95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 15 December 2022

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.1057051

This article is part of the Research Topic Party Leader Selection in Europe: Concepts, Processes and Outcomes View all 5 articles

This study applies process-tracing methods to understand the 2019 leadership selection process in the Belgian French-speaking liberal party, MR, which is the oldest and second largest party in French-speaking Belgium. We triangulate a variety of sources to assemble a rich qualitative material that is used to contrast the formal rules and outcome of the race to the actual process. We show that the gatekeepers were not the ones ascribed in the statutes, that formal rules were bent to fit the profile of the race, and that the very nature of the race was much closer to a coronation than the results may suggest. We also uncover mechanisms through which party actors, especially the incumbent leader as steering agent, informally influence the process to the desired outcome, with the race being played prior to the validation of the candidacies. This analysis puts focuses on when and how key actors use their informal influence to weigh the process and influence the outcome of leadership races.

Who leads a party has important political consequences (Pilet and Cross, 2014; So, 2021). Furthermore, the role of party leaders has expanded in the last decades (Passarelli, 2015). It is true also in Belgium: party leaders are the most powerful party actors and the most powerful actors in Belgian politics in general—federal and regional prime ministers aside. Therefore, selecting a party leader is a key moment for a political party, and understanding the leadership selection process is crucial.

Existing research has predominantly focused on two main dimensions of leadership selection processes: their degree of inclusiveness and centralization (Kenig, 2009a,b; Cross and Blais, 2012; Cross and Pilet, 2015; Kenig et al., 2015; Sandri et al., 2015a; Musella, 2017; Cross, 2018). These studies emphasize a trend toward more inclusive and centralized selection procedures over time (LeDuc, 2001; Cross and Blais, 2012), contributing to the debate on intra-party democratization and organizational change. Beyond a description of selection methods used by parties, they also investigate the factors driving change over time (Barnea and Rahat, 2007; Wauters, 2014; Chiru et al., 2015). They stress the importance of the personalization of politics, demand for more inclusive democracy, participation, and transparency, decline in membership levels, diffusion across parties, electoral defeat, and change in the dominant faction within the party. Research has also focused on the political consequences of leadership selection methods at the system level (Pedersen and Schumacher, 2015; Somer-Topcu, 2017) and at the party level (Rahat et al., 2008): who is selected (O'Neill and Stewart, 2009; Sandri et al., 2015b; Wauters and Pilet, 2015), who participates in these elections (Cross et al., 2016), and their degree of competitiveness (Kenig, 2009a; Kenig et al., 2015). One of the implications is that leadership selection processes are often approached by proxy, that is by looking at the outcome of the races (Ennser-Jedenastik and Schumacher, 2015; Vandeleene and Van Haute, 2021).

However, surprisingly little research has been conducted on actual intra-party processes. When they do, they tend to apply theoretical frameworks from electoral studies. More specifically, studies have focused on campaigns, the drivers of participation (Cross et al., 2016), and the voting behavior of the selectorates (Wauters et al., 2020). They have stressed that selectorates are influenced by the candidate's personality, electability, or policy positions (Vandeleene et al., 2020).

Much less research is focused on the process from an organizational perspective, especially beyond the “official” story based on formal rules and party statutes (Scarrow et al., 2017). Yet, parties have a lot of leeway in how they implement leadership selection rules during actual processes. The official story does not always help in understanding how seemingly inclusive rules, such as one member one vote system (OMOV), applied in most Belgian parties, often lead to controlled, non-competitive races and coronations (Allern and Karlsen, 2014; Ennser-Jedenastik and Müller, 2014; Pilet and Wauters, 2014). Understanding leadership selection processes—in Belgium and elsewhere—calls for a more qualitative study that would go beyond the official story of leadership races.

This is what this study intends to do. It applies process-tracing methods to understand when and how party actors use their informal influence to weigh the process and influence the outcome of a leadership race, using as a case study the 2019 leadership selection in the Belgian French-speaking liberal party (Mouvement Réformateur—MR). We chose to focus not only on a mainstream party but also on a race that presents unique features. The MR is a central actor in Belgian politics: It is the party with the oldest roots and the second largest party in French-speaking Belgium, frequently included in coalition governments at the federal and regional levels. It is also characterized by informality and factionalism, which make leadership elections particularly sensitive. Specifically, focusing on the 2019 leadership race allows us to gain insights into our research question both in the context of coronation and competition.

Process tracing is well-suited for in-depth case studies and qualitative analyses of processes (Mahoney, 2012). Because it implies acquiring fine knowledge of processes, the method articulates theoretical expectations of real-world events and processes (Collier, 2011; Bennett and Checkel, 2014). The method is very effective when there is limited theoretical knowledge or when the theory is incomplete and cannot fully enlighten the process under study (Gerring, 2004). Process tracing also works best with intriguing, often heavily mediatized outcomes with a clear start and end date. In this light, leadership races are good contenders to apply process-tracing methods, due to the shortcomings of existing theories to understand the outcome of races understood as intra-party decision-making processes under the spotlight.

In our case, we adopt an abductive process-tracing logic. Regarding when actors introduce informality in the process, our data collection was initially guided by the sequential approach proposed by Aylott and Bolin (2021). They identify three crucial phases in leadership races. First, the gatekeeping phase consists of the formal rules that structure the process. Second, the preparation phase refers to the moment when aspiring candidates and various party factions contemplate the idea of running or weighing the process. The last phase, decision, is about the contest itself. We contrast the first and last phases (rules and outcome) to the actual process to highlight the added value of analyzing the latter. Regarding the how question, our data collection focused on various party actors, especially the potential steering agent and its role in managing the process, as recommended by Aylott and Bolin (2017). To do so, we triangulated various sources—internal party documents, media coverage, and interviews—which are independent of each other (refer to Section 2).

Our analysis proceeds in two steps. First, the cross-checking of these various sources allows us to get a fine-grained view of the process, its sequences, its actors and their roles (refer to Section 3). We contrast the gatekeeping and decision phases to the preparation phase at the core of the selection process. Second, we analyze the mechanisms at play. We identify the main structures and key actors involved, including the steering agent, and their interactions.

Second, following a theory-building approach, we then infer general theoretical and conceptual insights gained from the analysis and discuss the transposition of our theoretical findings to other contexts (refer to Section 4 and Conclusion). Looking at when key actors use their informal influence to weigh the process, our analysis nuances Aylott and Bolin's sequential approach. We underline the limitations of a static framework and show that the preparation phase can unfold in iterative ways. We also highlight how key actors use their informal influence to weigh the process. We associate each sequence of the actual process with a mechanism—a central concept in process tracing used as a tool to open the black box of the process under study (Hedström, 2008). For each sequence, we investigate various types of interactions between the main agents (internal party actors) and structures (intra-party organs and rules) involved in the process. Among key actors, we put a specific emphasis on the role of the steering agent (Aylott and Bolin, 2017; Beyer, 2019). Steering agents have a key role in leadership selection processes. They are central party actors who manage, steer, and adapt the process in a specific direction. By steering, we mean “subject-led, intentional, and goal-directed attempts to influence social processes,” even though the steering does not always have the expected effect (Beyer, 2019). The analysis of these interactions leads to identifying the trajectory, or mechanism, through which the agent or structure (x) produces an effect on another agent or structure (y) (Beach and Pedersen, 2013). This focus on mechanisms at play for each sequence of the process goes beyond the comparative framework, as suggested by Aylott and Bolin (2017). It allows moving from a descriptive to an analytical and theoretical ambition, introducing a causal analysis of the case study.

The case study under investigation is the 2019 leadership selection race of the Belgian French-speaking liberal party (Mouvement Réformateur—MR).

The MR is an interesting party to analyze to disentangle the dynamics of leadership processes. The MR celebrated its 175th anniversary in 2021, making it the party with the oldest roots in Belgium (Delwit, 2017). It is also one of the major parties in Belgium: It has mainly occupied the second place in the party system on the francophone side, with the short exception of 2007 where it ranked first (Delwit, 2021). Yet, the party is characterized by a low level of institutionalization compared to the other Belgian mainstream parties due to its roots as a cadre party born in parliament. The leader and a small group of party elites hold the power, and informality plays an important role in the decision-making. The party statutes of 2005 (applied for the 2019 race) are spectacularly short and leave room for interpretation. This high level of informality makes it more prone to deviate from formal rules during the actual race. Similar to many other Western European liberal parties, the MR's internal politics is characterized by complex and highly competitive power dynamics (Close and Legein, Forthcoming). Two personalized factions oppose each other: the Gol-Reynders, traditionally associated with the right of the party, and the Michel father-Michel son, historically associated with more social liberalism albeit a recent shift to the right (Luypaert and Legein, Forthcoming). Informality and factionalism make leadership races an important juncture in the party's life.

The 2019 race is an interesting case because it combined two stories. What was initially planned as a coronation, typical of most leadership races in the MR and Belgium in general, turned into a competition between multiple candidates. This makes it a unique opportunity to unveil with one single case study, the mechanisms at play during both a coronation and a competition.

Most Belgian parties have indeed moved toward more inclusive leadership selection processes in the last decades, shifting power from party delegates to a one member, one vote system (OMOV) of direct leader election (Legein and Van Haute, 2021). Nevertheless, leadership contests are usually not very competitive. Most contests count only one candidate, and contested contests see an average 28.9% margin between the top two finishers. This pattern applies to the MR (Table 1). Since the introduction of the OMOV system, only one out of the 10 elections was contested; all the other races saw the coronation of a candidate nominated by the party apparatus. Only three races have featured two or more candidates. The 2019 race is an outlier in this respect: Two rounds were needed to crown the winner, Georges-Louis Bouchez, with a competitive score (61.9%).

Using the 2019 leadership race in the MR as a case study, we combine a variety of sources to trace back the process that leads Bouchez, the candidate of the dominant faction, to win the race. First, we analyze internal party documents (party statutes and leadership election rules) to get to the official story and to identify the main structures involved in the process. Second, we systematically review the media coverage of the race in the main outlets in French-speaking Belgium: the two main newspapers, La Libre (conservative political leaning) and Le Soir (progressive political leaning), and the two main TV channels, RTBF (public service broadcasting) and RTL (commercially run). This allows us to identify the sequences of the preparation phase and the main actors involved by relying on a great diversity of sources. Third, we conducted 12 interviews with key actors who were all involved in the 2019 leadership race. We sampled for range and targeted relevant sub-categories of individuals occupying specific functions in the party and/or during the race, making sure to cover all sub-categories: the candidates running for elections, members of decision-making bodies within the party, and campaign organizers. We adopted a sequential interviewing strategy, progressively identifying these relevant individuals and adapting our questionnaires to each sub-category. In doing so, each interview provided us with an increasingly accurate understanding of the leadership contest under study. We aimed for saturation, which was achieved already after interview 11. This strategy is particularly well-suited when asking how and why questions about processes, as we do here (Small, 2009). Details about the interviewees are presented in Table 2. In our analysis, each interviewee is referred to using generic labels (e.g., I3 stands for Interviewee 3 in Table 2) to allow for seamless reading of the article and to minimize any reading bias.

Interviews were conducted between August and October 2021. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, some interviews took place online and others face-to-face. Interviews lasted on average 50 min. All interviews were conducted in French and were recorded and transcribed by the authors or by trained job students. Elite interviewing constitutes a rich source to gather information on their perceptions of the process and interactions with other actors (Ritchie and Lewis, 2003). It brings additional light to more informal dimensions of the process and fills the gaps of the official story if triangulated with other sources (Tansey, 2007). We first asked respondents to contextualize the contest and the role they played in it: How were candidates selected in practice compared to party statutes? Which formal or informal role the interviewees were playing in the contest? We then discussed the three phases in detail. We asked about the internal campaign, the power struggles, and the role of certain party actors, to identify the steering agent. The interview material is extremely rich in details on power dynamics, interpersonal relationships, and informal actions taken by key figures of the party. This willingness to talk was possible due to a combination of trust building between the research team and the party, a possible indifference toward the actual output that would come out of the interviews, and the liberal party culture that lead most interviewees to put their individual ego above the party as a collective.

In this section, we differentiate between three sequences. We start with the gatekeeping phase based on the formal procedure as described in the party statutes and internal documents. We then present a longer account of the preparation phase, where we distinguish between the initial plan of coronation and the actual competitive race. Finally, we present the campaign and the outcome of the process.

While the party does not apply any nomination requirements, the formal candidacy requirements are relatively restrictive. Only members of the General Committee, an intermediate body between the National Executive Committee and the Party Congress, composed of party elites and a limited number of members, can run for election (Mouvement Réformateur (MR), 2005). The members of the General Committee are designated by the Council and the National Executive Committee, who therefore holds the reins of who is eligible for the position. Candidacies must be addressed to the Conciliation and Arbitration Council, who is responsible for validating them or not and is therefore in the position to further strengthen or relax eligibility requirements.

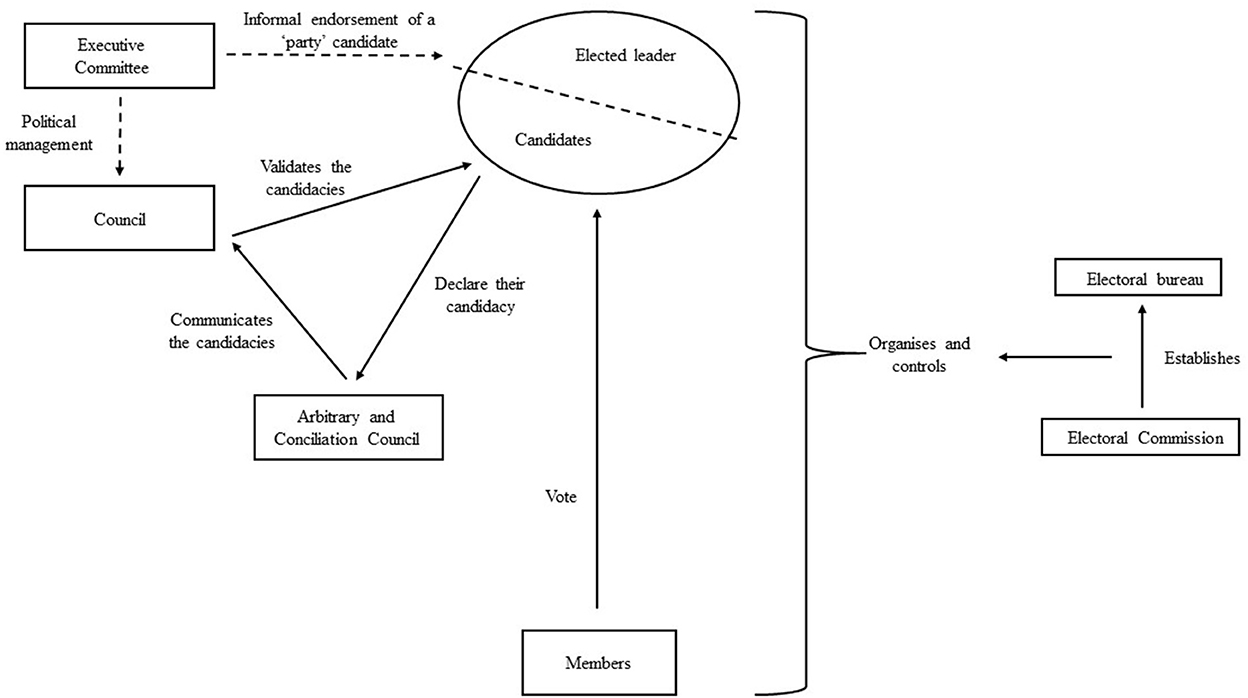

Once candidacies are validated, the actual process is managed by the Electoral Commission (Mouvement Réformateur (MR), 2005, 2019), which designates an Electoral Bureau (five members) in charge of the practical organization of the elections (Figure 1). A president and a vice-president are designated among the members of the Electoral Bureau. The president shall adopt important decisions of the Bureau once they have been passed by an absolute majority.

Figure 1. Formal leadership selection procedure. Authors' own design. Plain lines denote a formal interaction as planned in the party statutes; dotted lines denote informal interactions.

The decision phase is rather straightforward according to party statutes. Article 12 (Mouvement Réformateur (MR), 2005) stipulates that the party leader is elected by universal suffrage of the party members (OMOV), using membership lists produced by the party secretariat. The vote is a mail-in secret ballot and a simple majority. A second round is organized with the top-two candidates if none of the candidates gets a majority of the votes in the first round. During the decision phase, the bureau oversees the final counting of votes. This last phase is less formalized in the party statutes but has been detailed in an internal document specifically dedicated to the 2019 race (Mouvement Réformateur (MR), 2019).

It is striking to see that most of the major party bodies do not have a direct role in the process. The Party Congress, the main party body composed of delegates, does not have any say. The Council, a large semi-executive body composed of the party leader, governmental leader, vice-presidents, 60 members, and sovereign between two Congresses, has an only indirect say on candidacies by designating the members of the General Committee. The same applies to the real executive body, the National Executive Committee, composed of the party leader, the governmental leader, and the vice presidents of the party. This means that the party leaders are not formally granted a large role in the process. Note that, to accommodate the dual factionalism that characterizes the MR, the day-to-day leadership of the party is carried out by two people when the party is in government: the party leader and the governmental leader. In Belgium, each party in the coalition counts a vice-Prime Minister in the government. The status of MR government leader is usually given to the latter. Conversely, the General Committee is an important structure to belong to as it is a prerequisite for candidacy to the race, but it only exists on paper.

In February 2019, the incumbent leader, close to the Michel faction, announced at the Party Council that he would lead the party list for the upcoming European elections in May 2019 and that he consequently would resign from the party leadership. Using his dominant position in the Council, Charles Michel, then Prime Minister of a minority caretaker government, easily persuaded the Council that organizing a race before the elections would be too disruptive. The Council agreed to postpone the leadership race after the elections, and Charles Michel took over the party leadership (Table 1).

The party lost ground at the 2019 federal, regional, and European elections in May. Negotiations to form a government started just before the summer and were expected to be complicated, especially at the federal level. Rumors spread that Charles Michel would covet the post of president of the European Council next December. In the following weeks, Didier Reynders, leader of the opposing faction in the party, was announced as a candidate to become the next General Secretary of the Council of Europe (La Libre, 26 August 2019). Three key figures of the party were therefore announced to be leaving the party. The timing was not ideal, as the party needed a leader to conduct the governmental negotiations. Several options were then put forward by the General Secretary to the Council, to ensure a stable leadership during the governmental negotiations (I11): (1) the option of Michel cumulating the presidency of the European Council and the party leadership was put forward but quickly rejected as unrealistic; (2) the appointment of a president ad interim, which was also rejected as too weak; and (3) the organization of internal elections, which were negotiated as the only acceptable solution. This justified “the transition to another internal party sequence” (I11).

In June, we see the first reports in the media about the game of musical chairs that awaits the MR for the upcoming leadership election, with the names of two prominent figures close to Charles Michel circulating. The competition is still very open given the uncertainties about potential ministerial posts to be allocated if the party joins the federal and/or regional governments. This could reopen the war between the two main factions of the party. We see the first signs of internal consultations between the two factional leaders to pacify the party upon their departure and plan the race. In a powerful informal pre-selection phase, the outgoing leader Charles Michel (and the Council) endorsed Willy Borsus as the candidate for the party leadership. Jean-Luc Crucke, supported by the Gol-Reynders faction, would then be granted the role of MR leader of the Walloon government (I3). Based on that internal agreement between the two factions, the election was thus supposed to be a classic coronation. Borsus would have been the only declared candidate.

Nevertheless, the uncertainties were important and the tensions between factions were still alive. Consequently, Charles Michel anticipated potential issues with the planned coronation and placed his pawns for an alternative strategy. On 8 July, Georges-Louis Bouchez was co-opted as a senator based on a proposal by Charles Michel (Le Soir, 08 July 2019). Strategically, it makes Bouchez a member of the General Committee, thereby eligible as a potential candidate for the leadership race.

Big tensions arose within the party about Michel's date of departure from the party leadership. Michel wanted to stay until December. On 22 July, an anonymous putsch was attempted in the media by six key figures to make him leave more quickly. Two prominent figures of the progressive wing of the party are suspected to be behind the move. The putsch did not work and strengthened Michel who saw all the party figures publicly affirming allegiance and supporting him as party leader.

In late August, the governmental negotiations favorably developed for the MR at the federal and regional levels. Several key figures quickly understood that Borsus did not want the party leadership but would prefer the role of leader of the Walloon government (I3; I6). Multiple ministerial portfolios would also be available, which would retain many of the party figures in government responsibilities. Holders of ministerial portfolios had to explicitly renounce cumulation with the function of the party leader (I6). Bouchez saw an opportunity to position himself as a candidate: “I had understood that those who could impose themselves naturally would be occupied by ministerial positions (…) it opens the game (…). The party suffered an electoral defeat, especially among the lower classes and the youth. And I am young and succeeded in a city sociologically characterized by lower classes” (I2). Bouchez started contacting party elites and persuaded Charles Michel to support his candidacy. Michel informally endorsed him, once again playing the informal role of steering agent after various consultations. It was a crucial step in the informal preparation phase: “the friendship that I developed with him [Michel] (…) was helpful in (…) acquiring respectability in the eyes of some who saw me as a young outsider. (…) The crucial but decisive step was the underwater round that I made to gather support” (I2, confirmed by I8). This capacity to ensure endorsements was later seen as an asset by key figures (I2).

Borsus' choice of a ministerial portfolio was confirmed in mid-September. This turned the leadership race into an open election that was not previously planned. Michel announced his departure from the party leadership to the National Executive. Interviews reveal the role of a few key figures (Charles Michel as a leader, Valentine Delwart and Jean-Philippe Rousseau as party secretaries) in planning an electoral calendar (I8; I9), to be validated by the Electoral Bureau (I11).

On 27 September, Denis Ducarme, a former key figure of the party whose influence at the top was on the decline, officially declared his candidacy. On 3 October, it was Bouchez's turn with the support of Michel and the party apparatus, not warm about a Ducarme candidacy: “It shouldn't be a secret because when you want to make a big machine work, it is also the responsibility of someone who assumed the role of party leader not to leave the house in a mess (…) the sequence of announcements did not leave space for doubts and informal supports quickly became official from a number of key figures in the party” (I8, confirmed by I3, I5, and I9).

Ducarme, therefore, became the candidate of the grassroots. These were the two expected contenders. In the following week, three second-tier figures of the party (Christine Defraigne, Philippe Goffin, Clémentine Barzin) and two rank-and-file members also announced that they would run.

All seven candidacies were addressed to the Conciliation and Arbitration Council. The Council rejected the two candidacies from rank-and-file members who were not members of the General Committee. However, an exception to this rule was made to allow Christine Defraigne to run although she was not a member of the General Committee either (La Libre, 3 October 2019). Defraigne had formally alerted the Electoral Bureau about the issue of eligibility (I5). She also points out that she informally wrote a “bitter” letter to Michel alerting him to the situation and expressing her displeasure that “he was not very sympathetic to [her], who had helped him a lot [in the past]” (I5). The Electoral Bureau made a proposal to the Conciliation and Arbitration Council—who validated it—to adapt and bend the rules (I4). The Council thus validated five candidacies (Barzin, Bouchez, Defraigne, Ducarme, and Goffin). Those who participated in validating this exception justify it by saying that the decision follows the esprit de la loi: “we are used to get candidacies that do not meet the eligibility criteria. Here, the case was more complicated, with Christine Defraigne (…) We followed the statutes because the Council has the final say, and the statutes referred to a body that did not exist anymore, the General Committee, and that the Conciliation and Arbitration Council decided to consider the party Council as the General Committee, which allowed us to reconcile party statutes and reality to ensure that internal democracy is respected” (I8; confirmed by I9).

They did it knowing that it could potentially backfire: “these things get more and more professional and this time, we even faced interventions from lawyers. The candidates wanted to protect themselves because not everyone was entirely sure that everything was done according to the rules (I8). Defraigne added: “they wondered a lot about my eligibility, and then said to themselves that it would be worse than better not to consider my candidacy as eligible” (I5). It was also confirmed by the Head of the Conciliation and Arbitration Council: “Everyone thought it was absurd to prevent Christine Defraigne from being a candidate. It would have done more harm than good” (I4). Others acknowledge the fact that it is a deviation from the statutes while some interviewees were simply unaware of the name of the body to which the statutes referred in the eligibility criteria (including Defraigne herself; I10). This deviation was deemed acceptable because of the norm of informality, the profile of the applicant, and to minimize the potential backlash: “it is a deviation from the rules, but a healthy one” (I8); “Defraigne is someone reputable, well-know, (…) but she had the right to present her candidacy and not authorizing her to do so due to party statutes when we know that statutes are… It would have been unacceptable” (I3); “we wanted to be inclusive, from what I recall, to avoid untimely manifestation of annoyance” (I9); “I found it a little superficial [the turmoil around this matter], because theoretically, it should be possible for everyone [to run]” (I7).

This was done without the assent of the other candidates and their views on the exception that was made are mixed: “I think that in the process itself, there was no wavering, but it revealed that the statutes need to be revised” (I1). They question the exceptionalism that leaves too much room for personal appreciation by the party bodies: “Of course, I told myself that it would be unacceptable that a woman like Christine Defraigne could have been excluded from the election. Some say that she was finally included, but what is wrong here is that she did it outside the rules. One shouldn't exclude the fact that, should she have been elected, appeals would have been launched, maybe even to the court, as many conflicts in associations end up in courts nowadays” (I2).

In an unprecedented publicization of the leadership race, the five candidates were invited for a televised debate on national television on 13 October. The next day, the Electoral Commission confirmed the five candidates.

Right after the official announcement of the candidacies, the campaign and decision phase started. The campaign prior to the first round started on 14 October and ended on 12 November, the date of the first round of the election. There was an informal campaign run by key figures who campaigned for the support of the candidate they endorsed: “it starts, and then, the phone starts to ring, a lot, a lot, a lot, it is really the reign of the phone. And those with whom the phone doesn't work, you have to go and see them, to go and eat with them” (I8). Key figures are aware that they cannot go wrong with their endorsement: “you have to be honest, you're playing part of your career, in that if the candidate that you support doesn't make it, automatically the risk is that you pay the price because one has to make choices for electoral lists, for media interviews, etc.” (I8). On 3 November, the newspaper Le Soir announced that six out of the 14 federal MPs and almost all the incumbent ministers explicitly support Bouchez. Regarding the formal campaign, the party organized a debate between all the candidates, which gave them a platform to address the membership, publicize their views, and project an image. However, what was new was that candidates themselves were much more proactive on social media, in the traditional media, and by organizing events in all the provincial branches.

The first round of the election was organized by mail-in ballots based on the membership list as of 25 September, following the specific party rules (Mouvement Réformateur (MR), 2019). The membership list was transmitted to the Electoral Commission before 15 October. The list was verified by a bailiff appointed by the Electoral Bureau. The list was transmitted to the mailing company that created a random identifier for each envelope. Each envelope included a letter describing the procedure, a one-page presentation of the program of the candidates, an anonymous ballot with the list of candidates appearing in the order set by a random draw, and an envelope with pre-paid postage. The mailing had to take place between 21 and 23 October. Ballots had to be received before 12 November at noon to be considered valid. The Electoral Bureau oversaw counting the ballots on the same day at 2 p.m. at the party headquarters. Candidates could designate observers. The number of ballots received was officially tallied and categorized between valid votes, suspect ballots, and blank/null votes. Valid votes were then categorized by the candidate. The minutes of the meeting, signed by the members of the bureau and the observers, include all these numbers. The final scores were announced by the president of the Conciliation and Arbitration Council:

- Georges-Louis Bouchez: 6,044 votes (44.6%).

- Denis Ducarme: 3,405 votes (25.1%).

- Christine Defraigne: 1,899 votes (14.0%).

- Philippe Goffin: 1,521 votes (11.2%).

- Clémentine Barzin: 685 votes (5.1%).

The second round had to take place within 30 days after the first round (Mouvement Réformateur (MR), 2019). The Electoral Bureau set the date to 29 November. In the informal campaign, the remaining contenders tried to convert the losing candidates. Goffin and Barzin, who lost in the first round, quickly endorsed Bouchez. Defraigne sent the two candidates 16 questions about their position on several issues, and their answers were the basis on which she officially endorsed Ducarme. The race also got some media coverage. The tension was high between the two candidates: “The opposition Ducarme-Bouchez was really, like, visual because on the one side you have the barracks and on the other, the young professional and thus, the ideal son-in-law and the locomotive. (…) It gave the impression of a physical opposition, really…” (I9; confirmed by I10). On 19 November, the two candidates published a photograph together on social media showing a pacification of tensions between them.

The second round was organized using the same procedure as the first round. The final scores were the following:

- Georges-Louis Bouchez: 62%.

- Denis Ducarme: 38%.

Our main interest is to understand when and how party actors introduce informality and influence leadership selection processes.

The gatekeeping phase reveals that according to the party rules, the main bodies in charge of the leadership selection process are the General Committee, the Conciliation and Arbitration Council, and the Electoral Bureau. The first one limits the pool of eligible candidates. The other two, respectively, oversee validating candidacies and the electoral process. The decision phase reveals a competitive race between five candidates, which unprecedently leads to a race in two rounds.

However, if limiting the analysis to the rules and outcome of the race, one entirely misses what happened. A careful analysis of the process during the preparation phase reveals (1) that the main actors of the race are not the ones ascribed in the statutes, (2) that the main candidacy requirement listed in the statutes was bent to fit the profile of the race, and (3) that the outcome, while seemingly competitive, was heavily controlled by a steering agent, the incumbent party leader.

As depicted in the previous section, the preparation phase initially leads to a planned coronation, a very common pattern in Belgian parties. Table 3 stresses the mechanisms at play during this initial phase. Michel as steering agent initially had the upper hand in the process by seizing the party leadership through persuasion. However, his appointment at the EU level changed the mood of the party. It became clear to all factions that he would not be able to lead the discussions to form a federal government. This led to an internal negotiation led by the party secretary within the Party Council. The outcome of this negotiation was the imperative to organize a leadership race. In a very common fashion, the two main factions of the party, led by their main figures, planned the distribution of party positions: The Michel faction would get the party leadership, and the Reynders faction would get the leadership in government.

However, this initial plan did not work. The planned candidate opted for another position although he was the only one deemed acceptable by both factions. This shows the limits of control and the power of individualities in a Liberal party. With the main key figures of both factions opting for government portfolios, there was no obvious candidate left for the presidency. This opened the second type of race and yielded a seemingly competitive contest. Yet Michel, with the help of the Electoral Bureau, remained the main steering agent throughout the process, especially before the official validation of candidacies and the start of the campaign (Table 4). The candidates themselves also contributed to influencing the process, especially Bouchez.

Anticipating the turn of events, Michel was influential in placing Bouchez in the right place at the right time: “If I hadn't been co-opted as senator, I wouldn't have met the eligibility criteria” (I2). Michel also strengthened his position as leader of the dominant faction by reaffirming his dominance of the Party Council and imposing the tempo of the process. He secured public endorsements of Bouchez from a lot of members of the Party Council and of the newly formed regional government. Interviewees recognize that informality peaked at this stage of the process when party actors took a clear position in favor of Bouchez. Yet, they consider it a normal part of the game. Interviewees stress that it was mostly prior to the official start of the campaign: “There were interferences, it is clear, (…) but as soon as the procedure was set, for instance, Charles was party leader, but he did not intervene at any moment' (I6); ‘the key stages are obviously when the candidates file their candidacies. Afterwards, you have the debates and then you realize that internally, things have already advanced very, very, very, very well in favor of one candidate” (I7). This is confirmed by Bouchez: “it is clear that in a political party (…) the electoral college can be of influence. Why? Because not everybody knows you, so if you have chairs of party branches who at a certain moment say, listen, you do what you want but my choice is this one (…) and it is true that I benefited from it, ministers who went in the newspapers or were asked and said (…) I endorse Georges-Louis Bouchez, it has an impact” (I2).

The losing candidates, however, are obviously more bitter about this: “Once the apparatus has decided, once the machine starts working, which is a crushing machine, once the barons come out every day to support Georges-Louis [the outcome of the election is decided]. And so, under the guise of an election where there were five candidates, it was a very locked, bound to happen” (I5).

Our interviews also reveal that Michel may even have incentivized the candidacies of Barzin and Goffin in order to split the women's votes and the votes of the socially liberal faction that would otherwise have concentrated on Defraigne: “And then (…) they went to find someone (…) who was in this social-liberal faction, which is Philippe Goffin, who was well rewarded for his candidacy, to weaken (this faction) a little bit (…) but hey, this is divide to conquer. And then, in extremis, they went to look for another woman, Clémentine Barzin and it was a way (…) to weaken my candidacy, it's fair game. (…) Of course they will tell you no but they were obviously prompted by the presidency at the time (…) it ensured that he [Georges-Louis Bouchez] would be in the second round. (…) I have no moral judgement, it is the reality of things, it's the reality of politics” (I5).

The informal support of the establishment for Bouchez's candidacy also dissuaded other candidates to run. Katrin Jadin wanted for instance to run but after testing the waters with influential people and close personal supporters in the party, she realized that they were all supporting Bouchez: “some candidates had a clear head start” (I7).

The Electoral Bureau (controlled by Michel) also played a role, especially regarding the validation of candidacies. Interestingly, several interviews stressed that particular emphasis had been placed on the rules and on respecting them from the moment a real competition was to take place, with the memory of the factional years in mind: “We came from a period where the party was very tense and I thought that it (a competitive race) was very enriching from the moment when the rules were well set. (…)” (I8); “but here, we had a real, a real election with serious candidates, who were, in competition, so it needed to be done flawlessly. (…) when you get 90%, we won't check whether it was only 88 or 92, we don't really care, I will say, and if there are 2–3 ballots that did not arrive…. But when you have such a competition, it is something else” (I3).

Yet, it did not prevent the party in the central office to make an exception to the rules to accept Defraigne's candidacy. The Electoral Bureau, probably in agreement with Michel, clearly weighted the risks of both options (turmoil if the candidacy was not allowed, turmoil if Defraigne had won) and made the choice to allow it, probably betting on the fact that she would not make it. This exception was not made for the other two rank-and-file applicants, designated as “cranky” (I9) or usual mavericks (I8; I10).

Among the candidates, Bouchez was probably the most influential agent. He persuaded Michel that he was the right candidate and he managed to get his support. This was crucial to then get the endorsement of the party establishment. Despite being the candidate of the establishment, Bouchez presents himself as an outsider who was badly treated by the party during the 2019 elections until they finally recognized his value: “everybody thought that I would be third on the list but internal arrangements lead to favoring others… but I accept, I shut up and run the campaign, and I end up with the second best personal score with more than 16,000 votes. (…) but due to the semi-open list system I don't get elected (…) which is not easy to swallow. (…) I often say that it is not what happens to you, but what you make out of it, and it illustrates that there is a window of opportunity for the party leadership” (I2).

Bouchez also portrays himself as a self-made man, with an atypical career and personality: “my personality and the way I wish the party would function is that I hate linear careers and convenience' (I2); ‘I had integrated the fact that they wouldn't give it to me (…). My personality makes that I have the capacity to be heard, to position myself, but the counterpart is that I make a lot of enemies (…). Thus, I think that the point is that I worked, I dared” (I2). Other interviewees confirm having uncertainties around his personality, but they rallied around his name because they did not want Ducarme to make it (I3; I7; I9; I10; I12). Bouchez also stresses the importance of loyalty: “the fact that I stayed in difficult times also played favorably in the relationship that I developed with Charles Michel” (I2). By combining loyalty to Michel to clear right-wing liberal positions, Bouchez distinguished himself from his key supporters: “one should be careful with these strategies [of repeated support from the party establishment] because people, especially in a liberal party, are not sheep” (I2). He also managed to rally the supporters of the Reynders faction who did not see candidacies from social liberals with a good eye: “Bouchez would not have been able to pass if he had known a real hostility from the Michel clan. And it's certain that he was on good terms with the Michel clan. Similarly, I don't think he was on bad terms with Didier Reynders either” (I4). According to interviews, there was a prior agreement on the name of Bouchez on both sides: “I think that Didier was among those who had to be part of the sustainable solution and the candidate that was proposed and who was elected met also that condition, it is clear” (I6). Thus, Bouchez used the steering agent and his faction, as he knew that seeking out endorsements was crucial for his candidacy, but he worked hard not to be identified as the candidate from one faction only, or from the establishment.

Interviewees confirm that quickly, the race opposed only two serious contenders. They show how Bouchez had a strategic and accurate perception of this balance of power in the party and used it, while other candidates did not steer the process and mainly used the race to make a name for themselves (I8; I9).

Defraigne was aware that she would not be able to steer the process but she wanted to run as a woman, to defend a certain view of the party, that of the social liberal wing formerly personified by the Michel faction: “It was a context where, under the federal government, there was a toughening of the party line, and I wasn't always in agreement with the directions taken. And so, there was some dissatisfaction and some fairly deep questioning from the social-liberal fringe of the party (…) So, (…) a whole series of friends have asked me to run (…). (…) a lot of activists too, a lot of people contacted me, from here and there, you know, we don't do surveys, it's a little bit of mood taking of people who did not find themselves in the prefabricated duo Bouchez-Ducarme, that's it. And then, that's it, I said to myself, I'm going to run” (I5).

It was also a candidacy against the establishment of the party behind Bouchez: “we immediately understood that it was George-Louis the man of the establishment” (I5).

Barzin had a much less accurate view of the status of the race. She overestimated the openness of the race and underestimated the role of the steering agent behind the scenes: “it was the first time that so many names were thrown out for potential candidacies; there was endorsements for X or Y candidate in the media by ministers, deputies, party branch presidents (…). But compared to leadership elections where you have one candidate presented by the party executive (…) you think that the game is over. Here, it was an entirely different process, with an opening with an unusual number of candidates, and a rare pluralism (…) and so we were not in something hidden” (I1).

She was aware, however, of her outsider status, but she wanted to personify a women's candidacy and a candidacy from Brussels. Some of the interviewees struggle to recall her name, which shows that her candidacy was never really considered a serious threat. Other interviewees link Goffin's successful campaign for leadership and the fact that he was appointed minister afterward: “Philippe Goffin, (…) was well rewarded for his candidacy” (I5; confirmed by I9 and I12).

Looking at when key actors use their informal influence to weigh the process, our analysis confirms the crucial role of the preparation phase. The incumbent leader steers the process and party actors manage the process before the validation of the candidacies. Yet, it nuances Aylott and Bolin's sequential approach. We underline the limitations of a static framework and show that the preparation phase can unfold in iterative ways (from coronation to contest). The mechanisms unfolded also highlight three sub-sequences in the preparation phase, found both in the coronation and in the contest: a moment of persuasion, a moment of negotiation, and a moment of planification.

We also highlight how key actors use their informal influence to weigh the process. For each sub-sequence of the process, we identify a mechanism—anticipation, dominance, persuasion, consultation, planification, and adaption—through which the main agent—the incumbent leader, with the help of the winning candidate, the party secretary and the Electoral Bureau in the competitive race—steered the process in an informal way, outside the party rules, to get the outcome they wanted, albeit with some fears around the uncertainty of the race. It is summarized in this statement: “yes, some figures intervened because when, between brackets, the party apparatus and the majority of the members of the group support a candidate, of course it matters (…) and it may have influenced the choice of the members” (I9). This focus on mechanisms goes beyond existing comparative frameworks that tend to describe actors and their roles (Aylott and Bolin, 2017) and offers causal analysis and theory-building insights.

This study applied process-tracing methods to understand the 2019 leadership selection process in the Belgian French-speaking liberal party MR. We triangulated a variety of sources to assemble an original and extremely rich qualitative material that we used to cross-check sequences, actors, and roles in the process. It allowed us to put focus on when and how key actors use their informal influence to weigh the process and influence the outcome of the race.

First, we identified the crucial phases of the race. Our description of the gatekeeping phase revealed that according to the party rules, three party bodies are in charge of the leadership selection process by either limiting the pool of eligible candidates or by overseeing and validating candidacies and the electoral process. Our report of the decision phase revealed a competitive race between five candidates, which unprecedently lead to a race in two rounds. However, our account of the preparation phase highlighted the added value of going beyond rules and outcomes. A careful analysis of the actual process revealed that the actual gatekeepers were not the ones ascribed in the statutes, that formal rules were bent to fit the profile of the race, and that the very nature of the race was much closer to a coronation than the results may suggest. It stresses how much can be learned by looking at the black box of the preparation phase. Yet, it nuances Aylott and Bolin's sequential approach. We underline the limitations of a static framework and show that the preparation phase can unfold in iterative ways. We also highlight three sub-sequences in the preparation phase, found both in the coronation and in the contest: a moment of persuasion, a moment of negotiation, and a moment of planification.

Second, we analyzed each sequence of the actual process during the preparation phase. We uncovered mechanisms through which party actors and party structures interacted to produce a certain outcome. Given the specific outlook of the 2019 race, we were able to highlight typical mechanisms at play in coronation and competition. In a coronation, we showed that the main steering agent was the incumbent leader and leader of the dominant party faction, Charles Michel. We showed how he used persuasion, negotiation, and planification to steer the process in an informal way, outside the party rules. Party structures and actual candidates do not play a major role. We showed that while competitions seemingly follow formal rules more strictly, there is still a lot of room for informality. The main steering agent remains the incumbent leader, but the candidates themselves play a much bigger role, as do the formal party structures. We showed that it is the capacity of the steering agent to anticipate, consult, support, and plan that makes the difference in terms of the outcome of the race. It is its ability to persuade or dissuade other party actors or candidates that allow him to remain in control. Similarly, he was able to force party structures to adapt formal rules to his advantage. In terms of timing, we emphasized that practically all the steering was done prior to the validation of the candidacies and that interferences almost disappeared during the campaign and decision phase.

This analysis offers theoretical insights that go beyond the specific case under study. While we do not contend that our empirical findings are applicable to other settings, we contend that the theoretical mechanisms that we have unfolded are not specific to the MR or this race and that they potentially apply to coronations and competitions in other political parties in other countries (Small, 2009). Following Beyer (2019), we argue that what may differ in other cases is the capacity of the steering agent to be successful in their interactions and for their steering to produce the expected effect. A steering agent may fail for multiple reasons: They may lack the capacity to get things done and implement their plan, they may face resistance from other agents or structures, or they may lack steering knowledge or instruments. Yet, if we want to fully understand how party leaders are selected, rules and outcomes fall short. Researchers have to start looking more qualitatively at actual races. This study has advocated for the added value of process tracing as a unique method to produce additional knowledge to understand when and how leadership races are played.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because under the ethics agreement with the interviewees, the interview content cannot be fully disclosed. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to dGhvbWFzLmxlZ2VpbkB1bGIuYmU=.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Philosophy and Social Sciences, Université libre de Bruxelles, and Ethics Committee of the FNRS. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

All authors listed have made equal substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This manuscript benefited from the funding FWO-FNRS EoS Excellence of Science O026018F (ID: 30431006) for the project RepResent.

We thank the editors of the Special Issue, Nicholas Aylott, and Niklas Bolin, for their fruitful comments on the previous version of this article. We are also indebted to the interviewees who granted us their valuable time and insights.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Allern, E. H., and Karlsen, R. (2014). “Unanimous, by acclamation? Party leadership selection in Norway,” in The Selection of Political Party Leaders in Contemporary Democracies (London: Routledge), 47–61.

Aylott, N., and Bolin, N. (2017). Managed intra-party democracy: Precursory delegation and party leader selection. Party Polit. 23, 55–65. doi: 10.1177/1354068816655569

Aylott, N., and Bolin, N. (2021). Conflicts and Coronations: Analysing Leader Selection in European Political Parties. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 1–28. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-55000-4_1

Barnea, S., and Rahat, G. (2007). Reforming candidate selection methods: a three-level approach. Party Polit. 13, 375–394. doi: 10.1177/1354068807075942

Beach, D., and Pedersen, R. B. (2013). Process-Tracing Methods: Foundations and Guidelines. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.2556282

Bennett, A., and Checkel, J. T. (2014). Process Tracing: From Metaphor to Analytic Tool. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139858472

Beyer, J. (2019). “Political steering approach,” in The Handbook of Political, Social, and Economic Transformation (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 132–140. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198829911.003.0013

Chiru, M., Gauja, A., Gherghina, S., and Rodríguez-Teruel, J. (2015). “Explaining change in party leadership selection rules,” in The Politics of Party Leadership: A Cross-National Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198748984.003.0003

Close C. Legein T. (Forthcoming). “Liberals,” in The Routledge Handbook of Political Parties, eds N. Carter, D. Keith, G. Sindre, S. Vasilopoulou (London: Routledge).

Collier, D. (2011). Understanding process tracing. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 44, 823–830. doi: 10.1017/S1049096511001429

Cross, W. (2018). Understanding power-sharing within political parties: stratarchy as mutual interdependence between the party in the centre and the party on the ground. Govern. Oppos. 53, 22. doi: 10.1017/gov.2016.22

Cross, W., and Blais, A. (2012). Who selects the party leader. Party Polit. 18, 127–150. doi: 10.1177/1354068810382935

Cross, W., Kenig, O., Pruysers, S., and Rahat, G. (2016). The Promise and Challenge of Party Primary Elections. A Comparative Perspective. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press.

Cross, W., and Pilet, J.-B. (2015). The Politics of Party Leadership: A Cross-National Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198748984.001.0001

Delwit, P. (2017). Du parti libéral au MR. 170 ans de libéralisme en Belgique. Bruxelles: Editions de l'Université de Bruxelles

Delwit, P. (2021). “Le Mouvement Réformateur (MR),” in Les partis politiques en Belgique, eds P. Delwit, and E. van Haute (Bruxelles: Les Editions de l'Université de Bruxelles), 275–299.

Ennser-Jedenastik, L., and Müller, W. C. (2014). “The selection of party leaders in Austria: channeling ambition effectively,” in The Selection of Political Party Leaders in Contemporary Parliamentary Democracies. A Comparative Study (London: Routledge).

Ennser-Jedenastik, L., and Schumacher, G. (2015). “Why some leaders die hard (and others don't): party goals, party institutions, and how they interact,” in The Politics of Party Leadership: A Cross-National Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198748984.003.0007

Gerring, J. (2004). What is a case study and what is it good for. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 98, 341–354. doi: 10.1017/S0003055404001182

Hedström, P. (2008). “Studying mechanisms to strenghten causal inferences in quantitative research”, in The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, eds J. M. Box-Steffensmeier, H. E. Brady, and D. Collier (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 319–335. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199286546.003.0013

Kenig, O. (2009a). Democratization of party leadership selection: do wider selectorates produce more competitive contests? Elect. Stud. 28, 240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2008.11.001

Kenig, O. (2009b). Classifying party leaders' selection methods in parliamentary democracies. J. Elect. Public Opin. Part. 19, 433–447. doi: 10.1080/17457280903275261

Kenig, O., Rahat, G., and Tuttnauer, O. (2015). Competitiveness of Party Leadership Selection Processes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 50–72. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198748984.003.0004

LeDuc, L. (2001). Democratizing party leadership selection. Party Polit. 7, 323–341. doi: 10.1177/1354068801007003004

Legein, T., and Van Haute, E. (2021). “Les partis politiques au prisme de l'organisation,” in Les partis politiques en Belgique, eds P. Delwit, and E. van Haute (Bruxelles: Editions de l'Université de Bruxelles), 43–66.

Luypaert J. Legein T. (Forthcoming). When do parties reform? Causes of programmatic-, organizational- personnel party reforms in the Belgian mainstream parties. Acta Politica.

Mahoney, J. (2012). The logic of process tracing tests in the social sciences. Sociol. Methods Res. 41, 570–597. doi: 10.1177/0049124112437709

Mouvement Réformateur (MR) (2019). Règlement Pour L'élection à la Présidence du Mouvement Réformateur au Suffrage Universel des Membres. Brussels: Mouvement Rèformateur.

Musella, F. (2017). Political Leaders Beyond Party Politics. New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-59348-7

O'Neill, B., and Stewart, D. K. (2009). Gender and political party leadership in Canada. Party Polit. 15, 737–757. doi: 10.1177/1354068809342526

Passarelli, G. (2015). The Presidentialization of Political Parties. Organizations, Institutions and Leaders. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9781137482464

Pedersen, H. H., and Schumacher, G. (2015). “Do leadership changes improve electoral performance?,” in The Politics of Party Leadership: A Cross-National Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198748984.003.0009

Pilet, J.-B., and Cross, W. (2014). The Selection of Political Party Leaders in Contemporary Parliamentary Democracies. A Comparative Study. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315856025

Pilet, J.-B., and Wauters, B. (2014). “The selection of party leaders in Belgium,” in The Selection of Political Party Leaders in Contemporary Parliamentary Democracies: A Comparative Study (London: Routledge), 30–46.

Rahat, G., Hazan, R. Y., and Katz, R. S. (2008). Democracy and political parties: on the uneasy relationships between participation, competition and representation. Party Polit. 14, 663–683. doi: 10.1177/1354068808093405

Ritchie, J., and Lewis, J. (2003). Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. Newcastle Upon Tyne: SAGE.

Sandri, G., Seddone, A., and Venturino, F. (2015a). Party Primaries in Comparative Perspective. Farnham: Ashgate. doi: 10.4324/9781315599595

Sandri, G., Seddone, A., and Venturino, F. (2015b). “Understanding leadership profile renewal,” in The Politics of Party Leadership: A Cross-National Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198748984.003.0006

Scarrow, S. E., Webb, P., and Poguntke, T. (2017). Organizing Political Parties; Representation, Participation, and Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198758631.001.0001

Small, M. L. (2009). ‘How many cases do I need?': on science and the logic of case selection in field-based research. Ethnography 10, 5–38. doi: 10.1177/1466138108099586

So, F. (2021). Don't air your dirty laundry: party leadership contests and parliamentary election outcomes. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 60, 3–24. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12383

Somer-Topcu, Z. (2017). Agree or disagree: how do party leader changes affect the distribution of voters' perceptions. Party Polit. 23, 66–75. doi: 10.1177/1354068816655568

Tansey, O. (2007). Process tracing and elite interviewing: a case for non-probability sampling. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 40, 765–772. doi: 10.1017/S1049096507071211

Vandeleene, A., Moens, P., Bouteca, N., and Wauters, B. (2020). “Great minds think alike? A study of party members' and leadership candidates' ideological congruence,” in Paper Presented at the ECPR General Conference. p. 24.

Vandeleene, A., and Van Haute, E. (2021). A comparative analysis of selection criteria of candidates in Belgium. Front. Polit. Sci. 3, 747. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.777747

Wauters, B. (2014). Democratising party leadership selection in Belgium: motivations and decision makers. Polit. Stud. 62, 61–80. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12002

Wauters, B., Bouteca, N., Kern, A., and Vandeleene, A. (2020). “What's in a party member'smind? Votingmotives in party leadership elections in Belgium,” in Paper Presented at the ECPR General Conference 2020, Proceedings. p. 22.

Keywords: leadership selection, Belgium, process-tracing, factionalism, party organizations, intra-party competition, party change

Citation: Legein T and van Haute E (2022) Fame and factions: A process-tracing analysis of the 2019 leadership selection process in the Belgian French-speaking liberal party (MR). Front. Polit. Sci. 4:1057051. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.1057051

Received: 29 September 2022; Accepted: 21 November 2022;

Published: 15 December 2022.

Edited by:

Niklas Bolin, Mid Sweden University, SwedenReviewed by:

Vincenzo Memoli, Università degli Studi di Catania, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Legein and van Haute. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Thomas Legein, dGhvbWFzLmxlZ2VpbkB1bGIuYmU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.