94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Polit. Sci., 21 March 2022

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.648061

This article is part of the Research TopicPolitical Misinformation in the Digital Age during a Pandemic: Partisanship, Propaganda, and Democratic Decision-makingView all 13 articles

As national and international health agencies rushed to respond to the global spread of a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2, commonly known as COVID-19), one challenge these organizations faced was the spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories about the virus. Troublingly, much of the misinformation was couched in racialized language, particularly regarding the source of the virus and responsibility for its spread, fostering the development of related conspiracy theories. Media coverage of these conspiracy theories, particularly early on in the pandemic, had negative impacts on individuals' engagement in protective behaviors and concern with the spread of COVID-19. From extant work, racial resentment and white identity have been shown to be deeply woven into the fabric of contemporary American politics, affecting perceptions of public opinion even after accounting for social and political identities. While racial attitudes have been less studied in relation to conspiracy theory belief, we expect racial resentment and white identity to affect compliance with public health behaviors and COVID-19 conspiracy theory belief. Using observational and experimental survey data (N = 1,045), quota-sampled through Lucid Theorem (LT) in the spring of 2020, we demonstrate that framing the virus in racialized language alters endorsement of COVID-19 conspiracy theories, contingent upon levels of racial resentment and white identity and find that higher levels of conspiracy theory belief decreased compliance with preventative measures.

Starting early in 2020, the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2, commonly known as COVID-19) rapidly spread across the globe, coupled by a wildfire of related misinformation and conspiracy theories. Media coverage of these conspiracy theories, particularly early on in the pandemic, had negative impacts on individuals' concern with the spread of COVID-19 (Motta et al., 2020) and engagement in protective behaviors (Chen and Farhart, 2020). Delayed responses, denials of pandemic severity, and misinformation and conspiracy theories about COVID-19 exacerbated the spread of the virus and slowed pandemic response, particularly in the U.S. (e.g., Abutaleb et al., 2020). As such, scholars turned to investigate why Americans might believe in coronavirus conspiracy theories, and how that conspiracy theory belief might further affect engagement with protective health behaviors.

Further, scholars have established that conspiracy theory belief is wide-spread with social and political consequences, globally traversing demographic, attitudinal, and political differences (e.g., Zonis and Joseph, 1994; Abalakina-Paap et al., 1999; Byford and Billig, 2001; Jolley and Douglas, 2014; Oliver and Wood, 2014; Uscinski and Parent, 2014). The causes and consequences of conspiracy theory belief include various psychological, political, and situational factors. Specifically, van Prooijen and Douglas (2018) emphasize that conspiracy theory belief is consequential for health and safety, universal and widespread across historical and cultural contexts, emotional as conspiracy theory beliefs are often disconnected from deep, rational considerations, and lastly, socially tied to psychological motivations related to strong intergroup identity and intergroup conflict. Here, we are particularly interested in the first and fourth principles associated with COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs.

Uscinski et al. (2020) demonstrate that beliefs in COVID-19 conspiracy theories are most strongly predicted by individuals' rejection of expert information and official accounts of major events (denialism), a psychological predisposition to view major events as the product of conspiracy theories (conspiracy thinking), and political motivated reasoning (individuals' motivation to protect their partisan or ideological worldview). Further, Miller (2020) illustrates that the coronavirus pandemic has created a “perfect storm” to activate all three dimensions. Importantly, Miller (2020) demonstrates that rather than an entirely monological approach, e.g., Goertzel (1994), individual and situational factors interact to amplify CT beliefs to a greater extent than any single factor does on its own. This has potential consequences for impacting protective health behaviors, such as those recommended by the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as well as general pandemic-related behaviors. Oliver and Wood (2014) established that medical conspiracy theory beliefs are related to health behaviors. Consequently, some specific COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs had greater consequences for pandemic-related behaviors and vaccine intentions (Earnshaw et al., 2020; Imhoff and Lamberty, 2020; Kroke and Ruthig, 2021).

Troublingly, much of the misinformation and COVID-19 conspiracy theories have been couched in racialized language, particularly related to the source of the virus and responsibility for its spread. The pandemic began at a time when Donald Trump found political success from appealing to white racial grievances and nostalgia, while also scapegoating foreigners and immigrants (Sides et al., 2018; Jardina, 2019; Reny et al., 2019a,b; Reny and Barreto, 2020). The racialization of COVID-19 was a result of conservative political elites framing the coronavirus as a Chinese or Asian threat, which exacerbated anti-Asian attitudes associated with both concern about the disease and with xenophobic behaviors and policy preferences (Reny and Barreto, 2020). Historically, pandemics and the spread of infectious disease have been associated with heightened levels of prejudice, racial intolerance and xenophobia (Schaller and Neuberg, 2012; Kim et al., 2016; Elias et al., 2021). Relatedly, conspiracy theories often present an intergroup conflict such that a hostile outgroup, often those in powerful positions believed to be conspirators, is viewed as deceptive and threatening to a particular ingroup (e.g., van Prooijen and van Lange, 2014; van Prooijen and Douglas, 2018). As such, many of the COVID-19 conspiracy theories presented a direct ingroup threat to not only nationality but also those in racially dominant positions, from foreign entities, particularly China as the conspiratorial outside force. The pandemic may also be more threatening to those who hold a deeper anti-vax identity (Motta et al., 2021). As such, this project seeks to extend these works to examine the interactive effects of racialized framing and identity threat on engagement with protective health behaviors and COVID-19 conspiracy theory belief.

We expect the racialized framing of some of the COVID-19 conspiracy theories to activate racial attitudes and racial identities, principally racial resentment and white identity for white populations as the foreign, external threats proposed from many COVID-19 conspiracy theories could be threatening to those in racially dominant positions. From extant work, we know that racial resentment and white identity are deeply woven into the fabric of contemporary American politics and scholars have consistently shown that racial attitudes affect perceptions of public opinion even after accounting for social identities such as partisanship and political ideology (Henderson and Hillygus, 2011; Knuckey, 2011; Filindra and Kaplan, 2016; Benegal, 2018; Jardina and Traugott, 2019).

We expect, however, that white identity and racial resentment function as two distinct forces in the realm of conspiracy theories. Scholars examining racial animus toward Black and African American people often focus on attitudes that combine assessments of negative stereotypes about work ethic and racial bias. Racial resentment is often utilized and understood to be the combination of anti-Black affect and the belief that Black people do not engage with traditional American values associated with protestant work ethic (Kinder and Sanders, 1996; Sears and Henry, 2005)1. These racial attitudes are easily primed by the social and political environment (Gilens, 1999; Tesler, 2012, 2015; Sheagley et al., 2017) and thus, should play a role in COVID-19 conspiracy endorsement when the theory is explicitly racialized2. Additionally, to the extent that protective health behaviors are seen as a tacit endorsement of the severity of the virus, individuals high in racial resentment may be less likely to engage in protective behaviors to avoid dissonance.

White identity, on the other hand, rather than serving as a proxy for racial attitudes among White people, acts as a distinct identity-protecting attitude (Jardina, 2019). Thus, individuals high in white identity are not simply expressing a dislike of racial out-groups, but are instead demonstrating strong in-group identity (Tajfel et al., 1979; Brewer, 1999). Although Jardina (2019) does not examine conspiratorial beliefs, her work suggests that events that are perceived as identity threatening lead to support for policies framed to alleviate that threat. Similar to the way that Jardina (2019) illustrates that mass opposition to immigration, to government outsourcing, and to trade policies are a function of white identity, we examine the threat to identity induced from the coronavirus pandemic. Unlike racial animus, we believe the pandemic itself serves as the identity threat, and thus white identity should positively predict conspiracy endorsement regardless of racial frames. Furthermore, we expect those high in white identity to seek to protect their in-group through behavior as well, resulting in greater engagement in protective health behaviors.

Thus, we expect both in-group affinity (white identity) and out-group hostility (racial resentment) to affect protective health behaviors and conspiracy theory belief during the early racialized coronavirus pandemic. As more politicians adopt racially charged rhetoric around whiteness (rather than anti-black, anti-Hispanic, anti-Muslim, etc. rhetoric) to avoid charges of overt racism (Mendelberg, 2001; Haney López, 2015), we expect this rhetoric to cue white identity more strongly than anti-black affect or racial resentment. While we expect those high in white identity to endorse conspiracy theories writ large as a psychological defense against identity threat, we believe instances of racialization are likely to be conditional on the framing of the conspiracy theory. We also expect racial resentment and white identity to exert countervailing effects on protective health behaviors.

In sum, the current project tests the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (Main Effects): Individuals higher in white identity will be more likely to endorse conspiracy theories that individuals lower in white identity.

Hypothesis 2 (Experimental Effects): When the framing of a coronavirus conspiracy theory is racialized with an out-group target, racial resentment will have a positive impact on the endorsement of the conspiracy theory. When the framing of a conspiracy theory is racialized with an in-group target, racial resentment will have a negative impact on the endorsement of the conspiracy theory. White identity will have a positive impact on conspiracy theory endorsement, regardless of experimental frame.

Hypothesis 3a (Protective Behaviors): Above and beyond conspiracy belief, conspiratorial thinking and political identities, explicitly negative racialized perceptions of the coronavirus and racial resentment will have a negative effect on individuals' engagement with protective health behaviors in response to the pandemic;

Hypothesis 3b (Protective Behaviors): Above and beyond conspiracy belief, conspiratorial thinking and political identities, white identity will have a positive effect on engagement with protective health behaviors.

This study utilized original observational data and a series of split-ballot survey experiments from a large (N = 1,045), non-probability but quota-sampled online survey of Americans conducted through Lucid Theorem (LT)3. LT matches samples to Census demographics to approximate national representativeness. The study was fielded May 25–26, 2020. While analyses are conducted only on white respondents (N = 727), the broad demographics of our full sample, the question wording experiment cell sizes, and a correlation matrix of our main variables of interest are presented in the Supplementary Materials4.

Our first set of dependent variables focuses on three specifically racialized conspiracy theories related to COVID-19. We selected these prominent COVID-19 conspiracy theories from Miller (2020). Each conspiracy theory featured a set of experimental manipulations designed to alter the source behind the supposed conspiracy. The first question asks how likely it is that one of three groups [U.S. Government, China (racialized condition), the WHO] withheld information to make the pandemic appear less serious. The second asks how likely it is that one of three groups [U.S. Military, China (racialized condition), a foreign government] created the coronavirus as a bioweapon. To serve as a comparison, the third, which is not racialized, asks how likely it is that the pandemic is a plot perpetrated by one of three groups (Bill Gates, elites, global elites) to spread the virus via 5G. We first analyze these variables by pooling all responses across experimental conditions as well as subdivided by experimental condition (Table 1). In our experimental analyses, we utilize dummy variables for these conditions to examine the effect of treatment assignment on reliance on racial resentment and white identity. The cell sizes for the full sample and for white respondents only are available in Supplementary Table 3.

Table 1. Main effect of racial attitudes and experimental condition effects on conspiracy theory endorsement for white respondents only.

Our second set of dependent variables (Table 1) focuses on how respondents engage in protective behaviors related to the COVID-19 pandemic. While other scholars have focused more broadly on pandemic related behaviors (e.g., Imhoff and Lamberty, 2020), we focus here on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended behaviors and those behavioral restrictions resulting from CDC recommendations made as of May of 2020. We first utilize an additive scale of eight items asking whether a respondent washed their hands regularly, avoided in-person dining in restaurants and bars, sanitized their work and living spaces, engaged in “no-touch” greetings when meeting people, changed their travel plans, worked from home, canceled previously scheduled social engagements, and used pick-up or delivery options from restaurants and stores (alpha = 0.70). This scale runs from 0 to 8. However, the scale is a limited measure as some respondents may not have been able to work from home or had travel plans to change. Thus, it is not an all-encompassing measure of protective behaviors such as those utilized by others (e.g., Imhoff and Lamberty, 2020; Kroke and Ruthig, 2021; Earnshaw et al., 2020). Given this limitation, we also employ two independent Likert-style measures, one asking frequency of wearing a facemask and the other asking frequency of staying six feet away from other people. When the survey was fielded, the CDC and WHO had yet to recommend consistent mask wearing if you are unable to be socially distant (Associated Press, 2020). Also, at the time of data collection, no vaccines had been approved for use in the United States, so we utilize a measure of the likelihood of getting vaccinated. While there are extensive batteries to assess vaccine likelihood or hesitancy (e.g., Quinn et al., 2019), other scholars have utilized a single-item measure in the context of COVID-19 vaccine likelihood (e.g., Chen and Farhart, 2020; Callaghan et al., 2021; Motta et al., 2021; Stoler et al., 2021). All Likert-style dependent variables are recoded to run from 0 (lowest likelihood) to 1 (highest likelihood).

To assess generalized conspiracy theory belief, we utilize a combined set of three additional conspiracy theories such as politicians inflating counts to hurt President Trump's re-election chances, whether individuals or groups are benefitting financially from the pandemic, and whether politicians are trying to destroy the economy to hurt President Trump5. These three conspiracy theories are combined into an additive index (alpha = 0.58). Multiple scholars have identified that conspiracy theory belief is not only target specific and dependent upon the media and political environment, but also associated with an individual's predisposition for conspiracy belief. Thus, we control for respondents' underlying conspiratorial thinking predisposition, so as to differentiate the effects of racialized attitudes and identities from a conspiratorial predisposition in predicting conspiracy theory endorsement. Further, as belief in specific conspiracy theories could be impacted by other motives, particularly tied to political motivated reasoning (e.g., Miller et al., 2016), we also control for a generalized predisposition measured through conspiratorial thinking which utilizes a four-item scale (see Uscinski and Parent, 2014; Uscinski et al., 2016). Respondents were presented with four statements (e.g., “Much of our lives are being controlled by plots hatched in secret places”), and were asked to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with each one on a five-point scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” The four items were averaged together and the combined scale has high internal consistency (alpha = 0.80). While associated, these two indices are only moderately and positively correlated at 0.33 in the full sample and 0.39 among white respondents only, significant at p < 0.01.

Our main explanatory variables of interest include two measures of racial attitudes. First, we utilize a four-item measure of racial resentment as described by Kinder and Sanders (1996). This measure captures anti-black antipathy and is widely used (alpha = 0.77). We utilize Jardina (2019) measures of white identity, which were only administered to those who identified as white in our sample (alpha = 0.85). We also include a question designed to tap explicitly racialized attitudes about the pandemic. This question asks respondents to judge whether the term “Chinese Virus” is or is not racist. While not a general measure of anti-Asian attitudes, we utilized this measure as scholars have identified that anti-Asian attitudes were clearly activated and associated with COVID-19 attitudes and behaviors (Reny and Barreto, 2020). These measures are conceptually and methodologically distinct from one another, while only moderately and positively correlated with one another (r = 0.35 between white identity and racial resentment; r = 0.12 between white identity and the racialized COVID-19 question; r = 0.45 between racial resentment and the racialized COVID-19 question). Question wordings are located in Supplementary Table 2.

In addition to our variables of interest, we control for a number of socio-political variables. We include measures of party identification, ideology, sex, education, Hispanic, Spanish, or Latinx identification, income, region, age, and political knowledge.

While there is good evidence that COVID-19 conspiracy theory belief systems are monological (Miller, 2020), we still anticipate that certain coronavirus conspiracy theories are likely to be more racialized and identity threatening than others. As noted in our hypotheses, while we expect those high in white identity to endorse conspiracy theories writ large as a psychological defense against identity threat, while we believe instances of racialization are likely to be conditional on the framing of the conspiracy theory.

As Table 1 shows, for the three conspiracy theories tested, white identity predicts higher levels of conspiracy endorsement across the pooled conditions. For all three conspiracy theories, those higher in white identity are more likely to endorse the theory than those low in white identity. In contrast, the effects for racial resentment are mixed and statistically insignificant for two of the three conspiracy theories. These findings are above and beyond measures of conspiratorial thinking, which robustly predicts belief in our conspiracy theories, in addition to our measure of explicit racialized attitudes about whether the phrase “Chinese virus” is racist.

As expected, those who demonstrate greater attachment to their white identity appear to deal with the threat of the COVID-19 pandemic by leaning into conspiracy theory belief to explain the uncertain and threatening context. The same cannot be said for racially resentful individuals. For these individuals, we do not see significant main effects for racial attitudes on conspiracy theory belief. This analysis, however, fails to consider the possibility that specific conspiracy frames may activate racial resentment for respondents. We examine this next.

As noted above, while white identity appears to exert a fairly uniform influence on conspiracy endorsement, the effects for racial resentment appear far more mixed. To best understand these effects, Table 1 also presents results from a set of interaction models examining experimental condition assignment and the effects of racial resentment and white identity6.

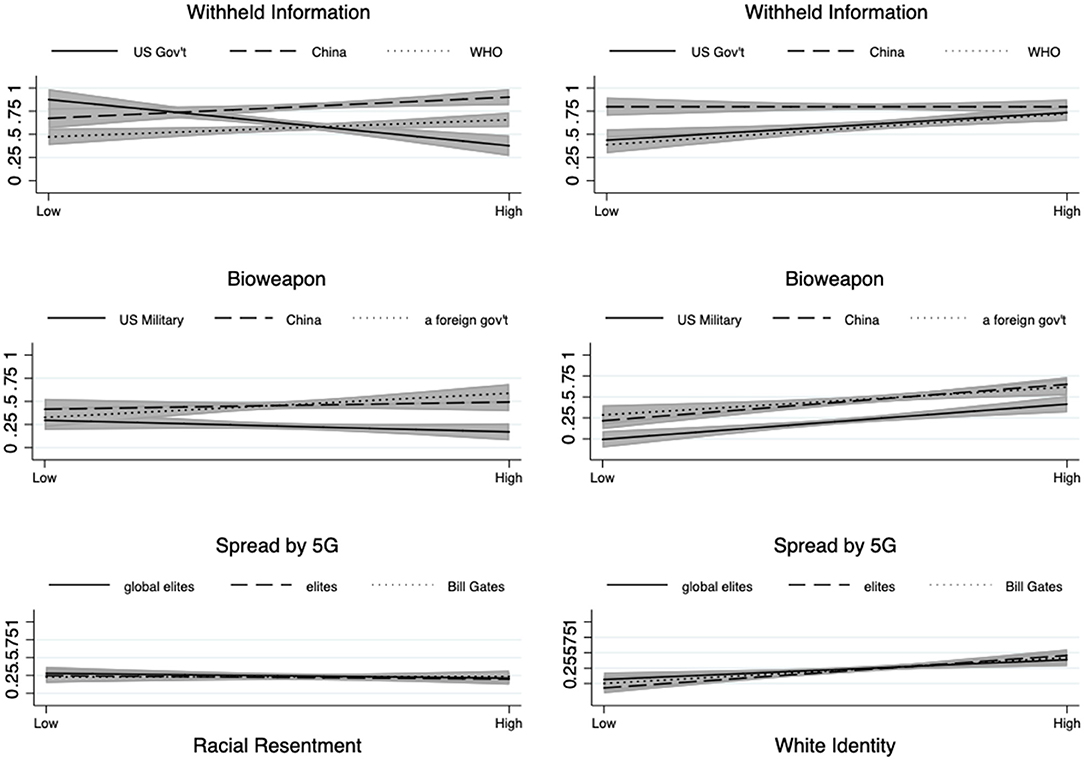

To ease interpretation, we also present a figure depicting the conditional effects of white identity and racial resentment by condition assignment across the three conspiracy theories. Turning first to white identity, the bottom row of Figure 1 shows strong support for our hypothesis that white identity will generally lead to higher conspiracy endorsement, regardless of condition assignment. Across eight of the nine conditions, white identity exhibits a strong, positive effect on conspiracy endorsement. Only for the conspiracy theory stating that China withheld information to downplay the severity of the pandemic do we see a null effect. In the case of this one conspiracy theory, however, the effect is not negative, but rather a consistently high level of endorsement among respondents, regardless of white identification.

Figure 1. Effects of racial resentment and white identity on conspiracy theory endorsement, by condition assignment (white respondents only).

In contrast, with racial resentment, we see clear evidence that conspiracy theory framing affects how racial attitudes structure conspiracy theory belief. For the first conspiracy theory, we see that racial attitudes are a strong, positive predictor of beliefs that China (b = 0.24, p < 0.005) or the WHO (b = 0.27, p < 0.001) withheld information about the pandemic, but that those same racial attitudes are a strong, negative predictor of beliefs that the U.S. Government withheld information (b = −0.67, p < 0.001). As the dependent variable is scaled to run from 0 to 1, these are substantively large effects. Across the range of racial resentment, endorsement of racially-framed conspiracy theories was nearly 25 percentage points higher for the most racially resentful as compared to the least racially resentful. Conversely, when the U.S. Government is cued, racial resentment decreases conspiracy theory endorsement by nearly 70 percentage points.

While not as strong of a relationship, a similar pattern emerges for beliefs that an entity released the coronavirus as a bioweapon. While there is no effect for racial resentment on beliefs that China did so (b = 0.14, p < 0.12), there is a positive relationship between racial resentment and belief that a foreign government did so (b = 0.27, p < 0.004). Again, this is a substantively large effect, with a nearly 27-point shift from the least to most racially resentful. In contrast, beliefs that the U.S. Military released it as a bioweapon were negatively related to racial resentment (b = −0.18, p < 0.04). Thus, when experimental conditions cue racialized theories (China, WHO), racial resentment exerts a positive influence on endorsement. When it cues an institution that is racially coded as white (U.S. Government, U.S. Military), the effect reverses and racial resentment leads to lower levels of endorsement.

By way of contrast, we also include a conspiracy theory without an explicitly racial frame, which is the third conspiracy theory (that Bill Gates, Elites, or Global Elites spread coronavirus via 5G). Here, while white identity is a strong predictor of support in all three conditions, racial resentment plays no role. Thus, racial resentment appears highly conditional on framing, while the effect of white identity is largely universal7.

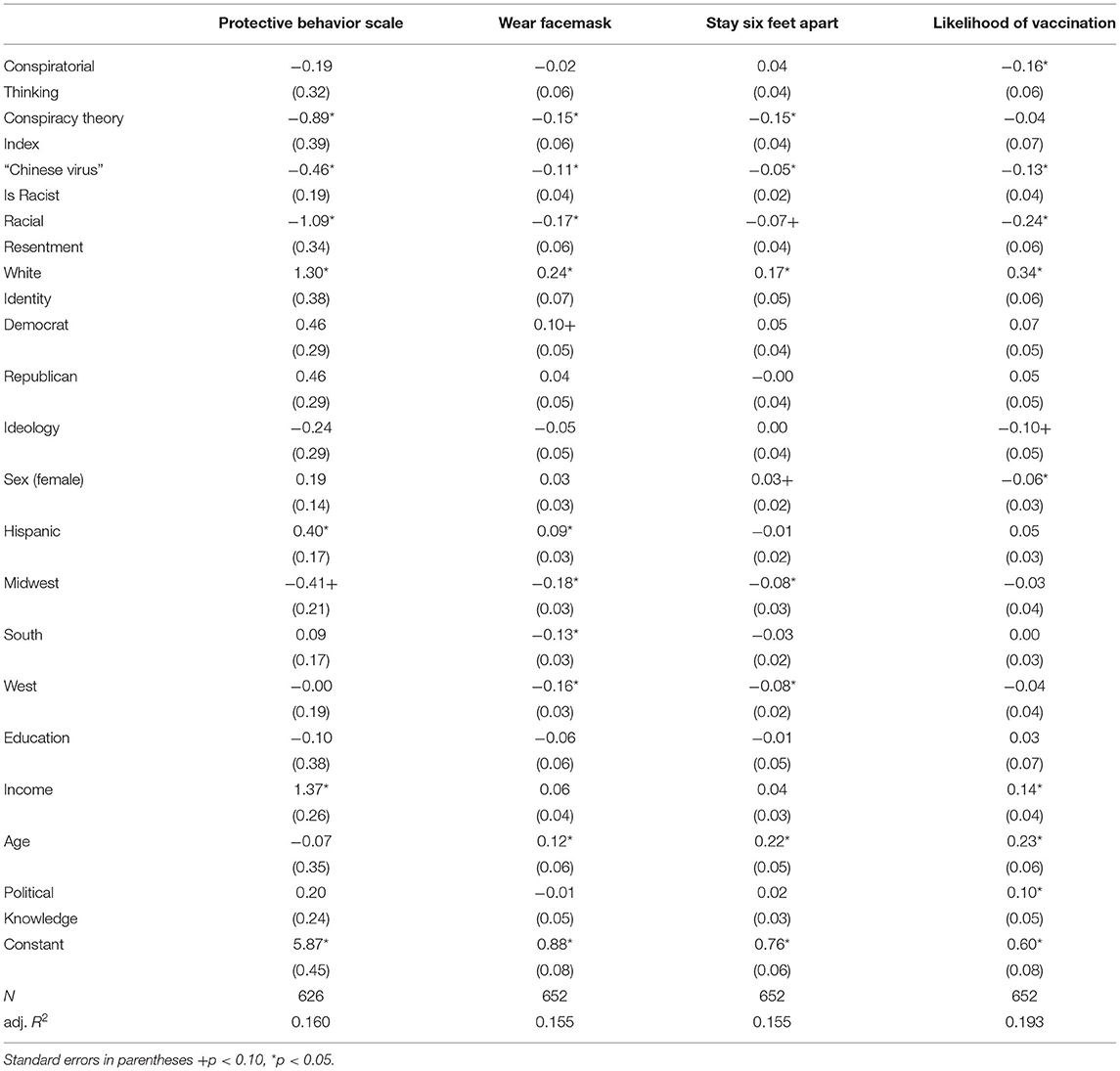

Lastly, we evaluated the effect of conspiracy theory endorsement, racial resentment, and white identity on protective, pro-social health behaviors. These results appear in Table 2. The results clearly indicate not only the influence of conspiracy theory endorsement and underlying conspiratorial thinking on protective behaviors, but also the extent to which these behaviors have become racialized (racial resentment, “Chinese Virus” question) and are salient for identity preservation (white identity).

Table 2. Effect of conspiracy theory endorsement on COVID-19 preventative behaviors for white respondents only.

We see the clearest evidence in the first column looking at the protective behavior scale. We find that believing in all of the conspiracy theories (as opposed to none) leads an individual to engage in ~0.89 fewer social distancing activities on average. Similarly, those who do not believe the phrase “Chinese Virus” is racist engage in fewer social distancing activities than those who do believe this is racist. The racial resentment scale produces a similar negative pattern, with more racially resentful people engaging in significantly fewer social distancing activities (b = −1.09, p < 0.05).

Interestingly, the coefficient for white identity is positive (b = 1.30, p < 0.05). This accords well with our theory, which expects that identity-threatening events (such as a pandemic) are likely to be taken more seriously by those who are heavily invested in a social identity such as whiteness. Rather than serving as a proxy for racial attitudes, white identity acts as a distinct identity-protecting attitude, as Jardina (2019) notes.

Turning to our other measures of pro-social behaviors, we see a similar pattern for conspiracy endorsement, although the coefficients fail to reach conventional levels of statistical significance except for reducing the frequency with which respondents stayed at least six feet away from others. In all models, however, the coefficients are correctly (negatively) signed. Conspiratorial thinking only produces a slight reduction in the likelihood of eventual vaccination. Additionally, the measures of racial attitudes and white identity are significant and correctly signed in all three additional models. These results demonstrate clearly that COVID-19 protective behaviors can serve as an identity protecting action, are deeply racialized, and are linked to generalized endorsement of COVID-19 conspiracy theories8.

In totality, these results present strong support for our hypotheses. To the extent that the COVID-19 pandemic is seen as a threat to an individual's identity, we see higher levels of conspiracy theory endorsement among those who highly value their whiteness as part of their identity. In contrast, racial resentment exerts an effect only when the conspiracy theory is racialized. If the conspiracy theory cues a racial out-group, racial resentment increases support for the theory. If the theory cues a racial in-group, racial resentment decreases support for the theory.

Within this study, we sought to assess the ways in which in-group affinity (white identity) and out-group hostility (racial resentment) affected protective, pro-social health behaviors and conspiracy theory belief during the early racialized coronavirus pandemic. We expected that those high in white identity would endorse conspiracy theories writ large as a psychological defense against identity threat and that racialization would be conditional on the framing of the conspiracy theory. We also expected that racial resentment and white identity would exert countervailing effects on protective, pro-social health behaviors.

Our findings demonstrate how deeply intertwined race and identity are within American politics. Over and above alternative explanations for conspiracy theory belief such as conspiratorial thinking, we find that white identity is a strong predictor of COVID-19 conspiracy theory endorsement and compliance with protective health behaviors. This underscores the power of the coronavirus pandemic as an identity-threatening event, particularly for white individuals, who were more likely to benefit from the pre-pandemic societal status quo. For individuals who deeply value their whiteness as an identity, the coronavirus appears to have driven these individuals to comply with public health recommendations while at the same time embracing conspiracy theories about the pandemic to provide clarity to an uncertain, threatening context.

In contrast, racial animus functions very differently. Racially resentful individuals are much less likely to engage in protective behaviors. More interestingly, these racial attitudes can be activated and brought to bear on conspiracy theory endorsement, but only when the conspiracy theories are framed in a racialized manner. When the subject of the conspiracy theory is a foreign actor, racial resentment predicts higher levels of endorsement. When the subject is coded white (the U.S. Government or Military), racial resentment exerts the opposite effect and decreases endorsement.

These results raise important questions about the spread of conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19 and the consequences for public health. Interestingly, the story is not as consistent as some might believe, in particular with regard to white identity. While we find that COVID-19 conspiracy theory endorsement and conspiratorial thinking may correlate with reduced compliance with protective health behaviors, higher levels of white identity increase compliance, potentially offsetting lower compliance that comes with conspiracy theory endorsement.

The findings around racial resentment, however, are more troubling. Not only does racial resentment have a direct effect on protective behavior (lowering the engagement with and the likelihood of compliance), but it also increases support for racialized conspiracy theories. Thus, it exerts both a direct and indirect effect on protective health behaviors, and in all cases, reduces compliance with public health recommendations.

While the effects of white identity were consistent across experimental conditions, we cannot rule out the possibility that the conditional effects for racial resentment are, in fact, a proxy for some other attitude (nationalism, ethnocentrism, collective narcissism, xenophobia). While we were unable to assess these constructs with our own data, nationalism, in particular, is a strong candidate for inclusion in future work examining conspiracy beliefs and COVID-19 conspiracy theories in particular. While we expect that other attitudinal constructs likely play a role, our results, particularly with regard to the 5G conspiracy theory, suggest that racial attitudes would likely still influence beliefs. Given that racial resentment is not cued by frames around “global elites”, we suspect that nationalism's effects are likely to be additive, over and above the effects of racial attitudes. Nonetheless, we are left to speculate until future research examines this possibility.

In sum, we must continue to assess not only the nature of public health compliance but also endorsement of conspiracy theories around said public health emergency. Our results suggest that, at least in the American context, these two sets of beliefs are intimately tied together through the lens of race and whiteness. If we hope to understand how best to win the public opinion battle in pandemic responses, we would be wise to look not only at individual attitudes around race and identity, but also to the ways that misinformation and conspiracy theories are implicitly and explicitly racialized in the public discourse.

The datasets presented in this study can be found on OSF. The DOI for these data is 10.17605/OSF.IO/HXDJA.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Boards at Carleton College and Beloit College. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.648061/full#supplementary-material

1. ^Racial resentment, therefore, is not a clear-cut measure of racial prejudice for all Americans, but rather may also convey some ideological principles for conservatives (Feldman and Huddy, 2005; Huddy and Feldman, 2009). Nonetheless, it is a widely used measure of racial animus in political science and, as our results show, the concept has convergent validity with other measures of racism specially related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. ^The evidence for racialized conspiracy theory belief is not extensive, but quite convincing. In particular, scholars have examined endorsement of the birtherism movement (Nyhan and Reifler, 2010; Tesler and Sears, 2010; Pasek et al., 2015; Berinsky, 2017; Enders et al., 2018; Jardina and Traugott, 2019) and perceptions of voter fraud (Wilson and Brewer, 2013; Udani and Kimball, 2017; Appleby and Federico, 2018). While nuanced, these findings all point consistently to a role for racial animus in predicting support for conspiracy theories, provided those theories are framed in racialized ways.

3. ^Responses were anonymized and the online data collection, as opposed to face to face, assists with reducing social desirability bias in responses regarding racial resentment and white identity, as well as conspiracy theory endorsement. The study was not formally preregistered. All replication files are available on OSF via DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/HXDJA.

4. ^Our question wording experiments are sufficiently powered to test our hypothesized effects, at 0.80, alpha 0.05, with cell sizes above a minimum of 93.

5. ^This index does not include the three conspiracy theories used for our experimental analyses.

6. ^While the models include measures that covary, VIF tests for multicollinearity do not identify any values greater than 2, except among the partisanship dummy variables themselves.

7. ^Our Supplementary Materials also include analyses that break down the pattern of results by partisanship. While partisanship plays an important role, it is relatively minor in contrast to the effects for white identity and racial resentment for endorsement of the racialized conspiracy theories.

8. ^Interestingly, we find few effects for partisanship, once we introduce our measures of racial resentment and white identity. This suggests that, while much of the rhetoric surrounding the pandemic is polarized and partisan, the drivers of attitudes and behaviors appear more grounded in racial attitudes and white identity for white respondents, with only occasional instances of partisan identity playing a key role. This pattern repeats itself across our analyses.

Abalakina-Paap, M., Stephan, W. G., Craig, T., and Gregory, W. L. (1999). Beliefs in conspiracies. Polit. Psychol. 20, 637–647. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00160

Abutaleb, Y., Dawsey, J., Nakashima, E., and Miller, G. (2020). The U.S. Was Beset by Denial and Dysfunction as the Coronavirus Raged. The Washington Post, April 4. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2020/04/04/coronavirus-government-dysfunction/?arc404=true (accessed December 30, 2020).

Appleby, J., and Federico, C. M. (2018). The racialization of electoral fairness in the 2008 and 2012 United States presidential elections. Group Processes Intergroup Relat. 21, 979–996. doi: 10.1177/1368430217691364

Associated Press (2020, June 5). WHO changes COVID-19 mask guidance: wear one if you can't keep your distance. NBC News. Available online at: https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/who-changes-covid-19-mask-guidance-wear-one-if-you-n1226116 (accessed December 30, 2020).

Benegal, S. D. (2018). The spillover of race and racial attitudes into public opinion about climate change. Env. Polit. 27, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2018.1457287

Berinsky, A. J. (2017). Rumors and health care reform: experiments in political misinformation. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 47, 241–262. doi: 10.1017/S0007123415000186

Brewer, M. B. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: ingroup love or outgroup hate? J. Soc. Issues 55, 429–444. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00126

Byford, J., and Billig, M. (2001). The emergence of antisemitic conspiracy theories in Yugoslavia during the war with NATO. Patterns Prejudice 35, 50–63. doi: 10.1080/003132201128811287

Callaghan, T., Moghtaderi, A., Lueck, J. A., Hotez, P., Strych, U., Dor, A., et al. (2021). Correlates and disparities of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19. Soc. Sci. Med. 272, 113638. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113638

Chen, P., and Farhart, C. (2020). Gender, benevolent sexism, and public health compliance. Politics Gender. 16, 1–8. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X20000495

Earnshaw, V. A., Eaton, L. A., Kalichman, S. C., Brousseau, N. M., Hill, E. C., and Fox, A. B. (2020). COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, health behaviors, and policy support. Transl. Behav. Med. 10, 850–856. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibaa090

Elias, A., Ben, J., Mansouri, F., and Paradies, Y. (2021). Racism and nationalism during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Ethnic Racial Stud. 44, 783–793. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2020.1851382

Enders, A., Smallpage, S. M., and Lupton, R. N. (2018). Are all ‘Birthers' conspiracy theorists? On the relationship between conspiratorial thinking and political orientations. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 50, 849–866. doi: 10.1017/S0007123417000837

Feldman, S., and Huddy, L. (2005). Racial resentment and White opposition to race-conscious programs: principles or prejudice? Am. J. Pol. Sci. 49, 169–183. doi: 10.1111/j.0092-5853.2005.00117.x

Filindra, A., and Kaplan, N. J. (2016). Racial resentment and Whites' gun policy preferences in contemporary America. Polit. Behav. 38, 255–275. doi: 10.1007/s11109-015-9326-4

Gilens, M. (1999). Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media, and the Politics of Anti-Poverty Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Goertzel, T. (1994). Belief in conspiracy theories. Polit. Psychol. 15, 731–742. doi: 10.2307/3791630

Haney López, I. (2015). Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Henderson, M., and Hillygus, D. S. (2011). The dynamics of health care opinion, 2008-2010: partisanship, self-interest, and racial resentment. J. Health Polit. Policy Law. 36, 945–960. doi: 10.1215/03616878-1460533

Huddy, L., and Feldman, S. (2009). On assessing the political effects of racial prejudice. Ann. Rev. Polit. Sci. 12 423–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.062906.070752

Imhoff, R., and Lamberty, P. (2020). A bioweapon or a hoax? The link between distinct conspiracy beliefs about the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak and pandemic behavior. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 11, 1110–1111. doi: 10.1177/1948550620934692

Jardina, A., and Traugott, M. (2019). The genesis of the Birther rumor: partisanship, racial attitudes, and political knowledge. J. Race Ethnicity Polit. 4, 60–80. doi: 10.1017/rep.2018.25

Jolley, D., and Douglas, K. M. (2014). The social consequences of conspiracism: exposure to conspiracy theories decreases intentions to engage in politics and to reduce one's carbon footprint. Br. J. Psychol. 105, 35–56. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12018

Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K., and Updegraff, J. A. (2016). Fear of ebola: the influence of collectivism on xenophobic threat responses. Psychol. Sci. 27, 935–944. doi: 10.1177/0956797616642596

Kinder, D. R., and Sanders, L. (1996). Divided by Color: Racial Politics and Democratic Ideals. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Knuckey, J. (2011). Racial resentment and vote choice in the 2008 U.S. presidential election. Polit. Policy 39, 559–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-1346.2011.00304.x

Kroke, A. M., and Ruthig, J. C. (2021). Conspiracy beliefs and the impact on health behaviors. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 14, 311–328. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12304

Mendelberg, T. (2001). The Race Card: Campaign Strategy, Implicit Messages and the Norm of Equality. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Miller, J. M. (2020). Do COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs form a monological belief system? Can. J. Polit. Sci. 53, 319–326. doi: 10.1017/S0008423920000517

Miller, J. M., Saunders, K. L., and Farhart, C. E. (2016). Conspiracy endorsement as motivated reasoning: the moderating roles of political knowledge and trust. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 60, 824–844. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12234

Motta, M., Callaghan, T, Sylvester, S., and Lunz-Trujillo, K. (2021). Identifying the prevalence, correlates, and policy consequences of anti-vaccine social identity. Polit. Groups Identities. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2021.1932528

Motta, M., Stecula, D., and Farhart, C. (2020). How right-leaning media coverage of COVID-19 facilitated the spread of misinformation in the early stages of the pandemic in the U.S. Can. J. Polit. Sci. 53, 335–342. doi: 10.1017/S0008423920000396

Nyhan, B., and Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: the persistence of political misperceptions. Polit. Behav. 32, 303–330. doi: 10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2

Oliver, J. E., and Wood, T. J. (2014). Conspiracy theories and the paranoid styles(s) of mass opinion. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 58, 952–966. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12084

Pasek, J., Stark, T. H., Krosnick, J. A., and Tompson, T. (2015). What motivates a conspiracy theory? Birther beliefs, partisanship, liberal- conservative ideology, and anti-Black attitudes. Elect. Stud. 40, 482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2014.09.009

Quinn, S. C., Jamison, A. M., An, J., Hancock, G. R., and Freimuth, V. S. (2019). Measuring vaccine hesitancy, confidence, trust and flu vaccine uptake: results of a national survey of White and African American adults. Vaccine 37, 1168–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.033

Reny, T. T., and Barreto, M. A. (2020). Xenophobia in the time of pandemic: othering, anti-Asian attitudes, and COVID-19. Polit. Groups Identities. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2020.1769693

Reny, T. T., Collingwood, L., and Valenzuela, A. A. (2019a). Vote switching in the 2016 election: how racial and immigration attitudes, not economics, explains shifts in white voting. Public Opin. Q. 83, 91–113. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfz011

Reny, T. T., Valenzuela, A. A., and Collingwood, L. (2019b). ‘No, you're playing the race card': testing the effecs of anti-black, anti-latino, and anti-immigration appeals in the post-Obama era. Polit. Psychol. 41, 283–302. doi: 10.1111/pops.12614

Schaller, M., and Neuberg, S. L. (2012). Danger, disease, and the nature of prejudice(s). Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 46, 1–54. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394281-4.00001-5

Sears, D. O., and Henry, P. J. (2005). Over thirty years later: a contemporary look at symbolic racism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 37, 95–150. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(05)37002-X

Sheagley, G., Chen, P., and Farhart, C. (2017). Racial resentment, Hurricane Sandy, and the spillover of racial attitudes into evaluations of government organizations. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 17, 105–131. doi: 10.1111/asap.12130

Sides, J., Vavreck, L., and Tesler, M. (2018). Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stoler, J., Enders, A. M., Klofstad, C. A., and Uscinski, J. (2021). The limits of medical trust in mitigating COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among black Americans. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 36, 3629–3631. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06743-3

Tajfel, H, Turner, JC, Austin, WG, and Worchel, S. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Hatch, MJ, and Schultz, M, editors. Organizational Identity: A Reader. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. (1979). p. 56–65.

Tesler, M. (2012). The spillover of racialization into health care: how president Obama polarized public opinion by racial attitudes and race. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 56, 690–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00577.x

Tesler, M. (2015). The conditions ripe for racial spillover effects. Polit. Psychol. 36, 101–117. doi: 10.1111/pops.12246

Tesler, M., and Sears, D. O. (2010). Obama's Race: The 2008 Election and the Dream of a Post-racial America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Udani, A., and Kimball, D. C. (2017). Immigrant resentment and voter fraud beliefs in the U.S. electorate. Am. Polit. Res. 46, 402–433. doi: 10.1177/1532673X17722988

Uscinski, J. E., Enders, A. M., Klofstad, C. M., Seelig, M., Funchion, J., Everett, C., et al. (2020). Why Do People Believe COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories? The Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review.

Uscinski, J. E., Klofstad, C., and Atkinson, M. D. (2016). What drives conspiratorial beliefs? The role of informational cues and predispositions. Polit. Res. Q. 69, 57–71. doi: 10.1177/1065912915621621

Uscinski, J. E., and Parent, J. M. (2014). American Conspiracy Theories. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

van Prooijen, J.-W., and Douglas, K. (2018). Belief in conspiracy theories: basic principles of an emerging research domain. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 897–908. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2530

van Prooijen, J.-W., and van Lange, P. A. M. (2014). “The social dimension of belief in conspiracy theories,” in Power, Politics, and Paranoia: Why People Are Suspicious of Their Leaders, editors J.-W. van Prooijen, and P. A. M. van Lange (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 237–253.

Wilson, D. C., and Brewer, P. R. (2013). The foundations of public opinion on voter ID laws: political predispositions, racial resentment, and information effects. Public Opin. Q. 77, 962–984. doi: 10.1093/poq/nft026

Keywords: racial attitudes, white identity, conspiracy theories, misinformation, COVID-19

Citation: Farhart CE and Chen PG (2022) Racialized Pandemic: The Effect of Racial Attitudes on COVID-19 Conspiracy Theory Beliefs. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:648061. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.648061

Received: 31 December 2020; Accepted: 07 February 2022;

Published: 21 March 2022.

Edited by:

Adriano Udani, University of Missouri–St. Louis, United StatesReviewed by:

Alexander Jedinger, GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, GermanyCopyright © 2022 Farhart and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christina E. Farhart, Y2ZhcmhhcnRAY2FybGV0b24uZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.