- 1University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- 2Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain

Why do political parties set an extreme or a more moderate position on the territorial dimension? Despite previous works have paid recent interest on the dynamics of the political competition on the territorial dimension, we know much less about the factors that lead to a centrifugal or a centripetal party competition on the same dimension. In this article, we offer a new way of understanding it: we argue that parties’ policy position on the decentralization continuum not only depends on the level of territorial decentralization, but also on the credibility of the institutional agreement established through the country’s constitutional rigidity. If the original territorial pact does not guarantee that the majority group will have its “hands tied” so that it does not reverse the territorial agreement, political parties will have incentives to adopt more extreme positions on the territorial dimension. We test this argument with a dataset covering around 460 political parties clustered in 28 European countries from 1999 to 2019 and by exploiting the fact that the 2008 economic crisis unleashed a shock on the territorial design. Our results confirm our expectations. We show that both the federal deal and the credibility of the institutional arrangement through constitutional rigidity are necessary conditions to appease parties’ demands on the territorial dimension. Our results have important implications for our understanding of how institutions shape political competition along the territorial dimension.

1 Introduction

Under what conditions political parties, regional and national, are in favour or against decentralization? Do institutions play a role in explaining why some regional and national political parties often set a policy position on the extreme of the territorial continuum, and others set a more moderate one? The conditions under which a country’s institutional design affects the behaviour of regional parties’ has been a traditional topic in the political science literature. Over the last decades, the field has spent a great amount of energy in understanding whether, and to what direction, state-wide or regional political parties polarize or converge on the traditional left-right dimension and what type of institutions trigger such dynamics. However, we know much less about what factors lead regional parties to adopt a more extreme or moderate position on the centralization-decentralization dimension–the territorial dimension. In this article we focus on the exploration of the joint effect of two key factors, namely the interplay between countries’ institutional characteristics and negative economic shocks.

This article aims at making a contribution to the literature on party competition by putting forward a new way of understanding why political parties decide to (de)emphasize their position on the territorial dimension. In a nutshell, our argument can be summarized in the following way: in contexts where a majority and a minority group coexist, the country’s institutions may be designed in different ways.1 For instance, a country can decide to distribute the power as much as possible (advanced federalism) or concentrate it on a single or a few poles (complete centralization). The particular form it takes is set in the territorial agreement (agreed by the parts or imposed by one/some of them). The territorial pact between the majority and the minority group can be framed as a commitment device that helps to tackle the commitment problem: on one hand, the majority group does not want to empty state institutions from governing capacity and, on the other, the minority group aim at acquiring a certain degree of self- and shared-government. Moreover, in our view, the minority group also seeks another important condition: the existence of a guarantee that devolved powers are going to be protected. In other words, the minority knows that any future change put forward by the majority group concerning the territorial design of the state might act against the minority’s group preference. If there are no guarantees, the ‘tyranny of the majority’ is likely to prevail (Abizadeh, 2021). In turn, the majority group wishes to reach a stable agreement that seals off territorial demands, especially any secessionist attempt.

In line with this logic, and if we want to understand party competition on the territorial dimension, our argument posits that we crucially need to consider two factors: first, the existence of a federal arrangement–a relatively large degree of self-government and shared-government–, and, second, the flexibility/rigidity of the constitutional design. Previous works have mainly considered that decentralization is enough to appease the need of some regional parties to compete over the territorial dimension. We complement this idea by arguing that both conditions are necessary: if the original territorial pact does not guarantee that the majority group will have its “hands tied”, political parties–regional and national–will still have incentives to adopt more extreme positions on the territorial dimension.

We test our argument by studying the position on the territorial dimension of state and regional parties over time and in different EU countries–and therefore different institutional realities. More precisely, our argument is examined by narrowing down our focus to how the 2008 financial crisis triggered different levels of territorial tension in different institutional contexts. Indeed, economic shocks to the system represent a strain to a country’s territorial organization. One of the reasons is that negative economic shocks accentuate the fragility (or robustness) of the existing institutional configurations, providing incentives to political parties to compete over different territorial configurations. Another one is that, under times of crisis, central-regional elites tend to blame each other for the economic situation and they often want to centralize/decentralize powers as a result. In other words, our empirical expectation is that, given the existence of a shock, in countries that have satisfactorily dealt with the territorial commitment problem (federal pact and constitutional rigidity), the political competition on the territorial dimension will tend to be a more moderate one. In contrast, in contexts where these two conditions are not present, the position of political parties on the territorial dimension will be more extreme.

Overall, this article offers a new way of understanding why parties compete over the territorial dimension by bringing together different approaches from the literature on political competition and the role of political institutions that have only been considered separately. Our analysis shows two key findings. First, political parties, and especially regional parties, adopt more extreme positions on the territorial decentralization dimension when negative economic shock occur and the institutional bases to canalize the commitment problem between the majority and the minority group are not satisfactorily settled. In other words, economic shocks seem to trigger a centrifugal dynamic on parties’ territorial dimension when the territorial commitment problem has not been satisfactorily channelled. However, if the institutional bases are such that the commitment problem has been largely channelled, economic shocks have the opposite effects, whereby moderating the territorial demands of regional parties and paving the way for a much more centripetal party competition on the territorial dimension. Second, our findings also show there are also important spillovers of the commitment problem on other relevant dimensions of party competition. Regional parties are also more likely to adopt more extreme positions on the nationalism and the immigration dimension when negative shocks take place and the institutional configuration has not been sealed in a way that satisfactorily deals with the commitment problem.

2 Theory

As the U.S. Founding Fathers observed, the relationship between the minority and the majority groups constitutes one of the pillars of the federal agreement and, ultimately, of the quality of the democratic systems (Coby, 2016). Previous research taking an institutionalist approach has extensively studied the dynamics of both the minority and the majority group under different institutional settings and national realities (Brubaker, 1994; Hechter and Okamoto, 2001; Garbaye, 2002). Similarly, early works in political science already strove to understand what type of institutional designs favour stable democracies, especially in societies deeply divided into distinct ethnic, religious, racial, or regional segments. For instance, in his seminal work, Lijphart (1999) noted that democracy in plural societies with segmental cleavages (consociational democracies) tend to have big coalitions, a large degree of federalism and mutual veto power. Under such systems, as the classical consociational explanation highlights, political parties tend to compromise, reach broad agreements and have little incentives to polarize their policy positions.

This dynamic is perhaps most evident when there is a concentrated minority group with different cultural traits than the majority one (Bednar, 2011). Under such a scenario, it is common to observe that the minority group will tend to seek a certain degree of political decentralization or even secession (Sorens, 2012; Sambanis and Milanovic, 2014). These demands will bring the State to a dilemma, the answer to which have varied across countries: while some countries facing territorial challenges have been more likely to decentralize as a way to appease these demands, others are hesitant towards such measures as they believe a greater autonomy does not necessarily decrease secessionist sentiment and may even increase some forms of territorial demands.2 In fact, political science has produced diverse findings as to what is the most optimal strategy to appease territorial demands (Lublin, 2012). All in all, both approaches converge in one important aspect: if the institutional design does not satisfactorily address the territorial demands, political parties will have incentives to use the territorial dimension–often known as the second dimension of political competition–for electoral purposes. Or, in other words, both stands assume that a certain degree of political decentralization is a necessary and sufficient condition to satisfactorily deal with territorial demands. The discussion in most works mainly revolve around the optimal degree of decentralization and the potential benefits or negative consequences it triggers.

As advanced before, our main contention is that the condition of a territorial agreement–the federal pact–is not sufficient to understand why in some contexts political parties have more extreme positions on the territorial dimension than in others. During the bargaining stage over the optimal level of decentralization, we contend that the notion of guarantee is a key component that gives credibility to the agreement. In fact, the interaction between the minority and the majority group can be understood as a commitment problem. These problems essentially derive from the inability of parties to write binding long-term contracts. In such situations, actors cannot achieve their goals because of an inability to make credible promises (or threats). In our case, the majority group wants to reach an agreement that makes the system stable and not subjected to continued negotiations over decentralization by the minority group. In turn, the minority group, besides an optimal level of decentralization, needs a guarantee that the majority group will not use its majority status to challenge or overturn the territorial agreement. If such guarantee does not exist, any change in preferences by the majority group–for instance, a new incumbent party with a pro-centralization position–may lead to a change in the territorial set-up against the will of the minority group. Closely related to this argument (Abizadeh, 2021), discusses and shows how under majoritarianism persistent minorities can suffer from unequal access to political power.

We argue that, only when both conditions are present, political parties will set moderate positions on the territorial dimension. If the level of self-government is high and the rigidity of the system is also high, both the majority and the minority group will have a commitment device that will eventually appease parties’ territorial demands. Using the classical concepts put forward by (Hirschman, 1970), when there is a relatively large degree of political autonomy and constitutional rigidity, both the minority group and the majority group are loyal to each other and exercise the “voice” within the confines of the system. If the territorial decentralization is not coupled with rigidity, or the system is rigid without territorial decentralization, political formations are more likely to “voice” their demands and even attempt to exercise the “exit” of the political system. In fact, secession can be understood as the last straw of the process: some groups may want to secede not only because they want higher levels of territorial decentralization, but because, given a certain degree of power granted to them, the system does not protect their political autonomy. Under such condition, they have power, but it is not clear whether they will be able to keep it. Ultimately, if the level of territorial decentralization is high, but the majority group–using its majority status–can over-rule it at any time, the outcome will be unstable and political parties will have incentives to have extreme positions on the territorial dimension.

Thus, our argument brings to the study of political competition in multi-level politics the notion of institutional rigidity. As previous works have highlighted, political competition in two-dimensional contexts is more complex than in uni-dimensional ones and political parties often use the second dimension of competition–the territorial one–as a tool to compete against their rivals and hence build electoral support (Sorens, 2009; Elias et al., 2015). To date the more general party competition literature has paid surprisingly little attention to the dynamics of the territorial dimension as a second dimension, despite its potential impact on party strategies and the consequences for patterns of party competition (Librecht et al., 2009; Elias, 2015; Massetti and Toubeau, 2020). Once again, up until now, it was assumed, often by default, that the level of political decentralization was generally sufficient in order to understand political parties position on the decentralization dimension. We complement existing explanations by bringing to the fore, together with the level of political decentralization in the original territorial pact, the need to theoretically consider the degree of flexibility/rigidity of the institutional structure in order to comprehend parties’ policy position on the territorial dimension.

The rigidity or flexibility of the constitution has been a prominent topic in the sub-field of comparative political institutions. According to Arend Lijphart, constitutional rigidity is one of a complex set of variables shaping the character and performance of different patterns of democracy, particularly the federal-unitary dimension (Lijphart, 1999). As put forward in Tsebeli’s work (2002), institutional design is a key factor that shapes party competition and political (in)stability, with both factors affecting each other. In a way, the rigidity or flexibility of the system can be understood as an underlying condition under which players (and potential veto players) interact (Tsebelis, 1995). Indeed, we know from previous research (Lutz, 1994) that the degree of constitutional rigidity is strongly associated with the frequency of constitutional changes that a country experiences.

Despite the causes and consequences of the rigidity/flexibility of the constitution have been studied before, their direct connection to party competition has only recently been highlighted. For instance, as developed by Sánchez-Cuenca (2010), the rigidity of a constitution is a crucial tool that can enhance the credibility of the original agreement–the initial territorial commitment. And, recently, using a veto player approach, Tsebelis (2021) has shown constitutional rigidity sets the ground for political competition over constitutional amendments, but also over other institutional aspects, such as the importance of judicial courts or other institutional features. Similarly, in a case study of several federal countries, Benz (2013) argues that the flexibility/rigidity of the constitution amendment process is a key aspect in balancing the interest of the federal vis-a-vis those of the regional governments. Thus, our empirical expectation is that political parties set a more moderate position on the territorial dimension under high federalism and high constitutional rigidity. Conversely, they will have more extreme positions when neither one of these two conditions is present.

If this logic explained above is correct, we should especially observe it in the presence of external economic shocks to the system. In other words, we argue that all else equal the interplay between constitutional rigidity and the level of federalism will unfold when a contextual shock reveals the limits of the system. This strain is most apparent in the event of an economic crisis. As shown by previous works, economic crises bring about a shock to the system in many domains. For instance, institutions need to decide, under situations of economic scarcity, whether to change territorial distributive mechanisms and how to tackle the likely increase in inter-regional inequality (Beramendi and Rogers, 2020). Or, in some contexts, and in order to receive support or extra funding, regional governments have been forced to accept significant cuts and greater control or supervision of their budgets (Pino and Pavolini, 2015). As shown by Beramendi and Rogers, (2020), decentralization mediates the link between redistributive effort and inequality, with potential effects on the political system. In addition, economic crises are often associated with a destabilizing effect of the party system and the salience of the territorial dimension often increases (Hernandez and Kriesi, 2016; Kyvelou and Marava, 2017; Hutter et al., 2018; Rodon, 2020). Thus, economic shocks can also provide incentives to political parties to move to the extreme their position on the territorial dimension (Amat, 2012; Basta, 2017; Rodon, 2020). Hence, when an economic crisis occurs, the territorial model is very often put into question for both parties and voters (Kyvelou and Marava, 2017; Wibbels, 2000; Bolgherini, 2014). As the Covid pandemic has illustrated (Kettl, 2020), crises increase the salience of many territorial questions, such as whether all territories are contributing equally to the common budget or even common effort in terms of restrictions, how the decisions should be taken or whether the current territorial model enables institutions to take effective decisions. Therefore, it is particularly in times of economic crisis when we should observe that parties in countries that have not satisfactorily dealt with the territorial debate–both in terms of a federal arrangement and constitutional rigidity–are more polarized along the territorial dimension. Specifically, we expect that regional parties should be especially prone to adopt more extreme positions in times of negative economic shocks when the institutional configuration does not solve the commitment problem between the majority and the minority group. Formally, we can specify our main hypotheses in the following way:

Hypothesis 1:

Economic shocks should trigger regional political parties demands’ for political decentralization when the commitment problem is not institutionally channeled.

Hypothesis 2:

Economic shocks should appease regional parties demands’ for political decentralization when the commitment problem is sealed.

3 Data

To test our theoretical expectations, we compiled a new dataset from different sources. This dataset identifies political parties’ position on the decentralization dimension, together with other party-level characteristics. In addition, we complement this information with country-level information on the other important concepts, namely a country’s level of federalism and the rigidity/flexibility of its constitution.

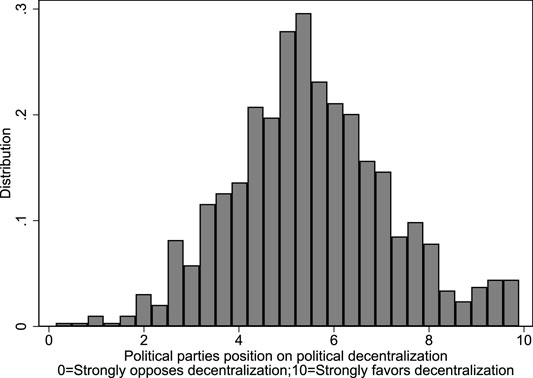

Our dependent variable is a party’s position on the territorial/political decentralization dimension. The information comes from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (1999–2019), a popular source for parties’ positions on different issues, including territorial decentralization. The Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Bakker, 2020) is coded by experts that provide evaluations on more than 200 political parties across all EU member states. Figure 1 shows the distribution of political parties position on the decentralization dimension. A low value means that a political party strongly opposes political decentralization (0 is the minimum). A high value means that a political party strongly favors political decentralization (10 is the maximum). The average in our working sample is 5.5 (std equals 1.7). In the dataset, the parties with the highest values are ERC, EA, and Amaiur, all Spanish regional parties for which political decentralization is a core aspect of their ideological stands.

We operationalize the concepts of federal arrangement, constitutional rigidity and economic shocks as follows. First, in order to capture the degree of federalism or decentralization, we use Lijphart’s dataset (Lijphart, 1999). The dataset captures each country’s degree of federalism using Lijphart’s 5-point scale index. This indicator measures the distribution of power between different levels of government, ranging from 1 (unitary) to 5 (federal). As it is known, the index correlates well with other measures of federalism used in the literature (Vatter, 2009). Second, constitutional rigidity is measured using the index of constitutional rigidity recently developed by (Tsebelis, 2021). The index departs from the idea that constitutions are an institutional outcome that originate from the interaction between institutions and different players with varying degrees of vetoing capacity. In other words, it takes into account the interaction between the institutions specified in the amendment provisions of the constitution and the preferences of the relevant actors. In other words, the index is calculated by summing the approval thresholds of different elected institutions. Hence, this approach combines the idea of veto players, which are required by the founders of the constitution, with the qualified majorities included to protect it. For all countries, the formula includes the threshold that must be reached for approval in any popularly elected body that must approve a constitutional amendment. In our dataset, the index ranges from 0.5 to 1.5. Finally, the economic shocked is captured by a dummy that distinguishes the period after the 2008 financial crisis and otherwise. The 2008 economic crisis is a perfect example of economic turmoil that unleashed a shock on institutions and political parties.

Besides using the position of political parties on the territorial dimension, in the second part of our empirical analysis we also employ three different outcomes exploring other dimensions of party competition. We once again rely on the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Bakker, 2020). The reason is that we expect our mechanism to have spillovers into other second dimensions of party competition. In other words, given the institutional nature of our argument, it is likely that political parties may have electoral incentives to moderate or accentuate their positions not only on the political decentralization dimension but also on other relevant dimensions of party competition in order to mobilize their voters. For example, if a negative economic shock occurs in countries in which the commitment problem between the majority and the minority groups has not been settled, regional parties may have electoral incentives to move to the extreme their positions on the immigration policy dimension, as well as on the values and the authoritarian dimension.

Accordingly, we explore the spillover effects of our argument into the following alternative second dimensions. First, we consider the GALTAN dimension. The green-alternative-libertarian-traditional-authoritarian-nationalist (GALTAN) dimension has been shown to structure political competition and constitutes an alternative to the traditional left-right dimension (Hooghe et al., 2002). The indicator ranges from 0 to 10, with low values being parties that have a green/alternative/libertarian position and 10 being parties that have a traditional/authoritarian/nationalist position. Second, we employ an indicator that captures a party’s policy position on the immigration dimension. The scale ranges from 0 to 10 with low values being a party that takes on a pro-immigration stance and high values a party that has an anti-immigration policy position. Third, we also use a party’s position on the European Union integration dimension. The variable ranges from 1 to 7, with low values being anti-EU positions and high values being pro-EU positions.

4 Empirical Specification

According to the theory we have developed, our empirical strategy is based on the following models. Our dataset considers political parties’ positions over time with observations at the party-country-year level:

We are interested in estimating how negative economic shocks modify political party j in country i at time t position in the territorial dimension depending on the severity of the commitment problem. To do so, we interact the institutional variables with the economic shock dummy (the post 2008 dummy). Estimations always include party fixed effects. As such, the models exploit within parties’ position variation over time and, therefore, the main effects of the institutional variables without time variation fall down on the estimation equation. The main parameter of interest is the one that captures the triple difference: β4 captures how shocks accentuate or moderate parties positions on the decentralization dimension depending on both the federalism index and the degree of constitutional rigidity.

The inclusion of party FEs is crucial in this estimation strategy since party fixed effects control for the characteristics of parties and countries that remain constant over time and therefore remove all the observed and unobserved differences across parties and countries that are fixed (e.g., other institutional features). Also, all models include the following time varying party-level Xjt controls: 1) party’s position on the left-right scale, 2) party’s position on the GALTAN dimension, 3) the percentage of votes obtained by parties, and 4) a dummy that adjusts for whether the party is the incumbent or otherwise. Finally, the models also include a linear time trend μt. The standard errors are, in all cases, clustered at the party-level. All in all, our dataset considers around 460 political parties clustered in 28 European countries from 1999 to 2019.

5 Results

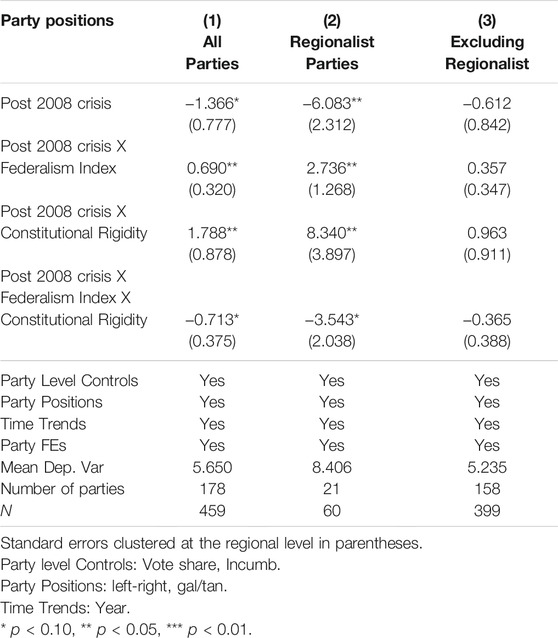

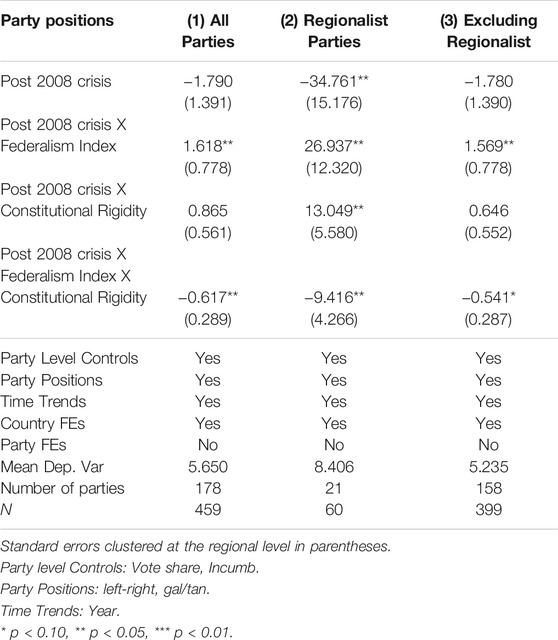

This section illustrates our main results. Table 1 shows our main models. Model 1 includes all political parties, Model 2 runs the same model only considering regional parties, and Model 3 excludes regional parties. Our coefficient of interest comes from the interaction between the post 2008 dummy, and the indices of federalism and constitutional rigidity. As it can be seen in the table, the coefficient is negative and statistically significant on the main model and on the model including only regional parties, but it does not reach significance levels in the third model, when we exclude regional parties. The negative and statistically significant coefficient means that political parties, and especially regional political parties, moderate their demands on political decentralization when an economic shock occurs and the commitment problem is sealed (i.e., with a federal deal and enough constitutional rigidity to make the deal credible). However, if any of the two institutional conditionals fails, regional parties escalate their demands when economic shocks occur.

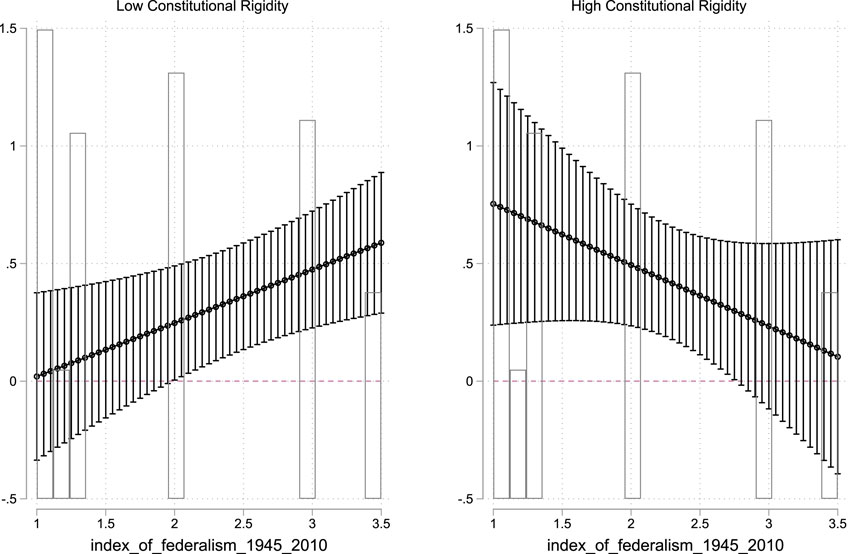

In order to better visualize our empirical test, we next plot the marginal effects of the economic shock on parties’ position on the territorial dimension as a function of the index of federalism and constitutional rigidity (Figure 2). Recall that our argument is that parties will set a moderate position on the territorial dimension when they perceive the territorial accommodation has been satisfactorily dealt with–a relatively high degree of federalism/territorial decentralization–and when the constitutional structure is rigid (i.e., guarantees are provided). If either one of the conditions is absent, parties will have incentives to exhibit a more extreme position on the territorial dimension. In other words, the territorial agreement–which grants territorial decentralization–needs to be accompanied by a system that ensures it cannot be easily amended by the majority group.

This is what we observe in Figure 2. To illustrate the results, we plot the marginal effect of the 2008 shock conditional on Lijphart’s index of federalism (Lijphart, 1999) under two scenarios: low constitutional rigidity (0.648) and high constitutional rigidity (1.33). The right-panel precisely shows the 2008 economic shock had a greater effect on parties’ policy position on the territorial dimension on those political systems that had high constitutional rigidity, but the absence of a federal contract. Instead, in countries where there is a federal agreement and a high level of constitutional rigidity, the economic shock did not push political parties to move their position on the territorial dimension to the extreme–the effect becomes statistically non-significant. Interestingly, in the left-hand figure we observe that the slope of the marginal effect reverses, whereby confirming our theoretical intuition that both conditions are necessary for a system to attenuate party competition along the territorial dimension. Indeed, a low constitutional rigidity in countries with high levels of federalism is associated with more extreme policy positions on the territorial dimension. The magnitude of the marginal effects of the negative economic shock, captured by the post 2008 dummy, on parties’ positions on the political decentralization dimension is sizeable and, at the same time, very much conditioned by the institutional variables. To put the magnitude of the effects in perspective, it is worthwhile noticing that in Figure 2, under high constitutional rigidity and with low values in the index of federalism variable, the negative shock is associated with a 0.75 increase in political parties’ demands for political decentralization–which is roughly equivalent to one half of the standard deviation of the dependent variable. Similarly, in the left-hand side panel of Figure 2 we observe that the positive effect of the negative economic shock on parties’ demands for decentralization is well above 0.5 when the index of federalism is high, but the constitutional rigidity is low. Therefore, the results largely confirm our theoretical expectation that the two dimensions of the institutional configuration (the federal deal and the credibility of the agreement through constitutional rigidity) are both necessary conditions to moderate the territorial claims of political parties–and neither of them alone is a sufficient condition to alleviate the positive effects of economic shocks on the escalation of decentralization demands.

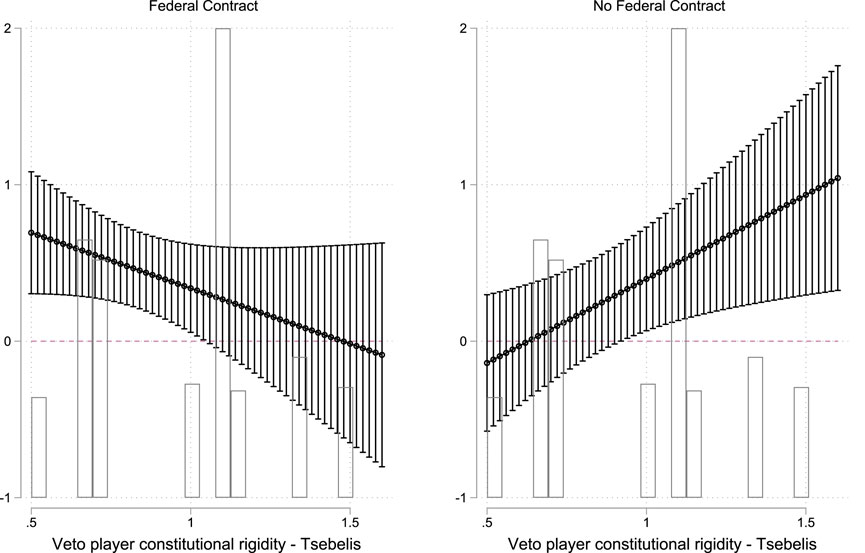

Another way of examining the relationship between the three factors is looking at Figure 3. Based once again on the results presented in Table 1, this figure now plots the marginal effect of economic shocks on parties’ position on the territorial dimension conditional on Tsebelis’s index of constitutional rigidity (Tsebelis, 2021) and under two scenarios: with a federal contract (federalism index takes value 3.5) and without a federal contract (federalism index takes value 1). The results are similar than the ones presented before. Starting with the left-hand panel, we observe that economic shocks in federal contexts are associated with more extreme positions on the territorial dimension if the system is not rigid enough. Conversely, countries that were able to agree a federal arrangement together with a relatively high degree of constitutional rigidity do not experience territorial conflict under situations of economic distress.

The right-hand panel shows that having a high constitutional rigidity and the absence of a federal contract is a particularly bad equilibrium for party competition on the territorial dimension. Under such scenario, shocks are associated with more extreme positions on the territorial debate. And this is specially the case for regional parties. The reason being, according to our theory, that if there is no federal contract and the system is very rigid, the minority group (represented by regional parties) is likely to perceive that the road to decentralization is an arduous and an uncertain one and may feel it has little options left to obtain territorial decentralization concessions.

This figure, together with the results presented in Figure 2, are in line with our theoretical argument: the territorial dimension follows a centripetal configuration in countries that have both a federal arrangement with relatively high levels of decentralization and a system that is rigid–meaning that there are effective guarantees that increase the credibility of the federal deal. Therefore, both institutional conditions are necessary. If any is absent, party competition along the territorial dimension follows a centrifugal dynamic, as parties have incentives to extreme their territorial demands. The lesson that follows is that negative economic shocks act as a triggering device that accentuate either the centripetal or the centrifugal dynamics depending on the institutional accommodation of the commitment problem.

Moreover, as Table 1 illustrates when comparing Model 2 and Model 3, this dynamic is essentially restricted to regional parties. As representative of the minority group, regional parties are arguably those affected by the sub-optimal configuration of the territorial agreement. In other words, and in line with our theoretical expectations, it is precisely when we observe the absence of a federal pact or a rigid constitution that regional parties have incentives to set a more extreme position on the territorial dimension. In contrast, other party types, as representative in a way or another of the majority group, do not have such strong incentives.

It is true, however, that future work should further explore the reaction of nationwide parties, or simply put, parties that represent the national majority groups. One interesting scenario, that we do not fully explore here, would be a scenario of political polarization in which both parties escalate their demands on the territorial dimension of party competition in opposite directions when economic shocks accentuate preexisting commitment problems: regional parties claiming further decentralization and some nation-wide parties escalating their re-centralization demands. In fact, recent experiences–for instance, in Spain–of significant escalation of political polarization on the territorial dimension suggest that the institutional roots of polarization are important and deserve further investigation.

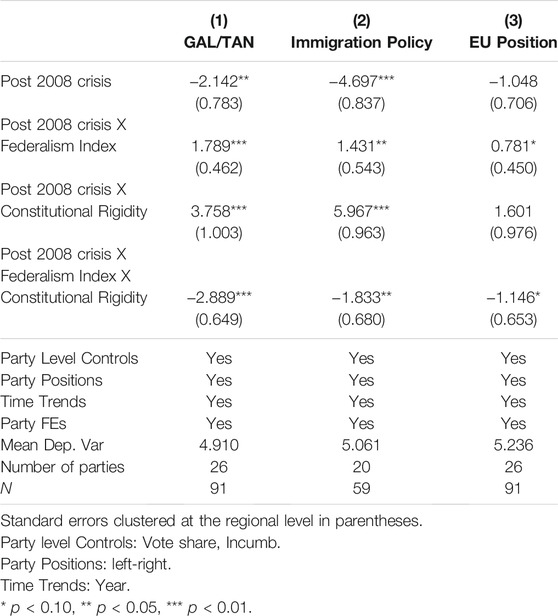

Having established that a sub-optimal institutional configurations (i.e. the inability to have resolved the commitment problem between the majority and the minority groups) are associated with higher levels of party competition on the territorial dimension when negative economic shocks occur, we next examine whether the same logic applies to other potentially relevant dimensions of political competition. The expectation being that regionalist parties might also have incentives to prime other second dimensions of party competition that are related to the territorial dimension as a response to economic shocks when they find the institutional accommodation unsatisfactory. But again, we aim to explore such parties’ differential responses to economic shocks focusing on changes in parties’ positions over time—and therefore we also include party FEs. As a result, we run the same models than before but, in this case, we use as an outcome a party’s policy position on the GALTAN dimension, on the immigration dimension and on the EU dimension. The analysis is in this case restricted to regional parties. Results are displayed in Table 2.

There are good reasons to explore how negative economic shocks polarize or moderate the positions of regional parties on other second dimensions of party competition–such as the nationalism dimension or the immigration dimension. First, regional parties may have electoral incentives to accentuate their positions on the broad nationalism dimension (or immigration views) when economic shocks occur and there is not a satisfactory institutional accommodation of persistent minority groups (Abizadeh, 2021). Thus, when a shock occurs, they might have incentives to change their position on several dimensions, not only on the territorial one. If this is the case, we should establish that economic shocks can trigger significant spillovers across several dimensions of party competition–and that such electoral spillovers fueled by negative economic shocks share the same institutional roots, the ones based on the lack of institutional accommodation of regional minority groups. Second, more in general, it is important to identify how party competition is shaped by institutional variables such as the federal agreement and the constitutional rigidity.

The analysis shows that, in the presence of an economic shock, and when the territorial configuration is satisfactorily resolved (federal arrangement and credible guarantees), regional political parties display a more moderate position on the GALTAN and the immigration dimension. In other words, in countries with a sub-optimal institutional territorial configuration, regional political parties also adopt more extreme positions on both dimensions when negative economic shocks occur. Therefore, it seems that the consequences of a sub-optimal territorial agreement spill over to other dimensions beyond the territorial one. In contrast, results in model 3 show a different picture. Although the interaction is only significant at the 90% level, the coefficient indicates that regional parties are less pro-EU in countries that experience a shock but have an optimal territorial arrangement. This might be due to several factors. One might be that, under economic distress, regional parties perceive the EU solution is going to be channelled through state institutions, circumventing regional ones, whereby bringing a less pro-EU policy position. Another explanation could lie on a sincere change in preferences towards the EU project. Future work will need to further explore both mechanisms–or others.

All in all, our empirical results suggest that the way in which institutions channel the commitment problem between the majority and the minority group is a very important determinant of the dynamics of political parties’ positions on the territorial dimension. Crucially, our results illustrate that the effects of negative economic shocks on political parties’ decentralization demands are very much conditioned by the institutional bases. Economic shocks are very much associated with the escalation of political demands by regional parties when institutions fail to accommodate the commitment problem. Thus, economic shocks are triggering devices of centrifugal dynamics, whereby bringing an escalation of political parties’ territorial demands. However, the opposite seems to be also true, since negative economic shocks are also associated with an appeasement of the territorial claims by regional parties when the country’s institutional roots provide a response to the commitment problem. In other words, a satisfactory institutional accommodation of minority groups seems to be associated with a centripetal party competition dynamic when economic shocks happen.

6 Mechanisms and Robustness

We now complete the empirical analysis with additional tests to explore the mechanisms with detail as well as some additional robustness checks. First, since our argument and theoretical mechanism focus on regionalist parties, we now run models only including regionalist parties. This is important since we have shown in the baseline models that it is mainly the regionalist parties the ones driving the results. In addition, in order to test the mechanism more directly, we introduce two important modifications to our baseline models. First, we substitute the post 2008 variable for a new dummy variable that directly captures negative economic growth. The no growth dummy takes on a value of 1 for those years in which a given country suffered a negative GDP growth and 0 otherwise. Second, we substitute the Lijphart’s federalism index by alternative measures of political decentralization and regional authority, namely the Regional Authority Index (RAI) (Marks et al., 2008). Specifically, we employ the aggregated measures of Regional Authority and Self Rule at the country level.

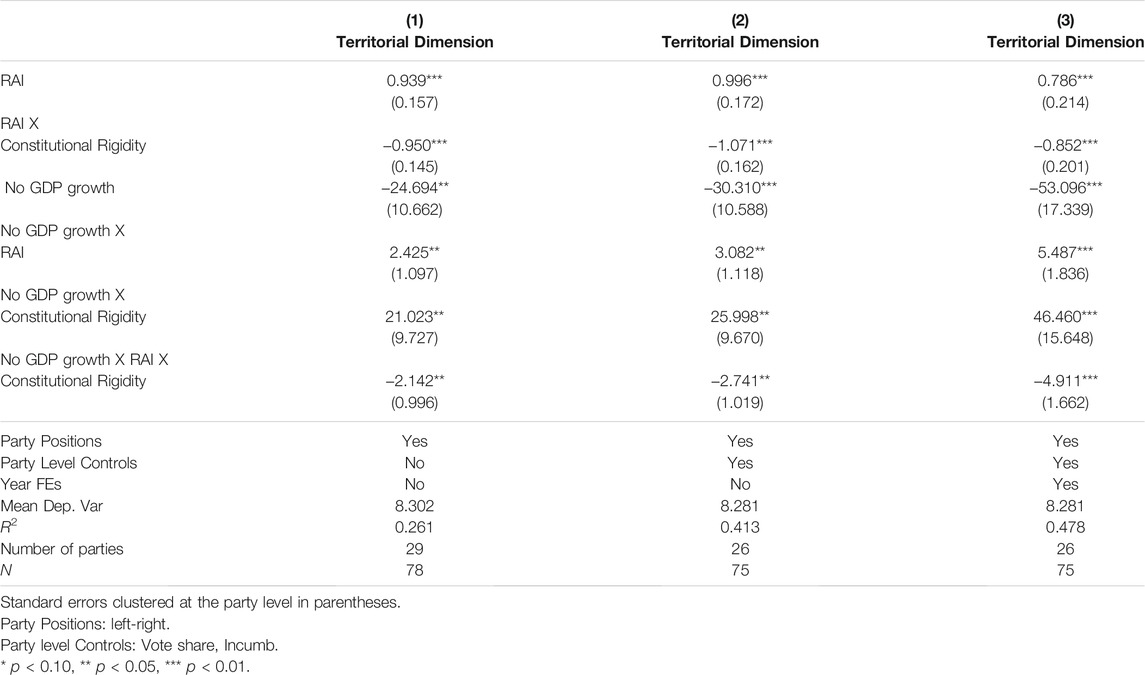

In Table 3 we run alternative specifications that are similar to our baseline models but this time using the negative growth dummy and the aggregate Regional Authority Index (RAI) (Marks et al., 2008). Note that we follow the same empirical specification as in our baseline models and therefore all columns in Table 4 include party FEs. Essentially this means that, as before, we analyze changes occurring within parties and over time. The main difference with respect to our baseline models is that now the RAI variable is time-varying. Column 1) in Table 3 does not include Year FEs, but columns 2) and 3) include Year FEs. Importantly, the measure of constitutional rigidity is the same as before (Tsebelis, 2021). All models in Table 3 include a control for parties’ position on the left-right dimension. Finally, columns 2) and 3) in Table 3 include standard party-level controls: a party’s vote share and a dummy for incumbent parties. The standard errors are in all cases clustered at the party-level.

In Table 3 we are mainly interested in the coefficient that interacts negative growth, RAI and the constitutional rigidity variable. This coefficient is negative and significant across columns (1), 2) and 3) in Table 3. This essentially means that regionalist parties are more likely to hold less extreme positions on the territorial dimension when there is an economic recession (negative economic growth), if the Regional Authority Index is high and, at the same time, constitutional rigidity is also high. However, negative economic growth coupled only with high RAI or high constitutional rigidity makes regionalist parties more likely to escalate their territorial demands. Note that the coefficients for the interaction terms between no GDP growth and RAI and no GDP growth and constitutional rigidity are both positive and significant. In other words, neither RAI nor constitutional rigidity are sufficient institutional conditions on their own to appease the demands of regionalist parties in times of economic crisis. Instead, both of them are necessary institutional conditions to appease the demands of regionalist parties when economic shocks happen. Therefore, with this alternative specification our main results hold: they are very much confirmed both when using the negative growth dummy (instead of the post 2008 one) dummy and the RAI index (instead of Lijphart’s federalism index).

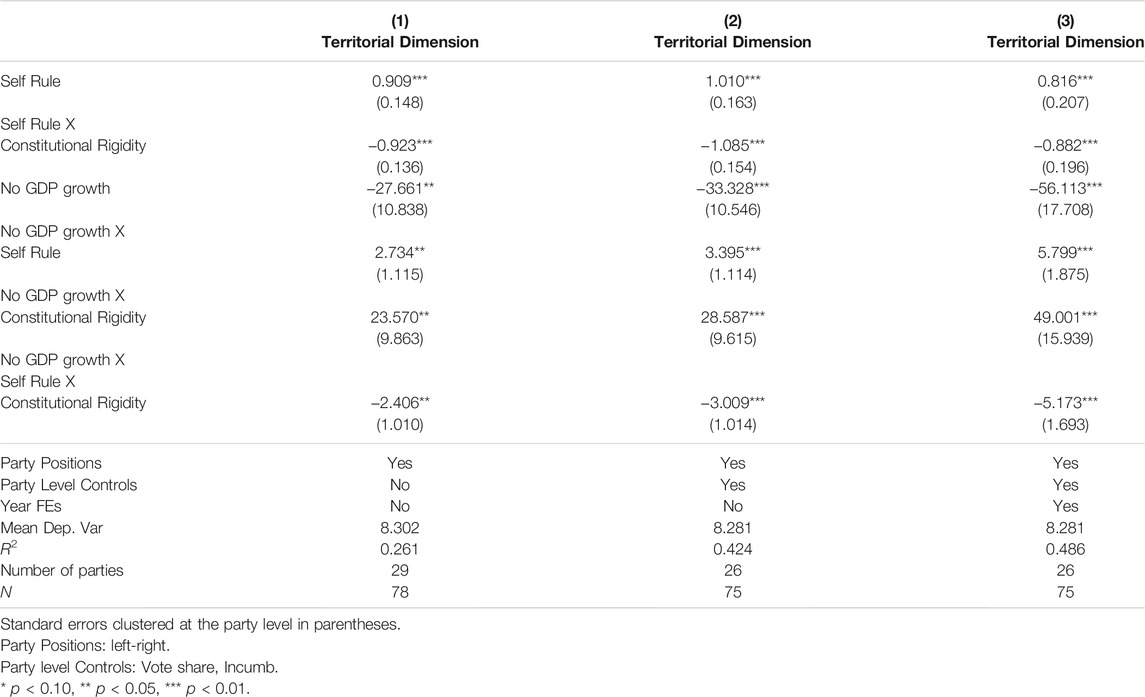

In Table 4 we run similar models but this time using the aggregated measure of Self Rule at the country level instead of the RAI measure (Marks et al., 2008). Given that the proposed theoretical mechanism has to do with the ability of regional minority groups to self-govern without interference by national majority groups, the aggregate measures of Self Rule seems an adequate proxy tackling the degree of self-government by regional identity minority groups. The econometric specification is the same one as before: the models in columns 1), 2) and 3) include all party FEs and incorporate gradually Year FEs as well as party-level controls (vote shares and an incumbent dummy). All columns in Table 4 control for regionalist parties’ positions on the left-right scale. Standard errors are clustered at the party-level.

Again, we are mainly interested in the coefficient for the interaction between no growth, Self Rule and constitutional rigidity. As expected, this coefficient is again negative and significant in all columns in Table 4. This means that when there is an economic shock, regionalist parties are less likely to hold extreme territorial positions when the aggregate levels of Self Rule are high and the levels of constitutional rigidity are high. This is very much coherent with the theoretical argument we have discussed. In times of economic crisis, with negative economic growth, regionalist parties are systematically less likely to escalate their demands when the commitment problem is institutionally sealed in a credible way. In other words, Self Rule and constitutional rigidity are both necessary conditions to appease regionalist parties in bad times.

Note, however, that in Table 4 a different picture is also depicted. It shows the estimated coefficients for the interaction terms between no GDP growth and Self Rule and no GDP Growth and constitutional rigidity are positive and significant. This means that in times of economic crisis, neither Self Rule nor constitutional rigidity are sufficient conditions for regionalist parties to deescalate their demands. If economic shocks occur with only high Self Rule or, alternatively, with high constitutional rigidity, then economic crisis systematically polarize the demands of regionalist parties. We believe that this is very much coherent with the theoretical argument we have put forward, which mainly emphasize the institutional roots of party competition and the importance of the institutional commitment problem.

To check the stability of our results, in alternative specifications not shown here we run the exact same models as in Table 3 and Table 4 but plugging in country FEs instead of party FEs. These alternative specifications are of course less demanding, since they do not account for time-unvarying political parties’ characteristics. However, the inclusion of country FEs instead of party FEs is useful to explore the variation across political parties instead of only looking at changes within parties over time. After all, our argument is essentially about parties’ differential responses to economic shocks depending on alternative institutional configurations. And importantly, the country FEs also control for observed and unobserved differences across countries that remain fixed over time. For example, controlling for alternative institutional variables that might be related to alternative institutional mechanisms. In any case, the inclusion of country FEs instead of party FEs does not modify the main results. The results remain virtually the same when we estimate the same models with the negative GDP growth dummy and the RAI and Self Rule measures. As such, the results seem to be very robust to alternative specifications.

Finally, we replicate our initial baseline models but this time employing an alternative measure of constitutional rigidity. Instead of using the recently developed measure of constitutional rigidity by Tsebelis (2021) that uses a veto-player approach, here we employ the classical country-level measure of constitutional rigidity by Lijphart (1999). The latter considers rigidity in a different fashion, namely focusing on the qualified majorities required for amendment process. In Table 5 we estimate somewhat less restrictive models by imposing country fixed effects. Given that the rigidity measure in Lijphart (1999) has more limited variation, the use of country FE is justified. Table 5 presents the analysis. As it can be seen, results are substantially the same than in our baseline models with party FEs. As before, the results seem to be driven by the behaviour of regionalist parties. Therefore, with this last specification our main results also hold: they are very much confirmed when using this alternative measure of constitutional rigidity.

7 Conclusion

This article puts forward a new way of understanding party competition. More concretely, we offer a complementary explanation of why political parties set a more moderate or extreme policy position on the centralization-decentralization dimension in democratic societies. Against the backdrop in the literature that decentralization is essentially the only way of dealing with territorial demands by political parties, we argue that, for a territorial agreement to appease parties’ territorial demands, it needs to be accompanied by a credibility tool, namely the rigidity of the institutions. Crucially, the minority group also wants guarantees that the majority group will not circumvent the agreement. Both decentralization and the rigidity of the political system change the incentives political parties have to set more (or less) extreme policy positions on the territorial dimension.

By exploiting the fact that the 2008 economic crisis put a strain on the territorial institutional design, our empirical analysis confirmed our theoretical expectations. We observe that in countries where there is a federal agreement and a high level of constitutional rigidity, the 2008 economic shock did not push political parties to set an extreme position on the territorial dimension. Conversely, a low constitutional rigidity in countries with high levels of federalism is associated with more extreme policy positions on the territorial dimension. In addition, our analysis shows that sub-optimal institutional designs also spill over to other regional parties’ dimensions, such as the broad nationalism dimension, the immigration or the EU integration dimension. In a nutshell, our empirical analysis confirms that both the federal deal and the credibility of the institutional agreement through constitutional rigidity are necessary conditions to appease the territorial conflict. None of them, however, is a sufficient condition to appease the territorial demands of regionalist parties in times of crisis.

Overall, the implications of our argument, validated with the data, are important for our understanding of the territorial conflict in democratic societies. From an academic point of view, it suggests that, in order to understand party competition on the territorial dimension, or political competition in societies with groups seeking territorial concessions, explanations need to go beyond the centralization-decentralization logic. In other words, decentralizing power to a minority group may not be enough to appease the territorial demands. As we have shown, if the system is flexible, the majority group is tempted to roll back concessions and the minority group persistently fears re-centralization policies. From a policy point of view, our results point to the need to implement measures that go beyond decentralizing power in order to effectively accommodate regional groups within the system.

An important corollary of our argument and results is that there might be a non-linear relationship between levels of decentralization and salience of territorial conflicts, since we have shown that institutional guarantees for regional minority groups also play a fundamental role. This is in line with recent works, such as (Gibilisco, 2021), that have emphasized the commitment problem between majority and minority groups as a source of non-liner territorial conflicts in multinational states. Recent political developments in countries such as Spain illustrate that the lack of guarantees for regional minority groups is a likely source of territorial conflicts–even when the levels of economic and political decentralization are at medium or high levels.

Departing from our findings, future works can take a dynamic perspective and analyze whether particular reforms strengthening the rigidity of the system lead to more or less polarization on the territorial dimension. In addition, they can also dig deeper on whether the interplay between decentralization and constitutional rigidity occurs in other crisis, such as corruption or political scandals. Finally, research in the future can bring in the dimensions of self-rule and shared-rule and analyze whether both of them play (or not) a similar role. Overall, and regardless of future approaches, we hope we have convincingly shown that, if one wants to understand party competition along the territorial dimension, he/she needs to go beyond the decentralization logic and additionally consider the institutional devices giving credibility to the territorial agreement.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.chesdata.eu/.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

FA has received and acknowledges funding from Foundation la Caixa thanks to the La Caixa Junior Leader Fellowship.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Alejandra Suarez for excellent research assistant work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1For the sake of simplicity, we mainly refer to the existence of a majority and a minority group, although this is a stylized example to develop our theoretical intuitions. Majority and minority groups can vary in number and size (Amat and Rodon, 2021), but the logic explained here still applies

2The menu of options is not restricted to centralization-decentralization. Countries can also engage in repression or set policies that dilute, over the mid/long-run, cultural differences between the minority and the majority group (Cook, 2003; Green, 2020; King and Samii, 2020). Yet, although not absent, these strategies follow different dynamics in the European countries analyzed in this article. More in general, and to know more about the relationship between party competition and decentralization, see (Brancati, 2006; Brancati, 2008; Toubeau and Wagner, 2015; Meguid, 2015; Massetti and Schakel, 2016; Massetti and Toubeau, 2020).

References

Abizadeh, A. (2021). Counter-Majoritarian Democracy: Persistent Minorities, Federalism, and the Power of Numbers. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 115, 1–15. doi:10.1017/s0003055421000198

Amat, F. (2012). Party Competition and Preferences for Inter-regional Redistribution in Spain. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 17 (3), 449–465. doi:10.1080/13608746.2012.701897

Amat, F., and Rodon, T. (2021). Institutional Commitment Problems and Regional Autonomy: The Catalan Case. Polit. Governance 9 (4).

Bakker, R. (2020). “Liesbet Hooghe Seth Jolly Gary Marks Jonathan Polk Jan Rovny Marco Steenbergen and Milada Anna Vachudova,”. Version 1.0 in 1999 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File. Available on chesdata.eu.

Basta, K. (2017). The State between Minority and Majority Nationalism: Decentralization, Symbolic Recognition, and Secessionist Crises in Spain and Canada. Publius: J. Federalism 48 (1), 51–75. doi:10.1093/publius/pjx048

Bednar, J. (2011). The Political Science of Federalism. Annu. Rev. L. Soc. Sci. 7 (1), 269–288. doi:10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102510-105522

Benz, A. (2013). Balancing Rigidity and Flexibility: Constitutional Dynamics in Federal Systems. West Eur. Polit. 36 (4), 726–749. doi:10.1080/01402382.2013.783346

Beramendi, P., and Rogers, M. (2020). Fiscal Decentralization and the Distributive Incidence of the Great Recession. Reg. Stud. 54 (7), 881–896. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1652895

Bolgherini, S. (2014). Can Austerity Lead to Recentralisation? Italian Local Government during the Economic Crisis. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 19 (2), 193–214. doi:10.1080/13608746.2014.895086

Brancati, D. (2006). Decentralization: Fueling the Fire or Dampening the Flames of Ethnic Conflict and Secessionism. International Organization 60 (3), 651–685.

Brancati, D. (2008). The Origins and Strengths of Regional Parties. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 38, 135–159. doi:10.1017/s0007123408000070

Brubaker, R. (1994). Nationhood and the National Question in the Soviet Union and post-Soviet Eurasia: An Institutionalist Account. Theor. Soc. 23 (1), 47–78. doi:10.1007/bf00993673

Coby, J. P. (2016). The Long Road toward a More Perfect Union: Majority Rule and Minority Rights at the Constitutional Convention. Am. Polit. Thought 5 (1), 26–54. doi:10.1086/684558

Cook, T. E. (2003). Separation, Assimilation, or Accommodation: Contrasting Ethnic Minority Policies: Contrasting Ethnic Minority Policies. Westport, CT: ABC-CLIO.

Del Pino, E., and Pavolini, E. (2015). Decentralisation at a Time of Harsh Austerity: Multilevel Governance and the Welfare State in Spain and Italy Facing the Crisis. Eur. J. Soc. Security 17 (2), 246–270. doi:10.1177/138826271501700206

Elias, A. (2015). Catalan Independence and the Challenge of Credibility: The Causes and Consequences of Catalan Nationalist Parties' Strategic Behavior. Nationalism Ethnic Polit. 21 (1), 83–103. doi:10.1080/13537113.2015.1003490

Elias, A., Szöcsik, E., and Zuber, C. I. (2015). Position, Selective Emphasis and Framing. Party Polit. 21 (6), 839–850. doi:10.1177/1354068815597572

Garbaye, R. (2002). Ethnic Minority Participation in British and French Cities: a Historical-Institutionalist Perspective. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 26 (3), 555–570. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.00398

Gibilisco, M. (2021). Decentralization, Repression, and Gambling for Unity. J. Polit. 83 (4), 1353–1368. doi:10.1086/711626

Green, E. (2020). Ethnicity, National Identity and the State: Evidence from Sub-saharan Africa. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 50 (2), 757–779. doi:10.1017/s0007123417000783

Hechter, M., and Okamoto, D. (2001). Political Consequences of Minority Group Formation. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 4 (1), 189–215. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.189

Hernández, E., and Kriesi, H. (2016). The Electoral Consequences of the Financial and Economic Crisis in Europe. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 55 (2), 203–224. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12122

Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States, 25. Harvard University Press.

Hooghe, L., Marks, G., and WilsonWilson, C. J. (2002). Does Left/right Structure Party Positions on European Integration. Comp. Polit. Stud. 35 (8), 965–989. doi:10.1177/001041402236310

Hutter, S., Kriesi, H., and Vidal, G. (2018). Old versus New Politics. Party Polit. 24 (1), 10–22. doi:10.1177/1354068817694503

Kettl, D. F. (2020). States Divided: The Implications of American Federalism for COVID‐19. Public Admin Rev. 80 (4), 595–602. doi:10.1111/puar.13243

King, E., and Samii, C. (2020). Diversity, Violence, and Recognition. Incorporated: Oxford University Press.

Kyvelou, S. S., and Marava, N. (2017). From Centralism to Decentralization and Back to Recentralization Due to the Economic Crisis: Findings and Lessons Learnt from the Greek Experience. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 297–326. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32437-1_12 From Centralism to Decentralization and Back to Recentralization Due to the Economic Crisis: Findings and Lessons Learnt from the Greek Experience.

Librecht, L., Maddens, B., Swenden, W., and Fabre, E. (2009). Issue Salience in Regional Party Manifestos in Spain. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 48 (1), 58–79.

Lublin, D. (2012). Dispersing Authority or Deepening Divisions? Decentralization and Ethnoregional Party Success. J. Polit. 74 (4), 1079–1093. doi:10.1017/s0022381612000667

Lutz, D. S. (1994). Toward a Theory of Constitutional Amendment. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 88 (2), 355–370. doi:10.2307/2944709

Marks, G., Hooghe, L., Arjan, H., and Schakel, A. H. (2008). Patterns of Regional Authority. Reg. Fed. Stud. 18 (2-3), 167–181. doi:10.1080/13597560801979506

Massetti, E., and Toubeau, S. (2020). The Party Politics of Territorial Reforms in Europe. Oxford, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Massetti, E., and Schakel, A. H. (2016). Between Autonomy and Secession. Party Polit. 22 (1), 59–79. doi:10.1177/1354068813511380

Meguid, B. M. (2015). Multi-level Elections and Party Fortunes: The Electoral Impact of Decentralization in Western Europe. Comp. Polit. 47 (4), 379–398. doi:10.5129/001041515816103266

Rodon, T. (2020). The Spanish Electoral Cycle of 2019: a Tale of Two Countries. West Eur. Polit. 43 (7), 1490–1512. doi:10.1080/01402382.2020.1761689

Sambanis, N., and Milanovic, B. (2014). Explaining Regional Autonomy Differences in Decentralized Countries. Comp. Polit. Stud. 47 (13), 1830–1855. doi:10.1177/0010414013520524

Sorens, J. (2012). Secessionism: Identity, Interest, and Strategy. Kingston, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Sorens, J. (2009). The Partisan Logic of Decentralization in Europe. Reg. Fed. Stud. 19 (2), 255–272. doi:10.1080/13597560902753537

Toubeau, S., and Wagner, M. (2015). Explaining Party Positions on Decentralization. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 45 (1), 97–119. doi:10.1017/s0007123413000239

Tsebelis, A. R. C. P. P. S. G., Tsebelis, G., and Foundation, R. S. (2002). Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work. EBSCO ebook academic collection Princeton University Press.

Tsebelis, G. (2021). Constitutional Rigidity Matters: A Veto Players Approach. Br. J. Polit. Sci., 1–20. doi:10.1017/s0007123420000411

Tsebelis, G. (1995). Decision Making in Political Systems: Veto Players in Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, Multicameralism and Multipartyism. Br. J. Polit. Sci 25 (3), 289–325. doi:10.1017/s0007123400007225

Vatter, A. (2009). Lijphart Expanded: Three Dimensions of Democracy in Advanced OECD Countries. Eur. Pol. Sci. Rev. 1 (1), 125–154. doi:10.1017/s1755773909000071

Keywords: economic shocks, commitment problem, political parties, decentralization, institutions

Citation: Amat F and Rodon T (2021) Negative Shocks and Political Parties’ Territorial Demands: The Institutional Roots of Party Competition. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:701115. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.701115

Received: 27 April 2021; Accepted: 03 November 2021;

Published: 29 November 2021.

Edited by:

Amuitz Garmendia Madariaga, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, SpainReviewed by:

Arjan Schakel, University of Bergen, NorwaySean Mueller, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Copyright © 2021 Amat and Rodon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Francesc Amat, Y2VzY2FtYXRAZ21haWwuY29t

Francesc Amat

Francesc Amat Toni Rodon

Toni Rodon