- Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict, Faculty of Social Science, Ruhr University Bochum, Bochum, Germany

In humanitarian action, localization can be characterized by high hopes, many disillusions, and only limited progress. This is partly because traditional humanitarian action focuses mostly on short-term action and is supply-oriented, with decisions on the set-up and evaluation of aid activities being made by outside donors and organizations, instead of by the beneficiaries/target groups themselves. After a theoretical overview of localization and its problems, this article describes how two South Sudanese NGOs, Mary Help Association and Bishop Gassis Relief and Rescue Foundation (BGRRF), and a Ugandan NGO, Caritas Gulu, work on food security. It describes how they are implementing a 3-year program with support from Caritas Germany. The article analyzes the importance of their long-term interaction to foster trust over time through capacity development. Such capacity development includes capacity building (e.g., training, joint workshops, regular evaluations, and audits) and capacity sharing in the form of South-South cooperation. This analysis also shows that localization can be strengthened when the involved organizations agree on goals, and establish a process to reinforce their cooperation by strengthening the activities on the ground to achieve those goals. It also indicates the role of religion within capacity-development, as well as the structural problems in the context of localization that cannot easily be overcome. A conceptual model summarizes the analysis and explains the degree to which localization can be successful. Finally, the conclusions summarize the main arguments and indicate issues for further research.

Introduction

In its Grand Bargain, the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit (WHS) emphasized—with great fanfare—longer-term funding, localization, and linking humanitarian action with development cooperation. Humanitarian actors, however, have attempted to promote localization long before the WHS. They have widely acknowledged that local actors are the first ones on the scene when disaster strikes, that many important initiatives come from the local population (be they family members, friends, informal neighborhood groups, local administrations, local associations, or local NGOs), and that most local actors stay when international organizations leave. Virtually all actors working in humanitarian crises recognize the need to contextualize their work (Autesserre, 2014). Similarly, Roepstorff (2020, p. 290) has pointed out that better inclusion of local actors promises better “sustainability, cost-effectiveness, cultural sensitivity–and ultimately a ‘swifter exit for international actors’.”

Despite this knowledge and growing attention to localization, the 2020 Global Humanitarian Assistance Report found that the share of direct humanitarian funding to local and national actors was reduced from an already extremely meager 3.5% in 2018 to 2.1% in 2019 (Development Initiatives, 2021, p. 48).1 How can the acknowledgement of the importance of localization be reconciled with this extremely low level of funding?

This article suggests that this paradox of general but shallow support is both an effect of the way in which humanitarian action traditionally has been institutionalized, and a consequence of the fact that localization has been difficult to define and cannot address structural North-South factors that hamper humanitarian effectiveness. In addition, local actors and their relationships with international actors can be highly diverse. Somewhat surprisingly, despite the growing attention to localization, the number of in-depth empirical studies on the actual dynamics of localization processes remains limited.

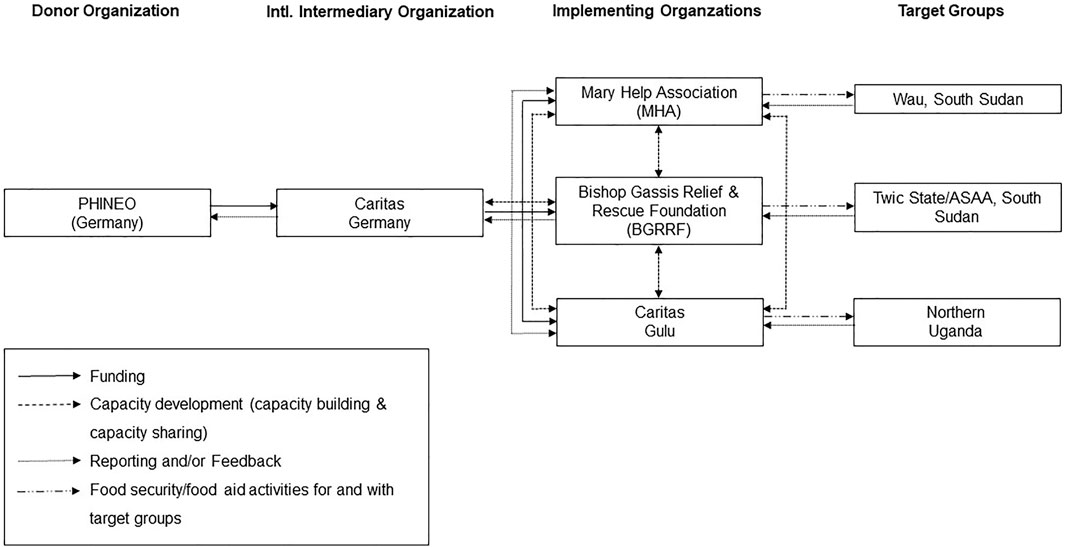

To see what is possible in the realm of localization, this article uses a relational aid-chain approach to study the practices of food security work of three NGOs from respectively South Sudan and Northern Uganda that cooperate in close partnership with Caritas Germany (2018–2021). This project is funded by Phineo, a German funding organization. The main research questions are: How and to what extent do these organizations make localization work? And what can we learn conceptually from their work?

This article consists of five parts that describe and analyze ways in which localization and capacities have been strengthened. First, it provides a short conceptual background of localization and humanitarian action. Second, it discusses the relational concept of the aid chain. Next, it briefly describes the armed conflict in South Sudan. Then it discusses the methodological aspects of this research. The fifth part empirically describes the three organizations and their activities in the area of food security, which is followed by an analysis of localization. This analysis provides the building blocks of a conceptual model of localization. The article ends with the main conclusions concerning the possibilities of localization, as well as recommendations for more research on humanitarian localization.

Concepts: Localization and Humanitarian Action

The debate on localization is much older than the 2016 WHS and its Grand Bargain. In 1994, for example, principle 6 of the Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and Non-Governmental Organizations in Disaster Relief already stated that “We shall attempt to build disaster response on local capacities” (International Committee of the Red Cross, 1994). Similar precepts can be found in the Good Humanitarian Donorship Initiative and the 2013 Core Humanitarian Standard.

Nevertheless, the haphazard and incomplete implementation of this Code and other related sets of principles and standards, has been noted time and again in international evaluations of humanitarian responses from Rwanda to Kosovo and Haiti. A crucial impetus to the debate on localization came from the system-wide Tsunami Evaluation Coalition’s (TEC) report of 2007. It “found that international agencies had major problems scaling up their own responses […] Pre-existing links, and mutual respect, between international agencies and local partners also led to better use of both international and local capacities.” In this vein, the TEC argued that the humanitarian response “was most effective when enabling, facilitating, and supporting local actors” (Cosgrave, 2007, p. 7). The TEC suggested that the international humanitarian community “needs to cede ownership of the response to the affected population and become accountable to them” (Cosgrave, 2007, p. 7). Yet, it also noted that international actors “often brushed local capacities aside” (Cosgrave, 2007, p. 7).

The subsequent scholarly literature on local actors can be categorized into three groups. First, there is a limited set of studies on the actual implementation of localization. Most studies document the (lack of) capacities, coordination, participation and quality/accountability of different actors (Cordaid et al., 2016; Muth and Otto, 2020). This set of studies builds on earlier literature on capacity development (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2018), partnerships (e.g., van der Haar and Hilhorst, 2009; Hilhorst and Jansen, 2010; Gibbons et al., 2018), and accountability (DeMars and Dijkzeul, 2015).

Next, comes a notable group of authors that makes recommendations on reforming the whole humanitarian system. They suggest that for international actors, it is “time to let go” (Bennett et al., 2016) and to flip “the humanitarian system on its head” (Gingerich and Cohen, 2015) in order to provide more room for local actors. Many of these reform studies contain strong self-criticism by humanitarian organizations and officials. They also notice that opportunities to enhance partnerships are missed repeatedly (Ramalingam et al., 2013; Featherstone and Antequisa, 2014).

Finally, a rather small, but crucial category concentrates on funding. It notes the limited amount of funding that goes to local partners (Ali et al., 2018; Willits-King et al., 2018). The main argument of all three groups is that localization is essential, but often fails to materialize.

Methodologically, almost all of the studies above are based on literature reviews, interviews and focus group discussions during one short research stay. A sizable number also use seminars of humanitarian organizations to gather and analyze data. As a result, they provide a useful cross-sectional overview of issues relevant to localization at one moment in time, but fail to understand the dynamics of localization or partnerships over time. Conceptually, as Roepstorff indicates, these studies also fail to clarify “who exactly these local actors are [and] that the way the local is constructed in the current discourse is based on a problematic dichotomy between the local and the international that leads to blind spots in the analysis of exclusionary humanitarian practices” (Roepstorff, 2020, p. 290).

In response to this methodological and conceptual criticism, this article offers a more longitudinal study of the processes of the actual constitution and dynamics of both “international” and “local” actors during localization. In order to do so, this article employs the aid chain model, which offers a relational perspective on the actors engaged in humanitarian action.

Understanding the Aid Chains

Interestingly, after independence most states in the Global South had functioning administrative structures in place to prevent and address humanitarian crises. Juma and Suhrke (2002) describe how international humanitarian organizations often bypassed such state structures to execute their own projects, which contributed to the long-term decline of these structures; a kind of reverse localization. As a result, there are now at least four modalities for providing aid, or put differently, four different types of aid chains: 1) international organizations’ self-implementation, as Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) does; 2) direct funding to government institutions; 3) direct funding from donor government to local NGOs; and 4) funding through international organizations that execute through local partners. A few scholars have pinpointed five factors in the relationships among actors in the aid chains over time that make it difficult to localize humanitarian action.2

First, needs in crises can be so life-threatening that the urge to save lives immediately drives out longer-term capacity building, strengthening partnerships, and other, more developmental tasks. In principle, development cooperation should take over capacity building, in particular when humanitarian action is being phased out. But even longer-term development funding, e.g., three to 5 years, can rarely overcome structural barriers, such as North-South inequity, corruption, poverty, and bad governance, that hinder strengthening local capacities.

Second, the nature of humanitarian funding also hampers localization. Most funding is for projects that last only half a year or a year, which is only a brief period for developing capacities and partnerships (Dijkzeul, 2005; DeMars and Dijkzeul, 2015). Crucially, donors, especially donor governments, pay for humanitarian action and people in need are “just” recipients. As people in need do not pay for their assistance, they miss the feedback loop that consumers have: stop buying and the providers will cease making a profit and ultimately will go bankrupt. Consequently, people in need are in a weak position to demand improvements in the goods and services they receive.

Third, many differences exist between international humanitarian and locally-based organizations. For instance, Vaux (2017) describes the differences between international humanitarian organizations and a local NGO, the Self-Employed Women’s Association in Gujarat, India. The latter is a member organization, the demands of its members drive its actions. Its members often stress volunteerism and local leadership, and want to retain its independence, whereas international organizations are more supply driven. Their mandates, policies and guidelines shape their actions. In addition, they are under pressure to follow donor government policies and funding requirements, if they want to obtain and maintain funding. Usually, donor policies set the tone for the organizations in the aid chain(s). An oligopoly of the main donor governments, UN organizations, and the large international humanitarian NGOs determines the principles and standards of humanitarian action. Consequently, the humanitarian system tends to be more responsive toward donors than to local actors. Unsurprisingly, the stamina and long-term engagement of international organizations is often much weaker than that of local organizations.

Fourth, when international humanitarian organizations work with local organizations, the latter often become subcontractors. The emphasis on service delivery then crowds out longer-term capacity development (Dijkzeul, 2005). Smillie and Evenson (2003) describe how the funding relationships in subcontracting rarely build capacities or allow for overhead funding that these organizations need to grow and prosper. Instead, they suffer from high donor demands, for example with reporting and evaluation requirements, as well as irregular funding.

Fifth, donors and international organizations are afraid that local NGOs lack knowledge of humanitarian principles and standards (Donini, 2010). They often assume that local NGOs lack the capacities and quality to successfully execute humanitarian projects.3 And they sometimes fail to notice the local capacities that do exist.

All in all, the traditional humanitarian system is not geared toward localization. “Local” organizations are often put into a weaker position. Nevertheless, as Carpenter and Kent remark, “the old cooperation paradigm, in which non-traditional humanitarian actors simply fit into the tried and tested approaches of traditional humanitarian actors, is not the only way the global humanitarian system may develop” (Carpenter and Kent, 2017, p. 144). Moreover, the above factors are broad trends that influence the four types of aid chains differently. This article focuses on funding from international humanitarian organizations to “local” partners. This partnership approach is relatively strong among German humanitarian NGOs, as well as among faith-based organizations. They maintain relationships that often go back decades. Particularly, this article discusses the extent to which the aid chain from Phineo, a German donor, to Caritas Germany, a German Roman Catholic NGO, and then to two South Sudanese organizations, the Mary Help Association (MHA) and the Bishop Gassis Relief and Rescue Foundation (BGRRF), and one Ugandan NGO, Caritas Gulu, strengthens localization.4 To this end, it describes the practices of these organizations in the Phineo food security program.

Brief Background of South Sudan

In July 2011, South Sudan became independent from Sudan after a long struggle. In December 2013, a vicious armed conflict broke out (again), which caused severe human suffering. South Sudan’s economy has been devastated and food insecurity has worsened considerably. Since 2013, thousands of lives have been lost due to direct violence and many more through the breakdown of social services (e.g., health and education), agriculture, transport, and markets. In 2014, the UN Security Council modified the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) by giving it a protection mandate, including assisting displaced persons. Out of a population of more than 11.7 million people, approximately 1.6 million have become internally displaced persons (IDPs) and 2.2 million have become refugees in neighboring countries. Notably, 880,000 South Sudanese refugees now live in northern Uganda (UNHCR, 2020b).

In 2018, peace negotiations took place and the security situation stabilized somewhat in some parts of the country, while further deteriorating in others. In 2020, out of 7.5 million people in need, about 6.5 million were “acutely food insecure”. The latter number includes 1.3 million malnourished children. Since March 2020, COVID-19 has further aggravated this dire situation. Food insecurity and malnutrition have increased as a result of closed borders, reduced transport of food commodities, higher unemployment, and rising food prices (UNHCR, 2019, pp. 4-6; OCHA, 2019, pp. 4, 8, 110; UNHCR, 2020a, pp. 6-8; UNHCR, 2020b).

Methodology

The relational perspective of the aid chain determines the qualitative, interpretative methodology of this exploratory research. The Phineo food security program was selected, because it allowed a more longitudinal comparison of the three organizations from South Sudan and Uganda, and of Caritas Germany as their international partner over the course of almost 3 years.

In terms of positionality, I had already worked with Caritas Germany since 2013. In 2017, I carried out a mid-term review of a humanitarian project for refugees in northern Uganda for Caritas Gulu. A year later, I worked in Juba with an Indian organization, DMI, funded by Caritas Germany. However, it should be noted that DMI is not part of the Phineo program. I also supported Caritas Gulu with the development of its humanitarian strategy.

In april 2019, I became the independent evaluator of the food security program and carried out field research for more than 4 weeks with these three organizations. I used the IFRC Food Security Assessment Guide (2015) to select the data collection methods for this evaluation, and combined it with the Sphere Guidelines (2018) to formulate a semi-structured questionnaire on food security. In South Sudan and northern Uganda, I carried out community focus group discussions (FGDs), usually with separate male and female groups, individual key informant interviews (KIIs) with local leaders, village observation tours of the project sites, and household interviews (HHIs). In the subsequent data analysis, I triangulated data from these data collection methods with a focus on explaining the degree of achievement of the projects’ objectives, lessons learned, remaining problems, and formulating recommendations.

Next, I also actively participated in organizing and presenting a joint workshop in Wau, South Sudan, in September 2019 with all partners (except Phineo). On the basis of my 2019 evaluation, I indicated in which areas of activity the participating organizations could learn from each other.

In 2020, the evaluation became remote due to COVID-19, although we were in touch regularly by email, Zoom, WhatsApp, and Skype. The main data collection methods were a desk review of secondary data, project documents, and expert interviews conducted by myself, as well as field visits by three local researchers to the actual project sites.5 During the field visits, my colleagues used the same semi-structured questionnaire and data collection methods as I had in the previous year. With the feedback of the organizations and the three colleagues, I then wrote the 2020 evaluation report, which followed the same outline as the 2019 evaluation report.

Over time, I have come to know these organizations well, and I regularly communicate with the staff members about their work, their management processes, and target groups. We also increasingly discuss the history and current challenges, including deforestation, of the project areas, as well as each other’s families.

The main research challenge has always been to understand the perspectives of all actors in the aid chain, especially including the people in need. Ethically, it is important to make their voices heard. Practically, leaving one or more actors out of the aid chain would mean that the research fails to fully elucidate the dynamics and impact of the aid activities and localization. At the time of writing, the final annual evaluation of the Phineo program was being planned. This article therefore discusses the preparations and the first two-and-a-half years of the program.

Empirical Description: Four Organizations, One Program

Food insecurity is a recurring problem in South Sudan. In the past, Caritas Germany and its partners have implemented various food aid and agricultural projects. In 2017, Caritas Germany learned about a funding possibility with Phineo and contacted its three partner organizations to work quickly on a 3-year food security program.

Briefly, “[a] person, household or community, region or nation is food secure when all members at all times have physical and economic access to buy, produce, obtain or consume sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for a healthy and active life” (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, 2015, p. 7).

The three partner organizations built on their earlier experiences to design their food security projects for their regions. They already knew the severe needs and problems in food security and agriculture well, and they needed to submit a proposal quickly. Hence, a formal base-line survey was neither possible nor necessary. The organizations tailored the projects to the local context, so that each of the three projects differed according to its target area, target groups, and set up. Crucially, the Phineo program also included funding for evaluations, training, audits, and workshops. As a result, this program also strongly contributed to capacity development. The capacity development included both capacity building, for example, through training, auditing, and workshops, and capacity sharing among the organizations in the form of South-South cooperation. After some back and forth to check the feasibility of the projects’ objectives, Caritas Germany submitted the program to Phineo (See Figure 1).

Phineo became a rather hands-off donor, but of course it determined the reporting requirements.6 In addition, Caritas Germany used the Phineo approach to evaluation in the 2019 Wau workshop course on monitoring and evaluation (M&E) (Kurz and Kubek, 2021). More generally, Caritas Germany played a central role in transmitting information, such as official reports, between Phineo and the tree organizations on the ground.

Mary Help Association—Wau, South Sudan

MHA is an NGO set up by an Indian-Salesian nun, who knew South Sudan well, together with a group of Catholics from Kerala, India, in 2000. It works closely with the Catholic Diocese of Wau. In 2007, it established the first Nursing and Midwifery School in South Sudan. In 2016, together with the governmental Western Bahr el Ghazal University, it started offering degree courses in Nursing and Midwifery. It also operates a hospital in Alel Chok, just outside of Wau.

The overall goal of the project “Agriculture Training and Nutrition Support for 9 Villages North of Wau, South Sudan, 2018–2021” is to contribute to the survival, food security, and health status improvements of the most vulnerable communities in the Greater Wau area. In each project year, it serves three different villages that lie in a predominantly Dinka area, but there are also some mainly Luo villages. The Dinka and Luo are “pastoralists by inclination, and agriculturalists by necessity.“7 Nowadays, they live increasingly as agriculturalists—some already for several generations. This cultural sea-change has proven very challenging for them.

The 2018–2019 project villages were located relatively close to the hospital, so they were easy to reach even though the project facilities (truck and office) were not fully operational yet. In March 2019, MHA began working in the next three villages; then in March 2020, in the final three villages (which are currently being evaluated).

The first objective of the MHA project is that “720 farmers in the 9 villages around the settlement of Alel Chok, north of Wau, successfully commence with sustainable agriculture and are able to feed themselves and their 450 most vulnerable individuals throughout the year.” Each year, this project aims to provide 240 families (approximately 1,680 individuals) and 150 vulnerable individuals (some with dependent children), equally spread over three villages. These provisions include four food aid items (13.5 kg of sorghum, 15 kg of beans, 0.9 kg of cooking oil, and 0.45 kg of salt) to bridge the hunger gap, which lasts from June to mid-August. This hunger gap is the most critical nutrition period of the year, and the local population calls it “the terrible months” before the first harvest takes place. At the end of this period, people often eat only one meal a day or less.

Whereas food aid for the 150 most vulnerable individuals, generally elderly or disabled persons, follows the humanitarian principles, food aid for the 240 families is intended to enable them to start their labor-intensive field work. It concentrates on those farmers that can become successful examples of farming for other villagers. In other words, the project also has a longer-term development goal.

A selection committee of local notables and an MHA representative identified the actual farmer families for each village. In the first 2 years, the number of selected farming families was increased from 240 to 260 families. They received the four basic food items and seeds for the cultivation of staple foods (sorghum, beans, groundnuts, maize, sesame, and millet), and selected two tools (from long and short spades, rakes, axes, hoes, and machetes) (see objective 2). After the harvest, the 260 farming families were supposed to support the most vulnerable individuals in their communities with food. In addition, the families were expected to produce and store seeds for the next planting season and to replace damaged tools.

In addition, 50 vulnerable persons and their dependents received food aid in each village.8 Overall, respondents were satisfied with this aid because it helped them bridge the hunger gap. Although the farming households now produce more food, which also lasts longer into the hunger gap (until the end of June/mid-July), and earn a little money (see below), they do not produce enough food to either sustain them fully through the hunger gap, or produce enough seeds for the next planting season. As a result, they cannot support the most vulnerable people sufficiently and they will need seeds for the next planting season.

The second objective stated “720 farming households have significantly improved and broadened their skills and agricultural techniques and have measurably increased their food consumption and the variety of consumed food.” In addition to seeds and tools, MHA also provides training in soil preparation and planting, tree planting and nursery, weed management, harvesting, and entrepreneurship—most of which took place at either the hospital compound or at the large demonstration garden in Nyanpath, one of the first three villages (see below). At the hospital compound, it has a staple food section (e.g., sorghum, maize, millet), a vegetable garden, and a fruit tree nursery. The demonstration gardens will start to play a bigger role, because they can provide food, seeds, and seedlings, as well as training grounds (e.g., for ox-plowing), while WFP is reducing some types of its food rations. These gardens have the potential to make MHA’s food security work more autonomous and less dependent on donors. MHA is also working more with drought resistant crops. In terms of food utilization, only okra and tomatoes are being sun-dried as food reserves for the next hunger gap.

Importantly, in 2018–2019, MHA trained 20 people from each village in ox-plowing, and in 2019–2020, 25 people from each of the new villages. Farmers were enthusiastic about the training and utilization of ox-plows, particularly because their new-found ability allows them to increase the acreage under agriculture, which helped to increase output. They also appreciated that they did not have to do all the plowing manually with a maloda9, as this is back-breaking work that also hurts their hands. About 20% of the families receiving training on ox-plowing were female-headed households. In two of the 2019–2020 villages, five participating households received one metal plow. As a consequence of the increased number of participating households in the third village, six families had to share one plow.

In the first three villages, which had already increased their cultivated land in the first project year, farmers continued to expand it further, from about 1.5-2 feddan to 5-6 feddan.10 In the second group of three villages, people shifted from 1 feddan to 3-4 feddan under cultivation. The rains in 2019 were so good that there was no drought, and only one village suffered from flooding. Importantly, increasing agricultural productivity with ox-plowing can off-set some of the negative effects of climate change and insecurity. However, currently, ox-plowing faces two main constraints: 1) most people do not own oxen and need to rent them, which is expensive; and 2) the number of metal plows that MHA can provide is limited, because they are expensive and need to be imported.

The distribution of seeds allowed the farmers to increase the amount and diversity of vegetables and staple crops they were growing. However, this increase was less than originally hoped for due to the dry spell and erratic rainfall. In other words, food access and availability improved, but not enough. Nevertheless, a comparison of randomized nutrition surveys that took place every half a year from May 2017 to October 2021, based on measuring the mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) of young children (5–59 months), shows that although global acute malnutrition (GAM) fluctuates seasonally, it has declined in the supported villages. In addition, the feeding center at the hospital was closed in 2019, due to the decline in malnutrition, and it has not been necessary to reopen it.

The third objective stated “The participating farmers generate surpluses and successfully market a part of their products.” The participating farmers have harvested and sold a small part of their produce on the market, either in their own village or in Wau. They usually can fetch a better price in Wau, where MHA has put the farmers in touch with customers (e.g., markets, hotels, and restaurants). Some farmers now have regular customers, so limited cash-production has become possible.

The farmers have positive opinions about the fact that they can sometimes sell their produce at the market. For example, rigila (a local type of lettuce) could be harvested quickly and regularly, and then sold for a good price. Some farmers indicated that it was difficult to determine the right price for their goods. The sold produce helped them pay for school fees, school uniforms and materials, as well as buy products on the market, for instance clothes, shoes, salt, sugar, soap, or meat.

In sum, food diversity and production have increased, malnutrition has decreased, and the farmers can occasionally buy more products on the market. Still, they were often unable to produce enough seeds for the next planting season or to produce enough food to fully bridge the whole hunger gap. Similarly, some families still cannot afford the school fees. Nor are the farming families able to adequately support the most vulnerable people in their communities throughout the year.

Objective 4 focused on MHA and its management: “MHA as an institution has improved institutional/physical structures to support future (intended or intensified) agricultural activities (e.g., in addressing more villages/villagers or introducing more advanced technologies, like irrigation).” MHA worked flexibly to achieve its objectives; for example, in 2018 it responded quickly to the initial delay in funding from March to May and quickly prepared training, so that training and planting could start on time. In both 2018 and 2019, it was able to help more people than planned with both ox-plowing and food aid. MHA also set up an office and storage spaces, bought a Land Cruiser and a small truck, and hired staff.

As part of the project, MHA and its activities were audited. Most recommendations focused on improving internal controls. The auditors provided on-the-job training and examples as well as a follow-up to their recommendations. This follow-up showed that MHA had implemented most of the recommendations; with only a few of them still being worked on. The annual audits became an important learning process for its administration and reporting.

Several staffing changes have also occurred. Some staff remarked that their remuneration was lower than that of other NGOs. However, MHA is mainly a South Sudanese organization with some international funding, which limits its financial space. Nevertheless, it can offer more “in-kind” incentives, such as training, as well as visits and on-the-job training/internships at the other two partner organizations from the Phineo program. COVID-19 travel restrictions and staff turnover, due to higher wages at international organizations, at times slowed project execution down.

All in all, MHA is quickly professionalizing its management. It is becoming better placed to extend its activities to other villages, promote ox-plowing, use demonstration gardens, and to include new agricultural techniques, such as irrigation.

Bishop Gassis Relief and Rescue Foundation—Agok, South Sudan

The Bishop Gassis Relief and Rescue Foundation was founded in 2016. It has grown out of the pastoral services and humanitarian and development programs implemented through the Diocese of El Obeid in both Sudan and South Sudan. Emeritus Bishop Macram Max Gassis established this foundation in order to continue the humanitarian work in the Diocese and respond to other needs. BGRRF has its Head Office in Nairobi, Kenya, because the Bishop had to flee, when the Bashir government threatened him (before South Sudan became independent). It has been responding to the conflict in the Nuba Mountains in South Kordofan, Sudan, with a large-scale emergency program. It also continues to run development, humanitarian and pastoral service activities in the Abyei Special Administrative Area (ASAA), and in Twic State in South Sudan.11 Its activities include health, education, women’s groups, a radio station, WASH, and food aid and security.

The overall goal of the Food Relief and Food Security Project for the Agok and Abyei Administrative Area and Turalei, Twic State (2018–2021) is that targeted households have improved access to essential food requirements at the household level through provision of food and agricultural inputs in both areas.

Its first objective states that “350 households from Agok/Abyei and Twic state (including returnees) have improved health and well-being through access to essential foods.” This objective essentially entails a relief operation for 2,450 (= 350 * 7)12 people. The local relief and rehabilitation commissions (RRC) selected the 350 beneficiary households for 2019–2020.13 These households received a basket of sorghum (50 kg), lentils (25 kg), cooking oil (7.5 ltrs), and 1 kg of salt in both July and August, which are the worst months for hunger. The relief operation needs to be repeated each year of the project, but as the economic status of the beneficiaries of the first year may change, the actual beneficiaries also change from year to year.14

In 2019, BGRRF sampled 50 beneficiaries for interviews. They all confirmed that they had received the items, which helped them to get through the hunger period and improved their health and nutritional status, as they had enough food and did not go hungry. Children were also able to stay in their schools (until these were closed due to COVID-19). The focus groups and household interviews also showed that many people struggle and only have one meal a day at the end of the hunger period. Hence, they needed and appreciated the food aid.

Several communities reported that the Misseriya Arabs and the Nuer stole their cows and goats during armed raids. Occasionally, people were murdered, for example when they went to fetch firewood. The raids thus severely threaten lives and livelihoods and worsen the already insecure food situation. Moreover, with COVID-19, people have started moving to Wau, Juba, and Khartoum, because they cannot make ends meet with rising food prices.15 In sum, relief was necessary due to the overall situation of poverty, insecurity, raids, thefts, and high food prices.

The second objective reads “100 households are provided with ox-plows to support increased capacity for food production in order to improve household level food security.” Despite cultural barriers to using oxen and their limited availability, BGRRF has been able to expand its ox-plowing from 20 households in Mayen Abun in 2018 to 20 in Mayen Abun and 20 in Turalei in 2019. Training in ox-plowing is crucial to overcoming cultural resistance. Half of the trained households are headed by women. People increasingly appreciate ox-plowing, because it saves time and effort, and brings higher yields. People are now sharing plows.16 One farmer argued “Working with an ox-plow is good and we want to try [it].” BGRRF staff also noted that the quality of the plows is important because lost nuts and bolts, as well as spare parts, are hard to obtain.

The project saw its first full-scale results from working with ox-plows in 2019. A 2018–2019 study compared ox-plowed plots with plots that had been hand cultivated with a hoe and revealed that the plowed areas had a 50% increase in harvest. However, no such study could be carried out in 2019–2020.

The third objective states, “1,000 households are provided with seeds and tools to support increased capacity for food production and provide a more nutritionally diverse household food basket.” This objective has two components: sorghum production and joint vegetable gardens. During house-to-house visits in 9 different villages in June 2019, BGRRF staff, RRCs, and community leaders identified 380 vulnerable households. Each of these received 15 kg of sorghum seeds and two hoes. Beneficiaries in four villages received training in land preparation, spacing of seeds, weed control, and harvesting. Close monitoring ensured that they followed the right planting methods to obtain good yields.

The joint vegetable gardens were established close to the river Kiir, to wells, or to boreholes, so that they would always have enough water. Starting in November 2019, after the rainy season, BGRRF formed 17 local groups (with a total of 380 healthy individuals that were able to work). Just as in the MHA project, participants each had their own plot in the joint garden. BGRRF bought seeds locally, because these are generally more drought resistant and the targeted households like these vegetables. In October-November 2019 BGRRF provided okra, eggplant, and tomato seeds, as well as chicken wire for fencing, hoes and spades. Watermelon seeds were distributed in June 2019, as the fruits would have withered away if planted earlier due to a lack of rain. Two trainings took place: one on the economic importance and nutritional value of vegetables, garden planning, land preparation, seed varieties, planting dates, spacing, and planting methods, and one on irrigation methods, weed and insect control, harvesting, storage, distribution, and sales. The actual implementation was led by the BGRRF agricultural officer, who also helped with fencing, land preparation, planting and irrigation, weeding, and monitoring of project progress.

Respondents almost always mentioned that the chicken wire was not strong enough, and that goats and other cattle could enter the gardens. Hence, they needed more and better quality wire. Some farmers actually slept in their gardens in order to prevent cow herds from coming in at night. In addition, they frequently mentioned pests and they expressed a desire to use insecticides. They also expressed their interest in having water pumps and more water-cans, because fetching water from rivers and wells is hard labor. All participants mentioned that late, irregular rains and intense heat (above 40°C) are serious problems. They seem to help some pests survive, make crops whither, while animals and people become seriously ill. The Kiir river is now also at a lower level than ever before, and more traditional coping mechanisms in food insecure periods, such as hunting hippos and crocodiles, are simply not feasible anymore, as these animals leave the river for most of the year. Fishing, however, continues.

In 2019, rains were good. As a consequence, most of the households needed less food relief. Unfortunately, in summer 2020, rains were late again, which reduced the harvest. Hence, BGRRF staff is paying greater attention to ensure that the selected vegetable garden sites are near water points that run all year round.

Generally, people were happy with the seeds they received, but some vegetable seeds did not germinate well. Similar to the MHA community gardens, the vegetable gardens in this project seem to have a varying impact on income, food access and food availability. There are participants who mentioned that they had enough food for their households and can sell some surpluses, and use the money either for school fees, medicine, clothing or shoes, or to buy other types of food. Others have indicated that the harvests so far have been rather poor (also due to the irregular rains which can cause droughts in one place and flooding in others, pests, and goats or other animals that can enter because of weak fences). Subsequently, they could only feed their families and not sell any surplus. “Beneficiaries are able to harvest more than four times from their gardens,” but there are differences among the households. In other words, food access and availability have increased, but not equally or enough for all participants. Although participants are able to better deal with the hunger gap, they cannot do so without some relief in July and August.

Regarding food utilization, the respondents pointed out that they could not yet produce enough seeds for the next planting season. They faced a hard choice between immediate consumption and saving seeds for planting. Unfortunately seed storages had been destroyed by the Khartoum government before independence. As long as seed storage facilities are not rebuilt (see below) and seed markets do not function, they will need seed provision by BGRRF.

Although it did not have a specific management objective, BGRRF is also changing its management. Just like MHA, BGRRF successfully incorporated the auditors’ suggestions to improve its accounting and administration in 2019 and 2020. In response to donor criticism calling for staff to be present more often “on the ground”, BGRRF began shifting its work and staff from Nairobi to Turalei, Twic state, in 2021 in order to reduce costs and be closer to its target areas. Finally, just as with MHA, COVID-19 has shown that the organization cannot depend on a few senior staff. As a result, it needs to establish succession plans and replacement rosters. In this vein, it needs to review its strategy, accounting, monitoring and evaluation (M&E), and HRM in order to determine how BGRRF can professionalize further. It could learn from the professionalization approaches taken by MHA and Caritas Gulu.

Caritas Gulu Archdiocese—Gulu, Uganda

Uganda is well-known for its relatively liberal refugee policies, in which refugee households receive a small plot of land for agriculture. However, these “individual arable plots of land … do not produce enough yield for refugees to become wholly self-reliant.“17 Caritas Gulu, the Emergency Relief and Development arm of the Catholic Church in the Archdiocese of Gulu, has become one of the operating partners of the Office of the Prime-Minister (OPM)18 and international organizations, in particular UNHCR. It is involved in providing life-saving relief and livelihood projects to the refugees and host communities in northern Uganda. It has branch offices in Kitgum, Gulu, Pader, and Adjumani. In addition, it also continues its more developmental work for Ugandans.

The overall goal of this project is to contribute to addressing the humanitarian needs of the South Sudanese refugees in Adjumani and Lamwo districts through an integrated approach to improve welfare and ensure minimal living conditions. In line with the official government strategy, 70% of the project resources go to the refugees and 30% go to the host community. Caritas Gulu has carried out similar projects since 2013. As a result, it knows the project components very well and its staff has considerable experience in implementing them. Due to the small plot size, it cannot carry out ox-plowing activities. Instead its first objective is the “Empowerment of 360 South Sudanese refugee youths through offering short vocational skills training.”

Every project year, 120 youths should receive a 4-months intensive vocational training in seven thematic areas: 1) Block laying and concrete practices; 2) Hair cutting and hair dressing; 3) Tailoring and garments; 4) Carpentry and joinery; 5) Driving and basic motor vehicle mechanics; 6) Metal fabrication; and 7) Catering and hotel management. Entrepreneurship is a cross-cutting theme in the curriculum of this training. Upon graduation, each student receives an initial capital investment and a start-up kit.

Demand for this training, and education in general, is so high that Caritas Gulu in cooperation with local leaders can be selective in choosing the most promising students. From mid-August to December 2018, 64 men and 56 women took part in this training; in 2019, 72 men and 48 women participated. Half of them studied in Adjumani, and the other half in Palabek (Lamwo). Due to COVID-19, the training for a cohort of 120 youths could not take place in 2020.

In 2020, UNHCR paid brick layers and carpenters, who had previously completed the vocational skills training, to construct shelters for persons with special needs (PSNs). Similarly, youths who had learned tailoring made face masks at UGX 1,000 each. Some of them mentioned they had made “100,000 masks.” These vocational skills graduates were able to make a living and support their families. In addition, some graduates from carpentry and joinery have set up their own workshops, which are profitable. They partner with other youths and share knowledge, skills, and tools, and they market their products to refugees and host communities.

Upon graduation, most of the graduates are able to make a living from their new livelihoods. This form of diversification of the local economy supports non-agricultural activities that are more resistant to weather shocks than agricultural activities are. Although it is likely that the graduates who are able to earn more money can also improve food access and utilization, there is only anecdotal evidence, and as of yet no impact assessment has confirmed this.19

The second objective aims “To strengthen 360 refugees and host community members in peacebuilding and conflict resolution.” The training of community leaders, especially from the Refugee Welfare Committees and Local Councils (84 refugees and 36 host community members in 2019–2020) aims to build bridges between leaders of the different ethnic groups among the refugees that were fighting each other in South Sudan, as well as between refugees and host communities, in order to reduce violence and promote peace. Community Development Officers, who are civil servants from Adjumani and Lamwo, provided the training with backstopping from Caritas Gulu staff. Representatives from OPM and UNHCR were also present.

Together with Sub-County Leaders and the Community Development Officers, these leaders engaged in peace dialogues with approximately 840 refugees and 360 host community members on the conflicts between their communities. The dialogues entail understanding context and root-causes of conflicts and tensions, acknowledging abuses and crimes on both sides, and mitigating (or preventing potential) conflicts. At the end of the dialogue, the participants pledge to address tensions surrounding such issues as water point use, fire-wood sites, food distribution centers, stone quarries, gender-based violence, alcoholism and drug abuse, and land conflicts, all in a peaceful manner. In addition, Peacebuilding Committees (PBCs) were set up to address: 1) Domestic violence; 2) Land disputes with host communities; 3) Drug abuse in the settlements; and 4) Theft and violence at water points.

In cooperation with OPM and UNHCR, Caritas Gulu also contributed to the so-called “peace weeks”, in which refugees from different ethnic and religious backgrounds carry out joint activities in which they imagine what a peaceful future in South Sudan would look like.

Finally, Caritas Gulu also produced information, education, and communication (IEC) materials, as well as radio messages. In 2019–2020, the IEC materials consisted of banners and flyers on peacebuilding and conflict resolution. Caritas Gulu also bought a Zoom communication system to continue interaction with refugees and host communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. A nearby radio station broadcasts the spot messages in two local languages to 1,500 refugees and host-community members.

To summarize, peacebuilding and conflict resolution training brings together people from the various refugee groups and host communities, who get to know each other better and thus focus on issues of joint importance, such as responsible use of scarce natural resources, sustainable development, and mitigation of existing conflicts. One refugee leader remarked “Some refugees have been intolerant and have fought over minor issues, especially during food distribution, at bore holes, in the market, and at health facilities. As leaders we have now been empowered to intervene before the conflict escalates to the community.” Another leader noted “We have also solved several disputes between refugees and host communities, especially on the issue of land. As a way of survival, some refugees hire land to cultivate crops. After tilling the land and planting crops, the landlord takes possession of the crops, which results in fights.” The high levels of violence that many refugees have experienced in South Sudan and the conflicts in the camps have hampered food access and availability. Hence, peacebuilding is an important but indirect way to enhance food security.20

The third objective entails “Support 3,600 South Sudanese Refugee Persons with Special Needs.” Each year, 1,200 PSNs receive non-food items. The PSNs are identified either when they cross the border or during the annual joint PSN survey under the leadership of UNHCR. Each PSN receives several non-food items (NFI), namely 1 jerry can, 1 blanket, 1 saucepan, 1 mosquito-net, 1 basin, 3 pieces of assorted clothing (for men, women and children), 2 plates, 2 bars of laundry soap, and 2 cups. According to Caritas Gulu, these “essential household items [go] a long way to reduce the vulnerability of, particularly, unaccompanied girls, women, and male youth” (Caritas Gulu Archdiocese 2018b, p. 6). PSNs reported appreciating the NFIs.

Finally, the fourth objective is “To support 3,600 refugees and host-community members with agri-based enterprises for sustainable food security and livelihoods.” With support from refugee leaders, Caritas Gulu identified 120 farmers (84 refugees and 36 host community members) for training on best agronomic practices regarding the seasonal calendar, land preparation, nursery bed preparation, watering and moisture retention, transplanting, weed control, thinning, pest and disease control, and post-harvest handling. These farmers established their own demonstration gardens in order to transfer knowledge and practices to other community members. In addition, 36 lead farmers and 4 Caritas Gulu staff members visited two demonstration farms to learn more about growing crops and raising animals.

Also, a total of 3,600 farmers (1,200 per year) receive support with agricultural inputs, in particular vegetable seeds, farm tools, and trainings, during the project period. They also visit and learn at the demonstration gardens of the farmers that have received the agronomic best-practices training. In terms of food utilization, special attention was paid to sun-drying vegetables to provide additional foodstuff during the off-season.

In sum, new and effective agronomic practices have been introduced to refugee farmers and host communities. However, structural problems beyond the scope of the project (such as dry spells, small plots, pests, crop diseases, ongoing insecurity, as well as COVID-19) hamper agriculture. As a result, food access and availability are improving, but somewhat less than intended.

Evaluations, Audits, Workshops and Follow-Up

The 2019 and 2020 evaluations were more process evaluations than impact evaluations. They described the progress the organizations had made and the problems that occurred during project execution and in their internal management. They described that the organizations had made progress in a flexible manner, but that the actual impact of their activities could not be measured easily in the absence of a base-line. Nevertheless, discussions with beneficiaries and staff, as well as comparisons of the three organizations, helped to identify problems and opportunities, as well as to develop recommendations.

To help better achieve the three project’s objectives, Caritas Germany asked the participating organizations to work on the recommendations of the first evaluation and organized a workshop in Wau in September 2019. Each organization sent 6-7 staff members.21 Caritas Germany also brought in five people from Germany and Nairobi. The workshop consisted of three parts. The first was a lessons-learned exercise based on the 2018–2019 evaluation that compared the three organizations, as well as their slightly different target groups, activities and priorities. The comparison worked like a natural experiment: it showed ways to expand or improve their partially overlapping activities and add new ones. The participating organizations encountered similar problems, such as deforestation, and all needed to build their capacities in monitoring and evaluation. Second, the organizations compared the different types of seeds that they provided for their agricultural activities. The largest part of the workshop consisted of M&E training (including materials from Phineo). Finally, the partners visited the hospital, the demonstration gardens, and a village of the MHA project.

During the workshop, the three organizations noticed and then began to discuss what they could learn from each other—a practical form of South-South cooperation. BGRRF wanted to establish seed storage capacities (for which it could use DMI’s storage in Juba as an example). MHA and Caritas Gulu decided to set up larger demonstration gardens. MHA also wanted to start teaching local soap production (a DMI activity) and energy saving mud-stoves (a Caritas Gulu activity). All organizations also worried about the negative impact of climate change and deforestation on local agriculture and food security. During the workshop, enthusiasm grew about what the three organizations could learn from each other and do together. They wanted to start training visits to each other to learn more about one another’s activities and management approaches. When possible, they also wanted to lobby politicians and church authorities together. The workshop training in M&E concentrated on understanding output, outcome and impact indicators,22 as a form of capacity building. Ideally, this would also help to improve future project objectives. In addition, M&E can then evolve into monitoring, evaluation, accountability and (joint) learning, with capacity sharing among the Ugandan and South-Sudanese organizations.23

Similarly, the organizations were audited annually to strengthen their management. The auditors worked with staff-members on the execution of the projects during their field visits. With their recommendations, the auditors indicated how reporting and internal administrative procedures could be improved. When necessary, they provided on-the-job training. They also paid follow-up visits to check the implementation of their recommendations. The auditors noted that all their recommendations had been implemented or were close to being done so. Hence, audits also became a form of capacity building.

After the workshop, Caritas Germany decided to provide funding that would help to implement the activities identified in the lessons learned section of the Wau workshop. It asked the three organizations to develop follow-up projects, which piggy-backed on the Phineo program and were thus called Rucksack projects.

While writing these projects, the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Caritas Germany allowed for the inclusion of preventative and responsive public health measures. In addition, the organizations started demonstration gardens with staple crops, such as sorghum, maize, and cassava, and with seedlings for woodlot and fruit trees to begin reforestation. Some of these fruit trees, such as mango and shea, can also help people in need to earn a bit more income and bridge the hunger gap. The gardens will also be used for training on ox-plowing and introducing other agricultural techniques. For example, the husbandry of small animals, such as chickens and rabbits, can help address protein deficiencies or slightly increase income. Both MHA and Caritas Gulu can sell the produce from the gardens to earn money or distribute it to people in need. In this way, the demonstration gardens also make both organizations a bit less dependent on donor funding. BGRRF was able to build its own seed storage and MHA began its soap production. Finally, the organizations also began looking for learning opportunities with other project activities, such as vocational skills training. Moreover, with support from Caritas Germany, but outside of the Phineo program, Caritas Gulu has been working for the last 7 years with village savings and loans associations (VSLA), as a form of micro-credit. Recipients from MHA have started their own simple forms of micro-credit, and it would be interesting to incorporate the more advanced VSLA system from Caritas Gulu. The organizations were especially looking forward to their joint visits, but only a few could take place in 2020 and 2021 due to COVID-19.

They are now also thinking about the role that raids and violence play in the areas in which they work. The main cause of these raids is that dowries today include so many cows that raids are practically the only way to obtain sufficient cows. What can the organizations, in cooperation with the Church and government officials, do to raise awareness of the connection between cattle raids and dowries and to bring the dowry price down?

At the time of writing, the last evaluation is about to begin. It will focus less on process and more on the actual impact of the three projects.24 It will also provide inputs for a new workshop on lessons learned. Unfortunately, Phineo decided to focus more on Germany and not support a second project for an additional 3 years. The organizations, however, will continue their cooperation.

Analysis: Time and Trust to Develop Capacities

In line with Roepstorffs (2020) criticism of the problematic dichotomy between the concepts of “international” and “local”, the organizations studied show the ambiguities of localization. In different ways, these organizations combine international with local aspects. The main reason to call them local is their presence “on the ground” and their knowledge of the target areas and the “local” populations. Yet, as faith-based institutions and through their staff, networks, and the aid chain itself, they have crucial international organizational aspects.

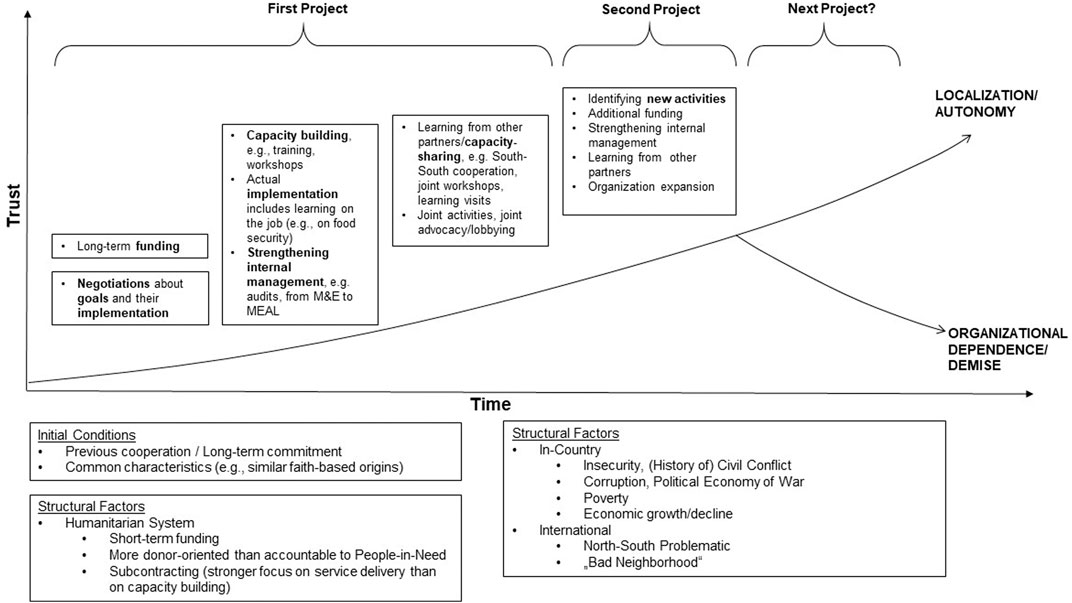

Normatively, the ideals behind localization are sound, but their implementation requires intimate knowledge of “local” organizations’ context and capacities—and ways to strengthen these capacities. Localization works well when these organizations work well. The underlying issue of localization is strengthening the effectiveness of actors in the aid chain, so that they can become more autonomous. Hence, improving “localization” implies establishing a long-term process to build or share capacities on both management and the substantial issue at hand (McEvoy et al. 2016, p. 531). In this case, the issue area of food security (with some food aid) and its management. Such a process view also helps to understand the linkages among different issue areas and actors. Ideally, this process leads to mutual understanding and real partnership of the actors in the aid chain over time. Although, this may take years to achieve in daily practice, the Phineo program shows that the urgent need to save lives immediately does not have to drive out longer-term capacity development.

Five aspects are crucial in this respect. First, the organizations ideally have a long-term relationship, which fosters trust among them.25 Such trust implies that the organizations create the opportunity to learn over time. It helps if the organizations have already worked together before on related projects. In this case, their joint Roman-Catholic background also has helped to build trust and to emphasize long-term partnership. Moreover, many staff members of the organizations, in particular those in religious service, exhibit a strong motivation to help people in need without asking much in terms of worldly rewards. They often work for a long time in the target areas, so that they know the local context well and can cumulatively reach results, for example in institution building. By contrast, many secular NGOs have international staff that works for much shorter times and higher wages in humanitarian crises. The latter NGOs themselves generally stay for a shorter period of time. In the long term, this gives a comparative advantage to the three organizations discussed here.26

Second, it is crucial that the organizations involved establish a process to reach a joint agreement on shared (project) goals and objectives, because this can initiate the process of joint learning to realize these goals. In this way, the relationships in the aid chain can develop beyond sub-contracting. Donors do not necessarily need to set the tone alone. Instead, the agreement on joint project goals and objectives (i.e., sub-goals) fosters clarity that helps build trust and shift the focus of localization to the practical implementation of activities on the ground. In this vein, the organizations should also initially focus more on learning with regular monitoring and process evaluations rather than on quantitative impact evaluations. The former build more capacity because they allow for recommendations and follow-up, and because they explain the implementation processes (and obstacles) that lead to specific outputs and outcomes on the ground.

Third, localization is not a process that can stop after one project, rather it needs to become an ongoing process. A series of projects offers more learning and capacity development opportunities and thus long-term funding is vital. Phineo provided funding for 3 years, including workshops, evaluations, and audits, which helped to strengthen daily management. Caritas Germany then enabled the Rucksack projects to build more synergies among the three organizations and to address gaps, such as deforestation and MEAL, and initiate new activities. As a result, organizational learning could take place. Ultimately, the international organization needs to supply long-term funding and pay specific attention to activities, such as demonstration gardens and seed storage, that make the “local” organizations more autonomous.

Fourth, there needs to be improvements in the relationships between donors and international NGOs, and with NGOs on the ground. Providing funding for several years and allowing for capacity development, which helps to make localization more effective, strengthens trust over time. Donors should be prepared to let the NGOs and their international counterparts negotiate the objectives and the best way to implement them, as Caritas Germany and its three partners could do in the Phineo project (even though, as indicated above, they initially lacked time to establish a base-line before the start of the project. Over the course of the projects, however, the three organizations have been able to establish relevant indicators on food security and begun collecting relevant data, for example on MUAC and increased crop yields and their use. As a result, they are beginning to provide trend data on the impact of their activities).

In addition, South-South cooperation among participating organizations also offers essential learning opportunities and capacity development synergies. The southern organizations can benefit quickly from the experiences of the other southern organizations, because they frequently share similar challenges. Quite often, if one organization succeeds with certain types of activities, others find their experience credible and replicable. They will often also learn that their own struggles do not mean that they have to identify all solutions by themselves. Sharing capacities is crucial to developing capacities.

Finally, it pays to include an objective on improving the quality of internal management in all projects. MHA had such an objective in its Phineo project, and BGRRF and Caritas Gulu included similar objectives in their Rucksack projects. Doing so allows for learning in such different areas as organizational strategy, HRM, finance, and MEAL. In addition, it facilitates incorporating new substantive activities on the ground, such as reforestation and climate change adaptation, with strengthening managerial capacities. If done well, the benefits of localization can then continue flowing once the project(s) have ended.

The topics of reforestation and climate change adaptation also show the limitations of localization, even of relatively successful localization examples as described in this article. Normally, NGOs cannot address structural factors, such as the North-South problems, lack of funding, armed violence, and climate change. Still they can learn from each other and launch (joint) activities as mentioned above. Together with international NGOs they can also carry out lobbying and advocacy campaigns to address these structural factors with governments, church officials, and international actors.

The “local” organizations may become a bit more autonomous in the course of a project, but as long as these structural factors remain, cooperation between international and “local” NGOs will remain necessary.

The Two-T’s Conceptual Model of Localization

It is possible to abstract the empirical and analytical findings above into a conceptual model. The crux is to foster trust (y-axis) among the organizations in the aid chain over time (x-axis) by making sure that their activities become more effective, so that the organizations on the ground can achieve a higher degree of autonomy (the rising arrow). But this is a tall order, efforts at localization regularly fail, which can lead to a higher degree of dependence, or ultimately organizational demise (the falling arrow). Hence, successful localization is never finished, but needs to be reinforced time and again, for instance, through new projects and new activities. Ideally, the “local” organizations increasingly identify their own resources or alternative donors for such projects and activities. In other words, they succeed in diversifying their funding (See Figure 2).

When the initial conditions are conducive, trust is stronger in the aid chain early on. If the organizations have already worked together in the past, or if they share a common faith, as Caritas Germany and the three organizations do, they can start with a higher level of trust.27

At the same time, all forms of localization will come up against structural factors that diminish trust and bend the curved arrow down over time. As described above, accountability in the humanitarian system is more donor-oriented than oriented towards to people in need. In addition, in-country factors, such as insecurity and corruption, or international factors, such as the North-South problems, influence localization negatively.

Multi-year funding is essential for both capacity development and implementation of activities (in this case of food security activities). Crucially, the organizations involved need to agree on goals. Sufficient baseline information on needs can facilitate this. The motivation of the actors that will execute project activities is central in this respect; they should contribute to and agree with the formulated goals. The funding organizations also need to agree on the goals. Negotiations on the feasibility of goals should be combined with strong advice on the best way to reach these goals during implementation. This should be accompanied with capacity building. The same happens with South-South cooperation, which can result in the identification of learning opportunities with each other and new activities, as shown above with reforestation. In this way, all organizations in the aid chain can learn from each other.

The three organizations were lucky that Caritas Germany invested in the Rucksack projects, so that they could fill the gaps of the Phineo program, begin to respond to COVID-19, and also incorporate new activities. As stated, they also focused on strengthening internal management capacities, especially reporting and MEAL. Unfortunately, Phineo is increasingly focusing on Germany and will not provide funding for a new round of projects. However, with their improved capacities, demonstration gardens, and storage, the three organizations have become a bit more autonomous and can continue to expand their agricultural activities independently. They are also engaging with new donors.

Ultimately, if localization, in particular its capacity development, goes well, donor and intermediary organizations would be able to shift their attention from supporting organizational capacity development and implementing project activities to focusing on outcome and impact assessment. In other words, they could shift their attention from providing inputs and supporting and checking organizational management on a more or less continuous basis to assessing and reporting outputs. outcomes, and impact at regular intervals, such as project design, mid-term reviews, and final evaluations. This shift would free up resources that could go from support and management control to (more) activities in the field. However, at the moment, this is still a distant objective. For now, most attention needs to be given to strengthening the organizations and their activities for people in need.

Conclusion

This article asks how and to what extent do these organizations make localization work and what can we learn conceptually from them? By studying the everyday practices of three “local” NGOs and Caritas Germany in realizing project objectives, this article explained from a relational aid-chain perspective how these organizations make localization work.

The evaluations on which this article is based clearly show that the need for the Phineo food security program is very high. Food insecurity affects the target groups of the three organizations to different degrees, but they all require food aid, tools, training (e.g., in ox-plowing and agricultural techniques), and agricultural inputs. Additional training in areas such as, micro-credit activities, soap production, and vocational skills also supports livelihoods that further help improve food security. All in all, the Phineo program has slowly but steadily improved food security, but more long-term support remains necessary.

Methodologically, the situation in which these three NGOs operate can be described as a hard case, due to the armed conflict, poverty, climate change, and displacement. The research outcomes are therefore relevant in other cases, where the environment is more conducive and needs are lower, so that localization can be achieved somewhat more easily. The longitudinal set-up of this research show that localization and the substantive issues at hand (food security, some food aid, and capacity development) absolutely need to be studied together to understand their dynamics. Studying localization without simultaneously addressing the substantive and managerial issues tends to lead to a lack of understanding of the opportunities and constraints of localization. Put differently, defining localization as a stand-alone issue does not make sense.

The organizations in this case-study show that long-term relationships can foster trust. In addition, long-term funding can over time promote substantive activities on the ground and capacity development by strengthening internal management and South-South cooperation. New activities, not just ox-plowing and tree planting, but also further developing managerial capacities can positively impact both food security and localization. However, they cannot completely overcome structural factors.

In this respect, finding more innovative ways to jointly address structural factors and more longitudinal, comparative research on the dynamics of localization in the different types of aid chains are especially promising avenues for future research. They can help fine-tune or critique the conceptual model. This study focused mainly on the organizations involved, future research should also take the capacities of the target communities more into account. The conceptual model shows that localization is possible but usually requires strong capacity development over several years, before a higher degree of autonomy is reached. Otherwise, localization is bound to fail.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The organizations provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1A 2018 ODI study, also taking into account indirect funding through one intermediary, for example an international NGO or UN organization, comes up with a somewhat higher number of 10–13%. See Willits-King et al. (2018).

2In other words, the aid chain is a relational concept.

3Note that advocates of localization would then argue that these organizations should receive access to this knowledge in order to further develop their capacities.

4The three “local” organizations also show how relative the term “local” is; in different ways they are also part of international networks. First, all three are related to the Roman Catholic church. In this sense, they are global and local at the same time. Second, they have all worked on different projects with Caritas Germany over the last decade or more. Yet, they also have deep local roots. They know their target areas and inhabitants well. Third, although the three organizations knew some of each other’s staff members, they knew the specific activities and target areas of the other organizations only superficially, given the large distances between them. Fourth, each organization also has international staff and covers a relatively large geographical area spanning various villages or even districts. As explained below, BGRRF actually has its headquarters in Nairobi and operates in both South Sudan and Sudan.

5See Fr. Habeel (2020), Esuruku (2020) and Kämpf (2020).

6Currently, it increasingly focuses on activities in Germany.

7I would like to thank Ydo Jacobs for suggesting this turn of phrase.

8Due to a mistake in the project calculations, MHA had to pay for some of this relief from its own resources.

9A local type of long spade.

10Feddan is a local size of fields. 1 feddan = 4,200 m2.

11Abyei Town was destroyed in 2008 and 2011. Many IDPs, mostly Ngok Dinka, settled in Agok, which grew into a town of 130.000 people with administrative facilities, a large market, an MSF-supported hospital, a government hospital, and several schools. Twic state borders on the Abyei Special Administrative Area.

12On average, one household has seven members.

13The RRCs were set up with Cordaid and Catholic Relief Services, together with BGRRF staff in a 2012–2013 project.

1410% of the relief goods are distributed by the Missionaries of Charity (Sisters of Mother Teresa) in Turalei. The sisters verify “their” households, but reporting is done by the BGRRF.

15When people go without food for 4 days, they eat tree leaves, billet—an edible grass—, and lalop–a wild fruit.

16Unfortunately, the so-called black cotton soil in Abyei is too hard in dry periods, and in rainy periods the rain cannot drain out. As a result, ox-plowing is not possible in Abyei.

17UNHCR (2019) South Sudan Regional Refugee Response Plan, January 2019-December 2020, Nairobi, p. 7.

18OPM is the Ugandan institution that is responsible for the refugees, it has branch offices in all refugee-hosting districts.

19A 2018 impact evaluation indicates that the vocational skills graduates from an earlier project are generally better able to make a living than they were before their training. See Caritas Gulu Archdiocese (2018a).

20After armed inter-ethnic violence and killings in the Palorinya refugee settlement, UNHCR moved 750 people to Palabek in November 2020. UNHCR mentioned Caritas Gulu’s peace-activities in the latter settlement camp as a reason for this transfer in the hope that future conflicts could be prevented.

21DMI staff from Juba also participated.

22See the Phineo Handbook on Impact Assessment by Kurz and Kubek (2021).