- Geschwister Scholl Institute of Political Science, Ludwig Maxmilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany

The German populist radical right party “Alternative for Germany” (AfD) was founded amid various economic and political crises. This article argues that the electoral success of this political challenger, however, is rooted in more than the upsurge of populist resentments born out of these crises. Integrating theories about the activation of attitudes with arguments about the effects of exposure to local political contexts, I contend that the electoral success of the AfD reflects the mobilization of deep-seated nativist sentiments. To test these propositions, I draw on a large panel dataset of the AfD’s electoral returns at the municipal level (N = 10,694) which I link to pre-crises data on the marginal success of extreme-right parties. Exploiting variation between municipalities located within the same county (N = 294), I estimate a series of spatial simultaneous autoregressive error models by maximum likelihood estimation. The results show that the success of the AfD is rooted in the local prevalence of nativist sentiments that date prior to the crises that fomented the formation of the challenger party–an effect that becomes stronger in the course of the radicalization of the AfD. I further demonstrate that the populist right AfD is best able to broaden its electoral appeal among local communities with an extreme-right sub-culture, particularly in Eastern Germany. This suggests that even small extreme-right networks can act as a breeding ground for the populist right and help spread xenophobic and nativist sentiments among citizens.

Introduction

The literature that tries to understand the rise of populist radical right parties across Europe argues that these parties’ electoral successes originate in two distinct social processes. First, populist right parties benefit from voters’ growing resentments against established political elites, their grievances related to the unresponsiveness of the political system and their eroding partisan ties to mainstream parties. The populist rhetoric of radical right parties articulates voters’ grievances related to this first set of factors (Rooduijn et al., 2016). Second, populist right parties benefit from voters’ substantive, nativist demands that relate to culturally conservative policies. Heightened levels of immigration, increased levels of ethnic heterogeneity within European societies, the erosion of traditional gender identities, or the authority transfer of national sovereignty to the European Union all appear to foster individuals’ culturally conservative attitudes and a related demand for nativist policies (Betz, 1994; Kriesi et al., 2008). The nativist, programmatic core of populist radical right parties articulates voters’ grievances related to this second set of factors (Betz, 1994; Mudde, 2007). Beyond these broad social and socio-structural processes that fuel the electoral appeal of populist radical right parties across Europe, there are also critical supply-side determinants that shape the prospects of the populist radical right. Such supply-side factors include the reactions of mainstream parties and the media to radical right challengers (Art, 2007), or the historical legacy of a country that acts to stigmatize a vote for the populist radical right in the mind of voters (Blinder et al., 2013). Germany may be one of the countries most commonly associated with the powerful impact of such an informal political norm against voting for a populist radical right party. The stigmatization of the radical right has further been reinforced by a strict ‘cordon sanitaire’ strategy of established party actors towards any of the radical right parties that have occasionally managed to achieve regional electoral successes. The lack of supply of a populist radical right party in the German national party system, however, had never been mirrored in the lack of a related demand for nativist policies among voters. Instead, the levels of authoritarian and nativist attitudes that German voters had been harboring even in absence of a successful populist right parties closely resemble the levels of such attitudes among voters in other European countries with a related party supply (Dennison and Geddes, 2019, p. 112; Norris and Inglehart, 2019, p. 204).

In this article, I argue that the electoral success of the populist right AfD is rooted in the activation of such culturally conservative attitudes that present latent political potentials for the populist right. While the AfD was founded amid various economic and political crises, deep-seated nativist attitudes had been prevalent among parts of the German electorate even prior to the experience of the different economic and political crises that eventually gave rise to the formation of the challenger party. Integrating theories of the activation of attitudes with accounts of the effects of exposure to local, extremist political contexts, this article first argues that the electoral success of the AfD at its core reflects the mobilization of latent political potentials for the radical right. These latent potentials are pre-existing, deep-seated nativist sentiments. Second, it contends that local contexts marked by the prevalence of such deep-seated nativist sentiments, even if only explicitly expressed by a small minority, further amplify the electoral appeal of the AfD within a local community, acting as societal multipliers of culturally conservative policy demands. To investigate these propositions empirically, I draw on a large panel dataset of municipal level observations in Germany (N = 10,694) and exploit within-variation at the level of counties (N = 294). In contrast to a large body of literature (e.g., Cantoni et al. (2019); Haffert (2021); Homola et al. (2020); Hoerner et al. (2019)) that seeks to explain the success of the German populist right by looking at variation between communities vis-à-vis other communities belonging to the same region (i.e., NUTS-2 territorial units that cover, on average, an area of more than 22.000 km2), the emphasis of this study is on understanding variations in the success of the populist right newcomer that exist between municipalities belonging to the same counties (i.e, geographical areas below the level of NUTS-3 territorial units that cover, on average, an area of only 1139 km2). Such an emphasis is critical for the purpose of this paper concerned with comparing local communities that share the same long-term socio-cultural history and the same short-term socio-structural experiences, but display different levels of latent radical right potentials. The results of a series of spatial simultaneous autoregressive error models by maximum likelihood estimation confirm that the success of the AfD is rooted in the disproportionate prevalence of nativist policy demands that date prior to the experience of the European economic and migration crises. The electoral appeal of the populist right challenger appears to be strongest in such local communities that used to set themselves apart from their neighbouring communities by displaying higher than average levels of support for extreme-right parties at a time when, in fact, none of these party actors was electorally significant. The results further demonstrate that this association became even more pronounced once the AfD started to develop a distinct, radical policy profile in the course of its institutionalisation. Critically, the results also reveal that the populist right AfD is best able to further broaden its electoral appeal within local communities characterised by comparatively high levels of electoral support for extreme-right parties. This effect is particularly pronounced in East Germany, where the extreme right, despite being only a marginal actor in elections, nonetheless had maintained strong local social networks. This suggests that even small local extreme-right networks can act as a breeding ground for the populist right and help to spread xenophobic and nativist sentiments among citizens. More than being only an expression of political discontent with the ruling political elites or with the convergence of mainstream parties in times of crises, the growing success of the AfD seems to be rooted in a local culture of culturally conservative and deep-seated nativist attitudes.

The article first contributes to the literature on the populist right by highlighting the significance of latent radical right potentials and drawing attention to their multiplicative nature that amplifies culturally conservative sentiments within local communities. Second, the article also advances the literature on the antecedents of populist right success by taking seriously the spatial nature of the data. The analysis of spatial data is key to our understanding of the persistence of political attitudes, and there is a nascent body of literature that tries to understand contemporary political outcomes as a function of a local community’s past. Many studies fail, however, to pay sufficient attention to the spatial dependence among the units of analysis (Kelly, 2019). Finally, more than only having important implications for our understanding of the origins of the success of the populist radical right AfD, the findings of this article also have important implications for our understanding of the determinants of the potential trajectories of populist right parties. Local networks of the extreme right act as critical societal multipliers of preferences for radical right policies. It appears that sentiments of nativism–even if initially only expressed by a small minority of extremist community members–can quickly spread from the margins to the mainstream of societies.

The article is organized as follows. I begin by offering a concise review of existing accounts that try to explain the electoral success of the AfD and the success of the populist right more generally. I then move to develop my theoretical argument and contend that latent radical right potentials are critical to understanding variation both in the success of the populist right newcomer and in its prospects for electoral growth. Subsequently, I introduce the empirical strategy of the research design before discussing the results of the simultaneous autoregressive error models by maximum likelihood estimation. The final section discusses the implications of these findings for comparative politics.

Theory and Hypotheses

Scholars trying to understand why populist radical right parties have been more successful in some countries, political contexts, and moments in time, while less so in others, most broadly differentiate between demand- and supply-side factors. Both the political, or populist, grievances of voters that relate to a declining representative capacity of the political system (Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos, 2020) and their culturally conservative, or nativist, attitudes belong to demand-side factors that are conducive to the success of the populist right. A large number of studies relying on individual-level survey data confirm that populist grievances and culturally conservative sentiments are closely linked to the (self-reported) party preferences of individuals for populist radical right actors (Ivarsflaten, 2008; Akkerman et al., 2014; Gidron and Hall, 2017; Gest et al., 2018; Noury and Roland, 2020).

At the same time, the literature acknowledges that there are critical supply-side factors that may decisively contribute to whether an existing demand for populist right policies also translates into a corresponding success of the populist right. Mainstream parties and the media react differently to the emergence and initial success of a populist right actor. Some of them try to accommodate the respective culturally conservative policy issues into their own profile, while others deliberately reject any potential cooperation with radical right parties and try to distance themselves from their programmatic positions. Yet, there is little consensus in the literature as to whether any of those strategies have an effect on the electoral success of the populist right, and if so, of which nature such an effect may be (Heerden and Brug, 2017; Meijers and Williams, 2020; Spoon and Klüver, 2020). There is, instead, greater agreement among scholars that the historical legacy of a country and a related stigmatization of a vote for the populist radical right can present a powerful barrier against radical right parties establishing themselves, acting as a ‘hostile political opportunity structure’ (Mudde, 2007, p. 245; Ivarsflaten et al., 2010; Blinder et al., 2013).

Due to the country’s historical legacy, the German political context has been proven to be particularly hostile for the populist right. In contrast to most other Western European countries, until 2013, the German party system did not feature any electorally significant populist radical-right party. The sequential experience of multiple crises, beginning with the European financial crisis that was closely followed by the European migration crisis, however, put the cultural, social and political ramifications of European integration and globalization in the spotlight of public attention in Germany. This contributed decisively to the politicization of cultural conservatism. Similar to its effects in other North-western European countries, the European financial crisis fostered the rise of Euroscepticism from the ‘New Right’ (Bremer and Schulte-Cloos, 2019; Noury and Roland, 2020). The ensuing migration crisis, which started to unfold from late 2014 and early 2015 onward, finally offered the German populist radical a powerful opportunity structure by thrusting the issue of immigration into the political centre of attention.

I posit in this article that, rather than being only born out of these crises experiences and a resulting dissatisfaction with the ruling political elites and the representative capacity of the established parties, public support for the populist right in Germany also has critical antecedents in the existence and prevalence of deep-seated nativist sentiments among parts of the German electorate that date to before these cultural, economic, and political crises. In the following, I develop my theoretical argument about the implications that such latent radical right potentials may have for the electoral success of the AfD. I contend that two related mechanisms account for the electoral ramifications of latent radical right potentials. These are, first, activation effects that make individuals’ nativist predispositions salient and cognitively accessible, in particular, when information costs related to the expression of such attitudes are low. Second, I argue that there are critical multiplier effects inherent in latent radical right potentials. These result in an amplification of pre-existing nativists attitudes by exposing individuals to local contexts that are dominated by extreme-right networks.

Activation of Latent Political Potentials

As early as the 1980s, populist radical right parties began to attract broad public support in Western European countries like Austria, France, and the Netherlands, followed somewhat later by other countries like Finland or Sweden, yet Germany remained exceptional among its Western European counterparts. The expression of outright xenophobic policy demands appeared to be particularly stigmatized among the German public (Blinder et al., 2013). While a pronounced opposition against immigration strongly predicted a vote for the extreme right German NPD (Heinrich, 2011)1, the occasional electoral successes by various extreme and populist right actors did not prove sustainable because of internal party conflicts and a lack of organizational capacity (Betz, 2002, p. 210). At the same time, however, levels of authoritarian and anti-immigrant sentiments among the German public closely resembled the respective levels of such attitudes among voters in other European countries with a related party supply (Caiani et al., 2012; Dennison and Geddes, 2019, p. 112; Norris and Inglehart, 2019, p. 204). While these latent attitudes among parts of the German public did not yet manifest themselves in a vote choice for a radical right party at large, the broad prevalence of these latent attitudes among parts of the German electorate still constituted a relevant political potential for the radical right.

Scholars concerned with understanding the political consequences of prejudice argue that individuals’ implicit attitudes can be activated when related cues or frames are cognitively accessible to individuals (Valentino et al., 2002; Winter, 2008). Upon activation, implicit attitudes and predispositions may then have consequences for political behavior. The cognitive accessibility of cues and frames related to immigration or racial prejudice may take a chronical form for some individuals, while it may take an episodical form for others. The former may be a product of individuals’ socialization, their upbringing, or their experiences in life more generally, whereas the latter may result from recent political events or recent personal experiences (Winter, 2008, p. 29; e.g., Kinder and Drake, 2009). Voters’ latent anti-immigrant attitudes appear to have been activated, for instance in response to the cognitive accessibility of the immigration issue during the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Germany experienced an influx of refugees fleeing from the civil wars in the former Yugoslavian countries (Betz, 1994, p. 133). With a related heightened salience of the immigration issue, the share of respondents who indicated that they would vote for the radical right party Republikaner rose by close to ten percentage points (Fetzer, 2000; Lubbers et al., 2002). Thus, it appears that the salience of the immigration issue activated individuals’ pre-existing anti-immigrant attitudes, exposing the political potential for the radical right dormant among parts of the German electorate. In the national election of 1994, however, when the immigration issue was crowded out by the recent German unification and their anti-immigration concerns were less cognitively accessible to German voters, the Republikaner gained only 1.9% of the public vote. While their concerns and anti-immigration attitudes thus did not prove decisive for the decision-making of most voters in the national election of 1994, the existing variation in the electoral performance of the Republikaner may still point to critical differences in the prevalence of latent political potentials for the populist right. Linking individual-level survey data from a survey conducted in 2016 to the average constituency-level support for the Republikaner in the election of 1994, Goerres et al. (2018), demonstrate that voters from electoral districts with comparatively high levels of support for the Republikaner at the time prove also more likely to indicate a preference for the populist right AfD in 2016. This finding appears remarkable as it suggests that local contexts marked by extreme-right views, even if they are only expressed by a minority (to whom anti-immigration cues may be chronically cognitively accessible) still reflect the disproportionate prevalence of latent nativist and anti-immigration sentiments. The explicit expression of nativist policy preferences at a time when none of the extreme-right parties was electorally viable might be indicative of a larger electoral potential for the populist right dormant among the other community members. Once individuals’ nativist predispositions became activated in the course of the European financial and migration crisis, the populist right newcomer AfD should be particularly likely to benefit from such latent political potentials prevalent in some, but not other, communities.

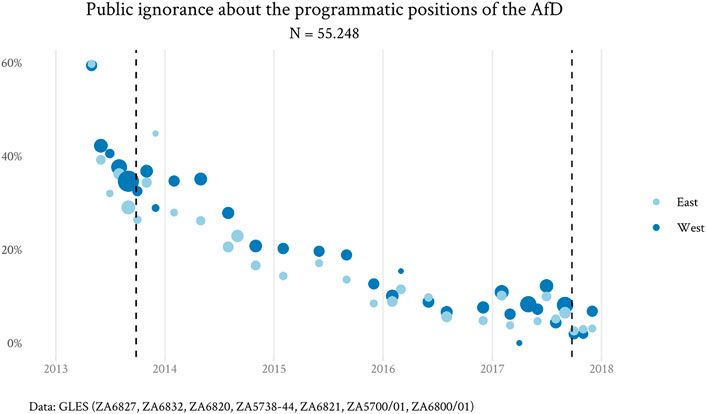

During the early existence of the party, however, the programmatic profile of the AfD was not well known to voters. Figure 1 shows the proportion of individuals who did not know where to position the AfD on a left-right scale ranging from 0 to 10. Respondents had been interviewed in a series of cross-sectional surveys conducted over the period between 2013 and 2018.2 The dashed lines represent the national elections in 2013 and 2017 that are subjects of this study. The graph shows that the share of respondents who did not hold enough information about the programmatic profile of the young populist right party to confidently locate its position on a 0 to 10 scale decreased from more than 50% in late 2013 to less than 10% in 2018. As the position of the populist radical right AfD began to crystallize over the course of its institutionalisation, the existence of a political supply for their nativist attitudes became well known to the German public (Arzheimer and Berning, 2019). Thanks to the success of the party in the EP elections of 2014 and in various state-level elections, it became additionally evident that the party was electorally viable. Translating their latently held nativist predispositions into vote choice thus became less costly for individuals as the party’s prospects for passing the electoral threshold increased. This should make it more likely that the latent potentials prevalent in some local communities but not in others became manifest in electoral support for the AfD.

FIGURE 1. Share of respondents who do not know where to position the populist radical right challenger AfD on a left-right scale strongly declined between 2013 and 2018.

Summarizing the discussion above, we shall expect that latent political potentials for the radical right, understood as pre-existing nativist sentiments initially only expressed by a minority of voters, have important implications for the electoral success of the AfD. We should also expect that such consequences are particularly pronounced when information regarding the programmatic profile and the likely electoral viability of the populist right challenger is widely available to voters. Consequently, I argue:

Latent Radical Right Potential (H1): Support for the populist radical right AfD is most pronounced among local communities with high levels of deep-seated nativism.

Thus far, I have argued that the prevalence of extreme-right sentiments at a time when none of the populist right parties was electorally viable may indicate that there is a broader, even if still dormant or latent, political potential for the radical right in some local communities. Upon activation through a favorable political opportunity structure, such latent potentials may manifest themselves in electoral support for the populist right challenger AfD. More than just reflecting the prevalence of latent, wide-spread nativist and anti-immigration sentiments, a local political context characterised by the disproportionate expression of extreme-right sentiments may further amplify the demand for nativist policies among all members of the local community in question. In the following, I turn to discussing this argument in greater detail.

Multiplicative effect of right-wing extremism at the local level

Research concerned with the effects of individuals’ exposure to local political contexts demonstrates that the local context to which individuals are exposed every day exerts a powerful influence on their attitude formation (Zuckerman, 2005; Huckfeldt, 2007). Thus, a local political culture favorable to the expression of right-wing extremist attitudes may further contribute to nurturing xenophobic sentiments among individuals who did not genuinely harbor any such preexisting sentiments in the first place (Betz, 1994, p. 81). The evolution of individual belief systems and processes of political socialization have been the subject of many classical political science accounts (e.g. Converse, 1964; Easton, 1968). Such accounts depart from the notion that cultural traits and political attitudes are not only directly transmitted intergenerationally through family socialization, but are also indirectly transmitted via imitation and learning processes from individuals’ immediate social environments (Cavalli-Sforza and Feldman, 1981; Bisin and Verdier, 2008). Their immediate and proximate social circumstances substantively impact individuals’ political beliefs and behaviors (Zuckerman, 2005, p. 26).

In view of their electoral insignificance in national party politics, the local political context played a particularly important role for German extreme-right parties. Bundschuh (2012) draws attention to the disproportionate success of extreme-right parties in places where activists were successful in adopting “social inclusion strategies.” At the heart of such inclusion strategies was the attempt of extreme-right actors to anchor themselves locally by offering help and social integration to the local civil society. Once firmly anchored within local communities, the extreme right held structural power to steer social discourse within local civil society (Bundschuh, 2012, p. 29). In particular since the 1980s, when populist radical right parties started to attract broad support in other Western European countries but failed to achieve any lasting electoral success in Germany, extreme-right actors started to build strong and institutionalized local networks on the ground (Backer, 2000; Art, 2011, p. 206). Local youth clubs with links to a number of German radical right parties (DVU, NPD, Republikaner) helped the extreme right to penetrate the local community of adolescents, acting as key transmitters of an extreme-right ideology to young voters (Zimmermann, 2003; Heinrich, 2011, p. 77). Such a sub-culture of local networks with close affinity to the radical right was particularly prominent in the GDR. It was further bolstered with new organizational opportunities after German reunification, when the East German opinion market was flooded by a large number of West German extreme-right activists and organizations (Botsch, 2012). During the 1990s, these dense local networks of extreme-right activists across Eastern German states even made it into international headlines after a series of xenophobic attacks against refugee houses (Bergmann, 1994). Speit (2009) describes the local networks of the radical right in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, marked not only by a close cooperation between the different radical right competitors, but also by the vivid presence of extreme-right movements (“comradeships”), who took responsibility for regularly organizing social events and concerts, thereby integrating the local youth into their networks in a seemingly non-political fashion. A study by Goerres et al. (2018) echoes the notion that political socialization within a local context marked by extreme-right networks contributes to the formation of culturally conservative attitudes among adolescents and amplifies average preferences for nativism more generally. The authors find that among voters in a former local electoral stronghold of the radical right party Republikaner, even those who were too young to vote in the party’s heyday are more likely to report partisan preferences for the populist right challenger AfD.

It appears that local networks of the extreme right act as breeding grounds for populist right sentiments, contributing to the spread of xenophobic and authoritarian preferences among citizens. The prevalence of deep-seated nativist attitudes among parts of a local community—evident in the explicit electoral expression of nativist attitudes prior to sequential experience of the European financial and migration crises and prior to the existence of a viable populist right party within the German party system—may shape the local environment within a community, carrying critical effects for attitude formation among community members and their political socialization. In such communities, the populist right newcomer AfD should be able to disproportionally amplify its electoral success and readily broaden its electoral appeal over time. Therefore, I argue:

Multiplier Hypothesis (H2): The increase in the success of the populist radical right AfD is most pronounced among local communities with high levels of deep-seated nativism.

Data and Research Design

I draw on a dataset that entails fine-grained information on the electoral performance of the populist right and former levels of radical right support at the municipal level in a total of six different nation-wide elections between 2009 and 2019. Half of these six elections are national elections (2009, 2013, 2017), while the other half are European Parliament (EP) elections (2009, 2014, 2019). The dataset is organized as a panel dataset, in which each municipality is observed six times and any administrative reforms that took place between 2009 and 2019 are taken into account.3 Administrative reforms and municipality mergers do not occur at random. Instead, they may systematically relate to factors like out-moving and local structural decline that could affect both the level of extreme-right support in 2009 and levels of support for the populist right AfD. Disregarding any observations that cannot be integrated into the panel structure would thus not only reduce the number of observations in the data, but also underestimate the impact of the latent demand for radical right policies at the local level. Therefore, the panel structure of the dataset appears critical.

The outcome of interest is the municipal level support for the populist right AfD in all nation-wide elections that the party has contested since its existence, i.e., the national elections in 2013 and 2017 and the EP elections in 2014 and 2019. In addition to studying the levels of support for the AfD, I also look at the change in electoral support across the respective elections to study the Multiplier Hypothesis (H2). The central independent variable measures the level of electoral support for any of the right-wing extremist parties during the national (2009) and EP election (2009) prior to the existence of a successful populist right party within the German party system. These parties include the ‘major’ right-wing extremist parties NPD, DVU, Republikaner, and some smaller right-wing extremist parties that have only occasionally received public attention (Die Rechte, Offensive D, Bueso). These parties have their roots in different phases of the history of German right-wing extremism, shaping the different nuances of their programmatic outlook on society (e.g., Betz, 2003). Yet, already by the late 1990s, the programmatic preferences of members and activists appeared to converge to a clear common programmatic core (Lubbers and Scheepers, 2001), leading some party members to even consider uniting forces (Backer, 2000, p. 113). To comprehensively capture the prevalent demand for radical right preferences within some local communities irrespective of the different party labels and different regional strongholds of the various parties (Zimmermann, 2003), I therefore consider the total vote share of all these parties that competed in the 2009 national and 2009 EP election.

I rely on a county-fixed effects design to isolate the effect of latent radical right demand on the electoral success of the AfD from any structural variation between municipalities. On average, the 294 counties in the data cover a small area of only 1139 km2. The analysis thus compares municipalities that share both the same long-term socio-cultural history and the same short-term socio-structural experiences but display different levels of latent radical right potentials.4 This strategy also allows me to effectively account for any differences between counties regarding their unemployment rate or the vulnerability of their local economy to the economic consequences of globalization. This is critical as previous studies document that a county’s (e.g., Colantone and Stanig, 2018) or a region’s (e.g., Stockemer, 2017) exposure to the repercussions of economic globalization act as a breeding ground for populist (right) attitudes among voters. The within-county research design further holds constant any differences in the party supply that may relate to the organization of the populist right ‘on the ground,’ i.e., its organization in county-level party branches. As counties are administrative units below the level of the sixteen different German states, the design also accounts for differences in the party system supply between regions prompted by the representation of the populist right in some state parliaments (Valentim and Widmann, 2021). I further include other municipal-level characteristics that may systematically relate to both the success of the populist right AfD and a latent demand for populist right policies prior to the party’s existence. These are, first, variables that capture the political disaffection within a local community prior to the existence of the populist right AfD, namely the share of invalid ballots and the abstention rate in the respective national and EP elections of 2009 (Allen, 2017; Aron and Superti, 2021; Schulte-Cloos and Leininger, 2021; Silva and Crisp, 2021). In addition, the models also account for the socio-structural deprivation of municipalities by including the relative change in the size of the municipalities with respect to 2009, the population density within the area of a given municipality, the total size of its territorial area, and its degree of urbanization (Maxwell, 2019) according to the official EU classification of municipalities (“LAU” level) in three different categories (the baseline categories across all models are strongly urbanized areas, i.e., cities). To account for greater expressive voting in the presence of a locally resident single-member district candidate (Schulte-Cloos and Bauer, 2021), I also include an indicator variable that measures whether a local candidate runs in the national elections.

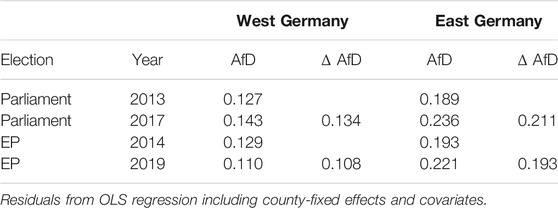

When trying to understand variation in populist right support at the fine-grained level of local communities, it is critical to acknowledge the spatial nature of the data and address the challenges for statistical inference that originate in the potential presence of spatial dependence. The political preferences and the level of populist right support of local communities may not be spatially independent from each other. Instead, they may be caused by behavioral diffusion or common attributes of municipalities within the same region. This has been famously expressed in Tobler’s First Law of Geography, according to which “everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things” (Tobler, 1970, p. 236). Thus, we first diagnose the prevalence of spatial dependence in the data. Table 1 reports the global Moran I’s test statistic of the residuals of a “naive” OLS regression model that does not take any spatial dependence of the data into account. While the degree of the spatial dependence after the inclusion of county-fixed effects and municipal level covariates5 is moderate, with values ranging from 0.11 to 0.24, these values are all still highly statistically significant (p < 0.01). Therefore, I rely on the Lagrange Multiplier test to determine whether the spatial dependence is a result of spatial lag and/or spatial error correlation (see Table A4 and Table A5 in the Appendix). The results of these tests point to the presence of spatial error dependence in the absence of any spatial lag dependence. It is critical to model the spatial error dependence to avoid wrong inferences (type I error) based on overly optimistic standard errors in the OLS estimates.

Thus, I present spatial simultaneous autoregressive error models by maximum likelihood estimation, relying on a queen-style contiguous neighbors definition, in which all polygons contiguous to a municipality i are considered neighbors (Anselin, 1988, p. 18). The spatial simultaneous autoregressive error model by maximum likelihood estimation can be described as

y = Xβ + ϵ ϵ = λWij + ξ

where λ is the spatial autoregressive parameter for the spatially lagged error term, Wϵ is a spatially lagged error term with spatial weights matrix and ξ a random error term assumed to be iid. Wij is the (i, j)th element of the n-by-n spatial weights matrix with non-zero elements in each row i for columns j that are contiguous (queen-style) neighbours of area i. The dependent variable y is the level/growth of the vote for the populist right AfD and X is a vector of explanatory variables.

Results

I first report the results from models estimating the level of populist right success to assess the Latent Radical Right Potential Hypothesis. Subsequently, I exploit the panel nature of the dataset and assess the Multiplier Hypothesis by studying the municipal level growth in electoral support for the AfD. Throughout the analysis, I estimate separate models for municipalities that are part of Eastern and Western Germany. Even 30 years after reunification, the two different regions display substantive differences in political preferences, the strength of regional identities, or anti-immigrant and nativist attitudes (Betz and Habersack, 2019; Arzheimer, 2021; Hildebrandt and Trüdinger, 2021). Critically, these differences cannot only be attributed to the experience of the authoritarian regime in the GDR (Backer, 2000). They may, instead, also date back to a more distant past and express long-standing socio-political differences between the two regions. These differences relate, for instance, to the size of the manufacturing sector, the strength of the Left, or different levels of religiosity (Becker et al., 2020).6 The distinction between electoral support for the AfD across Eastern and Western Germany is also important as the party supply across both regions has been markedly different since as early as 2013 (Jankowski et al., 2017). All continuous variables are standardized with respect to their region-specific means to ensure that the average one-unit increase expressed in the coefficients represents a meaningful unit of change for all observations in the dataset. Across the different regions, there have been marked differences in both average levels and the variation in the level and the growth of populist right AfD success (see Figure A1 in the Appendix).

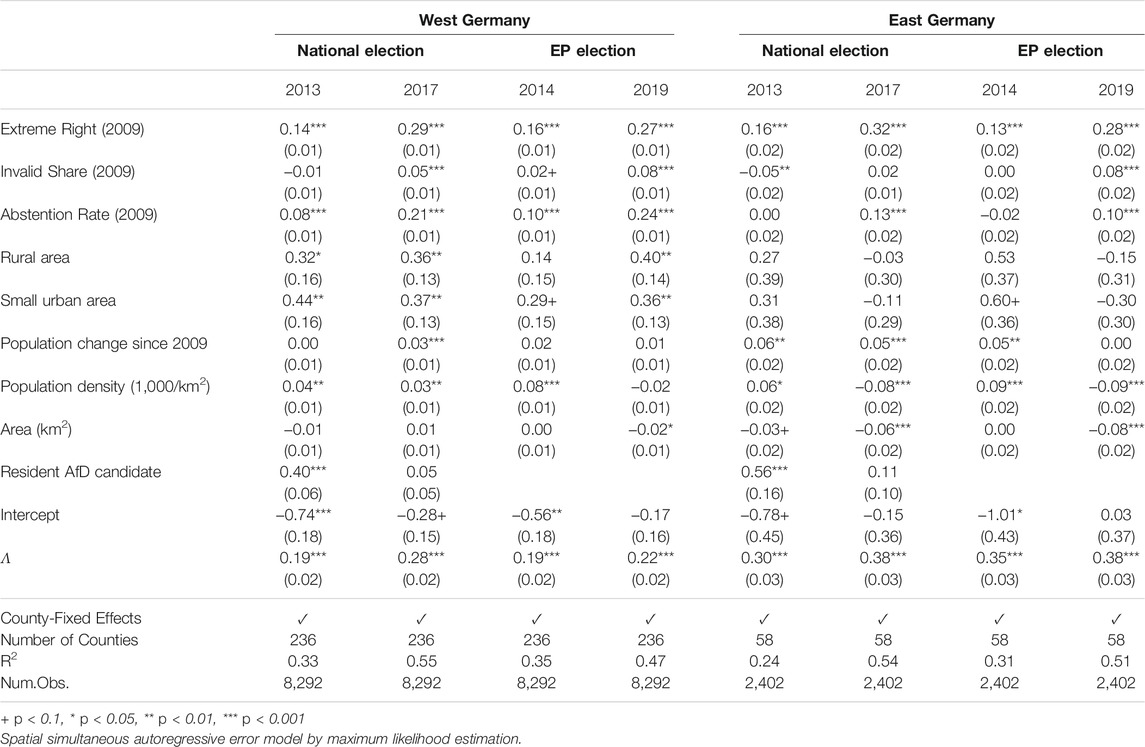

Table 2 presents the results of the models predicting the electoral success of the populist right AfD across all elections as a function of the extreme right’s support during the elections prior to the existence of the AfD. The coefficient of the central independent variable of interest is significant across all models. Since the AfD’s very inception, previous levels of extreme right support are positively associated with the extent of electoral support for the newcomer party. The strength of this association also appears to be substantive in magnitude. A municipality located in Western Germany with a greater level of support for extreme right parties in 2009 than its counterparts within the same county displays a 0.14 standard deviation greater support for the AfD during the national election 2013 (see column 1 of Table 2). This finding is notable as the policy profile of the party and the base of its electoral constituency was far from being clear during the early period of the party’s existence. We observe a substantially similar effect when predicting the municipal level success of the AfD during the EP election 2014 as a function of prior support for right-wing extremist parties like NPD, DVU, or Republikaner during the EP elections 2009 (see column 3 of Table 2). This finding also travels to municipalities located in the Eastern part of Germany (see columns 5 and 7 of Table 2). It is important, however, to note that the substantive differences in the one-unit increases of right-wing extremist support are expressed in standard deviations. Among the municipalities in Eastern Germany, a standard deviation of right-wing extremist support is around one percentage point larger than among municipalities in Western Germany (2.38 vs. 1.33 during the national election in 2013, see also Table A1 and A2 in the Appendix).

The association between a local community’s extreme right preferences prior to the existence of the AfD and the success of the populist right newcomer becomes even stronger during the elections of 2017 (national election) and 2019 (EP election). Across the different models, the related coefficients are around double the size of the coefficients pertaining to the performance of the populist right party during its first elections of 2013 (national election) and 2014 (EP election). In Eastern Germany, an increase of one standard deviation in the level of extreme right support in 2009 boosts the electoral appeal of the populist right challenger during the 2017 national election by 0.32 standard deviations (see column 6 or Table 2). The effect size is substantively similar for Western German municipalities. It also travels to the AfD’s performance during the EP election 2019 (see Table 2). While the party’s profile initially might not have closely resembled the policy profiles of other populist radical-right parties across Western Europe, the radical-right ideology lying at the party’s core began to crystallize more clearly in the course of the party’s institutionalization. It appears that this radicalization process was most favorably evaluated among local communities previously expressing comparatively high levels of support for any of the electorally insignificant extreme right parties. This suggests that the populist radical right AfD could substantially capitalize on the pre-existing nativist sentiments among parts of the German electorate. Table A6 shows that we obtain highly similar results when operationalizing a local community’s latent radical right potential with the extreme right vote share during the national election of 2005, i.e., an even more conservative measure of the locally prevalent demand for nativist policies that existed in some communities prior to the sequential experience of the European financial crisis and the migration crisis.

Taken together, the results demonstrate that the latent political potentials for the AfD started to manifest as early as in 2013, at a time when the radical right core of the party was not fully evident and large parts of the public were still ignorant as to the programmatic nature of the party. The effect size became substantively stronger in the course of the challenger party’s institutionalization and a related programmatic radicalization of the AfD. With a growing awareness about the party’s programmatic profile on behalf of the citizens and a lower uncertainty regarding its likely electoral success, the latent political potentials became even stronger in their manifestations. Thus, it appears that the populist radical right party substantively benefited from pre-existing nativist sentiments, supporting H1 (Latent Political Potential Hypothesis).

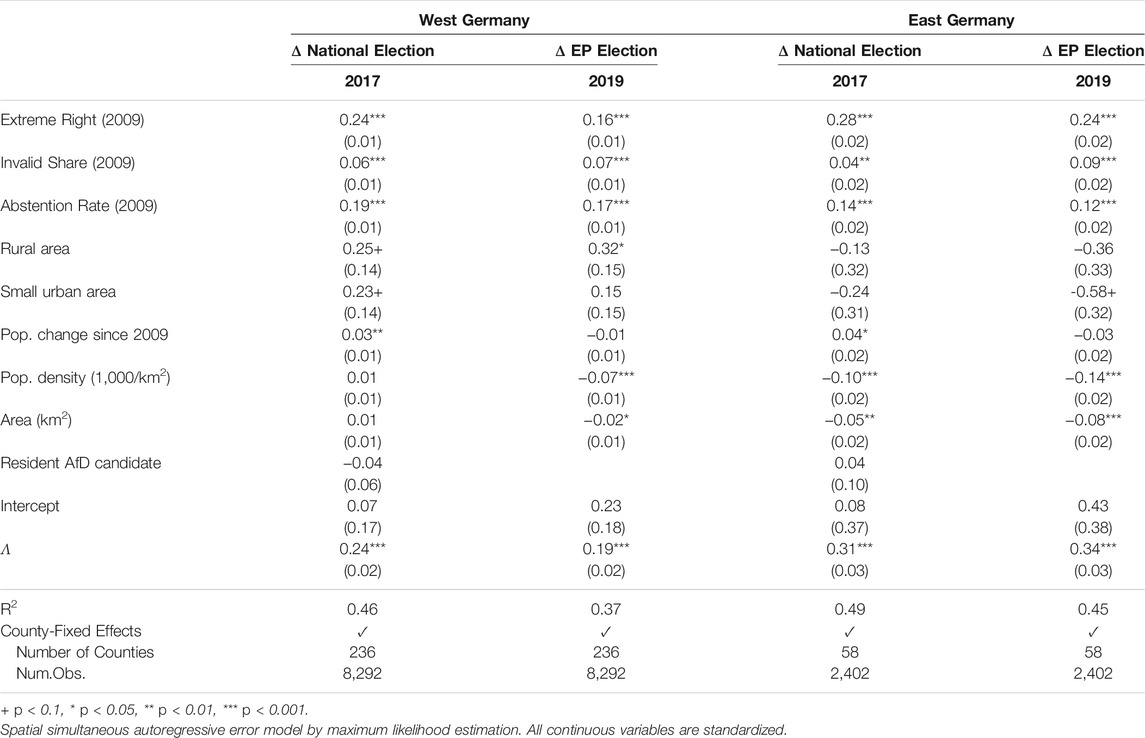

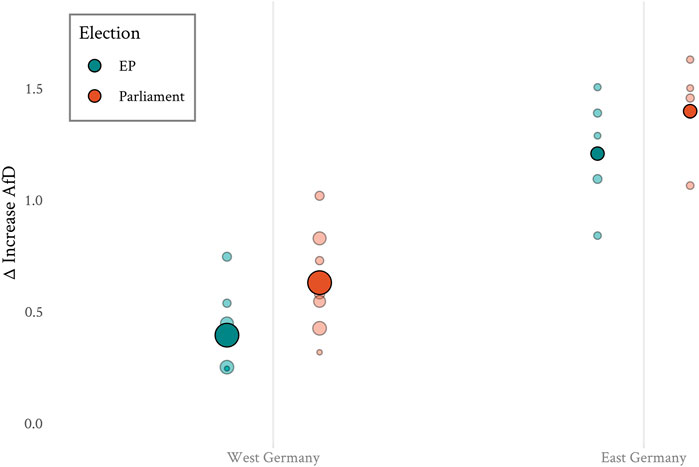

I next turn to assess the H2 (Multiplier Hypothesis). To do so, I exploit the panel structure of the municipality dataset and study the change in electoral support for the populist radical right challenger between the two elections as a function of a local community’s history of electoral support for extreme right parties. If there is a multiplicative nature inherent in the prevalence of deep-seated nativist attitudes within a local community, differences in the explicit expression of nativist sentiments should affect the extent to which the electoral success grows within a given local community between the different elections. Table 3 presents the results of the models assessing this pattern. Columns 1 and 2 refer to municipalities located in Western Germany, while columns 3 and 4 refer to municipalities located in Eastern Germany.

Across Western Germany, with an increase by one standard deviation in the level of extreme-right voting in 2009, on average, the populist radical right broadens its success by 0.24 standard deviations. For the Western German municipalities, such an increase by one standard deviation, on average, corresponds to an increase of 0.63 percentage points in right-wing extremist voting. The effect size is somewhat smaller for the EP election (0.39, see also the estimates in dark shading presented in Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Effect of extreme-right support (2009) on growth of populist right success in local communities. Darker shading indicates the overall average percentage point increase while lighter shading indicates the respective effect sizes for the different regions.

Figure 2 also shows that there are some differences in the size of this effect across the different regions (shown in light shading), yet the absolute effect sizes are still largely comparable across the different states in West Germany. The magnitude of the effect, however, is substantively larger across municipalities in Eastern Germany. Within municipalities belonging to the former territory of the GDR, we observe that an increase in the level of right-wing extremist voting in 2009 by one standard deviation, on average, prompts the electoral growth of the populist right by 0.28 (national election) and 0.24 (EP elections) standard deviations. We can grasp the substantive size of these estimates when contrasting local communities with the region-highest and region-lowest support for the extreme right in 2009. In 2017, the AfD increased its election result by over 4.6 percentage points in municipalities that belong to the five percent of municipalities with the largest former extreme-right electorate (where extreme-right parties obtained approximately 5.21 percent of the vote) compared to municipalities that belong to the five percent of municipalities with the smallest extreme-right electorate (where extreme-right parties obtained approximately 3.89 percent of the vote). This difference is largely similar in the EP elections of 2019.

Municipalities with the greatest explicit support for extreme-right parties at a time when all of those parties played only a marginal role in German party politics do clearly set themselves apart from their county’s remaining municipalities by offering a more fertile ground for the electoral growth of the challenger party AfD. It is important to note that these comparatively high levels of former extreme-right support still only reflect the votes of a small minority of individuals within a local community. Even in local communities belonging to the upper third of all communities with the highest level of pre-crises extreme-right support, the average cumulative vote share of all extreme-right parties did hardly exceed five percent. Harboring views extreme enough to still cast a ballot for one of these marginal extreme-right parties, this minority of individuals, however, was often highly engaged in dense social networks at the local level with the power to steer social discourses among the local civil society (Zimmermann, 2003; Speit, 2009; Heinrich, 2011, p. 77; Bundschuh, 2012). The extreme-right vote share at the local level is highly indicative of the presence of such social networks as can be seen in Table A8. Table A8 demonstrates that the electoral success of the extreme right in 2009 is strongly associated with the local density of extreme-right activists. It appears that these networks helped the populist right newcomer to quickly gain ground and broaden its electoral appeal among a large group of local community members.

While we did not observe a consistent impact of a community’s baseline levels of political alienation (invalid voting and rates of abstention) when trying to predict the level of electoral success for the AfD, these variables do appear powerful in explaining the growing electoral appeal of the political party within certain local communities. As all variables have been standardized with respect to their mean values, we can also compare the effect sizes to those of deep-seated nativist attitudes. We focus on such a comparison among Eastern German municipalities (columns 3 and 4 of Table 3), which appears particularly relevant as scholars concerned with understanding populist attitudes in Germany assume that political alienation and feelings of status loss are particularly widespread among individuals living in the former regions of the GDR (Arzheimer, 2021). With an increase of one standard deviation in the level of invalid voting (abstention rate) in 2009, on average, we observe that the populist radical right broadens its success by 0.04 (0.14) standard deviations. The effect of a latent radical right potential within a local community in Eastern Germany, is thus around twice as large as the effect of the potential for the populist right inherent in widespread political disaffection.

Taken together, these results support H2 (Multiplier Hypothesis). It appears that the populist radical right challenger AfD was best able to broaden its electoral success within those local communities in which a minority of citizens had already harbored deep-seated nativist and xenophobic attitudes prior to the experience of the various crises unfolding in the 2010s. Their attitudes of this kind must have been strong and explicit enough that they chose to express them in a vote for an extreme-right party at a time when none of these parties had any real prospects to gain representation. While without any real prospects to gain representation, the literature documents that those extreme-right parties still maintained dense social networks, in particular in communities located in the Eastern part of Germany. The results thus suggest that such social networks maintained by the extreme right played a critical role in multiplying and amplifying the radical right demands among some German voters. This finding appears highly relevant as it demonstrates that local extreme-right networks, even if only marginal in size, can act as breeding ground for the populist right, helping to spread nativist and authoritarian sentiments among citizens.

Discussion and Conclusion

While German populist radical right parties remained electorally insignificant until the recent emergence of the AfD, levels of anti-immigration attitudes among German voters had been largely comparable to those of voters in other Western European countries. This study has argued that the electoral success of the populist right AfD is rooted in the activation of such culturally conservative sentiments that present latent political potentials for the populist right. Importantly, such sentiments had been prevalent among parts of the German electorate even before the series of economic and political crises that eventually led to the formation of the AfD. Integrating theories of attitude activation with accounts of political socialization within local political contexts, the article contended that the electoral appeal of the populist right challenger AfD is most pronounced in local communities with high levels of latent yet deep-seated nativist and xenophobic sentiments. While only a tiny share of voters might have expressed these sentiments in a vote for any of the electorally insignificant extreme-right parties, I have argued that variation in the pre-crises level of extreme-right support at the local level is highly indicative of a dormant electoral potential for the populist right challenger AfD. To study these prepositions, I drew on a large dataset of electoral returns of the populist right party at the municipal level (N = 10,694), linked to historical data on the performance of extreme-right parties, and presented a series of spatial simultaneous autoregressive error models by maximum likelihood estimation including county-fixed effects (N = 294). The results showed that the success of the AfD is indeed rooted in the prevalence of nativist and culturally conservative policy-demands in some local communities that date prior to the existence of the populist right AfD. Within-county variation in the appeal of the populist right strongly relates to a local community’s history of right-wing extremism. This association becomes even stronger in the course of the radicalization of the populist right and once the party developed a distinct radical right profile. The results of this study also provided evidence that the populist right AfD was best able to broaden its electoral appeal among local communities with an extreme right sub-culture. This effect is particularly pronounced in local communities belonging to the Eastern German regions, a finding that bears particular importance in suggesting that even small, local extreme-right networks can act as breeding ground for the populist right, helping to spread xenophobic and nativist sentiments among citizens.

More research is necessary to understand the long-term ramifications of those societal antecedents that appear to have critically fostered the success of the German populist right. Future research should also try to disentangle the individual-level factors underpinning the findings presented in this study that are based on fine-grained spatial data. Studying the individual-level support for radical-right parties depends not only on the availability of appropriate survey instruments that can tap into latent attitudinal dimensions, but also on the likelihood that individuals who hold deep-seated nativist views can be approached for scientific studies and, ideally, be reached over an extended period of time in a panel study design (Dahlgaard et al., 2018). While the results of this article should thus be complemented with individual-level data, the analysis of electoral returns at the level of local communities still offers critical insights into the antecedents of support for the populist radical right as much as it offers insights into the role that these antecedents have in amplifying nativist sentiments within local communities. More than being only an expression of political discontent with the ruling political elites or with the convergence of mainstream parties in times of crises, the growing success of the AfD seems to be rooted in a local culture of deep-seated nativist sentiments.

Data Availability Statement

All data and code is stored at Harvard Dataverse (DOI: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UYKYIL). The repository also contains a Dockerfile that allows to run all analyses in a reproducible environment.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Framework Programme for Research and Innovation Horizon 2020 (2014–2020) under the Marie SkÅ‚odowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 754388 (LMUResearchFellows) and from LMUexcellent, funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the Free State of Bavaria under the Excellence Strategy of the German Federal Government and the Länder.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank the editors and the two reviewers for their feedback. I am grateful for feedback from Daniel Bischof, Valentin Daur, Christina-Marie Juen, Hanspeter Kriesi, Julian Schüssler, Rune Slothuus, and Bartek Pytlas. I also appreciate feedback from participants of the Political Behavior section meeting at Aarhus University, participants at the General Conference of the European Consortium for Political Research, and participants at the German Political Science Association’s Convention.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.698085/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1A systematic analysis of voters of the German extreme right is made difficult because of the extremely low number of respondents who indicate a preference for the extreme right in nationally representative surveys (e.g., GLES, ESS).

2The data are taken from the German Longitudinal Election Study (the corresponding identifiers of the datasets are: ZA6827, ZA6832, ZA6820, ZA5738-44, ZA6821, ZA5700/01, ZA6800/01). The proportion shown in the graph refers to the share of respondents who indicated “do not know” when asked to position the populist right party on a left-right scale from 0 to 10.

3The Appendix presents a detailed discussion of the creation of this municipal-level panel dataset.

4As I rely on within-county variation in electoral support for the AfD, counties that consist of a single municipality are excluded from the analysis.

5Table A3 in the Appendix reports the univariate global Moran I’s test statistic for the dependent variable. Without including county-fixed effects and covariates, the spatial dependence on the dependent variable is substantively greater, with values ranging from 0.27 to 0.49.

6Note also the differences between Eastern and Western Germany regarding the socio-structural characteristics of the municipalities as shown in Table A1 and Table A2 in the Appendix.

References

Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., and Zaslove, A. (2014). How Populist Are the People? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Voters. Comp. Polit. Stud. 47, 1324–1353. doi:10.1177/0010414013512600

Allen, T. J. (2017). Exit to the Right? Comparing Far Right Voters and Abstainers in Western Europe. Elect. Stud. 50, 103–115. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2017.09.012

Aron, H., and Superti, C. (2021). Protest at the Ballot Box: From Blank Vote to Populism, 1354068821999741. Party Politics.

Art, D. (2011). Inside the Radical Right: The Development of Anti-immigrant Parties in Western Europe. Cambridge University Press.

Art, D. (2007). Reacting to the Radical Right. Party Polit. 13, 331–349. doi:10.1177/1354068807075939

Arzheimer, K. (2021). “The Electoral Breakthrough of the AfD and the East-West divide in German Politics,” in From the Streets to Parliament? the Fourth Wave of Far-Right Politics in germany: Routledge.

Arzheimer, K., and Berning, C. C. (2019). How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Their Voters Veered to the Radical Right, 2013-2017. Elect. Stud. 60, 102040. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004

Backer, S. (2000). “Right-wing Extremism in Unified germany,” in The Politics of the Extreme Right: From the Margins to the Mainstream, 87–120.

Becker, S. O., Mergele, L., and Woessmann, L. (2020). The Separation and Reunification of germany: Rethinking a Natural experiment Interpretation of the Enduring Effects of Communism.

Bergmann, W. (1994). Anti-semitism and Xenophobia in the East German lander, 3. German Politics, 265–276. doi:10.1080/09644009408404365

Betz, H-G. (2003). “The Growing Threat of the Radical Right,” in Right-wing Extremism in the Twenty-First century. Editors P. Merkl, and W. Leonard (Portland: OR: F. Cass), 71–89.

Betz, H.-G. (2002). “Conditions Favouring the success and Failure of Radical Right-wing Populist Parties in Contemporary Democracies,” in Democracies and the Populist challenge. Editors Y. Mény, and Y. Surel (Springer), 197–213. doi:10.1057/9781403920072_11

Betz, H.-G., and Habersack, F. (2019). “Regional Nativism in East germany,” in The People and the Nation: Populism and Ethno-Territorial Politics in Europe (London, UK: Routledge), 110–135. doi:10.4324/9781351265560-6

Bisin, A., and Verdier, T. (2008). Cultural Transmission, 1–8. The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 1225–1229.

Blinder, S., Ford, R., and Ivarsflaten, E. (2013). The Better Angels of Our Nature: How the Antiprejudice Norm Affects Policy and Party Preferences in Great Britain and Germany. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 57, 841–857. doi:10.1111/ajps.12030

Botsch, G. (2012). From Skinhead-Subculture to Radical Right Movement: The Development of a ‘national Opposition’in East germany, 21. Contemporary European History, 553–573. doi:10.1017/s0960777312000379

Bremer, B., and Schulte-Cloos, J. (2019). “The Restructuring of British and German Party Politics in Times of Crisis,” in European Party Politics in Times of Crisis (Cambridge University Press), 281–301. doi:10.1017/9781108652780.013

Bundschuh, S. (2012). Die braune seite der zivilgesellschaft: Rechtsextreme sozialraumstrategien, 62. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 18–19.

Caiani, M., Della Porta, D., and Wagemann, C. (2012). Mobilizing on the Extreme Right: Germany, italy, and the united states. Oxford University Press.

Cantoni, D., Hagemeister, F., and Westcott, M. (2019). Persistence and Activation of Right-wing Political Ideology.

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., and Feldman, M. W. (1981). Cultural Transmission and Evolution: A Quantitative Approach. Princeton University Press.

Colantone, I., and Stanig, P. (2018). Global Competition and Brexit, 112. American Political Science Review, 201–218. doi:10.1017/s0003055417000685

Converse, P. E. (1964). “The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics,” in Ideology and Discontent (Free Press), 206–261.

Dahlgaard, J. O., Hansen, J. H., Hansen, K. M., and Bhatti, Y. (2018). Bias in Self-Reported Voting and How it Distorts Turnout Models: Disentangling Nonresponse Bias and Overreporting Among Danish Voters, 1–9. Political Analysis.

Dennison, J., and Geddes, A. (2019). A Rising Tide? the Salience of Immigration and the Rise of Anti-immigration Political Parties in Western Europe, 90. The political quarterly, 107–116. doi:10.1111/1467-923x.12620

Easton, D. (1968). The Theoretical Relevance of Political Socialization. Can. J. Pol. Sci. 1, 125–146. doi:10.1017/s0008423900036477

Fetzer, J. S. (2000). Public Attitudes toward Immigration in the united states, france, and germany. Cambridge University Press.

Gest, J., Reny, T., and Mayer, J. (2018). Roots of the Radical Right: Nostalgic Deprivation in the united states and Britain, 51. Comparative Political Studies, 1694–1719. doi:10.1177/0010414017720705

Gidron, N., and Hall, P. A. (2017). The Politics of Social Status: Economic and Cultural Roots of the Populist Right. Br. J. Sociol. 68 Suppl 1, S57–S84. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12319

Goerres, A., Spies, D. C., and Kumlin, S. (2018). The Electoral Supporter Base of the Alternative for germany. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 24, 246–269. doi:10.1111/spsr.12306

Haffert, L. (2021). The Long-Term Effects of Oppression: Prussia, Political Catholicism, and the Alternative für Deutschland. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev., 1–20. doi:10.1017/s0003055421001040

Heinrich, G. (2011). Kernwählerschaft Mobilisiert–Die NPD. Die Landtagswahl in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, 77–89.

Hildebrandt, A., and Trüdinger, E-M. (2021). Belonging and Exclusion: The Dark Side of Regional Identity in germany, 1–18. Comparative European Politics.

Hoerner, J. M., Jaax, A., and Rodon, T. (2019). The Long-Term Impact of the Location of Concentration Camps on Radical-Right Voting in germany. Res. Polit. 6, 2053168019891376. doi:10.1177/2053168019891376

Homola, J., Pereira, M. M., and Tavits, M. (2020). Legacies of the Third Reich: Concentration Camps and Out-Group Intolerance. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev., 1–18. doi:10.1017/s0003055419000832

Huckfeldt, R. R. (2007). Politics in Context: Assimilation and Conflict in Urban Neighborhoods. Algora Publishing.

Ivarsflaten, E., Blinder, S., and Ford, R. (2010). The Anti‐Racism Norm in Western European Immigration Politics: Why We Need to Consider it and How to Measure it. J. Elections, Public Opin. Parties 20, 421–445. doi:10.1080/17457289.2010.511805

Ivarsflaten, E. (2008). What Unites Right-Wing Populists in Western Europe? Re-examining Grievance Mobilization Models in Seven Successful Cases, 41. Comparative Political Studies, 3–23. doi:10.1177/0010414006294168

Jankowski, M., Schneider, S., and Tepe, M. (2017). Ideological alternative? Analyzing alternative für deutschland candidates’ ideal points via black box scaling, 23. Party Politics, 704–716. doi:10.1177/1354068815625230

Kinder, D. R., and Drake, K. W. (2009). Myrdal's Prediction. Polit. Psychol. 30, 539–568. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2009.00714.x

Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., and Frey, T. (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge University Press.

Kriesi, H., and Schulte-Cloos, J. (2020). Support for Radical Parties in Western Europe: Structural Conflicts and Political Dynamics. Elect. Stud. 65, 102–138. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102138

Lubbers, M., Gijsberts, M., and Scheepers, P. (2002). Extreme Right-wing Voting in Western Europe. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 41, 345–378. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.00015

Lubbers, M., and Scheepers, P. (2001). Explaining the Trend in Extreme Right-Wing Voting: Germany 1989-1998. Eur. Sociological Rev. 17, 431–449. doi:10.1093/esr/17.4.431

Maxwell, R. (2019). Cosmopolitan Immigration Attitudes in Large European Cities: Contextual or Compositional Effects? Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 113, 456–474. doi:10.1017/s0003055418000898

Meijers, M. J., and Williams, C. J. (2020). When Shifting Backfires: The Electoral Consequences of Responding to Niche Party EU Positions. J. Eur. Public Pol. 27, 1506–1525. doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1668044

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge University Press.

Noury, A., and Roland, G. (2020). Identity Politics and Populism in Europe, 23. Annual Review of Political Science, 421–439. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-050718-033542 Identity Politics and Populism in EuropeAnnu. Rev. Polit. Sci.

Rooduijn, M., Van Der Brug, W., and De Lange, S. L. (2016). Expressing or Fuelling Discontent? the Relationship between Populist Voting and Political Discontent. Elect. Stud. 43, 32–40. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2016.04.006

Schulte-Cloos, J., and Bauer, P. C. (2021). Local Candidates, Place-Based Identities, and Electoral success. Political Behavior, 1–20.

Schulte-Cloos, J., and Leininger, A. (2021). Electoral Mobilization, Political Disaffection, and the Rise of the Populist Radical Right. Party Politics Online First.

Silva, P. C., and Crisp, B. F. (2021). Ballot Spoilage as a Response to Limitations on Choice and Influence, 1354068821990258. Party Politics.

Speit, A. (2009). “„Auf kommunaler Ebene Ausgrenzung unterlaufen" Kommunale Dominanzbemühungen der NPD in Regionen von Mecklenburg-Vorpommern,” in Strategien der extremen rechten (Springer), 230–244. doi:10.1007/978-3-531-91708-5_13

Spoon, J.-J., and Klüver, H. (2020). Responding to Far Right Challengers: Does Accommodation Pay off? J. Eur. Public Pol. 27, 273–291. doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1701530

Stockemer, D. (2017). The success of Radical Right-wing Parties in Western European Regions - New Challenging Findings. J. Contemp. Eur. Stud. 25, 41–56. doi:10.1080/14782804.2016.1198691

Tobler, W. R. (1970). A Computer Movie Simulating Urban Growth in the detroit Region. Econ. Geogr. 46, 234–240. doi:10.2307/143141

Valentim, V., and Widmann, T. (2021). Does Radical-Right success Make the Political Debate More Negative? Evidence from Emotional Rhetoric in German State Parliaments. Polit. Behav., 1–22.

Valentino, N. A., Hutchings, V. L., and White, I. K. (2002). Cues that Matter: How Political Ads Prime Racial Attitudes during Campaigns. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 96, 75–90. doi:10.1017/s0003055402004240

van Heerden, S. C., and van der Brug, W. (2017). Demonisation and Electoral Support for Populist Radical Right Parties: A Temporary Effect. Elect. Stud. 47, 36–45. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2017.04.002

Winter, N. J. (2008). Dangerous Frames: How Ideas about Race and Gender Shape Public Opinion. University of Chicago Press.

Zimmermann, E. (2003). “Right-wing Extremism and Xenophobia in germany: Escalation, Exaggeration, or what,” in Right-wing Extremism in the Twenty-First century. Editors P. Merkl, and W. Leonard (Portland: OR: F. Cass), 220–250.

Keywords: populist radical right, electoral behavior, right-extremism, party competition, political cleavage, new right politics, Alternative for Germany (AfD)

Citation: Schulte-Cloos J (2022) Political Potentials, Deep-Seated Nativism and the Success of the German AfD. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:698085. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.698085

Received: 20 April 2021; Accepted: 08 October 2021;

Published: 22 February 2022.

Edited by:

Marc van de Wardt, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Ruth Dassonneville, Université de Montréal, CanadaDiego Fossati, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Copyright © 2022 Schulte-Cloos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Julia Schulte-Cloos, anVsaWEuc2NodWx0ZS1jbG9vc0Bnc2kubG11LmRl

Julia Schulte-Cloos

Julia Schulte-Cloos