceived both the German Bundestag and the European Parliament as comparatively (very) legitimate. The control group, on the other hand, perceived the parliaments at the national and European levels very differently and consistently rated the German Bundestag as much more legitimate than the European Parliament.

Conclusion

This paper positioned repertory grid as a mixed-method approach. Therefore, it builds on the advantages of qualitative methods during the interview and quantitative methods during the analysis, at the same time reducing the respective disadvantages.

First of all, a repertory grid approach weakens the phenomena of social desirability and paying lip-service, as the interview itself is based on the individuals' value context and is completely open during the interview without allowing fuzzy answers. It provides an insight into the complexity of the respondents' entire evaluation system.

Secondly, the subjective evaluation based on the respondents' own evaluation/ranking constructs eliminates the effects of linguistic and cultural equivalence within the interview and even allows to understand the different cultural and linguistic meaning of words during the analysis.

Thirdly, the qualitative data of the repertory grid interview being standardized and aggregated on a macro level, the method allows for comparisons on a country/group level as well as transferability.

Finally, if empirical research on legitimacy is not about measuring the acceptance of a political system deductively, but about figuring out if the exercise of rule is in line with the societies' normative standards11 inductively, measuring and evaluating have to be interconnected within one and the same survey method. Here lies the strength of repertory grids, namely its ability to mediate between empirical research on legitimacy as measuring and as evaluating. By characterizing (constructs) the most legitimate rule, repertory grid is measuring the normative standards of the respondent. By mapping the institutions (elements) on the basis of these normative standards, respondents can express their agreement or disagreement with the exercise of power (by mapping the element most legitimate rule).

With the help of the repertory grid, this paper proposes an alternative method for surveying legitimacy perceptions and illustrates it with a quasi-experimental design for surveying the influence of EU-specific knowledge on attitudes and legitimacy perceptions as a showcase. Firstly, the showcase has been able to demonstrate that, with increasing EU-specific political knowledge (X), the perception of the EU's legitimacy declined. However, this negative correlation was not only evident for the European institutions, but also for the national institutions. Secondly, with the assumed increase of EU-specific knowledge by treatment (X), the importance of the democratically legitimated core institutions increased in the perception of respondents compared to all other institutions. Moreover, legitimacy was explicitly associated with representative democratic attributes after treatment (X). To this end, the following research themes can be noted as research topics to be pursued further in the present exploratory sample study on the influence of EU-specific political knowledge on the perception of EU legitimacy, which can be further investigated in both national and European studies. Perceptions of the legitimacy of European and national institutions seem to decrease with increasing political knowledge. As political knowledge increases, the importance of core democratically legitimized institutions seems to increase in respondents' perceptions compared to all others. In particular, representative democratic features seem to gain in importance in the perception of legitimacy with increasing political knowledge.

Nevertheless, there are limits to large-scale implementation of repertory grid studies, as the surveys take time and the associated costs are relatively high compared to standardized surveys. Alternatives would be the analysis of a low number of special cases, like the comparison of typical cases and outliers of a Large-N analysis or special groups like political elites or a selection of cases following the logic of nested-analysis approaches (Liebermann, 2005). Based on the promising evidence of repertory grid projects on legitimacy (Osterberg-Kaufmann, 2014, 2019a,b), the next step could be a case selection for a comparative study on the understanding of legitimacy in the EU between different European countries. Following the nested-analysis approach (Liebermann, 2005), data of a large-N analysis like Eurobarometer can be the basis of the case selection for the small-N repertory grid analysis and on the basis of this foundation a new evaluation and interpretation of the existing survey data would be possible, allowing also for a meaningful reformulation of established survey questions concerning citizen's attitudes toward the EU. At least equally stimulating would be further studies on the influence of political knowledge on the legitimacy perception of certain social groups in a larger survey over a longer period of time. In order to achieve representativeness and thus generalizable results, it would also be a worthwhile option to transfer the results of the repertory grid studies to the semantic differential method, which would allow a larger number of interviews to be conducted in a next step, as it is a purely quantitative approach. The advantage of this multi-level design would be that the construct poles of the semantic differential are based on the respondent's own constructs of the repertory grid interview and thereby are bottom-up created instead of top-down defined (Osterberg-Kaufmann and Stadelmaier, 2020).

To strengthen the possibilities of repertory grid within the inductive logic for future research, the elements of the interview should become developed by the respondents themselves in focus groups, e.g., instead of being defined by the researcher and thereby strictly limited by their deductive nature.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Professor of Political Sciences at Science Po Lyon.

2. ^With the reference to Habermasian “Anerkennungswürdigkeit” (recognizability), the concept of legitimacy itself makes an authentic claim to validity regarding the recognizability of a political order (Habermas, 1976, p. 39). A political order is legitimate if it is indeed morally justified and thus should consequently be recognized.

3. ^The complete debate can be read here: Zürn (2011) and Patberg (2013).

4. ^Seminar: Europeanisation of German Domestic Policy. The course takes up the question of the extent to which one can still speak of “German domestic policy” in the face of advancing European integration. This question can only be answered on a policy field-specific basis. After a recapitulation of the relevant concepts and theories and a review of the debate on the “myth of Europeanisation”, the course is devoted to the (Europeanisation of) education, asylum, finance, foreign and security policy and other policy fields (conceivable, among others, are environmental, research, social, family, transport, or energy policy). Seminar: Constitutional politics in a multi-level system: The course deals with the change of the Constitution in the multi-level system of the Federal Republic of Germany and takes up aspects of governing in a multi-level system. The changed political framework conditions are also taken into account. After a recapitulation of the relevant concepts and theories of governance in a multi-level system and forms of constitutional change, the course will focus on the actors at European, national and supranational level and finally deal with two examples of constitutional reforms (asylum law reform and higher education policy).

5. ^Here it is particularly important to note that the selection of elements that the interviewees are confronted with to generate their own constructs are randomly selected by the interview support software, in order to prevent, for example, a bias due to certain combinations of items in a certain order.

6. ^For detailed descriptions of the repertory grid methods and their application to social science research subjects, please see here: Osterberg-Kaufmann and Stadelmaier (2020).

7. ^N = 19, including 11 in the EU-group and 8 in the control group, aged 18–24. The data set includes 412 cases with two poles each. Eight hundred and twenty-four constructs in total were developed by the interviewees. These constructs emerged in an average of five interview sequences each with random combinations of three items. Due to the student respondent group, the present results cannot be generalized, but can help generate or test hypotheses of the research field.

8. ^Distance is the expression for the difference between two objects in a space. In personal construction psychology, the most commonly used statistic for calculating distance is Euclidean distance. Euclidean distance is used as a measure of similarity and difference between elements. For more information see: Slater (1977) and Schoeneich and Klapp (1998).

9. ^Therefore, the semantic corridor highlights elements and constructs at a predefined angle to represent similarities to other elements and how they are characterized by constructs. The better a construct describes the selected element, the tighter the angle between construct and element. Angles smaller than 45° describe a semantic cluster. To reduce the number of descriptive constructs, the angle for the following analysis of the normative standard of legitimacy was reduced to 25° for the element most legitimate decision-maker (ideal).

10. ^The constructs almost doubled within the 25° angle in the European Parliament's semantic corridor.

11. ^This is especially true if this accordance is not judged by an external researcher.

References

Barnickel, C. (2020). “Vorstellungen legitimen Regierens: Legitimationspolitik in der Groβen Regierungserklärung der 19. Wahlperiode im Vergleich,” in Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 14/3, 199–223.

Barnickel, C. (2021). Kritik und Normativität in der (empirischen) Legitimitätsforschung. Politische Vierteljahresschrift 62, 19–43. doi: 10.1007/s11615-020-00288-6

Beetham, D. (1991). The legitimation of power. Issues in political theory. Atlantic Highlands: Humanities Press International.

Beetham, D., and Lord, C. (1999). “Legitimacy and the European union”, in Political Theory and the European Union: Legitimacy, Constitutional Choice and Citizenship, eds. M. Nentwich and A. Weale (London: Routledge),15–33.

Buchstein, H. (1996). “Die Zumutungen der Demokratie. Von der normativen Theorie des Bürgers zur institutionell vermittelten Präferenzkompetenz,” in Politische Theorien in der Ära der Transformation, eds. K. v. Beyme and C. (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften), 295–324.

Delli Carpini, M. X., and Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans Know about Politics and Why It Matters. Yale: University Press.

Ercan, S. A., and Gagnon, J. -P. (2014). The crisis of democracy: which crisis? Which democracy? Democ. Theory 1, 1–10. doi: 10.3167/dt.2014.010201

Ferrín, M., and Kriesi, H. (eds.). (2016). “Introduction: democracy – the European verdict”, in How Europeans View Democracy, (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1–20.

Fuchs, D. (2011). “Cultural diversity, European identity and legitimacy of the EU: a theoretical framework”, in Cultural Diversity, European Identity and the Legitimacy of the EU, eds. D. Fuchs and H.- D. Klingemann (Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar), 27–57.

Galston, W. A. (2001). Political knowledge, political engagement, and civic education. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 4, 217–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.217

Gilens, M. (2001). Political ignorance and collective policy preferences. The Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 95, 379–396. doi: 10.1017/S0003055401002222

Green, D. P., Aronow, P. M., Bergan, D. E., Greene, P., Paris, C., and Weinberger, B. I. (2011). Does knowledge of constitutional principles increase support for civil liberties? Results from a randomized field experiment. J. Polit. 73, 463–476. doi: 10.1017/S0022381611000107

Habermas, J. (1976). Legitimationsprobleme im modernen Staat. Politische Vierteljahresschrift Special Issue 7, 39–60. doi: 10.1007/978-3-322-88717-7_2

Jäckle, S. (2015). “Experimente,” in Methodologie, Methoden, Forschungsdesign, eds. A. Hildebrandt, S. Jäckle, F. Wolf and A. Heindl (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 13–35.

Karp, J. A., and Bowler, S. (2003). To know it is to love it? Satisfaction with democracy in the European Union? Comp. Polit. Stud. 36, 271–292. doi: 10.1177/0010414002250669

Liebermann, E. S. (2005). Nested analysis as a mixed-methods strategy for comparative research. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 99, 435–452. doi: 10.1017/S0003055405051762

Majone, G. (1998). Europe's ‘Democratic deficit’. The question of standards. Eur. Law J. 4, 5–28. doi: 10.1111/1468-0386.00040

Moosbrugger, H., and Kelava, A. (2008). Testtheorie und Fragebogenkonstruktion: mit 43 Tabellen. Berlin; Heidelberg; New York, NY: Springer.

Osterberg-Kaufmann, N. (2014). Die Wahrnehmung zur Legitimität in der EU: Kongruenz oder Inkongruenz der politischen Kultur von Eliten und Bürgern? Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 8, 143–176. doi: 10.1007/s12286-014-0205-x

Osterberg-Kaufmann, N. (2019a). Die Legitimitätswahrnehmung in der EU und der Einfluss von EU-spezifischem politischen Wissen. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 13, 61–91. doi: 10.1007/s12286-019-00411-x

Osterberg-Kaufmann, N. (2019b). “Legitimitätswahrnehmung in der EU und Repertory Grid,” in Legitimation und Legitimität in vergleichender Perspektive, eds. C. Wiesner and P. Harfst (Wiesebaden: VS Springer), 239–276.

Osterberg-Kaufmann, N., and Stadelmaier, U. (2020). Measuring meanings of democracy—methods of differentiation. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 14, 401–423. doi: 10.1007/s12286-020-00461-6

Patberg, M. (2013). Zwei Modelle empirischer Legitimitätsforschung: Eine Replik auf Michael Zürns Gastbeitrag in der PVS 4/2011. Politische Vierteljahresschrift 54, 155–172. doi: 10.5771/0032-3470-2013-1-155

Schäfer, A. (2006). Nach dem permissiven Konsens. Das Demokratiedefizit der Europäischen Union. Leviathan 34, 350–376. doi: 10.1007/s11578-006-0020-0

Scharpf, F. (2009). Legitimität im europäischen Mehrebenensystem. Leviathan 37, 244–280. doi: 10.1007/s11578-009-0016-7

Schmidt, V. A. (2013). Democracy and legitimacy in the European union revisted: input, output and ‘throughput’. Polit. Stud. 61, 2–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00962.x

Schmidtke, H., and Schneider, L. (2012). Methoden der empirischen Legitimationsforschung: Legitimität als mehrdimensionales Konzept. Leviathan 40, 225–242. doi: 10.5771/9783845245072-225

Schoeneich, F., and Klapp, B. F. (1998). Standardization of interelement distances in repertory grid technique and its consequences for psychological interpretation of self-identity plots: an empirical study. J. Construct. Psychol. 11, 49–58

Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., and Campbell, D. T. (2001). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inferences. Boston/New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Shcheglova, M. (2010). An Integrated Method to Assess Consumer Motivation in Difficult Market Niches: A Case of the Premium Car Segment in Russia. Available online at: https://depositonce.tu-berlin.de/handle/11303/2685 (accessed September 25, 2020).

Sinnott, R. (2000). Knowledge and the position of attitudes to a european foreign policy on the real-to-random Continuum. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 12, 113–137. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/12.2.113

Slater, P. (1977). The Measurement of Intrapersonal Space by Grid Technique, Vol. II. London: Wiley.

Walker, B. M., and Winter, D. A. (2007). The elaboration of personal construct psychology. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 58, 453–477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085535

Weber, M. (1992). Soziologie. Weltgeschichtliche Analysen. Politik, 6. Aufl. Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner.

Wiesner, C., and Harfst, P. (2019). “Legitimität als ‘essentially contested concept”’, in Legitimation und Legitimität in vergleichender Perspektive, eds. C. Wiesner and P. Harfst (Wiesebaden: VS Springer), 11–32.

Zürn, M. (2011). Perspektiven des demokratischen Regierens und die Rolle der Politikwissenschaft im 21. Jahrhundert. Politische Vierteljahresschrift 52, 603–635. doi: 10.5771/0032-3470-2011-4-603

Zürn, M. (2012). Autorität und Legitimität in der postnationalen Konstellation. Leviathan 40, 41–62. doi: 10.5771/9783845245072-41

Keywords: legitimacy, European Union, mixed-methods, repertory grid, comparative politics

Citation: Osterberg-Kaufmann N (2022) Innovating Empirical Research on Legitimacy: Repertory Grid Analysis. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:832250. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.832250

Received: 09 December 2021; Accepted: 15 June 2022;

Published: 15 July 2022.

Edited by:

Claudia Wiesner, Fulda University of Applied Sciences, GermanyReviewed by:

Johan Adriaensen, Maastricht University, NetherlandsMarcus Eisentraut, GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, Germany

Copyright © 2022 Osterberg-Kaufmann. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Norma Osterberg-Kaufmann, bm9ybWEub3N0ZXJiZXJnLWthdWZtYW5uQGh1LWJlcmxpbi5kZQ==

Norma Osterberg-Kaufmann

Norma Osterberg-Kaufmann