95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 21 October 2021

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.743428

This article is part of the Research Topic Developing Democracy: Positive and Negative Effects of Youth Civic and Political Participation View all 4 articles

Coming to terms with the multidimensionsionality of civic and political engagement implies analyzing it in a comprehensive manner: not limited to conventional modes of expression, nor to dichotomic perspectives or observable acts of participation. Studies in this field tend to overlook cognitive and emotional dimensions as types of engagement which, alongside with behavior, constitute citizenship. In this article, we analyze data from the Portuguese sample of the CATCH-EyoU Project’s survey (1,007 young people aged between 14 and 30 years old). The main result is the identification of four distinct profiles according to behavioral, emotional and cognitive forms of engagement: Alienated, Passive, Disengaged and Engaged. These profiles are then examined to assess whether and how they differ in terms of: i) national and European identification, ii) relationships with alternative and traditional media, iii) democratic support, and iv) attitudes towards immigrants and refugees. The relationship between the different profiles and individual socio-demographic variables is also examined. We discuss how different dis/engagement profiles relate with socio-political dimensions and have different consequences both in terms of the political integration of young people and of the political challenges faced by democratic societies.

Youth civic and political participation occurs in different ways and contexts, is triggered by diverse factors and unfolds in a range of combinations and patterns. The diversity characterizing participation is widely reported, nationally and internationally (e.g., Sloam and Henn, 2019; Barrett and Zani 2015; Lamprianou, 2013; Fernandes-Jesus, Malafaia, Ferreira, Cicognani and Menezes, 2012; Ekman and Amnå, 2012; Norris, 2004). Also, approaching participation from a “broad view” (Ribeiro, Neves and Menezes, 2017), understanding it as a continuum of dynamic behaviors (e.g., Youniss, Bales, Christmas-Best, Diversi, McLaughlin and Silbereisen, 2002), sheds light on how democracy is performed in contemporary societies.

Diagnoses of the recession of democracy (Diamond, 2015) resonate with the widening gap between citizens and politics. At the time of the empirical study presented in this manuscript, the functioning of the government and, in particular, the confidence in political parties, was the lowest scored dimension in Portugal (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2019). According to the most recent 2020 report, Portugal is among the Western European countries with a “flawed democracy”—a category already occupied in 2018, albeit the upgrading to the “full democracy” status in 2019 –, with Western Europe’s average score declining since 2006 (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021). The growth of populist and radical movements in Europe and the increase of the “global intolerance for the adequate procedure, deliberative rationality and political patience that democratic systems always demand” (Appadurai, 2017, p. 25) have raised important challenges, namely regarding groups, such as young people, that are reportedly more dissatisfied with the mechanisms of representative democracy.

Political officials express such concerns, highlighting the need to “prevent and combat violent radicalisation among young people” and to foster knowledgeable, critical, and participatory citizens (Council of Europe, 2017, p. 51). Indeed, young people are among the social groups identified as being on the losing side of the unbridled neoliberal development (Della Porta, 2017), being particularly affected by financial hardships, both in terms of unemployment and labour precariousness (OECD, 2015). Simultaneously, young people are frequently called to the stand when it comes to finding explanations for the decline in conventional politics, despite the recognition of a profound shift in how politicisation occurs in the current generation, with an expansion of the very meaning of politics in terms of targets, spheres, and repertoires of action (Henn, Weinstein and Wring, 2002; Norris, 2004). A more detailed understanding of political engagement and the exploration of the democratic implications of its different nuances remain an important research endeavour.

It has been widely documented that a considerable proportion of young people do not participate (e.g., Putnam, 2000; Henn, Weinstein and Forrest, 2005): do not vote, do not do volunteer, do not use the internet for political or social reasons, are not ethically aware consumers, and so on. In a nutshell, a large number of youngsters can easily be assessed as apathetic (e.g., Cammaerts, Bruter, Banaji, Harrison and Anstead, 2015). However, recent developments in the field of youth civic and political participation prevent us from making such a hasty assessment. On the one hand, the absence of observable acts of participation does not always equate with apathy and may not be a synonym of complete inaction (e.g., Schudson, 1996; Amnå and Ekman, 2015). On the other hand, the focus on spectacular forms of participation neglects “ordinary” approaches to engagement and prevents a nuanced understanding of the relationship between youth and politics (e.g., Malafaia, Neves and Menezes, 2021).

Taking this evidence into due account, it is necessary to overcome the dichotomist perspective of youth engagement, and in look for the multidimensionsionality of non-participation, including political passivity that has been strangely ignored in the literature (Amnå and Ekman, 2015; Weiss, 2020). Indeed, the studies in this field tend to privilege the domain of action–the number of typologies created to account for the range of forms of participation is quite illustrative (e.g., Pattie, Seyd and Whiteley, 2003; Teorell, Torcal and Montero, 2007; Van Deth, 2014). To be sure, cognitive and emotional dimensions are often present in the studies of participation, but mainly as predictive factors and correlates (Van Zomeren et al., 2008; Eckstein, Noack and Gniewosz, 2013), and mostly overlooked as types of engagement that, along with behavior, constitute citizenship. Considering the behavioural, cognitive, and emotional dimensions enables going beyond an artificial, static condition of citizenship and can tell us much about the present and the future of democracies. Thus, based on the Portuguese data of the European CATCH-EyoU Project, this article examines different profiles of civic and political engagement, exploring how they uncover the diverse ways in which young people are constructing themselves as democratic European citizens. Concretely, we seek to explore whether and how different profiles of engagement reveal distinct patterns of: i) national and European identification, ii) relationship with alternative and traditional media, iii) democratic support, and iv) attitudes towards immigrants and refugees. The relationship between the different profiles and the individual socio-demographic variables is also examined.

The study of youth civic and political engagement is currently punctuated by two intertwined discourses: i) the current political upheavals call for an active participation of citizens in public affairs for the sake of a well-functioning participatory and representative democracy; and ii) young people are estranged from institutional politics whilst presenting progressively complex patterns of engagement that can no longer be grasped by black-and-white kinds of analysis.

In Europe and elsewhere, the polarised political climate, the economic crisis (worsened by the COVID pandemic), the distrust in political class, and the rise of populist and anti-democratic movements have brought about relevant challenges to democratic systems (Sloam, 2014; Norris and Inglehart, 2018). The Democracy Index (2019) alerts that “in 2018 the score for the perceptions of democracy suffered its biggest fall in the index since 2010” (p. 5). Unsurprisingly, political participation is one of the most studied topics concerning the development of contemporary democracies, particularly in Western countries (Ekman and Amnå, 2012; Menezes et al., 2012; Van Deth, 2014; Barrett and Zani, 2015). However, to interpret this phenomenon properly, one must consider other aspects that significantly impact on contemporary liberal democracies. We should, for example, pay more attention to the concentration of political and participatory opportunities in those with more cultural and economic resources (Lamprianou, 2013), the instrumentalisation of young people as voters and passive supporters (Amnå and Ekman, 2015), and the increase of the cultural divide since the outset of the global financial crisis (Norris and Inglehart, 2018).

The consistently high levels of scepticism among young European citizens regarding national and European political institutions, recurrently signal out young people under a number of labels: e.g., “problematic,” “lost,” “apathetic,” “at risk,” “immature” (Pontes, Henn and Griffiths, 2018; Allen and Ainley, 2011; Norris, 2004). The reproduction of such labelling, however, produces worrying and long-term consequences that often mask other problems, such as the lack of responsiveness and political transparency in contemporary liberal democratic states (Amnå and Ekman, 2015; Henn et al., 2005). In parallel (and consequently) young people lose their trust in formal political processes and often also in themselves as politically competent citizens (Malafaia, Neves and Menezes, 2021; Norris, 2004). An analysis of a large cross-disciplinary corpus of published work aiming to understand how the concept of “active citizenship” is mobilised shows that, in political terms, youth is always described as “getting ready” but rarely as active citizens (Banaji, Mejias, Kouts, Piedade, Pavlopoulos, Tzankova, Mackova and Amnå, 2018).

Research in this field has shown that looking for dichotomies is rather simplistic when it comes to youth political engagement and, in fact, neglects many forms of engagement that compose the democratic landscape (Amnå and Ekman, 2015). In the last decade, the criticisms of the narrow conceptions of politics when researching youngsters’ participation (Ribeiro et al., 2017; Barrett and Zani, 2015; Menezes et al., 2012; O’Toole et al., 2015; Flanagan, 2013), opened up new avenues for learning about youth engagement. This shift made recognising young people as fully-fledged political actors and citizens possible, moving beyond seeing them as “political appendices” (Marsh et al., 2007; Henn et al., 2005; O Tool et al., 2015). The broader scope of political engagement revealed that while “big P” politics (electoral) may be seen as a source of disappointment, “little p” politics (lifestyle, community-based) is acquiring a new importance (Kahne et al., 2013), and that sometimes non-participation does not mean that politics is disregarded (Ekman and Amnå, 2014). However, a recent literature review reveals that “the current literature is inconsistent in the inclusion of new modes of participation that are increasingly common among young adults (…); result[ing] the fact that non-participation has not yet been problematized adequately” (Weiss, 2020, p. 9). The understanding of Millennials as somewhat distinct, as a “generation apart” (Henn, Weinstein and Wring, 2002), as politically interested although highly reluctant regarding formal politics, led to ongoing attempts to make sense of their multifaceted patterns and profiles of engagement (Fox, 2015). Yet, exactly how these political profiles relate to socio-political dimensions and, ultimately, shape democratic citizenship, needs to be further explored.

Large-scale social networks, horizontal forms of organisation, online forms of expression, non-conventional and direct modes of engagement, often grounded on cause-oriented projects (de Moor, 2016; Sloam, 2014; Norris, 2004), define youth participation and outline the current Youthquake (italic in the original, Sloam and Henn, 2019). This update of young people as political actors opens up unpredictable–because they are non-linear–spaces, requiring the recognition that repertoires of action are expanding (e.g., Pontes, Henn and Griffiths, 2018; Sloam, 2014). The notion of repertoire, originated from the social movement literature (Taylor and Van Dyke, 2004), is helpful to make sense of the constellations of strategies and actions employed in political action, as it translates diverse patterns and profiles of engagement. Oser (2017) analyses “actor-centred repertoires of political action,” clustered among American young people, showing that the repertoire approach is more suitable and coherent for analysing citizen participation than the focus on doing/not doing specific activities. Whilst Millennials in Western societies are often defined as a post-materialistic generation (Norris, 2004; Sloam, 2014), they are able to display striking mobilisation, creating, importing and transforming repertoires of action grounded on materialistic concerns–the anti-austerity movements in southern Europe were a fine example of this. In sum, examining the political engagement of contemporary youth entails, first and foremost, overcoming the rhetoric of the political anomy of young people, and complexifying the narratives about the participatory crisis (which must be framed as part and parcel of a changing world).

In this article, the amplitude of engagement is not only approached in terms of its different dimensions (emotional, cognitive, and behavioral), but also according to the variety of forms and contexts through which participation unfolds. We follow Weiss (2020) pleas regarding the need to account for new modes of participation, including those that are increasingly more attractive for young people (e.g., online or expressive). In this regard, it is crucial a research perspective anchored on a practice-based approach to democratic citizenship, as something experienced in real-life contexts, with opportunities for citizens to make sense of their role and place in the world (Biesta and Lawy, 2006). To put it bluntly, researching young people’s participation implies the recognition that they “learn at least as much about democracy and citizenship from their participation in the range of different practices that make up their lives, as they learn from that which is officially prescribed and formally taught” (Biesta and Lawy, 2006, p. 73). As it will be fleshed out later, the behavioral dimension of engagement explored in this article encompasses different practices of participation in real-life contexts–from collective demonstrations to political encounters and volunteer organizations.

The recognition of the multi-dimensionality of participation is no breaking news (e.g., Verba and Nie, 1972), but the amplitude of the current modes of engagement in relation to democracies brings new challenges. Research trying to unpack the many tones of the engagement, including examining the apparent non-participation, reveals that youngsters are often unable to identify their political engagement as such. Even when they fall into categories of “political passivity,” they hold opinions about political matters, acknowledging their relevance, even when they are not interested in them (Sloam, 2007; Mathé, 2018). This is why we must consider “pre-political” behaviours (Amnå and Ekman, 2015) and the temporal nature of issue-based engagement (Ekman and Amnå, 2014) to understand new forms of participation and, afterwards, to draw out their social and democratic implications.

Research has been showing the importance of considering several dimensions (social, psychological, demographical, motivational, emotional, and cognitive) to explain different forms of participation. Furthermore, it is argued that, in order to understand and predict participation, the psychological dimension of engagement needs to be taken into account, as it is often a prelude for participation (Barrett and Zani, 2015). This entails a perspective of political engagement that considers individuals’ behavior, coupled with the cognitive and emotional domains of participation. In line with Ekman and Amnå (2012) notion of latent forms of participation, cognitive engagement encompasses political interest and the search for political information, therefore representing individuals’ efforts to understand political issues and keep up with the current political debates (Pontes et al., 2018). This dimension is also present in the official political documents that define guidelines and goals for citizenship education. In the 2017 Eurydice report on citizenship education at school in Europe, the dimension of “acting democratically” emphasizes the cognitive aspects of citizenship–e.g., the knowledge of political processes and institutions–and is considered the most political part of citizenship education, since it is expected that democratic knowledge is intertwined with active participation in political life (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2017). Indeed (cognitive) awareness about politics is indicated as the divider between apathy and alienation, notwithstanding the puzzles brought about by apathy in efficient representative democracies (Dahl et al., 2018). The psychological process of engagement encompasses not only the cognitive dimension, but also the emotional aspect of engagement (Barrett, 2015). The emotional dimension reflects, for instance, perceptions about the value of participation in politics and reactions to politicians’ actions and the levels of responsiveness attributed to political processes. The important role of emotions as “an integral part of political action, both individually and collectively” (Cepernich, 2015, p. 1) has already been stressed by political philosophers (e.g., Bobbio, 1995), and it is explored in studies from psychology and political science to explain civic and political participation (Van Zomeren, et al., 2008). However, “emotions struggled to establish themselves as a category of social sciences” (Cepernich, 2015, p. 1), and political engagement continues to focus mostly on variables assessing political actions and, thus, studies in this domain often fail to recognize that a person who is “behaviorally passive” may not necessarily be politically unengaged or disaffected. In fact, other studies show that “non-activists” (Sloam, 2007) and “passive” groups (Ekman and Amnå, 2014; Mathé, 2018) actually pay attention, formulate opinions and display feelings concerning political matters, even if they do not participate overtly.

Profiles of participation are not individually crystalized, and nobody is either active or passive in every circumstance. Rather, and in line with the “standby” notion (Ekman and Amnå, 2014), participation can be activated at any moment, framed by specific contexts and triggered by specific factors, such as particular moments of economic hardship (Malafaia et al., 2017) and perceptions of discrimination (Vrablikova and Linek, 2015; Ribeiro et al., 2016). Also, researching disengaged groups–or, better said, those who display, at a given time, a disengaged profile–requires a closer look, considering that they often hold low levels of cultural capital, coming from poor backgrounds, standing on the weak side of the digital divide, profoundly politically disenchanted and tending to react very negatively to cultural diversity (Sloam and Henn, 2019). Researching the youngsters’ attitudes towards the European Union and how they identify as European citizens came from the need to understand the legitimization terms of the European political project for the native young Europeans (Mazzoni et al., 2018; Hansen, 1998). As noted in the Democracy Index (2019) report, political participation in many countries is being framed by anti-establishment motivations, grounded in the rise of identity politics and the attraction towards leaders whose success lies on a “democracy fatigue” that is insidiously reoriented against the liberal, deliberative and inclusive dimensions of the national versions of democracy (Appadurai, 2017). Contrariwise, the “young cosmopolitans” (Sloam and Henn, 2019) correspond to those youngsters who present broad participatory repertoires (including both conventional and non-conventional politics) being associated to a greater political sophistication that translates not only into political interest and knowledge, but also into the ability to navigate through different political arenas. Looking at these different profiles makes getting a sense of how politics and citizenship are being lived possible, while also understand how they are being transformed. What kind of engagement profiles do Portuguese young people display? In what ways do these profiles reveal different forms of identification with Europe? What new forms of relationship with the media, as vehicles of political information, emerge? Do different profiles of engagement involve different attitudes towards democracy and cultural diversity? The answers to these questions contribute to a better understanding of Portuguese young people’s engagement and democratic citizenship.

For this study, we used the survey data collected by the Portuguese team of the European CATCH-EyoU project (Constructing Active Citizenship with European Youth: Policies, Practices, Challenges and Solutions), funded by Horizon 2020. A total of 1,007 Portuguese young people (63.3% female) participated in the survey, and the data was collected using both online and paper formats. All participants provided informed consent to participate in this research, either signed by them or by their parents/legal guardians in the case of the under-age participants. The youngsters were recruited in diverse contexts of education and participation (e.g., regular and vocational schools, public and private higher education institutions, youth associations), located mainly in the Metropolitan area of Porto, but also in the Lisbon and Braga districts. Overall, data was collected between Autumn 2016 and Spring 2017, and the sample is composed by a group enrolled in school education (higher and lower tracks) aged between 14 and 20 years old (n = 416, 59.5% female; Mage = 16.5, SD = 1.13) and a group aged between 17 and 30 years old (n = 591, 65.9% female; Mage = 22.1, SD = 5.29). The instrument is a self-report questionnaire that comprises a wide set of scales observing civic and political participation, political attitudes and relationship with Europe.

This paper examines profiles of youth engagement to understand how they differ in terms of personal and sociodemographic characteristics, and their relationship with variables associated to European democratic citizenship. Thus, we proceeded as following:

First, and in order to look for profiles of youth engagement, we began by performing a cluster analysis including behavioural, cognitive and emotional dimensions of civic and political engagement. Therefore, we explored how the Portuguese youngsters from our sample could be classified according to their behavioural engagement (activist, online and civic forms of participation), their emotional engagement (trust and alienation) and their cognitive engagement (information and interest). To identify profiles of civic and political engagement, we applied K-means clustering. Contrary to hierarchical clustering, partitional clustering (e.g., K-means) is often chosen in pattern recognition, since it does not impose a hierarchical structure to the data: all clusters are taken simultaneously as a partition of it, potentiating more homogeneous and similar clusters (Jain, 2010). Additionally, K-means algorithm has recurrently proven to have good cluster recovery properties (e.g., Steinley, 2006; Dimitriadou, Dolnicˇar and Weingessel, 2002), entailing the opportunity of modification of the values provided by the user (Steinley, 2006), making it an appropriate analytical approach.

Secondly, we performed analyses of variance (ANOVA), controlling for multiple testing through Sidak correction, in order to examine whether and how different profiles of engagement are related to i) personal and sociodemographic characteristics (age, perception of household’s money, religiosity, educational plans and life satisfaction), to ii) sociopolitical variables (democracy support, attitudes towards immigrants and refugees) and media relationship (trust in traditional and alternative media) and to iii) the European and national identification. The IBM SPSS Statistics 22 software was used for data analysis.

The behavioural component of civic and political engagement was assessed with an adaptation of the Political Action Scale (Lyons, 2008), which has been used in national studies with similar samples (Menezes et al., 2012). The question read as follows: “People can express their opinions regarding important local, environmental or political issues. They do so by participating in different activities. Have you done any of the following in the past 12 months?”—response scale was 1 “No,” 2 “Rarely,” 3 “Sometimes,” 4 “Often,” or 5 “very often.” After exploratory factor analysis (EFA) (civic and political) behavioural engagement is a three-dimensional construct (Maximum Likelihood extraction (ML), three factor solution, 44.9% explained variance): Activist engagement with nine items (Cronbach’s α = 0.88): e.g., “Painted or stuck political messages or graffiti on walls,” “Taken part in a demonstration or strike”; Online engagement with six items (Cronbach’s α = 0.76): e.g., “Shared news or music or videos with social or political content with people in my social networks (e.g., in Facebook, Twitter etc.),” “Discussed social or political issues on the internet”; Civic engagement with three items (Cronbach’s α = 0.67): e.g., “Volunteered or worked for a social cause (children/the elderly/refugees/other people in need/youth organization),” “Participated in a concert or a charity event for a social or political cause”.

The emotional side of civic and political engagement was measured through Trust (political and interpersonal) (EFA, ML one factor solution, 38.0% variance explained; Cronbach’s α = 0.61): “I trust the European Union,” “I trust the national government,” “Most people can be trusted,” from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree); and Alienation (4-item; EFA, ML one factor solution, 53.6% variance explained; Cronbach’s α = 0.82): “People like me do not have opportunities to influence the decisions of the European Union,” “It does not matter who wins the Portuguese elections, the interests of ordinary people do not matter,” rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Given the relationship between political trust and political alienation (Fox, 2015), feelings of political powerlessness, distrust of political institutions and other people are considered key in the emotional engagement and triggers of political action. An emotional conception of trust, closely linked to the field of political psychology, understands “political trust [as] an affective attitude–a relatively enduring set of feelings and emotions–that individuals adopt (…) when it is impossible for them to know whether or not political institutions will act consistently with their interests” (Dodsworth et al., 2020, p. 5). We agree that acknowledging the emotional dimension of the act of trusting (Lahno, 2001) implies going beyond the potential pitfalls of conceiving trust as grounded on the actors’ information-based strategic choices. It is argued that a rationalist reductionism of trust hampers a nuanced appreciation of the complexities of political agency, overlooking trust as an emotional attitude that tends to influence deliberative (cognitive) processes (Lahno, 2001, p. 177). Indeed, research studies exploring the role of both political and social trust in political participation highlight the emotional and psychological states entailed in either trusting or distrusting (e.g., Chen, 2018; Bertsou, 2019).

The construct of cognitive engagement (with civic and political issues) was assessed through political interest and political information as two dimensions related to being attentive to and interested in political affairs, classical predictors of participation (e.g., Verba et al., 1995). Political Interest (EFA, ML one factor solution, 59.6% variance explained; Cronbach’s α = 0.85) was measured using a 4-item scale, used in other international studies (IEA Cived, 2002): e.g., “How interested are you in politics?,” “How interested are you in European Union related topics?”. The response’s format ranged from 1 (extremely interested) to 5 (not interested at all). Political Information (EFA, ML one factor solution, 36.5% variance explained; Cronbach’s α = 0.67) comprised four items: “[being a good EU citizen implies] to be informed about what is going on in European Union,” “I feel that I have a pretty good understanding of important societal issues.” This scale combines items from the dimension of citizenship conceptions (Torney-Purta et al., 2001) and political efficacy (IEA Cived, 2002), in the extent that they evaluate the active search for information and the importance attributed to being politically informed.

In the analyses of variance (ANOVA), we included as independent variables a range of personal and socio-demographic features that the literature indicates as influencing civic and political participation: age, income, religiosity, life satisfaction and educational plans. Age (how old are you?) is one of the classical predictors of civic and political engagement, deemed fundamental when studying variance in youth participatory patterns (Barrett and Zani, 2015). Likewise, the effect of family income on youth civic and political participation is indicated as an important measure of socioeconomic status (Verba et al., 1995). In line with previous studies (Malafaia et al., 2017), income was assessed by asking the youngsters’ perception about the income of their household covering the needs of its members (1 = not at all; 2 = rarely; 3 = sometimes; 4 = completely), given the likelihood that young people cannot (or may feel uncomfortable to) directly assess their parents’ income. Religiosity (to what extent are you religious?) and life satisfaction (on the whole, how satisfied are you with the life you lead?) were included as they proved to be related to the likelihood of being civic and politically active (e.g., Crystal and DeBell, 2002). Finally, youngsters were asked about their educational plans (how many years of education do you plan to complete?) in a scale ranging from 1 (lower secondary education) to 5 (higher education), as it can be considered an indicator of success in formal education, related to political engagement (Nie et al., 1996).

The attitudes towards immigrants and refugees, as well as democratic support, were included as important socio-political variables. In addition, the relationship with the media (traditional and alternative media) was considered.

Attitudes towards immigrants and refugees are assessed by two separate items: “immigrants tend to take job opportunities from local people” and “I feel that our country has enough economic problems and that is why we cannot afford to help refugees.” These two items are based on the tolerance scale used in previous national (Menezes et al., 2012) and international studies (Barrett and Zani, 2015).

Democratic support, an important dimension in the socio-political development, was measured by the item “Democracy is the best system of government that I know” (1- strongly disagree; 5—strongly agree). This dimension is based on previous research (e.g., IEA Cived, 2002) and used in studies with similar samples (Menezes et al., 2012). This specific item proved to be particularly intelligible for young participants (Macek et al., 2018).

Trust in professional and alternative media was assessed through the two following items: “I consider most professional media–TV, online, radio or print–as trustworthy sources of news and information” and “I consider alternative online media as more trustworthy sources of news and information than professional media.” The responses ranged from ‘strongly disagree” 1) to ‘strongly agree” (5). There is evidence that professional and alternative media may play an intertwined role on media consumption, rather than a dualistic one, but variations in the combination of both types of media are related to different expectations concerning alternative media (Macek et al., 2018).

European and national identification were assessed based on the Utrecht-management of identity commitments scale (Crocetti et al., 2010). European and national identification scales were subjected to EFA and each results in a three factor solution (EU, EFA, ML three factor solution, 48.0% variance explained; national, EFA, ML three factor solution, 58.0% variance explained) consistent with the original instrument and representing: European/national commitment with three items (EU: Cronbach’s α = 0.73; National: Cronbach’s α = 0.83): e.g., I feel strong ties toward Europe/Portuguese; ii) European/national exploration with three items (EU: Cronbach’s α = 0.75; National: Cronbach’s α = 0.81): e.g., I often think about what it means to be European/Portuguese; iii) European/national reconsideration with three items (EU: Cronbach’s α = 0.63; National: Cronbach’s α = 0.74): e.g., My feelings about Europe/Portugal are changing.) The response format was a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1) strongly disagree to 5) strongly agree.

From the k-means clustering used to classify the participants according to the behavioural, emotional and cognitive forms of engagement, a four-cluster solution was found to be the best. Figure 1 portrays these results. The first cluster was interpreted as Alienated [n = 250]: low scores on the behavioural engagement (namely on activism: M = 1.10), very low levels of emotional engagement (scoring particularly high on alienation: M = 4.08) and medium levels of cognitive engagement (e.g., interest: M = 3.14). The second cluster suggested a Passive profile [n = 286]: low levels of behavioural engagement (e.g., online: M = 1.67), medium values on the emotional dimension (e.g., alienation: M = 2.35) and medium levels on the cognitive facet (e.g., information: M = 3.77). The Disengaged profile emerged in the third cluster [n = 256]: low levels in all variables measuring the behavioural, emotional, and cognitive engagement. Finally, the fourth cluster was labelled as Engaged [n = 159]: presenting the highest levels in all variables measuring the behavioural engagement (e.g., civic: M = 3.45), medium values of emotional engagement (e.g., alienation: M = 3.36) and medium-high levels of cognitive engagement (e.g., information: M = 3.80).

The analysis of variance conducted with the individual socio-demographic variables revealed effects of clusters [Pillai’s Trace = 0.086, F (15,1374) = 2.706, p = 0.000], indicating significant differences regarding age [F = 7.02, p = 0.000] and income [F = 3.54, p = 0.015]. Pairwise comparisons show statistically significant age differences between the alienated and the disengaged profile (p = 0.016), and between the engaged profile and both the passive (p = 0.017) and the disengaged (p = 0.000) profiles. As depicted in Figure 2, the youngsters in the engaged profile are older than the youngsters from the other clusters, with participants in the alienated profile also being older than the disengaged ones. Regarding income, significant differences were observed between the alienated and the engaged group, with youngsters that exhibit an alienated profile of engagement experiencing more financial problems at home–Figure 3.

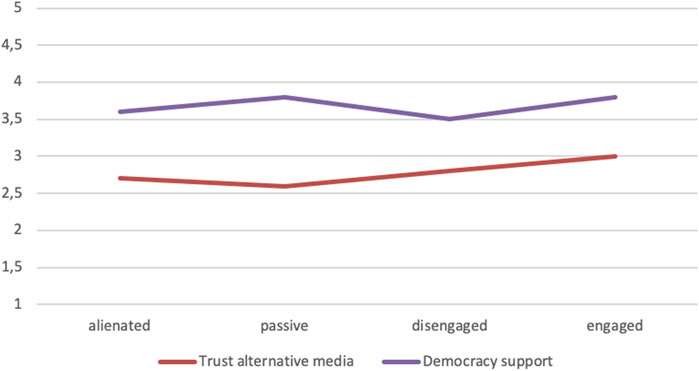

The profiles of youth engagement display significant effects on how youngsters relate with media, Others and democracy [Pillai’s Trace = 0.104, F (15,2757) = 6.584, p = 0.000]. Regarding the media, the engagement clusters only relate significantly with the trust in alternative media [F = 8.456, p = 0.000]. Results reveal that youngsters from the engaged cluster display significantly more trust in the alternative online media as sources of information than both the alienated and the passive groups (p = 0.001, p = 0.000). Interestingly, the disengaged group scores higher than the passive group (p = 0.046) in considering alternative media as more trustworthy than professional media (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. Democracy support and trust on alternative media ‐ relationship with profiles of youth engagement.

The support of democracy as the best system of government, statistically related to the clusters [F = 7.156, p = 0.000], is higher on the engaged group, which exhibits significantly higher values than the groups characterized by alienated (p = 0.012) and disengaged (p = 0.001) profiles, which show the lowest scores in support to democracy (Figure 4).

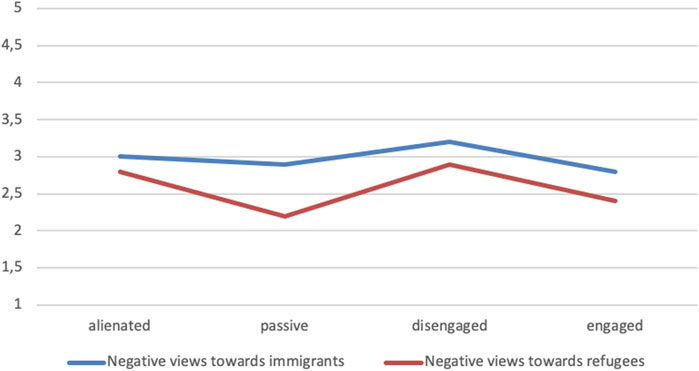

Results indicate that there is a statistically significant relationship between the profiles of youth engagement and the negative views towards immigrants [F = 3.189, p = 0.023] and refugees [F = 15.520, p = 0.000], with the disengaged group scoring significantly higher than the engaged group (p = 0.021) on considering that ‘immigrants have a tendency to take job opportunities from local people’. When it comes to the negative views towards refugees, the alienated and the disengaged clusters feel more strongly than the other groups that due to the economic problems faced by Portugal, the country cannot afford to help refugees (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. Negative views towards immigrants and refugees–relationship with profiles of youth engagement.

The profiles of youth engagement are significantly related with the variables of European and national identification [Pillai’s Trace = 0.235, F (18,2787) = 13.142, p = 0.000], particularly on the three scales of the European identity (commitment [F = 20.883, p = 0.000], exploration [F = 45.011, p = 0.000] and reconsideration [F = 8.886, p = 0.000]), and on two scales of national identification (commitment [F = 9.978, p = 0.000] and exploration [F = 71.465, p = 0.000]. As displayed in the Figure 6, the results show that the respondents’ sense of commitment to Europe is higher for the passive and the engaged groups. Interestingly, the level of European commitment of the passive group is the highest, being significantly different from that of the engaged (p = 0.023) and the disengaged profiles (p = 0.000). Regarding the youngsters’ level of exploration of EU identity, both the alienated and the passive profiles seem more dedicated to exploring the meanings and implications of being a European citizen than the disengaged youth (p = 0.000; p = 0.000, respectively); however, engaged youngsters are the ones who score higher on EU exploration. Similarly, concerning the European reconsideration, the young people from the alienated group report significantly more often that their feelings and views about Europe are changing than the disengaged group (p = 0.001), with the engaged one scoring higher than both the passive (p = 0.028) and the disengaged group (p = 0.000).

The clusters of engagement are also significantly related with the national identification, with the results revealing that the passive profile scores significantly higher than the alienated (p = 0.007) and the disengaged profile (p = 0.000) when it comes about feeling proud of the Portuguese nationality (Figure 7). Likewise, the young participants belonging to the disengaged profile show themselves significantly less prone to explore the meanings of being Portuguese and search for information about Portugal, compared to the groups of alienated engagement (p = 0.000), the passive group (p = 0.000) and the engaged group (p = 0.000).

This article’s results reinforce the need to account for participatory diversity, which necessarily implies broad typologies that include kinds of engagement which, although not necessarily and directly classified as political participation, might be of great importance in understanding it, as they are “pre-political” or “stand-by” kinds of engagement (Ekman and Amnå, 2014). Moreover, accounting for the youth engagement profiles contributes to gaining insight on the pathways of engagement through which young people are currently making (and meaning-making) European democratic citizenship, which in turn also sheds light on their political attitudes and democratic stances.

Considering our results, the most worrisome engagement profile is, in all likelihood, the disengaged one. The young people in this cluster seem to correspond to those at the very bottom of the democratic table: they do not trust, do not care and do not participate. The combination of both emotional and cognitive disengagement, in addition to the absence of participation, emerges as a potentially explosive mix for this very young group. They are not enthusiastic about the democratic system, they identify little with both the EU and their national country, and tend to express negative views towards immigrants and refugees. These youngsters may then represent a potential target group for populist agendas, also considering their trust on the information conveyed by online non-professional media. However, they may also be regarded as a kind of ground zero of involvement that cuts both ways: hardly reachable both by democratic participatory initiatives and by nationalist kinds of narratives. In other words, these youngsters’ profile seems to be mostly characterised by apathy: feeling out of the political world and (probably, because of it) placing themselves out of the (democratic) system, which, of course, may lead them to dispositions closer to radically anti-democratic attitudes. At the same time, one cannot avoid interpreting this kind of disengagement as a natural result of a state of affairs that most often disregards youth as political competent agents in a context which, additionally, is far from thriving in what regards future prospects of education and employment (OECD, 2015; Bessant, 2018).

Although the results concerning the disengaged profile seem to corroborate the link between trust in alternative media and negative attitudes towards the EU (Macek et al., 2018), the engagement profile defies the literature in this regard. Highly engaged, these youngsters present themselves as very supportive of the migrants’ rights, specially committed to the European identity and trusting alternative media as well. This calls the attention to the role of these new online vehicles of political information for those Millennials associated to a knowledgeable citizenry, with cultural and economic resources for engagement. Sloam and Henn (2019) emphasise the cosmopolitan left orientation associated with a highly educated and middle-class youth attracted by a cosmopolitan belief in human rights and an inclusive society, even if this orientation takes different shapes depending on national political and social contexts. We can well be facing the Portuguese version of the cosmopolitan left youth, for whom, similarly to youngsters from Italy and United Kingdom, non-traditional media is associated to socially liberal and left-wing politics, alongside horizontal forms of engagement (Ibid). In fact, the prominent role of the new media in prompting repertoires of action towards the promotion of political democratic alternatives, namely in countries that witnessed the raise in anti-austerity movements, is reported, including concerning the Portuguese case (e.g., Baumgarten, 2013). Thus, we may be encountering an older group of young people whose development of politicized engagement was framed by the context of austerity, which, in some cases, occurred during their most plastic developmental period–adolescence. This now translates into their commitment with European values, while also being aware of possible contradictions and implications of what European citizenship means (given their scores on EU exploration and reconsideration). The passive group of youngsters, in its turn, shows moderate cognitive engagement and is considerably engaged in emotional terms, but does not take action. Compared to the disengaged group, it is the intentionality in the lack of personal mobilization for civic and political purposes that seems to characterize the passive profile. They seem to be close to what Amnå and Ekman (2015) called the stand-by citizens, being interested and informed, caring about electoral results and believing they could perhaps make a difference if the political world would welcome them and/or if circumstances warrant it. They are politically alert and committed to their national and European identity, supporting the idea that Portugal should play its part in welcoming refuges.

Considering the mutability of the repertoires and patterns of engagement (O Tool et al., 2015), the passive group can be the preceding state (or the younger version) of the engaged group–this latter, older group, which corresponds to a profile of young people who lived under what can be considered an activation set of conditions. Yet, in this train of thought, this passive profile can also evolve into an alienated one. The youngsters from the alienated type of engagement are not completely indifferent to the meanings of being a European and a Portuguese citizen, even if they tend to not commit to any of those identities, showing themselves estranged from democracy and its tenets. It should be noted, in this regard, the emotional dimensions are different on the passive and alienated profiles of engagement and economic deprivation can play a role in it. The youngsters from the alienated group show medium levels of cognitive political awareness–reflected on their involvement in exploring their European and national identity–which seems to separate them from political apathy (Dahl et al., 2018). However, the low socioeconomic background characterising this profile and its salient emotional disengagement, related to a low support of democracy and low levels of national and European identification, calls for wider concerns. This seems to be a group that–in Sloam and Henn (2019) terms–is directly opposed to the aforementioned young cosmopolitans, in the extent that they usually come from poor backgrounds, stand on the dark side of the digital divide, are likely to react negatively to cultural diversity and immigration and, if the conditions are there, may be attracted by authoritarian-nationalist causes. As noted, “the emergence of the new left cosmopolitan group of young people has a mirror-image in the appearance of an economically-insecure left-behind group of young people who don’t share the same progressive values” (Ibid, p. 122).

Both the disengaged and the alienated profiles seem to represent those youth segments at higher risk of developing hostility towards democracy, ultimately, more prone to be involved in populist and radical agendas. Socialisation contexts, such as the school, can play an important role in scaffolding youth political agency by transforming the disengagement and passivity of the younger groups into democratic dispositions. As educational resources and political literacy continue to be pivotal for democratic engagement (Amadeo et al., 2002; Menezes et al., 2012; Malafaia et al., 2017), and given that younger citizens routinely claim to know little about how political world works (Malafaia et al., 2021; Sloam and Henn, 2019), it is important that school education promotes the conveyance and discussion of political issues. Indeed, the levels of cognitive disengagement are particularly problematic in the disengaged profile and, therefore, meaningful opportunities to engage civic and politically, supporting young students in building and widening their participatory experiences, should be promoted. In parallel, politicians must care. Not only during electoral periods, but permanently. Young people must be acknowledged as political agents, and the youth with these profiles should be intentionally mobilised. If they are never asked to participate, they probably will not (Verba, et al., 1995). Consequently, it is very likely they remain untargeted by any political mobilisation effort when they grow older (Hooghe and Stolle, 2003). The alienated profile, corresponding to an older group, may represent an even bigger challenge, with more risks of skipping the radar of political efforts. Considering the recent austerity environment in Portugal, and the looming crisis in the horizon, with young people being greatly affected, the alienated profile may well be revealing the long-term social, economic and political consequences that continues to be felt, most hardly on those with low incomes, fragile social networks and deprived backgrounds.

This article contributes to understanding the breadth of profiles in youth civic and political engagement and the diversity characterising participatory youngsters, while adding to the still incipient body of literature problematising non-participation and political passivity (e.g., Amnå and Ekman, 2015; Weiss, 2020). By exploring how emotional, cognitive and behavioural dimensions converge on dis/engagement profiles, we have shed light on how topical debates today (e.g., refugees’ support, European identity) mostly resonate with the young people from privileged economic backgrounds, regardless of their levels of political action (engaged and passive groups). Therefore, the interaction between individuals’ material conditions and their emotional political engagement seems crucial to be accounted for if the attraction to anti-European and right-wing populist agendas are to be prevented. Thus, contrary to what has been claimed in political and educational policies (e.g., Council of Europe, 2017; European Commission), the promotion of more information and participation alone is not enough. It is fundamental to address the problems of distrust towards political institutions and of lack of subjective personal agency regarding political issues. The neglect of the youth’s political ownership, which continues to emerge both in socio-political (Pontes et al., 2018) and academic narratives (Banaji, et al., 2018), needs to be tackled.

Future studies may include the combination of quantitative self-reports (questionnaires) with other methods, namely qualitative ones–either in group (focus group discussions) or in context (ethnography) for instance –, in order to gain access to the youngsters’ perspectives and experiences, deepening the understanding of the conditions in which diverse modes of engagement are rooted and develop. Further research focused on the different engagement profiles is needed to understand the factors triggering this diversity, the kinds of practices and contextual dimensions framing different profiles and how–if at all–different profiles are changing both individually and across different cultural contexts.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: the files are in Zenodo online repository under the name “CATCH-EyoU: Processes in Youth’s Construction of Active EU Citizenship: Criss. national Longitudinal (Wave 1 and 2) Questionnaires.” The files used are part of a larger dataset including seven other European countries and are currently under embargo until July 19, 2023.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Board of the Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences of the University of Porto. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

CM participated in the data collection, in the data analysis and wrote the main parts of the article. PF was involved in data analysis and discussion, and in revising the article. IM supervised the whole study design, contributing to the planning of the article and its revision.

This research was financed under the scope of the “CATCH-EyoU—Constructing AcTive CitizensHip with European Youth: Policies, Practices, Challenges and Solutions,”funded by the European Union, Horizon 2020 Programme. Grant Agreement n° 649538; http://www.catcheyou.eu/

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Allen, M., and Ainley, P. (2011). Lost Generation? New Strategies for Youth and Education. London: Continuum Publishing Corporation.

Amadeo, J-A., Torney-Purta, J., Lehmann, R., Husfeldt, V., and Nikolova, R. (2002). Civic Knowledge and Engagement: An IEA Study of Upper Secondary Students in Sixteen Countries. Amsterdam: IEA.

Amnå, E., and Ekman, J. (2014). Standby Citizens: Diverse Faces of Political Passivity. Eur. Pol. Sci. Rev. 6 (2), 261–281. doi:10.1017/S175577391300009X

Amnå, E., and Ekman, J. (2015). “Standby Citizens: Understanding Non-participation in Contemporary Democracies,” in In Political and Civic Engagement: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Editors M. Barrett, and B. Zani (London and New York: Routledge), 98–108.

Appadurai, A. (2017). “O cansaço da democracia,” in O grande retrocesso: Um debate internacional sobre as grandes questões do nosso tempo. Editor H. Geiselberger (Lisboa: Editora Objetiva), 17–32.

Banaji, S., Mejias, S., Kouts, R., Piedade, F., Pavlopoulos, V., Tzankova, I., et al. (2018). Citizenship's Tangled Web: Associations, Gaps and Tensions in Formulations of European Youth Active Citizenship across Disciplines. Eur. J. Develop. Psychol. 15 (3), 250–269. doi:10.1080/17405629.2017.1367278

Barrett, M. (2015). “An Integrative Model of Political and Civic Participation: Linking the Macro,” in Social and Psychological Levels of Explanation” in Political and Civic Engagement: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Editors M. Barrett, and B. Zani (London and New York: Routledge), 162–188.

Barrett, M., and Zani, B. (2015). Political and Civic Engagement: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. London and New York: Routledge.

Baumgarten, B. (2013). Geração à Rasca and beyond: Mobilizations in Portugal after 12 March 2011. Curr. Sociol. 61 (4), 457–473. doi:10.1177/0011392113479745

Bertsou, E. (2019). Rethinking Political Distrust. Eur. Pol. Sci. Rev. 11 (2), 213–230. doi:10.1017/S1755773919000080

Bessant, J. (2018). Young Precariat and a New Work Order? A Case for Historical Sociology. J. Youth Stud., 21, 780, 798. doi:10.1080/13676261.2017.1420762

Biesta, G., and Lawy, R. (2006). From Teaching Citizenship to Learning Democracy: Overcoming Individualism in Research, Policy and Practice. Cambridge J. Edu. 36 (1), 63–79. doi:10.1080/03057640500490981

Bobbio, N. (1995). Direita e esquerda: Razões e significados de uma distinção política. Lisboa: Presença.

Cammaerts, B., Bruter, M., Banaji, S., Harrison, S., and Anstead, N. (2015). Youth Participation in Democratic Life: Stories of hope and Disillusion. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cepernich, C. (2015). “Emotion in Politics,” in The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication. Editor G. Mazzoleni (John Wiley & Sons).

Chen, Y. (2018). The Influence of Political Trust and Social Trust on the Political Participation of Villagers: Based on the Empirical Analysis of 974 Samples in 10 Provinces. Jss 06, 235–248. doi:10.4236/jss.2018.66021

Council of Europe, (2017). Learning to Live Together. Council of Europe Report on the State of Citizenship and Human Rights Education in Europe. Retrieved from: https://rm.coe.int/the-state-of-citizenship-in-europe-e-publication/168072b3cd. (Accessed February 3, 2019).

Crocetti, E., Schwartz, S. J., Fermani, A., and Meeus, W. (2010). The Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U-MICS). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 26 (3), 172–186. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000024

Crystal, D. S., and DeBell, M. (2002). Sources of Civic Orientation Among American Youth: Trust, Religiious Valuation, and Attributions of Responsibility. Polit. Psychol. 23 (1), 113–132. doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00273

Dahl, V., Amnå, E., Banaji, S., Landberg, M., Šerek, J., Ribeiro, N., et al. (2018). Apathy or Alienation? Political Passivity Among Youths across Eight European Union Countries. Eur. J. Develop. Psychol. 15 (3), 284–301. doi:10.4324/9780429281037-4

de Moor, J. (2016). Lifestyle Politics and the Concept of Political Participation. Acta Politica 52 (2), 179–197.

Della Porta, D. (2017). “Política progressista e política regressiva no neoliberalismo tardio,” in O grande retrocesso: Um debate internacional sobre as grandes questões do nosso tempo. Editor H. Geiselberger (Lisboa: Editora Objetiva), 63–82.

Diamond, L. (2015). Facing up to the Democratic Recession. J. Democracy 26 (1), 141–155. doi:10.1353/jod.2015.0009

Dimitriadou, E., Dolničar, S., and Weingessel, A. (2002). An Examination of Indexes for Determining the Number of Clusters in Binary Data Sets. Psychometrika 67, 137–159. doi:10.1007/bf02294713

Dodsworth, S., Cheeseman, N., and May, (2020). Political Trust: The Glue that Keeps Democracies Together. Birmingham: Westminster Foundation for Democracy. Retrieved from: https://www.wfd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/WFD_May2020_Dodsworth_Cheeseman_PoliticalTrust.pdf.

Eckstein, K., Noack, P., and Gniewosz, B. (2013). Predictors of Intentions to Participate in Politics and Actual Political Behaviors in Young Adulthood. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 37 (5), 428–435. doi:10.1177/0165025413486419

Ekman, J., and Amnå, E. (2012). Political Participation and Civic Engagement: Towards a New Typology. Hum. Aff. 22, 283–300. doi:10.2478/s13374-012-0024-1

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2017). Citizenship Education at School in Europe – 2017. Eurydice Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Fernandes-Jesus, M., Malafaia, C., Ferreira, P., Cicognani, E., and Menezes, I. (2012). The many Faces of Hermes: The Quality of Participation Experiences and Political Attitudes of Migrant and Non-migrant Youth. Hum. Aff. 22, 434–447. doi:10.2478/s13374-012-0035-y

Flanagan, C. (2013). Teenage Citizens: The Political Theories of the Young. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Fox, S. (2015). Apathy, Alienation and Young People: The Political Engagement of British Millennials. Retrieved from: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/30532/1/Final%20Corrected%20Version%20-%20Apathy%2C%20Alienation%20and%20Young%20People%20The%20Political%20Engagement%20of%20British%20Millennials.pdf. (Accessed June 13, 2020).

Hansen, P. (1998). Schooling a European Identity: Ethno‐cultural Exclusion and Nationalist Resonance within the EU Policy of "The European Dimension of Education". Eur. J. Intercultural Stud. 9 (1), 5–23. doi:10.1080/0952391980090101

Henn, M., Weinstein, M., and Forrest, S. (2005). Uninterested Youth? Young People's Attitudes towards Party Politics in Britain. Polit. Stud. 53 (3), 556–578. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2005.00544.x

Henn, M., Weinstein, M., and Wring, D. (2002). A Generation Apart? Youth and Political Participation in Britain. The Br. J. Polit. Int. Relations 4 (2), 167–192. doi:10.1111/1467-856X.t01-1-00001

Hooghe, M., and Stolle, D. (2003). Age Matters: Life-Cycle and Cohort Differences in the Socialisation Effect of Voluntary Participation. Eur. Polit. Sci. 2 (2), 49–56. doi:10.1057/eps.2003.19

Jain, A. K. (2010). Data Clustering: 50 Years beyond K-Means. Pattern Recognition Lett. 31, 651–666. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2009.09.011

Kahne, J., Crow, D., and Lee, N.-J. (2013). Different Pedagogy, Different Politics: High School Learning Opportunities and Youth Political Engagement. Polit. Psychol. 34 (3), 419–441. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00936.x

Lahno, B. (2001). On the Emotional Character of Trust. Ethical Theor. Moral Pract. 4, 171–189. doi:10.1023/A:1011425102875

Lamprianou, I. (2013). “Contemporary Political Participation Research: A Critical Assessment,” in Democracy in Transition: Political Participation in the European Union. Editor K. N. Demetriou (Berlin: Springer-Verlag), 21–42. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-30068-4_2

Macek, J., Macková, A., Pavlopoulos, V., Kalmus, V., Elavsky, C. M., and Šerek, J. (2018). Trust in Alternative and Professional media: The Case of the Youth News Audiences in Three European Countries. Eur. J. Develop. Psychol. 15 (3), 340–354. doi:10.1080/17405629.2017.1398079

Malafaia, C., Neves, T., and Menezes, I. (2017). In-between Fatalism and Leverage: The Different Effects of Socioeconomic Variables on Students’ Civic and Political Experiences and Literacy. J. Soc. Sci. Edu. 16, 43. doi:10.4119/UNIBI/jsse-v16-i1-1587

Malafaia, C., Neves, T., and Menezes, I. (2021). The gap between Youth and Politics: Youngsters outside the Regular School System Assessing the Conditions for Be(com)ing Political Subjects. Young, 110330882098799–19. doi:10.1177/1103308820987996

Marsh, D., O'Toole, T., and Jones, S. (2007). Young People and Politics in the UK: Apathy or Alienation? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mathé, N. E. H. (2018). Engagement, Passivity and Detachment: 16-Year-Old Students' Conceptions of Politics and the Relationship between People and Politics. Br. Educ. Res. J. 44 (1), 5–24. doi:10.1002/berj.3313

Mazzoni, D., Albanesi, C., Ferreira, P. D., Opermann, S., Pavlopoulos, V., and Cicognani, E. (2018). Cross-border Mobility, European Identity and Participation Among European Adolescents and Young Adults. Eur. J. Develop. Psychol. 15 (3), 324–339. doi:10.1080/17405629.2017.1378089

Menezes, I., Ribeiro, N., Fernandes-Jesus, M., Malafaia, C., and Ferreira, P. (2012). Agência e participação cívica e política: Jovens e imigrantes na construção da democracia. Porto: Livpsic.

Nie, N. H., Junn, J., and Stehlik-Barry, K. (1996). Education and Democratic Citizenship in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2018). Cultural Backlash: The Rise of Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Norris, P. (2004). “Young People and Political Activism: From the Politics of Loyalties to the Politics of Choice?” in Civic Engagement in the 21st Century: Toward a Scholarly and Practical Agend, University of Southern California, October 1–2, 2004. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Pippa-Norris-2/publication/237832623_Young_People_Political_Activism/links/569153d708aee91f69a50822/Young-People-Political-Activism.pdf. (Accessed May 20, 2019)

Oser, J. (2017). Assessing How Participators Combine Acts in Their "Political Tool Kits": A Person-Centered Measurement Approach for Analyzing Citizen Participation. Soc. Indic Res. 133 (1), 235–258. doi:10.1007/s11205-016-1364-8

O’Toole, T. (2015). “Beyond Crisis Narratives: Changing Modes and Repertoires of Political Participation Among Young People,” in Politics, Citizenship and Rights. Editors K. Kallio, S. Mills, and T. Skelton (Singapore: Springer), 1–15.

Pattie, C., Seyd, P., and Whiteley, P. (2003). Citizenship and Civic Engagement: Attitudes and Behaviour in Britain. Polit. Stud. 51, 443–468. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00435

Pontes, A., Henn, M., and Griffiths, M. (2018). Towards a Conceptualization of Young People's Political Engagement: A Qualitative Focus Group Study. Societies 8, 17. doi:10.3390/soc8010017

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ribeiro, N., Malafaia, C., Neves, T., and Menezes, I. (2016). Immigration and the Ambivalence of the School: Between Exclusion and Inclusion of Migrant Youth. Urban Edu., 1–29. doi:10.1177/0042085916641172

Ribeiro, N., Neves, T., and Menezes, I. (2017). An Organization of the Theoretical Perspectives in the Field of Civic and Political Participation: Contributions to Citizenship Education. J. Polit. Sci. Edu. 13 (4), 426–446. doi:10.1080/15512169.2017.1354765

Sloam, J., and Henn, M. (2019). Youthquake 2017: The Rise of Young Cosmopolitans in Britain. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sloam, J. (2014). New Voice, Less Equal. Comp. Polit. Stud. 47 (5), 663–688. doi:10.1177/0010414012453441

Sloam, J. (2007). Rebooting Democracy: Youth Participation in Politics in the UK. Parliamentary Aff. 60 (4), 548–567. doi:10.1093/pa/gsm035

Steinley, D. (2006). K-means Clustering: A Half-century Synthesis. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 59, 1–34. doi:10.1348/000711005X48266

Taylor, V., and Van Dyke, N. (2004). Get up, Stand up’: Tactical Repertoires of Social Movements”,” in The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements. Editors D. A. Snow, H-P. Kriesi, and S. A. Soule (New Malden, MA: Blackwell Publisher), 262–93.

Teorell, J., Torcal, M., and Montero, J. R. (2007). “Political Participation: Mapping the Terrain,” in Citizenship and Involvement in European Democracies: A Comparative Analysis. Editors J. W. van Deth, J. R. Montero, and A. Westholm (London and New York: Routledge), 358–381. doi:10.4324/9780203965757-24

The Economist Intelligence Unit (2019). Democracy Index 2018: Me Too?: Political Participation, Protest and Democracy. Retrieved from: https://www.eiu.com/n/democracy-index-2018/. (Accessed June 1, 2020).

The Economist Intelligence Unit (2021). Democracy Index 2020: In Sickness and in Health. Retrieved from: https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2020/. (Accessed June 18, 2021).

Torney-Purta, J., Lehmann, R., Oswald, H., and Schulz, W. (2001). Citizenship and Education in Twenty-Eight Countries: Civic Knowledge and Engagement at Age Fourteen. Amsterdam: IEA.

Van Deth, J. W. (2014). A Conceptual Map of Political Participation. Acta Polit. 49, 349–367. doi:10.1057/ap.2014.6

Van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., and Spears, R. (2008). Toward an Integrative Social Identity Model of Collective Action: A Quantitative Research Synthesis of Three Socio-Psychological Perspectives. Psychol. Bull. 134, 504–535. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504

Verba, S., and Nie, N. H. (1972). Participation in America: Political Democracy and Social Equality. New York: Harper & Row.

Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., and Brady, H. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Harvard: University Press.

Vrablikova, K., and Linek, L. (2015). ““Explaining the Composition of an Individual’s Political Repertoire: Voting and Protesting”,” in Paper Presented at the MPSA Conference (Chicago, UK. April 16-19.

Weiss, J. (2020). What Is Youth Political Participation? Literature Review on Youth Political Participation and Political Attitudes. Front. Polit. Sci. 2, 1. doi:10.3389/fpos.2020.00001

Keywords: young people, citizenship, dis/engagement, alienation, passivity, european identification, immigration, alternative media

Citation: Malafaia C, Ferreira PD and Menezes I (2021) Democratic Citizenship-in-the-Making: Dis/Engagement Profiles of Portuguese Youth. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:743428. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.743428

Received: 18 July 2021; Accepted: 05 October 2021;

Published: 21 October 2021.

Edited by:

Antonella Guarino, University of Bologna, ItalyCopyright © 2021 Malafaia, Ferreira and Menezes. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Isabel Menezes, aW1lbmV6ZXNAZnBjZS51cC5wdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.