94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 27 April 2022

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.823071

This article is part of the Research TopicOrigins, Foundations, Sustainability and Trip Lines of Good Governance: Archaeological and Historical ConsiderationsView all 14 articles

The archaeology of collective action addresses a widespread myth about the past–that premodern societies were despotic, and only produced public goods when everyday people convinced a separate and distinct ruling class to provide them. Archaeological evidence from the Indus civilization (~2600–1900 BC), home to the first cities in South Asia, reveals that Indus cities engaged in a remarkably egalitarian form of governance to coordinate different social groups, mobilize labor, and engage in collective action, thus producing a wide range of public goods. These public goods included, but were not limited to, water infrastructure, large public buildings, and urban planning–all of which helped Indus cities invent new technologies, grow, and thrive. Many intersecting institutions contributed to Indus governance, including civic bureaucracies that gathered the revenue necessary to mobilize labor in pursuit of collective aims, as well as guild-like organizations that coordinated the activities of numerous everyday communities and ensured the equitable distribution of information within Indus cities. A wide range of large and small public buildings, information technologies, and protocols for standardized craft production and construction attest to this egalitarian governance. Through these institutions, Indus governance incorporated the “voice” of everyday people, a feature of what Blanton and colleagues have described as good governance in the past, in absence of an elite class who could be meaningfully conceptualized as rulers.

Political theorists often assume that the benefits of governance only accrue to people who sacrifice their political and economic power to a permanent ruling class. This assumption can lead the people of otherwise democratic societies to tolerate political strategies that turn leaders into autocrats and shut everyday people out of the political process. This is a “tripwire” that is well-known to political scientists (Waldner and Lust, 2018) and has also been addressed by archaeologists interested in the diversity of human political systems (Blanton et al., 2021). Despite the efforts of these researchers, however, it remains a pervasive myth that many transformative features of human economies come about only through the canny largess of political-economic elites.

Archaeological evidence from the Indus civilization (~2600–1900 BC), home to the first cities in South Asia, reveals that public goods emerged long before a ruling class. Indus cities supported a sophisticated Bronze Age political economy, where growth was driven by diverse groups of people who practiced different economic specializations, including intensified agropastoralism and craft production (e.g., Kenoyer, 1997a; Vidale, 2000; Meadow and Patel, 2003; Madella and Fuller, 2006; Wright, 2010; Pokharia et al., 2014; Ratnagar, 2016; Petrie and Bates, 2017). It would be naïve to assume that the interests of these communities were always aligned. It is not hard to imagine herders negotiating for better access to land, artisans disagreeing over how many ornaments to make, or farmers debating a planting sequence that distributes the demand for harvest labor. And yet, considering the range of potential conflicts that could have atomized them, Indus communities nonetheless adopted forms of governance that allowed them to accomplish extraordinary feats of social coordination, standardizing construction techniques and planning urban development, assembling and maintaining drainage systems, constructing massive city infrastructures that required the labor of thousands and creating systems of materializing information that extended from the foothills of the Himalaya to the Arabian Sea.

The archaeology of the Indus civilization therefore challenges the widely-held myth that public goods–those that benefit everyone who invests labor in their production as well as many who do not–must be provisioned by rulers who are forced to accommodate citizen demand. Debate surrounding this assumption has long shaped the interdisciplinary study of collective action and public goods (e.g., Olson, 1965; Levi, 1988; North, 1990; Ostrom, 1990). Evidence from the past in fact reveals that there are many pathways to collective action (Blanton and Fargher, 2008; Carballo, 2013; Feinman and Carballo, 2018), reinforcing Ostrom's (1990) critique of the conventional argument that societies only produce public goods when everyday people place pressure on the elite (e.g., Levi, 1988). People have in fact engaged in collective action, often at very large scales, in societies where there are no elites to speak off. With access to data from many such premodern societies, archaeologists are particularly well-positioned to address the origins of public goods. Often, the publicness and privateness of goods can be inferred from the material constraints on their use. The high accessibility of public goods contrasts with the restricted accessibility of private goods, those that were constrained to a subset of people. Given that the people of the Indus built their cities in absence of all but trivial inequality (Green, 2021), it is worth asking: how did they coordinate governance beyond households? How did everyday people make and implement political decisions that resulted in forms of collective action that traditional political theories hold must be imposed from above? In this article, I argue that civic deliberation and bureaucracy, as well as guild-like organizations, were prominent features of Indus governance, incorporating significant proportions of urban populations into collective decision making and implementation, allowing them to engage in collective action without investing political authority within a fixed social stratum. The result was “good governance,” that which responded to the needs of everyday people (sensu Blanton et al., 2021), over much of the Indus civilization's urban development.

Governance is the way that a society directs its collective affairs. Across disciplines, many theorists hold that governance is produced by the institutions that emerge from and cross-cut social groups, creating rules, norms and practices that shape a society's distribution of power and resources (e.g., Olson, 1965; North, 1990; Ostrom, 2000; Levi-Faur, 2012; Bondarenko et al., 2020). Research on governance is often biased toward contemporary or recent historical social contexts, however governance is a human universal. It takes place within households and between nations. Different forms of governance produce drastically different societies. When governance admits only a small number of people into decision-making, it tends to constrain the benefits collective action toward a small minority, a vicious cycle that is enabled by and creates predatory and extractive social institutions (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2013). By contrast, “good governance,” a concept that began as the stated goal of international development, now describes institutional arrangements that produce public goods, such as civic infrastructure, sanitation, transportation, and other things considered essential for economic prosperity (Rothstein, 2012). This duality, as well as the key role governance plays in generating and dispersing political and economic benefits–makes collective action theory a key tool for investigating it.

Collective action theory is concerned with identifying the conditions under which people coordinate their labor to solve common problems. Public goods often involve substantial labor investment, so making them tends to require collective action. However, collective action is often implemented from the “top-down” by people who command considerable control of a society's political and economic resources, such as the agents of a state administration. There is therefore significant debate about what kinds of agents and institutions are most likely to achieve collective action within collective action theory. Some theorists have focused on how “predatory” leaders muster revenues for collective action (e.g., Levi, 1988), while others argue that sustainable collective action is the product of institutional arrangements that draw upon knowledge and action at appropriate social scales (e.g., Ostrom, 2010). The latter theory builds on the observation that public goods emerge through coordination between a diverse range of intermediate and local institutions that often have non-hierarchical relationships to one another and to the broader “state” (Ostrom, 1990). In other words, good governance can emerge through interactions enacted from the “top-down,” or through interactions from the “bottom-up” (Rothstein, 2009, 2012). What seems to be essential is wide participation in the institution-formation process. Societies are therefore most likely to produce public goods when governance is inclusive, incorporating many everyday people into directing collective affairs (e.g., Dahl, 1989; Ostrom, 1990, p. 45).

Evidence from the past reinforces these insights and offers a wide comparative frame that draws on archaeology to more fully addressing variation in political forms (e.g., Blanton et al., 1996, 2020, 2021; Blanton, 1998, 2010; Blanton and Fargher, 2008; Carballo, 2013; DeMarrais and Earle, 2017; Feinman, 2018). Initially, collective action theory helped advance critiques of neo-evolutionary theory within the discipline of archaeology, contrasting the impact of corporate political strategies–those that incorporated commoners in governance–from network political strategies that excluded commoners and forged connections between elites (Blanton et al., 1996). As archaeological debate proceeded, it became apparent that the evolutionary distinction between “commoner” and “elite” was not always useful to understanding past social changes (Blanton, 1998). Collective action theory offered an alternative framework, revealing a political variable that had gone understudied in past societies, even though it was clearly responsible for explaining many phenomena that were central to neo-evolutionary theory (Blanton and Fargher, 2008). Strong indicators of collective action included public goods–things like transportation and water management infrastructures–but redistributive economies, equitable taxation, institutional accountability, and bureaucratization (Blanton and Fargher, 2008, p. 133–248). These phenomena were not mutually exclusive and have been used to characterize the degree of collectivity apparent in past societies (Feinman, 2018; Feinman and Carballo, 2018). This reframing has led to several important insights. For example, it is clear that one of the long-term patterns that has emerged over the millennia has been steady increases in different human societies' capacity for collective action (Carballo, 2013). Another insight is that collective societies–those characterized by corporate political strategies–appear to have been more dependent on “internal” sources of revenue like agrarian taxation, while less collective societies appear to be those more dependent on exclusionary political strategies that focused on “external” resources (Blanton and Fargher, 2008; Feinman, 2018; Feinman and Carballo, 2018). Past societies that draw on internal revenues to engage in collective action are more likely to produce public goods and can be predicted to have developed institutions that enable wide participation and accountability in the political process (Blanton et al., 2021).

But what kinds of institutional arrangements create good governance? A focus on institutions is adaptable to evidence from the past because it eliminates the need to assume that governance was public, private, market or state based. An institutional approach thereby helps archaeologists compare different kinds of integrative, cross-cutting institutions that facilitated the mobilization of labor in the past without imposing assumptions from the present (Bondarenko et al., 2020; Holland-Lulewicz et al., 2020). Traditionally, archaeologists have theorized that such institutional arrangements were limited to “states,” a social type used by neo-evolutionary theorists to describe a combination of extractive social classes and predatory institutions thought to emerge alongside one another: institutions like militaries, big and impersonal administrations, and long-distance exchange networks (e.g., Childe, 1950; Flannery, 1972; Service, 1975; Wright and Johnson, 1975; Weber, 1978). This definition of the state has been subject to decades of critique by archaeologists, who must square it with evidence that different features commonly associated with the state materialized in different social contexts at different times for different reasons (e.g., Yoffee, 2005; Pauketat, 2007; Jennings, 2016). Archaeologists now take pains to document the different ways features of the neo-evolutionary state have been combined in the past (e.g., Wright, 2002; McIntosh, 2005; Smith, 2009; Feinman, 2013; Jennings, 2016). One recurring insight is that many of the political interactions between the political institutions within “states” were often “heterarchical,” or unranked, institutions (sensu Crumley, 1995). This is not to say that political hierarchies were precluded by heterarchical institutional arrangements, or that all political interactions were horizontally distributed. Rather, heterarchical arrangements require archaeologists to think more broadly about political organization. Like all complex systems, premodern societies often incorporated many intersecting institutions that were not always ranked or could be ranked in different ways. This flexibility probably made some premodern societies more sustainable in the past (e.g., Scarborough, 2009). Good governance is not necessarily more heterarchical, but heterarchical institutional arrangements could certainly have played a role in inclusive political decision-making and collective action in the past.

There have been many surprising instances of increases in political and economic scale that unfolded without incurring more than trivial inequalities. Egalitarianism has therefore appeared in many large-scale premodern societies that would have surprised neo-evolutionary theorists. This claim was foreshadowed by Blanton (1998, p. 151), who argued that some early states employed egalitarian political strategies. Egalitarian here does not mean perfect equality in all spheres of life, but rather a prevalence of firm limits on exclusionary political power. Building on these points, I reiterate that elites or ruling classes are not prerequisites to collective action or the production of public goods, but epiphenomena associated with a restricted range of political-economic trajectories. Thus, rather than search for elite agency to explain past social transformations, like the emergence of public goods, it is often more fruitful to investigate the range of political arrangements people have made to engage in collective action (Carballo, 2013), examine connections between collective action and political economy (DeMarrais and Earle, 2017), and explore articulations between collective action and other indicators of governance (Feinman and Carballo, 2018). Governance activities in many past societies were often dispersed and emerged from the bottom-up (Thurston and Fernandez-Gotz, 2021). In fact, I would add that by distributing political and economic benefits among everyday communities, good governance can further be predicted to contradict the expectations of neo-evolutionary theories of state formation by producing egalitarianism in societies with coordinated governance and large-scale collective action. After all, if inequality and the scale of governance always increase together, then there would really be no such thing as good governance.

One advantage of this theoretical frame is that it can be used to make a range of predictions regarding how good governance materialized in the past. In addition to reconstructing evidence of public goods from past societies, I would suggest that good governance can be inferred from deliberative spaces that help incorporate everyday people into political decision-making processes. There are other archaeological indicators of governance as well. Blanton and Fargher (2008) argued that collective action in the past is associated with a process called “bureaucratization.” This concept of bureaucratization diverges from Max Weber's (1978) evolutionary type, which holds that bureaucracy replaced tradition-based systems of administration only in the 19th century AD due to rising capitalism. Bureaucratization, rather, can be conceptualized as the expanded implementation of governance into new spheres of a political economy by specialists working on behalf of institutions that crosscut different social groups–what Blanton and Fargher (2008, p. 166) call “government by office.” An indicator of bureaucratization is therefore the construction of institutional spaces set aside to facilitate the implementation of coordinated governance and collective action. Thus, good governance is associated both with the creation of deliberative spaces for accommodating citizen voice, and with “offices,” spaces that help specialists coordinate the activities of multiple social groups by facilitated activities like planning, organization, monitoring, and execution.

The initial formation of cities represents a profound challenge for good governance. Urban life is defined by regular interactions amongst strangers (e.g., Jacobs, 1961). The defining trait of many of the world's first cities were population aggregation that required novel forms of political and economic organization (e.g., Smith, 2003; Birch, 2014; Jennings, 2016; Gyucha, 2019), as well as unprecedented technological innovation and economic growth (e.g., Ortman and Lobo, 2020), especially in their initial periods. Initial urban governance is therefore demanding because urban communities faced a wider range of social and economic conditions than their pre-urban predecessors, and cities needed public goods to prosper (e.g., Childe, 1950; Fletcher, 1995; Sherratt, 1995; Wright, 2002; Smith, 2003, 2019; Cowgill, 2004; Bettencourt et al., 2007; Feinman, 2011; Ortman et al., 2016). The demand for technologies that enable exchange amongst strangers–itself a public good–is also closely associated with changes in governance. The first urban communities needed new tools to effectively keep track of credits and debts amongst strangers. The tools and techniques employed to materialize and represent information, or a society's “means of specification” (Green, 2020), can be distributed in different ways, and have major implications for governance. In egalitarian urban societies, we find the means of specification distributed amongst everyday households, while in stratified societies with predatory institutions, these same technologies were monopolized to create extractive forms of interest-bearing debt (Green, 2020). Likewise, collectivity produced a more widely distributed form of collective computation, while authoritarianism limits the flow of information (e.g., Feinman and Carballo, 2022).

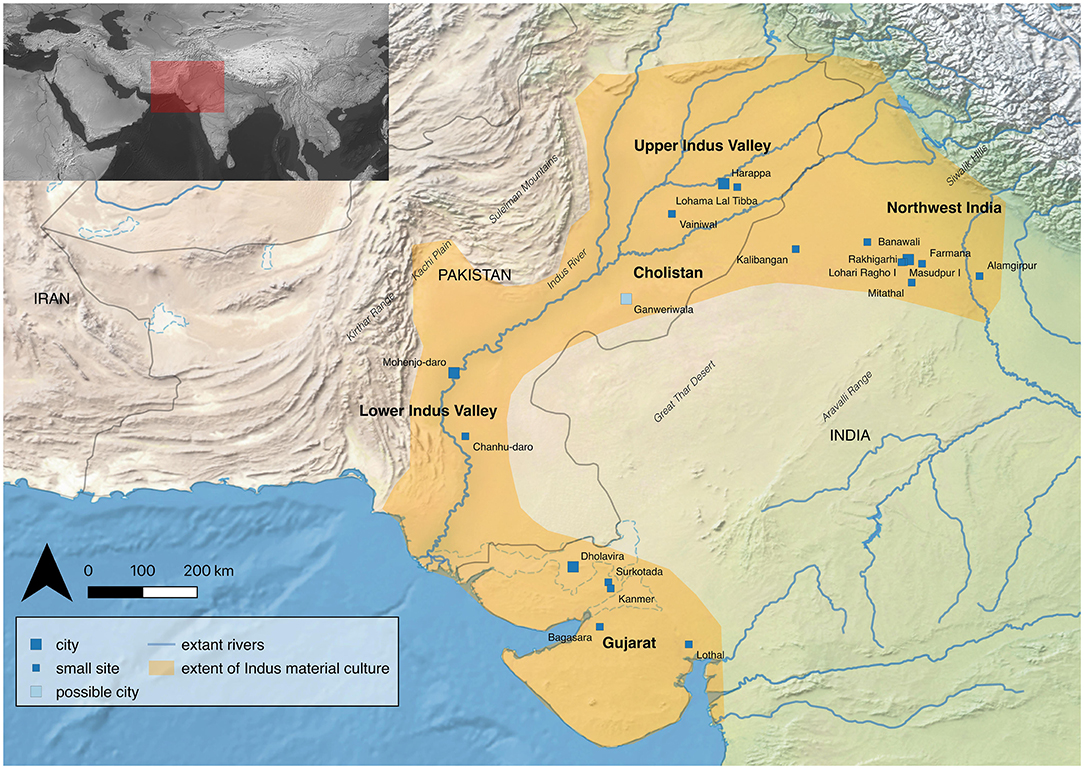

One of the world's first great urbanizations produced the Indus civilization, whose settlements emerged over an extensive area that extends from the Himalaya to the Arabian Sea (Figure 1). The geographical extent of the Indus civilization eclipsed that of its contemporary societies in Mesopotamia and Egypt (Possehl, 1999). People built Indus settlements within a wide range of environments, from the semi-arid coasts of Gujarat to the well-watered plains of northwest India. Life in these contrasting regions required a flexible and diversified agropastoral economy that responded to a wide variety of local contexts (e.g., Weber, 1999; Madella and Fuller, 2006; Chase, 2010; Wright, 2010; Petrie et al., 2016; Bates et al., 2017; Petrie and Bates, 2017). Five Indus settlements are often identified as cities due to their size, sophisticated Bronze Age technologies, numerous houses, and range of different kinds of structures. Four of these sites, Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Rakhigarhi and Dholavira, have been subject to extensive excavations (see Lahiri, 2005; Wright, 2010; Petrie, 2013a; Ratnagar, 2016; Green, 2021). Archaeological surveys have also produced substantial data pertaining to the spatial organization of the smaller sites immediately surrounding Harappa (Wright et al., 2003, 2005) and Rakhigarhi (Singh et al., 2010, 2011, 2018a,b, 2019; Green and Petrie, 2018). Establishing the maximum extent of these sites is a matter of ongoing debate, as there are many formation processes that impact area estimates. However, it is clear that Indus cities were more extensive than the pre-urban settlements that emerged before them in the same region. The extent of many of these pre-urban settlements cannot be established due to the overlying remains of settlements that date to the urban phase. However, at Harappa (e.g., Meadow and Kenoyer, 2005) and Rakhigarhi (e.g., Nath, 1998, 1999, 2001), pre-urban material culture is reported from only around a quarter of the total site area. Moreover, settlements that were abandoned prior to urbanization tended to be relatively small. For example, Kot Diji, a type-site of the pre-urban phase, appears to have extended over less than three hectares (Khan, 1965). Most scholars would agree that the most densely built part of each Indus city encompassed a core area that (often greatly) exceeded 50 hectares. Much of this settlement area was dedicated to houses–domestic residential structures that incorporated courtyards, wells, hearths, and sometimes specialized craft production areas (Sarcina, 1979; Cork, 2011; Green, 2018). The growth of Indus cities coincides with substantial evidence for changes in governance.

Figure 1. Map of the Indus civilization during its urban phase. Included are the sites that are often presented as cities, as well as smaller settlements that are discussed in this article, where archaeologists have found substantial evidence of collective action. Map assembled using QGIS 3.16 (www.qgis.org) and employs a Nature Earth basemap (www.naturalearth.com).

Indus governance can be inferred from different categories of archaeological evidence. For example, substantial brick walls and platforms provide direct evidence of collective action, an outcome of governance, because there would have been no way for a single household or social group to mobilize sufficient labor on its own. Other forms of evidence are less direct. A hypothetical ledger detailing labor obligations may record actual accumulations of past revenue or the aspirations of a presumptive government whose desire for revenue was greater that its capacity to gather it (e.g., Richardson, 2012). Rules and protocols that crosscut social groups, and the institutions that form them, are perhaps the most basic indicator of governance. However, unless such rules are written down, they do not leave direct material evidence. At the same time, the repeated adherence to a standard of production can indirectly attest to shared rules and protocols. And indeed, standardization has long been recognized as a basic concept for the analysis of archaeological datasets (e.g., Rice, 1991; Eerkens and Bettinger, 2001; Roux, 2003). The production of standardized artifacts is often taken as evidence that they were produced by a subset of specialists to meet the demands of a larger population of users. However, multiple groups of specialists also often adhere to common standards, a pattern that we can use to infer governance of production, especially when it co-occurs with evidence of collective action.

Indus cities are recognizably “Indus” because the people who lived in them produced a shared material culture. Indus assemblages include a wide range of shared ornament types, pottery styles, bronze metallurgy, and stamp seals–technologies that have been subject to considerable study (Wright, 1991, 1993; Kenoyer, 1992, 1997a; Vidale, 2000; Vidale and Miller, 2000; Menon, 2008; Agrawal, 2009). While assemblages from Indus cities tend to receive the most attention, they actually represent only a small subset of the settlements that contributed to the Indus civilization's material culture (Fairservis, 1989; Wright, 2010; Sinopoli, 2015; Parikh and Petrie, 2019). Extensive archaeological surveys have uncovered hundreds of small archaeological mounds across a very wide area (e.g., Singh, 1981; Joshi et al., 1984; Possehl, 1999; Wright et al., 2003, 2005; Kumar, 2009; Rajesh, 2011; Pawar, 2012; Chakrabarti, 2014; Dangi, 2018; Green and Petrie, 2018; Green et al., 2019). Indus cities therefore did not hold a monopoly on these technologies, which were widely distributed across the civilization's extent, and employed alongside many local forms of craft production (Possehl and Herman, 1990; Meadow and Kenoyer, 1997; Wright, 2010; Chase et al., 2014; Parikh and Petrie, 2016; Patel, 2017; Petrie et al., 2018). Many of the pottery and ornament styles that have been found in urban contexts have also been identified at these smaller settlements, which were, in some cases, dozens of kilometers from the nearest urban center (Wright et al., 2003, 2005), a characteristic that Parikh and Petrie (2019) have characterized as “rural complexity.”

Governance is evident in the shared styles that permeated the production of many different Indus crafts. Indus artisans made a lot of different kinds of things, from elaborate stone pillars to tiny steatite microbeads (Wright, 1991; Kenoyer, 1997a; Vidale, 2000; Miller, 2007a). Though these crafts were produced by multiple groups of artisans, many common standards patterned their production–shared ideas and practices about how to make things, regardless of material (Miller, 2007b; Wright, 2010). For example, Indus artisans often incorporated the same materials into different technologies, many of which had to be acquired from locations far from the point of production (Lahiri, 1990; Kenoyer, 1997a; Ratnagar, 2003). While the use of exotic materials in urban contexts is not particularly remarkable, it is striking that Indus artisans did not use all of the different sources of raw materials accessible within their civilization's broad extent. Artisans preferred–or were perhaps even constrained to–a limited number of specific sources of stone, like steatite, even when local materials were more readily available (e.g., Law, 2006, 2011). Likewise, shared protocols for production patterned different crafts, resulting in a range of cross-craft “technological styles” (Lechtman, 1977; Wright, 1993). For example, Indus assemblages were marked by considerable “technological virtuosity,” or crafts that incorporated very high levels of skill, knowledge, and labor and invested these into small things, like portable beads and ornaments (Vidale and Miller, 2000). Likewise, a “talc-faience industrial complex” is evident across different crafts, a common set of materials and techniques used produce exceptionally large quantities of artificial ornaments, such steatite beads, and faience bangles, which were widely distributed amongst everyday people (Miller, 2007a). Indus artisans also shared a proclivity for radically transforming raw materials, such as steatite and carnelian, into new forms, and creating entirely artificial materials like stoneware or faience. Wright (2010, p. 239) has called this technological style a “transformative mindset.” Though many different groups engaged in craft production, the technological styles that linked these groups reveals substantial integration and suggests a degree of coordination among artisans that indirectly attests to a particular form of governance.

Indus seals (Figure 2) are a hallmark category of artifacts from the Indus civilization's urban phase (Mackay, 1931; Rissman, 1989; Franke-Vogt, 1991; Parpola, 1994; Law, 2006; Kenoyer, 2007; Kenoyer and Meadow, 2010; Green, 2016; Jamison, 2018). These small stone stamps had intaglio engravings that could be impressed into clay sealings on containers and doors, materializing information that could serve as a kind of record of socio-economic interactions, a practice that is attested across Eurasia beginning in the Neolithic (e.g., Jarrige et al., 1995; Pittman, 1995; Akkermans and Duistermaat, 1996). The production of Indus seals, themselves quite intricate, required high levels of skill and complex production sequences. They epitomized Indus technological virtuosity as well as adherence to common standards, with a range of standardized forms and images that were engraved on seal after seal (Rissman, 1989; Ameri, 2013; Frenez, 2018). Most Indus seal carvings depict an animal along with an inscription in an undeciphered script (e.g., Mackay, 1931). It has long been argued that such motifs served the emblems of different social groups, while the script records the name of a particular seal user (Fairservis, 1982; Kenoyer, 2000; Vidale, 2005; Frenez and Vidale, 2012; Frenez, 2018). Regional variation in the prevalence of particular seal motifs in an assemblage (e.g., Ameri, 2013; Petrie et al., 2018) suggest that different kinds of social groups–rural and urban–used seals to make sealings. And yet, the vast number of people who used Indus seals relied on a remarkably standardized tool–a square stamp ~2.5 cm on each side with a restricted range of motifs–to specify things (Green, 2015, 2020).

Figure 2. A sample of seals from the Indus civilization. Reprinted from Green (2020) with gratitude to the Archaeological Survey of India. (A) Unicorn (M-143|63.10/23, DK 10323), (B) buffalo (M-128|63.10/18, DK 8390), (C) rhinoceros (M-276|63.10/149, DK 4812), (D) elephant (M-279|63.10/27, DK 7675), (E) short-horned bull (M-251|63.10/44, DK 5791), (F) figure in tree with tiger (M- 310|63.10/184, DK 5969), (G) seated figure (M-305|63.10/62, DK 3882), (H) zebu bull (M-261|63.10/133, DK 8390), (I) human/animal composite (K-50|68.1/8). All of these seals are curated in the Central Antiquities collection of the Archaeological Survey of India and were photographed by the author.

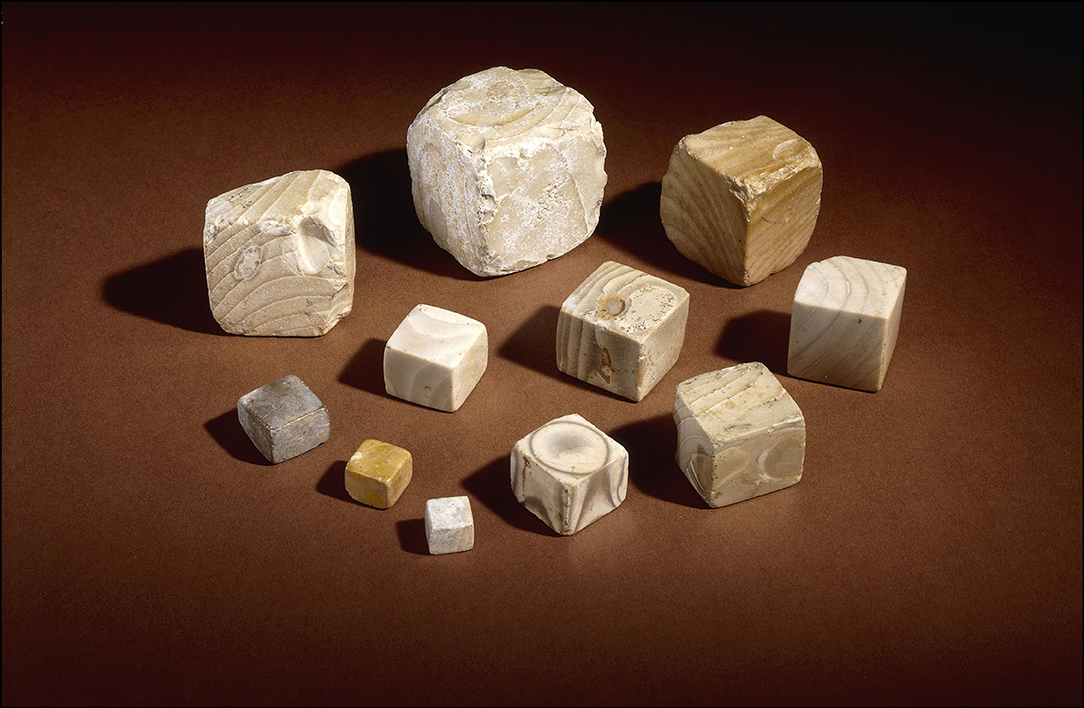

Stone weights are also a prominent component of Indus assemblages (Miller, 2013). They formed a system a measurement which would not have worked unless the weights were highly standardized, incorporating weights that ranged from <1 g to well over 10 kg (Figure 3). Indus weights were made from a wider range of harder stones than seals, which nonetheless had to be sourced from the highlands surrounding the Indus civilization (Law, 2011). Many classic examples of Indus weights were cut from chert from the Rohri Hills proximal to Sindh (Kenoyer, 2010). Indus weights have been recovered from rural as well as urban sites, suggesting that a single authority operated throughout the Indus civilization. The spatial extent of the weight system has even been cited as evidence in proposals that the Indus civilization was an empire (e.g., Ratnagar, 2016), though it should again be noted that the Indus civilization lacks convincing evidence of an emperor (Green, 2021). Moreover, in contrast with the weight systems of the Indus civilization's contemporary societies in Mesopotamia–which do provide clear evidence of a ruling class–Indus weights were unmarked, suggesting that they comprised a single system that did not compete with any others across the Indus civilization's vast extent (Rahmstorf, 2020). Thus, in the Indus, it appears to have been unnecessary for weight users to specify which weight system they were employing. Indus weights were the only weights in many of the contexts in which they were used, suggesting very high levels of coordination amongst the artisans who created the weights.

Figure 3. Weights from the Indus civilization. These weights were excavated from Mohenjo-daro and are curated by the British Museum. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share-Alike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

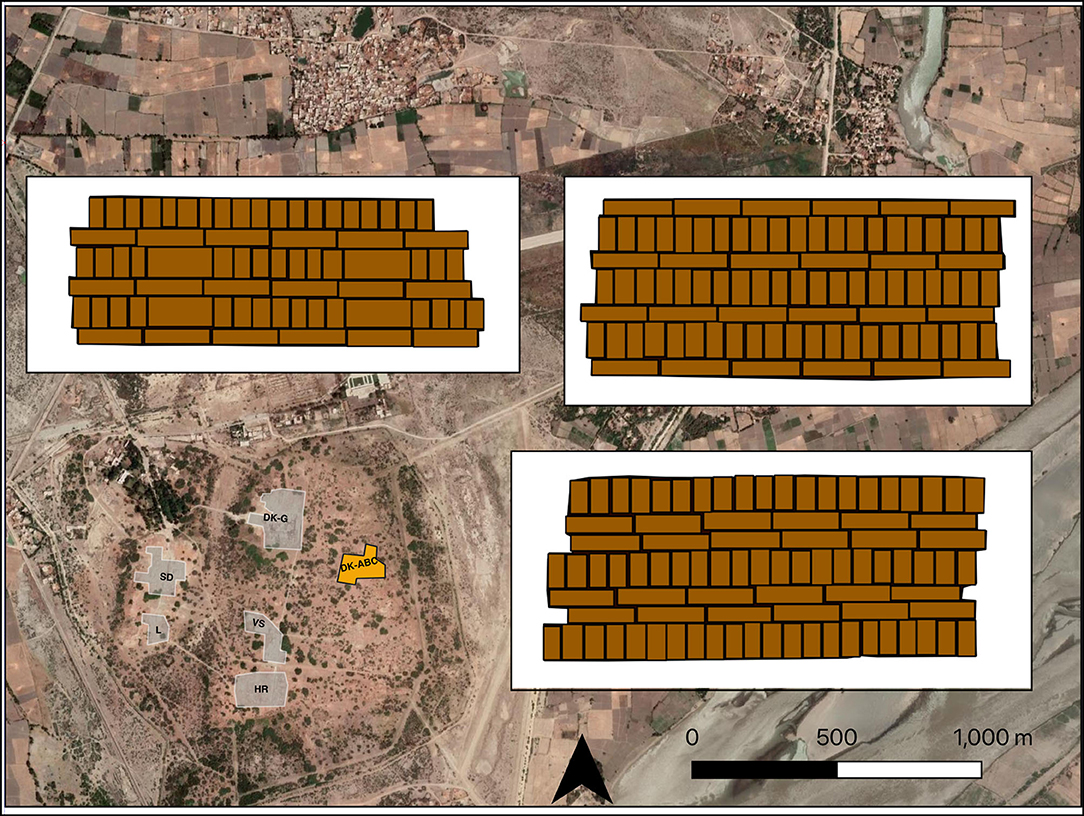

A closer look at the architectural matrix of Indus cities reveals the degree to which common standards contributed to the growth of Indus settlements. While some Indus settlements were made of stone, the majority were comprised of structures assembled from thousands of mud or baked bricks. These bricks had to be produced outside of the settlements themselves, mined from favorable sediments, tempered, shaped, left to dry, and then sometimes fired in massive kilns. In describing the bricks of Mound F at Harappa, Vats (1940, p. 21) writes:

Like all other buildings of the various strata, this amazing complex is composed of well burnt bricks of fine texture which are laid throughout in good tenacious mud. The bricks measure 11 by 5 ½ by 2 ½ by 3 in., of which the chief interest lies in the scientific proportion of two widths to the length–a size of which makes for good structural bonding.

The bricks at Mohenjo-daro adhere to the same ratio. Mackay (1931, p. 265) noted that comparable brickmaking techniques did not appear in Mesopotamia until nearly a 1,000 years after their debut in South Asia. The high quality and scale of Indus brick assemblages is clear evidence of mass production, which would have required substantial coordination among many brick producers. Adherence to common standards made it possible for Indus builders to employ header-stretcher masonry techniques, and create durable joints, tidy corners, and sharp lines (Figure 4). Bricks could also be subdivided to create a range of different kinds of platforms, staircases, vents, and other structural features. Common standards also made it easier to create wedge-shaped variants that interlocked with other bricks and were essential for the construction of waterproof wells (Jansen, 1993a; Wright, 2010). The high quality of Indus brick masonry is one of the reasons so much of Mohenjo-daro's architecture remain standing to be studied by archaeologists today (e.g., Jansen, 1993a).

Figure 4. Masonry techniques employed at Mohenjo-daro that highlights the sophistication of the brick-making technology. Illustration redrawn from Marshall 1931: LXVII. Plans from Marshall (1931) and Mackay (1938) were digitized and extrapolated in three dimensions using QGIS 3.16 (www.qgis.org). Images is projected over Google Earth Satellite Imagery (accessed 2021).

The production activities considered thus far involved the coordination of labor from many different households (e.g., Wright, 1991). Guild-like organizations, which have been inferred from evidence of technological virtuosity and decentralized production, likely contributed to the coordination of different groups of artisans (e.g., Wright, 2010, p. 327). Such organizations would have comprised an integrating institution capable of producing, reproducing, consolidating, mobilizing, and preserving the knowledge and skill necessary to engage in different production activities. A similar model of Indus craft organization was first suggested by Rissman (1989), who posited that the restricted range of seal motifs found at different Indus cities revealed that multiple workshops operated independently of specific locations of production. This model holds that production activities were undertaken by multiple specialist groups who accumulated resources for the production and reproduction of the craft apart from households, while also standardizing production practices. Groups of artisans specialized in different techniques and shared their skills with one another, applying knowledge gained from the production of one kind of craft to a range of different materials (Miller, 2007a,b). The result was a wide range of highly standardized craft objects produced in very large numbers by many different groups of artisans. In nearly every study of the spatial distribution of finished craft objects in Indus settlements (e.g., Vidale and Balista, 1988; Miller, 2000; Wright et al., 2003, 2005), they are most often found in everyday households–they were not meaningfully restricted. Interactions among guild-like organizations may help explain how different technological styles emerged heterarchically or from the bottom-up.

Collective action leaves a robust material footprint. Detecting archaeological evidence of collective action is straightforward–the archaeological record is full of big things that simply could not have been built without the labor of many people. Prominent examples include the temple complexes at Teotihuacán (e.g., Cowgill, 2015), the monumental platforms in the early settlements along the Andes coast (Pozorski and Pozorski, 2018), Pepys' pyramid in ancient Egypt (Wenke, 2009) and the Temple Oval at Khafajah in Mesopotamia (Delougaz, 1940). Large non-residential structures were also built in the Indus, providing direct evidence for collective action (e.g., Smith, 2016; Wright, 2016). Archaeologists have identified many examples of such buildings, along with large-scale investments in infrastructure in Indus settlements (Wright, 2010). Examples include the massive structures of the Western Mound at Mohenjo-daro, such as the Great Bath, and the erroneously named “Stupa” at Mohenjo-daro (Marshall, 1931, 23). Detailed discussions of these structures are available in a range of studies (e.g., Fentress, 1976; Jansen, 1993b; Verardi and Barba, 2010; Vidale, 2010). Like many of the large non-residential structures of Mohenjo-daro, the Great Bath was built atop a massive brick platform (e.g., Jansen, 1993a; Mosher, 2017), which would have demanded the investment of many hours of labor from many people. Possehl (2002, p. 103) speculated that a single platform would have required 4 million days of labor. Even at Harappa, where British colonial brick-mining activities destroyed much of the city's architecture (Vats, 1940, p. 17; Lahiri, 2005), excavators reported substantial foundation platforms that could have supported large non-residential structures (Vats, 1940, p. 12–17). The Harappa Archaeological Research Project has revealed that massive, gated walls surrounded each of Harappa's neighborhoods (Meadow and Kenoyer, 1997, 2005; Wright, 2010; Kenoyer, 2012). Evidence of collective action has also been reported in plans of excavations at Dholavira, which reveal the construction of city walls, gateways, and a series of interconnected reservoirs that were cut deeply into the bedrock surrounding the city (Bisht, 2005, 2015).

Archaeologists have also found large non-residential structures in the Indus civilization's smaller settlements, indicating that cities were not the only settlements that could muster substantial labor for collective action. Thick walls surround the smaller-scale sites of Surkotada (Joshi, 1990), Kalibangan (Lal et al., 2015) and Kanmer (Kharakwal et al., 2012); and internally divided different parts of Banawali (Bisht, 1987) and Bagasara (Bhan et al., 2004). A massive structure that could have served as a dock and another that could have been used as a warehouse were constructed at Lothal (Rao, 1973, 1979). Excavators have identified smaller buildings dedicated to specialized production at Chanhu-daro (Mackay, 1943; Sher and Vidale, 1985), and the brick platforms have been reported at the Harappa-satellite sites of Vainiwal (Wright et al., 2003) and Lahoma Lal Tibba (Wright et al., 2005). Some of these structures rivaled those constructed in the cities in terms of size and complexity and would likely have required the coordination of labor from neighboring settlements.

Revenue is income expended through governance to undertake collective action. While buildings with substantial storage capacities may serve as indirect evidence, direct inferences about past revenues can rarely be made using archaeological evidence alone. Due to the vagaries of preservation, it is rare that accumulations of resources can be directly associated with forestalled instances of administered collective action. Most examples of storage spaces provide better evidence of household provisioning (Bogaard et al., 2009) or agrarian risk buffering (Halstead and O'Shea, 2004), though these activities may not easily be distinguished from past efforts to mobilize revenue. Seals and sealings can be used to make indirect inferences about revenue. This is because seals and sealings were used to monitor claims on resources held by different social groups (Green, 2020), allowing resources to remain physically distributed throughout society in the form of reciprocal obligations amongst everyday people and other corporate groups (e.g., Hayden, 2020). This form of “virtual” revenue would have been predicated on the widespread availability of information, which would only have been accessible through the means of specification. Caches of materialized information–in the form of clay “sealings” impressed with seals–attest to efforts to record information about resource accumulation and expenditure. Similar technologies have been recovered from other early contexts in the Middle East and South Asia, where they are often considered evidence of “administration” (e.g., Ferioli and Fiandra, 1983; Frangipane, 2007; Duistermaat, 2012; Ameri et al., 2018). Indus assemblages reveal a clear concern with such forms of revenue. A cache of approximately 90 sealings attest to their use in a system of monitoring access to different kinds of lockers, containers, and structures at Lothal (Frenez and Tosi, 2005). This capacity to materialize information was remarkably widespread. Thousands of Indus seals, tools that allowed people to make sealings, have been recovered from sites located throughout the civilization's extent (e.g., Joshi and Parpola, 1987; Shah and Parpola, 1991; Parpola et al., 2010). More than 1,000 seals were recovered from the excavated areas of Mohenjo-daro alone (e.g., Mackay, 1931, 1938), and the vast majority of Indus seals were recovered from everyday households, not large non-residential structures (Franke-Vogt, 1991; Green, 2020). The distribution of seals likely reflects the distribution of control over resources, especially the internal resources of concern to everyday households, clearly situating the Indus on the collective side of the governance continuum and deeply embedding the “voice” of everyday households into its governance.

Indus weights similarly reveal a strong concern with revenue. They have been recovered in smaller numbers than seals, and they may have been employed in taxation. At Harappa, weights have been found in association with the gateway to one of the city's neighborhoods (Kenoyer and Miller, 2007). This association has only been preliminarily reported and does not appear to prevail across Indus sites, some of which did not have neighborhood walls or gates. What could have been taxed, and by whom, remains an open question. Still, seals and weights both reveal a common concern with monitoring economic transactions and keeping track of resources, and both would clearly have been useful in mobilizing revenue for collective action.

Deliberation is a key element of governance. Here I use the term in its widest sense to refer to a full range of group decision-making practices; everything from discussions among leaders to public rituals designed to build collective consensus. It is easier to deliberate when there are spaces available in which people can meet. Thus, the more space a society sets aside for deliberation, the more people can participate in its governance, and the greater the likelihood that everyday people will be able to agree to a particular course of collective action (e.g., Carballo, 2013; DeMarrais, 2016). Excepting palaces and temples, the wide range of different kinds of common spaces that past people have built to accommodate deliberation has not received adequate attention. Archaeologists argue that many societies incorporate public spaces that facilitate governance activities like deliberation. Drawing on settlement scaling theory (e.g., Ortman et al., 2016), Norwood and Smith (2021) hypothesized that “urban open space” may increase at a higher rate than population, though add that the kinds of open spaces established may be culture specific. Blanton and Fargher (2008) have long argued that large public buildings associated with deliberation are an indicator of collective action in a premodern society, and of good governance (Blanton et al., 2021). Feinman and Carballo (2022, p. 101; see also 2018) have further specified that communal or large-scale “…architecture that fosters access (e.g., open plazas, wide accessways, and community temples)” is a strong indicator of collectivity. As good governance is implemented at increasing socio-economic scales, so too does demand for deliberative spaces.

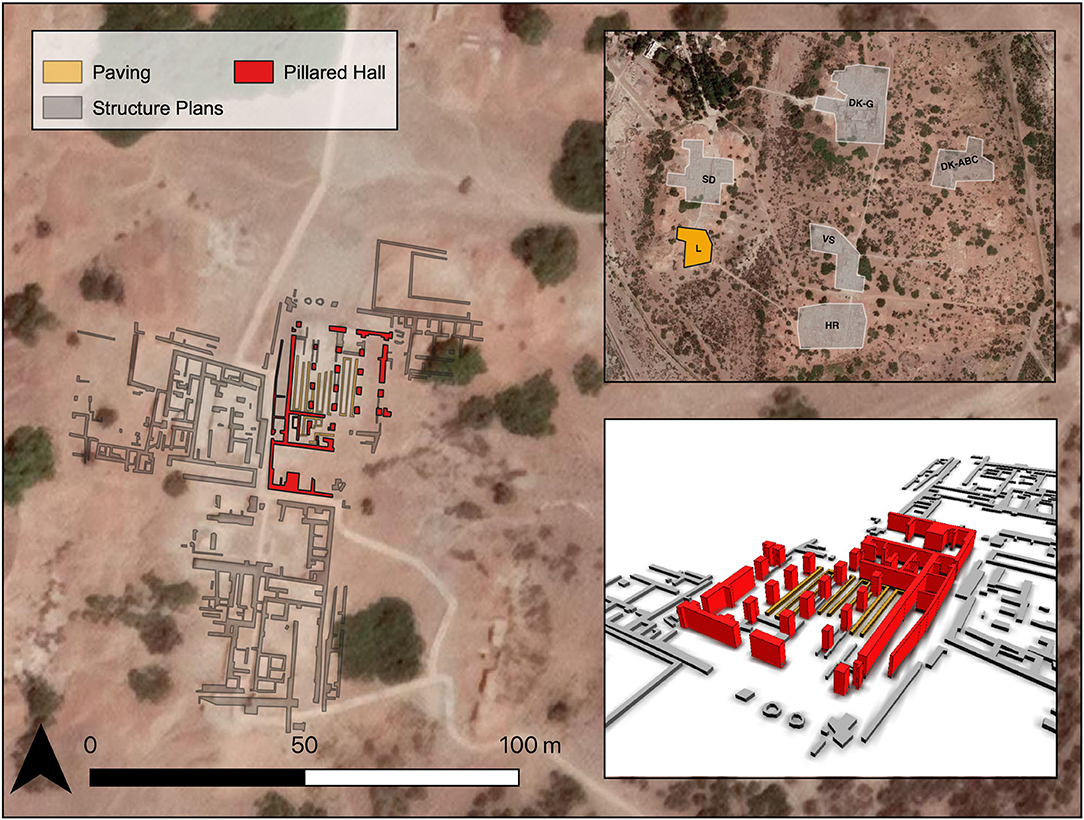

Mohenjo-daro's large non-residential structures were largely unwalled, widely accessible, and featured large open spaces. As a result, many scholars have argued that they served a range of “public” purposes (e.g., Jansen, 1993b; Possehl, 2002; Vidale, 2010; Wright, 2010; Smith, 2016). Their accessibility, enhanced by their numerous entrances and location on wide public streets, fits the criteria for public spaces defined by Hillier and Hanson (1984). Such spaces provided fertile ground for many people to engage in deliberation. The “Pillared Hall” at Mohenjo-daro (Figure 5) is one of the only structures that is regularly included in speculation about the Indus civilization's political process (e.g., Possehl, 2002), including by authors who suggest that Indus palaces have simply so far evaded the trowel (e.g., Kenoyer, 1998; Ratnagar, 2016). The structure was spacious, measuring more than 30 meters to a side, and boasted at least 20 brick pillars that could have supported a high ceiling (Mackay, 1931; Marshall, 1931, p. 159–161). It had paved brick walks and walls that were interspersed with gypsum, which would have brightened the space. Confounding early excavators, who compared the structure with courts from later Buddhist periods (Marshall, 1931, p. 24), it lacked benches, simply providing a large, enclosed space that could have accommodated hundreds of people. Indus cities are full of other clearings, yards, and similarly open spaces that could have provided places to deliberate. Such a clearing fills the northeast quadrant of Harappa (Meadow and Kenoyer, 2005), and Mohenjo-daro's mounds are separated by spaces that appear to have been deliberately left unoccupied (Wright, 2010). Dholavira has an extensive clearing enclosed within its walls (Bisht, 2015). Open spaces within urban settlements may also, of course, result from site formation processes. Unfortunately, such spaces rarely attract the attention from excavators that would be needed to narrow down our understanding of their use. Future geophysical investigations at Indus sites could help address this problem. For now, such features remain good candidates for deliberative spaces, even if we are unsure of the specific form that deliberation took.

Figure 5. Map and reconstruction of the “Pillared Hall” from Mohenjo-daro. Plans from Marshall (1931) and Mackay (1938) were digitized and extrapolated in three dimensions using QGIS 3.16 (www.qgis.org). Images is projected over Google Earth Satellite Imagery (accessed 2021).

Bureaucratization also impacts the way people use space. I argued above that it leads to the construction of “offices,” here defined as institutional spaces that facilitate administrative activities that crosscut and integrate social groups. Such institutional spaces are distinct from deliberative spaces in that they are dedicated to the implementation of governance and not necessarily the production of consensus. Interspersed among the houses of Mohenjo-daro were small structures that clearly were not houses. Two examples are the “hostel” and “letter-writers' office” that were reported in Mackay's (1938, p. 76, 92) excavation campaign at Mohenjo-daro. In a previous study, I argued that these were “small public structures,” constructed, further opened to the public streets in later construction phases, and expanded over the course of Mohenjo-daro's urban development (e.g., Green, 2018). These small public structures could have facilitated bureaucratic activities that could not be undertaken within houses. They were widely accessible and positioned adjacent to a major public intersection, indicating these activities were likely public in nature. Small public structures are undertheorized in archaeology, and there are understudied analogs in other archaeological contexts (e.g., Seibert, 2006). They could have played important role in implementing governance. Offices allow people to monitor, regulate, and shape activities at an institutional scale. This is why the small public structures of Mohenjo-daro had good access to the streets but were not constrained by a particular household or neighborhood (Green, 2018).

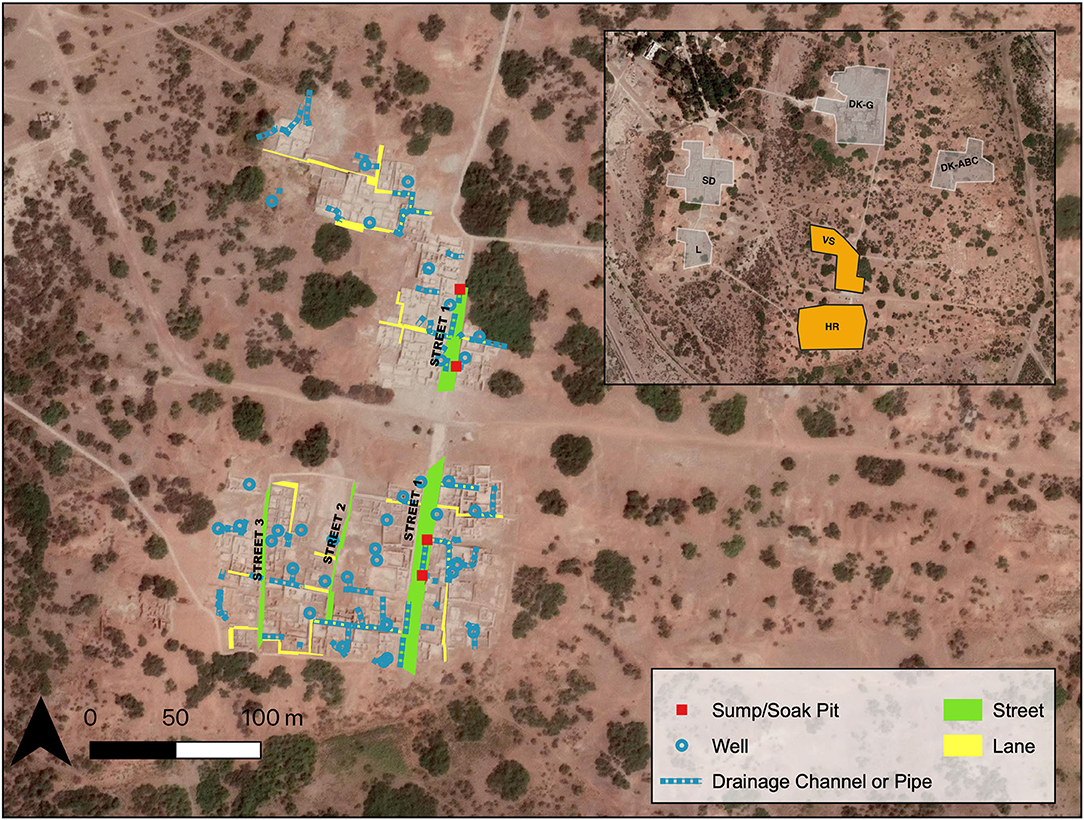

Infrastructures–road networks, city plans, walls, common storage facilities–materialize collective aims (e.g., Wilkinson, 2019) and thus provide convincing, if indirect, evidence of different forms of governance. Good examples of infrastructure are the terraces surrounding Monte Albán (Feinman and Nicholas, 2012), water transport systems among the Maya (Halperin et al., 2019) or Mesopotamian communities (Jotheri et al., 2019). So too was evidence of widespread faithfulness to street plans (Figure 6). Infrastructures are built up through many episodes of construction, each of which builds on and adapts to the standards applied in previous episodes, back to initial construction. Such sequences of construction coordinated the collective action of people separated by time and by space. Mohenjo-daro's neighborhoods, each atop a substantial brick platform, were arranged along wide streets that ran from north to south and were intersected by narrow lanes that ran from east to west (Marshall, 1931; Mackay, 1938; Jansen, 1978). It is striking that among the interconnected structures of Mohenjo-daro's neighborhoods, which changed dramatically through time (e.g., Mackay, 1938; Jansen, 1993a,b; Vidale, 2010; Green, 2018), the spatial integrity of many streets was nonetheless honored over the course of many episodes of building construction. Each episode of house construction re-established Mohenjo-daro's infrastructure. As Indus communities built and renovated their houses, they often remained careful not to impinge on streets, which presumably served the transportation needs of their settlements. In contrast, smaller lanes, which physically constrained access to houses, faced no such restriction, shifting in location from building episode to building episode. The episodic maintenance and modification of houses is important because Indus scholars generally agree that house construction was not carried out by civic authorities, but by the members of individual households, or by neighborhoods (Jansen, 1993b; Wright, 2010; Kenoyer, 2012). The same pattern structured Mohenjo-daro's drainage system, which included wells, pipes, gutters, and “soaks” that drained water from private bathing platforms within individual households (e.g., Jansen, 1993a; Rizvi, 2011; Wright and Garrett, 2017). As with lanes, households likely constructed pipes that connected their bathing platform to the city's drains, which were located at regular spatial intervals in the wide public streets. Open streets and drainage both comprised public goods (Figure 6), and elements of both kinds of infrastructure have also been revealed at numerous smaller Indus settlements, such as Kalibangan (Lal et al., 2015) and Farmana (Shinde et al., 2011).

Figure 6. Map of Street and Drainage Plans from HR and VS Area at Mohenjo-daro. Plans from Marshall (1931) and Mackay (1938) were digitized and extrapolated in three dimensions using QGIS 3.16 (www.qgis.org). Images is projected over Google Earth Satellite Imagery (accessed 2021).

The interactions between Indus neighborhoods that would have facilitated these developments have often been labeled heterarchical. Indeed, the interactions between guild-like organizations, households, neighborhoods, and different Indus sites would likely have been unranked. With regard to urban growth, the thinking goes that different heterarchical social groups–neighborhoods, corporate groups, households–managed their affairs independently of one another (Possehl, 2002; Kenoyer and Miller, 2007; Vidale, 2010; Wright, 2010). Vidale (2018) offered an expanded version of this model, positing that Indus heterarchy was analogous to competition between groups of elites evident in Medieval Genoa. However, accepting this interpretation requires us to make the unfounded assumption that Indus cities were stratified, forcing Indus evidence into an outdated neo-evolutionary model, and obscuring the persistence of egalitarianism in the past (e.g., Green, 2021). Better to suppose that neighborhood and household groups likely exerted polycentric forms of authority on the urban environment (e.g., Petrie, 2013b) than make unwarranted assumptions. Moreover, it is also unlikely that heterarchical interactions between different institutions can fully explain the growth of Indus cities. Indus governance clearly incorporated institutional spaces capable of mobilizing large quantities of revenue and managing its use, mobilizing labor at large scales. However, there is no evidence that the specialists who occupied such offices belonged to a different class than the households from which they coordinated labor.

Most debate surrounding the Indus civilization's political organization has focused on whether or not the Indus civilization was a “state”, and if it was, what kind (e.g., Fairservis, 1961, 1989; Wheeler, 1968; Possehl, 1982, 1998, 2002; Ratnagar, 1991, 2016; Kenoyer, 1994, 1997b; Lal, 1997; Dhavalikar, 2002; Agrawal, 2007; Wright, 2010, 2016; Petrie, 2013a, 2019; Chakrabarti, 2014; Sinopoli, 2015; Shinde, 2016). Scholars have variously described Indus political forms as city-states, domains, and some even suspect that it was an empire. Many of these interpretations hinge on the degree of elite agency a particular archaeologist is willing to infer from the archaeological evidence. Noting that the Indus lacked palaces, exclusionary temples, tombs, and aggrandizing monuments that archaeologists can use to infer the presence of a ruling class, I have argued elsewhere that we need to explain political and economic transformations in the Indus without invoking elite agency (Green, 2021). This position leads to the question: How do egalitarian urban societies govern themselves?

It is surprisingly straightforward to outline an answer. Egalitarian governance is likely to have incorporated many of the same institutional characteristics neo-evolutionary theorists would have confined to despotic states. Egalitarian governance mobilizes collective action that produces public goods, such as economic legibility, civic organization, or environmental management–all things that are broadly usable to most if not all of the people in a society. Examples of collective action in the Indus attest to the construction of buildings that served common goals that crosscut many social groups–public buildings or infrastructure that benefited everyone–not an exclusionary ruling class. Beyond collective action, Indus governance coordinated the activities of everyday households and was oriented toward producing public benefits. Street plans, drainage systems, and standards of recording and measurement all attest to the use of revenues to create goods in response to collective needs. Evidence from the Indus civilization therefore indicates that the governance of its cities was good, especially during the phase(s) that have left the most pronounced material footprints.

Potential revenues for funding public goods likely increased with the economic specialization and intensification that is well-attested in archaeological evidence from Indus cities (Wright, 2010). These economic resources were widely distributed throughout Indus society using weights and seals, not dissimilar to the patterns of craft production and use evident at Monte Albán (Nicholas and Feinman, 2022). Indus seals and sealings comprised a coherent and distributed system of monitoring information–one that was governed, but also emergent, and likely played a key role in making economic transactions legible across social boundaries, another public good. Indus seals would have facilitated the collection of revenues, which, by extension, may have existed in a state of social dispersal until needed for collective action, and episodes of revenue collection may have been task-oriented and ephemeral. However, the widespread availability of the means of specification, and thus access to information, prevented the monopolization of revenues and predatory extraction of value from one corporate group by another (e.g., Green, 2020). The political decision-making process necessary to set objectives for revenue expenditure likely occurred, at least in part, in deliberative spaces, which provided one potential mechanism for resolving conflicts, setting agendas, and making plans, through mass participation. This is not to say that every occupant of each Indus city weighed in on every collective decision, but such structures could have allowed a great many voices to be included in the discussion. Nor were deliberative spaces the only avenue to collective decision-making. Guild-like organizations and technological standardization almost certainly came about through many instances of interaction among craftspeople. The deliberative process no doubt benefited from the distribution of information within Indus society–seals and sealings effectively democratized revenue data.

Offices provided the capacity to implement political decisions. The small public structures of Mohenjo-daro's eastern mounds are a prime example of institutional spaces for the implementation of governance (Green, 2018), but platforms like those recorded at Lothal, Harappa, and even smaller sites like Vainiwal could have served a similar purpose. These institutional spaces were not under the control of a single household or neighborhood, and the people who mobilized labor through them may have been temporary appointees from different households in place to carry out tasks. The sophistication of the projects they appear to have coordinated suggests they amassed considerable skill and knowledge while eschewing material benefits that exceeded those available to other people in the city. Here, too, a democratized means of specification likely played a key role. The wide availability of information could have served as a check on any effort to direct revenue toward projects that permanently increase the political or economic status of a subset of people. It is much easier to achieve the equitable taxation of internal resources if everyday people are in full possession of information about their contribution to collective endeavors. Offices likely helped develop the protocols required to produce and reproduce the physical matrix of Indus life, such as the brickmaking standards that were necessary to build the structures we recognize as Indus. This relationship between deliberative and institutional space outlines a potential comparative lesson for archaeology. Both deliberative and institutional spaces were (and are) essential to good governance, though the features of both will vary depending on the specific institutions involved. The ratio of offices to deliberative spaces may provide insights into how good a government was in the past. When deliberative spaces are as prevalent as institutional spaces, we can infer that governance was more responsive to everyday communities. Collective action, revenue, and deliberative and institutional spaces are therefore interlinked within systems of governance. Each of these elements of governance is attested to directly or indirectly by archaeological evidence.

The theory of egalitarian governance I have outlined here reinforces the idea that governance is fairest and most sustainable when it emerges from within the groups being governed. Ostrom (1990, 2009, 2010) has long held that the people who govern best are those closest to the resource being governed. The people who use a common resource must trust one another, set the rules for its governance, and monitor one another to ensure those rules are followed. What if the “commons” being governed is public revenue itself? Given that revenue emerges from all the constituents within a political system, does it not follow that collective action is best achieved through the widespread participation in governance? While Ostrom's model has long problematized the idea that “rulers” are the ones best positioned to govern revenue, the Indus extends collective action theory because it provides a concrete example of revenue without rulers, contradicting the myth that revenue only exists when it is captured by rulers.

Why is the potential that an early urban society governed itself without a ruling class so challenging to political theory? After all, democratic deliberation, inclusive political processes, and checks on the concentration of political authority are ideals to which many governments today aspire. Task rotations, elections, and term limits are used now to serve to limit the concentration of political and economic power within a specific social stratum. Rulers are non-essential to many of the supposed outputs of good governance, and “non-elites” or everyday people often spearhead political actions in later societies (Thurston, this special topic). Fiscal systems, which require revenue, are evident in politically decentralized as well as centralized societies (Tan, this special topic). Perhaps it is because many contemporary (and especially Western) narratives of political change are implicitly self-congratulatory and want to see them reinforced in the origin stories of today's nation-state (Blanton et al., 2020). It was by no means pre-ordained that a ruling class would come to monopolize political decision making. Indeed, the opposite would more likely be the case. After all reciprocity is a human universal (Mauss, 1925; Sahlins, 1972; Bowles and Gintis, 2013), so it is unsurprising that the archaeological record records a concern for fairness through deep time (Jennings, 2021).

In this article, I have argued against the assumption that public goods can only be gained by surrendering political agency to a ruling class. Addressing this issue is essential if we want to increase our understanding of good governance, which coordinates collective action for the benefit of everyday people (Blanton et al., 2021). The archaeology of the Indus civilization supports this strong association between collective action and good governance, and between good governance and egalitarianism. In the Indus, there is evidence that many different social groups coordinated their activities from the bottom-up and top down. Indus communities adhered to common standards in craft production and construction, which likely emerged through interactions between different households, neighborhoods, and guild-like organizations. Access to information, such as that which could be materialized using seals and sealings, was democratized, allowing substantial revenues to exist in a state of dispersal ensuring that political decision-making took many voices into account. However, Indus governance also incorporated institutions that facilitated mass deliberation and implementation, such as structures and spaces that could have facilitated deliberation and the implementation of collective aims. Bureaucratic institutions, such as civic authorities, that likely organized collective action at large scales to produce certain public goods, like large non-residential buildings, foundation platforms, and street plans, that were necessary for Indus cities to grow and thrive. In conclusion, I reiterate the argument, also advanced by the other authors of this special topic, that good governance is not limited to modern societies. The archaeology of the Indus civilization encourages us to further question the agency of rulers to the creation of public goods and consider the implications of the apparent linkage between good governance and egalitarian social organization.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: www.archive.organdlt.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

I would like to thank Richard Blanton, Gary Feinman, Stephan Kowalewksi, and Lane Fargher for the invitation to participate in this special topic, as well as the other contributors for their insights into governance in a wide variety of past contexts. The resulting special topic has been an ideal space for comparing patterns from the past that have strong implications for how we organize our own societies. I would also like to thank the four reviewers who helped me improve this paper. Cameron Petrie, Darryl Wilkinson, and Toby Wilkinson provided helpful comments on an early draft, and my ongoing conversations with Rekha Bhangaonkar, Shailaja Fennell, Tom Leppard, and Nancy Highcock helped me to shape the ideas presented here. I am also grateful for conversations with Uzma Rizvi and the Laboratory for Integrated Archaeological Visualization and Heritage research group for conversations about reconstructing and visualizing structures identified in the early reports at Mohenjo-daro. I would like to acknowledge Rita Wright and Sneh Patel, with whom I have been discussing elements of this argument for a decade. This article incorporates ideas I developed while working on the TwoRains project, which was funded by the European Research Council under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, grant agreement no. 648609 and the Global Challenges Research Fund's TIGR2ESS (Transforming India's Green Revolution by Research and Empowerment for Sustainable food Supplies) Project, Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council grant number BB/P027970/1. I wrote this article as an Affiliated Lecturer in the Department of Archaeology and as a Research Associate at King's College, University of Cambridge. This research was made possible thanks to the ongoing support of Lillian, Henry, and Isaac Green. Any faults in the article's text or argument are entirely my own.

Acemoglu, D., and Robinson, J. A. (2013). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. London: Profile Books. doi: 10.1355/ae29-2j

Agrawal, D. P. (2007). The Indus Civilization: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.

Agrawal, D. P. (2009). Harappan Technology and Its Legacy1. New Delhi: Rupa and Co. in association with Infinity Foundation.

Akkermans, P. M. M. G., and Duistermaat, K. (1996). Of storage and nomads. The sealings from Late Neolithic, Sabi Abyad, Syria. Paléorient 22, 17–44. doi: 10.3406/paleo.1996.4635

Ameri, M. (2013). Regional diversity in the Harappan World: the evidence of the seals, in Connections and Complexity, eds Abraham, S. A., Gullapalli, P., Raczek, T. P., and Rizvi, U. Z., (Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press).

Ameri, M., Costello, S. K., Jamison, G., and Scott, S. J. (2018). Seals and Sealing in the Ancient World: Case Studies From the Near East, Egypt, the Aegean, South Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108160186

Bates, J., Singh, R. N., and Petrie, C. A. (2017). Exploring Indus crop processing: combining phytolith and macrobotanical analyses to consider the organisation of agriculture in northwest India c. 3200–1500 bc. Veg. History Archaeobotany 26, 25–41. doi: 10.1007/s00334-016-0576-9

Bettencourt, L. M. A., Lobo, J., Helbing, D., Kuhnert, C., and West, G. B. (2007). Growth, innovation, scaling, and the pace of life in cities. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 104, 7301–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610172104

Bhan, K. K., Sonawane, V. H., Ajithprasad, P., and Pratapchandran, S. (2004). Excavations of an important Harappan trading and craft production center at Gola Dhoro (Bagasra), on the Gulf of Kutch, Gujarat, India. J. Interdisciplinary Stud. History Archaeol. 1, 153–58.

Birch, J. (2014). From Prehistoric Villages to Cities: Settlement Aggregation and Community Transformation, 1st edition.: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203458266

Bisht, R. S. (1987). Further Excavations at Banawali: 1983-1984, in Archaeology and History : Essays in Memory of Shri A. Ghosh, eds Pande, B., Chattopadhyaya, B., and Ghosh, A., (Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan) 135–56.

Bisht, R. S. (2005). The Water Structures and Engineering of the Harappans at Dholavira (India), in South Asian Archaeology 2001: Proceedings of the Sixteenth International Conference of the European Association of South Asian Archaeologists, eds Jarrige, C., and Lefèvre, V., (Paris: Éditions Recherche sur les Civilisations).

Blanton, R. E. (1998). Beyond centralization: Steps toward a theory of egalitarian behavior in archaic states, in Archaic States >eds Feinman, G. M., and Marcus, J., (Santa Fe: School of American Research Press).

Blanton, R. E. (2010). Collective action and adaptive socioecological cycles in premodern states. Cross-Cultural Res. 44, 41–59. doi: 10.1177/1069397109351684

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2008). Collective Action in the Formation of Pre-Modern States. New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73877-2

Blanton, R. E., Fargher, L. F., Feinman, G. M., and Kowalewski, S. A. (2021). The fiscal economy of good government: past and present. Curr. Anthropol. 62:3286. doi: 10.1086/713286

Blanton, R. E., Feinman, G. M., Kowalewski, S. A., and Fargher, L. F. (2020). Moral collapse and state failure: a view from the past. Front. Political Sci. 2, 568704. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.568704

Blanton, R. E., Feinman, G. M., Kowalewski, S. A., and Peregrine, P. N. (1996). A Dual-processual theory for the evolution of mesoamerican civilization. Curr. Anthropol. 37, 1–14. doi: 10.1086/204471

Bogaard, A., Charles, M., Twiss, K. C., Fairbairn, A., Yalman, N., Filipovi,ć, D, Demirergi, G. A., Ertu,g, F, Russell, N, and Henecke, J. (2009). Private pantries and celebrated surplus: storing and sharing food at Neolithic Çatalhöyük, Central Anatolia. Antiquity 83, 649–668. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00098896

Bondarenko, D. M., Kowalewski, S. A., and Small, D. B. (2020). The Evolution of Social Institutions: Interdisciplinary Perspectives (World-Systems Evolution and Global Futures). Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-51437-2

Bowles, S., and Gintis, H. (2013). A Cooperative Species: Human Reciprocity and Its Evolution1. Paperback print (Economics, anthropology, biology). Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press.

Carballo, D. M. (2013). Cooperation and Collective Action (Archaeological Perspectives). Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

Chakrabarti, D. K. (2014). Distribution and features of the harappan settlements, in History of India: Protohistoric Foundation, eds Chakrabarti, D. K., and Lal, M., (New Delhi: Vivekanand International Foundation).

Chase, B. (2010). Social change at the Harappan settlement of Gola Dhoro: a reading from animal bones, Antiquity 84, 528–543. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00066758

Chase, B., Ajithprasad, P., Rajesh, S. V., Patel, A., and Sharma, B. (2014). Materializing Harappan identities: Unity and diversity in the borderlands of the Indus civilization. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 35, 63–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2014.04.005

Childe, V. G. (1950). The urban revolution. Town Plan. Rev. 21, 3–17. doi: 10.3828/tpr.21.1.k853061t614q42qh

Cork, E. (2011). Rethinking the Indus: A Comparative Re-Evaluation of the Indus Civilisation as an Alternative Paradigm in the Organisation and Structure of Early Complex Societies (BAR international series 2213). Oxford: Archaeopress. doi: 10.30861/9781407307718

Cowgill, G. L. (2004). Origins and development of urbanism: archaeological perspectives. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 33, 525–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.32.061002.093248

Cowgill, G. L. (2015). Ancient Teotihuacan: Early Urbanism in Central Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139046817

Crumley, C. L. (1995). Heterarchy and the analysis of complex societies. Archeol. Papers Am. Anthropol. Assoc. 6, 1–5. doi: 10.1525/ap3a.1995.6.1.1

Dangi, V. (2018). Indus (Harappan) civilization in the Ghaggar Basin, in Current Research on Indus Archaeology, ed A. Uesugi (South Asian Archaeology 4).: Research Group for South Asian Archaeology, Archaeological Research Institute, Kansai University.

DeMarrais, E. (2016). Making pacts and cooperative acts: the archaeology of coalition and consensus. World Archaeol. 48, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/00438243.2016.1140591

DeMarrais, E., and Earle, T. (2017). Collective action theory and the dynamics of complex societies. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 46, 183–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-102116-041409

Dhavalikar, M. K. (2002). “Harappan Social Organization.” In Protohistory: Archaeology of the Harappan Civilization, edited by S Settar and Ravi Korisettar, 2: 173–94. New Delhi: Manohar.

Duistermaat, K. (2012). Which came first, the bureaucrat or the seal? Some Thoughts on the Non-Administrative Origins of Seals in Neolithic Syria, in Seals and Sealing Practices in the Near East: Developments in Administration and Magic From Prehistory to the Islamic Period, eds. Regulski, I., Duistermaat, K., and Verkinderen, P., (Paris: Leuven).

Eerkens, J., and Bettinger, R. L. (2001). Techniques for assessing standardization in artifact assemblages: Can we scale material variability? Am. Antiquity 66, 493–504. doi: 10.2307/2694247

Fairservis, W. A. (1961). The harappan civilization new evidence and more theory. Am. Museum Novitates 2055:36.

Fairservis, W. A. (1982). Allahdino: An excavation of a small harappan site, in Harappan Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective, ed Possehl, G. L., (Warminster).

Fairservis, W. A. (1989). An epigenetic view of the Harappan culture, in Archaeological Thought in America, ed Lamberg-Karlovsky, C. C., (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511558221.014

Feinman, G. M. (2011). Size, complexity, and organizational variation: a comparative approach. Cross-Cultural Res. 45, 37–58. doi: 10.1177/1069397110383658

Feinman, G. M. (2013). The emergence of social complexity, in Cooperation and Collective Action, ed Carballo, D. M., (Boulder: University Press of Colorado).

Feinman, G. M. (2018). The governance and leadership of prehispanic mesoamerican polities: new perspectives and comparative implications. Cliodynamics 9:40. doi: 10.21237/C7CLIO9239449

Feinman, G. M., and Carballo, D. M. (2018). Collaborative and competitive strategies in the variability and resiliency of large-scale societies in Mesoamerica. Econ. Anthropol. 5, 7–19. doi: 10.1002/sea2.12098

Feinman, G. M., and Carballo, D. M. (2022). Communication, computation, and governance: a multiscalar vantage on the prehispanic mesoamerican world. J. Soc. Comp. 3, 91–118. doi: 10.23919/JSC.2021.0015

Feinman, G. M., and Nicholas, L. M. (2012). The late prehispanic economy of the valley of oaxaca, mexico: weaving threads from data, theory, subsequent history, in Research in Economic Anthropology, eds. Matejowsky, T., and Wood, D. C., (Emerald Group Publishing Limited). doi: 10.1108/S0190-1281(2012)0000032013

Fentress, M. (1976). Resource Access, Exchange Systems, and Regional Interaction in the Indus Valley: An Investigation of Archaeological Variability at Harappa and Mohenjodaro, PhD, University of Pennsylvania.

Ferioli, P., and Fiandra, E. (1983). Clay Sealings from Arslantepe, in Origini: Preistoria e Protostoria Delle Civiltà Antiche [Perspectives on Protourbanization, in Eastern Anatolia: Arslantepe (Malatya) An Interim Report on 1975-1983 Campaigns, ed Ferioli, P., (Rome: Università delgi Studi di Roma).

Flannery, K. V. (1972). The cultural evolution of civilizations. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1972, 399–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.03.110172.002151

Fletcher, R. (1995). The Limits of Settlement Growth: A Theoretical Outline (New studies in archaeology). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Frangipane, M. (2007). The Development of an Early State System without Urbanisation, in, ed. M. Frangipane. Roma: Università di Roma. Dipartimento di Scienze Storiche Archeologiche e Anthropologiche dell'Antichità, 2007, 469–77.

Frenez, D. (2018). Private person or public persona? Use and significance of standard indus seals as markers of formal socio-economic identities, in Walking with the Unicorn: Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia, eds Frenez, D., Jamison, G. M., Law, R., Vidale, M., and Meadow, R. H., (Oxford: Archaeopress). doi: 10.2307/j.ctv19vbgkc

Frenez, D., and Tosi, M. (2005). The lothal sealings: records from an indus civilization town at the Eastern End of the maritime trade circuits across the Arabian Sea, in Studi in Onore Di Enrica Fiandra: Contributi Di Archaeologia Egea e Vicinorientale, ed Perna, M., (De Boccard).

Frenez, D., and Vidale, M. (2012). Harappan Chimaeras as ‘Symbolic Hypertexts'. Some thoughts on plato. Chimaera Indus Civilization South Asian Stud. 28, 107–130. doi: 10.1080/02666030.2012.725578

Green, A. S. (2015). Stamp Seals in the Political Economy of South Asia's Earliest Cities. New York, NY: New York University.

Green, A. S. (2016). Finding Harappan seal carvers: An operational sequence approach to identifying people in the past. J. Archaeol. Sci. 72, 128–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2016.06.008

Green, A. S. (2018). Mohenjo-Daro's Small Public Structures: Heterarchy, Collective Action and a Re-visitation of Old Interpretations with GIS and 3D Modelling. Cambridge Archaeol. J. 28, 205–223. doi: 10.1017/S0959774317000774

Green, A. S. (2020). Debt and inequality: Comparing the “means of specification” in the early cities of Mesopotamia and the Indus civilization. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 60:101232. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2020.101232

Green, A. S. (2021). Killing the priest-king: Addressing egalitarianism in the Indus civilization. J. Archaeol. Res. 29, 153–202. doi: 10.1007/s10814-020-09147-9