95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 03 January 2022

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.764939

This article is part of the Research Topic Beyond the Frontiers of Political Science: Is Good Governance Possible in Cataclysmic Times? View all 9 articles

Issues related to anthropogenic climate change such as global warming, fossil fuel emissions, and renewable energy have emerged as some of the most important and pertinent political questions today. While the role of the state in the Anthropocene has been explored in academia, there is a severe dearth of research on the relationship between climate change and nationalism, especially at the sub-state level. This paper builds on the concept of “green nationalism” among sub-state nationalist parties in European minority nations. Using a multimodal analysis of selected European Free Alliance (EFA) campaign posters from the past 30 years, the article explores an extensive “frame bridging” where minority nationalist political actors actively seek to link environmental issues to autonomy. Although there is an apparent continuity in minority nationalist support for green policies, earlier initiatives focused on preservation of local territory while EFA parties today frame climate change as a global challenge that requires local solutions, which only they can provide. The frame bridging between territorial belonging and progressive politics has lead to the emergence of an environmentally focused, minority nationalist agenda that advocates for autonomy in order to enact more ambitious green policies, or “green nationalism”. This shows that nationalism in the right ideological environment can be a foundation for climate action, as minority nationalist actors base their environmentally focused agenda to address the global climate crisis precisely on their nationalist ideology.

Anthropogenic climate change is rapidly becoming one of the most central issues in contemporary politics with ramifications at all levels of governance. Despite its importance, few scholars within the field of nationalism studies have worked on climate change and related topics. This is puzzling, as nationalism has been outlined as a direct consequence of industrialization (Gellner 1983) and capitalist modernity (Greenfield 2001), making its role in the “Anthropocene” both central and understudied as the “principal operative ideology of modernity” (Malešević 2019:33).

While a large scholarship is emerging on the role of the state in environmental politics (Jahn 2014; Duit et al., 2016; Sommerer and Lim 2016; van Tatenhove, 2016; Hildingsson et al., 2019), the first and equally important element of the word “nation-state” is severely neglected. Since nationalism and the ideal of the nation-state influences all elements and levels of contemporary politics, it also has profound effects on how communities deal with climate change. Similarly, while important work has begun on sub-state environmental policies (Galarraga et al., 2011; Bruyninckx et al., 2012; Brown 2017a; Halkos and Petrou 2018; López-Bao and Margalida 2018; Conversi and Ezeizabarrena 2019), there is an absence of work that deals directly with the nationalist aspect in minority nations or “ethnoregions”. This article attempts to remedy this by building upon an earlier argument that a “green nationalism” has emerged in European minority nations (Conversi and Hau 2021).

In this article, I focus on the relationship between autonomy and environmental issues at the sub-state level in an attempt to “liberate the geographical imagination from its state-based shackles” (Murphy 2010:769). Through a qualitative, multimodal analysis of selected campaign posters from the past 30 years across minority nationalist parties in the European Free Alliance (EFA), the largest grouping of autonomist, regionalist and pro-independence parties within the European Parliament, I argue that there is an unexplored continuity and change in how these perceive and champion environmental issues. Principally, sub-state nationalist actors have consistently maintained a discursive linkage between autonomy and environment since the 1970s. The nature of this relationship has however evolved from more parochial concern with preserving the local environment to a universalist understanding of climate change and the need for concrete green policies at the local level: a modern “green nationalism”.

As Mccrone, (1998) notes, there is no universal theory or firm definition of nationalism in academia (1998:3). Ernest Gellner has famously offered that nationalism stipulates that ethnic boundaries should not cut across political boundaries (Gellner 2008:1). The ideology of nationalism legitimates its own existence based on shared and specific characteristics such as ethnicity, language, or culture (Low 2000:357). It makes universalist claims because it supposes that the world is divided into bounded nation-states with certain rights and privileges (Conversi 1997; Boucher and Watson 2017:205). The rules of the current political playing field of “the world of nations” as Billig (1995:10) termed it, are that a nation should have a state, preferably all to itself (Gellner 1983:51). In Anthony Giddens’ memorable words, the nation-state is the “pre-eminent power-container of the modern era” (Giddens, 1987:120), the key components being a territorial boundedness and control over the means of violence.

Because of its bounded nature, the ideology of nationalism may have inherent difficulties in addressing global challenges such as the consequences of anthropogenic climate change. As Archibugi et al. (2011) note, addressing environmental issues at a purely local or national level does not represent sustainable change (2011:140). Some scholars have questioned whether nationalism, an ideology of the 19th century, is the correct answer to the biggest challenge of the 21st century (Braun 2021), or analyzed nationalism as a hindrance to climate action (Forcthner and Kølvraa, 2015).

However, others such as David Held have emphasized the durability of the (nation) state system, arguing that contemporary, supranational changes to the global system does not represent a direct challenge to the idea of the nation-state itself (1999:422). In a more radical vein, Anatol Lieven proposes that while climate change does represent a significant challenge to the nation-state, precisely that constellation is also the most powerful tool available to combat it, as nationalism provides the mass solidarity necessary to mobilize populations to climate action and collective effort (2020:xv). Further, since nationalism is a so-called “thin” ideology (Freeden 2003:32), it can be mobilized by a myriad of groups from the far right, far left, pro-business neo-conservative, anarcho-syndicalism—or, environmental and progressive political movements.

In this paper, I argue that the “green nationalism” of European minority nations represents coherent and persistent climate action that has developed from pre-existing attitudes of environmental protection of the territory (Conversi and Hau 2021). This new green nationalism is a 21st century ideology builds heavily on discursive frame bridging between increased autonomy or independence and climate issues and links early national Romanticist notions of territory and landscape with modern sustainability goals to create electorally successful political movements that combine support for autonomy and environmental policies. By grafting a progressive, universalist understanding of green policies unto traditionalist nationalist imagery, (minority) nationalism emerges as a foundation for climate action, rather than a hindrance to it.

Specifically in European minority nations, a fruitful scholarship has emerged on how nationalist actors graft an autonomy-focused agenda on to a plethora of “progressive politics” in their political project. This includes social programs and welfare (Culla 2013:373), social democracy (Lynch 2009; Serrano 2013), intercultural integration of immigrants (Hepburn 2011; Griera 2016; Conversi and Jeram 2017), and local democracy (Guibernau 2013). Further, there is a positive correlation with left-wing ideologies and support for independence in both Catalonia (Serrano 2013:538), and in Scotland where Scottish interests has become increasingly equated with left-wing politics (Mitchell et al., 2012:129). The article explores how minority nationalist actors seek to integrate green policies into their struggle for autonomy, arguing that a crucial point is how (minority) nationalism can lead to support for climate action.

I use green nationalism to signify an emerging understanding in European minority nations that the goal of minority nationalism - in the form of increased autonomy or outright independence - is a prerequisite for climate action. This rhetorically ties local concerns of autonomy and ecological preservation to global issues of climate change and the Anthropocene. There exists a certain continuity—visual and rhetorical—between contemporary minority green nationalism and earlier Romantic nationalist tropes of the land, which are common in nationalist imagery. The most significant change lies in the shift from a particularist to a universalist understanding of the environment, which is characteristic of this new green nationalism.

As David McCrone has written, nationalists tend to make great play of geography (1998:5); rivers, mountains, forests, and valleys all occupy central places in nationalist geo-political imaginaries. Since nationalism is intrinsically related to issues of belonging and territory, the relationship between the (local) environment and nationalism is not a recent phenomenon. Already Johann Herder, a seminal voice of early German nationalism, associated nations with territories marked by a particular climates and topographies (Patten 2010:15). Landscape features both natural and fabricated infrastructure are reproduced socially and culturally through text, art, media, schools—and political posters. This means that symbolic and mental landscapes are “deeply embedded in the image and self-understanding of nations and regions” (Sörlin 2010). Indeed, the articulation and evoking of territory is in itself a vital part of the historical emergence and growth of nationalism and regionalism. As such, the connection between Romantic ideas of the (rural) landscape and nationalism has been explored fruitfully in many contexts: From an “ideology of the rural” in cottage landscape imagery that embodies and shapes Irish national identity (Cusack 2001), to aesthetic-nationalist antagonism between French and English garden design as signifiers of national identity (Weltman-Aron 2001), or monolingual English road signs as an everyday landscape of national oppression in Wales (Jones and Merriman 2009).

The Romantic aspect of nationalism’s environmental relationship is perhaps largely rhetorical, outlining a pristine sense of nationhood deeply connected to the national territory and tied to the soil, full of nostalgia and primordialism. The green nationalism introduced in a previous article (Conversi and Hau 2021) refers to more robust state-led policies where sub-state governments take concrete legislative steps to protect specific portions of the (minority) national territory. Despite a substantial shift from the conservationist or preservationist schemes of the 1970s to the full-spectrum policies needed to combat climate change in the 2020s, I argue that the underpinning rhetoric rests on a certain continuity, fusing traditional nationalist tropes such as territory, soil and belonging with the progressive political stance of most contemporary autonomist and pro-independence movements. The most significant change lies not necessarily in the support for green policies, but in the framing and narratives surrounding the issue. Where earlier minority nationalist rhetoric on green issues focused the local environment as a means to preserve national identity, EFA parties today have adopted a more universalist discourse that frames climate change as a global issue with possible local changes, effectively “glocalizing” the issue in successful frame bridging between autonomy and environmentalism. This means that the emphasis has changed from our environment to our environment in sub-state nationalist rhetoric; or from particularism to universalism.

A clear example of this new, universalist approach to climate action where minority nationalist political actors outline local autonomy as the key to collective, global climate solutions is “energy sovereignty”. This is an emerging concept stating “the right of conscious individuals, communities and peoples to make their own decisions on energy generation, distribution and consumption in a way that is appropriate within their ecological, social, economic and cultural circumstances” (Various authors 2014), and is spearheaded by the Xse, Catalan Network for Energy Sovereignty (www.xse.cat). It seeks to bypass states in favour of popular sovereignty in energy production and consumption, and thus represents a fully evolved frame bridging between self-determination and sustainability and is a clear example of what I term green nationalism. In the EFA’s most recent policy manifesto from 2019, sustainability is one out of eleven main policy areas, and here the discursive link between green policies and autonomy is evident through the explicit invocation of “energy sovereignty”:

“It is essential that our regions and nations exercise more energy sovereignty, deciding on the forms of alternative energy to generate, at what price, and under which circumstances.” (EFA 2019:12, emphasis in original).

This fusion of sustainability and autonomy concerns builds on the post-sovereignty position1 adopted by many minority nationalist parties. As Michael Keating (2004) has noted, European integration has enabled minority nationalist movements to abandon traditional claims for sovereign statehood and adopt a “post sovereigntist” political position involving notions of shared sovereignty as well as an understanding of original authority as intrinsically divisible that transcends old models of statehood (2004:369). Other authors such as Manuel Castells (2011) has outlined Catalonia as the prototype of a post-Westphalian world order where sovereignty is not necessarily associated with the control of centralized state power (2011:50), and Lisanne Wilken (2001) has described how the Welsh Plaid Cymru’s nationalist ideology is emphatically not based on the ideal of the nation state or on state sovereignty, but on a desired pre-sovereign cultural tapestry akin to Medieval Europe (2001:63). This post-sovereignty position is a key foundation for the new universalist framing of climate action through autonomy, or green nationalism.

Similarly, I argue that minority nationalist actors make use of the rhetorical-ideological assemblage between autonomy and climate action to engage in green nation-building (see Smith 1986). This implies devolved or sub-state governments using regional climate policies and investments in local green infrastructure and renewable energy to construct a shared understanding of a separate nation in the given territory. Here, minority nationalist actors draw boundaries with their majority nation through their green nationalism, contrasting ostensibly ambitious regional environmental policies with a perceived lack of central state investment in sustainability and renewable energy. This competition leads to minority nationalist governments attempting to surpass central governments in terms of climate action. The progressive type of sub-state green nationalism particular to EFA parties then emerges as the prerequisite for climate action, rather than a hindrance as is the case of right-wing nationalists in Europe who focus on resource nationalism (Conversi 2020; Kulin et al., 2021).

In order to examine the claims, positions and policies of selected minority nationalist parties that combine issues of autonomy and nationalism with environmentalism, I use a multimodal analysis of selected EFA member parties’ campaign posters: The Scottish National Party (SNP), the Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC), For Corsica2, and the Galician National Bloc (BNG). The posters selected are not meant to be representative of these parties’ visual campaigns as a whole, which would require a much deeper analysis best suited for another paper and a larger sampling size. Rather, they form part of a qualitative analysis of how minority nationalist parties have used representations of the environment politically and traces a qualitative shift in the significance of these representations. The poster selection is also not completely balanced; being larger parties in government, more material was available from the SNP and ERC compared with smaller, newer constellations such as For Corsica, who incidentally also have fewer devolved powers and therefore less ability to effect green policies.

The posters were selected from sub-state parliamentary archives such as the Butlletí de la Generalitat de Catalunya, the Scottish Political Archive at the University of Stirling with more than 2000 flyers, posters, and campaign leaflets, and various EFA parties’ own archives. I looked specifically at visual representations of environmentalism and green policies over the past 40 years (in the case of Catalonia, fortuitously dating back to 1932). I substantiate the analysis by relying on policy documents and newspaper articles, including party manifestos drawn from the Manifesto Project Database, and relevant parliamentary bill proposals surrounding environmental, climate, and green policies, retrieved through the official websites of devolved parliaments and assemblies.

Posters have been important campaign tools for 200 years (Seidman 2008:1). While political posters have received scant attention in academic research (Rodríguez-Andrés and Canel 2017:1), posters contain valid statements on social reality and indicate important elements of social and political discourse (Geise and Vigsø 2017:43). Political posters document the messages of political actors and the images they are trying to convey to the public. As a genre of political communication, posters are however also dependent on the context that activates their potential for meaning, each poster reflecting certain political, social and cultural contexts that are involved in its production (Garcia 2007:34).

The posters selected for this paper include both protest posters (Geise 2017:15), produced as a socio-cultural critique and stemming from platforms involving both social movements and political parties, while others are election posters, instruments of strategic communication in a competition for votes (Ibid.). I examine the iconography and the semiotic–rhetorical components of the posters in a contextual analysis that unpacks the main themes through an attempt to “read” the images (Boucher and Watson 2017:6), where both text and image work together to produce certain statements or arguments that anchors the relevant meaning in a specific political climate (Kjeldsen 2002). I also lean on Peirce, (1940) typology of signs and Barthes’ (2009) distinction between denotation and connotation in visual expressions. Denotation refers to pure, “objective” descriptions, such as a car on a road, while connotation refers to the culturally shared values that frame our interpretation of that image, such as mobility, comfort, pollution, etc. (Geise and Vigsø 2017:47). Furthermore, borrowing a method from art history, I look at the posters’ visual iconography, which allows us to analyze their complex aesthetic messages (see Doerr 2017). Multimodality refers to a “semiotic interplay” where (written) language combines with other semiotic resources to express meaning (Kress and Leeuwen 2006:20). The political poster is an excellent example of multimodal text as it combines written text with a visual to express meaning (Martínez Lirola 2016:251).

Analytically, I use the concepts of “frame” and “frame bridging” in order to explore the complex relationship between autonomy issues and environmentalism in progressive minority nationalist parties. A frame identifies a social or political problem and a solution to be followed (Johnston and Noakes 2005: 5) and as such frames act as interpretative structures (Reber and Berger 2005: 186). In this article, the frames refer to the narrative structure that minority nationalist parties use in order to communicate their policy platform and state their claims. Developing on this concept, frame bridging refers to the linking of “ideologically congruent but structurally unconnected frames regarding a particular issue or problem” (Snow et al., 1986: 467). Frame bridging is useful for parties that seek to link two or more frames that were previously unconnected, such as nationalism and environmentalism, in order to form a new frame; in this case “green nationalism”. This bridging highlights a deliberate and strategic effort to link interests, ideas and policy issues in order to effect public policy shifts and bears some relation with climate change “bandwagoning” (Jinnah 2011), but often takes on a life of its own as new political dynamics can emerge from successful frame bridging.

The analysis is restricted to the “progressive”, center left minority nationalist parties of the European Free Alliance. While some right-wing nationalist movements may also have green agendas, that relationship is often adversarial and best analysed elsewhere on their own. Although some (right wing) minority nationalist parties such as Lega Nord are not members of the EFA, this party group is still the most significant expression of sub-state, regionalist, and minority nationalist political parties in the EU, and therefore represents a fruitful starting place for an analysis of the relationship between minority nationalism and environmentalism.

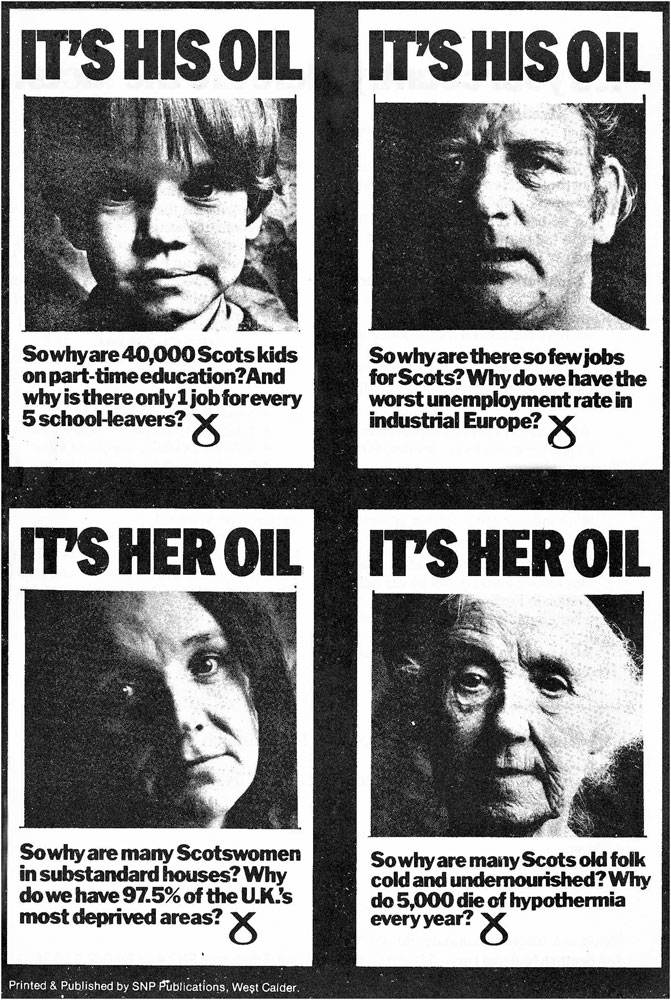

A prime example of continuity and change in sub-state framings of environmentalism, Scottish nationalism was initially heavily focused on the extraction of North Sea oil reserves (Esman 1977). The SNP’s first successful political campaign in the early 1970s, “It’s Scotland’s oil” was characterized by a resource nationalist narrative. The campaign’s aim was to draw focus on the possible economic benefits of the North Sea oil reserves for an independent Scotland (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. SNP campaign leaflet ‘It's his oil, it's her oil’. Accession Number: spa.gr.46.21, Scottish Political Archive, University of Stirling.

The campaign poster connects (national) resources, welfare, and increased autonomy for Scotland. Set in stark black and white, four faces that denote a representation of the whole of Scotland (male, female, infant, and elderly) look directly at the viewer, seemingly confronting them in an act of Althusserian interpellation (Althusser 1971). The heading above the faces reads, “It’s his/her oil”. Having hailed the viewer, the text below the faces asks direct questions to the viewer about the lack of jobs for Scots, sub-standard housing, education, and elderly care and hypothermia. The poster is designed to be serious and somber, leading the viewer to ask why, if the rich natural resources of Scotland belong to its people, they are impoverished and disenfranchised. It asserts a normative rather than declarative claim, as Scotland is not a sovereign state and currently does not have maritime borders distinct from the United Kingdom, nor any territorial claims outside this polity. The campaign was supremely successful and resonated well with voters in the two 1974 United Kingdom general elections, leading to the SNP winning 7 seats and 22% of the Scottish electorate the February election and 11 seats and 30% in the October re-election. Via the campaign, the SNP was able to counter the existing narrative that Scotland was economically dependent on the United Kingdom, giving credibility to the idea of independence as an economically viable—and desirable—option.

Later, during the Thatcher government in the 1980s, the SNP ran another North Sea oil campaign. This campaign had a similar theme but a subtle difference in message, which was more adversarial towards the Thatcher government (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. SNP campaign leaflet ‘Scotland's oil’. Accession Number: spa.761.1.1, Scottish Political Archive, University of Stirling.

This notorious poster depicts a smiling Margaret Thatcher with dripping fangs3 and the text: “No wonder she’s laughing. She’s got Scotland’s oil. Stop her—join the SNP”. This poster maintains the message that Scotland’s natural resources belong to the Scottish people, frame bridging between resource management and autonomy via a link between the national territory and national collective. However, this early 1980s poster is much more humorous than the 1974 one, Thatcher appearing highly satirized in a cartoony style. The poster’s message is also deeply adversarial towards the Westminster government, capitalizing on the great animosity towards Thatcher in Scotland. According to Ichijo, Thatcher and her cabinet ideology of market-oriented, aggressive individualism was, and is, seen by many as a threat to Scottish communitarian values (Ichijo 2003:37). This is corroborated by Mitchell et al.’s seminal 2007 survey of SNP members, in which members mention joining the party because of specific events in Scottish political history. Most cited was the discovery of oil in the North Sea, the basis for SNP’s popular 1970s campaign slogan, “It’s Scotland’s oil!”, and the runner-up was “Thatcherism” (Mitchell et al., 2012:74). This poster frame bridges three distinct issues: resource nationalism through the mobilization of the North Sea oil, anti-establishment antagonism towards the Thatcher government, and calls for increased Scottish autonomy. It also outlines the SNP as the vehicle to “protect” Scotland (and its natural resources) from Thatcher and Westminster, a narrative the party continues to this day with slogans such as, ‘Standing up for Scotland”.

This focus on oil and resource nationalism has however taken a backseat in SNP’s visual communication, as the party has evolved more towards a “green nationalism” that links autonomy and environmentalism. This includes a much-publicized stance against hydraulic fracturing, with humorous “Frack off!” badges, and a focus on wind energy and renewables. For example, one of the slogans for the 2014 Scottish independence referendum was, “Vote YES for a greener Scotland”. Flyers and posters highlighted the potential for green energy in an independent Scotland and asserting that the decarbonization of Scottish electricity production was being curtailed by Westminster.

More recently in 2019, the SNP government declared a “climate emergency”. The party set a target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045 and established a Climate Justice Fund in 2012 (Tokar 2014), investing heavily in offshore wind farms. These policy developments are instances of the frame bridging between environmental and autonomy issues going beyond the discursive regime; the green nationalism of the SNP has evolved into green nation building. As Royles and McEwen, 2015 (2015:1050) write, the SNP’s government has developed “the most successful and ambitious renewable energy programme in the United Kingdom, despit e energy being a reserved matter.” Similarly, a 19th century Romantic enchantment with the Highlands has been revived with highland “rewilding” (Brown et al., 2011) and planting 22 million new trees in order to return to the “natural” state of Scotland. This is part of a political evolution in Scottish nationalism. While Walter Scott’s popular works fused the wild landscapes of the highlands with turbulent histories and romantic traditions into powerful patriotic narratives, contemporary SNP discourse has moved from convervationism to ecologism, combining combines traditional nationalist concerns for the homeland’s rivers, forests and mountains with more contemporary, climate-focused environmental policies.

The assemblage between ecological and autonomy issues can even be extended to other topics, as is the case in one of the SNP’s posters during the United Kingdom EU referendum in 2016, known colloquially as “Brexit” (see Figures 3,4). This is a clear instance of minority nationalist frame bridging, where political actors seek to connect seemingly disparate issues discursively such as EU support, Scottish nationalism, and ecologism.

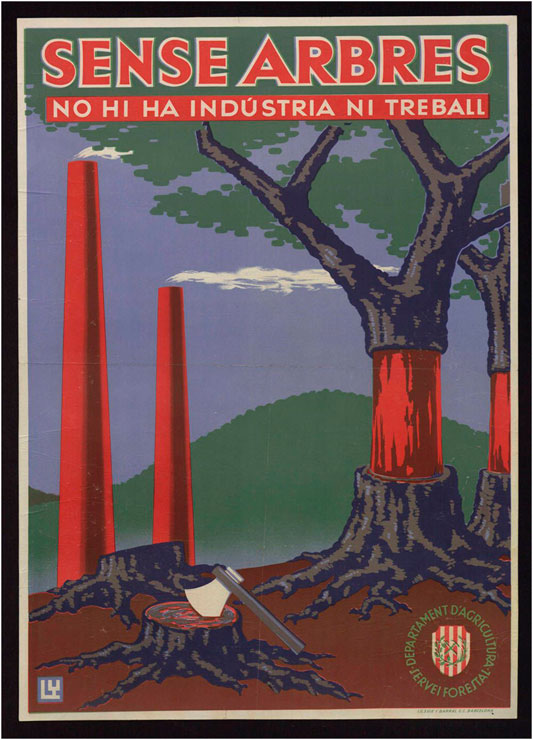

FIGURE 4. ‘Sense arbres no hi ha industria’, Servei Forestal de Catalunya. Pavelló de la República CRAI Library, Universitat de Barcelona.

In the poster shown in Figure 4, an image of the Scottish Highlands covered with wind turbines evokes a link between (national) territory and climate-friendly policies, in this case renewable energy. The text, “The EU is good for our environment” highlights not only environmental concerns, but support for European integration, and indeed uses climate policies in an attempt to bolster support for the EU. This could be seen as an instance of “frame bridging”, as the posters seeks to link “two or more ideologically congruent but structurally unconnected frames regarding a particular issue or problem” (Snow et al., 1986:467). This instrumental use of the EU is characteristic of SNP Euro-engagement (see Hau 2019), and here it is used in synergy with support for climate protection. However, the poster also manages to connect earlier Romantic ideas of the rural Highlands as filled with magic, Celtic mystique, and authenticity with contemporary issues in Scottish politics such as energy decarbonization. In this way, earlier concerns for the local environment gives way to a more modern, green policy position that elevates environmentalism from a local problem to a global issue.

In Catalonia, there has been a similar yet distinct evolution in the relationship between minority nationalism and environmentalism. Figure 4 shows a 1931 poster produced by the German-born Jewish designer Fritz Lewy, highlighting early Catalanist environmental concerns. The Catalan Forestry Service, el Servei Forestal, had been established in 1931 by ERC’s founder, Francesc Macià, and was pioneering in ecological conservation in Spain.

The poster, titled ‘Without trees, there is neither industry or work’, highlights the need for the preservation of Catalan forests to safeguard industrial production and jobs, which were key political themes in the 1930s. The environmental concern for Catalan forests appears rather instrumental, as the viewer is encouraged to see tree trunks as future factory chimneys, but the desired outcome is the preservation of Catalonia’s woodland. Workers, peasants and the middle classes felt that they were represented by Marcià, considered the “grandfather” of modern Catalan nationalism (DiGiacomo 1987:162). He was a master of public imagery, and this poster is no exception, linking contemporary important issues of work for all, industrial production and concern for the local environment, which all speak to the ERC’s self-understanding as a progressive, left of center political party. The purpose was “to conserve and improve Catalonia”s forest wealth, the creation of natural parks, and the conservation and service of hunting grounds and fishing lots” (Nogué and Wilbrand 2018: 445). In this narrative, natural resources such as forests, rivers and parks are a national concern, pertaining to all inhabitants of the (national) territory, rather than merely the concern of local landlords and homeowners. A similar process of “scenic nationalism” occurred in the United States with the establishment of National Parks (rather than natural parks) as a way to foster popular appreciation of the national magnificence (Mitchell 2017; Runte 1997).

The link between territory, environment, autonomy and welfare policies was a mainstay in Catalan politics during the 1930s, and the ERC made extensive use of Catalan rural imagery to promote their political project for regional welfare and Catalan autonomy (DiGiacomo 1987:163). This particular form of “green nation building” reached its height during the ERC’s tenure in government and was discontinued under the Francoist dictatorship following the Spanish Civil War (Paül i Carril 2004: 42), as the regime followed a policy of aggressive economic growth, el desarrollismo (Conversi 1997:219). It therefore is a particular feature of Catalan nationalism, but not its Spanish counterpart.

Fifty years later, after the Francoist hiatus, this assemblage returned. In the 1980 Spanish general elections, the ERC’s main poster also attempted to connect rural Catalan imagery and ideas of better times before the dictatorship with support for the ERC’s center-left policies and autonomy agenda (see Figure 5).

The poster represents rural idyll; wheat in the fields, flowers and fruit trees, a content farmer leaning on his pitchfork next to a charming, red-tiled cottage while birds fly above a full rainbow and a red sun rising over the hills. As DiGiacomo (1987:163) puts it, “The only concession to the passage of time is the SEAT 600 (the Spanish equivalent of the Volkswagen) parked near the fruit trees.” The text below reads, “To move forward: Vote Esquerra Republicana De Catalunya. The decisive vote, the useful vote.”

While the image is rural nostalgia distilled, the text instead implies progress and utility, framing ERC as a bridge between past and future. The romantic emphasis on rural nostalgia and a connection between the people and the land is common in nationalist discourse. However, in Catalonia and other minority nations, it seemingly merged into a distinct concern for environmental issues. Today’s principal pro-independence force, ERC, seek to continue this line, frame bridging between the fight for Catalan autonomy and climate change. In the large policy manifesto, “The republic we’ll create/La republica que farem”, launched in 2018, ERC outlined five key policy areas for the proposed future Catalan Republic. Number four was called “Territory and Sustainability”, explicitly highlighting the link between (national) territory and environmentalism that ERC seek to create:

“On a planet where natural resources are finite and climate change is a fact, the [Catalan] Republic will have the duty and responsibility to change towards a sustainable model of production and responsible consumption that guarantees the needs of future generations. (…) Given the situation of the energy sector in the Spanish system, it is necessary to take the commitment to renewable energy seriously, as it will not otherwise move forward. The Republic is the opportunity to do so.” (ERC 2018)

The brief goes on to list the environmental benefits of an independent Catalonia in terms of environmental protections, water conservation, renewable energy, an ambitious plan for zero emissions, and the establishment of new regulatory and advisory bodies in the Catalan administration in charge of sustainability and climate. Just as ERC did in 1931 and 1980, the party mobilizes in favour of independence through a focus on preserving and strengthening the national territory, or green nation building. There is then a blurring of national and natural concerns in ERC discourse that speaks to a profound—and electorally successful—frame bridging between these two issues. As the 2018 manifesto also shows, the Catalan nationalist discourse of ERC has changed from an earlier concern with preservation of local forests, rivers, and fields to become yet another weapon in the arsenal of reasons for independence. Climate change is framed as a global phenomenon that Catalonia can only tackle with independence, as ERC outlines a Catalan republic with greener ambitious than Spain.

Marcet and Argelaguet (2003) note that the ERC’s eco-friendly stance is cemented by the party’s internal statutes: Article 1 states that the party is “a democratic and non-dogmatic left-wing party whose references are the defence of the environment, human rights and the rights of national communities”.4 In the regional Catalan parliament, the ERC have attempted to put this discourse into practice. Efforts include a bill recently approved by the Catalan Parliament, Llei 16/2017, del canvi climátic.5 Although the Catalan “climate emergency bill” was similar to the aforementioned Scottish legislation, it went even further, banning fracking and planning a closure of all nuclear facilities by 2027 and a minimum reduction of CO2 emissions of 27 per cent by 2030. Playing right into the ERC’s framing of Spain preventing Catalonia from realizing its ambitious green policies however, the conservative PP (Partido Popular), then in power, took the legal reforms the Spanish Supreme Court (TS, Tribunal Supremo), the highest court in Spain. The Spanish Supreme Court ruled that such measures were unconstitutional as they exceeded the competencies normally held by Autonomous Communities according to the 1978 Spanish Constitution.

Environmental concerns have become increasingly linked to territorial politics in Spain, with the Catalan independence parties’ green agenda being contested by the Spanish state on territorial grounds as “unconstitutional” with little regard for the actual benefits of these policies. Such decisions have inadvertently legitimized ERC framing of climate change as a territorial-political issue, strengthening their frame bridging between autonomy and environmentalism. This has led the ERC to be at the forefront of climate action in Spain with traditionally strong views on ecological issues (Marshall 1996). Through such extensive frame bridging, minority nationalist parties such as the ERC link concern with the (national) environment to both supranational values, such as human rights, and a core traditional concern for territorial autonomy.

In other minority national posters, such as this early 1980s poster from Corsica, traditionally nationalist imagery of the logo-map (cf. Benedict Anderson 1991) is combined with ecological concerns (see Figure 6).

The poster, titled “Yes to water, no to ICO”, advocates in favor of hydroelectric energy instead of the ICO, Italie Corse nuclear cable. It was created as part of the nationalist Corsican mobilization resistance against the Vazziu-Ajaccio thermal and oil power plant. Corsican nationalism has historically been intricately linked with environmentalism. As de Winter and Tursan (2003) write, the Corsican nationalist anti-nuclear and anti-oil groups, who also held an international demonstration against pollution in the Mediterranean in 1973, coupled ecological concerns with demands for autonomy. They outlined Corsica as a geographic entity whose identity was threatened, and this gave the fight against nuclear power, toxic waste, and whale beachings in Corsica a distinctly national character. According to de la Calle and Fazi (2010), the Corsican nationalist movement introduced “postmaterialist” issues such as environmentalism to the political agenda and attracted many young voters to the cause. Indeed, since this link was established by sub-state actors in the 1970s, “environmentalist and Corsists claims have never been separated” (de Winter and Tursan 2003:176), with environmental politics on the island being tightly linked to nationalist movements (De la Calle and Fazi, 2015). This is evidenced by Corsican MEP and former EFA President François Alfonsi’s political start in this ecological-nationalist movement. He co-founded the “Comité Anti-Vaziu”, the main NGO opposing the installation of heavy oil thermal power plants in Corsica in the late 1970s.

Another Corsican protest poster is even more explicit in its blending of nationalist and environmentalist message and imagery (Figure 7).

This poster shows a dark figure with a white bandana, the flag and coat of arms of the island, being strangled in the water by a cable next to a hydroelectric dam. In Corsican and French, the poster reads: “A cable meant to strangle. Corsica wants to live. Yes to dams!” The poster mobilizes potent nationalism symbolism as the heraldic “Moor’s Head” of Corsica is literally strangled, symbolizing the death of the nation. This is aided by the text equating hydroelectric energy (dams) with life and nuclear power with death. It does however maintain a distinctly nationalist message; the nation of Corsica is in danger, rather than a global threat.

Today, however, the Corsican nationalist movement frames its green aspirations differently. In the 2019 manifesto of the Pè a Corsica (For Corsica) coalition, the largest sub-state nationalist political party on the island and EFA member6, one of the main policy goals reads:

“To respond to climate change through an ecological and social transition, creating wealth and well-being.” (For Corsica 2019)

The nationalist movement still frame environmental policies as linked to autonomy, as it is asserted Corsica cannot undertake a green energy shift without increased competencies, but the emphasis is on climate change as a global challenge with local solutions, quite distinct from the local conservation efforts of the 1970s.

Other minority nationalist posters make similar connections between ecology and demands for autonomy. One of the most striking—and arguably most successful—examples is the Galician campaign and NGO “Plataforma Nunca Máis” (“Never Again Platform”) characteristic 2002 poster (see Figure 8). The poster protests and commemorates the major environmental disaster known as the Prestige oil spill off the coast of Galicia in 2002. The Prestige oil spill polluted thousands of kilometers of coastline with 60.000 tons of heavy fuel oil, irreversibly harming local marine- and wildlife and crippling the Galician fishing industry.

Formed by a myriad of associations following, the Nunca Máis platform is closely related to the BNG. The poster’s designer, Xosé María Torné, has worked on several BNG campaign posters, and the platform website www.plataformanuncamais.org is registered and maintained by BNG personnel. The poster is austere, with stark white lettering on a black background spelling “Never Again”. The diagonal blue line evokes the national flag of Galicia, but the background color is inverted from white to black, symbolizing sorrow. In this way, the potent national symbol of the Galician flag is turned on its head, from symbolizing pride and community to gravity and despair. As with other campaign posters mentioned in this article, it evokes a linkage between environment, territory and the nation by its use of one of the most potent national symbols, the flag. The slogan has become well known across Spain and was re-used in the fight against forest fires in Galicia in 2006, as well as by the BNG in a campaign honouring the Galician victims of Francoism in 2018, showing its versatility as both an ecological message and a more territorially political one. In the BNG’s 2017 Statute of Principles, the “modern” EFA frame bridging between environmentalism and autonomy that outlines climate change as a global phenomenon with local solutions is evident:

“The BNG is a force actively committed to the defense of the environment and territory and champions policies in accordance with principles of sustainability in order to safeguard the planet” (BNG 2017:19)

Concretely, the BNG has proposed a Galician law against the climate crisis, including the protection of the landscape and ecosystems and addressing issues of mobility, waste, energy, mining and water management. The party has also called for the creation of a crisis cabinet to act on the climate emergency (emerxencia climática) (Europa press, 2019) and party leaders have railed against what they term “apostles of climate emergency denial” such as United States president Donald Trump or Brazilian leader Jair Bolsonaro (20 Minutos 2019).

Instead of simply promoting local conservationist concerns, EFA parties now campaign for sustainable energy production in their regions, and for climate-friendly policies in their regions, in majority states, and in the EU. The parties continuously seek to integrate a climate agenda with autonomy issues, and through such extensive frame bridging, EFA parties are able to combine a modern focus on renewables with earlier concerns for the local environment and the historically prominent anti-nuclear position of most EFA parties. This is evident by the mass demonstrations in the Basque Country against the nuclear power plant in Lemóniz 1977, where Basque nationalists leftists or abertzale spearheaded mobilization efforts and even led terrorist attacks against the installation (see Conversi 1997). In a similar, but more peaceful vein, the SNP still campaign against the Trident United Kingdom nuclear submarine depot based at Clyde on the west coast of Scotland, in addition to their more contemporary support for windmills as an attempt to form a political continuity. As other scholars have noted, such political parallelisms and frame bridging allow minority nationalist parties to symbolically and rhetorically link contemporary environmental action with earlier efforts (Brown 2017b). Despite this apparent continuity in minority nationalist support for green policies, however, there has been a significant change in how these parties frame environmental issues. Where earlier initiatives focused on preservation of local territory, EFA parties now outline climate change as a global challenge that requires local solutions, which they can only provide with increased autonomy.

The reasons for this minority nationalist assemblage between autonomy and environment are manifold, and the phenomenon has long roots (Keating 1996). It is largely connected to the social-democratic core of many sub-state nationalist parties and the alliances they have built with environmental groups, green parties, and other progressive social movements, such as that between the EFA and the European Greens (Keating and McCrone 2013). EFA parties appear to have taken up green, progressive policy positions in addition, rather than in opposition, to their original territorial demands. Holtz-Bacha and Johansson (2017) also count EFA “progressive regionalists” as part of the ideological “Green” family. Indeed, membership of EFA implies a more articulated world vision: beyond being simply undifferentiated “ethno-regionalist” parties, EFA members see themselves principally left-of-center social democratic parties, not just as members of a “minority nationalist fringe”. They are complex political parties with specific policy packages, combining their core demands for autonomy or territorial restricting with center-left, progressive policies.

This assemblage allowed minority nationalists parties such as the ERC, SNP, We make Corsica/For Corsica, and BNG to symbolically link contemporary environmental action with more traditional nationalist tropes of mountains, rivers and forests in the ancestral soil, focusing on preservation and environmental protection. Today, however, this frame bridging has acquired its own internal dynamic and is used as part of a “green nation building” where local responses to global climate change are championed as one of the prime reasons for increased autonomy or independence. Being able to show themselves as more environmentally ambitious than their majority nation counterparts enables sub-state nationalist governments to draw boundaries to central governments and distinguish themselves as more progressive (see Nash 2020). This policy assemblage is increasingly becoming part of these substate movements’ self-understanding and “negotiated nationalism” (Hau 2019), as autonomy movements argue in favor of self-determination in order to enact progressive politics. This means environmental action is increasingly used as a form of green nation-building in European minority nations, with important consequences for identity construction in these territories.

This article explores the concept of “green nationalism” that has emerged among sub-state nationalist movements in Europe (Conversi and Hau 2021). Although sub-state nationalist movements have a long-standing pedigree when it comes to protecting (local) territory, there has been a shift from preservationist initiatives of the 1970s to policies combating climate change as a global phenomenon in the 2010s. The underpinning rhetoric is similar in that it fuses a traditional nationalist focus on territory and belonging with the progressive political stance of most contemporary autonomist and pro-independence movements, although there has been a significant shift in the framing of climate change as a global, universal issue that requires local solutions.

This green nationalism appears to be electorally successful and politically viable. Both Scotland and Catalonia now have devolved parliaments with a majority in favor of independence and SNP and ERC in government, and since For Corsica won the first Corsican nationalist win in a French election in 2015, there has been a parliament majority in favor of increased autonomy on the island. Similarly, the BNG increased their representation in the Parliament of Galicia by 13 seats in the latest 2020 regional elections. The current electoral success of these parties depends on multiple factors, one of which is their ability to fuse a socially progressive, social democratic, green agenda with (minority) nationalism. This green nationalism has its own internal dynamics that leads to increasing connection between these two issues in minority nations, which may expand in the future as party competition over “green issues” increases. This is especially the case when parties engage in “green nation-building” where environmental action evolves into a crucial element of the sub-state nationalist movements” identity construction in competition with the majority state and central government Nacionalista Gallego, 2017; Catalunya, 2020; Derviş, 2020, Held, 2004; Scottish Parliament, 2018, Planeta, 2019; Scottish National Party, 2016; Scottish Renewables, 2017.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a past collaboration with the author.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

I am indebted to the editors and the three reviewers who gave very constructive feedback on the article, greatly enhancing the final product.

1See further discussion in Hau 2019.

2For Corsica was a coalition between Femu a Corsica, Corsica Libera, and other smaller parties.

3Interestingly, Thatcher was similarly demonized and depicted with fangs in Argentine newspapers following the Falklands War, and by the youth section of Labour, “Young Socialists” in campaigns.

4Estatuts de Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya, www.esquerra.cat/arxius/textosbasics/estatuts.pdf.

5Diario Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya no. 7426, 3 August 2017.

6Through Femu a Corsica/We make Corsica.

20 minutos, 2019 20 minutos (2019). El BNG pide el voto a los jóvenes preocupados por el cambio climático que “no quieren Trumps ni Bolsonaros. www.20minutos.es - Últimas Noticias, Available From: https://www.20minutos.es/noticia/4044850/0/el-bng-pide-el-voto-a-los-jovenes-preocupados-por-el-cambio-climatico-que-no-quieren-trumps-ni-bolsonaros/.

Althusser, L. (1971). “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. Editor B. Brewster (Trans.) (New York: Monthly Review Press). Available From: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1970/ideology.htm.

Archibugi, D., Koenig-Archibugi, M., and Marchetti, R. (2011). Global Democracy: Normative and Empirical Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boucher, G., and Watson, I. (2017). Introduction to a Visual Sociology of Smaller Nations in Europe. Vis. Stud. 32 (3), 205–211. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2017.1365462

Braun, M. (2021). Why Nationalism Is Not the Right Doctrine to Combat Climate Change - A Central European Perspective. New Perspect. 29 (2), 197–201. doi:10.1177/2336825X211009107

Brown, A. (2017a). EU Environmental Policies in Subnational Regions: The Case of Scotland and Bavaria. London: Routledge.

Brown, A. (2017b). The Dynamics of Frame-Bridging: Exploring the Nuclear Discourse in Scotland. Scottish Aff. 26 (2), 194–211. doi:10.3366/scot.2017.0178

Brown, C., McMorran, R., and Price, M. F. (2011). Rewilding - A New Paradigm for Nature Conservation in Scotland? Scottish Geographical J. 127 (4), 288–314. doi:10.1080/14702541.2012.666261

Catalunya, P. de. (2020). El Ple aprova la modificació de la Llei del canvi climàtic per gravar els vehicles més contaminants. Parlament de Catalunya. Available From: https://www.parlament.cat/web/actualitat/noticies/index.html?p_format=D&p_id=270371155.

Conversi, D., and Ezeizabarrena, X. (2019). “Autonomous Communities and Environmental Law: The Basque Case,” in Minority Self-Government in Europe and the Middle East. Editors O. Akbulut, and E. Aktoprak (Leiden, Boston: Brill–Nijhoff), 106–130.

Conversi, D., and Friis Hau, M. (2021). Green Nationalism. Climate Action and Environmentalism in Left Nationalist Parties. Environ. Polit. 30 (7), 1089–1110. doi:10.1080/09644016.2021.1907096

Conversi, D., and Jeram, S. (2017). Despite the Crisis: The Resilience of Intercultural Nationalism in Catalonia. Int. Migr 55 (2), 53–67. doi:10.1111/imig.12323

Conversi, D. (1997). The Basques, the Catalans, and Spain: Alternative Routes to Nationalist Mobilisation. London: Hurst and Company Publishers. Available From: https://www.academia.edu/1431872/The_Basques_the_Catalans_and_Spain_alternative_routes_to_nationalist_mobilisation.

Conversi, D. (2020). The Ultimate Challenge: Nationalism and Climate Change. Nationalities Pap. 48 (4), 625–636. doi:10.1017/nps.2020.18

Corsica, Pè. a. (2019). Un paese da fà! Accordu strategicu “Pè a Corsica. Available From: https://www.femuacorsica.corsica/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/accord-strategique-pe-a-corsica-1-converti.pdf.

Culla, J. B. (2013). Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya 1931-2012: Una història política. Barcelona: La Campana.

Cusack, T. (2001). A 'Countryside Bright with Cosy Homesteads': Irish Nationalism and the Cottage Landscape. Natl. Identities 3 (3), 221–238. doi:10.1080/14608940120086885

de la Calle, L., and Fazi, A. (2010). Making Nationalists Out of Frenchmen?: Substate Nationalism in Corsica. Nationalism Ethnic Polit. 16 (3–4), 397–419. doi:10.1080/13537113.2010.527228

Derviş, K. (2020). When Climate Activism and Nationalism Collide. Brookings. Available From: https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/when-climate-activism-and-nationalism-collide/(Accessed 10 15, 2021).

DiGiacomo, S. M. (1987). "La Caseta I l'Hortet": Rural Imagery in Catalan Urban Politics. Anthropological Q. 60 (4), 160–166. doi:10.2307/3317655

Doerr, N. (2017). How Right-wing versus Cosmopolitan Political Actors Mobilize and Translate Images of Immigrants in Transnational Contexts. Vis. Commun. 16 (3), 315–336. doi:10.1177/1470357217702850

Duit, A., Feindt, P. H., and Meadowcroft, J. (2016). Greening Leviathan: The Rise of the Environmental State. Environ. Polit. 25 (1), 1–23. doi:10.1080/09644016.2015.1085218

Esman, M. J. (1977). “Scottish Nationalism, North Sea Oil, and the British Response,” in Ethnic Conflict in the Western World. Editor M. J. Esman (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press), 251–286.

Europa Press (2019). El BNG propone que Galicia tenga un “comité de crisis” y una ley autonómica para hacer frente al cambio climático. Europa Press. Available From: https://www.europapress.es/epagro/noticia-bng-propone-galicia-tenga-comite-crisis-ley-autonomica-hacer-frente-cambio-climatico-20190912153154.html.

Forchtner, B., and Kølvraa, C. (2015). The Nature of Nationalism: Populist Radical Right Parties on Countryside and Climate. Nat. Cult. 10 (2), 199–224. doi:10.3167/nc.2015.100204

Galarraga, I., Gonzalez-Eguino, M., and Markandya, A. (2011). The Role of Regional Governments in Climate Change Policy. Env. Pol. Gov. 21 (3), 164–182. doi:10.1002/eet.572

Geise, S. (2017). “Theoretical Perspectives on Visual Political Communication through Election Posters,” in Election Posters Around the Globe: Political Campaigning in the Public Space. Editors C. Holtz-Bacha, and B. Johansson (Springer International Publishing), 13–31. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32498-2_2

Geise, S., and Vigsø, O. (2017). “Methodological Approaches to the Analysis of Visual Political Communication through Election Posters,” in Election Posters Around the Globe: Political Campaigning in the Public Space. Editors C. Holtz-Bacha, and B. Johansson (Springer International Publishing), 33–52. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32498-2_3

Giddens, A. (1987). A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism: The Nation-State and Violence. University of California Press.

Griera, M. (2016). The Governance of Religious Diversity in Stateless Nations: The Case of Catalonia. Religion, State. Soc. 44 (1), 13–31. doi:10.1080/09637494.2016.1171576

Guibernau, M. (2013). Secessionism in Catalonia: After Democracy. Ethnopolitics 12 (4), 368–393. doi:10.1080/17449057.2013.843245

Halkos, G., and Petrou, K. N. (2018). Assessing Waste Generation Efficiency in EU Regions towards Sustainable Environmental Policies. Sust. Dev. 26 (3), 281–301. doi:10.1002/sd.1701

Hau, M. F. (2019). Negotiating Nationalism: National Identity, Party Ideology, and Ideas of Europe in the Scottish National Party and Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (PhD Thesis). Aarhus: Aarhus University.

H. Bruyninckx, S. Happaerts, and K. Van den Brande (Editors) (2012). Sustainable Development and Subnational Governments: Policy-Making and Multi-Level Interactions (Palgrave Macmillan). Available From: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13597566.2014.920828.

Hepburn, E. (2011). ‘Citizens of the Region': Party Conceptions of Regional Citizenship and Immigrant Integration. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 50 (4), 504–529. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01940.x

Hildingsson, R., Kronsell, A., and Khan, J. (2019). The Green State and Industrial Decarbonisation. Environ. Polit. 28 (5), 909–928. doi:10.1080/09644016.2018.1488484

Holtz-Bacha, C., and Johansson, B. (2017). “Posters: From Announcements to Campaign Instruments,” in Election Posters Around the Globe: Political Campaigning in the Public Space. Editors C. Holtz-Bacha, and B. Johansson (Springer International Publishing), 1–12. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32498-2_1

Ichijo, A. (2003). The Uses of History: Anglo-British and Scottish Views of Europe. Reg. Fed. Stud. 13 (3), 23–43. doi:10.1080/13597560308559433

Jahn, D. (2014). “The Three Worlds of Environmental Politics. State and Environment”, in State and Environment. Editors A. Duit (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press). doi:10.7551/mitpress/9780262027120.003.0004

Jinnah, S. (2011). Climate Change Bandwagoning: The Impacts of Strategic Linkages on Regime Design, Maintenance, and Death. Glob. Environ. Polit. 11 (3), 1–9. Available From: https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GLEP_a_00065. doi:10.1162/glep_a_00065

Johnston, H., and Noakes, J. A. (2005). Frames of Protest: Social Movements and the Framing Perspective. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Jones, R., and Merriman, P. (2009). Hot, Banal and Everyday Nationalism: Bilingual Road Signs in Wales. Polit. Geogr. 28 (3), 164–173. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2009.03.002

Keating, M. (2004). European Integration and the Nationalities Question. Polit. Soc. 32 (3), 367–388. doi:10.1177/0032329204267295

Keating, M., and McCrone, D. (2013). “The Crisis of Social Democracy,” in The Crisis of Social Democracy in Europe. Editors M. Keating, and D. McCrone (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 1–13. doi:10.3366/edinburgh/9780748665822.003.0001

Keating, M. (1996). Nations against the State: The New Politics of Nationalism in Quebec, Catalonia and Scotland. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kress, G., and Leeuwen, T. van. (2006). Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. 2e éd. London: Routledge.

Kulin, J., Johansson Sevä, I., and Dunlap, R. E. (2021). Nationalist Ideology, Rightwing Populism, and Public Views about Climate Change in Europe. Environ. Polit. 0 (0), 1–24. doi:10.1080/09644016.2021.1898879

L. de Winter, and H. Tursan (Editors) (2003). Regionalist Parties in Western Europe (London: Routledge).

López-Bao, J. V., and Margalida, A. (2018). Slow Transposition of European Environmental Policies. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2 (6), 914. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0565-8

Lynch, P. (2009). From Social Democracy Back to No Ideology?-The Scottish National Party and Ideological Change in a Multi-Level Electoral Setting. Reg. Fed. Stud. 19 (4–5), 619–637. doi:10.1080/13597560903310402

Malešević, S. A. (2019). Grounded Nationalisms: A Sociological Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marcet, J., and Argelaguet, J. (2003). “Nationalist Parties in Catalonia. Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya and Esquerra Republicana,” in Regionalist Parties in Western Europe. Editors L. de Winter, and H. Tursan (London: Routledge).

Marshall, T. (1996). Catalan Nationalism, the Catalan Government and the Environment. Environ. Polit. 5 (3), 542–550. doi:10.1080/09644019608414288

Martínez Lirola, M. (2016). Multimodal Analysis of a Sample of Political Posters in Ireland during and after the Celtic Tiger. Rev. Signos 49 (91), 245–267. doi:10.4067/S0718-09342016000200005

Mitchell, J., Bennie, L., and Johns, R. (2012). The Scottish National Party: Transition to Power. Oxford: OUP.

Murphy, A. B. (2010). Identity and Territory. Geopolitics 15 (4), 769–772. doi:10.1080/14650041003717525

Nacionalista Gallego, B. (2017). En Bloque Cara a Un Tempo Novo. XVI Asemblea Nacional do BNG. Available From: https://nube.bng.gal/owncloud/index.php/s/H6lnOwma8tw6qMu.

Nash, S. L. (2020). ‘Anything Westminster Can Do We Can Do Better': the Scottish Climate Change Act and Placing a Sub-state Nation on the International Stage. Environ. Polit. 30 (0), 1024–1044. doi:10.1080/09644016.2020.1846957

Nogué, J., and Wilbrand, S. M. (2018). Landscape Identities in Catalonia. Landscape Res. 43 (3), 443–454. doi:10.1080/01426397.2017.1305344

Patten, A. (2010). “The Most Natural State”: Herder and Nationalism. Hist. Polit. Thought 31 (4), 657–689.

Paül i Carril, V. (2004). “The Search for Sustainability in Rural Periurban Landscapes: The Case of la Vall Baixa (Baix Llobregat, Catalonia, Spain),” in International Geographical Union. Managing the Environment for Rural Sustainability. Commission on the Sustainability of Rural Systems. Editors E. Makhanya, and C. Bryant (Montréal: International Geographical Union).

Planeta, M. (2019). El Constitucional tomba la Llei Catalana del Canvi Climàtic. Mon Planeta. Available From: http://elmon.cat/monplaneta/actualitat/constitucional-tomba-llei-catalana-del-canvi-climatic.

Reber, B. H., and Berger, B. K. (2005). Framing Analysis of Activist Rhetoric: How the Sierra Club Succeeds or Fails at Creating Salient Messages. Public Relations Rev. 31 (2), 185–195. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2005.02.020

Rodríguez-Andrés, R., and Canel, M. J. (2017). “Election Posters in Spain: An Old Genre Surviving New Media,” in Election Posters Around the Globe: Political Campaigning in the Public Space. Editors C. Holtz-Bacha, and B. Johansson (Springer International Publishing), 299–318. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32498-2_15

Royles, E., and McEwen, N. (2015). Empowered for Action? Capacities and Constraints in Sub-state Government Climate Action in Scotland and Wales. Environ. Polit. 24 (6), 1034–1054. doi:10.1080/09644016.2015.1053726

Runte, A. (1997). National Parks: The American Experience. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

Scottish National Party (2016). Europe Is Good for Scotland. Vote Remain. Edinburgh: Scottish National Party.

Scottish Parliament (20182018). Forestry and Land Management (Scotland) Act 2018. (testimony of Expert Participation)Available From: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2018/8/contents.

Scottish Renewables (2017). Renewable Energy Facts & Statistics. Available From: https://www.scottishrenewables.com/our-industry/statistics.

Seidman, S. A. (2008). Posters, Propaganda, and Persuasion in Election Campaigns Around the World and through History. Bern: Peter Lang.

Serrano, I. (2013). Just a Matter of Identity? Support for Independence in Catalonia. Reg. Fed. Stud. 23 (5), 523–545. doi:10.1080/13597566.2013.775945

Smith, A. D. (1986). State-making and Nation-Building. States Hist. 15, 228–263. doi:10.1108/eb055539

Snow, D. A., Rochford, E. B., Worden, S. K., and Benford, R. D. (1986). Frame Alignment Processes, Micromobilization, and Movement Participation. Am. Sociological Rev. 51 (4), 464. doi:10.2307/2095581

Sommerer, T., and Lim, S. (2016). The Environmental State as a Model for the World? an Analysis of Policy Repertoires in 37 Countries. Environ. Polit. 25 (1), 92–115. doi:10.1080/09644016.2015.1081719

Sörlin, S. (2010). The Articulation of Territory: Landscape and the Constitution of Regional and National Identity. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian J. Geogr. 53, 103–112. doi:10.1080/00291959950136821

Tokar, B. (2014). “Movements for Climate Justice in the US and Worldwide,” in Routledge Handbook of the Climate Change Movement. Editors M. Dietz, and H. Garrelts (London: Routledge).

Van Tatenhove, J. P. M. (2016). The Environmental State at Sea. Environ. Polit. 25 (1), 160–179. doi:10.1080/09644016.2015.1074386

Various authors (2014). Defining Energy Sovereignty. Madrid: El Ecologista, Ecologistas En Acción Magazine, 81. Available From: https://odg.cat/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/energy_sovereignty_0.pdf.

Weltman-Aron, B. (2001). On Other Grounds: Landscape Gardening and Nationalism in Eighteenth-Century England and France. Albany, New York: SUNY Press.

Keywords: campaign posters, climate change, frame analysis, nationalism, sub-state, visual analysis

Citation: Hau MF (2022) From Local Concerns to Global Challenges: Continuity and Change in Sub-state “Green Nationalism”. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:764939. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.764939

Received: 26 August 2021; Accepted: 10 November 2021;

Published: 03 January 2022.

Edited by:

Daniele Conversi, IKERBASQUE Basque Foundation for Science, SpainReviewed by:

Lorenzo Posocco, University College Dublin, IrelandCopyright © 2022 Hau. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mark F. Hau, bWZoQGZhb3MuZGs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.