- 1Department of Political Science, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States

- 2Department of Political Science, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

We analyze the relationship between accountability and polarization in the context of the COVID crisis. We make three points. First, when voters perceive the out-party to be ideologically extreme, they are less likely to hold incumbents accountable for poor outcomes via competence-based evaluations. Knowing this, even in the context of major crises, incumbents face weaker incentives to take politically costly measures that would minimize deaths. Second, there is a partisan asymmetry whereby the additional government intrusion associated with effective COVID response can be more politically costly for the right than for the left, because it undercuts the ideological distinctiveness that drives the base-mobilization strategy of the right. Third, this asymmetry generates incentives for politicization of COVID mitigation policies that ultimately lead to partisan differences in mitigation behavior and outcomes. To illustrate this logic, we provide preliminary evidence that COVID death rates are higher in more polarized democracies, and that in one of the most polarized democracies—the United States—COVID deaths have become increasingly correlated with partisanship.

1 Introduction

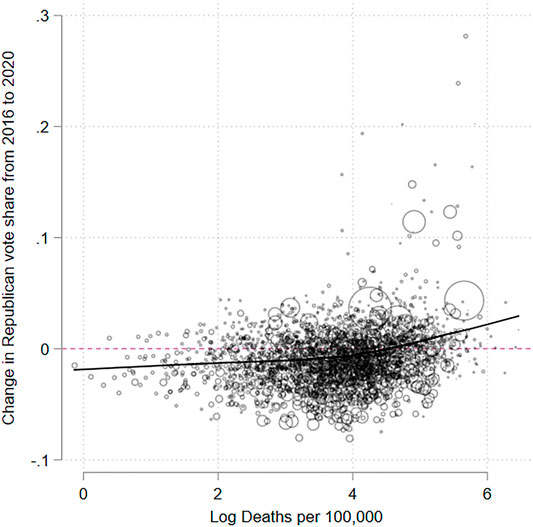

In the 2020 United States presidential election, neither the incumbent presidential candidate nor his political party performed especially poorly in states or counties with higher death rates from COVID-19. On the contrary, in the 100 counties with the highest cumulative COVID death rate on Election Day, on average, Donald Trump’s support increased by four percentage points over 2016. In the 500 counties with the highest death rates, his support increased by over one percentage point on average.1 Joseph Biden’s electoral gains were concentrated not in the urban counties that suffered in the first waves of the pandemic or the rural counties that suffered in the deadly third wave, but rather, in the suburban counties that never experienced high death rates. Meanwhile, governors of states with very high COVID death rates have maintained surprisingly high approval ratings, and have even been celebrated as candidates for higher office. Presiding over an unusually high pandemic death rate is evidently not a career-killer for American elected officials.

Consider also the case of Spain. Isabel Diaz Ayuso, leader of the regional government in Madrid, secured her election on May 2021. Despite presiding over catastrophic outcomes in nursing homes, difficulties in health policy management, and one the highest comparative death counts in Spain, she secured a massive electoral victory against a fragmented left.

These patterns are puzzling from the perspective of democratic accountability theory. The provision of basic security, the protection of life in the face of a major health risk, is perhaps the most basic responsibility for rulers. People dying in larger numbers constitutes an easily observable fact, as do differences in death rates across different countries or localities. Failures to limit contact with infected individuals, supply nursing homes or hospitals, or provide procedures and funding to allow schools and hospitals to cope with the consequences of the pandemic worsen outcomes and are, in principle, attributable to incumbents. And yet, in some countries we observe limited electoral punishment or even political gains in areas with high death rates.

This essay explores the possibility that the lack of obvious widespread retrospective voting based on local COVID data is quite understandable in the face of partisan and geographic political polarization. Moreover, we consider the possibility that incumbent politicians in polarized democracies know that they are unlikely to be held accountable for deaths, and as a result, face weak incentives to minimize them. In contrast, incumbent officials in less polarized democracies run a greater risk of being held accountable for deaths, and face stronger incentives to minimize them.

It is too early to draw conclusions about cross-country or cross-locality determinants of policies related to COVID-19, adherence to those policies, or rates of infection or death. The spread of the virus, and government responses, have changed rapidly since the virus emerged, and some of the most important sources of cross-national and within-country variation in rates of infection and death are largely outside the realm of politics and policy. Explanations that look promising today will be proven wrong in a matter of weeks or months. Nevertheless, some relatively stable patterns are emerging, and it is perhaps not too early to begin the tentative process of exploring the political conditions that have shaped governments’ reactions to the virus and conditioned their success or failure. First, some have argued that on average, non-democratic countries have reacted more quickly (Cheibub et al., 2020) and more stringently (Frey et al., 2020) than democracies, and have experienced fewer deaths. According to Cheibub, Hong and Przeworski (2020), there is a trade-off between the minimization of deaths and the preservation of rights—for example, rights to associate, worship, move freely, and pursue economic opportunities—and dictatorships are less constrained by the need to protect those rights. Accordingly, democracies might tolerate more deaths in order to preserve these rights.

Yet as pointed out by Cheibub, Hong and Przeworski (2020), there is considerable heterogeneity in reactions and outcomes among democracies that remains unexplained. This essay explores the notion that elected officials in democracies worry, at least in part, about being punished by voters for deaths. By exploring the conditions under which incumbents are most concerned about electoral penalties for deaths, perhaps we can gain insight into their incentives to promulgate and enforce policies that prevent them. Our analysis assumes high levels of state capacity, an important factor moderating COVID responses (Bosancianu et al., 2020).

We draw upon a very simple political economy setup in which voters’ evaluations of incumbents depend upon their assessments of 1) competence and 2) ideology. In polarized democracies, a large number of voters view the out-party as ideologically far away, and they experience large utility losses when the out-party is in power. Such voters are less likely to rely on retrospective evaluations of competence when forming their evaluations of incumbents. Conversely, in a less polarized democracy, when most voters perceive the parties as ideologically proximate, retrospective evaluations can become crucial. As a result, incumbents in more polarized democracies face weaker incentives to worry about retrospective evaluations, and can continue to focus on ideology even as death rates climb.

In polarized democracies, the trade-off between saving lives and preserving rights or economic prosperity can also map onto preexisting ideological conflicts in pernicious ways. It is tempting for parties of the left to use COVID as an opportunity to further their agenda and please their core supporters. It is tempting for parties of the right to mobilize their core supporters by portraying public health efforts as attacks on their rights or efforts to expand redistribution under false pretenses. If this framing is successful, voters cannot agree on deaths as a valid performance metric. Knowing this, incumbents on the right and left face weak incentives to worry about this metric.

Next, we explore some additional conditions under which incumbents in polarized democracies are less likely to be sensitive to death rates. First, it is easier to escape blame for deaths when members of the out-party control relevant higher- or lower-level offices with authority over public health. Faced with the vexing trade-off between saving lives and protecting rights and livelihoods, perhaps the ideal scenario for an incumbent is to avoid difficult decisions and blame others for both deaths and shutdowns. Second, we highlight the role of viral and political geography in polarized democracies. It is especially tempting for incumbents to avoid hard decisions if deaths are geographically concentrated in areas where the most ideological—and hence least retrospective—voters are concentrated. Incumbents would be most likely to worry about deaths if they were concentrated in pivotal areas with large densities of ideological moderates. However, we discuss examples, including the United States, where this has not been the case. Finally, we explore a dynamic by which, in highly polarized democracies where disease response has been politicized, deaths can come to be increasingly concentrated in the core support areas of the right, where COVID mitigation measures have come to be seen through a lens of ideology rather than competence.

We provide some preliminary and tentative evidence in favor of these subtly different claims about polarization. First, we show that COVID death rates have been higher in democracies where voters view the out-party or parties as more ideologically distant from themselves. Second, we show that death rates have been higher in democracies where supporters of the government and opposition are most dissonant in their assessments of the government’s COVID response. Third, using data from U.S. counties, we demonstrate a growing concentration of COVID deaths in the most overwhelmingly Republican areas.

2 Basic Setup: The Trade-Off Between Competence and Ideology

Let us consider the utility of a representative voter j, with an ideal point of xj on a single, over-arching dimension of politics. The voter’s utility for incumbent candidate i is determined by vi, the perceived competence of incumbent candidate i, as well as the distance between the voter’s ideal point, xj, and the perceived platform of the incumbent candidate, xi:

where a > 0 scales the relative importance of ideology versus competence for the voter. Voter utility for candidate c, the challenger, is determined in the same way:

We are interested in understanding the role of perceived competence of the incumbent: vi. Voters face a well-known problem in collecting unbiased information about incumbent performance, but there is considerable evidence that under some conditions voters react to performance indicators like macroeconomic aggregates, student test scores, property values, or public health outcomes. Negative voter reaction to poor performance is the route through which voters might induce strong, public-spirited efforts by elected officials and generate disincentives for theft or corruption on the part of officials.

Specifically, during a pandemic in which best practices and ideal policy responses are unknown and rapidly evolving, voters might use death rates—especially compared with neighboring or similarly situated countries, provinces, states, or cities, as unvarnished indicators of incumbent competence in combating the pandemic. As with macroeconomic and other indicators, the signal-to-noise ratio indicating the value of death rates as a performance indicator might be low, since a great deal of variance is driven by factors, including hospital infrastructure, the density of living arrangements, contact with travelers, and the emergence of virus variants, that are beyond the immediate control of the incumbent. Nevertheless, inducing fear of punishment for observable poor performance is probably the best accountability mechanism available to voters. Incumbents might fear that sufficiently low values of vi relative to vc will sink their reelection prospects, inducing them to work in the common interest.

In the context of a pandemic, there is no need to resort to the demanding informational assumptions implicit in the economic voting literature (Duch et al., 2008). Despite the noise, the competence metric is simple: are incumbents capable of containing and preventing deaths? Given the prominent media presence of political leaders guiding interventions, we can assume that the two conditions Achen et al. (2017) required for retrospective voting to be feasible apply: 1) voters can plausibly discern a connection between government’s actions and outcomes; and 2) the effects of policy decisions are likely to be intense, immediate, and lasting. So even if voters are fundamentally myopic, the possibility of establishing a link between experiences and incumbents’ policies remains (see Achen et al. (2017), pages 304–306).

Ideology, however, can easily undermine this accountability mechanism in a number of ways. If we fix xi and xc, as a voter becomes ideologically further away from her perceived xi, her distaste for the incumbent grows, and performance indicators become less important in driving her utility. The same is true for candidate c, the potential replacement for candidate i. As voters who are ideologically aligned with the incumbent become more ideologically extreme relative to their perception of xc, they also care more about ideology and less about competence. In this setup, it is easy to see how political polarization might undermine an incumbent’s incentives to minimize deaths from a pandemic using a basic political economy approach to elections.

In the simplest case, imagine that there are just two parties, i and c, and every voter is perfectly ideologically aligned with one of the parties in the sense that her preferences are identical to either xi or xc, and these two clumps of voters and politicians are at −z and z. As z grows, the importance of perceived competence, vi and vc, diminishes, because the ideological distaste of having the other side in office grows. That is to say, as a party system becomes more ideologically polarized, competence-based voting becomes less important. More realistically, the distribution of ideal points among voters is not bimodal, and there are individuals in the middle of the distribution who are closer to the point of indifference between their perception of xi and xc. For these “moderates,” perceived competence is a more important part of their utility function. Another way to think about party system polarization is that these individuals become fewer in number.

Note that in this framework, xi and xc are perceived platforms. Thus, polarization need not be conceived as a process in which voters actually become more extreme in their objective views about, say, taxation or abortion. Rather, it can be understood as a process in which voters come to perceive the out-party as increasingly far from themselves. Cox and Rodden (2021) provide a model in which perceptions of xi and xc emerge from strategic messages sent by the parties about the out-party’s platform on an issue-by-issue basis, exploiting voters’ negativity bias by selectively informing them of the out-party’s position on the issues they care most about, or on issues on which the voter is furthers from the out-party’s platform. In this way, over time, voters can come to see the parties as increasingly extreme—and distasteful—even if voter ideology does not change.

3 Partisan Polarization and Incumbent Incentives: Channels and Context

This logic is relatively clear, but it is perhaps too simplistic in its distinction between ideology and competence. As Cheibub, Hong and Przeworski (2020) point out, democracies must wrestle with the trade-off between saving lives and protecting rights in ways that authoritarian regimes must not. A problem in democracies is that party message-makers face incentives to map the complex trade-offs associated with virus response onto pre-COVID ideological battles. Well-meaning policy proposals by the out-party that are aimed at saving lives can easily be portrayed as extremist power-grabs crafted with the sole purpose of trampling on the rights of members of the in-party. In other words, COVID response becomes yet another opportunity for party elites to mobilize core supporters by increasing their perceived ideological distance to the out-party, which minimizes the role of competence assessments.

But the problem might go well beyond ideology squeezing out competence. Ideology can also cause voters to disagree about the appropriate metric for evaluating vi in a way that is correlated with ideology. Ferejohn (1986) points out that when the electorate is sufficiently heterogeneous, voters are unable to agree on a metric for evaluating competence, and it is not possible to hold incumbents accountable. In this case, those who are ideologically closer to one party might determine that the preservation of jobs and economic activity is the appropriate metric, while supporters of the opposite party might focus on deaths. Moreover, the literature on motivated reasoning explains how highly ideological voters might interpret the same information very differently through a partisan lens (Lavine et al., 2012; Acharya et al., 2018). Above all, supporters of the incumbent can be convinced of any number of reasons to absolve her of responsibility for climbing death rates—especially in a setting where the link between government policy choices and death rates is indeed quite tenuous. Even further, some highly partisan supporters of the incumbent might even become convinced that death rates are fabricated or exaggerated.

All of this suggests several different mechanisms through which incumbents in more polarized democracies seek to escape blame for deaths. Voters might agree that a climbing death rate is a signal of poor performance, but ideology trumps competence for too many voters. And the incumbent’s supporters and detractors might disagree about whether the death rate is indeed something worthy of punishment. We argue that the relationship between polarization and party competition makes these outcomes particularly likely. We focus on three channels: 1) partisan asymmetries when it comes to policy responses to pandemics; 2) how polarization shapes political risks in the crafting of responses to the pandemic; and 3) the moderating role of federalism and political geography.

3.1 Policy Responses and Ideological Asymmetry

Deaths and job losses are two of the most important metrics being used in assessing how countries have responded to the COVID pandemic. Since the virus is transmitted through air in close contact, early in the pandemic, a consensus emerged among public health experts around the importance of imposing restrictions on people’s movements, both internationally and domestically. At the peak of the pandemic, prior to the development of vaccines, such restrictions implied the effective closure of any economic activity that required interpersonal contact. Public and private services, such as education or tourism, travel, any form of production or distribution requiring close contact, were either halted or severely restricted.

As a result, most advanced economies suffered significant GDP contractions and unemployment surges. For incumbents, the dilemma became how to prevent the economy from utter collapse without adding to the death toll. If one thinks of the position adopted by politicians as a continuum going from very lax to very extreme restrictions on economic activity, there is significant variance across countries and localities. Some societies, like Sweden or some US states like Texas or Georgia, opted for limiting restrictions at the expense of the spread of the disease; others, like Australia, responded much more aggressively at times. Virtually all changed their strategies over time as the pandemic evolved, and many attempted to vary their regulations across cities or regions according to the severity of the outbreak.

Regardless of the specific restrictions adopted by each incumbent, early in the pandemic, before the development of vaccines, government responses to COVID involved an unusual amount of public intervention in the economy and society. Countries around the world adopted massive transfers to subnational units, firms, and workers so that they could navigate the economic disruptions caused by the pandemic. Leaders also spearheaded significant investments in physical and technical infrastructures, and the ad hoc regulation of production in key strategic sectors. The resort to the National Defense Act, along with massive public subsidies, in the process of vaccine production in the USA is one of the most prominent examples among many such interventions. Governments also became highly involved, often in new and controversial ways, in attempting to regulate the behavior of businesses and individuals. Sometimes leaders invoked emergency powers with questionable constitutional grounding.

Whether trying to save lives or jobs, a cross-country consensus emerged that a competent COVID response required a significant increase in government regulation, from restrictions on movements and indoor gatherings to the requirements to wear a mask, as well as with a stronger presence of the state in the economy (massive subsidies, higher taxes, higher deficits). This creates an interesting partisan asymmetry: more regulation and a stronger fiscal effort are, arguably, the natural environment for left parties trying to consolidate their bases of support. These are policies that, for the left, work towards the base. These policies are consistent with the party’s long-standing rhetoric, and core and potential voters will perceive them as the natural response to the crisis without much of a second thought.

By contrast, these policy initiatives work against the long-standing rhetoric and deeply held beliefs of the partisan base for the right, both in terms of regulatory restrictions and budgetary efforts. This is true not only of voters with libertarian views, who would see both enhanced regulations and excessive tax-and-spend efforts with a critical eye, but also of more conventional conservative voters who are willing to accept behavioral restrictions on moral grounds (say, on abortion rights) but are fundamentally skeptical of government as a hungry Leviathan that is predisposed to devour the output of people’s hard labor. This asymmetry implies that for a certain kind of anti-government incumbent, a response to the pandemic based solely on competence is an uphill battle against its own core constituency.2 For politicians on the right, to adopt the emerging bundle of consensus COVID mitigation policies in 2020 was to run the risk of being perceived as moving to the left.

To the extent that COVID mitigation policies came to be mapped onto preexisting ideological battles, this happened prior to the development of vaccines or even the emergence of a public health consensus about the importance of masking. It happened during the phase of business shutdowns and expensive relief packages. Our claim is not that anti-vaccine or anti-mask sentiment somehow flows in a coherent way from the bundle of ideas promoted by parties of the right. Indeed, concerns about civil liberties and fear of government overreach have sometimes been emphasized by parties of the left, and parties of the right often emphasize personal responsibility. Moreover, the political base of the right in many countries strongly supports using the authority of the state to compel individuals to comply with the dictates of “law and order,” and one can easily imagine an alternative scenario in which parties of the right embraced a strong government role in regulating behavior, while parties of the left focused on concerns about civil liberties. We do not dispute this. Our claim is that in the crucial early phase of the pandemic, when the ideological mapping of COVID mitigation took shape, the consensus mitigation policies involved severe restrictions on religious institutions, private enterprise, and even family gatherings. These restrictions were quite different in kind from a “law and order” agenda associated with the protection of private property and exchange, and they were extremely unpopular among some core voters of the right. We also recognize the presence of libertarians on the left who are wary of government overreach, but it is important to note that shutdowns were accompanied by massive progressive public efforts to socialize health and economic risks via government programs and transfers that the left could only dream about in normal times.

In sum, to the extent that incumbents and challengers had incentives to map COVID mitigation policies onto existing ideological conflicts, it was parties of the right who had the strongest electoral incentives to develop a narrative of skepticism in the early days of the pandemic. Once the resonance of that narrative had been demonstrated, it made strategic sense to extend it to vaccines and masks.

3.2 Political Risk in Polarized Versus Non Polarized Contexts

The calculus of elites depends primarily on the expected responses by voters. These responses are likely to differ in polarized versus non-polarized environments. Arguably, the very definition of polarization implies that competence weighs less than ideology in voters’ performance assessments. A non-polarized environment is one in which |xi − xc| is relatively small and the weight of vi − vc in voters’ assessments is larger. By contrast, polarization implies both that the distance in terms of ideology between the incumbent and the challenger grows larger and that the importance of ideological consideration relative to competence evaluations is also stronger.

This distinction matters because of the political risks incumbents and challengers face in relation to their core and potential supporters as they engage with the policy responses to the pandemic. Politicians competing in elections want to maximize the size of their coalition by, ideally, both attracting moderates and independents and minimizing the losses through the de-mobilization of core supporters. Our argument suggests that the simultaneous pursuit of both goals is limited by the partisan asymmetry in COVID policy responses and the baseline level of polarization.

To see this, consider first the case of incumbents in a non polarized context in the early days of the pandemic. If the incumbent is on the left, a death-minimizing COVID policy works towards the base. Her expectation will be that the new regulations and expenditures that constitute a competent policy platform will help mobilize the core supporters of the left while attracting moderates if death rates are suppressed. A basic problem is that left-wing incumbents might be tempted to provide extra goodies to their base that are poorly targeted toward COVID relief. However, a large density of potential competence-based voters will place limits on her incentives to do so. Given low levels of polarization in perceived platforms, the opposition has an incentive to appear as competent by showing a more collaborative profile. Expected demobilization by core voters due to their decreasing ideological distinctiveness is small relative to the offsetting concern that intransigence will enhance the incumbent’s competence advantage. In a less polarized democracy, it is important for parties to retain the chance to keep attracting competence-based voters in subsequent contests.

If the incumbent is on the right, the consensus package of COVID measures work against its base. A risk is that vigorous government intervention will demobilize the base by minimizing the perceived ideological distance to the out-party. In a less polarized democracy, perceived incompetence is a bigger electoral threat, and incumbents have incentives to present the combination of restrictions and subsidies as the only plausible response. They will also seek agreement and collaboration across the aisle to share the political costs of the measures. Much like the right in the case of a left incumbent, the main party of the left has incentives to cooperate and appear as a reliable partner when the national interest is at stake. If anything, the left will face incentives to push for a larger and more generous policy package. In either scenario, ideological differences are downplayed and the debate tends toward social responsibility and institutional efficiency in responding to the crisis. In a nutshell, both parties perceive a danger that voters will punish the adoption of extreme ideological positions that undermine the incumbent.

The calculus changes in highly polarized democracies. First consider a left-wing incumbent. As in a less polarized democracy, she can mobilize her base, and enhance voters’ perceptions of ideological distance from the party of the right, with a package of increased regulation and spending. Again, the temptation to sneak non-COVID-related goodies into the relief package is strong, but the countervailing fear of punishment by neutral, competence-based voters is weaker. In the United States, for instance, Democratic elites were quite clear in advertising to their core supporters that the American Rescue Plan went far beyond COVID relief, going so far as to promote it as “one of the most progressive pieces of legislation in American history.”3 For their part, the right-wing opposition faces little incentive to cooperate because they fear the demobilization of core supporters and expect no gains from sharing in policy responses that work against their base’s ideological priors. By assenting to expansive new regulations and expenditures, parties of the right run the risk of undermining their base-mobilization strategy. If their electoral success depends in large part on core supporters who view the left as ideologically distasteful, it makes little sense to dull the parties’ perceived ideological distinctiveness. On the contrary, both parties face incentives to enhance it. As a result, when in opposition in a polarized democracy, the right faces incentives to criticize excessive intervention, challenge spending as a gift to left-leaning interest groups and inefficient redistribution through the back door, accusing left incumbents of trampling on individual rights and turning the cure into a bigger problem than the disease itself.

In the case of right wing incumbents in polarized contexts, the incentives are for weaker restrictions and regulations and lower spending levels. In turn, we expect the left opposition to be combative in denouncing the limits of the response, blaming the incumbents for deaths, and taking every opportunity to demonstrate its ideological distinctiveness.

3.3 Institutional Context: Federalism and Political Geography

Depending on the precise electoral rules and vertical structure of authority, in a polarized democracy, our framework suggests some complex ways in which the geographic distribution of ideology and pandemic deaths might shape voter perceptions, politicians’ incentives, and the effectiveness of COVID response. First of all, in most countries, COVID did not emerge at the same time in all geographic regions. It often emerged in one or a handful of regions, for instance Northern Italy or Southern Germany, or the cities of New York, Detroit, and New Orleans in the United States. As a result, in the initial wave, COVID typically came to be viewed as a region-specific problem. In a polarized democracy, if COVID cases are initially concentrated in the geographic base of the left party, this only magnifies the pernicious logic of polarization described above. The party of the left has even stronger incentives to call for government intervention, and whether it is the incumbent or opposition, an anti-government party of the right has even less incentive to yield to expensive and intrusive policies that are perceived only to benefit the core supporters of the left. The party of the right faces strong incentives to resist COVID mitigation policies, or to insist that they are the responsibility of lower-level governments that are controlled by officials belonging to the party of the left.

The problem does not disappear if COVID emerges in the geographic bailiwick of the right. Imagine that voters only take into consideration local rather than national death rates when assessing vi. If deaths are concentrated in regions where (xj − xi) is large—that is to say, regions where voters perceive the incumbent to be ideologically far away—the incumbent understands that assessments of vi will not matter: relatively few voters are sufficiently moderate to pay attention to competence. Perhaps counter-intuitively, this framework also suggests that if polarization is sufficiently intense, even a concentration of deaths in the incumbent’s core support regions might also not induce punishment, since most voters view the out-party challenger as too distasteful. Deaths are most likely to induce punishment when they occur in regions with large densities of voters who are closer to the point of ideological indifference between the candidates.

This claim is plausible regardless of whether the incumbent in question is a national-level government for whom voters’ retrospective assessments are driven by regional information, or whether the incumbent is a state or provincial official. In a polarized setting, even a lower-level government with substantial authority over public health and high death rates might avoid punishment if he or she presides over an electorate that is dominated by ideological extremists.

This logic of polarization can apply to incumbents on both the left and right. Without paying a political price, left incumbents might push for expensive and expansive programs that are poorly targeted and ultimately ineffective, even while failing to invest in the safety of nursing homes. On the right, once COVID skepticism has been politicized, basic COVID mitigation policies—even including mask-wearing and vaccines—can come to be seen as nefarious leftist schemes. In decentralized systems, local officials can brandish their ideological distance from the out-party by undermining or circumventing regulations by higher-level governments. In a polarized democracy, electoral punishment for high COVID death rates is unlikely in either the core support areas of the left or right, but rather, in areas with large densities of swing voters.

Multi-layered authority also adds additional complexity. A basic problem with divided authority—whether through coalition government, executive-legislative division, or federalism—is that it might undermine accountability by making it difficult for voters to make assessments about vi. The incumbent chief executive can often credibly blame coalition partners, recalcitrant legislators, or lower-level governments for poor performance indicators. In the case of COVID, this problem is especially pronounced when voters were already polarized, the lives-versus-rights trade-off has been effectively politicized by party message-makers, and authority over public health is divided between layers of government. When lower-level governments have significant relevant policy authority and many of those in areas with high death rates are controlled by the party or coalition that is in opposition at the higher level, incumbents at the higher level face incentives to avoid costly policy interventions, allowing it to credibly blame lower-level officials not only for transgressions of rights, but also for deaths.

In democracies where the average voter believes the ideologically non-proximate party or parties to be far away from themselves, we anticipate that competence should be less important in driving voter utility, and as a result, incumbents should be less concerned about punishment and reward for observable performance indicators. In any democracy, as COVID deaths emerge and become publicized, incumbents will begin to worry that deaths will reflect badly on their performance. However, the expected translation of deaths into loss of future electoral support should be weaker in more polarized democracies where voters view the out-party as more ideologically distasteful.

Furthermore, the politicization of COVID mitigation policies can ultimately lead to within-country geographic variation in the implementation of those policies. In extremely polarized democracies, where base-mobilization strategies are dominant, early skepticism among ideologues about heavy-handed governmental intervention can morph into skepticism about ostensibly non-ideological mitigation tools like masks, vaccinations, and treatments. If this happens, we can anticipate a correlation between partisanship and death rates. We turn now to a preliminary assessment of these expectations.

4 Preliminary Evidence

4.1 Cross-Country Patterns in Polarization and Covid Deaths

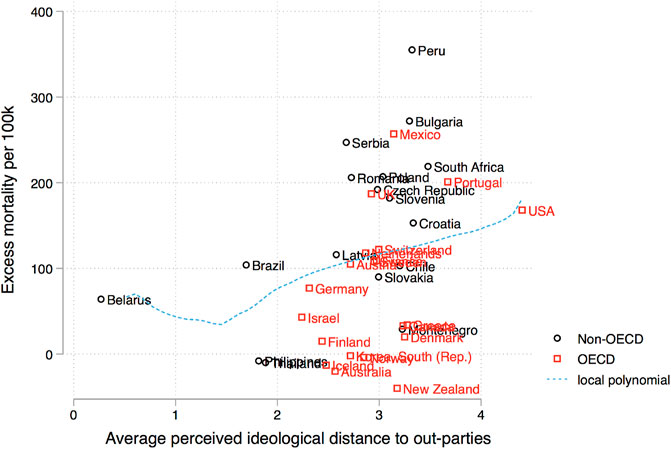

Let us first probe the plausibility of the claim that COVID death rates are higher in countries where the average voter views the out-party (or parties) as ideologically distasteful. Our framework maps nicely onto observable indicators of (xj − xi) and (xj − xc) in democracies. A common survey item asks respondents to place themselves and the parties on a common one-dimensional ideological scale. For each respondent, we can measure the perceived ideological distance between themselves and each party. In the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES), respondents are asked to place themselves, as well as each of the parties, on a numerical ideological scale. For each respondent, we leave aside the party that is perceived as most ideologically proximate, and we focus on the non-proximate parties. We calculate the perceived absolute distance to each of the non-proximate parties. We then calculate, for each respondent, the weighted average distance to the non-proximate parties, where the weights are the parties’ vote shares. In a two-party system like the United States, this is simply the perceived ideological distance to the out-party. That is to say, for people who see themselves as closer to the Democrats, we calculate the perceived absolute distance to the Republicans, and vice-versa for those who see themselves as closer to the Democrats. In a multi-party system like Germany, for someone who feels closest to the Christian Democrats, we calculate the absolute distance to each of the other parties, and take a weighted average, where the weights are the vote shares in the most recent election. We then calculate a country-wide average of this quantity. We plot this country-wide average on the horizontal axis, and a measure of excess mortality from the beginning of the pandemic until September of 2021, as assembled by The Economist, on the vertical axis. This plot is limited to countries covered by both the two most recent waves of the CSES and the excess mortality data.

Given the diverse unmeasured cross-country correlates of excess mortality, this type of analysis is provisional at best, but excess mortality has indeed been somewhat higher in countries where voters view the out-party or parties as most ideological distant. For instance, by this measure, the United States and Portugal are the most ideologically polarized countries covered by the CSES, and among OECD countries, they have experienced some of the worst public health outcomes during the pandemic, along with Mexico and the UK—two other highly polarized democracies. There is also a cluster of relatively less polarized democracies that have experienced substantially lower levels of excess mortality, including Australia, South Korea, and a number of multi-party democracies in Northern Europe.

The correlation is far from perfect, and should be approached with considerable skepticism, but it is at least consistent with the notion that when voters view the out-parties as extremely distasteful, politicians face weaker incentives to pursue death-minimizing policies.

In the discussion above, we have also suggested a subtly different way in which polarization might matter. In a polarized democracy, mitigation measures might be politicized such that voters for the government and the opposition cannot agree that deaths are, in fact, a useful performance measure. Even if death rates climb, in a polarized democracy, supporters of the government party or coalition might reject the notion that deaths can be blamed on the incumbent, or might be more likely to interpret calls for mask-wearing, social distancing, and shutdowns as unwarranted attacks by the out-party on their rights.

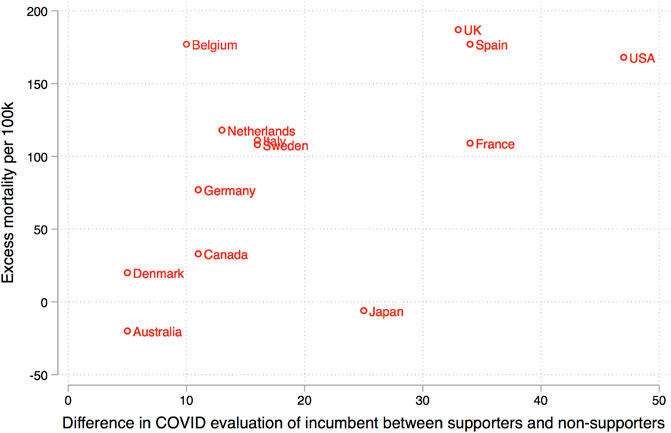

In a recent survey, the Pew Research Center asked respondents in 14 countries about the performance of their government in managing the COVID crisis. Not surprisingly, supporters of the governing party or coalition were more likely to report that the government was doing a “good job in managing the outbreak” than those who supported an opposition party. However, the size of this gap varied a good deal across countries. On the horizontal axis in Figure 2, we plot the difference in positive assessments of the government’s COVID response between supporters of the government and opposition. On the vertical axis, once again, we plot the excess mortality rate.

Figure 2 demonstrates that mortality was elevated in several of the countries with the most pronounced partisan polarization in perceptions of the government’s performance during the pandemic—such as the United States, Spain, and the UK. In contrast, mortality has been lower in countries like Australia, Denmark, and Canada, where supporters of the government and opposition largely agreed on the government’s response.

This correlation is difficult to interpret, however. It is plausible that the horizontal axis captures a relevant underlying aspect of polarization, and public health outcomes are better in countries where voters are capable of dispassionately assessing the competence of the government, regardless of ideology. It is just as plausible, however, that high death rates are exogenous—driven by factors like weather or the nature of exposure to the virus—and they cause voters to polarize along party lines in their perceptions of government performance. In other words, perhaps it is easier to agree about the government’s performance when the relevant indicator is clearly positive, as in Australia.

These caveats aside, the relationship between polarization, partisan biased evaluations, and excess deaths is likely part of the explanation why incumbents presiding over relatively high incidence of casualties seem to pay little attention to political costs. Exploiting a sample of 153 European regions, Charron, Lapuente and Rodriguez-Pose (2020) document a strong link between differences in trust between pro and anti-government supporters and the adoption of pro-healthy behavior. In addition, they also provide evidence of a link, in line with the intuitions developed in this essay, that mass political polarization undermines the political feasibility of unpopular yet necessary interventions, thus leading to higher levels of excess mortality. Their paper points to an interesting distinction between elite and mass polarization. While the latter seems to matter consistently, the role of the former appears less robust. An important question, however, concerns the hierarchy between the behavior of elites, mass attitudes and behavior, and the feasibility of political coalitions in which at least one of the partners must accept or propose policies that are foreign to their ideological rhetoric.

Differences across institutional contexts are likely important. For instance, incumbents facing re-election are less likely to implement policies perceived to have negative economic implications (Pulejo and Querubín, 2021). The dynamics of COVID response are surely different in multi-party systems than in systems with two dominant parties. And as mentioned above, federalism and political geography can provide institutional means for policy obstruction, blame-shifting, and tailoring of platforms for local audiences, with significant implications for people’s behavior (Testa et al., 2021).

4.2 The United States: Cross-County Variation in COVID Deaths

As can be seen in the figures above, the United States is, by several measures, the most polarized among the advanced industrial democracies. Many Americans view the out-party with extreme distaste. These hostile attitudes are not randomly distributed in geographic space. Urban Americans are overwhelmingly Democratic, and on average, view the Republican Party as extremely ideologically distant. On average, rural Americans view the Democratic party as extremely ideologically distant, while suburban areas often contain more ideological moderates.

Figures 1, 2 also demonstrate that the United States has experienced relatively high excess mortality. In a less polarized democracy with a large number of competence-oriented voters, we might expect to see clear evidence of electoral punishment, especially in the areas that registered the highest death rates. We have merged county-level data on COVID deaths4, population and several additional demographic variables5, and presidential election results from 2016 to 2020. As can be seen in Figure 3, there is a small positive relationship between cumulative COVID deaths per 100,000 people as of November 3, 2020 and the change in Donald Trump’s share of the two-party vote from 2016 to 2020. That is to say, Donald Trump’s support held steady, and in many cases he gained support, in the counties with the highest death rates.6 Many of these counties were in rural areas that were already part of the base of the Republican Party in 2016. Trump’s largest losses were in educated suburban areas that are typically relatively competitive but lean Republican—areas that experienced some of the lowest COVID death rates. Quite plausibly, these are the counties with the largest densities of competence-based voters.

FIGURE 1. The horizontal axis is the weighted average of the ideological distance reported by each CSES (Module 4 for most countries, Module 3 for some) respondent to all parties other than the most proximate party, where the weights are party vote shares in the most recent election. The vertical axis is excess mortality per 100 k as reported by The Economist.

FIGURE 2. The horizontal axis is the difference in the share of positive assessments of the government’s COVID response between supporters of the government and supporters of the opposition in a cross-national survey by the Pew Research Center. The vertical axis is excess mortality per 100 k as reported by The Economist.

FIGURE 3. The horizontal axis is the log of the cumulative death rate on Election Day in 2020. The vertical axis is the change in Donald Trump’s share of the two-party vote from 2016 to 2020. A positive number indicates an increase in vote share. The size of the data marker corresponds to the population of the county.

The simple bivariate plot in Figure 3 cannot be taken as definitive evidence against COVID-based retrospective voting. In fact, using similar data, (Baccini et al., 2020) present models with many control variables, including economic outcomes and COVID mitigation behaviors, along with an instrumental variables strategy involving meat-processing facilities. In their analysis, the positive coefficient that can be seen in the bivariate plot evidently flips, which they interpret as evidence of retrospective voting based on local death rates. Moreover, on the eve of the 2020 election, research by Warshaw, Vavreck and Baxter-King (2020) indicated that survey respondents in states and counties where death rates had recently increased reported lower approval of President Trump and greater likelihood of voting for Biden.

Our view is that the role of COVID in shaping the 2020 U.S. general election is still quite poorly understood. Our key intuition is that retrospective voting based on COVID deaths is more likely to take place among individuals who are relatively ideologically indifferent between the two parties. To the extent that these individuals disproportionately reside in suburban areas where death rates are low, and there are fewer such individuals in the rural areas where death rates have been highest, we do not anticipate a simple correlation between local death rates and loss of support for the incumbent, and we do not see one. However, more empirical research along these lines is needed.

It is clear that COVID mitigation policies in the United States were politicized along the lines sketched out above. As the virus emerged initially in large, overwhelmingly Democratic cities, Republican officials were hostile to a wide range of COVID mitigation policies that were viewed largely as cynical power-grabs by Democratic officials. Studies like (Corder et al., 2020) show that COVID mitigation policies at the state level followed a partisan logic. With some notable exceptions, states controlled by Republican governors and legislatures were slower to adopt a variety of COVID mitigation strategies, and quicker to drop them once implemented. Some Republican governors attempted to prevent Democratic county and city officials from implementing their own restrictions and mask policies. In states controlled by Democratic governors, many Republican county-level officials worked to undermine or ignore state-level policies.

Partisan differences across geographic space can be discerned not only in the policies adopted and implemented by officials, but in the behavior of citizens. A number of studies have demonstrated that mask-wearing, social distancing, and stay-at-home orders were taken less seriously in Republican-dominated areas (Grossman et al., 2020). Some studies indicate that cross-sectional differences in behavior have less to do with government mandates, and more to do with voluntary choices of individuals (Berry et al., 2021). If a significant portion of partisan differences in behavior is driven by choices of individuals rather than government policies, this only drives home the depth of ideological polarization in the United States. It appears that even measures like mask-wearing, social distancing, and ultimately vaccination have come to be viewed by some Americans as ideological statements.

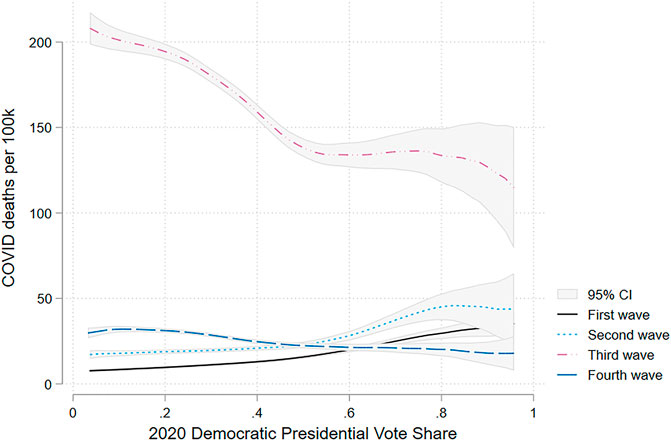

If some of these behaviors are indeed effective at preventing the spread of the virus, and large partisan differences in these behaviors emerged over the course of the pandemic, one might anticipate a growing correlation between county-level partisanship and death rates. Figure 4 uses a local polynomial to plot the 2020 county-level Democratic presidential vote share on the horizontal axis, and COVID deaths per 100,000 people on the vertical axis. It examines each wave separately, considering the first wave to have ended at the end of May 2020, and the second wave to have ended on August 31, 2020. The lengthy and deadly third wave was from September 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021. Finally, we consider separately the most recent spike in cases, from July 1, 2021 to December 20, 2021.

FIGURE 4. The horizontal axis is the Democratic presidential vote share, averaged between 2016 and 2020. The vertical axis is the COVID death rate per 100 k. The first wave is from the beginning of the pandemic until May 31, 2020. The second wave is from June 1, 2020 to August 31, 2020. The third wave is from September 1, 2020 until June 30, 2021. The fourth wave is from July 1, 2021 to the time of writing (October 23, 2021).

From the initial outbreak in early 2020 to the temporary lull in COVID cases in September 2020—the period covered by the first two waves—the virus was largely concentrated in the Democratic, urban areas where the virus initially began to spread after early contacts from international travelers. Note that the local polynomial plots for the first two waves are relatively flat until around 0.5, and then begin to increase quickly as the Democratic vote share grows. In the first wave, an increase of 10 percentage points in the Democratic vote share was associated with an increase of roughly 5 deaths per 100,000 people. In the second wave, the graph flattened a bit as the virus started to spread to some rural areas, but the vast majority of deaths were still occurring in very Democratic counties. It was during these initial waves that COVID mitigation strategies came to be thoroughly politicized.

But after opposition to COVID mitigation strategies had been adopted as a base-mobilization strategy for a good number of Republican candidates and officials, in the deadly third wave, the geography of the virus completely changed. As public health experts had predicted, the virus spread to rural, Republican areas—places with older, less healthy populations and poor public health infrastructure. Death rates in many rural areas have been quite high, in many cases far surpassing New York City’s experience in the first wave. The local polynomial plot for the third wave is relatively flat—albeit with relatively high death rates—throughout the range of Democratic districts, and deaths per 100,000 increase dramatically as the Republican vote share increases. During this period, a ten percentage-point increase in the Republican vote share was associated with an additional 16 deaths per 100,000. Even during the 6-month period covered by the fourth wave in Figure 4, there is a statistically significant relationship between the Republican vote share and the death rate. Cumulative deaths per 100,000 as of December 2021 are dominated by the third wave, such that overall, a 10 percentage-point increase in the county-level Republican vote share is associated with around 10 additional deaths per capita.

Given the very poor health of rural Americans, the lack of health infrastructure, and the different virus strains emerging at different times and places, Figure 4 by no means indicates a causal role for relatively lax enforcement and mitigation behavior rooted in ideology. We leave this vexing causal inference problem for future work, but it is clearly the case that the geographic incidence of the virus has shifted from urban, Democratic areas to rural, Republican areas, ultimately producing higher death rates in the latter. Overall, the lowest death rates were experienced in politically competitive suburban counties. Relatively high death rates are witnessed in rural, Republican areas of states not only with COVID-skeptic leadership, like South Dakota and Texas, but also in states with Democratic governors and more restrictive statewide policies, like Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, and Illinois. This is consistent with the claim that some types of statewide mandates are of limited value, given wide local leeway in enforcement and compliance. It is also consistent with the claim that high rural death rates during the third and fourth waves of COVID in the United States were driven in large part by structural factors like lack of immunity from prior infection, obesity, and poor hospitals rather than politics. Nevertheless, the combination of strong ideological attachment, low vaccination rates, opposition to mitigation behavior, and high death rates in rural America is difficult to ignore.

Future research might examine whether correlations between partisanship, population density, and death rates are also present in less polarized democracies where vaccines, masks, and social distancing have been less politicized. We anticipate that the correlation between partisanship and death rates seen in the United States is relatively rare—a product of its unusual level of political polarization.

5 Concluding Remarks

This essay has taken a first look at the relationship between political polarization, democratic accountability, and the success of governments in combating COVID-19. Our analysis was motivated by the political resilience of incumbents in areas hit particularly hard by the pandemic. Our central argument points to a partisan asymmetry in the nature of COVID policy responses. Both regulatory restrictions and fiscal expansions provide a more natural terrain for left parties, who are accustomed to mobilizing their base with a related set of policies. The right, in contrast, had to argue against its base when endorsing policies that became a pressing need during the hardest times of the pandemic. In polarized societies, the expected political costs of moves toward compromise prevent cooperation, and facilitate a direct mapping of COVID mitigation policies onto preexisting ideological conflicts, which can expand even to ostensibly non-ideological areas like vaccines and masks. Politicians in polarized societies have grown accustomed to strategies of base mobilization, and have few reasons to worry about proving their competence via indicators like low death rates. Rather than presenting an opportunity to demonstrate competence, in a polarized society, a pandemic like COVID can create new opportunities for the parties to push their preexisting ideological agendas and exploit new ways to demonize the out-party.

We have provided very preliminary cross-national evidence that death rates have been higher in more polarized countries, but considerable refinement is needed for this type of analysis to be credible. We have also demonstrated that COVID has gone from a disease disproportionately affecting Democratic urban areas to one disproportionately affecting Republican rural areas in the United States. This is consistent with our account of the dynamics of polarization, but again, far more refined analysis is needed.

Rather than providing answers, this essay is meant to provide a framework to provoke further theoretical and empirical inquiry. It points to several lines of work to further explore the connection between accountability and polarization. One approach might be to examine pre-pandemic disagreements between supporters of the government and opposition about economic performance in a series of countries. Perhaps in polarized societies, supporters of different parties were unable to agree about performance metrics prior to the pandemic, and it is possible to find other types of evidence that competence-based voting is squeezed out in polarized societies. Moreover, we anticipate that competence-based retrospective voting is more common in less polarized democracies, and that as a result, incumbents face stronger incentives to produce favorable performance indicators.

We have also hypothesized that the politicization of COVID mitigation policies, and the emergence of a correlation between partisanship and death rates, is a function of pre-existing polarization.

Another interesting possibility is the claim that ideological moderates, or more precisely, individuals whose distaste for the out-party is relatively low, are more likely than ideologues to engage in performance-based retrospective voting. If such individuals are clustered in space, aggregate evidence of retrospective, performance-based voting will perhaps only be discernible in specific areas.

Finally, one additional avenue worthy of exploration points to the institutional organization of democracies: voters in multi-party democracies may be less likely to view the main out-parties as extremely distant than are voters in strict two-party systems. In turn, this might reduce incentives for politicization of COVID response and associated demonization of out-parties, ultimately providing incumbents in multi-party democracies with stronger incentives to perform well.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1We merge county-level election data from the MIT Election Lab with COVID death rates compiled by the New York Times, and rank the counties by cumulative COVID death rates on Election Day, and calculate the population-weighted average change in two-party vote shares among counties ranked in the top 100 and 500

2Note that this type of anti-government rhetoric has been less pronounced among Christian Democrats in the European continental tradition

3Quote by Jen Psaki, White House Press Secretary, March 8, 2021 Press Briefing

4https://github.com/nytimes/covid-19-data

5source: American Community Survey

6There is also a modest positive bivariate correlation between the increase in deaths per capita from May 20—the beginning of the second wave—to November 3. The same is true if other dates are selected

References

Acharya, A., Blackwell, M., and Sen, M. (2018). Explaining Preferences from Behavior: A Cognitive Dissonance Approach. J. Polit. 80 (2), 400–411. doi:10.1086/694541

Achen, C., Bartels, L., Achen, C. H., and Bartels, L. M. (2017). Democracy for Realists. Princeton University Press.

Baccini, L., Abel, B., and Weymouth, S. (2020). The COVID-19 Pandemic and the 2020 US Presidential Election. J. Popul. Econ. (34), 739–767.

Berry, C. R., Fowler, A., Glazer, T., Handel-Meyer, S., and MacMillen, A. (2021). Evaluating the Effects of Shelter-In-Place Policies during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 118 (15). doi:10.1073/pnas.2019706118

Bosancianu, C., Kim, Y., Hilbig, H., Humphreys, M., Sampada, K. C., Lieber, N., et al. (2020). Political and Social Correlates of Covid-19 Mortality.”

Charron, N., Lapuente, V., and Rodriguez-Pose, A. (2020). Uncooperative Society, Uncooperative Politics or Both? How Trust, Polarization and Populism Explain Excess Mortality for COVID-19 across European Regions. QOG Working Pap.

Cheibub, J. A., Ji Yeon, J. H., and Adam, P. 2020. Rights and Deaths: Government Reactions to the Pandemic. Available at SSRN 3645410.

Corder, J. K., Mingus, M. S., and Blinova, D. (2020). Factors Motivating the Timing of COVID-19 Shelter in Place Orders by U.S. Governors. Pol. Des. Pract. 3 (3), 334–349. doi:10.1080/25741292.2020.1825156

Cox, G. W., and Rodden, J. A. (2021). “Demonization,” in Research Group on Political Institutions and Economic Policy (PIEP) (Harvard University).

Duch, R. M., and Stevenson, R. T. (2008). The Economic Vote: How Political and Economic Institutions Condition Election Results. Cambridge University Press.

Ferejohn, J. (1986). Incumbent Performance and Electoral Control. Public choice 50 (1), 5–25. doi:10.1007/bf00124924

Frey, C. B., Chen, C., and Presidente, G. (2020). Democracy, Culture, and Contagion: Political Regimes and Countries Responsiveness to Covid-19. Covid Econ. 18.

Grossman, G., Kim, S., Rexer, J. M., and Thirumurthy, H. (2020). Political Partisanship Influences Behavioral Responses to Governors' Recommendations for COVID-19 Prevention in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 117 (39), 24144–24153. doi:10.1073/pnas.2007835117

Lavine, H. G., Johnston, C. D., and Steenbergen, M. R. (2012). The Ambivalent Partisan: How Critical Loyalty Promotes Democracy. Oxford University Press.

Pulejo, M., and Querubín, P. (2021). Electoral Concerns Reduce Restrictive Measures during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Public Econ. 198, 104387. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104387

Testa, P. F., Snyder, R., Rios, E., Moncada, E., Giraudy, A., and Bennouna, C. (2021). Who Stays at Home? the Politics of Social Distancing in Brazil, Mexico, and the United States during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Forthcoming: Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law.

Keywords: polarization, pandemics, policy responses, elections, accountability, democracy, crises

Citation: Beramendi P and Rodden J (2022) Polarization and Accountability in Covid Times. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:728341. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.728341

Received: 21 June 2021; Accepted: 03 November 2021;

Published: 19 January 2022.

Edited by:

Anwen Elias, Aberystwyth University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Markus Wagner, University of Vienna, AustriaDespina Alexiadou, University of Strathclyde, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Beramendi and Rodden. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pablo Beramendi, cGI0NUBkdWtlLmVkdQ==

Pablo Beramendi

Pablo Beramendi Jonathan Rodden2

Jonathan Rodden2