94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 12 January 2023

Sec. Politics of Technology

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.1062237

Introduction: This study aimed to examine the tactics and strategies of Indonesian public officials to restore their reputation after making false claims and policies on coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). The significance of this study can be separated into two categories. First, the application of image restoration theory to public organizations and public officials is uncommon. Second, it is essential to analyze the application of this theory to diverse social, political, and economic contexts of emerging nations; as a result, these distinctions may lead to varied research conclusions.

Methodology: A dataset of 2,000 Instagram posts by Indonesian public officials was generated to conduct the content analysis.

Results: This study found that reducing offensiveness, evading responsibility, and taking corrective action are the three most commonly seen practices followed by Indonesian public officials. This study confirms that denial and mortification are employed exceedingly infrequently in non-Western countries because both these strategies are believed to diminish the image of public leaders in public view.

Discussion: This study presents the practical implications that public officials or public relations experts who represent them must be cautious since it can have severe implications on their reputation. This study also argues that erroneous claims when posted by public officials attract unwanted public attention and negatively affect their image. Furthermore, this study provides practical implications for public officials and their representatives to be more cautious while handling media accounts.

In the early phase of the pandemic, the public had witnessed how public officials expressed skepticism and doubt or even denial of the presence of coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) (Djalante, 2018). There have been numerous instances of Indonesian public authorities making light of the COVID-19 virus and making jokes about it. Some of these instances are illustrated in Table 1. These actions have distanced the public from the perception of risk and actions taken to mitigate the impact of this pandemic (Mietzner, 2020). It was not only in Indonesia but also in other countries of the world such as Italy and Brazil, which have faced a similar problem (Mietzner, 2020). At the same time, governments around the world have been struggling to respond to COVID-19 and its multisectoral impact (Behrens and Naylor, 2020; Wang et al., 2021). They struggled to strike a balance between saving public health and the economy (Djalante et al., 2020). Experimental policies were their clear choice because such problems occurred rarely and knowledge about how to handle the COVID-19 pandemic was then not defined clearly (Enns et al., 2020; Zakaria and Hira, 2020; Chatterji et al., 2021). Consequently, some public officials presented blundering arguments and were criticized. Criticisms get worse when arguments go wrong.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the reputation of leaders and public officials has become one of the crucial organizational aspect (Verhoeven et al., 2014; Tokakis et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020). Reputation is a vital component of the value system and is part of the effort to reduce uncertainty in building good relationships between organizations and stakeholders (French and Holden, 2012; Heppell, 2021). Reputation is an intangible asset to differentiate one organization from another (Sawalha, 2020). In the public relations literature, it is important to keep the public informed during a crisis to maintain public trust (Dardis and Haigh, 2009; Clementson, 2021; Clementson and Beatty, 2021). This approach helps to avoid acts of neglect, misdirection, and marginalization of society that in turn will affect the reputation of the government.

When the policies are successful, the government and public officials appreciate the proper decision taken and, consequently, faith reposed by the public in the government can be increased and maintained (Dryhurst et al., 2020; Puri et al., 2020). When the policies fail, the reputation of the government and public officials becomes bad, and when their reputation is ruined in the eyes of the public, public trust will decline and eventually disappear (Sang et al., 2009; Falkheimer and Heide, 2015; de Regt et al., 2019). In the COVID-19 pandemic situation, the decline of public trust is intensely dangerous because people will be disobedient to the various directions and recommendations that public officials make.

In Indonesia, the statements given by public officials must be corrected immediately to avert a crisis. These expressions affect their reputation and the government's attempts to bring down the COVID-19 pandemic. During this pandemic, sustained image restoration of public officials is vital for three reasons. First, due to a lack of scientific evidence, the government's strategy for the COVID-19 pandemic is trial and error. The government replicates strategies often; therefore, the success and failure of policies are uncertain (Im and Campbell, 2020; OECD, 2020; Tashiro and Shaw, 2020). Second, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the government introduced measures to control public behavior to follow particular guidelines. In this regard, trust is important. The government and public officials may gain public trust only if they have a positive reputation, which is often damaged and must be restored (Puri et al., 2020; Ujunwa Melugbo and Amara Onwuka, 2020; Kagias et al., 2021). Third, massive disinformation, misinformation, and hoax news followed by an incumbent vs. opposition political struggle (Brennen et al., 2020; Dror et al., 2020; Agley and Xiao, 2021; Morgan et al., 2021). This makes the government the wrong party. A survey by Katadata (2021) reveals the indicators of public mistrust in the government, such as compliance with health protocols and participation in general elections.

Image restoration in the literature has been discussed and explored in qualitative (Avraham and Ketter, 2013; Ha and Boynton, 2014; du Plessis, 2018) as well as quantitative research (Kim et al., 2009; Avery et al., 2010), especially in developed country settings (Fishman, 1999; Ulmer et al., 2007; Hanna and Morton, 2020; Triantafillidou and Yannas, 2020) and within the government (Kim et al., 2011; Zeng et al., 2018), business organizations (Coombs, 2004; Erickson et al., 2017; Zeng et al., 2018), and religious organizations (Legg, 2009). In the meantime, it is necessary to study the application of image restoration theory in different contexts, such as public organizations in developing nations, to contribute to the body of knowledge. To fill this gap, this study explored the image restoration of public officials during the COVID-19 pandemic situation using content analysis strategies from public officials in a developing country setting, particularly Indonesia.

This research was conducted on Instagram because Instagram is the most popular social media site, surpassing Twitter and Facebook (Katadata, 2022). Instagram is able to comprehend Indonesian culture, particularly among the youth, due to its more visual features such as images and videos (Volo and Irimiás, 2021). Additionally, politicians make their presence felt on Instagram to promote their image (Pratiwi et al., 2022). Instagram mixes text and photographs, as well as comments, which are essential for demonstrating many types of phenomena, such as the phenomenon of political communication, in this study.

William L. Benoit explained that, after the occurrence of a case that triggered a crisis, a company or individual can improve its or his/her reputation using several strategies. Benoit (1995) proposed the theory of “image repair” that explains image restoration. This theory focuses on the defensive communication genre that is used to “reduce, repair, or avoid reputational damage” (Gai, 2016; Zeng et al., 2018; Nazione and Perrault, 2019). Five strategies can be used to respond to a threat or crisis, including (1) denial and (2) evasion of responsibility, where companies and individuals deny/avoid and reduce responsibility for the alleged actions. Meanwhile, (3) reducing offensiveness or events and (4) corrective actions are reputation-improvement actions taken by companies or individuals. The focus is on reducing the anger or hatred of the alleged actions against the company or the individual. Lastly, (5) mortification is when the company or individual does so by apologizing to the harmed parties (Benoit, 1995).

Restoring or protecting reputation becomes the main goal for organizations or individuals after experiencing a crisis. For individuals and organizations, reputation is a highly important asset (Benoit, 1995, 2003; Benoit and Czerwinski, 1997; Carnevale and Gangloff, 2022). Image restoration theory is applied not only to case studies of companies but also to government entities, so this study extends its application to the public sector (Yamazaki, 2005; Marcoux et al., 2013; Ayoko et al., 2017; Pollach et al., 2022).

Image and reputation are assets that are built over a long period. Individuals and organizations strive to protect and maintain a positive reputation in the minds of their public. On a larger scale, the government's reputation can also be threatened into a crisis if it is not handled properly and has an impact on the public's trust (Kim et al., 2011; Siddiqi and Koerber, 2020; Chen and Wang, 2021). This makes leaders, government, or public officials proactive toward arising issues.

The crisis response strategy has three functions, including instructing information, adjusting information, and reputation repair. Most of the research on crisis communication focuses more on the reputation repair process, while the other two functions, instructing information and adjusting information, are less prominent in the literature that examines crisis communication (Coombs, 2006).

As a crisis response strategy, instructing information implies telling stakeholders how to avoid physical or financial loss. Instructing information is crucial during health emergencies, product recalls, natural disaster, and other threats to public safety and welfare. Protection is crucial for preventing damage or loss, and the organization must convince stakeholders that a set of recommended activities is a reliable “tool” to protect themselves.

Adjusting information may help crisis efforts. Transparency and a consistent flow of information are critical to coping with a crisis. Adjusting information informs the organization's corrective actions and steps to prevent future crises (Coombs, 2004, 2014; Ulmer et al., 2007; Zeng et al., 2018). A reputation repair strategy protects an organization's reputation and image during a crisis. Impression management, corporate apologia, and image restoration are reputation-improvement theories.

This study presents the research on the comparative quantitative content analysis to perceive the reality based on empirical data on the image restoration of public officials in the COVID-19 pandemic situation in Indonesia. Comparative quantitative content analysis is a strategy to categorize certain content by comparing it with similar content (Schlægera, 2013; Hwang et al., 2019). Furthermore, this study used multiple case-study strategies to examine every detail of the case and the complexity of the situation. To understand the characteristics and uniqueness of the case (Yin, 2018), this study compared the image restoration of public officials in the central, provincial, and local governments. To achieve this goal, this study also compared the image restoration of public officials in the 3 months after the statement was made and the case of the Coronavirus Omicron Variant since the Government first confirmed the emergence of the case as a contrarian.

This study explored the Instagram accounts of public officials due to their mistakes in giving statements on social media. Instagram has been having more than one billion active users since 2010 (Statista, 2021). Due to Instagram's popularity, politicians and government agencies use it to share visual content. Instagram's ability to facilitate two-way, ad hoc communication using images and text makes it an intriguing research object. Table 1 contains cases and Instagram accounts of public officials who are the research subjects. For cases of retired public officials, we excluded these cases from this study. These retired public officials include the Former Health Minister Terawan Agus Putranto and the Former Spokesperson for the COVID-19 Task Force Achmad Yurianto.

The data in this study were collected automatically using the Instagram Scrapper application. This application allows the researchers to retrieve data from Instagram in the form of photographs, videos, captions, comments, and the number of likes, within a certain period, from particular accounts or particular hashtags. Public officials' Instagram accounts were entered into the search field to retrieve data in the form of photographs, captions, and comments as well as the number of likes of each content. The data collection period is 3 months since the first false statement about COVID-19 was first uploaded and 16 December 2021–16 February 2021 (Coronavirus Omricon Variant).

Once the data were collected through the application, data cleaning was then carried. Given that there are not only images but also videos, we excluded videos from the data for analysis purposes. Moreover, because what data were collected were from a personal Instagram account belonging to a public official, these accounts might share personal photographs, such as family photographs. For analysis purposes, we also cleaned these data. Each image and caption was labeled. Once the data cleaning was done, we applied the content analysis both from captions and photographs. The content categories are listed in Table 2.

The coding process was carried out through three rounds (Bellström et al., 2016). In the first and second rounds, the first and second researchers did the coding separately using Microsoft Excel. In the third round, the third researcher confirmed the findings and marked the results of the different content analyses. In the case of finding different content analyses, the three researchers discussed them together to determine only one content category.

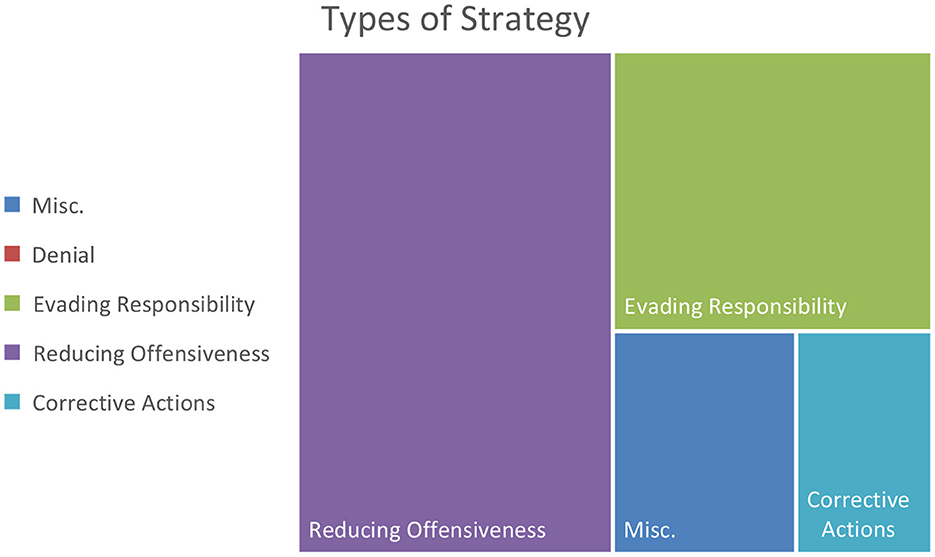

Figure 1 presents a collection of the various image restoration strategies carried out by public figures after issuing statements that have attracted both attention and controversy in the community. The seven public figures came from various backgrounds, ranging from vice presidents and ministers to governors, and mayors who were in the public spotlight after giving oblique statements when the pandemic hit Indonesia in 2020.

Figure 1. Types of image restoration strategies carried out by public officials in Indonesia (Obtained from primary data).

As a strategy that is used to restore a good reputation for public figures, several steps are taken. The utilization of strategy provides an overview of the main objectives of the individuals who implement the strategy. Of the five forms of defensive communication in Benoit's image repair theory, the data obtained show that there are three more dominant strategies used by selected political figures to reduce, repair, or avoid reputational damage, including reducing offensiveness, evading responsibility, and corrective actions.

The three steps taken by political figures in this study indicate that they focus on reducing negative responses, such as public anger and hatred, as well as reducing the moral burden of responsibility for the ambiguous meaningful opinions they issue on the urgency of the spread of coronavirus, which has a major impact on public health in Indonesia.

The obtained data show that the most widely used image restoration strategy by public figures is Reducing Offensiveness (994 posts). Messages conveyed in the form of posts on the Instagram account take the form of bolstering, minimization, differentiation, to transcendence where these types of tactics are included in the category of reducing offensiveness strategies. Of the seven public figures, Figure 1 shows that the Minister of Transportation Budi Karya stands in the first place as the public figure who uses this strategy the most, reaching 73.7% in 301 posts on his personal Instagram account. It is followed by Edy Rahmayadi reaching 70%, Ridho Yahya reaching 63.1%, Luhut Pandjaitan reaching 30.8%, Mahfud MD reaching 29.4%, and Yasin Limpo reaching 23.2%. Meanwhile, Ma'ruf Amin was recorded as the public figure who uses the least reducing offensiveness strategy with a percentage of 6.6%.

Most political figures choose to use reduced offensiveness within 1–2 weeks after issuing a blundering opinion, which is considered a public official's response in the eyes of the public. These political figures seek to reduce negative comments and public anger by showing concern and how responsive political figures are in dealing with pandemic cases in each region, starting by distributing and reviewing the health infrastructure during a pandemic and many of them even go directly to the field to simply distribute free masks and visit patients with COVID-19. After 1–2 months have passed, the implementation of this strategy is shifted to the stressing tactic that portrays the extent of the role and contribution of the political figure to the public, closeness to influential community leaders, and others.

In addition to reducing offensiveness, many political figures also convey messages on the social media of Instagram, which is considered a form of Evading Responsibility strategy of 559 posts. The steps taken to reduce the moral burden and responsibility of political figures after issuing such ambiguous opinions are not frontal but subtle steps with the Good Intentions tactic as in Figure 2. Edy Rahmayadi posted a photograph with a caption of “Looking at monitor screens like this, I always think about the condition of this nation, which is currently being tested by the COVID-19 pandemic. As a leader, I realize how much people expect to come out of this test. Hope is what drives me every day. I am sure, if we are sincere in our endeavors and solely serve for the good of the people, God willing, we can overcome any problem together.” Imaging the good intentions behind opinions that raise questions in the eyes of the public are most of the steps taken by these public figures, for example, creating regulations that help ensure public safety and health during the pandemic, providing counseling and guidance on maintaining health, and giving statements to the media crew about the emphasis on taking the best steps that political figures will take for the good of society during the pandemic.

Figure 2. Types of image restoration strategies for each public official (obtained from primary data).

Figure 3 shows the Vice President of the Republic of Indonesia, Ma'ruf Amin, reaching 70.4%. It is followed by other public figures, Yasin Limpo reaching 51.4%, Mahfud MD reaching 42.6%, Luhut Pandjaitan reaching 36.5%, Edy Rahmayadi reaching 11.2%, Ridho Yahya reaching 9.9%, and Budi Karya reaching 2.3%. For example, out of a total of 395 posts, 70.4% of the posts on Ma'ruf Amin's Instagram account contained content that seemed to reduce the burden of responsibility as a political figure who also issued ambiguous opinions on the COVID-19 pandemic phenomenon. Many of the Vice President's posts are focused more on diversions that are displayed using the Good Intentions tactic where it appears that there are several attempts from Ma'ruf Amin to improve the situation more subtly and responsibly and not to immediately shift the issue in a frontal way as in Figure 4 with a caption of “Today accompanied President Joko Widodo inaugurating the Board of Trustees and Directors of the Health and Employment Social Security Administration Agency (BPJS) at the State Palace, Jakarta. I congratulate you on working and serving the nation.” For example, remaining active in politics and carrying out his duties as vice president professionally even amid the pandemic, helping to provide assistance to the community, and not mentioning many things related to controversial policies or opinions that he had previously expressed in public.

Figure 4. Ma'ruf Amin continues to attend official meetings by accompanying the President of the Republic of Indonesia amid the pandemic (obtained from Instagram).

Based on the results of data collection through posts on the Instagram of the seven Indonesian political figures, the researchers did not find any denial strategy that was carried out openly to deny the blundering opinions they had conveyed to the public. On the other hand, the steps taken are actions that are considered safe and some of them avoid responsibility after issuing statements that raise questions in the community. Another effort made was corrective actions with a total of 191 posts. The political figures who mostly use this strategy based on Figure 3 are Luhut Pandjaitan reaching 26.9%, followed by Ma'ruf Amin reaching 16.5%, and Budi Karya reaching 15% with a not too significant percentage gap, Ridho Yahya reaching 10.8%, Mahfud MD reaching 7.4%, Edy Rahmayadi reaching 4.6%, and Yasin Limpo reaching 3.8%.

All political figures in this study have at least taken this action several times through their social media. The strategy applied is also not too clear and frontal, but rather implied, which will usually be seen from the contents of the captions written or the gestures of the political figures in an agenda. For example, those who previously rarely used masks in meetings then turned to be so obedient to health protocols that they often gave advice to the public to comply with government regulations regarding the safety and health of residents during the pandemic.

In Figure 5, Ridho Yahya took corrective action after public and media criticism for not taking schoolchildren off during the outbreak with a caption of “I have dismissed the state civil servants and students, but I and the head of the local government organization are still not on vacation to monitor any developments in Prabumulih. Service to the community must continue to be carried out. @humas. Prabumulih.” In Figure 5, he did not explain his reasons and actions. However, in the video of a regional government meeting forum, he clarified. Five hundred thirty-six people liked and 4,142 people watched this video. Compared to other posts on Ridho Yahya's Instagram, this number is considerable. The comments on these posts range from positive and supportive to critical and insinuating.

Finally, the seven political figures also uploaded several posts that were categorized as posts that were not included in the image restoration strategy that were labeled with Miscellaneous in Figure 3. The accumulation of all these types of posts belongs to Yasin Limpo who reached 21.6%, Mahfud MD who reached 20.6%, Ridho Yahya who reached 16.2%, Edy Rahmayadi who reached 13.8%, Budi Karya who reached 9%, and Ma'ruf Amin who reached 6.8% and the lowest number is obtained by Luhut Pandjaitan of 5.8%. After analysis of the process, the researchers noticed that there were many posts of political figures that were not indicated as a form of imaging and image restoration to maintain the good work of the seven figures in the community.

In his explanation, Benoit stated that when public figures feel threatened by their reputation, they will try to restore their reputation by implementing the tactics of recovering reputational damage. In this study, seven political figures were analyzed and their movements were seen for the next 1 year after the blunder statement was made to regain support from the community and rebuild the good reputation of these political figures.

Political figures upload content consisting of pictures or videos or even a combination of the two, which is then equipped with a “caption” or documentation information to further convince the audience who sees the content. The captions usually listed on the uploaded content contain persuasive sentences, descriptions of activities, appeals, or even calming sentences to attract the sympathy of the audience.

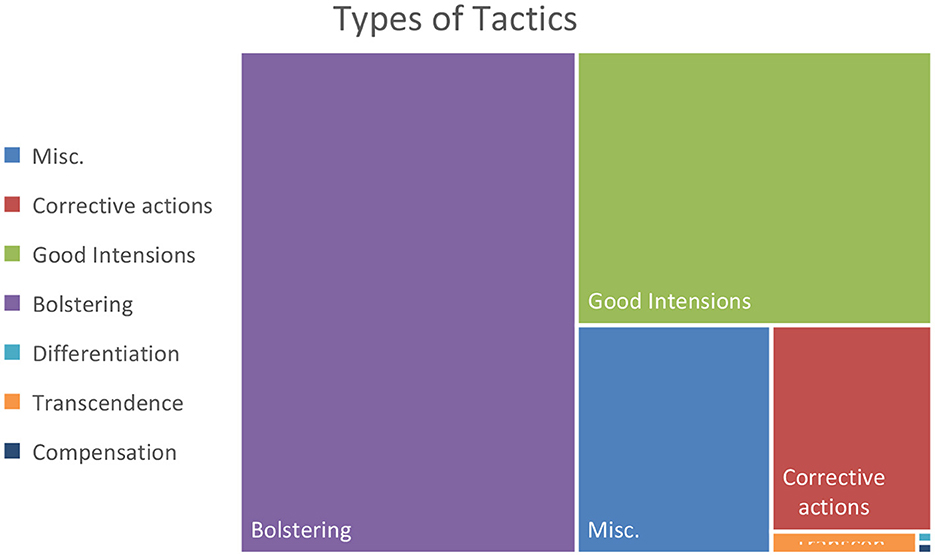

Figure 6 shows that of the various tactics proposed by Benoit in his image repair theory, six tactics are most often used by these political figures: compensation, transcendence, differentiation, bolstering, good intentions, and corrective actions which are carried out clearly or implied.

Figure 6. Types of image restoration tactics done by public officials in Indonesia (obtained from primary data).

The “Bolstering” strategy is utilized most commonly by these seven politicians. Bolstering is a strategy of restoring a politician's reputation by emphasizing their “good traits” or past or new achievements. Edy Rahmayadi employs the bolstering strategy most often to achieve popular support, according to research. Five hundred sixty-four of 821 Instagram posts (68.7%) were referring to bolstering tactics. Budi Karya (BK) followed with 71.7% or 215 of 300 posts referring to the bolstering strategy. Ridho Yahya (RY) utilizes bolstering in 63.1% of his 111 posts. In the post of the three political individuals, bolstering is the most dominant step, while for the other four, it is the second. Syahrul Yasin Limpo (SYL) had 23.2@ (43 bolstering posts out of 136 total content), Ma'ruf Amin (MA) had 6.6% (26 bolstering posts out of 395 total content), and LP had 30.8% (16 bolstering posts out of 52 total content).

In Figure 7, Syahrul Yasin Limpo looks focused while attending a virtual Zoom meeting with his staff and colleagues, while implementing physical distancing. The caption is “Alhamdulillah. The Ministry of Agriculture again won Unqualified Opinion (WTP). This is an achievement, because this award means that the Ministry of Agriculture carries out budget management in an accountable, credible and transparent manner in accordance with government accounting standards.” Syahrul Yasin Limpo emphasized further that this achievement was solely due to the hard work of the Ministry of Agriculture, which followed the indication of assessment.

This 25 June 2021 video shows Syahrul Yasin Limpo using the bolstering tactic as a way to improve his reputation. The public reacted positively to this post with compliments and praise in the Comment section. Moreover, thousands of people gave likes. “Good Intentions” is the second-most-used tactic by these seven politicians. Politicians compete to prove their good intentions. All actions aim to elicit community sympathy. Four of the seven political figures we analyzed use the “Good Intentions” strategy to minimize negative responses and public anger.

Figure 8 shows KH. Ma'ruf Amin is the first political figure to aggressively implement the Good Intentions tactic. This can be observed from the total content of KH. Ma'ruf Amin, with 70.1% or 277 contents of the total 395 posts leading to good intentions. Syahrul Yasin Limpo commonly uses this strategy. Based on Figure 8, 51.4% or 95 content out of 185 use the good intentions strategy. Mahfud MD and Luhut Pandjaitan also used this tactic to restore their reputation. Only 42.6% of Mahfud MD's 136 postings use this strategy. Nineteen out of 52 posts uploaded by Luhut Pandjaitan or 36.5% use this strategy.

Edy Rahmayadi, Ridho Yahya, and Budi Karya do not prioritize good intentions in restoring their reputation. Only 11.2% of Edy Rahmayadi's 821 posts use good intentions. Meanwhile, in the posts made by Ridho Yahya, the tactic of good intention occupies the lowest rank compared to the use of other tactics. Eleven out of 111 content (9.9%) apply the tactic of good intention. Budi Karya's personal Instagram account is only 7 out of 300, or 2.3%. Here is an example of a politician's implied good intentions tactic. Luhut Pandjaitan as the Coordinating Minister for the Maritime and Investment Affairs of Indonesia shared the good intentions tactic, as shown in Figure 9.

The last name's clan “Pandjaitan” shows he is a native Batak descendant. Luhut is a Christian. On 23 April 2020, he uploaded 59-second reels of content and said “I wish you a happy fasting month of Ramadan 1441 H for my Muslim brothers. I hope that our Muslim brothers and sisters can carry out their fasting worship well even though we are currently facing the storm of the COVID-19 pandemic. Maintain health, maintain cleanliness, stay at home, don't travel if there is no urgent need, and if forced to leave the house, don't forget to wear a mask. Hopefully, with the spirit of fasting, we will take better care of each other and care for one another so that the Indonesian people are able to overcome this storm of the COVID-19 pandemic together.” to all Muslim communities, which was followed by sentences urging the public to remain at home, avoid going out if there is no urgent need, and always maintain cleanliness to break the chain of COVID-19.” Luhut Pandjaitan's post in Figure 9 shows religious tolerance. Even though he is not a Muslim, he wants to show his concern with an appeal. Luhut Pandjaitan's facial expression and low intonation added a positive impression to his reputation.

The corrective action tactic focuses political figures on repairing reputation damage by implementing corrective actions or preventing the recurrence. At this stage, public officials take concrete action to show their engagement in corrective or preventive action.

Figure 8 shows that KH. Ma'ruf Amin dominates the application of the corrective action strategy to restore his good reputation. Only 16.5% or a total of 65 content from the total 395 posts is the application of the corrective action tactic. Budi Karya also utilizes corrective action. Judging from the percentage gain of nine pictures, 15% or 45 of the total content of 300 posts is a form of the corrective action tactic. Luhut Pandjaitan also uses it. Corrective action was taken on 26.9% (14 of 52) of his Instagram postings.

Ridho Yahya, Mahfud MD, Edy Rahmayadi, and Syahrul Yasin Limpo rarely apply corrective action. Only 10.8% of Ridho Yahya's 52 posts are about corrective action. Mahfud MD's corrective action content is 7.4%, or 10 out of 136 postings. Edy Rahmayadi is the lowest percentage of corrective action tactic, at 38 content out of 395 postings. Here's how KH. Ma'ruf Amin used corrective action.

Figure 10 showed that KH. Ma'ruf Amin shared on Instagram that on 17 February 2021, he got the COVID-19 vaccine while still adhering to the applicable health protocols, particularly wearing a mask and face shield as written in the caption “Thank God this morning I received the CoronaVac vaccine as a joint effort to maintain immunity from the COVID-19 virus. The vaccination program is a major effort currently being carried out by the government which aims to create herd immunity. Herd immunity can only be achieved if 70% or 182 million of Indonesia's 270 million population have been vaccinated.” Two medical personnel assisted KH. Ma'ruf Amin with the injection. KH. Ma'ruf Amin uploaded a photograph with a caption. This vaccination program is one of the government's efforts to create herd immunity and prevent the spread of coronavirus transmission. Captions on the benefits of the COVID-19 vaccine for the Indonesian people and KH. Ma'ruf Amin's willingness to inject the vaccine were allegedly implicit corrective actions.

Not all political figures use the next strategy, “transcendence.” The transcendence tactic is utilized to restore a good name by placing an action in a favorable context. Figure 8 shows how often Edi Rahmayadi and Budi Karya use the transcendence tactic. Only 1.6% or 13 of Edi Rahmayadi's posts 1 year after his blunder statement use the transcendence tactic. Two percent of Budi Karya's posts since 17 February 2020 are a form of transcendence tactic on six of the total posts.

The Minister of Transportation of the Republic of Indonesia, Budi Karya, used the transcendence tactic to make his statement more public-friendly. As written in the captions of several posts that show the adjustment steps from the previous one, the political figure seems to misunderstand the urgency of the spread of COVID-19 behind the jokes.

Budi Karya uploaded the picture in the first week of transcendence after conveying a humorous opinion on the spread of coronavirus by appreciating the performance of the sea transportation sector in anticipating the spread of the virus. The Minister of Transportation of the Republic of Indonesia seemed to be apathetic to the implementation of health protocols during the coronavirus, as shown Figure 11 with the caption of “I really appreciate the performance of friends in the field of sea transportation in dealing with preventing the spread of the Corona Virus (COVID-19). Especially @pelindo1, Pelindo 2, @Pelindo3, and @pelindo_4 which have increased awareness and anticipation of the spread of the Corona Virus to Indonesia through International Ports within the Pelindo environment. Thank you for continuing to carry out checks on embarkation and disembarkation passengers, tightening supervision and control, supervision of foreign crew/crews who dock at each branch of the International Port, both passenger and cargo terminals. –BKS.” The “compensation” recovery tactic provides compensations or assistance to harmed parties. Political figures rarely utilize compensation to restore their reputation. Figure 8 shows that 1 year after the blunder statements were issued by seven political figures we analyzed, the compensation strategy was used only once by Mahfud MD. Furthermore, 0.7% of Mahfud MD's 136 posts are from one picture material consisting of several slides.

In Figure 12, Mahfud MD shared four picture slides showing sympathy for the families of SMPN 1 Turi Sleman Yogyakarta students who were drowned in a river. Mahfud MD listened to the account of the students' drowning with political figures, staff, and colleagues. In this post, Mahfud MD also shared his documentation when handing over assistance in the form of gifts to representatives of the families. Mahfud MD also wrote a photo caption about condolences, particularly by visiting the victims' families, praying for them, and providing assistance, clearly led to compensation. Mahfud MD has gained public sympathy with this post. Almost the entire comment column was filled with praise for Mahfud MD.

The “Differentiation” is the last tactic examined. In this tactic, to restore their reputation, political figures place the action favorably. This strategy is used once by one of the seven politicians, after “Compensation.” Edy Rahmayadi is the only politician who uses all of Benoit's tactics, as shown in Figure 8, 0.1% of 821 posts or 1 post leads to the differentiation. Edy Rahmayadi's Instagram feed shows the differentiation tactic in action.

Figure 13 shows Edy Rahmayadi and his wife wishing “Longevity for KOSTRAD.” In his caption, Edy Rahmayadi explained that he led KOSTRAD as his last TNI corps. Through this post, Edy received a great response from the audience, such as congratulations, praises, and some emoticons.

This study discusses strategies for image restoration of public officials in Indonesia after making false claims or policies regarding COVID-19 in Indonesia. This study addresses a gap in image recovery research because most of the previous studies are from private sectors in developed countries (Eriksson and Eriksson, 2012; Ferguson et al., 2018; Le et al., 2019; Page, 2019; Arandas and Ling, 2020; Corazza et al., 2020; Hanna and Morton, 2020). Providing an overview of the restoration of the reputation of public officials in a developing country, particularly Indonesia, will produce a more comprehensive overview of the use of image recovery theory in the context of different economic, political, and social situations as well as information and communication technology which is not as established as in developed countries. Our study found several findings that confirmed some previous studies and also found new, enriching image recovery findings.

This study found that public officials in Indonesia employ a variety of strategies to restore their reputations. This study indicated that reducing offensiveness, evading responsibility, and corrective actions are the three main strategies that are common in Indonesian public officials' posts. Second, the approaches include bolstering, good intentions, corrective actions, transcendence, and compensation. Denial and mortification were not found in this study. This is in line with previous research, especially when the image recovery theory is applied to developing countries (Yamazaki, 2005; Zeng et al., 2018; Ban and Lovari, 2021; Wong et al., 2021).

This study indicated that reducing offensiveness was carried out using the bolstering, transcendence, and compensation tactics. Reducing offensiveness seeks to help reduce the overall effect of actions taken by individuals or organizations (Lancaster and Boyd, 2015; Hanna and Morton, 2020; Heppell, 2021). The results show that individuals and organizations aim to reduce offensiveness using a strategy of bolstering and minimization (Sellnow et al., 1998; Erickson et al., 2017; Zeng et al., 2018; Demaline, 2021). Reducing offensiveness is often used in crises involving political power. Transcendence, a subcategory of reducing offensiveness, involves the argument “that offensive actions have a higher purpose” (Herrero and Marfil Medina, 2016; O'Connell et al., 2016). Transcendence is a successful way to deal with scandals or political crises. Transcendence is used frequently, though not always successfully (Arendt et al., 2017).

Second, the strategy of evading responsibility uses good intentions. According to the literature, this is a successful strategy (Holtzhausen and Roberts, 2009; Valdebenito, 2013; Arendt et al., 2017; Sawalha, 2020; Gribas et al., 2021). The organization may not be able to deny some responsibility for the failure and will thus communicate a message that reduces its responsibility for the crisis (Benoit, 1995). Through this strategy, the organization may wish to demonstrate that it has limited responsibility for the failures or crises. This may also require tactics, such as denial (using a lack of control or information as a tactic to reduce responsibility for the crisis) or provocation (indicating that the organization is being forced into the crisis because there is no other way out) (Falkheimer and Heide, 2015; Lin, 2021).

Third, public officials in Indonesia use corrective action. This strategy is included in the literature to restore the reputation of the organization (Arendt et al., 2017). This strategy involves fixing problems or making improvements to prevent misconduct (Blaney et al., 2002; Holdener and Kauffman, 2014; McCoy, 2014; Arendt et al., 2017). Corrective action improves an individual's or organization's professional reputation by 57% when used as an apology (Arendt et al., 2017). Corrective action has been applied in product recalls, well-known sports teams and athletes, and natural crises leadership (Blaney et al., 2002; Deshpande and Hitchon, 2002; Rogers et al., 2005; Holdener and Kauffman, 2014; Arandas and Ling, 2020; Heppell, 2021). Furthermore, Griffin-Padgett and Allison (2010) found corrective action improved crisis response.

As the literature shows, organizations often use denial (Blaney et al., 2002; Yamazaki, 2005; Fortunato, 2008; Kauffman, 2012; Valdebenito, 2013). It is the least successful strategy. Denying wrongdoing lacks credibility and transparency in crisis response (Arendt et al., 2017). After a large-scale crisis, this denial of wrongdoing led to inadequate image repair (Fortunato, 2008; Valdebenito, 2013; Falkheimer and Heide, 2015). This study also lacks mortification. According to the literature, individuals and organizations avoid admitting mistakes and apologizing because they must take responsibility (Benoit, 1997a,b; Sheldon and Sallot, 2008; Eriksson and Eriksson, 2012; McCoy, 2014). On the other hand, mortification is an effective strategy in Western literature (Benoit, 1997a,b; Blaney et al., 2002; McCoy, 2014; Maiorescu, 2016; Ferguson et al., 2018).

Our study also found that political elites use religion to restore their reputation. Religious considerations can influence subjectivity in identifying candidates who can reflect community objectives and drive community divisiveness, according to several studies (Rakhmani, 2019; Khusna Amal, 2020; Oztas, 2020). Political elites use religiosity to establish a good reputation since it may affect all community groups' feelings, emotions, and sentiments (Porter, 2002; Freedman, 2009). Such a strategy was used by Prabowo who emphasized strong Islam (puritanism), while Jokowi highlighted Nusantara Islam, which echoes pluralism and moderate Islam in Indonesia.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous public figures echoed religious narratives, especially when the public criticized the government's handling plan (Gandasari and Dwidienawati, 2020; Mietzner, 2020). “Bismillah” and “InsyaAllah” appear frequently in public officials' social media posts about COVID-19. Religion calms the soul and has an impact on emotional wellness for persons who largely believe in it (Kowalczyk et al., 2020). People believe that, when they have nothing, God is their best chance.

This study found three of Benoit's five image restoration strategies, while the other two, including denial and mortification, were not found in the Indonesian public officials' posts on social media at all. In particular, the strategy of reducing offensiveness is the most widely used, and in the literature, this strategy is recognized as one of the most successful strategies. Meanwhile, we did not find any use of the mortification strategy, whereas in the Western literature on the image recovery strategy, it is used mainly in the context of private organizations.

The practical implication of this study is that public officials or public relations officials who represent them need to be careful in studying the crisis because it can have intensely dangerous consequences for the reputation of public officials. The results of this study will also become important literature to capture how public officials improve their reputation after they make a mistake. Moreover, this study was conducted in the context of a developing country, particularly Indonesia.

One of the main limitations of this study is that we did not measure the impact of public officials' image restoration strategies. This can be done by, for example, correlating with the number of comments and likes on certain types of strategies to test the relationship between the two. Sentiment analysis of comments on social media is also crucial to carry out to make it a proxy for measuring the success of using certain strategies and tactics. Future studies also need to consider the use of various combinations of sources, such as media reports and government press releases, to provide a more complete overview.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

We thank editors and external reviewers for giving the insightful comments.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Agley, J., and Xiao, Y. (2021). Misinformation about COVID-19: evidence for differential latent profiles and a strong association with trust in science. BMC Public Health 21, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-10103-x

Arandas, M. F., and Ling, L. Y. (2020). Indonesian crisis communication response after deliberate forest fires and transboundary haze. Malay. J. Commun. 36, 294–307. doi: 10.17576/JKMJC-2020-3604-18

Arendt, C., LaFleche, M., and Limperopulos, M.A. (2017). A qualitative meta-analysis of apologia, image repair, and crisis communication: Implications for theory and practice. Public Relat. Rev. 43, 517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.03.005

Avery, E. J., Lariscy, R. W., Kim, S., and Hocke, T. (2010). A quantitative review of crisis communication research in public relations from 1991 to 2009. Public Relat. Rev. 36, 190–192. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.01.001

Avraham, E., and Ketter, E. (2013). Marketing Destinations with Prolonged Negative Images: Towards a Theoretical Model. Tour. Geogr. 15, 145–164. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2011.647328

Ayoko, O. B., Ang, A. A., and Parry, K. (2017). Organizational crisis: emotions and contradictions in managing internal stakeholders. Int. J. Conflict Manage. 28, 617–643. doi: 10.1108/IJCMA-05-2016-0039

Ban, Z., and Lovari, A. (2021). Rethinking crisis dynamics from the perspective of online publics: A case study of Dolce and Gabbana's China crisis. Public Relat. Inquiry 10, 311–331. doi: 10.1177/2046147X211026854

Behrens, L. L., and Naylor, M. D. (2020). “We are alone in this battle”: a framework for a coordinated response to COVID-19 in nursing homes. J. Aging Soc. Policy 32, 316–322. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1773190

Bellström, P., Magnusson, M., Pettersson, J. S., and Thorén, C. (2016). Facebook usage in a local government: A content analysis of page owner posts and user posts. Transform. Govern. People Process Policy 10, 548–567. doi: 10.1108/TG-12-2015-0061

Benoit, W. L. (1995). Accounts, Excuses, and Apologies: A Theory of Image Restoration Strategies. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Benoit, W. L. (1997a). Hugh grant's image restoration discourse: An actor apologizes. Commun. Q. 45, 251–267. doi: 10.1080/01463379709370064

Benoit, W. L. (1997b). Image repair discourse and crisis communication. Public Relat. Rev. 23, 177–186. doi: 10.1016/S0363-8111(97)90023-0

Benoit, W. L. (2003). “Image restoration discourse and crisis communication,” in Responding to Crisis: A Rhetorical Approach to Crisis Communication. London, United Kingdom: Routledge

Benoit, W. L., and Czerwinski, A. (1997). A Critical Analysis Of USAir's Image Repair Discourse. Bus. Commun. Q. 60, 38–57. doi: 10.1177/108056999706000304

Blaney, J. R., Benoit, W. L., and Brazeal, L. M. (2002). Blowout!: Firestone's image restoration campaign. Public Relat. Rev. 28, 379–392. doi: 10.1016/S0363-8111(02)00163-7

Brennen, A. J. S., Simon, F. M., Howard, P. N., and Nielsen, R. K. (2020). Types, Sources, and Claims of COVID-19 Misinformation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1–13.

Carnevale, J. B., and Gangloff, K. A. (2022). A Mixed Blessing? CEOs' Moral Cleansing as an Alternative Explanation for Firms' Reparative Responses Following Misconduct. J. Bus. Ethics 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10551-022-05138-6

Chatterji, T., Roy, S., and Chatterjee, A. (2021). Global contagion and local response: the influence of centre–state relations and political culture in pandemic governance. Asian Pac. J. Public Admin. 43, 192–211. doi: 10.1080/23276665.2020.1870866

Chen, S., and Wang, X. (2021). “The communication model of negative public opinions of corporate based on two-layer network,” in 2nd International Conference on Control, Robotics and Intelligent System, CCRIS 2021. Shanghai University of Engineering Science, School of Manage. Studies, China: Association for Computing Machinery, 129–134.

Clementson, D. E. (2021). Effects of a “spin doctor” in crisis communication: a serial mediation model of identification and attitudes impacting behavioral intentions. Commun. Res. Rep. 38, 282–292. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2021.1961720

Clementson, D. E., and Beatty, M. J. (2021). Narratives as viable crisis response strategies: attribution of crisis responsibility, organizational attitudes, reputation, and storytelling. Commun. Stud. 72, 52–67. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2020.1807378

Coombs, T. W. (2006). The protective powers of crisis response strategies: managing reputational assets during a crisis. J. Promot. Manage. 12, 39–46. doi: 10.1300/J057v12n03_13

Coombs, W. T. (2004). West pharmaceutical's explosion: structuring crisis discourse knowledge. Public Relat. Rev. 30, 467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2004.08.007

Coombs, W. T. (2014). Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing, and Responding. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications

Corazza, L., Truant, E., Scagnelli, S. D., and Mio, C. (2020). Sustainability reporting after the Costa Concordia disaster: a multi-theory study on legitimacy, impression management and image restoration. Account. Audit. Account. J. 33, 1909–1941. doi: 10.1108/AAAJ-05-2018-3488

Dardis, F., and Haigh, M. M. (2009). Prescribing versus describing: Testing image restoration strategies in a crisis situation. Corporate Communs 14, 101–118. doi: 10.1108/13563280910931108

de Regt, A., Montecchi, M., and Lord Ferguson, S. (2019). A false image of health: how fake news and pseudo-facts spread in the health and beauty industry. J. Product Brand Manage. 29, 168–179. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-12-2018-2180

Demaline, C. J. (2021). Image repair during a U.S. Secur. Exchange Commission Invest. J. Corporate Account. Camp; Fin. 32, 164–174. doi: 10.1002/jcaf.22500

Deshpande, S., and Hitchon, J. C. (2002). Cause-related marketing ads in the light of negative news. J. Mass Commun. Q. 79, 905–926. doi: 10.1177/107769900207900409

Djalante, R. (2018). Review article: A systematic literature review of research trends and authorships on natural hazards, disasters, risk reduction and climate change in Indonesia. Nat. Haz. Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 1785–1810. doi: 10.5194/nhess-18-1785-2018

Djalante, R., Nurhidayah, L., Van Minh, H., Phuong, N. T. N., Mahendradhata, Y., Trias, A., et al. (2020). COVID-19 and ASEAN responses: comparative policy analysis. Progr. Disas. Sci. 8, 100129. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100129

Dror, A. A., Eisenbach, N., Taiber, S., Morozov, N. G., Mizrachi, M., Zigron, A., et al. (2020). Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 35, 775–779. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y

Dryhurst, S., Schneider, C. R., Kerr, J., Freeman, A. L. J., Recchia, G., van der Bles, A. M., et al. (2020). Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 7, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193

du Plessis, C. (2018). Social media crisis communication: enhancing a discourse of renewal through dialogic content. Public Relat. Rev. 44, 829–838. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.10.003

Enns, A., Pinto, A., Venugopal, J., Grywacheski, V., Gheorghe, M., Kakkar, T., et al. (2020). Evidence-informed policy brief substance use and related harms in the context of covid-19: a conceptual model. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prevent. Canada 40, 342–349. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.40.11/12.03

Erickson, S. L., Stone, M., Hanson, T. A., Tolifson, A., Ngongoni, N., Kalthoff, J., et al. (2017). Shareholder value and crisis communication patterns: An ananlysis of the ford and firestone tire recall. Acad. Strat. Manage. J. 16, 32–53.

Eriksson, G., and Eriksson, M. (2012). Managing political crisis: An interactional approach to “image repair”. J. Commun. Manage. 16, 264–279. doi: 10.1108/13632541211245776

Falkheimer, J., and Heide, M. (2015). Trust and brand recovery campaigns in crisis: findus nordic and the horsemeat scandal. Int. J. Strategic Commun. 9, 134–147. doi: 10.1080/1553118X.2015.1008636

Ferguson, D. P., Wallace, J. D., and Chandler, R. C. (2018). Hierarchical consistency of strategies in image repair theory: PR practitioners' perceptions of effective and preferred crisis communication strategies. J. Public Relat. Res. 30, 251–272. doi: 10.1080/1062726X.2018.1545129

Fishman, D. A. (1999). Valujet flight 592: Crisis communication theory blended and extended. Commun. Q. 47, 345–375. doi: 10.1080/01463379909385567

Fortunato, J. A. (2008). Restoring a reputation: The Duke University lacrosse scandal. Public Relat. Rev. 34, 116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2008.03.006

Freedman, A. L. (2009). Political Viability, Contestation and Power: Islam and Politics in Indonesia and Malaysia. Polit. Relig. 2, 100–127. doi: 10.1017/S1755048309000054

French, S. L., and Holden, T. Q. (2012). Positive organizational behavior: a buffer for bad news. Bus. Commun. Q. 75, 208–220. doi: 10.1177/1080569912441823

Gai, L. (2016). “Managing crisis overseas: an explorative analysis of apple's warranty crisis communication in China,” in Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science. University of North Texas, Denton, TX, United States: Springer Nature, 825–830.

Gandasari, D., and Dwidienawati, D. (2020). Content analysis of social and economic issues in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon 6, Gandasari D., and Dwidienawati D., (2020). Content analysis of social and economic issues in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon 6. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05599

Gribas, J., DiSanza, J. R., Hartman, K. L., Carr, D. J., and Legge, N. J. (2021). Exploring the effectiveness of image repair tactics: comparison of U.S., and Middle Eastern audiences. Commun. Res. Rep. 38, 150–160. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2021.1909550

Griffin-Padgett, D. R., and Allison, D. (2010). Making a case for restorative rhetoric: Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and mayor Ray Nagin's response to disaster. Commun. Monogr. 77, 376–392. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2010.502536

Ha, J. H., and Boynton, L. (2014). Has Crisis Communication Been Studied Using an Interdisciplinary Approach? A 20-Year Content Analysis of Communication Journals. Int. J. Strat. Commun. 8, 29–44. doi: 10.1080/1553118X.2013.850694

Hanna, C., and Morton, J. T. (2020). Urban Meyer Needs an Image Repair Coach. J. Global Sport Manage. 5, 167–183. doi: 10.1080/24704067.2019.1604076

Heppell, T. (2021). The British Labour Party and the antisemitism crisis: Jeremy Corbyn and image repair theory. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat. 23, 645–662. doi: 10.1177/13691481211015920

Herrero, J. C., and Marfil Medina, J. P. (2016). Crisis communication in politics: Forgiveness as image restoration tool | La comunicación de crisis en política: El perdón como herramienta de restauración de imagen. Estudios Sobre el Mensaje Periodistico 22, 361–373. doi: 10.5209/rev_ESMP.2016.v22.n1.52603

Holdener, M., and Kauffman, J. (2014). Getting out of the doghouse: The image repair strategies of Michael Vick. Public Relat. Rev. 40, 92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.11.006

Holtzhausen, D. R., and Roberts, G. F. (2009). An investigation into the role of image repair theory in strategic conflict management. J. Public Relat. Res. 21, 165–186. doi: 10.1080/10627260802557431

Hwang, Y. N., Suh, S. Y., Kim, Y., and Yoo, J.-. W. (2019). Comparative analysis of perception of organization–public relationships in Chinese and Korean newspapers. Soc. Behav. Pers. 47, 1–8. doi: 10.2224/sbp.7854

Im, T., and Campbell, J. W. (2020). Coordination, incentives, and persuasion: South korea's comprehensive approach to covid-19 containment*. Kor. J. Policy Stud. 35, 119–139. doi: 10.52372/kjps35306

Kagias, P., Cheliatsidou, A., Garefalakis, A., Azibi, J., and Sariannidis, N. (2021). The fraud triangle—an alternative approach. J. Fin. Crime. 29, 908–924. doi: 10.1108/JFC-07-2021-0159

Katadata (2021). Kepercayaan Masyarakat Menurun Karena Kebijakan Covid-19 Berubah-Ubah - Nasional Katadata.co.id, Katadata. Available online at: https://katadata.co.id/maesaroh/berita/618afc8f4a161/kepercayaan-masyarakat-menurun-karena-kebijakan-covid-19-berubah-ubah (accessed on December 2, 2022).

Katadata (2022). Pengguna Instagram di Indonesia Bertambah 3,9 Juta pada Kuartal IV-2021, 2012. Available online at: https://databoks.katadata.co.id/datapublish/2022/01/10/pengguna-instagram-di-indonesia-bertambah-39-juta-pada-kuartal-iv-2021 (accessed on September 20, 2022).

Kauffman, J. (2012). Hooray for Hollywood? The 2011 Golden Globes and Ricky Gervais' image repair strategies. Public Relat. Rev. 38, 46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2011.09.003

Khusna Amal, M. (2020). Explaining islamic populism in Southeast Asia: An Indonesian muslim intellectuals perspective. J. Crit. Rev. 7, 583–588. doi: 10.31838/jcr.07.05.121

Kim, S., Avery, E. J., and Lariscy, R. W. (2009). Are crisis communicators practicing what we preach?: An evaluation of crisis response strategy analyzed in public relations research from 1991 to 2009. Public Relat. Rev. 35, 446–448. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.08.002

Kim, S., Avery, E. J., and Lariscy, R. W. (2011). Reputation repair at the expense of providing instructing and adjusting information following crises. Int. J. Strat. Commun. 5, 183–199. doi: 10.1080/1553118X.2011.566903

Kowalczyk, O., Roszkowski, K., Montane, X., Pawliszak, W., Tylkowski, B., Bajek, A., et al. (2020). Religion and Faith Perception in a Pandemic of COVID-19. J. Relig. Health 59, 2671–2677. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01088-3

Lancaster, K., and Boyd, J. (2015). Redefinition, differentiation, and the farm animal welfare debate. J. Applied Commun. Res. 43, 185–202. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2015.1019541

Le, P. D., Teo, H. X., Pang, A., Li, Y., and Goh, C.-. Q. (2019). When is silence golden? The use of strategic silence in crisis communication. Corp. Commun. 24, 162–178. doi: 10.1108/CCIJ-10-2018-0108

Legg, K. L. (2009). Religious celebrity: An analysis of image repair discourse. J. Public Relat. Res. 21, 240–250. doi: 10.1080/10627260802557621

Lin, Y. (2021). Legitimation strategies in corporate discourse: A comparison of UK and Chinese corporate social responsibility reports. J. Pragmatics 177, 157–169. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2021.02.009

Liu, B. F., Iles, I. A., and Herovic, E. (2020). Leadership under fire: how governments manage crisis communication. Commun. Stud. 71, 128–147. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2019.1683593

Maiorescu, R. D. (2016). Deutsche Telekom's spying scandal: An international application of the image repair discourse. Public Relat. Rev. 42, 673–678. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.10.005

Marcoux, J.-. M, Gomez, O. C. C., and Létourneau, L. (2013). The inclusion of nonsafety criteria within the regulatory framework of agricultural biotechnology: exploring factors that are likely to influence policy transfer. Rev. of Policy Res. 30, 657–684. doi: 10.1111/ropr.12053

McCoy, M. (2014). Reputational threat and image repair strategies: northern ireland water's crisis communication in a freeze/thaw incident. J. Nonprof. Public Sect. Market. 26, 99–126. doi: 10.1080/10495142.2013.872508

Mietzner, M. (2020). Populist anti-scientism, religious polarisation, and institutionalised corruption: how indonesia's democratic decline shaped its COVID-19 response. J. Curr. Southeast Asian Affairs 39, 227–249. doi: 10.1177/1868103420935561

Morgan, V., Zauskova, A., and Janoskova, K. (2021). Pervasive misinformation, covid-19 vaccine hesitancy, and lack of trust in science. Rev. of Contemp. Philos. 20, 128–138. doi: 10.22381/RCP2020218

Nazione, S., and Perrault, E. K. (2019). An Empirical Test of Image Restoration Theory and Best Practice Suggestions Within the Context of Social Mediated Crisis Communication. Corp. Reput. Rev. 22, 134–143. doi: 10.1057/s41299-019-00064-2

O'Connell, B., De Lange, P., Stoner, G., and Sangster, A. (2016). Strategic manoeuvres and impression management: communication approaches in the case of a crisis event. Bus. History 58, 903–924. doi: 10.1080/00076791.2015.1128896

OECD (2020). Regulatory Quality and COVID-19: Managing the Risks and Supporting the Recovery. Washington.

Oztas, B. (2020). Islamic populism: Promises and limitations. J. Interdiscip. Middle East. Stud. 6, 103–129. doi: 10.26351/JIMES/6-2/1

Page, T. G. (2019). Beyond attribution: Building new measures to explain the reputation threat posed by crisis. Public Relat. Rev. 45, 138–152. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.10.002

Pollach, I., Ravazzani, S., and Maier, C. D. (2022). Organizational guilt management: a paradox perspective. Group Organ. Manage. 47, 487–529. doi: 10.1177/10596011211015461

Porter, D. J. (2002). Citizen participation through mobilization and the rise of political Islam in Indonesia. Pacific Rev. 15, 201–224. doi: 10.1080/09512740210131040

Pratiwi, M., Andarini, R. S., Setiyowati, R., and Santoso, A. D. (2022). Visualisation of image restoration for Indonesian public officials during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Indones. J. Commun. Stud. 6, 885–902. doi: 10.25139/jsk.v6i3.4971

Puri, N., Coomes, E. A., Haghbayan, H., and Gunaratne, K. (2020). Social media and vaccine hesitancy: new updates for the era of COVID-19 and globalized infectious diseases. Human Vaccines Immunother. 16, 2586–2593. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1780846

Rakhmani, I. (2019). The Personal is Political: Gendered Morality in Indonesia's Halal Consumerism. TRaNS: Trans-Reg. Natl. Stud. Southeast Asia 7, 291–312. doi: 10.1017/trn.2019.2

Rogers, R. K., Dillard, J., and Yuthas, K. (2005). The accounting profession: Substantive change and/or image management. J. Bus. Ethics 58, 159–176. doi: 10.1007/s10551-005-1401-z

Sang, S., Lee, J. D., and Lee, J. (2009). E-government adoption in ASEAN: The case of Cambodia. Internet Res. 19, 517–534. doi: 10.1108/10662240910998869

Sawalha, I. H. (2020). After the crisis: repairing a corporate image. J. Bus. Strat. 41, 69–80. doi: 10.1108/JBS-04-2019-0075

Schlægera, J. (2013). E-government in China: Technology, power and local government reform, E-Government in China: Technology, Power and Local Government Reform. Sichuan University, China: Taylor and Francis.

Sellnow, T. L., Ulmer, R. R., and Snider, M. (1998). The compatibility of corrective action in organizational crisis communication. Int. J. Phytoremediation 46, 60–74. doi: 10.1080/01463379809370084

Sheldon, C. A., and Sallot, L. M. (2008). Image repair in politics: testing effects of communication strategy and performance history in a faux pas. J. Public Relat. Res. 21, 25–50. doi: 10.1080/10627260802520496

Siddiqi, S., and Koerber, D. (2020). The anatomy of a national crisis: The Canadian Federal Government's response to the 2015 Kurdi refugee case. Can. J. Commun. 45, 411–436. doi: 10.22230/cjc.2020v45n3a3585

Statista (2021). Leading countries based on number of Twitter users as of July 2021(in millions), Statista. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/242606/number-of-active-twitter-users-in-selected-countries/ (accessed on 21 October 2021).

Tashiro, A., and Shaw, R. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic response in Japan: What is behind the initial flattening of the curve?. Sustainability (Switzerland) 12, 5250. doi: 10.3390/su12135250

Tokakis, V., Polychroniou, P., and Boustras, G. (2019). Crisis management in public administration: The three phases model for safety incidents. Saf. Sci. 113, 37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2018.11.013

Triantafillidou, A., and Yannas, P. (2020). Social media crisis communication in racially charged crises: Exploring the effects of social media and image restoration strategies. Comput. Human Behav. 106. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106269

Ujunwa Melugbo, D., and Amara Onwuka, I. (2020). Demographic variations in public views of response to and management of the COVID-19 pandemic: Examining the perceived roles of public/social policies, government emergency powers and citizen participation. Balkan Soc. Sci. Rev. 16, 279–299. doi: 10.46763/BSSR2016279um

Ulmer, R. R., Seeger, M. W., and Sellnow, T. L. (2007). Post-crisis communication and renewal: Expanding the parameters of post-crisis discourse. Public Relat. Rev. 33, 130–134. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2006.11.015

Valdebenito, M. S. (2013). Image repair discourse of Chilean companies facing a scandal. Discourse Commun. 7, 95–115. doi: 10.1177/1750481312466474

Verhoeven, P., Tench, R., Zerfass, A., Moreno, A., and Verči,č, D. (2014). Crisis? What crisis?. How European professionals handle crises and crisis communication. Public Relat. Rev. 40, 107–109. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.10.010

Volo, S., and Irimiás, A. (2021). Instagram: Visual methods in tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 91, 103098. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.103098

Wang, S. S., Goh, J. R., Sornette, D., Wang, H., and Yang, E. Y. (2021). Government support for SMEs in response to COVID-19: theoretical model using Wang transform. China Fin. Rev. Int. 11, 406–433. doi: 10.1108/CFRI-05-2021-0088

Wong, I. A., Ou, J., and Wilson, A. (2021). Evolution of hoteliers' organizational crisis communication in the time of mega disruption. Tour. Manage. 84, 104257. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104257

Yamazaki, J. W. (2005). Japanese Apologies for World War II: A Rhetorical Study, Japanese Apologies for World War II: A Rhetorical Study. Department of International Studies, Oakland University, Rochester, MI, United States: Routledge.

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study Research: Design and Methods (2nd Edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Zakaria, D., and Hira, R. H. (2020). Pandemi Covid-19: Flattening The Curve, Kebijakan dan Peraturan. Vox Populi 3, 1. doi: 10.24252/vp.v3i1.14077

Keywords: image restoration theory, Indonesia, public officials, COVID-19, erroneous claim

Citation: Andarini RS, Pratiwi M, Setiyowati R and Santoso AD (2023) Indonesian public officials after erroneous statements about COVID-19: An application of image restoration theory. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:1062237. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.1062237

Received: 05 October 2022; Accepted: 19 December 2022;

Published: 12 January 2023.

Edited by:

Hazel Jovita, Mindanao State University, PhilippinesReviewed by:

Tayden Fung Chan, University of Macau, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Andarini, Pratiwi, Setiyowati and Santoso. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anang Dwi Santoso,  YW5hbmdkd2lAZmlzaXAudW5zcmkuYWMuaWQ=

YW5hbmdkd2lAZmlzaXAudW5zcmkuYWMuaWQ=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.