95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 23 February 2022

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.798128

Citizens' everyday political talk is the foundation and mainspring of deliberative democracy. Accordingly, citizens' equal and inclusive participation in political discussions is deemed crucial for this “talk-centric” vision of normatively superior democratic will-formation. Yet, discussing politics is a quite demanding activity, and research has shown that de facto not everyone has equal access to this arena of political communication. Some citizens talk about public affairs almost constantly, others more sparingly, and yet others not at all. These inequalities reflect imbalances in structural and psychological resources. Little is known, however, about what happens once individuals have entered conversations about public affairs. The article breaks new ground by examining communicative asymmetries that ordinary people experience when talking about politics with members of their overall and core networks. By muting their voices they disadvantage certain citizens, thus impairing the discursive equality that is essential for deliberative democracy. Drawing on a unique high-quality survey conducted in Germany, the article finds such experiences to take different forms of which some are quite widespread. Many citizens resort to passive listening and contribute little to unfolding conversations. Smaller shares misrepresent their true standpoints, change subjects to avoid problematic topics, drop out of unpleasant conversations, or feel silenced by other interlocutors. The article contextualizes these communicative asymmetries in the broader theoretical framework of deliberative democrats' conception of discursive inequality. To examine how they come about it proposes and tests a model of internal exclusion that refers to social structural inequality, psychological dispositions, and attributes of the discussant networks within which political conversations take place. Social structural inequality is found to be of limited relevance. Individuals' communicative efficacy and orientations toward political conflict are more important predictors of their ability to cope with the challenges of political talk than aspects of general politicization like political interest, attitude strength and internal efficacy. Encountering political disagreement is normatively central for deliberative democracy, but empirically it stands out as a powerful social driver of asymmetric communication. Its impact is strongly conditioned by individuals' structural attributes and psychological dispositions.

“Talk-centric” deliberative democracy (Chambers, 2003, p. 308) is the currently most intensely discussed alternative to election-centered liberal democracy. It is advocated as a normatively superior way of dealing with societal disagreements over political goals. Conceptions of what deliberative democracy is about vary to some extent, but inclusiveness and equality belong to its undisputed core (Bächtiger et al., 2018a, p. 5–6; Bächtiger and Parkinson, 2019, p. 5–11). As such, this emphasis does not set deliberative democracy apart from other models of democratic governance (Dahl, 2006).

However, in its emphasis on political discussion deliberative democracy prioritizes a type of political activity that is quite demanding, especially when compared to electoral participation, the mode of citizen engagement constitutive for liberal democracy. This implies that in citizens' actual practice deliberative democracy might be even more prone than liberal democracy to infringements of the principle of equality. Advocates of deliberative democracy have sometimes gone so far as to portray it as a renaissance of classical Athenian democracy and its rhetorical conception of equal citizenship (Fishkin, 2018, p. 51–56; Cammack, 2021). But at least one critic (Hooghe, 1999) has gone back even further, citing Homer's Iliad (and its anecdote about Odysseus rebuking Thersites for daring to speak up as a common man in the face of the Achaeans' great heroes) to illustrate its vulnerability to “discursive inequality” (Bohman, 1996, p. 107–149; Beauvais, 2018), a particularly treacherous translation of social inequality into political inequality. The tension between deliberative democracy's high-flying aspirations and the traps that might be hidden in the depths of its practice is obvious.

The politics of deliberative democracy is supposed to emanate from an ongoing, broad and encompassing discussion of citizens with one another (Barber, 1984; Habermas, 1996; Mansbridge, 1999; Chambers, 2012; Neblo, 2015, p. 17–25; Tanasoca, 2020; Schmitt-Beck, forthcoming). Accordingly, the prospects of this vision of democratic will-formation would be seriously impaired if people's everyday communication would fall short of the criteria of inclusiveness and equality. By examining whether and how frequently citizens engage in political talk in their lifeworld (Schmitt-Beck and Lup, 2013; Conover and Miller, 2018) extant research has provided evidence on the extent to which these criteria are realized with regard to people's “access” to political discussions (Knight and Johnson, 1997, p. 280–282). However, for the functioning of deliberative democracy it is just as important what happens once individuals have gained access and entered a conversation about public affairs. At issue is then how the participants of political discussions interact with one another, and this is the topic of the present article.

Ideally, when discussing public affairs citizens should communicate on an equal footing. Their talk should be reciprocal and dialogic (Gutmann and Thompson, 1996, p. 52–94). Yet, during political conversations more or less subtle dynamics of “internal exclusion” (Young, 2000, p. 55; Beauvais, 2021) may create communicative “asymmetries” between participants (Thornbury and Slade, 2006, p. 17–20; Beauvais, 2018, p. 147), so that not everyone can contribute on par with everyone else. For instance, certain people may hold back and adopt the passive role of listeners, whereas others do the talking (Neuwirth et al., 2007). Certain interlocutors might also misrepresent their true standpoints (Kuran, 1998; Carlson and Settle, 2016) whereas others state their views without restraint. Some participants may change subjects to avoid problematic topics whereas others carry on. Or they may even drop out of conversations when they become uncomfortable, thus ceding the floor to those that stay in. In addition, during conversations it can also occur that certain people feel silenced by others (Lupia and Norton, 2017).

Clearly, such communicative asymmetries advantage certain people, and disadvantage others. As a consequence, the former's perspectives dominate discussions, whereas those of the latter are muted or disappear completely from the conversation. Their views remain unexpressed and the arguments they could contribute are withheld from the conversation which therefore only incompletely mirrors the range of views potentially relevant for the subject matters under discursive scrutiny. Although present in interlocutors' minds, they fail to achieve adequate “discursive representation” (Dryzek and Niemeyer, 2008). This, in turn, undermines their potential to influence the course of the discussion, and ultimately its outcomes. Thus, although having gained access, persons disadvantaged by asymmetric communication cannot participate effectively in the specific mode of political activity prioritized by deliberative democracy. Consequently, they fail to influence its processes of opinion- and will-formation (Knight and Johnson, 1997, p. 280–282).

Communicative asymmetries during political discussions have been explored for arenas like deliberative mini-publics and online platforms as well as in laboratory experiments. But little is known about such phenomena in the everyday political conversations that unfold in citizens' lifeworld in a spontaneous and informal manner. To get a better understanding of the role of everyday political talk in deliberative democracy the article accordingly examines citizens' experiences of asymmetric communication during informal conversations about politics. To comprehend how such imbalances between the participants of everyday political talk come about it proposes and tests a model of internal exclusion that takes into account the role of social structural inequality and psychological dispositions, as well as features of the social networks within which such conversations take place. It turns out that political disagreement between interlocutors, an essential prerequisite of deliberative democracy (Thompson, 2008, p. 502), figures most prominently among these social factors (Nir, 2017). The analyses show that it plays a crucial role in the emergence of asymmetric communication. However, to a remarkable extent its impact is conditional. Whether interlocutors are endowed with certain motivations and skills weakens or strengthens the detrimental effect of political dissent on the conduct of political talks.

The article starts with a reflection on the ambiguous status of discursive equality within deliberative democracy as something deemed normatively essential but challenging to achieve in its practice. To clarify and contextualize the article's research question the following section offers an analytical reconstruction of deliberative democrats' theoretical reasoning about discursive inequality. From there the article zooms in on communicative asymmetries in political discussions and how they come about. The analyses are guided by hypotheses derived from a model of internal exclusion in citizens' everyday political talk. They are tested for a range of empirical manifestations of asymmetry. The analyses draw on the Conversations of Democracy study, a unique face-to-face survey specially designed to examine German citizens' everyday political talk. To achieve a comprehensive understanding the analyses pertain to both overall networks and core networks (Eveland et al., 2012).

Political equality is quintessential for democracy. Abstracting from social and personal inequalities by granting all citizens the same say in the process of generating binding decisions has always been its central principle (Dahl, 1989, p. 119–131; 2006). To prevent a systematic exclusion of certain perspectives from the policy process all individuals and groups must be able to participate effectively. However, after decades of research there can be no doubt that equal and inclusive rights to participate are a necessary, but not a sufficient condition of actual engagement. Numerous studies have shown that citizens' readiness to use the opportunities offered by the constitutional order varies strongly. Certain people participate more intensely than others, and some even keep out of politics entirely (Schlozman et al., 2012; Dalton, 2017).

Issues of equality are challenging for liberal democracy (Lijphart, 1997). But they raise even more thorny problems for deliberative democracy because it expects much more input from its citizens. Whereas casting votes at elections is the institutional core of liberal democracy, deliberative democracy places special emphasis on political talk. Liberal democracy is essentially about aggregating pre-existent preferences by counting votes, but deliberative democracy is concerned with developing, validating and refining such preferences through the enlightening process of political discussion (Young, 2000, p. 18–26; Gutmann and Thompson, 2004, p. 13–21). To that end, it requires “widespread and ongoing participation in talk by the entire citizenry” (Barber, 1984, p. 197).

Deliberative democracy entails a rhetorical notion of citizenship (Kock and Villadsen, 2017) at whose heart is the normative conception of non-elite members of the polity as free and equal contributors to an inclusive and encompassing process of multi-layered, interconnected discussions about public affairs that permeate society in its entirety and feed into the institutional arenas of political will-formation and decision-making (Habermas, 1996; Parkinson and Mansbridge, 2012; Bächtiger et al., 2018b). Ideally, the politics of deliberative democracy emerges from an ongoing, broad and encompassing conversation within the citizenry at large (Tanasoca, 2020; Schmitt-Beck, forthcoming). To live up to this aspiration the political talk that takes place in citizens' lifeworld ought to be inclusive and egalitarian. For deliberative democrats, this entails “the emancipatory promise of an equal voice in a process of free reasoning” for all citizens, regardless of their social backgrounds (Knops, 2006, p. 596). It is also seen as a necessary condition for realizing the epistemic potential of democratic deliberation, since chances to identify the best policies are compromised if only a truncated selection of viewpoints is available for deliberative scrutiny (Mill, 2015, p. 18–54; Fishkin, 1991, p. 35–41; Bohman, 2006). Ultimately, addressing societal disagreements about the means and ends of politics through deliberative processes that exclude no one and encompass all societal groups is seen as a superior source of democratic legitimacy (Manin, 1987; Cohen, 1989).

According to deliberative democrats, these promises presuppose that all citizens' voices are raised and listened to in equal measure during conversations about public affairs that occur informally and spontaneously at kitchen tables, in pubs, commuter trains, companies' breakfast rooms, or over the proverbial garden fence (Mansbridge, 1999; Chambers, 2012)1. Yet, these conditions are precarious. Discussing politics is a challenging activity which places considerably greater demands on individual citizens than voting. Unlike choosing in the solitude of a voting booth, political talk is an inherently relational activity that requires to interact more or less intensely with other people. It inevitably entails a social component alongside the political themes and issues that constitute its substance (Watzlawick et al., 2011, p. 29–52). During processes of political talk the former might even take precedence over the latter, and this appears particularly likely under the very circumstances that deliberative democracy aims to address (Thompson, 2008, p. 502): when differences of opinion arise over potentially conflictive subjects (Conover et al., 2002; Mutz, 2006). Some scholars have accordingly emphasized that discussing politics with one's peers can be a quite stressful and adverse experience that many people may find uncomfortable and prefer to avoid (Rosenberg, 1954; Scheuch, 1965; Schudson, 1997; Eliasoph, 1998). As Young noted, some people may find political talk enjoyable, but in many others it raises anxiety (Young, 2000, p. 16).

Certain people may therefore be impeded or even completely unable to participate effectively in the specific mode of political activity prioritized by deliberative democracy. Consequently, despite, or perhaps rather because of its high aspirations, deliberative democracy might be even more vulnerable to political marginalization of disadvantaged groups and individuals than liberal democracy (Sanders, 1997; Hooghe, 1999). It might fall victim to “discursive inequality”: deliberative democracy's unique variant of political inequality (Bohman, 1996, p. 107–149; Graham and Wright, 2014; Beauvais, 2018).

To contextualize the research question addressed by this article, Figure 1 identifies and systematizes the essential building blocks of deliberative democrats' conception of discursive inequality. Essentially this conception applies to all manifestations of political talk among citizens, including formalized discussions in institutional arenas, such as town-hall meetings or deliberative mini-publics (Grönlund et al., 2014). But the following discussion concentrates on its implications for citizens' casual and spontaneous everyday communication about politics.

Like other forms of political communication, citizens informal conversations presuppose a legal context that effectively guarantees the freedoms of opinion and expression. But what ultimately counts is how citizens actually use these rights. Do they take part in discussions about political matters, and if so, how? From the deliberative democratic point of view, the imperative of equality entails that all citizens should engage in political discussions, and that they should do so on the same terms. As pointed out by Knight and Johnson, this necessitates to overcome the threshold of access which is about whether citizens engage in political discussions at all, as well as the subsequent threshold of influence on their outcomes (Knight and Johnson, 1997, p. 280–282). The latter concerns the “discursive dynamics” (Jennstål, 2018, p. 450) that unfold between participants during these discussions' social process (Gastil, 2008, p. 9–10). Abstention from political talk indicates unequal access to political discussions. However, for the functioning of deliberative democracy it is no less important what happens once persons have accessed a conversation. At issue is then how its participants interact with one another. Among those that take part, symmetrical communicative engagement is desirable. Discussions should be reciprocal and dialogic; interlocutors are expected to take turns in contributing, alternately speaking up and listening to what the others have to say, carefully considering what they heard, and faithfully responding to it (Gutmann and Thompson, 1996, p. 52–94). Habermas' conception of an “ideal speech situation” is perhaps the most concise formulation of this normative vision of inclusive and egalitarian communication. In this situation, communication is “unhindered by external contingent influences, but also by constraints resulting from the structure of the communication itself,” so that all interlocutors “have the same chance to […] open up communications and to perpetuate them through speech, counter-speech, questioning and answering,” and there is an “equal distribution of chances to offer interpretations, assertions, recommendations, explanations and justifications” (Habermas, 2009, p. 148–149; translation by author).

Habermas considers this vision an ideal type, unlikely to be achieved in the real world of political communication. Instead, during discussions more or less sharp communicative asymmetries (Thornbury and Slade, 2006, p. 17–20; Beauvais, 2018, p. 147) may come to the fore, sometimes of an obviously social character, but often also at least on the surface resulting from interlocutors' own “self-silencing” (Sunstein, 2019, p. 84). If we conceive political conversations as “simple interaction systems” (Luhmann, 2005) based on the co-presence and mutual perceptibility of individuals, such asymmetries entail inequality between their members in the sense of discursive disadvantages for certain participants, and corresponding advantages for others. For instance, people might choose to hold back, refrain from expressing their views, and let others do the talking, so that the latter can take the lead in setting the conversation's agenda and let their particularistic viewpoints appear dominant or even consensual. Alternatively, interlocutors might contribute to discussions but veil or misrepresent their true standpoints (Kuran, 1998; Carlson and Settle, 2016). Participants can also try to avoid stating their views on certain topics by shifting the conversation to socially less uncomfortable or threatening subjects. Ultimately, interlocutors might even drop out of interactions and cease further efforts to contribute. The interactive dynamics of discursive inequality come most clearly to the fore when certain persons are silenced by others through intimidation or other means (Lupia and Norton, 2017, p. 69).

When fully inclusive and egalitarian, political talk “allows for maximum expression of interests, opinions, and perspectives relevant to the problems or issues for which a public seeks solutions” (Young, 2000, p. 23), and “effective hearing” for all viewpoints (Fishkin, 1991, p. 29). By contrast, if its equality is impaired by “systematic distortions of communication” (Habermas, 2009, p. 148; translation by author), its content may fail to reflect the full range of perspectives that exist in a society. The discursive representation (Dryzek and Niemeyer, 2008) of political views and positions is then curtailed, resulting in unequal chances to influence the final outcomes of the political discussions that take place at the foundation of society's deliberative system (Mansbridge, 1999; Neblo, 2015, p. 17–25), and ultimately inform deliberative democracy's political decision-making (Habermas, 1996).

Young (2000) has coined the terms “external exclusion” and “internal exclusion” to address the mechanisms by which social inequality is translated into discursive inequality during the stages of access and influence in political talk. External exclusion concerns access to arenas of political talk and refers to dynamics by which “people are kept outside the process of discussion” (Young, 2000, p. 55). Certain citizens are thereby de-selected from political conversations before they even start. As a result, even though everyone enjoys the necessary rights of expression and free speech, some citizens do not engage in political talk. Internal exclusion, by contrast, gives rise to communicative asymmetries between those that have accessed and partake in conversations. By disadvantaging certain interlocutors while advantaging others they affect how conversations evolve between those individuals that have entered them. As a consequence of internal exclusion, people that have gained access nonetheless “lack effective opportunity to influence the thinking of others” (Young, 2000, p. 55).

Research on the discursive inclusiveness and equality of everyday political talk in people's lifeworld has thus far concentrated on the threshold of access. It has registered significant imbalances. Some citizens discuss public affairs almost constantly, others more sparingly, and yet others not at all, and these differences are clearly associated with social structural attributes, cognitive and motivational dispositions, and characteristics of social networks (Jacobs et al., 2009, p. 43–63; Steiner, 2012, p. 38–45; Schmitt-Beck and Lup, 2013, p. 518–522; Eveland and Shen, 2021; Schmitt-Beck, forthcoming). Access to arenas of everyday political talk is thus characterized by inequality, and clearly subject to external exclusion. But how about the social process of such discussions, once people have accessed them? How egalitarian are they? In how far and in which ways are they characterized by communicative asymmetries, and thus affected by internal exclusion? If so, how does it work? Little is known about these questions (that pertain to the boxes highlighted by bold lines in Figure 1). Communicative asymmetries have been studied in easily observable real-world arenas of communication like deliberative mini-publics and online platforms as well as in laboratory experiments (Steiner, 2012, p. 46–49; Mendelberg et al., 2014; Gerber, 2015; Carlson and Settle, 2016; Siu, 2017; Beauvais, 2021; Kennedy et al., 2021), but with few exceptions (Cowan and Baldassarri, 2018) hardly ever with regard to everyday political talk as it spontaneously and informally occurs in people's lifeworld. Against this background, the following analyses attempt to break new ground by shedding light into the “black box of interaction” (Mendelberg et al., 2014) in citizens' casual conversations about politics.

To approach this object empirically the study draws inspiration from Knight's and Johnson's claim that deliberative democracy presupposes certain capabilities on the part of citizens. These “faculties” ensure people's ability to cope with the challenges of effective participation in its political process. Corresponding “deficiencies”, by contrast, may weaken it (Knight and Johnson, 1997, p. 281–282). These dispositions are in all likelihood not distributed evenly in society (Bohman, 1996, p. 107–132). Social inequalities and concomitant imbalances in citizens' control of relevant “resources and capacities” might give rise to differences between interlocutors with regard to advantages or disadvantages they experience during processes of discussion (Bohman, 1996, p. 122–123). Since it takes at least two to talk, attributes of the discussant networks within which political conversations take place should also play a major role, in addition to, but also interacting with participants' personal attributes (Huckfeldt and Sprague, 1995). The amount of disagreement encountered during talks can be expected to impair their symmetry particularly strongly (Nir, 2017).

Processes of internal exclusion in everyday political talk are not directly observable, but associations between these attributes and citizens' experiences of asymmetric communication indirectly point to their operation. They show who is adversely affected by them and which conditions render such disadvantages particularly likely. To flesh out these thoughts and render them empirically testable the next section proposes a model of asymmetric communication in everyday political talk that builds on scholarship on political participation, social networks and political communication. Without claiming to be exhaustive, it specifies how individuals' personal circumstances as well as characteristics of the social networks with whose members they discuss politics increase or decrease their vulnerability to internal exclusion2.

The model consists of a set of generic propositions about the interplay of factors that together give rise to experiences of asymmetric communication in everyday political talk (Figure 2). They are rendered accessible for empirical analysis in the form of testable hypotheses by specifying their implications for a range of structural and psychological attributes of individual interlocutors (indicated by angular boxes in Figure 2), as well as attributes of the discussant networks within which their conversations take place (boxes with rounded corners)3.

(a) Social structural inequalities may impose handicaps on certain groups that impair their members' capacity to engage in political discussions (Bohman, 1996, p. 107–149; Knight and Johnson, 1997; Young, 2000; Knops, 2006). Even under universal liberties and participation rights, such as most notably free speech, such “inequalities can produce asymmetries in social group members' abilities to use these universal empowerments” (Beauvais, 2018, 147). Indeed, it is exactly those societal groups that ought to profit most from deliberative democracy that might be least comfortable with political talk as its prioritized mode of political engagement, and consequentially suffer most from discursive inequality. Decades of research on political participation have shown that social structural detriments translate into political disadvantages, and that this regularity is especially pronounced for more demanding modes of activity (Schlozman et al., 2012; Dalton, 2017). Members of socially disadvantaged groups are less motivated, and often insufficiently endowed with skills that are instrumental for coping with the challenges of political participation (Verba et al., 1995). Research on political talk accordingly suggests that social marginalization has debilitating effects on access to discussions in both formal (Goidel et al., 2008; Karpowitz and Mendelberg, 2014; Griffin et al., 2015) and informal settings (Schmitt-Beck and Lup, 2013, p. 520–521). The model's first proposition therefore claims that structurally disadvantaged persons are more likely to be negatively affected by communicative asymmetries in everyday political talk (H1). In the following analyses this generic expectation will be examined for interlocutors' socio-economic status, gender, and immigrant background. The assumption is that individuals of low socio-economic status, females (Beauvais, 2021), and persons of immigrant origin tend to find themselves disadvantaged during political discussions because they are insufficiently endowed with relevant resources (see below).

(b) The second generic hypothesis states that people's “capacities […] to press claims once they enter relevant deliberative arenas” (Knight and Johnson, 1997, p. 281–282) are affected by psychological dispositions that imply important motivations and skills concerning politics more generally, and political communication in particular (H2.1). As they often originate from parental socialization during childhood and adolescence, these resources can to some extent, though probably not completely, be assumed to mediate the effects of social structural inequality on asymmetries in political conversations stated in H1 (H2.2). Potentially relevant general political motivations and skills include individuals' interest in politics, conceived as a stable “expectation that engaging with political content […] in the future will turn out to be rewarding” (Prior, 2019, p. 4), attitude strength regarding directional alignments like partisanship and ideology (Jacobs et al., 2009, p. 55–59), as well as internal political efficacy, that is, persons' confidence in their ability to make a difference in the democratic process (Jacquet, 2017). Political discussions demand also certain specific skills, among them a basic understanding of the thematized subject matters and some measure of articulateness and eloquence. A corresponding, task-related sense of efficacy, pertaining to one's competence to discuss politics (Rubin et al., 1993), can therefore be expected to privilege individuals in such situations even more strongly than the generalized resource of internal efficacy. People's orientations toward political conflict should also be consequential (Ulbig and Funk, 1999; Mutz, 2006; Sydnor, 2019). Adopting Testa et al.'s (2014) two-dimensional conception, it can be expected that conflict aversion—dislike of political confrontation and argument—weakens interlocutors' standing in political talks, whereas conflict seeking—feelings of excitement and enjoyment about dispute and contention—strengthens it (Sydnor, 2019, p. 21). Most of these orientations can be seen as resources that increase persons' ability to persist in political discussions, but conflict aversion should have the opposite effect.

(c) Unlike individualized forms of political engagement, talk about public affairs is a relational activity that cannot be performed in isolation. It takes place between the members of discussant networks (Huckfeldt and Sprague, 1995). Hence, whether conversations are symmetric or asymmetric should also depend on attributes of network members and their ties to one another. The amount of political disagreement between conversation partners can be expected to play a key role in this respect (Nir, 2017). Conflicts emerging from the pluralism of societal interests and value orientations are an inevitable feature of political life. Deliberative democrats argue that discussions that include all affected groups are the best mode of addressing this political heterogeneity. Without divergences of perspectives deliberation is indeed pointless (Thompson, 2008, p. 502; Martí, 2017). Since deliberative democracy should be rooted in citizens' everyday political talk, exposure to society's political diversity should be part and parcel of people's encounters with one another (Gutmann and Thompson, 1996; Tanasoca, 2020). However, many people dislike disagreement. They find it a source of tension, with a potential to disrupt highly valued social relationships, and accordingly uncomfortable (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 2002, p. 134–137; Mutz, 2006). In line with the homophily principle, people tend to prefer like-minded interaction partners (McPherson et al., 2001). Studies accordingly suggest that citizens try to avoid political conversations when they anticipate disagreement (Gerber et al., 2012; Settle and Carlson, 2019), talk less often (Huckfeldt and Morehouse Mendez, 2008; Song and Boomgaarden, 2019) and withhold their views (Cowan and Baldassarri, 2018) when it is present, and even may cease to discuss politics altogether when it becomes too contentious (Wells et al., 2017). Deliberative democrats' appreciation of disagreeable encounters with fellow citizens thus seems to go against the grain of how ordinary people structure their social life. This suggests that encounters with political disagreement increase interlocutors' likelihood to be disadvantaged in political conversations (H3).

(d) While disagreement stands out, certain other contextual features of discussant networks might also be of some relevance (H4). For instance, discussion partners' political competence could make a difference. Highly competent discussants can be expected to present their views firmly and confidently. This could let them appear intimidating and render it more likely to hold back on the part of those exposed to them (Sunstein, 2003, p. 14–18). Moreover, “strong ties” between family members and friends, that are characterized by closeness, trust and mutual liking (Straits, 1991), might be less conducive to asymmetric communication than “weak ties” of a functional nature (Granovetter, 1973), as they exist between mere acquaintances (Huckfeldt et al., 2004; Morey et al., 2012; Cowan and Baldassarri, 2018).

(e) The model's final proposition cuts across the other ones. It states that the association between these factors and experiences of asymmetric communication is not simply additive, but interactive. Specifically, it is expected that the impact of political disagreement is conditioned by social structural attributes, psychological dispositions, and other network attributes (H5). Individuals' vulnerability to the adverse effect of disagreement might be amplified by social structural disadvantages, conflict aversion, and high political competence on the part of their conversation partners. By contrast, the different facets of general politicization as well as talk efficacy, conflict seeking, and strong ties can be expected to increase people's ability to cope with disagreeable encounters, thereby rendering them more symmetric. In addition, research on autoregressive effects in social networks suggests that experiences of network disagreement are not all of one piece but characterized by complex interactions. It has shown that a discussion partner's influence on an individual is moderated by the latter's experiences with the other members of her discussant network. One study, for instance, has found that a discussant's influence is boosted if she is perceived as more knowledgeable about politics than the other network members, but weakened if she does not stand out in this regard in comparison to the other discussants (Richey, 2008). Regarding experiences of disagreement a similar mechanism might be at work. If that assumption is correct, the silencing effect of dyadic disagreement with a discussant is strengthened if conversations with the other network members are more agreeable, but curbed if all network members are similarly disagreeable (not visualized in Figure 2 for the sake of simplicity).

To test the expectations derived from this model the analyses draw on the Conversations of Democracy (CoDem) study: a high-quality face-to-face survey, based on a random sample of voting-age respondents, that was specially designed to examine German citizens' everyday political talk4. The study pursues two approaches of social network analysis. One set of analyses focuses on overall networks (Eveland et al., 2012, p. 240–243). It pertains to all respondents that reported to have discussed political matters with family members, friends or acquaintances during the past half year. Respondents that never discussed politics with a member of any of these reference groups are excluded from these analyses, leading to an active sample size of 1,576. The second approach is dyadic and zooms in on the individual members of respondents' core networks of most important political discussion partners (Marsden, 1987). Following the ego-centric approach to network analysis (Klofstad et al., 2009), respondents (in network terminology denoted as Ego) served as informants about their up to three most important discussants (denoted as Alteri). In total, this instrument yielded data on 3,428 Alteri. For the analyses these data are restructured in such a way that Ego-Alter dyads serve as units of analysis.

The following analyses focus on five different manifestations of communication asymmetry in everyday political talk. They are measured by the indicators documented in Table 1 which offers descriptive evidence on the prevalence and intensity of these experiences of disadvantage during political discussions5. What they all have in common is that individuals who are present during conversations do not share their thoughts and refrain from participating in the discursive scrutiny of other interlocutors' utterances. Despite being physically present in arenas of political talk and thus members of the same simple interaction systems (Luhmann, 2005) these persons tend to be “discursively invisible”, and consequently exert less influence on the course of discussions.

At the most basic level asymmetric communication manifests itself in the form of an unequal distribution of contributions. Accordingly, shares of speaking time or numbers of utterances across participants are established measures of political discussions' egalitarian character (Stromer-Galley, 2007; Freelon, 2010; Steiner, 2012, p. 268; Yan et al., 2018). Relying on indicators of this type, studies of deliberative mini-publics and online communication have detected significant imbalances (Steiner, 2012, p. 46–49; Graham and Wright, 2014). The data displayed for item (A) in Table 1 indicate that everyday conversations are characterized by a similar asymmetry (Neuwirth et al., 2007). While many participants meet the ideal of equal engagement, a minority assumes a more energetic role by speaking more than others, thus introducing an element of hierarchy. By contrast, about three times as many individuals describe themselves as mainly listening. Assuming a rather passive role, these persons do not contribute on par with others, often refrain from engaging in genuine dialogues, and thus forsake their influence on the course of the discussions in which they take part.

Inauthentic speech is a “subtle form[s] of self-censorship” (Bohman, 1996, p. 115) and thus a more covert manifestation of asymmetric communication. It may keep perspectives from the table despite the appearance of a dialogical exchange. Stating one's views sincerely is a key criterion of genuine deliberation. It is mainly emphasized by critiques of deception as a tool of selfish strategic communication (Steiner, 2012, p. 153–166). But insincerity might also take the form of preference falsification, that is, misrepresenting one's views in the face of social pressure (Kuran, 1998; Neuwirth et al., 2007; Carlson and Settle, 2016). Extant research has been primarily interested in individuals' perceptions of the truthfulness of perspectives expressed by fellow discussants in deliberative mini-publics (Steiner, 2012, p. 160–163). By contrast, item (B) in Table 1 is introspective. It queries whether respondents occasionally comply with viewpoints that they do not share in order to safeguard the social climate of an ongoing interaction. Less than half of the respondents firmly denied ever to resort to this kind of socially motivated misrepresentation of preferences. Nine percent clearly admitted to doing so.

Moving a conversation to other topics is another, more elegant way of avoiding to express views one does not want to reveal. Maneuvering away from problematic themes can help to prevent conversations from touching on conflictive matters and thereby becoming “dangerous” (Eveland and Hively, 2009). While easing social life and preserving precious relationships, this kind of behavior also potentially results in an incomplete range of viewpoints being expressed, and thus made available for discussion. Item (C) addresses this kind of behavior in a dyadic perspective, referring to discussions about potentially conflictive topics with individual members of respondents' core networks. In 20 percent of the examined dyads Ego admitted to altering conversation themes at least “sometimes” under such circumstances. Only less than half of all dyads appear completely unaffected by this phenomenon.

A particularly blatant manifestation of asymmetric communication is exiting a discussion altogether out of dislike where it is heading (Sunstein, 2019, p. 94–95). It means that one opts out and is then no longer part of the communication process. This experience is captured by item (D). One out of ten respondents reported to have “often” or “very often” backed out of a discussion in this way, whereas only a bit more than one out of four unequivocally claimed to have “never” withdrawn from a conversation about politics.

Apart from “self-excluding” behaviors that appear discretionary, asymmetry in political discussions can also result from certain discussants defining the terms of engagement for others. Silence may thus also come about as a response to intimidation and other coercive forms of interaction (Bohman, 1996, p. 112–123; Lupia and Norton, 2017). Outright interruptions, but also more subtle forms of socially constraining, disrespectful behavior (including non-verbal signals like face-making, yawning and the like) are therefore considered important indicators of asymmetric communication (Steiner, 2012, p. 268–269). Dialogue requires that everyone can contribute to the conversation in an unconstrained way. However, as can be seen from item (E), this is not always the case. More than one out of four respondents claimed to have “sometimes”, “often”, or even “very often” been denied the chance to speak out during a discussion to which they felt they could well have contributed. Only about 40 percent never experienced this kind of social silencing.

Gender is a dummy variable (1 = male, 0 = female). Parents' places of birth are used as a measure of immigrant background (1 = one or both parents born outside Germany, 0 = others). Education, occupational status and economic wellbeing are used to indicate socio-economic status. Education is a dummy variable contrasting respondents with completed upper secondary education (coded 1) from those with lower levels of formal schooling (0). Occupational status is measured by means of a scale that indicates the autonomy associated with respondents' (present, for retirees previous) occupations and has been shown to be highly correlated with occupational prestige. The lowest of its five categories consists of unskilled manual workers, the highest category includes employees and civil servants with advanced training occupying high-level supervisory positions as well as self-employed professionals and owners of larger companies (Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, 2003). To proxy for a direct measure of income the analyses refer to respondents' assessments of their current economic situation (five-point-scale from “very bad” to “very good”).

Political interest is measured by means of self-reports on a five-point scale from “not at all” to “very strongly interested”. The indicator of partisanship is derived from the German standard measure of party identification (Weisberg, 1999, p. 725) and takes the form of a five-point-scale ranging from non-partisans to very strong party identifiers. Ideological extremity is measured by means of an 11-point left-right scale folded at the midpoint. Internal political efficacy and political talk efficacy are measured by additive scales based on two items each (alpha = 0.61, resp., 0.72). Based on six items, a varimax-rotated principal component analysis confirmed the two-dimensionality of conflict orientations in line with Testa et al. (2014). It separated conflict aversion (Eigenvalue 2.43, explained variance 40.5 per cent) from conflict seeking (Eigenvalue 1.11, explained variance 18.6 per cent). Additive scales were constructed accordingly, with high values indicating high conflict aversion (alpha = 0.68) resp. conflict seeking (alpha = 0.61) (see Appendix for item wordings).

Three measures of political disagreement are employed in the following analyses. The measure of political disagreement experienced within overall networks relies on the standard approach for eliciting general disagreement common in social network research (Klofstad et al., 2013). It is based on questions querying respondents how often differences of opinion arose while they discussed politics during the 6 months preceding the survey with family members, friends and “acquaintances, such as neighbors or workmates”. Responses to these three questions are registered on five-point scales from “never” to “very often”. The questions are combined into an additive index. For core networks disagreement experiences are additionally measured on a dyadic basis for each Alter separately by means of the following statement (assessed on a five-point Likert scale): “[Alter] and I often have different opinions on politics.” Apart from indicating the amount of disagreement with the respective Alteri themselves, these data are also used to construct, for each dyad, a summary measure of disagreement with the (up to two) other Alteri from the same core network.

Other network features can only be examined for core networks. To indicate Alteri's political competence, the dyadic analyses refer to a measure of their perceived political interest (assessments, on five-point Likert scales, of the statement: “[Alter] is very interested in politics”). In addition, they also include a measure of the relationship between Ego and each Alter, consisting of a block of dummy variables, identifying spouses, relatives, and acquaintances, with friends as joint reference category.

The models presented in the following are estimated using linear OLS regression (with robust standard errors for the dyadic analyses, to account for the clustering of dyads within respondents)6. All models control for age (measured in years). Independent and dependent variables are normalized to range 0–1. A stepwise strategy of analysis is used. For each dependent variable the sequence sets out with two models that estimate the relevance of respondent's personal characteristics for experiences of asymmetric communication. The first model is purely social structural (M1), the second additionally includes the measures of psychological dispositions (M2). Model 3 adds network features by taking account of political disagreement. The dyadic analyses of core networks can be pushed even further by additionally including Alteri's political interest and Ego-Alter relationships (M4). Building on the most comprehensive additive models, the final step of the analysis examines interactions between political disagreement and personal characteristics as well as other features of social networks.

Table 2 pertains to asymmetries experienced in overall networks [with Table 1's items (A), (B), (D) and (E) as dependent variables], Table 3 to changing subjects during talks with specific Alteri within core networks [item (C)]. In quite complex patterns these experiences of communicative asymmetries in everyday political talk are indeed associated with social structural inequalities (M1). Women appear more likely to restrict themselves to listening, to withdraw from political conversations, and to feel silenced by others. Descendants of immigrants also appear more sensitive to internal exclusion, though only with regard to listening and preference falsification. Experiences of communication asymmetry do not seem to vary by education. But low occupational status is associated with a stronger inclination to listen rather than talk, to misrepresent one's political views, and to switch subjects when it gets uncomfortable. The latter is also more widespread among persons in adverse economic circumstances. All these associations are in line with H1 which expected social disadvantages to give rise to disadvantages in political discussion. However, effect sizes are mostly small, and the overall explanatory power of these structural attributes is rather weak.

Adding psychological dispositions improves the respective models' predictive power for every dependent variable, and in some cases massively (M2). These dispositions mediate the detrimental effects of structural disadvantages to some extent, as expected by H2.2, though not completely. The associations detected by M1 are weakened, but only the effects of low occupational status evaporate entirely. Surprisingly, when partialling out psychological dispositions preference misrepresentation appears slightly more prevalent among men. It is tempting to speculate that when matters get tense men find it preferable to comply with views they do not share and thus retain an active role in the conversation than to lapse into silence.

Dispositions that pertain specifically to political communication appear clearly more important than respondents' general politicization. Lacking confidence in one's verbal and cognitive proficiency for political discussions stands out as a particularly detrimental force. It undermines interlocutors' standing across all manifestations of asymmetric communication, giving rise to listening rather than talking, to misrepresenting standpoints in order to please others, switching subjects, withdrawing from conversations, and feeling silenced by other participants. Both conflict aversion and conflict seeking are also associated with experiences of asymmetry in political discussions, but the former more consistently than the latter. Conflict aversion appears to give rise to preference misrepresentation, withdrawal, and subject change. By contrast, conflict seeking individuals are less likely to retreat to a passive listening role and to misrepresent their views. Only the feeling to be silenced by others is unrelated to conflict orientations. Of the general dispositions, only political interest and ideological extremity appear important, though mostly not in the expected way. Lacking interest in politics is an important ingredient of passivity during talks, as expected. But it seems to diminish interlocutors' tendency to misrepresent their views, if only slightly. Perhaps uninterested individuals are simply not involved enough to bother about how they present themselves. Ideological extremists should be motivated to state their cases during conversations even in the face of resistance, but the single effect that emerges in Table 2 suggests otherwise. Those on the fringes of the ideological spectrum feel more often suppressed by others. Mostly in line with H2.1, these findings suggest that certain people are indeed less favorably disposed to cope with the challenges of everyday political talk than others. To some extent these relationships are ultimately rooted in subordinate positions in social hierarchies, in particular low socio-economic status. But this mediating role by no means exhausts the strong imprint that psychological dispositions, and among these especially those pertaining to political communication itself, leave on how interlocutors fare during conversations about politics.

As proposed by H3, exposure to political disagreement is strongly related to discursive disadvantages, though not for all dependent variables (M3). General disagreement with kin, friends and acquaintances strongly increases the likelihood to feel silenced and to withdraw from discussions. Due to the dyadic data structure a more complex perspective can be applied to switching topics during conversations with specific Alteri. According to Table 3, this tendency is strongly associated with the amount of disagreement encountered within the respective dyad itself. But to a lesser extent it is also affected by individuals' more general exposure to political disagreement in their overall networks. For core networks, the final model shows that other features of discussant networks may also affect experiences of disadvantage in asymmetric communications, in line with the generic hypothesis H4 (M4 in Table 3). In its specifics, however, none of these findings is as expected. The data suggest that the hypothesized simple dichotomy between strong and weak ties does not do justice to the discursive dynamics of conversations within core networks. Within strong ties a more complex pattern emerges, with a higher proclivity to switch subjects in talks with spouses and relatives than with friends. By contrast, Alteri's political interest does not appear relevant at all.

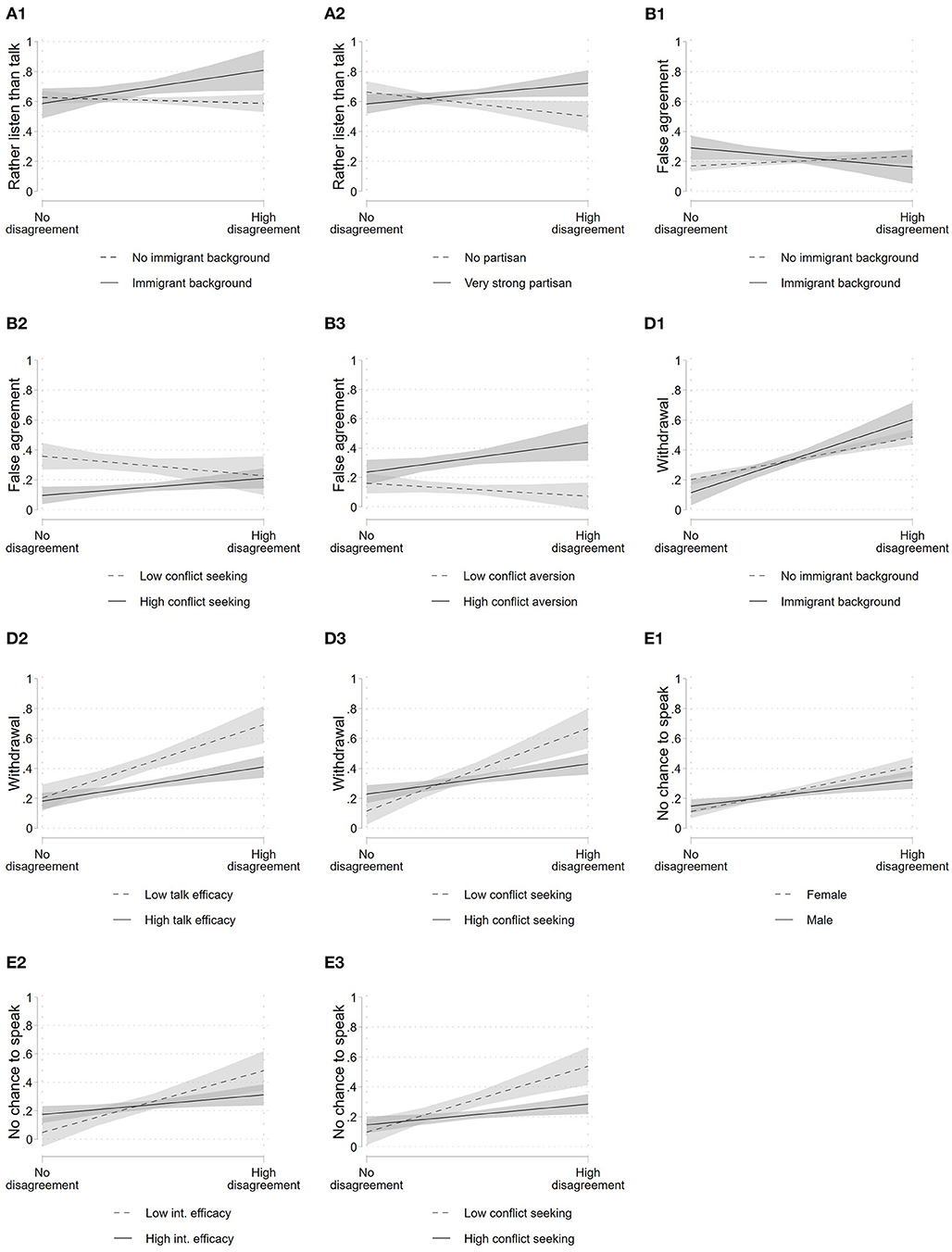

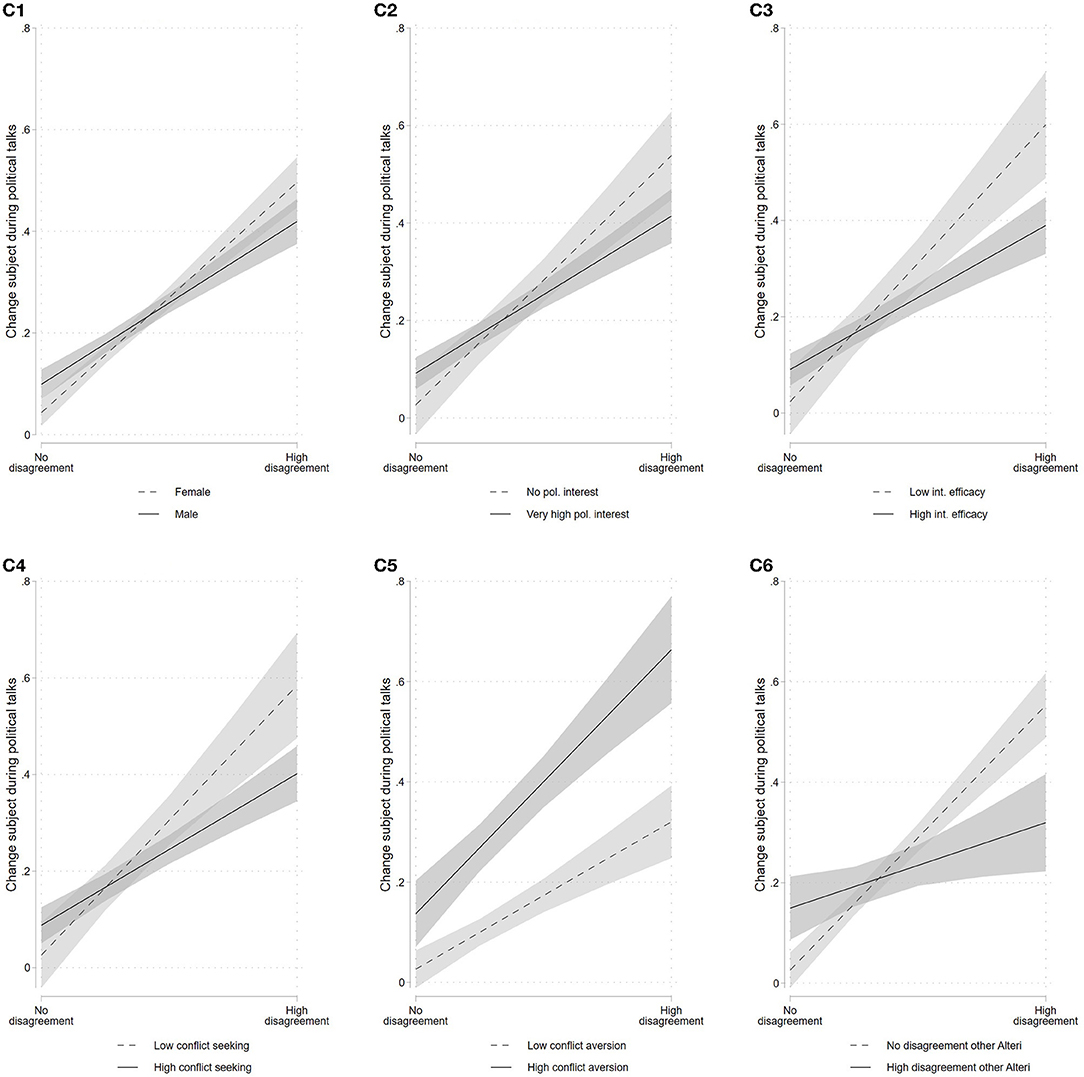

To examine H5, Figures 3, 4 show how the impact of political disagreement between discussants is moderated by social inequality, psychological dispositions, and network attributes. They were generated through a series of models that correspond to the full models discussed above (M3 in Table 2, resp., M4 in Table 3), but in addition test for conditional effects of disagreement by means of multiplicative interaction terms. The figures visualize the key findings of those models where statistical meaningful interaction effects emerged (with p < 0.10; the models are documented in the Supplementary Materials). This more fine-grained analysis reveals that people's tendencies to prefer listening over talking and to misrepresent their views, that had appeared unaffected under purely additive model specifications, are under certain conditions also sensitive to political disagreement. Thus, to a stronger or lesser amount all manifestations of disadvantage in asymmetric communications reflect interlocutors' exposure to political disagreement in their discussant networks. Judging from the sheer number of statistically meaningful interaction effects, the impact of disagreement appears conditional to a remarkable extent. These effects are not all similarly strong, but mostly they are in line with expectations.

Figure 3. (A1–E3) Conditional effects of political disagreement on asymmetric communication in overall networks.

Figure 4. (C1–C6) Conditional effects of political disagreement on asymmetric communication in core networks.

For instance, the association between exposure to disagreement and switching topics as well as feeling prevented from speaking up is more pronounced among women than among men. In a similar vein, among individuals of immigrant origin disagreement leads more often too passive listening and withdrawal from conversations. However, for preference misrepresentation unexpectedly the opposite pattern emerges. Perhaps such persons prefer silence over conformity when conversations get controversial. Echoing the findings for direct effects, psychological dispositions toward political talk itself appear particularly powerful as moderators. Yet, other than for direct effects, this pertains more to conflict orientations than communication efficacy. The latter only dampens the effect of disagreement on the tendency to withdraw from discussions. Conflict orientations, by contrast, appear particularly important as moderators of disagreement effects. This echoes findings from studies of other dependent variables (Mutz, 2006; Testa et al., 2014; Sydnor, 2019). The presumed immunizing role of conflict seeking appears for switching subjects, withdrawal, and the feeling to be silenced. Mirroring this pattern, highly conflict averse individuals display a stronger tendency to misrepresent their preferences or change subjects when encountering views different from their own. Surprisingly, among strongly conflict seeking individuals disagreement increases rather than decreases the tendency to misrepresent their views. This is not in line with expectations. Likewise unexpectedly, missing partisanship goes along with a weaker rather than stronger inclination to respond to disagreement by preferring listening over talking. Again in line with expectations, however, strong political interest to some extent appears to shield interlocutors against the urge to change subjects in response to growing disagreement. Similarly, among highly efficacious individuals, exposure to disagreement leads less often to subject switching as well as feeling silenced by others.

In a very specific sense, the role of disagreement is also moderated by network attributes. According to Figure 4C6, the effect of dyadic disagreement on switching subjects is almost completely neutralized when there is also pronounced disagreement with the other members of the core network. This is exactly as expected. Disagreeable discussants affect experiences of asymmetric communication much more strongly when they stand out by this capacity in comparison to the other members of the same network. Dyadic disagreement seems to stimulate a tendency to switch subjects on the part of Ego primarily when she is embedded in an otherwise mostly agreeable core network. Pervasive disagreement in a core network, by contrast, appears to immunize its members against specific influences of individual Alteri.

No definition of deliberative democracy fails to highlight the importance of inclusiveness and equality for this model of ideal democratic governance. But in its emphasis on political discussion deliberative democracy prioritizes a type of political activity that is considerably more demanding for citizens than electoral participation, the mode of activity constitutive for liberal democracy. As a consequence, exactly those societal groups that ought to profit most from deliberative democracy (Young, 2000; Knops, 2006) might be least comfortable with the mode of political engagement deemed crucial for its practice. Social and psychological handicaps might seriously impair people's prospects to engage and prevail in political discussions, thus giving rise to discursive inequality (Bohman, 1996, p. 107–149; Beauvais, 2018). Previous research has shown how access to the arena of everyday political talk varies across citizens and is associated with imbalances in structural resources as well as psychological motivations and skills (Schmitt-Beck, forthcoming; Schmitt-Beck and Lup, 2013). But little is known about what happens once individuals have entered an informal conversation about public affairs. The social process of political talk has thus far primarily been examined in laboratory experiments and by observational studies of communication in formalized settings like deliberative mini-publics or online platforms.

To get a better understanding of the role of everyday political talk in deliberative democracy the article examined citizens' experiences of a range of manifestations of asymmetric communication during casual day-to-day conversations about politics. The maxim of inclusiveness and equality prescribes that during political discussions “the possibility that a participant might influence the preferences of other deliberators be roughly the same for all participants. From the perspective of an individual participant, this serves to guarantee that no one will be unable […] to participate in the process of mutual influence that is at the core of democratic deliberation” (Knight and Johnson, 1997, p. 293). The analyses indicate that to a non-negligible extent this maxim is not fulfilled. Asymmetric communication is fairly widespread and takes different forms.

A considerable portion of those that partake in political talk mainly listens and contributes little to unfolding conversations. This passive communicative posture is not to be confused with “good listening” (Dobson, 2012) in the sense commended by deliberative democrats. Deliberative listening entails openness and receptivity for others' contributions, and it becomes valuable for deliberations when it leads to reciprocal “uptake” (Bohman, 1996, p. 59; Scudder, 2020) in the form of respectful and constructive responses. It cannot be ruled out that those mainly listening are attentive to others' needs, values, and viewpoints. Yet, by remaining mostly silent they do not contribute on par with others and fail to engage in a genuine dialogue, thus refraining from influencing the course of the discussion. Smaller shares of citizens even misrepresent their true standpoints, change subjects to avoid problematic topics, feel silenced by others, and even, ultimately, drop out of conversations. If we conceive political discussions as simple interaction systems (Luhmann, 2005) all these phenomena indicate experiences of inequality between their members.

This suggests that dynamics of internal exclusion (Young, 2000, p. 55; Beauvais, 2021) are at work that “undermin[e] the successful operation of the dialogical mechanisms on which deliberation depends” (Bohman, 1996, p. 116). Based on a model of asymmetric communication in everyday political talk it became apparent that exposure to political disagreement in discussant networks (Nir, 2017) is an important driver of these kinds of “self-silencing” (Sunstein, 2019, p. 84) and social silencing (Lupia and Norton, 2017) during political conversations. Importantly, the impact of disagreement appears highly conditional. Internal exclusion in everyday political talk thus appears as a complex process where social structural and psychological attributes as well as certain features of social networks exert direct effects on the likelihood to find oneself on the disadvantaged side in situations of asymmetric communication, but in addition also strengthen or weaken the detrimental impact of disagreement.

Social structural inequality is related to experiences of hierarchy in political talk, but its imprint appears all in all rather weak. While the impact of socio-economic status is largely mediated by psychological dispositions, this is much less the case for gender and immigrant background. Even controlling for a host of psychological dispositions concerning politics and communication, disadvantages during political conversations still appear somewhat more pronounced among women and persons of immigrant descent. But “deficiencies” in coping with the challenges of political discussions (Knight and Johnson, 1997, p. 281–282) due to feeble confidence in one's communicative competence and detrimental orientations toward political conflict play a much stronger role, both directly and as moderators of the deleterious effect of political disagreement.

These findings are worrisome for the normative vision of deliberative democracy. Everyday political talk, the mainspring of deliberative democratic politics according to authors like Habermas (1996), Mansbridge (1999) or Tanasoca (2020), falls short of the crucial imperatives of inclusiveness and equality. While other research has demonstrated this for access to political discussions (Schmitt-Beck and Lup, 2013), the findings reported in this article indicate that problems do not stop when citizens have managed to enter a conversation. As discussions unfold, even among those that were able to pass the threshold of access inclusiveness and equality remain precarious. Research on deliberative mini-publics suggests that in formalized settings smart design choices as well as careful moderation and facilitation can to some extent neutralize mechanisms of internal exclusion (Mendelberg et al., 2014). But in informal and spontaneous everyday political talk these options are not available. As an integral element of citizens' lifeworld under conditions of free speech, casually arising from their day-to-day interactions with fellow citizens (Conover and Miller, 2018), it is anathema to any kind of interference and regulation. With interlocutors being left to their own devices, conversations simply run their course. And that means: depending on network conditions and personal characteristics often certain participants will dominate the discussion, whereas others tend to say little or even stay altogether quiet.

These findings suggest that core aspects of deliberative democracy do not easily go together. They point to a tension between the inclusiveness and equality of political conversations that is a prerequisite for passing the threshold of influence on the part of all participants (Knight and Johnson, 1997, p. 280–282), and the experience of political disagreement in whose “absence […] deliberative democracy […] would be unnecessary” (Martí, 2017, p. 559). One of deliberative democracy's most prominent rationales is its presumed ability to deal with conflicting views about political goals in constructive and legitimate ways. Encounters with society's political diversity should therefore be an integral element of citizens' everyday communication about politics (Gutmann and Thompson, 1996; Sunstein, 2003; Tanasoca, 2020). However, several studies have shown that people are uncomfortable with opinion diversity and prefer to communicate with like-minded others. Adding novel insights to this line of research, the analyses presented in this article have shown that this tendency also contributes strongly to communicative asymmetries in citizens' everyday political talk. With respect to the informal conversations about public affairs casually occurring in citizens' lifeworld, an important purpose deliberative democracy is expected to address thus appears to impose a particular strain on the realization of its egalitarian and inclusive imperative.

Obviously, this research has limitations. Since its findings are derived from a single-country study, their generalizability to other countries should be clarified by future research. In comparative studies on people's propensity to talk about public affairs Germany stands out as a country with a high rate of political discussion (Schmitt-Beck, 2008). At the same time, the amount of political disagreement experienced by its citizens in their social networks is by and large moderate, due to its multi-party system where heterogeneity is mostly a matter of degrees rather than outright opposition and conflict like, most notably, in the dualistic two-party system of the United States (Schmitt-Beck and Partheymüller, 2016; Schmitt-Beck, forthcoming). Both pieces of indirect evidence suggest that Germany represents a best-case rather than worst-case setting with regard to the detrimental effects of internal exclusion in everyday political talk.

It should also be emphasized that the catalog of manifestations of asymmetric communication examined in this study is not exhaustive. All analyses focused on experiences of disadvantage during conversations where interlocutors, according to their own testimony, refrained from expressing their true views, or even any views at all. However, one can of course also imagine more subtle asymmetries where people speak just as much as others but are not listened to with the same openness (Bormann et al., 2021), so that their views are deprived of fair deliberative uptake (Scudder, 2020). Phenomena such as these still await study. Another limitation concerns the article's scope. It has identified conditions under which communicative asymmetries come about in everyday political talk, thus offering indirect evidence for mechanisms of internal exclusion that operate while citizens discuss politics with one another. But it has not demonstrated these mechanisms themselves. Survey research is not well suited for this task; qualitative case studies might be more appropriate for illuminating the discursive micro-dynamics through which such mechanisms unfold.

Finally, follow-up research should address the implications of the article's findings. According to deliberative democrats' understanding of discursive inequality, when the communicative input to conversations differs across interlocutors the risk arises that certain experiences and viewpoints are deprived of attention, and consequently of potential influence on discussion outcomes (cf. Figure 1). The present study has shown that everyday political talk is affected by communicative asymmetries. But the question how such imbalances in participation actually impair the discursive representation of citizens' perspectives (Dryzek and Niemeyer, 2008) and are ultimately reflected in concomitant differential influences on the outcomes of discussions necessitates further inquiry.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

This research has been funded by a project grant of the German National Science Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft DFG; grant SCHM 882/18-1: Political Talks and Democratic Politics).

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The author was indebted to Simon Ellerbrock, Manuel Neumann, and Christian Schnaudt for methodological advice and helpful feedback on a draft version of this article. The editor and two reviewers of this journal provided constructive criticism that greatly improved the article.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.798128/full#supplementary-material

1. ^It might be objected that ordinary people's participation in deliberative mini-publics is more important for deliberative democracy than their constant and widespread engagement in everyday political talk. This reflects the obvious mismatch between the rapidly growing literature on deliberative polls, citizen juries, consensus conferences and other (typically elite-initiated) procedures that engage samples of ordinary citizens in public discussions about pertinent policy issues that are designed to achieve high deliberative quality, on the one hand (Landwehr, 2020), and the much lower scholarly attention paid to everyday political talk as it unfolds informally in people's lifeworld, on the other (Conover and Miller, 2018). However, in recent years this development has come under criticism as a tendency to concentrate on the practical challenges of democratic deliberation among a chosen few in artificially constructed settings at the price of losing sight of the much more ambitious goal of deliberative democracy itself. Critics went so far as to diagnose a “broken link with mass politics” in need of “rebuilding” (Bächtiger and Parkinson, 2019, p. 56–57, 76–79). Others accused this literature of downplaying the democratic element in a shift toward “participatory elitism where citizens who participate in face-to-face deliberative initiatives (and only a small fraction do) have more democratic legitimacy than the mass electorate” (Chambers, 2009, p. 344; Lafont, 2020, p. 138–160; Tanasoca, 2020). This is vividly illustrated by a recent study of mini-publics in the UK that calculated that since the inception of this innovative institution not more than about 0.002 percent of the population had yet the chance to be selected for participation in such an event (Boswell, 2021). In line with these perspectives, the present article departs from the premise that in deliberative democracy authoritative decision-making should enjoy legitimacy only when preceded and nurtured by inclusive and egalitarian discussions within the citizenry at large (Schmitt-Beck, forthcoming). Mini-publics are an important element of the deliberative system, to be sure, but they cannot replace everyday political talk in citizens' lifeworld. Rather, they should be nurtured and fertilized by citizens' ongoing informal conversations with their associates (Dutwin, 2003; Neblo, 2015, p. 17–25; Schmitt-Beck and Grill, 2020).

2. ^Note that I use the language of causality with caution. Since the data used in the following analyses are cross-sectional I mostly cannot claim to demonstrate causal relationships. Since the phenomena of interest are all of high intra-individual consistency over time, panel data spanning long sections of respondents' life cycles would be needed to show causal relationships.

3. ^The model is premised on the condition that access to political conversations has already been gained. It is accordingly conceptualized in terms of direct instead of moderator effects.

4. ^Based on a register-based one-stage random sample, 1,600 interviews with voting age citizens were completed between 15 May and 24 September, 2017. Following the model of major studies of political communication in citizens' lifeworld (Lazarsfeld et al., 1968; Huckfeldt and Sprague, 1995; Conover et al., 2002; Huckfeldt et al., 2004) the study was conducted locally. Its site was Mannheim, a city in the South of Germany characterized by the variegated social structure, economy, culture, and political life of a typical mid-sized German city. Fieldwork was carried out by a professional survey firm (Förster and Thelen, Bochum). For methodological details of design and fieldwork cf. Grill et al. (2018). Representativity tests of the data are documented in the Supplementary Materials; representativity is high except for a substantial overreporting of turnout that is typical for political surveys (McAllister and Quinlan, 2021).

5. ^From a theoretical point of view it would have been desirable to collect data concerning these manifestations of communication asymmetry for overall and core networks in parallel. However, for methodological reasons this was not possible. One impediment was scarcity of questionnaire space. Ego-centric network instruments require to pose all name interpreter questions for every Alter named in response to the name generator question that defines the network. Each additional name interpreter question thus leads to a significant expansion of interview time. A related problem is respondent fatigue caused by the repetitive nature of these questions, and the correspondingly rising risk of nonresponse or even interview abortion (Perry et al., 2018). Consequently, ego-centric network instruments generally need to be kept as parsimonious as possible. In Table 1, item (C) refers to discussions with core network Alteri whereas the other items pertain to overall networks.

6. ^Rerunning the same analyses using ordered logit models did not lead to substantively changed results.

Bächtiger, A., Dryzek, J. S., Mansbridge, J. J., and Warren, M. (2018a). “Deliberative democracy: an introduction,” in The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, ed. A. Bächtiger, J. S. Dryzek, J. J. Mansbridge, and M. Warren (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1–31. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747369.001.0001

Bächtiger, A., Dryzek, J. S., Mansbridge, J. J., and Warren, M., (eds.). (2018b). The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bächtiger, A., and Parkinson, J. (2019). Mapping and Measuring Deliberation. Towards A New Deliberative Quality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780199672196.001.0001

Barber, B. R. (1984). Strong Democracy. Participatory Politics for a New Age. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Beauvais, E. (2018). “Deliberation and equality,” in The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, ed. A. Bächtiger, J. S. Dryzek, J. J. Mansbridge, and M. Warren (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 144–155. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747369.013.32

Beauvais, E. (2021). Discursive inequity and the internal exclusion of women speakers. Polit. Res. Q. 74, 103–116. doi: 10.1177/1065912919870605

Bohman, J. (2006). Deliberative democracy and the epistemic benefits of diversity. Episteme 3, 175–191. doi: 10.3366/epi.2006.3.3.175

Bormann, M., Tranow, U., Vowe, G., and Ziegele, M. (2021). Incivility as a violation of communication norms-a typology based on normative expectations toward political communication. Commun. Theory. doi: 10.1093/ct/qtab018. [Epub ahead of print].

Boswell, J. (2021). Seeing like a citizen: how being a participant in a citizens' assembly changed everything I thought I knew about deliberative minipublics. J. Deliberat. Democracy 17, 1–12. doi: 10.16997/jdd.975

Cammack, D. (2021). Deliberation and discussion in classical Athens. J. Polit. Philos. 29, 135–166. doi: 10.1111/jopp.12215

Carlson, T. N., and Settle, J. E. (2016). Political chameleons: an exploration of conformity in political discussions. Polit. Behav. 38, 817–859. doi: 10.1007/s11109-016-9335-y

Chambers, S. (2003). Deliberative democratic theory. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 6, 307–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.6.121901.085538

Chambers, S. (2009). Rhetoric and the public sphere: has deliberative democracy abandoned mass democracy? Polit. Theory 37, 323–350. doi: 10.1177/0090591709332336

Chambers, S. (2012). “Deliberation and mass democracy,” in Deliberative Systems. Deliberative Democracy at the Large Scale, ed. J. Parkinson and J. Mansbridge (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 52–71. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139178914.004

Cohen, J. (1989). “Deliberation and democratic legitimacy,” in The Good Polity. Normative Analysis of the State, ed. A. P. Hamlin and P. N. Pettit (Oxford: Basil Blackwell), 18–34.

Conover, P. J., and Miller, P. R. (2018). “Taking everyday political talk seriously,” in The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, ed. A. Bächtiger, J. S. Dryzek, J. J. Mansbridge, and M. Warren (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 378–391. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747369.013.12

Conover, P. J., Searing, D. D., and Crewe, I. M. (2002). The deliberative potential of political discussion. Brit. J. Polit. Sci. 32, 21–62. doi: 10.1017/S0007123402000029

Cowan, S. K., and Baldassarri, D. (2018). ‘It could turn ugly': selective disclosure of attitudes in political discussion networks. Social Netw. 52, 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2017.04.002

Dalton, R. J. (2017). The Participation Gap: Social Status and Political Inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198733607.001.0001

Dobson, A. (2012). Listening: the new democratic deficit. Polit. Stud. 60, 843–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00944.x

Dryzek, J. S., and Niemeyer, S. (2008). Discursive representation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 102, 481–493. doi: 10.1017/S0003055408080325

Dutwin, D. (2003). The character of deliberation: equality, argument, and the formation of public opinion. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 15, 239–264. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/15.3.239