- Centre Urbanisation Culture Société, Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique (INRS), Montreal, QC, Canada

In Quebec, in 2004, a new municipal political party was created in Montreal: the Projet Montréal party. Several aspects distinguish this party from other municipal political parties. Among these—the supposedly particular composition of the party's team and its activists, which brings together academics, environmental activists and experts in urban planning and transportation—attracts attention. The objective of this paper is to verify the specificity of the profiles of elected officials of the Projet Montréal political party by comparing them with those of other elected officials affiliated with municipal political parties between 2009 and 2017. Based on an extensive documentary survey of the 103 elected officials of the City of Montréal during the last three municipal elections, we will present how the profiles of elected officials differed depending on whether or not they belonged to Projet Montréal. More specifically, we will show that the profiles of Projet Montréal officials are more pronounced in the area of “mobility, urban planning, and environment” understood as one broad entity, whereas those of the other parties are stronger in the fields of administration and commerce. That said, the characteristics of the Projet Montréal team did shift over the course of the elections, insofar as officials with an education in the respective mentioned fields have made way for participants with more of an activist and volunteer profile. This research thus offers a first different and longitudinal look at the evolution of a municipal political party, the project it carries and the way in which the elected officials who compose it contribute to the identity of the party. By doing so, this study also shed light on municipal democracy and the conditions of entry into political office in that context.

Introduction

In Quebec, in 2004, a new municipal political party was born in Montreal: Projet Montréal. Despite the limited presence of municipal political parties in Quebec, the birth of a new political party is not an exceptional event, especially in the context of the 2000s, when municipal restructurings led to the creation of new political formations in the province (Mévellec and Tremblay, 2013). Nevertheless, in many ways, this formation is different from other municipal political parties. Four characteristics support this idea.

First, the ideological positioning of municipal political parties is generally unclear in Quebec. Indeed, municipal political parties are not branches of provincial or federal political parties and their positioning on a left–right axis is often unclear. Second, their political agenda is often weak and difficult to differentiate. Third, the duration of these groups is generally short and mainly linked to the victory of the leader. Finally, the internal organization of these groups is poorly structured and partisan life is absent (Bherer and Breux, 2012). The Projet Montréal party, however, does not fit this model. From an ideological point of view, although it is not an etiquette the Party wished to present themselves explicitly with (Beaudet, 2019), the positioning of this party on the left of the political spectrum is clear (Latendresse, 2013). From the outset, the party's platform was based on a specific political project aimed at reducing the role of the automobile and promoting public and active transportation. Moreover, little known in 2004, and despite two successive defeats of its leader in the mayoral race, the party has survived and in 2017 put its first mayor into office. The structure of this party is very organized, with a considerable degree of activism taking place between elections (Latendresse and Frohn, 2011). Aside from the undeniable specificity of this party, yet another element stands out.

Indeed, from the birth of the party, some observers have pointed to the particular composition of the party's team and its activists: “Coming mostly from the middle class, they are involved in environmentalist organizations or in the life of their neighborhoods” (Latendresse and Frohn, 2011, 106, our translation) and “[…] the Projet Montréal team includes several established academics in urban planning and transportation who are, as is he [their leader], inspired by the best practices of avant-garde cities in various countries” (Beaudet, 2019, 206; our translation). Commitments to the environment and mobility are most often associated with so-called green or ecologist parties (Jerome, 2014), despite the diverse realities that such labels can cover. Although at its beginning Projet Montréal rejects such a label (Beaudet, 2019), the party's composition invites us to question the commitments of this party's elected officials to their party, in order to see how they differ, or not, from those of the elected officials of other parties.

The possible specificity of the commitments of Projet Montréal's elected officials is of interest, especially since Montreal elected municipal officials have been known to be volatile in terms of their partisan affiliation (Collin et al., 2009), whereby commitments to certain objectives or values do necessarily go hand in hand with being elected under the banner of a specific party. Moreover, between 2009 and 2017—that is, during the last three elections—the number of elected officials belonging to Projet Montréal increased from 14 to 51, the party changed leaders, and some elected officials left the party. These are all elements that are likely to influence the very identity of the party and the elected officials who compose it.

The specific identity of Project Montréal could also be discussed in relation to work on growth coalitions and urban regimes (Molotch, 1976). The commitment to sustainable urban planning and mobility could be associated with anti-growth coalitions (Ségas, 2021) or what has been coined “slow-growth regimes” [to control and limit urban development, DeLeon (1992)]. That said, Henderson (2013) argues that, based on the example of San Francisco, political commitments with regard to sustainable mobility at the municipal level is not only pursued by political actors and parties defending a progressive and social justice agenda. It is also driven by actors with green urban development agenda that he interprets as being neoliberal. Our endeavor here is not to characterize Projet Montréal in these terms but more to understand the composition and identity of the party on the basis of the experiences of the elected candidates it attracts.

In this context, the objective of this paper is exploratory and modest: to identify the volunteer and professional commitments of elected officials of Projet Montréal before they took office, and to compare them with those of elected officials affiliated with other political parties between 2009 and 2017. We will begin by presenting the literature that addresses the background of elected municipal officials before they take office. While the importance of community commitments, as well as university education, profession and political experience, are often highlighted, membership in a political party can reveal a number of specificities. We will then describe our methodological approach. Based on an extensive documentary survey of the 103 elected officials of the City of Montréal during the last three municipal elections, we will present the way in which elected officials' profiles are distinguished according to their membership, or not, to Projet Montréal. More specifically, we will show that the importance of experience in the field of “mobility, urban planning and environment” among Projet Montréal's elected officials differentiates this party from other Montreal political parties. Although these profiles do not comprise the majority within the Projet Montréal party, they still stand out from those of other parties, where commitments in the fields of administration and commerce are more common. It should be added, moreover, that this distinction of Projet Montréal was initially, in the first term, generated by elected officials who had a university education in disciplines relating to “mobility, urban planning, or environment” whereas in addition to this trend (that continues), a growing number have experience from their volunteering or activist activities in 2013 and 2017. This study thus offers a different and longitudinal look at the evolution of a municipal political party, the project it carries and the way in which its elected officials contribute to the identity of the party and its ideological positioning.

Profiles of Elected Municipal Officials: Trends and Specificities

In general, the profiles of elected municipal officials are relatively well documented, particularly in Europe, where several major studies have been conducted on this topic (Egner et al., 2013; Heinelt et al., 2018). In Canada, and more specifically in Quebec, the literature on elected official's profiles is still patchy. Moreover, while the European literature emphasizes that the profile of elected officials varies, in Europe, according to political party affiliation, this dimension has not yet been explored for Quebec, due in particular to the specificity of the municipal partisan scene.

The Profile of Elected Municipal Officials in General

The body of research on the profiles of elected municipal officials is first distinguished according to the elective position (mayor or councilor). Once this distinction is made, the description of the profiles focuses on similar areas: volunteerism or activism, occupation, and political experience. To these domains are added socio-demographic variables such as age, gender, and level of education. This information, coupled with a set of institutional variables, makes it possible to draw up a profile of the elected officials as well as the course of their careers. Moreover, the nature of past experiences provides insight into the knowledge acquired and the way in which it can feed a political career.

The type and nature of volunteer or activist involvement is one of the first commonalities generally found among elected municipal officials on both sides of the Atlantic. In Europe, Verhlest et al. (2013) highlight that some municipal councilors have done volunteer work before entering politics. Indeed, in Quebec as well as in Europe, experience in the community or in sports and leisure associations is often the starting point for the careers of elected municipal officials (Steyvers and Verhelst, 2012; Mévellec, 2018). Simard, in his analysis of elected officials in the metropolises of Montreal, Longueuil and Gatineau, specifies that: “In total, 141 people, or 63.5% of all elected officials, have been active in community organizations and in various associations” (Simard, 2005, 153, our translation). A few years later, a study by Mévellec and Tremblay (2016) goes further by specifying the areas of involvement of a portion of the elected officials of medium-size and large municipalities in Quebec. Mévellec summarizes as follows: “The majority of elected officials (71%) had significant social capital before entering municipal politics that they had generally acquired through education and community activities as well as sports and clubs (Optimists, Knights of Columbus, and Kiwanis)” (2018, 162).

Mévellec and Tremblay (2016) also determined that these pre-election commitments respond to a gendered logic: women's capital is less activist than that of men. This confirms the findings of Simard (2005), who conducted research in certain large Quebec cities a few years earlier. According to this author, women benefit from volunteer and activist involvement, due to the knowledge that this experience provides, in the exercise of their functions as elected officials. Navarre (2015), for her part, referring to a study she conducted on the sociology of municipal elected officials in a French region, stated that (our translation) “one of the hypotheses of our survey was that activism is a resource for elected officials. In other words, the exercise of an activity or even activist responsibilities were seen to provide knowledge and practices useful for all political mandates.” She concluded, however, that it is even more the profession exercised—and sometimes the university education—that constitute assets for the exercise of the function. According to Mévellec and Tremblay's study, men and women also differ with regard to the nature of their pre-election commitments insofar as they do not invest in the same kinds of organizations. For example, men are more involved in sports and labor organizations than women. This finding is not insignificant because it suggests that men's and women's networks are distinct.

Furthermore, Verhlest et al. (2013) show that European municipal politicians often have a university degree and that their profession is part of the “typical talking or brokerage profession [politician, civil servant, business manager, teacher, liberal profession]” (p. 34). Elected municipal officials' previous political experience is also a notable feature of their background. In the European case, the same authors show the importance which membership in a political party at a higher level of government can have for certain municipal councilors. It should also be noted that the aim of all these studies is often to determine the councilors' degree of professionalization, in addition to their profile. A number of works have shown the multiple dimensions covered by the term “professionalization,” such as the holding of a paid position (often linked to the number of hours worked) and the acquisition of certain skills, an ethos and a political background (Michon and Ollion, 2018). This last element is not unrelated to political party membership.

Membership in a Political Party

Studies on professionalization, both in Quebec and in Europe, often focus on two ideal types to characterize the career of the elected official: the amateur and the professional. In the case of Quebec, Mévellec describes these two profiles as follows:

The first is “apolitical and amateur,” focusing on the function of service, territorial proximity at the ward level, being the face of independent elected officials, and on the continuity of commitment to the community. The other type is “professional and political” and focuses on “delivery,” the city level, a close link to the municipal political parties, and a strong dissociation between politics and other social activities” (2018, 162).

Verhlest et al. (2013) point out that elected officials tend to combine characteristics of both ideal types, it being understood that the size of the municipality and membership in a political party may influence the profile of elected officials.

In both Canada and Europe, research has shown that the larger the size of the municipality, the greater the degree of professionalization of elected officials (Steyvers and Verhelst, 2012; Sancton, 2015), suggesting that the figure of the amateur and apolitical elected official is less present in the most populous municipalities. As far as political parties are concerned, their intervention in the professionalization of elected officials can be achieved in two ways: by influencing recruitment; and by playing on the ideological label under which an elected official wishes to run. Steyvers and Verhelst (2012) indicate that “Party types matter in terms of either a more selective (liberal or ecologists on certain aspects) or more open process (socialist or ecologist on alternative aspects) when seen from the perspective of professionalization” (p. 10).

Membership in a political party is thus likely to contribute to the definition of the elected official's career and to understanding their choice to run under a particular label. For example, several analyses in France have established a link between activism or community commitment in the environmental field and a political career within a party where these themes are prioritized (Darvicje et al., 1995). Similarly, in her analysis of the activist career paths (of both elected officials and activist) of the French Green Party, Jerome notes that these activists do hold university degrees, yet in fields that do not traditionally prepare them for political office (such as communications or political science). They often come from politically engaged families and have experience in politics. Their involvement in the party is often a continuation of their daily lives. Jerome describes their involvement as follows (2014, 19, our translation):

Their political and social identity is rooted in specific lifestyles (sorting and recycling of waste, rational use of non-renewable resources—air, water, fuel…—preference for recycled materials and products, priority use of public transport, and non-polluting modes of travel, choice of ecological materials and textiles, shopping at organic stores and cooperatives, vegetarianism, etc.), and in the causes they defend (preservation of the living environment, participatory democracy in the neighborhood, anti-racism, alterglobalism, anti-capitalism, anti-consumerism, non-violence, defense of social rights and the rights of minorities, etc.).

To our knowledge, there are no analyses of this type in the Quebec context, mainly because of the vague or absent ideological positioning of municipal parties, their low degree of organization and their often short life span.

At the end of this brief literature review, several things stand out. First, in Quebec, elected municipal officials tend to have volunteer and activist experience before taking office, albeit this experience may well vary in intensity and nature depending on the type of office. While commitments are often related to the community, sports, education, recreation, culture, and unions, it is not known whether they vary according to the party affiliation of the elected official, as is the case in European studies, due to the relative duration of municipal political parties in Quebec. Second, the analyses conducted in Quebec show that gender is likely to play a role in the nature of pre-election commitments. Nevertheless, they have not, to our knowledge, taken into account political parties, and more specifically, a comparison between parties. Finally, studies have shown that university education, profession, and previous political experience are likely to modify the commitment trajectories of elected officials, as well as their affiliation to a specific political party. However, as these data remain very patchy in Quebec, the volunteer and professional commitments of elected municipal officials affiliated with a municipal political party merit further research. In this sense, two dimensions of the professionalization of elected officials—namely, the acquisition of specific skills and know-how, and the political career path leading to political party membership—need to be studied.

Methodological Approach

In order to understand the possible differences between the profiles of elected officials of Projet Montréal and those of Montreal's other municipal parties, we conducted an extensive documentary survey in the summer of 2019. The objective was to retrace the path of Montreal's elected officials since the last three elections (2009, 2013, 2017). The date of 2009 was chosen because it was the election where the Projet Montréal party made a breakthrough on the electoral scene (14 seats out of 103), while the 2017 election claimed the victory at the mayor's office (51 seats out of 103). Between 2009 and 2017, nine political parties were present at the time of the municipal elections: Union Montréal, Vision Montréal, Projet Montréal for the 2009 election; then Équipe Denis Coderre, Vrai Changement, Coalition Montréal and Projet Montréal for the 2013 election; and, finally, Équipe Denis Coderre, Projet Montréal and Coalition Montréal for the 2017 election. Independent elected officials (with no party affiliation) were also excluded from the analysis, as well as the few elected officials who ran under the label of a borough party. There are 102 councilors (including city and borough councilors) and one mayor in Montreal1.

The documentary research was carried out using specific internet sites: LinkedIn, Wikipedia, the candidates' pages on the sites of the political parties, and/or municipalities (insofar as they were incumbent), the biographical notes sometimes featured on the site of the National Assembly of Quebec, as well as a review carried out by the Conseil des Montréalaises sur les élues à Montréal (Conseil des Montréalaises, n.d.). The information was sometimes supplemented by newspaper articles when the information was available. Of course, such information cannot be considered a perfect mirror of reality. It is, rather, much more a question of how elected officials portray their trajectories and the competencies that flow from them. The type of data collection implies that some forms of past involvement of elected officials may not have been noted in the sources consulted, which implies a certain margin of error in the figures presented. Nevertheless, the extent of the difference in commitments between Projet Montréal and the other parties, particularly in the category of “mobility, the urban planning, and the environment” is notable and appears to far exceed this margin of error.

A database by election year was then created, based on the following categories: name, gender, borough, type of position, district, political party, date of first municipal elected position obtained. This initial information made it possible to draw up a portrait of the number of incumbent candidates elected and the number of women elected by political party. This was followed by education (level of schooling and type of degree, such as undergraduate degree in political science), previous occupation(s) and previous social commitments.

This data allowed us to create a second database where past experiences, both volunteer and professional, were categorized by field. These fields, which were determined with the literature review, are: (1) community involvement, sports, and recreation, (2) communication, (3) administration and management, (4) commerce and business, and (5) mobility, the urban planning and environment (which includes street changes, walking and cycling promotion, public transportation, road redesign, pollution prevention, heritage, and natural habitat and park preservation). Subsequently, a third database was created to identify the nature of this commitment, differentiating between whether a commitment resulted from experience (field or professional), academic training or both (experience and academic training). The categories of involvement reflect the topic of education or experience which a given elected official highlights in his or her CV and short biography. For example, if the short bio presents the official as having worked in urban planning for a municipal administration, he or she would be put into the Mobility, urban planning, and environment category. Yet if his or her prior jobs were self-described as being in management and administration, he or she would be put in the administration category. Or, if someone was involved in mobility issues (e.g., for traffic calming measures) in a community organization, that would belong to the category mobility, urban planning, and environment. The category community involvement, sports, and recreation would be checked only if the official's prior experience was associated with social justice and community support to the most vulnerable or with sports or recreation activities in the neighborhood.

In the following section, we will present the results of this survey. We will begin with a general portrait of the commitments of elected officials, by election year. It is not possible to look at the commitments of municipal elected officials by political party from 2009 to 2017 because the political parties have changed from one election to the next. Indeed, Projet Montréal is the only party to be present during these three elections. In 2009, there were three political parties; in 2013, there were five; and in 2017, three. Moreover, the political context from one election to the next was very different. For example, in 2009, the issue of the impact of mergers/demergers was still on the agenda, while in 2013, it was the revelations of corruption scandals that changed the landscape, in addition to the Montreal transportation debates we will discuss below. Then we will highlight the main trends that are emerging with regard to the nature of the commitment, namely, elected officials with no specific experience, those with a university education in the field and those having both. We will also look at whether these commitments are the same for men and women, taking recourse, in particular, to the work of Mévellec and Tremblay (2016), who showed that commitments prior to an election reflect a certain gender logic.

Secondly, we will look more specifically at the commitments of elected officials in the field of “mobility, urban planning, and environment” and will detail the nature of these commitments. We will show trends in the types of commitments for all elected officials of Projet Montréal, and will look in particular at the detailed background of flagship officials (so called because of the media coverage they receive), who illustrate the identity and color of the party, along with the background trends on the experience of the elected officials who are committed to this distinctive theme. Here, in addition to the database on the profile of the elected officials, a media analysis of the national and local dailies of the concerned boroughs, available on the Eureka database, was carried out to deepen the positioning of these officials. To this was added a comparative analysis of Projet Montréal's electoral programs in (Projet Montréal, 2009, 2013, 2017), as well as previous work by one of the authors on the debates on transportation and mobility in Montreal (Van Neste and Sénécal, 2015).

Elected Officials of Projet Montréal: A Specific Profile?

An analysis of the commitments of Projet Montréal's elected officials from 2009 to 2017 shows that some of them are very specific and linked to the field of “mobility, urban planning, and environment” a field that is absent (or nearly absent) from the commitments of the elected officials of the other political formations present during this period. The other political formations, despite their sometimes ephemeral nature and their diversity, bring together elected officials who are more familiar with the fields of administration and commerce. A more detailed analysis by year of election will make it possible to clarify these main features.

Evolution of Profiles Election by Election

For the year 2009, the electoral scene is relatively easy to read, in that only three parties are present. The Union Montréal party was created in 2001 by Gérard Tremblay. The Vision Montréal party, founded in 1994, is led by a former provincial minister. Yet Projet Montréal is more or less a new player because, although created in 2004, it was still little known to the public. The party leaders' debates prior to the 2009 election ensured that the party and its leader would be able to take advantage of this visibility (Latendresse and Frohn, 2011, p. 105). Union Montréal won the election with 68 seats, compared to 19 for Vision Montréal and 14 for Projet Montréal.

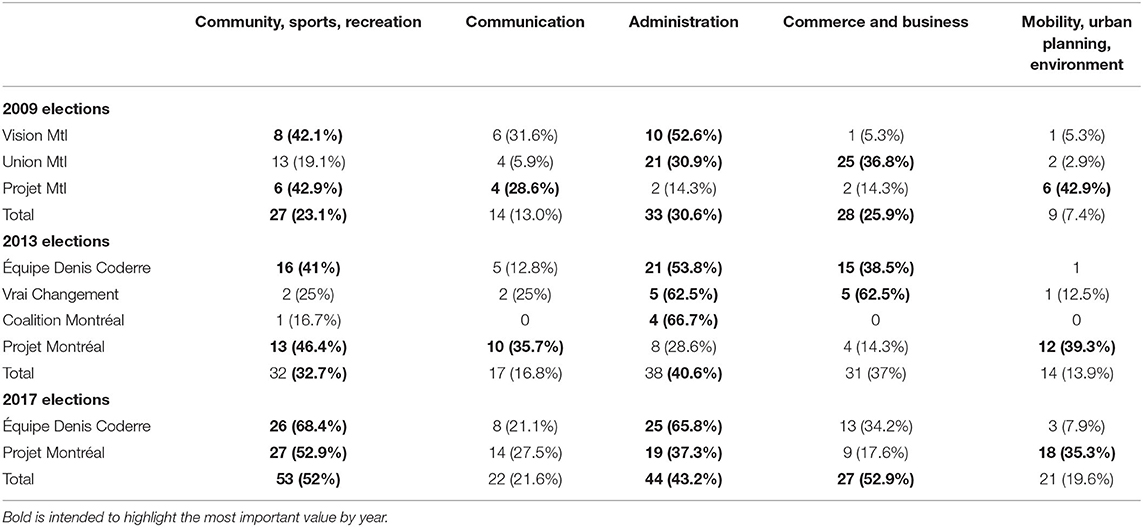

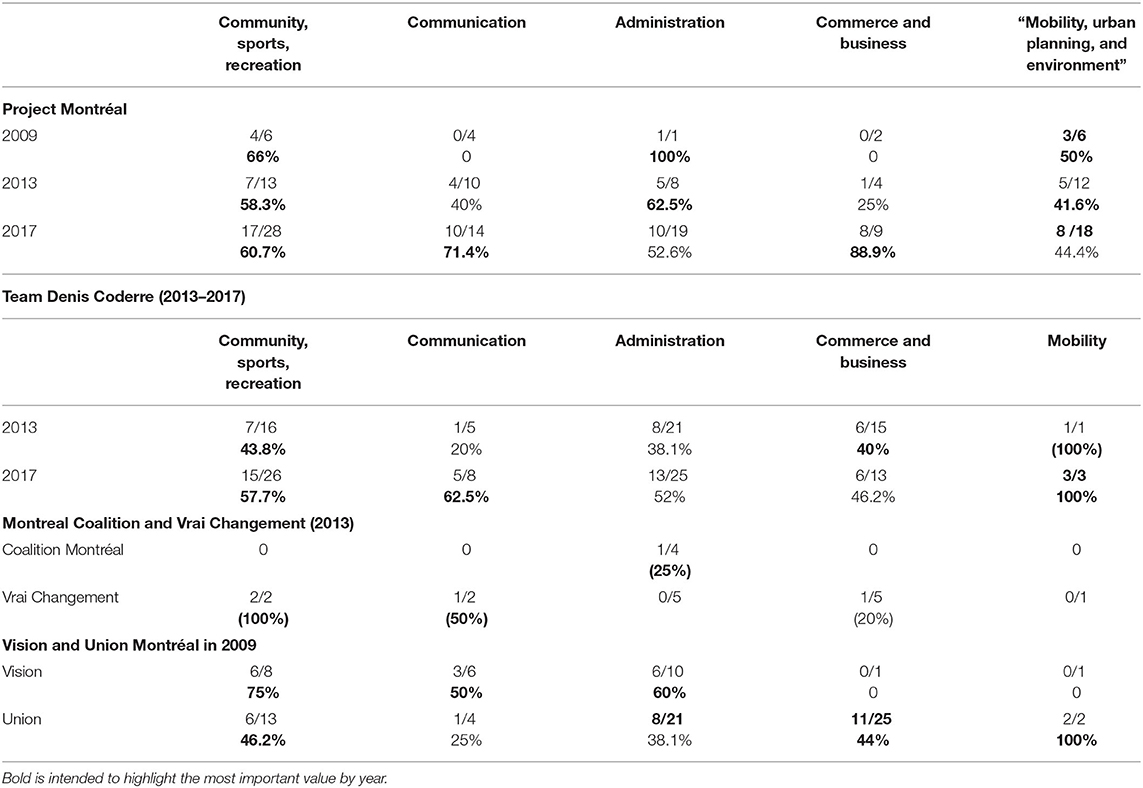

The analysis of the commitments of these parties' elected officials shows characteristics by party (Table 1). In 2009, the winning party, Union Montréal, was composed of elected officials who worked in the areas of commerce and administration. The fields of community, sports and recreation (13 out of 68 elected officials), communication (4 out of 68 elected officials) and “mobility, urban planning, and environment” (2 out of 68 elected officials) remain minority profiles. At the same time, Vision Montréal was composed of elected officials who had previous experience in administration (10/19) and community involvement, sports, and recreation (8/19), followed by the field of communication (6/19). Finally, the elected officials of Projet Montréal have experience in the field of “mobility, urban planning and environment” (6/14), in the field of community involvement, sports and recreation (6/14) and communication (4/14). For this party, the fields of commerce and administration remain in the minority. Since its electoral breakthrough, Projet Montréal has displayed a distinction in the profile of its elected officials due to the greater proportion of commitments in the field of “mobility, urban planning and environment” compared to the other parties. When considering all parties combined, it is the experience in administration that is dominant in the profiles of elected officials.

This distinction remains in the next election in 2013. Five parties competed for the mayor's office: Équipe Denis Coderre, Vrai Changement, Coalition Montréal, and Projet Montréal. The elected officials of Équipe Denis Coderre had a profile strong in administration (21/39), followed by community involvement, sports, and leisure (16/39) and commerce (15/39). Vrai Changement follows a similar pattern, with profiles split between administration (5/8) and commerce (5/8). For these two parties, the field of “mobility, urban planning, and environment” is hardly present among the experiences of their elected officials, only one elected official for each party. Coalition Montréal has a similar profile, featuring elected officials with experience in the field of administration, yet none from the field of “mobility, urban planning and environment.” For Projet Montréal, in 2013, the majority profile is that of elected officials with experience in the community, sports and recreation field (13/28), followed closely by “mobility, urban planning and environment” (12/28), and finally by administration (8/28). Projet Montréal has maintained the specificity of certain profiles in the field of “mobility, urban planning, and environment” compared to the other parties. All parties combined, it is still the field of administration, followed closely by the community field, which marks the career paths of councilors.

In 2017, three parties competed on the electoral scene: Équipe Denis Coderre, Coalition Montréal, and Projet Montréal. Équipe Denis Coderre was composed of elected officials with a background in community, sports and recreation (26/38), followed closely by administration. Although the number of elected officials with experience in “mobility, urban planning, and environment” had tripled, from one to three, this field was still underrepresented. At Projet Montréal, the majority of elected officials were active in the community, sports and recreation field (27/51), followed by the administration field (19/51) and the “mobility, urban planning and environment” field (18/51). Projet Montréal has thus maintained its specificity, although the share of experience in the field of administration is close to that in the field of “mobility, urban planning and environment.” All parties combined, elected officials' experience prevails in the field of community, sports and recreation, as well as in commerce. We will not examine Coalition Montréal because of its low participation in the election (1.26% of votes, only one elected official).

This first table offers a glimpse of the first distinctions between the formations and shows how Projet Montréal is distinct in the field of “mobility, urban planning, and environment.”

Analysis by gender reveals more specific characteristics (see Table A1 in Appendix). In 2009, the number of women elected remained low compared to the number of elected officials. Only Vision Montréal came close to parity (9 women out of 19 elected), while Union Montréal elected 26 women out of 68 and Projet Montréal elected 5 women out of 14. Experience in the field of “mobility, urban planning and environment” comes primarily from women, both for Union Montréal (3 out of 4 elected officials were women) and for Projet Montréal (3 out of 6 elected officials were women). However, since the number of women is limited, this greatly limits the weight of this observation.

In 2013, the number of women among elected officials was 15 out of 38 for Équipe Denis Coderre, 2 out of 8 for Vrai Changement, 1 out of 4 for Montréal Coalition, and 12 out of 28 for Projet Montréal, whereby Projet Montréal became the party that came closest to achieving parity. The backgrounds of the women of Équipe Denis Coderre resemble those of all elected officials, in other words, the average, although they tend to be, if anything, slightly more involved in community, sports and recreation, and in business, than in administration. The background of women in Projet Montréal is primarily in the areas of administration, community, sports and recreation, “mobility, urban planning, and environment,” and finally, communication. This picture does not quite reflect the average profile of all elected officials, where the field of administration figures only marginally among women's areas of involvement. One of the six elected officials of Coalition Montréal was a woman, who shows experience in administration similar to the other elected officials.

In 2017, Équipe Denis Coderre had 18 women among its 38 elected officials, and Projet Montréal 27 out of 51. The majority of Équipe Denis Coderre's elected women had experience in communications, community, and administration. It is important to note that, for this party, the only elected officials with experience in the field of “mobility, urban planning, and environment” were women. On the Projet Montréal side, women were mostly involved in commerce, followed by communications, community, administration and, finally, the “mobility, urban planning, and environment.”

These descriptions show that women do not have the same commitments or backgrounds as men. While these differences are sometimes due to the smaller number of women elected, the field of “mobility, urban planning, and environment” highlights some characteristics: both within Union Montréal and Équipe Denis Coderre, the experiences in this field are brought by women, while within Projet Montréal, during the last three elections, the commitments in this field were more diversified in terms of gender.

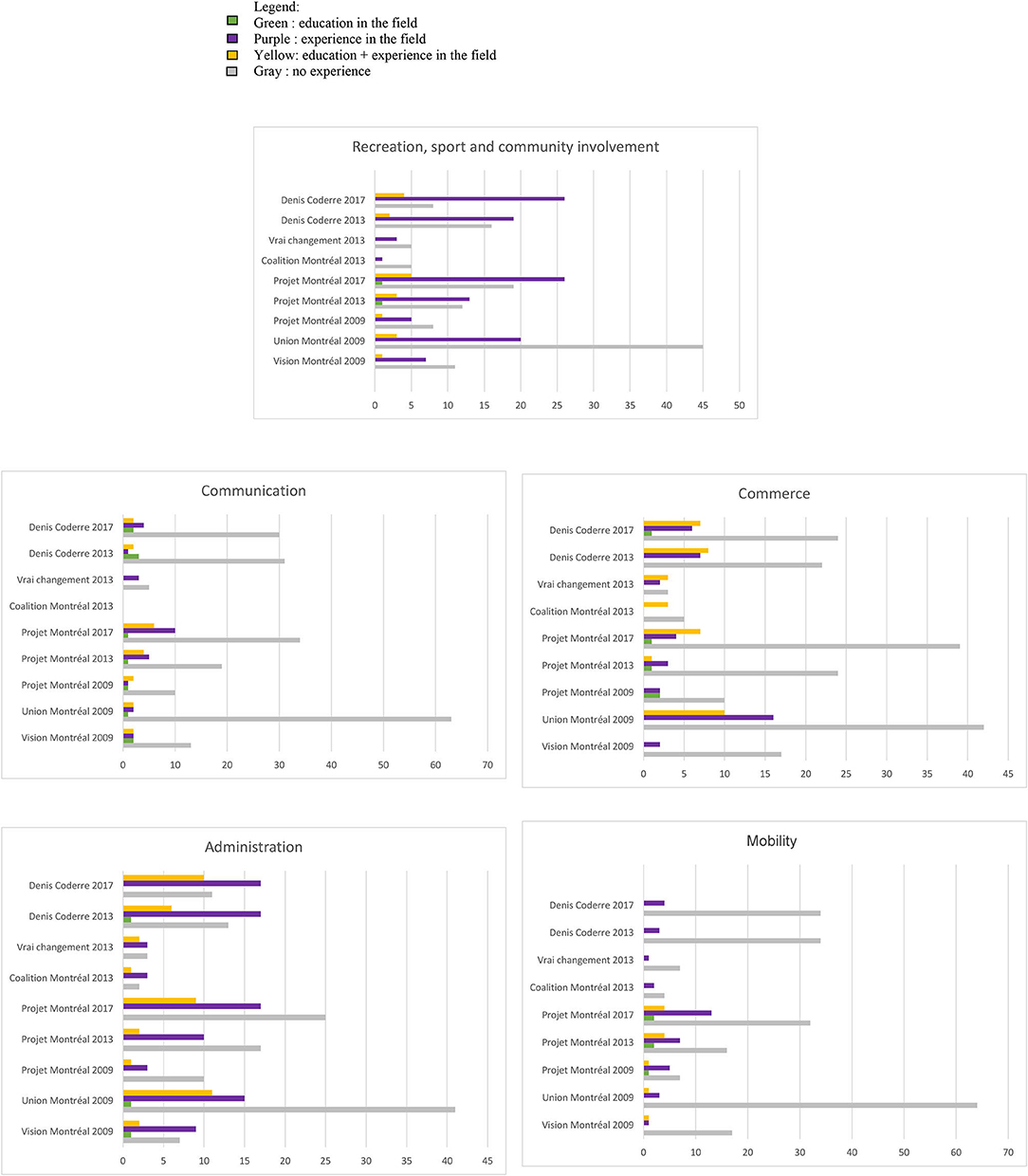

After this initial portrait, we looked at the nature of the commitments by distinguishing between four categories: (1) no experience (gray); (2) experience in the category (purple); (3) training in the category (green); (4) training and experience in the category (yellow). Figure 1 shows the results.

Figure 1. Commitments of elected officials according to party between 2009 and 2017. Green: education in the field. Purple: experience in the field. Yellow: education + experience in the field. Gray: no experience.

Over all the electoral years, several findings emerge. First, Projet Montréal was the political party with the greatest variety of profiles. Indeed, apart from the field of administration, Projet Montréal has elected officials with (a) university training in the field, (b) experience in the field, (c) training and experience in the field, or (d) no experience. This distinguishes the party from the other parties, where these four profiles are less consistently found. Second, more specifically, Projet Montréal has elected officials with training in all fields except administration. It is to be noted that in the other parties, elected officials tend not to hold a university degree in the field, except in the field of communications, for which elected officials are more likely to have a university background, regardless of the party. Third, Projet Montréal clearly stands out in the area of mobility: it is the only party that has elected officials with (a) training in the field, (b) experience in the field, or (c) training and experience in the field. The teams of the other parties do not have the same variety or quantity of profiles than Projet Montréal. We also note that in the case of Projet Montréal, this characteristic is visible as early as 2009 and continues until 2017.

On the other hand, the analysis by field also allows us to see the similarities of the profiles. The field of recreation, sports and community, for example, shows no differences between the political parties. The field of communications, for its part, does present all four types of profiles across all parties, with the exception of Vrai Changement and Coalition Montréal. In the field of administration, Équipe Denis Coderre, and Union Montréal stand out as the only parties to have elected officials with all four profiles, while the other parties lack elected officials with university education in this field. The field of “mobility, urban planning and environment” distinguishes Projet Montréal from the other parties.

The Profiles for the Field of “Mobility, Urban Planning, and Environment”

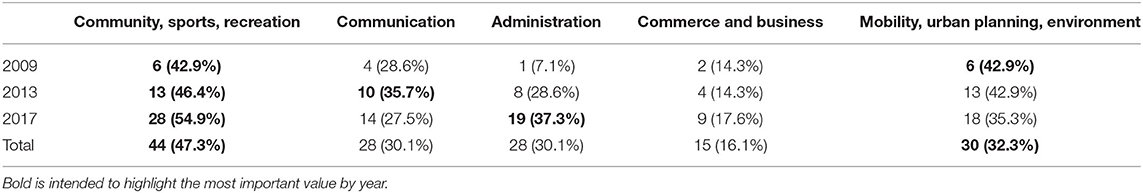

A look at the commitments of Projet Montréal's elected officials over the last three elections shows that the distinctive aspect of the profiles of Projet Montréal's elected officials, namely, their commitments to “mobility, urban planning, and environment” has remained stable over the years (Table 2). Indeed, about one third of elected officials have a background in this field. In order to better understand these paths that characterize Projet Montréal, we will, in the following, discuss certain important trends and figures regarding this topic for the party.

From 2009 to 2017, three basic tendencies can be noted in the types of experiences and commitments of Projet Montréal's elected officials with a profile in “mobility, urban planning, and environment.” These tendencies are presented with data drawn from the database on the profiles of elected officials presented above. Moreover, each tendency is, in addition, exemplified with the more detailed background of one leading elected official of Projet Montréal. The tendencies are as follows. First, the party has, persistently over time, a large share of elected officials with a university education in this field. This gives the party its image of expertise that was associated, in the early years, with its leader Richard Bergeron. Secondly, the importance of volunteer and activist activity has increased over time, in 2013 on mobility issues and in 2017 in social affairs, accounting for 70% of the elected officials with volunteering activities in these fields in both of these periods. In 2013, these commitments were presented as particularly related to the themes of traffic calming and opposition to the increase of highway infrastructure in urban areas. Between 2009 and 2013, Projet Montréal was quite involved in public debates concerning these issues, and some members participating in these debates were then elected as officials in 2013. Luc Ferrandez was one of the key figures on this topic, while being represented as a polarizing personality by the media. Other leading elected officials were, or are, more nuanced, such as François Croteau, who has been increasingly prominent since 2013. Finally, the 2017 elections show a strengthening in Projet Montréal's profile in the field of community, sports, and recreation, which is also reflected in the way it is increasingly inclined to approach mobility, introducing a greater social perspective.

In 2009, across all parties, there were few elected officials with a background in “mobility, urban planning, or environment.” Two-thirds of them, 6 out of 9, belonged to Projet Montréal. Three of them had a university education in this field, either just completed or in progress. These elected officials aligned themselves with the profile of their leader, Richard Bergeron, who presented himself as an intellectual and expert in sustainable urbanism and looked back on 15 years of research and planning studies on urbanism and mobility. Two other candidates had backgrounds directly in mobility and sustainable urban development, and yet another two were trained in social sciences and have held environmental research positions in other organizations. In total, 5 of the 6 elected officials of Projet Montréal had a graduate-level education, which set them apart from the elected officials of other parties. This portrait of expertise continued in 2013, when additional graduates in urban planning or architecture were added to the team. The party thus maintained its quasi-monopoly on these topics, such that, in 2013, of the 16 elected officials having such a profile, from all parties combined, 13 came from Projet Montréal alone.

The flagship candidates of Projet Montréal are mostly experts on this issue, but have different positions regarding the speed with which they wish to implement their measures, and their scope. Richard Bergeron, their leader, has written books strongly positioned against the design of the city for the automobile. As party leader, however, he defends primarily a vision of sustainable urban planning, user-friendly public spaces and public transportation, without being confrontational, even while being opposed to highway projects. His expertise has been recognized by the leaders of the other parties and mayors of Montreal on two occasions. In 2009, Mayor Gérald Tremblay invited him to serve as a member of the City of Montréal's executive committee, in charge of urban planning. In 2014, he left the Projet Montréal party to sit as an independent and accepted the offer of Mayor Denis Coderre to sit on the executive committee, likewise in charge of urban planning.

In contrast, Luc Ferrandez quickly became, following his election in 2009, one of the best known and most publicized figures of Projet Montreal. Mayor of the Plateau-Mont-Royal borough, he was particularly known for his outspokenness and his measures to reduce car traffic, considered “radical” in the media. Ferrandez also benefited from the fact that Projet Montréal held all the seats in the borough (representing half of all Projet Montréal candidates elected in 2009), thus giving him room to advance the party's promises in this area, which became a laboratory for traffic calming in Montreal. Luc Ferrandez was little known publicly prior to his nomination as borough mayor of Plateau Mont-Royal in 2009, although he had been active on mobility and planning issues for some years. He earned a doctorate degree in economic policy and has conducted research in a laboratory on environmental issues in Paris, at the CNRS. He then worked for 10 years in management and change management, as well as in strategic planning. He was involved in the Association des citoyens et citoyennes du Plateau Mont-Royal, publishing an opinion letter in 2001 entitled “Les automobilistes et les quartiers qu'ils traversent” (Motorists and the neighborhoods they pass through Ferrandez, 2001), and defending TOD (transit-oriented development) at the Commission de consultation sur l'amélioration de la mobilité entre Montréal et la Rive Sud (Consultation commission on improving mobility between Montreal and the South Shore). He was also involved in the debate on the redevelopment of Notre-Dame Street in the early 2000s, as spokesperson for Association Habitat Montréal. At the time, he emphasized the importance for the city of Montreal to “get out of the ‘transportation' straitjacket in which it let itself be trapped by the Ministry regarding the Notre-Dame Street file” (our translation), in terms of highway transportation, as opposed to a vision of sustainable mobility and an “urban boulevard” better integrated into the neighborhood. On the Plateau-Mont-Royal, he has been involved in traffic-calming issues, which later became one of his campaign themes (Gagnon et al., 2002). He has always defined himself as a doer, and said, upon being elected in 2009: “I'm happy to have put an end to the ‘labrecquism,' which consists of a lot of talk and no action” (Le Hirez, 2009, our translation). His predecessor, from Union Montréal, had advocated similar goals of reducing the role of the automobile and promoting active transportation, albeit with a more measured approach, according to the Projet Montréal candidates elected in Plateau-Mont-Royal in 2009.

From Ferrandez's first weeks in office in 2009, controversies erupted. Snow management was the first, with his team proposing to slow down snow removal to reduce financial and environmental costs. This was followed by an increase in car parking fees, highly denounced by merchants, in 2010; and thereafter by traffic-calming measures implemented in 2010 and 2011, following the death of a Laurier School student. Each of these interventions were highly publicized (Van Neste, 2014). In the borough, his party is also known for the extensive redesigning of streets, the greening of sidewalks and the redesign of parks, plazas, and public spaces. Despite the controversies, Luc Ferrandez was re-elected in 2013 with 51.3% of the vote, then in 2017 with 65.7% of the vote. He became interim leader of Projet Montréal following the departure of Richard Bergeron, namely from October 2014 to November 2016, when Valérie Plante became leader. In 2017, he was in charge of the portfolio on large parks in the City's executive committee. With these responsibilities, he continued to carry out bold actions, canceling, for example, a big real estate project in the West Island to make room for the creation of a large park protecting wetlands on this territory, in the name of action against climate change. However, he resigned on May 14, 2019, stating he lamented that the party was not doing enough to address the climate emergency (Gosselin, 2019).

While Ferrandez was the most polarizing of Projet Montréal's elected officials, and having received significant media attention, he does represent a portion of Projet Montréal's elected officials who have a history of involvement in citizens' associations or non-profit organizations working for traffic calming in Montreal neighborhoods or that oppose the expansion of highway infrastructures. Involvement in these issues is also highlighted in the biographies of Projet Montréal candidates in the 2013 elections. Seven of the thirteen elected candidates of Projet Montréal with a mobility and environment profile had highlighted their involvement in associations regarding these themes. These issues had been the subject of social mobilizations starting in 2005 and intensifying in 2010, until 2013. A total of 165 citizen and membership-based organizations developed traffic-calming projects in Montreal during these years, giving rise to two large coalitions that opposed highway projects and in which Projet Montréal and some of its future elected members participated, along with environmental groups and neighborhood residents' associations (Van Neste and Sénécal, 2015).

Outside the Plateau-Mont-Royal, the party's elected officials show more caution and restraint in their positionings, especially in relation to the automobile, while keeping the course toward a common vision of sustainable urban development. The second stronghold of Projet Montréal is the borough of Rosemont-La Petite-Patrie, with two elected officials in 2009 and five in 2013. François Croteau has been borough mayor of Rosemont-La Petite-Patrie since 2009. He left the ranks of Vision Montréal in 2011 due to “their lack of a clear vision,” especially in urban planning, to join Projet Montréal (Benessaieh, 2011). In the media, François Croteau is presented as more moderate than his colleague from Plateau-Mont-Royal. Nevertheless, as early as 2010, he took a stand for the protection of natural environments such as the Meadowbrook golf course, alongside Luc Ferrandez, and against the Turcot Interchange project as put forward by the Ministère des Transports in 2011. François Croteau has a PhD in urban governance, as well as some political experience, having been the campaign assistant of a Parti Québecois MP at the provincial level. He was involved in the student and sovereigntist movement during his studies. As borough mayor, he particularly stands out for his bylaw requiring the transition to white roofs in his borough, to fight against heat islands. The bylaw created some debate, but did not receive the same media coverage as Ferrandez on the Plateau-Mont-Royal. Overall, his approach stands out as conciliatory. In June 2011, Croteau and his team proposed the pedestrianization of Masson Street for summer weekends, one of his election promises. When the Société de développement commercial spoke out against this undertaking, he expressed his disappointment but nevertheless respected their decision and did not go ahead with the project (Guthrie, 2011). In the years that followed, Croteau became known for his proactive policies for greening and urban agriculture in the borough, encouraging citizen initiatives. Following his re-election in 2017, he engaged his borough in the first ecological transition plan in Montreal, developed in collaboration with researchers.

In 2017, the themes of “mobility, urban planning, and environment” continued to have a prominent place in the profiles of Projet Montréal's elected officials, with 18 of 51 elected officials (35%) showing a background experience in this area, even if that percentage was somewhat lower than it was before. The four newly elected officials with a strong profile in this field had been involved in local associations and mobilizations for the protection of parks and green spaces (and not for traffic calming, as in the previous election). Moreover, many of the re-elected officials had been particularly active on the borough or city councils in matters of mobility or sustainable urbanism in the previous 4 years. The share of Projet Montréal elected officials with a background in these themes remains high (9/18).

Another trend in the experience of Projet Montreal elected officials, which began to emerge in 2013, grew even stronger in 2017: previous commitments in the community, sports and recreation field, tended to increase, from 43% in 2009 and 46% in 2013 to 55% in 2017. In addition to volunteering to protect and enhance local community services and greening, visible in 2009 and 2013, a growing number of elected officials with this profile of community commitments from Projet Montréal cite in in their biography experiences of advocating for housing affordability, women rights and safety as well as being involved in unions or in cultural affairs, i.e., in social issues. This trend is particularly represented in the profile of their leader.

Valérie Plante was a member of Projet Montréal since 2007 and elected since 2013. Having become mayor of Montreal in 2017, she first campaigned for party leader in 2016 with a focus on measures to reduce social inequalities. Through her professional and volunteer experiences, she represents this rise in importance of community and social issues in the profile of the party's elected officials as well as the party's orientations. Her biography indicates that her professional and volunteer experiences (in the cultural, community, and union worlds, notably concerning the participation of women in politics) have inspired her interest in social justice and the fight against poverty. Valérie Plante also continues in the tradition of her predecessors and of what distinguishes the party, with mobility at the heart of three of the five priorities announced in her electoral program (Projet Montréal, 2017). This platform also succeeded in presenting mobility as an issue that concerns all Montrealers, for example, by emphasizing the need for a better quality of life in the neighborhoods, greater efficiency of road renovation projects, less traffic congestion, and an improved and expanded subway system (including the flagship idea of a new “pink line” that would, at the same time, underscore Valérie Plante's feminist agenda). In this way, Plante also gives a human and social face to the theme of mobility, thereby distinguishing herself from Richard Bergeron, a technocratic intellectual, and Luc Ferrandez, who was a polarizing figure. Apart from Valérie Plante, the party also saw the integration of several new members with a profile of involvement in the community, social, sports, and recreation worlds, which likewise reinforced the social embeddedness of the party's platform regarding mobility.

Commitments That Give Color to the Party and to the Function of the Elected Official

This exploratory look at the profiles of elected municipal officials leads to several findings. In general, and across all parties, the experiences and commitments of municipal elected officials in 2009 are dominated by the field of administration, followed by commerce and business. In 2013, commitments in the field of administration remain in the majority, followed closely by the fields of community, sports and recreation, and commerce and business. In 2017, these three fields remain central, although the community, sports and recreation field leads, followed by commerce and business, and administration. In the face of this overall picture, the profiles of Projet Montréal elected officials stand out because of their experience in the areas of “mobility, urban planning, and environment” in all election years.

This distinction in the profiles of Projet Montréal's elected officials is not surprising and is in keeping with the party's philosophy, as it was conceived at the time of its founding. Overall, however, it can be argued that the party's specificity is due largely to its steady and consistent commitments in the field of “mobility, urban planning, and environment” over time. During the last three elections, the profiles in this field have even increased among the City's other main parties—a probable response to the growing importance of this theme in large cities. However, proportionally, the share of elected officials with this profile has remained almost the same in Projet Montréal. Even more interesting is the evolution of the profile of these elected officials within Projet Montréal: while the first elected officials had, like their leader, an education in the field of “mobility, urban planning, or environment” in 2013 and 2017, an increasing number of elected officials also have an activist and volunteer profile in this field. Finally, the political party also trains these elected officials, since elected officials with no experience in the field need one, once elected.

These findings resonate with the ideological positioning of the party. Projet Montréal was long considered a centrist party and its leader's figure of expert a potential weak point. “Richard's technicist, somewhat cerebral, sometimes haughty style and the intellectual and non-conformist arguments of the platform put off another part of the population that only wants a ‘good mayor' who is affable and does not disturb the order of things” (Beaudet, 2019, p. 206, our translation). At the time of her election to the party leadership in 2016, Valérie Plante's left-wing positioning was seen by the majority of Projet Montréal councilors as a potential weakness: “The moderates are disappointed and see a decrease in their electoral chances. But the more left-wing circles of the party and its supporters, close to Québec solidaire and the New Democratic Party (NDP), environmentalist, community, feminist, and union circles, are delighted” (Beaudet, 2019, p. 208, our translation). Nevertheless, in their analysis of the distribution of votes in Montreal's 2017 election (Breux et al., in press) shows that Valérie Plante is associated with the left in the eyes of voters and that she owes her election—among other things—to two phenomena: “In Montreal, right-wing voters were more likely to vote for Denis Coderre and left-wing voters more likely to vote for Valérie Plante. The victory of Valérie Plante can be explained, at least in part, by the fact that she was perceived more at the center of the political spectrum than Denis Coderre. As a result, her positioning was more in line with that of Montrealers. In addition, she was able to attract the vote of the left-most voters, while Denis Coderre was not able to do the same with the most right-wing voters” (in press). This analysis also seems to be reflected in the composition of the profiles of the party's elected officials and raises a series of questions: Did the activist profiles of some of the party's elected officials, particularly through their volunteer work in the field of mobility, also help to attract votes from the left? Or, did the higher proportion of elected officials with experience in the field of administration help to attract voters from the center, thus projecting a vision more in line with the profiles of previous elections?

This first set of findings—in broad strokes—raises many questions: To what extent does the background of elected officials influence the way they carry out their duties? What skills do they use? To what extent do these experiences, especially activism, contribute to a certain vision of the city that manifests in the party? These are all questions that go beyond the scope of this exploratory analysis, but which invite us to delve into the way that elected municipal officials see their functions and their careers (Egner et al., 2013). Moreover, our analysis excluded the potential weight of prior political experience. Finally, our survey also interrogates the conditions of entry into municipal politics. In Valerie Plante's fictionalized account of her entry into politics, published as a comic book, the current mayor notes that as soon as she became a candidate, she had to raise $5,000 to launch her campaign. The heroine of the comic strip exclaims, “I think I understand why most politicians come from the business world or are lawyers” (Plante and Côté-Lacroix, 2020, p. 35, our translation). Consequently, it is fair to assume that the conditions of entry into politics remain to be explored in the Montreal case. Finally, the role of mobility in party politics and electoral choices in cities has been little studied in North America (Walks, 2014). Yet, Couture and Breux (2021) have clearly shown that transportation and mobility issues can be critical to the choices voters make at the ballot box at the municipal level. More research needs to be done to explore these links.

In our view, the answer to these various questions lies in opening up a specific research project on municipal political parties and their elected representatives, and on the place that certain themes—such as mobility—take in a context that was previously considered to be by and large apolitical and of a managerial nature. While the data we've collected in this article are the first steps in this direction, they need to be enriched and expanded by conducting semi-structured interviews with elected officials who are affiliated with a municipal political party. On the one hand, such interviews would allow identifying in greater detail the knowledge which elected officials intend or believe to be mobilizing over the course of their political mandate. As part of that, the interviews would reveal how elected officials' conceive of their mission and duty when they have a background or experience that is aligned with the party's identity and, more broadly, how a party's identity is perceived and experienced within the party.

On the other hand, such interviews could fill the gaps of our present research by highlighting the position of elected officials within the governance of the party, particularly with regard to their experience and training in certain fields. In addition, the interviews could make it possible to question the formal and informal commitments which these elected officials made with other political parties at higher levels, and thus help to identify potential links between these formations. Finally, access to this information would also provide new insights into the characterization of the identity of certain municipal parties. Such information could provide a better understanding of the reality—still poorly understood—of the municipal political parties and their dynamics at work within government while also initiating the systematic collection of such data.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

SB and SLVN contributed to conception and design of the study. SLVN organized the database. SB wrote the first draft of the manuscript, except for the section titled The Profiles for the Field of ‘Mobility, Urban Planning, and Environment', which was written by SLVN. Both authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was funded from SSHRC 430-2018-00958, 435-2019-0920, and INRS.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pierre-Luc Baril for his work on the database.

Footnotes

1. ^For readers unfamiliar with the electoral context in Montreal, elections in Quebec are held every 4 years. The mayor of the city is elected by direct universal suffrage by all citizens. The Montreal system is different from other systems in that it is the only city to have a borough mayor, elected by direct universal suffrage by the entire population of the borough. The City of Montréal has 19 boroughs and therefore 19 borough mayors. In two boroughs, city councilors are elected at the borough level. Each borough is then divided into districts. Each district has a city councilor (who sits on city council) and/or a borough councilor (who does not sit on the city council, but on the borough council).During the municipal election, each elector votes (1) for the city mayor, (2) for the borough mayor, and (3) for one or more councilors (either municipal or borough) depending on the demographic size of the borough. A voter has a minimum of three votes and a maximum of five. The City of Montréal's 65-member council is made up of the mayor, 18 borough mayors (the mayor of the city being the mayor of the borough of Ville-Marie), and 46 city councilors (available online at: https://election-montreal.qc.ca/userfiles/file/ElectionGenerale2017/fr/Document_Form/CadreElectoral_2017.pdf).

References

Beaudet, P. (2019). Les défis de Projet Montréal. Entretien avec Michel Camus. Nouveaux Cahiers du socialisme 22: 205–215.

Bherer, L., and Breux, S. (2012). L'apolitisme municipal. Bull. d'histoire Polit. 21, 170. doi: 10.7202/1011705ar

Breux, S., Couture, J., and Mévellec, A. (in press). “Does the left-right axis matter at the municipal level?” in Voting in Quebec Municipal Elections: A Tale of Two Cities, eds M. McGregor, É. Bélanger, and C. Anderson. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Collin, J.-P., Bherer, L., Breux, S., and Plourde, S. (2009). Le mode de scrutin proportionnel; à l'échelle municipale : réflexions et leçons tirées de l'examen du cas montréalais. Montreal, QC: INRS-UCS.

Couture, J., and Breux, S. (2021). A new tunnel effect? The impact of stress on vote choice. Front. Polit. Sci. 3, 589548. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.589548

Darvicje, M. S., Genieys, W., and Joana, J. (1995). Sociologie des élus régionaux du Languedoc-Roussillon et de Pays-de-Loire (II) Itinéraires et trajectoires. Pôle Sud. 74–100. doi: 10.3406/pole.1995.891

DeLeon, R. (1992), The urban antiregime. Progressive politics in San Francisco. Urban Affairs Q. 27, 555–579. doi: 10.1177/004208169202700404.

Egner, B., Sweeting, D., and Klok, P.-J., (eds.). (2013). Local Councillors in Europe. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-01857-3

Ferrandez, L. (2001, March 2). Les automobilistes et les quartiers qu'ils traversent. Le Devoir. Opinion Letter section.

Gagnon, F., Ferrandez, L., and Clermont, P. (2002). De la rue Notre-Dame au boulevard A-720 : Quel futur pour quel projet et quelle ville? VertigO—la revue électronique en sciences de l'environnement. Montréal: Université du Québec a Montréal. doi: 10.4000/vertigo.4158

Gosselin, J. (2019, 14 May). Luc Ferrandez annonce son départ de la vie politique. Montreal. La Presse.

Heinelt, H., Magnier, A., Cabria, M., and Reynaert, H., (eds.). (2018). Political Leaders and Changing Local Democracy: The European Mayor. ILIAS Series Governance and Public Management. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-67410-0

Henderson, J. (2013). Street Fight: The Politics of Mobility in San Francisco. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Jerome, V. (2014). Militants de l'autrement. Sociologie politique de l'engagement et des carrières militantes chez Les Verts. Paris: Université Paris 1- Panthéon Sorbonne.

Latendresse, A. (2013). Montréal, un chantier pour la gauche. Relations. 768, 22–23. https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/70212ac

Latendresse, A., and Frohn, W. (2011). “Fracture urbaine, legs institutionnel et nouvelles façons de faire : trois mots clés d'une lecture des élections municipales à Montréal,” in Les élections municipales au Québec : enjeux et Perspectives, eds S. Breux, and L, Bherer. (Quebec, QC: Presses de l'Université Laval), 85–122.

Le Hirez, C. (2009, November 5). Luc Ferrandez: “Cela fait peur”. Le Plateau. Montreal: Medias Transcontinental.

Mévellec, A. (2018). “Accountability and local politics: contextual barriers and cognitive variety,” in Accountability and Responsiveness at the Municipal Level: Views From Canada, eds. S. Breux, and J. Couture. (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press), 53–74.

Mévellec, A., and Tremblay, M. (2013). Les partis politiques municipaux: La “westminsterisation” des villes du Québec? Recherches Sociographiques 54, 325–347. doi: 10.7202/1018284ar

Mévellec, A., and Tremblay, M. (2016). Genre et professionnalisation de la politique municipale: un portrait des élues et élus du Québec. Québec, QC: Presses de l'Université du Québec. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt1f89sqh

Michon, S., and Ollion, É. (2018). Retour sur la professionnalisation politique. Revue de littérature critique et perspectives. Sociol. Travail. 60, 1706. doi: 10.4000/sdt.1706

Molotch, H. (1976). The city as growth machine: toward a political economy of place. Am. J. Sociol. 82, 309–322. doi: 10.1086/226311

Navarre, M. (2015). De la professionnalisation au désengagement: Les bifurcations dans les carrières politiques des élues en France. Politique Sociétés 33, 79–100. doi: 10.7202/1027941ar

Plante, V., and Côté-Lacroix, D. (2020). Simone Simoneau. Chronique d'une femme en politique. Montreal, QC: XYZ. Collection Quai n°5.

Projet Montréal (2017). Projet Montréal – Un choix pour l'avenir de Montréal – Plateforme 2017. Montreal.

Sancton, A. (2015). “The ‘training' of municipal councillors: professionalization in a mid-sized Canadian city,” in Former les élus : repenser la relation entre légitimité démocratique et expertise, Congrès annuel de la société française de science politique (Aix en Provence).

Ségas, S. (2021). Des tours dans la campagne : politiques de densification et coalition anticroissance à Rennes. Métropoles 28, 7989. doi: 10.4000/metropoles.7989

Simard, C. (2005). Qui nous gouverne au municipal : reproduction ou renouvellement? Polit. Sociétés 23, 135–158. doi: 10.7202/010887ar

Steyvers, K., and Verhelst, T. (2012). Between layman and professional? Political recruitment and career development of local councillors in a comparative perspective. Lex Localis 10, 1–17. doi: 10.4335/10.1.1-17

Van Neste, and S, L. (2014). Place-framing by coalitions for car alternatives: a comparison of Montreal and Rotterdam. The Hague Metropolitan Areas. (Thèse de doctorat en études urbaines), Institut national de recherche scientifique - Urbanisation, Culture et Société. Available online at: http://espace.inrs.ca/id/eprint/2649 (accessed February 11, 2022).

Van Neste, S. L., and Sénécal, G. (2015). Claiming rights to mobility through the right to inhabitance: discursive articulations from civic actors in Montreal. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 39, 218-233. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12215

Verhlest, T., Reynaert, H., and Steyvers, K. (2013). “Political recruitment and career development of local councillors in Europe,” in Local Councillors in Europe, Urban and Regional Research International, eds B. Egner D. Sweeting and P. J. Klok. (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden), 27–50. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-01857-3_2

Walks, A. (2014). The Urban Political Economy and Ecology of Automobility: Driving Cities, Driving Inequality, Driving Politics. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315766188

Appendix

Keywords: Projet Montréal, municipal political party, mobility, urban planning and environment, profile of elected officials, Québec (Canada)

Citation: Breux S and Van Neste SL (2022) Differentiated Profiles of Elected Officials in Montreal: A Specific Party Identity Around Mobility, Urban Planning, and Environment? Front. Polit. Sci. 4:745777. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.745777

Received: 22 July 2021; Accepted: 02 February 2022;

Published: 09 March 2022.

Edited by:

Régis Dandoy, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, EcuadorReviewed by:

Shannon Lane, Yeshiva University, United StatesSébastien Ségas, University of Rennes 2 – Upper Brittany, France

Copyright © 2022 Breux and Van Neste. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sandra Breux, c2FuZHJhLmJyZXV4QGlucnMuY2E=

Sandra Breux

Sandra Breux Sophie L. Van Neste

Sophie L. Van Neste