94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 13 September 2021

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.705200

This article is part of the Research TopicEconomic Integration and Political Change in DemocraciesView all 7 articles

The integration of Latin American countries into the global economy has historically proceeded through the export of primary commodities, a dependency that has long exposed them to developments in core industrial nations, changing terms of trade, and “resource curse” externalities. However, in the early 2000s, a new commodity boom coincided with the arrival of left-of-centre administrations across the region forwarding post-neoliberal visions of development where extraordinary export rents were destined to expand public spending and progressive welfare policies. While the relationship between Latin America’s left turn and this latest boom has been well-covered in the literature, much less has been said about developments in the 2010s, when the end of that boom sent many of these projects tumbling, fuelling political discontent and facilitating the arrival of conservative administrations in places like Argentina, Brazil, and Ecuador, among others. Thus, this article explores the relationship between global integration and political change by looking at the case of Argentina, and developments during the second presidency of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (2011–2015), when falling agricultural commodity prices aggravated social tensions and political conflicts as the government sought to navigate a “governance puzzle” through which it attempted to square high public expectations for revenue redistribution with falling fiscal collection. In particular, we analyse the co-evolution of global economic conditions, macroeconomic disequilibria, and domestic political pressures, considering how this led the government to lock itself into a distributive conflict pattern that dissatisfied both opposition sectors and important segments of its support base. As such, this case study illuminates the structural challenges confronted by governments in developing economies pursuing ambitious developmental and socially-progressive agendas, while elaborating the political implications that current account and fiscal disequilibria may produce in these contexts.

The Latin American pink tide describes a period of major economic and political change between the early 2000s and mid-2010s, when several left-of-center administrations promoted “post-neoliberal” visions of development that combined commodity-led exports, active state intervention in the economy, and marked welfare and wealth redistribution policies. Pushing regional growth to its highest level in 40 years, the literature linked the initial success of this agenda with beneficial terms of trade and surging demand for the commodities these economies exported, enabling these administrations to channel significant resources into welfare and political inclusion projects (Ocampo, 2008; Panizza, 2009; Levitsky and Roberts, 2011; Grugel and Riggirozzi, 2012; Nem Singh, 2014). However, as this commodities boom died down, economic growth stagnated, zapping much of the social progress achieved, while politics became increasingly contentious—with mass protests engulfing countries like Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela, among others, and conservative parties coming to power and implementing more orthodox economic programs.

This pattern of economic crisis and political change reveals how vulnerable Latin American economies remain “both to economic downturns and to political conflicts in hard times between insiders and outsiders” (Kingstone, 2018, p. 149). Moreover, it underlines the perennial challenge faced by governments in the region in terms of reconciling a dependent pattern of integration into the global economy and the political and policy stability necessary to implement reforms and sustain development and growth (Rojas, 2017; Ruckert et al., 2017; Grugel and Riggirozzi, 2018; Kingstone, 2018). Indeed, a number of authors have elaborated this challenge. For instance, (Ellner, 2019, p. 14) argues that facing an adverse global scenario, the “disloyal opposition” by status-quo elite and business sectors pressured leftists governments into implementing “populist programs that held back economic development and fostered paternalistic relations,” blocking the space for reforms. Similarly, Saad-Filho and Morais (2014) see the eroding support for the Brazilian Workers’ Party (PT) as the outcome of a “confluence of dissatisfactions”: from affluent sectors resenting the loss of privileges during the boom, and from defecting popular sectors that felt their gains jeopardized as conditions deteriorated. Others view political instability as the natural consequence of the limits of the rentier model adopted by many regimes in the region, noting how winning the “commodity lottery” allowed the Kirchners, Rafael Correa, Evo Morales, and others leftist leaders to fund “rentier-populist coalitions” that could not be held together when expenses could no longer be covered (Weyland, 2009a; Mazzuca, 2013; Castañeda, 2015).

While the idea that Latin American economies are vulnerable to global economic shocks is far from novel, in this article we investigate the governance challenge the end of the commodities boom presented to progressive administrations. Avoiding overly economistic arguments about the unsustainability of “macroeconomic populism,” which frame any deviation from macroeconomic orthodoxy as destined to fail and leave little room for politics, as well as voluntaristic political arguments that minimize the importance of macroeconomic dynamics and attribute failure to the reactionary character of Latin American middle classes, business elites, or right-wing parties, we approach this puzzle in terms of Dani Rodrik (2007)’s trilemma on the incompatibility between democracy, national sovereignty, and global economic integration. As such, we consider democratic governments in developing economies face a particular challenge to balance constraining economic and socio-political factors that may move with different velocities and in different directions: the tidal ups-and-downs of the global economy, the sluggish reform of domestic economic structures, the inertia of social expectations and political values, and the high frequency of democratic politics. Hence, while accepting that there are no quick “technical” or political solutions to this puzzle, the article considers three general questions raised by this recent regional experience: What space did pink-tide administrations have to reconcile their progressive political visions and priorities, demands from the citizenry, and global and domestic macroeconomic restraints as the boom subsided? How did they try to do so? And what are the implications this has for democratic politics and governance?

To investigate these questions we examine the case of Argentina roughly during the second presidency of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (2011–2015). A number of reasons make Argentina an interesting case to discuss how economic development and politics intertwine, with the country long puzzling economists and political scientists—with Nobel Prize-winner Simon Kuznets attributed with the apocryphal observation that there are four types of countries: developed, underdeveloped, Japan, and Argentina (Economist, 2014). Behind it, lies the notable economic involution the country has experienced over the last century, since it socio-economic indicators were at the level of the world’s most advanced countries, making it “one of the most dramatic examples of divergence of the modern era” (Taylor, 2018, p. 1). This unusual trajectory shaped a society that for much of its modern history was the richest in the region (even today it remains the fourth wealthiest economy in Latin America, excluding island nations), and possessed the largest middle class, the most extensive welfare system, a strong labor movement, and a highly educated urban population, but that nonetheless has experienced chronic and profound macroeconomic and political crises (Romero, 2002; Bulmer-Thomas, 2003; Adamovsky, 2019). As a matter of fact, the commodities boom of the 2000s hit Argentina whilst coming out of the most severe economic crisis in its history, and facilitated one of the most rapid recoveries in the period. At the same time, the country is characterized by a rather contentious democratic culture shaped by the hegemony of Peronism, a mass labor-based populist movement that since mid-20th century promotes a vision where economic and social progress is associated with an interventionist state and an inward-oriented model of industrialization—a vision further advanced by three Kirchnerist administrations between 2003 and 2015, first by Néstor Kirchner and then by his wife (from now onwards, CFK) (Levitsky, 2003; Levitsky and Murillo, 2008; Etchemendy and Garay, 2011). As a result, the country is populated by a “society little tolerant to resign what it considers acquired social rights” (Gerchunoff et al., 2020, p. 320). Moreover, during the period in question the country experienced the pattern of macroeconomic boom-and-bust and political change we are interested in discussing: an upward phase where the government drew on agricultural export rents to fund expansive welfare and income policies, which contributed towards raising living standards and granted Kirchnerismo political dominance, and an highly contentious downward phase as macroeconomic conditions deteriorated, leading to a presidential defeat in 2015 against a right-wing candidate (Levitsky and Murillo, 2008; Wylde, 2013; Lupu, 2016).

In this regard, we consider that Argentina during this period offers an “extreme” case study of distributive conflict in a developing economy: a country with a sizable commodity-dependent economy with high and recurrent macroeconomic instability, where political competition and conflict largely revolve around distributive issues and developmental visions. As pointed out by (Seawright and Gerring, 2008, p. 302), while extreme case studies should not be treated as representative, they are relevant when selected as a “conscious attempt to maximize variance on the dimensions of interest,” as they serve to probe complex causal mechanisms and possible effects and allow formulating more specific hypotheses to be interrogated with more determinate methods (Bennett and Elman, 2006). Hence, even if Argentina’s governance puzzle may be particularly pronounced, not only does it serve to illustrate the political economy of political conflict and change in a democratic developing economy, but it offers insights to discuss broader developments in the region, as we do in the conclusion.

Conceptually, we depart from recent work by Argentine political economists on the relationship between macroeconomic (dis)equilibria, distributive conflict, and populist governance (Damill et al., 2015; Gerchunoff and Rapetti, 2016; Gerchunoff et al., 2020). As explained, the basic idea by these authors is straightforward: governments in the region face accentuated distributive tensions resulting from demands in their societies for the improvement of living conditions and the quality of public goods, and from the structural limits their economies have to deliver these conditions and goods in the short to medium term. Thus, while certain external circumstances can temporarily create “opportunity periods” where these tensions are relieved, such as excess liquidity in global financial markets or commodity booms, these constraints limit the space these governments have to balance economic stability and the social and political conditions facilitating political continuity and governability. On this basis, we consider these global opportunity contexts pose a certain challenge for Latin American democracies, and particularly for left-leaning administrations. This is because during the global expansive phase, these administrations have a strong incentive to address extant distributive grievances in society and reward their support base, increasing public spending and adopting major welfare commitments. As global economic conditions deteriorate, these commitments can turn into political and policy traps, as administrations are forced to pick between unpopular contractive policies that would damage their credibility and electoral appeal, or to maintain their commitments while overstretching economic resources and risking further destabilization of economic variables—what Gerchunoff et al. (2020) denominate the “populist temptation.” These entrapments risk aggravating both macroeconomic disequilibria and political contention, making policy continuity and the achievement of political consensus more complicated, while increasing the stakes of political change.

The analysis is structured is two broad sections. In the section ahead we elaborate the conceptual framework and texturize it through a historical review of developments in the region during the second part of the 20th century, with a focus on the challenge these economies faced to sustain growth and welfare while dealing with balance-of-payment (BoP) restrictions. In the second part, we briefly characterize how the 2000s commodities super-cycle favored the success of left-wing post-neoliberal projects, prior to centering on the dynamics of political change affecting Argentina as the boom subsided. This is done by adopting a processual narrative that traces the co-evolution of macroeconomic and political factors, and contextualizes the political and economic challenges faced by the CFK government and the implications of key policy measures during her second administration. To do this, we triangulate insights on Argentina’s political and economic developments drawn from academic bibliographies in comparative political science, economic history, and development economics, findings in the grey literature produced by relevant economic institutions and think tanks (i.e. ECLAC, OECD, World Bank), and analyses of macroeconomic data drawn from Argentine official sources, international organizations’ databases, and local economic consultancies.1

Drawing from a long tradition in Latin American economic thought, the idea proposed by Gerchunoff et al. (2020) is concise and elegant. Fundamentally, the authors argue that government economic policy revolves around a dual barycenter, the productive possibilities of the economy and the economic aspirations of society, which configures two general objectives: macroeconomic equilibrium and social peace. In simplified terms, the former is defined as the point (E) where internal and external accounts are balanced, a balance that externally is a function of a real exchange rate of equilibrium and internally of a mix of economic policies, monetary, fiscal, and income-wise, compatible with full employment.2 To this they oppose what they denominate the macroeconomic point of social equilibrium (S), defined in terms of rooted values and norms of social justice that society upholds—and that can also be defined as a function of a real exchange rate of (social) equilibrium and related wage and employment levels (Ibid., p. 310). In this way, the locations of both E and S are “structurally” defined: while E is dependent on long-term factors configuring the macroeconomic possibilities of the economy, such as sectoral capital stocks, natural endowments, the level of economic productivity, and long-term terms of exchange, S is shaped by a structure of values and consumption aspirations, which manifest in long-standing income demands and expectations about social rights and the provision of public goods (Gerchunoff and Rapetti, 2016; Gerchunoff et al., 2020).3 On this basis, the authors pose that the gap between E and S serves a measure of the level of distributive conflict in society. While misalignments are relatively unproblematic when this gap is narrow, as in advanced welfare economies where “labor militancy is low, and a broad-based consensus exists around the distribution of income and the redistributive role of the public sector” (Sachs, 1989, pp. 2–3), when the level of income and value of the currency guaranteeing social peace is consistently above (in figurative, not mathematical terms) what the economy can deliver, as it occurs in many developing economies, we are in the presence of “structural distributive conflict” (Gerchunoff and Rapetti, 2016).

The second contribution the authors make is to link structural distributive conflict with an intensified populist dilemma or temptation, insofar as they consider that in these circumstances governments experience a strong political pressure to achieve an exchange rate and wage levels incompatible with E. Implicit in this argument are two relevant considerations often taken for granted in development analysis but that condition the political governance of these pressures: many countries confronting this situation are dependent economies and democracies, so that while much of their macroeconomic stability depends on economic circumstances they cannot control, political elites have a natural inclination to try to appease social demands sooner rather than later, to avoid social discontent and electoral punishment. For this reason, these governments can be expected to be particularly exposed to the temptations of macroeconomic populism; policy perspectives that emphasize economic growth and income redistribution to improve the situation of the working class, while deemphasizing “the risks of inflation and deficit finance, external constraints and the reaction of economic agents to aggressive non-market policies” (Dornbusch and Edwards, 1990: 247; Damill et al., 2015: 10).4 Now, while orthodox economic approaches treat macroeconomic populism as a myopic form of economic mismanagement, Gerchunoff et al. (2020: 311) adopt a more considerate political and practical view, pointing that the populist dilemma emerges from governments’ awareness of structural distributive conflict and from attempts to satisfy social demands first, to enjoy a certain space of political action, while they find ways to bridge E with S. It is for this reason that these economies show a tendency to display “twin deficits” in their current and fiscal accounts, as they are inclined to appreciate their exchange rate to raise salaries, and to expand the provision of public goods over fiscal resources—particularly in contexts characterized by high informality and where large sectors of society are excluded from basic social security, as it is the case in Latin America and other developing regions. With this, these authors underline the political challenge posed by structural distributive conflict, and the concrete governance dilemma that democratic authorities confront on the way to development, as not only policy decisions are taken under conditions of high uncertainty but in competition with political opponents and voters that quickly can lose patience that objectives will be met and promises be kept—with Gerchunoff et al. (2020: 313) highlighting the well-known adage that political times tend to be shorter than economic ones. Moreover, it offers up a general platform to consider the different means through which governments try advance their political and policy preferences in a region where “bitter economic conflict is one of the central phenomena of economic life” (Sachs, 1989, p. 3), while dealing with the push-and-pull of the diverging locations of S and E, changing global economic circumstances, and the political costs of privileging one point of equilibrium over another.

Therefore, and in order to better capture the relationship between governance dilemmas, (macro)economic restrictions, and dynamics of political change, in the section ahead we review the political economy of development and distributive conflict in Latin America during the last decades, setting up the background to discuss contemporary challenges.

Latin American countries integrated into the global economy through the exporting of primary commodities (i.e. mineral, agricultural products, oil) (Bulmer-Thomas, 2003). This dependent relationship is maintained to the present day—in 2016 over half of the region’s exports (excluding Mexico) were commodities, whilst a further 23% were natural resource-based manufactures—and remains fundamental to understand the developmental challenges and political conflicts this region has experienced during much of the 20th century, and its generally lackluster economic performance (Ocampo, 2017; OECD, 2019, p. 103).

In this regard, one of the most fundamental aspects highlighted in structuralist and post-Keynesian economic literature has been the effect of what is known as the “external constraint,” as dependent economies rely on export markets not only to place their products but to obtain hard currency revenues—since mid-20th century, mainly US dollars—to import foreign-made goods, needed to satisfy the requirements of industrial and economic sectors and the consumption needs of their populations (Prebisch, 1962; Thirlwall, 1997; Hofman, 2000; Cimoli et al., 2009). Since the thirties, Latin American thinkers already saw that in this external constraint there were two major problems for industrialization. First, as noted by Raúl Prebisch (1962: 2), to raise the standard of living of their populations these countries needed to increase the overall productivity of their economies, something that could only be done by saving and re-investing enormous amounts of money. However, dependency meant that any shortfall in international demand would directly impact on the health of external and internal accounts, as foreign trade constituted the main source of public revenue for these states, affecting their ability to mobilize capital for investment. Second, growing exports presented a problem insofar as they led to an appreciation of the real exchange rate and to a monetary expansion “leading to the use of foreign currency for purposes not always compatible with economic development” (Ibid.). This is because as societies got richer, the demands for imported goods grew faster than the productivity of their commodity-based exports, contributing to trade account and BoP problems. Over time, the correction of this “dollar shortage” would require painful and unpopular measures, involving fiscal contraction, the devaluation of the currency, and the lowering of salaries to bring the BoP into balance, measures that intensified distributive conflict and political confrontation.

Economic historians find in early “stop-and-go” cycles in the region, where economies, salaries, and public spending expanded when global demand was strong only to bust as global terms of trade deteriorated, the origins of the anti-export bias that became characteristic of Latin American political ideologies since the forties and fifties, as “it became tempting to reduce incentives to export to economies that could not pay in cash and to court the masses by increasing real wages and allowing increased domestic consumption of exportables” (De Paiva Abreu, 2006, p. 120; Taylor, 1998; Bruton, 1998).5 As noted in Boianovsky and Solís (2014), Prebisch and others ECLAC-related thinkers concluded that the long-run rate of growth of Latin American economies was determined by the relationship between the income elasticity of their primary exports; that is, how much their products were demanded as the world got richer, and the income elasticity of their imports; how much imports grew as their own populations got richer.6 If this relationship was to remain low, currency shortages would limit the rate of growth of peripheral economies and make them permanently lag behind developed ones. In light of the “elasticity pessimism” of the time (a strong belief that terms of trade were deteriorating against the commodities exported by peripheral economies, what is known as the Singer-Prebisch thesis), the proposed solution to the external constraint required unorthodox policies and active state intervention, using an overvalued exchange and high wage rates to increase domestic demand and stimulate the local substitution of consumer and capital goods (Taylor, 1998; Toye and Toye, 2003). These ideas became codified into a autarkic paradigm of economic modernization, import-substitution industrialization (ISI), which became “officially” adopted by most Latin American republics that had completed the first stage of industrialization (Hofman, 2000; Bulmer-Thomas, 2003, p. 270).

Importantly for our argument, the ISI paradigm implicitly carried a model of governance of distributive conflict until industrialization was achieved. On the one hand, the state would have to intervene to steer economic activity through industrial planning, relying on tariffs, import quotas, and multiple exchange rates to avoid waste in currency-leaking sectors and to channel resources into the right direction. Export-oriented commodity sectors, like agriculture or mining, would have to be “squeezed” to subsize import-substituting manufacturing, and to sustain the high exchange rate and wage levels favoring domestic consumption (Bruton, 1998, p. 914). On the other, Prebisch and others saw the saving rate of an economy as a function of the “patience” of high-saving actors, such as the public sector as well as economic elites and middle-class sectors, to accept limits to their accumulation and to divert resources into long-horizon investments (ECLAC, 2008, p. 30). Therefore, until E could catch up with S, the state would have to discipline certain sectors, particularly the more affluent and with excess resources, to deter “certain types of consumption which are often incompatible with intensive capitalization” (Prebisch, 1962, p. 3).

While ISI initially led to an “exuberant phase,” with the manufacturing sector in some Latin American countries growing to match in size that in industrialized economies, soon enough this model introduced a number of distortions in the economy that complicated the progress of this agenda and its “interrelation with social and political life” (Hirschman, 1968, p. 1). First, depending on small and captive domestic markets, ISI industries became highly rent-seeking, enjoying abnormally high profit rates that deterred investment and outward expansion.7 Second, expansive wage policies not only added pressure to the real exchange rate, but produced inflationary tensions if domestic bottlenecks could not catch up with the captive and subsidized demand, adding to salary demands while increasing the appeal of “cheaper” foreign products. Third, the ISI model did not break with the external constraint: not only as local industry, transport, and telecommunications sectors remained import-intensive, demanding foreign currency for royalties, licenses, remittances of profits, and for intermediate and capital goods necessary to upgrade local capabilities, but because exports were still necessary to cover foreign currency needs in society, which increased as it became wealthier. This resulted in a vicious cycle, both in economic and political terms. On the one side, the hard currency revenues from a discouraged exporting sector were used to sustain an inefficient industrial sector growing “cozily at home” and reluctant to invest in an export drive, and which pressured governments to sustain trade protections (Hirschman, 1968; Bulmer-Thomas, 2003, p. 26).8 On the other, governments had to decide how much social and political costs they were willing to pay for restricting the consumption demands of richer sectors, in societies that were more affluent and less authoritarian than for example, Cold-War South East Asian countries.

As a result, from the sixties onwards Latin American ISI economies started suffering BoP problems and stop-and-go cycles that confronted governments with governance puzzles and major political risks: devaluing the currency (and hurting wages and the viability of the ISI model), restricting imports (and creating supply bottlenecks that tightened supply and accelerated inflation), increasing taxes on exporters, and/or taking debt. Facing dual pressures from a labor-industrial bloc that benefited from the overvalued exchange rate, state protections, and high salaries, and from export-oriented rural sectors and elites, historically influential and often in command of those sectors providing foreign currency, most governments resorted to a combination of import restrictions and heavy borrowing, with the stock of public debt ballooning from 7 USD to 314 USD billion between 1960 and 1982 (Bulmer-Thomas, 2003, p. 352; Edwards, 1995, p. 17).9 This shift to “debt-led growth” aggravated economic vulnerabilities and distributive tensions, as governments now had to find ways to finance debt commitments in addition to the fiscal and monetary imbalances that resulted from their incomplete ISI model. When the global context soured in the seventies, this enhanced vulnerability led to debt crises and multiple-digit inflation across the region, and to increased social turmoil (Pastor, 1989; Felix, 1990). In a Cold War context marked by the presence of revolutionary far-left movements, in countries like Argentina, Uruguay, and Chile, for instance, distributive tensions were directed against the welfare-providing state, contributing to an atmosphere of generalized social upheaval that resulted in the collapse of democratic governments, and the arrival of authoritarian regimes that sought to impose market discipline through violence (Edwards, 1995).

However, neither economic stability nor distributive peace were restored with the return of democracy, with high inflation (averaging 1,500% by late 1980s) and BoP restrictions turning into damaging fiscal and debt crises, as weak democratic administrations scrambled for resources to service their debts, with most countries in the region in arrears by 1989 (Felix, 1990; Remmer, 1993, p. 394). Again, forced adjustment came through dramatic currency devaluations and sharp contractions of economic activity, with per capita income declining 10% during the decade. This recurrent cycle of deepening crisis eroded the legitimacy of the democratic governments, which in many cases aggravated macroeconomic instability and political turbulence as they delayed imposing unpopular stabilization measures. In the nineties, this long crisis ultimately paved the way for the arrival of neoliberal administrations with greater space to introduce adjustment reforms that dismantled ISI regimes and their support base (Remmer, 1993; Schamis, 1999). Following Washington Consensus recipes on fiscal discipline and trade and financial liberalization, these projects enjoyed certain initial success, benefiting from the inflow of foreign investment and high liquidity in international financial markets, another opportunity window. However, as noted by Frenkel and Rapetti (2010), in those countries where stabilization programs proved unsuccessful (Argentina, Brazil, Mexico), capital inflow was used (again) to anchor a relatively high exchange rate that encouraged the surge of consumption and imports, which grew from 14% of GDP in 1989 to almost 20% by 2001, while exports stagnated (WITS, 2021). When the external constraint bit again, in that instance following the 1998 Russian crisis, those economies not able to generate enough foreign currency revenues experienced new BoP and debt crises—leading (Calvo and Talvi, 2005: 1) to start their analysis with the maxim: “Latin America does not grow.” Though Mexico and Brazil crashed first, in no place this bust was worse than in Argentina, resulting in 2001 in the (then) largest debt default in history, the fall of the government, and a near 300% devaluation of the currency that sent over half the population into poverty (Malamud, 2015).

This overview of the region’s troubled economic history brings nuance to the concerns outlined in the introduction. While many discussions about the politics of development tend to look at how the global economy and E condition domestic politics, we are interested in considering how political change in the region may also be shaped by the “the problem of S,” that is, intense distributive conflict and social expectations that pressure governments to deliver what their economies may not be able to sustain. Furthermore, it makes evident how this problem could be particularly complex when faced by left-wing administrations, as by definition they are inclined to prioritize S over E and come to power with a strong democratic mandate to do so.

Regarding the first issue, numerous observers have noted structural reasons for why Latin American countries seem to experience stronger distributive tensions than other developing economies. Enjoying political autonomy and rich natural resource endowments, Latin American nations went through processes of industrialization and urbanization earlier than South East Asia or Africa, resulting in “the growth of a wage-earning working class and a salaried middle class” and in higher standards of living, health, and social protection—in some cases like Argentina and Uruguay, above those enjoyed by Taiwan or South Korea by the early eighties (Bulmer-Thomas, 2003, p. 127).10 Moreover, contrary to the productivity-driven and labor-repressive model of Asian industrialization, in Latin America economic modernization was largely advanced by state-led corporatist regimes with a strong focus on ameliorative redistributive policies, promoting simultaneously the consolidation of the social welfare (and developmental) functions of the state and the political (and democratizing) incorporation of the working class into political life (Wade, 1992; Collier and Collier, 2002; Haggard and Kaufman, 2008).11 This early process of incorporation shaped lasting political cleavages and patterns of political competition, not only as it consolidated the role of trade unions as the main representative of labor but as it favored the formation of strong democratic linkages—in places like Uruguay, Colombia, Peru, and Argentina, taking the form of resilient party-labor alliances. However, this incorporation would remain incomplete and turn increasingly fractious during the second part of the 20th century, given that while democratic-oriented elites would be incentivized to bring distributive politics to the fore of political competition, military and conservative regimes would seek to discipline labor demands and social mobilization through authoritarian means (Haggard and Kaufman, 2008, pp. 48–49). Argentina again is perhaps one of the most striking examples of this pattern of confrontation, with Guillermo O’Donnell (1972) referring to it as “the impossible game,” as civilians governments struggled between conceding to labor demands and risking a military coup, or imposing fiscal austerity and facing popular opposition and labor unrest.12

The lure of the populist dilemma would only intensify as these regimes democratized, given that conservative parties would find it increasingly difficult to defend their interests without granting concessions that “ward off the rise of labor-based populist and leftist competitors who invariably politicized socioeconomic inequalities” – except in some countries such as Chile, Paraguay, and Colombia, where authoritarian rule and political repression had significantly constrained the mobilization of popular sectors (Roberts, 2014, p. 30; Teichman, 2008).13 Distributive strife was further complicated under neoliberalism. As noted in (Luna and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2014, p. 362), not only the opening of national economies contributed to the emergence of consumption-based interests across all income groups, and to a lasting “enthusiasm about having low inflation and access to imported goods,” but countries became even more vulnerable to global economic swings and the influence of global financial markets and transnational business in domestic policy (Bartell and Payne, 1995; Schneider, 2004). A range of authors thus point to the volatile mix of market liberalization, democratic transition, and adverse global conditions as the main cause behind the “brand dilution” and programmatic dealignment party politics suffered through the eighties and nineties, as incumbents “proved unable to fulfil the high—and frequently excessive—hopes engendered during the transition to democracy,” while trying to maintain attractive conditions for foreign capital (Weyland, 2004, p. 148; Roberts, 2012; Lupu, 2014). Combined with economic turmoil, this political crisis was conducive to the re-activation of popular discontent and the growing appeal of “radical, extrasystemic populist and leftist alternatives” that mobilized distributive conflict and programmatic contestation against economic orthodoxy (Roberts, 2012, p. 1447).

Here we can move to the second issue, considering that, insofar as the leftist governments of the early 2000s brought forward a revitalized program of political incorporation that sought to integrate the demands of popular, poor, indigenous, and other disenfranchised sectors, they could be expected to face a more volatile political economy of distributive conflict. This is because during this second incorporation collective democratic rights were advanced not only by state-led corporatist links but by promoting “social citizenship […], mechanisms of direct participatory democracy, and social inclusion,” embracing social movement alliances and policies extending “basic social rights to groups that had been disincorporated or marginalized under neoliberalism” (Silva and Rossi, 2018, pp. 9–10; Rice, 2012; Rossi, 2015). This enhanced social vision invested these administrations with substantial democratic legitimacy. But it also exposed them to more intense distributive pressures as 1) the exceptional improvement of economic and social conditions during the boom legitimized leftist discourses and participatory models of state-society linkage, while eroding the authority of technocratic governance (Levitsky and Roberts, 2011; Philip and Panizza, 2011), and 2) these commitments required increased fiscal spending, involving more or less aggressive wealth-appropriation and transfer mechanisms that produced fiscal legitimation problems (Von Haldenwang, 2008; Barlow and Peña, 2021).

These pressures could only be expected to increase if global economic conditions were to deteriorate, as these governments would have strong incentives to assure the electoral survival of their agendas by defending their achievements in terms of S. Different strategies could be deployed for this purpose. For example, more radical governments could resort to institution-capturing strategies, as in the case of Venezuela, including the nationalization of high-rent sectors and the erosion of democratic institutions (Mazzuca, 2013; Chesterli and Roberti, 2018). More moderate ones, we claim, could try to combine macroeconomic and political forms of populism, in different degrees, sustaining welfare and fiscal commitments while relaying on the affective narrative of populism to mobilize clientelist and plebiscitarian linkages with civil society, and to shift the burden for economic disequilibria to opposition groups and egoist elites (Roberts, 2006; Ostiguy, 2017) – something particularly effective in societies with high inequality and where segmented labor markets set divergent preferences for those in formal and informal employment (Doner and Schneider, 2016, p. 625). The danger of this latter strategy is the aggravation of both distributive conflict, as E is stretched while the expectations behind S are raised for an important portion of the population, and of political polarization, as these commitments and their costs would be segmented against higher income groups (Luna, 2014).

In this sense, we do not consider that populist strategies are pre-destined to fail, nor intend to evaluate the economic effectiveness and suitability of specific policies (though we acknowledge some are more problematic than others). Rather, we approach populism as a political solution serving to enforce political authority and structure relations of participation and support, thus helping to navigate the eventual misalignment of macroeconomic conditions and distributive demands and expectations (Weyland, 2017, p. 56). In the case of the more inclusionary Latin American leftist variant, this solution draws on a general narrative—and accompanying policy preferences—that combine a socio-political aspect with a socio-economic one (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2013).14 The first is the well-known plebeian script centered around “the people” and what Ostiguy (2017, p. 73) calls the “flaunting of the low,” which seeks to re-institutionalize social conflict around more direct channels of representation between the state (and/or its leader) and the citizenship. The second is a strong emphasis on economic redistribution, public spending, and the mediator role of the state; in Latin America generally associated with a myth of industrialization around ISI, “the association of ISI with people’s welfare, national development and a bright future” (Grigera, 2017, p. 445).15 Accordingly, from our point of view populist strategies could work, for example, if global opportunity conditions were to recover soon, enabling to correct the negative externalities of macroeconomic populism (i.e. inflation, deficit finance, currency devaluation), or if the government succeeds in building popular alliances strong enough to deflect opposition or elite challenges (Anria, 2013). However, as we argue ahead, the CFK government in Argentina provides an explicit example of the economic and political risks this strategy carries if this does not happen and the strategy is deepened, and of the problems this can generate in the longer term.

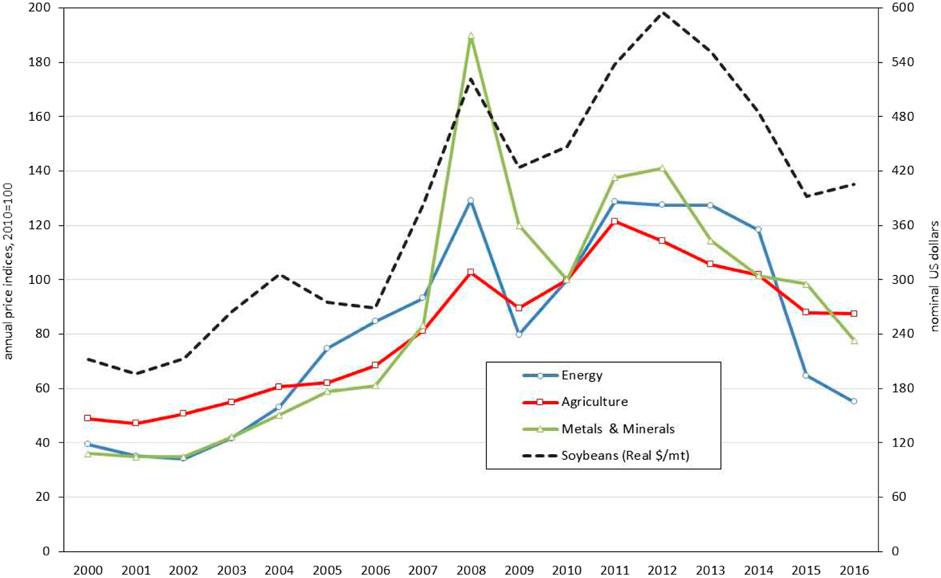

As shown in Figure 1 below, the commodities boom started around 2003 and lasted for roughly a decade, with international prices falling sharply from 2013 onwards. Moreover, until the 2008 global crisis, this boom coincided with additional positive conditions as low growth and interest rates in core economies favored FDI flows and access to cheap external financing (Jenkins, 2011; Ocampo, 2017).16 Combined with successful debt-reduction programs, the improvement of global terms of trade had an immediate effect on the economies of large Latin American countries, with the region as a whole enjoying an exceptional period of growth and progress (see Figure 2). This involved (very) unusual current account surpluses that enabled many countries to appreciate their exchange rates and accumulate foreign currency reserves, lowering the risk of the external constraint, while extraordinary commodity rents captured through export taxes and royalty schemes supported healthy fiscal surpluses while fiscal spending and pro-cyclical income and welfare policies expanded (Ocampo, 2008).17 As a result, between 2002 and 2012, per capita household incomes rose above 40% in most large economies (78% in post-crisis Argentina, for example), poverty was halved, and inequality levels showed an unprecedented reduction (with the regional Gini coefficient improving 8%) (Heidrich and Tussie, 2009; Amarante et al., 2016). Moreover, optimistic readings of the “twin surpluses” led to questionings of the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis and comparisons with the early take-off phase of Southeast Asian economies during the eighties. Unsurprisingly, coming out from the grim austerity of the neoliberal years, most administrations “were able to score quick wins with regards to welfare” that cemented their popularity, with many leaderships such as Hugo Chávez and Lula da Silva becoming era-defining figures, domestically and worldwide (Philip and Panizza, 2011; Grugel and Riggirozzi, 2012, p. 8).

FIGURE 1. The Commodities Boom in Latin America and Argentina, Source: World Bank Commodity Price Data.

As shown in the graphs below, Argentina followed this regional trend, albeit the country benefited less from FDI inflows and access to international debt markets given unresolved creditor liabilities following the IMF sovereign debt default of 2001 (Gallo et al., 2006). Moreover, the Argentine post-crisis period was characterized by policies implemented to ameliorate the impact of post-default measures, in light of the dramatic effect the devaluation of the peso had over living conditions (see Table 1). The urgency of the situation coupled with reduced options to borrow meant that Argentina turned to tax as a solution: while the collapse of income and employment limited the application of direct taxes, the transitional Duhalde government implemented a program of emergency taxation targeting agricultural exports, which comprised roughly 60% of Argentina’s total exports (mainly soy, corn, and wheat, among others) (Barlow and Peña, 2021). These emergency taxes, which already in 2002 provided nearly a quarter of the total fiscal intake, would become one of the main pillars of the economic recovery and a fundamental piece in the developmental model promoted by Néstor Kirchner and CFK (Grugel and Riggirozzi, 2007; Wylde, 2012). Moreover, this fiscal strategy would be reinforced by the gradual but constant improvement of agricultural commodities prices—as shown in Table 1, the fiscal intake expanded from 19.3% of GDP in 2001 to 27.6% in 2008 and public spending grew by 7.3% of GDP, reaching a level unseen in over three decades (MECON, 2021).

The improved terms of trade due to rising export prices, and the competitivity gains (and collapse of imports) brought about by the currency devaluation (see the evolution of multilateral real exchange rate in Table 1) created a major macroeconomic space for moderating distributive conflict.18 In particularly, it allowed the Kirchner governments to adopt expansive wage and welfare policies as consumption and economic activity recovered, deactivating conflicts with both labor and business: rural producers for example, moderated their historical opposition to export taxes, while trade unions re-directed their grievances from the state and jobs to business and wages, as the government restored labor protections, raised the minimum wage, and encouraged collective bargaining (Manzetti, 1992; Etchemendy and Collier, 2007, p. 372, p. 610). This space facilitated the government’s political agenda, sterilizing the opposition and guaranteeing electoral success; so that when Néstor Kirchner decided not seek re-election, leaving office with approval ratings above 50%, he left behind a consolidated support base that assured the continuation of the Kirchnerist project and the smooth election of his wife in October 2007 (Levitsky and Murillo, 2008).

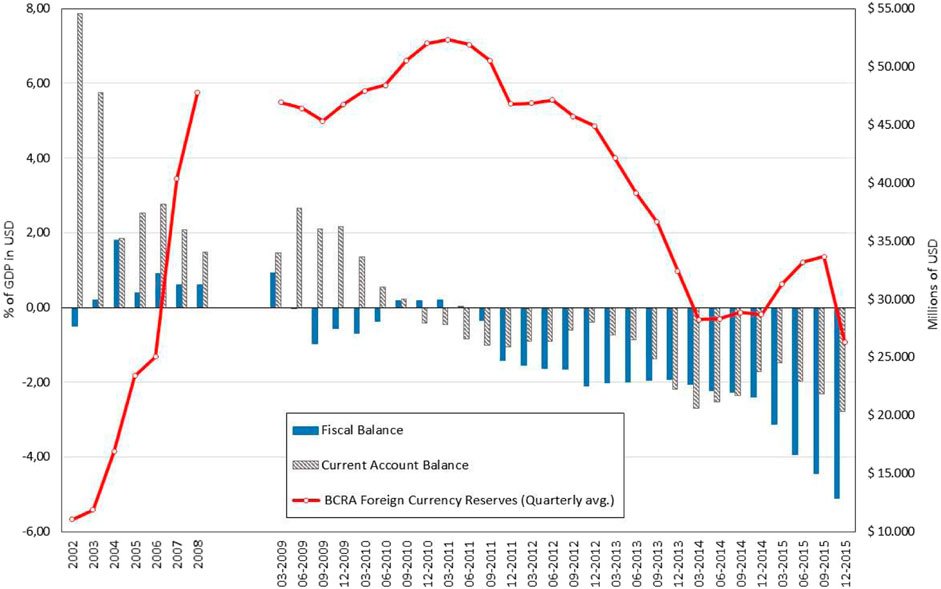

It was not until this second period that the fragile truce over redistribution started to crack, when an attempt to implement a new tax hike on agricultural exports in 2008 was the catalyst for widespread protests as the rural sector revolted, leading to a 4-month lockout of Buenos Aires city and a hurtful defeat of the bill in Congress (Hora, 2010; Fairfield, 2011). As explained ahead, while this setback did not deter the new president from deepening her political agenda, it affected two factors that would eventually condition its economic and political evolution. First, it set a limit on the government’s fiscal model, making it more dependent of international commodity prices to obtain additional revenues. Second, the rural conflict aggravated political polarization around distributive cleavages, becoming a watershed moment in cementing the divide between Kirchnerist and anti-Kirchnerist positions, shattering the emergency consensus of the post-crisis years about the priority of emergency policies (Barlow and Peña, 2021). In this context, the Great Recession of 2009, which briefly interrupted the upward trend of global commodity prices, offered a first glimpse of the economic dangers that lingered behind the social and political commitments of Kirchnerism: as shown in Figure 3, as global prices and demand dipped, the CFK government continued increasing public spending to a record 37.6% of GDP, leading to the first fiscal deficit of the post-crisis era.

FIGURE 3. Internal and External Accounts versus Foreign Currency Reserves, Source: ECLAC - CEPALSTAT, OECD, BCRA.

It is in the 2010–2011 period that we can identify the moment when the populist temptation came into effect, as it was then that key political decisions were made that explicitly privileged the political benefits of sustaining S over the stability of E. However, at first glance, the impact of this strategy was not readily evident: following the slump of 2009, Chinese and global demand recovered and so did agricultural commodity prices, facilitating the return to strong growth (see Figures 1, 2). However, as shown in Figure 3 below, 2010 was the first year when the current and fiscal accounts went into deficit together since 2002, an indication that the twin surpluses that so far had kept distributive demands at bay were being depleted.

This early deterioration of external and internal accounts can be attributed to the decision to assure the president’s re-election in 2011, something not trivial considering that the ruling party, the FPV, had lost votes in the 2009 Congressional elections.19 To do so, the government abandoned previous plans to devalue the currency and lower subsidies and engaged into what Bresser Pereira (2009) called “exchange rate populism,” using an overvalued exchange rate to subsidize consumption—endorsing salary and pension increases above the rate of devaluation of the currency that increased income in real terms and stimulated economic activity (Tagina and Varetto, 2013, p. 10).20 To put this in perspective, the impact of this measure was such that the average hourly wage (in dollar terms) tripled that of Mexico, was 50% higher than in Eastern European middle-income countries, and was roughly on parity level with that of the Asian “new tiger” economies (De la Torre et al., 2013, p. 47). This strategy paid off, and the 2011 elections took place under a “consumption and activity boom” that enabled CFK to be re-elected with a record 54% of the votes, defeating the runner-up by the largest margin since Perón’s victory in 1946 (Gerchunoff and Llach, 2018). Diverse academic observers read this triumph as a clear sign of the support that the Kirchners had amassed, with the middle-class rewarding them for the quick post-crisis recovery and popular sectors for generous welfare policies and wage and pension increases (Calvo and Murillo, 2012, p. 151). The government, as we expand ahead, will see in the victory a democratic mandate to deepen its political strategy.

However, the decision to appreciate the real exchange rate brought forward extant vulnerabilities in the Argentine economy. First, the “cheap dollar” weakened the trade account balance, not only as people demanded more imported products but because the economy had not shed its dependent character: on the contrary, the country’s economic matrix presented a clear “structural duality” where a few sectors linked with commodity-based manufacturing enjoyed a positive trade account while the remaining industrial sectors were dependent on foreign imports, particularly those that had modernized and/or become integrated in global supply chains (Schorr and Wainer, 2015, p. 41). Hence, an overvalued exchange rate not only damaged the competitiveness of industrial sectors, but the government employment-focused model had promoted the local manufacturing of certain popular consumer goods, such as electronics and cars, that had a significant proportion of foreign-made components that could not be easily substituted. As a result, as the economy grew the industrial manufacturing sector consolidated a negative trade balance position, reaching a deficit of USD 9 billion by 2013 (Ibid., p. 39).

The current account was also affected by the government’s welfare commitments, particularly by consumer subsidy programs in natural gas distribution and urban transport, which had made utility prices in Argentina roughly a third of what was paid in other Latin American countries (Moffett et al., 2012).21 A tariff freeze in place since 2002 and higher operating costs due to wage improvements made the operation of these sectors heavily dependent on state transfers, with subsidies going from around 2.4% of GDP in 2006 to 4.5% in 2010, as shown in Figure 4 below (Bril-Mascarenhas and Post, 2015, p. 109; Damill et al., 2015, p. 13).22 Moreover, the tariff freeze had paralyzed investment in the energy sector, so that by 2011 the country had become a net importer of oil and gas, while the quality of services and infrastructure deteriorated. This burden would balloon in the next few years, with the cost of importing energy alone reaching USD 8 billion in 2014, representing a quarter of the Central Bank’s foreign currency reserves at the time.

The populist strategy also hurt the fiscal balance, as public spending continued rising as tax revenues suffered a slowdown (see Table 1). As explained by Gerchunoff and Kacef (2016), given that most of the excess in public spending was destined to finance the celebrated expansion of pension coverage, cash-transfer schemes, and the mentioned transport and energy subsidies, welfare commitments tied the government into an ever-growing spending cycle—as double-digit inflation meant revenues from peso-denominated tariffs fell while demands for wages and subsidy adjustments increased.

The deal with these distortions the government turned to its own resources, as opportunities to further tax agricultural exports were closed and the country was excluded from international financial markets. This meant implementing a series of measures that, while granting the government greater policy autonomy, generated problematic macroeconomic and political dynamics. Hence, to sustain the value of the currency, the government started selling its reserves, ending a pattern of accumulation started in 2003 that reached a maximum of 52 billion dollars in January 2011. At the same time, the government used monetary emission to finance spending, with the Argentine Central Bank (BCRA) extending non-backed credits to the Treasury. To facilitate this, in March 2012 the government reformed the BCRA’s charter—extending its mandate from monetary stability to a broader and more progressive mission that included the promotion of “ […] employment, and economic development with social equality” (quoted in Damill et al., 2015, p. 23). This move away from neoliberal orthodoxy granted the executive the capacity to determine the use of currency reserves and to set the level of indebtedness of the Central Bank, while giving it free hand to intervene in monetary policy.23

Some of the traditional problems of the ISI model quickly returned. To regulate the outflow of hard currency and discipline dollar-spending sectors capital controls were implemented, with the government curbing imports, blocking the repatriation of capital by foreign companies, and limiting the amount of foreign currency citizens and institutions could purchase, restrictions that were tightened seven times in 2012 alone. However, as the majority of imports were capital and intermediary goods, import restrictions disrupted transnational supply chains, creating bottlenecks that created inflationary pressures while impairing the operation of subsidiaries and import-dependent firms—leading the EU, the US, and Japan to present a demand to the WTO in 2012, which ruled favorably in early 2015 (Hughes, 2015).24 Relations with international business and investors further deteriorated when the government intervened in the “dollar-leaking” energy sector, deciding in May 2012 to expropriate the control package the Spanish energy holding REPSOL had in the oil company YPF, the largest oil and gas firm in the country, which had been privatized in the nineties. Given the strong presence this company retained in the national imaginary, this decision was considered an easy political win, with the bill celebrated as helping recover national assets sold during the neoliberal years and receiving endorsement by most opposition parties in Congress (Manzetti, 2016).25

At the same time, a dark currency market came into existence, generating a premium between the official and the “free-floating” exchange rate (known in Argentina as “dollar blue”). In an inflationary context, and in a highly “bi-monetary” culture where people are used to keep their savings in dollars, not only the blue rate started to serve as a reference for many economic activities, but the restrictions triggered a reinforcing cycle that drove the premium further upwards, as citizens would maximize the official allowance and the government would seek to tighten supply (Luzzi and Wilkis, 2019; Schiumerini and Steinberg, 2020). This rise in the premium, which would hit 100% by May 2013, altered incentives across the economy, as exporters would be tempted to under-invoice and delay sales, as they expected the premium to continue rising, while importers moved to anticipate buys in advance of the tightening of restrictions—driving up the demand (and price) for foreign currency. Additionally, currency restrictions generated important distributive grievances in the middle- and upper-class classes, not only as an immediate way of protecting their savings from inflation was blocked, but as the government discouraged dollar-consuming activities like outward tourism, with a credit card levy on purchases abroad implemented in late 2012—measures that were perceived as a differential tax rate (Schiumerini and Steinberg, 2020).

Looked from afar, the convenience of these decisions appears at best risky and at worst highly misguided. However, there is evidence suggesting that the administration saw this as a calculated gamble—after all, the global economy had recovered and growth had returned to core economies, with Figure 2 showing that Argentina’s terms of trade remained extremely favorable and better than the regional average. If commodity prices remained high, the damage to the trade and fiscal accounts could be later amended, and the overvaluation of the currency moderated through more gradual and less harmful corrections to the exchange rate—softening the impact on the citizenship. In that sense, Miguel Bein, an economic advisor close to the presidency considered that the wage increases of 2010–2011 could be seen as an “salary advance” to the population, allowing Kirchnerism to survive the global crisis unscathed (Infobae, 2015). At the same time, Kulfas (2016) indicates CFK did a political reading of initial economic disturbances, as destabilizing moves by business and financial actors groups, disregarding its macroeconomic source. The problem was that as this populist strategy was implemented and deepened, the global opportunity window finally closed, rapidly damaging macroeconomic stability while raising the stakes of distributive conflict.

Drawing from cognitive psychology, Weyland posed that in contexts of imperfect information, political actors often make decisions guided by cognitive shortcuts and heuristics, arguing that the leftist activism and radicalism in Latin America was conditioned by the size of windfall gains during the boom, which induced a “risk acceptance” bias among elites that macroeconomic constraints could be avoided (Weyland, 2009a; Weyland, 2009b). This idea is interesting to understand the behavior of the CFK government after the dramatic electoral success of 2011, as the triumph was followed by “a radicalization of the Kirchnerist elite’s discourse” and an euphoria among its supporters for the deepening of its interventionist and populist agenda (Natalucci, 2019, p. 75). While political polarization had augmented since the rural conflict of 2008, with the government adopting a class-based derogatory discourse against its opponents, after the 2011 elections CFK adopted a more radical populist stance that distinguished the Kirchnerist developmental project in revolutionary and epochal terms (Freytes and Niedzwiecki, 2016; Ostiguy and Schneider, 2016). However, the end of the commodities boom, with prices of agricultural commodities peaking around August 2012, and Brazil, Argentina’s main trade partner, going into recession, would mean that this more aggressive populist strategy would not be accompanied by supporting economic circumstances. As a result, this second period witnessed the reversal of the two conditions that had facilitated political governance until then, “an economically successful center-left government and an ideologically heterogenous and hopelessly uncoordinated opposition” (Lupu, 2016, p. 44).

The deepening of the CFK’s populist discourse not only alienated the opposition and middle classes, but placed the government in conflict with more centrist element of the Peronist party and with the labor wing of the movement. As a result, as economic controls and restrictions were rolled out, the level of political confrontation increased. In June 2012, the national trade union federation, the powerful and Peronist CGT, orchestrated the first general strike of the Kirchnerist era, complaining about that (generous) salary increases were lagging behind the inflation rate, followed by another large mobilization in November, which even counted with the participation of rural organizations (Tagina and Varetto, 2013). Nonetheless, the level of confrontation took a dramatic leap with the onset of a cycle of mass anti-government protests between September 2012 and April 2013, which saw millions of people mobilizing spontaneously across the country (Gold and Peña, 2019). Through this cycle, protesters agitated a number of political and economic grievances attributed to the Kirchnerist model of governance, from inflation, currency restrictions, high taxes, and falling salaries, to issues of corruption, growing authoritarianism, and the deteriorating quality of the public services. After an initial surprise, the government reacted with a very confrontational stance, with the president herself dismissing the protests as “cacerolazos de la abundancia” (pot bangers of abundance), promoting an antagonistic treatment of protesters as part of a conservative class historically opposed to social inclusion, labor rights, and inclusive industrialization—core components in the Peronist developmental narrative (Ferrero, 2017).

The discontent revealed by these protests, however, was fundamental to reconfigure the opposition landscape, as it reactivated anti-Peronist sectors around a discourse that opposed the populist statism of Kirchnerism with middle-class “liberal-republican” values and the return to stable economic rules and institutionalized forms of politics (Gold, 2019). Hence, shortly after the protests and preceding the legislative elections, the first half of 2013 saw the emergence of a non-Kirchnerist Peronist party, the Frente Renovador (led by CFK’s former chief of staff) and the rise in popularity of the conservative major of Buenos Aires Mauricio Macri and his party (PRO), which called for the defense of democratic institutions and a more orthodox ordering of the economy, agitating a moral panic against the potential “Venezuela-isation” of the country (Morresi and Vommaro, 2014). As this happened, the deterioration of current and fiscal accounts, the new controls, and the continuous drop in foreign reserves, as shown in Figure 3, created additional expectations about an impending correction to the exchange rate, and/or the introduction of further economic restrictions—further incentivizing capital flight and demand for dollars.

The deteriorating macroeconomic landscape confronted the government with the urgency of adopting corrective policies, which in one way or another would aggravate distributive conflict and political polarization. For example, it could recompose the fiscal deficit by placing additional taxes on agricultural exports, but in a context of falling global prices and demand, this would not only require a significant tax hike but having to deal with an assured sectoral revolt, something it lacked the political capital to manage.26 It could transfer some of the costs of the adjustment to different segments of the population, for example, rising direct taxes, lowering subsidies, and/or devaluing the currency (or all together), measures that would worsen discontent in a citizenship that for over a decade had got used to exchange rate populism and what journalist Carlos Pagni (2013) denominated the “energy demagogy” of Kirchnerism (shown clearly in Figure 4). More importantly, political times became even tighter when the ruling coalition suffered a major defeat in the 2013 congressional elections, losing three million votes and immediately raising concerns about the survival of the Kirchnerist project in 2015. With limited options, the government decided to sacrifice some of its social and ideological commitments in order to avert a full BoP crisis—with foreign currency reserves hitting USD 26.7 billion in March 2014, dangerously close to the level in the months preceding the 2001 default. Thus, while tightening currency controls, in January 2014 the government accepted devaluing the peso by 30% (the first major correction in 11 years), at the same time that it hiked interest rates and increased energy and transport tariffs, measures that pro-government sectors saw as a political defeat in the hand of conservative and neoliberal sectors (Zaiat, 2015; Kulfas, 2016). Secondly, it rapidly moved to normalize relations with financial markets, something not easy after years of clashes with foreign lenders and international financial organizations. This involved settling three standing issues; a dispute with REPSOL about the expropriation of YPF (for a cost of USD 5 billion), a USD 9.7 billion debt with the Paris Club, a group of creditor nations seeking compensation for the 2001 default, and litigations with holdout creditors who had rejected the debt restructuring of 2005 and 2010 (Mander, 2014; Thomas and Marsh, 2014). Despite this involved sacrificing precious currency reserves, the government decided to pay the costs, hoping to compensate through debt what it could not anymore obtain from commodity prices. However, unforeseen external circumstances derailed the whole strategy when a New York judge dictated that prior to paying to holdout creditors, Argentina needed to pay USD 1.6 billion to a “vulture fund” holding defaulted bonds from 2001. When the CFK government refused, fearing this would reopen settled claims with other bondholders, the country entered into “selective” default on July 2014, shattering any hope of a quick return to financial markets, rocketing the country’s financial risk premium, and fueling a sense of impending crisis that neutered the politically harmful macroeconomic relief brought about by the currency devaluation (Cantamutto and Ozarow, 2016).

By 2015, the administration was fully trapped between the external constraint and policy traps of its own making but whose removal would complicate winning the elections. In these circumstances, the populist strategy entered what we can call its terminal electoral phase, delaying harsher adjustment measures until after the elections while agitating electorally the memory of the earlier expansive phase. This delay, however, involved sustaining public spending as the economy contracted, meaning the fiscal deficit jumped from 1.9% of GDP by late 2013 to 5.1% by late 2015—exceeding all the combined revenues from export taxes (Damill et al., 2015; Gerchunoff and Kacef, 2016). As this excess fiscal effort could only be covered through currency emission, and with the external constraint then in full swing as international prices continued falling, the government became entangled in a Sisyphean task where the more it defended its support base, the more money it had to print, the more foreign currency reserves it lost, and the greater devaluation and inflationary expectations became—paralyzing the economy and deepening the sense of impending crisis.27 As noted by Lupu (2016), by the time the elections arrived in December 2015, voters were left to choose between continuity or change. Change preferences prevailed, particularly in Buenos Aires and the more affluent urban areas whose inhabitants had been politically alienated by the Kirchnerist narrative, resulting in the victory of Mauricio Macri by a slight margin. Upon arrival, the Macri administration quickly abandoned the core policies of the Kirchnerist model: currency controls were removed and the peso was devalued to match the unofficial dollar rate, import and capital controls were relaxed, exports taxes were reduced while utility prices were (dramatically) hiked, and the country returned to sovereign debt markets, issuing USD 16.5 billion in bonds. Central to the new government’s vision was reaching 2019 with “zero [fiscal] deficit,” signaling financial markets and foreign investors its commitment to a more responsible macroeconomic policy, away from populist temptations.

The defeat of Kirchnerism after over a decade of hegemony evidences the governance puzzle faced by reformist democratic administrations in depending economies, be these left-wing or not, and more or less populist: how to survive politically and navigate between the Scylla of distributive conflict and the Charybdis of political priorities on the changing winds of the global economy? What our article highlights is that this governance challenge may be harder than it seems, as in the near term governments can take a number of measures to move closer to or away from E, but there is little they can do to control the social demands and expectations sustaining S, not without paying high political and electoral costs. Populism, we claim, emerges as a pragmatic strategy to manage this problem, but one that carries a variety of risks, such as increasing political polarization and troublesome economic and political entrapments where the previous “success” becomes the bar to measure current shortcomings. And here lies the danger for democratic developmental regimes, insofar as their inclusive policies may raise social and political expectations—generating new experiences of political inclusion and economic mobility, and new memories of progress—faster than they can upgrade the structural conditions materially guaranteeing these expectations. In Argentina, for example, the investment rate in the economy by 2016 remained on a similar level to 2004, with (Wainer, 2018, p. 330) noting than the model of growth with social inclusion of Kirchnerism was also a model of “growth without structural reforms.” Ironically, the same temptation that affected CFK would affect the conservative Macri government, which immediately after taking office faced intense opposition from trade unions, social movements, and discontented citizens, aggrieved by abrupt hikes in energy and public services, fiscal austerity, and by the harsh deterioration of income power the removal of currency controls (Niedzwiecki and Pribble, 2017, p. 89). While exploring this is beyond the scope of this article, social pressures also pushed this administration to moderate its normalization agenda and to implement policies that prioritized S over E, ultimately resulting in a debt crisis and the government’s electoral defeat in 2019, after yet another painful devaluation of the currency. In this sense, we could say that Argentine voters punished CFK, as they would punish Macri 4 years later, not because she went in the direction of macroeconomic populism, but because she failed to maintain the conditions behind the macroeconomic point of social equilibrium: the expectations much of society had in terms of how much to earn, what to consume, and how much to pay for what it consumes.

Interestingly, other countries in the region appear to manage distributive conflict with less contention than Argentina. As put by Natanson (2018: 30), this may be because they either have enough export resources to avoid the external constraint (or can capture excess rents with less confrontation, as in Chile or Bolivia) and/or because they have societies ‘with less “European” consumption patterns’ that limits the needs for imports, and other associated implications in terms of value of the currency and access to external markets. There is support for this idea in economic evidence: while since liberalization the income elasticity of demand for imports across the region has grown, in Argentina it remains consistently high and above the level of countries like Chile, Uruguay, Brazil, and others, showing a pronounced tendency for domestic consumption and rates of saving well below those found in equivalent emerging markets (Pacheco-López and Thirlwall, 2006). More importantly, this line of thinking suggests a number of hypotheses and analytical expectations deeming further elaboration and inquiry. Mainly, if the lure of the populist temptation is dependent on where S is located, this means that some countries may confront less intensive political pressures to deliver income and consumption standards above macroeconomic possibilities. On the one hand, this would mean that Argentina’s instability could not just be a consequence of poor policy-making and weak institutions, but the outcome of historical particularities in Argentine development and political evolution: a past of wealth and welfare shaping lasting social imaginaries and political utopias, but also a long experience of economic crises and inflation that promotes immediate consumption, capital flight, and the dollarization of the economy (which is another form of “importing” a foreign asset). On the other, we could explore whether less affluent countries with less developed welfare states, like Bolivia, Paraguay and Peru (until recently at least), have societies more “tolerant” of distributive inequalities, and can thus maintain macroeconomic and political continuity with less conflict. An interesting caveat of this idea would be that rapid dislocations in the location of either E or S could augurate political change dynamics. Indeed, several developments in the region could be investigated from this angle, as the end of the commodities boom saw major political and social conflict erupt in two countries with a limited history of social mobilization under democracy: Brazil and Chile. In the case of the former, it has been argued that the unprecedented improvement of S during the Lula years turned into anti-PT grievances once the bonanza subsided, resulting in a dramatic shift to the (far) right (Alonso and Mische, 2017). Chile, the most successful economy in the region, suggests an alternative trajectory of political change were the improvement of S lagged behind the improvement of E, with the mass revolts of 2019–2020 revealing the extent of social discontent with the neoliberal governance model inherited from the Pinochet dictatorship (Somma et al., 2020).

Simultaneously, if structural distributive conflict is seriously considered, we could also pose that the success and failure of different governance models and policies could be better assessed not on the basis of how much they raise S when global opportunity conditions are favorable, but on whether they contribute to improve political capacities to manage distributive tensions when these become absent. In the case of Argentina and Kirchnerism, this assessment would not be positive: while managing to avoid a full-blown economic crisis, CFK left behind a stagnated and disbalanced economy and a politically polarized society with open distributive wounds and fewer political resources to deal with them—complicating the governance challenge of her successors, who to this day have failed to revert a decade-long pattern of stagflation and populist polarization.

Lastly, some observers have noted that contemporary globalization may augurate problems for the quality of democratic politics in the region. This is because as a result of global structural and technological changes, Latin American economies are experiencing what (Rodrik, 2016, p. 29) called “premature de-industrialization,” where the weight of industry and services in the economy approximates the level found in developed ones but without the latter’s productivity and income gains, resulting in more segmented and unequal labor markets and growth models “driven largely by capital inflows, transfers, and commodity booms.” This configuration would aggravate distributive tensions and increase the appeal of populist strategies, leaving less space for building the “upgrading coalitions” facilitating inter-temporal cooperation and difficult institutional agreements (Doner and Schneider, 2016, p. 619; Kingstone, 2018, p. 148). If this were so, the region and its citizens, risk becoming even more entrapped between the turbulences of the global economy and increasingly ephemeral political times.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1While government accounting is a complex affair, with multiple standards, overlapping metrics, and different periods of reporting, dealing with Argentine macroeconomic statistics is particularly problematic. In the period at hand, the government’s intervention of the national statistics institute (INDEC) in 2007, resulted in a motion of censure by the IMF due to data tampering. After 2015, some official figures were corrected but discrepancies across different sources persist, so that reconstructing certain series may involve combining data from multiple sources.

2For a formal presentation of the model, see Gerchunoff and Rapetti (2016).

3While the factors configuring these points of equilibrium could suddenly change, for instance if a catastrophe or conflict destroys economic infrastructure or if an authoritarian regime squashes social rights, the authors reckon that E and S can be expected to change slowly, even if affected by contextual changes.